Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Direct Primary Care (DPC) is a relatively new primary care practice model in which patients receive unlimited access to a defined set of primary care services in exchange for a monthly practice-specific membership fee. DPC is a bottom-up physician-driven approach in contrast to typical top-down insurer-centric healthcare delivery reform efforts. The degree to which physicians are aware of this practice model and whether they believe it addresses two key challenges facing primary care, access and administrative burden, are unclear.

METHODS

An online survey was distributed in July 2017 to 672 members of a research marketing sample of the American Academy of Family Physicians (n=225; response rate 33%). Based on AAFP definitions, the survey consisted of both open- and close-ended questions that gauged family physicians’ awareness of DPC, as well as their perceptions about the model.

RESULTS

Most respondents (85%) had heard of DPC and 8% practised in a DPC model at the time of the survey. In general, respondents reported that DPC can offer positive outcomes through lower administrative burden for physicians, improved doctor–patient relationships, and better access. Respondents also suggested DPC may result in improved patient health outcomes and lower overall healthcare spending. Respondents’ concerns included inappropriateness of the model for vulnerable populations and physician shortages. Survey responses differed depending on whether the respondent practised in a DPC model. DPC physicians had a more favorable view of the model and were focused on benefits to patients rather than benefits to physicians.

CONCLUSIONS

Any changes to practice models will require a better understanding of clear definitions of practice models. Further education is required about the specific benefits to vulnerable patients and practice standards. As the perceptions of DPC vary by practice experience, DPC physicians appear to be strong potential advocates of the model.

Keywords: primary care, family medicine, physician perspectives, physician survey, alternative models of care delivery

INTRODUCTION

Despite widespread agreement that the availability of robust primary care is critical to the health of patients and the performance of the healthcare system overall1–3, primary care faces several difficult challenges, including lack of adequate access for many patients4–6, and high levels of administrative burden leading to both physician burnout and career dissatisfaction7–12. While alternative models of primary care delivery, such as Direct Primary Care (DPC), offer the potential to mitigate these challenges, less is known about physicians’ knowledge and perspectives on the relevance of new approaches to care. Accordingly, this study uses a sample of family physicians to explore their understanding and interest in adopting a DPC approach and how it varies by their current practice model.

DPC is a primary care delivery model characterized by enhanced access to care13; DPC patient panels are roughly one-third to one-fourth the size of typical PCP patient panels and DPC physicians spend a smaller portion of their time on administrative tasks14,15. In a policy statement supporting DPC in December 2017, the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) found DPC to be consistent with the Academy’s advocacy to protect and enhance ‘the intrinsic power of the relationship between a patient and his/her family physician to improve health outcomes and lower overall healthcare costs’. A body of literature connects various aspects of the doctor–patient relationship and trust with patient health outcomes such as use of preventive services, treatment adherence, reduced ED visits and hospitalizations, and lower expenditures16–19. The DPC model appears to show considerable growth over the past several years; while there is no official registry of DPC practices, an unofficial source showed 125 practices in 2014, 620 in 2017 and over 1500 in 202120,21.

Several articles and commentaries suggest that DPC practices have benefits specific to physicians, as well as to patients. For example, emerging research shows the potential for improved physician satisfaction through patient engagement and shared decision making, increased time to develop personal relationships and improvement in the quality of care22–25. Additionally, DPC models have the potential to reduce administrative burden for physicians. DPC is a decentralized, physician-driven model of primary care delivery compared to other more common delivery reform efforts that tend to be more centralized and bureaucratic. For example, delivery reform efforts such as patient-centered medical homes and accountable care organizations are characterized by guidelines and oversight, which may serve patients, but may also be associated with high administrative burden among physicians due to their numerous documentation and reporting requirements8,9,26. In contrast, there is no national DPC organization to define requirements or practice rules, and there are no documentation or reporting requirements associated with the DPC model, which may reduce physician administrative burden but may also have implications for practice standards.

This study gauges the awareness of DPC among a sample of family physicians. Specifically, the objective is to understand whether physicians are aware of DPC and if they view DPC as a model with potential benefits. We explore physician perceptions of DPC patient care and their understanding of the model. Next, we aim to understand physician perceptions about the model’s potential to increase professional satisfaction. Finally, we compare responses by the respondent’s practice model (DPC compared to non-DPC) to describe characteristics germane to both groups.

There remains limited visibility of the DPC model and it is unclear how physicians understand or interpret the potential advantages or challenges associated with this approach. Physician perspectives about DPC are important for several reasons. First, physician-level knowledge about the structure and definitions of a DPC model will provide information about whether physicians accurately understand the model. Second, if uptake and/or modifications to the DPC model are to increase, it remains important to understand how family medicine physicians perceive advantages and disadvantages of the model. Questions about whether physicians perceive that DPC might improve career satisfaction or improve patient access to primary care present an opportunity to assess the potential future growth of the DPC model in the US. Third, research consistently shows that administrative burden (leading to physician burnout and career dissatisfaction) and lack of adequate access to primary care for vulnerable patients remain key problems in primary care4–12. Identifying the differences in perceptions among DPC compared to non-DPC physicians will highlight whether those currently in the model exhibit more or less favorable perceptions of a DPC approach.

