Abstract

Rapid development of COVID-19 has resulted in a massive shift from traditional to online teaching. This review aims to evaluate the effectiveness of distance learning on anatomy and surgical training.

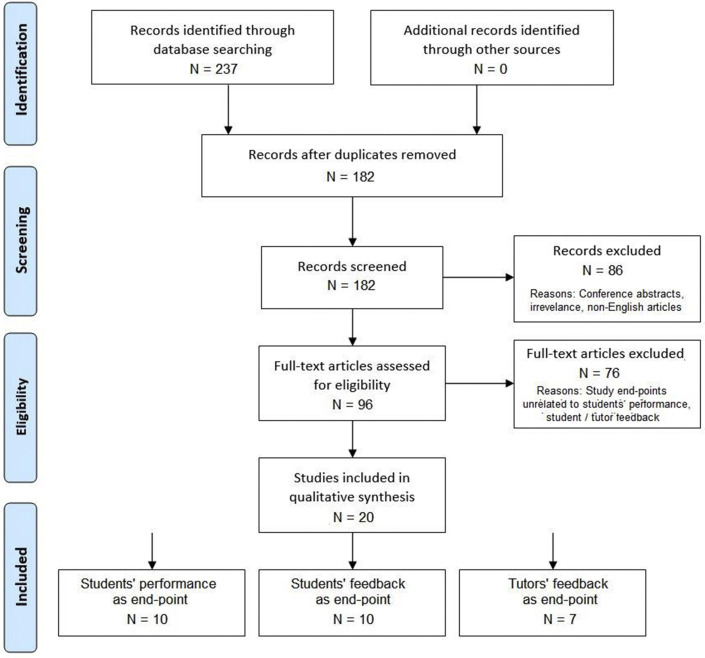

This systematic review was conducted in line with the PRISMA statement and current methodological literature. The databases CINAHL, Cochrane, EMBASE and Pubmed were searched using the search terms “Distant learning” OR “Distance learning” AND “Anatomy OR Surgery”. 182 non-duplicate studies were identified. 20 studies were included for qualitative analysis.

10 studies evaluated students' performance with distance learning. 3 studies suggested that students’ learning motivation improved with distance learning pedagogy. 5 studies found improved student performance with distance learning (performance or task completion time) when compared to conventional physical method. While 2 other studies found non-inferior student performance.

10 studies evaluated students’ feedback on distance learning. Most feedbacks were positive, with flexibility, efficiency, increased motivation and better viewing angles as the most-liked features of distance teaching. 4 studies pointed out some limitations of distance learning, including the lack of personal contact with tutor, poor network and reduced student concentration.

7 studies evaluated tutors’ feedback on distance learning. Tutors generally liked online platforms for the ease of tracking silent students, monitoring performance and updating fast-changing knowledge. Yet the lack of hands-on experience for students, technical issues and high costs are the main concerns for tutors.

In conclusion, distance learning is a feasible alternative for anatomy and surgical teaching.

Keywords: Distance learning, Surgical skills, E-learning, Anatomy

Introduction

In recent years there has been a surge in popularity for internet and online teaching tools for medical education.1 These tools were previously used to deliver didactic lectures or as an adjunct to the medical curriculum.2 , 3 In the past, there was inadequate evidence to suggest that distant education and training is sufficient to replace the medical curriculum itself.4

With the rapid development of the COVID-19 pandemic, there is an increased difficulty in securing the necessary personal protective equipment (PPE) for clinical attachment.5 In addition, there has been a gross reduction in elective surgical cases. Infection control is also a massive concern due to the possibility of outbreak within student communities.5 As a result, most teaching on the clinical premises have either been suspended or converted into online teaching methods, with a few selected sessions performed in the clinical setting.6

Anatomy teaching and surgical training require a high level of student–tutor interaction, whether or not face-to-face teaching can be replaced by distant education is still debatable. Currently, there are two main modes of distance education. E-learning is defined by the World Health Organisation as “an approach to teaching and learning, based on the use of electronic media and devices as tools for improving access to training, communication and interaction, and that facilitates the adoption of new ways of understanding and developing learning”.7 This is in contrast to distance learning, which uses a combination of eLearning and face-to-face learning. There is a shift from using traditional electronic textbooks, with or without fancy multimedia adjuncts, to a truly interactive medium.8 In the context of anatomy and surgery, flipped classrooms and active learning are commonly utilised. E-learning also entails the use of advanced-technology and multimodal teaching tools such as three-dimensional models to replicate the anatomy of the human body.9 A key characteristic of distance learning is that it can be accessed whenever and wherever, based on the learner's needs and can be tailored to target the learner's areas of improvement.

