Abstract

Interactions between microorganisms in multispecies communities are thought to have substantial consequences for the community. Identifying the molecules and genetic pathways that contribute to such interplay is thus crucial to understand as well as modulate community dynamics. Here I focus on recent studies that utilize experimental systems biology techniques to study these phenomena in simplified model microbial communities. These unbiased biochemical and genomic approaches have identified novel interactions, and described the underlying genetic and molecular mechanisms. I discuss the insights provided by these studies, describe innovative strategies used to investigate less tractable organisms and environments, and highlight the utility of integrating these and more targeted methods to comprehensively characterize interactions between species in microbial communities.

Keywords: Interspecies interactions, Experimental genome-scale approaches, Microbial communities

Strategies for investigating interspecies interactions

It has been known for centuries that different microorganisms live in close proximity [1], and current understanding indicates that microbial species rarely exist in isolation [2]. In polymicrobial communities, microorganisms interact with each other, and similar to animal societies, these interactions range from antagonistic to cooperative behaviors [3]. Such interplay is a major driver of the composition dynamics of multispecies communities, affecting how communities assemble, evolve, and are maintained over time. These communities include the microbiota associated with soil and aquatic environments, as well as plant, animal and human bodies [2]. Due to the critical importance of such communities to human health and economy, the factors that shape their structure, including interspecies interactions, remain an active area of study.

A common first approach for studying multispecies communities is metagenomic cataloguing of the constituent species, and gene-encoded functions, under varying conditions, exemplified by microbiome characterization in human health and disease [4–6] (Box 1). Metagenomic sequences and annotations, as well as experimental data, have been used as inputs for computational systems biology approaches including genome-scale metabolic reconstruction to not only better describe complex natural communities and interactions therein, but also to generate predictive models for phenotypes and interactions under specific conditions [7] (Box 2). A more biochemical view is provided by proteomic and metabolomic characterization of communities which uncovers the proteins and metabolites that are produced, providing insights into the functional and metabolic capacity of the community [8]. Functional genomics screens can further link the metagenomic composition to bioactivities present in the community [9, 10]. These strategies aim to describe microbial communities in their native context at a taxonomic, genomic, functional, and ecological level.

Box 1. Metagenomic techniques for characterizing multispecies communities.

Metagenomic methods aim to better understand complex native communities both in terms of the species present and the functional capacity. These studies include metagenomic sequencing studies in which DNA from multispecies communities is subjected to either 16S rRNA sequencing to taxonomically define the microbial community under different conditions, or shotgun sequencing, possibly in conjunction with genome assembly, to identify both the microbial species present, as well as their metabolic capabilities. Such analyses have described various environmental communities [4, 6], and identified changes in the human microbiome associated with numerous disease states [5]. Further, computational pipelines have been developed that analyze bacterial and fungal genomes to identify biosynthetic gene clusters of secondary metabolites [53]. Orthogonally, functional metagenomic screens help to reveal novel bioactivities present in microbial communities, and their biosynthetic pathways. For such screens, metagenomic libraries are constructed using DNA extracted from polymicrobial environments, and clones are then selected based on phenotypes of interest, such as specific enzymatic activities, production of antimicrobials, antimicrobial resistance, as well as more complex phenotypes including combinations of molecules [54–57]. The sequence of the selected clones can reveal the genes or biosynthetic pathways essential for production of the molecules of interest, and can often be mapped back to the species of origin. However, such studies rarely focus on either identifying, or mechanistically characterizing, specific interactions between defined species.

Box 2. Computational modeling techniques for studying microbial communities.

Genome-scale metabolic reconstruction and modeling based on genome sequences, annotations, flux balance analysis, and experimental data, have been used to better understand a variety of biological processes, including interspecies relationships in communities [7]. Metabolic network models have been used to predict the metabolic competition vs complementarity between human microbiome species based on their nutrient requirements from the environment [58]. Such analysis has suggested that the dominant force that explains the community composition of the human microbiome at different sites is habitat filtering, where the environment selects for species with converging traits. Similar results were also seen in a broader set of communities including those from the soil, water and the human gut, although co-occurring subcommunities of up to 4 species showed strong metabolic interdependency and mutualism [59]. A recent study extended such analysis to co-occurring groups of up to 40 species in thousands of communities from diverse environments, and discovered that such groups are polarized on the competition-cooperation spectrum [60]. Further, members of the two group types are associated with specific characteristics, such that the cooperative communities have species with fewer metabolic genes, higher nutrient requirements (mainly amino acids), and more metabolic network dissimilarity and phylogenetic divergence, and are more sensitive to the introduction of foreign species, whereas the competitive communities exist mostly in free-living environments and are more sensitive to changes in nutrient availability. Modeling approaches can also factor in other parameters such as constraints including oxygen levels and diverse diets to identify conditional interactions [61], temporal and spatial dynamics to predict interactions within communities in physical structures such as biofilms over time [62], and constraints on metabolic capacity yielding pathway configurations with complex division of metabolic labor between species even in simple multi-strain communities [63]. Computational systems biology approaches can thus help to extend insights obtained from experimental studies in simple multispecies systems to better understand and predict interactions within complex natural communities.

An orthogonal approach has been to devise model multispecies systems more amenable to genetic and biochemical manipulation, to identify interactions between microbial species, and the underlying molecules, genes, and cellular pathways. Some studies have described the effect of previously identified molecules on complex communities or some of the constituent species in isolation [11–13]. Others have focused on a few dominant species present in native communities to identify potential interplay between them [14, 15]. However, the mechanisms underlying microbial interactions, including the sensing of foreign species and the cellular response, the regulation of secreted molecular mediators, their mode of action, and the genetic pathways necessary for the interactions, remain poorly characterized.

In recent years, experimental genome-scale unbiased approaches have been utilized to mechanistically characterize microbial interactions at a genetic and molecular level in defined model multispecies communities. Commonly investigated systems include co-infecting pathogens [16, 17], pathogens and commensals likely to interact at infection sites [18, 19], environmental microbial communities including those present in the soil [4], and communities associated with fermented foods (Box 3) [20]. Studies using experimental systems biology approaches start either from a previously identified interaction or from a phenotypic screen testing the hypothesis that interplay exists between microbial species found in communities, and typically focus on a few dominant community members that have been previously identified. Instead of then testing pathways predicted to drive the interactions, the strategy is to query on a genome-scale all possible pathways and molecules that may influence the interaction, and then focus on the specific ones that show an effect (Box 4).

