Abstract

From September 1990 to October 1990, 15 patients who were admitted to four different departments of the National Taiwan University Hospital, including nine patients in the emergency department, three in the hematology/oncology ward, two in the surgical intensive care unit, and one in a pediatric ward, were found to have positive blood (14 patients) or pleural effusion (1 patient) cultures for Bacillus cereus. After extensive surveillance cultures, 19 additional isolates of B. cereus were recovered from 70% ethyl alcohol that had been used as a skin disinfectant (14 isolates from different locations in the hospital) and from 95% ethyl alcohol (5 isolates from five alcohol tanks in the pharmacy department), and 10 isolates were recovered from 95% ethyl alcohol from the factory which supplied the alcohol to the hospital. In addition to these 44 isolates of B. cereus, 12 epidemiologically unrelated B. cereus isolates, one Bacillus sphaericus isolate from a blood specimen from a patient seen in May 1990, and two B. sphaericus isolates from 95% alcohol in the liquor factory were also studied for their microbiological relatedness. Among these isolates, antibiotypes were determined by using the disk diffusion method and the E test, biotypes were created with the results of the Vitek Bacillus Biochemical Card test, and random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) patterns were generated by arbitrarily primed PCR. Two clones of the 15 B. cereus isolates recovered from patients were identified (clone A from 2 patients and clone B from 13 patients), and all 29 isolates of B. cereus recovered from 70 or 95% ethyl alcohol in the hospital or in the factory belonged to clone B. The antibiotype and RAPD pattern of the B. sphaericus isolate from the patient were different from those of isolates from the factory. Our data show that the pseudoepidemic was caused by a clone (clone B) of B. cereus from contaminated 70% ethyl alcohol used in the hospital, which we successfully traced to preexisting contaminated 95% ethyl alcohol from the supplier, and by another clone (clone A) without an identifiable source.

Bacillus cereus, a well-known pathogen causing food poisoning, and other Bacillus species have been reported to cause bacteremia, endocarditis, pneumonia, meningitis, and other invasive infections, particularly in immunocompromised patients (5, 17, 19). However, due to the wide distribution of Bacillus spores in nature (in soil, dust, water, and other animal sources) and in the hospital environment, this organism is usually considered a saprophyte or contaminant when detected in clinical specimens of different sources (5, 18). Dissemination of Bacillus species among hospitalized patients has previously been reported (1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 10, 11, 13, 14, 17, 18, 20, 21). Most of these events were later considered nosocomial pseudoepidemics and were frequently secondary to the contamination of equipment and environments such as a fiber-optic bronchoscope, an air filtration system, a ventilator, a water bath, and a radiometric blood culture analyzer in microbiology laboratories (4, 6, 7, 11, 18, 20, 21).

Previous reports showed that 11% of the nosocomial outbreaks were in fact pseudoepidemics (in which an organism is isolated above the normal baseline frequency) (15, 17, 22). Recognizing and tracking the origin of such pseudoepidemics is difficult and requires the aid of attending physicians, infection control personnel, and clinical microbiologists (12, 14). To the best of our knowledge, only one previous report has described the application of molecular analysis, i.e., pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), to successfully identify a pseudo-outbreak due to B. cereus and to trace the source of contamination (11).

In this article, we present antibiotypes determined by the disk diffusion method and the E test, biotypes created by the use of the Vitek Bacillus Biochemical Card, and random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) patterns generated by arbitrarily primed PCR (APPCR) of 59 isolates of Bacillus species, with which we successfully investigated a nosocomial pseudoepidemic caused by B. cereus. The source was found to be contaminated 70% ethyl alcohol used as a skin disinfectant in the hospital and preexisting contamination by this organism of 95% ethyl alcohol from the supplier.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Background and investigation of pseudoepidemic.

