Abstract

The impact of lockdown on life style and behaviour have piqued the interest of people and scientific community, all over the world. It has been demonstrated that in some countries, mandatory stay-at-home limitations and self-isolation measures are linked to an increase in sleeping hours and smoking cigarettes per day. However, these results derive from countries that lockdown had different features and length, and it is possible that society, culture, customs, ecological or other factors may independently or in combination affect life style habits (such sleeping and smoking) in different populations. So, we focus on sleeping and smoking changes in Greek adults during the lockdown of early COVID-19 presence in Greece. Therefore, our aim was to investigate whether lockdown alters smoking and sleeping habits and whether physical activity (PA), gender, age or body mass index (BMI) play a role. The modified online-based Active-Q (Greek version) questionnaire (see Supplementary file 1_Active-Q_modyfied) was used to collect data prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (PRE condition) and during physical distancing and lockdown measures (POST condition). The data period collection was from April 4 to April 19, 2020 (15 days in total) and respondents classified into four PA categories based on their sporting activities (PRE condition), five age categories and four BMI categories, which corresponding to different subgroup. Overall, sleeping hours change (from PRE to POST condition) was 11.80% and smoking cigarettes per day change was 9.35%. However, it appears that between the different subgroups significant differences were also identified.

Keywords: Cross-sectional, Public health, Quarantine, SARS-CoV-2, Sedentary life, Tobacco, Self-report, Life style

Specifications Table

| Subject | Public Health and Health Policy |

| Specific subject area | Smoking, sleeping, and lockdown |

| Type of data | Table & Figure |

| How data were acquired | Survey. The interactive web-based Greek revised version of Active-Q for adults questionnaire was used to classified respondents into four physical activity categories based on their sporting activities, five age categories and four body mass index categories; (see Supplementary file 1_Active-Q_modyfied). In addition, two questions about participants’ number of usual cigarettes smoked per day and total hours of sleep per day were attached to the questionnaire to measure the usual cigarettes smoked and total hours of sleep per day prior to the COVID-19 lockdown and during lockdown measures. |

| Data format | Sleeping (h·day) and smoking (cigarettes·day−1) data are in raw format. Gender, age, body mass index, and physical activity levels classification are in nominal and categorical formats. |

| Parameters for data collection | Inclusion criteria for participation in the survey: ≥18 yr, Greece residency, Internet access. Exclusion criteria: participation in a strict weight loss control program, any form of illness, pregnancy or childbirth in the previous year. |

| Description of data collection | Data were collected in 15 consecutive days (4th of April till 19th of April 2020), through an Internet survey source providing an interactive web-based questionnaire. An Excel file with the aforementioned data and metadata has been uploaded (see Supplementary file 2_Data). |

| Data source location | Institution: National and Kapodistrian University of Athens Region: Europe Country: Greece |

| Data accessibility | Data and metadata are hosted with the article. |

| Related research article | This study was part of a joint project and is an extension of a previous study with the same sample (D.I. Bourdas, E.D. Zacharakis, Impact of COVID-19 Lockdown on Physical Activity in a Sample of Greek Adults, Sports. 8 (2020) 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports8100139). |

Value of the Data

-

•

These data show the magnitude of the daily life style changes concerning smoking and sleeping habits since physical distancing and anti-COVID-19 measures applied in Greece.

-

•

We believe our data will encourage and assist health authorities’ policy makers to develop applied antismoking guidelines for lockdown and to create an efficient action plan against sleeping disorders to overcome lockdown consequences.

-

•

In a world of rising depression, anxiety, adverse behaviors, alcohol use, smoking, eating and sleep disorders, our data will hopefully assist determine public health priorities and health services plans, people identify and control unhealthy behaviors and potentially encourage community develop psychological skills (stress management, attentional focus, communication, goal setting, mental practice, self-talk, confidence) or motivate people to seek professional assistance and social support when it is needed.

-

•

Informing the community of the sleeping and smoking increase during lockdown may have acute - or long-term implications on the evolution rate of depression, anxiety, adverse behaviors, alcohol use, and eating disorders, as well as on public health care systems in general.

-

•

Since lockdown affect the population's sleeping and smoking habits, these data may generate additional hypotheses for upcoming research.

