Abstract

Background.

Data on associations between sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and incident HIV diagnoses beyond men who have sex with men (MSM) are lacking. Identifying STIs associated with greatest risk of incident HIV diagnosis could help better target HIV testing and prevention interventions.

Methods.

STI and HIV surveillance data from individuals ≥13 years in Tennessee from 1/2013–12/2017 were cross-matched. Individuals without diagnosed HIV, but with reportable STIs (chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis) were followed from first STI diagnosis until HIV diagnosis or end of study. Cox regression with time-varying STI exposure was used to estimate adjusted hazard ratios (aHR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for subsequent HIV diagnosis; results were stratified by self-reported men who have sex with men (MSM).

Results.

We included 148,465 individuals without HIV (3,831 MSM; 144,634 non-MSM, including heterosexual men and women) diagnosed with reportable STIs; 473 had incident HIV diagnoses over 377,823 person-years (p-y) of follow-up (median 2.6 p-y). Controlling for demographic and behavioral factors, diagnoses of gonorrhea, early syphilis, late syphilis, and STI coinfection were independently associated with incident HIV diagnosis compared to chlamydia. Early syphilis was associated with highest HIV diagnosis risk overall (aHR 5.5, 95% CI: 3.5–5.8); this risk was higher for non-MSM (aHR 12.3, 95% CI: 6.8–22.3) versus MSM (aHR 2.9, 95% CI: 1.7–4.7).

Conclusions.

While public health efforts often focus on MSM, non-MSM with STIs are also a subgroup at high risk of incident HIV diagnosis. Non-MSM and MSM with any STI, particularly syphilis, should be prioritized for HIV testing and prevention interventions.

Keywords: Sexually transmitted infections, HIV, male-to-male sexual contact, Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)

Short Summary:

A population-based, Southern statewide observational cohort study found that syphilis was associated with the highest risk of incident HIV diagnosis overall as compared to chlamydia, regardless of self-reported sexual practices.

Introduction

Rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) including chlamydia, gonorrhea and syphilis have shown a persistent increase in recent years, reaching an all-time high in the United States (US) in 2018 according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.1 The southern US, a region that includes the state of Tennessee (TN), has some of the highest rates of reportable STIs1 and remains an area where the HIV epidemic is highly concentrated.2 Integration of HIV and STI programming has been proposed as a method to help decrease disparities in HIV incidence between different demographic groups within communities of the South, and to further address HIV testing and prevention needs.

History of prior STI diagnosis is a risk factor for HIV acquisition,3,4 both as an indicator of condomless sex or membership in a sexual network in which STIs and HIV are present.5,6 Additionally, STIs biologically augment HIV infectivity and individual susceptibility to HIV infection.7,8 Abundant literature exists examining the associations between diagnosis of STIs and incident HIV among male subgroups with multiple anal sex partners,5,9,10 as men who have sex with men (MSM) are disproportionately affected by HIV and other STIs. Previous studies have shown that MSM without diagnosed HIV, but with rectal gonorrhea or syphilis are at increased risk of incident HIV infection,5,9–13 and recent work from two southern US states among women has also shown increased risk of HIV diagnosis among those diagnosed with syphilis or gonorrhea.14,15 However, data on associations between diagnosis of STIs and risk of subsequent HIV diagnosis in the same population of both men and women, regardless of sexual practices, from the southern US are limited.

The introduction and increasing availability of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention has escalated motivation for identifying populations at greatest risk for HIV infection. Current CDC guidelines recommend providers consider PrEP initiation in MSM and heterosexually active men and women with a bacterial STI diagnosed or reported within the last six months plus at least one other HIV risk factor.16 In this era of rising STI rates, identifying STIs associated with greatest risk of subsequent HIV could help better target effective HIV prevention efforts among individuals without HIV, particularly beyond existing HIV prevention programs currently targeted towards MSM. Our objective was to use Tennessee Department of Health surveillance data to study incident HIV diagnosis following STI diagnoses among men and women, including individuals at least 13 years, regardless of their sexual practices.

Materials and Methods

Study Population and Follow-up

We conducted a population-based observational cohort study among individuals without diagnosed HIV at least 13 years of age, but with a diagnosis of chlamydia, gonorrhea, or syphilis reported to the Tennessee Department of Health (TDH) from January 2013–December 2017. We excluded people with prevalent HIV infection at the start of the observation period. Individuals were followed from date of first STI during the observation period until the date of HIV diagnosis or end of observation period (December 31, 2017). Recurrent STIs in the same individual were considered separately by apportioning follow-up time to the most recent prior STI. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at TDH and Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Data Collection and Study Definitions

TDH currently maintains separate surveillance databases for STI and HIV data, both of which are reportable diagnoses by providers or laboratories. These groups provide information to TDH via a case report form or electronic laboratory reporting system. TDH’s Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD) Prevention Program manages the STD case surveillance registry called the Patient Reporting Investigation Surveillance Manager (PRISM). PRISM contains positive STI laboratory results as well as demographic characteristics, behavioral risk factors, and STI treatment information. Similarly, the HIV Epidemiology and Surveillance Program manages the HIV case surveillance registry called the enhanced HIV/AIDS Reporting System (eHARS).17 Demographic information, vital status, HIV transmission risk factors, and HIV-related laboratory results are stored in eHARS. PRISM and eHARS were matched with the probabilistic matching Registry Plus Link Plus software, version 2.0 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia), using first and last names, date of birth, social security number, and sex. After review of the results, we identified a score above which all the proposed matches were true matches according to the suggested score cut-off from LinkPlus documentation. Approximately 14% of the total eHARS data was matched to individuals in PRISM and 2.6% of total PRISM data was matched to individuals in eHARS over the observation period; if the match score was 16.2 or greater the records were deemed to be generated from the same individual.

