Abstract

Extreme prematurity, defined as a gestational age of fewer than 28 weeks, is a significant health problem worldwide. It carries a high burden of mortality and morbidity, in large part due to the immaturity of the lungs at this stage of development. The standard of care for these patients includes support with mechanical ventilation, which exacerbates lung pathology. Extracorporeal life support (ECLS), also called artificial placenta technology when applied to extremely preterm (EPT) infants, offers an intriguing solution. ECLS involves providing gas exchange via an extracorporeal device, thereby doing the work of the lungs and allowing them to develop without being subjected to injurious mechanical ventilation. While ECLS has been successfully used in respiratory failure in full term neonates, children, and adults, it has not been applied effectively to the EPT patient population. In this review, we discuss the unique aspects of EPT infants and the challenges of applying ECLS to these patients. In addition, we review recent progress in artificial placenta technology development. We then offer analysis on design considerations for successful engineering of a membrane oxygenator for an artificial placenta circuit. Finally, we examine next generation oxygenators that might advance the development of artificial placenta devices.

Keywords: Artificial placenta, extracorporeal life support, ECLS, extreme prematurity, hollow-fiber membranes, microfluidics

A. Introduction:

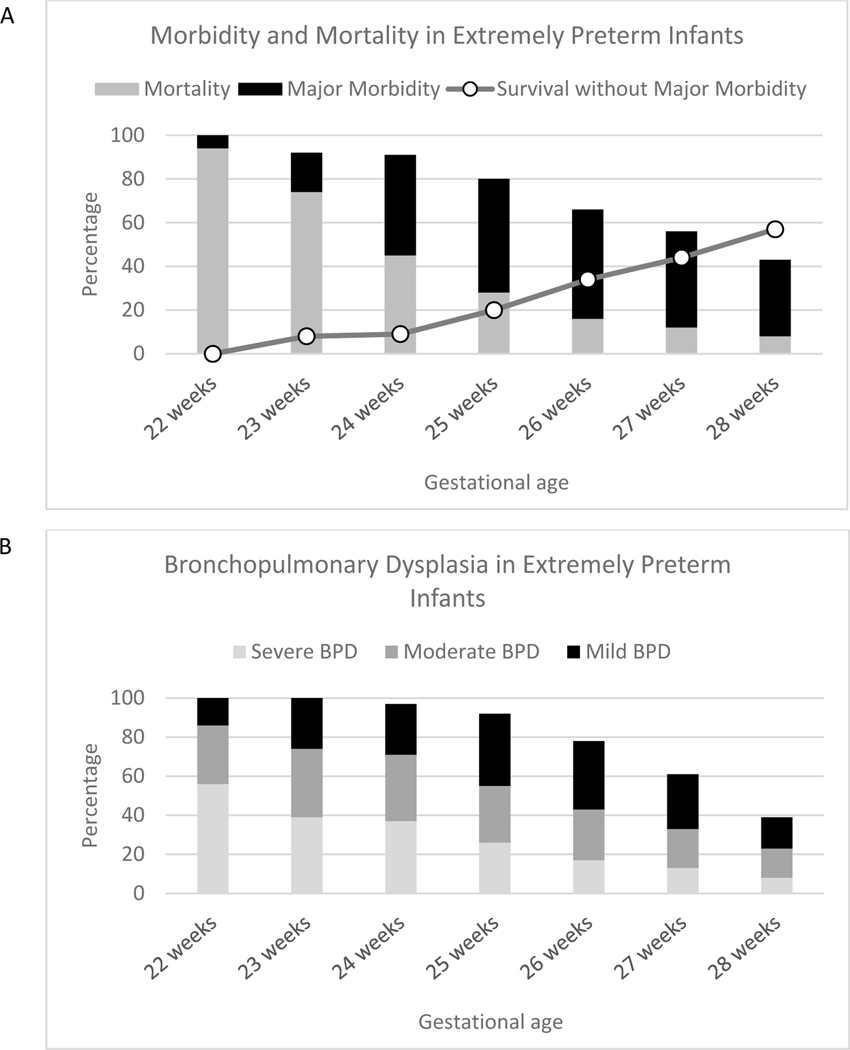

Premature birth, defined as fewer than 37 completed weeks of gestion is a major health problem. It affects approximately 11% of all liveborn infants, totaling 15 million babies per year worldwide and more than a half a million per year in the United States.1 Amongst premature infants, there is a clear negative correlation between weeks of completed gestation and severity of illness.2 With rare exceptions, those born at fewer than 22 weeks of gestation are considered below the limit of viability and are thus not candidates for resuscitation.3 Neonates born between 22 and 28 weeks of gestation are categorized as extremely preterm (EPT) infants. In the United States, 25,000 EPT infants are born each year.4 These infants often overlap with another category of extreme prematurity defined by birthweight of less than 1000 g, known as extremely low birthweight (ELBW). While neonatal critical care has improved outcomes for EPT babies, it remains a serious problem with high morbidity and mortality (Figure 1a).

Figure 1:

Outcomes in extremely premature infants. (a) Mortality and major morbidity rates are high in EPT infants. Survival without major morbidity is correlated with gestational age, with the worst outcomes seen in the most premature infants. Major morbidity is defined as severe intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), periventricular leukomalacia (PVL), bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), infections, and stage 3 retinopathy of prematurity (ROP). (b) Bronchopulmonary dysplasia is common in EPT infants and is correlated with gestational age. Both the frequency and severity of BPD increase with decreasing gestational age. Graphs created using data from Stoll et al.2

The primary driver for poor outcomes in this patient population is the underdevelopment of the lungs. Prior to 16 weeks of gestation, the lungs are little more than branching airways and primitive acinar structures, incapable of gas exchange.5 Between 16 and 26 weeks, the lungs undergo the canalicular period of development, where the acinar structures dilate, and pulmonary capillaries start to form in the primitive lungs. At 26 weeks, the lungs enter the saccular phase, which is characterized by rapid lung growth, thinning of the respiratory epithelium into saccules, approximation of pulmonary capillaries to the developing saccules, and production of surfactant. The saccular period continues until around 36 weeks, when saccules start to divide into alveoli to increase the surface area for gas exchange.

Given the lung immaturity of EPT infants, positive pressure ventilation to support respiratory gas exchange is a primary component of care.6 For some EPT infants, this can take the form of non-invasive positive pressure ventilation, such as continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). However, only around a quarter of EPT patients can be adequately supported with non-invasive ventilation, and the majority require endotracheal intubation and a mechanical ventilator.2 Though necessary to keep these infants alive, mechanical ventilation damages the lungs, a phenomenon termed ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI).7 Furthermore, the transition of the lung environment from amniotic fluid in utero to gas-based ventilation may arrest lung development in the canalicular phase.8,9 Together, these induce inflammation in the premature lungs, leading to abnormal development and ultimately, chronic lung disease of prematurity, known as bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD).10 While lung-protective ventilation techniques, antenatal steroids, and surfactant administration have had an impact on reducing lung injury, two-thirds of EPT patients go on to develop BPD (Figure 1b).11 Infants with BPD frequently require long-term respiratory support, including supplemental oxygen, CPAP, or a surgical tracheostomy and years of mechanical ventilation.12 Furthermore, children with BPD are at increased risk of rehospitalization for respiratory infections,13,14 poor lung function in childhood,15 heart failure due to pulmonary arterial hypertension,16 and delayed neurodevelopment.17

Extracorporeal life support (ECLS) is an advanced therapy that can support lung function, and thus offers the potential to obviate the need for mechanical ventilation, thereby preventing VILI. ECLS was first introduced into clinical practice in 1972, when a cardiopulmonary bypass circuit was used successfully to support an adult patient with post-traumatic respiratory failure in the intensive care unit.18 Shortly thereafter, Dr. Robert Bartlett successfully used ECLS to support a neonate with hypoxic respiratory failure from meconium aspiration, which ultimately led to a series of studies supporting its use in the neonatal population.19–21 Since then, the use of ECLS has steadily increased, expanding beyond neonates to include pediatric and adult patients. To date, over 129,000 ECLS runs have been recorded in the international registry, with 12,850 in 2019.22

The basic design of an ECLS circuit is shown in Figure 2. Venous blood is drawn from a large central vein and pumped through an oxygenator. Inside the oxygenator, a sweep gas mixture of pure oxygen and compressed air interacts with the blood via a semipermeable membrane such that oxygen diffuses from the gas side into the blood and carbon dioxide diffuses from the blood into the sweep gas for disposal. This membrane is made of a gas-permeable material such as polymethylpentene (PMP), allowing gas exchange without permitting blood or plasma leakage.23 In veno-venous (V-V) ECLS, the oxygenated blood is then returned to the venous circulation of the patient. V-V ECLS thus supports the work of the lung but relies on a functioning heart to pump the oxygenated blood to the body. By contrast, in veno-arterial (V-A) ECLS, blood is returned to a large artery, such that the heart is bypassed. Thus, V-A ECLS can support the functions of the heart and lungs.

