Abstract

Objective

To examine the effectiveness of green-Mediterranean (MED) diet, further restricted in red/processed meat, and enriched with green plants and polyphenols on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), reflected by intrahepatic fat (IHF) loss.

Design

For the DIRECT-PLUS 18-month randomized clinical trial, we assigned 294 participants with abdominal obesity/dyslipidaemia into healthy dietary guidelines (HDG), MED and green-MED weight-loss diet groups, all accompanied by physical activity. Both isocaloric MED groups consumed 28 g/day walnuts (+440 mg/day polyphenols provided). The green-MED group further consumed green tea (3–4 cups/day) and Mankai (a Wolffia globosa aquatic plant strain; 100 g/day frozen cubes) green shake (+1240 mg/day total polyphenols provided). IHF% 18-month changes were quantified continuously by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS).

Results

Participants (age=51 years; 88% men; body mass index=31.3 kg/m2; median IHF%=6.6%; mean=10.2%; 62% with NAFLD) had 89.8% 18-month retention-rate, and 78% had eligible follow-up MRS. Overall, NAFLD prevalence declined to: 54.8% (HDG), 47.9% (MED) and 31.5% (green-MED), p=0.012 between groups. Despite similar moderate weight-loss in both MED groups, green-MED group achieved almost double IHF% loss (−38.9% proportionally), as compared with MED (−19.6% proportionally; p=0.035 weight loss adjusted) and HDG (−12.2% proportionally; p<0.001). After 18 months, both MED groups had significantly higher total plasma polyphenol levels versus HDG, with higher detection of Naringenin and 2-5-dihydroxybenzoic-acid in green-MED. Greater IHF% loss was independently associated with increased Mankai and walnuts intake, decreased red/processed meat consumption, improved serum folate and adipokines/lipids biomarkers, changes in microbiome composition (beta-diversity) and specific bacteria (p<0.05 for all).

Conclusion

The new suggested strategy of green-Mediterranean diet, amplified with green plant-based proteins/polyphenols as Mankai, green tea, and walnuts, and restricted in red/processed meat can double IHF loss than other healthy nutritional strategies and reduce NAFLD in half.

Trial registration number

Keywords: fatty liver, nutrition, magnetic resonance imaging, epidemiology

Significance of this study.

What is already known on this subject?

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), a condition affecting 25% of the world population, is reflected by increased intrahepatic fat (IHF)% (>5%) and is associated with elevated liver enzymes, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular risk, as well as with decreased gut microbiome diversity and dysbiosis.

Currently, an evidence-based treatment strategy consists of general weight-loss through lifestyle interventions.

What are the new findings?

In this trial, we introduce a new concept of a green Mediterranean diet, further enriched with specific green polyphenols as Mankai, green tea, and walnuts, and restricted in red and processed meat that might lead to significantly double intrahepatic fat loss, as compared with other healthy nutritional strategies.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

Results from this study may suggest an improved dietary protocol to reduce NAFLD.

Introduction

Intrahepatic fat (IHF) accumulation, a result of intracellular triglyceride (TG) deposition in the liver, is promoted by bodily adipose tissue dysfunction and insulin resistance.1 IHF that exceeds 5%, in the absence of alcohol abuse, defines non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).2 IHF accumulation is associated with elevated liver enzymes, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular risk and extrahepatic malignancies.2 3 In recent years, the gut microbiome was suggested to have a pivotal role in NAFLD pathogenesis. This association is presumably due to the modulation of hepatic carbohydrate and lipid metabolism, with dysbiosis, that is, aberrant composition of the microbiome community, being a hallmark of the disease.4 5 NAFLD affects about a quarter of the world population6 and can progress to the development of steatohepatitis, liver-cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.2 7 The current evidence-based treatment strategy consists of weight-loss through lifestyle interventions,8 without specific dietary recommendations, although strong evidence points toward recommending the Mediterranean (MED) diet.9 MED diet, relatively rich in plant food sources, has been associated with reduced prevalence of NAFLD,10 improves cardiometabolic and cardiovascular biomarkers, and reduces all-cause mortality.11–13

Polyphenols, secondary metabolites of plants with antioxidant properties, are involved in the defence against ultraviolet radiation and pathogenic insults in the plants and have been suggested, in humans, to be protective against several malignancies, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, osteoporosis and neurodegenerative diseases,14 as well as reducing hepatic steatosis.15 The main groups of polyphenols are classified by the number of phenol rings they contain and structural elements and include phenolic acids, flavonoids, stilbenes and lignans.14 The MED diet has a relatively high content of polyphenols. In the traditional Spanish MED diet, the mean polyphenol intake was estimated to be between ~2500 and 3000 mg/day16 as compared with ~1000 mg/day in a western-style diet.17 We, and others, reported a greater decrease in NAFLD with MED diet, as compared with a low-fat diet.3 18 19 Adherence to vegetarian and plant-based diets was also associated with a lower incidence of NAFLD.20 21

In the current 18-month Dietary Intervention Randomized Controlled Trial Polyphenols Unprocessed (DIRECT PLUS), we aimed to examine the effect of MED diet, further enriched with polyphenols and lower in red and processed meat (‘green-MED’), on IHF changes, as measured by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (H-MRS). Our a priori hypothesis was that a green-MED diet may promote further effectiveness in treating NAFLD, beyond the expected beneficial effects of the MED diet.

Methods

Study design

The 18-month DIRECT-PLUS trial was initiated in May 2017 and was conducted in an isolated workplace (Nuclear Research Center Negev, Dimona, Israel), where a monitored lunch was provided. Most of the clinical and medical measurements and lifestyle-intervention sessions, were performed at the workplace’s medical department. Of the 378 volunteers, 294 met the inclusion criteria of age >30 years with abdominal obesity (waist circumference (WC): men >102 cm, women >88 cm) or dyslipidaemia (TG >150 mg/dL and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol ≤40 mg/dL for men, ≤50 mg/dL for women). Exclusion criteria are detailed in online supplemental methods 1.

gutjnl-2020-323106supp001.pdf (705KB, pdf)

Randomisation and intervention

All eligible participants who signed consent to participate in the trial and completed the baseline measurements were randomised in a 1:1:1 ratio, stratified by gender and work site (to ensure equal workplace-related lifestyle features between groups), into one of the three intervention groups: healthy dietary guidelines (HDG), MED, green-MED, all combined with physical activity (PA) accommodation. The outline of lifestyle interventions is presented in online supplemental table 1.

The interventions were initiated simultaneously, and participants were aware of their assigned intervention (open-label protocol). All the participants received free gym memberships and educational sessions to engage in moderate-intensity PA,18~80% of which included an aerobic component (online supplemental methods 2).

HDG group

In addition to PA, participants received standard nutritional counselling to promote a healthy diet and to achieve a similar intervention intensity.

