Abstract

Natural food preservatives in the form of herb extracts and spices are increasing in popularity due to their potential to replace synthetic compounds traditionally used as food preservatives. Rosemary (Salvia rosmarinus) is an herb that has been traditionally used as an anti-inflammatory and analgesic agent, and currently is being studied for anti-cancer and hepatoprotective properties. Rosemary also has been reported to be an effective food preservative due to its high anti-oxidant and anti-microbial activities. These properties allow rosemary prevent microbial growth while decreasing food spoilage through oxidation. Rosemary contains several classes of compounds, including diterpenes, polyphenols, and flavonoids, which can differ between extracts depending on the extraction method. In particular, the diterpenes carnosol and carnosic acid are two of the most abundant phytochemicals found in rosemary, and these compounds contribute up to 90% of the anti-oxidant potential of the herb. Additionally, several in vivo studies have shown that rosemary administration has a positive impact on gastrointestinal (GI) health through decreased oxidative stress and inflammation in the GI tract. The objective of this review is to highlight the food preservative potential of rosemary and detail several studies that investigate rosemary to improve in vivo GI health.

Keywords: Food preservative, Rosemary, phytochemical, anti-oxidant, anti-microbial, gastrointestinal health

Introduction

Rosemary (Salvia rosmarinus; formerly referred as Rosmarinus officinalis Linn) is an aromatic plant native to the Mediterranean region known to be rich in a variety of phytochemicals with anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. This perennial plant possesses a shrub shape reaching up to two meters high with a characteristic fragrance with uses including a spice for cooking, a medicinal plant, and a food preservative.[1] The health promoting properties of rosemary include hepatoprotective properties, therapeutic potential for Alzheimer’s, and anti-cancer properties.[2-5] Spain, and more specifically, the province of Murcia (Southeast Spain), is a major processor and importer of rosemary, and the development of the commercial market has allowed for the use of rosemary to expand to the rest of Europe and the United States.[6]

The development of rosemary extract (RE) can generate a variety of unique formulations rich in compounds including rosmarinic acid (RA), carnosol (CL), and carnosic acid (CA). As with any other extract, the solvent and extraction method that is used will determine the resulting phytochemical composition, thereby impacting the physical and chemical properties of the extract. In the case of rosemary, a water soluble extract, which is typically rich in RA, will be effective in a water or polar matrix, while an oil soluble extract rich in diterpenes will be of value in an non-polar matrix such as a lipid formulation.[7] Due to the variability in phytochemical composition that occurs from each extraction, the characterization of the phytochemical content of different extracts and essential oils is critical to report.

A more recent application of RE has been food preservation due to the ability to prevent oxidation and microbial contamination.[8-10] This rationale has provided a consumer and industry interest in replacing or decreasing synthetic antioxidants in foods. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has reviewed the safety of RE for use as food additives, and the panel found that the No Observable Adverse Effects Level (NOAEL) of rosemary extracts in 90-day rat studies was 180-400 mg RE/kg/day, which equates to 20-60 mg/kg/day of CL plus CA. [11] These values translate to mean intake estimates of 500-1500 mg/kg/day of CL and CA in human adults. The panel concluded through several toxicology studies that these margins do not pose any safety risks in humans. As a result, RE can be added to food and beverages at levels of up to 400 mg/kg (as the sum of CA and CL) in the European Union.

Due to the growing interest on the medicinal properties of Salvia rosmarinus, our objective is to present the role of RE as a food preservative with beneficial properties for gastrointestinal health. Therefore, this manuscript builds a literature gathering on rosemary to identify main bioactive compounds, extracts and essential oils and to characterize their application. The anti-oxidant and anti-microbial properties of various REs are described along with specific food preservation studies. Finally, in vivo studies that show the impact of REs on GI health are outlined with significant findings. The goal of this review is to highlight the potential of REs to be used as natural food preservatives and to provide the benefit of improved GI health.