Figure 2:

Circuit design of a neonatal ECLS circuit. Deoxygenated blood is drawn from a large vein, often in the neck. It is then pumped to an oxygenator, where a blenderized combination of oxygen and compressed air mixes with the blood via a semipermeable membrane. Oxygen diffuses into the blood, and carbon dioxide diffuses out of the blood. The oxygenated blood is then returned to the patient via a large vein or artery.

Despite the established benefit in full-term neonates, ECLS has not been widely applied in premature infants, a population where the mitigation of VILI in developing lungs might be especially impactful. Indeed, in utero, the placenta acts as an extracorporeal oxygenator for the developing fetus that does not use its lungs for gas exchange. Similarly, ECLS support could allow the premature lungs to continue to develop in an aqueous environment instead of being forced to perform gas ventilation. Yet, guidelines from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization list gestational age of fewer than 34 weeks as a relative contraindication to ECLS.24 Although there are case reports of survival with ECLS in infants between 29 and 33 weeks gestation, this is not standard practice, and many institutions choose not to offer ECLS to infants younger than 34 weeks gestation.25,26

The purpose of this review is to describe the impediments to the use of ECLS in EPT infants and potential solutions to these obstacles. The first section discusses the unique aspects of EPT infants that complicate the use of ECLS. Next, we explore research developments in ECLS for EPT infants, frequently termed “artificial placenta.” The third section outlines the design components of an artificial placenta oxygenator, focusing on how to guide the next generation of this technology. Finally, we analyze artificial lung technology in development and how to apply these devices to an artificial placenta.

B. Unique Challenges of ECLS in EPT Infants

EPT infants are a unique patient population that present important challenges to successful ECLS support. Many of these difficulties are secondary to the simple fact that these infants are much smaller than any other patient population. However, other problems arise from their immaturity of development.

Thrombosis and Anticoagulation

Bleeding and clotting are the most common serious complications of ECLS.27–29 The ECLS circuit, as a foreign, non-biological material, is highly prothrombotic, which can result in catastrophic clotting complications, such as stroke, limb ischemia, and circuit failure.30 For this reason, systemic anticoagulation is needed to prevent clot formation. However, anticoagulation is associated with a significant risk of bleeding. In fact, 20–60% of patients are estimated to have major bleeding27–29 and 10–50% have thrombotic events while on ECLS.27,28 The wide range of bleeding and thrombosis complications between studies is likely due to differing anticoagulation target levels. Studies aiming for higher levels of anticoagulation had fewer clotting events but more bleeding and vice versa. Overall, the rate of major thrombosis or bleeding is likely more than half of patients on ECLS.

Circuit blood flow rates in infants and children are guided by the size of the patient, typically 100 mL/min/kg body weight.24 In addition, the blood flow rate is inversely related with the risk of thrombosis, since areas of blood flow stasis are more likely at lower flow rates, thus promoting clot formation and propagation.31 Therefore, low weight EPT infants supported with ECLS are at increased risk for circuit clotting, due to lower blood flow rates compared to larger babies.

Yet, perhaps the biggest barrier to ECLS in EPT infants is their high risk for intracranial bleeding that results in death or severe neurologic injury. One of the more common serious complications of extreme prematurity is spontaneous germinal matrix intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH).32 One third of EPT infants develop spontaneous IVH, with 16% classified as severe (Grade 3 or 4 IVH).2 The incidence of severe IVH is inversely related to gestational age: 7% of 28-week infants versus 38% of 22-week infants. As such, the high-dose anticoagulation (typically an unfractionated heparin infusion, run at 10–60 units/kg/hr) 24 required for ECLS in EPT infants carries disproportional risk compared to older infants. One study of infants between 29 and 33 weeks gestational age who underwent ECLS found an incidence of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) of 21%,25 around twice the rate of spontaneous IVH in infants of the same gestational age not exposed to ECLS.33 This is also higher than the 12% incidence reported in full term neonates undergoing ECLS.30

Blood loss

ECLS results in blood loss via a variety of mechanisms, including hemodilution, hemolysis, consumption, phlebotomy, and bleeding. Hemodilution relates to the ratio of the extracorporeal circuit volume to the patient’s intravascular volume as well as the fluid used to prime the circuit, typically a combination of blood products, albumin, or crystalloid.24 Hemolysis is frequently encountered in patients supported with ECLS;30 the pumps required to generate forward blood flow through the circuit can cause red blood cell lysis and subsequent anemia. Hemolysis also leads to an accumulation of bilirubin, which can cause neurologic damage in neonates (i.e. kernicterus), especially in EPT infants.34 The type of pump (i.e. centrifugal versus roller pump) may have an impact on the degree of hemolysis, though this is not a settled issue, with some studies favoring roller pumps35,36 and others finding no difference.37,38 Consumption of blood components occurs in large part due to the prothrombotic nature of the ECLS circuit. Thrombosis leads to clot formation, with consumption of circulating red blood cells, platelets and clotting factors.39 Phlebotomy is required in order to manage anticoagulation levels, blood product needs, and gas exchange for patients on ECLS.24 Finally, as previously mentioned, bleeding is a major issue in ECLS due to the anticoagulation required to maintain the circuit.

While these mechanisms of blood loss are seen in ECLS patients of all ages, EPT infants are more profoundly affected by these mechanisms of blood loss due to their smaller blood volume and underdeveloped blood cell production. The blood volume of an EPT infant is typically 70–80 mL/kg.40,41 For a typical 22-week infant weighing 0.5 kg,2 this equates to only 35–40 mL total blood volume, much smaller than the volume of an ECLS circuit, which varies widely by circuit type, but is approximately 100 mL in the smallest circuits.42 Losses from hemolysis, consumption, phlebotomy, and bleeding are similarly compounded due to the low blood volume of EPT infants. In addition to having a small blood volume, EPT infants also have underdeveloped red blood cell and platelet production.43,44 This limits their ability to compensate for blood losses resulting from ECLS support.

Vessel Cannulation

ECLS requires the placement of large cannulae in one or more major veins (V-V ECLS) or a major vein and artery (V-A ECLS) in order to facilitate high volume blood flow from and back to the patient. Cannulation of blood vessels presents an obvious challenge in EPT infants, since the vasculature is smaller and thus more difficult to access the earlier an infant is born. Newborns, including premature infants, have umbilical vessels, which are relatively accessible for central venous and arterial catheter placement. While current neonatal ECLS practices typically use the neck vessels (i.e. internal jugular vein and carotid artery) for cannulation,45 umbilical cannulation for ECLS remains an important area of investigation.46,47 Technical problems related to flow and resistance need to be overcome. For example, at 22 weeks, the umbilical vein averages 4.7 mm in diameter compared to 8.2 mm at full term, and the umbilical arteries average 2.4 mm in diameter compared to 4.2 mm at term.48 Based on the relationship between flow and vessel radius (i.e. Poiseuille’s law), the 43% change in vessel caliber between 22 weeks and term translates to a nearly 10-fold differential in resistance to flow.

C. Advancements in Artificial Placenta Technology

Despite the challenges associated with ECLS in EPT infants, attempts have been made to develop an artificial placenta. Although the placenta performs multiple physiologic functions, including nutrient uptake, thermoregulation, waste elimination, immune regulation, and hormone delivery,49,50 the primary function of an ECLS system is gas exchange. As such, the term “artificial placenta” has been traditionally applied to ECLS in EPT neonates for the purpose of allowing natural lung development in an aqueous environment. While there are no FDA-approved artificial placenta devices, significant research progress has been made in the development of artificial placenta circuits.

The concept of an artificial placenta was first suggested shortly after the development of the cardiopulmonary bypass machine for heart surgery. In early 1960s, Callaghan and colleagues supported fetal lambs submerged in artificial amniotic fluid for up to 40 minutes.51,52 The next few decades saw incremental improvements in survival time, culminating in a study by Unno et al. showing survival of two premature goats for 3 weeks.53 However, while the study showed impressive survival, the goats required significant support throughout the study, including dialysis and continuous paralysis, and ultimately the goats died of respiratory failure after being transitioned to mechanical ventilation. In fact, many of these early studies were limited by common problems including infection, cannulation complications, inadequate circuit blood flow, and circulatory failure caused by the additional workload imposed on the heart. Several review articles provide historical context of artificial placenta development throughout the 20th and early 21st centuries, including in-depth commentary on these issues.54–56 However, in the last decade, progress has been made towards overcoming these barriers.

