Abstract

Background:

There is growing evidence of disparities in access to hospice and palliative care services to varying degrees by sociodemographic groups. Underlying factors contributing to access issues have received little systematic attention.

Objective:

To synthesize current literature on disparities in access to hospice and palliative care, highlight the range of sociodemographic groups affected by these inequities, characterize the domains of access addressed, and outline implications for research, policy, and clinical practice.

Design:

An integrative review comprised a systematic search of PubMed, Embase, and CINAHL databases, which was conducted from inception to March 2020 for studies outlining disparities in hospice and palliative care access in the United States. Data were analyzed using critical synthesis within the context of a health care accessibility conceptual framework. Included studies were appraised on methodological quality and quality of reporting.

Results:

Of the articles included, 80% employed non-experimental study designs. Study measures varied, but 70% of studies described differences in outcomes by race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status. Others revealed disparate access based on variables such as age, gender, and geographic location. Overall synthesis highlighted evidence of disparities spanning 5 domains of access: Approachability, Acceptability, Availability, Affordability, and Appropriateness; 60% of studies primarily emphasized Acceptability, Affordability, and Appropriateness.

Conclusions:

This integrative review highlights the need to consider various stakeholder perspectives and attitudes at the individual, provider, and system levels going forward, to target and address access issues spanning all domains.

Keywords: healthcare disparities, health services accessibility, palliative care, hospices, review

Introduction

Approximately 12 million adults and 400,000 children are living with a serious illness in the United States.1 There has been increased demand for hospice and palliative care in recent years, particularly as the number of older adults living with a chronic condition(s) is expected to reach 78 million by 2035.1,2 Both hospice and palliative care involve a multidisciplinary approach and philosophy of care that prioritizes quality of life for patients and families experiencing symptoms related to serious illness.3 The evidence base for hospice and palliative care has grown, demonstrating the benefits for improving quality of life, reducing aggressive medical intervention, and easing economic burden by minimizing hospitalizations and utilization of the intensive care unit (ICU) at the end of life.1,2 However, it is projected more than 60% of Americans die without hospice services annually,4 and only 17% of hospitals with 50 beds or more in rural communities have palliative care available.1 Despite substantial increases in the number of hospice and palliative care programs across the U.S., it is clear needs and expectations are not being met equitably for all patients.

Health care disparities are widely documented across the health care sector and differences in access to care, quality of care, and health outcomes persist across demographic groups.5 Most commonly noted are disparities among socially and economically disadvantaged groups of people, such as Blacks, Hispanics, and Native Americans (American Indian/Alaska Native), when compared to non-Hispanic Whites.6 Lack of communication regarding values and preferences can lead to more aggressive intervention for unmet needs and unresolved symptoms, increased hospital stays, and greater financial burden on families at the end of life.7,8 Additionally, socioeconomic status, including household income, insurance status, education, and health literacy, which are often linked with race, have been associated with higher intensity end-of-life care and decreased palliative care engagement.8 Notably, end-of-life care was developed from a traditional Western perspective, and yet many studies attempt to derive generalized conclusions despite lacking adequate racial and ethnic representation in research studies.9,10 This tendency has significant implications in that it preserves adverse stereotypes of many specific groups, which can lead to greater provider bias in care delivery.3 Furthermore, existing metrics of assessment lack potential for intersectionality, perpetuating traditional perspectives regarding application of hospice and palliative care.11,12 Very few studies have outlined interventions or recommendations for mitigating inequities in access for those individuals “situated on lower rungs of social hierarchies of power,” such as individuals with low-income or without a permanent residence.7,11 Health is a fundamental right, and as such, research, policy, and clinical practice must remediate health disparities from a position of equity and social justice.3,13 To do so, the distribution of structural barriers and challenges faced by a particular group must first be identified and understood. Therefore, the evidence gathered in this review may be useful for researchers and providers to tailor care based on individual patient needs and will serve as a foundation for design of targeted interventions to reduce disparities in hospice and palliative care access going forward.

Methods

Health Care Accessibility Conceptual Framework

Levesque et al. (2013) developed a conceptual framework which provides a dynamic and cumulative perspective on access to health care.14 It displays the congruence between five domains of access: Approachability, Acceptability, Availability, Affordability, and Appropriateness, and corresponding abilities of persons to access and engage in services. By using this conceptual framework to synthesize the literature, we can evaluate access issues from a socio-ecological vantage point, giving greater context to demographic disparities uncovered in current research and gain a holistic understanding of the overall state of the science.

Design

Using an integrative review approach and guided by principles of a mixed research synthesis, a systematic search was conducted of published quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods research.15,16 The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were used for reporting and presentation of information throughout the review.17

Search Strategy

Following consultation with a biomedical library scientist, a search strategy and search terms were developed. Searches were conducted through the PubMed, CINAHL, and Embase databases. Indexed terms and key words and/or phrases were used to acquire articles relating to disparities in access to hospice or palliative care for adults in the United States. Search terms were formed per the indexing requirements of each database but included the following key terms: “palliative care,” “hospice and palliative nursing,” “health care access,” and “health care disparities.” Table 1 details the full search strategy used. Iterative searches were performed from December 2019 through March 2020 for topic relevance.

Table 1.

