Abstract

Objective:

We used community-based participatory research (CBPR) to explore barriers to healthcare access and utilization and identify potentially effective intervention strategies to increase access among members of the Korean community in North Carolina (NC).

Methods:

Our CBPR partnership conducted 8 focus groups with 63 adult Korean immigrants in northwest NC and 15 individual in-depth interviews and conducted an empowerment-based community forum.

Results:

We identified 20 themes that we organized into four domains, including practical barriers to health care, negative perceptions about care, contingencies for care, and provider misconceptions about local needs. Forum attendees identified four strategies to improve Korean community health.

Conclusion:

Despite the implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), many Korean community members will continue to remain uninsured, and among those who obtain insurance, many barriers will remain. It is imperative to ensure the health of this highly neglected and vulnerable community.

Practice implications:

Potential strategies include the development of (1) low-literacy materials to educate members of the Korean community about how to access healthcare services, (2) lay health advisor programs to support navigation of service access and utilization, (3) church-based programming, and (4) provider education to reduce misconceptions about Korean community needs.

Keywords: Korean American, Immigrant, Healthcare access, CBPR, Forum

1. Introduction

The Asian population in the United States (US) grew faster than any other population between 2000 and 2010. Over the decade, the Asian population increased by 43%, and the US is now home to a large Korean diaspora community, ranking second only to China. Among Asians, Koreans are a fast-growing sub-community in the US [1]. Despite the rapid growth of the population, the needs of members of the Korean population often go unaddressed because Koreans comprise a small percentage of the total US population (about 0.5%), are often stereotyped as economically successful, and are not perceived of as experiencing health disparities. This neglect results in serious physical, behavioral, economic, and social problems [2]. For example, Koreans living in the US, including both recent Korean immigrants and more established Korean Americans, have disproportionate rates of high cholesterol; stroke; gallbladder, lung, and stomach cancer; and diabetes. Additionally, over the past two decades, rates of prostate cancer and female breast cancer rates have increased among Korean Americans by 71% and 67%, respectively [3,4]. In addition, Korean Americans also are less likely to access screenings and other preventive health services and have health insurance compared to other Asian American subgroups and many other races/ethnicities [5–7].

It is estimated that 24.1% of Korean Americans are uninsured compared to 15.7% of Asian Americans overall; 18.2% of African Americans/blacks; 17.4% of Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders; and 13.7% of non-Hispanic/Latino whites. The only group with a higher rate of being uninsured is American Indian/Alaska Natives with 29.2% being uninsured [8,9]. Koreans in North Carolina (NC) have the highest rate (55%) of being uninsured among all racial or ethnic groups (including other Asian American subgroups). This rate is five times higher than the rate among non-Hispanic/Latino whites and more than twice the overall US rate. The high rate of being uninsured is due in part to high employment in or ownership of small businesses that do not offer health insurance benefits. Korean Americans have one of the lowest rates (49%) of employer-sponsored health coverage among Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders [8]. Furthermore, the estimated number of unauthorized immigrants from Korea has been increasing rapidly from about 180,000 in 2000 to about 230,000 in 2012, an increase of 27.8% [10].

Despite insurance status, Korean Americans are less likely than other Asian Americans to access and utilize healthcare services. There has been some research to understand the barriers faced by members of Korean communities in the US. Identified reasons for not being insured or not accessing available health care when needed include language and cultural barriers, misinformation about eligibility and access, perceived discrimination, mistrust of the US healthcare system, and other family hardships such as food and housing insecurity [2,3,11–13]. However, what is known about access to healthcare services tends to be based on populations in states with large and established Korean communities. Less is known about healthcare access in parts of the US with relatively small Korean populations, such as NC [2,3]. The purpose of this study was to apply community-based participatory research (CBPR) to explore barriers to healthcare access and utilization and identify potentially effective intervention strategies to increase healthcare access and utilization among members of small Korean communities.

2. Methods

2.1. The CBPR partnership

This study was conducted by a CBPR partnership in northwestern NC with representatives from the local Korean community, including community members; organizations serving the local community, including the Korean-American Association of Greater Greensboro (KAAGG); and academic researchers from local universities. Studies suggest that working in authentic partnership with local community members, community-based organization representatives, business owners and employees, and academic researchers has the potential to develop more informed understandings of health-related phenomena and interventions that are more relevant, more culturally congruent, more likely to be adopted and maintained over time, and more likely to be successful [14–17]. Study designs that are developed in partnership with community members may be more authentic to the community and its members’ natural ways of doing things. Recruitment benchmarks, including enrollment and retention rates may be higher; measurement, more precise; data collection, more acceptable, complete, and meaningful; analysis and interpretation of findings, more accurate; and broad dissemination to impact both research and practice, more likely [18].

2.2. Development of the partnership and study conceptualization

KAAGG is a community-based organization with more than a 40-year history serving the local Korean community. Members of KAAGG include community members, organization representatives, business owners, and academic researchers. Representatives from KAAGG wanted to explore community barriers to health care and contacted behavioral scientists at Wake Forest School of Medicine to identify ways in which they could explore the low rates of healthcare access and utilization among Korean immigrants locally and uncover meaningful intervention strategies. The scientists at Wake Forest had both broad experiences in CBPR [17,19,20] and healthcare access [21–25] among another immigrant population, Hispanics/Latinos.