Phytochemicals

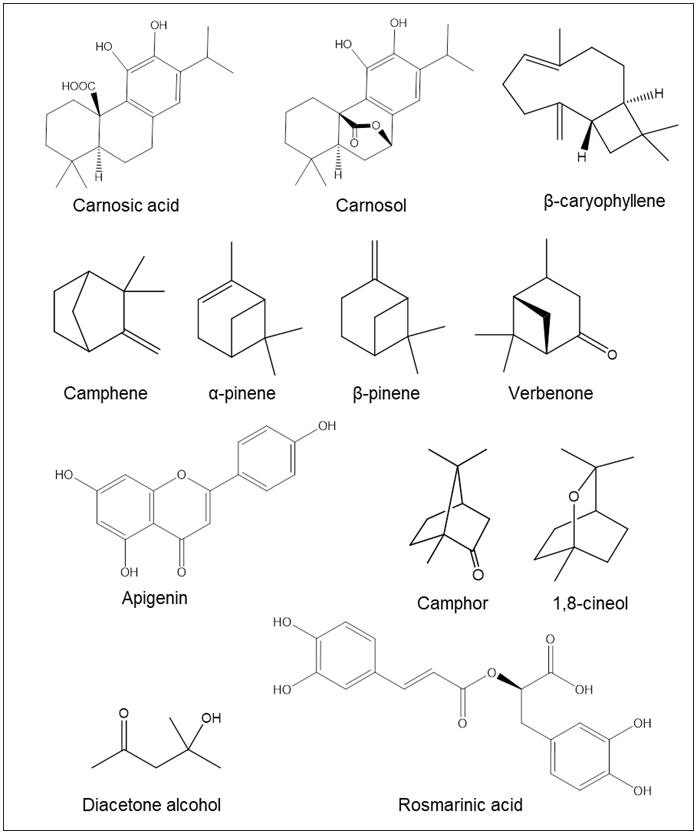

The phytochemical content of RE can differ based on the method of extraction. Among the classes of compounds that RE contains include flavonoids, polyphenols, terpenoids, and volatile oils [12-14]. Table III details the phytochemical content in rosemary and reports the most abundant phytochemicals found therein, and Figure 2 shows the structures of phytochemicals commonly associated with rosemary.

The most studied and characterized phytochemicals in RE are CL, CA, and RA [15-17]. The diterpenes CL and CA have been extensively studied for their anti-oxidant, anti-microbial, and anti-proliferative activities [11]. In extracts, CL and CA are primarily found in oil-soluble (e.g. ethanol, methanol) RE fractions, and RA is the predominant phytochemical in the water-soluble (aqueous) RE fraction [1]. Other phytochemicals that have been identified in RE are caffeic acid, luteolin, apigenin, camphor, and borneol. The total number of individual components in RE depends on the type of extraction and the source of the plant [1]. For example, Cattaneo et al. identified 12 different compounds in a hydroalcoholic extract of Salvia rosmarinus by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), and Mena et al. identified 57 separate components by ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization (UHPLC-ESI)-MSn [1]. Hydrodistillation of the rosemary leaves results in the REO, which contains primarily monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes and possesses anti-microbial and analgesic properties [11]. The major individual components found in REO are 1,8-cineol, α-pinene, and camphor [11].

Applications of rosemary as a food preservative

Anti-oxidant activity

The anti-oxidant properties of RE has been well established with a high degree of the anti-oxidant activity attributed to the phenolic compounds that rosemary possesses. Alizadeh et al. evaluated the anti-oxidant capacity of RE (24-26% total phenolic diterpenes, >16% CA) at 0.1%, 1.0%, and 10% (w/v) in methanol [18]. The study found that RE scavenged free radicals in a concentration dependent manner, with 10% RE reducing 99% of free radical by the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) free radical-scavenging assay. The authors attributed the high anti-oxidant activity to the phenolic diterpenes contained in the extract. Nie et al. evaluated an ethanolic RE for anti-oxidant activity [18]. The study identified 12 compounds from the extract, and each were tested against DPPH and OH free radicals. The main source of anti-oxidant activity in the RE was RA, achieving free radical scavenging rates of >80% for both assays. The extract was also tested by 2',7'-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA) assay in vitro using HeLa cells and was shown to greatly reduce the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by H2O2.