From 10 September 1990 to 5 October 1990, 15 isolates of B. cereus were recovered from 14 blood specimens and 1 pleural effusion specimen from 15 patients who were treated at National Taiwan University Hospital, a 2,000-bed teaching hospital in northern Taiwan. The high frequency of blood cultures positive for B. cereus during this time period was very unusual because there had been no B. cereus isolation from blood cultures from 1 January 1990 to 31 August 1990 in the hospital. Accordingly, a pseudoepidemic rather than a true infection due to this organism was suggested by the infection control committee, and an investigation was begun. Because the majority of the isolations of B. cereus occurred in the emergency department (10 patients) and were from blood specimens of adult patients (13 patients) (Table 1), it was first speculated that the contamination might have occurred during the procedures of sampling of blood specimens for cultures and inoculation of the blood into blood culture bottles in the emergency department. Environmental sampling of cultures, including skin disinfectants (70% alcohol, tincture iodine, and 10% povidone iodine), gloves used while drawing blood, and the rubber diaphragms of the BACTEC 6A aerobic and 7A anaerobic blood culture bottles (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, Md.), was first done in the emergency department on 20 September 1990.

TABLE 1.

Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of 50 isolates of Bacillus species

| Isolate (location)a | Species | Date of isolation (day/mo/yr) | Source | Antibiotype as determined by:

|

Biotype as determined by Vitek Bacillus card | RAPD pattern as determined with OPA-1 or ERIC1 primer | Clone (B. cereus) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disk diffusion | E test | |||||||

| Isolates from patients | ||||||||

| P1 (OW) | B. sphaericus | 1/5/1990 | Blood | 2 | III | C | f | |

| P2 (OW) | B. cereus | 20/9/1990 | Pleural effusion | 1 | I | A | a | A |

| P3 (SICU) | B. cereus | 10/9/1990 | Blood | 1 | II | B | b | B |

| P4 (ED) | B. cereus | 19/9/1990 | Blood | 1 | II | B | b | B |

| P5 (ED) | B. cereus | 5/10/1990 | Blood | 1 | I | A | a | A |

| P6 (OW) | B. cereus | 20/9/1990 | Blood | 1 | II | B | b | B |

| P7 (PW) | B. cereus | 20/9/1990 | Blood | 1 | II | B | b | B |

| P8 (ED) | B. cereus | 20/9/1990 | Blood | 1 | II | B | b | B |

| P9 (ED) | B. cereus | 20/9/1990 | Blood | 1 | II | B | b | B |

| P10 (ED) | B. cereus | 20/9/1990 | Blood | 1 | II | B | b | B |

| P11 (ED) | B. cereus | 20/9/1990 | Blood | 1 | II | B | b | B |

| P12 (ED) | B. cereus | 4/10/1990 | Blood | 1 | II | B | b | B |

| P13 (OW) | B. cereus | 4/10/1990 | Blood | 1 | II | B | b | B |

| P14 (ED) | B. cereus | 5/10/1990 | Blood | 1 | II | B | b | B |

| P15 (ED) | B. cereus | 5/10/1990 | Blood | 1 | II | B | b | B |

| P16 (ED) | B. cereus | 5/10/1990 | Blood | 1 | II | B | b | B |

| Isolates from alcohol used in hospital | ||||||||

| S1–S9 (ED) | B. cereus | 8/10/1990 | 70% alcohol | 1 | II | B | b | B |

| S10–S14 (OW) | B. cereus | 8/10/1990 | 70% alcohol | 1 | II | B | b | B |

| N1–N5 (PD) | B. cereus | 12/10/1990 | 95% alcohol | 1 | II | B | b | B |

| Isolates from factory | ||||||||

| L1–L10 | B. cereus | 23/10/1990 | 95% alcohol | 1 | II | B | b | B |

| L11–12 | B. sphaericus | 23/10/1990 | 95% alcohol | 2 | IV | C | g | |

| Epidemiologically unrelated isolates | ||||||||

| U-1 | B. cereus | 9/3/1998 | Blood | 1 | V | B | c | C |

| U-2 | B. cereus | 13/8/1998 | Blood | 1 | VI | A | d | D |

| U-3 | B. cereus | 15/8/1998 | Blood | 1 | VII | B | e | E |

OW, oncology ward; SICU, surgical intensive care unit; ED, emergency department; PW, pediatric ward; PD, pharmacy department.