Research on artificial placenta technology led by Drs. George Mychaliska and Robert Bartlett at the University of Michigan resulted in the first publication of extracorporeal support in a lamb model of extreme prematurity (Figure 3a,b).57 They studied lambs between 115 and 120 days gestation, which is the equivalent of a 24-week human infant in terms of lung development. Lambs were supported by V-V ECLS using the jugular vein for drainage and umbilical vein for reinfusion. Blood flow was maintained with a roller pump, and gas exchange was performed with a Capiox RX05 polypropylene hollow-fiber oxygenator.58 The lambs were not submerged in artificial amniotic fluid, but rather the lungs were filled with amniotic fluid via an endotracheal tube. Four of 10 lambs survived to the end of the one-week study, whereas no age-matched control lambs supported with mechanical ventilation survived beyond 8 hours. Subsequent work reported in Church et al. using a similar lamb model and ECLS system showed survival up to 10 days in 5 lambs.59 Importantly, this study also showed continued lung development and prevention of lung injury, validating the concept of using an artificial placenta circuit to reduce VILI and chronic lung disease in EPT infants.

Figure 3:

Artificial placenta devices in development. Featured devices are from (a,b) the University of Michigan,57,58 (c,d) RWTH Aachen University,60 and (e,f) the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.64,65 The left column (a,c,e) shows the oxygenator used for the circuit, and the right column (b,d,f) presents the implementation of the circuit in an animal model. Images reproduced with permission from respective cited publications.

Another group at RWTH Aachen University has taken a pumpless circuit approach. In Arens et al., the authors report development of the NeonatOx, a custom hollow-fiber oxygenator specifically designed for artificial placenta support (Figure 3c,d).60 It is significantly smaller than commercially available neonatal oxygenators, containing only 0.09 m2 of gas exchange membrane area and a priming volume of 12 mL. The pumpless approach uses an arterio-venous (A-V) cannulation strategy such that arterial blood pressure drives blood flow through the extracorporeal circuit. In a follow-up study, the group tested their oxygenator in 7 preterm lambs with a gestational age of 132 days (31-week human equivalent).61 Lambs were initially mechanically ventilated but slowly transitioned to full extracorporeal gas exchange via a specific protocol based on blood gas parameters. They were able to support 6 of 7 lambs for the 6-hour duration of the study.

A collaboration between Tohoku University and the University of Western Australia was the first to study a pumpless circuit in an extremely premature lamb model.62 They tested their device in fetal lambs with an average gestational age of 112 days (23-week human equivalent). The circuit consisted of umbilical vessel cannulation and a custom-built hollow-fiber oxygenator designed to have a low priming volume. To further reduce hydraulic resistance, they tested a circuit configuration consisting of two half-sized oxygenators, placed in parallel. All 10 lambs survived to the end of the study, which varied between 48 and 72 hours. Compared to a single oxygenator circuit, their parallel circuit had twice the circuit blood flow (118 versus 61 mL/min/kg body weight). Oxygen delivery to the organs was also improved, as evidenced by lower lactate levels. Another study by the same group pushed this boundary further, studying a subsequent iteration of their artificial placenta circuit, which they called the EVE system, in 95-day gestational age lambs.63 While other groups have tested devices in lambs with lung development that is equivalent to EPT infants, this is the only study that used lambs of a similar weight to a 24-week infant. They showed survival and fetal growth for 5 days in 7 out of 8 animals.

An important advance in artificial placenta support was published by a group led by Dr. Alan Flake from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (Figure 3e,f).64 They reported multiple device design iterations, with initial pilot studies informing improvements in cannulation strategy and the artificial amniotic fluid environment. Their extracorporeal circuit was a pumpless A-V ECLS circuit with a modified version of the commercial Quadrox oxygenator.65 In addition, they introduced the Biobag system, a closed circuit for circulation of sterile artificial amniotic fluid. With their final design, they were able to extracorporeally support 8 lambs (5 between 105 and 108 days gestation, 3 between 115 and 120 days gestation) for up to 4 weeks. Furthermore, lambs showed normal organ growth and development.

D. Designing Next-Generation Oxygenators for the Artificial Placenta

The past decade has seen significant advancement in the viability of artificial placenta technology. However, there is still work to be done to improve the design of oxygenators for this purpose. In this section, we will review some of the design considerations to inform the next generation of oxygenators.

Minimal Anticoagulation

The most difficult, yet arguably most important, challenge is creating an oxygenator that can function without (or with minimal) systemic anticoagulation. Due to the devastating consequences of spontaneous IVH in EPT infants, high-dose systemic anticoagulation is contraindicated. Interestingly, low-dose heparin has been proposed as a possible prophylactic treatment for IVH, the rationale being that thrombi formation the central venous system may contribute to the development of IVH.66 While a meta-analysis showed no benefit of low-dose heparin (1 unit/mL), it also showed no harm at that dose.67 Therefore, decreasing the anticoagulation requirement to the low-dose heparin range may be compatible with artificial placenta use in EPT neonates. There are several avenues by which the need for anticoagulation in an oxygenator can be reduced.

Heterogeneity in the blood flow path is an important contributor to clotting in ECLS. Both high and low flow can promote coagulation by different mechanisms. High flow can create shear stress, resulting in platelet activation and aggregation to form “white clots.”68,69 Conversely, low flow can result in stasis, which is well known to be prothrombotic, a phenomenon noted as early as 1856 by Rudolf Virchow.70 Analysis of ECLS circuits demonstrates that even in fully anticoagulated patients, clots form at tubing connectors, the entry to oxygenators, and at the corners of oxygenators.71–74 Notably, these are all areas where blood flow fluid dynamics are altered, and this heterogeneity in flow creates a prothrombotic environment.75 In future generations of artificial placenta circuits, it will be important to minimize these disruptions to blood flow. However, reducing the number of connectors and corners does not ultimately solve a fundamental weakness of hollow-fiber membrane oxygenators, which is the inability to precisely control the blood flow path within the oxygenator. Computational fluid modeling of blood flow around individual hollow fibers has shown significant flow heterogeneity, even in uniformly distributed hollow-fiber membranes.76,77

In addition, there have been significant efforts to modify the surface of artificial materials to make them less likely to induce thrombosis. Heparin-coating of ECLS circuitry is a strategy that has been used to reduce the need for systemic anticoagulation.78,79 Most modern ECLS circuits use heparin-bonded materials, though studies have not consistently shown a long-term benefit.80–82 Phosphorylcholine (PC) is another coating strategy that has been trialed. PC is the hydrophilic head group found on cell membrane phospholipids, and thus PC coatings are thought to mimic the endothelial cell membrane. A small study of PC-coated oxygenators for cardiopulmonary bypass showed a 53% reduction of thrombin formation, but no difference in fibrinogen, antithrombin, or platelet levels.83 Larger studies looking at thrombosis with PC-coated ECLS circuitry are lacking. Nitric oxide is another molecule that has generated interest as a potential surface modifier due to its potent antiplatelet properties. Nitric oxide added to the oxygenator sweep gas reduced platelet adhesion and thrombosis by up to 90% in animal models.84,85 Similarly, nitric oxide releasing circuit tubing86,87 and hollow-fibers88,89 have been shown to reduce platelet consumption and thrombosis in preclinical studies by approximately two-thirds. Yet another surface modification strategy that has generated interest is the use zwitterionic coatings such as poly-carboxybetaine (PCB) and poly-sulfobetaine (PSB), which have anti-biofouling properties.90,91 When tested in vitro, these coatings reduced platelet adhesion by 80–96%,92,93 and an in vivo study showed reduction of thrombus formation by 59%.94 Finally, there have been efforts to create biohybrid hollow-fiber membranes lined with living endothelial cells. Several groups have established confluent endothelialization using ovine carotid95 and bovine aortic96 endothelial cells, though more recent successes have used human umbilical cord endothelial cells.97–100 However, this type of approach has several challenges. One potential problem is the limitation of gas exchange by adding a layer of cells. The data have been mixed on this issue. While some short-term studies showed no effect96,101 or even improved gas permeability,102 a longer-term study showed impairment of gas transfer that developed over time.100 Another issue that has not been resolved is the immunologic reaction to non-autologous endothelial cells. Weigmann et al. prevented immunologic rejection in vitro by genetically modifying endothelial cells to not express β2 microglobulin, a cell surface protein important for immune recognition.103 However, the reproducibility of this in in vivo models remains to be seen.

Low Priming Volume

Another important design consideration is reducing the total priming volume of the circuit. As discussed previously, the extracorporeal blood volume can be significant in small EPT patients, increasing hemodilution and transfusion requirements. In addition, priming volume influences hemocompatibility and may have a secondary role in altering anticoagulation needs. A larger priming volume increases the extracorporeal residence time of the blood, which has been increasingly recognized to be a contributor to hemocompatibility. Longer extracorporeal residence times increase platelet stress, leading to platelet activation and thrombosis.75,104–106

Part of the solution is simply matching the size of the oxygenator to the size of the patient. Commercial ECLS oxygenators are designed for patients 2 kg and larger, which is 2–4 times larger than the typical EPT infant. Oxygenators that are customized to the size of EPT infants, such as the NeonatOx or EVE oxygenators, offer an advantage in priming volume over oxygenators designed for larger patients.