The second mode for distance education is virtual reality. Virtual reality was previously defined by Heim (1998) by the three key elements of immersion, interactivity and information intensity.10 However, this definition is rapidly developing and changing, as such, articles on virtual reality will not be systematically reviewed in this study. Other modes of learning include videoconferencing and telemedicine. Videoconferencing includes the use of applications such as Google Hangouts, Zoom and Skype to allow the clinical department to host lectures and teaching sessions11 , 12 On the other hand, telemedicine refers to the use of virtual consults to allow virtual care from home.13

Hattie suggested that educational strategies based on the teacher have been found more effective than strategies based on the students.14 Online/distance learning pedagogy, which has been widely introduced at the time of pandemic, is now considered a crucial component in medical education. This systematic review aims to evaluate the effectiveness of distance education on anatomy and surgical training from three perspective – Students' performance with distance teaching, students' feedback on distance teaching, as well as tutors’ feedback on distance teaching.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted in line with the PRISMA statement and current methodological literature. As this was a systematic review/meta-analysis, institutional review board approval was not required. Please refer to Fig. 1 for PRISMA flowchart.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow-diagram.

Data sources and eligibility

Literature search was performed on the databases - CINAHL, Cochrane, EMBASE and Pubmed on 1st October 2020. All English language articles up till the date of search were retrieved and reviewed. In addition, abstracts from bibliographies of selected studies and titles identified via an electronic search of leading journals in medical education were also retrieved and screened for relevance. A search of relevant grey literature using the same combinations of keywords was performed.

Search terms

The search terms used were combination of “Distant learning” OR “Distance learning” AND “Anatomy OR Surgery”.

Study selection

Review articles, conference abstracts were excluded. Screening of abstract was performed by two independent reviewers (Group 1: MC and KMC, Group 2: All remaining authors), where irrelevant publications (unrelated to surgical anatomy or surgical teachings) were excluded. Articles on virtual reality were also excluded, as not all virtual reality teachings were performed online (or as distant education). References from review articles were checked for cross-reference. Identical articles and abstracts were identified to avoid duplication. Studies published by the same institution were reviewed, only the most recent study or the study with most complete reporting of outcomes of interest were included to avoid data duplication. Full articles were reviewed by the authors. Studies with study-endpoints on students' performance, students' feedback on online teaching as well as tutors’ feedback on online teaching were included for analysis.

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint of the review was student performance under distance education, while secondary endpoints include feedback from students and tutors on online education.

Results

182 non-duplicate studies were identified by using the pre-defined combination of keywords, 86 articles were excluded as per review protocol. 96 full papers were reviewed by the authors, 76 articles were excluded for irrelevant study endpoints. 20 studies were included for qualitative analysis.

Students’ performance

(Table 1 ) 10 studies evaluated students’ performance with distance learning. Better student performance after e-learning was reported in various studies. In the study by Bernardo et al.,3 56 undergraduate medical students were recruited to participate in an online course as the mode of learning the theory of experimental surgery, there is a significant increase in knowledge gain assessed by pre- and post-tests (2.6 [+/− 2.0] marks, p < 0.001). For anatomy lectures, two studies making use of online teaching show positive results.15 , 16 Ferrer-Torregrosa et al. reported improved student attention and anatomy knowledge retention in study individuals after being taught with images, videos and augmented reality (5.6 for notes group, 6.54 for the video group, and 7.19 for the augmented reality group, p < 0.000).15 The mean grades of individuals having access to an online formative assessment platform (a question bank with over 400 questions) are also significantly superior to those who do not have access to it (7.1 vs 6.3, p < 0.005).16 As for surgical skills teaching, four studies on laparoscopic surgical training show non-inferior, if not better, performance results for individuals receiving online compared to face-to-face teaching.17, 18, 19, 20 The study by Rosser et al. comparing CD-ROM-based laparoscopic knowledge teaching with stand-up tutorials reports that there is a significant increment of post-teaching quiz score (p < 0.001) and no significant difference between the stand-up tutorial group and the CD-ROM group.16 Three other similar studies using laparoscopic training boxes are done to investigate the proficiency of remote laparoscopic surgical skill teaching.18, 19, 20 A study in Japan involving 20 postgraduate interns and residents were taught to do laparoscopic intracorporeal suturing via web conferencing software and laparoscopic training boxes, all participants attained proficiency and have increased post-training score (assessed by task completion time and knot error points).18 The study in Columbia by Henao et al. also showed significant improvement in laparoscopic skills quantified by pre-test and post-test scores (assessed by time required and precision) (52 vs 89) in participants receiving telesimulation via a training box.19 In a more advanced study where virtual reality is adopted in manufacturing a laparoscopic simulator called Portable Camera Aided Surgical Simulator (PortCAS), all trainees similarly show improved surgical instrument efficiency and steadiness.20 A recent study published in 2020 has evaluated and compared distance learning for undergraduate surgical skills with conventional face-to-face tutorials, the authors found comparable student performance between the two groups.21

Table 1.