Outcome and Exposure

Our primary outcome was incident HIV diagnosis, with HIV diagnosis defined per CDC case definition.18 Only positive HIV test results are reportable, therefore individuals were considered HIV negative or unknown status unless otherwise reported. Our primary exposure of interest was STI pathogen, including syphilis (primary, secondary, early latent, late latent, or unknown/unrecorded duration), gonorrhea, or chlamydia defined per CDC case definitions.19 Syphilis diagnoses were further categorized by combining primary, secondary and early latent diagnoses into an early syphilis category and late latent or unknown/unrecorded duration into a late syphilis category to match the general clinical approach to antimicrobial therapy.20 Recurrent syphilis diagnoses were defined as recurrent symptoms or a sustained fourfold increase in nontreponemal test titer.19 Provider reports are included in the surveillance system and were used for syphilis staging. STI coinfection was defined as simultaneous diagnosis of at least 2 different STIs. Dates of STI and HIV diagnoses were defined as the dates of specimen result. For gonorrhea and chlamydia, the site of specimen was categorized as genitourinary (cervical, vaginal, urethral), oropharyngeal, rectal, other (synovial fluid, eye, blood), or not documented.

Covariates

We measured and adjusted for potential confounders and risk modifiers including age, gender, race/ethnicity, men who have sex with men (MSM) status, injection drug use history, TN region or metropolitan area, and year of study entry. Age was defined as age in years at the date of first reportable STI diagnosis during the observation period. Current gender was self-reported via interview at time of STI diagnosis and categorized as male, female, or unknown; transgender status was not recorded in state data during this observation period. Race/ethnicity was also self-reported and categorized as Black non-Hispanic, White non-Hispanic, Hispanic (any race), other non-Hispanic, or unknown. MSM status was collected by self-report; all women, men who did not report MSM, and those with unknown gender were considered non-MSM. Women were not considered separately due to low numbers of HIV events among this group. An individual was considered MSM if male-to-male sexual contact was documented at any time during the observation period. People who inject drugs (PWID) were defined as those with any self-reported injection drug use in the 12 months prior to STI diagnosis. TN area of residence was defined according to the location of residence at time of STI test and categorized into public health regions and metropolitan areas according to TDH.21 Due to small numbers within some regions, these were further combined into five groups including: Memphis/Shelby County, Nashville/Davidson County, West TN (West, Madison), Middle TN (Mid-Cumberland, South Central, Upper Cumberland) and East TN (East, Northeast, Southeast, Hamilton, Knox, Sullivan).

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables are reported as frequency and proportion; continuous variables are reported as median and interquartile range (IQR). Missing data for gender and race/ethnicity was infrequent (<5%) and was therefore coded as unknown. Missing data for sexual behavior was also infrequent (<5%). This was coded as did not report MSM in the analysis.

Unadjusted and adjusted Cox proportional hazard regression models with time-varying STI exposure were used to estimate the adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for incident HIV diagnosis by STI type. For the time-varying analysis, follow-up time was apportioned according to the most recent prior STI diagnosis, including recurrent STIs, over the observation period. Adjusted models included age, gender, race/ethnicity, PWID status, health department region of STI test, and year of study entry. An interaction term for gender by MSM was significant and included in the model. Age and year of study entry were modeled using restricted cubic splines with 5 knots to relax linearity assumptions; 25 years and 2013 were used as reference values, respectively. Chlamydia was chosen as the reference group for the exposure, as it was the most frequent STI diagnosed in TN during each year of the observation period regardless of age group or gender.

Additional analyses stratified results by MSM status and an additional sensitivity analysis was conducted to determine results limited to females only. The proportionality assumption was tested by STI type using the scaled Schoenfeld residuals. Unadjusted incident HIV diagnosis rates were calculated by dividing the total number of new HIV diagnoses by the total person-time at risk. Rates of reported STIs were calculated by dividing number of new cases by TN state population during the year of interest.22 Analyses were conducted using STATA 15.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX).

Results

From January 2013–December 2017, 148,465 individuals without HIV were diagnosed with 206,892 reportable STIs in Tennessee. Overall, these individuals were followed for 377,823 person-years (p-y); median follow-up was 2.6 p-y (IQR 1.3–3.8). Females were followed for 242,026 p-y and individuals <18 for 40,794 p-y. Overall, the median age was 22 years (IQR 19–27) with 15,854 (10.7%) <18 years old; 37.4% were male, 48.6% were Black non-Hispanic, 2.6% self-reported MSM, and 0.4% were PWID among the total cohort. The combined East Regions contributed the highest number of individuals with reportable STIs (27.4%). Chlamydia was the most common STI at cohort entry (n=111,730, 75.3%), followed by gonorrhea (n=20,184, 13.6%). A majority of early (n=1,253, 78.6%) and late syphilis diagnoses (n=1,249, 64.7%) were among men; 46.8% and 21.4% of early and late syphilis diagnoses were among MSM, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics at cohort entry of 148,465 HIV-negative individuals diagnosed with a reportable sexually transmitted infection in Tennessee from 1/1/2013–12/31/2017 overall and by cohort entry STI diagnosis.

