Key Points

Question

What are the long-term risks of hypertension in women who deliver preterm?

Findings

In this cohort study of more than 2 million women in Sweden, after adjusting for preeclampsia, other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, and other maternal factors, women who delivered preterm had a greater than 1.6-fold risk of hypertension and women who delivered extremely preterm had a 2.2-fold risk within the next 10 years compared with those who delivered full term. These risks decreased but remained significantly elevated 40 years later and were not explained by shared familial factors.

Meaning

These results suggest that preterm delivery is a lifelong risk factor for hypertension in women.

Abstract

Importance

Preterm delivery has been associated with future cardiometabolic disorders in women. However, the long-term risks of chronic hypertension associated with preterm delivery and whether such risks are attributable to familial confounding are unclear. Such knowledge is needed to improve long-term risk assessment, clinical monitoring, and cardiovascular prevention strategies in women.

Objective

To examine the long-term risks of chronic hypertension associated with preterm delivery in a large population-based cohort of women.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This national cohort study assessed all 2 195 989 women in Sweden with a singleton delivery from January 1, 1973, to December 31, 2015. Data analyses were conducted from March 8, 2021, to August 20, 2021.

Exposures

Pregnancy duration identified from nationwide birth records.

Main Outcomes and Measures

New-onset chronic hypertension identified from primary care, specialty outpatient, and inpatient diagnoses using administrative data. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to compute hazard ratios (HRs) while adjusting for preeclampsia, other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, and other maternal factors. Cosibling analyses were assessed for potential confounding by shared familial (genetic and/or environmental) factors.

Results

In 46.1 million person-years of follow-up, 351 189 of 2 195 989 women (16.0%) were diagnosed with hypertension (mean [SD] age, 55.4 [9.9] years). Within 10 years after delivery, the adjusted HR for hypertension associated with preterm delivery (gestational age <37 weeks) was 1.67 (95% CI, 1.61-1.74) and when further stratified was 2.23 (95% CI, 1.98-2.52) for extremely preterm (22-27 weeks of gestation), 1.85 (95% CI, 1.74-1.97) for moderately preterm (28-33 weeks of gestation), 1.55 (95% CI, 1.48-1.63) for late preterm (34-36 weeks of gestation), and 1.26 (95% CI, 1.22-1.30) for early-term (37-38 weeks of gestation) compared with full-term (39-41 weeks of gestation) delivery. These risks decreased but remained significantly elevated at 10 to 19 years (preterm vs full-term delivery: adjusted HR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.36-1.44), 20 to 29 years (preterm vs full-term delivery: adjusted HR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.18-1.23), and 30 to 43 years (preterm vs full-term delivery: adjusted HR, 95% CI, 1.12; 1.10-1.14) after delivery. These findings were not explained by shared determinants of preterm delivery and hypertension within families.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this large national cohort study, preterm delivery was associated with significantly higher future risks of chronic hypertension. These associations remained elevated at least 40 years later and were largely independent of other maternal and shared familial factors. Preterm delivery should be recognized as a lifelong risk factor for hypertension in women.

This national cohort study of women in Sweden with a singleton delivery examines whether preterm delivery is associated with long-term increased risks of chronic hypertension and whether these risks are largely independent of shared familial factors.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death in women and men worldwide but remains understudied and underrecognized in women.1,2 The most common modifiable CVD risk factor is hypertension, which accounts for most cases of stroke, ischemic heart disease (IHD), and other forms of CVD.3,4 Nearly 1 in 2 women worldwide have hypertension according to the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association diagnostic criteria (mean blood pressure ≥130/80 mm Hg or antihypertensive medication use).1,5 Major risk factors for hypertension include advancing age, obesity, unhealthy diet, excessive alcohol use, and physical inactivity.1,6,7 Certain pregnancy complications, especially preeclampsia and other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, also have been linked with subsequent development of chronic hypertension.8,9,10 These complications also are commonly associated with preterm delivery.11 However, the independent contribution of preterm delivery to long-term risks of chronic hypertension is unclear. A better understanding of the long-term hypertension risks associated with preterm delivery is needed to improve risk stratification, clinical monitoring, and CVD prevention in women.

Preterm delivery is a major public health problem, affecting nearly 11% of all births or 15 million deliveries worldwide each year.12 Women who deliver preterm have been reported to have higher long-term risks of stroke13 and IHD.14 A few studies15,16,17 also have suggested that preterm delivery, even without preeclampsia or other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, is associated with modestly increased risks of developing chronic hypertension, with relative risks in the 1.1 to 1.5 range. However, prior evidence has been limited by self-reported pregnancy history and outcomes15 and the unavailability of data from primary care settings15,16,17 where most hypertension cases are diagnosed.18 Furthermore, it is unclear whether previously reported associations are attributable to confounding by familial (genetic and/or environmental) factors that are shared determinants of both preterm delivery and hypertension. To our knowledge, this has not been examined; thus, the relative contributions of shared familial factors vs direct effects of preterm delivery remain unknown.