Summary on students’ performance with distant learning.

| Author, Publication year | Sample Size |

Study Type | Country | UG/PG | Format | Student Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beddy, P.R. et al., 2009 | 82 | Cohort | Ireland | PG | Lecture (Clinical based tutorials) | Increased assignment submission |

| Bernardo, V. et al., 2004 | 112 | Case series | Brazil | UG | Lecture (Experimental operations) | Increased post-test score |

| Ferrer-Torregrosa et al., 2016 | 171 | Case series | Spain | UG | Lecture (Anatomy learning) | Increased test score |

| Guerri-Guttenberg, R., 2008 | 100 | Cohort study | Argentina | UG | Lecture (Anatomy learning) | Increased motivation Better grades |

| Warner, S. G. C. et al., 2014 | 38 | Case series | Int'l | PG | Lecture (Hepatobiliary surgery training) | Persisted learning by participants even after the study had ended |

| Henao, O. et al., 2013 | 20 | Case series | Columbia | PG | Surgical skills | Significant improvement in post-test scores |

| Mizota, T. K. et al., 2018 | 20 | Case series | Japan | PG | Surgical skills | Reduced task completion time |

| +Rosser, J. C. H. et al., 2000 | 52 (control) Vs 149 |

Case control | US | PG | Surgical skills | No difference in CD-ROM group and face-to-face group |

| Zahiri, M. et al., 2018 | 2 | Case study | US | Both | Surgical skills | Reduced task completion time Increased accuracy |

| Co, M et al. 2020 |

33 (control) Vs 29 |

Case control | Hong Kong | UG | Surgical skills | No difference in student performance taught by distant learning vs face to face |

(PG – Postgraduate, UG – Undergraduate, RCT – Randomized controlled trial).

Besides objective measures of student performance, multiple studies have also reported increased participation, motivation and self-initiated learning through e-learning. Peer-feedbacks from a study using e-learning website shows a significant increase in assignment completion (p < 0.01).15, 22 Students are also found to have longer attention span and better learning motivation by browsing online for related knowledge and concepts in order to complete online quizzes.2 Similar findings are observed in the use of online formative assessment platforms, where students are more willing to read relevant bibliography after encountering questions that they did wrong.16 Apart from online lectures or videos, motivation of surgeons was apparently boosted by the laparoscopic training, evidenced by increased use of the training kits for preparation of the next remote session.19 Besides, it is mentioned that accessibility to surgery stimulation devices was often limited by the high cost and large consoles that are not portable, the creation of portable laparoscopic training systems and distance learning tackles the problem of inaccessibility, which contributes to more exposure to surgical training and practices.20 Continuous and repeated access to knowledge is made possible and, perhaps even, encouraged by the use of e-learning platforms. Web analytics of an e-learning platform showed that participants continued viewing the discussions and videos repeatedly after the study period is over, suggesting that the online materials are valuable to viewers who may not have exposure to such surgery in real life.1 Increased exposure to online platforms is likely beneficial, supported by the positive correlation between time spent viewing online course materials and performance established in the study by Bernardo et al. (p < 0.001).3 Thus, the elevated motivation and continuous availability of resources serve as extra benefits of distance learning platforms.

Students’ feedback

(Table 2 ) 10 studies evaluated students’ feedback on distance learning. Over 80% of the students reported that they would apply for a hybrid program (tradition + online teaching), which may provide more freedom of scheduling to arrange their other commitments, and they can have immediate access to the whole content of course.15

Table 2.

Summary on students’ feedback on distant learning.

| Author, Publication year | Sample Size | Study Type | Country | UG/PG | Format | Feedback |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beddy, P.R. et al., 2009 | 82 | Cohort | Ireland | PG | Lecture (Clinical based tutorials) | Positive: immediate access to whole content of the course, freedom of scheduling |

| Bernardo, V. et al., 2004 | 112 | Case series | Brazil | UG | Lecture (Experimental operations) | Positive: freedom of scheduling, permanent access to online material, availability of immediate support Negative: reading from the computer screen, poor connection, too much dedication, lack of personal contact |

| Maio, M. et al., 2001 | 69 | Case series | Brazil | UG | Lecture (Clinical) | Positive: freedom of scheduling, possibility to choose the way of study, comfort of studying at home Negative: lack of personal contact with the teacher, lack of oriented exercises, losing concentration |

| Smith, P. J et al., 2013 | 517 | Case control study | Ireland | PG | Lecture (Surgical science) | Positive: better understanding of the basic and applied surgical sciences |

| Swords, C.et al., 2020 | 197 institutions | Cohort study | Worldwide | PG | Lecture (ENT) | Positive: enhanced readiness to integrate knowledge into practice, improvements in communication, clinical assessments and governance Negative: barriers included time zones, internet bandwidth, perceived difficulty of direct clinical translation of highly technical skills |

| Guerri-Guttenberg, R., 2008 | 100 | Cohort study | Argentina | UG | Lecture (Anatomy learning) | Positive: motivated them to study anatomy Encouraged them to use the recommended bibliography |

| Gul, Y. A et al., 1999 | 45 | Case series | UK | UG | Lecture (UG Surgical teaching) | Positive: willing to return for the telemedicine influenced method of tutoring |

| Moorman S. J., 2006 | 63 | Case series | US | UG | Dissection skills | Positive: see the dissection clearly through the camera Negative: poor internet connection |

| Mizota, T K., 2018 | 20 | RCT | Japan | PG | Surgical skills | Positive: remote training system was useful, increase training opportunities |

| Co, M. et al., 2020 | 33 (control) Vs 29 |

Case control study | Hong Kong | PG | Surgical skills | Positive: online demonstration is easy to follow, same as conventional teaching |

(PG – Postgraduate, UG – Undergraduate, RCT – Randomized controlled trial).