This emerging partnership applied for and was awarded pilot project funds from the Wake Forest University School of Medicine Translational Science Institute (TSI) Community Engagement Core. The multidisciplinary team of local community representatives and academic researchers designed and implemented this formative study. Throughout the design of the study, partnership members successfully applied CBPR principles (e.g., recognizing community as a unit of identity, harnessing community strengths, promoting co-learning and empowering processes, and addressing health from positive and ecological perspectives) [26–28] during each step of the research process – including study conception (described above), study design and conduct, data analysis and interpretation, and dissemination of findings.

2.3. Study design and conduct

The study was conducted in the Piedmont Triad region of north-central NC that includes three cities: Greensboro, Highpoint, and Winston-Salem. The combined statistical area has a population of nearly 2 million people; 2.3% identify as Asian, and 0.3% as Korean [29].

All materials for data collection were developed both in Korean and English. To increase validity, standardized guides developed by the partnership were used to introduce each methodology, outline the focus group or in-depth interview process, and lead the discussions. The guides were developed through the process including literature review; brainstorm of domains and constructs; and development, review, and revision of questions and probes and prompts. The domains of the guides are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Domains and abbreviated sample items from the focus group moderator’s and the in-depth interview guides.

| General health |

| What kinds of things do you or others in the local Korean community do to stay healthy? |

| What is the biggest worry you have about your own health? |

| What is the biggest worry you have about the health of your family? |

| What are the biggest health problems faced by Koreans in the Triad? |

| Do you ever see a healthcare professional when you are not sick (e.g., regular check-up)? If not, why? |

| Do you get regular dental care in the United States? If not, why? |

| Health access barriers |

| What are some of the barriers to getting needed care or seeing a provider in the United States for Koreans? |

| What can you say about the costs of health care in the United States? |

| How easy is it to get the health care you need in the United Sates? |

| When you saw a provider in the United Sates, how was it? |

| Tell me your thoughts about health insurance in the United States. How well insured do you think Koreans are in the Triad? |

| Thinking about what seems to encourage you or other Koreans you know to get needed care or to see a provider in the United States, what would you say are some of the things that facilitate access to these needed services? |

| How does language use affect health care among Koreans locally? |

| Conclusions |

| What would you suggest can be done to make sure that Koreans locally get the care they need? |

| Is there anything else you’d like to share today related to the health issues among Koreans? |

Participant demographic data were collected using a brief assessment that included, age; gender; country of birth; length time living in the US; educational attainment; employment status; language use at work or home; health insurance status; and whether the participant had a primary doctor.