Another way to reduce priming volume is to improve the gas exchange efficiency of the oxygenator. This can be accomplished via a variety of mechanisms. Pressurizing the sweep gas would create a larger diffusion gradient to drive oxygen across the membrane into the blood. This strategy would require membranes that have sufficient structural rigidity to prevent expansion and rupture, which would cause problematic gas emboli. Alternatively, the gas permeability of the membrane could be improved by increasing the total pore area or reducing the membrane thickness. However, in modern oxygenators, the membrane is typically not the primary limiter of oxygen flux; rather, it is the diffusion of oxygen throughout the blood channel that limits efficiency.107 In pulmonary capillaries, oxygen has an effective diffusion distance of only 1–2 μm,108 an order of magnitude less than that of artificial oxygenators.107 By reducing the diffusion distance of oxygen within the blood channel, oxygenator efficiency could be improved with a reduction in the total priming volume.

Pumpless

Pumpless extracorporeal circuits have garnered significant interest amongst artificial placenta researchers. The exclusion of a pump would decrease the overall volume of the extracorporeal circuit. In addition, a pumpless system may reduce hemolysis, which contributes to the problems of anemia and hyperbilirubinemia. Furthermore, the ECLS pump contributes to thrombosis via a variety of mechanisms, including platelet activation from shear forces on the blood106 as well as generation of prothrombotic bioproducts of red blood cell lysis.109 Clots in the oxygenator subsequently lead to more blood trauma, creating a vicious cycle of thrombosis and hemolysis.31

It is important to note that pumpless circuits also pose challenges. Pumpless circuits rely on the infant’s heart to drive flow through the circuit, which can be problematic in the setting of hemodynamic instability. Furthermore, since an A-V pumpless system represents a systemic-to-venous shunt, the overall device resistance must be very precisely tuned. If the resistance is too high, there will not be enough blood flow through the oxygenator to provide adequate gas exchange. However, if the resistance is too low, the circuit could potentially steal blood from the systemic circulation, compromising perfusion of vital organs. Importantly, in the fetal circulation, up to 60% of fetal cardiac output flows through the placenta (equivalent to a post-natal extracorporeal circuit).110 This suggests that EPT infants without cardiac disease could accommodate a pumpless extracorporeal circuit.

E. Application of Novel Oxygenator Technology to the Artificial Placenta

Innovation in oxygenators for an artificial placenta has certainly lagged behind the development of novel technology for ECLS and artificial lungs. However, fundamentally, the technologies are very similar, so artificial placenta researchers have often relied on commercial ECLS oxygenators. While there is a need for development of oxygenators specifically designed for artificial placenta circuits, with a few exceptions, this has not historically occurred. In this section, we will review the novel oxygenators for artificial lungs and analyze how they might be applied in an artificial placenta circuit. Where applicable, we will also discuss novel oxygenators being specifically developed for an artificial placenta.

Hollow-fiber Membranes

Hollow-fiber membrane oxygenators have been the standard of care for neonatal, pediatric, and adult ECLS for decades. They are compact and efficient due to their large surface area-to-volume ratio. There are several design variations between different oxygenators, discussed below and summarized in Table 1.

Table 1:

Comparison of hollow-fiber oxygenators

| Name | Stage of Development | Surface Area | Priming volume | Pump-driven or pumpless | Blood flow path |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quadrox-i Neonatal | FDA approved | 0.38 m2 | 38 mL | Pump-driven* | Heterogenous blood flow in circuit connectors between pump and oxygenator and around hollow fibers |

| Novalung iLA | FDA approved | 1.3 m2 | 175 mL | Pumpless | Heterogeneous blood flow around hollow fibers but reduced number of connectors due to lack of a pump |

| P-PAL | Long-term animal studies | 0.3 m2 | 270 mL | Pump-driven | Heterogeneous blood flow around hollow fibers, but path between pump and oxygenator better defined |

| PediPL | Long-term animal studies | 0.3 m2 | 110 mL | Pump-driven | Heterogeneous blood flow around hollow fibers, but path between pump and oxygenator better defined |

| M-Lung | Short-term animal studies | 0.13 m2 | 68 mL | Pump-driven | Heterogeneous blood flow in circuit connectors between pump and oxygenator. Secondary vortices in oxygenator create additional turbulence |

| NeonatOx | Short-term animal studies | 0.09 m2 | 12 mL | Pumpless | Heterogeneous blood flow around hollow fibers but reduced number of connectors due to lack of a pump |

| EVE | Long-term animal studies | 0.15 m2 | 50 mL | Pumpless | Heterogeneous blood flow around hollow fibers but reduced number of connectors due to lack of a pump |

The Quadrox-i Neonatal has also been used in a pumpless fashion in artificial placenta circuits (Partridge et al., 2017)

One of the most common oxygenators in clinical use is the Maquet Quadrox, for which there are many sizes, including a neonatal version. The Quadrox is a diamond-shaped oxygenator with PMP hollow fibers that are woven into stackable mats. The neonatal Quadrox has a priming volume of 38 mL and a pressure drop of 20 mmHg at a blood flow rate of 0.5 L/min.65 While it is advertised as a low-resistance oxygenator, it is still designed to be used with a pump. Another issue is that the diamond shape allows areas of stagnancy at the corners that are prone to clotting.73 Due to this design and the inability to control blood flow heterogeneity through the fiber bundle, the Quadrox requires systemic anticoagulation.

With its recent premarket notification FDA approval in February 2020, Novalung joined the list of approved ECLS oxygenators in the United States. Novalung was the first to develop a pumpless oxygenator, known as the Novalung iLA.111 The Novalung iLA works by placement of cannulae into the femoral artery and vein, creating an A-V circuit. The Novalung has had some clinical success as a bridge to lung transplant112,113 and for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).114 However, it has a few issues that make it difficult to adapt to artificial placenta technology. First, while Novalung does make pump-driven ECLS systems for children, the pumpless Novalung iLA is designed for adults. Its priming volume, at 175 mL, is far too large for a premature infant. In addition, like the Quadrox, it requires systemic anticoagulation.

Several groups have developed integrated pump-oxygenators. Maquet combined the Quadrox oxygenator with a centrifugal pump to create the Cardiohelp system, an ECLS circuit used commonly in clinical practice.115 Other groups are performing preclinical testing on compact, integrated pump-oxygenators, some designed for smaller pediatric patients. These include the Pittsburgh Pediatric Ambulatory Lung (P-PAL) developed at the University of Pittsburgh 116–118 and the Pediatric Pump-Lung device (PediPL) created by the University fundamentally of Maryland.119–122 While these devices have various unique design features, they work by combining a centrifugal pump and oxygenator into a single device, thus eliminating excess tubing and connectors. Compared to traditional ECLS circuits, these devices have smaller total circuit priming volume and better control of the flow path between the pump and oxygenator. However, they do not reduce the need for systemic anticoagulation. Furthermore, given the success of pumpless systems in artificial placenta preclinical studies, it is probable that pumps can be eliminated altogether.

Another unique approach to artificial lung technology has been taken by the University of Michigan in the development of the M-lung.123,124 The M-lung consists of concentric circular flow paths, connected by a limited number of gates. These gates create vortices that promote mixing for improved oxygenation. The result is a more efficient oxygenator with a lower membrane surface area and priming volume. In addition, the circular flow paths are thought to lead to less stasis due to lack of corners. However, the vortices also promote turbulence, which can lead to platelet activation and clotting. Indeed, in initial in vivo animal testing, there was significant clot development despite full systemic anticoagulation.124

In developing artificial placenta circuits, some groups have built customized hollow-fiber oxygenators specifically designed for small patients, including the previously mentioned NeonatOx oxygenator60 and EVE system.63 These devices are simply downsized versions of existing hollow-fiber technology, designed to be more appropriate for the size of EPT infants. Compared to commercial oxygenators, they have smaller surface areas, priming volume, and are designed to be pumpless. However, like all the other hollow-fiber oxygenators described above, these are also designed to be used with anticoagulation.

As a whole, hollow-fiber membrane oxygenators have the advantage of being highly efficient, compact oxygenators with excellent gas exchange properties. Their ability to pack a large surface area for gas exchange into a small device size has been a major advantage over previous oxygenators. In addition, newer generations of these oxygenators, with their reduced priming volume, lowered resistance, and improved efficiency, can be more readily adapted for use in artificial placenta circuits. However, hollow-fiber oxygenators are inherently limited by their inability to tightly define the blood flow path to prevent turbulence and stagnancy. This may ultimately make it difficult to create hollow-fiber oxygenators that do not require high-dose anticoagulation, which would be a major barrier to clinical implementation in an artificial placenta device.