Search Strategy.

| PubMed | • ((("Health Services Accessibility"[Mesh] OR "access to health care" OR "health care access")) AND (("Healthcare Disparities"[Mesh] OR "Health Status Disparities"[Mesh] OR disparit* [tiab] OR disparat* [tiab]))) AND ("Palliative Care"[Mesh] OR "Hospice and Palliative Care Nursing"[Mesh] OR "Palliative Medicine"[Mesh] OR palliative [tiab]) |

| Embase | • (‘palliative nursing’/exp OR ‘palliative therapy’/exp OR palliative:ti,ab) AND (‘health care access’/exp OR ((‘health care’ NEAR/3 access*):ti,ab)) AND (‘disparities’/exp OR ‘health disparity’/exp OR ‘health care disparity’/exp OR disparit*:ti,ab OR disparat*:ti,ab) |

| CINAHL | • (MH "Healthcare Disparities") OR (disparit* OR disparat*) AND (MH "Health Services Accessibility+") OR ("health care" N3 access*) AND (MH "Hospice and Palliative Nursing") OR (MH "Palliative Care")) OR palliative |

Study Selection

Studies were selected for this review based upon inclusion and exclusion criteria determined a priori. The following inclusion criteria were applied to each article: 1) the study highlighted any of the framework’s five domains of access within the context of hospice or palliative care, 2) the study outcomes identified disparities in access across a particular demographic group, and 3) the article was published between 2010 and 2020 within the United States. Studies focused on pediatric populations, non-English articles, abstracts, dissertations, and editorials were excluded.

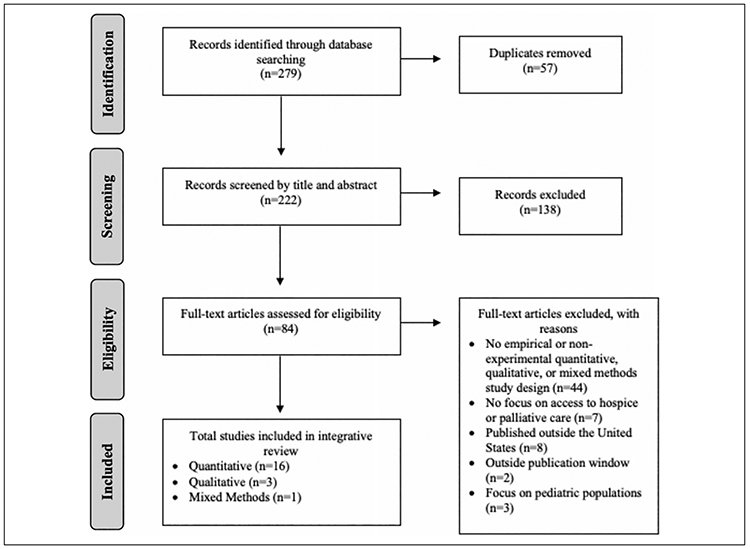

The primary author (KN) used a structured procedure to identify relevant articles (Figure 1) via Covidence, an online software program which enhances organization and sorting of studies. Each included article was verified for coherence with inclusion and exclusion criteria by a second reviewer (AP). In the case of disagreement, consensus was reached through subsequent discussion. Articles were initially screened by title and abstract, and remaining articles were vetted for full-text relevance. If full-text articles were excluded, the primary inclusion criteria “not satisfied” was noted.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Diagram.

Quality Appraisal

KN and AP independently appraised the quality of included studies to mitigate reporting bias. All studies were systematically appraised using the Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Rating Scale.18 The scale provides a systematic rating based on evaluation of the type of evidence (I-V) and the quality of study results (A—High quality, B—Good quality, C—Low quality or major flaws).18

Results

Selected Studies

The initial search returned 279 articles. After removing duplicates, 222 article titles and abstracts were screened for relevance using the defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Following initial screening, 84 articles were chosen for full-text review, and 20 articles were selected for data extraction. AP verified all included studies met inclusion and exclusion criteria. Table 2 shows data extracted from all studies, including: sample size and population, sociodemographic profile of participants, end-of-life related outcome measures, dimensions of access noted, key findings, and disparities in access highlighted by demographic group.

Table 2.

Summary of Synthesized Studies and Key Findings.

| Author (Year) | Study design (evidence quality) |

Population delineation (sample size) |

Socio-demographic profile of participants |

End-of-life related measures |

Elements of access addressed |

Access disparities identified by demographic |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approachability | Acceptability | Availability | Affordability | Appropriateness | Key findings | Age | Sex/ Gender |

Race/ Ethnicity |

Education | SES/ Insurance |

Disease/ Severity |

Other | |||||

| Quantitative Studies | |||||||||||||||||

| Andrews, et al (2014)19 | Cross-sectional (III, C) | – Young muscular dystrophy patients (2) – Family caregivers (32) |

– 28% Hispanic caregivers – 6% of caregivers spoke better Spanish than English – 88% female caregivers |

– Disease severity – Service utilization |

– | – | – | ✓ | ✓ | – Disease severity, per capita income, family history associated with service utilization – Race/ethnicity and level of acculturation not significantly associated with service utilization |

– | – | – | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Brown, et al (2018)8 | Retrospective cohort analysis (III, B) | – Patients who died from chronic illness (22,068) | – 82% White, 6% Asian, 6% Black, 2% Hispanic, 2% Native American – 57% Male, 43% Female – 27% had a 4-year college education or higher |

*Within the last 30 days of life: – Intensive care unit admission – Use of mechanical ventilation – Receipt of CPR |

– | – | – | ✓ | ✓ | – Race/ethnicity, SES, and lower income significantly associated with all 3 types of high-intensity care in last 30 days of life – Lower levels of education significantly associated with mechanical ventilation and ICU care in last 30 days of life – Racial/ethnic minority groups more likely to be admitted to ICU and receive mechanical ventilation than white non-Hispanics |

– | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | – |

| Gidwani-Marszowski, et al (2018)20 | Retrospective cohort analysis (III, C) | – Veteran patients who died of solid tumors (87,251) | – 87% White – 99% Male – 52% Medicare-reliant, 46% VA-reliant |

*Within the last 30 days of life: – Quality of care – Chemotherapy use – Intensive care unit/hospital admission or death in the hospital – Number of days in the hospital |

– | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – Medicare-reliant patients had more intensive (lower quality) EOL care than VA-reliant patients in terms of chemotherapy, hospital and ICU admissions, number of days in the hospital and death in the hospital – Race, urbanicity associated with more ED visits and hospitalizations |

– | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ✓ |

| Givens, et al (2010)21 | Retrospective cohort analysis (III, B) | Heart failure patients (98,258) | – 88% White, 9% Black, 1% Hispanic – 39% Male – 76% had median income <$45,000 |

– Hospice entry | – | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | – Blacks/Hispanics used hospice less for any diagnosis than Whites after adjusting for income, illness severity, and urbanicity – For heart failure, Hispanics had longest median duration (19 days), followed by Blacks (14 days), and Whites (13 days) – Comorbidity burden, advanced age, ED visits/hospitalizations, and local hospice density significantly associated with hospice utilization |

✓ | – | ✓ | – | – | ✓ | ✓ |

| Haines, et al (2018)22 | Retrospective analysis (III, B) | Adult trauma patients (2,966,444) | *Among those discharged to hospice: – 89% White – 52% Female – 71% Medicare reliant |

– Disposition to hospice – Hospital LOS |

– | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | – Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians significantly less likely to receive hospice than Whites – Age, gender, and type of disease significantly associated with disposition to hospice – Medicare patients transferred to hospice sooner than uninsured patients who had longer hospital LOS |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | – |

| Hoerger, et al (2019)23 | Descriptive (III, B) | States (50) | *At the state-level, on average: – 69% White – 50.6% Female – $56,406 Median income |

– PC access – Personality (Openness) |

– | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | – Greater PC access in states where residents were older, White, had higher SES, and were politically liberal – States with higher levels of openness had greater PC access |

✓ | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ✓ |

| Hui, et al (2012)24 | Retrospective case-control (III, B) | Patients who died of advanced cancer (816) | *Of patients who had a PC referral: – 58% White, 22% Black, 14% Hispanic, 5% Asian, 1% Other – 53% Female – 64% had a college education or higher |

– PC consults and referrals | – | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – Patients with PC consults were younger, female, and more likely to be married – Patients with GYN, breast, and GI cancers were more likely to have PC access – Majority of patients had an average of 20 medical team encounters prior to PC referral and/or did not see PC at all before death |

✓ | ✓ | – | – | – | ✓ | ✓ |

| Kumar, et al (2012)25 | Cross-sectional (III, B) | Cancer patients (313) | – 77% White, 18% Black, 2% Asian, 2% Hispanic, 1% Native American – 72% had a college education or higher |

– Use of SPCS (counseling, cancer support group, cancer rehabilitation, and PC consult) | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – Most commonly used SPCS was counseling (30%); least common were PC consultation (8%) and cancer rehabilitation (4%) – SPCS users were more likely to be female and have a higher level of education – Type of cancer was significantly associated with SPCS use |

– | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | – |

| Lee, et al (2013)26 | Descriptive (III, C) | Pancreatic cancer patients (1,008) | – 15% Black – 65.3% Male |

– Surgery and adjuvant therapy use for locoregional disease – Chemotherapy use for distant disease |

– | – | – | – | ✓ | – Race was not significantly associated with surgical resection, adjuvant therapy/chemotherapy use – Severity of disease was significantly associated with surgical outcomes |

– | – | – | – | – | ✓ | – |

| Okafor, et al (2016)27 | Retrospective analysis (III, B) | Patients with metastatic malignancies of the colon (217,055) | *Among White patients: – 48% Female – 58% Medicare reliant; 6% Medicaid reliant *Among Black patients: – 40% Female – 54% Medicare reliant; 21% Medicaid reliant |

– Colorectal stent utilization – Hospital LOS |

– | – | – | ✓ | – | – Medicare was the most common payer for the procedures across all races; Blacks incurred the highest average total charges ($156,876) – Higher SES was significantly associated with greater utilization – Lower SES was significantly associated with greater hospital LOS and charges |

– | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ✓ |

| Sharma, et al (2015)28 | Retrospective analysis (III, B) | Metastatic cancer patients (6,288) | – 69% White, 19% Black, 6% Hispanic, 7% Other *Of patients reliant on Medicaid: – 20% Hispanic, 17% Black, 3% White |

– Receipt of inpatient PC consultation | – | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | – Black/lower SES patients were significantly more likely than Whites to have an inpatient PC consult and to be referred to hospice – Advanced illness and increased frequency of hospitalizations were significantly associated with greater odds of having an inpatient PC consult |

– | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | – |

| Silveira, et al (2011)29 | Observational (III, B) | U.S. counties (3,140) | *At the county level, on average: – 9% Black, 6% Hispanic – 51% had a high-school education |

– Hospice program availability | – | – | ✓ | ✓ | – | – Hospice availability was significantly associated with urbanicity – Population size, median household income, race, and certificate of need – positively predicted hospice count per county – Area, ethnicity, education, and age negatively predicted hospice count per county |

✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ |

| Singh, et al (2017)30 | Retrospective observational (III, B) | Stroke patients (395,411) | – 69% White – 52% Female *Of patients who had a PC encounter – 7% White, 5% Hispanic, 4% Black |