Box 3: Commonly studied microbial communities.

Oral microbiota:

The oral cavity has a diverse community of microorganisms likely containing more than 700 species. The composition of this community is thought to change between healthy versus diseased states of the oral cavity, and different species are associated with diseases such as dental caries and periodontitis and are thought to synergistically lead to pathogenesis [18, 64, 65]. Some of the major species associated with disease, that have also been studied in vitro to identify potential mechanisms of interactions with other community members, include P. gingivalis, S. gordonii, A. actinomycetemcomitans, Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus sanguinis, and Candida albicans.

Respiratory pathogens:

Chronic lung infections are associated with diseases such as cystic fibrosis and bronchiectasis, due to impaired mucus clearance [66]. Interplay between microorganisms found in chronic infections is thought to affect disease progression, and the eventual prognosis for patients, especially in cystic fibrosis [67]. Interactions between several of these major respiratory pathogens such as P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, A. fumigatus, and Burkholderia spp. have been studied in vitro.

Environmental communities:

Microbial communities are widespread in natural environments such as terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, and as part of plant microbiomes [4, 68, 69]. Soil microbial communities are among the most diverse in nature and are reservoirs of secondary metabolites that likely mediate interspecies interactions. Diverse subsets of species from such communities have been studied in vitro, the better characterized of which include Myxococcus, Streptomyces, Bacillus and Fusarium species.

Cheese rind biofilm communities:

Multispecies microbial communities are associated with a variety of fermented foods including yogurt, kefir, beer, sourdough and cheese [20, 70, 71]. In recent years, bacterial and fungal species associated with cheese rind biofilms have been developed into an experimentally tractable system to study microbial communities and interactions. These include Staphylococcus and Pseudomonas bacteria, and fungi such as Penicillium, Candida, Fusarium and Scopulariopsis species [72].

Box 4. Experimental omics approaches for studying microbial interactions.

A. Cellular state of microorganisms in communities

Characterization of the molecular state of microorganisms in the presence and absence of other species can reveal the response induced by these species. Such measurements are typically carried out either in planktonic co-cultures or from cells in regions of communication between species on solid surfaces. These analyses can help to elucidate the signals that may be perceived in communities, as well as the resulting response pathways, which often modulate interplay between the species.

Transcriptomics:

RNA is collected from interacting species and is subject to next-generation sequencing. Reads are then mapped back to the genomes to identify the genes and pathways that are upregulated in the presence of other species [27–29, 31, 46].

Metabolomics and proteomics:

Metabolomics and proteomics: MS-based technologies are used to measure either the metabolomic or proteomic content of interacting species and can be combined with imaging for spatial analysis in structured communities. These approaches can define the proteomic and metabolomic responses of species, as well as emergent metabolism and biotransformation, potentially uncovering the molecular basis of interactions [32, 35, 36, 38].

B. Genetic determinants of fitness

Identification of mutations that result in altered fitness of a species in a community, or change in an interaction, can reveal the genetic pathways that modulate multispecies interactions as well as the mechanisms responsible. These pathways can then be targeted to modulate microbial interplay and consequently the composition of communities.

Genomic screens:

A library of genome-wide mutants, frequently generated via transposon insertion, is subjected to screening or a selection to identify mutants with an interaction phenotype. The mutations present are ascertained via sequencing, to reveal the genes critical to the interaction [39–43].

Experimental Evolution:

Independent populations of bacteria are passaged in the presence of either foreign species or exogenous foreign effector molecules to select for populations with increased fitness in communities. Whole-genome sequencing of isolates and populations with increased fitness can reveal major modulators of fitness in multispecies interactions, as well as potential epistatic relationships due to the presence of multiple mutations [44, 46].

Such approaches can not only validate expected mechanisms of interactions (if any), but also identify novel molecules and pathways that have not previously been implicated in such phenomena. These unbiased methods include elucidation of the physiological state of microorganisms in the presence of other species at the level of the transcriptome, proteome, and metabolome, comprehensive identification of molecules produced in multispecies settings, and mapping on a global scale the genes that affect microbial interplay and community composition (Figure 1). This review aims to describe these strategies that have begun to both identify vast networks of interspecies interactions, and to define the underlying mechanisms, typically in simplified microbial communities, that are amenable to well-controlled biochemical and genetic perturbations. I discuss the insights provided by such approaches, and highlight pioneering strategies used to characterize less well-described species and environments. Further, I examine how a combination of these methods complemented by more targeted experiments using defined mutant strains, as well as biochemical and enzymatic assays, can lead to comprehensive characterization of interspecies interactions.