After the isolation of B. cereus from only the 70% alcohol used in the emergency department on the second day of the investigation, additional samples for surveillance cultures included the 70% ethyl alcohol used in the hematology/oncology ward (five samples from five bottles), the surgical intensive care unit (one sample), the pediatric ward (two samples), and other wards (eight samples), as well as 95% ethyl alcohol (three samples from opened tanks and five from five unopened tanks) placed in the pharmacy department (the 70% ethyl alcohol used in each ward was prepared from 95% ethyl alcohol obtained from the pharmacy department) and from the factory (10 samples from tanks of 95% alcohol). All specimens (0.1 ml of undiluted, 10-fold diluted, and 25-fold diluted 70 or 95% ethyl alcohol and swabs of septa of blood culture bottles) were inoculated onto Trypticase soy agar supplemented with 5% sheep blood agar (BBL Microbiology Systems) and were incubated at 37°C in ambient air for 24 h.

Identification of isolates.

A total of 46 isolates of Bacillus species were recovered during the investigation period (Table 1). They included 15 isolates of B. cereus from 15 patients, 14 isolates of B. cereus from the 70% ethyl alcohol used in different wards, 5 isolates of B. cereus from the 95% ethyl alcohol from the pharmacy department, and 10 isolates of B. cereus and 2 isolates of B. sphaericus from the factory that produced the alcohol. A preserved strain of B. sphaericus from a blood specimen of a patient treated at the hospital in May 1990 was also included in this study. These 47 isolates were identified as Bacillus species by conventional biochemical tests (19). Three stock B. cereus isolates recovered from blood specimens of three patients treated in 1998 were also studied and were considered epidemiologically unrelated strains (U1 to U3).

Biotyping.

The Vitek Bacillus Biochemical Card (bioMerieux Vitek, Inc., Hazelwood, Mo.) was used as a supplemental method for identification to species level and biotyping of these 50 isolates (47 isolates of B. cereus and 3 isolates of B. sphaericus) (Table 1). The procedure for the performance of the Vitek Card test was in accordance with that described by the manufacturer. Trypticase soy agar without blood was used for the preparation of pure cultures for testing.

Antibiotyping.

Susceptibility testing of all isolates of Bacillus species was performed by the disk diffusion method and the E test (PDM Epsilometer; AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) (8). For disk diffusion susceptibility testing, 10 antimicrobial agents were tested: penicillin (10 U per disk), oxacillin (1 μg), cephalothin (30 μg), cefamandol (30 μg), erythromycin (15 μg), clindamycin (2 μg), tetracycline (30 μg), chloramphenicol (30 μg), gentamicin (10 μg), and vancomycin (30 μg) (BBL Microbiology Systems). For the E-test MIC determinations, 14 antibiotic strips were used: penicillin, ampicillin, ampicillin-sulbactam, cefazolin, cefotaxime, cefepime, imipenem, erythromycin, tetracycline, chloramphenicol, gentamicin, vancomycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and ciprofloxacin. The isolates were grown overnight on Trypticase soy agar plates supplemented with 5% sheep blood (BBL Microbiology Systems) at 37°C. Inocula were prepared by suspending the freshly grown bacteria in sterile normal saline adjusted to a 0.5 McFarland standard followed by direct inoculation onto Mueller-Hinton agar (BBL Microbiology Systems). The diameters of inhibition zones and the MICs were read after 16 to 18 h of incubation in ambient air. Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213 and Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212 were used as control strains in each set of tests.

For antibiotypes determined by the disk diffusion method, categorization of susceptibility and resistance of these isolates to antimicrobial agents followed the guidelines for Staphylococcus species provided by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (16). Disk antibiotypes of the isolates were considered identical if they were in the same categories (resistant or susceptible) of susceptibility. E-test antibiotypes of the isolates were considered different if the discrepancies in MICs of at least one of the antimicrobial agents tested were ≧2 dilutions; otherwise, they were considered identical (8).

RAPD patterns.