The REO, which contains more volatile phytochemicals than an extract, also possesses anti-oxidant activity. Rašković et al. determined the anti-oxidant capability of REO through the DPPH radical-scavenging assay and measured the total phenolic content (TPC) of the oil [11]. Determining the TPC can be an indicator of the degree of anti-oxidant capacity of a sample because phenols are typically highly anti-oxidant. Sample analysis by GC-MS showed that REO contained mostly oxygenated monoterpenes (63.88%) and monoterpene hydrocarbons (31.22%), with the most abundant individual phytochemicals being 1,8-cineole (43.77%), camphor (12.53%), and α-pinene (11.51%). Analysis with DPPH assay revealed the IC50 (50% DPPH radical scavenged) to 77.6 μL/mL compared to 23.5 μg/mL by α-tocopherol. The TPC of REO was 153.35 mg GAE/L, suggesting that the abundance other compounds such as oxygenated monoterpenes also contributed to the high anti-oxidant activity. Bozin et al. also measured the anti-oxidant activity of REO (46.9% oxygenated monoterpenes, 46.7% monoterpene hydrocarbons) using DPPH and thiobarbituric acid reactive substance (TBARS) assays [11]. The TBARS assay measures the formation of lipid peroxidation, which can be inhibited by anti-oxidant compounds. The IC50 of REO in the DPPH assay was 3.82 μL/mL, which was lower than the positive control butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) (5.67 μL/mL). Two peroxide-generating systems were used for the TBARS assay, Fe2+/ascorbate and Fe2+/H2O2. In the Fe2+/ascorbate system, REO at 10% inhibited 75.79% of peroxide formation, compared to 37.04% with BHT. In the Fe2+/ H2O2 system, REO at 10% only inhibited 58.33% of peroxide formation, while BHT inhibited 66.67% of peroxide formation. The discrepancy between the two systems may result from REO possessing a mode of action that favors inhibition of peroxides generated by the Fe2+/ascorbate system over the Fe2+/H2O2.

Anti-microbial activity

Rosemary has been extensively studied for its anti-microbial activity against both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. Oliveira et al. investigated the anti-microbial activity of RE (200 mg/mL in propylene glycol) against C. albicans, S. aureus, E. faecalis, S. mutans, and P. aeruginosa in planktonic cultures and against biofilm formation [18]. RE showed the strongest activity against C. albicans with a MIC and a minimum microbicidal concentration (MMC) of 0.78 mg/mL and 3.13 mg/mL, respectively. Additionally, RE showed strong activity against P. aeruginosa with both an MIC and MMC of 6.25 mg/mL. S. aureus, S. mutans, and E. faecalis growths were inhibited at >25 mg/mL, but a microbicidal concentration was not reached. The study also revealed that RE was effective against biofilm formation of C. albicans, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, and S. mutans. In poly-microbial films, C. albicans was cultured with the other four bacteria for 48 hours in this study and treated with 200 mg/mL RE for 5 minutes. The most significant reduction in microbial growth with RE occurred in C. albicans plus E. faecalis and C. albicans plus P. aeruginosa (P ≤ 0.0001).

Methanol and ethanol RE were also evaluated against eight different bacterial strains grown on agar, including E. coli, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, B. cereus, E. faecalis, C. albicans, V. fluvialis, and V. damsel [1]. The methanol extract showed a higher degree of inhibition against bacterial growth compared to the ethanol extract. The authors noted that the presence of CA in the methanol extract was likely the reason for the increased anti-microbial activity. In fact, several studies have associated the concentration of CA in RE with its effectiveness against microbial growth [19-21].