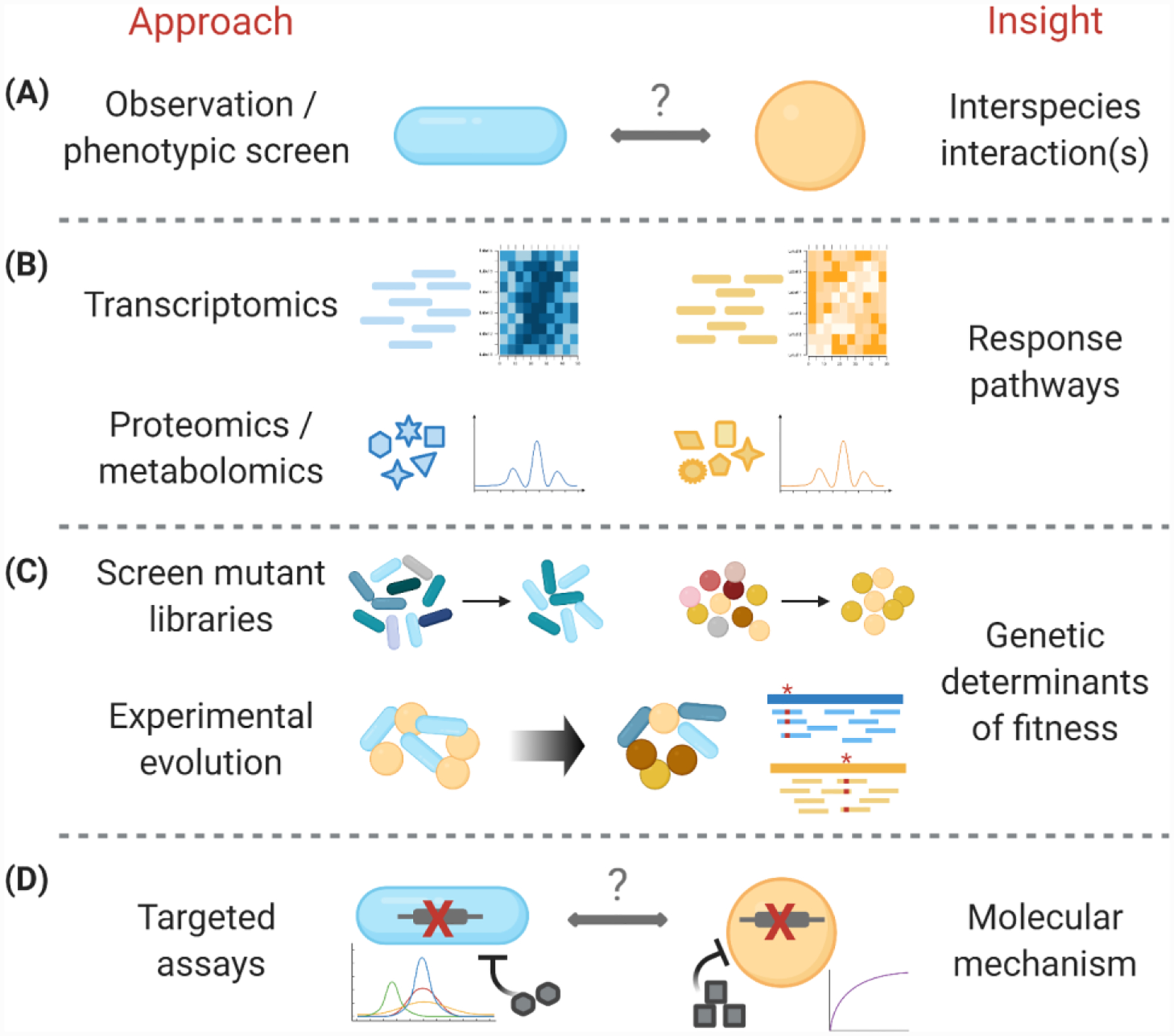

Figure 1. Experimental genome-scale approaches used to dissect microbial interactions.

In recent years, omics technologies have been applied to the study of microbial interactions. (A) Interplay between microbial species is typically identified either by targeted experimental observations or via large-scale phenotypic screens. These interactions can be cooperative such as induction of growth and synergistic pathogenesis, competitive such as growth inhibition or killing, or lead to altered metabolism or lifestyles. (B) Transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic measurements in interacting species can identify whether the species can sense and respond to one another, and molecularly characterize this response. The differentially regulated genetic pathways can reveal the molecules and stresses being sensed due to the foreign species, as well as the cellular pathways that may be important for the interaction. Metabolomic and proteomic measurements define the functional response of interacting species and molecules critical for interplay, and can also uncover novel interactions such as cross-feeding and bioconversion. (C) Genomic screens of mutant libraries can uncover the genes and pathways that significantly affect the interaction or fitness in a multispecies system. Experimental evolution can similarly pinpoint the genes that confer increased fitness in the interaction, as well as delineate adaptive trajectories in the community. (D) These genome-scale approaches can help to design targeted genetic and biochemical assays that validate the molecular mechanisms underlying the microbial interaction.

Physiological state of microorganisms in multispecies communities

A first step towards understanding multispecies model systems has been the characterization of the cellular state of the constituent organisms at the transcriptional, proteomic and metabolomic levels (Figure 1). These methods can reveal the environmental conditions and stresses perceived by a species in a polymicrobial system, metabolic capabilities of, and exchanges between, constituent species, and the mechanisms underlying interactions that shape the community. While several recent analyses have utilized metatranscriptomics, metaproteomics, and metabolomics to better describe complex microbial communities and the ecological relationships between community members in microbiomes, as well as biogas reactor communities, the specific molecules, genes, and pathways that affect interspecies interactions, and the resultant phenotypic changes, in such complex systems are rarely elucidated [21–26]. This review therefore focuses on studies that use these approaches in model multispecies systems, including commensals and pathogens found together in infections, as well as communities found in fermented foods and the soil, to provide molecular insights into interspecies interactions.

Transcriptional profiling using RNA sequencing (RNAseq)

Multispecies communities are prevalent within the oral cavity, and it has been seen that the oral pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis shows increased pathogenicity in the presence of the commensal Streptococcus gordonii in animal models of infection [14]. Transcriptomic measurements in vitro showed that several virulence factors, including adhesins and the type IX secretion system, were induced in P. gingivalis in coculture, potentially contributing to the enhanced pathogenicity, and the oxidative stress response pathway was upregulated in P. gingivalis likely as a response to the H2O2 produced by S. gordonii [27]. Thus, transcriptomic measurements revealed responses to known molecules putatively present in the community and suggested potential mediators of a known interaction.

Transcriptional measurements of the respiratory pathogens Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus in mixed-species biofilms showed that the presence of P. aeruginosa led to the upregulation of fermentation pathway genes in S. aureus [28]. Follow-up experiments confirmed the accumulation of lactate, and showed that P. aeruginosa quinolones and siderophores induced the shift to fermentation in S. aureus, validating the novel metabolic changes caused by this interaction.

Dual RNAseq in a two-species system containing the soil bacteria Streptomyces coelicolor and Myxococcus xanthus grown under standard laboratory conditions revealed that in the presence of the other species, M. xanthus upregulates the production of the siderophore myxochelin, while S. coelicolor induces the production of the antibiotic actinorhodin [29]. Subsequent experiments indicated that S. coelicolor initially outcompetes M. xanthus for iron, inducing the production of myxochelin which chelates iron away from S. coelicolor. The resulting iron scarcity induces the production of actinorhodin, an example of competition sensing where nutrient competition, in this case for iron, leads to the production of antimicrobials [30]. Further, transcriptome measurements in 8 diverse Streptomyces species revealed that iron scarcity induced 21 out of 260 secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters, including several antibiotics, suggesting that competition sensing in response to iron scarcity may be widespread.