The method used to extract chromosomal DNA of the isolates and the PCR conditions used for determination of the RAPD patterns generated by APPCR of the isolates were as described previously (8, 9). In addition to the 50 isolates of Bacillus species shown in Table 1, nine epidemiologically unrelated B. cereus isolates recovered from patients treated at the hospital from 1998 to 1999 were also included in the RAPD analysis. Two oligonucleotide primers were used, ERIC1 (5′-GTGAATCCCCAGGAGCTTACAT-3′) and OPA-1 (5′-CAGGCCCTTC-3′), which were chosen from 20 primers in a kit (OPA-1 to OPA-20) purchased from Operon Technologies, Inc. (Alameda, Calif.). For interpreting results of RAPD analysis, patterns having both faint and intense bands with the same mobility were considered identical; otherwise, they were considered different (8, 9).

Clonality.

Isolates having identical antibiotypes, biotypes, and RAPD patterns were considered to belong to the same clone; otherwise, they were considered to belong to different clones.

RESULTS

Characterization of patients.

Of the 15 patients, 4 had underlying malignancies (leukemia or lymphoma), 2 had cirrhosis of the liver, 1 had diabetes, and the other 8 patients had no underlying diseases. All patients had fevers when blood cultures were taken, three had pneumonia with unknown etiology, two had urinary tract infections, one each had pneumonia due to Mycoplasma pneumoniae, viral encephalitis, acute gastroenteritis, and liver abscess. The other six patients had no obvious infectious foci, including three patients with chemotherapy-induced neutropenia. One set of blood cultures (5 ml each in a BACTEC 6A aerobic culture bottle and a 7A anaerobic culture bottle) was from samples drawn from 10 patients, and two sets of blood cultures were from samples drawn from the other 4 patients. B. cereus grew in only one BACTEC 6A bottle for each patient. No coisolates from blood specimens from these patients were recovered. These patients all received a variety of antibiotics (erythromycin, β-lactams, and aminoglycosides), which were active in vitro against the isolates, and all recovered.

Bacterial isolates.

All B. cereus isolates were gram-positive bacilli with ellipsoidal and centrally located spores and were positive for catalase reaction. Colonies grown on the Trypticase soy agar supplemented with 5% sheep blood agar had a slightly green ground-glass appearance and were β-hemolytic. All B. cereus isolates yielded positive lecithinase reactions on egg yolk agar (BBL Microbiology Systems). Isolates of B. sphaericus had nonhemolytic colonies on Trypticase soy agar supplemented with 5% sheep blood agar and were negative for lecithinase activity. Colonies of isolate P1 were large (4 to 8 mm in diameter), swarming, and slightly greenish after 24 h of incubation in ambient air on Trypticase soy agar with 5% sheep blood, in contrast to the whitish and nonswarming colonies of isolates L11 and L12.

Biotypes.

As shown in Table 1, 44 isolates were identified as B. cereus: the probability of identification was 86% for 42 isolates (biotype B) and 99% for two isolates (biotype A). Three isolates (P1, L11, and L12) were identified as B. sphaericus (probabilities of identification, 99%) with identical biotypes (biotype C). Biotype A B. cereus isolates utilized sucrose but biotype B isolates did not. Two of the three epidemiologically unrelated isolates belonged to biotype B and one belonged to biotype A.

Antibiotypes.

Among the 50 isolates of Bacillus species, three disk antibiotypes and seven E-test antibiotypes were identified (Table 1). Of the 47 B. cereus isolates, one disk antibiotype and five E-test antibiotypes were found (Tables 1 and 2). Penicillin and all cephalosporins tested had poor activities against all isolates of B. cereus. However, the activities of erythromycin, chloramphenicol, glycopeptides, gentamicin, and ciprofloxacin against B. cereus isolates were good. The disk and E-test antibiotypes of the B. sphaericus isolate recovered from the patient (patient 1) were different from those of the isolates from the 95% alcohol from the factory.

TABLE 2.

