SUMMARY

Electrical activity in the brain and heart depends on rhythmic generation of action potentials by pacemaker (HCN) ion channels whose activity is regulated by cAMP binding1. Previous work uncovered evidence for both positive and negative cooperativity in cAMP binding2,3, but such bulk measurements suffer from limited parameter resolution. Efforts to eliminate this ambiguity using single-molecule techniques have been hampered by inability to directly monitor individual ligand molecules binding to membrane receptors at physiological concentrations. Here, we overcome these challenges using nanophotonic zero-mode waveguides4 to directly resolve binding dynamics of individual ligands to multimeric HCN1 and HCN2 ion channels. We show that cAMP binds independently to all four subunits when the pore is closed, despite a subsequent conformational isomerization to a flip state at each site. The different dynamics in binding and isomerization likely underlie physiologically distinct responses of each isoform to cAMP5 and provide direct validation of the ligand-induced flip state model6-9. Our new approach for observing stepwise binding in multimeric proteins at physiologically relevant concentrations can directly probe binding allostery at single-molecule resolution for other intact membrane proteins and receptors.

Ligand binding to allosteric sites of transmembrane receptors such as ion channels and G-protein coupled receptors underpins many signaling transduction pathways. Hyperpolarization-activated, cyclic-nucleotide gated (HCN) ion channels are one receptor class that contributes to re-initiation of action potentials, a mechanism critical for cardiac pacemaking and rhythmic neuronal activity1,10. During “Fight or flight” response11, cAMP binding to pacemaker channel modulates its activity and thereby regulates heart rate. Each HCN channel, which is a tetramer, can bind up to four cAMP molecules via its cyclic nucleotide binding domains (CNBDs) but the mechanism of binding and modulation remains controversial. The Hill coefficient for HCN2 dose response curve exceeds unity and the channel activity reaches its maximum at 60% ligand occupancy, suggesting cooperative gating12. Ligand binding studies using patch clamp fluorometry (PCF) and isothermal titration calorimetry (ICT) have led to unusual and complex models positing both positive and negative cooperativity depending on the ligation state2,3,13. As with any multi-parameter binding schemes based on ensemble data, these models suffer from the problem of parameter identifiability14.

The definitive approach for obtaining binding kinetics and equilibria of each ligation state is to directly monitor ligand binding at the single-molecule level. Specifically, direct resolution of ligand binding is needed to track reaction pathway since ligand occupancy is the principal reaction coordinate for binding and gating transitions15-18. Intramolecular single-molecule Förster resonance energy transfer (smFRET) is a powerful technique to quantitate ligand induced structural dyamics19-24 However, direct measurements of cooperative ligand binding in multimeric proteins at the single-molecule level,25,26 including dynamics, remains an elusive frontier. A key challenge is performing physiologically relevant measurements above the concentration barrier of diffraction-limited light, where signal-to-background decays precipitously27. Even intermolecular smFRET, which can resolve single fluorescent ligands at low 100s of nM28,29, has not been demonstrated at the μM concentrations required for most ion channel modulators like cAMP30. Overcoming this concentration barrier is critical for advancing understanding of ligand gating multimeric ion channels and receptors.

Nanophotonic zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs) offer unique access to high concentrations4. ZMWs possess sub-diffraction-limit observation volumes which can resolve single binding events at μM31-34 and even mM35 concentrations. ZMWs facilitate long observations times needed to adequately sample ligand binding to each multimer subunit and provide the high signal-to-background needed to discern stacked binding events with increasing shot noise36.

Herein, we reveal the mechanism of cAMP association to purified HCN1 and HCN2 channels at the single-molecule level by using ZMWs to monitor binding of a fluorescent cAMP (fcAMP) and quantifying the transient occupation of all intermediate bound states (fully unbound to fully bound). We find that fcAMP binding is independent for both isoforms when the pore is closed, and that each subunit independently isomerizes into a longer-lived bound conformation. We observe differences in isomerization kinetics between the two isoforms which may underlie the physiologically distinct effects of cAMP on their activation. Overall, our approach provides an unprecedented view of early binding transitions in a multimeric ion channel and can be broadly applied to unambiguously quantitate binding cooperativity in other membrane receptors.

RESULTS

Binding of individual ligands to HCN channels

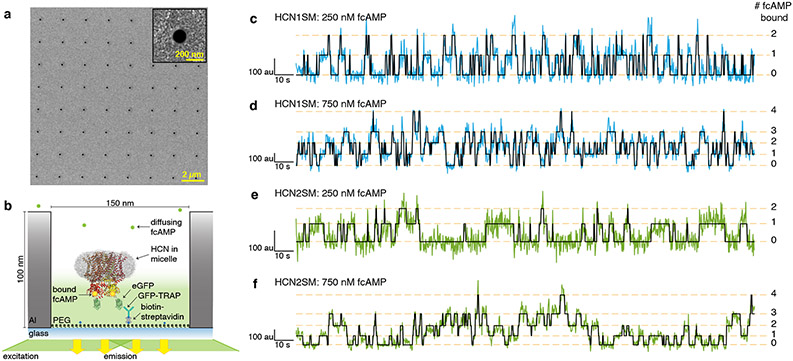

Full-length HCN1 and HCN2 channels were engineered with an N-terminal eGFP on each subunit for purification and imaging (HCN1SM and HCN2SM, Methods). Electrophysiological characterization revealed activation upon hyperpolarization and modulation by cAMP consistent wild type channels37, including a minor shift in midpoint voltage (V1/2) of activation for HCN1SM (+2.1 mV) and a larger shift for HCN2SM (+20.6 mV) under saturating cAMP (Extended Data Fig. 1a, b). Both channels were purified from HEK293T cells into detergent micelles using affinity and size exclusion chromatography (Methods, Extended Data Fig. 1c). Single-molecule photobleaching analysis confirmed the tetrameric assembly of each purified isoform under imaging conditions (Methods, Extended Data Fig. 1d).

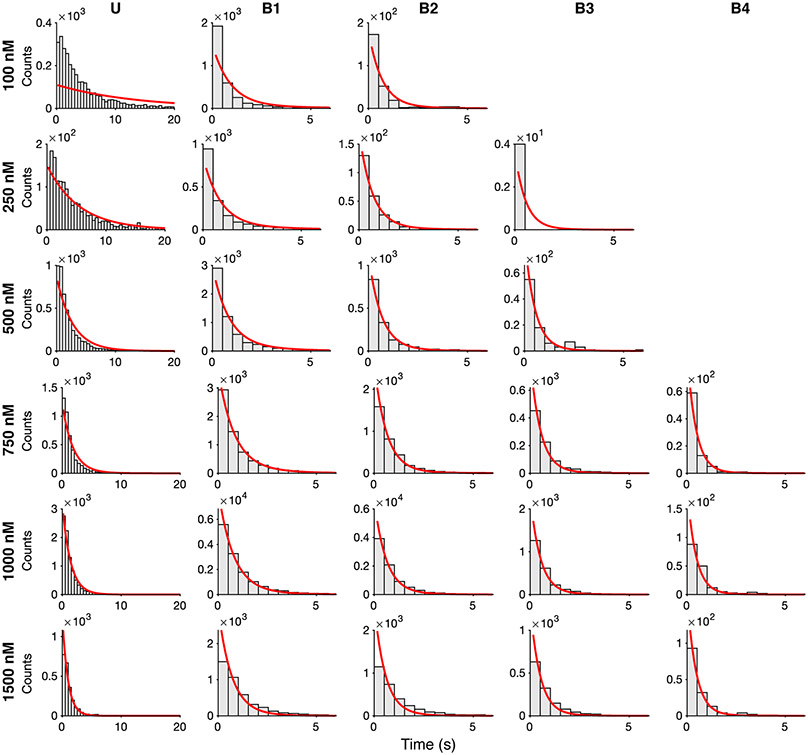

HCN molecules were sparsely deposited into ZMWs, which were fabricated via electron-beam lithography (Fig. 1a, Extended Data Fig. 2, Methods)4,38, to promote single occupancy (Fig. 1b). Binding activity at various concentrations of DY-547-labeled cAMP (fcAMP, Fig. 1c-f, Extended Data Fig. 3-4, Supplementary Table 1) was monitored for at least 300 s at 10 Hz. Transitions between liganded states, unbound (U) or multiply bound (B1, B2, B3, and B4) were determined separately for each molecule using an unsupervised learning algorithm, DISC (Fig. 1c-f, Extended Data Fig. 3, Extended Data Fig. 4, Methods)36.

Fig. 1: fcAMP binding to intact HCN channels in ZMWs.

(a) Representative scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of ZMWs. All ZMW chips used (n = 7) were confirmed by SEM. (b) Cartoon (not to scale) of ZMW with deposited eGFP-tagged HCN for fcAMP binding experiments (eGFP: PDB 2Y0G, HCN1: PDB 6UQG). (c-f) Representative fluorescence/time trajectories of fcAMP binding to HCN1SM and HCN2SM at 250nM and 750nM fcAMP overlaid with idealized fit (black). Only 120 of 300 seconds are shown. Additional trajectories provided in Extended Data Fig. 3-4.

