Abstract

Background

In the COVID-19 pandemic, confidence in the government and access to accurate information have been critical to the control of outbreaks. Although outbreaks have emerged amongst communities of international migrant workers worldwide, little is known about how they perceive the government's response or their exposure to rumors.

Methods

Between 22 June to 11 October 2020, we surveyed 1011 low-waged migrant workers involved in dormitory outbreaks within Singapore. Participants reported their confidence in the government; whether they had heard, shared, or believed widely-disseminated COVID-19 rumors; and their socio-demographics. Logistic regression models were fitted to identify factors associated with confidence and rumor exposure.

Results

1 in 2 participants (54.2%, 95% CI: 51.1–57.3%) reported that they believed at least one COVID-19 rumor. This incidence was higher than that observed in the general population for the host country (Singapore). Nonetheless, most participants (90.0%, 95% CI: 87.6–91.5%) reported being confident that the government could control the spread of COVID-19. Age was significantly associated with belief in rumors, while educational level was associated with confidence in government.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that language and cultural differences may limit the access that migrant workers have to official COVID-19 updates. Correspondingly, public health agencies should use targeted messaging strategies to promote health knowledge within migrant worker communities.

Keywords: Migration, Pandemic, Health crisis, Rumor, Misinformation, Trust, Risk

1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has underscored how public cooperation is critical for containment strategies. For example, to reduce COVID-19 infection, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention urged the public to wear face masks; undergo physical distancing; reduce travel; pursue vaccination; and subject themselves for testing, isolation and contact tracing (Honein et al., 2020). While these measures are effective, successful implementation requires compliance from members of the public (Haug et al., 2020; Brauner et al., 2021).

A key aspect of compliance is whether the public trusts the government and has confidence in its COVID-19 response (Lim et al., 2021). Across Europe, for example, adherence to health advisories was dampened in regions reporting low trust in policy-makers (Bargain and Aminjonov, 2020), or following national incidents where confidence was damaged (Fancourt et al., 2020). When confidence is low, rumors also tend to be shared and believed in place of official communication (Vinck et al., 2019). For example, Iran experienced a rapid increase in COVID-19 cases during April 2020 (Aghababaeian et al., 2020). Amidst widespread panic, a rumor was spread that consuming alcohol could prevent COVID-19 infection (Aghababaeian et al., 2020). Within a month, 728 Iranians died from methanol poisoning – an eleven-fold increase from the year before (Aghababaeian et al., 2020). Together, these accounts underscore the centrality of public trust, and the need to understand: (i) how the community assesses the situation, and (ii) the extent to which they rely on rumors (Tangcharoensathien et al., 2021).

Although several national surveys have described public confidence and belief in COVID-19 rumors (Lim et al., 2021; Han et al., 2021; Dryhurst et al., 2020; Sibley et al., 2020, Nielsen and Lindvall), these have largely involved convenient samples where special populations are under-represented. Of note, we know little about the views of international migrant workers – a population of 164 million individuals employed outside their countries of birth (International Labour Organization 2018). This is a group whose views need to be understood for several reasons. First, a large number of migrant workers are employed in low-waged, manual labor jobs involving high-density work (e.g., factories) or living arrangements (e.g., dormitories that host up to 25,000 residents). As physical distancing is difficult to achieve, several large-scale outbreaks have occurred amongst migrant worker groups in Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia, and the Gulf states (Alkhamis et al., 2020; Wahab, 2020; Yi et al., 2020). Second, migrant workers often face barriers accessing healthcare, information, or resources in their host countries (Abubakar et al., 2018; Hargreaves et al., 2019; Liem et al., 2020). These may prevent them from receiving official COVID-19 updates, skewing their risk assessments or increasing their reliance on rumors (Liem et al., 2020).