To address these knowledge gaps, we conducted a national cohort study of more than 2 million women in Sweden. Our goals were to (1) examine the risks of chronic hypertension associated with preterm delivery in the largest population-based cohort to date, (2) examine changes in such risks later in life with up to 43 years of follow-up, and (3) assess for potential confounding by shared genetic or early-life environmental factors within families by performing cosibling analyses. We hypothesized that preterm delivery is associated with long-term increased risks of chronic hypertension and that these risks are largely independent of shared familial factors.

Methods

Study Population

This national cohort study used data from the Swedish Medical Birth Register, which contains prenatal and birth information for nearly all deliveries in Sweden since 1973.19 Using this register, we identified 4 331 668 singleton deliveries among 2 203 746 women from January 1, 1973, to December 31, 2015. Singleton deliveries were selected to improve internal comparability given the higher prevalence of preterm delivery and its different underlying causes in multiple-gestation pregnancies.20 Women with preexisting hypertension at the onset of their first pregnancy (5625 [0.3%]), a subset of those with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy,21 were excluded to enable assessment of new-onset chronic hypertension associated with preterm delivery. We also excluded 8812 deliveries that lacked information on pregnancy duration, resulting in exclusion of 2132 women (0.1%). A total of 2 195 989 women (99.6% of the original cohort) with 4 308 286 deliveries remained for inclusion in the study. Data analyses were conducted from March 8, 2021, to August 20, 2021. This study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Lund, Sweden. Participant consent was not required because this study used only pseudonymized, registry-based secondary data. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Pregnancy Duration Ascertainment

Pregnancy duration was identified from the Swedish Medical Birth Register based on maternal report of last menstrual period in the 1970s and ultrasonographic estimation starting in the 1980s and onward (>70% of the cohort). Pregnancy duration was examined alternatively as a continuous variable or categorical variable with 6 groups based on the number of completed weeks: extremely preterm (22-27 weeks of gestation), moderately preterm (28-33 weeks of gestation), late preterm (34-36 weeks of gestation), early-term (37-38 weeks of gestation), full-term (39-41 weeks of gestation, used as the reference group), and postterm (≥42 weeks of gestation) delivery.11,13,14,22,23 In addition, the first 3 groups were combined to provide summary estimates for preterm delivery (<37 weeks of gestation).

Hypertension Ascertainment

The study cohort was followed up for hypertension from first delivery through December 31, 2015 (follow-up time: median, 23.7 years; range, 0.2-43.0 years). The outcome was defined as any hypertension diagnosis that occurred more than 12 weeks post partum to distinguish chronic from gestational hypertension.21 Hypertension diagnoses were identified using International Classification of Diseases, Eighth Revision (ICD-8), International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9), and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) assigned at any health care encounter in inpatient, specialty outpatient, or primary care settings as recorded in the Swedish hospital, outpatient, and primary care registers and all deaths attributed to hypertension in the Swedish Death Register (see eTable 1 in the Supplement for ICD codes).23 The Swedish Hospital Discharge Register contains all primary and secondary hospital discharge diagnoses from 6 populous counties in southern Sweden starting in 1964 and with nationwide coverage starting in 1987; these diagnoses are currently more than 99% complete, and positive predictive values greater than 95% have been reported for hypertension and other major CVDs.24 The Swedish Outpatient Register contains all diagnoses from specialty clinics nationwide starting in 2001. The Swedish Primary Care Register initially included primary care diagnoses that covered 20% of the national population starting in 1998 and was expanded to cover approximately 45% of the national population in 2001 and more than 75% by 2008 and onward.25 The Swedish Death Register includes all deaths and causes of death for all persons registered in Sweden since 1960, with compulsory reporting nationwide.

Throughout the study period (January 1, 1973, to December 31, 2015), the predominant criteria for diagnosis of hypertension were mean systolic blood pressure of 140 mm Hg or higher and/or mean diastolic blood pressure of 90 mm Hg or higher or receiving antihypertensive drug therapy based on World Health Organization and European Society of Hypertension/European Society of Cardiology guidelines during this period.26,27 However, specific blood pressure measurements were unavailable for analysis; thus, hypertension was assessed based on ICD codes as described above.