METHODS

We developed a survey that was distributed online by the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) during the week of 17 July 2017. Participants were self-selected through their participation in the Member Insight Exchange (MIE), the marketing research online community of the AAFP, which had a total of 672 members. The sampling frame included all MIE members. Results of MIE surveys, while not fully generalizable, provide a snapshot of views and practice patterns of AAFP members27,28. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Kansas Medical Center determined the study is exempt from human subject protection review.

Most survey questions had a small number of fixed responses and respondents had an opportunity to submit written responses to open-ended questions. Items elicited physicians’ perceptions about: 1) patients’ understanding of DPC, 2) the financial sustainability of DPC practice, 3) patient health outcomes in DPC, and 4) quality of care in DPC. Respondents were first asked whether they have heard of the DPC model and whether they currently practise in this model; they were then asked to choose the best definition of DPC from a short list in which generally accepted definitions of DPC, patient centered medical homes (PCMHs), and other primary care delivery models, were provided as options.

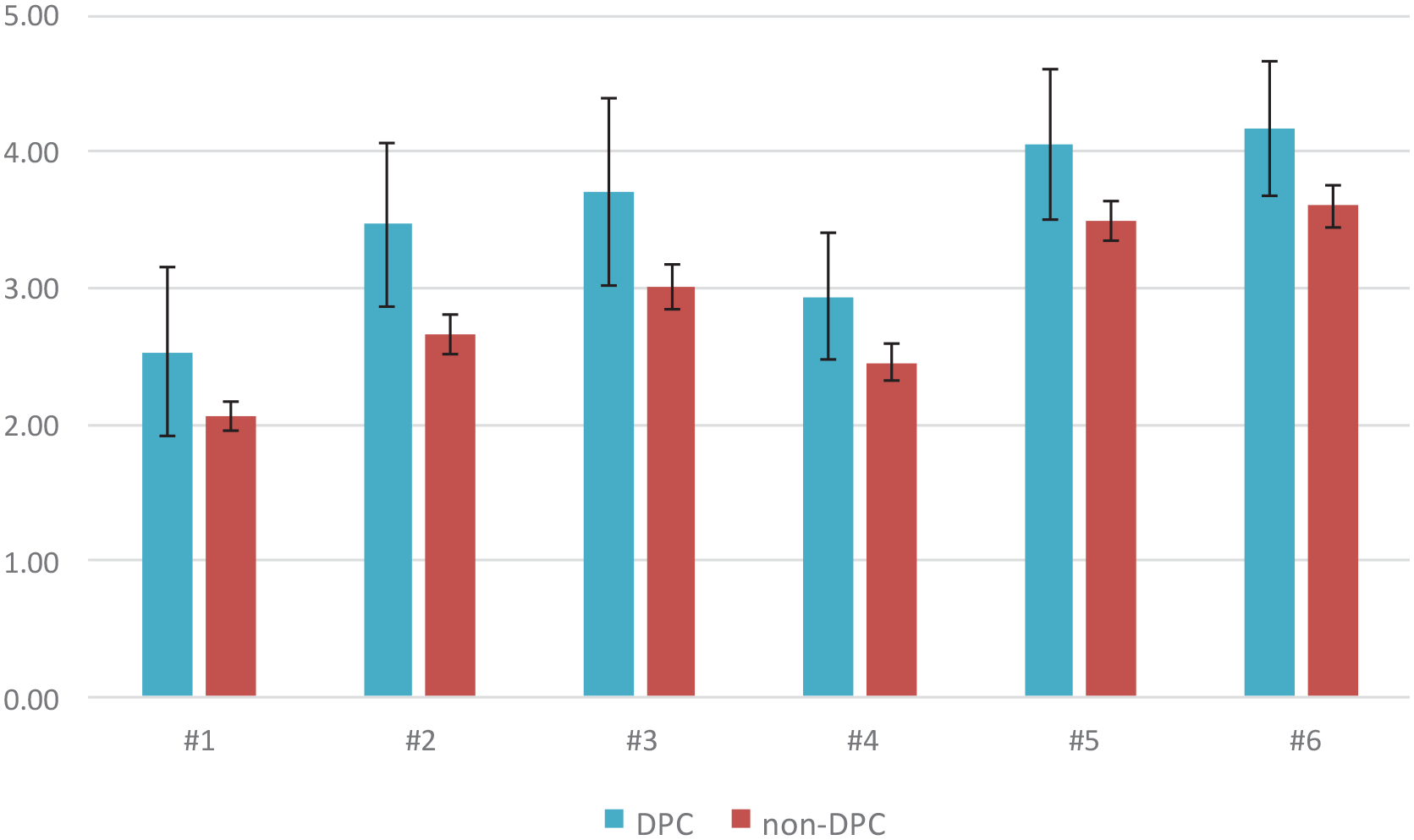

Second, we used an AAFP-endorsed definition to assess knowledge and beliefs about the DPC model. AAFP defines DPC as a model in which physicians do not accept payments from insurance companies or other third-party payers, but rather, patients pay a monthly membership fee ranging from $50 to $150 for a defined set of primary care services for no extra charge, and low-cost prescriptions and other services13. Survey respondents were asked to indicate their agreement on a Likert-type scale with each of several statements about the model: Statement #1 – patient confusion; Statement #2 – not financially sustainable; Statement #3 – increases physician shortage; Statement #4 – only benefits healthy and wealthy; Statement #5 – lack of health improvement; Statement #6 – low quality. Statements were worded negatively with agreement indicating negative perceptions of DPC. See Figure 1 for complete text of the statements.

Figure 1. Level of agreement with statements about direct primary care by practice model.

Likert values: 1 = Strongly Agree, 2 = Agree, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Disagree, 5 = Strongly Disagree. Statement #1: In a DPC model, patients may not understand that they still need insurance to cover services that the DPC physician does not provide, such as specialists and hospitalizations (p=0.213). Statement #2: Financial sustainability for DPC physicians is not assured (p=0.056). Statement #3: The fact that DPC patient panels are smaller will worsen the primary care physician shortage (p=0.013). Statement #4: The DPC model only benefits healthy and wealthy patients (p=0.038). Statement #5: Unlimited access to primary care through a DPC model is not likely to lead to improved health outcomes for patients (p=0.028). Statement #6: Lack of control over how DPC physicians practise and what treatments they suggest is likely to result in low quality such as over-treatment or under-treatment (p=0.039). Statistical significance at the 5% level determined by the Mann-Whitney U test. Error bars indicate 95% confidence interval.