To address the gap in the literature, we recorded the views of migrant workers in Singapore during the COVID-19 pandemic. The city state is widely considered a ‘high performing health system’ on account of its low case fatality rate (0.05%) and minimal movement restrictions (Legido-Quigley et al., 2020). Surveys of the general population allude to high public confidence in the government, and low rates of sharing or belief in COVID-19 rumors (Lim et al., 2021; Liu and Tong, 2020; Long et al., 2021). Despite these statistics, Singapore provides a case study of health inequalities. Of the 64,000 COVID-19 cases reported to date, 9 in 10 have arisen from the 400,000 male migrant workers employed in Singapore's construction, shipping, and process sectors (Yi et al., 2020; Koh, 2020). One study reported a disease prevalence rate 188 times higher amongst workers living in dormitories (47%) than in the general community (0.25%) (Ministry of Manpower Singapore 2020), and all workers have been placed under prolonged movement restrictions to contain the spread (April-August 2020: complete dormitory lockdown; August 2020-the present time: gradual resumption of work and limited recreation activities). Against this backdrop, we documented confidence in government and the spread of rumors amongst 1011 migrant workers.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

Data were taken from the COVID-19 Migrant Health Study, a cross-sectional survey conducted in Singapore between 22 June to 11 October 2020 (Saw et al., 2021). Respondents were male migrants employed in manual labor jobs, and were included if they met the following eligibility criteria: aged 21 and above, and holding a government-issued permit indicating their employment status. Surveys were made available in the primary languages spoken by migrant workers (English, Bengali, Tamil, Mandarin), and included both audio recordings and written text to ensure survey access regardless of literacy level.

Recruitment took place in-person at: (1) a dormitory complex associated with the largest COVID-19 cluster, (2) transient accommodation for workers relocated from dormitories, (3) construction work sites, and (4) a recreation center for migrant workers. Additionally, an online survey link was advertised through physical posters and on messaging groups (WhatsApp and Telegram) at: (1) quarantine sites for active COVID-19 cases, and (2) worker dormitories.

During the survey period, participants in dormitories lived in shared rooms within complexes that hosted up to 25,000 residents, with multidisciplinary teams providing on-site medical care. For temporary accommodation, participants were roomed individually within residential or hospitality units (e.g., hotels, cruise ships), and had access to off-site medical services upon request. Finally, at quarantine sites, participants stayed in large facilities (e.g., exhibition halls) repurposed to house recovering patients, and had round-the-clock access to on-site medical teams.

All participants provided informed consent in accordance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the National University of Singapore and Singapore Health Services (ClinicalTrials.gov registration: NCT04718519). Participants who were recruited in-person received SGD $10 for their time.

2.2. Survey development

Following analogous surveys conducted during the Ebola and COVID-19 outbreaks (Liu and Tong, 2020; Mesch and Schwirian, 2019), we measured public confidence with three questions: (1) how confident participants were that the government could control the nationwide spread of COVID-19 (4-point scale ranging from “Not confident at all” (1) to “Very confident” (4)); (2) how fearful they were about their health during the COVID-19 situation (4-point scale ranging from “Not scared at all” (1) to “Very scared” (4)); and (3) how fearful they were about losing their job during this period (4-point scale ranging from “Not scared at all” (1) to “Very scared” (4)). Participants who had not tested positive for COVID-19 were also asked to judge the likelihood that they would be infected (4-point scale ranging from “Not at all likely” (1) to “Very likely” (4)).

To assess rumor spread, participants also indicated whether they had heard, believed, or shared each of the following COVID-19 rumors (yes / no): (1) drinking water frequently will help prevent infection (COVID-19 prevention); (2) eating garlic can help prevent infection (COVID-19 prevention); (3) the outbreak arose from people eating bat soup (COVID-19 origins); (4) the virus was created in a US lab to affect China's economy (COVID-19 origins); and (5) the virus was created in a Chinese lab as a bioweapon (COVID-19 origins). On a global scale, these rumors have been widely disseminated and have been studied in other surveys (Long et al., 2021). To provide further context, we also asked participants to estimate how much time they spent each day: (i) looking for updates about COVID-19 (e.g., searching and reading news, browsing websites, watching videos), and (ii) using social media (e.g., WhatsApp, Facebook, TikTok) to discuss or share information about COVID-19.

Finally, we obtained the following sociodemographic data: age, country of origin (Bangladesh, India, Others), marital status (married, not married: single/widowed/separated/divorced), education (primary, secondary, tertiary), years spent in Singapore (≤ 5 years, > 5 years), and history of COVID-19 (tested positive: yes, no).