MED group

In addition to PA, participants were instructed to adopt a calorie-restricted MED diet as described in our previous trials: DIRECT13 and CENTRAL.18 The MED diet assigned was rich in vegetables, with poultry and fish replacing beef and lamb. The diet also included 28 g/day of walnuts (containing 440 mg polyphenols/day; gallic acid equivalents (GAE), according to United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Phenol-Explorer: http://phenol-explorer.eu/food-processing/foods, including, mostly, ellagitannins, ellagic acid and its derivatives.22

Green-MED group

In addition to PA and the provision of 28 g/day walnuts, the green-MED diet was restricted in processed and red meat and was richer in plants and polyphenols. The participants were guided to further consume the following provided items: 3–4 cups/day of green tea and 100 g/day of frozen Wolffia globosa (Mankai strain23 24) plant frozen cubes, as a green shake replacing dinner. Both green tea and Mankai together provided additional daily intake of 800 mg polyphenols ((GAE), according to Phenol-Explorer and Eurofins lab analysis, including catechins (flavanols)) beyond the polyphenol content in the prescribed MED diet. Both the MED and green-MED diets were equally calorie-restricted (1500–1800 kcal/day for men and 1200–1400 kcal/day for women). A detailed description of the provided polyphenols is available in online supplemental methods 3.

Details regarding the lifestyle interventions and motivation techniques are provided in online supplemental methods 4. All the above polyphenols food sources (Mankai, green tea and walnuts) were provided free of charge and monitored at the on-site clinic.

Outcome measures

IHF% was assessed at baseline and after 18 months using H-MRS.25 Localised, single-voxel proton spectra were acquired using a 3.0T magnetic resonance scanner (Philips Ingenia, Best, The Netherlands). The measurements were taken from the frontal part of the right lobe, with a location determined individually for each subject using a surface, receive-only phased-array coil (full protocol is available in online supplemental methods 5). Data were analysed using Mnova software (Mestrelab Research, Santiago de Compostela, Spain) by an experienced physicist blinded to the intervention groups, who also performed visual quality control of fitted spectra. The total hepatic fat fraction in the image was determined as the ratio between the sum of the area under all fat divided by the sum of the area under all fat and water peaks.26 IHF colour images were produced using PRIDE software (by Philips).

Anthropometric parameters (ie, weight and WC) and blood biomarkers were taken at baseline, after 6 and 18 months of intervention. Assessment of nutritional intake and lifestyle habits was performed using self-reported food frequency questionnaires administered through a computer at baseline, after 6 months, and at the end of the trial.27 28 Serum folate was measured by the ECLIA competitive approach and was used as a marker for green leaf consumption.29 We used plasma samples to assess polyphenol levels. All outcomes, including laboratory methodology and microbiome analysis, are further detailed in online supplemental methods 6.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcomes of the DIRECT PLUS study were 18-month changes in IHF%, visceral adipose tissue (VAT), and adiposity (Flow chart of the study is presented in figure 1). Preliminary results indicate that 54% of the participants shared at baseline the top tertile of both—VAT and IHF levels and that after the 18-month intervention, 64% shared the top tertile of greater decline in both. A different report will be dedicated to complete VAT analysis. In the current study, we primarily aimed to assess the effect of the intervention on NAFLD, as evaluated by an 18-month change in IHF% (expressed as a percentage of total liver fat). Second, we evaluated the association of change in liver fat with the change in anthropometric parameters (weight, WC, blood pressure (BP)), blood biomarkers, cardiovascular risk scores, and specific food intake components related to the green-MED diet. Continuous variables are presented as means±SD or as medians and 25th, 75th percentile. Nominal variables are expressed as numbers and/or percentages. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to determine whether variables were normally distributed. NAFLD cut-off was set to 5% IHF, an acceptable cut-off for NAFLD initial diagnosis with radiological imaging techniques.2 As a 5.56 cut-off is also appropriate for NAFLD diagnosis,30 we performed a sensitivity analysis with this cut-off, which yielded similar results. Differences between time points were tested using the Paired sample t-test or Wilcoxon test. Differences between groups were tested using analysis of variance (ANOVA), Kruskal-Wallis test or χ2 test. Ln transformations were applied when necessary to achieve normal distribution. Correlations were tested using Spearman or Pearson correlation. Kendall Tau correlation was used to examine p-of-trend. Multiple comparisons were addressed using the Tukey post hoc test (for ANOVA) and Bonferroni correction (for Kruskal-Wallis). For adjustments and interaction models, we used general and generalised linear regression models (with the specific adjustments detailed in the results). Of 294 MRI scans of the participants, 269 were eligible for IHF% analysis at baseline due to technical reasons. Intention to treat (ITT) analysis was carried according to our previous trials: 18-month analysis for the primary outcome of IHF% included all 269 participants was conducted by imputing the missing observations for 38 individuals with missing data at 18 months by the multiple imputation technique,31 wherein the following predictors were used in the imputation model: age, sex, baseline weight and WC at 18 months.18 For missing data of body weight and WC, we used the last observation carried forward for 294 participants.18 Sample size calculation and microbiome statistical analysis are available in online supplemental methods 7 and 8. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (V.25.0) and R (V.3.6.0). Statistical significance was set at a two-sided alpha of 0.05.

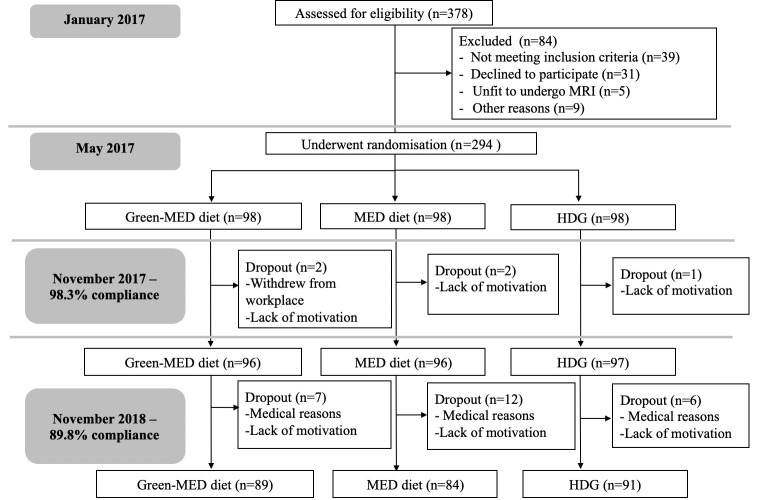

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the Dietary Intervention Randomized Controlled Trial Polyphenols Unprocessed study. HDG, healthy dietary guidelines; MED, Mediterranean.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The mean age of the participants was 51 years. 88% were men, with a mean body mass index (BMI) of 31.3 kg/m2. Baseline characteristics are presented in table 1. IHF% (ranged from 0.1% to 44.6%, median=6.6%, mean=10.2%) and NAFLD (IHF>5%) prevalence (62%), did not significantly differ between the three intervention groups (p>0.05 for all). The participants who did not have valid MRI scans at baseline (n=25), did not differ significantly from participants with valid scans (n=269) in terms of gender distribution (p=0.99) age (p=0.75), baseline weight (p=0.65) and WC (p=0.44). The participants’ median alcohol intake was 0.26 servings/day for men and 0.15 servings/day for women (correspond to 3.64 g/day and 2.1 g/day, respectively32). Lifestyle patterns, including daily alcohol and medication usage, were similarly distributed across the groups (online supplemental table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the DIRECT PLUS participants*

| Entire (n=294) |

HDG (n=98) |

MED (n=98) |

Green-MED (n=98) |

P value between groups† | |

| IHF content, %‡ | 6.6 (3.5, 15.1) | 7.0 (3.4, 15.1) | 5.9 (3.8, 14.9) | 7.7 (3.1, 17.8) | 0.62 |