1. Data Description

During the COVID-19 pandemic people have to deal with many psychological problems, such as lack of communication with family and friends, feelings of isolation, high levels of perceived stress and maladaptive psychobiosocial states (e.g., depression, anxiety, adverse behaviors, smoking, alcohol use, eating and sleep disorders) [1] which may inevitably affect daily life style habits and behavior. Known that the COVID-19 lockdown applied in each country has had different features and length, and that society, culture, customs, ecological or other factors may independently or in combination affect life style habits (e.g., physical activity (PA) [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], sleeping [7], [8], [9], [10], smoking [11], [12], [13], [14]) in different populations, we focus on sleeping and smoking changes in Greek adults during the lockdown of early COVID-19 presence in Greece. Therefore, our aim was to investigate whether lockdown alters smoking and sleeping habits and whether PA, gender, age or body mass index (BMI) play a role. This study was part of a joint project and is an extension of a previous study [15] with the same sample; therefore, some characteristics [i.e., gender, age, BMI, and PA levels] of the sample are necessarily partially mentioned in the present study.

The Greek version of Active-Q questionnaire was used for data collection [in PRE condition (prior to the COVID-19 crisis and lockdown) and POST condition (during physical distancing and lockdown measures)] [15,16]. Data were collected from a total of 8495 individuals (38.32% males; 61.68% females) who participated in the survey. Respondents stated their anthropometric characteristics, the usual sport and exercise PA, sleeping and smoking habits. Through the online interactive platform, respondents classified into four PA categories based on their sporting activities, five age categories and four BMI categories [17], [18], [19] and subgrouped accordingly (see Supplementary file 2_Data, in the sheet under the name data-metadata). Frequency and relative frequency of subgroups by gender, age, BMI, and PA levels in PRE condition are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Frequency, relative frequency, and 95%CI of respondents (n = 8495) subgrouped by gender, age, BMI, and PA levels in PRE condition.

| Subgroups | Frequency | Relative frequency (%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Males | 3255 | 38.32 | 36.65 — 39.99 |

| Females | 5240 | 61.68 | 60.36 — 63.00 |

| Young (18–29 yr) | 3210 | 37.79 | 36.11 — 39.47 |

| Adults (30–49 yr) | 3277 | 38.58 | 36.91 — 40.25 |

| Middle-Age Adults (50–59 yr) | 1639 | 19.29 | 17.38 — 21.20 |

| Old Adults (60–69 yr) | 336 | 3.96 | 1.87 — 6.05 |

| 70+ (≥70 yr) | 33 | 0.39 | 0.00 — 2.52 |

| Underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg·m–2) | 321 | 3.78 | 1.69 — 5.87 |

| Acceptable weight (BMI = 18.5–24.9 kg·m–2) | 4711 | 55.46 | 54.04 — 56.88 |

| Overweight (BMI = 25.0–29.9 kg·m–2) | 2527 | 29.75 | 27.97 — 31.53 |

| Obese (BMI ≥30kg·m–2) | 936 | 11.02 | 9.01 — 13.03 |

| Inactive (0 MET -min·week–1) | 1689 | 19.88 | 17.98 — 21.78 |

| Low PA (0–499 MET -min·week–1) | 1190 | 14.01 | 12.04 — 15.98 |

| Moderate PA (500–1000 MET -min·week–1) | 963 | 11.34 | 9.34 — 13.34 |

| High PA (>1000 MET -min·week–1) | 4653 | 54.77 | 53.34 — 56.20 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; MET, metabolic equivalent task (= 3.5 mL O₂·kg–1·min–1); PA, physical activity based on sport and exercise activities; PRE, normal living before the onset of COVID-19.