2.3. Statistical analysis

We first summarised public confidence and the spread of rumors (hearing, believing, and sharing rumors) using counts (%) and means. Where comparisons were made with other national surveys, we ran tests for equality of proportions with continuity corrections (for public confidence) or Welch's t-tests (for rumor spread).

Binary logistic models were run to identify socio-demographic predictors of participants’: confidence in the government (confident: ‘very confident’ and ‘somewhat confident’; not confident: ‘not very confident’ and ‘not confident at all’) [Model 1]; exposure to rumors (low exposure: 0–2 rumors; high exposure: 3–5 rumors) [Model 2]; likelihood of believing rumours (believed at least one rumor, did not believe any rumours) [Model 3]; and likelihood of sharing rumours (shared at least one rumor, did not share any rumours) [Model 4]. Each model involved the following set of predictors: age, country of origin (Bangladesh, India, others), marital status (married, not married: single/widowed/separated/divorced), education (primary, secondary, tertiary), years spent in Singapore (≤ 5 years, > 5 years), and history of COVID-19 (tested positive: yes, no).

Bonferroni correction was applied to each model to control the Type 1 family-wise error rate at 0.05 (Bonferroni-adjusted alpha level of 0.05/8 predictors = 0.006). Analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 20 and R Version 4.0.3.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline participant characteristics

We included data from 1011 survey respondents (78.5% response rate: 87.2%, 882/1011 in-person recruitment; 12.8%, 129/1011 online recruitment). 19.6% (198/1011) were sampled during complete quarantine restrictions (confined to the dormitory), 15.5% (157/1011) under moderate restrictions (confined to the dormitory and work sites), and 64.9% (656/1011) under minimal restrictions (confined to the dormitory, work sites, and recreation centres for leisure).

As shown in Table 1, participants were men with a mean age of 33.2 years (SD: 6.7) and came primarily from South Asia (Bangladesh: 57.1%, 577/1010; India: 37.8%, 382/1010). The majority had spent >5 years in Singapore (63.8%, 643/1008), worked in the construction sector (86.9%, 875/1011), were married (62.7%, 634/1011), and had at least secondary levels of education (89.4%, 896/1002). 1 in 3 participants had been diagnosed with COVID-19 (35.7%, 360/1009).

Table. 1.

Baseline characteristics of respondents (N = 1011).

| Demographic | M (SD) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | 1011 (100) |

| Age | 33.2 (6.7) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Bangladesh | 577 (57.1) |

