Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis.

Many clinicians utilize standard culture of voided urine to guide treatment for women with recurrent urinary tract infections (RUTI). However, despite antibiotic treatment, symptoms may persist and events frequently recur. The cyclic nature and ineffective treatment of RUTI suggests that underlying uropathogens pass undetected due to the preferential growth of Escherichia coli. Expanded quantitative urine culture (EQUC) detects more clinically relevant microbes. The objective of this study was to assess how urine collection and culture methods influence microbial detection in RUTI patients.

Methods.

This cross-sectional study enrolled symptomatic adult women with an established RUTI diagnosis. Participants contributed both midstream voided and catheterized urine specimens for culture via both standard urine culture (SUC) and EQUC. Presence and abundance of microbiota were compared between culture and collection methods.

Results.

43 symptomatic women participants (mean age 67 years) contributed specimens. Compared to SUC, EQUC detected more unique bacterial species and consistently detected more uropathogens from catheterized and voided urine specimens. For both collection methods, the most commonly detected uropathogens by EQUC were E. coli (catheterized: n=8, voided: n=12) and E. faecalis (catheterized: n=7, voided: n=17). Compared to catheterized urine samples assessed by EQUC, SUC often missed uropathogens and culture of voided urines by either method yielded high false positive rates.

Conclusion.

In women with symptomatic RUTI, SUC and assessment of voided urines has clinically relevant limitations in uropathogen detection. These results suggest that, in this population, catheterized specimens analyzed via EQUC provides clinically relevant information for appropriate diagnosis.

Keywords: enhanced urine culture, recurrent urinary tract infection, urine collection, urinary microbiome, urinary pathogen detection

Brief Summary:

In women with symptomatic RUTI, clinicians receive the most clinically relevant information when a catheterized urine sample is analyzed using expanded quantitative urine culture.

INTRODUCTION

Recurrent urinary tract infections (RUTI) are disruptive to affected women, detracting from the quality of their lives and leading to multiple systemic antibiotics exposures. [1] The generally accepted definition of RUTI is symptomatic culture-proven UTI events occurring twice in six months, or three times in one year. [2,3] Typically, the culture technique used to confirm the diagnosis of UTI is assessment of voided urine by standard urine culture (SUC) [2], a laboratory technique originally designed to culture Escherichia coli to assess risk of pyelonephritis during pregnancy. [4,5] As such, the well-established SUC preferentially grows Enterobacteriaceae, most often E. coli. [6] While this method may be suitable for diagnosis of infrequent and uncomplicated UTI in young women [6,7], it has not been validated for adult women with infrequent UTI or RUTI patient populations.

Since women with confirmed clinical history of RUTI are frequently exposed to antibiotic treatment without complete disease resolution, the role of specific uropathogen identification in women with RUTI is critical for targeted antibiotic therapy and adherence to the principles of antibiotic stewardship. Thus, urine cultures are particularly important for clinicians caring for women affected by RUTI. Expanded quantitative urine culture (EQUC) is an enhanced urine culture technique shown to reproducibly detect more uropathogens than SUC in symptomatic populations. [6] This is because EQUC utilizes larger urine volumes, more diverse growth conditions, and longer incubation times than SUC. The underlying etiology of RUTI is unknown; however, the cyclic nature of this condition suggests that uropathogens may persist within the bladder between UTI episodes [8] but often SUC does not detect them.

Finding the balance between pragmatic specimen collection and precision diagnostic testing can be challenging. The ease of midstream voided urine collection is offset by the poor suitability of such a specimen for understanding the bacterial community within the bladder. The difference in microbial composition between paired catheterized and voided urines is well established: whilst transurethral catheterization samples the bladder directly, voided urine samples the entirety of lower urogenital tract. Recently, our team showed that voided urine is not simply a combination of bladder and urethral microbiota, but instead more closely resembles vulvovaginal skin. [9] This implies that voided urine is not well-suited for diagnosis of lower urinary tract conditions.