Microfluidics

Advancements in microfabrication techniques have generated significant interest in creating oxygenators with microscopic blood channels (Figure 4a).125 Microfluidic oxygenators can be customized to a variety of channel sizes, flow path designs, and membrane thicknesses, all of which have varying effects on gas transfer, hemocompatibility, resistance, and priming volume (Table 2). Therefore, these devices offer an intriguing way to overcome many of the limitations of hollow-fiber membranes.

Figure 4:

Microfluidic oxygenators. (a) The general design of a microfluidic oxygenator involves microscopic blood and gas channels stacked on top of each other with a gas-permeable membrane separating these channels.125 (b) An early device from Lee et al.128 featured 15 μm blood channels and a 130 μm thick membrane. Membrane thicknesses decreased with subsequent microfluidic devices, including (c) a 15 μm membrane from Potkay et al.130 and (d) a 9 μm membrane by Hoganson et al.131 (e) Another device by Hoganson et al.135 experimented with a branched vascular network, and this concept was further explored in (f) Kovach et al.137 which used Murray’s law to create biologically natural vessel branching patterns. Recently, some efforts have focused on improving the structural integrity of microfluidic devices. (g) Dabaghi et al.136 uses a steel mesh to add rigidity to their PDMS membranes, and (h) Dharia et al.139 presents a device featuring rigid silicon micropore membranes bonded to a 5 μm PDMS layer. Images reproduced with permission from respective cited publications.

Table 2:

Comparison of microfluidic oxygenators

| Study | Oxygen Flux* | Surface Area | Priming volume | Anticoagulation† | Blood flow path |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee et al. (2008) | 0.021 mL/min | 0.83 cm2 | 0.0012 mL | Heparin 15,000 U/L + EDTA 0.75 g/L | Straight rectangular channels |

| Burgess et al. (2009) | 0.065 mL/min | 4.72 cm2 | 0.0046 mL | Not tested in blood | Straight semicircular channels |

| Potkay (2009) | 0.13 mL/min | 2.4 cm2 | 0.0062 mL | Not tested in blood | Straight rectangular channels |

| Hoganson et al. (2010) | 0.27 mL/min | 18 cm2 | 0.36 mL | Dose not reported | Branched vascular network, minimizing shear forces |

| Potkay et al. (2011) | 0.037 mL/min | 1.67 cm2 | 0.0017 mL | Heparin 15,000 U/L + EDTA 1 g/L | Grid of rectangular channels with channel height progression based on natural lung branching patterns |

| Hoganson et al. (2011) | 0.079 mL/min | 23.1 cm2 | 0.23 mL | Dose not reported | Branched vascular network, minimizing shear forces |

| Thompson et al. (2017) | 0.034 mL/min | 2.2 cm2 | 0.027 mL | 16% V/V Citrate Phosphate Dextrose | Branching network within a rolled sheet |

| Matharoo et al. (2018) | 0.90 mL/min | 221 cm2 | 10 mL | Heparin 400 U/kg bolus + 30 U/kg/hr infusion | Branching network with steel reinforced membranes. Channel height either uniform at 100 μm or gradually decreasing from 170 μm to 60 μm. |

| Dabaghi et al. (2018) | 2.85 mL/min | 250 cm2 | 8 mL | Heparin 3000 U/L | Branching network with steel reinforced membranes. Uniform channel height. |

| Dharia et al (2018) | 0.28 mL/min | 17.3 cm2 | 0.26 mL | ACT >400 s | Wide, straight blood channel bordered by silicon membranes and titanium |

| Abada et al (2018) | 0.03 mL/min | 0.89 cm2 | 0.13 mL | Not tested in blood | Wide, straight blood channel bordered by membrane and polyether ether ketone |

Oxygen consumption of an EPT infant is 4–7 mL/min for an average 1 kg, 28-week infant (Scopes and Ahmed, 1966).

Anticoagulation management for clinical ECLS varies across institutions but typically consists of unfractionated heparin, titrated to a specific laboratory value such as an activated clotting time (ACT) of 180–220 seconds (Sklar et al., 2016). Usual doses of heparin are in the range of a 50–100 U/kg bolus followed by an infusion of 10–60 U/kg/hr (Brogan et al., 2018). For comparison to in vitro studies with doses reported as concentration, a 100 U/kg heparin dose for a typical 70 kg adult with a blood volume of 5 L is equivalent to a heparin concentration of 1400 U/L.

Early work with microfluidic artificial lungs from a group led by Dr. Lyle Mockros explored the gas exchange properties of microchannels patterned into silicone.126–128 Their miniature device contained 15 μm blood channels with 130 μm polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) walls for gas exchange (Figure 4b). This device significantly reduced priming volume; a full-scale device would have an estimated 13 mL priming volume. While they were able to show oxygenation of porcine blood, their device was limited by the thick gas exchange membrane and large pressure drop across the small blood channels.128

Subsequent work by various groups decreased the membrane thickness to improve efficiency. Burgess et al. reduced the membrane thickness to 64 μm.129 Potkay et al. further reduced the membrane thickness to 15 μm (Figure 4c).130 And Hoganson et al. created microfluidic lungs with 9 μm thick membranes (Figure 4d).131 Ultimately, by improving efficiency, these devices reduced priming volume and artificial material surface area. However, while microfluidics has pushed the boundaries in terms of membrane thinness, these ultra-thin-walled devices suffer from lack of mechanical integrity, especially when stacked. Newer generations of microfluidic lungs have converged upon wall thicknesses in the range of 30–70 μm.132,133

One of the difficulties encountered with microfluidic devices is poor hemocompatibility. Despite the advantages of decreased overall blood-contacting artificial surface area and shorter extracorporeal residence times of blood, microfluidic devices often require anticoagulation in excess of that used clinically with commercial hollow-fiber oxygenators (Table 2). This is likely due in part to the high surface area to volume ratios of the microchannels. The formation of a clot relies of localization of activated platelets and procoagulant proteins within close proximity of each other.134 The small channels create a microenvironment with a high localized concentration of activated procoagulant proteins and platelets and are thus highly prone to clotting. Furthermore, the smaller channels mean that microthrombi are not necessarily flushed through the device, instead occluding the microchannel and serving as niduses for clot propagation.

Strategies to improve hemocompatibility have centered on surface coatings and design of the blood flow path. For the latter, several groups have experimented with the blood channel height to find an optimal balance of efficiency and hemocompatibility. Reducing the channel height improves gas exchange efficiency by reducing the diffusion distance within the blood channel. In addition, it decreases the priming volume. However, a small blood channel also increases the pressure drop across the device and increases the risk of thrombosis. Potkay et al. used a variety of channel heights in their device, ranging from 10 μm to 140 μm, mimicking the sizes of pulmonary vessels in humans.130 Hoganson et al. used a large channel height relative to predecessors, at 200 μm.135 The optimal channel height is still not clear, with various groups featuring channel heights ranging from 10 μm132 to 245 μm.136 Work has also been done to improve hemocompatibility through the use of biomimetic flow paths. Microfluidics offers the ability to fine-tune the blood flow path to optimize shear forces and reduce stasis. Hoganson et al. first explored branching vascular patterns (Figure 4e),135and Potkay et al.130 took this a step further, altering the channel height based on the natural progression of lung vasculature. The Potkay group subsequently used Murray’s law of parent-daughter vessel construction to further guide branching angles and blood channel height (Figure 4f).133,137

Another major challenge microfluidic oxygenators have faced is the difficulty in scaling up to support a full-sized human. Part of the problem is that most oxygenators are made from PDMS, which is elastic and easily deformable. Therefore, it is difficult to maintain the mechanical integrity of microchannels and ultra-thin gas-permeable membranes as microfluidic mini-oxygenators are stacked into single devices. For this reason, several groups have tried creating composite membranes using rigid metal materials to lend mechanical support to microfluidic membranes.

One such strategy is described by Matharoo et al. at McMaster University.138 Their composite membrane consists of a steel mesh with 45 μm pores placed within a 50 μm thick PDMS layer. The steel mesh adds structural rigidity to prevent deformation. In in vivo studies, they were able to partially support a 2 kg piglet in a hypoxic ventilation model using 32 single oxygenator units (SOUs). The entire device had a priming volume of 10 mL, achieved a blood flow rate of 25 mL/min at a pressure drop of 32 mmHg, and had an oxygen flux of 0.9 mL/min at that flow rate. A newer design iteration used a double-sided single oxygenator unit (dsSOU) to increase efficiency.136 The full device, composed of 4 dsSOUs had a total surface area of 250 cm2 and priming volume of 8 mL (Figure 4g). In benchtop blood testing at blood flow rates of 10–60 mL/min, the device had a corresponding pressure drop of 10–60 mmHg and an oxygen flux of 0.78–2.85 mL/min.