Within the cheese rind biofilm, Staphylococcus equorum eventually ends up as the most abundant species, despite being a slow colonizer, and a poor competitor against two other cheese Staphylococcus species in a three-species community grown in vitro on cheese curd agar [31]. Interestingly, the presence of the fungus Scopulariopsis in the in vitro community specifically promotes S. equorum growth, and therefore its dominance. RNAseq suggested that fungal siderophores alleviate the iron requirements of S. equorum and fungal proteases increase the availability of free amino acids, likely resulting in increased growth and community dominance of S. equorum, thus indicating the potential mechanism of the unexpected community dynamics.

Proteomic and metabolomic profiling using mass spectrometry (MS)

Since proteomic and metabolomic profiling techniques are more longstanding technologies (compared with genomic measurements), these approaches have been commonly used to identify and measure metabolites produced in microbial communities [32]. Compared with transcriptional profiling, such analyses reveal even more directly the functional consequences of the response of microorganisms to other species, as they measure changes in proteins and metabolites in and around interacting cells. However, the molecules altered may be harder to identify as the catalog of metabolites and modified proteins is less exhaustive than genomic sequences.

In a three-way interaction, the fungus-associated helper Mycetocola bacteria protect white button mushrooms against the tolaasin toxin produced by the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas tolaasii [33, 34]. MS analysis in vitro indicated that the tolaasin toxin is linearized in co-culture with the helper bacteria, likely explaining the protective effect, and also identified the peptidases responsible for this cleavage [35]. Further, the protective bacteria also linearized a P. tolaasii surfactant, thereby inhibiting swarming of the pathogen and reducing host colonization.

P. aeruginosa strains commonly antagonize S. aureus, but a human host-adapted strain of P. aeruginosa, DK2-P2M23-2003, shows commensal-like interactions with S. aureus in vitro [36]. MS-based analyses revealed that DK2-P2M23-2003 produces specific variants of the 4-hydroxy-2-alkylquinolones (HAQs) at the interface with S. aureus, and mutant analysis showed that HAQs were necessary for the commensal-like interactions. Thus, unlike the more commonly observed phenotype of HAQ molecules antagonizing S. aureus [37], metabolomics identified these uncommon HAQ variants as mediators of proto-cooperation between these species.

In another study, in vitro metabolomic analyses revealed that the co-infecting fungus Aspergillus fumigatus bio-transforms P. aeruginosa phenazine molecules into modified phenazines that trigger the production of specific fungal siderophores and have fungal inhibitory activity, a novel bioconversion with consequences for community composition [38].

Thus, global measurements of cellular macromolecules can reveal changes in the physiological state of microorganisms in multispecies systems, identify novel microbial interactions, and define the underlying molecules and mechanisms, as well as the resulting environmental alterations.

Genetic pathways critical for interspecies interactions

Characterizing microbial interplay in multispecies systems necessitates defining the genes that affect the fitness of the constituent microorganisms. High-throughput functional genomic screens, and experimental evolution, have revealed mutations that differentially affect fitness in polymicrobial compared to monospecies systems, providing insights into interspecies interactions and their molecular mechanisms (Figure 1). Genome-wide screening methods also allow for the identification of changes in gene essentiality in a bacterial species when in the presence of other species. Such studies can identify uncharacterized pathways important for microorganisms in their native environments where they likely exist in multispecies communities, and thus, in the case of pathogens, can define novel targets for the design of antimicrobials.

Functional genomic screening using transposon insertion sequencing (Tn-seq)

Enterococcus faecalis and Escherichia coli are often found together in catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs), and E. faecalis increases the growth of E. coli in mixed-species biofilms [39]. Screening of an E. faecalis transposon library in vitro revealed that an E. faecalis L-ornithine exporter mutation abolished the E. coli growth augmentation. Further, transcriptomic measurements in E. coli showed an upregulation of siderophore biosynthesis in proximity to E. faecalis. Follow-up experiments demonstrated that both E. faecalis-secreted L-ornithine, and the E. coli siderophore enterobactin, were necessary for the increased E. coli growth, thus defining an unexpected metabolic signal leading to cooperation.

The bacterium Proteus mirabilis is found in CAUTIs with Providencia stuartii, and Tn-seq studies from murine coinfection models have revealed that the type VI secretion system is important for both species in co-infection, likely indicative of interspecies competition [40, 41]. Further, P. mirabilis required branched chain amino acid (BCAA) biosynthesis genes only in co-infection suggesting competition for BCAAs, while the two-species system alleviated the requirement for polyamines and zinc in P. mirabilis. Targeted follow-up experiments revealed that high-affinity import of leucine by P. stuartii results in an increased need for BCAA synthesis in P. mirabilis. The unbiased genome-wide screens thus revealed both cooperative and competitive interspecies interactions, and an underlying mechanism.

Tn-seq was used to determine gene essentiality of S. aureus as a monospecies, as well as in a coinfection with P. aeruginosa, in a murine chronic surgical wound model [42]. Analysis of these community-dependent essential (CoDE) genes showed that S. aureus toxins, including phenol-soluble modulins, and the type VII secretion system are critical for fitness in such multispecies environments. Comparison of these data with previous studies from murine abscess and osteomyelitis models showed that the changes in the S. aureus essential genome among monospecies infections in different environments are fewer than the changes between a monospecies infection and co-infection. Similar experiments in the oral pathogen Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans in pair-wise co-infections with twenty-five diverse species identified specific metabolic pathways, efflux pumps, and stress response genes as CoDE genes in multiple co-infections [43]. These studies support the idea that numerous novel targets for antimicrobial development may be missed by elucidating fitness determinants of pathogens in monospecies conditions.

Experimental evolution

Another approach that has been utilized to elucidate the selective pressures that exist in multispecies communities along with the genetic determinants of increased fitness, is experimental evolution, both in multispecies systems and in the presence of exogenous secreted effectors from another species.

Coevolution of P. aeruginosa and S. aureus in vitro revealed adaptive mutations in P. aeruginosa, the most significant of which were in the glycosyltransferase WbpL, which is involved in the biosynthesis of major components of the cell surface lipopolysaccharide (LPS) [44]. Mutations in wbpL led to a substantial fitness advantage compared with the parental strain, in the presence of S. aureus, suggesting that the loss of LPS was a major fitness determinant of P. aeruginosa in such communities. A similar adaptation has been seen in cystic fibrosis P. aeruginosa isolates that likely adapt to the existing polymicrobial community, including S. aureus, suggesting that laboratory evolution can reveal genetic determinants of fitness in native polymicrobial niches [45].