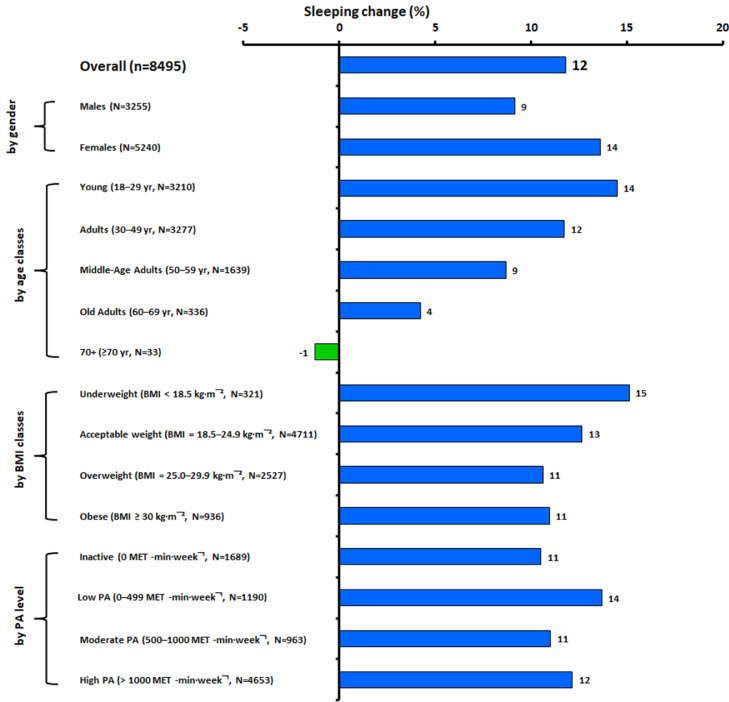

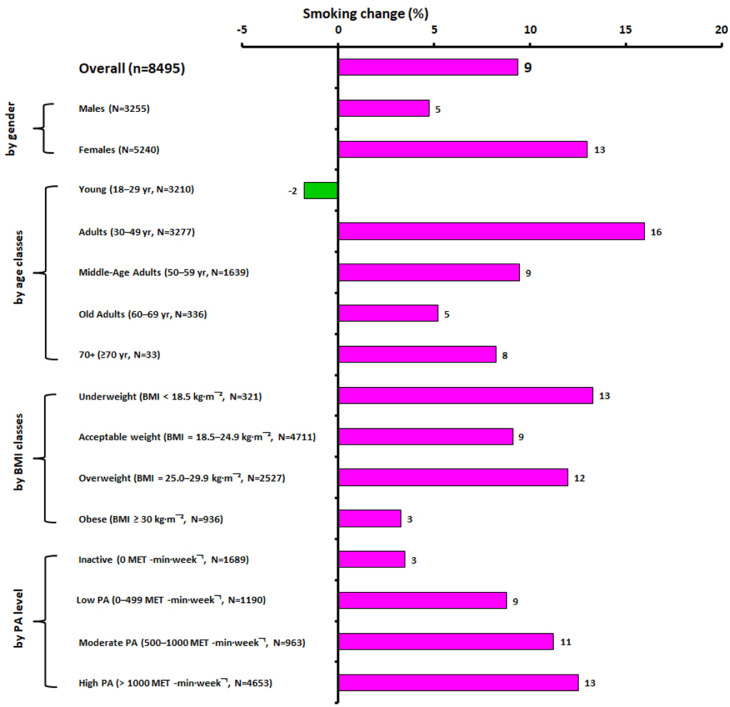

Habitual sleeping hours and smoking cigarettes per day PRE and POST condition, overall and in all subgroups are presented in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Sleeping hours per day increased significantly (p < 0.05) in POST condition overall by 11.80% (Fig. 1) and almost in all subgroups [except the 70+ (≥70 yr) subgroup]. Alike, smoking cigarettes per day increased significantly (p < 0.05) in POST condition overall by 9.35% (Fig. 2) and in the most subgroups, [except the Young (18–29 yr), Old Adults (60–69 yr), 70+ (≥70 yr), Obese (BMI ≥30 kg·m–2) and Inactive (0 MET -min·week−1) subgroups]. Moreover, It has to be noted that non-smokers increased and smokers decreased from pre to post assessment (6474 to 6582 and 2021 to 1913, respectively), while for smokers the number of smoking cigarettes per day increased (Mpre = 11.68 ± 9.09, Mpost = 13.49 ± 10.62). For data and metadata, please see Supplementary file 2_Data, in the sheet under the name data-metadata.

Table 2.