| Cohort Entry Diagnosis | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Chlamydia | Gonorrhea | Early | Syphilis | Late | Syphilis | Coinfection | |||||

| n=148,465 | n=111,730 | n=20,184 | n=1,595 | n=1,930 | n=13,026 | |||||||

| Characteristic | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Age, years a | ||||||||||||

| Median 22 | ||||||||||||

| (IQR 19,27) | ||||||||||||

| 13–17 | 15,854 | 10.7 | 12,407 | 11.1 | 1,224 | 6.1 | 24 | 1.5 | 17 | 0.9 | 2,182 | 16.8 |

| 18–24 | 79,188 | 53.3 | 63,075 | 56.4 | 8,155 | 40.4 | 455 | 28.5 | 318 | 16.5 | 7,185 | 55.2 |

| 25–29 | 27,176 | 18.3 | 20,194 | 18.1 | 4,392 | 21.8 | 329 | 20.6 | 289 | 15.0 | 1,972 | 15.1 |

| 30–34 | 12,281 | 8.3 | 8,422 | 7.5 | 2,587 | 12.8 | 208 | 13.0 | 229 | 11.9 | 835 | 6.4 |

| 35–40 | 6,257 | 4.2 | 3,935 | 3.5 | 1,557 | 7.7 | 155 | 9.7 | 219 | 11.4 | 391 | 3.0 |

| 40–44 | 3,232 | 2.2 | 1,851 | 1.7 | 859 | 4.3 | 121 | 7.6 | 205 | 10.6 | 196 | 1.5 |

| ≥45 | 4,477 | 3.0 | 1,846 | 1.7 | 1,410 | 7.0 | 303 | 19.0 | 653 | 33.8 | 265 | 2.0 |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Male | 55,483 | 37.4 | 35,679 | 68.1 | 11,277 | 55.9 | 1,253 | 78.6 | 1,249 | 64.7 | 6,025 | 46.3 |

| Female | 92,970 | 62.6 | 76,045 | 31.9 | 8,905 | 44.1 | 342 | 21.4 | 680 | 35.2 | 6,998 | 53.7 |

| Unknown | 12 | 0.0 | 6 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | 3 | 0.0 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Black non-Hispanic | 72,146 | 48.6 | 48,774 | 43.7 | 12,127 | 60.1 | 929 | 58.2 | 1,190 | 61.7 | 9,126 | 70.1 |

| White non-Hispanic | 61,658 | 41.5 | 50,818 | 45.5 | 6,606 | 32.7 | 577 | 36.2 | 532 | 27.6 | 3,125 | 24.0 |

| Hispanicb | 6,202 | 4.2 | 5,282 | 4.7 | 462 | 2.3 | 65 | 4.1 | 132 | 6.8 | 261 | 2.0 |

| Other | 2,248 | 1.5 | 1,824 | 1.6 | 243 | 1.2 | 15 | 0.9 | 45 | 2.3 | 121 | 0.9 |

| Unknown | 6,211 | 4.2 | 5,032 | 4.5 | 746 | 3.7 | 9 | 0.6 | 31 | 1.6 | 393 | 3.0 |

| MSM | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 3,831 | 2.6 | 875 | 0.8 | 1,165 | 5.8 | 747 | 46.8 | 413 | 21.4 | 631 | 4.8 |

| Noc | 144,634 | 97.4 | 110,855 | 99.2 | 19,019 | 94.2 | 848 | 53.2 | 1,517 | 78.6 | 12,395 | 95.2 |

| PWID | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 624 | 0.4 | 283 | 0.3 | 177 | 0.9 | 42 | 2.6 | 38 | 2.0 | 84 | 0.6 |

| No | 147,841 | 99.6 | 111,447 | 99.8 | 20,007 | 99.1 | 1,553 | 97.4 | 1,892 | 98.0 | 12,942 | 99.4 |

| TN Regions and Metropolitan Areas | ||||||||||||

| Memphis/Shelby County | 37,696 | 25.4 | 26,229 | 23.5 | 5,586 | 27.7 | 647 | 40.6 | 46 | 46.0 | 4,346 | 33.4 |

| Nashville/Davidson County | 20,696 | 13.9 | 14,745 | 13.2 | 3,441 | 17.1 | 303 | 19.0 | 306 | 15.9 | 1,901 | 14.6 |

| West TN | 14,885 | 10.0 | 11,574 | 10.4 | 1,843 | 9.1 | 94 | 5.9 | 56 | 2.9 | 1,318 | 10.1 |

| Middle TN | 34,547 | 23.3 | 27,953 | 25.0 | 3,707 | 18.4 | 240 | 15.1 | 248 | 12.9 | 2,399 | 18.4 |

| East TN | 40,641 | 27.4 | 31,229 | 28.0 | 5,607 | 27.8 | 311 | 19.5 | 432 | 22.4 | 3,062 | 23.5 |

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; STI, sexually transmitted Infection; MSM, men who have sex with men; PWID, people who inject drugs; TN, Tennessee.

Age is age at time of cohort entry STI diagnosis.

Hispanic of any race.

Includes both heterosexual men and women.