Susceptibilities to 16 antimicrobial agents of 50 isolates of Bacillus species identified by antibiotype

| Antimicrobial agent | MIC (μg/ml) for Bacillus sp. E-test antibiotype:

|

Result for Bacillus sp. disk antibiotypea:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | 1 | 2 | |

| Penicillin | 16 | 64 | 16 | 4 | 4 | ≥256 | 4 | R | R |

| Ampicillin | ≥256 | ≥256 | 8 | 2 | 8 | ≥256 | 64 | R | S |

| Ampicillin-sulbactam | 4 | 32 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 32 | 4 | ||

| Cefazolin | 64 | ≥256 | 8 | 2 | 64 | ≥256 | 128 | R | S |

| Cefotaxime | 128 | ≥256 | 4 | 0.5 | 32 | ≥256 | 32 | ||

| Cefepime | ≥256 | 64 | 4 | 0.25 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ≥256 | ||

| Imipenem | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 1 | 2 | 4 | ||

| Chloramphenicol | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.25 | 0.25 | S | S |

| Erythromycin | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.5 | S | S |

| Gentamicin | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | S | S |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | ≥32 | ≥32 | ≥32 | ≥32 | ≥32 | ≥32 | ≥32 | ||

| Vancomycin | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | S | S |

| Teicoplanin | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Ciprofloxacin | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 4 | 8 | 4 | ||

| Minocycline | S | S | |||||||

| Tetracycline | S | S | |||||||

R, resistant; S, susceptible.

RAPD patterns.

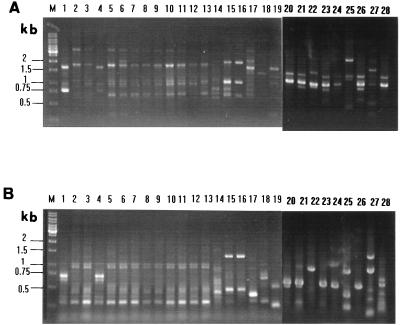

For the 44 B. cereus isolates recovered in 1990, two RAPD patterns were identified: pattern a (2 isolates) and pattern b (42 isolates) (Table 1 and Fig. 1). RAPD patterns of the two B. sphaericus isolates (pattern g) recovered from the factory were identical but were different from that of the patient’s isolate (pattern f) (Fig. 1). The 12 epidemiologically unrelated strains of B. cereus had RAPD patterns different from those of all B. cereus isolates recovered in 1990 (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

RAPD patterns of the 19 isolates of Bacillus species generated by APPCR with the primers OPA-1 (A) and ERIC1 (B). Lanes: M, molecular size marker; 1 to 13, B. cereus isolates P2 to P5, P8, P9, P12 to P15, S1, N1, and L1, respectively; 14 to 16, B. sphaericus isolates P1, L11, and L12, respectively; 17 to 19, isolates U1 to U3; 20 to 28, nine additional epidemiologically unrelated B. cereus isolates (see Table 1).

Clonality.

Based on the E-test antibiotypes, colonial morphotypes and biotypes, and RAPD patterns of the isolates recovered during this outbreak, two clones (clones A and B) among the 44 isolates of B. cereus and two clones of B. sphaericus were identified (Table 1).

Control of the pseudoepidemic.

The factory was informed of the contamination of the 95% ethyl alcohol. An extensive sterilization (autoclaving or gas sterilization) of tanks in the factory was performed. All contaminated alcohol in the hospital was replaced. A standardized procedure for skin disinfection during venopunctures or percutaneous aspiration for physicians and nurses was reinforced, i.e., 10% povidone iodine should be the last step of skin disinfection (not 70% ethyl alcohol) and should remain on the puncture site for at least 1 min before blood drawing. Since these changes were implemented, no further isolates of B. cereus have been recovered from the 70 or 95% ethyl alcohol in the wards, emergency department, or pharmacy department, and no blood cultures were positive for this organism during the 6 months following the investigation.

DISCUSSION

Though Bacillus species has frequently been reported to cause nosocomial pseudobacteremia or pseudo-outbreaks, few previous reports have used molecular methods to document the clonality of the epidemic strains and to trace the source of contamination (11). Among these pseudoepidemics due to Bacillus species, B. cereus was identified on a few occasions and has been demonstrated to be associated with contamination of air filtration systems in pediatric and maternity units, ventilator equipment in an intensive care unit, and a water bath in a microbiology laboratory (1, 4, 11, 14, 20). Two important points have been elucidated in the present study. First, this is the first report to document that a nosocomial pseudoepidemic caused by B. cereus was due to contaminated ethyl alcohol used as a skin disinfectant and successfully traced back to the source of contamination from the alcohol supplier outside the hospital. Second, RAPD analysis by the APPCR technique and MIC antibiotyping provided considerable discriminatory power and were superior to biotyping by the Vitek Bacillus Biochemical Card for defining the clonality of B. cereus and B. sphaericus isolates.