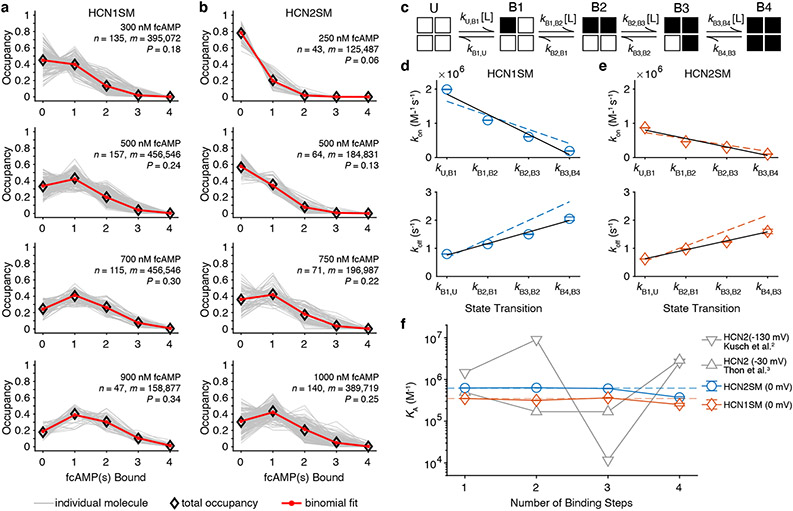

fcAMP binds non-cooperatively to HCN isoforms

First, we determined if the cAMP binding promotes cooperativity between binding domains. If binding to each subunit is non-cooperative, the occupancy of each ligation state obtained from idealized trajectories should follow a binomial distribution39. Across all recordings, binomial fits accounted for 94% of observed state occupancy distribution of HCN1SM and 93% for HCN2SM, as measured by root mean squared error, suggesting independent binding (Fig. 2a, 2b, Supplementary Table 2, Methods).

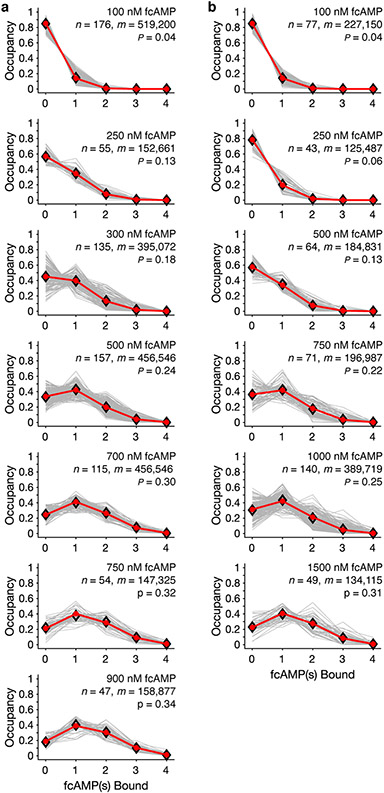

Fig. 2: fcAMP binds non-cooperatively to both HCN isoforms.

Normalized state occupancy distributions for HCN1SM (a) and HCN2SM (b) at various fcAMP concentrations with total number of molecules (n), data points (m) and binomial success rate for four subunits (P) indicated (see also Supplementary Table 2 and Extended Data Fig. 5). (c) Sequential ligand binding model (Model 1 in Supplementary Table 4). White squares indicate unbound (U), black squares indicate bound (B), and L represents ligand. Optimized transition rates (mean ± s.e.m.) for sequential binding (Supplementary Table 5) for HCN1SM (d) and HCN2SM (e) with a linear fit (black solid). Dashed lines indicate expected rates from constrained and sequential non-cooperative binding model (Model 2 in Supplementary Table 4). (f) Equilibrium association constants (KA) for each ligand binding step (mean ± s.e.m). Dashed lines indicate fits from Model 2. Previously reported KA values for fcAMP binding to HCN2 using PCF of open (−130 mV)2 and closed channels (−30 mV)3 shown for comparison (grey). For d, e, f, parameters were fit to all events across all fcAMP concentrations (HCN1SM: 739 molecules, 180,480 events; HCN2SM: 444 molecules, 82,030 events).

Next, we extracted transition rates by first optimized an unconstrained sequential model with four binding transitions (Fig. 2c, Model 1 in Supplementary Table 4) and the rates displayed a strong linear correlation between successive steps consistent with independent binding (Fig. 2d, 2e). A simpler model where binding of individual ligands is equal, independent, and governed by common rate constants39 (Fig. 2d, 2e, dashed lines, Model 2 in Supplementary Table 4) converges to similar rates as the unconstrained model. Minor deviations between these models likely arise from fewer observations of B3 and B4, our finite collection rate (10 Hz), and decreased signal-to-noise at higher fcAMP concentrations, all of which can obscure fast transitions (Supplementary Fig. 2). Equilibrium association constants (KA) for each binding step also support non-cooperativity for both isoforms, a stark contrast to PCF results reported elsewhere (Fig. 2f)2,3. The slight weak negative cooperativity between B3→B4, arises from increased probability of missing B4 transitions and could be reproduced in simulations (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Taken together, state occupancies and transition rates unambiguously demonstrate that fcAMP binds non-cooperatively to intact HCN1SM and HCN2SM when the pore is closed, and the voltage-sensor is in resting conformation. Our findings stand in stark contrast to the oscillating behavior from models fit from PCF data for HCN2 with the voltage-sensor in either activated or resting state3,12 and the negative cooperativity observed in ITC studies of isolated CNBDs13.

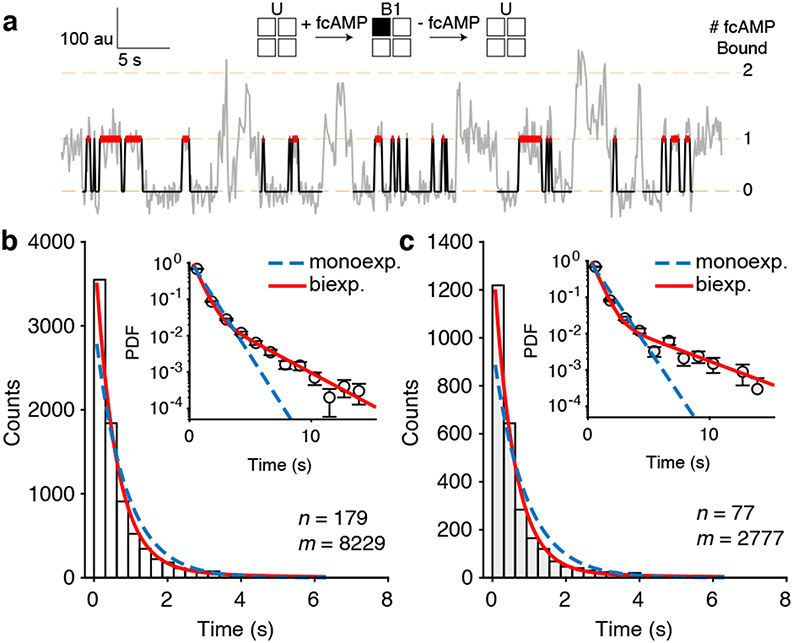

Ligand binding is followed by conformation flip

Our previous single-molecule studies on isolated HCN2 CNBDs revealed a second reversible conformational state following ligand binding32,35. Combined with structural data, we postulated that this second conformation corresponds to a coordinated rotation of the N- and C-terminal α-helices about the rigid CNBD β-barrel32,, reminiscent of a catch-and-hold mechanism of ligand-gated channels6-9. A similar model of ligand-docking and CNBD isomerization was suggested by double electron-electron resonance (DEER) spectroscopy40. We and others hypothesized that this ligand-induced "flipped" state may allosterically modulating the pore through the C-linker40,41. Whether these conformational dynamics observed in isolated CNBDs are preserved in full-length channels remained an open question.

We first analyzed dwell times of singly-liganded states immediately preceded and followed by unbound states (U→B1→U) since these dwell times provide the most accurate representation of individual binding dynamics without truncation from additional binding (Fig. 3a). Maximum likelihood estimations of isolated-B1 dwell time distributions required two exponential components for both HCN1SM and HCN2SM (Fig. 3b, 3c), with the monoexponential fit conspicuously failing, particularly for HCN2SM, at both early and late times (Extended Data Fig. 6, Extended Data Fig. 7, Supplementary Table 3). The contribution of static disorder to the histogram can also be ruled out (Extended Data Fig. 8). These analyses suggest an isomerization into a flipped state at each subunit following ligand binding in intact HCN channels. Critically, as binding is non-cooperative, this conformational change does not influence ligand association to neighboring subunits when the channel is closed.

Fig. 3: Ligand binding induces a conformational change at each HCN subunit.