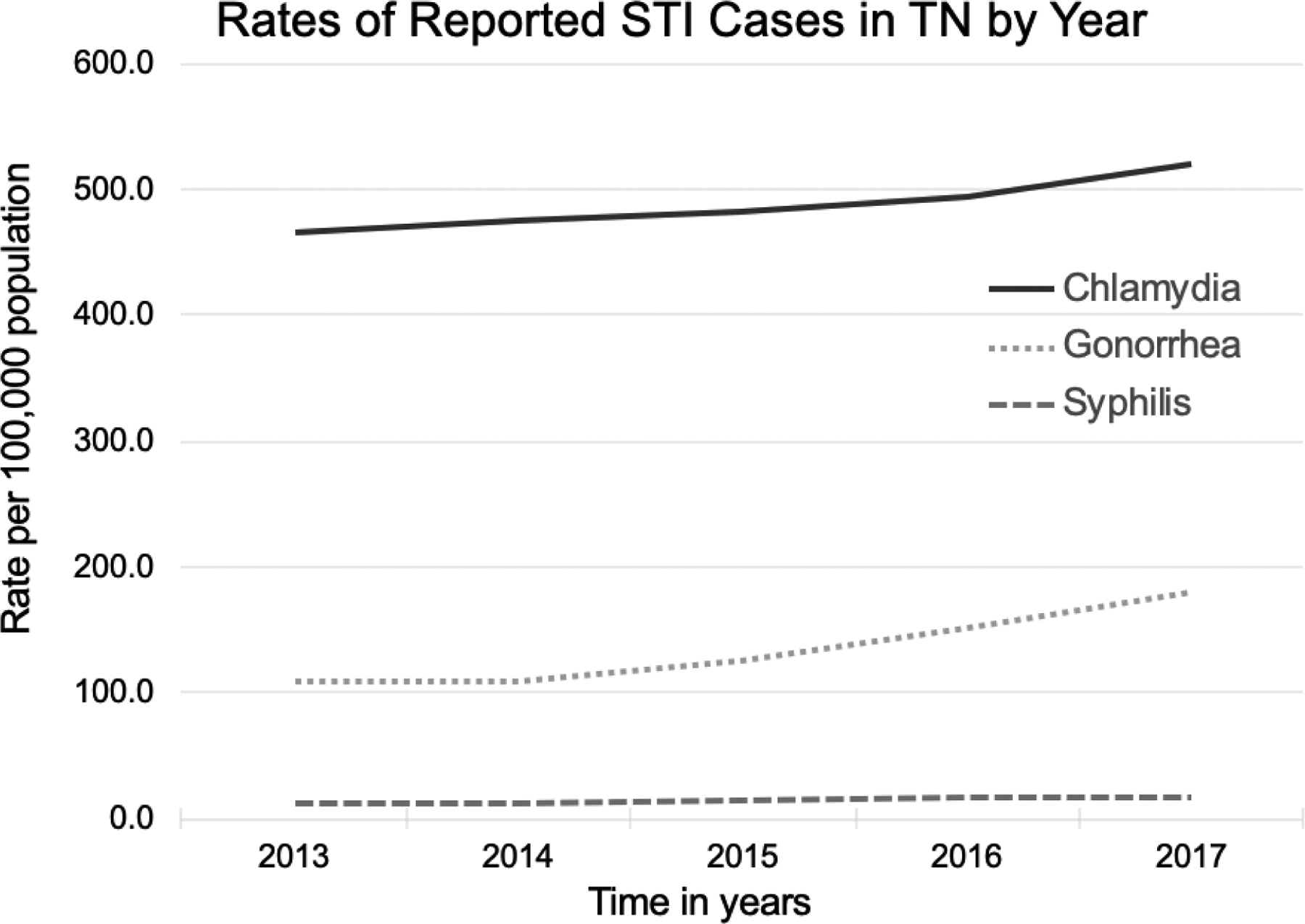

There were 3,831 MSM without diagnosed HIV, but with 6,818 reportable STIs over 8,938 p-y of follow-up (median follow-up 2.3 p-y; IQR 0.3–3.5) and 144,634 non-MSM without diagnosed HIV, but with 200,074 reportable STIs over 369,609 p-y of follow-up (median 2.6 p-y follow-up; IQR 1.3–3.8). STI frequencies rose over time from 35,962 in 2013 (586.5 cases per 100,000 population) to 47,590 total cases in 2017 (716.5 cases per 100,000 population) (Figure 1). Among chlamydia diagnoses, 56,286 (40.9%) were genitourinary (GU) specimens, 776 (0.6%) were oropharyngeal specimens, 259 (0.2%) were rectal specimens, 19,728 (14.4%) were documented from another site and the remaining 43.9% had no site documented. Among gonorrhea diagnoses, 11,505 (42.5%) were GU, 832 (3.1%) were oropharyngeal, 388 (1.4%) were rectal, and 6,711 (24.5%) were recorded from another site with the remainder 38.9% not documented.

Figure 1:

Rate of reported cases of Chlamydia, Gonorrhea and Syphilis (all stages) in Tennessee (TN) by calendar year of STI diagnosis during the observation period, 2013–2017. Pearson’s χ2 test statistic used to compare STI frequencies among all three groups.

Overall, 473 (0.32%) were diagnosed with HIV following an STI diagnosis (12.5 diagnoses per 10,000 p-y). Reported HIV diagnoses following STI diagnoses increased from 42 in 2013 (0.6 per 100,000 population) to 283 in 2017 (4.2 per 100,000 population). Among those who were not diagnosed with HIV following STI diagnosis during the observation period, median age at cohort entry was 22 years (IQR 19–27), with 37.2% male, 48.5% Black non-Hispanic, 2.4% MSM and 0.4% PWID (Table 2). In comparison, among those with an HIV diagnosis following STI diagnosis during the observation period, the median age at cohort entry was 24 years (IQR 20–30), with 89.0% male, 69.3% Black non-Hispanic, 46.9% MSM, and 2.5% PWID. The Memphis/Shelby County public health region contributed the highest number of individuals with incident HIV diagnosis following STI diagnosis (Table 2). Among individuals <18 years diagnosed with incident HIV diagnoses (n=14, 3.0% of total HIV diagnoses), a majority were male (n=10, 71%). Among self-reported MSM, 222 (5.8%) had incident HIV diagnosis following STI diagnosis (25.01 per 1,000 p-y) and among non-MSM, 251 (0.2%) had incident HIV diagnosis following STI diagnosis (36.6 per 1,000 p-y).