Transurethral catheterization for specimen collection is burdensome to patients and their clinicians; therefore, it is not pragmatic in many clinical situations. However, as the risks of inappropriate antibiotic use become more clear, judicious use of antibiotic therapy is necessary to improve patient symptoms without increased antimicrobial resistance. It is incumbent upon prescribers to consider the risk-benefit ratio of UTI antibiotics for each individual woman. Thus, the aim of this study was to characterize the urinary microbiota of women with RUTI while comparing methods of urine collection (catheterized vs midstream voided) and culture (EQUC vs SUC) for uropathogen detection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Following IRB approval, adult women 18 years or older with a documented diagnosis of RUTI (≥3 symptomatic SUC-positive UTIs in one year or 2 in six months) seeking treatment for lower urinary tract symptoms at the University of California San Diego Health’s Women’s Pelvic Medicine Center were invited to participate in this IRB-approved study (Protocol Number: 170077AW). We excluded women with known anatomic abnormalities of the urogenital tract, women with neurologic or immunologic disease, women with a history of bladder malignancy, or women with infection unrelated to previously diagnosed urinary tract disorders. Consented, enrolled participants permitted abstraction of demographics and infection history from their electronic medical record and completed a brief survey of their life-time infection history; current urinary symptoms were obtained on the day of specimen collection (manuscript forthcoming).

Participants contributed both a midstream voided (hereafter referred to as voided) and a catheterized urine specimen on a single collection day. Voided urines were collected first via the standard “clean catch” protocol. Participants were instructed to wash their hands with soap and water, use a sterilizing peri-urethral wipe, discard the initial urine stream, and then collect midstream urine into a sterile Becton Dickinson (BD) Vacutainer cup. Catheterized urine specimens were then collected by standard methods: the urethral meatus was prepped with a routine betadine swab before a sterile Bard Clean-Cath Ultra 6” female catheter, 14Fr was placed into the urethra and advanced until urine was returned. Urine specimens were collected in a sterile BD Vacutainer. Aliquots of midstream voided and catheterized urines were immediately transferred to a gray-top tube containing boric acid and refrigerated for preservation. Urine specimens were shipped overnight on ice packs to Loyola University Chicago Department of Microbiology and Immunology for culture and further analysis.

The urine specimens were cultured with both SUC and streamlined EQUC (hereafter referred to as EQUC) as described previously. [7] Table S1 compares the conditions for these two culture methods. After incubation, each morphologically distinct colony type in both SUC and EQUC procedures was counted and isolated on a different plate of the same medium to prepare a pure culture that was used for identification with Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of Flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectroscopy. MALDI Biotyper 3.0 software Realtime Classification was used to analyze the specimens. A Realtime Classification log score was given for each bacterial isolate specimen for every condition from which it was isolated. In the Realtime Classification program, log score identification criteria were set as follows: a score between 2.000 and 3.000 was species-level identification, a score between 1.700 and 1.999 was genus-level identification, and a score below 1.700 was an unreliable identification. Thus, isolates with a log score below 1.700 were classified as “unknown.” Culture results were analyzed for microbiota presence and abundance. Existing literature was used to classify identified urinary microbiota into three groups based on association with UTI [7,10–14]: 1) known to be positively associated (UTI-associated), (2) known to be not positively associated (not UTI-associated), or (3) unknown association (unknown UTI-associated) (Table S2).

Using both SUC and EQUC results, comparisons were made between the catheterized urine specimen (which samples the microbiota of the bladder) and the voided urine specimen (which also includes microbiota from the lower urogenital tract). This resulted in 4 culture/collection combinations: SUC/Cath, SUC/Void, EQUC/Cath and EQUC/Void. Because EQUC is more sensitive than SUC and catheterized urine directly samples the bladder, we then used the EQUC/Cath specimens as the reference standard to compare detection of the three groups of microbes, as defined above. The results of these combinations were categorized into seven detection groups (Table 1). A culture was considered “true negative” if both the culture/collection combination (comparator) and the EQUC/Cath cultures were negative (or only positive for not UTI-associated microbes) or “negative for UTI-associated microbes” if both the comparator and the EQUC/Cath cultures were negative for UTI-associated microbes. A culture was considered “complete detection” if the comparator and EQUC/Cath cultures were identical, “over detection” if the comparator had more UTI-associated microbes than the EQUC/Cath culture, “partial detection” if the comparator missed UTI-associated microbes found in the EQUC/Cath culture, “missed Detection” if the comparator detected none of the UTI-associated microbes detected by the EQUC/Cath culture, and “false positive” if the comparator detected UTI-associated microbes not detected by the EQUC/Cath culture. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive, and negative predictive values were calculated for culture/collection modalities. Statistical analysis was performed in RStudio (Boston, MA), Chi-square or Fisher’s Exact tests were used to test for significance.