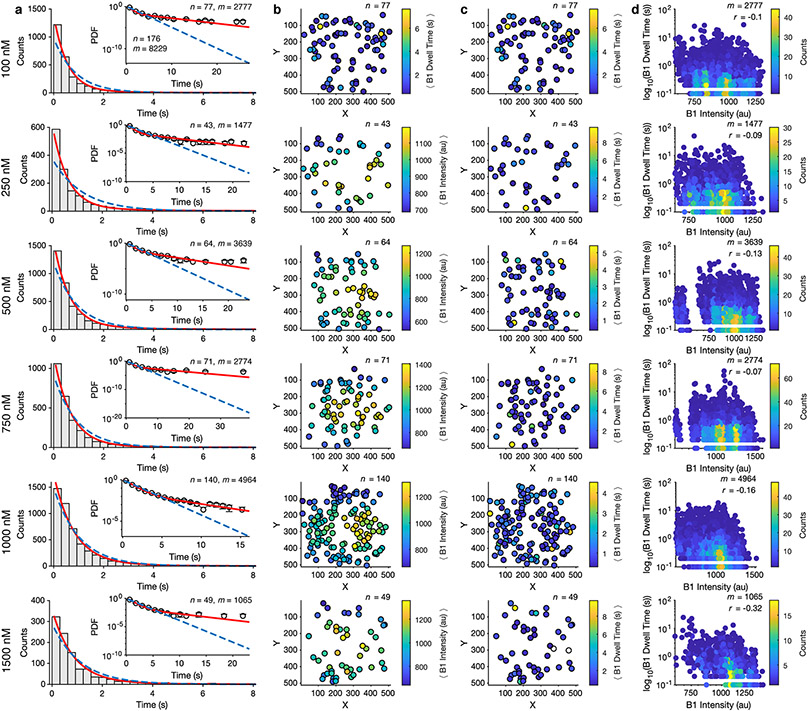

(a) Representative fcAMP binding trajectory with identified isolated-B1 dwell times (red). (b, c) Dwell time distributions of isolated-B1 events for HCN1SM (b) and HCN2SM (c) at 250 nM fcAMPoverlaid with monoexponential (blue dashed) and biexponential (red) fits (Methods). In each panel, n is the total number of molecules and m is the total number of dwell times. Abscissa values correspond to the center of the histogram bars. Inset of (b) and (c) shows probability density function (PDF) of each distribution with the ordinate on a log scale to highlight less frequent but long-lived bound durations. Error bars for each bin are calculated as the error of binomial distribution. See Extended Data Fig. 6-7 for isolated-B1 dwell time distributions and Supplementary Table 3 for all fit parameters.

Binding dynamics underlie ligand efficacy

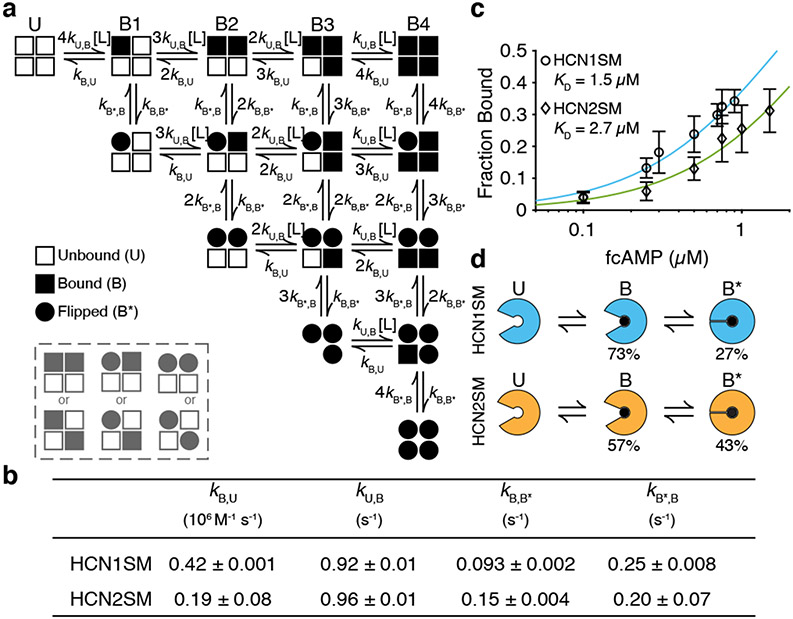

The existence of the ligand-induced flipped state across all CNBDs was assessed by testing two models featuring four independent binding steps either without (Model 2 in Supplementary Table 4) or with ligand induced isomerization upon binding (Fig. 4a, Model 3 in Supplementary Table 4). Both models were validated using representative simulations to ensure reliability (Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 2).

Fig. 4: A revised flip state model.

(a) Non-cooperative binding model with a reversible conformational flip at each subunit following ligand binding (L). Grey box indicates alternative binding patterns. (b) Optimized transitions rates of a HCN1SM and HCN2SM. Errors are s.e.m. (c) Binding curve of HCN1SM and HCN2SM at various fcAMP concentrations overlaid with predictions from a (mean ± s.d.). Number of molecules for each fcAMP concentration is provided in Supplementary Table 1. (d) Hypothesized scheme wherein each subunit independently converts between unbound (U), bound (B), and flipped (B*) states.

Transition rates were globally optimized using QuB and ranked by Bayesian information criterion (BIC) to optimize goodness of fit and model complexity (Methods) 42-44. Consistent with studies on isolated monomeric CNBDs32,35 and the isolated-B1 dwell times above, the model featuring a conformational flip at each subunit was preferred for both HCN1SM and HCN2SM (Supplementary Table 4). Therefore, the null hypothesis of purely sequential binding can be rejected in favor of a scheme featuring reversible conformational flips of ligand-occupied subunits.

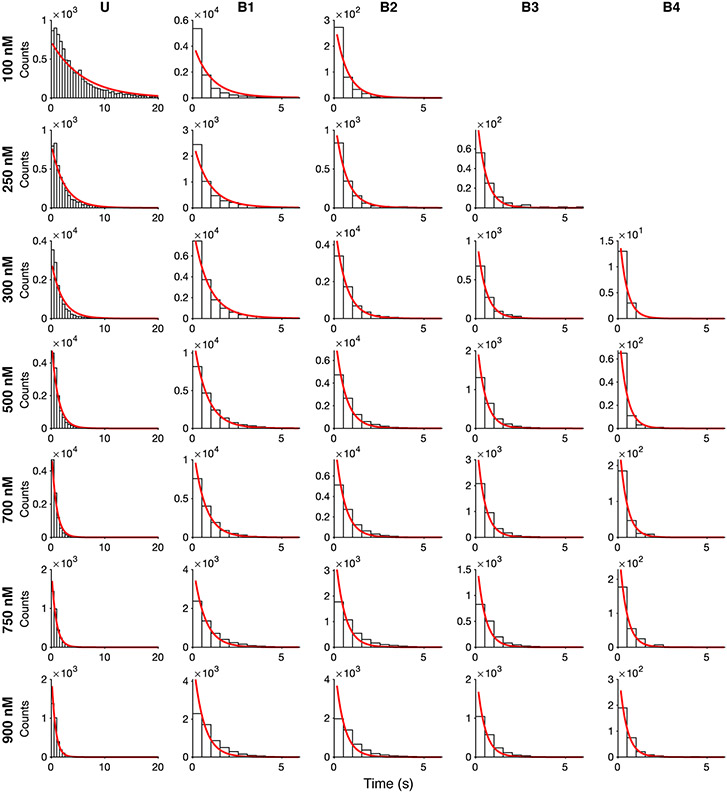

Optimized transition rates from Model 3 provide insights into mechanistic differences between HCN isoforms (Fig. 4b). Simulations of optimized rates for each isoform match experimentally observed fractional occupancy (Fig. 4c) and dwell time distributions of each liganded state (Extended Data Fig. 9, Extended Data Fig. 10). HCN1SM and HCN2SM exhibit similar unbinding rates, but the ligand association rate of HCN1SM is nearly twice as fast. Each isoform exhibits similar rates of exiting the flipped state, but HCN1SM spends only 27% of the time in the flipped state for any bound event, compared to 43% for HCN2SM due to its faster entry rate. These results suggest that differences in cAMP modulation ability of HCN channels do not derive only from differences in ligand association, but also from the duration of time spent in a second metastable conformation.

DISCUSSION

Here, we directly quantitated the transient occupation of each of the four ligation states of two functionally distinct HCN isoforms at the single-molecule level using ZMWs. Our approach overcomes the current limitations of ensemble measurements and offers several key insights into the mechanism of ligand activation. First, we find that the binding of each of the four fcAMPs to functional HCN1SM or HCN2SM channels occurs independently when the channel pore is closed in absence of membrane potential. Although previous observations that isolated CNBDs oligomerize upon cAMP binding suggested cooperativity41,45, there is no evidence that this association also occurs in intact channels. Indeed, single-particle reconstructions of HCN channels do not show any evidence of cAMP induced association between CNBDs46. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that ligand binding is cooperative if the membrane is sufficiently hyperpolarized to open HCN channels.