Table 2:

Demographic characteristics at cohort entry of 148,465 HIV-negative individuals diagnosed with a reportable sexually transmitted infection in Tennessee from 1/1/2013–12/31/2017 shown by outcome of incident HIV diagnosis during study period.

| Remained HIV-Negative | Incident HIV Diagnosis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=147,992 | n=473 | |||

| Characteristic | n | % | n | % |

| Age, years a | ||||

| 13–17 | 15,840 | 10.7 | 14 | 3.0 |

| 18–24 | 78,947 | 53.4 | 241 | 51.0 |

| 25–29 | 27,078 | 18.3 | 98 | 20.7 |

| 30–34 | 12,234 | 8.3 | 47 | 9.9 |

| 35–40 | 6,230 | 4.2 | 27 | 5.7 |

| 40–44 | 3,214 | 2.2 | 18 | 3.8 |

| ≥45 | 4,449 | 3.0 | 28 | 5.9 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 55,062 | 37.2 | 421 | 89.0 |

| Female | 92,918 | 62.8 | 52 | 10.7 |

| Unknown | 12 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Black non-Hispanic | 71,818 | 48.5 | 328 | 69.3 |

| White non-Hispanic | 61,525 | 41.6 | 133 | 28.1 |

| Hispanicb | 6,190 | 4.2 | 12 | 2.5 |

| Other | 2,248 | 1.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Unknown | 6,211 | 4.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| MSM | ||||

| Yes | 3,609 | 2.4 | 222 | 46.9 |

| Noc | 144,383 | 97.6 | 251 | 53.1 |

| PWID | ||||

| Yes | 612 | 0.4 | 12 | 2.5 |

| No | 147,380 | 99.6 | 461 | 97.5 |

| TN Regions and Metropolitan Areas | ||||

| Memphis/Shelby County | 37,535 | 25.4 | 161 | 34.0 |

| Nashville/Davidson County | 20,588 | 13.9 | 108 | 22.8 |

| West TN | 14,845 | 10.0 | 40 | 8.5 |

| Middle TN | 34,483 | 23.3 | 64 | 13.5 |

| East TN | 40,541 | 27.4 | 100 | 21.1 |

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; STI, sexually transmitted Infection; MSM, men who have sex with men; PWID, people who inject drugs; TN, Tennessee.

Age is age at time of cohort entry STI diagnosis.

Hispanic of any race.

Includes both heterosexual men and women

Time-varying Exposure Analysis

When the exposures were treated as time-varying and time at risk apportioned separately by STI, individuals with chlamydia were followed for the greatest amount of time (287,474.3 p-y), followed by those with gonorrhea (49,281.3 p-y) and any coinfection (34,496.9 p-y). All reportable STIs were independently associated with an increased hazard of incident HIV diagnosis compared to chlamydia. The adjusted hazard of incident HIV diagnosis was greatest for those diagnosed with early syphilis (aHR=5.5, 95% CI: 3.8–7.9) and late syphilis (aHR=5.0, 95% CI: 3.3–7.5) as compared to those diagnosed with chlamydia (Table 3). In addition to each of the STIs, PWID status was independently associated with a greater hazard of incident HIV diagnosis (aHR=4.0, 95% CI: 2.2–7.5) as compared to no reported use. Individuals of White non-Hispanic race had a lower hazard of incident HIV diagnosis (aHR=0.6, 95% CI: 0.5–0.7) as compared to those of Black non-Hispanic race and there was no significant difference in risk of incident HIV diagnosis among age groups.

Table 3.

Adjusted hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for incident HIV-infection by STI type.

| Characteristic | HIV Incidence Ratea | Adjusted Hazard Ratiob | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n=148,465; HIV events=473 |

per 1000 p-y | aHR | 95% CI |

| STI Diagnosis | |||

| Chlamydia | 0.5 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Gonorrhea | 4.8 | 4.5 | 3.5 – 5.8 |

| Early Syphilis | 28.4 | 5.5 | 3.8 – 7.9 |

| Late Syphilis | 11.5 | 5.0 | 3.3 – 7.5 |

| Coinfection | 5.1 | 3.3 | 2.4 – 4.4 |

| Age, years c | |||

| 20 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 0.8 – 1.4 |

| 25 | 2.2 | Ref. | Ref. |

| 30 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 0.8 – 1.2 |

| 40 | 3.3 | 1.0 | 0.8 – 1.2 |

| 50 | 4.6 | 0.9 | 0.6 – 1.3 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 0.3 | § | § |

| Male | 4.7 | § | § |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Black non-Hispanic | 2.7 | Ref. | Ref. |

| White non-Hispanic | 1.2 | 0.6 | 0.5 – 0.7 |

| Hispanicd | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.3 – 0.9 |

| Other | 0 | 0.0 | — |

| Unknown | 0 | 0.0 | — |

| MSM Status | |||

| Noe | 0.9 | § | § |

| Yes | 41.7 | § | § |

| PWID | |||

| No | 1.9 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | 11.7 | 4.0 | 2.2 – 7.5 |

| TN Regions and Metropolitan Areas | |||

| Memphis/Shelby County | 2.5 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Nashville/Davidson County | 3.3 | 1.0 | 0.8 – 1.3 |

| West TN | 1.5 | 0.7 | 0.5 – 1.0 |

| Middle TN | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.4 – 0.7 |

| East TN | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.4 – 0.7 |

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; STI, sexually transmitted Infection; aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; Ref, reference category; MSM, men who have sex with men; PWID, people who inject drugs; TN, Tennessee.