Next, respondents were asked to rank the top three benefits of the model, selecting from a list of five choices. Respondents could select ‘Other’ and enter a written response. The topics included administrative burden, time with patients, spending on downstream care, and physician responsiveness to patient needs and preferences.

Results were summarized and compared by practice model (DPC or not), using the Mann-Whitney U test. Complete case analysis was performed. Fifteen surveys with missing data on either the outcome or the belief statements were excluded.

RESULTS

There were 225 complete responses to this survey for a response rate of 33%. Respondents were similar to AAFP membership by sex, years since completed residency, and practice ownership model. Table 1 represents distributions of survey respondents, MIE members, and AAFP members, however, variables of interest to this study are not available in the broader data.

Table 1.

Characteristics of survey respondents, member insight exchange and AAFP active members (2017 AAFP data)

| Characteristics | AAFP | Member insight exchange | Survey respondents |

|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 58 | 50 | 55 |

| Female | 42 | 50 | 45 |

| Years since completed residency | |||

| ≤7 | 25 | 32 | 21 |

| 8–14 | 22 | 23 | 22 |

| 15–21 | 21 | 27 | 21 |

| ≥22 | 32 | 19 | 37 |

| Ownership model | |||

| Sole owner | 13 | 13 | 11 |

| Partial owner | 17 | 14 | 12 |

| 100% employed | 66 | 69 | 74 |

| Not applicable/not in clinical practice | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Member count | 68300 | 672 | 225 |

No variables are significantly different between AAFP members and survey respondents.

Most respondents (85%) were familiar with DPC, with 8% of the sample reporting practising in a DPC model; a majority (79%) selected the AAFP-endorsed definition of DPC, 13% responded ‘Don’t know’ and 8% selected a definition that aligns with PCMH rather than DPC.

Respondents indicated agreement with statements that DPC has benefits for patients. For example, a minority expressed concern about quality in DPC, with 29 (13%) perceiving that DPC practice will result in quality problems such as over-treatment and under-treatment. Similarly, 43 (19%) perceived that DPC patients will not experience improved health outcomes. There was, however, concern about the applicability of DPC to all patients. While the survey did not directly address low-income or vulnerable patients, two respondents expressed this concern in the open-ended responses. One physician stated: ‘This model may leave undue burden on patients and it risks losing the primary care safety net for the very poor and underserved’.