Table 1.

Definitions Used for Culture Classification

| Classification | Description |

|---|---|

| True Negative Culture | Comparator culture and EQUC/Cath were both negative (or only positive for not UTI-associated microbes) |

| Negative for UTI-Associated Microbes | Comparator culture and EQUC/Cath were both negative for UTI-associated microbes |

| Missed Detection | Comparator culture was negative for at least one UTI-associated microbe identified by EQUC/Cath |

| Partial Detection | Comparator culture identified one UTI-associated microbe detected by EQUC/Cath but not all |

| Complete Detection | Comparator culture identified the same UTI-associated microbes as EQUC/Cath |

| Over Detection | Comparator culture identified more UTI-associated microbes than EQUC/Cath culture, but included a UTI-associated microbe identified by EQUC/Cath |

| False Positive | Comparator culture identified UTI-associated microbes when EQUC/Cath was negative |

RESULTS

Forty-three symptomatic women with an active clinical diagnosis of RUTI contributed 43 catheterized and 42 voided urine specimens; one participant was unable to provide a voided urine specimen. Most participants were postmenopausal (84%) with an average age of 67 years (Table 2). The cohort reported having RUTI for an average of 11 years with an average of 7 UTIs reported in the last year. At the time of specimen collection, nine women were using daily antibiotic prophylaxis. In those women who were not taking daily prophylactic antibiotic for RUTI prevention (n=34), the average time since last antibiotic use was 33 days. Half the cohort was currently using vaginal estrogen (51%) and half reported they were currently sexually active (51%).

Table 2.

Demographics of Recurrent UTI Cohort

| Age, mean years (SD) | 67.1 (14.2) |

| BMI, mean kg/m2(SD) | 26.9 (6.3) |

| Postmenopausal status, n (%) | 36 (83.7) |

| Parity, median (range)a | 2 (0–4) |

| Vaginal estrogen use, n (%)a | 22 (51.2) |

| Currently sexually active, n (%) | 22 (51.2) |

| UTI History: | |

| Time since last antibiotic use, days (SD)b | 32.8 (40.2) |

| Daily prophylactic antibiotic use, n (%)b | 9 (20.9) |

| Duration of RUTI, years (SD)c | 10.9 (17.4) |

| Lifetime number of UTI, n (SD)d | 48.8 (124.9) |

| Average number of UTIs in the past year, n (SD)e | 7.2 (4.6) |

| Relevant Comorbidities: | |

| Fecal incontinence, n (%) | 7 (16.3) |

| Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, n (%) | 6 (13.9) |

| Overactive bladder, n (%)a | 13 (30.2) |

| Relevant Surgical History | |

| Hysterectomy, n (%) | 20 (46.5) |

| Mesh surgery, n (%) | 8 (18.6) |

| Midurethral sling, n (%) | 6 (13.9) |

One participant did not respond to this question.

Two participants did not respond to this question.

Six participants did not respond to this question.

Twelve participants did not respond to this question.

Nine participants did not respond to this question.

The proportion of specimens with detection of UTI-associated microbes, not UTI-associated microbes, and microbes with unknown UTI-association, as well as the proportion of specimens with no growth, differed by urine collection and culture method (Table 3). The proportion of cultures with detected UTI-associated or unknown UTI-associated microbes varied by specimen type; voided specimens had higher UTI-associated microbe-positive culture rates compared to catheterized specimens, regardless of culture method. For UTI-associated microbes, the proportion of positive cultures differed by specimen type (catheterized: EQUC=53.5% and SUC=39.5%; voided: EQUC=90.5% and SUC=57.1%). For unknown UTI-associated microbes, the proportion of positive cultures also differed by specimen type (catheterized: EQUC=11.6% and SUC=0%; voided: EQUC=66.7% and SUC=26.2%). The detection rate of not UTI-associated microbes also depended on culture method for both catheterized (EQUC=16.3% vs SUC=2.3%) and voided (EQUC=47.6% vs SUC=2.4%) specimens. Finally, the proportion of cultures without growth differed between collection and culture methods with reduced no growth cultures when using EQUC (catheterized=39.5% and voided=4.8%) compared to SUC (catheterized=65.1% and voided=28.6%).