| India | 382 (37.8) |

| Others | 51 (5.0) |

| Marital status | |

| Not Married | 377 (37.3) |

| Married | 634 (62.7) |

| Education | |

| Primary | 106 (10.6) |

| Secondary | 493 (49.2) |

| Tertiary | 403 (40.2) |

| Years in Singapore | |

| ≤ 5 years | 365 (36.2) |

| > 5 years | 643 (63.8) |

| Work sector | |

| Construction | 875 (86.9) |

| Others (e.g., shipyard, petrochemical) | 132 (13.1) |

| Tested positive for COVID-19 | |

| No | 649 (64.3) |

| Yes | 360 (35.7) |

| Public confidence | |

| Confidence in government | |

| Not confident at all | 79 (7.8) |

| Not very confident | 22 (2.2) |

| Somewhat confident | 114 (11.3) |

| Very confident | 793 (78.7) |

| Fear for health | |

| Very scared | 76 (7.5) |

| Somewhat scared | 323 (32.0) |

| Not very scared | 125 (12.4) |

| Not scared at all | 484 (48.0) |

| Fear for job | |

| Very scared | 132 (13.1) |

| Somewhat scared | 274 (27.2) |

| Not very scared | 99 (9.8) |

| Not scared at all | 503 (49.9) |

| Likelihood of COVID-19 infection | |

| Very likely | 54 (8.3) |

| Somewhat likely | 81 (12.5) |

| Not too likely | 110 (17.0) |

| Not at all likely | 403 (62.2) |

| Rumor spread | |

| Time spent checking COVID-19 news (hrs/day) | 1.98 (2.83) |

| Time spent discussing COVID-19 on social media (hrs/day) | 1.86 (2.48) |

| Rumor exposure | |

| Low exposure (0–2 rumors) | 474 (46.9) |

| High exposure (3–5 rumors) | 537 (53.1) |

| Believed rumors | |

| Did not believe any rumors | 463 (45.8) |

| Believed at least one rumor | 548 (54.2) |

| Shared rumors | |

| Did not share any rumors | 845 (83.6) |

| Shared at least one rumor | 166 (16.4) |

3.2. Public confidence

9 in 10 participants reported confidence that the government could control the spread of COVID-19 (90.0% very or somewhat confident; 95% CI: 87.6–91.5%). Correspondingly, the majority of participants reported low levels of fear for their health (60.4% not scared at all or not very scared; 95% CI: 57.3–63.4%) or of losing their job during the pandemic (59.7% not scared at all or not very scared; 95% CI: 56.6–62.8%). Amongst those who had not previously tested positive, most judged it unlikely that they would be infected with COVID-19 (79.2% not at all likely or not too likely; 95% CI: 75.8–82.2%).

Applying binary logistic modeling, we found that education level significantly predicted confidence in government (Table 2). Relative to participants with primary education, participants with secondary or tertiary educational levels were more likely to report confidence in the local government (secondary: adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 2.26, 95% CI: 1.26–4.04; tertiary: AOR = 2.50, 95% CI: 1.33–4.73).

Table. 2.

Predicting confidence in government and rumor spread among migrant workers during the COVID-19 outbreak.

| Model 1 (Confidence in government) | Model 2 (Rumor exposure) | Model 3 (Rumor belief) | Model 4 (Rumor sharing) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | AOR (95% CI) | p | AOR (95% CI) | p | AOR (95% CI) | p | AOR (95% CI) | p |

| Age | 1.00 (0.96, 1.05) | 0.88 | 1.00 (0.97, 1.02) | 0.78 | 1.05 (1.02, 1.07) | 0.001* | 1.00 (0.97, 1.04) | 0.80 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Bangladesh | 0 (ref) | 0 (ref) | 0 (ref) | 0 (ref) | ||||

| India | 1.35 (0.79, 2.33) | 0.27 | 1.50 (1.01, 2.06) | 0.01 | 1.32 (1.00, 1.81) | 0.08 | 1.58 (1.04, 2.41) | 0.03 |

| Others | 0.77 (0.31, 1.89) | 0.57 | 1.65 (0.89, 3.06) | 0.11 | 0.97 (0.52, 1.79) | 0.91 | 2.62 (1.29, 5.34) | 0.008 |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Not Married | 0 (ref) | 0 (ref) | 0 (ref) | 0 (ref) | ||||

| Married | 0.96 (0.58, 1.61) | 0.89 | 0.94 (0.69, 1.28) | 0.71 | 0.90 (0.66, 1.22) | 0.50 | 0.81 (0.53, 1.23) | 0.32 |

| Education | ||||||||

| Primary | 0 (ref) | 0 (ref) | 0 (ref) | 0 (ref) | ||||

| Secondary | 2.26 (1.26, 4.04) | 0.006* | 1.23 (0.80, 1.89) | 0.35 | 0.61 (0.39, 0.94) | 0.03 | 0.57 (0.33, 0.99) | 0.04 |

| Tertiary | 2.50 (1.33, 4.73) | 0.005* | 1.14 (0.73, 1.79) | 0.57 | 0.71 (0.45, 1.13) | 0.15 | 0.88 (0.51, 1.52) | 0.64 |

| Years in Singapore | ||||||||

| ≤ 5 years | 0 (ref) | 0 (ref) | 0 (ref) | 0 (ref) | ||||

| > 5 years | 1.09 (0.67, 1.78) | 0.74 | 0.74 (0.55, 1.00) | 0.05 | 0.76 (0.57, 1.02) | 0.07 | 0.63 (0.42, 0.93) | 0.02 |

| Tested positive for COVID-19 | ||||||||

| No | 0 (ref) | 0 (ref) | 0 (ref) | 0 (ref) | ||||

| Yes | 0.84 (0.53, 1.33) | 0.45 | 1.12 (0.84, 1.49) | 0.43 | 1.00 (0.75, 1.34) | 0.98 | 1.16 (0.78, 1.73) | 0.45 |

Note: AOR=adjusted odds ratio; CI=confidence interval; *indicates significance at p < 0.006 (after Bonferroni correction).