Sleeping data (h·day–1) of respondents, overall (n = 8495), by gender, age, BMI, and PA levels in the PRE and POST conditions.

| PRE |

POST |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group/Subgroups | Mean | SD | 95% CI | Mean | SD | 95% CI |

| *Overall | 6.95 | 1.06 | 6.92 — 6.97 | 7.77 | 1.36 | 7.74 — 7.80 |

| *Males | 6.89 | 1.03 | 6.85 — 6.92 | 7.52 | 1.30 | 7.48 — 7.56 |

| *Females | 6.98 | 1.07 | 6.95 — 7.01 | 7.93 | 1.37 | 7.89 — 7.97 |

| *Young (18–29 yr) | 7.25 | 1.14 | 7.20 — 7.29 | 8.30 | 1.35 | 8.25 — 8.35 |

| *Adults (30–49 yr) | 6.82 | 0.96 | 6.79 — 6.85 | 7.62 | 1.25 | 7.57 — 7.66 |

| *Middle-Age Adults (50–59 yr) | 6.67 | 0.94 | 6.62 — 6.71 | 7.25 | 1.26 | 7.19 — 7.31 |

| *Old Adults (60–69 yr) | 6.63 | 0.96 | 6.52 — 6.73 | 6.91 | 1.05 | 6.80 — 7.02 |

| 70+ (≥70 yr) | 6.94 | 0.79 | 6.67 — 7.21 | 6.85 | 0.71 | 6.60 — 7.09 |

| *Underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg·m–2) | 7.21 | 0.98 | 7.10 — 7.32 | 8.30 | 1.34 | 8.15 — 8.44 |

| *Acceptable weight (BMI = 18.5–24.9 kg·m–2) | 7.03 | 1.06 | 7.00 — 7.06 | 7.92 | 1.35 | 7.88 — 7.95 |

| *Overweight (BMI = 25.0–29.9 kg·m–2) | 6.87 | 1.01 | 6.83 — 6.91 | 7.60 | 1.28 | 7.55 — 7.65 |

| *Obese (BMI ≥30 kg·m–2) | 6.67 | 1.12 | 6.60 — 6.74 | 7.40 | 1.46 | 7.30 — 7.49 |

| *Inactive (0 MET -min·week–1) | 6.85 | 1.16 | 6.80 — 6.91 | 7.57 | 1.41 | 7.51 — 7.64 |

| *Low PA (0–499 MET -min·week–1) | 6.86 | 1.02 | 6.80 — 6.92 | 7.80 | 1.36 | 7.72 — 7.88 |

| *Moderate PA (500–1000 MET -min·week–1) | 6.99 | 1.01 | 6.92 — 7.05 | 7.76 | 1.32 | 7.68 — 7.84 |

| *High PA (> 1000 MET -min·week–1) | 6.99 | 1.03 | 6.96 — 7.02 | 7.84 | 1.34 | 7.80 — 7.88 |

p < 0.05, significant difference between the PRE and POST conditions.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; MET, metabolic equivalent task (= 3.5 mL O₂·kg–1·min–1); PA, physical activity based on sport and exercise activities on a weekly basis; PRE, normal living before the onset of COVID-19; POST, living after the appearance of COVID-19 and under physical distasting measures.

Table 3.

Smoking data (cigaretes·day–1) of respondents, overall (n = 8495), by gender, age, BMI, and PA levels in the PRE and POST conditions.

| PRE |

POST |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group/Subgroups | Mean | SD | 95% CI | Mean | SD | 95% CI |

| *Overall | 2.78 | 6.66 | 2.64 — 2.92 | 3.04 | 7.56 | 2.88 — 3.20 |

| *Males | 3.16 | 7.80 | 2.89 — 3.42 | 3.31 | 8.35 | 3.02 — 3.60 |

| *Females | 2.54 | 5.83 | 2.38 — 2.70 | 2.87 | 7.02 | 2.68 — 3.06 |

| Young (18–29 yr) | 1.67 | 4.83 | 1.50 — 1.84 | 1.64 | 5.31 | 1.45 — 1.82 |

| *Adults (30–49 yr) | 3.13 | 7.39 | 2.88 — 3.38 | 3.63 | 8.49 | 3.34 — 3.92 |

| *Middle-Age Adults (50–59 yr) | 3.81 | 7.35 | 3.45 — 4.16 | 4.17 | 8.34 | 3.77 — 4.57 |

| Old Adults (60–69 yr) | 4.79 | 8.54 | 3.88 — 5.71 | 5.04 | 9.58 | 4.02 — 6.07 |

| 70+ (≥70 yr) | 3.64 | 9.21 | 0.49 — 6.78 | 3.94 | 9.66 | 0.64 — 7.24 |

| *Underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg·m–2) | 1.81 | 4.70 | 1.30 — 2.33 | 2.05 | 5.83 | 1.41 — 2.68 |