| NAFLD (IHF>5%), %‡ | 62 | 63 | 60 | 62 | 0.88 |

| Obese§, % | 58.8 | 60.2 | 59.2 | 57.1 | 0.91 |

| Diabetic¶, % | 10.9 | 10.3 | 9.3 | 13.3 | 0.65 |

| Anthropometric | |||||

| Age, years | 51.1±10.5 | 51.10±10.6 | 51.68±10.4 | 50.55±10.8 | 0.76 |

| Men, number (%) | 259 (88.1) | 86 (87.8) | 86 (87.8) | 87 (88.8) | 0.97 |

| BMI, kg/m2† | 31.3±4.0 | 31.2±3.8 | 31.3±4.0 | 31.3±4.2 | 0.99 |

| Weight, kg | 93.7±14.3 | 92.9±14.7 | 94.5±13.5 | 93.6±14.9 | 0.73 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 109.7±9.5 | 109.9±10.3 | 110.0±9.5 | 109.3±8.7 | 0.86 |

| Men | 110.6±9.1 | 110.7±10.1 | 110.7±9.3 | 110.4±8.0 | 0.97 |

| Women | 103.3±9.6 | 103.8±9.7 | 105.2±9.6 | 100.8±9.9 | 0.56 |

| Diastolic-BP, mm Hg | 81.1±10.2 | 80.2±11.3 | 81.7±8.8 | 81.3±10.4 | 0.53 |

| Systolic-BP, mm Hg | 130.3±14.0 | 130.2±14.3 | 130.1±12.5 | 130.4±15.2 | 0.99 |

| Blood biomarkers | |||||

| HDL, mg/dL | 46.0±11.7 | 45.4±11.5 | 47.1±11.1 | 45.4±12.4 | 0.51 |

| Men | 44.3±10.2 | 43.4±9.9 | 46.1±10.1 | 43.3±10.7 | 0.13 |

| Women | 58.6±13.9 | 59.6±12.6 | 54.4±15.7 | 62.0±13.4 | 0.42 |

| LDL, mg/dL | 125.7±30.1 | 126.8±32.3 | 127.0±31.0 | 123.3±29.2 | 0.64 |

| TG/HDL ratio** | 3.0 (2.0, 4.5) | 3.1 (2.0, 4.8) | 2.9 (2.0, 4.6) | 2.9 (2.0, 4.3) | 0.53 |

| Cholesterol/HDL ratio | 4.4±1.3 | 4.4±1.2 | 4.3±1.3 | 4.4±1.4 | 0.82 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL** | 98.4 (92.3, 106.3) | 98.4 (91.9, 105.4) | 98.1 (92.4, 106.3) | 98.9 (92.4, 107.8) | 0.86 |

| Insulin, µU/mL** | 13.0 (9.7, 18.9) | 13.0 (9.7, 18.9) | 13.3 (10.2, 17.8) | 12.9 (9.3, 18.1) | 0.33 |

| HOMA IR** | 3.2 (2.3, 4.6) | 3.1 (2.2, 4.9) | 3.2 (2.5, 4.4) | 3.2 (2.2, 4.5) | 0.53 |

| hsCRP, mg/L** | 2.5 (1.5, 4.2) | 2.3 (1.3, 4.4) | 2.6 (1.6, 4.3) | 2.4 (1.3, 4.2) | 0.58 |

| Liver enzymes and adipokines | |||||

| ALT, U/L | 34.9±16.8 | 34.9±20.1 | 33.1±12.5 | 35.7±16.8 | 0.56 |

| AST, U/L | 25.6±7.7 | 25.9±8.6 | 25.2±6.5 | 25.8±7.9 | 0.91 |

| ALT/AST ratio | 1.3±0.4 | 1.4±0.4 | 1.3±0.4 | 1.4±0.4 | 0.60 |

| ALKP, mg/dL | 74.2±19.3 | 73.7±17.3 | 73.4±18.2 | 75.4±22.1 | 0.98 |

| Chemerin, ng/mL | 207.9±43.5 | 205.9±44.1 | 208.5±43.6 | 209.4±43.1 | 0.81 |

| FGF 21, pg/mL | 203.0±142.2 | 196.8±125.3 | 201.8±162.9 | 210.4±136.7 | 0.76 |

| Leptin, ng/mL | 14.3±12.0 | 13.7±12.2 | 15.0±12.3 | 14.3±11.5 | 0.44 |

*Values are presented as mean±SD for continuous variables (unless indicated otherwise), and as number and/or % for categorical variables.

†P values according to ANOVA/Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and χ2 for categorical variables.

‡Of 269 available H-MRS.

§BMI ≥30 kg/m2.

¶Presence of diabetes was defined for participants with baseline fasting plasma glucose levels ≥126 mg/dL or haemoglobin-A1c levels ≥6.5% or if regularly treated with oral antihyperglycaemic medications or exogenous insulin.

**Values presented as median (p25, p75).

ALKP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine transaminase; ANOVA, analysis of variance; AST, aspartate transaminase; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; HDG, heathy dietary guidelines; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; H-MRS, proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy; hsCRP, high sensitivity C reactive protein; IHF, intrahepatic fat; HOMA IR, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance; LDL, Low-density lipoprotein; MED, Mediterranean; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; TG, triglycerides.

Adherence to the intervention

The retention rate was 98.3% after 6 months and 89.8% after 18 months. 78% had eligible follow-up MRS scan. Dropout reasons were confined to a lack of motivation and medical reasons unrelated to the study. Overall, the 18-month dropout rate was not statistically different between the intervention groups (p=0.26). Baseline weight, WC and age of those 30 participants who withdrew during the trial did not differ significantly from the 264 completers (p=0.4 for gender distribution, p=0.38 for age, p=0.3 for baseline weight, p=0.63 for baseline WC). No significant difference in PA intensity level (median=28.8 MET/week) was observed between the intervention groups after 18 months of intervention (p=0.28). As previously reported21, the green-MED diet was distinguished in higher green tea and Mankai green shake intake, along with reduced red meat and poultry intake, as compared with the MED diet (p<0.05 for all comparisons between MED groups). Further information regarding adherence and macronutrient composition is reported in online supplemental results 1 and online supplemental tables 3 and 4.

18-month changes in markers of adherence to intervention: serum folate and plasma polyphenols

Serum folate levels increased across the three intervention groups (p-of-trend=0.03). The green-MED group participants increased their serum folate level by 1.1 (−0.5, 2.6) ng/dL (p<0.001 vs baseline; median change (25th, 75th percentiles)), an increase that was significantly higher compared with the HDG group (0.4 (−1.0, 1.5) ng/dL, p=0.01 between groups).

Overall, at the end of the intervention, green-MED and MED groups demonstrated significantly higher levels of total polyphenols (0.47±0.4 mg/L for both) as compared with the HDG group (0.35±0.4 mg/L; p<0.05 for both MED vs HDG). The following polyphenols were differentially detected between the groups at the end of the intervention: 2-5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (HDG: 11.9%, MED: 37.4%, green-MED: 50.7%; p<0.001) and Naringenin (HDG: 4.4%, MED: 30.4%, green-MED: 65.2%; p=0.001).