3.3. Exposure to COVID-19 rumors

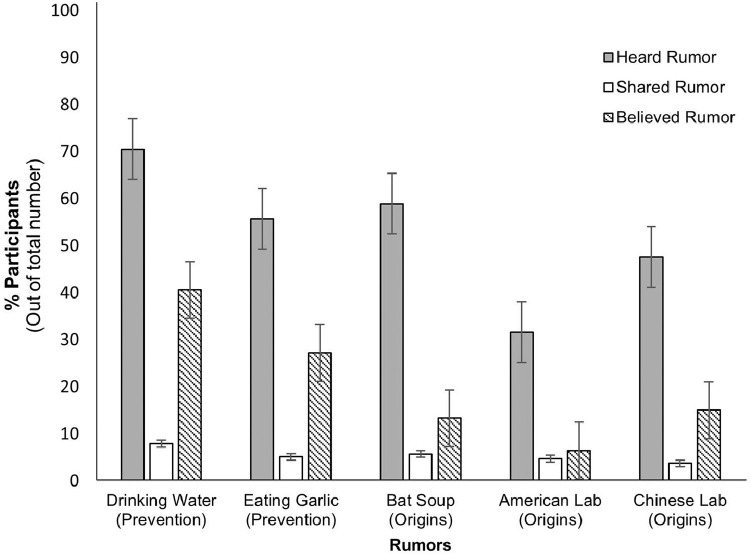

Participants spent an average of 1.98 h (SD = 2.83) each day looking for COVID-19 news, and 1.86 h (SD = 2.48) using social media to discuss or share COVID-19 content. Against this backdrop, 88.9% (95% CI: 86.6–90.8%) of participants had heard at least one COVID-19 rumor (mean exposure: 2.64 rumors, SD = 1.53), with the most widely-heard rumor being that drinking water frequently can prevent infection (rate of hearing: 70.5%, 95% CI: 67.6–73.3%) (Fig. 1). No socio-demographic variable significantly predicted rumor exposure in logistic regression analyses (Table 2).

Fig.. 1.

Percentage of participants hearing, sharing, or believing widely-disseminated COVID-19 rumors (that drinking water or eating garlic can prevent infection; or that the virus originated from bat soup consumption, an American lab, or a Chinese lab). Vertical lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

3.4. Believing COVID-19 rumors

Belief in COVID-19 rumors was high amongst migrant workers, with 1 in 2 participants (54.2%, 95% CI: 51.1–57.3%) reporting that they believed at least one rumor (mean rumors believed = 1.02, SD = 1.24). Again, the most widely believed rumor was that drinking water was a preventive measure (rate of belief: 40.6%, 95% CI: 37.5–43.7%) (Fig. 1).

When we applied logistic regression, older participants were more likely to report belief in rumors (AOR = 1.05, 95% CI: 1.02–1.07; Table 2). Namely, for every one-year increase in participants’ age, they were 1.05 times more likely to believe in COVID-19 rumors.

3.5. Sharing COVID-19 rumors

Finally, few participants (16.4%, 95% CI: 14.2–18.9%) shared COVID-19 rumors with others (mean rumors shared = 0.27, SD = 0.74). Overall rates of rumor-sharing were similar across rumors (range: 3.7% to 7.9%), and no variable emerged as a significant predictor of sharing behavior in logistic regression models (Fig. 1 and Table 2).