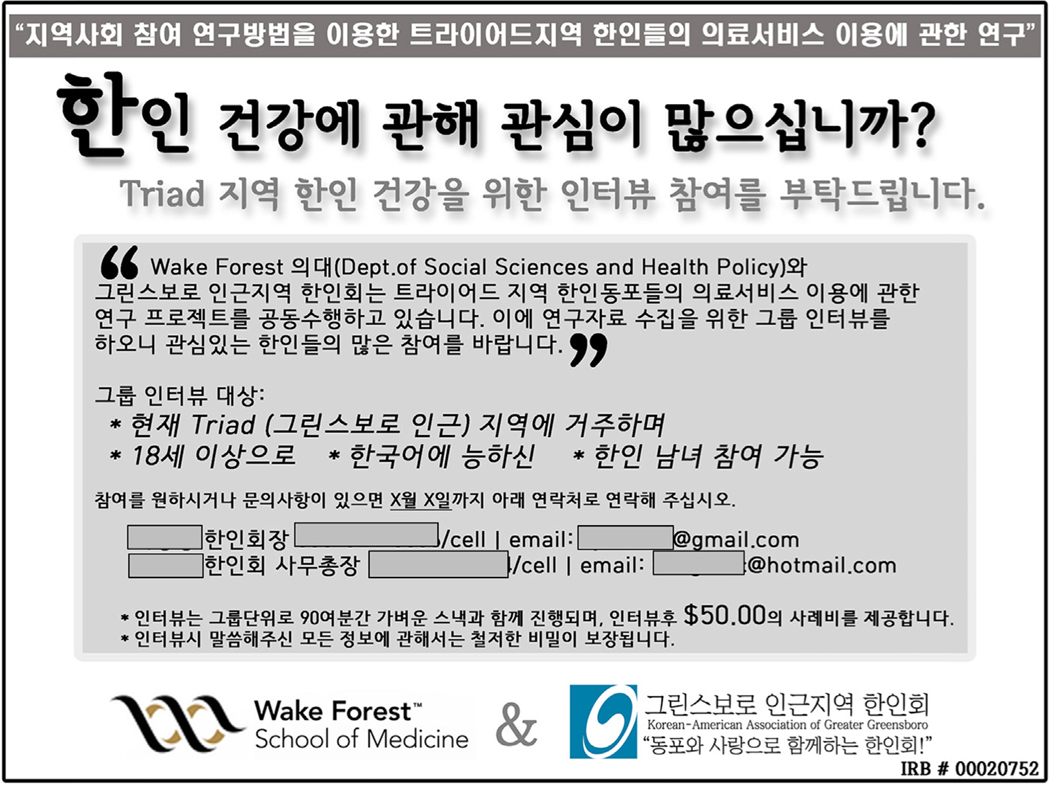

The focus groups and in-depth interviews were conducted in 2013 in the KAAGG’s office. Eligibility criteria included being ≥18 years of age; self-identifying as a Korean immigrant or Korean American; being able to speak Korean; living in study catchment area; and providing informed consent. KAAGG representatives and other Korean community leaders coordinated recruitment. The advertisements for the focus group recruitment were placed in the local Korean newspaper and posted in community settings (e.g., Korean groceries, hair shops, Korean Schools, and KAAGG office). Fig. 1 provides a sample of the Korean-language advertisement (and its translation in English).

Fig. 1.

A newspaper advertisement in Korean and English.

Purposive snowball sampling was used to ensure a broad spectrum of participants. In addition to the interviews within the Korean community, we conducted three individual in-depth interviews with staff from community health agencies. Eligibility criteria for these interviews included being ≥18 years of age; working on community health in the catchment area; and providing informed consent.

Each focus group and interview with Korean immigrant community members was audio-recorded with participant permission and conducted by one of two native Korean-speaking research staff members, with a native Korean-speaking note taker in attendance. These moderators, interviewers, and note takers were trained in these qualitative data collection methodologies and cross-cultural research. Focus groups and interviews averaged 90 and 45 min, respectively. All focus groups were grouped by gender (female vs. male) and age (≥50 vs. <50). Female focus groups and in-depth interviews were conducted by female research staff, and male focus groups and in-depth interviews were conducted by male research staff. Each focus group participant received dinner and $50.00 compensation and each in-depth interview participant received $50.00 compensation for his or her time. Participants from community health were interviewed by an English-speaking interviewer.

Human subject review and study oversight were provided by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Wake Forest School of Medicine. Signed informed consent was obtained from each participant.

2.4. Data analysis and interpretation

After each focus group and in-depth interview, representatives of the study team met to review what was heard during each focus group or in-depth interview to debrief and document impressions and plan for next focus groups and interviews.

Focus group discussions and in-depth interviews were later transcribed into English. Research suggests that collaborative analysis of qualitative data by speakers of different languages simultaneously and with iterative discussion, reflection, and negotiation of codes and themes yields higher quality and more accurate findings [30–32]. Partners read, reread, and coded transcripts; developed themes using constant comparison, an approach to grounded theory, to refine preliminary themes [33]; and worked together to reconcile and interpret themes. Our approach was well-suited for systematically uncovering participants’ meanings and furthering interpretive understandings [34]. Constant comparison combines inductive coding with simultaneous comparison, beginning with initial observations and undergoing continual refinement throughout data collection and analysis [35]. Rather than beginning the inquiry process with a preconceived notion of what was occurring, we focused on understanding the breadth of experiences and building understanding grounded in real-world patterns [36].

We explored sample characteristics using descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages or means, and standard deviations (SD) using SAS 9.2.

2.5. Community forum

Themes and their interpretation were presented during a community forum, also held in 2013, with simultaneous interpretation (Korean into English and English into Korean [the first author was the only non-Korean speaker]) to validate findings and develop recommendations to move knowledge generated into action. Forum attendees were invited by members of KAAGG and Wake Forest School of Medicine. The invitation list included everyone known by members of the CBPR partnership as working (paid and unpaid) in Korean community health in the catchment area. The forum was held in Greensboro, NC.

The focus group process, data analysis procedures, and findings and their interpretation were presented to the attendees of the community forum. Forum attendees then participated in a facilitated group discussion and brainstorming session. Five triggers, presented in Table 4, were used to lead the action-oriented discussion, moving the discussion from the concrete to the abstract. These triggers were developed previously by partnership members based on empowerment education [26,37,38]. The first three triggers were used to lead a brief discussion within the entire forum, as a large group. The fourth and fifth triggers were used to lead discussions among small groups of attendees. Small groups were assigned based on random assign-ment. Each small group assigned one member to serve as the note taker who captured in bullet-point format on newsprint their group’s discussion. One representative from each small group presented their recommendations for action to the entire group of forum attendees (Table 2).

Table 4.