| *Acceptable weight (BMI = 18.5–24.9 kg·m–2) | 2.31 | 5.54 | 2.15 — 2.46 | 2.52 | 6.42 | 2.34 — 2.70 |

| *Overweight (BMI = 25.0–29.9 kg·m–2) | 3.34 | 7.67 | 3.04 — 3.64 | 3.74 | 8.89 | 3.39 — 4.08 |

| Obese (BMI ≥30 kg·m–2) | 3.96 | 8.88 | 3.39 — 4.53 | 4.09 | 9.18 | 3.50 — 4.67 |

| Inactive (0 MET -min·week–1) | 4.03 | 7.89 | 3.65 — 4.40 | 4.17 | 8.84 | 3.74 — 4.59 |

| *Low PA (0–499 MET -min·week–1) | 2.74 | 7.68 | 2.30 — 3.17 | 2.98 | 8.39 | 2.51 — 3.46 |

| *Moderate PA (500–1000 MET -min·week–1) | 2.85 | 6.56 | 2.43 — 3.26 | 3.17 | 7.36 | 2.70 — 3.63 |

| *High PA (> 1000 MET -min·week–1) | 2.32 | 5.80 | 2.15 — 2.49 | 2.61 | 6.80 | 2.42 — 2.81 |

p < 0.05, significant difference between the PRE and POST conditions.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; MET, metabolic equivalent task (= 3.5 mL O₂·kg–1·min–1); PA, physical activity based on sport and exercise activities on a weekly basis; PRE, normal living before the onset of COVID-19; POST, living after the appearance of COVID-19 and under physical distasting measures.

Fig. 1.

Overall sleeping change (%, from the PRE to POST conditions) in all respondents and grouped by gender, age, BMI, and PA level. Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; MET, metabolic equivalent task (= 3.5 mL O₂·kg–1·min–1); PA, physical activity based on sport and exercise activities on a weekly basis; PRE, normal living before the onset of COVID-19; POST, living after the appearance of COVID-19 and under physical distasting measures.

Fig. 2.

Overall smoking change (%, from the PRE to POST conditions) in all respondents and grouped by gender, age, BMI, and PA level. Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; MET, metabolic equivalent task (= 3.5 mL O₂·kg–1·min–1); PA, physical activity based on sport and exercise activities on a weekly basis; PRE, normal living before the onset of COVID-19; POST, living after the appearance of COVID-19 and under physical distasting measures.

Respondents’ sleeping and smoking habits expressed in h·day−1 and cigarettes·day−1 values (respectively) POST condition by gender, age, BMI, and PA levels, adjusted for the PRE condition covariate values, are presented in Tables 4 and 5. Although the increase in both sleeping hours and smoking cigarettes per day during POST condition is evident, it appears that between the different subgroups significant differences were also identified (p < 0.05; Tables 4 and 5).

Table 4.

Sleeping data (h·day–1) during POST condition, adjusted for PRE condition covariate valuesa, in the subgroups (by gender, age, BMI, and PA levels). There was an overall statistically significant difference* in sleeping hours POST condition between the different subgroups once their means had been adjusted for PRE condition.

| Subgroups | Mean | SD | 95% CI | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Males | 7.55 | 1.20 | 7.51 — 7.59 | |

| 2 | Females | 7.91 | 1.20 | 7.88 — 7.94 | *2 > 1 |

| 1 | Young (18–29 yr) | 8.15 | 1.19 | 8.10 — 8.19 | *1 > 2,3,4,5 |

| 2 | Adults (30–49 yr) | 7.68 | 1.17 | 7.64 — 7.72 | *2 > 3,4,5 |

| 3 | Middle-Age Adults (50–59 yr) | 7.40 | 1.18 | 7.34 — 7.45 | *3 > 4 |

| 4 | Old Adults (60–69 yr) | 7.08 | 1.17 | 6.95 — 7.20 | |

| 5 | 70+ (≥70 yr) | 6.85 | 1.17 | 6.45 — 7.25 | |

| 1 | Underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg·m–2) | 8.15 | 1.21 | 8.01 — 8.27 | *1 > 2,3,4 |

| 2 | Acceptable weight (BMI = 18.5–24.9 kg·m–2) | 7.86 | 1.21 | 7.83 — 7.90 | *2 > 3,4 |