18-month changes in IHF, weight and WC

After 18 months of lifestyle intervention, weight loss (figure 2A) and WC reduction in both green-MED (−3.7±6.3 kg, −6.1±6.2 cm; p<0.001 vs baseline for both) and MED (−2.7±5.6 kg, −5.3±5.7 cm; p<0.001 vs baseline for both) diets were similar, and were higher than the reductions achieved in the HDG group (−0.4±4.7 kg, p=0.35 vs baseline; −4.0±5.6 cm, p<0.001 vs baseline; p<0.05 between HDG and MED and green-MED groups for weight loss, with mean differences of −2.3 kg, 95% CI −4.2 to −0.4 and −3.2 kg, 95% CI −5.1 to −1.4, respectively; p=0.04 between HDG and green-MED for WC loss with a mean difference of −2.1 cm, 95% CI −4.0 to −0.1).

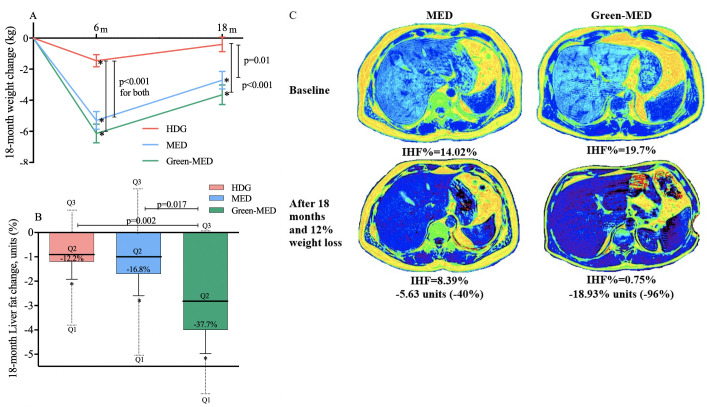

Figure 2.

(A–C)18-month changes in weight and intrahepatic fat. (A) 18-month absolute change in weight between intervention groups (ITT analysis, n=294). (B)18-month changes in IHF% between intervention groups (ITT analysis, adjusted p values for age, sex and baseline IHF%; n=269). (C) Illustrative MRI: a comparison of two male participants, similar age (46 years) and similar baseline WC (105 cm). Participant A was randomly assigned to the MED groups; participant B was assigned to the green-MED group. Both participants lost about 12% of their initial weight after 18 months and reported consuming at least 5–6 time/week walnuts (reported on 28 g/time). Total plasma polyphenol levels at the end of the intervention were higher in the green-MED participant versus MED participant (0.67 mg/L vs 0.24 mg/L). *Significant within-group change versus baseline at 0.05 level. Colour liver images were generated using pride software (by Philips). HDG, healthy dietary guidelines; IHF, intrahepatic fat; ITT, intention to treat; MED, Mediterranean; WC, waist circumference.

Participants in the green-MED group had a significantly higher reduction in IHF% (median change (25th, 75th change percentiles): −2.0% (−6.4, –0.2) absolute change, −38.9% change relative to baseline), as compared with the MED group (−1.1% (−4.7, 1.9) absolute change, −19.6% relative to baseline, p=0.023 between groups, adjusted for age, sex and baseline IHF) and HDG (−0.7% (−2.4, 1.3) absolute change, −12.2%, p<0.001 between groups, adjusted). When further adjusted for an 18-month weight loss, the difference remained significant between the two MED groups only (p=0.035). This significant difference between the two MED diets remained after we added PA and energy intake to the statistical model (p=0.047). Adjustment for VAT change, instead of weight-loss, did not change the results observed (green-MED vs HDG: p=0.006; green-MED vs MED: p=0.029). Further subgroup analysis of IHF% change by the degree of weight loss/VAT reduction is presented in online supplemental figure 1. By the end of the trial, the prevalence of NAFLD reduced from 62% to the following distribution between intervention groups: 54.8% (HDG), 47.9% (MED) and 31.5% (green-MED; p=0.012 between groups). ITT analysis for the between-group differences (figure 2B) yielded similar results. Further adjustment for weight loss resulted in a significant difference between the two MED group (p=0.024). A comparison between the per-protocol changes and ITT techniques is presented in online supplemental figure 2. Illustrative MRI of the 18-month changes in the two MED diets are presented in figure 2C. Further analysis of 18-month IHF% changes by BMI, age, NAFLD, sex, type 2 diabetes or metabolic syndrome criteria subgroups is presented in online supplemental figure 3.

Since some participants were included in a substudy related and parallel to this trial,33 we also examined the IHF% change between the substudy intervention groups, with no significant difference observed.

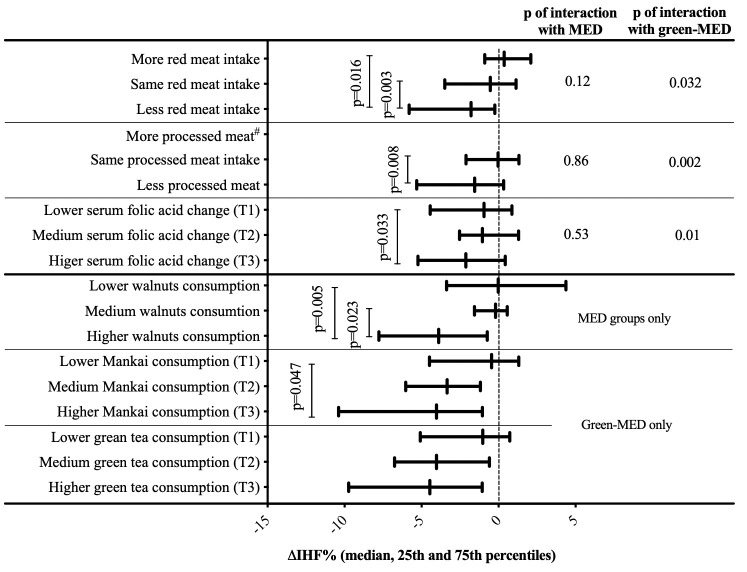

‘Green component’ and IHF loss

To clarify why the green-MED diet was more successful than the MED diet in IHF reduction, we further examined specific food components. IHF% change was inversely correlated with serum folate change (r=−0.16, p=0.02). Greater reduction in IHF was observed in participants in the top serum folate change (increase) tertile versus lowest serum folate change, and among participants who reduced red and processed meat (p<0.05 for all, figure 3). An interaction was observed for red/processed meat and serum folate with the green-MED diet, that remained significant after further adjustments for age, sex, and either baseline IHF or weight. Further analysis of the reduction in IHF% and diet components is presented in online supplemental figure 4.

Figure 3.

Changes in IHF across tertiles/categories of dietary components. Mankai shake and green tea tertiles are calculated from the weighted mean of consumption reported after 6 and 18 months of intervention. serum folate tertiles (of 18-month change in serum folate): T1≤−0.41; T2=−0.40 to 1.46; T3≥1.47; Mankai shake tertiles: T1≤1.67/week; T2=1.68 to 3.00/week; T3≥3.01/week; green tea tertiles: T1≤2/day; T2=2.01 to 3.67/day; T3≥3.68/day; walnut consumption categories: low: 0 to 1–3 times/month; medium: 1–2/week to 3–4/week; high: more than 5–6/week. Categories intervention group distribution for walnuts: low consumption: 60% MED, 40% green-MED; medium consumption: 45% MED, 55% green-MED; high consumption: 45% Med, 55% green-MED. Specific between tertiles/consumption group p values are corrected for multiple comparisons. # none of the participants reported on more processed meat. IHF, intrahepatic fat; MED, Mediterranean; T1, lowest tertile; T2, intermediate tertile; T3, highest tertile.