Unadjusted/crude HIV incidence rate by variable.

Adjusted for all variables included in the table, in addition to calendar year of study entry.

Age is age at time of first STI diagnosis during the study period. Age was modeled using restricted cubic splines with 5 knots to relax linearity assumptions; 25 years was used as reference value.

Hispanic of any race.

Includes both heterosexual men and women.

Bold estimates have p <0.05.

An interaction term was used for gender by MSM status in adjusted analysis.

When analyses were stratified by self-identified sexual risk behavior, non-MSM (including heterosexual men and women) showed the greatest hazard of incident HIV diagnosis following diagnosis of early syphilis (incidence=10.3 per 1000 p-y; aHR=12.3, 95% CI: 6.8–22.3) and late syphilis (incidence=6.1 per 1000 p-y; aHR=9.9, 95% CI: 5.6–17.2), and all STIs were associated with a significantly greater hazard of incident HIV diagnosis compared to chlamydia diagnoses. MSM had the greatest hazard of incident HIV diagnosis following a diagnosis of early syphilis (incidence=50.2 per 1000 p-y; aHR=2.9, 95% CI: 1.7–4.7), and all STIs were associated with significantly greater hazard of incident HIV diagnosis compared to chlamydia (Table 4). Among females, incidence of HIV diagnosis was highest among those diagnosed with early syphilis, but no STI was independently associated with a greater hazard of incident HIV diagnosis compared to chlamydia.

Table 4.

Adjusted hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for incident HIV-infection by STI type, stratified by self-reported MSM status.

| Non-MSMa | MSM | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=144,652; HIV events=253 | n=3,813; HIV events=220 | |||||

| HIV Incidence Rateb | HIV Incidence Rateb | |||||

| STI Diagnosis | per 1000 p-y | aHR | 95% CI | per 1000 p-y | aHR | 95% CI |

| Chlamydia | 0.4 | Ref. | Ref. | 22.5 | Ref. | Ref. |

| Gonorrhea | 2.8 | 5.5 | 4.1 – 7.4 | 37.0 | 2.1 | 1.3 – 3.3 |

| Early Syphilis | 10.3 | 12.3 | 6.8 – 22.3 | 50.2 | 2.9 | 1.7 – 4.7 |

| Late Syphilis | 6.1 | 9.9 | 5.6 – 17.2 | 35.1 | 2.2 | 1.2 – 4.1 |

| Coinfection | 1.9 | 2.8 | 1.9 – 4.2 | 72.4 | 2.3 | 1.4 – 3.8 |

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; STI, sexually transmitted Infection; aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; Ref, reference category; p-y, person-years; MSM, men who have sex with men.

non-MSM includes both heterosexual men and women.

Unadjusted/crude HIV incidence rate.

Bold estimates have p <0.05.

When considering any chlamydia or gonorrhea diagnosis by specimen source, all individuals with rectal chlamydia or gonorrhea had a significantly greater hazard of incident HIV diagnosis (aHR=4.5, 95% CI: 2.7–7.6) as compared to those with genitourinary (GU) sources, followed by those with a diagnosis of chlamydia or gonorrhea from an oral source (aHR=3.2, 95% CI: 1.9–5.5) (Table 5). Among those diagnosed with only chlamydia or only gonorrhea, rectal source of infection was again associated with the greatest hazard of incident HIV compared to GU sources of infection (aHR=7.6, 95% CI: 3.3–17.6 and aHR 3.1, 95% CI: 1.86–6.1, respectively). Among the total cohort, there were 52 individuals who were diagnosed with ≥2 different STIs at different documented sites on the same date. Separately, there were 8,548 individuals with ≥2 different STIs at the same documented site on the same date.

Table 5.

Adjusted hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for incident HIV-infection by STI type, stratified by specimen source for Chlamydia or Gonorrhea diagnoses.

| Chlamydia or Gonorrhea | Chlamydia Only | Gonorrhea Only | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=132,351; HIV events=278 | n=114,243; HIV events=112 | n=24,289; HIV events=166 | ||||

| Specimen Source | aHR | 95% CI | aHR | 95% CI | aHR | 95% CI |

| Genitourinary | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Oral | 3.2 | 1.9 – 5.5 | 3.9 | 1.3 – 11.6 | 2.4 | 1.3 – 4.4 |

| Rectal | 4.5 | 2.7 – 7.6 | 7.6 | 3.3 – 17.6 | 3.1 | 1.6 – 6.1 |

| Other | 1.2 | 0.8 – 1.9 | 0.7 | 0.3 – 1.7 | 1.6 | 0.9 – 2.9 |

| Not Documented | 1.5 | 1.1 – 2.0 | 1.3 | 0.8 – 2.0 | 1.7 | 1.2 – 2.5 |

Adjusted for age at cohort entry, self-reported MSM status, race/ethnicity, history of injection drug use, Tennessee region/metropolitan area, year of study entry.

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; STI, sexually transmitted Infection; aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; Ref, reference category; p-y, person-years; MSM, men who have sex with men.

Bold estimates have p <0.05.

Discussion

We estimated the risk of HIV diagnosis after a reported STI diagnosis among all individuals in TN from 2013–2017 using statewide public health surveillance data. Among all individuals diagnosed with reportable STIs over this 5-year observation period, risk of incident HIV diagnosis differed by STI type. All STIs (gonorrhea, early syphilis, late syphilis, and any STI coinfection) were independently associated with increased risk of incident HIV diagnosis in the overall cohort compared to chlamydia, with greatest risk following a diagnosis of syphilis.