For all statements included in Figure 1, agreement was greater among non-DPC than DPC family physicians. For four of the six belief statements, the difference in responses by the physician’s current practice model was statistically significant. Compared to non-DPC physicians, DPC physicians were less concerned about the primary care physician shortage (p=0.013), less concerned about the potential for over-treatment and under-treatment in DPC (p=0.039), more certain that DPC benefits more than just healthy and wealthy patients (p=0.038), and more certain that DPC will lead to improved patient health outcomes (p=0.028).

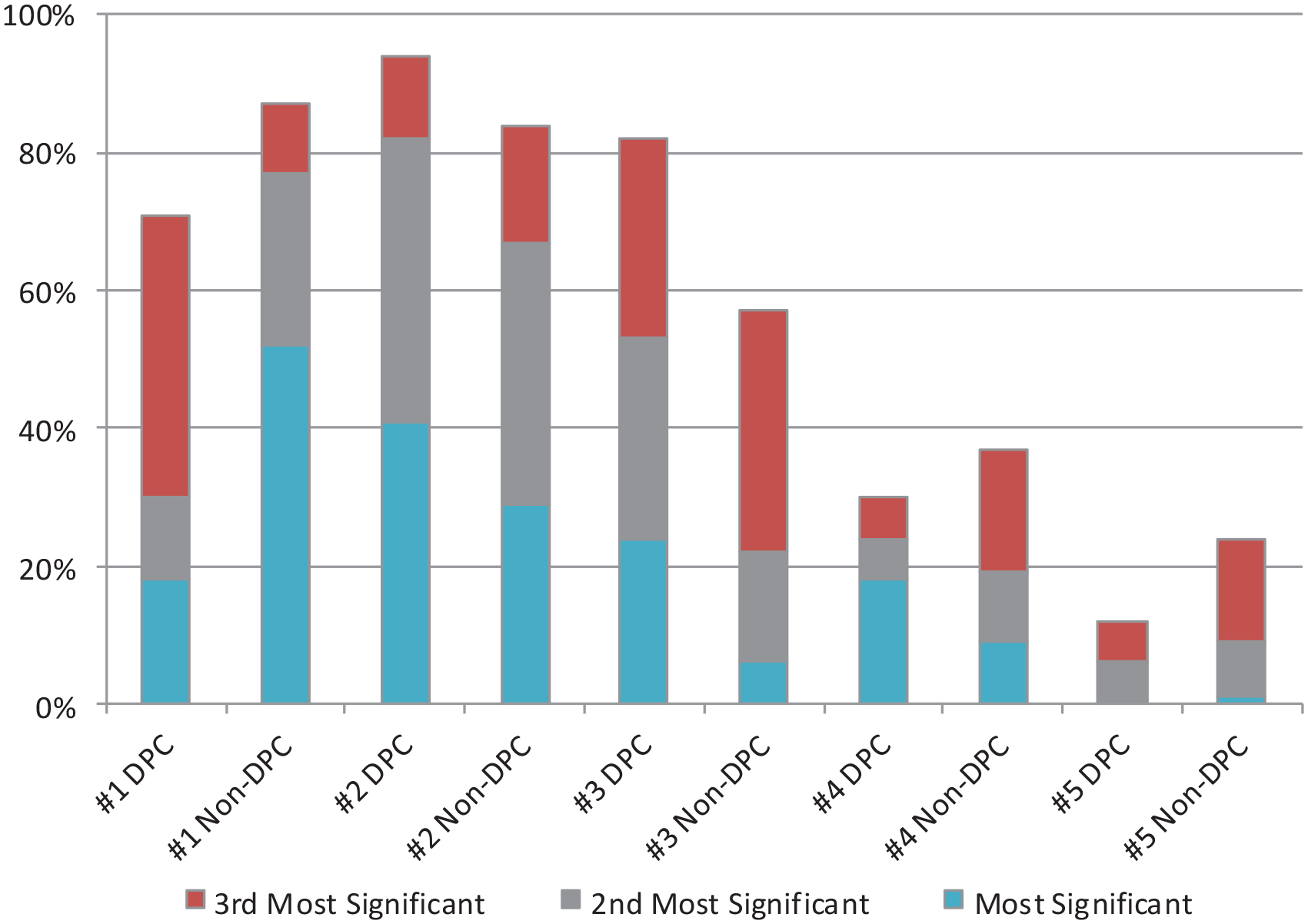

Figure 2 presents the respondent rankings of the top-three most important benefits of DPC. Overall, respondents ranked the most important benefits about DPC as: 1) lower administrative burden, 2) improved patient health outcomes, and 3) lower healthcare expenditures. Forty-eight percent of respondents selected lower administrative burden as the most important benefit and 84% selected it as one of the top-three benefits of DPC.

Figure 2. Ranking of DPC benefits by practice model.