Covariates

Other maternal characteristics that may be associated with pregnancy duration and hypertension risk were identified using the Swedish Medical Birth Register and national census data, which were linked using a pseudonymous version of the personal identification number. The following maternal variables were included in adjusted models, with all time-varying factors updated for each pregnancy and modeled as time-dependent covariates: age at delivery (continuous and categorical in 5-year groups), calendar year of delivery (continuous and categorical by decade), parity (1, 2, 3, 4, or ≥5), educational level (≤9, 10-12, or >12 years), employment status (yes/no), and income (quartiles) in the year before delivery; country or region of origin (Sweden; other European countries, US, and Canada; Asia and Oceania; Africa; Latin America; and other or unknown); prenatal smoking (0, 1-9, or ≥10 cigarettes/d) and body mass index (BMI [calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared]; continuous and categorical [<18.5, 18.5-24.9, 25.0-29.9, or ≥30.0]); and preeclampsia, other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, and diabetes (gestational or pregestational types 1 or 2) before delivery (see eTable 1 in the Supplement for ICD codes).

Maternal smoking and BMI were assessed at the beginning of prenatal care starting in 1982, and maternal smoking data were available for 74.7% and BMI data for 61.8% of all deliveries. Data were greater than 99% complete for all other variables. Missing data for each covariate were multiply imputed with 10 imputations using all other covariates and hypertension as independent variables.28 As alternatives to multiple imputation, sensitivity analyses were performed that were restricted to deliveries with complete data (2 600 924 deliveries among 1 559 495 women) or coded missing data for each covariate as a separate category.

Statistical Analysis

Cox proportional hazards regression was used to compute hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs for associations between pregnancy duration and subsequent risk of chronic hypertension. These associations were examined across the maximum possible follow-up (up to 43 years) and in narrower intervals of follow-up (<10, 10-19, 20-29, and 30-43 years) among women still living in Sweden without a prior diagnosis of hypertension at the beginning of the respective interval. Pregnancy duration was modeled as a time-dependent variable, with the exposure category determined by the shortest pregnancy to date. For example, if a woman’s first delivery was full term and her second was preterm, she entered the preterm exposure category at the date of her second delivery.13,14,22 In all models, elapsed time since delivery was used as the Cox proportional hazards regression model time axis. Models were performed both unadjusted and adjusted for covariates (as defined above). Women were censored at death from causes other than hypertension as identified in the Swedish Death Register (53 633 [2.4%]) or emigration as determined by absence of a Swedish residential address in census data (44 896 [2.0%]). Absolute risk differences and 95% CIs were computed for each pregnancy duration group compared with full term.29 The proportional hazards assumption was assessed by examining log-log plots,30 and no substantial departures were found.

Cosibling analyses were performed to assess for potential confounding by unmeasured shared familial (genetic and/or early-life environmental) factors.13,14,22,23 Shared environmental factors in families may include lifestyle factors, such as diet and physical activity, or ambient exposures, such as passive smoking. These analyses included all 1 190 226 women with at least 1 sister who had a singleton delivery. Stratified Cox proportional hazards regression was used with a separate stratum for each set of sisters as identified by their mother’s pseudonymous identification number. In the stratified Cox proportional hazards regression model, each set of sisters had its own baseline hazard function that reflected their shared genetic and environmental factors, thus controlling for their shared exposures. In addition, these analyses were further adjusted for the same covariates as in the main analyses.

Other secondary and sensitivity analyses are described in the eMethods in the Supplement. All statistical tests were 2-sided and used an α level of .05. All analyses were conducted using Stata software, version 15.1 (StataCorp LLC).

Results

In 46.1 million person-years of follow-up, 351 189 of 2 195 989 women (16.0%) were diagnosed with hypertension (mean [SD] age, 55.4 [9.9] years). Table 1 gives the maternal characteristics by women’s shortest pregnancy duration. Women who delivered preterm were more likely than other women to be younger than 20 years, have a low educational level, be unemployed, smoke, or have high prenatal BMI, preeclampsia, other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, or diabetes. A total of 71.2% of hypertension cases were diagnosed only in primary care settings and thus would have been missed if primary care records were unavailable. Mean (SD) ages were 27.6 (5.2) years at first delivery, 55.4 (9.9) years at hypertension diagnosis, and 50.6 (13.3) years at end of follow-up. Incidence rates by pregnancy duration and follow-up time are reported in Table 2.