Second, we resolved a second, metastable conformational state following ligand binding at each subunit. Using single-channel analysis on glycine receptors, Sivilotti and colleagues postulated that ligand binding is followed by a global and coordinated conformational rearrangement to stabilize binding6-9. In contrast to the single unique conformation predicted from these models, our data instead show that the flip state is an ensemble of conformations with independent conformational changes at each subunit. Our revised flip state model closely matches structural data from isolated CNBDs32,40 and full-length channel46. Whether these previously identified structural transitions correspond to the kinetic intermediates observed here remains to be determined.

Finally, we uncover subtle but important differences in the dynamics between the two isoforms. Despite similar fcAMP unbinding rates, HCN2SM subunits enter the flip state faster, leading to increased bound durations. This suggest that prolonged duration in the stabilizing flip conformation may underlie the stronger effect of cAMP on pore modulation in HCN2 than HCN1. Our data therefore contradicts the notion that HCN1 channels exists primarily in a high affinity conformation (pre-activated state model) leading to unresponsiveness to cAMP binding45.

Overall, our approach is the first to dynamically monitor the binding of multiple individual ligands to a membrane receptor at single-molecule resolution and offers a new paradigm for studying ligand-dependent activation in many multimeric ligand-gated ion channels and receptors (see also Supplementary Note 1). These measurements can quantitate ligand-induced gating processes and can potentially be combined with smFRET to identify key structural transitions. Our approach can be broadly utilized to study the effect of allosteric modulators and drugs, including agonists, antagonists, and partial and inverse agonists on ligand binding to clarify their mechanism of action, bringing us closer to a comprehensive understanding of ligand-dependent activation in membrane receptors.

METHODS

Generation of Single-Molecule Constructs

HCN1SM was based off a cryoEM study of HCN146. We modified the human ortholog of HCN1 by deleting amino acids 636-865 on the C-terminal tail and on the N-terminus the construct was tagged with eGFP and a Twin-strep affinity purification tag. The Twin-strep tag was used for affinity purification while the eGFP tag was used for both single-molecule localization and tethering to streptavidin-coated surfaces via a biotinylated GFP nanobody (GFP-TRAP). The mouse ortholog of HCN2 which was modified to yield HCN2SM. Amino acids corresponding to residues 686-860 on the C-terminus were deleted to improve the biochemical behavior of the purified protein and the amino acids corresponding to residues 1-136 on the N-terminus were replaced by residues 1-98 from the human HCN1 ortholog to overcome the high G/C content. HCN2SM, like HCN1SM, was tagged on the N-terminus with Twin Strep-tag and eGFP.

Cell Culture and Electrophysiology

HEK293T adherent cells (ATCC) were cultured in DMEM (Sigma) with 10% FBS (Gibco). For transient transfection, cells were seeded in 35 mm cell culture dishes. After 16-20 hours, the cells were transiently transfected with 2.5 μg of either HCN1SM or HCN2SM plasmid DNA using TransIT-293 reagent (MIRUS) as per manufacturer’s instructions. In case of HCN2SM transfected cells, 10 mM sodium butyrate was added 12 hours post transfection to boost the protein expression. 48–60 hours post transfection, the solution in the dish was exchanged with external solution (130 mM NaCl, 30 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 5 mM HEPES, 0.5mM MgCl2, pH 7.4; 310 mOsm). Recording electrodes (Drummond scientific, OD 1.6mm) with a resistance of around 2-4 MΩ were pulled using P-97 puller (Sutter Instrument Co.). Electrodes were fire polished and filled with the internal solution (130 mM KCl, 10 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 0.5mM MgCl2 and 5 mM HEPES, 2mM ATP (Adenosine triphosphate sodium salt), pH 7.2; 295 mOsm). Where indicated, internal solution also contained 500 μM cAMP (cyclic adenosine monophosphate sodium salt). Whole-cell recordings were obtained at room temperature (23°C) using an Axopatch 200A amplifier, a Digidata 1550B digitizer and pCLAMP software (version 10.7, Molecular Devices). Recordings were low pass filtered at 5 kHz and sampled at 20 kHz. Activation curves were obtained by holding the cell at 0 mV and then hyperpolarizing to −30 to either −130 mV (for HCN1SM) or −150 mV (for HCN2SM) in 10 mV decrements, followed by a test pulse at −130 mV. All the statistical analysis was performed using OriginPro 2020b and the data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. (Extended Data Fig. 1a, b).

Protein Expression and Purification

cDNA corresponding to HCN1SM in the modified pEG BacMam vector47 was extracted from large volumes of bacterial cultures using Endotoxin free Plasmid Purification kits (Qiagen) and transfected into suspension cultures of Freestyle HEK293 cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using Trans-IT Pro Transfection reagent (MIRUS) following manufacturer’s instructions. Post transfection, cells were grown at 12-14 hours at 37°C, following which sodium butyrate was added to the cultures to a final concentration of 10mM and cultures were grown at 30°C for another 48 hours. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3000xg for 20 minutes and washed twice with chilled 150 mM NaCl, 2 0mM Tris, pH = 8.0. Cell pellets were finally resuspended in lysis buffer (300 mM NaCl, 40 mM Tris, 10 mM DTT, 20% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 1% L-MNG, 2 mM CHS (Cholesterol Hemi Succinate), pH = 8.0 supplemented with 1x Halt protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher Scientific), briefly sonicated on ice, and incubated at 4°C with gentle agitation for ~2 hours. The detergent extract was next spun at ~100,000xg for 1.5 hours and the supernatant was purified using Streptactin affinity resin (IBA Life Sciences). Protein bound resin was washed with 10 bed volumes of wash buffer (300 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris, 10 mM DTT, 5% glycerol, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% Digitonin (Calbiochem), pH 8.0) and the protein was eluted in wash buffer with 5 mM desthiobiotin. The resultant eluent was concentrated using 100 MWCO centrifugal filters to ~500 μl and further purified using size exclusion chromatography (SEC) on the Superose 6 Increase column at 4 °C. The SEC Buffer used was 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris, 10 mM DTT, 0.1 mM GDN, pH = 8.0. All single-molecule experiments were performed within the peak fraction of the protein (which routinely contained 30-100 nM protein) within 2-6 hours of the SEC step (Extended Data Fig. 1c).

HCN2SM was expressed in suspension cultures of Freestyle HEK293 cells as described above for HCN1EM. Purification of HCN2SM was modified from that of HCN1SM in the following ways. The lysis buffer used 1% Digitonin (instead of L-MNG/CHS) and 30% glycerol and the wash/elution buffers for affinity purification included 20% glycerol (instead of 5%). These modifications significantly improved the polydispersity of the SEC profile with HCN2SM, although the profile still exhibited significant aggregation in the affinity purified material. Only the peak SEC fraction (containing 30-50 nM protein) was used for our studies and binding measurements were performed within 2-6 hours of the final protein purification step (Extended Data Fig. 1c).

Note, although the extraction and affinity steps of HCN1SM and HCN2SM used different detergents, the final purification step included exchanging both proteins into 0.1 μM GDN during SEC. The only difference in the conditions for HCN1SM and HCN2SM is the glycerol content which was adjusted to enhance monodispersity- a widely used measure of protein stability-in the SEC profile. Prior to single-molecule imaging, HCN1SM and HCN2SM were extensively washed in GDN containing SEC buffer without glycerol. All single-molecule data were collected under identical buffer conditions for HCN1SM and HCN2SM. We note that the relative differences in estimated binding affinities of intact HCN isoforms from single-molecule data matches those reported for the soluble CNBDs45.

ZMW Fabrication

ZMWs were fabricated at the Center for Nanophase Materials Sciences facility at Oak Ridge National Lab using positive-tone electron-beam lithography4. Cover glasses (Fisher Scientific Cat. No. 12-548-C, 130-170μm thickness) were cleaned by soaking in 5 parts deionized water, 1 part 30% hydrogen peroxide, 1 part 35% ammonium hydroxide for 15 minutes at 75°C. Substrates were rinsed, dried with N2 gas, and plasma-cleaned with a Harrick PDC-32G for 10 minutes to remove any remaining organic impurities on the surface. The substrates were coated with thermally evaporated aluminum at a rate of 2 Å/s using a JEOL dual source E-beam evaporator to a final thickness of 100 nm. Substrates were spin-coated with the positive tone electron-beam photoresist ZEP520A (ZEONREX Electronic Chemicals) for 45 s at 2,000 rpm followed by baking for 2 minutes at 180°C. ZMW features of 150 nm diameter dots were patterned using JEOL JBX-9300FS E-beam lithography system with a base dose of 450 μC cm−2, 100 kV acceleration voltage, and 2 nA beam current. Following exposure, substrates were developed in xylenes for 30 s, rinse with isopropyl alcohol, and dried with N2. 100 nm of aluminum was dry etched in an Oxford Plasmalab System 100 Reactive Ion Etcher with a mixture of 30 standard cubic centimeters (sccm) chlorine (Cl2) and 10 sscm boron trichloride (BCl3) gasses at 50°C for 60 s. Following etching, the substrates were plasma cleaned with a Harrick PDC-32G for 15 minutes on a high setting to remove remaining photoresist. This resulted in arrays of round ZMW wells of 150 nm diameter and 2μm pitch. Each ZMW chip used in this study (n = 7) was visualized with SEM to confirm fabrication quality, diameter, and pitch (example in Fig. 1a).