3.6. Comparisons with the local resident population

As a context, we compared participants’ responses to earlier community surveys that had been conducted within the Singapore resident population (Liu and Tong, 2020; Long et al., 2021). Relative to the wider population, a higher percentage of migrant workers: (i) were confident that the government could control the spread of COVID-19 (90.0% vs. 86.2%; χ2[1, N = 2071] = 6.76, p = 0.009), and (ii) judged it unlikely that they would be infected (79.2% vs. 60.9%; χ2[1, N = 1711] = 60.93, p < 0.001). Although migrant workers had heard significantly fewer rumors (mean exposure: 2.64 vs. 3.34; t(2014.8) = 11.44, p < 0.001), they believed and shared more rumours (mean rumors believed: 1.02 vs 0.27, t(1379.7) = −17.67, p < 0.001; mean rumors shared: 0.27 vs. 0.18, t(1990.3) = −3.06, p = 0.002).

4. Discussion

In this study, we described for the first time confidence in government and the spread of rumors amongst migrant workers involved in COVID-19 outbreaks. As similar clusters have arisen amongst migrant communities worldwide, this line of work is critical from both a public health and humanitarian standpoint.

As our first observation, we found that participants believed and shared more COVID-19 rumors than the general population. This pattern of data may have arisen for several reasons. First, migration scholars have voiced concerns about migration-related barriers (e.g., language, literacy, social barriers) that may limit access to official COVID-19 updates (Liem et al., 2020). If access is limited, rumors may then be turned to as a substitute source for information. Alternatively, rumors also tend to be spread during anxiety-provoking situations (Anthony, 1973). Given that migrant workers have faced the brunt of infection clusters and prolonged movement restrictions (Ministry of Manpower Singapore 2020), it follows that rumors may also be spread within these settings. Future studies are needed to tease apart these accounts.

Beyond the quantity of rumors circulated, we also observed that the nature of rumors heard, shared, and believed differed between migrant workers and the resident population. For example, the most widely-heard rumor in our sample was that drinking water prevents infection. This same rumor was the least heard in the resident population, who instead reported high exposure to conspiratorial rumors (e.g., that COVID-19 originated from bat soup, an American lab, or a Chinese lab (Long et al., 2021)). Given differing patterns of rumor exposure, our findings make a strong case that risk communication should be tailored for migrant worker communities. We further identified age as a risk factor for believing COVID-19 rumors – consistent with other studies that have implicated age in the spread of misinformation (Guess et al., 2019). To the extent that age corresponds to lower digital literacy (Guess et al., 2019), our finding underscores how increased efforts are needed to reach older workers.

Finally, participants in our study reported high confidence in the government. This finding was unexpected, because: (i) previous studies had linked the spread of rumors to low trust in government (Paek and Hove, 2019), (ii) several migrant groups had reported low trust in government following the onset of COVID-19 (Segrave et al., 2021), (iii) the pandemic had uncovered large disparities between migrant workers and the general population (Yi et al., 2020), and (iv) a non-trivial group of participants (40%) expressed fears about their health or about job security. Together, these factors might be expected to dampen participants’ confidence. Nonetheless, interviews with migrant workers suggest that participants may have compared their situation to that in other countries (Yee et al., 2021). As Singapore's COVID-19 response is perceived as ‘high performing’ globally (Legido-Quigley et al., 2020; Yip et al., 2021), the government may have gained confidence in this manner. Correspondingly, we urge further research to understand the views of migrant workers across different host countries.

In reporting these findings, we note several limitations. First, we only captured migrant workers’ responses at one time-point. As the COVID-19 situation is fluid, more studies are needed to understand how changing circumstances (e.g., the emergence of new variants, vaccination programs) and activities involving the migrant worker community (e.g., employer engagement, government-level initiatives to provide information) may influence responses. Second, our survey used self-reported measures. Participants’ answers may reflect recollection biases or social pressures (e.g., fear of repercussions within a host country), and follow-up research should consider alternate data sources (e.g., by mining social media posts).

5. Conclusions

To conclude, our study provides a rare window into the views of low-waged migrant workers during COVID-19 outbreaks. Despite being confident in the government's response, participants in our study showed a high reliance on health-related rumors. Our findings inform public health agencies as they seek to address migrant worker communities amidst the pandemic.

Declaration of Competing Interests

None declared.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the migrant worker community who hosted us; the surveyors and translators who carried out data collection; hospital, government, and facility staff who granted us research access; and the HealthServe team for feedback during the design phase.