The BACTEC blood culture systems have been implicated in several pseudoepidemics involving spore-forming bacteria (2, 3, 7, 12, 20, 21). These organisms, for example, Bacillus species and Clostridium species, might gain entrance into the blood culture bottles via different routes. The contaminant sources of Bacillus spores include disinfectants, boiling water baths and other laboratory areas, rubber gloves, and dust on the stoppers of the blood culture bottles (2, 7, 20). Among the disinfectants commonly used in hospitals, 70 to 90% ethyl alcohol is an excellent intermediate-level germicide but it is not a sporocide. Spore-forming bacteria, such as Bacillus species and Clostridium species, can survive in 70 or 90% ethyl alcohol (2, 7, 12, 15, 22). Iodine-containing disinfectant has reliable sporicidal activity (2, 3). However, instructions for the operation of the BACTEC radiometric or nonradiometric systems, such as BACTEC 460, 660, and 860, specify that the rubber diaphragm of each blood culture bottle should be cleaned with alcohol rather than iodine before inoculation of the blood specimen. One previous report described a Bacillus species pseudobacteremia that resulted from the contamination of alcohol cotton swabs used to disinfect blood culture bottles (2). The author further demonstrated that the organism persisted for at least 4 weeks in a cotton swab immersed in 70% ethyl alcohol. Our finding supports his observation because the epidemic strain (clone B) survived in either 70 or 95% ethyl alcohol for at least 28 days (10 September to 8 October). However, in Berger’s study (2), the Bacillus species was thought to have originated from the contaminated cotton swabs rather than from contaminated alcohol.

The most important factor for early investigation and identification of a pseudoepidemic is the ability to recognize a baseline recovery rate for all organisms (12, 15, 22). For Bacillus species, a low frequency of contamination in blood cultures is not uncommon, and its smoldering existence at low levels for long periods of time in hospitals allows easy or early identification of a pseudoepidemic until higher frequencies of isolations are recognized (15). In the present study, eight isolates (seven from blood specimens and one from pleural effusion) of B. cereus were recovered during a 2-day period. The rarity of B. cereus as a pathogen was recognized and was consistent with the zero rate of isolation for this organism from blood cultures in the preceding eight months in the hospital, which led to the conclusion after the recovery of the eight isolates that there was a pseudoepidemic involving some form of culture contamination. In fact, a 9-day delay in the identification of the pseudoepidemic existed in this study.

It is unclear why only 15 patients had blood cultures positive for B. cereus in this study. The contaminated alcohol was found in many locations of the hospital. In addition, from 10 September to 5 October, at least 300 blood specimens were collected from patients with whom the contaminated alcohol might have been used as a skin disinfectant. The inconsistencies in skin disinfection procedures (some nurses or physicians used 10% povidone iodine rather than 70% ethyl alcohol as the last step of skin disinfection) might have contributed to the low number of patients involved in this epidemic.

Among the molecular typing methods used for tracing the source of contamination, PFGE analysis has been applied successfully to investigate pseudoepidemics caused by a variety of organisms, including B. cereus (11, 15). However, this technique is time-consuming and instrument dependent, and its discriminatory power depends on the restriction enzyme chosen (11). RAPD patterns generated by APPCR, a time-saving and easy-to-perform technique, were demonstrated in this study to be a highly discriminatory method for the epidemiological investigation of infections or outbreaks due to B. cereus.