Benefit #1: Removing the administrative burden of insurance paperwork and pre-approvals will improve physician satisfaction and reduce practice overhead, as fewer administrative employees will be needed (p=0.001). Benefit #2: Smaller patient panels will enable the physician to spend more time with each patient improving the doctor-patient relationship, educating the patient, and getting to the root of problems (p=0.197). Benefit #3: Smaller patient panels enable the physician to be available to patients when and how it is convenient for them. This promotes the use of primary care and is likely to catch problems before they become more serious and prevent over-use of urgent care, emergency departments, specialists, and hospital services (p=0.008). Benefit #4: By removing primary care from the insurance system (which will lower insurance premiums) and improving the health of patients, DPC is likely to move us towards the Quadruple Aim of enhancing patient experience, improving population health, reducing healthcare spending, and improving the work life of healthcare providers (p=0.816). Benefit #5: Since the physician works directly for the patient, they must be responsive to patient needs and preferences as patients are free to end their DPC membership at any time (p=0.391). Statistical significance at the 5% level determined by the Mann-Whitney U test.

Increased time with patients to improve the doctor–patient relationship and to educate the patient and get to the root of problems was selected by 68 respondents (30%) as the most important benefit and by 189 (84%) as one of the top-three benefits of DPC. Better availability of care, which prevents overuse of downstream services, was only selected as the most important benefit by 18 respondents (8%), while 133 (59%) selected it as one of the top benefits.

Rankings were statistically significant by practice model. Lower administrative burden was selected as the most important benefit by half (51%) of non-DPC physicians, but only 18% of DPC physicians (p=0.001). Nearly 25% of DPC physicians selected better availability of care as the most important benefit of DPC; 6% of non-DPC physicians made the same selection (p=0.008). The three other benefits were not significantly different by practice model.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to compare familiarity and perceived benefits of a DPC model by DPC and non-DPC family practitioners to understand the potential for physician satisfaction and future model adoption. This is the first survey to our knowledge that assessed family physicians’ views about Direct Primary Care informed by whether they practised in the model. Several commentaries and opinion pieces have been published on DPC29–31 but no studies have distinguished between perspectives held by those practising and those not practising in a DPC model. In previous work, DPC either was not included in physician surveys, or was reported only in combination with other alternative payment models, which obscured model-specific physician views of DPC32. The variation in perspectives may be relevant to how broadly suitable DPC is for various physicians and patient populations, and thus its growth potential and its applicability in various settings24,28. By highlighting these differences, we aimed to understand the extent to which DPC models are understood and its perceived benefits to physicians and patients. Overall, we found that family medicine physicians who responded to this survey share a relatively high level of familiarity with DPC, with 85% of respondents having heard of the model and 79% correctly identifying the overall goal of the model. Beginning with this highly knowledgeable group, we demonstrated fairly consistent perceptions of the benefits but with a few key distinctions by whether or not they practised in a DPC model.

First, we found that family physicians broadly agreed that DPC has the potential to improve patient health outcomes. More time with patients, improving the doctor–patient relationship and getting to the root of problems were tied as the most significant benefit of the model, while the statement that patient health outcomes would not improve in DPC received high disagreement. This finding supports studies that show a positive association between improved doctor–patient relationships and improved patient health outcomes16,17,19.

Second, we found that family physicians generally agreed that administrative burden is less in a DPC model, which could improve physician satisfaction. Improved physician satisfaction due to lower administrative burden and less paperwork was tied as the most significant benefit of the model. This finding supports other studies that have linked physician burnout and dissatisfaction to high levels of administrative burden7–12.

Third, family medicine physicians reported that DPC is beneficial for both patients and physicians; this, along with limited concerns about physician shortages and access for vulnerable patients, may suggest potential success of bottom-up physician-driven models more generally. In particular, respondents did not perceive that patient outcomes or quality would likely suffer without the additional documentation and reporting tasks that are required by typical top-down centralized healthcare delivery reform initiatives. Respondents expressed high disagreement to the statement that DPC will result in low quality such as over-treatment or under-treatment. As such, meaningful performance measurement is difficult in primary care due to its complexity and uncertainty. More than a third of health concerns initially encountered in primary care do not lead to a diagnosis, and about half are unlikely to result in a definite diagnosis that would trigger a standard care pathway33. Complex interactions and interdependencies emerge in primary care due to the unique clinical concerns, decisions, and personal circumstances34. Typical performance measures often fail to address the breadth and depth of comprehensive primary care delivery; simply measuring individual elements of care is an inadequate reflection of the value of primary care35.

Finally, this study adds to the literature by showing significant variation in the perspectives of family medicine physicians who practise in an insurance-based model and those who practise in a DPC model. DPC physicians are likely to be highly select in this sample, with both experience and perceptions of the model. DPC physicians expressed more disagreement with all of the statements, and the differences were statistically significant for four of the six statements. As all statements were negatively worded, this suggests that DPC physicians were more confident and supportive of the DPC model than their non-DPC colleagues. In addition, the finding that DPC physicians were much less focused on the perceived benefit of reduced administrative burden than the non-DPC family physicians may indicate that administrative burden is less a part of their day-to-day practice of medicine than it is for non-DPC physicians.