Funding

This work was supported by a JY Pillay Global Asia Grant awarded to JCJL and KD (grant IG20-SG002). The funding source had no involvement in the study design; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; nor in the decision to submit the article for publication.

References

- Abubakar I., Aldridge R.W., Devakumar D., Orcutt M., Burns R., Barreto M.L., Dhavan P., Fouad F.M., Groce N., Guo Y., Hargreaves S., Knipper M., Miranda J.J., Madise N., Kumar B., Mosca D., McGovern T., Rubenstein L., Sammonds P., Sawyer S.M., Sheikh K., Tollman S., Spiegel P., Zimmerman C. The UCL-Lancet commission on migrant and health: the health of a world on the move. Lancet. 2018;392:2606–2654. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32114-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghababaeian H., Hamdanieh L., Ostadtaghizadeh A. Alcohol intake in an attempt to fight COVID-19: a medical myth in Iran. Alcohol. 2020;88:29–32. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2020.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkhamis M.A., Al Youha S., Khajah M.M., Ben Haider N., Alhardan S., Nabeel A., Al Mazeedi S., Al-Sabah S.K. Spatiotemporal dynamics of the COVID-19 pandemic in the State of Kuwait. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;98:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.06.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony S. Anxiety and rumor. J. Soc. Psychol. 1973;89:91–98. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1973.9922572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargain O., Aminjonov U. Trust and compliance to public health policies in times of COVID-19. J. Public Econ. 2020;192 doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauner J.M., Mindermann S., Sharma M., Johnston D., Salvatier J., Gavenciak T., Stephenson A.B., Leech G., Altman G., Mikulik V., Norman A.J., Monrad J.T., Besiroglu T., Ge H., Hartwick M.A., Teh Y.W., Chindelevitch L., Gal Y., Kulveit J. Inferring the effectiveness of government interventions against COVID-19. Science. 2021;371:6531. doi: 10.1126/science.abd9338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dryhurst S., Schneider C.R., Kerr J., Freeman A.L.J., Recchia G., van der Bles A.M., Spiegalhalter D., van der Linden S. Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world. J. Risk Res. 2020;7:994–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Fancourt D., Steptoe A., Wright L. The Cummings effect: politics, trust, and behaviours during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;396:464–465. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31690-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guess A., Nagler J., Tucker J. Less than you think: prevalence and predictors of fake news dissemination on Facebook. Sci. Adv. 2019;5:eaau4586. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aau4586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Q., Zheng B., Cristea M., Agostini M., Belanger J.J., Gutzkow B., Kreienkamp J., Leander N.P., Collaboration P. Trust in government regarding COVID-19 and its associations with preventive health behaviour and prosocial behaviour during the pandemic: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Psychol. Med. 2021 doi: 10.1017/S0033291721001306. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves S., Rustage K., Nellums L.B., McAlpine A., Pocock N., Devakumar D., Aldridge R.W., Abubakar I., Kristensen K.L., Himmels J.W., Friedland J.S., Zimmerman C. Occupational health outcomes among international migrant workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health. 2019;7 doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30204-9. e872–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haug N., Geyrhofer L., Londei A., Dervic E., Desvars-Larrive A., Loreto V., Pinior B., Thurner S., Klimek P. Ranking the effectiveness of worldwide COVID-19 government interventions. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020;4:1303–1312. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-01009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honein M.A., Christie A., Rose D.A., Brooks J.T., Meaney-Delman D., Cohn A., Sauber-Schatz E.K., Walker A., McDonald L.C., Liburd L.C., Hall J.E., Fry A.M., Hall A.J., Gupta N., Kuhnert W.L., Yoon P.W., Gundlapalli A.V., Beach M.J., Walke H.T., Team C.C.-R. Summary of guidance for public health strategies to address high levels of community transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and related deaths, 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020;69:1860–1867. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6949e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization . International Labour Organization: Geneva; 2018. ILO Global Estimates On International Migrant Workers.https://www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/WCMS_652001/lang–en/index.htm Available online. (accessed on 8 July 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Koh D. Migrant workers and COVID-19. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020;77:634–636. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2020-106626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legido-Quigley H., Asgari N., Teo Y.Y., Leung G.M., Oshitani H., Fukuda K., Cook A.R., Hsu L.Y., Shibuya K., Heymann D. Are high-performing health systems resilient against the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet. 2020;395:848–850. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30551-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liem A., Wang C., Wariyanti Y., Latkin C.A., Hall B.J. The neglected health of international migrant workers in the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiat. 2020;7:e20. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30076-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim V.W., Lim R.L., Tan Y.R., Soh A.S., Tan M.X., Othman N.B., Borame Dickens S., Thein T.L., Lwin M.O., Ong R.T., Leo Y.S., Lee V.J., Chen M.I. Government trust, perceptions of COVID-19 and behaviour change: cohort surveys, Singapore. Bull. World Health Organ. 2021;99:92–101. doi: 10.2471/BLT.20.269142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Tong E. The relation between official WhatsApp-distributed COVID-19 news exposure and psychological symptoms: cross-sectional survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22:e22142. doi: 10.2196/22142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long V., Koh W., Saw Y., Liu J. Vulnerability to rumors during the COVID-19 pandemic in Singapore. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2021;50:232–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesch G.S., Schwirian K.P. Vaccination hesitancy: fear, trust, and exposure expectancy of an Ebola outbreak. Heliyon. 2019;5:e02016. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Manpower Singapore . 2020. Measures to Contain the COVID-19 Outbreak in Migrant Worker Dormitories.https://www.mom.gov.sg/newsroompress-releases/2020/1214-measures-to-contain-the-covid-19-outbreak-in-migrant-worker-dormitories Available online. (accessed on 8 July 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, J.H.; Lindvall, J., Trust in government in Sweden and Denmark during the COVID-19 epidemic. West Eur. Polit. In press.