Increased intake of both Mankai and walnuts, as reported by the participants, was significantly associated with greater IHF% loss (p<0.05 for all; figure 3). Adjustment for either weight change or baseline IHF level did not materially attenuate the associations (p<0.05 between extreme tertiles). Of note, change in total plasma polyphenols was marginally correlated with IHF% change (r=−0.12, p=0.09).

Associations of IHF with cardiometabolic markers

At baseline, IHF% levels were correlated with anthropometric parameters, glycaemic, lipid and liver-related markers (p<0.05 for all; online supplemental figure 5). Further adjustment for age, sex and baseline weight did not affect most of the observed associations.

Eighteen-month weight and WC loss were significantly associated with IHF% loss (table 2). IHF% reduction was associated with a decline in diastolic BP, TG/HDL ratio, cholesterol/HDL ratio, fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) and chemerin (p<0.05 for all biomarkers, consistently in all three statistical models). Eighteenth-month differences in liver-related blood biomarkers between groups are presented in online supplemental figure 6.

Table 2.

Associations between 18-month intrahepatic fat change and 18-month anthropometric parameters and blood biomarkers changes

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

| Beta coefficient | P value | Beta coefficient | P value | Beta coefficient | P value | |

| Anthropometric | ||||||

| ∆Weight | 0.64 | 5.3e-25 | – | – | ||

| ∆Waist circumference | 0.56 | 3.7e-19 | – | – | ||

| ∆Systolic BP | 0.17 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.15 |

| ∆Diastolic BP | 0.28 | 1.9e-5 | 0.16 | 0.005 | 0.11 | 0.04 |

| Glycaemic biomarkers | ||||||

| ∆Glucose | 0.22 | 0.001 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.15 |

| ∆HOMA IR | 0.26 | 8.8e-5 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.49 |

| ∆Insulin | 0.28 | 2.9e-5 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.54 |

| Lipid biomarkers | ||||||

| ∆Triglycerides | 0.38 | 5.5e-9 | 0.22 | 8.1e-5 | 0.11 | 0.056 |

| ∆Cholesterol | 0.08 | 0.30 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.41 |

| ∆HDL | −0.38 | 7.9e-9 | −0.20 | 0.001 | −0.11 | 0.07 |

| ∆LDL | 0.04 | 0.51 | 0.05 | 0.40 | 0.03 | 0.61 |

| ∆TG/HDL ratio | 0.40 | 3.3E-10 | 0.25 | 2.0e-5 | 0.14 | 0.02 |

| ∆Cholesterol/HDL ratio | 0.36 | 2.6e-8 | 0.24 | 1.4e-5 | 0.15 | 0.007 |

| Liver enzymes and hepatokines | ||||||

| ∆ALT | 0.32 | 2.0e-6 | 0.2 | 0.001 | 0.1 | 0.089 |

| ∆AST | 0.13 | 0.049 | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.18 |

| ∆ALT/AST ratio | 0.36 | 6.2e-8 | 0.23 | 9.8e-5 | 0.10 | 0.069 |

| ∆ALKP | 0.03 | 0.69 | −0.001 | 0.95 | −0.008 | 0.88 |

| ∆FGF21 | 0.26 | 9.2e-5 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.03 |

| Adipokines and inflammation | ||||||

| ∆Chemerin | 0.18 | 0.007 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.001 |

| ∆Leptin | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.36 | −0.08 | 0.18 |

| ∆hsCRP | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.089 |

Model 1: adjusted for age, sex, baseline IHF% and intervention group.

Model 2: adjusted for age, sex, baseline IHF% intervention group, and 18-month waist circumference change.

Model 3: adjusted for age, sex, baseline IHF%, intervention group and 18-month weight change.

ALKP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; BP, blood pressure; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HOMA IR, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance; hsCRP, high sensitivity C reactive protein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; TG, triglycerides.

Intrahepatic fat and the gut microbiome

We next addressed the potential role of the gut microbiome in the observed association between lifestyle intervention and IHF% reduction.

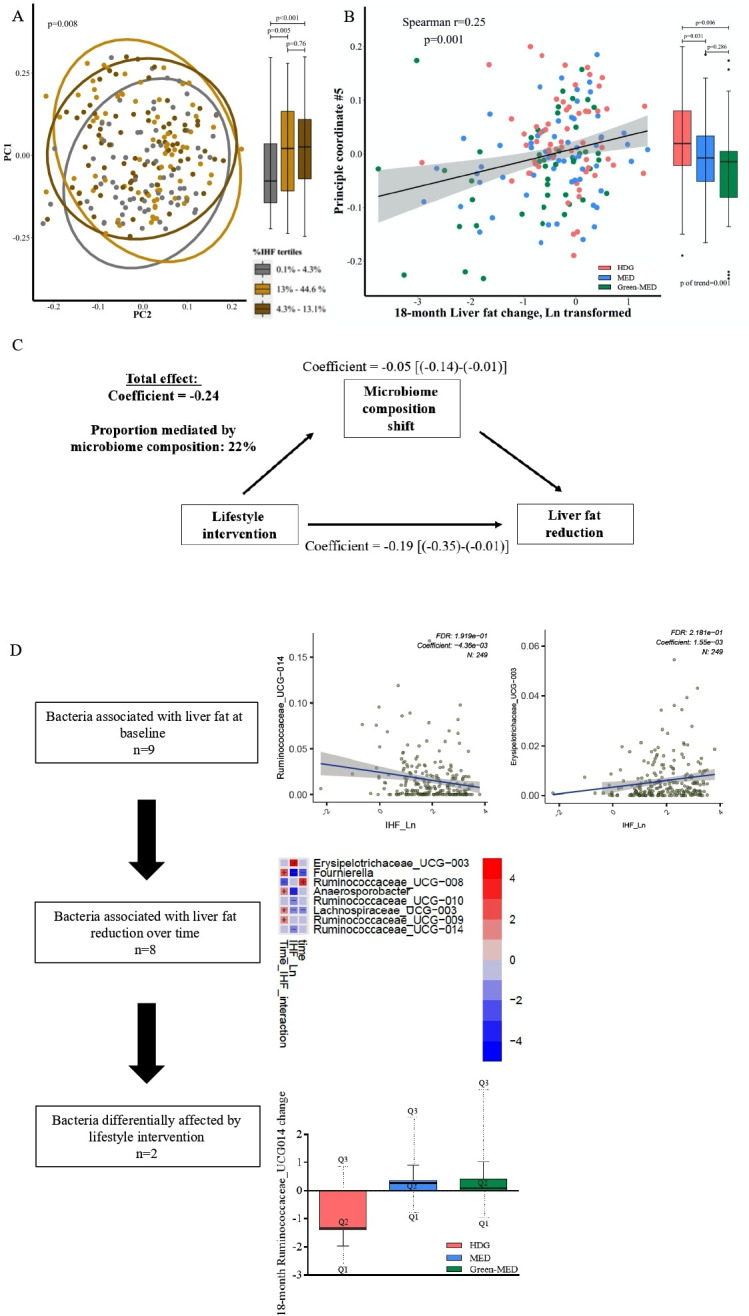

At baseline, IHF% levels were significantly associated with taxonomic composition, as assessed by global structure Permutational analysis of variance((PERMANOVA), p=0.008), and by the first principal coordinate (PCo) across IHF% tertiles (figure 4A). Concordantly, 18-month change in IHF was found to be associated with the change in the global composition, assessed by the log2 change of all operational taxonomic units (OTUs) (PERMANOVA, p=0.037). Aiming to determine whether the microbiome’s composition change had a mediatory role in the association between lifestyle intervention and IHF loss, we sought the PCo most highly correlated with IHF change (PC5; r=0.25, p=0.001; figure 4B, online supplemental figure 7), and evaluated to what extent was it affected by lifestyle intervention. PCo #5, being a surrogate for the compositional shift of the microbiome, differed across the intervention groups (p-of-trend=0.001), with a significant difference between the HDG group and the MED and green-MED groups (p=0.038 and p=0.004, respectively) (figure 4B), and no significant difference between the MED groups (p=0.268). In a mediation analysis, the compositional shift of the microbiome was estimated to account for 22% of IHF change by the lifestyle interventions (figure 4C).