Table 3.

Frequency of Positive Cultures by Microbe Detecteda

| Detection Frequency (%) (n) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture/Collection | UTI-Associated | Unknown UTI-Associated | Not UTI-Associated | No Growth |

|

EQUC/Cath

(N=43) |

53.5% (23) |

11.6% (5) |

16.3% (7) |

34.9% (15) |

|

SUC/Cath

(N=43) |

39.5% (17) |

0% (0) |

2.3% (1) |

65.1% (28) |

|

EQUC/Void

(N=42) |

90.5% (38) |

66.7% (28) |

47.6% (20) |

4.8% (2) |

|

SUC/Void

(N=42) |

57.1% (24) |

26.2% (11) |

2.4% (1) |

28.6% (12) |

Frequency of culture-positive samples for each microbe type; some samples were culture-positive for more than one microbe type.

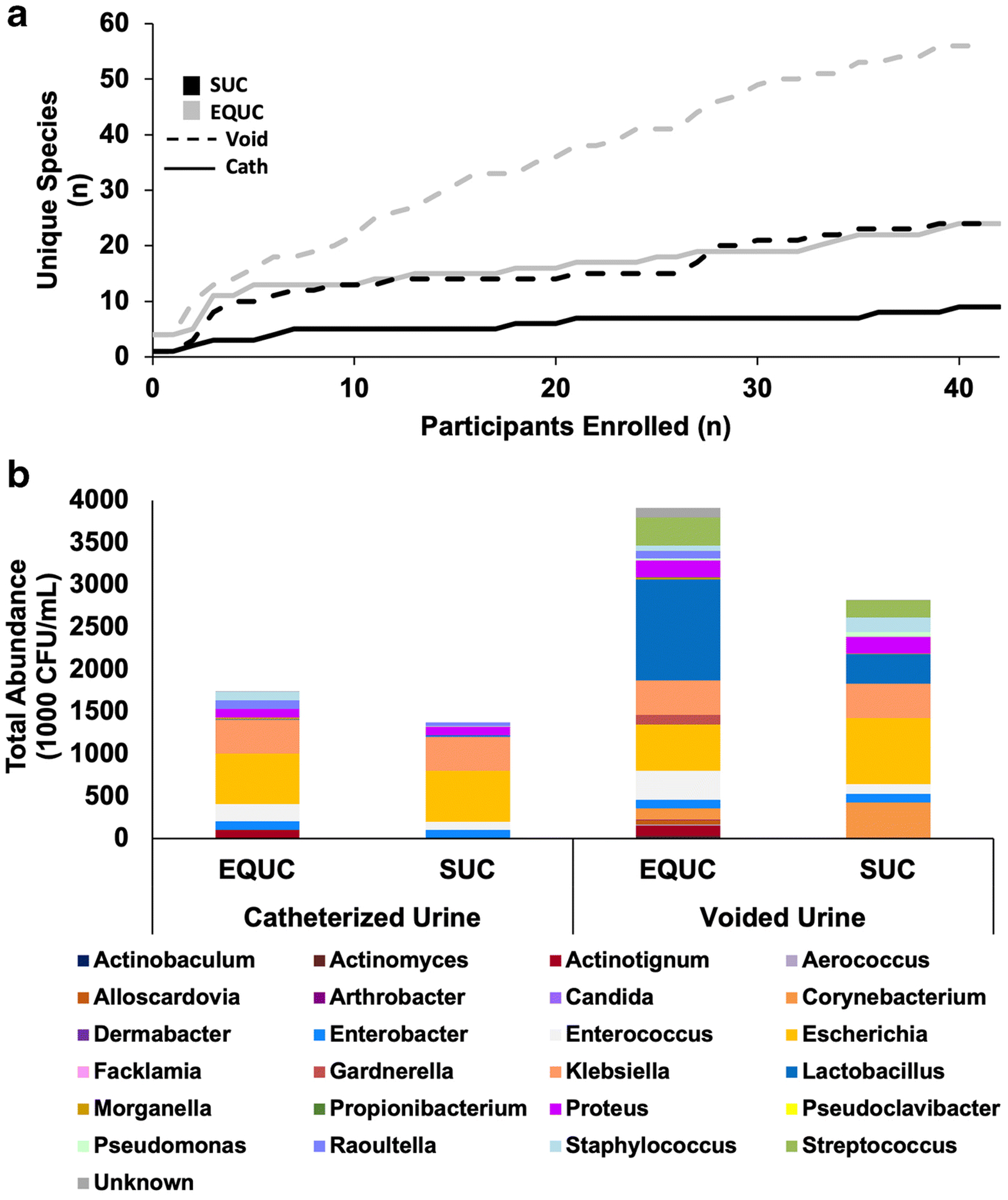

More unique bacterial species were detected by EQUC in both catheterized (EQUC=24 vs SUC=9) and voided ( EQUC=56 vs SUC=24) specimens (Table S3, Figure 1A). For example, the UTI-associated microbes Actinotignum schaalii and Streptococcus anginosus were detected only by EQUC. Similarly, EQUC detected microbiota at higher abundances from both specimen types (Figure 1B). Similarly, voided specimens were more diverse than catheterized specimens, with an increased detection frequency of total unique species and UTI-associated microbes, such as Enterococcus faecalis, E. coli, and S. anginosus. Some of the species detected in voided specimens were not detected in catheterized specimens (Table S3, Figure 1B). For example, Aerococcus urinae and Corynebacterium amycolatum were cultured only from voided urine.

Figure 1. Comparison of total microbiota detected by urine collection and culture method.

A) Rarefaction curve demonstrating the cumulative number of unique species detected (Y-axis) per participant (X-axis). Results are shown for catheterized (solid lines) and voided (dashed lines) urine samples cultured via SUC (black) and EQUC (gray). B) Cumulative microbiota profiles of all catheterized (N=43) and voided (N=42) urine samples cultured via SUC and EQUC. Total abundance (cumulative CFU/mL, Y-axis) of each genus detected is displayed for each urine collection and culture method.