Students generally have positive feedback for distance learning including e-learning website and skills teaching. In one study, after finishing the online course, students expressed high levels of satisfaction towards the course resources (3.8 ± 1.0), and the structure and organization of the course's web pages (3.9 ± 1.3). They also believed that the e-learning platform was efficient (3.5 ± 1.2).3 In the post course questionnaires of the online course conducted by Maio et al., students rated the freedom of schedule, possibility to choose the way of study and comfort of studying at home as the most attractive aspects of e-learning.2 An anonymous questionnaire of an online surgical programme showed that 224 (90%) of 248 respondents would recommend the programme to their peers and the same percentage reported that they achieved better understanding of the basic and applied surgical sciences.23 In postgraduate level, participants in a virtual education platform involving multidisciplinary specialists of 197 institutions of 22 countries reported significant improvement in different aspects including communication, clinical assessments, clinical governance, and quality improvement (P < 0.0001).24 Concerning anatomy teaching, online formative assessment motivated a majority of students (94%) to study and use the recommended bibliography in the platform. 97.1% of students considered the online material as useful and rated ≥5 out of 10.15 Moorman also reported that in videoconferencing, students stated that the dissection demonstration could be seen clearly through the camera and allowed them to seek help and clarify information immediately as they felt teachers are always nearby.25 Positive feedback also received in multiple surgical skill training sessions. In study by Gul et al., the median score of students rating for surgical teaching utilizing video-conferencing was 9 out of 10, which is higher than 5 for traditional surgical teaching in operating theatre.26 All 46 subjects are willing to have the telemedicine influenced tutoring compared to 65% of students exposed to the conventional method. In a study in American evaluating the teaching of basic laparoscopic skills using a two-way video conference platform, 90% of the participants strongly agreed that a remote training system was useful and all agreed opportunities of practicing laparoscopic skills increased.18 A recent study in Hong Kong on final year medical students who underwent distance learning of suturing and knot tying through Zoom™ stated that online demonstration is easy to follow with 31 (96.7%) students rated ≥5 out of 5 in Likert scale and most of them (73.4%) agreed that learning of instrumental surgical knot through online lesson is same as conventional face to face teaching. Majority of students (90%) recommended the web-based suturing skills learning methods.6 To summarize, most participants in distance learning appreciate its usefulness and advantages and recommend the continuation of distance learning.

However, there are also a few studies with negative statements gathered from the students using the e-platforms. In a study by Bernardo et al., poor connection is an important issue mentioned by 37.8% of the students which affected the quality of the videos and subsequent learning3; students also reflected that they have less motivation and participation during collaborative activities and online learning requires much greater dedication which is difficult especially when they have other commitments outside the curriculum. Besides, compared to traditional learning, the lack of personal contact with the teacher is the most negative aspect reported by the students; and other drawbacks of e-learning include tying up the telephone, lack of oriented exercises, and tendency of losing concentration.1 , 15 Moreover, Swords also mentioned some barriers for e-learning, including time zones, internet bandwidth, and perceived difficulty of direct clinical translation of highly technical skills which may be more obvious in teaching of surgical skills and other more advanced techniques.24

Tutors’ feedback

(Table 3 ) 9 studies evaluated tutors' feedbacks on distance teaching. Tutors generally have very positive feedback for distance learning platforms and they at the same time explore more advantages of distance learning platforms through using the platforms or websites to teach and interact with students.27 The tutors point out that poor student participation in traditional didactic learning environments due to travelling to a central location.14 In contrast, distance learning platforms or websites can be accessed anytime and anywhere. It definitely increases the students’ participation compared with traditional didactic teaching. At the same time, web-based learning encourages continued participation thereby promoting active learning. Moreover, the use of online distance learning platforms can allow tutors to track the students who were silent and help in following their attendance.3 Tutors can monitor the students' performance more easily with regular online quizzes and assignments. Web tracking provided tutors with ideas on how things were being conducted and helped tutors identify aspects of the course that should be improved, revised or removed.3 In terms of updating the knowledge, the pace of change in scientific knowledge, surgical technology and behavioural skills is beginning to favour electronic delivery, mainly because it allows continuous updating of content.28 Online platforms can be updated instantly so tutors can offer students with the most updated information. Distance learning also allows academic collaboration and working remotely between different institutions.9 This enhances the changing of knowledge and updating the latest information by using the online platform. The teaching materials can also be shared among different institutions and it provides more resources for tutors to teach.