Figure 4.

(A–D) Intrahepatic fat and the gut microbiome. (A) Gut microbiome composition (beta diversity) and IHF% at baseline. Gut microbiome composition and IHF, shown by principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of UniFrac distances between all baseline samples. Colours denotes 1st (grey) 2nd (yellow) and 3rd (brown) IHF% tertiles. 95% SE ellipses are shown for each tertile. Boxplots on the right describe PCo1 score by IHF% tertile. (B) Gut microbiome composition change and IHF% change. Correlation between principal component 5 (PCo5), the principal coordinate most highly correlated with IHF change (Y axis), and 18-month change in intrahepatic fat. Colours denotes lifestyle intervention group allocation. Boxplots on the right describe PCo5 score by IHF% lifestyle intervention group. (C) Mediation analysis: assessing the proportional mediatory effect of microbiome composition change (measured as PCo5) in the association between lifestyle intervention and IHF% change. (D) Stepwise identification of genus level bacteria associated with: IHF% at baseline (top, two selected bacteria), IHF% 18-month change (middle, heatmap) and with lifestyle intervention (bottom, bar plot, selected bacteria). IHF, intrahepatic fat.

Evaluating the contribution of specific bacteria to this observation, we identified nine genus-level bacteria that were significantly associated with IHF at baseline (5% of genus-level bacteria), including Fournierella, Anaerosporobacter, Lachnospiraceae_UCG-003 and several genera from the Ruminococcaceae family. Among them, eight bacteria were also found to be associated with IHF 18-month change. Next, assessing the effect of lifestyle intervention on these bacteria, the interaction between time and lifestyle intervention group was evaluated. Two specific bacteria, Fournierella and Ruminococcaceae_UCG-014 were found to be significantly affected by lifestyle intervention. However, in a mediation analysis, both bacteria were not found as significant mediators between lifestyle intervention and IHF change (figure 4D, online supplemental table 5).

Discussion

In the current study, we demonstrated that the prevalence of NAFLD was reduced in half by the strategy of exercise and green-MED diet enriched with Mankai and walnuts and restricted in red and processed meat, as reflected by increased plasma polyphenols and serum folate. Also, we found an independent association between 18-month IHF% reduction and beneficial changes in cardiometabolic, inflammatory parameters, specific gut bacteria and with global microbiota composition, which was also found to have a mediatory role in the association between lifestyle intervention and liver fat reduction. Following our previous trials suggesting that the MED diet is favourable to a low-fat diet in terms of cardiometabolic risk13 34 and IHF loss,18 this clinical trial may suggest an effective nutritional tool for the treatment of NAFLD beyond weight loss, a predicament that very little, if any effect, pharmacological treatment exists for.

Several limitations of this study should be considered. First, we had a high proportion of male participants, reflecting the profile of the workplace. This limits our ability to extrapolate our results to women. In addition, NAFLD is almost as prevalent in women as compared with men, and thus gender aspects are not fulfilled by this trial. Also, this study’s results may not be extrapolated to a population that is not abdominally obese and/or with dyslipidaemia, or a population with a lower prevalence of NAFLD than seen among our participants. Yet, the high prevalence of liver steatosis is probably a reflection of a sedentary lifestyle and unhealthy eating pattern, as our participants did not report any alcohol abuse. Second, we assessed adherence to the intervention mainly by participants’ self-reports. However, serum folate analysis, reflecting green leaf consumption29 and correlate well with nutritional self-reports,28 enabled us to objectively estimate green products’ intake. Although we measured plasma polyphenols, these measurements are limited in reflecting polyphenol intake, as only a few phenolic acids, derived from dietary polyphenol metabolism, will be present in overnight, fasted blood samples.35 The strengths of the study include the closed workplace environment, which enabled monitoring of the provided lunch, the presence of an on-site clinic at the participants’ workplace; intense dietary guidance and group meetings with multidisciplinary guidance; access to free-of-charge provided polyphenols; relatively large sample size; high retention rate; and the use of an accurate imaging technique,30 as compared with other non-invasive methods36 with high reproducibility between measurements,37 to quantify IHF%.

According to current guidelines, obese or overweight individuals are advised to undergo a moderate 5%–10% weight reduction by energy restriction.8 9 NAFLD patients are advised to change their diet (ie, reduce added sugar and reduce saturated fat) and engage in PA, both aerobic and resistance.8 In our study, participants who were instructed for HDG reduced both WC and IHF%, in accordance with a previous publication,38 whereas aerobic PA interventions in obese men and women, without weight loss, was found to be useful in the reduction of liver steatosis. The MED intervention in our study had greater efficacy in promoting adiposity (WC and weight) reduction, in addition to IHF% loss, similarly to data previously reported by us,3 18 where some fat depots, and more specifically IHF%, were effectively reduced by the MED/low carbohydrate diet than the low-fat diet, independently of VAT changes. The green-MED diet achieved the highest IHF loss, within similar weight loss as observed in the MED group, suggesting that diet composition has an effect beyond weight loss. We now add to this knowledge by demonstrating an additional benefit from the green-MED regimen, differed from the MED diet by being rich in green polyphenols and restricted in red and processed meat.

Polyphenols might play a role in reducing liver steatosis by preventing hepatocellular damage through several possible mechanisms, including reducing de novo lipogenesis, increasing fatty acid oxidation and reducing oxidative stress.15 The MED eating pattern is based mainly on increasing plant-based foods, including olive oil, along with restricted meat consumption. In our trial, we further enriched the diet with provided polyphenols, in addition to the polyphenols naturally found in the MED diet. Participants in the green-MED group were instructed to consume 3–4 cups/day of green tea containing mostly EGCG, associated with reducing liver fat, as well as liver enzymes levels, fibrosis, and inflammation39 and a daily Mankai green shake containing a mixture of flavonoids, shown to increase fatty acid oxidation in the liver, reduce inflammation by inhibition of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells, to increase adiponectin, and to reduce BP.40 Both MED groups received 28 g/day of walnuts, rich in ellagic acid, shown to improve hepatic status due to antihepatotoxic properties.41 The participants of the green-MED group had a specific detection of Naringenin (demonstrated to have a beneficial effect in liver diseases42) and 2-5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (a catabolite of the plant hormone salicylic acid43).