| 3 | Overweight (BMI = 25.0–29.9 kg·m–2) | 7.64 | 1.21 | 7.60 — 7.69 | |

| 4 | Obese (BMI ≥30 kg·m–2) | 7.55 | 1.21 | 7.47 — 7.63 | |

| 1 | Inactive (0 MET -min·week–1) | 7.63 | 1.21 | 7.57 — 7.69 | |

| 2 | Low PA (0–499 MET -min·week–1) | 7.85 | 1.21 | 7.78 — 7.92 | *2 > 1 |

| 3 | Moderate PA (500–1000 MET -min·week–1) | 7.74 | 1.21 | 7.66 — 7.81 | |

| 4 | High PA (> 1000 MET -min·week–1) | 7.82 | 1.21 | 7.78 — 7.85 | *4 > 1 |

Covariates appearing in the model are evaluated at the following values: 6.95.

p < 0.05.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; MET, metabolic equivalent task (= 3.5 mL O₂·kg–1·min–1); PA, physical activity based on sport and exercise activities on a weekly basis; PRE, normal living before the onset of COVID-19; POST, living after the appearance of COVID-19 and under physical distasting measures.

Table 5.

Smoking data (cigarettes·day–1) during POST condition, adjusted for PRE condition covariate valuesa, in the subgroups (by gender, age, BMI, and PA levels). There was an overall statistically significant difference* in smoking cigarettes per day POST condition between the different subgroups once their means had been adjusted for PRE condition.

| Subgroups | Mean | SD | 95% CI | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Males | 2.92 | 2.92 | 2.81 — 3.02 | |

| 2 | Females | 3.11 | 2.92 | 3.03 — 3.19 | *2 > 1 |

| 1 | Young (18–29 yr) | 2.79 | 2.93 | 2.69 — 2.89 | |

| 2 | Adults (30–49 yr) | 3.26 | 2.92 | 3.16 — 3.36 | *2 > 1 |

| 3 | Middle-Age Adults (50–59 yr) | 3.10 | 2.92 | 2.95 — 3.24 | *3 > 1 |

| 4 | Old Adults (60–69 yr) | 2.94 | 2.92 | 2.63 — 3.25 | |

| 5 | 70+ (≥70 yr) | 3.04 | 2.92 | 2.05 — 4.04 | |

| 1 | Underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg·m–2) | 3.06 | 2.92 | 2.74 — 3.38 | |

| 2 | Acceptable weight (BMI = 18.5–24.9 kg·m–2) | 3.01 | 2.93 | 2.93 — 3.10 | |

| 3 | Overweight (BMI = 25.0–29.9 kg·m–2) | 3.15 | 2.93 | 3.03 — 3.26 | *3 > 4 |

| 4 | Obese (BMI ≥30 kg·m–2) | 2.85 | 2.93 | 2.66 — 3.04 | |

| 1 | Inactive (0 MET -min·week–1) | 2.86 | 2.93 | 2.71 — 3.00 | |

| 2 | Low PA (0–499 MET -min·week–1) | 3.03 | 2.92 | 2.86 — 3.19 | |

| 3 | Moderate PA (500–1000 MET -min·week–1) | 3.10 | 2.92 | 2.91 — 3.28 | |

| 4 | High PA (> 1000 MET -min·week–1) | 3.09 | 2.93 | 3.01 — 3.18 | *4 > 1 |

Covariates appearing in the model are evaluated at the following values: 2.78.

p < 0.05.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; MET, metabolic equivalent task (= 3.5 mL O₂·kg–1·min–1); PA, physical activity based on sport and exercise activities on a weekly basis; PRE, normal living before the onset of COVID-19; POST, living after the appearance of COVID-19 and under physical distasting measures.

Pearson product moment correlations for all variables are presented in Table 6. The results showed that correlations between PRE and POST conditions for sleeping (r = 0.453, p < 0.01) and smoking (r = 0.922, p < 0.01) were at moderate and high levels, respectively. This indicated that as sleeping and smoking values increased at the PRE condition, so did the POST sleeping and smoking values.

Table 6.