The distribution of the most frequently detected microbes varied by culture and collection type. For catheterized specimens that were cultured by EQUC, the most frequently detected UTI-associated microbes were E. coli (n=8), E. faecalis (n=7), Klebsiella pneumoniae (n=4) and S. anginosus (n=3) (Table S3). In comparison, the most frequently detected UTI-associated microbes in catheterized specimens that were cultured by SUC were E. coli (n=6), K. pneumoniae (n=3) and E. faecalis (n=2). In voided specimens cultured by EQUC, the most frequently detected UTI-associated microbes were E. faecalis (n=17), E. coli (n=12), S. anginosus (n=11), and A. urinae (n=9). When voided specimens were cultured by SUC, the most frequently detected UTI-associated microbes were E. coli (n=8), E. faecalis (n=6) and K. pneumoniae (n=5).

Clear discrepancies in detection of UTI-associated microbes existed between the culture and collection methods (Table 4). Since catheterized urine samples the bladder directly and EQUC detected a higher frequency of UTI-associated microbes than SUC, the EQUC/Cath combination was used as the comparator. True negative rates, or no growth cultures, were highest in catheterized urines (EQUC=34.9% and SUC=34.9%) and were reduced in voided urines (EQUC=2.4%, SUC=19.1%). Rates of negative for UTI-associated microbes were similar for all combinations. The EQUC/Cath combination resulted in UTI-associated microbe detection from 23 samples (53.5%). Total detection of these UTI-associated microbes, or complete agreement with EQUC/Cath, was reduced in the SUC/Cath combination (23.3%) and in voided urines cultured by either method (EQUC=9.5% and SUC=26.2%). In terms of missed and partial detection of UTI-associated microbes, SUC of either urine type resulted in the highest rates of missed (catheterized=23.3% and voided=6.9%) and partial microbe detection (catheterized=16.7% and voided=7.1%). However, the SUC/Cath combination resulted in no UTI-associated microbe over detection or false positives, meaning no additional UTI-associated microbes were detected in comparison to EQUC/Cath. Culture of voided urine by either method yielded increased UTI-associated microbe over detection (EQUC=33.3% and SUC=2.4%) and false positives (EQUC=42.9% and SUC=16.7%).