Table 1. Characteristics of Study Participants by Shortest Pregnancy Duration, Sweden, 1973-2015.

| Characteristic | No. (%) of study participants | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extremely preterm (22-27 wk) (n = 9004) | Moderately preterm (28-33 wk) (n = 45 139) | Late preterm (34-36 wk) (n = 140 024) | Early term (37-38 wk) (n = 552 495) | Full term (39-41 wk) (n = 1 359 049) | Postterm (≥42 wk) (n = 90 278) | |

| Age at first delivery, y | ||||||

| <20 | 799 (8.9) | 4109 (9.1) | 11 385 (8.1) | 35 944 (6.5) | 64 249 (4.7) | 2816 (3.1) |

| 20-24 | 2559 (28.4) | 13 263 (29.4) | 42 344 (30.2) | 162 399 (29.4) | 364 716 (26.8) | 17 833 (19.8) |

| 25-29 | 2751 (30.5) | 14 497 (32.1) | 47 248 (33.7) | 194 809 (35.3) | 500 363 (36.8) | 31 317 (34.7) |

| 30-34 | 1851 (20.6) | 8972 (19.9) | 27 402 (19.6) | 113 120 (20.5) | 306 973 (22.6) | 25 043 (27.7) |

| 35-39 | 845 (9.4) | 3460 (7.7) | 9624 (6.9) | 38 002 (6.9) | 102 814 (7.6) | 11 162 (12.4) |

| ≥40 | 199 (2.2) | 838 (1.9) | 2021 (1.4) | 8221 (1.5) | 19 934 (1.5) | 2107 (2.3) |

| Year of delivery | ||||||

| 1973-1979 | 1439 (16.0) | 10 130 (22.4) | 31 089 (22.2) | 112 586 (20.4) | 338 885 (24.9) | 34 066 (37.7) |

| 1980-1989 | 1772 (19.7) | 10 729 (23.8) | 33 821 (24.2) | 126 888 (23.0) | 260 632 (19.2) | 12 070 (13.4) |

| 1990-1999 | 1982 (22.0) | 9965 (22.1) | 30 492 (21.8) | 122 180 (22.1) | 269 691 (19.8) | 12 410 (13.7) |

| 2000-2009 | 2197 (24.4) | 9206 (20.4) | 29 027 (20.7) | 126 559 (22.9) | 280 914 (20.7) | 13 161 (14.6) |

| 2010-2015 | 1614 (17.9) | 5109 (11.3) | 15 595 (11.1) | 64 282 (11.6) | 208 927 (15.4) | 18 571 (20.6) |

| Final parity | ||||||

| 1 | 1711 (19.0) | 8357 (18.5) | 23 652 (16.9) | 86 467 (15.6) | 327 195 (24.1) | 46 459 (51.5) |

| 2 | 3024 (33.6) | 17 853 (39.5) | 62 155 (44.4) | 262 831 (47.6) | 669 457 (49.3) | 29 847 (33.1) |

| 3 | 2720 (30.2) | 12 035 (26.7) | 36 371 (26.0) | 146 154 (26.4) | 277 939 (20.4) | 10 457 (11.6) |

| 4 | 963 (10.7) | 4340 (9.6) | 11 672 (8.3) | 39 560 (7.2) | 61 769 (4.5) | 2480 (2.7) |

| ≥5 | 586 (6.5) | 2554 (5.7) | 6174 (4.4) | 17 483 (3.2) | 22 689 (1.7) | 1035 (1.1) |

| Educational level, y | ||||||

| ≤9 | 1498 (16.6) | 7474 (16.6) | 21 396 (15.3) | 76 041 (13.8) | 182 576 (13.4) | 16 196 (17.9) |

| 10-12 | 4166 (46.3) | 21 405 (47.4) | 65 384 (46.7) | 248 101 (44.9) | 594 103 (43.7) | 39 110 (43.3) |

| >12 | 3340 (37.1) | 16 260 (36.0) | 53 244 (38.0) | 228 353 (41.3) | 582 370 (42.9) | 34 972 (38.7) |

| Employment | 7442 (82.7) | 38 000 (84.2) | 119 807 (85.6) | 475 224 (86.0) | 1 178 477 (86.7) | 76 155 (84.4) |

| Income quartile | ||||||

| First (highest) | 2452 (27.2) | 10 265 (22.7) | 31 129 (22.2) | 131 016 (23.7) | 349 673 (25.7) | 24 605 (27.2) |

| Second | 2236 (24.8) | 10 786 (23.9) | 33 912 (24.2) | 133 956 (24.3) | 347 219 (25.6) | 25 795 (28.6) |

| Third | 1862 (20.7) | 11 396 (25.3) | 35 406 (25.3) | 137 077 (24.8) | 336 295 (24.7) | 22 368 (24.8) |

| Fourth (lowest) | 2454 (27.3) | 12 692 (28.1) | 39 577 (28.3) | 150 446 (27.2) | 325 862 (24.0) | 17 510 (19.4) |