With the extensive use of alcohol as a skin disinfectant, it is critical that medical personnel be aware that ethyl alcohol (70 or 95%) may contain B. cereus, which can contaminate specimens collected for microbiological cultures. Our experience shows that B. cereus can survive for a long time in alcohol and demonstrates that this organism has the potential to cause a pseudoepidemic due to contamination. Furthermore, the application of molecular typing and MIC antibiotyping clearly defined clonality among the isolates and indicated that a common source of contamination, originating in alcohol from the supplier, was responsible for this pseudoepidemic.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barrie D, Wilson J A, Hoffman P N, Kramer J M. Bacillus cereus meningitis in two neurosurgical patients: an investigation into the source of the organism. J Infect. 1992;25:291–297. doi: 10.1016/0163-4453(92)91579-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger S A. Pseudobacteremia due to contaminated alcohol swab. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;18:974–975. doi: 10.1128/jcm.18.4.974-975.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berkleman R L, Lewin S, Allen J R, Anderson R L, Budnick L D, Shapiro S, Friedman S M, Nicholas P, Holzman R, Haley R W. Pseudobacteremia attributed to contamination of povidone-iodine with Pseudomonas cepacia. Ann Intern Med. 1981;95:32–36. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-95-1-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryce E A, Smith J A, Tweeddale M, Andruschak B J, Maxwell M R. Dissemination of Bacillus cereus in an intensive care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1993;14:459–462. doi: 10.1086/646779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drobniewski F A. Bacillus cereus and related species. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1993;6:324–338. doi: 10.1128/cmr.6.4.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldstein B, Abrutyn E. Pseudo-outbreak of Bacillus species: related to fiberoptic bronchoscopy. J Hosp Infect. 1985;6:194–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gurevich I, Tafuro P, Krystofiak S P, Kalter R D, Cunha B A. Three clusters of Bacillus pseudobacteremia related to a radiometric blood culture analyzer. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1984;5:71–74. doi: 10.1017/s0195941700058975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsueh P R, Teng L J, Yang P C, Chen Y C, Ho S W, Luh K T. Persistence of a multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa clone in an intensive care unit. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1347–1351. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.5.1347-1351.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsueh P R, Teng L J, Ho S W, Hsieh W C, Luh K T. Clinical and microbiological characteristics of Flavobacterium indologenes infections associated with indwelling devices. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1908–1913. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.8.1908-1913.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lettau L A, Benjamin D, Cantrell F, Potts D W, Boggs J M. Bacillus species pseudomeningitis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1988;9:394–397. doi: 10.1086/645897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu P Y F, Ke S C, Chen S L. Use of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis to investigate a pseudo-outbreak of Bacillus cereus in a pediatric unit. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1533–1535. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1533-1535.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maki D G. Through a glass darkly: nosocomial pseudoepidemics and pseudobacteremias. Arch Intern Med. 1980;140:26–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mermel L A, Josephson S L, Giorge C. A pseudo-epidemic involving bone allografts. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1994;15:757–758. doi: 10.1086/646853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrell R M, Jr, Wasilauskas B L. Tracking laboratory contamination by using a Bacillus cereus pseudoepidemic as an example. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1469–1473. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.6.1469-1473.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris T, Brecher S M, Fitzsimmons D, Durbin A, Arbeit R D, Maslow J N. A pseudoepidemic due to laboratory contamination deciphered by molecular analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1995;16:82–87. doi: 10.1086/647061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance standard for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Eighth informational supplement. M100-S8. Wayne, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richard V, van der Auwera P, Snoeck R, Daneau D, Meunier F. Nosocomial bacteraemia caused by Bacillus species. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1988;7:783–785. doi: 10.1007/BF01975049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richardson A J, Rothburn M M, Roberts C. Pseudo-outbreak of Bacillus species: related to fiberoptic bronchoscopy. J Hosp Infect. 1986;7:208–210. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(86)90068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turnbull P C B, Kramer J M. Bacillus. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yoken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 6th ed. Washington, D.C: ASM Press; 1995. pp. 349–356. [Google Scholar]

- 20.York M K. Bacillus species pseudobacteremia traced to contaminated gloves used in collection of blood from patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2114–2116. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.9.2114-2116.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Youngs E R, Roberts C, Kramer J M, Gillbert R J. Dissemination of Bacillus cereus in a maternity unit. J Infect. 1985;10:228–232. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(85)92538-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weinstein R A, Stamm W E. Pseudoepidemics in hospital. Lancet. 1977;ii:862–864. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)90793-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]