Experimental evolution of E. coli in the presence of either cell-free supernatant from P. aeruginosa, or pyocyanin, a redox-active phenazine molecule produced by P. aeruginosa, revealed likely loss-of-function mutations in MprA, a transcriptional repressor of efflux pumps, and the OmpC porin, and putative gain-of-function mutations in Fpr, an enzyme involved in anaerobic metabolism, in the evolved populations [46]. Targeted validation experiments indicated that the upregulation of specific efflux pumps could increase the fitness of E. coli in the presence of P. aeruginosa antimicrobials. These experiments also suggested that the E. coli OmpC porin is likely one of the main routes of entry for pyocyanin, and Fpr activity is potentially rate-limiting for anaerobic metabolism induced by pyocyanin, thus revealing major fitness determinants of E. coli in this interaction, as well as putative mechanisms crucial for increased E. coli fitness.

Genomic studies can thus pinpoint the genes important for specific microbial interactions as well as overall fitness in multispecies communities, and can help to elucidate the underlying mechanisms. Genomic screens have the advantage of revealing fitness effects across the genome in a single experiment, as well as being amenable for subtle phenotypic screens, but typically query loss-of-function mutations. Experimental evolution can query more diverse genetic changes including gain of function mutations, as well as multiple mutations, but is limited to identifying determinants only of increased fitness.

Integration of genomic and physiological approaches

The above techniques reveal different facets of microbial interactions including the transcriptional and functional responses of cells to exogenous species, and the genetic determinants that influence these phenotypes. Integration of these approaches can provide a more complete mechanistic dissection of a given microbial interaction, and is therefore a necessary step towards a better understanding of microbial communities, and the modulation of these for human health and biotechnological purposes.

An example of such an integrated approach was the characterization of the novel mode of development in Streptomyces venezuelae, termed exploration, where in the presence of diverse fungal species under standard laboratory conditions, S. venezuelae rapidly grow outwards from their colony even over physical barriers [47]. Screening of a knockout collection of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae showed that functioning of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and respiration in S. cerevisiae are necessary to induce S. venezuelae exploration, and targeted experiments implicated glucose levels and pH in this induction. A chemical mutagenized library screen in S. venezuelae revealed that an alkaline stress response is essential for exploration, and transcriptomic measurements showed that S. venezuelae genes that are likely alkaline stress-responsive are induced by S. cerevisiae. Finally, MS-analyses identified trimethylamine (TMA), a volatile organic compound, as a S. venezuelae-produced metabolite that stimulates exploration in nearby S. venezuelae cells, and alkalinizes the medium. Thus, this study identified a novel behavior, exploration, that is triggered by low glucose levels potentially created due to glucose consumption by nearby fungal species, likely to allow S. venezuelae to avail itself of new nearby nutrient-rich environments. Further, genomic screens in both interaction partners, transcriptional measurements, and MS-based biochemical analyses, identified the molecule, genetic pathways, and mechanisms that underlie this phenotype.

Innovative experimental strategies for studying intractable species and environments

Microbial communities commonly consist of species that are genetically intractable and essentially uncharacterized with poorly annotated genomes. Further, the native environments that most microbial communities exist in, are complex and not easily accessible for biochemical characterization. A few recent studies have used novel methods to interrogate such intractable communities and environments, and these approaches can potentially be extended to study even native environmental niches with uncharacterized microbial communities.

E. coli as a model interacting species

One strategy for understanding interplay involving understudied species has been to utilize E. coli as a model interacting species instead, exploiting its physiological state and fitness phenotypes as an indicator for the types of interactions that exist in the community and their effects on the environment. While transcriptomic measurements on short time-scales likely reflect molecules sensed in the native environment, one potential caveat to using longer-term transcriptional or fitness measurements is that E. coli cells can in turn affect the environment and community members present. A possible workaround could be to use multiple well-characterized species as model interacting partners, and focus on common interactions.

In cheese rind biofilm communities, Tn-seq experiments of E. coli in pairwise co-cultures with three cheese rind species on cheese curd agar revealed the effect each had on the community, including increased availability of specific amino acids in the presence of distinct partner species, as well as induction of stress response pathways due to the production of toxins [48]. Combined co-culture with all three species showed that several of the pairwise interactions are maintained in the complex community, including amino acid availability, but higher-order effects are seen as well. Transcriptomic measurements of E. coli indicated that the higher-order effects include competition for specific amino acids as well as nitrogen. Tn-seq in E. coli in pairwise interactions with 8 fungal cheese species also revealed analogous phenomena such as the production of toxins, increased competition for biotin and specific amino acids, as well as reduced iron competition [49].

Likewise, transcriptomic measurements in a two-species in vitro system containing P. aeruginosa, and E. coli as a model interacting species, also revealed that P. aeruginosa causes iron competition and oxidative stress in the environment, indicating that, of all the antimicrobials produced by P. aeruginosa, the iron-chelating siderophores and redox-active phenazines were inducing a response in E. coli [46]. Unlike the wild-type strain, a P. aeruginosa mutant lacking these molecules had almost no competitive advantage against E. coli, validating these findings.

Genome-wide fitness determinants and transcriptional state as readouts to characterize complex environments

One strategy that has been used to better describe the complex environments of polymicrobial communities is to compare transcriptional state and fitness measurements in well-defined environments that differ in a single biochemical parameter of interest, with those from the native environment, to better define that specific parameter in the native environment.

The commensal bacterium S. gordonii synergistically increases the virulence of the oral pathogen A. actinomycetemcomitans in abscess infections due at least in part to cross-feeding, but environmental conditions in the infection site are poorly characterized [14]. Tn-seq of A. actinomycetemcomitans in in vitro oxic and anoxic conditions revealed genes that are fitness determinants under each condition [50]. Similar experiments in a murine thigh abscess infection model identified fitness determinants that indicated the presence of both oxic and anoxic properties in the abscess. Interestingly, Tn-seq in co-infection with S. gordonii revealed that the co-infection moves A. actinomycetemcomitans closer to oxic conditions suggesting that the presence of S. gordonii promotes cross-respiration and increased aerobic metabolism, partly explaining the previously observed synergy.