| Birth country or region | ||||||

| Sweden | 6873 (76.3) | 37 139 (82.4) | 116 082 (82.9) | 450 004 (81.4) | 1 119 539 (82.4) | 72 960 (80.8) |

| Other European country, US, or Canada | 954 (10.6) | 3966 (8.8) | 12 128 (8.7) | 48 948 (8.9) | 129 451 (9.5) | 10 477 (11.6) |

| Asia or Oceania | 734 (8.2) | 2656 (5.9) | 8362 (6.0) | 38 316 (6.9) | 74 152 (5.5) | 3728 (4.1) |

| Africa | 324 (3.6) | 883 (2.0) | 1925 (1.4) | 8202 (1.5) | 21 813 (1.6) | 2228 (2.5) |

| Latin America | 110 (1.2) | 397 (0.9) | 1389 (1.0) | 6482 (1.2) | 12 719 (0.9) | 764 (0.9) |

| Other or unknown | 9 (0.1) | 58 (0.1) | 138 (1.0) | 543 (0.1) | 1375 (0.1) | 121 (0.1) |

| Smoking, cigarettes/d | ||||||

| 0 | 6515 (72.4) | 30 942 (68.5) | 99 607 (71.1) | 410 632 (74.3) | 997 095 (73.4) | 58 459 (64.7) |

| 1-9 | 2051 (22.8) | 12 034 (26.7) | 34 566 (24.7) | 121 857 (22.1) | 323 255 (23.8) | 29 758 (33.0) |

| ≥10 | 438 (4.9) | 2163 (4.8) | 5851 (4.2) | 20 006 (3.6) | 38 699 (2.8) | 2061 (2.3) |

| BMI | ||||||

| <18.5 | 222 (2.5) | 1295 (2.9) | 4218 (3.0) | 16 276 (2.9) | 29 826 (2.2) | 1056 (1.2) |

| 18.5-24.9 | 6873 (76.3) | 36 550 (81.0) | 114 020 (81.4) | 451 205 (81.7) | 1 114 894 (82.0) | 72 708 (80.5) |

| 25.0-29.9 | 1323 (14.7) | 5084 (11.3) | 15 591 (11.1) | 62 543 (11.3) | 159 028 (11.7) | 11 337 (12.6) |

| ≥30.0 | 586 (6.5) | 2210 (4.9) | 6195 (4.4) | 22 471 (4.1) | 55 301 (4.1) | 5177 (5.7) |

| Preeclampsia | 975 (10.8) | 6820 (15.1) | 13 913 (9.9) | 35 408 (6.4) | 61 316 (4.5) | 4127 (4.6) |

| Other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy | 80 (0.9) | 580 (1.3) | 1580 (1.1) | 5751 (1.0) | 12 016 (0.9) | 733 (0.8) |

| Diabetes | 201 (2.2) | 1328 (2.9) | 4245 (3.0) | 9881 (1.8) | 11 113 (0.8) | 483 (0.5) |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared).

Table 2. Associations Between Women’s Pregnancy Duration and Subsequent Risk of Chronic Hypertension.

| Pregnancy duration and follow-up time | No. of cases | Ratea | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | Adjustedb | Risk difference (95% CI)c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | |||||

| 0-43 y After delivery | ||||||

| Preterm (<37 wk) | 36 455 | 962.7 | 1.42 (1.40 to 1.43) | 1.25 (1.23 to 1.26) | <.001 | 246.0 (235.7 to 256.3) |

| Extremely preterm (22-27 wk) | 1556 | 1073.3 | 1.68 (1.60 to 1.76) | 1.42 (1.35 to 1.49) | <.001 | 356.6 (303.2 to 410.1) |

| Moderately preterm (28-33 wk) | 9230 | 1058.0 | 1.55 (1.52 to 1.59) | 1.33 (1.30 to 1.36) | <.001 | 341.3 (319.5 to 363.1) |

| Late preterm (34-36 wk) | 25 669 | 926.9 | 1.36 (1.35 to 1.38) | 1.21 (1.19 to 1.23) | <.001 | 210.2 (198.4 to 221.9) |

| Early term (37-38 wk) | 87 337 | 814.1 | 1.19 (1.18 to 1.20) | 1.11 (1.10 to 1.12) | <.001 | 97.4 (91.1 to 103.6) |

| Full term (39-41 wk) | 209 269 | 716.7 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA | 0 [Reference] |

| Postterm (≥42 wk) | 18 128 | 748.4 | 0.94 (0.93 to 0.96) | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.03) | .13 | 31.7 (20.3 to 43.0) |

| Per additional wk (trend) | NA | NA | 0.95 (0.95 to 0.95) | 0.97 (0.97 to 0.97) | <.001 | NA |