Health access themes identified by domain.

| Practical barriers to care in the US exist |

| 1.Lack of bilingual services |

| “[The] number one barrier is language; the Korean language doesn’t have English translations for some medical symptoms, so it’s hard for me to describe my symptom in meaningful terms and be understood.” |

| “I can’t describe my symptoms. It clearly hurts, and I notice the symptoms. But, I can’t describe it in English.” |

| 2.Distrust of providers |

| “Nurses are not trained well enough. Sometimes, nurses do things that are supposed to be done by doctors. And, I had an occasion when I got the wrong treatment from a nurse.” |

| 3.No medical or dental insurance |

| “Here, it’s like the survival of the fittest. Health care is too expensive to pay full price. However, many Koreans are not really low income; thus, can’t benefit from government assistance programs. The middle class suffers a lot.” |

| 4.High cost of care |

| “Some people can’t afford it. Even if you can afford it, you don’t purchase health insurance here because it feels way expensive compared to the cost in Korea and what you get for it.” |

| “I’m of literally scared of the cost medical bill.” |

| 5.US health system is complicated |

| “Here [in the United States], it’s very difficult and complicated to know where to go for your symptoms. When you see a doctor, it’s common to hear that you have to go see another specialist. In Korea, you go see an eye doctor when you have symptoms in your eye. Then, all your medical needs are taken care of at that doctor’s office. But, here, there are so many specialists in eye care. You have to go to see this specialist for retina and another specialist for eye surgery, etc. |

| It’s literally impossible where to go for the particular symptom I have.” |

| 6.Difficult to get an appointment |

| “Even if you try to see a doctor, it’s very difficult to make an appointment as a new patient. It’s just hard to make an appointment.” |

| “In Korea, you can go to hospital whenever you are sick. Weekend and late night, it doesn’t matter. But here, you can’t even call your primary doctor during weekend. You can’t get a same day appointment and have to wait days to see a doctor.” |

| 7.Long waits between multiple diagnostic appointments |

| “You have to wait few weeks, sometimes few months to see a doctor, even if you have a referral and were told to go see that doctor to determine what is wrong.” |

| 8.Long waits in providers’ offices and hospitals |

| Negative perceptions about care in the US |

| 1.Health care is not comprehensive and of low quality |

| “Annual screening I had in Korea covers everything, including vision test, blood work, dental screening, endoscopy, osteoporosis, stress test, and so on.” “In Korea, the rate for stomach cancer is very high. Thus, gastroscopy in Korea is very common. However, doctors here don’t know about it. So, they just prescribe medicine when I request gastroscopy for my symptoms.” |

| 2.Interpretation services are biased in favor of providers, hospitals, and insurance companies |

| “You can’t be sure that the interpreters are on the side of the patient or the provider.” |

| 3.Care is inefficient |

| “In Korea, you walk in and get the testing and treatment you need. But here, you have to come back or go somewhere else for another test. Or, you don’t get the result right away. So, process is too slow. Then, people get frustrated and give up going to see healthcare professionals.” |

| 4.No organized effort to help Koreans’ access health care |

| “Wherever you go, you can find something in Spanish easily. Information and forms are translated into Spanish, and Spanish interpreters are available. But, there’s nothing for Koreans.” |

| Contingencies for health care are often used |

| 1.Using Internet or asking family and friends for self-diagnosis and self-treatment |

| “I just search online for my symptoms and self-diagnose. I still do this because otherwise I have to pay a co-pay on doctor’s visit even though they don’t do anything.” |

| “I ask my relatives who have had similar symptoms.” |

| 2.Choosing to go to emergency rooms to get immediate assistance/treatment |

| “Sometimes you have to go the emergency room to get care.” |

| 3.Accessing health care during trips to Korea |

| “Even with insurance here [in the US], it’s a lot cheaper to get medical treatment in Korea even with including the cost of airfare.” |

| 4.Visiting a metropolitan area (e.g., Atlanta) to see a Korean-speaking provider |

| “For some of us, we are able to go to large cities to see providers who are Korean themselves.” |

| 5.Adhering to traditional oriental medicine |

| “Korean people use oriental medicine a lot. There is oriental doctor at my church, and people here trust oriental doctors a lot. There are many people who benefit from oriental medicine. Some Korean people cured their digestive or gastric diseases with oriental treatment.” |

| Providers have misconceptions about the needs of Korean communities |

| 1.Not aware of Koreans’ needs in terms of healthcare access |

| 2.Perceive that Koreans are not to be an at-risk group compared to other “newcomer” communities (e.g., Latino immigrants) |

| 3.Assume that Koreans are well resourced and well insured |

| “I can’t imagine that there is much lacking for Korean Americans in our community; they are well educated and have the resources they need.” – County public health department provider |

Table 2.

Empowerment-based community forum triggers.

| Large group discussion |

| (1) What do you see in these findings? |

| (2) In what ways do these findings make sense to you? |

| (3) In what ways do these findings not make sense to you? |

| Small group discussion |

| (4) What can be done?/What can we all do? |

| (5) What should we be doing down the road to increase access to and utilization of health care services among immigrant Koreans? |

3. Results

3.1. Participant characteristics: focus groups and in-depth interviews

We conducted 8 focus groups with 7–8 community members each and a total of 15 in-depth interviews with formal and informal community leaders (12 individual in-depth interview participants were members of the Korean immigrant community and 3 were conducted with public health providers). A total of 63 Korean immigrants participated in focus groups. All focus group participants reported being born in Korea (n = 63); about half were female. Mean age was 50 (range 18–81) years; mean number of years in the US was 17 years; 56 (90%) participants reported achieving more than a high school education; 41 (66%) reported currently working full time; and 28 (44%) reported being small business owners. Most prevalent (30%) type of business owned was a dry cleaner. Forty-nine (78%) participants reported speaking only Korean or more Korean than English. Twenty-nine (44%) reported not having health insurance.