In a separate study, REO was evaluated against 60 clinical samples of multi-drug resistant E. coli [22]. The chemical composition of REO was determined by GC-MS, and the major phytochemicals were 1,8-cineole (46.4%), camphor (11.4%), and α-pinene (11.0%). The MIC of REO against the clinical samples ranged from 18.0 to 20.0 μL/mL, although these values were less effective than basil essential oil tested in the same study (8.0 to 11.5 μL/mL). Jardak et al. also evaluated the anti-microbial effects of REO against S. aureus and S. epidermidis by microdilution method [7]. The REO had a greater effect against S. epidermidis with an MIC of 0.312-0.625 μL/mL and MMC of 2.5 μL/mL versus an MIC and MMC of 1.25-2.5 μL/mL and 5 μL/mL, respectively, for S. aureus.

Food preservation:

Rosemary has been studied extensively for a variety of biological properties including anti-oxidant and anti-microbial activities [23]. These properties make rosemary of particular interest as a natural food preservative2 [24]. The EU approved RE as a food preservative after extensive toxicity studies and determining that the o observed adverse effect level (NOAEL) range was wide enough to not pose any safety concerns [1]. Published reports have suggested that up to 90% of the anti-oxidant capacity of RE can be attributed to the CL and CA content [18, 22]. Therefore, RE used in food preservation is most often defined by the CL and CA content to ensure consistent potency and safety. Additionally, the significant anti-microbial activity of RE and REO further enables food preservation through inhibition of bacterial or mold growth on food products [11].

Several food matrix models have also been used to evaluate the ability of RE and REO as a food preservative. In fattening lambs with diets supplemented with RE through the animal feed, packaged meat showed a greater degree of protection from oxidation and microbial growth with RE supplementation [7]. Additionally, shelf life and sensory qualities such as odor and color were improved in lamb given RE, and these factors were improved with higher CL intake [18]. Addition of RE to pork patties packaged in modified-atmosphere packaging (MAP) protected against protein and lipid oxidation greater than BHT, a common synthetic preservative [18]. Addition of REO at 0.2% in combination with MAP had a positive effect in sensory qualities and decreased lipid oxidation in poultry fillets, although no significant effects on microbial growth were detected [11]. Addition of RE at 2.0% (v/v) to edible gelatin coating significantly inhibited growth of Listeria monocytogenes inoculated on raw beef for 48 hours [1]. Altogether, these studies show the potential for RE as a natural alternative to synthetic food preservatives, although optimization of the extract needs to be done to achieve the maximum benefits of RE.

In vivo GI Health Benefits

In addition to being a natural food preservative, evidence suggests that rosemary extract may improve gastrointestinal health. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is one area in particular that RE administration has been evaluated [7]. Due to its anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, RE has been hypothesized to prevent or treat IBD. To test this hypothesis, several in vivo models of acute colitis have been developed to study the underlying mechanisms of IBD and to test the efficacy of various compounds against the disease (Table IV). These models evaluate parameters such as pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, myeloperoxidase activity, colonic weight and length, and histological assessment of colonic sections and crypt formation to determine the effectiveness of treatment [25-27].

Rosemary has been evaluated in these in vivo models with positive results for preventing and treating colitis. In a study in rats given TNBS to induce colitis, RE and REO at doses above 100 mg/kg given 6 consecutive days were shown to reduce the weight per length ratio of the colon, which is increased in moderate to severe colitis [11]. Treatments with RE and REO were also shown by histological analysis to significantly reduce inflammation, crypt damage, and total colonic index. This study attributed the majority of the effects of RE to RA due to its anti-oxidant properties and high lipid solubility. Analysis of REO by GC-MS revealed the most abundant component was α-pinene, which has significant anti-inflammatory activity through inhibition of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (Nf-κB) nuclear translocation [28].