Table 3.

Summary on tutors’ feedback on distant learning.

| Author, Publication year | Sample Size | Study Type | Country | UG/PG | Format | Feedback |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patelis, N. M., S. J., 2020 | NA | Commentary | Greece | PG | Lecture (Vascular training) | Neutral: call for wider uptake of distant learning module |

| Smith, P. J. W. et al., 2013 | 517 | Case control study | 40 countries | PG | Lecture (Surgical examination) | Positive: Online Master of Surgical Science support academic development of trainees, evidenced by better result in MRCS examination |

| Beddy, P.R. et al., 2009 | 82 | Cohort | Ireland | PG | Lecture (Clinical based tutorials) | Positive: continued participation, promote active learning, better monitoring of student progress Negative: cost, time-consuming to establish online classroom |

| Bernardo, V. et al., 2004 | 112 | Case series | Brazil | UG | Lecture (Experimental operations) | Positive: tracking silent students and follow up, promising educational value, feedback from students help to modify teaching material Negative: lack of contact between students and teachers |

| Larvin, M., 2009 | NA | Opinion | Australia | PG | Lecture (Surgical training) | Positive: allow continuous updating of content, accessible 24/7 |

| Longhurst, G. J. S., 2020 | 14 institutes | Case series | US | UG | Lecture (Anatomy learning) | Positive: development of new online resources, academic collaboration, working remotely Negative: time constraint, lack of practice and cadaveric exposure, lack of student engagement, issue of assessment |

| Naidoo, N.A., A. Banerjee, Y., 2020 | 58 (control) Vs 58 Vs 56 |

Case control | Dubai | UG | Lecture (Anatomy learning) | Positive: tackle “integration gap”: translate anatomical concepts into clinical practice Negative: anatomy instructions in medical school were reluctant to adopt the framework |

(PG – Postgraduate, UG – Undergraduate).

Similar to students’ perception towards distance learning for surgical or anatomical related classes, a number of negative comments about anatomy learning and distance learning platforms are gathered from tutors. With regards to anatomy learning, distance learning loses the apparent edge brought upon by cadaveric-based teaching, which deprives students of practical exposure to clinical anatomy and hands-on experience. Approximately 50% of participating universities in the study of Strength, Weakness, Opportunity, Threat (SWOT) analysis of adaptations to anatomical education in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland, expressed major concerns to the lack of cadaveric teaching.9 Many tutors also reported that diminished student engagement and in-class interaction are observed in online learning environments. It also increases difficulties in maintaining teacher–student relationships. Some of the most commonly encountered difficulties are technical issues, such as unstable internet connections or lack of suitable electronic devices. In a study on feasibility of provision of distance learning programmes in surgery to Malawi, speed of internet connection in Malawi was not enough to support high-resolution images.29 Reluctance was expressed by medical faculties in adopting the online framework for anatomy education.30 In the aspect of e-learning platforms, tutors expressed that online learning classrooms are expensive, time consuming to establish and a lot of manpower is needed to give individual feedback to students for each assignment.15

Discussion

Distance teaching has gained its popularity during the period of COVID-19 due to suspension of clinical teaching at hospital areas. Distance teaching strategies ranges from online lectures (pre-recorded or live), live skills demonstrations and virtual reality. Advantages and disadvantages of various modalities of distance learning have been discussed above. This systematic review has evaluated students' performance with online pedagogy, in addition, teachers and students’ perception toward online anatomy and surgical training have also been evaluated.

Technical issues are one of the commonest problems encountered via online teaching. The unexpected change of learning modalities had left students technically unprepared for distance learning and assessment. Students reflected that internet connection problems affect their quality of learning, especially when playing videos of high resolution or during live lectures. Video recordings of surgical procedures are best to be viewed in high definition for better delineation of the relevant skills and surrounding anatomy. Intermittent communication failure also affects the progress of live interactive sessions.30 It is important for tutors to ensure adequate technical support can be provided for both tutors and students. For instance, specific areas with adequate technical equipment can be provided to students who are not equipped with such items at home. Tutors may also reserve a particular area with good internet connection for students to attend the lesson, for example the faculty's seminar rooms. User's guideline shall be provided to both students and tutors before the introduction of e-learning. Technicians should also be available during live classes and at early phases of introduction to e-learning, to avoid any technical issues resulting in any delay of the live teaching schedule.