- Paek H.J., Hove T. Mediating and moderating roles of trust in government in effective risk rumor management: a test case of radiation-contaminated seafood in South Korea. Risk Anal. 2019;39:2653–2667. doi: 10.1111/risa.13377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saw Y.E., Tan E.Y., Buvanaswari P., Doshi K., Liu J.C. Mental health of international migrant workers amidst large-scale dormitory outbreaks of COVID-19: a population survey. J. Migr. Health. 2021;4 doi: 10.1016/j.jmh.2021.100062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segrave M., Wickes R., Keel C. Monash University; 2021. Migrant and Refugee Women in Australia: The safety and Security Survey.https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2021-06/apo-nid313003.pdf Available online. (accessed on 8 October 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Sibley C.G., Greaves L.M., Satherley N., Wilson M.S., Overall N.C., Lee C.H.J., Milojev P., Bulbulia J., Osborne D., Milfont T.L., Houkamau C.A., Duck I.M., Vickers-Jones R., Barlow F.K. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and nationwide lockdown on trust, attitudes toward government, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2020;75:618–630. doi: 10.1037/amp0000662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangcharoensathien V., Singh P., Mills A. COVID-19 response and mitigation: a call for action. Bull. World Health Organ. 2021;99 doi: 10.2471/BLT.20.285322. 78-78A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinck P., Pham P.N., Bindu K.K., Bedford J., Nilles E.J. Institutional trust and misinformation in the response to the 2018–19 Ebola outbreak in North Kivu, DR Congo: a population-based survey. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019;19:529–536. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahab A. The outbreak of Covid-19 in Malaysia: pushing migrant workers at the margin. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open. 2020;2 [Google Scholar]

- Yee K., Peh H.P., Tan Y.P., Teo I., Tan E.U.T., Paul J., Rangabashyam M., Ramalingam M.B., Chow W., Tan H.K. Stressors and coping strategies of migrant workers diagnosed with COVID-19 in Singapore: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2021;11 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi H., Ng S.T., Farwin A., Low P.T.A., Chang C.M., Lim J. Health equity considerations in COVID-19: geospatial network analysis of the COVID-19 outbreak in the migrant population in Singapore. J. Travel Med. 2020 doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip W., Ge L., Ho A.H.Y., Heng B.H., Tan W.S. Building community resilience beyond COVID-19: the Singapore way. Lancet Reg. Health West Pac. 2021;7 doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2020.100091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]