– PC encounter – Death during hospitalization |

– | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – Age, sex, and race were significantly associated with PC use – PC encounters were significantly associated with large, urban teaching, and non-profit hospitals |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | – | ✓ |

| Stewart, et al (2016)31 | Descriptive (III, B) | Hepatocellular cancer patients (33,270) | – 38% White, 26% Hispanic, 8% Chinese, 8% Black, 6% Vietnamese, 4% Filipino, 3% Korean, 1% American Indian/Alaska Native | – Receipt of surgical treatment – Cause-specific and all-cause mortality |

– | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | – Age, race, gender, and SES were significantly associated with odds of receiving surgical treatment – Lower mortality was significantly associated with younger age, female gender, earlier stage disease, higher SES, and later time period of diagnosis |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | – |

| Watanabe-Galloway, et al (2014)32 | Descriptive (III, B) | Patients who died from colorectal cancer (34,975) | *Non-Hispanic White: – 91% of rural beneficiaries, 91% of micropolitan beneficiaries, and 83% of metropolitan beneficiaries *Female sex: – 52% of rural beneficiaries, 51% of micropolitan beneficiaries, and 53% of metropolitan beneficiaries |

– ER visits, inpatient hospital admissions, and number of ICU days in the last 3 months of life – Proportion of people who used hospice – Proportion of people who enrolled in hospice less than 3 days before death, among those who ever used hospice |

– | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – Older age and female sex were significantly associated with fewer ER visits and hospitalizations, greater hospice use – Race/ethnicity, lower SES, and rurality were significantly associated with less hospice use, greater use of ED, inpatient care, and ICU in last 3 months of life |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | ✓ |

| Worster, et al (2018)33 | Retrospective analysis (III, C) | Patients referred to PC services (3,207) | – 65% White, 27% Black, 3% Hispanic, 3% Asian/Pacific Islander, 1% Other – 52% Female |

– Time to inpatient PC consult – Disposition to hospice – Hospital LOS |

– | ✓ | – | – | ✓ | – Race was not a significant – predictor of time to PC consult, hospice enrollment, or increased hospital LOS |

– | – | – | – | – | ✓ | – |

| Qualitative Studies | |||||||||||||||||

| Isaacson, et al (2015)34 | Qualitative (III, B) | Health Care Providers (7) | – 57% Native American/Alaska Indian, 43% non-Native | – Perspectives on PC specific to Native Americans – Availability of PC on reservations |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | – Cited lack of funding, and infrastructure as main challenges for implementing PC widely – Both Native and non-Native providers noted misconceptions regarding PC/hospice as a barrier to patient engagement |

– | – | – | – | – | – | ✓ |

| Johnston, et al (2019)35 | Qualitative (III, B) | Multiple stakeholders (Patients, caregivers, providers, CHWs) (24) | – 13% Black patients – 4% caregivers – 46% providers – 13% CHWs |

– Views and attitudes toward patient navigation and PC use for Blacks with advanced malignancies | ✓ | ✓ | – | – | ✓ | – Stated CHWs help bridge barriers in PC to enhance patient-centered care in a culturally sensitive manner – Inconsistent messaging and branding is a significant barrier to PC use |

– | – | ✓ | – | – | – | ✓ |

| Kavalieratos, et al (2014)36 | Qualitative (III, B) | Primary care, cardiology, and palliative care providers (18) | – 67% Physicians – 33% Non-physician providers |

– Perceived factors that impede PC referral and access for heart failure patients | – | – | ✓ | – | – | – Unpredictable trajectory of heart failure can prevent patients from seeking out PC services – Providers had limited knowledge regarding PC and its use in heart failure |

– | – | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | – |

| Mixed Methods Study | |||||||||||||||||

| Periyakoil, et al (2016)37 | Mixed- methods (III, A) | Patients and families (387) | – 37% White, 51% Asian American, 12% Black – 67% Female – 64% had a college education or higher |

– Barriers to quality EOL care | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | – 61% reported barriers to EOL care for persons in their culture/ethnicity – Common barriers noted were finances, communication, and beliefs – Patients with no formal education found financial challenges most difficult, followed by communication barriers between doctors and patients |

✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | – | ✓ |

CPR = Cardiopulmonary resuscitation; PC = Palliative Care; LOS = Length of stay; CHW = Community health worker; EOL = End of life; SPCS = Supportive and palliative care services.

Study and Sample Characteristics

Of the studies included in this review (N = 20), 16 were quantitative studies,8,19-33 3 qualitative studies,34-36 and 1 mixed-methods study.37 All quantitative studies involved non-experimental designs (cross-sectional, observational, and correlational designs). Samples were primarily drawn from U.S. datasets20-23,26,27,29-32 and electronic medical records,8,24,28,33 rendering high variability in sample sizes (range: 2–2,966,444). Average sample size for qualitative studies was 16 participants (range: 7–24).