In vitro, RE possesses anti-inflammatory properties that translate to being effective at treating in vivo colitis models. In RAW 264.7 macrophages stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to induce inflammatory conditions, RE lowered expression levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and nitrite levels compared to LPS stimulation alone [4]. The redox sensitive transcription factor Nf-κB nuclear translocation was also decreased, along with iNOS and COX-2 expression, when treated with 5 and 10 μg/mL RE. In mice induced with colitis by dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) administration, disease activity index, scored by stool consistency, body weight loss, and presence of blood in feces, improved with treatment of 50 and 100 mg/kg RE compared to DSS only. Mice given RE also had less apparent colonic damage and leukocyte infiltration. Analysis of intestinal proteins also revealed that mice treated with RE had lower expression of the inflammatory markers NF-kB, COX-2, and iNOS, similar to the in vitro results. The study also found that DSS treatment increased the expression of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) proteins p38, ERK, and JNK. However, RE treatment was able to restore the expression of these proteins to control values. These results suggest the in vivo efficacy for RE to treat colitis through its anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory function at doses that do not present toxicity risk.

Conclusion

This review summarizes food preservation properties and the health promoting properties to the gastrointestinal tract with rosemary extracts. Rosemary extracts and essential oils present promising methods of natural food preservation due to their bioactivities that prevent many types of food spoilage and microbial growth. Beyond food preservation, however, these herbs have also been shown to promote GI health. Studies performed in mice have shown positive effects of lowering GI inflammation and lessening the symptoms of DSS exposure. These studies suggest that health promoting properties specific to gastrointestinal health are an additional benefit to using rosemary extract as a natural food preservative.

Figure 1.

Phytochemicals from RE and REO reported in the literature.

Table I.

List of publications detailing rosemary extracts and most abundant phytochemicals detected

| Extraction method | Major phytochemicals | Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Essential oil | 1,8-cineole (43.77% mass/total oil content) Camphor (12.53%) α-pinene (11.51%) β-pinene (8.16%) β-caryophyllene (3.93%) |

[29] |

| Essential oil | α-pinene (39.8% total oil composition) 1,8-cineole (18.3%) Para-cymene-9-ol (7.7%) Camphor (7.4%) Camphene (6.6%) |

[30] |

| Methanol | Rosmarinic acid (8% mass/dry weight) Carnosic acid (6%) |

[31] |

| Acetonitrile + 2% formic acid | Carnosic acid (121.08 mg/mL) Carnosol (28.89 mg/mL) Verbenone (77.59 μg/g) α-thujene (76.26 μg/g) Bornyl acetate (54.02 μg/g) |

[32] |

| Supercritical fluid | Carnosic acid (8.30% dry weight) Micromeric acid (4.70%) Betulinic acid (3.80%) Ursolic acid (2.15%) Carnosol (1.00%) |

[33] |

| Ethanol (70%) | Diacetone alcohol (72.80 mg/g dry weight) Rosmarinic acid (50.43 mg/g) Butyraldehyde semicarbazone (4.63 mg/g) 6-Iodo-2-methylquinazolin- 4(3H)-one (3.60 mg/g) Borneol (2.31 mg/g) |

[34] |

| Methanol (70%) | Rosmarinic acid (60.89 mg/g dry weight) Diacetone alcohol (54.58 mg/g) Propyl-propanedioic acid (14.45 mg/g) 2,1,3-benzothiadiazole (5.48 mg/g) 6-Iodo-2-methylquinazolin- 4(3H)-one (4.93 mg/g) |

[34] |

| Hydroalcoholic (65% ethanol) | Rosmarinic acid (398.1 μg/mL) Luteolin (199.5 μg/mL) Caffeic acid (114.4 μg/mL) Carnosol (80.1 μg/mL) Apigenin (39.6 μg/mL) |

[28] |

Table II.