Imaging Chamber Preparation

Cover glasses intended for photobleaching experiments via TIRFM and not ZMW fabrication were cleaned by successive sonication for 60 minutes in 2% Hellmanex (Hellma), HPLC-grade ethanol (Millipore Sigma) and 1 M KOH, with deionized water rinses between solution exchanges. Both cover glasses and ZMW chips were additionally plasma cleaned for 5 minutes prior to surface functionalization. For ZMWs, the Al layer was passivated by incubation in 2% poly(vinylphonic acid) (PVPA) (Polysciences) for 3 minutes 90°C, followed by rinsing with Milli-Q ultrapure water and drying with Ar gas38. A silicone-gasketed chamber was attached to each substrate to hold small volumes and reduce evaporation (SecureSeal Hybridization Chambers, Grace Bio-Labs,). Both cover glasses and ZMW chips were silanized overnight in 2 mg/mL biotin-PEG-silane (MW = 3400 g mol−1) and 10 mg/mL mPEG-silane (MW = 2000 g mol−1) (Laysan Bio Inc.) in HPLC-grade ethanol (Millipore Sigma) with 5% glacial acetic acid. Samples were rinsed thoroughly with HPLC-grade ethanol, Milli-Q ultrapure water, and dried with Ar gas. Samples were additionally incubated with 10 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA) in tris buffered saline (TBS: 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris HCl, pH = 7.9) for 30 minutes to ensure robust passivation.

Single-Molecule Imaging

Single-molecule fluorescence imaging was performed on an inverted microscope (Olympus, IX-71) with a high NA oil immersion objective (Olympus, 100X, 1.49 NA) and controlled by Metamorph software (Molecular Devices). Laser excitation at either 488 nm or 532 nm (Coherent, Sapphire LP) was fed into a single AOTF (Laser Launch) and guided into a single-mode fiber (Thorlabs). The beam was collimated with an achromatic lens (Thorlabs), passed through a quarter-wave plate (Thorlabs), and focused on the objective’s back aperture with another achromatic lens (Thorlabs). The power of each beam into the objective was measured at ~5.3 mW for 488 nm and 6.7 mW for 532 nm, and the spot size at the sample plane was approximately 50 μm in diameter. Excitation and emission were filtered using two different dichroic and filter cubes applied separately (Semrock Brightline, LF488-C-000, Cy3/Cy5-A-OMF for fcAMP) and imaged on a 512x512 EMCCD (Andor iXon Ultra X-888) at 10 Hz. This set-up enabled simultaneous recording of ~1,600 ZMWs at a time in an approximately 80x80 μm field of view (Extended Data Fig. 2a).

All single-molecule experiments were carried out in TBS supplemented with 1 mg/ml BSA, 100 μM GDN, and 5 mM DTT. Biotinylated cover glasses and ZMWs were sequentially incubated with 1 μM streptavidin (Prospec, cat # PRO-791) and 10 nM biotinylated GFP-TRAP (ChromoTek) for 10 minutes each. Purchased GFP-TRAP was provided at 1 mg/mL (MW = 13.9 kDa) and diluted to 10 nM in TBS prior to use (1:7200 dilution). GFP tagged HCN1SM/HCN2SM molecules were pulled down to the surface by incubation at either 5 pM (cover glasses) or 250 nM (ZMW) for 10 minutes then thoroughly rinsed to remove freely diffusing eGFP-HCN1/2 prior to imaging. The specificity of the GFP-TRAP for tethering HCN1SM and HCN2SM was confirmed using a non-specific binding assay (Extended Data Fig. 2a). The manufacturer reports a KD = 1 pM for GFP-TRAP/ GFP interaction. We did not observe any noticeable decrease in single-molecule spots over a typical imaging session (1-2 hours) indicating HCN1SM and HCN2SM remain surface tethered.

For binding experiments, TBS was first bubbled with Argon for 30 minutes (prior to BSA, DTT, or GDN addition), and further supplemented with 2 mM Trolox, 2.5 mM protocatechuic acid (PCA, Millipore Sigma), and various concentrations of 8-(2-[DY-547]-aminoethylthio) adenosine-3',5'-cyclic monophosphate (fcAMP; BioLog Cat. No. 109-001). Prior to 532 nm excitation, an additional 250 nM protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase from Pseudomonas sp. (PCD, Millipore Sigma) was added to complete the oxygen scavenging system. All solutions were replenished every 30 minutes to minimize evaporation and ensure the oxygen scavenging system was active. The specicity of fcAMP binding to surface tethered HCN1SM and HCN2SM was confirmed using a non-specific binding assay with 1 μM fcAMP in the absence of HCN1SM/HCN2SM and after the addition of 1 mM cAMP (Extended Data Fig. 2c, d). Proteins were sparsely deposited onto the array to reduce the probability of having more than one protein per ZMW. On average, 313 ± 188 ZMWS were occupied per field of view. Considering Poisson statistics for single-molecule deposition into ZMWs, the observed deposition rate (λ = 0.22) leads us to only anticipate ~2% of ZMWs per field of view to contain more than one protein.

All ligand-binding experiments used fcAMP, a fluorescent derivative of cAMP featuring a DY-547 fluorophore. This analog activates HCN2 channels with a similar efficiency to cAMP2,12. A co-localization paradigm was used to identify ZMWs featuring HCN molecules receptive to fcAMP binding. First, the array was excited with a 488 nm pump to identify ZMWs containing at least one HCN molecule. Excitation at 488nm was continued to photobleach the eGFP tags (114 ±87 s).

Single-Molecule Analysis

Single-molecule fluorescence time trajectories were extracted from tiff stacks saved by Metamorph (Molecular Devices) using MATLAB (Mathworks). Locations of single molecules were identified by eGFP emission. For each image stack, a binary image mask was created by averaging the first 100 images, removing background with a top-hat filter and thresholding. Identified locations with an area greater than 4-pixels and at least 5-pixel separation between all neighboring locations were considered a region of interest (ROI). ROI locations were refined using a 2D Gaussian to fit the local intensity height map on the averaged image. For co-location experiments of fcAMP binding using ZMWs, ROIs identified in the 488 nm channel (eGFP photobleaching steps) were linearly transformed to the 532 nm channel (fcAMP) followed by 2D Gaussian refinement. The time-dependent fluorescence at each ROI was obtained by projecting the average image intensity in a 7 x 7-pixel square centered around the ROI for each image of the stack. The first 50 frames (5 seconds) of each time series were removed to account for a fluorescence decay inside the ZMW upon initial illumination (see raw data in Extended Data Fig. 2d, 3, 4). No baseline, background, or drift corrections were applied to the trajectories. To assess if photobleaching was impacting our estimated kinetic parameters, we correlated the intensity of each isolated-B1 event with its dwell time for HCN1SM and HCN2SM across each fcAMP concentration (Extended Data Fig. 6, 7). Although excitation intensity varied across the field of view, we do not observe a correlation with binding kinetics which suggests photobleaching is not impacting our estimations of the kinetic parameters.

The divisive segmentation and clustering (DISC) algorithm was applied to each fcAMP binding trajectory for an unbiased detection of discrete states (number of ligands bound) and transitions36. States are identified in DISC using a top-down unsupervised clustering algorithm and transitions are determined using the Viterbi algorithm. All idealized traces were visually inspected following idealization. Traces featuring greater than five discrete states and/or low signal to noise ratios were removed from analysis. Single change-point detection was applied to truncate traces exhibiting an asynchronous decay of activity over time, a phenomenon previously observed in both bulk and single-molecule studies which may be caused by free oxygen radicals modifying CNBDs36,48. Minor heterogeneity in event fluorescence intensities is observed, likely deriving from dye photophysics, and is effectively handled by the DISC algorithm36. In total, our analysis includes 2.2 x 105 seconds (60 hours) of HCN1 activity across 739 molecules (1.8 x 105 events) at fcAMP concentrations between 0.1 to 0.9 μM, and 1.26 x 105 seconds (35 hours) of HCN2 activity across 444 molecules (8.2 x 104 events) at fcAMP concentrations between 0.1 to 1.5 μM (Supplementary Table 1). These results are drawn from different protein preparations (HCN1SM: n = 2, HCN2SM: n = 3) and collected across multiple ZMW chips (HCN1SM: n = 3, HCN2SM: n = 4). All statistical analysis was performed using MATLAB 2019b unless otherwise stated. Errors are reported as standard deviation (s.d.), standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) or 95% confidence intervals and are indicated in each caption. All analyses were additionally after removing single-frame (100-ms) events to account for missed events, blinking, diffusion, or noise (Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Table 7).