We also conducted 15 in-depth interviews with formal and informal community leaders, who have experience serving the Korean community. Interview participants included representatives from the Korean (n = 12) and non-Korean (n = 3) communities. Interview participants included small business owners, community organization leaders, pastoral association leaders, health providers, and community health agency staff. Mean age of in-depth interviews (Korean only) was 57 (range 41–75) years. Selected characteristics of focus group and in-depth interview participants are provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Selected characteristics of focus group and in-depth interview participants.

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) or N (%), as appropriate | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Focus group (N =63) | In-depth interview (N = 12a) | |

|

| ||

| Age in years | 49.6 (SD = 14.2) | 56.8 (SD= 11) |

| Total months living in US | 202.6 (SD= 115.2) | 310.25 (SD= 162.4) |

| Total number of trips to Korea in past 3 years | 0.6 (SD = 0.97) | 1.1 (SD= 1.16) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 31 (49%) | 5 (42%) |

| Male | 32 (51%) | 7 (58%) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 7 (11%) | 1 (8%) |

| Married | 51(81%) | 10 (83%) |

| Divorced | 2 (3%) | 1 (8%) |

| Widowed | 3 (5%) | 0 |

| Educational attainment | ||

| Less than high school education | 6(10%) | 0 |

| High school or equivalent education | 13(21%) | 2(17%) |

| Some college education | 11 (18%) | 0 |

| College education | 22 (35%) | 7 (58%) |

| More than college education | 10 (13%) | 3 (25%) |

| Currently employed (including full/part time) | ||

| Yes | 49 (78%) | 9 (75%) |

| No | 14 (22%) | 3 (25%) |

| Small business owners | ||

| Yes | 28 (44%) | 4 (33%) |

| No | 35 (56%) | 8 (67%) |

| Language use | ||

| Only Korean | 13(21%) | 2(17%) |

| More Korean than English | 36 (57%) | 5 (42%) |

| Both equally | 10(16%) | 3 (25%) |

| More English than Korean | 4 (6%) | 2(17%) |

| Health insurance | ||

| Yes | 29 (46%) | 10 (83%) |

| No | 34 (54%) | 2(17%) |

| Primary provider | ||

| Yes | 25 (40%) | 9 (75%) |

| No | 38 (60%) | 3 (25%) |

Korean only; 3 additional in-depth interviews were conducted with public health staff who were not Korean.

3.2. Qualitative findings

Qualitative data analysis identified 20 themes. We organized into four main domains, including practical barriers to care in the US; negative perceptions about care in the US; contingencies for health care; and provider misconceptions about the Korean community. Domains, themes, and sample quotations are presented in Table 4.

3.2.1. Practical barriers to care in the US exist

Eight practical barriers to care were identified. First, participants reported that because they could not speak English fluently and local providers had no Korean-language capacity, it was difficult to make appointments and communicate symptoms. Moreover, there are no English translations for certain medical symptoms described in Korean. For example, participants noted that the word “ ” (“dab-dab-hae”), which is often used by Korean patients with heart or gastroenteric problems, has no proper English translation.

” (“dab-dab-hae”), which is often used by Korean patients with heart or gastroenteric problems, has no proper English translation.

Also, participants perceived providers not to be trustworthy. Some participants reported experiences of providers misdiagnosing patients (perhaps due to language barriers and lack of cultural understanding), which delayed the time to get a correct diagnosis and treatment.

Third, participants noted that health care is expensive and thus out of reach. Participants also reported that dentists seem particularly expensive, therefore making it less appealing to seek dental services than healthcare services. Moreover, the majority of participants reported not having any kind of medical or dental insurance. Participants with insurance felt that their coverage did not meet their expectations and therefore they reported having little motivation to maintain coverage.

Fifth, participants reported that the US healthcare system is complicated, and there was a lack of information on providers and services (including public health services such as immunizations). They also reported that billing systems are confusing and that they do not receive sufficient details about what the fees cover and what is paid for by insurance.

Most participants were not aware of charity financial support, social services, or installment payment plans. A participant with insurance noted that there has been a high error rate on bills he and his family received, which only reduced his confidence in the healthcare system overall.

Participants reported that the actual process of getting an appointment with a provider is challenging. One cannot merely make a call and get an appointment for the same day. Participants also noted long waits between multiple diagnostic appointments and encountering long waits after arriving for a scheduled appointment.

3.2.2. Negative perceptions about care in the US

Participants shared four negative perceptions they had about US health care. First, participants reported that health care was not as comprehensive and of the same quality compared to care received in Korea. Some participants reported wanting and expecting to have endoscopies or colonoscopies during routine provider visits (“check-ups”). Although most providers in the US do not recommend the procedures routinely, the lack of explanation to their patients resulted in increasing distrust of providers and decreased perceived importance of regular provider visits.