Another approach taken by Dharia and colleagues at UCSF used composite micropore-containing silicon and PDMS membranes.139 The composite membranes offer the advantage of providing a rigid, yet thin structure that can be readily stacked into a parallel plate configuration. Importantly, the parallel plate design allows optimization of the blood flow path to minimize shear stresses and stagnancy.140 In addition, these composite membranes feature an ultra-thin gas-permeable PDMS membrane, only 5 μm thick, an order of magnitude thinner than the steel mesh composite membranes described above. When tested in water, individual membranes with a gas exchange surface area of 0.89 cm2 exhibit a high gas permeability, demonstrating 0.03 mL/min of oxygen flux.141 While these composite membranes have been tested in mini-oxygenators in animals (Figure 4h), it remains to be seen what a full-scale device would look like in terms of priming volume, surface area, pressure drop, and oxygen flux in blood.

Overall, the field of microfluidics offers a lot of promise when it comes to the future of oxygenators for artificial placenta technology. Multiple groups have shown the advantages of microfluidics when it comes to optimizing artificial surface area, priming volume, device resistance, and blood flow path. However, further work needs to be done to optimize the hemocompatibility of microfluidic oxygenators. In addition, it has proven challenging to match hollow-fiber membranes when it comes to fitting a large surface area for gas exchange into a compact device. The average premature infant consumes oxygen at rate of 4–7 mL/min/kg body weight.142 Most microfluidics devices, with the exception of the Dabaghi et al. device,136 have not achieved more than 1 mL/min of flux. These scaling difficulties have thus far prevented microfluidics from being translated to the clinical setting. Of course, scaling up to a device able to support a 1 kg EPT infant is much easier than scaling up to support a 70 kg adult. It is in this population that microfluidic oxygenators may find their niche, where their advantages are more pronounced and their scale-up challenge less daunting.

F. Conclusion

Extreme prematurity affects a significant portion of births in the United States and worldwide. Mechanical ventilation, as the current standard of care, has proven to be insufficient for this population, as a large percentage of these infants either die or are left with severe chronic lung disease. Extracorporeal oxygenation offers an alternative way to provide gas exchange without causing damage to the underdeveloped lungs of these patients, but in its current state, ECLS is challenging to translate to EPT infants. However, improvements in membrane technology have made the creation of an artificial placenta circuit for humans an attainable goal. Hollow-fiber membranes are becoming smaller and more efficient, making them more suitable for use in EPT infants. The emerging field of microfluidic oxygenators shows particular promise due to advantages in gas exchange efficiency and hemocompatibility. For both hollow-fiber and microfluidic oxygenators, improvements in materials engineering, surface coatings, and device design will be critical to development of an artificial placenta for clinical use. Clinical translation of an artificial placenta device would revolutionize the treatment of EPT infants, and perhaps, with this type of technology, we may be able to achieve viability below the current limit of 22 weeks gestation.

Acknowledgements:

DGB is funded via NIH T32 Training Grant (5T32HD049303-13) and the UCSF Department of Pediatrics. ENA and SR are funded by NIH/NIBIB Biodevice Innovation Training Program (R25EB023856), NIH/NCATS UCSF-CTSI (UL1TR001872), and FDA UCSF-Stanford Pediatric Device Consortium (P50FD006424).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References:

- 1.Blencowe H, Cousens S, Oestergaard MZ, Chou D, Moller AB, Narwal R, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: A systematic analysis and implications. The Lancet. 2012; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Walsh MC, et al. Neonatal outcomes of extremely preterm infants from the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics. 2010;126(3):443–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rysavy MA, Li L, Bell EF, Das A, Hintz SR, Stoll BJ, et al. Between-hospital variation in treatment and outcomes in extremely preterm infants. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, Driscoll AK, Drake P. Births: Final data for 2017. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2018. November;67(8):1–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitsett JA, Wert SE. Molecular Determinants of Lung Morphogenesis. In: Chernick V, Wilmott RW, Boat TF, Bush A, editors. Kendig’s Disorders of the Respiratory Tract in Children. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlo WA, Polin RA, Papile LA, Tan R, Kumar P, Benitz W, et al. Respiratory support in preterm infants at birth. Pediatrics. 2014; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slutsky AS, Ranieri VM. Ventilator-induced lung injury. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Partridge EA, Flake AW. The Artificial Womb. In: Fetal Therapy. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coalson JJ. Pathology of new bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Seminars in Neonatology. 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thébaud B, Goss KN, Laughon M, Whitsett JA, Abman SH, Steinhorn RH, et al. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glass HC, Costarino AT, Stayer SA, Brett CM, Cladis F, Davis PJ. Outcomes for extremely premature infants. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2015. June;120(6):1337–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stark A, Eichenwald E. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia: Management. UpToDate. 2019; [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chye JK, Gray PH. Rehospitalization and growth of infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia: A matched control study. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 1995; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith VC, Zupancic JAF, McCormick MC, Croen LA, Greene J, Escobar GJ, et al. Rehospitalization in the first year of life among infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Journal of Pediatrics. 2004; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gross SJ, Iannuzzi DM, Kveselis DA, Anbar RD. Effect of preterm birth on pulmonary function at school age: A prospective controlled study. Journal of Pediatrics. 1998; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krishnan U, Feinstein JA, Adatia I, Austin ED, Mullen MP, Hopper RK, et al. Evaluation and Management of Pulmonary Hypertension in Children with Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. Journal of Pediatrics. 2017; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singer L, Yamashita T, Lilien L, Collin M, Baley J. A longitudinal study of developmental outcome of infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia and very low birth weight. Pediatrics. 1997; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hill JD, O’Brien TG, Murray JJ, Dontigny L, Bramson ML, Osborn JJ, et al. Prolonged Extracorporeal Oxygenation for Acute Post-Traumatic Respiratory Failure (Shock-Lung Syndrome): Use of the Bramson Membrane Lung. New England Journal of Medicine. 1972;286(12):629–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartlett RH, Roloff DW, Cornell RG, Andrews AF, Dillon PW, Zwischenberger JB. Extracorporeal circulation in neonatal respiratory failure: A prospective randomized study. Pediatrics. 1985; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Rourke PP, Crone RK, Vacanti JP, Ware JH, Lillehei CW, Parad RB, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and conventional medical therapy in neonates with persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn: A prospective randomized study. Pediatrics. 1989; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Field DJ, Davis C, Elbourne D, Grant A, Johnson A, Macrae D. UK collaborative randomised trial of neonatal extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Lancet. 1996; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ECLS Registry Report: International Summary (January 2020) [Internet]. Extracorporeal Life Support Organization; 2020. Available from: https://www.elso.org/Registry/Statistics/InternationalSummary.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toomasian JM, Schreiner RJ, Meyer DE, Schmidt ME, Hagan SE, Griffith GW, et al. A polymethylpentene fiber gas exchanger for long-term extracorporeal life support. ASAIO Journal. 2005. July;51(4):390–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brogan T, Annich G, Ellis WC, Haney B, Heard M, Lorusso R, editors. ECMO Specialist Training Manual. 4th ed. Ann Arbor, MI: Extracorporeal Life Support Organization; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Church JT, Kim AC, Erickson KM, Rana A, Drongowski R, Hirschl RB, et al. Pushing the boundaries of ECLS: Outcomes in < 34 week EGA neonates. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2017; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cuevas Guamán M, Akinkuotu AC, Cruz SM, Griffiths PA, Welty SE, Lee TC, et al. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in Premature Infants With Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia. ASAIO journal (American Society for Artificial Internal Organs : 1992). 2018; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sklar MC, Sy E, Lequier L, Fan E, Kanji HD. Anticoagulation practices during venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for respiratory failure a systematic review. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2016. December;13(12):2242–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mazzeffi M, Greenwood J, Tanaka K, Menaker J, Rector R, Herr D, et al. Bleeding, Transfusion, and Mortality on Extracorporeal Life Support: ECLS Working Group on Thrombosis and Hemostasis. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2016;101(2):682–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aubron C, DePuydt J, Belon F, Bailey M, Schmidt M, Sheldrake J, et al. Predictive factors of bleeding events in adults undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Annals of Intensive Care. 2016. December;6(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.ECLS Registry Report: International Summary (July 2019). Ann Arbor, MI: Extracorporeal Life Support Organization; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ki KK, Passmore MR, Chan CHH, Malfertheiner M v, Fanning JP, Bouquet M, et al. Low flow rate alters haemostatic parameters in an ex-vivo extracorporeal membrane oxygenation circuit. Intensive Care Medicine Experimental. 2019; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ballabh P. Intraventricular hemorrhage in premature infants: Mechanism of disease. Pediatric Research. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yeo KT, Thomas R, Chow SSW, Bolisetty S, Haslam R, Tarnow-Mordi W, et al. Improving incidence trends of severe intraventricular haemorrhages in preterm infants <32 weeks gestation: A cohort study. Archives of Disease in Childhood: Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 2020; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gartner LM, Snyder RN, Chabon RS, Bernstein J. Kernicterus: high incidence in premature infants with low serum bilirubin concentrations. Pediatrics. 1970; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barrett CS, Jaggers JJ, Cook EF, Graham DA, Rajagopal SK, Almond CS, et al. Outcomes of neonates undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support using centrifugal versus roller blood pumps. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2012;94(5):1635–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Halloran CP, Thiagarajan RR, Yarlagadda V v, Barbaro RP, Nasr VG, Rycus, et al. Outcomes of Infants Supported with Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Using Centrifugal Versus Roller Pumps: An Analysis from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 2019; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moon YS, Ohtsubo S, Gomez MR, Moon JK, Nose Y. Comparison of Centrifugal and Roller Pump Hemolysis Rates at Low Flow. Artificial Organs. 1996;20(5):579–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Byrnes J, McKamie W, Swearingen C, Prodhan P, Bhutta A, Jaquiss R, et al. Hemolysis during cardiac extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: A case-control comparison of roller pumps and centrifugal pumps in a pediatric population. ASAIO Journal. 2011;57(5):456–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stiller B, Lemmer J, Merkle F, Alexi-Meskishvili V, Weng Y, Hübler M, et al. Consumption of blood products during mechanical circulatory support in children: Comparison between ECMO and a pulsatile ventricular assist device. Intensive Care Medicine. 2004; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bauer K, Linderkamp O, Versmold HT. Systolic blood pressure and blood volume in preterm infants. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1993; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aladangady N, McHugh S, Aitchison TC, Wardrop CAJ, Holland BM. Infants’ blood volume in a controlled trial of placental transfusion at preterm delivery. Pediatrics. 2006; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qiu F, Uluer MC, Kunselman A, Clark JB, Myers JL, Ündar A. Impact of tubing length on hemodynamics in a simulated neonatal extracorporeal life support circuit. Artificial Organs. 2010; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stockman JA, Graeber JE, Clark DA, McClellan K, Garcia JF, Kavey REW. Anemia of prematurity: Determinants of the erythropoietin response. The Journal of Pediatrics. 1984; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Christensen RD, Henry E, Wiedmeier SE, Stoddard RA, Sola-Visner MC, Lambert DK, et al. Thrombocytopenia among extremely low birth weight neonates: Data from a multihospital healthcare system. Journal of Perinatology. 2006; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fletcher K, Chapman R, Keene S. An overview of medical ECMO for neonates. Seminars in Perinatology. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hornick MA, Davey MG, Partridge EA, Mejaddam AY, McGovern PE, Olive AM, et al. Umbilical cannulation optimizes circuit flows in premature lambs supported by the EXTra-uterine Environment for Neonatal Development (EXTEND). Journal of Physiology. 2018; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hornick MA, Mejaddam AY, McGovern PE, Hwang G, Han J, Peranteau WH, et al. Technical feasibility of umbilical cannulation in midgestation lambs supported by the EXTra-uterine Environment for Neonatal Development (EXTEND). Artificial Organs. 2019; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weissman A, Jakobi P, Bronshtein M, Goldstein I. Sonographic measurements of the umbilical cord and vessels during normal pregnancies. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine. 1994; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burton GJ, Jauniaux E. What is the placenta? American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2015; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maltepe E, Fisher SJ. Placenta: The Forgotten Organ. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 2015; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Callaghan JC, de Los Angeles J. Long-term extracorporeal circulation in the development of an artificial placenta for respiratory distress of the newborn. Surgical forum. 1961; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Callaghan JC, de Los Angeles J, Boracchia B, Fisk RL, Hallgren R. Studies in the Development of an Artificial Placenta. Circulation. 1963;27:686–90. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Unno N, Kuwabara Y, Okai T, Kido K, Nakayama H, Kikuchi A, et al. Development of an Artificial Placenta: Survival of Isolated Goat Fetuses for Three Weeks with Umbilical Arteriovenous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. Artificial Organs. 1993; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schoberer M, Arens J, Lohr A, Seehase M, Jellema RK, Collins JJ, et al. Fifty Years of Work on the Artificial Placenta: Milestones in the History of Extracorporeal Support of the Premature Newborn. Artificial Organs. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Metelo-Coimbra C, Roncon-Albuquerque R. Artificial placenta: Recent advances and potential clinical applications. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Partridge EA, Davey MG, Flake AW. Development of the Artificial Womb. Current Stem Cell Reports. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bryner B, Gray B, Perkins E, Davis R, Hoffman H, Barks J, et al. An extracorporeal artificial placenta supports extremely premature lambs for 1 week. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2015;50(1):44–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Capiox Rx Family of Hollow Fiber Oxygenators [Internet]. Terumo Corporation; Available from: http://www.terumo-europe.com/Relevant Product Info/P_CapioxRX_Family_Brochure_CV143GB-1114FK-11(11.14)E.pdf

- 59.Church JT, Coughlin MA, Perkins EM, Hoffman HR, Barks JD, Rabah R, et al. The artificial placenta: Continued lung development during extracorporeal support in a preterm lamb model. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2018; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Arens J, Schoberer M, Lohr A, Orlikowsky T, Seehase M, Jellema RK, et al. NeonatOx: A Pumpless Extracorporeal Lung Support for Premature Neonates. Artificial Organs. 2011; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schoberer M, Arens J, Erben A, Ophelders D, Jellema RK, Kramer BW, et al. Miniaturization: The clue to clinical application of the artificial placenta. Artificial Organs. 2014; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miura Y, Matsuda T, Usuda H, Watanabe S, Kitanishi R, Saito M, et al. A Parallelized Pumpless Artificial Placenta System Significantly Prolonged Survival Time in a Preterm Lamb Model. Artificial Organs. 2016. May;40(5):E61–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Usuda H, Watanabe S, Saito M, Sato S, Musk GC, Fee ME, et al. Successful use of an artificial placenta to support extremely preterm ovine fetuses at the border of viability. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2019; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Partridge EA, Davey MG, Hornick MA, McGovern PE, Mejaddam AY, Vrecenak JD, et al. An extra-uterine system to physiologically support the extreme premature lamb. Nature Communications. 2017. April;8(1):15112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.QUADROX-i Neonatal & Pediatric: Safe, high-performance oxygenators for the smallest patients. Quadrox-i Neonatal and Pediatric. Maquet; [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ghazi-Birry HS, Brown WR, Moody DM, Challa VR, Block SM, Reboussin DM. Human germinal matrix: Venous origin of hemorrhage and vascular characteristics. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 1997; [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bruschettini M, Romantsik O, Zappettini S, Banzi R, Ramenghi LA, Calevo MG. Heparin for the prevention of intraventricular haemorrhage in preterm infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Casa LD, Deaton DH, Ku DN. Role of high shear rate in thrombosis. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2015;61(4):1068–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wellings PJ, Ku DN. Mechanisms of Platelet Capture Under Very High Shear. Cardiovascular Engineering and Technology. 2012; [Google Scholar]