Maximum likelihood estimations of state occupancy distributions, photobleaching steps distributions, and dwell time distributions were all performed using custom scripts in MATLAB. For state occupancy distributions (Fig 2a, Extended Data Fig. 5, Supplementary Table 2), the total number of observed frames spent in each state across all molecules at given fcAMP concentration was treated as binomial distribution. Here, for 4 identical bindings sites, each with a probability (Pr) of ligand binding p, the probability of x binding sites being occupied simultaneously is

Distributions of photobleaching steps (Extended Data Fig. 1c, d) where treated as a zero-truncated binomial distribution to account for the inability to observe molecules wherein all subunits were photobleached prior to excitation. For 4 identical eGFP tags, each with a probability of being fluorescent P, the probability of observing x photobleaching steps is given by

Dwell time distributions of unbinned isolated-B1 events (Fig. 3, Extended Data Fig. 6, Extended Data Fig. 7, Supplementary Table 3) were treated as a mono- or biexponential distribution. The probability of observing a dwell time of duration x is given by

Where z is the number of exponentials being fit, A is the fitted amplitude where , and τ the fitted time constants. A loglikelihood-ratio test was performed for each dwell time distribution to compare the goodness-of-fit of single and double exponential distributions. The homogeneity of the estimated parameters within the full population of molecules was confirmed by an outlier analysis (Extended Data Fig. 8, Supplementary Methods). Dwell time distributions are visualized in two ways. First, dwell times are binned and plotted as histograms where the abscissa values correspond to the center of the bars. Second, isolated-B1 dwell times are additionally visualized as probability density function (PDF) plotted on a log scale to highlight the long-lived dwell times (see insets of Extended Data Fig. 3, Extended Data Fig. 6, and Extended Data Fig. 7). The PDF values are computed by dividing each bin by the product of the bin width and the total number of counts. Error bars for each bin were calculated as the error of binomial distribution, previously described elsewhere26.

HMM Analysis

HMM analysis of idealized datasets for HCN1SM and HCN2SM were performed with QuB42,43. The first and last event of each trajectory was removed prior to analysis to avoid interpretation of truncated events. Models were globally optimized to simultaneously describe the idealized binding events for all molecules across all fcAMP concentrations using maximum idealized point (MIP) likelihood rate estimation. The optimized transition rates returned by QuB are reported as mean ± s.e.m. The goodness of fit of each model was assessed by BIC44

where k is the number of free parameters in the model (Supplementary Table 4), n is the total number data points (frames) across all fcAMP concentrations (Supplementary Table 1), and LL is the loglikelihood by maximum idealized point (MIP) estimation in QuB42. The model with the lowest BIC value was considered the best fit (Supplementary Table 4). Optimized rates for all models are also in Supplementary Table 5. The data were additionally resampled to ensure homogeneity (Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Table 6).

Extended Data

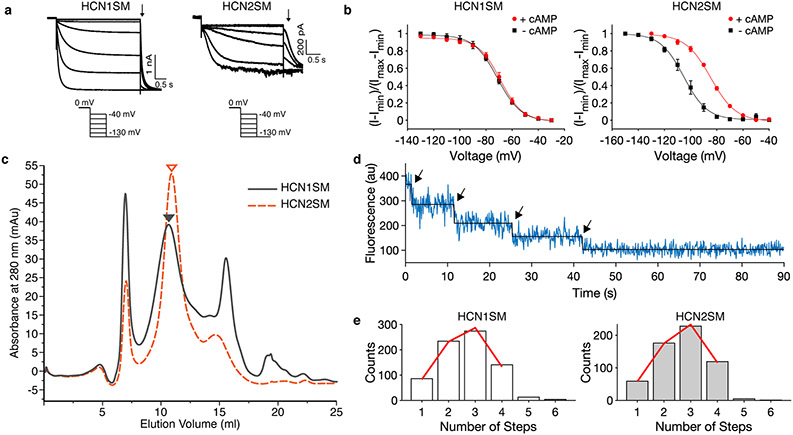

Extended Data Fig. 1: Characterization of HCN1SM and HCN2SM.

(a) Representative electrophysiological recordings (top) of HCN1SM (left) and HCN2SM (right) with voltage protocol. Tail currents (arrow) were collected at −130 mV and were used to generate the activation curves. (b) Normalized activation curves of HCN1SM (left) and HCN2SM (right) in the absence or presence of saturating concentrations (500 μM) of internal cAMP with a Boltzmann fit (red). Data points are mean ± s.e.m. (n = 5 patches). V1/2 values for are HCN1SM −71.2 ± 0.4 mV without cAMP and −69.1 ± 0.5 mV with cAMP. V1/2 values for are HCN2SM −105.2 ± 0.6 mV without cAMP and −84.6 ± 0.5 mV with cAMP). (c) Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) profiles of HCN1SM (grey) and HCN2SM (orange dashed). Triangles indicate the peak fraction (0.3 mL) used for single-molecule measurements. (d) Example fluorescence vs time trajectory of photobleaching eGFP-tagged HCN2SM tetramers via TIRFM. (e) Distributions of photobleaching steps overlaid with a maximum likelihood estimate of a zero-truncated binomial distribution (red) for a tetrameric complex with a probability (P) of observing eGFP (HCN1: P = 0.65, 95% CI [0.63, 0.67], n = 752; HCN1: P = 0.67, 95% CI [0.65, 0.69], n = 588).

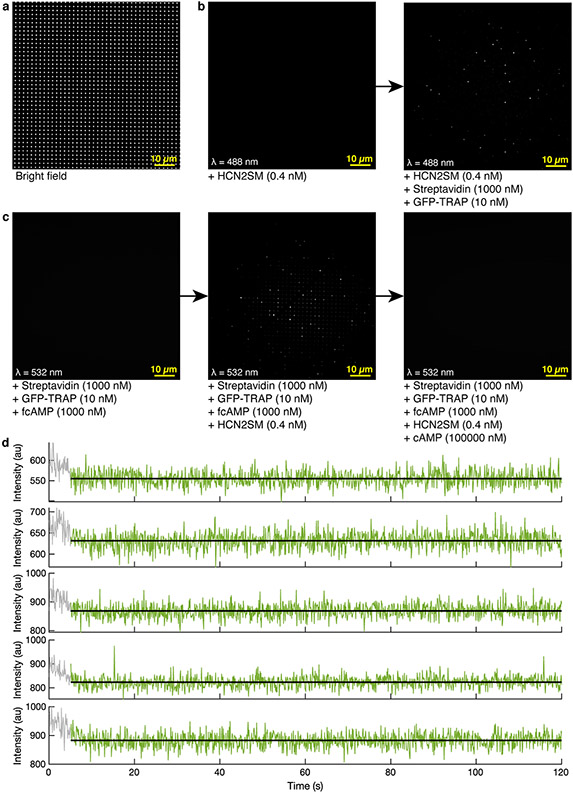

Extended Data Fig. 2: Non-specific binding in ZMWs.

(a) Bright field image of ZMW array on single-molecule imaging set-up featuring a 512x512 pixel EMCCD and a 100X objective. Each white dot (~1,600 per field of view) is a ZMW. Test of specific binding of eGFP-tagged HCN2SM to ZMWs (b) and of fcAMP (c) to HCN2SM in ZMWs. For b and c, all images shown are averaged over the first 10 frames (1 second) and background subtracted for visualization. Brightness and contrast were adjusted for clarity. (d) Representative and randomly selected fluorescence trajectories of empty (no HCN) and passivated ZMWs with 1000 nM fcAMP fit with DISC (black). The first 50 frames (grey) were removed from analysis.

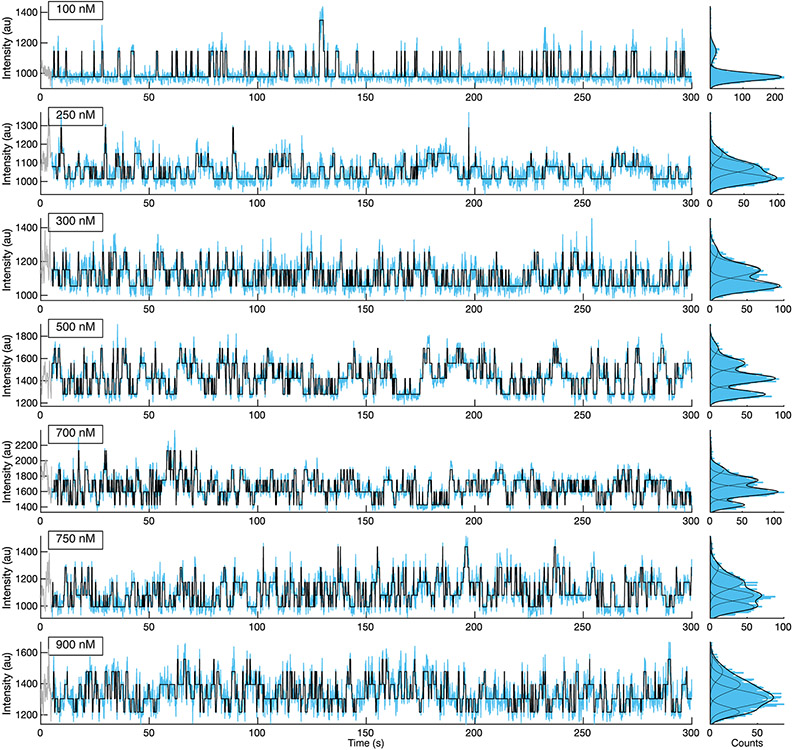

Extended Data Fig. 3: fcAMP binding to HCN1SM in ZMWs.