Limitations

The study has several limitations. Namely, the survey respondents are likely to be a highly select group. While we found very similar demographic profiles to the overall membership, the results may not be generalizable to all family physicians or to the AAFP membership. AAFP’s Member Insight Exchange is a marketing platform in which respondents self-select to receive surveys and may choose to answer or ignore any survey provided; these results are likely not representative of overall family physicians’ views of DPC. Physicians who are familiar with DPC or who have a strong opinion about DPC may have been more likely to respond to the survey than physicians who are unfamiliar with the model or who have not yet formed an opinion. For example, these results differ from results of AAFP’s 2017 Practice Profile Survey, which showed that one-third of family physicians (33%) were unfamiliar with the DPC model, a small portion (3%) practised in a DPC model, and a small portion (1%) were in the process of transitioning their practice to a DPC model28. Given the limited scope of this survey and that it was available to a small subset of AAFP members, further research is needed to gauge family physician views of DPC more broadly and to improve the generalizability of these findings and to determine how perceptions have changed over time. However, this study offers insights beyond generalizability.

First, it allows us to understand perceptions from a group that both understands the model and has ostensibly strong feelings (both positive and negative) about the model. While the study is not comprehensive, these respondents are potentially the individuals more likely to propose or resist a move to a DPC model.

Second, this study was focused on the primary perceived benefits of a DPC model. Clearly, there are also strong challenges associated with this model that need to be addressed in future studies. Additionally, our list of benefits was not comprehensive, but rather, was consistent with previous literature’s suggested benefits3,16,18. By focusing on these perceptions, we determined what areas and topics are agreed to by both DPC and non-DPC physicians.

This study revealed variation in perspectives about DPC between family physicians who practise in a DPC model and those who do not. While the survey does not allow us to determine why perspectives differ by practice model, there are several possible explanations. Non-DPC physicians may have limited familiarity with how DPC works in practice, and their lack of familiarity may cause them to be cautious about the model’s benefits. Conversely, DPC physicians and particularly those who responded to the survey were more likely to advocate the benefits of the model. Both perspectives should be approached with caution. Also, it is possible that the patient panels of non-DPC physicians are different from those of DPC physicians in ways that would affect the perceived success of the model for those physicians. Observed differences in responses may only reflect differences in perceptions and may not be indicative of how care is objectively delivered in a DPC model compared to a traditional delivery model. It is also possible that variations in physician perspectives by model reflect real differences in patient outcomes and physician satisfaction due to the model. Additional studies are needed to test these hypotheses.

CONCLUSIONS

This research suggests that any consideration of a change towards a new practice model will require both additional empirical evidence and physician education. Even while the AAFP continues to educate on DPC, nearly 20% of the sampled members remained unclear of the specifics of the model. Additional research should consider if understanding has improved in the past few years, especially among a more general population of physicians. While the demonstrated benefits of a DPC model require more empirical evidence, the lack of consistent perceptions across family physicians may present a challenge for managers who are exploring alternatives or seeking physician buy-in to new practice models.

Any movement towards a DPC approach will require additional outreach to practice-partners to explicitly identify how DPC models will not marginalize patients. Any further education will require a clear distinction from ‘concierge medicine’ and to clarify how the model addresses physician caseloads. Respondents highlighted key potential shortcomings of the DPC approach, namely identifying physician shortages and access for vulnerable patients. Yet, respondents remained flexible and open to the benefits of DPC especially related to patient concerns. In general, results indicated that a select group of DPC-educated family physicians perceived the potential to offer better working conditions, more time with patients, deeper doctor–patient relationships, and ultimately higher quality of treatment.

Non-DPC physicians appear to be more skeptical of the DPC approach. In part, this may be due to less information or because DPC physicians are more likely to confirm their choices and biases. Nonetheless, any attempts to transition practices will require education of non-DPC physicians about specific benefits to both patients and physicians. DPC physicians appear to be strong potential advocates for quality of care in the DPC model. Compared to non-DPC physicians, views of family physicians practising in a DPC model were found to differ in several areas. DPC physicians exhibited higher disagreement with statements that DPC only benefits the healthy and wealthy, it will worsen the PCP shortage, it will not lead to improved patient health outcomes, and quality will be poor. Additionally, DPC physicians focused more on perceived benefit to patients (enhanced access to primary care, resulting in improved patient health outcomes) while non-DPC physicians focused more on perceived benefits to physicians (less administrative burden and insurance paperwork, improved physician satisfaction).