High level of teacher-student interaction cannot be achieved via pre-recorded videos (e-learning). However, distance learning of surgical techniques such and suturing are demonstrated to be non-inferior, if not superior, in clinical trials.6 , 21 Providing students with adequate surgical equipment for hands on self-learning at home and live guidance via tele-monitoring with immediate feedback are essential elements in distance learning of surgical techniques. Co et al. also demonstrated that multiple camera viewing angles can be used to overcome the problem of two-dimensional teaching on a computer screen.6

Simulation training allows good tutor–participant interaction although distance (or online) simulation training was seldom being reported.31 Use of simulation training for surgeons has been evaluated in a systematic review by Sturn et al., in 2008.10 randomized controlled trials and 1 nonrandomized comparative study were included in that review. Simulation-based training was an addition to the normal training programs in most studies where only 1 study compared simulation-based training with patient-based training. This review concluded that participants who received simulation training performed better in laparoscopic cholecystectomy and colonoscopy/sigmoidoscopy.32 This is definitely an area to explore where surgical trainings can take place without time and geographical restrictions.

This is a systematic review on distance learning on anatomy and surgery. The design and quality of studies available was heterogeneous, ranging from commentaries and case series to randomized controlled trials, rendering systematic and pooled analysis of online anatomy and surgical education by PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome) model impossible. One of the apparent limitations of the included studies is that they evaluate the effectiveness of the programme based on voluntary questionnaires. This may give rise to reporting or publication bias in which students who find it effective or not effective are likely to fill in questionnaires more. The former may be more likely as reflected by the overwhelmingly positive responses. On the other hand, some of the studies lack objective evaluation of the effectiveness of teaching and learning but rather based on measures like the 5-point Likert scale to measure students’ subjective satisfaction with the programmes.

Studies employing lecture or theory-based learning have more objective evaluation methods such as pre- and post-quizzes. Studies on practical surgical skills do not always have objective methods. There are some viable evaluation methods that future studies should take advantage of e.g. asking trainees to mail back the suturing work for assessing knot quality and error, timing duration to finish, measuring steadiness and so forth. The study by Co et al. that evaluated online surgical skills learning has used Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills (OSATS) as an assessment tool on students' performance after online surgical skills learning.6 OSATS has been validated as a tool for objective performance assessment on surgical skills of a trainee.33 Concerning outcomes in anatomy learning, several assessments has been described - nomenclature, essays, non-spatial multiple-choice question examination (MCQE), spatial MCQE, practical examination, three-dimensional (3D) synthesis from two-dimensional (2D) views, and drawing of views, etc. Of which, spatial 3D anatomy is arguably the highest knowledge needed before an application to the clinical science of Surgery. Methods of assessment of anatomy knowledge as related to spatial abilities have been evaluated and validated in the literature.34, 35, 36, 37, 38 To assess the students' anatomy knowledge, Langlois, et al. pointed out that assessments by practical examinations, 3D synthesis from 2D views, drawing of views, cross-sections, orientation and mental rotations, would be affected by students' own spatial abilities; whereas assessment using essays and non-spatial multiple-choice questions were more correlated to students' linguistic skills.39 Also, direct correlation between students' spatial abilities test scores and technical surgical skills performance was confirmed in another study by Langlois et al.40 Of the6 various means of assessment for surgical skills, the Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE), which makes use of a series of standardized tasks and structured score sheets, has been a reliable means to assess students’ clinical competence.41 Systematic review by Sturm et al.42 and Dawe et al.43 showed that stimulation-based training was likely transferable to operative setting, and was at least non-inferior, if not advantageous, over no-training.

Another limitation of this systematic review is that there is a lack of comparison between the traditional physical teaching model and the new distance learning methods in terms of cost-effectiveness in some studies, making it questionable if these new teaching methods should still be employed if there is not an absolute need for social distancing e.g. after the COVID-19 epidemic is controlled. In addition, this systematic review included English publications only, important publications in other languages could have been missed. Lastly, most of the studies are pilot studies, having number of participants as few as 2. Thus, larger scale studies with long term follow-up will be needed to assess and conclude the long-term benefits of distance learning.

Conclusion

Distance teaching has gained its popularity during the period of COVID-19. New technologies and software have been developed to supplement the loss of clinical exposure due to the suspension of clinical teaching at hospital areas. Various modalities of teaching are adopted to facilitate students' learning, including online lectures, e-learning platforms, online anatomy teaching, surgical skills trainings and virtual reality. Both objective and subjective endpoints are promising in terms of teaching of anatomy and surgery. Distance learning is shown to be non-inferior, if not superior, in terms of surgical skills and anatomy teaching. Other benefits include easier monitoring of students' learning progress, improved participation, flexibility of learning schedule, efficiency and facilitation of academic collaboration. Technological problems, cost, lack of students’ engagement, reduced concentration and two-dimensional teaching of anatomy or surgical skills are the major issues to be handled. Although there is consensus that such mode of learning cannot completely replace traditional teaching, it does provide some benefits and serves as a proper assistance in learning during this difficult time. Hybrid mode of learning should be further explored and have a deeper understanding of distance learning and resources available.

Sources of financial support

None.