Table 4.

Culture Distribution

| EQUC/Cath | SUC/Cath | SUC/Void | EQUC/Void | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| True Culture Negative | 15 (34.9%) | 15 (34.9%) | 8 (19.1%) | 1 (2.4%) |

| Negative for UTI-Associated microbes | 5 (11.6%) | 5 (11.6%) | 5 (11.9%) | 1 (2.4%) |

| Missed Detection | - | 10 (23.3%) | 7 (16.7%) | 2 (4.8%) |

| Partial Detection | - | 3 (6.9%) | 3 (7.1%) | 2 (4.8%) |

| Total Detection | 23 (53.5%) | 10 (23.3%) | 11 (26.2%) | 4 (9.5%) |

| Over Detection | - | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.4%) | 14 (33.3%) |

| False Positive | - | 0 (0%) | 7 (16.7%) | 18 (42.9%) |

| Total | 43 (100%) | 43 (100%) | 42 (100%) | 42 (100%) |

For UTI-associated microbes, Table 5 displays the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive, and negative predictive values for each collection/culture method combination as compared to the EQUC/Cath combination. The SUC/Cath combination had highest specificity (1) and positive predictive value (1), but had the lowest sensitivity (0.57). In contrast, the SUC/Void combination had slightly higher sensitivity (0.68), but lower specificity (0.65) and positive predictive power (0.68). The EQUC/Void combination had high sensitivity (0.91), but low positive predictive power (0.53) and very low specificity (0.1).

Table 5.

Sensitivity and Specificity by Urine Collection and Culture Method Compared to EQUC of Catheterized Urine

| SUC/Cath | EQUC/Void | SUC/Void | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 0.57 | 0.91 | 0.68 |

| Specificity | 1 | 0.1 | 0.65 |

| Positive Predictive Value | 1 | 0.53 | 0.68 |

| Negative Predictive Value | 0.66 | 0.50 | 0.65 |

DISCUSSION

Combined, our findings provide a description of the urinary microbiota isolated from this RUTI population and demonstrates how microbiota profiles differ with urine collection and culture methods. These differences have the potential to impact patient care by causing under-treatment or over-treatment and, therefore, negatively affect clinical outcomes. EQUC consistently detected more UTI-associated microbes than SUC from the same urine samples, and a key finding of this study is that catheterized urine specimens assessed by EQUC yielded the highest sensitivity with detection of more than twice the number of UTI-associated microbes from voided urine than from the paired catheterized urine. Furthermore, certain microbes were detected exclusively by EQUC (A. schaalii, Candida species, and S. anginosus).

This study also provides evidence that non-E.coli, non-Enterobacteriaceae UTI-associated microbes may be more prevalent in RUTI populations than previously thought. In this population of women with RUTI, we found that E. faecalis was the most prevalent UTI-associated microbe, consistent with earlier reports that recognize E. faecalis as a possible underlying cause for RUTI. [14,15] This finding sets RUTI apart from infrequent UTI, which is most often related to E. coli infection. [7] While E. faecalis is not as familiar to clinicians as E. coli, it is worth considering that E. faecalis has biologic behaviors that include the ability to readily invade human urothelial cells in human bladder organoids, whereas E. coli isolated from a similar population do not. [14,16]

The reason why women with RUTI have a heightened susceptibility to frequent UTI events is not known. However, some affected women have documentation of the same UTI-associated microbe for multiple episodes, leading investigators to hypothesize that these microbes persist within the bladder between UTI episodes. [17] Thus, the high prevalence of E. faecalis is important, given formation of intracellular bacterial communities is now considered an etiologic factor in certain lower urinary tract symptoms. [8] If the E. faecalis strains isolated in the current study have the capacity to invade urothelial cells, it is likely that they can persist intracellularly between clinically recognized infections. The superior detection of E. faecalis by EQUC strongly supports the use of this culture technique for women with RUTI.

An additional key finding is the detection of unique bacterial species at higher frequency and abundance by EQUC. However, EQUC detected some microbes, notably A. schaalii and S. anginosus, only in voided urine. This finding raises the possibility that some microbes may persist in urethral or peri-urethral reservoirs in women with RUTI. This possibility is supported by Chen and co-workers who characterized the microbiota of the female urethra, providing evidence that many species are preferentially isolated with similar frequencies from voided urine and urethral specimens relative to catheterized urine. [9] Since many of the species detected in this study are the same as those of the Chen et al. study, we believe the isolation of these microbes are likely to be clinically relevant, i.e. associated with the urethra, and not indicative of contamination.