Pearson product moment correlations for Age, BMI, PA levels, PRE Sleeping (h·day–1), PRE Smoking (cigarettes·day–1), POST Sleeping (h·day–1), and POST Smoking (cigarettes·day–1) (n = 8495).

| BMI classification | PA classification | PRE Sleeping (h·day–1) |

PRE Smoking (cigarettes·day–1) | POST Sleeping (h·day–1) | POST Smoking (cigarettes·day–1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age classification | ⁎⁎0.319 | ⁎⁎-0.124 | ⁎⁎-0.211 | ⁎⁎0.136 | ⁎⁎-0.321 | ⁎⁎0.140 |

| BMI classification | ⁎⁎-0.147 | ⁎⁎-0.119 | ⁎⁎0.094 | ⁎⁎-0.154 | ⁎⁎0.085 | |

| PA classification | ⁎⁎0.058 | ⁎⁎-0.092 | ⁎⁎0.068 | ⁎⁎-0.073 | ||

| PRE Sleeping (h·day–1) | ⁎⁎-0.094 | ⁎⁎0.453 | ⁎⁎-0.084 | |||

| PRE Smoking (cigarettes·day–1) | ⁎⁎-0.115 | ⁎⁎0.922 | ||||

| POST Sleeping (h·day–1) | ⁎⁎-0.116 |

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

2. Experimental Design, Materials and Methods

The study was approved by the university's bioethics committee (approval protocol number: 1181/02-04-2020). The participants (Table 1) were informed in writing and gave their consent before their voluntary participation. The criteria for participation in the study explicitly set by investigators were respondents: to be adults, to be residents of Greece and to have access to the Internet. The exclusion criteria were: participation in a strict weight loss control program, any form of illness, pregnancy or childbirth in the previous year.

The revised Greek version of Active-Q (online, interactive questionnaire; see Supplementary file 1_Active-Q_modyfied) [15,16] was used to calculte normal adult physical activity in exercise and sports with predefined answers. In addition, six questions about participants’ biological sex, age, weight, height, number of usual cigarettes smoked per day and total hours of sleep per day were attached to the questionnaire.

The questionnaire was freely distributed (snowball distribution) throughout Greece and participants were openly invited via email or hyperlinks hosted on social media (including publicity ads) [15]. Data collection period was from April 4 to April 19, 2020 (15 days in total). Participants completed the questionnaire twice on the same day. The first admission concerned March 2020, i.e. the first two weeks under normal living conditions before the onset of COVID-19 (PRE, condition). The second admission concerned April 2020, i.e. from April 4 to April 19, after the appearance of COVID-19 and under physical distasting measures (POST, condition). The reported activities were transformed to energy expenditure per week (MET-min/week) (according to the updated version of the 2011 Compendium of Physical Activities as adequately described in a previous article [15,20]; see Supplementary file 3_Corresponding MET values), the weight and height data were transformed to BMI and thus all respondents were classified by the online system into four PA categories based on their sporting activities (PRE condition), five age categories and four BMI categories [17], [18], [19], which corresponding to different subgroup (see Supplementary file 2_Data).

The Greek version of Active-Q, questionnaire's validity and reliability has been adequately described elsewhere [15]. Paired t–tests were performed for comparing sleeping and smoking data PRE and POST conditions in the same sample group or subgroups. Pearson product moment correlations were calculated to examine the linear relationship between PRE and POST conditions sleeping and smoking data. One way ANCOVA was used to measure any significant differences in POST condition of sleeping and smoking data-adjusted means after checking the sleeping and smoking PRE condition between subgroups. Bonferroni analytical pairwise comparisons (post hoc analysis) were also used to identify subgroup significant difference in cases where any was found. The level of statistical significance was set a priori at p ≤ 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS for windows (v23, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp., USA). Values are presented as frequency, relative frequency (%) and 95% confidence interval (CI) or means (±), standard deviations, and 95% CI.