The majority of studies (14) included patients exclusively.8,20-22,24-28,30-33,37 Remaining studies included patients and caregivers,19 providers,34,36 patients, caregivers, and providers,35 and state-level data, that is, U.S. states or counties.23,29 Race and ethnicity demographics were rather homogenous across studies, with majority of participants being White or Caucasian, consistent with existing literature. Marginalized populations represented were most commonly Black, and Hispanic to a lesser extent. Singh and colleagues (2017) specifically targeted a variety of Asian ethnicities.30 Only one study focused exclusively on hospice and palliative care for Native Americans.34 Socioeconomic status was primarily accounted for via measures of insurance status,20,21 household income,23,29 or health care expenditures.27

Service utilization was the most commonly measured primary outcome represented in 35% (7) of studies.19,23-25,28,30,33 Utilization is often used as a proxy measure for health care access.15 Of these studies, utilization was delineated as any referral, consult, or encounter for palliative care, hospice, or other supportive care services. Other end-of-life related measures, primary or secondary, included receipt of aggressive medical intervention (such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation or chemotherapy) (5)8,20,26,27,31 disposition to hospice (4),21,22,32,33 hospitalizations (including emergency department visits or ICU admissions) (4),8,22,32,33 palliative care or hospice program availability (2),23,29 and death (2).30,31

Domains of Access

Studies were characterized using the health care accessibility conceptual framework,15 and identified challenges and barriers were conceptualized within each of the five domains (Table 3). Of the five domains influencing health care access, 60% (12) of studies emphasized Acceptability,21-25,30-35,37 Affordability,8,19-23,25,27,29,31,32,34,37 and Appropriateness of services.8,19,20,22,24,26,28,30-33,35 Availability was highlighted in 50% (10) of studies.20,21,23,24,28-30,32,34,36 Approachability was described in only 15% (3) of studies, all of which were qualitative in nature.34,36,37

Table 3.

Five Dimensions of Access and Associated Barriers to Hospice and Palliative Care.

| Approachability | • Messaging and outreach35 • Health literacy considerations34-35,37 |

| Acceptability | • Social/cultural values and norms21-25,30-35,37 • Political perspectives23 |

| Availability | • Geographic location, accomodations20-21,24-25,29,32,34 • Provider level of familiarity with resources23,28,30,36 |

| Affordability | • Household income8,19,21,25,29,37 • Health care insurance benefits20,22,27,31-32,34 |

| Appropriateness | • Coordination of care19,30,33,35 • Quality of care8,19-22,24,26,28,31-32 |

Quantitative Findings: Impact of Access Disparities on Patient Outcomes

Though each study employed slightly different outcome measures, trends emerged among the quantitative studies linking sociodemographic factors with end-of-life outcomes. The majority of studies (14) yielded statistically significant differences in outcomes across racial or ethnic minority groups and/or by socioeconomic status.8,20-23,27-32,35-37 Remaining studies did not find race or ethnicity to be significant predictors of service utilization,19,24,25,33 or of outcomes following surgical intervention.26 Twenty-five percent (5) of studies showed those classified as having low socioeconomic status were more likely to have high-intensity interventions, hospital admissions, and ICU stays in the last 30 days of life.8,20,27,31,32 Additionally, 20% (4) of studies showed those same groups were less likely to engage with palliative care or enter hospice when compared with White participants.21,22,30,32 Notably, one study demonstrated divergent results. Sharma and colleagues (2015) found Blacks were more likely than Whites to receive an inpatient palliative care consult and/or be referred to hospice after controlling for relevant covariates.28 Potential explanations for increased involvement of hospice and palliative care related to providers’ assumptions and implicit biases regarding socioeconomic status and perceived discordance among family members.28 Additionally, providers may have been more likely to place a consult for patients with Medicaid insurance (who were primarily Black) given the systematic coverage for hospice services, as compared to patients with private insurance policies.28 Some studies (6) found females tended to use services more frequently than males,22,24,25,30-32 and others (4) saw the association between sex and service utilization more pronounced in older patients.22,30-32 Contrarily, though the mean age in most studies was >65 years, one study found that those receiving palliative care referrals tended to be beneath this threshold.24 Two studies used state-level data, demonstrating geographic availability of hospice and palliative care programs was significantly associated with older aged residents, higher household income, urbanicity, and less racial diversity of counties or cities.23,29 These findings are consistent with the 2019 State-by-State Report Card, which showed that despite some variance in regional infrastructure access to hospice and palliative care in rural areas remains limited.1

Qualitative and Mixed Methods: Key Stakeholder Perspectives on Access Disparities

Qualitative studies, including an arm of the single mixed-methods study, involved surveys or interviews with patients,37 providers from various specialties,34,36 and patients, caregivers, and providers.35 Each study elicited various themes surrounding barriers to accessing care on individual, provider, and systems levels; further highlighting the multifaceted nature of this issue. Patients and caregivers cited lack of knowledge and misconceptions about services and options as a common barrier, therein highlighting a lack of approachability.34,36,37 Johnston and colleagues (2019) evaluated use of community health workers as a potential avenue for intervening at the individual level, to improve communication of information in a culturally tailored, more linguistically appropriate manner.35 At the provider level, some physicians stressed that medical hierarchy across specialties can hinder earlier referral to hospice or palliative care, which ultimately precludes availability for patients—some more than others.36 As an example, some physicians reported difficulty delineating when to refer patients to hospice versus involving palliative care given variable trajectories of illness by patient.36 Enhanced integration of end-of-life care in medical training would help bolster providers’ familiarity with resources, and better prepare them to tailor care to each individual’s unique needs.36,37 Among Native American communities, systemic barriers primarily inhibit access to hospice and palliative care.34 Participants pointed to a lack of funding, supportive legislators, and trained staff as sources of difficulty for initiating hospice and palliative care programs on or near reservations.34 Expansion of “pay-for-performance” programs may incentivize hospitals and providers to enhance access to hospice and palliative care services for patients.37 Taken together, communication barriers were a common theme across all studies. Patients, caregivers, and providers collectively noted instances of cultural insensitivity, lack of clarity, poor use of translators, and overuse of medical jargon as hindering access and engagement with hospice and palliative care.34-37 Rectifying “communication chasms” could have significant implications not only on access, but also level of engagement and utilization of hospice and palliative care services.37