Representative fluorescence trajectories of fcAMP (100 nM to 900 nM) binding to HCN1SM in ZMWs with idealized fits (black) imaged at 100-ms resolution. The first 50 frames (grey) were removed from analysis.

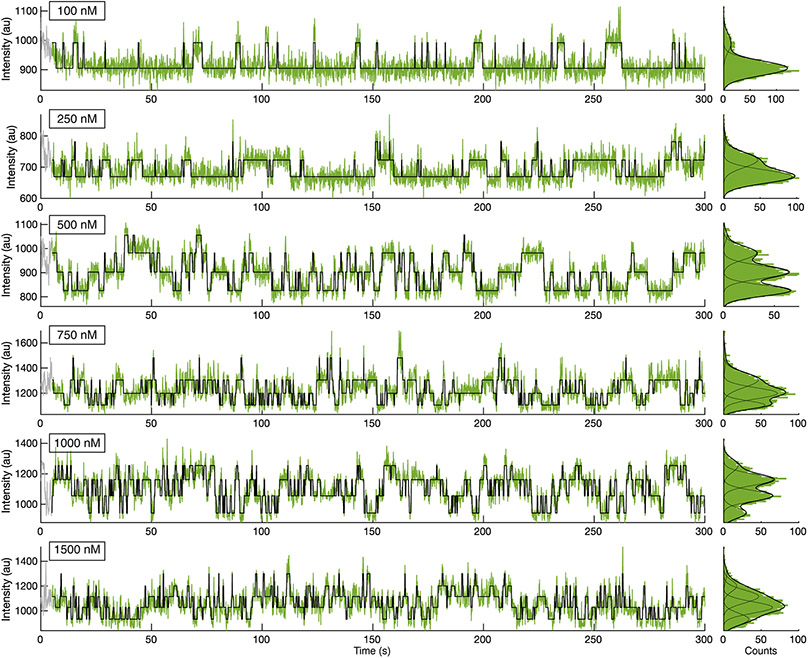

Extended Data Fig. 4: fcAMP binding to HCN2SM in ZMWs.

Representative fluorescence trajectories of fcAMP (100 nM to 1500 nM) binding to HCN2SM in ZMWs with idealized fits (black) imaged at 100-ms resolution. The first 50 frames (grey) were removed from analysis.

Extended Data Fig. 5: All state occupancy distributions:

Normalized state occupancy distributions for HCN1SM (a) and HCN2SM (b) across all recorded fcAMP concentrations. Each plot indicates the total number of molecules (n) and data points (i.e., frames, m) included in the analysis. P is the success rate of the optimized binomial distribution considering four binding sites. All obtained and expected state occupancies values are in Supplementary Table 2.

Extended Data Fig. 6: Isolated-B1 Events of HCN1SM.

(a) Dwell time distributions of isolated-B1 events for HCN1SM at various fcAMP concentrations overlaid with maximum likelihood estimates for monoexponential (blue dashed) and biexponential (red) distributions (Supplementary Table 3). For inset, error bars are the error of a binomial distribution (Methods). (b, c) Coordinates of identified single-molecules in the 512x512 pixel field of view superimposed across all ZMW arrays. The color bars denote the average dwell time (b) and fluorescence (c) of the isolated-B1 state for each molecule (n). (d) Correlation of fluorescence intensity and dwell times for each isolated-B1 event (m), where r is the Pearson correlation coefficient. Data are binned for visualization.

Extended Data Fig. 7: Isolated-B1 Events of HCN2SM.

(a) Dwell time distributions of isolated-B1 events for HCN2SM at various fcAMP concentrations overlaid with maximum likelihood estimates for monoexponential (blue dashed) and biexponential (red) distributions (Supplementary Table 3). For inset, error bars are the error of a binomial distribution (Methods). (b, c) Coordinates of identified single-molecules in the 512x512 pixel field of view superimposed across all ZMW arrays. The color bars denote the average dwell time (b) and fluorescence (c) of the isolated-B1 state for each molecule (n). (d) Correlation of fluorescence intensity and dwell times for each isolated-B1 event (m), where r is the Pearson correlation coefficient. Data are binned for visualization.

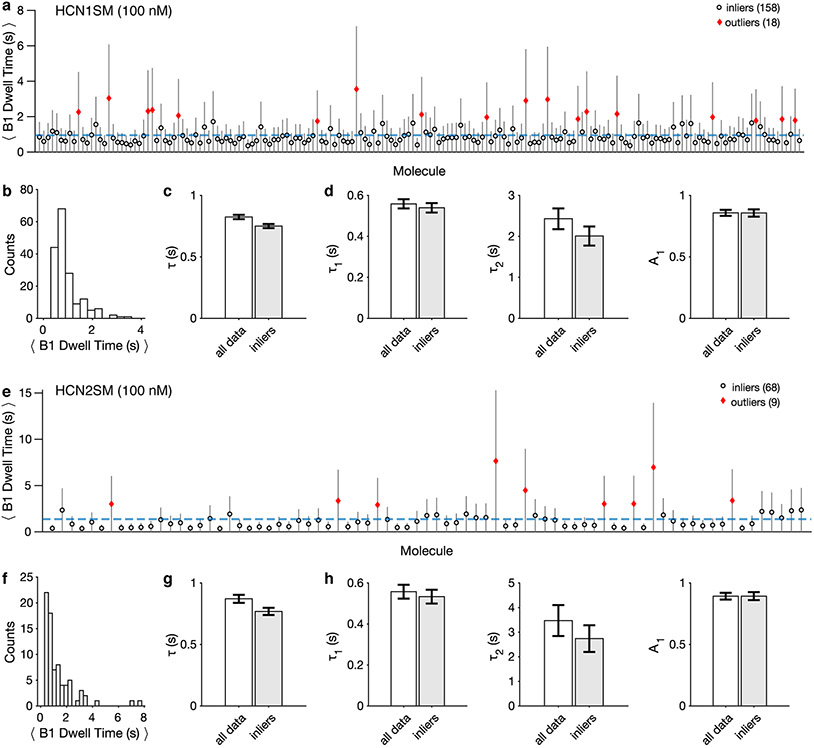

Extended Data Fig. 8: Isolated-B1 events do no exhibit static heterogeneity.

(a, e) Average isolated-B1 dwell time of HCN1SM (a) and HCN2SM (e) for each molecule at 100 nM fcAMP. Outliers (diamonds) were identified by three scaled median absolute deviations. Data plotted as mean ± s.d. of exponential distribution. The blue dashed line indicates the average B1 dwell time across all molecules (HCN1SM: n = 176; HCN2SM: n = 77). (b, f) Histograms of average isolated-B1 dwell times for each HCN1SM (b) and HCN2SM (f) molecule. c, g) Parameters for a monoexponential fit (τ) to isolated-B1 dwell times of HCN1SM (c) and HCN2SM (g). (d, h) Parameters for a biexponential fit (τ1, τ2, A1) to isolated-B1 dwell times of HCN1SM (d) and HCN2SM (h). For c, g, d, h the ordinate corresponds to the obtained parameter (τ, τ1, τ2, A1) and error bars are 95% confidence intervals. All parameters were obtained using maximum likelihood estimates across all isolated-B1 events in either all data (HCN1SM: n = 8229; HCN2SM: n = 2676) or inlier (HCN1SM: n = 7816; HCN2SM: n = 2575) groups, as indicated on the abscissa.

Extended Data Fig. 9: HCN1SM dwell time distributions.

Dwell time distributions of all liganded states of HCN1SM across all fcAMP concentrations overlaid with expectations from the optimized rates in Fig. 4b.

Extended Data Fig. 10: HCN2SM dwell time distributions.

Dwell time distributions of all liganded states of HCN2SM across all fcAMP concentrations overlaid with expectations from the optimized rates from in Fig. 4b.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the NIH grants to B.C. (NS-116850, NS-101723, and NS-081293), D.S.W (T32 fellowship GM007507) and NSF to R.H.G. (CHE-1856518). We thank Kassandra A. Knapper and Cecilia H. Vollbrecht for assistance with cover glass cleaning at the Wisconsin Centers for Nanoscale Technologies. We thank Marcel P. Goldschen-Ohm and Mackinsey Smith for helpful discussions. We also thank Meyer Jackson for sparking this collaboration. ZMWs were fabricated at the Center for Nanophase Materials Sciences at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, which is a DOE Office of Science User Facility.