These results are important initial findings about the perceptions of DPC as it continues to grow as a model of primary care delivery20,21. Future research will better determine whether DPC delivers the kinds of benefits that are integral to address access, cost and workforce-related problems facing primary care and family medicine today. While more research is required to empirically determine whether DPC is a successful model, our results highlight the potential obstacles of physician understandings, particularly by current practice experiences, in openness to new practice models. Different perspectives by practice model indicate a need for a more comprehensive and cohesive understanding of the potential benefits and shortcoming of various alternative practice approaches for family physicians. Additionally, practice decision-makers will need to recognize the sensitivities and biases associated with various physician perceptions and understandings of practice models. Taken together, primary care practice and delivery can likely benefit from broader knowledge of practice approaches among physicians to face ongoing and considerable healthcare challenges36.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This survey was made possible with assistance from the American Academy of Family Physicians National Research Network.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have each completed and submitted an ICMJE form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. The authors declare that they have no competing interests, financial or otherwise, related to the current work. G. Brekke reports payment and support for speaking at a conference in June 2021. K. Kimminau reports that she was a part-time contracted employee at the American Academy of Family Physicians, and was employed by University of Kansas Medical Center during the conduct of this study. She is completing review and other authorship requirements from her present position at the University of Missouri-Columbia, and reports grants from the University of Kansas Medical Center (NCATS Frontiers Clinical and Translational Science Award, PCORnet Greater Plains Collaborative, NCI Cancer Center and COE supplement awards) during the study. She also reports being a consultant to the Sunflower Foundation, and a secretary for the nonprofit RareKC Inc. S. Ellis reports grants as an early stage investigator award from the Kansas Institute of Precision Medicine (COBRE grant P20GM130423). J. Saint Onge has nothing to disclose.

FUNDING

There was no source of funding for this research.

Footnotes

ETHICAL APPROVAL AND INFORMED CONSENT

The Institutional Review Board of the University of Kansas Medical Center determined the study is exempt from human subject protection review. Participants were self-selected through their participation.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data supporting this research cannot be made available for privacy reasons.

REFERENCES

- 1.Phillips RL, Pugno PA, Saultz JW, et al. Health is primary: Family medicine for America’s health. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(Suppl 1):S1–S12. doi: 10.1370/afm.1699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American College of Physicians. The Impending Collapse of Primary Care Medicine and Its Implications for the State of the Nation’s Health Care: A Report from the American College of Physicians. American College of Physicians; 2006. Updated October 13, 2016. Accessed June 24, 2021. https://www.acponline.org/acp_policy/statements/impending_collapse_of_primary_care_medicine_and_its_implications_for_the_state_of_the_nations_health_care_2006.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macinko J, Starfield B, Shi L. The Contribution of Primary Care Systems to Health Outcomes within Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Countries, 1970–1998. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(3):831–865. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission; 2018. Accessed June 24, 2021. http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar18_medpac_entirereport_sec.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 5.California Health Care Foundation. Overuse of Emergency Departments Among Insured Californians. California Health Care Foundation; 2006. Accessed June 24, 2021. https://www.chcf.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/PDF-EDOveruse.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berry-Millett R, Bandara S, Bodenheimer T. The health care problem no one’s talking about. J Fam Pract. 2009;58(12):633–637. Accessed June 24, 2021. https://cdn.mdedge.com/files/s3fs-public/Document/September-2017/5812JFP_Article1.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the Patient Requires Care of the Provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573–576. doi: 10.1370/afm.1713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arndt BG, Beasley JW, Watkinson MD, et al. Tethered to the EHR: Primary Care Physician Workload Assessment Using EHR Event Log Data and Time-Motion Observations. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(5):419–426. doi: 10.1370/afm.2121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holman GT, Waldren SE, Beasley JW, et al. Meaningful use’s benefits and burdens for US family physicians. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018;25(6):694–701. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocx158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU. Administrative Work Consumes One-Sixth of U.S. Physicians’ Working Hours and Lowers their Career Satisfaction. Int J Health Serv. 2014;44(4):635–642. doi: 10.2190/HS.44.4.a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of Physician Time in Ambulatory Practice: A Time and Motion Study in 4 Specialties. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(11):753–760. doi: 10.7326/M16-0961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gray BH, Stockley K, Zuckerman S. American Primary Care Physicians’ Decisions to Leave Their Practice: Evidence From the 2009 Commonwealth Fund Survey of Primary Care Doctors. J Prim Care Community Health. 2012;3(3):187–194. doi: 10.1177/2150131911425392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Academy of Family Physicians. Direct Primary Care: An Alternative Practice Model to the Fee-For-Service Framework. American Academy of Family Physicians; 2014. Accessed June 24, 2021. https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/practice_management/payment/DirectPrimaryCare.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alexander GC, Kurlander J, Wynia MK. Physicians in Retainer (“Concierge”) Practice. A National Survey of Physician, Patient, and Practice Characteristics. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(12):1079–1083. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0233.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rowe K, Rowe W, Umbehr J, Dong F, Ablah E. Direct Primary Care in 2015: A Survey with Selected Comparisons to 2005 Survey Data. Kans J Med. 2017;10(1):3–6. doi: 10.17161/kjm.v10i1.8640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mollborn S, Stepanikova I, Cook KS. Delayed care and unmet needs among health care system users: when does fiduciary trust in a physician matter? Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6p1):1898–1917. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00457.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall MA, Dugan E, Zheng B, Mishra AK. Trust in physicians and medical institutions: what is it, can it be measured, and does it matter? Milbank Q. 2001;79(4):613–639. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colwill JM, Frey JJ, Baird MA, Kirk JW, Rosser WW. Patient Relationships and the Personal Physician in Tomorrow’s Health System: A Perspective from the Keystone IV Conference. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(Suppl 1):S54–S59. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2016.S1.160017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thom DH, Hall MA, Pawlson LG. Measuring Patients’ Trust In Physicians When Assessing Quality Of Care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;23(4):124–132. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.4.124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DPC Frontier Mapper. DPC Frontier. Accessed June 21, 2021. https://mapper.dpcfrontier.com/