Disparities in Access by Demographic Group

Each study was assessed for disparities, or significant differences, in study outcomes across various demographics. These included age, gender, race and/or ethnicity, education level, socioeconomic and/or insurance status, and disease type and/or severity. An “other” category was also included to capture less commonly utilized variables. Majority of studies (12) showed evidence of different outcomes based on participants’ race or ethnicity,8,20-23,27-32,35 and socioeconomic and/or insurance status (11).8,19,20,22,23,27-29,31,32,37 Additionally, 50% (10) of studies highlighted disparities by either disease type or severity.19,21,22,24-26,28,31,33,36 As an example, Hui et al. (2012) found patients with gynecologic, breast, and stomach cancers were more likely to have palliative care access than those with other types of cancer or other diseases.24 Less common differences in access were by age (9),21-24,29-32,37 gender (7),22,24,25,30-32,37 and education level (5).8,25,29,36,37 More than half of studies (12) highlighted differences classified as “other,” which comprised covariates such as, geographic location and/or proximity to an urban area,20,21,23,27,29,30,32,34 heredity,19 political ideations,23, marital status,24,37 inconsistent messaging,35 and comorbidity burden.21,32

Limitations of Included Studies

The included studies had several limitations. Socially disadvantaged populations, mainly non-White individuals, were underrepresented in samples from each of the studies evaluated, particularly those emphasizing comparisons by race and/or ethnicity. Most studies (14) sampled patients, exclusively, but several noted lack of key stakeholder perspectives, such as caregivers and health care providers, as a drawback. Common limitations across all quantitative studies (16) included confounding data, lack of generalizability, and potential for missing or incomplete data. There is potential for bias based on these limitations; however, this was mitigated through completion of an evidence-based methodological appraisal of each article.

Discussion

Integrative Synthesis of Current Literature

This review summarized results from 20 non-experimental quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies that examined disparities in hospice and palliative care access. In general, studies were of acceptable quality and primarily examined samples of patients; caregiver and provider perspectives were evaluated to a much lesser extent. Themes and perspectives that emerged represented barriers at the individual, community, and systems levels. An array of outcome measures were used across included quantitative studies. Even so, we found the health care accessibility conceptual framework provided a helpful, relevant format for understanding the findings of this review.15 The reviewed literature clearly shows a variety of barriers and challenges which span all five domains of access.

Despite the array of outcome variables, access was the primary conceptual focus of all studies within the context of hospice and palliative care. It was important to include hospice and palliative care related studies, as these terms are often used interchangeably despite being two distinct types of care.38 Studies were limited to those conducted in the United States, as health care access challenges vary culturally and geographically. For example, uptake of hospice and palliative care in the United States has, in some ways, been much slower than other countries.39 Additionally, health care systems have unique, individualized guidelines, which makes global comparisons difficult and can attribute to ongoing conflation of what is considered hospice versus palliative care.39

Shifting the Paradigm: Targeting Blind Spots

Current debates on health care in the United States tend to focus on system-level factors such as universal health care access and insurance. Articles in this review focused heavily on the framework domains of Affordability and Appropriateness. It was important to include studies from 2010 onward as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act was passed into law in the United States, signifying an extensive shift in focus toward cost and availability of health care services.40 Provider reimbursement for advance care planning discussions was also made available during this time frame, which could have potentially influenced patients’ level of access to needed services. Overall, findings from this review corroborate the current paradigm, placing heavy emphasis on cost, geographic availability, and appropriateness of services. However, it is naïve to assume that addressing system-level issues will fix patient- and provider-level obstacles—the humanity operating within the system itself.3 The domain of Approachability, or patients’ ability to perceive information, is arguably the most basic component on the spectrum of service access, and may be a driver of health inequities if services are not conveniently tailored to meet patient needs. Per the health care accessibility framework, Approachability should involve gaining patients’ trust through transparently delivering information akin to health beliefs and health literacy levels.14 These types of issues were uncovered in only three studies,34,35,37 indicating basic, yet critical, components of access are being overlooked.

Additionally, disparities were evaluated by sociodemographic groups. Prior studies have emphasized disparities by race and ethnicity, particularly comparing underrepresented groups to non-Hispanic Whites. The majority of included studies (11) yielded findings consistent with existing literature in this regard.8,20-23,28-32,37 However, these results were derived from non-experimental quantitative studies with limited adjustments for confounding variables, and samples comprised of primarily White participants, and should thus be extrapolated cautiously. Hospice and palliative care utilization tended to be associated with females, older age, cancer, and close proximity to an urban area with expansive health care systems. While not entirely surprising, these findings further highlight areas and groups which need bolstering—males, younger ages, diverse disease types, and rural-dwelling individuals. As various disparities and differing needs become increasingly recognized, only then can researchers begin to understand key stakeholder perspectives, to move toward improving outcomes for all patients with serious illness.

By focusing on studies published more recently, this review provides novel insights on access disparities patients experience in the context of hospice and palliative care. The recent systematic review by Mayeda and Ward (2019) focused on barriers to palliative care utilization solely by race and ethnicity,41 whereas, this review delineates hospice and palliative care access disparities by five conceptualized domains: Approachability, Acceptability, Availability, Affordability, and Appropriateness. Furthermore, it provides a more detailed overview of said disparities by multiple sociodemographic groups—aside from just race and ethnicity. Prior reviews have emphasized the importance of overcoming barriers to care. Findings from the current review suggest that barriers cannot be the primary focus until underlying factors actually causing differences in access are more fully understood. This highlights a need for replication of core hospice and palliative care studies in underrepresented groups, to determine if the accepted effectiveness of these services is accurate across more diverse populations. Additionally, a greater emphasis on collaborative participatory work is essential, to collectively identify facilitators and acceptability of hospice and palliative care applications beyond the current paradigm.