When stratified by self-reported non-MSM (including heterosexual men and women) versus MSM status, non-MSM notably displayed a remarkable 12-fold increased risk of incident HIV diagnosis following diagnosis of early syphilis and a 9-fold increased risk of HIV diagnosis following diagnosis of late syphilis compared to non-MSM with chlamydia. Several influential studies have assessed the risk of HIV associated with STI diagnosis among males including heterosexual males in the US,5,13,23,24 showing high HIV incidence among male non-MSM diagnosed with primary or secondary syphilis as compared to no STI. These prior studies have focused on non-MSM from populations in metropolitan areas such as Baltimore and New York City. Our study supports their findings, and helps further quantify risk of incident HIV diagnosis when compared to other STIs in the southern US among a broader population including women and adolescents.

Our results also support previous studies showing a history of rectal chlamydia and/or gonorrhea to be significantly associated with subsequent HIV infection among MSM. Prior published data has found a direct correlation between the incidence of rectal chlamydia25 or gonorrhea and incident HIV among MSM not on PrEP,11,26–30 and noteworthy work by Mullick et al12 suggests that a rectal gonorrhea and incident HIV correlation could help predict high-risk sexual behavior in PrEP trials. Our results show that compared to genitourinary diagnoses, those with rectal chlamydia and/or gonorrhea had significantly greater risk of incident HIV diagnosis in the overall cohort including heterosexual men and women. We also observed that oral chlamydia and/or gonorrhea diagnoses also had elevated risk compared to genitourinary diagnoses, though we hypothesized this finding may be partially due to these individuals also having rectal swabs completed at the same visit. These findings may help expand understanding of the STI and HIV correlation and add to prediction tools for HIV diagnoses without limitation to MSM subgroups.

This study also demonstrates the value of using statewide surveillance data to guide HIV testing and prevention strategies as well as advance health policy. We observed 3% of all those with incident HIV diagnoses following an STI diagnosis to be in individuals <18 years (crude incidence rate of 0.34 per 1,000 p-y among this population). This outcome reinforces the need to maintain HIV testing and PrEP access in younger populations and supports consideration of providers in TN offering PrEP without parental consent when medically appropriate.

These results may also help influence our current statewide PrEP guidelines and further inform prevention tactics. Current public health emphasis and CDC guidelines recommend offering PrEP to MSM at risk of sexual HIV acquisition,16 though short appointment times and provider discomfort often result in a limited sexual history and patients frequently do not disclose same-sex behaviors in areas of the southern US where stigma remains. Our study reinforces emphasis on offering PrEP to all individuals at time of STI diagnosis with history of bacterial STI in the southern US regardless of reported sexual practices. It also adds to our understanding of HIV risk among the Tennessee population and may help prioritize limited resources, as not all STIs among different cohorts convey the same HIV risk.

This study has several limitations inherent with use of surveillance system data. First, it is likely that because the surveillance system was unable to capture people lost to follow-up with respect to diagnosis of HIV, such as by moving out of TN after diagnosis of an STI or those who stopped receiving medical care altogether, it may lead to an overestimation of outcome-free time at risk. In addition, for both STI and HIV diagnoses, the diagnosis date indicated in the surveillance system does not represent date of true infection but the date of positive diagnostic test. This documentation may have resulted in an underestimation of true numbers of STIs due to individuals with clinical diagnoses who did not undergo confirmatory testing. While this likely biases our results towards the null, we were still able to see striking risk differences despite this potential underestimation of incident HIV diagnosis. Additionally, PrEP data was not collected until the end of the observation period by state surveillance systems, and therefore could not be considered in our analysis. While PrEP uptake was minimal in TN during this time, inability to account for it is a limitation of this analysis. Additionally, information pertaining to risk factors for STI or HIV diagnosis was obtained by self-report, and inaccuracies due to limited self-reporting are probable. This may be especially true for self-report of sexual behavior, which seems likely due to the low proportion of MSM listed in the STI surveillance system and the existing stigma that remains present in the Southern US. While the analysis may be under-reporting MSM, it does not change the emphasis that persons with STIs should be offered HIV testing and prevention interventions at time of STI diagnosis. It is also possible that MSM and women had an increase in STI testing due to self-determination of risk or increase in symptomatic disease, which may lead to screening bias. Additionally, diagnosis depends on testing and testing may be more frequent in some groups compared to others. Finally, because these data represent only those individuals living in TN, results may not be generalizable to elsewhere in the country.

In conclusion, we found that all individuals diagnosed with any reportable STI in Tennessee (particularly early and late syphilis) were at high risk for future HIV diagnosis when compared to chlamydia diagnosis regardless of self-reported sexual practices. This analysis may provide guidance for providers in identifying individuals at risk of HIV diagnosis through awareness of which STIs have greatest risk of subsequent HIV diagnosis; this may be especially useful in high-volume clinical settings in which a detailed HIV risk history assessment may not be easily obtained or in which resources are limited. These individuals might also be better targeted by public health agencies for specific HIV testing and prevention outreach. While these results show the benefits of using surveillance data to guide prevention strategies, further research is needed to better understand the relationships between specific STI diagnoses and the subsequent timing of HIV diagnosis among broad populations.

Financial Support:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [T32 AI07474 to S.K., R01 MH113438 to A.P., K01 AI131895 to P.F.R., R21 AI145686 to P.F.R., and P30 AI110527 to S.M.].