| <10 y After delivery | ||||||

| Preterm (<37 wk) | 3606 | 257.4 | 2.66 (2.57 to 2.77) | 1.67 (1.61 to 1.74) | <.001 | 165.4 (156.9 to 174.0) |

| Extremely preterm (22-27 wk) | 266 | 470.1 | 4.59 (4.07 to 5.18) | 2.23 (1.98 to 2.52) | <.001 | 378.1 (321.6 to 434.6) |

| Moderately preterm (28-33 wk) | 1129 | 353.1 | 3.57 (3.36 to 3.79) | 1.85 (1.74 to 1.97) | <.001 | 261.1 (240.4 to 281.7) |

| Late preterm (34-36 wk) | 2211 | 215.8 | 2.26 (2.16 to 2.36) | 1.55 (1.48 to 1.63) | <.001 | 123.8 (114.7 to 133.0) |

| Early term (37-38 wk) | 5902 | 145.2 | 1.50 (1.45 to 1.55) | 1.26 (1.22 to 1.30) | <.001 | 53.2 (49.1 to 57.2) |

| Full term (39-41 wk) | 11 320 | 92.0 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA | 0 [Reference] |

| Postterm (≥42 wk) | 810 | 68.0 | 0.75 (0.70 to 0.81) | 0.86 (0.80 to 0.93) | <.001 | −24.0 (−29.0 to −19.0) |

| Per additional wk (trend) | NA | NA | 0.87 (0.87 to 0.88) | 0.93 (0.93 to 0.94) | <.001 | NA |

| 10-19 y After delivery | ||||||

| Preterm (<37 wk) | 6329 | 535.4 | 1.79 (1.73 to 1.83) | 1.40 (1.36 to 1.44) | <.001 | 217.4 (203.7 to 231.2) |

| Extremely preterm (22-27 wk) | 357 | 791.6 | 2.59 (2.34 to 2.88) | 1.78 (1.60 to 1.98) | <.001 | 474.6 (391.4 to 555.8) |

| Moderately preterm (28-33 wk) | 1601 | 584.8 | 1.92 (1.83 to 2.02) | 1.38 (1.32 to 1.46) | <.001 | 266.8 (237.9 to 295.7) |

| Late preterm (34-36 wk) | 4371 | 506.4 | 1.69 (1.64 to 1.74) | 1.38 (1.33 to 1.42) | <.001 | 188.4 (172.9 to 203.9) |

| Early term (37-38 wk) | 13 659 | 409.3 | 1.34 (1.32 to 1.37) | 1.19 (1.17 to 1.22) | <.001 | 91.3 (83.4 to 99.2) |

| Full term (39-41 wk) | 25 899 | 318.0 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA | 0 [Reference] |

| Postterm (≥42 wk) | 1711 | 316.1 | 0.85 (0.81 to 0.89) | 0.99 (0.95 to 1.05) | .84 | −1.9 (−17.4 to 13.5) |

| Per additional wk (trend) | NA | NA | 0.92 (0.91 to 0.92) | 0.95 (0.95 to 0.96) | <.001 | NA |

| 20-29 y After delivery | ||||||

| Preterm (<37 wk) | 12 682 | 1571.8 | 1.37 (1.35 to 1.40) | 1.20 (1.18 to 1.23) | <.001 | 337.8 (308.9 to 366.6) |

| Extremely preterm (22-27 wk) | 466 | 1590.5 | 1.41 (1.29 to 1.55) | 1.21 (1.10 to 1.32) | <.001 | 356.5 (211.8 to 501.2) |

| Moderately preterm (28-33 wk) | 3207 | 1713.9 | 1.50 (1.45 to 1.56) | 1.29 (1.24 to 1.34) | <.001 | 479.8 (419.8 to 539.9) |

| Late preterm (34-36 wk) | 9009 | 1525.9 | 1.33 (1.30 to 1.36) | 1.17 (1.15 to 1.20) | <.001 | 291.8 (259.0 to 324.6) |

| Early term (37-38 wk) | 32 063 | 1437.8 | 1.23 (1.21 to 1.24) | 1.12 (1.11 to 1.14) | <.001 | 203.7 (185.5 to 222.0) |

| Full term (39-41 wk) | 69 116 | 1234.0 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA | 0 [Reference] |

| Postterm (≥42 wk) | 5160 | 1254.0 | 0.90 (0.88 to 0.93) | 1.02 (0.99 to 1.05) | .16 | 20.0 (−15.5 to 55.4) |

| Per additional wk (trend) | NA | NA | 0.95 (0.95 to 0.95) | 0.97 (0.97 to 0.97) | <.001 | NA |