- 70.Virchow R. Gesammelte Abhandlungen zur Wissenschaftlichen Medizen. Frankfurt am Main: Meidinger U Comp. 1856; [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dornia C, Philipp A, Bauer S, Lubnow M, Müller T, Lehle K, et al. Analysis of thrombotic deposits in extracorporeal membrane oxygenators by multidetector computed tomography. ASAIO Journal. 2014. November;60(6):652–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hastings SM, Ku DN, Wagoner S, Maher KO, Deshpande S. Sources of Circuit Thrombosis in Pediatric Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. ASAIO Journal. 2017. September;63(1):86–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Panigada M, L’Acqua C, Passamonti SM, Mietto C, Protti A, Riva R, et al. Comparison between clinical indicators of transmembrane oxygenator thrombosis and multidetector computed tomographic analysis. Journal of Critical Care. 2015;30(2):441.e7–441.e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gartner MJ, Wilhelm CR, Gage KL, Fabrizio MC, Wagner WR. Modeling flow effects on thrombotic deposition in a membrane oxygenator. Artificial Organs. 2000. Jan;24(1):29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pelosi A, Sheriff J, Stevanella M, Fiore GB, Bluestein D, Redaelli A. Computational evaluation of the thrombogenic potential of a hollow-fiber oxygenator with integrated heat exchanger during extracorporeal circulation. Biomechanics and Modeling in Mechanobiology. 2014. April;13(2):349–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gómez Bardón R, Passos A, Piergiovanni M, Balabani S, Pennati G, Dubini G. Haematocrit heterogeneity in blood flows past microfluidic models of oxygenating fibre bundles. Medical Engineering and Physics. 2019;73:30–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mazaheri AR, Ahmadi G. Uniformity of the fluid flow velocities within hollow fiber membranes of blood oxygenation devices. Artificial Organs. 2006;30(1):10–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Linhardt R, Murugesan S, Xie J. Immobilization of Heparin: Approaches and Applications. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 2008;8(2):80–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mahmood S, Bilal H, Zaman M, Tang A. Is a fully heparin-bonded cardiopulmonary bypass circuit superior to a standard cardiopulmonary bypass circuit? Interactive Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery. 2012;14(4):406–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.te Velthuis H, Baufreton C, Jansen PGM, Thijs CM, Hack CE, Sturk A, et al. Heparin coating of extracorporeal circuits inhibits contact activation during cardiac operations. Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 1997;114(1):117–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hein E, Munthe-Fog L, Thiara AS, Fiane AE, Mollnes TE, Garred P. Heparin-coated cardiopulmonary bypass circuits selectively deplete the pattern recognition molecule ficolin-2 of the lectin complement pathway in vivo. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2015. February;179(2):294–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Urlesberger B, Zobel G, Rödl S, Dacar D, Friehs I, Leschnik B, et al. Activation of the clotting system: Heparin-coated versus non coated systems for extracorporeal circulation. International Journal of Artificial Organs. 1997. December;20(12):708–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pappalardo F, della Valle P, Crescenzi G, Corno C, Franco A, Torracca L, et al. Phosphorylcholine coating may limit thrombin formation during high-risk cardiac surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2006;81(3):886–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tevaearai HT, Mueller XM, Tepic S, Cotting J, Boone Y, Montavon PM, et al. Nitric oxide added to the sweep gas infusion reduces local clotting formation in adult blood oxygenators. ASAIO Journal. 2000. November;46(6):719–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sly MK, Prager MD, Li J, Harris FB, Shastri P, Bhujle R, et al. Platelet and Neutrophil Distributions in Pump Oxygenator Circuits. III. Influence of Nitric Oxide Gas Infusion. ASAIO JOURNAL. 1996. September;42(5):M494–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhang H, Annich GM, Miskulin J, Osterholzer K, Merz SI, Bartlett RH, et al. Nitric oxide releasing silicone rubbers with improved blood compatibility: preparation, characterization, and in vivo evaluation. Biomaterials. 2002;23(6):1485–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Annich GM, Meinhardt JP, Mowery KA, Ashton BA, Merz SI, Hirschl RB, et al. Reduced platelet activation and thrombosis in extracorporeal circuits coated with nitric oxide release polymers. Critical Care Medicine. 2000. April;28(4):915–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Amoako KA, Montoya PJ, Major TC, Suhaib AB, Handa H, Brant DO, et al. Fabrication and in vivo thrombogenicity testing of nitric oxide generating artificial lungs. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research - Part A. 2013; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lai A, Demarest CT, Do-Nguyen CC, Ukita R, Skoog DJ, Carleton NM, et al. 72-Hour in vivo evaluation of nitric oxide generating artificial lung gas exchange fibers in sheep. Acta Biomaterialia. 2019; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sundaram HS, Han X, Nowinski AK, Brault ND, Li Y, Ella-Menye JR, et al. Achieving One-Step Surface Coating of Highly Hydrophilic Poly(Carboxybetaine Methacrylate) Polymers on Hydrophobic and Hydrophilic Surfaces. Advanced Materials Interfaces. 2014; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Amoako KA, Sundaram HS, Suhaib A, Jiang S, Cook KE. Multimodal, Biomaterial-Focused Anticoagulation via Superlow Fouling Zwitterionic Functional Groups Coupled with Anti-Platelet Nitric Oxide Release. Advanced Materials Interfaces. 2016; [Google Scholar]

- 92.Malkin AD, Ye SH, Lee EJ, Yang X, Zhu Y, Gamble LJ, et al. Development of zwitterionic sulfobetaine block copolymer conjugation strategies for reduced platelet deposition in respiratory assist devices. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research - Part B Applied Biomaterials. 2018; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Plegue TJ, Kovach KM, Thompson AJ, Potkay JA. Stability of Polyethylene Glycol and Zwitterionic Surface Modifications in PDMS Microfluidic Flow Chambers. Langmuir. 2018; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ukita R, Wu K, Lin X, Carleton NM, Naito N, Lai A, et al. Zwitterionic poly-carboxybetaine coating reduces artificial lung thrombosis in sheep and rabbits. Acta Biomaterialia. 2019; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cornelissen CG, Dietrich M, Gromann K, Frese J, Krueger S, Sachweh JS, et al. Fibronectin coating of oxygenator membranes enhances endothelial cell attachment. BioMedical Engineering Online. 2013; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Polk AA, Maul TM, McKeel DT, Snyder TA, Lehocky CA, Pitt B, et al. A biohybrid artificial lung prototype with active mixing of endothelialized microporous hollow fibers. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 2010; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wiegmann B, von Seggern H, Höffler K, Korossis S, Dipresa D, Pflaum M, et al. Developing a biohybrid lung - sufficient endothelialization of poly-4-methly-1-pentene gas exchange hollow-fiber membranes. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials. 2016; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zwirner U, Höffler K, Pflaum M, Korossis S, Haverich A, Wiegmann B. Identifying an optimal seeding protocol and endothelial cell substrate for biohybrid lung development. Journal of Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. 2018; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pflaum M, Kühn-Kauffeldt M, Schmeckebier S, Dipresa D, Chauhan K, Wiegmann B, et al. Endothelialization and characterization of titanium dioxide-coated gas-exchange membranes for application in the bioartificial lung. Acta Biomaterialia. 2017; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Klein S, Hesselmann F, Djeljadini S, Berger T, Thiebes AL, Schmitz-Rode T, et al. EndOxy: Dynamic Long-Term Evaluation of Endothelialized Gas Exchange Membranes for a Biohybrid Lung. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2020; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lo JH, Bassett EK, Penson EJN, Hoganson DM, Vacanti JP. Gas Transfer in Cellularized Collagen-Membrane Gas Exchange Devices. Tissue Engineering - Part A. 2015; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Menzel S, Finocchiaro N, Donay C, Thiebes AL, Hesselmann F, Arens J, et al. Towards a Biohybrid Lung: Endothelial Cells Promote Oxygen Transfer through Gas Permeable Membranes. BioMed Research International. 2017; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wiegmann B, Figueiredo C, Gras C, Pflaum M, Schmeckebier S, Korossis S, et al. Prevention of rejection of allogeneic endothelial cells in a biohybrid lung by silencing HLA-class I expression. Biomaterials. 2014; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Soares JS, Sheriff J, Bluestein D. A novel mathematical model of activation and sensitization of platelets subjected to dynamic stress histories. Biomechanics and Modeling in Mechanobiology. 2013;12(6):1127–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nobili M, Sheriff J, Morbiducci U, Redaelli A, Bluestein D. Platelet activation due to hemodynamic shear stresses: Damage accumulation model and comparison to in vitro measurements. ASAIO Journal. 2008;54(1):64–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Fuchs G, Berg N, Broman LM, Prahl Wittberg L. Flow-induced platelet activation in components of the extracorporeal membrane oxygenation circuit. Scientific Reports. 2018. September;8(1):13985–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Federspiel W, Henchir K. Lung, Artificial: Basic Principles and Current Applications. In: Encyclopedia of Biomaterials and Biomedical Engineering, Second Edition - Four Volume Set. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Weibel ER. The Pathway for Oxygen: Structure and Function in the Mammalian Respiratory System. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 109.L’Acqua C, Hod E. New perspectives on the thrombotic complications of haemolysis. British Journal of Haematology. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Rudolph AM, Heymann MA. The Fetal Circulation. Annual Review of Medicine. 1968; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Reng M, Philipp A, Kaiser M, Pfeifer M, Gruene S, Schoelmerich J. Pumpless extracorporeal lung assist and adult respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet. 2000;356(9225):219–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Mayes J, Niranjan G, Dark J, Clark S. Bridging to lung transplantation for severe pulmonary hypertension using dual central Novalung lung assist devices. Interactive Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery. 2016;22(5):677–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Fischer S, Simon AR, Welte T, Hoeper MM, Meyer A, Tessmann R, et al. Bridge to lung transplantation with the novel pumpless interventional lung assist device NovaLung. Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2006. March;131(3):719–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]