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2018. US Department of Health and Human Services. Atlanta; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 20172018. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html (accessed October 17, 2019).

- 3.Venkatesh KK, van der Straten A, Cheng H, et al. The relative contribution of viral and bacterial sexually transmitted infections on HIV acquisition in southern African women in the Methods for Improving Reproductive Health in Africa study. Int J STD AIDS 2011; 22(4): 218–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ward H, Rönn M. Contribution of sexually transmitted infections to the sexual transmission of HIV. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2010; 5(4): 305–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tilchin C, Schumacher CM, Psoter KJ, et al. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Diagnosis After a Syphilis, Gonorrhea, or Repeat Diagnosis Among Males Including non-Men Who Have Sex With Men: What Is the Incidence? Sex Transm Dis 2019; 46(4): 271–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katz DA, Dombrowski JC, Bell TR, Kerani RP, Golden MR. HIV Incidence Among Men Who Have Sex With Men After Diagnosis With Sexually Transmitted Infections. Sex Transm Dis 2016; 43(4): 249–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schust DJ, Ibana JA, Buckner LR, et al. Potential mechanisms for increased HIV-1 transmission across the endocervical epithelium during C. trachomatis infection. Curr HIV Res 2012; 10(3): 218–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen CR, Plummer FA, Mugo N, et al. Increased interleukin-10 in the the endocervical secretions of women with non-ulcerative sexually transmitted diseases: a mechanism for enhanced HIV-1 transmission? AIDS 1999; 13(3): 327–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harney BL, Agius PA, El-Hayek C, et al. Risk of Subsequent HIV Infection Following Sexually Transmissible Infections Among Men Who Have Sex With Men. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019; 6(10): ofz376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernstein KT, Marcus JL, Nieri G, Philip SS, Klausner JD. Rectal gonorrhea and chlamydia reinfection is associated with increased risk of HIV seroconversion. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010; 53(4): 537–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelley CF, Vaughan AS, Luisi N, et al. The Effect of High Rates of Bacterial Sexually Transmitted Infections on HIV Incidence in a Cohort of Black and White Men Who Have Sex with Men in Atlanta, Georgia. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2015; 31(6): 587–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mullick C, Murray J. Correlations Between Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Infection and Rectal Gonorrhea Incidence in Men Who Have Sex With Men: Implications for Future HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis Trials. J Infect Dis 2020; 221(2): 214–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aziz S, Sweat D. Subsequent HIV Diagnosis Risk After Syphilis in a Southern Black Population. Sex Transm Dis 2018; 45(10): 643–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Newman DR, Rahman MM, Brantley A, Peterman TA. Rates of new HIV diagnoses after Reported STI, Women in Louisiana 2000–2015: Implications for HIV Prevention. Clin Infect Dis 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peterman TA, Newman DR, Maddox L, Schmitt K, Shiver S. Risk for HIV following a diagnosis of syphilis, gonorrhoea or chlamydia: 328,456 women in Florida, 2000–2011. Int J STD AIDS 2015; 26(2): 113–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US Public Health Service: Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States—2017 Update: a clinical practice guideline. 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2017.pdf (accessed December 21 2019).

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Enhanced HIV/AIDS Reporting System. Atlanta, GA: CDC; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18.(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Revised surveillance case definition for HIV infection--United States, 2014. MMWR Recomm Rep 2014; 63(RR-03): 1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Appendix C. STD Surveillance Case Definitions July 24, 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/appendix-c.htm (accessed August 1 2018).

- 20.Workowski KA, Bolan GA, Prevention CfDCa. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep 2015; 64(RR-03): 1–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tennessee Department of Health. Local and Regional Health Departments. 2018. https://www.tn.gov/health/health-program-areas/localdepartments.html (accessed 2018 August 1).

- 22.United States Census Bureau PD. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for the United States, Regions, States, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2018. In: National Population Totals and Components of Change: 2010–2017. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pathela P, Braunstein SL, Blank S, Schillinger JA. HIV incidence among men with and those without sexually transmitted rectal infections: estimates from matching against an HIV case registry. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57(8): 1203–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pathela P, Braunstein SL, Blank S, Shepard C, Schillinger JA. The high risk of an HIV diagnosis following a diagnosis of syphilis: a population-level analysis of New York City men. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61(2): 281–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mizushima D, Takano M, Uemura H, et al. High prevalence and incidence of rectal Chlamydia infection among men who have sex with men in Japan. PLoS One 2019; 14(12): e0220072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris SR, Klausner JD, Buchbinder SP, et al. Prevalence and incidence of pharyngeal gonorrhea in a longitudinal sample of men who have sex with men: the EXPLORE study. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 43(10): 1284–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jin F, Prestage GP, Imrie J, et al. Anal sexually transmitted infections and risk of HIV infection in homosexual men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010; 53(1): 144–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Molina JM, Capitant C, Spire B, et al. On-Demand Preexposure Prophylaxis in Men at High Risk for HIV-1 Infection. N Engl J Med 2015; 373(23): 2237–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGowan I, Cranston RD, Mayer KH, et al. Project Gel a Randomized Rectal Microbicide Safety and Acceptability Study in Young Men and Transgender Women. PLoS One 2016; 11(6): e0158310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Girometti N, Gutierrez A, Nwokolo N, McOwan A, Whitlock G. High HIV incidence in men who have sex with men following an early syphilis diagnosis: is there room for pre-exposure prophylaxis as a prevention strategy? Sex Transm Infect 2017; 93(5): 320–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]