| 30-43 y After delivery | ||||||

| Preterm (<37 wk) | 13 538 | 3990.4 | 1.16 (1.14 to 1.18) | 1.12 (1.10 to 1.14) | <.001 | 284.8 (213.8 to 355.8) |

| Extremely preterm (22-27 wk) | 454 | 3886.1 | 1.14 (1.04 to 1.25) | 1.11 (1.01 to 1.22) | .02 | 180.5 (−177.7 to 538.7) |

| Moderately preterm (28-33 wk) | 3209 | 4096.7 | 1.20 (1.15 to 1.24) | 1.15 (1.11 to 1.19) | <.001 | 391.1 (247.6 to 534.7) |

| Late preterm (34-36 wk) | 9875 | 3961.8 | 1.14 (1.12 to 1.17) | 1.11 (1.09 to 1.13) | <.001 | 256.2 (174.9 to 337.6) |

| Early term (37-38 wk) | 35 060 | 3770.0 | 1.07 (1.05 to 1.08) | 1.06 (1.04 to 1.07) | <.001 | 64.4 (18.9 to 110.0) |

| Fullterm (39-41 wk) | 101 720 | 3705.6 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | NA | 0 [Reference] |

| Postterm (≥42 wk) | 10 351 | 4116.3 | 1.04 (1.02 to 1.06) | 1.02 (1.00 to 1.05) | .02 | 410.7 (328.2 to 493.2) |

| Per additional wk (trend) | NA | NA | 0.98 (0.98 to 0.99) | 0.99 (0.98 to 0.99) | <.001 | NA |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; NA, not applicable.

Incidence rate per 100 000 person-years.

Adjusted for maternal age, year of delivery, parity, educational level, employment, income, region of origin, body mass index, smoking, preeclampsia, other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, and diabetes.

Incidence rate difference per 100 000 person-years.

Pregnancy Duration and Risk of Hypertension

Across the entire follow-up period (0-43 years after first delivery), the adjusted HRs for hypertension associated with pregnancy duration were 1.42 (95% CI, 1.35-1.49) for extremely preterm delivery, 1.25 (95% CI, 1.23-1.26) for any preterm delivery, and 1.11 (95% CI, 1.10-1.12) for early-term delivery compared with full-term delivery (Table 2). Each additional week of pregnancy was associated with a mean 3% lower risk of hypertension (adjusted HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.97-0.97; P < .001).