Declaration of competing interest

Michael Co and all co-authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Warner S.G., Connor S., Christophi C., Azodo I.A., Kent T., Pier D., et al. Development of an international online learning platform for hepatopancreatobiliary surgical training: a needs assessment. HPB. 2014 Dec;16(12):1127–1132. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Maio M., Ferreira M.C. Experience with the first internet-based course at the faculty of medicine. University of São Paulo. Revista do Hospital das Clinicas. 2001 May 1;56(3):69–74. doi: 10.1590/s0041-87812001000300002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernardo V., Ramos M.P., Plapler H., de Figueiredo L.F., Nader H.B., Anção M.S., et al. Web-based learning in undergraduate medical education: development and assessment of an online course on experimental surgery. Int J Med Inf. 2004 Sep 1;73(9–10):731–742. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choules A.P. The use of elearning in medical education: a review of the current situation. Postgrad Med. 2007;83(978):212–216. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2006.054189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rose S. Medical student education in the time of COVID-19. J Am Med Assoc. 2020 Jun 2;323(21):2131–2132. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5227. 10.1001/jama.2020.5227. PMID: 32232420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Co M., Chu K.M. Distant surgical teaching during COVID-19-A pilot study on final year medical students. Surg Pract. 2020 Aug;24(3):105–109. doi: 10.1111/1744-1633.12436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.E learning for undergraduate health professional education. https://www.who.int/hrh/documents/14126-eLearningReport.pdf (n.d.). Retrieved from.