In addition to a greater reduction in IHF following a higher intake of polyphenols rich Mankai shake and walnuts, a decrease in red/processed meat and increased folate (probably reflecting Mankai consumption) also led to greater IHF reduction. Folate is an essential vitamin of the B vitamins family, with several important biological roles (eg, involvement in the DNA synthesis).44 Low folate levels were previously recognised as an independent risk factor of NAFLD,45 probably by affecting the expression of genes that might contribute to the accumulation of lipids in the liver.44 These results suggest that a higher intake of specific polyphenol-serum folate-rich components, in addition to a decrease in red/processed meat, might mediate a reduction of liver fat. We observed known associations of IHF% at baseline with some cardiometabolic-related biomarkers in accordance with our previous report,3 and an association between IHF change and change in FGF21 (elevated in conditions of obesity and NAFLD46). Due to our study’s nature, we cannot determine whether the change observed in these markers resulted from the reduction in IHF% and improvement in liver status or is merely a reflection of overall cardiometabolic improvement.

Previous studies have established the role of the gut microbiome in fat storage regulation in general,47 and NAFLD induction through hepatic fat storage specifically.5 We described an association between IHF% and microbiome composition at baseline, with a homogenous dysbiotic pattern among the two higher IHF% tertiles (>4.3% IHF) of our cohort. This observation is in accordance with prior evidence, associating NAFLD (>5% IHF) and gut dysbiosis.4 The family Ruminococcaceae has been consistently reported as less abundant in NAFLD,48 49 a finding we were able to reproduce at baseline in our cohort. Interestingly enough, during our trial IHF reduction was positively correlated with changes in specific Ruminococcaceae genera (Ruminococcaceae_UCG-014, Ruminococcaceae_UCG-009) and negatively correlated with change of a specific genus (Ruminococcaceae_UCG-008). This finding warrants further investigation as to the role of Ruminococcaceae in NAFLD pathogenesis and resolution. We further report a novel observation, linking IHF% change with a compositional shift in the microbiome over 18 months. This shift, in turn, partially mediated the effect of lifestyle interventions on IHF%. This mediatory effect of gut microbiome composition on IHF reduction constitutes an advancement of the observations made by others, establishing the association between the gut microbiome composition and NAFLD susceptibility.50

In conclusion, a green-MED diet, enriched with specific polyphenols and decreased red and processed meat consumption, amplifies the beneficial effect of the MED diet on hepatic fat reduction, beyond weight loss. The results of this study may suggest an improved dietary protocol to treat NAFLD.

Acknowledgments

We thank the DIRECT PLUS participants for their valuable contribution. We thank the California Walnut Commission, Wissotzky Tea Company, and Hinoman for kindly supplying food items for this study. We thank Dr Dov Brikner, Efrat Pupkin, Eyal Goshen, Avi Ben Shabat, Evyatar Cohen and Benjamin Sarusi from the Nuclear Research Center Negev; Liz Shabtai and Yulia Kovshan from Ben-Gurion University of the Negev; Andrea Angeli and Maria Ulaszewska of the Metabolomics Unit, Fondazione Edmund Mach for their valuable contributions to this study.

Footnotes

AYM and ER contributed equally.

Contributors: AYM, ER, GT, HZ, AK and IShai contributed to the data collection. AYM and ER made the statistical analysis, interpreted the data, reviewed the literature and drafted the manuscript. ER, GT, HZ, AK, PR, IShelef, IY, AS, MB, KT, CD, UV, UC, MStumvoll, FH, MStampfer and IShai contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, and reviewed the language and intellectual content of this work. AYM and IShai revised the final draft of the study and approved the final version to be published.

Funding: This work was funded by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)—Project number 209933838—Collaborative Research CenterCentre SFB1052 'Obesity Mechanisms', to I Shai (SFB-1052/B11); Israel Ministry of Health grant 87472511 (to I Shai); Israel Ministry of Science and Technology grant 3-13604 (to I Shai); California Walnuts Commission (to I Shai) and the Project 'Cabala_diet&health' (http://www.cabalaproject.eu/) which received funding from the European Union’s Horizon2020 research and innovation grant agreement No 696295—ERA-Net Cofund ERA-HDHL 'Biomarkers for Nutrition and Health implementing the JPI HDHL objectives' (https://www.healthydietforhealthylife.eu/) supported polyphenol analyses at FEM (to KT). AYM is a recipient of the Kreitman Doctoral Fellowship at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. None of the funding providers were involved in any stage of the design, conduct or analysis of the study and they had no access to the study results before publication.

Competing interests: IS advises to the Hinoman, Ltd. nutritional committee. Youngster is medical advisor for Mybiotix Ltd.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

The majority of results corresponding to the current study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary material. No further data are avialable.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The Soroka University Medical Centre Medical Ethics Board and Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol. All participants provided written informed consent and received no financial compensation.