In vivo colitis models with rosemary extracts and essential oil

| Model | Experimental conditions | Significant findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| TNBS-induced colitis rats |

|

|

[30] |

| TNBS-induced colitis rats |

|

|

[35] |

| DSS-induced colitis mice |

|

|

[36] |

Acknowledgements

Johnson JJ is supported by the National Institutes of Health (R37 CA227101)

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors do not declare any conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.al-Sereiti MR, Abu-Amer KM, and Sen P, Pharmacology of rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis Linn.) and its therapeutic potentials. Indian J Exp Biol, 1999. 37(2): p. 124–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hegazy AM, et al. Hypolipidemic and hepatoprotective activities of rosemary and thyme in gentamicin-treated rats. Hum Exp Toxicol, 2018. 37(4): p. 420–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lipton SA, et al. Therapeutic advantage of pro-electrophilic drugs to activate the Nrf2/ARE pathway in Alzheimer's disease models. Cell Death Dis, 2016. 7(12): p. e2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borras-Linares I, et al. A bioguided identification of the active compounds that contribute to the antiproliferative/cytotoxic effects of rosemary extract on colon cancer cells. Food Chem Toxicol, 2015. 80: p. 215–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berrington D and Lall N, Anticancer Activity of Certain Herbs and Spices on the Cervical Epithelial Carcinoma (HeLa) Cell Line. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med, 2012. 2012: p. 564927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cuvelier M-E, Richard H, and Berset C, Antioxidative activity and phenolic composition of pilot-plant and commercial extracts of sage and rosemary. J Amer Oil Chem Soc, 1996. 73: p. 645. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amar Y, et al. Phytochemicals, Antioxidant and Antiproliferative Properties of Rosmarinus officinalis L on U937 and CaCo-2 Cells. Iran J Pharm Res, 2017. 16(1): p. 315–327. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nieto G, Banon S, and Garrido MD, Administration of distillate thyme leaves into the diet of Segurena ewes: effect on lamb meat quality. Animal, 2012. 6(12): p. 2048–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nieto G, et al. Dietary administration of ewe diets with a distillate from rosemary leaves (Rosmarinus officinalis L.): influence on lamb meat quality. Meat Sci, 2010. 84(1): p. 23–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nieto G, Bañón S, and Garrido MD, Incorporation of thyme leaves in the diet of pregnant and lactating ewes: Effect on the fatty acid profile of lamb. Small Ruminant Research, 2012. 105(s1-3): p. 140–147. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aguilar F, et al. , Use of Rosemary Extracts as a food additive - Scientific opinion of the panel on food additives, flavourings, processing aids and materials in contact with food. The EFSA Journal, 2008. 8(7): p. 1–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hassani FV, Shirani K, and Hosseinzadeh H, Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) as a potential therapeutic plant in metabolic syndrome: a review. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol, 2016. 389(9): p. 931–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore J, Yousef M, and Tsiani E, Anticancer Effects of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) Extract and Rosemary Extract Polyphenols. Nutrients, 2016. 8(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raskovic A, et al. Analgesic effects of rosemary essential oil and its interactions with codeine and paracetamol in mice. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci, 2015. 19(1): p. 165–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi SH, et al. Development and Validation of an Analytical Method for Carnosol, Carnosic Acid and Rosmarinic Acid in Food Matrices and Evaluation of the Antioxidant Activity of Rosemary Extract as a Food Additive. Antioxidants (Basel), 2019. 8(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakagawa S, Hillebrand GG, and Nunez G, Rosmarinus officinalis L. (Rosemary) Extracts Containing Carnosic Acid and Carnosol are Potent Quorum Sensing Inhibitors of Staphylococcus aureus Virulence. Antibiotics (Basel), 2020. 9(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghasemzadeh Rahbardar M and Hosseinzadeh H, Therapeutic effects of rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) and its active constituents on nervous system disorders. Iran J Basic Med Sci, 2020. 