- 21.Lacey P Per Capita DPC Enrollment. Hint Health blog. Accessed June 21, 2021. https://blog.hint.com/per-capita-dpc-enrollment

- 22.Howrey BT, Thompson BL, Borkan J, et al. Partnering With Patients, Families, and Communities. Fam Med. 2015;47(8):604–611. Accessed June 24, 2021. https://fammedarchives.blob.core.windows.net/imagesandpdfs/pdfs/FamilyMedicineVol47Issue8Howrey604.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stange KC. Holding On and Letting Go: A Perspective from the Keystone IV Conference. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(Suppl 1):S32–S39. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2016.S1.150406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puffer JC, Borkan J, DeVoe JE, et al. Envisioning a New Health Care System for America. Fam Med. 2015;47(8):598603. Accessed June 24, 2021. https://fammedarchives.blob.core.windows.net/imagesandpdfs/pdfs/FamilyMedicineVol47Issue8Puffer598.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klemes A, Seligmann RE, Allen L, Kubica MA, Warth K, Kaminetsky B. Personalized preventive care leads to significant reductions in hospital utilization. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(12):e453–e460. Accessed June 24, 2021. https://cdn.sanity.io/files/0vv8moc6/ajmc/c2379ef2c7c2e30c968f0d7a74130a781a4194e2.pdf/AJMC_12dec_Klemes_e453to460.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bujold E The Impending Death of the Patient-Centered Medical Home. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(11):1559–1560. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.4651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wergin R Your Opinion Matters; Here’s How to Share It. American Academy of Family Physicians. May 5, 2015. Accessed June 24, 2021. https://www.aafp.org/news/blogs/leadervoices/entry/your_opinion_matters_here_s.html [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Academy of Family Physicians. AAFP 2017 Practice Profile Survey. American Academy of Family Physicians; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rubin R Is Direct Primary Care a Game Changer? JAMA. 2018;319(20):2064–2066. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.3173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weisbart ES. Is Direct Primary Care the Solution to Our Health Care Crisis? Fam Pract Manag. 2016;23(5):10–11. Accessed June 24, 2021. https://www.aafp.org/fpm/2016/0900/fpm20160900p10.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eskew P In Defense of Direct Primary Care. Fam Pract Manag. 2016;23(5):12–14. Accessed June 24, 2021. https://www.aafp.org/fpm/2016/0900/fpm20160900p12.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.The Physicians Foundation. 2016 Survey of America’s Physicians: Practice Patterns and Perspectives. The Physicians Foundation; 2016. Accessed June 24, 2021. https://physiciansfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Biennial_Physician_Survey_2016.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosendal M, Carlsen AH, Rask MT, Moth G. Symptoms as the main problem in primary care: A cross-sectional study of frequency and characteristics. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2015;33(2):91–99. doi: 10.3109/02813432.2015.1030166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rich E, O’Malley A. Measuring What Matters in Primary Care. Health Affairs Blog. October 6, 2015. Accessed June 24, 2021. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20151006.051032/full/

- 35.Young RA, Roberts RG, Holden RJ. The Challenges of Measuring, Improving, and Reporting Quality in Primary Care. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(2):175–182. doi: 10.1370/afm.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brekke G, Saint Onge JM, Kimminau KS, Ellis S. Direct Primary Care: Family Physician Perceptions of a Growing Model. medRxiv. Preprint posted online March 26, 2021. doi: 10.1101/2021.03.22.21254097 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this research cannot be made available for privacy reasons.