References

- 1. van Herpen NA, Schrauwen-Hinderling VB. Lipid accumulation in non-adipose tissue and lipotoxicity. Physiol Behav 2008;94:231–41. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.11.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Byrne CD, Targher G. Nafld: a multisystem disease. J Hepatol 2015;62:S47–64. 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gepner Y, Shelef I, Komy O, et al. The beneficial effects of Mediterranean diet over low-fat diet may be mediated by decreasing hepatic fat content. J Hepatol 2019;71:379–88. 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sharpton SR, Ajmera V, Loomba R. Emerging role of the gut microbiome in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: from composition to function. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;17:296–306. 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.08.065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kolodziejczyk AA, Zheng D, Shibolet O, et al. The role of the microbiome in NAFLD and NASH. EMBO Mol Med 2019;11:e9302. 10.15252/emmm.201809302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Younossi Z, Anstee QM, Marietti M, et al. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;15:11–20. 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stefan N, Kantartzis K, Häring H-U. Causes and metabolic consequences of fatty liver. Endocr Rev 2008;29:939–60. 10.1210/er.2008-0009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zelber-Sagi S, Godos J, Salomone F. Lifestyle changes for the treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a review of observational studies and intervention trials. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2016;9:392–407. 10.1177/1756283X16638830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Plauth M, Bernal W, Dasarathy S, et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in liver disease. Clin Nutr 2019;38:485–521. 10.1016/j.clnu.2018.12.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zelber-Sagi S, Salomone F, Mlynarsky L. The Mediterranean dietary pattern as the diet of choice for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: evidence and plausible mechanisms. Liver Int 2017;37:936–49. 10.1111/liv.13435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dinu M, Pagliai G, Casini A, et al. Mediterranean diet and multiple health outcomes: an umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies and randomised trials. Eur J Clin Nutr 2018;72:30–43. 10.1038/ejcn.2017.58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts. N Engl J Med 2018;378:e34. 10.1056/NEJMoa1800389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shai I, Schwarzfuchs D, Henkin Y, et al. Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. N Engl J Med 2008;359:229–41. 10.1056/NEJMoa0708681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pandey KB, Rizvi SI. Plant polyphenols as dietary antioxidants in human health and disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2009;2:270–8. 10.4161/oxim.2.5.9498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rodriguez-Ramiro I, Vauzour D, Minihane AM. Polyphenols and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: impact and mechanisms. Proc Nutr Soc 2016;75:47–60. 10.1017/S0029665115004218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Saura-Calixto F, Serrano J, Goñi I. Intake and bioaccessibility of total polyphenols in a whole diet. Food Chem 2007;101:492–501. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.02.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chun OK, Chung SJ, Song WO. Estimated dietary flavonoid intake and major food sources of U.S. adults. J Nutr 2007;137:1244–52. 10.1093/jn/137.5.1244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gepner Y, Shelef I, Schwarzfuchs D, et al. Effect of distinct lifestyle interventions on mobilization of fat storage pools: central magnetic resonance imaging randomized controlled trial. Circulation 2018;137:1143–57. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cueto-Galán R, Barón FJ, Valdivielso P, et al. Changes in fatty liver index after consuming a Mediterranean diet: 6-year follow-up of the PREDIMED-Malaga trial. Med Clin 2017;148:435–43. 10.1016/j.medcle.2017.04.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mazidi M, Kengne AP. Higher adherence to plant-based diets are associated with lower likelihood of fatty liver. Clin Nutr 2019;38:1672–7. 10.1016/j.clnu.2018.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chiu TH, Lin M-N, Pan W-H, et al. Vegetarian diet, food substitution, and nonalcoholic fatty liver. Tzu-Chi Med J 2018;30:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Regueiro J, Sánchez-González C, Vallverdú-Queralt A, et al. Comprehensive identification of walnut polyphenols by liquid chromatography coupled to linear ion trap-Orbitrap mass spectrometry. Food Chem 2014;152:340–8. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.11.158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yaskolka Meir A, Tsaban G, Zelicha H, et al. A Green-Mediterranean diet, supplemented with Mankai duckweed, preserves Iron-Homeostasis in humans and is efficient in reversal of anemia in rats. J Nutr 2019;149:1004–11. 10.1093/jn/nxy321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sela I, Yaskolka Meir A, Brandis A, et al. Wolffia globosa-Mankai Plant-Based Protein Contains Bioactive Vitamin B12 and Is Well Absorbed in Humans. Nutrients 2020;12:3067. 10.3390/nu12103067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kukuk GM, Hittatiya K, Sprinkart AM, et al. Comparison between modified Dixon MRI techniques, MR spectroscopic relaxometry, and different histologic quantification methods in the assessment of hepatic steatosis. Eur Radiol 2015;25:2869–79. 10.1007/s00330-015-3703-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hu HH, Kim H-W, Nayak KS, et al. Comparison of fat-water MRI and single-voxel MRS in the assessment of hepatic and pancreatic fat fractions in humans. Obesity 2010;18:841–7. 10.1038/oby.2009.352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shai I, Shahar DR, Vardi H, et al. Selection of food items for inclusion in a newly developed food-frequency questionnaire. Public Health Nutr 2004;7:745–9. 10.1079/PHN2004599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shai I, Rosner BA, Shahar DR, et al. Dietary evaluation and attenuation of relative risk: multiple comparisons between blood and urinary biomarkers, food frequency, and 24-hour recall questionnaires: the DEARR study. J Nutr 2005;135:573–9. 10.1093/jn/135.3.573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Moll R, Davis B, Iron DB. Iron, vitamin B 12 and folate. Medicine 2017;45:198–203. 10.1016/j.mpmed.2017.01.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Szczepaniak LS, Nurenberg P, Leonard D, et al. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy to measure hepatic triglyceride content: prevalence of hepatic steatosis in the general population. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2005;288:E462–8. 10.1152/ajpendo.00064.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li P, Stuart EA, Allison DB. Multiple imputation: a flexible tool for handling missing data. JAMA 2015;314:1966–7. 10.1001/jama.2015.15281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bowman SA, Clemens JC, Friday JE, et al. Food Patterns Equivalents Database 2011–12: Methodology and User Guide. Food Surveys Research Group, Beltsville Human Nutrition Research Center. Agric Res Serv US Dep Agric 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rinott E, Youngster I, Meir AY, et al. Effects of Diet-Modulated autologous fecal microbiota transplantation on weight regain. Gastroenterology 2020:j.gastro.2020.08.041. 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.08.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schwarzfuchs D, Golan R, Shai I. Four-Year follow-up after two-year dietary interventions. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1373–4. 10.1056/NEJMc1204792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Spencer JPE, Abd El Mohsen MM, Minihane A-M, et al. Biomarkers of the intake of dietary polyphenols: strengths, limitations and application in nutrition research. Br J Nutr 2008;99:12–22. 10.1017/S0007114507798938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Friedrich-Rust M, Müller C, Winckler A, et al. Assessment of liver fibrosis and steatosis in pBC with FibroScan, MRI, MR-spectroscopy, and serum markers. J Clin Gastroenterol 2010;44:58–65. 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181a84b8d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. van Werven JR, Hoogduin JM, Nederveen AJ, et al. Reproducibility of 3.0 Tesla magnetic resonance spectroscopy for measuring hepatic fat content. J Magn Reson Imaging 2009;30:444–8. 10.1002/jmri.21837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Johnson NA, Sachinwalla T, Walton DW, et al. Aerobic exercise training reduces hepatic and visceral lipids in obese individuals without weight loss. Hepatology 2009;50:1105–12. 10.1002/hep.23129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chen C, Liu Q, Liu L, et al. Potential Biological Effects of (-)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate on the Treatment of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Mol Nutr Food Res 2018;62:1700483. 10.1002/mnfr.201700483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Akhlaghi M. Non-Alcoholic fatty liver disease: beneficial effects of flavonoids. Phytother Res 2016;30:1559–71. 10.1002/ptr.5667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. García-Niño WR, Zazueta C. Ellagic acid: pharmacological activities and molecular mechanisms involved in liver protection. Pharmacol Res 2015;97:84–103. 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hernández-Aquino E, Muriel P. Beneficial effects of naringenin in liver diseases: molecular mechanisms. World J Gastroenterol 2018;24:1679–707. 10.3748/wjg.v24.i16.1679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dempsey D'Maris Amick, Vlot AC, Wildermuth MC, et al. Salicylic acid biosynthesis and metabolism. Arabidopsis Book 2011;9:e0156. 10.1199/tab.0156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. da Silva RP, Kelly KB, Al Rajabi A, et al. Novel insights on interactions between folate and lipid metabolism. Biofactors 2014;40:277–83. 10.1002/biof.1154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Xia M-F, Bian H, Zhu X-P, et al. Serum folic acid levels are associated with the presence and severity of liver steatosis in Chinese adults. Clin Nutr 2018;37:1752–8. 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fisher FM, Maratos-Flier E. Understanding the physiology of FGF21. Annu Rev Physiol 2016;78:223–41. 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021115-105339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bäckhed F, Ding H, Wang T, et al. The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004;101:15718–23. 10.1073/pnas.0407076101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Da Silva HE, Teterina A, Comelli EM, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with dysbiosis independent of body mass index and insulin resistance. Sci Rep 2018;8:1466. 10.1038/s41598-018-19753-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jiang W, Wu N, Wang X, et al. Dysbiosis gut microbiota associated with inflammation and impaired mucosal immune function in intestine of humans with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Sci Rep 2015;5:8096. 10.1038/srep08096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Le Roy T, Llopis M, Lepage P, et al. Intestinal microbiota determines development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Gut 2013;62:1787–94. 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

gutjnl-2020-323106supp001.pdf (705KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

The majority of results corresponding to the current study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary material. No further data are avialable.