Implications for Research, Policy, and Clinical Practice Moving Forward

To enhance the conceptual clarity of access in the context of hospice and palliative care, consistency in terminology and delineation of hospice versus palliative care is important.38 Moreover, shifting this discussion from a funding, setting, and provider discussion to a philosophy of care is necessary. Given the breadth of sociodemographic disparities in health care access, future studies should identify perspectives, experiences, and attitudes from representative samples comprised of patients from diverse backgrounds. Increasing discussion and dialogue among less well-represented groups, such as Native Americans, and Lesbian Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer (LGBTQ+) communities, among others, is essential for the provision of inclusive end-of-life care.42 For example, LGBTQ+ individuals each experience diverse barriers and challenges, yet palliative care research studies, albeit minimal, tend to group them in a single category which perpetuates stereotypes and diminishes inclusivity altogether.43 Establishing collaborations and partnerships with relevant leadership, program staff, and community stakeholders can help in developing culturally tailored services, and enable greater integration of hospice and palliative care programs in underrepresented communities.44 Additionally, greater inclusion of caregiver and provider perspectives will provide greater socio-ecological context to hospice and palliative care access issues at the patient, provider, and health care system levels. Moreover, exploring aspects of intersectionality, the interconnected nature of factors such as race, class, and gender that can contribute to disadvantage, is a fundamental approach to addressing access issues.45 Researchers, clinical practitioners, and policymakers need to consider these perspectives in order to develop a targeted, intentional action plan going forward to abate sociodemographic disparities in end-of-life care.

Strengths and Limitations

This review has several limitations. It is possible our search strategy was not sufficiently broad to capture every domain of access, so studies reporting on disparities in hospice and palliative care may have been missed. Additionally, the minimal inclusion of caregiver and provider perspectives and lack of representative samples hindered our ability to comprehensively synthesize the literature from a true socio-ecological perspective. Finally, lack of diversity in the types of studies included affected overall evidential quality of this review, though it does highlight important areas for future research and prioritization of care for socially disadvantaged populations.

Despite its limitations, this integrative review offers a novel conceptualization of health care access in the context of hospice and palliative care. A particular strength has been the use of an innovative health care accessibility conceptual framework to guide synthesis of the literature. This approach starts to unpack the multiple issues embedded in the term “access” and challenges the assumption “if you create it that they will come.” Taken together, this review provides an enhanced understanding of where disparities exist with regard to accessibility of hospice and palliative care services, with a clear focus for future research and practice development.

Conclusion

This systematic review demonstrates hospice and palliative care access is complex and multifaceted. Variation in messaging, socio-cultural factors, funding models, organizational guidelines, and personal preferences add to this complexity. The critical importance and relevance of hospice and palliative care will continue to expand in the coming decades, particularly as the baby boomer generation grows older, and our country becomes more racially and ethnically diverse and heterogeneous. As a result, gaining greater perspective and understanding must be a high priority to help ensure hospice and palliative care is accessible for all patients and families enduring serious illness.

Contributions of the Paper Statements.

What is already known about the topic?

Hospice and palliative care were both created from a Western cultural perspective and have operated within confines of a traditional paradigm and application since conception.

Disparities in hospice and palliative care accessibility and delivery have been widely documented.

What does this paper add?

Examining hospice and palliative care from a socio-ecological perspective can illuminate the multifaceted array of access and delivery challenges which can arise.

Dissecting key findings through an innovative health care access conceptual framework may support researchers and clinicians in evaluating the unique, individualized barriers and facilitators patients may face in seeking out hospice and palliative care services.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Stella Seal, MLS, for assistance in developing the search strategy, and Sarah Szanton, PhD, ANP, FAAN, for insightful feedback throughout the preparation of this integrative review.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Center to Advance Palliative Care. America’s Care of Serious Illness: A State-by-State Report Card on Access to Palliative Care in Our Nation’s Hospitals. Center to Advance Palliative Care; 2019. Accessed January 26, 2020. https://reportcard.capc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/CAPC_State-by-State-Report-Card_051120.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes MT, Smith TJ. The growth of palliative care in the United States. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:459–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson KE, Wright R, Fisher M, et al. A call to action to address disparities in palliative care access: a conceptual framework for individualizing care needs [published online ahead of print, October 7, 2020]. J Palliat Med. 2020. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2020.0435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlson MD, Bradley EH, Du Q, Morrison RS. Geographic access to hospice in the United States. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(11):1331–1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson KS. Racial and ethnic disparities in palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(11):1329–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davidson PM, Phillips JL, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Thompson SC, Luckett T, Currow DC. Providing palliative care for cardiovascular disease from a perspective of sociocultural diversity: a global view. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2016;10(1):11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orlovic M, Smith K, Mossialos E.Racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life care in the United States: evidence from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS). SSM Popul Health. 2019;7:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown CE, Engelberg RA, Sharma R, et al. Race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and healthcare intensity at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2018;21:1308–1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302(7):741–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. NEJM. 2010;363:733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stajduhar KI, Mollison A, Giesbrecht M, et al. “Just too busy living in the moment and surviving”: barriers to accessing health care for structurally vulnerable populations at end-of-life. BMC Palliat Care. 2019;18(11):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raine R, Fitzpatrick R, Barratt H, et al. Challenges, solutions and future directions in the evaluation of service innovations in health care and public health. HS&DR. 2016;4(16). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Equity. World Health Organization website. Published 2020. Accessed February 5, 2020. https://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/equity/en/