Second, participants reported that interpretation services seem biased toward providers, hospitals, and insurance companies. They did not think that crucial information was being communicated through interpreters and what was being communicated was designed to support the bottom line of the provider, hospital, or insurer rather than to ensure the health of the individual.

Participants also perceived that obtaining care in the US is inefficient. They reported that they cannot get all needed services in one place, and instead they need to travel to several different places to get care. Participants concluded that they have often missed properly timed treatments when sick because of this seemingly inefficient and disjointed system.

Finally, participants noted that there is no organized effort to support Koreans to access health care. In fact, they noted that immigrant Hispanic/Latino communities seem to have more organized efforts to facilitate their access to health care.

3.2.3. Contingencies for health care are often used

Because of these barriers and negative perceptions described, participants described five alternatives to meeting their healthcare needs in the US. First, participants noted that many use the Internet rather than seek formal health care to self-diagnose. They also reported relying on the advice and guidance from family and friends. Second, some participants mentioned that some choose to go to emergency departments to receive care. Participants also noted that some may travel to Korea to obtain routine and more serious care (e.g., cancer diagnosis and treatment) as well as purchasing prescription drugs (e.g., antibiotics).

Fourth, some participants reported visiting larger cities in the US (e.g., Atlanta, GA) where Korean-speaking providers are available. They reported that health care received from Korean-speaking providers was more culturally congruent; they could get the examinations and tests that they expected and needed. The final alternative to health care that emerged was the use of traditional Korean oriental medicine to maintain health and treat illness.

3.2.4. Providers have misconceptions about the needs of members of Korean communities

Participants from community health agencies were not aware of the healthcare needs and priorities of the local Korean communities. They perceived them not to be an “at-risk” group compared to other immigrant communities and perceived them to be better resourced and well insured.

3.3. Community forum

Community forum attendees (n = 40) included representatives from local Korean-serving churches, the Korean American Senior Association, university and college faculty, business owners, healthcare providers, the Korean School of Greensboro, and second-generation Korean Americans. After reviewing findings from the focus groups and in-depth interviews and engaging in a half-day facilitated discussion using the triggers outlined in Table 3, forum attendees identified four priorities for research and practice to improve the health and well-being of the Korean community.

First, they suggested the development of resource materials designed to educate the Korean community. For example, in simple Korean, a booklet could explain the healthcare system in the US, including types of services available at different types of healthcare providers (e.g., public health departments, free clinics, and hospitals); eligibility for services; ways to access these services; and how to obtain insurance. Forum attendees reported that the processes for accessing healthcare services must be “de-mystified” to ensure appropriate use. Information must be presented in a simple and tailored manner, including the names and locations of healthcare venues and providers.

Forum attendees also noted that a volunteer program that harnessed community-identified assets should be developed in order to improve access to healthcare services. Community members could be trained to serve as health navigators or lay health advisors to help with transportation, interpretation, and navigation of insurance options as examples.

Third, attendees suggested that church-based health ministries should be established to provide educational seminars related to health promotion and disease prevention; health screenings; and referrals to providers. Attendees also suggested that health ministries could raise money for those in need of financial assistance for diagnosis, care, and treatment.

Finally, attendees asserted that providers needed to be educated about the health needs and priorities of Korean and Asian communities in order to dispel stereotypes and provide the most culturally congruent care.

4. Discussion and conclusion

Currently, there are nearly 2 million people of Korean descent living in the US [1]. Little is understood about health needs of the Korean communities in the US in general and in parts of the country like NC with relatively small Korean populations.

Our findings suggest that the Korean population in NC has profound practical barriers to health care and reported having negative perceptions about care in the US. Rather than using formalized care, participants reported using contingencies for care including the Internet, relying on family and friends for health advice, and adhering to traditional oriental medicine. Furthermore, participants representing community health agencies had misconceptions about the needs of the Korean population.

The use of lay health advisors is a strategy that has been widely promoted to reduce health disparities among populations that are difficult for researchers and practitioners to reach [4,39,40]. Although strategies that train and support informal leaders within communities to provide information, guidance, and support within their naturally existing social networks sound commonsensical, there remain much needed research within all communities to illustrate effectiveness in improving health outcomes within communities and populations [39–41]. This gap provides a research opportunity because the use of lay health advisors may prove to be highly effective among populations, including some Korean communities, who may be culturally and linguistically isolated from health care. Furthermore, lay health advisors may be harnessed to implement priorities that emerged from the community forum. For example, the development and distribution of materials to provide information and resources for members of local Korean communities could be implemented by lay health advisors, who by definition are members the community they serve. They know what is meaningful for those within their networks. Lay health advisors also may be able to facilitate access to health care, including enrollment in Obamacare through the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), based on eligibility.