Similarly, transcriptomic measurements of A. actinomycetemcomitans in iron-rich and iron-restricted media, and comparing these with the transcriptome in murine abscess monoinfections versus coinfections with S. gordonii, showed that while monoinfections are iron-replete, coinfection restricts iron availability [51]. Further, transcriptional state measurements of A. actinomycetemcomitans from a meta-transcriptomics dataset indicated that sites of human periodontal disease are likely to be iron restricted, thus providing insights even into environments in the human body that are difficult to define biochemically.

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

In recent years, unbiased experimental genome-scale approaches have begun to elucidate the molecular mechanisms that underlie interplay between microbial species in model multispecies systems (Figure 2). Such studies frequently characterize only one aspect of such phenomena, for example, measuring the physiological state of interacting species without defining phenotypic consequences, identifying molecules produced by interacting species without investigating the causal regulation or fitness effects, or identifying the genes critical for an interaction without dissection of the molecular mechanisms.

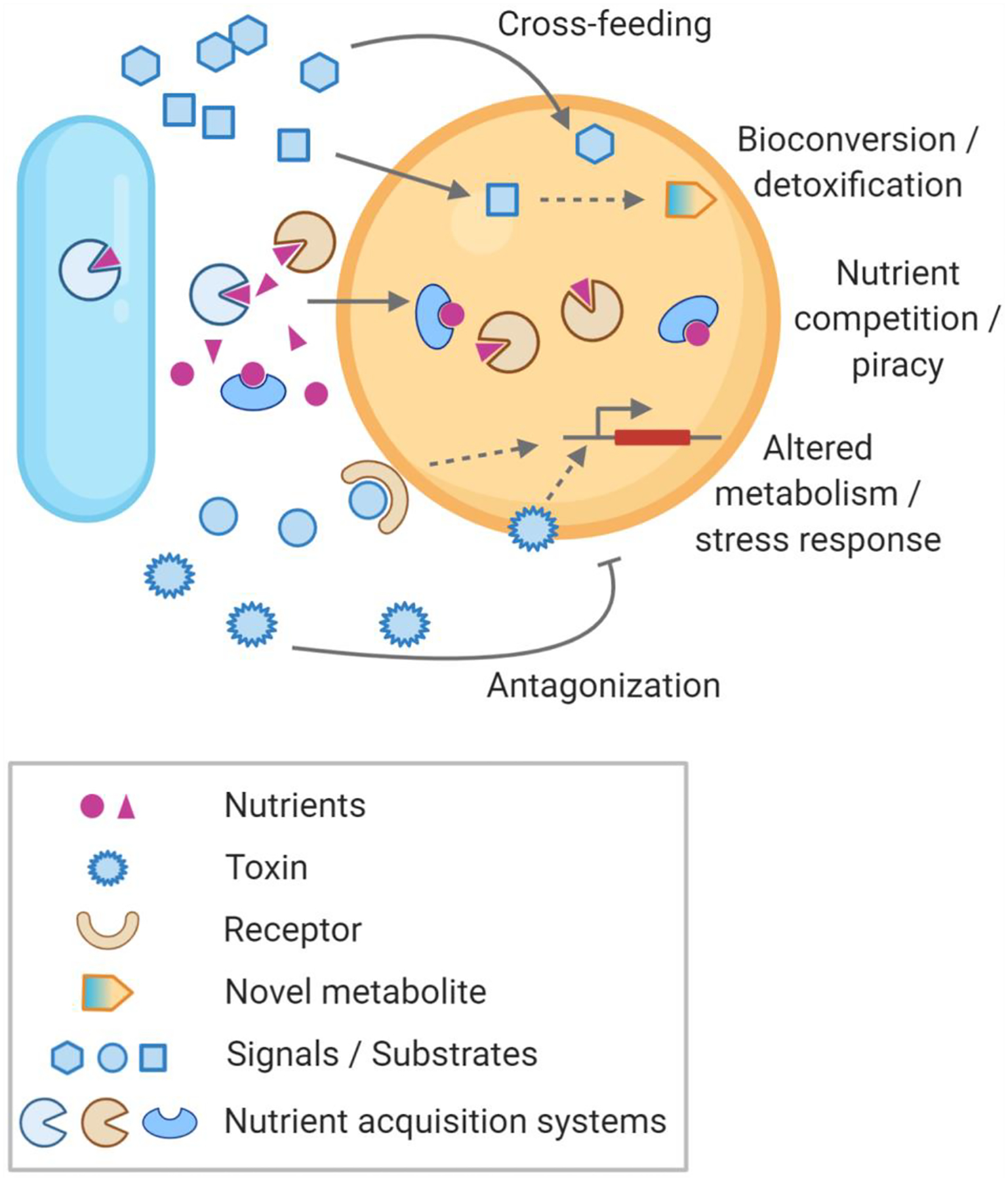

Figure 2. Examples of interspecies interactions identified via experimental systems biology approaches.

A diverse array of microbial interactions, and their molecular underpinnings, have been identified via experimental genome-scale methodologies. Some of these include (i) cross-feeding where one species can utilize metabolites released by other species; (ii) emergent metabolism wherein a microorganism can biotransform metabolites produced by a foreign species; (iii) detoxification where one species can neutralize toxins produced by other microbes via a biochemical conversion; (iv) competition for nutrients between species; (v) nutrient piracy, for example, that seen with siderophores, where microorganisms can utilize nutrient acquisition systems from other species; (vi) antagonization of microbes due to toxins produced by other species; and (vii) changes in stress response induction, and cellular metabolism, due to either toxins or other signal molecules produced by the microbial community.

Integration of these multifaceted unbiased approaches, followed by targeted validation assays, can provide a more complete understanding of polymicrobial interactions at the genetic, physiological, and molecular level. Further, while often difficult to accomplish experimentally, the environmental context of these interactions needs to be factored into such studies to reveal the true impact of these interactions in natural environmental niches (see Outstanding Questions). A recent technique for mapping the spatial distribution of complex microbial communities via gel immobilization, followed by sequencing, may aid in moving mechanistic studies to native environments [52]. Genomic and phenotypic variation at the strain level within a species can also be a confounding factor for a general understanding of microbial communities. Lastly, while most molecular mechanistic studies of interspecies interactions are carried out in two-species systems, expanding these approaches to more complex systems, similar to what are found in natural environments, will be crucial to effectively characterize how these interactions affect the dynamics of native communities.