Footnotes

CODE AVAILABILITY

The DISCO software package is available at https://github.com/ChandaLab/DISC and fully described elsewhere36. All additional MATLAB scripts for single-molecule analysis and image processing are available upon reasonable request.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All experimental data are available upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wahl-Schott C & Biel M HCN channels: Structure, cellular regulation and physiological function. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 66, 470–494, doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8525-0 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kusch J et al. How subunits cooperate in cAMP-induced activation of homotetrameric HCN2 channels. Nat Chem Biol 8, 162–169, doi: 10.1038/nchembio.747 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thon S, Schulz E, Kusch J & Benndorf K Conformational Flip of Nonactivated HCN2 Channel Subunits Evoked by Cyclic Nucleotides. Biophys J 109, 2268–2276, doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.08.054 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levene MJ et al. Zero-mode waveguides for single-molecule analysis at high concentrations. Science 299, 682–686, doi: 10.1126/science.1079700 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wainger BJ, DeGennaro M, Santoro B, Siegelbaum SA & Tibbs GR Molecular mechanism of cAMP modulation of HCN pacemaker channels. Nature 411, 805–810, doi: 10.1038/35081088 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lape R, Colquhoun D & Sivilotti LG On the nature of partial agonism in the nicotinic receptor superfamily. Nature 454, 722–U756, doi: 10.1038/nature07139 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jadey S & Auerbach A An integrated catch-and-hold mechanism activates nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Journal of General Physiology 140, 17–28, doi: 10.1085/jgp.201210801 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abele R, Keinanen K & Madden DR Agonist-induced isomerization in a glutamate receptor ligand-binding domain - A kinetic and mutagenetic analysis. Journal of Biological Chemistry 275, 21355–21363, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909883199 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng Q, Du M, Ramanoudjame G & Jayaraman V Evolution of glutamate interactions during binding to a glutamate receptor. Nature Chemical Biology 1, 329–332, doi: 10.1038/nchembio738 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiFrancesco D The Role of the Funny Current in Pacemaker Activity. Circulation Research 106, 434–446, doi: 10.1161/circresaha.109.208041 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Difrancesco D & Tortora P Direct activation of cardiac pacemaker channels by intraceullar cyclic AMP. Nature 351, 145–147, doi: 10.1038/351145a0 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kusch J et al. Interdependence of Receptor Activation and Ligand Binding in HCN2 Pacemaker Channels. Neuron 67, 75–85, doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.05.022 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chow SS, Van Petegem F & Accili EA Energetics of cyclic AMP binding to HCN channel C terminus reveal negative cooperativity. J Biol Chem 287, 600–606, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.269563 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hines KE, Middendorf TR & Aldrich RW Determination of parameter identifiability in nonlinear biophysical models: A Bayesian approach. Journal of General Physiology 143, 401–416, doi: 10.1085/jgp.201311116 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wyman J The Binding Potential, a Neglected Linkage Concept. J Mol Biol 11, 631–644, doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(65)80017-1 (1965). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sigg D A linkage analysis toolkit for studying allosteric networks in ion channels. J Gen Physiol 141, 29–60, doi: 10.1085/jgp.201210859 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chowdhury S & Chanda B Free-energy relationships in ion channels activated by voltage and ligand. Journal of General Physiology 141, 11–28, doi: 10.1085/jgp.201210860 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chowdhury S & Chanda B Estimating the voltage-dependent free energy change of ion channels using the median voltage for activation. J Gen Physiol 139, 3–17, doi: 10.1085/jgp.201110722 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vafabakhsh R, Levitz J & Isacoff EY Conformational dynamics of a class C G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature 524, 497–501, doi: 10.1038/nature14679 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gregorio GG et al. Single-molecule analysis of ligand efficacy in beta2AR-G-protein activation. Nature 547, 68–73, doi: 10.1038/nature22354 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liauw BW, Afsari HS & Vafabakhsh R Conformational rearrangement during activation of a metabotropic glutamate receptor. Nat Chem Biol, doi: 10.1038/s41589-020-00702-5 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y et al. Single molecule FRET reveals pore size and opening mechanism of a mechano-sensitive ion channel. Elife 3, doi: 10.7554/eLife.01834 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dolino DM et al. The structure-energy landscape of NMDA receptor gating. Nature Chemical Biology 13, 1232–1238, doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2487 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang SZ, Vafabakhsh R, Borschell WF, Ha T & Nichols CG Structural dynamics of potassium-channel gating revealed by single-molecule FRET. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 23, 31–36, doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3138 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang Y et al. Sensing cooperativity in ATP hydrolysis for single multisubunit enzymes in solution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 16962–16967, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112244108 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoskins AA et al. Ordered and dynamic assembly of single spliceosomes. Science 331, 1289–1295, doi: 10.1126/science.1198830 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holzmeister P, Acuna GP, Grohmann D & Tinnefeld P Breaking the concentration limit of optical single-molecule detection. Chemical Society Reviews 43, 1014–1028, doi: 10.1039/c3cs60207a (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu JY, Stone MD & Zhuang X A single-molecule assay for telomerase structure-function analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 38, e16, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1033 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morse JC et al. Elongation factor-Tu can repetitively engage aminoacyl-tRNA within the ribosome during the proofreading stage of tRNA selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117, 3610–3620, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1904469117 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zheng J & Trudeau MC Handbook of ion channels. (CRC Press, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu P & Craighead HG in Annual Review of Biophysics, Vol 41 Vol. 41 Annual Review of Biophysics (ed Rees DC) 269–293 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldschen-Ohm MP et al. Structure and dynamics underlying elementary ligand binding events in human pacemaking channels. Elife 5, doi: 10.7554/eLife.20797 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uemura S et al. Real-time tRNA transit on single translating ribosomes at codon resolution. Nature 464, 1012–U1073, doi: 10.1038/nature08925 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eid J et al. Real-Time DNA Sequencing from Single Polymerase Molecules. Science 323, 133–138, doi: 10.1126/science.1162986 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldschen-Ohm MP, White DS, Klenchin VA, Chanda B & Goldsmith RH Observing Single-Molecule Dynamics at Millimolar Concentrations. Angewandte Chemie-International Edition 56, 2399–2402, doi: 10.1002/anie.201612050 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.White DS, Goldschen-Ohm MP, Goldsmith RH & Chanda B Top-down machine learning approach for high-throughput single-molecule analysis. Elife 9, doi: 10.7554/eLife.53357 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang J, Chen S & Siegelbaum SA Regulation of hyperpolarization-activated HCN channel gating and cAMP modulation due to interactions of COOH terminus and core transmembrane regions. Journal of General Physiology 118, 237–250, doi: 10.1085/jgp.118.3.237 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Korlach J et al. Selective aluminum passivation for targeted immobilization of single DNA polymerase molecules in zero-mode waveguide nanostructures. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105, 1176–1181, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710982105 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ding S & Sachs F Evidence for non-independent gating of P2X 2 receptors expressed in Xenopusoocytes. BMC neuroscience 3, 17 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Collauto A et al. Rates and equilibrium constants of the ligand-induced conformational transition of an HCN ion channel protein domain determined by DEER spectroscopy. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 19, 15324–15334, doi: 10.1039/c7cp01925d (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zagotta WN et al. Structural basis for modulation and agonist specificity of HCN pacemaker channels. Nature 425, 200–205, doi: 10.1038/nature01922 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qin F, Auerbach A & Sachs F A direct optimization approach to hidden Markov modeling for single channel kinetics. Biophysical Journal 79, 1915–1927, doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(00)76441-1 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nicolai C & Sachs F Solving ion channel kinetics with the QuB software. Biophysical Reviews and Letters 8, 191–211 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwarz G ESTIMATING DIMENSION OF A MODEL. Annals of Statistics 6, 461–464, doi: 10.1214/aos/1176344136 (1978). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lolicato M et al. Tetramerization Dynamics of C-terminal Domain Underlies Isoform-specific cAMP Gating in Hyperpolarization-activated Cyclic Nucleotide-gated Channels. Journal of Biological Chemistry 286, 44811–44820, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.297606 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee CH & MacKinnon R Structures of the Human HCN1 Hyperpolarization-Activated Channel. Cell 168, 111–120, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.023 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goehring A et al. Screening and large-scale expression of membrane proteins in mammalian cells for structural studies. Nature Protocols 9, 2574–2585, doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.173 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Idikuda V et al. Singlet oxygen modification abolishes voltage-dependent inactivation of the sea urchin spHCN channel. Journal of General Physiology 150, 1273–1286, doi: 10.1085/jgp.201711961 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All experimental data are available upon reasonable request.