- 8.Chick R.C., Clifton G.T., Peace K.M., Propper B.W., Hale D.F., Alseidi A.A., et al. Using technology to maintain the education of residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(4):729–732. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Longhurst G.J., Stone D.M., Dulohery K., Scully D., Campbell T., Smith C.F. Strength, weakness, opportunity, Threat (SWOT) analysis of the adaptations to anatomical education in the United Kingdom and republic of Ireland in response to the covid-19 pandemic. Anat Sci Educ. 2020 May;13(3):301–311. doi: 10.1002/ase.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pensieri Claudio, Pennacchini Maddalena. Overview: virtual reality in medicine. Journal of Virtual Worlds Research. 2014;7 doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-22041-3_14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moszkowicz D., Duboc H., Dubertret C., Roux D., Bretagnol F. Daily medical education for confined students during COVID-19 pandemic: a simple videoconference solution. Clin Anat. 2020;33(6):927–928. doi: 10.1002/ca.23601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzales-Zamora J.A., Alave J., De Lima-Corvino D.F., Fernandez A. Videoconferences of Infectious Diseases: an educational tool that transcends borders. A useful tool also for the current COVID-19 pandemic. Inf Med. 2020;28:135–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallo G., Trompetto M. The effects of COVID-19 on academic activities and surgical education in Italy. J Invest Surg. 2020;1–2 doi: 10.1080/08941939.2020.1748147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hattie J. Routledge; New York, NY: 2009. Visible Learning – a synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrer-Torregrosa J., Jiménez-Rodríguez M.Á., Torralba-Estelles J., Garzón-Farinós F., Pérez-Bermejo M., Fernández-Ehrling N. Distance learning ects and flipped classroom in the anatomy learning: comparative study of the use of augmented reality, video and notes. BMC Med Educ. 2016 Dec 1;16(1):230. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0757-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guerri-Guttenberg R.A. Web-based method for motivating 18-year-old anatomy students. Med Educ. 2008 Nov;42(11):1119. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosser J.C., Herman B., Risucci D.A., Murayama M., Rosser L.E., Merrell R.C. Effectiveness of a CD-ROM multimedia tutorial in transferring cognitive knowledge essential for laparoscopic skill training. Am J Surg. 2000 Apr 1;179(4):320–324. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(00)00342-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mizota T., Kurashima Y., Poudel S., Watanabe Y., Shichinohe T., Hirano S. Step-by-step training in basic laparoscopic skills using two-way web conferencing software for remote coaching: a multicenter randomized controlled study. Am J Surg. 2018 Jul 1;216(1):88–92. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henao O., Escallón J., Green J., Farcas M., Sierra J.M., Sánchez W., et al. Fundamentals of laparoscopic surgery in Colombia using telesimulation: an effective educational tool for distance learning. Biomedica. 2013 Mar;33(1):107–114. doi: 10.1590/S0120-41572013000100013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zahiri M., Booton R., Nelson C.A., Oleynikov D., Siu K.C. Virtual reality training system for anytime/anywhere acquisition of surgical skills: a pilot study. Mil Med. 2018 Mar 1;183(suppl_1):86–91. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usx138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Co M., Chung P.H., Chu K.M. Online teaching of basic surgical skills to medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a case-control study. Surg Today. 2021 Jan 25:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s00595-021-02229-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beddy P., Ridgway P.F., Beddy D., Clarke E., Traynor O., Tierney S. Defining useful surrogates for user participation in online medical learning. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2009 Oct 1;14(4):567–574. doi: 10.1007/s10459-008-9141-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith P.J., Wigmore S.J., Paisley A., Lamb P., Richards J.M., Robson A.J., et al. Distance learning improves attainment of professional milestones in the early years of surgical training. Ann Surg. 2013 Nov;258(5):838. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swords C., Bergman L., Wilson-Jeffers R., Randall D., Morris L.L., Brenner M.J., et al. Multidisciplinary tracheostomy quality improvement in the COVID-19 pandemic: building a global learning community. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2021;130(3):262–272. doi: 10.1177/0003489420941542. 0003489420941542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moorman S.J. Prof-in-a-Box: using internet-videoconferencing to assist students in the gross anatomy laboratory. BMC Med Educ. 2006 Dec;6(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-6-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gul Y.A., Wan A.C., Darzi A. Undergraduate surgical teaching utilizing telemedicine. Medical education. 1999 Aug;33(8):596–599. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patelis N., Matheiken S.J. Distance learning for vascular surgeons in the era of a pandemic. J Vasc Surg. 2020;72(1):378–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2020.04.464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larvin M. E-Learning in surgical education and training. ANZ J Surg. 2009 Mar;79(3):133–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2008.04828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mains E.A., Blackmur J.P., Dewhurst D., Ward R.M., Garden O.J., Wigmore S.J. Study on the feasibility of provision of distance learning programmes in surgery to Malawi. Surgeon. 2011 Dec 1;9(6):322–325. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2010.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naidoo N., Akhras A., Banerjee Y. Confronting the challenges of anatomy education in a competency-based medical curriculum during normal and unprecedented times (COVID-19 pandemic): pedagogical framework development and implementation. JMIR medical education. 2020;6(2) doi: 10.2196/21701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McKechnie T., Levin M., Zhou K., Freedman B., Palter V.N. Grantcharov. Virtual surgical training during COVID-19. Ann Surg: Aug. 2020;272(2):e153–e154. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sturm L.P., Windsor J.A., Cosman P.H., Cregan P., Hewett P.J., Maddern G.J. A systematic review of skills transfer after surgical simulation training. Ann Surg. 2008 Aug;248(2):166–179. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318176bf24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Niitsu H., Hirabayashi N., Yoshimitsu M., Mimura T., Taomoto J., Sugiyama Y., et al. Using the Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills (OSATS) global rating scale to evaluate the skills of surgical trainees in the operating room. Surg Today. 2013;43(3):271–275. doi: 10.1007/s00595-012-0313-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Langlois J., Bellemare C., Toulouse J., Wells G.A. Spatial abilities training in anatomy education: a systematic review. Anat Sci Educ. 2020 Jan;13(1):71–79. doi: 10.1002/ase.1873. Epub 2019 Apr 3. PMID: 30839169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luursema J.M., Vorstenbosch M., Kooloos J. Stereopsis, visuospatial ability, and virtual reality in anatomy learning. Anat Res Int. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/1493135. 1493135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yammine K., Violato C. A meta-analysis of the educational effectiveness of three-dimensional visualization technologies in teaching anatomy. Anat Sci Educ. 2015 Nov-Dec;8(6):525–538. doi: 10.1002/ase.1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moro C., Štromberga Z., Raikos A., Stirling A. The effectiveness of virtual and augmented reality in health sciences and medical anatomy. Anat Sci Educ. 2017 Nov;10(6):549–559. doi: 10.1002/ase.1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bogomolova K., van der Ham I.J.M., Dankbaar M.E.W., van den Broek W.W., Hovius S.E.R., van der Hage J.A., et al. The effect of stereoscopic augmented reality visualization on learning anatomy and the modifying effect of visual-spatial abilities: a double-center randomized controlled trial. Anat Sci Educ. 2020 Sep;13(5):558–567. doi: 10.1002/ase.1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Langlois J., Bellemare C., Toulouse J., Wells G.A. Spatial abilities and anatomy knowledge assessment: a systematic review. Anat Sci Educ. 2017;10:235–241. doi: 10.1002/ase.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Langlois J., Bellemare C., Toulouse J., Wells G.A. Spatial abilities and technical skills performance in health care: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2015;49:1065–1085. doi: 10.1111/medu.12786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martin J.A., Regehr G., Reznick R., MacRae H., Murnaghan J., Hutchison C., et al. Objective structured assessment of technical skill (OSATS) for surgical residents. Br J Surg. 1997;84:273–788. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1997.02502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sturm L.P., Windsor J.A., Cosman P.H., Cregan P., Hewett P.J., Maddern G.J. A systematic review of skills transfer after surgical simulation training. Ann Surg. 2008;248:166–179. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318176bf24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dawe S.R., Pena G.N., Broeders J.A.J.L., Cregan P.C., Hewett P.J., Maddern G.J. Systematic review of skills transfer after surgical simulation-based training. Br J Surg. 2014;101:1063–1076. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]