A strength of this study is the design, which allowed us to directly compare the efficacy of each culture method by culturing paired urine specimens via EQUC and SUC for all participants. Another strength is that we did not use standard clinical reporting practices for either culture method; instead, we isolated and identified each distinct morphology and reported the result regardless of standard colony forming unit threshold criteria. By reporting microbe detection regardless of threshold cutoffs, we effectively removed reporting biases that favor fast growing, non-fastidious organisms, such as E. coli.

Our findings are limited by the lack of a non-affected comparison cohort, as we only included women with a confirmed history of RUTI. Although all study participants reported urinary symptoms, the study has heterogeneity based on the severity lower urinary tract of symptoms. Also, this study recruited a small sample of women with RUTI from a single clinical site specializing in RUTI; therefore, these results may not be generalizable to other geographically distinct patient populations but instead are reported to help inform future studies on larger RUTI populations. Finally, this study utilized a standard clinical, clean catch technique to collect voided urines. It is well documented that this method produces specimens that contain large numbers of microbes that originate from the vulva and vagina. [18–20] A recently published study reported that the cultured microbes of voided urines obtained by the clean catch technique often resemble the cultured microbes of peri-urethral skin. [9] Urethral and peri-urethral swabs can confirm the presence of UTI-associated microbes in these niches; such additional assessments should be considered in future studies.

Conclusions:

A variety of mechanisms for microbe persistence in patients with RUTI have been proposed, including antibiotic resistance [21], establishment of intracellular bacterial communities [8,22–24], biofilms [25], or ineffective therapy for prior UTI episodes. [26,27] The current clinical treatment algorithm does not include clinical tests that confirm either the presence of intracellular bacterial communities or biofilms. Thus, clinicians must rely on clinically available urine collection methods (catheterized vs voided) and culture methods (SUC or EQUC, if available in their clinical laboratory).

Our findings document important clinical patterns in women with RUTI and highlight the clinical impact of urine specimen and culture technique selection. In women with RUTI, clinical diagnosis may be enhanced by judicious use of catheterized specimens and/or EQUC testing to minimize poor clinical outcomes associated with a failure to detect and treat UTI-associated microbes such as E. faecalis, a microbe that is associated with RUTI, yet not reliably detected by SUC. As our understanding of RUTI etiology improves, enhanced prevention and treatment algorithms are likely to improve targeted therapy that reduces both the personal impact of repetitive, systemic antibiotics on individual affected women and rising prevalence of microbial antibiotic resistance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding by NIH/NICHD R01 DK104718 (Drs. Wolfe and Brubaker) for support for the conduct of this research. For this study, no funding, supplies, or services were received from any commercial organization.

Conflicts of Interest:

Dr. Wolfe discloses research support from the NIH, the DOD and Kimberly Clark Corporation. He also discloses membership on the Scientific Advisory Boards of Pathnostics and Urobiome Therapeutics. Dr. Brubaker discloses research funding from NIH and editorial stipends from Female Pelvic Medicine & Reconstructive Surgery, UpToDate and JAMA. The remaining authors report no disclosures.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Presentation: Portions of this work have been presented at AUGS Virtual PFD Week Meeting 2020 October 7–10, 2020