23(9): p. 1100–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Albalawi A, et al. Protective effect of carnosic acid against acrylamide-induced toxicity in RPE cells. Food Chem Toxicol, 2017. 108(Pt B): p. 543–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vázquez NM, et al. Carnosic acid acts synergistically with gentamicin in killing methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates. Phytomedicine, 2016. 23(12): p. 1337–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernardes WA, et al. Antimicrobial activity of Rosmarinus officinalis against oral pathogens: relevance of carnosic acid and carnosol. Chem Biodivers, 2010. 7(7): p. 1835–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klancnik A, et al. In vitro antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of commercial rosemary extract formulations. J Food Prot, 2009. 72(8): p. 1744–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aruoma OI, et al. Antioxidant and pro-oxidant properties of active rosemary constituents: carnosol and carnosic acid. Xenobiotica, 1992. 22(2): p. 257–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park J, Rho SJ, and Kim YR, Enhancing antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of carnosic acid in rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) extract by complexation with cyclic glucans. Food Chem, 2019. 299: p. 125119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ortuño J, Serrano R, and Bañón S, Incorporating rosemary diterpenes in lamb diet to improve microbial quality of meat packed in different environments. Anim Sci J, 2017. 88(9): p. 1436–1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sann H, et al. Efficacy of drugs used in the treatment of IBD and combinations thereof in acute DSS-induced colitis in mice. Life Sci, 2013. 92(12): p. 708–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh V, et al. Microbiota fermentation-NLRP3 axis shapes the impact of dietary fibres on intestinal inflammation. Gut, 2019. 68(10): p. 1801–1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walldorf J, et al. In-vivo monitoring of acute DSS-Colitis using Colonoscopy, high resolution Ultrasound and bench-top Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Mice. Eur Radiol, 2015. 25(10): p. 2984–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cattaneo L, et al. Anti-Proliferative Effect of Rosmarinus officinalis L. Extract on Human Melanoma A375 Cells. PLoS One, 2015. 10(7): p. e0132439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rašković A, et al. Antioxidant activity of rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) essential oil and its hepatoprotective potential. BMC Complement Altern Med, 2014. 14: p. 225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Minaiyan M, et al. Effects of extract and essential oil of Rosmarinus officinalis L. on TNBS-induced colitis in rats. Res Pharm Sci, 2011. 6(1): p. 13–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Erkan N, Ayranci G, and Ayranci E, Antioxidant activities of rosemary (Rosmarinus Officinalis L.) extract, blackseed (Nigella sativa L.) essential oil, carnosic acid, rosmarinic acid and sesamol. Food Chem, 2008. 110(1): p. 76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mena P, et al. Phytochemical Profiling of Flavonoids, Phenolic Acids, Terpenoids, and Volatile Fraction of a Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) Extract. Molecules, 2016. 21(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borrás-Linares I, et al. A bioguided identification of the active compounds that contribute to the antiproliferative/cytotoxic effects of rosemary extract on colon cancer cells. Food Chem Toxicol, 2015. 80: p. 215–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kozłowska M, et al. , CHEMICAL COMPOSITION AND ANTIBACTERIAL ACTIVITY OF SOME MEDICINAL PLANTS FROM LAMIACEAE FAMILY. Acta Pol Pharm, 2015. 72(4): p. 757–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mueller K, Blum NM, and Mueller AS, Examination of the Anti-Inflammatory, Antioxidant, and Xenobiotic-Inducing Potential of Broccoli Extract and Various Essential Oils during a Mild DSS-Induced Colitis in Rats. ISRN Gastroenterol, 2013. 2013: p. 710856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Medicherla K, et al. Rosmarinus officinalis L. extract ameliorates intestinal inflammation through MAPKs/NF-κB signaling in a murine model of acute experimental colitis. Food Funct, 2016. 7(7): p. 3233–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]