Ethics Statement

Ethical approval was obtained by the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens review board. All participants provided their written consent in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) for experiments involving humans.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Dimitrios I. Bourdas: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Emmanouil D. Zacharakis: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration. Antonios K. Travlos: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Athanasios Souglis: Writing – review & editing. Triantafyllia I. Georgali: Writing – review & editing. Dimitrios C. Gofas: Writing – review & editing. Ioannis E. Ktistakis: Writing – review & editing. Anna Deltsidou: Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships which have, or could be perceived to have, influenced the work reported in this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank all respondents for their willingness to kindly share their life style information.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.dib.2021.107480.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N., Rubin G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bourdas D.I., Zacharakis E.D. Physical activity: COVID-19 enemy. Arch. Clin. Med. Case Rep. 2021;05:84–90. doi: 10.26502/acmcr.96550330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bourdas D.I., Zacharakis E.D. OPEN ACCESS eBooks. Sports Medicine; Las Vegas, NVUSA: 2020. Physical activity: a natural allies to prevent impending adverse effects due to the increase of isolation and physical inactivity in COVID-19 era; pp. 25–34.https://openaccessebooks.com/sports-medicine.html 89107. Accessed May 30, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maugeri G., Castrogiovanni P., Battaglia G., Pippi R., D'Agata V., Palma A., Di Rosa M., Musumeci G. The impact of physical activity on psychological health during Covid-19 pandemic in Italy. Heliyon. 2020;6:e04315. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qin F., Song Y., Nassis G.P., Zhao L., Dong Y., Zhao C., Feng Y., Zhao J. Physical activity, screen time, and emotional well-being during the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:1–16. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17145170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bourdas D.I., Zacharakis E.D., Travlos A.K., Souglis A. Return to basketball play following COVID-19 Lockdown. Sports. 2021;9:1–12. doi: 10.3390/sports9060081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Afonso P., Fonseca M., Teodoro T. Evaluation of anxiety, depression and sleep quality in full-time teleworkers. J. Public Health. 2021:1–8. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdab164. (Oxf) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alfonsi V., Gorgoni M., Scarpelli S., Zivi P., Sdoia S., Mari E., Fraschetti A., Ferlazzo F., Giannini A.M., De Gennaro L. COVID-19 lockdown and poor sleep quality: not the whole story. J. Sleep Res. 2021:1–6. doi: 10.1111/jsr.13368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bann D., Villadsen A., Maddock J., Hughes A., Ploubidis G.B., Silverwood R., Patalay P. Changes in the behavioural determinants of health during the COVID-19 pandemic: gender, socioeconomic and ethnic inequalities in five British cohort studies. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health. 2021 doi: 10.1136/jech-2020-215664. jech-2020-215664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaditis A.G., Ohler A., Gileles-Hillel A., Choshen-Hillel S., Gozal D., Bruni O., Aydinoz S., Cortese R., Kheirandish-Gozal L. Effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on sleep duration in children and adolescents: a survey across different continents. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2021:1–9. doi: 10.1002/ppul.25367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koopmann A., Georgiadou E., Reinhard I., Müller A., Lemenager T., Kiefer F., Hillemacher T. The effects of the lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic on alcohol and tobacco consumption behavior in Germany. Eur. Addict. Res. 2021;26:1–15. doi: 10.1159/000515438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carreras G., Lugo A., Stival C., Amerio A., Odone A., Pacifici R., Gallus S., Gorini G. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on smoking consumption in a large representative sample of Italian adults. Tob. Control. 2021:1–8. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gendall P., Hoek J., Stanley J., Jenkins M., Every-Palmer S. Changes in tobacco use during the 2020 COVID-19 lockdown in New Zealand. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2021;23:866–871. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntaa257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guignard R., Andler R., Quatremère G., Pasquereau A., du Roscoät E., Arwidson P., Berlin I., Nguyen-Thanh V. Changes in smoking and alcohol consumption during COVID-19-related lockdown: a cross-sectional study in France. Eur. J. Public Health. 2021:1–8. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckab054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bourdas D.I., Zacharakis E.D. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on physical activity in a sample of Greek adults. Sports. 2020;8:139. doi: 10.3390/sports8100139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bourdas D.I., Zacharakis E.D. Evolution of changes in physical activity over lockdown time: physical activity datasets of four independent adult sample groups corresponding to each of the last four of the six COVID-19 lockdown weeks in Greece. Data Br. 2020;32 doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2020.106301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Word Health Organization . WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data; Geneva: 2010. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health. [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. (2019). World health statistics 2019: monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/324835. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- 19.NHLBI Obesity Education Initiative Expert Panel on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Obesity in Adults (US). Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults: The Evidence Report. Bethesda (MD): National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; 1998 Sep. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2003/.

- 20.Ainsworth B.E., Haskell W.L., Herrmann S.D., Meckes N., Bassett D.R., Tudor-Locke C., Greer J.L., Vezina J., Whitt-Glover M.C., Leon A.S. 2011 compendium of physical activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011;43:1575–1581. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821ece12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.