Outstanding Questions.

How can experimental systems be designed that better mimic native environmental niches of microbial communities?

Can interactions in multispecies communities be extrapolated from the respective pairwise interactions?

Can current technologies be utilized to concurrently characterize multiple species in a complex community?

What role do microbial interactions play in the healthy and diseased states of the human microbiome, where such phenomena remain poorly defined?

Highlights.

Unbiased experimental systems biology techniques can uncover the mechanisms of interactions between microbial species that co-exist in communities.

Transcriptomic, proteomic and metabolomic measurements have revealed diverse responses to exogenous species including induction of stress responses, changes in metabolism, nutrient competition, and bioconversion.

Genomic screens and experimental evolution have identified genetic determinants important for interspecies interactions and fitness in a community, and changes in gene essentiality of a species when in a microbial community.

Combining diverse approaches to study microbial interactions can provide a broader understanding of the physiological consequences of such interplay on microbial species, the molecules and genetic pathways critical to these interactions, and the ultimate effect on multispecies communities.

Acknowledgments

I thank S. Gottesman, I. Pastan, S. Tavazoie, G. Storz, J. A. Segre, K. S. Ramamurthi, M. P. Machner, and members of the Khare laboratory for helpful comments on the review. The figures were created with BioRender.com. The writing of this review was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lane N (2015) The unseen world: reflections on Leeuwenhoek (1677) ‘Concerning little animals’. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 370 (1666), 20140344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Little AE et al. (2008) Rules of engagement: interspecies interactions that regulate microbial communities. Annual Review of Microbiology 62, 375–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hibbing ME et al. (2010) Bacterial competition: surviving and thriving in the microbial jungle. Nature Reviews Microbiology 8 (1), 15–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fierer N (2017) Embracing the unknown: disentangling the complexities of the soil microbiome. Nature Reviews Microbiology 15 (10), 579–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang J and Jia H (2016) Metagenome-wide association studies: fine-mining the microbiome. Nature Reviews Microbiology 14 (8), 508–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thakur MP and Geisen S (2019) Trophic regulations of the soil microbiome. Trends in Microbiology 27 (9), 771–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oberhardt MA et al. (2009) Applications of genome-scale metabolic reconstructions. Molecular Systems Biology 5 (1), 320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang X et al. (2019) Advancing functional and translational microbiome research using meta-omics approaches. Microbiome 7 (1), 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dodd D et al. (2017) A gut bacterial pathway metabolizes aromatic amino acids into nine circulating metabolites. Nature 551 (7682), 648–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rekdal VM et al. (2020) A widely distributed metalloenzyme class enables gut microbial metabolism of host-and diet-derived catechols. Elife 9, e50845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mooij MJ et al. (2011) The Pseudomonas quinolone signal (PQS), and its precursor HHQ, modulate interspecies and interkingdom behaviour. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 77 (2), 413–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Radlinski L et al. (2017) Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoproducts determine antibiotic efficacy against Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS Biology 15 (11), e2003981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vega NM et al. (2013) Salmonella typhimurium intercepts Escherichia coli signaling to enhance antibiotic tolerance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110 (35), 14420–14425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramsey MM et al. (2011) Metabolite cross-feeding enhances virulence in a model polymicrobial infection. PLoS Pathogens 7 (3), e1002012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Limoli DH et al. (2019) Interspecies interactions induce exploratory motility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Elife 8, e47365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Brien S and Fothergill JL (2017) The role of multispecies social interactions in shaping Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenicity in the cystic fibrosis lung. FEMS Microbiology Letters 364 (15), fnx128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ibberson CB and Whiteley M (2020) The social life of microbes in chronic infection. Current Opinion in Microbiology 53, 44–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hajishengallis G and Lamont RJ (2012) Beyond the red complex and into more complexity: the polymicrobial synergy and dysbiosis (PSD) model of periodontal disease etiology. Molecular Oral Microbiology 27 (6), 409–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khan R et al. (2019) Commensal bacteria: an emerging player in defense against respiratory pathogens. Frontiers in Immunology 10, 1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolfe BE and Dutton RJ (2015) Fermented foods as experimentally tractable microbial ecosystems. Cell Host & Microbe 161 (1), 49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heintz-Buschart A et al. (2016) Integrated multi-omics of the human gut microbiome in a case study of familial type 1 diabetes. Nature Microbiology 2 (1), 16180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lü F et al. (2014) Metaproteomics of cellulose methanisation under thermophilic conditions reveals a surprisingly high proteolytic activity. The ISME journal 8 (1), 88–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heyer R et al. (2019) Metaproteome analysis reveals that syntrophy, competition, and phage-host interaction shape microbial communities in biogas plants. Microbiome 7 (1), 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lillington SP et al. (2020) Nature’s recyclers: anaerobic microbial communities drive crude biomass deconstruction. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 62, 38–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xue M-Y et al. (2020) Multi-omics reveals that the rumen microbiome and its metabolome together with the host metabolome contribute to individualized dairy cow performance. Microbiome 8, 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abu-Ali GS et al. (2018) Metatranscriptome of human faecal microbial communities in a cohort of adult men. Nature Microbiology 3 (3), 356–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hendrickson EL et al. (2017) Insights into dynamic polymicrobial synergy revealed by time-coursed RNA-Seq. Frontiers in Microbiology 8, 261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Filkins LM et al. (2015) Coculture of Staphylococcus aureus with Pseudomonas aeruginosa drives S. aureus towards fermentative metabolism and reduced viability in a cystic fibrosis model. Journal of Bacteriology 197 (14), 2252–2264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee N et al. (2020) Iron competition triggers antibiotic biosynthesis in Streptomyces coelicolor during coculture with Myxococcus xanthus. The ISME Journal 14 (5), 1111–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cornforth DM and Foster KR (2013) Competition sensing: the social side of bacterial stress responses. Nature Reviews Microbiology 11 (4), 285–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kastman EK et al. (2016) Biotic interactions shape the ecological distributions of Staphylococcus species. MBio 7 (5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bertrand S et al. (2014) Metabolite induction via microorganism co-culture: a potential way to enhance chemical diversity for drug discovery. Biotechnology Advances 32 (6), 1180–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsukamoto T et al. (2001) Proposal of Mycetocola gen. nov. in the family Microbacteriaceae and three new species, Mycetocola saprophilus sp. nov., Mycetocola tolaasinivorans sp. nov. and Mycetocola lacteus sp. nov., isolated from cultivated mushroom, Pleurotus ostreatus. International Journal of Systematic Evolutionary Microbiology 51 (3), 937–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsukamoto T et al. (1998) Isolation of a Gram-positive bacterium effective in suppression of brown blotch disease of cultivated mushrooms, Pleurotus ostreatus and Agaricus bisporus, caused by Pseudomonas tolaasii. Mycoscience 39 (3), 273–278. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hermenau R et al. (2020) Helper bacteria halt and disarm mushroom pathogens by linearizing structurally diverse cyclolipopeptides. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117 (38), 23802–23806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michelsen CF et al. (2016) Evolution of metabolic divergence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa during long-term infection facilitates a proto-cooperative interspecies interaction. The ISME journal 10 (6), 1323–1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hotterbeekx A et al. (2017) In vivo and In vitro Interactions between Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus spp. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 7, 106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moree WJ et al. (2012) Interkingdom metabolic transformations captured by microbial imaging mass spectrometry. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109 (34), 13811–13816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keogh D et al. (2016) Enterococcal metabolite cues facilitate interspecies niche modulation and polymicrobial infection. Cell Host & Microbe 20 (4), 493–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Armbruster CE et al. (2017) Genome-wide transposon mutagenesis of Proteus mirabilis: Essential genes, fitness factors for catheter-associated urinary tract infection, and the impact of polymicrobial infection on fitness requirements. PLoS Pathogens 13 (6), e1006434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnson AO et al. (2020) Transposon Insertion Site Sequencing of Providencia stuartii: Essential Genes, Fitness Factors for Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection, and the Impact of Polymicrobial Infection on Fitness Requirements. Msphere 5 (3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ibberson CB et al. (2017) Co-infecting microorganisms dramatically alter pathogen gene essentiality during polymicrobial infection. Nature Microbiology 2 (8), 17079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lewin GR et al. (2019) Large-scale identification of pathogen essential genes during coinfection with sympatric and allopatric microbes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116 (39), 19685–19694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tognon M et al. (2017) Co-evolution with Staphylococcus aureus leads to lipopolysaccharide alterations in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The ISME journal 11 (10), 2233–2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Faure E et al. (2018) Pseudomonas aeruginosa in chronic lung infections: how to adapt within the host? Frontiers in Immunology 9, 2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khare A and Tavazoie S (2015) Multifactorial competition and resistance in a two-species bacterial system. PLoS Genetics 11 (12), e1005715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jones SE et al. (2017) Streptomyces exploration is triggered by fungal interactions and volatile signals. Elife 6, e21738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morin M et al. (2018) Changes in the genetic requirements for microbial interactions with increasing community complexity. Elife 7, e37072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pierce EC et al. (2020) Bacterial–fungal interactions revealed by genome-wide analysis of bacterial mutant fitness. Nature Microbiology, 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stacy A et al. (2016) A commensal bacterium promotes virulence of an opportunistic pathogen via cross-respiration. MBio 7 (3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stacy A et al. (2016) Microbial community composition impacts pathogen iron availability during polymicrobial infection. PLoS Pathogens 12 (12), e1006084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sheth RU et al. (2019) Spatial metagenomic characterization of microbial biogeography in the gut. Nature Biotechnology 37 (8), 877–883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Medema MH et al. (2011) antiSMASH: rapid identification, annotation and analysis of secondary metabolite biosynthesis gene clusters in bacterial and fungal genome sequences. Nucleic Acids Research 39 (suppl_2), W339–W346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van der Helm E et al. (2018) The evolving interface between synthetic biology and functional metagenomics. Nature Chemical Biology 14 (8), 752–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Katz M et al. (2016) Culture-independent discovery of natural products from soil metagenomes. Journal of Industrial Microbiology & Biotechnology 43 (2–3), 129–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dos Santos DFK et al. (2017) Functional metagenomics as a tool for identification of new antibiotic resistance genes from natural environments. Microbial Ecology 73 (2), 479–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sommer MO et al. (2009) Functional characterization of the antibiotic resistance reservoir in the human microflora. Science 325 (5944), 1128–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Levy R and Borenstein E (2013) Metabolic modeling of species interaction in the human microbiome elucidates community-level assembly rules. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110 (31), 12804–12809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zelezniak A et al. (2015) Metabolic dependencies drive species co-occurrence in diverse microbial communities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112 (20), 6449–6454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Machado D et al. (2021) Polarization of microbial communities between competitive and cooperative metabolism. Nature Ecology & Evolution 5, 195–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Magnúsdóttir S et al. (2017) Generation of genome-scale metabolic reconstructions for 773 members of the human gut microbiota. Nature Biotechnology 35 (1), 81–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bauer E et al. (2017) BacArena: Individual-based metabolic modeling of heterogeneous microbes in complex communities. PLoS Computational Biology 13 (5), e1005544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thommes M et al. (2019) Designing metabolic division of labor in microbial communities. mSystems 4 (2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zarco M et al. (2012) The oral microbiome in health and disease and the potential impact on personalized dental medicine. Oral Diseases 18 (2), 109–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Simón-Soro A and Mira A (2015) Solving the etiology of dental caries. Trends in Microbiology 23 (2), 76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Welp AL and Bomberger JM (2020) Bacterial Community Interactions During Chronic Respiratory Disease. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 10, 213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lopes SP et al. (2015) Microbiome in cystic fibrosis: shaping polymicrobial interactions for advances in antibiotic therapy. Critical Reviews in Microbiology 41 (3), 353–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fuhrman JA et al. (2015) Marine microbial community dynamics and their ecological interpretation. Nature Reviews Microbiology 13 (3), 133–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cordovez V et al. (2019) Ecology and evolution of plant microbiomes. Annual Review of Microbiology 73, 69–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Landis EA et al. (2021) The diversity and function of sourdough starter microbiomes. Elife 10, e61644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Blasche S et al. (2021) Metabolic cooperation and spatiotemporal niche partitioning in a kefir microbial community. Nature Microbiology 6, 196–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wolfe BE et al. (2014) Cheese rind communities provide tractable systems for in situ and in vitro studies of microbial diversity. Cell 158 (2), 422–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]