There have been examples of lay health advisors working in a variety of settings, including churches [39–41]. Church-based health ministries might reach many of those who are not connected to health care, do not understand healthcare delivery, and/or need assistance to navigate the system for routine, primary, and specialty care. Finally, lay health advisors could raise consciousness among providers about community health needs and priorities, educate providers on community experiences trying to access and utilize healthcare services, increase cultural congruence, and debunk existing stereotypes providers have about the needs, priorities, and resources of the Korean population. This may be particularly important in areas with small Korean populations given the potential lack of Korean community visibility.

4.1. Limitations

Participant selection was based on a convenience sample of Korean immigrants ages 18 and above and, therefore, the findings cannot be generalized to all Korean communities or those living within this region specifically. However, for the purposes of formative research, the findings from this study may inform efforts to increase access to needed health care among those from similar communities (i.e., communities with small Korean populations) and backgrounds. Further research using alternate data collection methodologies, will provide further data and insights into health access within this community.

4.2. Conclusions

This study was implemented before the implementation of the ACA; however, the ACA bars undocumented or recent legal immigrants from receiving financial assistance for health insurance [42]. Thus, many members of the local Korean community will continue to remain uninsured. Furthermore, many of the barriers uncovered in this study will not be reduced by the ACA. It is imperative to apply strategies how to ensure the health and well-being of this neglected and vulnerable community.

4.3. Practice implications

We identified barriers to and misconceptions about US health care, but we also uncovered potential strategies that may be adopted to improve access to care among the Korean populations. These strategies emerged from our empowerment-based methodology and included the development of low-literacy materials to educate members of the Korean community about how to access healthcare services, lay health advisor programs to support navigation of service access and utilization, and church-based programming. These strategies are not mutually exclusive and may be synergized to work together to meet the needs and priorities of Korean communities.

Educating US providers, particularly those in communities that have had traditionally small Korean populations, must be a priority. Providers may be unaware of the needs of these communities. Up to 20% of Korean community members in NC are undocumented [10] and thus do not fit the stereotypes that emerged. Furthermore, the Korean population in the US is rapidly growing, and with this growth we are certain to see much more diversity in terms of health priorities and needs; stereotypes will only contribute to health disparities that we already see among Koreans in the US.

Acknowledgements

Support for this project was provided by the Wake Forest School of Medicine Translational Science Institute. We thank members of the Korean American Association of Greater Greensboro (KAAGG), Korean-American Senior Citizen Association, the Korean School of Greensboro, and the Triad Korean Pastoral Fellowship. We also thank the interviewers, transcriptionists, and participants.

References

- [1].Hoeffel EM, Rastogi S, Ouk Kim M, Shahid H. The Asian Population, 2010. 2010 census briefs, 2012; 2010, Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/cr-11.pdf [retrieved 28.02.14].