REFERENCES

- 1.Aslam S, Albo M, Brubaker L. Recurrent urinary tract infections in adult women. JAMA. 2020;323(7):658–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaitonde S, Malik RD, Zimmern PE. Financial burden of recurrent urinary tract infections in women: a time-driven activity-based cost analysis. Urol. 2019;128:47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, Swift SE, Berghmans B, Lee J, Monga A, Petri E, Rizk DE, Sand PK, Schaer GN. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. International Urogynecology J, 2010,21:5–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kass EH. Asymptomatic infections of the urinary tract. Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1956;69:56–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kass EH. Bacteriuria and the diagnosis of infections of the urinary tract; with observations on the use of methionine as a urinary antiseptic. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1957;100(5):709–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Price TK, Hilt EE, Dune TJ, Mueller ER, Wolfe AJ, Brubaker L. Urine trouble: should we think differently about UTI? Int Urogynecol J. 2017;29(2)205–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Price TK, Dune T, Hilt EE, et al. The Clinical Urine Culture: Enhanced techniques improve detection of clinically relevant microorganisms. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54(5):1216–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scott VC, Haake DA, Churchill BM, Justice SS, Kim JH. Intracellular bacterial communities: a potential etiology for chronic lower urinary tract symptoms. Urol. 2015;86(3):425–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen YB, Hochstedler B, Pham TT, Alvarez MA, Mueller ER, Wolfe AJ. The urethral microbiota: a missing link in the female urinary microbiota. J Urol. 2020;204(2):303–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kline KA, & Lewis AL Gram-positive uropathogens, polymicrobial urinary tract infection, and the emerging microbiota of the urinary tract. Microbiol Spectr. 2016;4(2): 10.1128/microbiolspec.UTI-0012-2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khoshnood S, Heidary M, Mirnejad R, Bahramian A, Sedighi M, Mirzaei H. Drug-resistant gram-negative uropathogens: a review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;94:982–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fisher JF, Kavanagh K, Sobel JD, Kauffman CA, Newman CA. Candida urinary tract infection: pathogenesis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(suppl_6): S437–S451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whiteside SA, Razvi H, Dave S, Reid G, Burton JP. The microbiome of the urinary tract—a role beyond infection. Nat Rev Urol. 2015;12(2):81–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerber D, Forster CS, Hsieh M. The role of the genitourinary microbiome in pediatric urology: a review. Curr Urol Rep, 2018;19(1):13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horsley H, Malone-Lee J, Holland D, et al. Enterococcus faecalis subverts and invades the host urothelium in patients with chronic urinary tract infection. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e83637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whiteside SA, Dave S, Seney SL, Wang P, Reid G, Burton JP. Enterococcus faecalis persistence in pediatric patients treated with antibiotic prophylaxis for recurrent urinary tract infections. Future Microbiol. 2018;13:1095–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horsley H, Dharmasena D, Malone-Lee J, Rohn JL. A urine-dependent human urothelial organoid offers a potential alternative to rodent models of infection. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kodner CM, Thomas Gupton EK. Recurrent urinary tract infections in women: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:638–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lifshitz E, Kramer L. Outpatient urine culture: does collection technique matter? Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(16):2537–2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baerheim A, Digranes A, Hunskaar S. Evaluation of urine sampling technique: bacterial contamination of samples from women students. Br J Gen Pract. 1992;42(359):241–243. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Southworth E, Hochstedler B, Price TK, Joyce C, Wolfe AJ, Mueller ER. A cross-sectional pilot cohort study comparing standard urine collection to the Peezy Midstream Device for research studies involving women. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2019;25(2):e28–e33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waller TA, Pantin SAL, Yenior AL, Pujalte GGA. Urinary tract infection antibiotic resistance in the United States. Prim Care. 2018;45(3):455–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirakawa H, Suzue K, Kurabayashi K, Tomita H. The Tol-Pal system of uropathogenic Escherichia coli is responsible for optimal internalization into and aggregation within bladder epithelial cells, colonization of the urinary tract of mice, and bacterial motility. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson GG, Palermo JJ, Schilling JD, Roth R, Heuser J, Hultgren SJ. Intracellular bacterial biofilm-like pods in urinary tract infections. Sci. 2003;301:105–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wright KJ, Seed PC, Hultgren SJ. Development of intracellular bacterial communities of uropathogenic Escherichia coli depends on type 1 pili. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9(9):2230–2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tapiainen T, Hanni AM, Salo J, Ikäheimo I, Uhari M. Escherichia coli biofilm formation and recurrences of urinary tract infections in children. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33(1):111–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Durkin MJ, Keller M, Butler AM, Kwon JH, Dubberke ER, Miller AC, Polgreen PM, Olsen MA. An assessment of inappropriate antibiotic use and guideline adherence for uncomplicated urinary tract infections. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018;5(9):ofy198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zalewska-Piątek BM, Piątek RJ. Alternative treatment approaches of urinary tract infections caused by uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains. Acta Biochim Pol. 2019;66(2):129–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.