- 14.Levesque J, Harris MF, Russell G. Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12(18):1–9. Accessed January 21, 2020. https://equityhealthj.biomedcentral.com/articles 10.1186/1475-9276-12-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52(5):546–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandelowski M, Voils CI, Leeman J, Crandell JL. Mapping the mixed methods-mixed research synthesis terrain. J Mix Methods Res. 2012;6(4):317–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(6):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newhouse R, Dearholt S, Poe S, Pugh LC, White K. The Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Rating Scale. The Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing. Published 2005. Accessed January 21, 2020. http://evidencebasednurse.weebly.com/uploads/4/2/0/8/42081989/jhnedp_evidence_rating_scale.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andrews JG, Davis MF, Meaney FJ. Correlates of care for young men with Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve. 2014;49(1):21–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gidwani-Marszowski R, Needleman J, Mor V, et al. Quality of end-of-life care is higher in the VA compared to care paid for by traditional Medicare. Health Aff. 2018;37(1):95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Givens JL, Tjia J, Zhou C, Emanuel E, Ash AS. Racial differences in hospice utilization for heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(5):427–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haines KL, Jung HS, Zens T, Turner S, Warner-Hillard C, Agarwal S. Barriers to hospice care in trauma patients: the disparities in end-of-life care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35(8):1081–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoerger M, Perry LM, Korotkin BD, et al. Statewide differences in personality associated with geographic disparities in access to palliative care: findings in openness. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(6):628–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hui D, Kim S, Kwon JH, et al. Access to palliative care among patients at a comprehensive cancer center. Oncologist. 2012;17: 1574–1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar P, Casarett D, Corcoran A, et al. Utilization of supportive and palliative care services among oncology outpatients at one academic cancer center: determinants of use and barriers to access. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(8):923–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee S, Reha JL, Tzeng CD, et al. Race does not impact pancreatic cancer treatment and survival in an equal access federal health care system. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:4073–4079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okafor PN, Stobaugh DJ, Wong Kee Song LM, Limburg PJ, Talwalkar JA. Socioeconomic inequalities in the utilization of colorectal stents for the treatment of malignant bowel obstruction. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:1669–1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma RK, Cameron KA, Chmiel JS, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in inpatient palliative care consultation for patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(32):3802–3808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silveira MJ, Connor SR, Goold SD, McMahon LF, Feudtner C. Community supply of hospice: does wealth play a role? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42(1):76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh T, Peters SR, Tirschwell DL, Creutzfeldt CJ. Palliative care for hospitalized patients with stroke: results from the 2010 to 2012 National Inpatient Sample. Stroke. 2017;48(9):2534–2540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stewart SL, Kwong SL, Bowlus CL, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in hepatocellular carcinoma treatment and survival in California, 1988-2012. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(38):8584–8595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watanabe-Galloway S, Zhang W, Watkins K, et al. Quality of end-of-life care among rural Medicare beneficiaries with colorectal cancer. J Rural Health. 2014;30:397–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Worster B, Bell DK, Roy V, Cunningham A, LaNoue M, Parks S. Race as a predictor of palliative care referral time, hospice utilization, and hospital length of stay: a retrospective noncomparative analysis. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35(1):110–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Isaacson M, Karel B, Varilek BM, Steenstra WJ, Tanis-Heyenga JP, Wagner A. Insights from health care professionals regarding palliative care options on South Dakota reservations. J Transcult Nurs. 2015;26(5):473–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnston FM, Neiman JH, Parmley LE, et al. Stakeholder perspectives on the use of community health workers to improve palliative care use by African Americans with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(3):302–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kavalieratos D, Mitchell EM, Carey TS, et al. “Not the ‘grim reaper service’”: an assessment of provider knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions regarding palliative care referral barriers in heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(1):e000544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Periyakoil VS, Neri E, Kraemer H. Patient-reported barriers to high-quality, end-of-life care: a multiethnic, multilingual, mixed-methods study. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(4):373–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hui D, Mori M, Parsons HA, et al. The lack of standard definitions in the supportive and palliative oncology literature. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;43(3):582–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.The Economist Intelligence Unit. The 2015 Quality of Death Index: Ranking Palliative Care Across the World. The Economist. Published 2015. Accessed June 16, 2020. https://eiuperspectives.economist.com/healthcare/2015-quality-death-index [Google Scholar]

- 40.The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Pub. L. No. 111-148, § 124 Stat 119. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mayeda DP, Ward KT. Methods for overcoming barriers in palliative care for racial/ethnic minorities: a systematic review. Palliat Support Care. 2019;17(6):697–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cloyes KG, Hull W, Davis A. Palliative and end-of-life care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) cancer patients and their caregivers. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2018;34(1):60–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barrett N, Wholihan D. Providing palliative care to LGBTQ patients. Nurs Clin North Am. 2016;51(3):501–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. LTSS Research Literature Review: Hospice in Indian Country. Kauffman & Associates Inc. Published December 15, 2014. Accessed July 1, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/American-Indian-Alaska-Native/AIAN/LTSS-TA-Center/pdf/CMS-Literature-Review.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 45.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Improving Access to and Equity of Care for People with Serious Illness: Proceedings of a Workshop. The National Academies Press; 2019. Accessed July 1, 2020. 10.17226/25530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]