- [2].De Gagne JC, Oh J, So A, Kim SS. The healthcare experiences of Koreans living in North Carolina: a mixed methods study. Health Soc Care Community 2014;2≥417–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lee J, Demissie K, Lu SE, Rhoads GG. Cancer incidence among Korean-American immigrants in the United States and native Koreans in South Korea. Cancer Control 2007;14:78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Institute of Medicine. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic dis- parities in health care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Choi KS, Lee S, Park EC, Kwak MS, Spring BJ, Juon HS. Comparison of breast cancer screening rates between Korean women in America versus Korea. J Womens Health 2010;19:1089–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Maxwell AE, Crespi CM, Alano RE, Sudan M, Bastani R. Health risk behaviors among five Asian American subgroups in California: identifying intervention priorities. J Immigr Minor Health 2012;14:890–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ma GX, Wang MQ, Toubbeh J, Tan Y, Shive S, Wu D. Factors associated with colorectal cancer screening among Cambodians, Vietnamese. Koreans and Chinese living in the United States. North Am J Med Sci 2012;5:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kaiser Family Foundation. Health coverage and access to care among Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders. Race, ethnicity and health care fact sheet; 2008, Available at: http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/7745.pdf [retrieved 28.02.14]. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Huang A. Disparities in health insurance coverage among Asian Americans. Harvard Asian American Policy Review; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Baker B, Rytina N. Estimates of the unauthorized immigrant population residing in the United States: January 2012, in population estimates. US Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Shin H, Kim MT, Juon HS, Kim J, Kim KB. Patterns and factors associated with health care utilization among Korean American elderly. Asian Am Pac Isl J Health 2000;8:116–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kaiser Family Foundation. Health care coverage and access to care among Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Nadimpalli SB, Hutchinson MK. An integrative review of relationships between discrimination and Asian American health. J Nurs Scholarsh 2012;44:127–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Eng E, Moore KS, Rhodes SD, Griffith D, Allison L, Shirah K, Mebane E. Insiders and outsiders assess who is “the community”: participant observation, key infor- mant interview, focus group interview, and community forum. In: Israel BA, et al. , editors. Methods for conducting community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005. p. 77–100. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Wallerstein N, Oetzel J, Duran B, Tafoya G, Belone L, Rae R. What predicts outcomes in CBPR? In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-based participatory research: from process to outcomes. San Francisco, CA: Wiley; 2008. p. 371–92. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Cashman SB, Adeky S, Allen AJ, Corburn J, Israel BA, Montaño J, et al. The power and the promise: working with communities to analyze data, interpret findings, and get to outcomes. Am J Public Health 2008;98:1407–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Rhodes SD, Duck S, Alonzo J, Downs M, Aronson RE. Intervention trials in community-based participatory research. In: Blumenthal D, et al. , editors. Community-based participatory research: issues, methods, and translation to practice. NY: Springer; 2013. p. 157–80. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Rhodes SD, Duck S, Alonzo J, Daniel J, Aronson RE. Using community-based participatory research to prevent HIV disparities: assumptions and opportunities identified by the Latino Partnership. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;63:S32–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Rhodes SD. Authentic engagement and community-based participatory research for public health and medicine. In: Rhodes SD, editor. Innovations in HIV prevention research and practice through community engagement. NY: Springer; 2014. p. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Rhodes SD, Mann L, Alonzo J, Downs M, Abraham C, Miller C, et al. CBPR to prevent HIV within ethnic, sexual, and gender minority communities: successes with long-term sustainability. In: Rhodes SD, editor. Innovations in HIV prevention research and practice through community engagement. New York, NY: Springer; 2014. p. 135–60. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rhodes SD, Fernandez FM, Leichliter JS, Vissman AT, Duck S, O’Brien MC, et al. Medications for sexual health available from non-medical sources: a need for increased access to healthcare and education among immigrant Latinos in the rural southeastern USA. J Immigr Minor Health 2011;13:1183–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Zometa C, Lindstrom K, Montaño J. Characteristics of immigrant Latino men who utilize formal healthcare services in rural North Carolina: baseline findings from the HoMBReS Study. J Natl Med Assoc 2008;100:1177–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Song EY, Vissman AT, Alonzo J, Bloom FR, Leichliter JS, Rhodes SD. The use of prescription medications obtained from non-medical sources among immigrant Latinos in the rural southeastern US. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2012;23:678–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Vissman AT, Bloom FR, Leichliter JS, Bachmann LH, Montaño J, Topmiller M, et al. Exploring the use of nonmedical sources of prescription drugs among immigrant Latinos in the rural southeastern USA. J Rural Health 2011;27: 159–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Vissman AT, Hergenrather KC, Rojas G, Langdon SE, Wilkin AM, Rhodes SD. Applying the theory of planned behavior to explore HAART adherence among HIV-positive immigrant Latinos: elicitation interview results. Patient Educ Couns 2011;85:454–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Vissman AT, Stowers J, Davis AB, Hannah A, et al. Boys must be men, and men must have sex with women: a qualitative CBPR study to explore sexual risk among African American, Latino, and white gay men and MSM. Am J Men’s Health 2011;5:140–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA. Introduction to methods in community- based participatory research for health. In: Israel BA, et al. , editors. Methods in community-based participatory research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Rhodes SD. Demonstrated effectiveness and potential of CBPR for preventing HIV in Latino populations. In: Organista KC, editor. HIV prevention with latinos: theory, research, and practice. New York, NY: Oxford; 2012. p. 83–102. [Google Scholar]

- [29].US Census Bureau. 2008. –2012 American community survey 5-year estimates. American Fact Finder; 2012, Retrieved from: http://www.census.gov/acs/www/data_documentation/2012_release/ [accessed 28.07.14].

- [30].Lukens EP, Thorning H, Lohrer S . Sibling perspectives on severe mental illness: reflections on self and family. Am J Orthopsychiatry 2004;74:489–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].MacQueen KM, McLellan E, Kay K, Milstein B. Codebook development for a team-based qualitative analysis. Cult Anthropol Methods 1998;10:31–6. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Shibusawa T, Lukens E. Analyzing qualitative data in a cross-language context: a collaborative model. In: Padgett DK, editor. The qualitative research experience. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning; 2004. p. 175–86. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Miles AM, Huberman MM. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Goetz JP, LeCompte MD. Ethnography and qualitative design in educational research. Orlando, FL: Academic Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Freire P. Pedagogy of the oppressed. NY: Herder and Herder; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Freire P. Education for critical consciousness. NY: Seabury Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Eng E, Rhodes SD, Parker EA. Natural helper models to enhance a community’s health and competence. In: DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, Kegler MC, editors. Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2009. p. 303–30. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Viswanathan M, Kraschnewski JL, Nishikawa B, Gartlehner G, Lohr KN, Griffith D, et al. Outcomes and costs of community health worker interventions: a systematic review. Med Care 2010;48:792–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Rhodes SD, Daniel J, Alonzo J, Vissman AT, Duck S, Downs M, et al. A snapshot of how Latino heterosexual men promote sexual health within their social networks: process evaluation findings from an efficacious community-level intervention. AIDS Educ Prev 2012;24:514–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Stone LC, Steimel L, Vasquez-Guzman E, Kaufman A. The potential conflict between policy and ethics in caring for undocumented immigrants at academic health centers. Acad Med 2014;89:536–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]