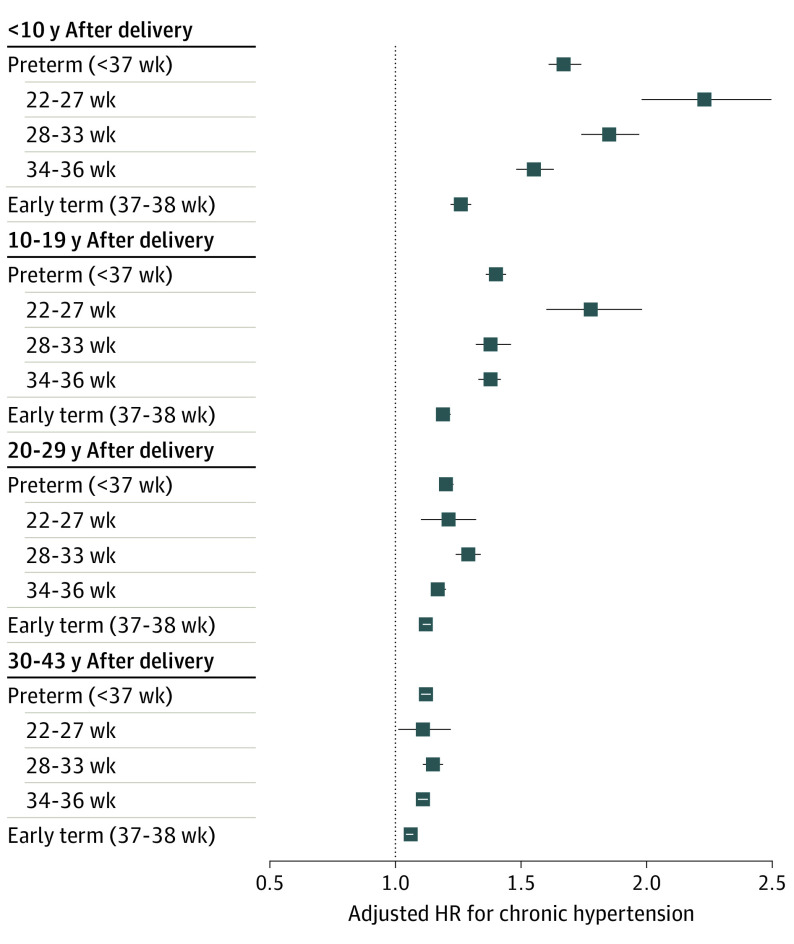

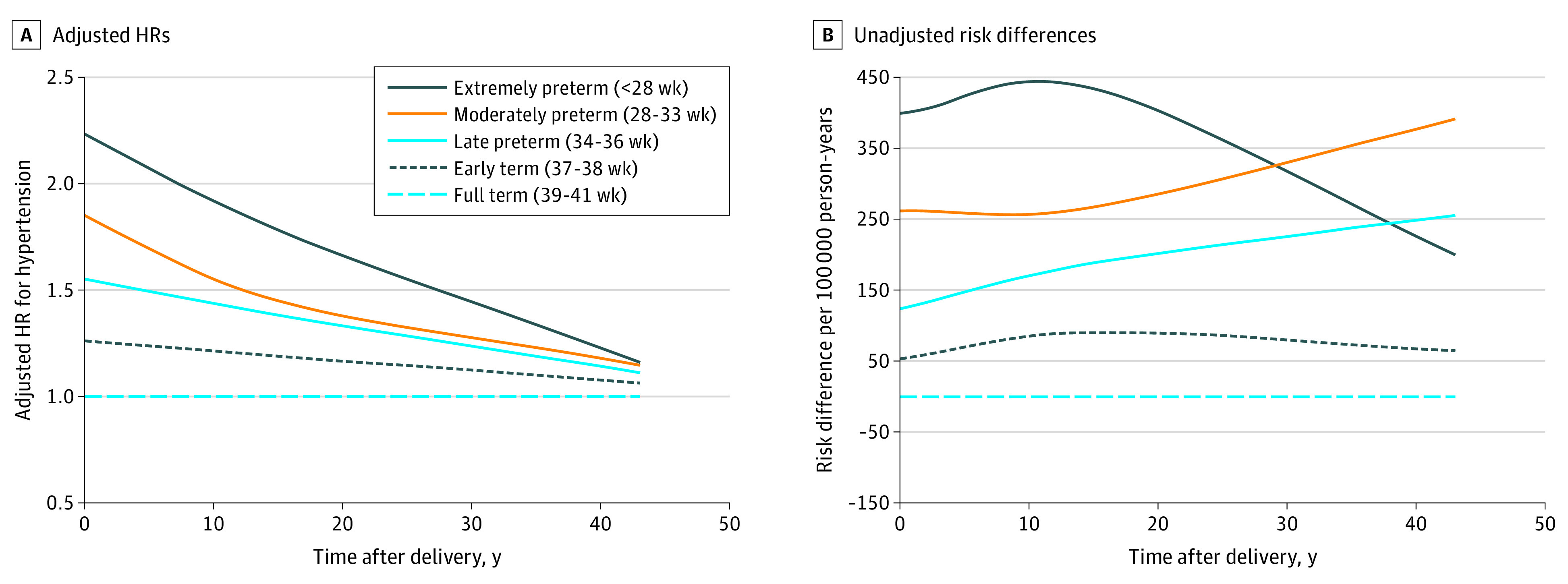

The HRs were highest within the first 10 years after delivery and then subsequently decreased, whereas risk differences (ie, excess hypertension cases) associated with preterm delivery increased with longer follow-up (Table 2 and Figure 1). Within the first 10 years after delivery, the adjusted HR for hypertension associated with preterm delivery was 1.67 (95% CI, 1.61-1.74) and when further stratified was 2.23 (95% CI, 1.98-2.52) for extremely preterm, 1.85 (95% CI, 1.74-1.97) for moderately preterm, 1.55 (95% CI, 1.48-1.63) for late preterm, and 1.26 (95% CI, 1.22-1.30) for early-term delivery compared with full-term delivery (Table 2). Each additional week of pregnancy was associated with a mean 7% lower risk (adjusted HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.93-0.94; P < .001).

Figure 1. Adjusted Hazard Ratios (HRs) and Unadjusted Risk Differences for Chronic Hypertension by Pregnancy Duration Compared With Full Term, Sweden, 1973-2015.

After longer follow-up, the risk of hypertension associated with preterm delivery decreased but remained significantly elevated at 10 to 19 years (adjusted HR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.36-1.44), 20 to 29 years (adjusted HR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.18-1.23), and 30 to 43 years (adjusted HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.10-1.14) after delivery. Early-term delivery (37-38 weeks of gestation) also was associated with slightly increased risks even more than 20 years later compared with full-term delivery (adjusted HR, 20-29 years: 1.12; 95% CI, 1.11-1.14; P < .001; 30-43 years: adjusted HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.04-1.07; P < .001). Figure 1 shows adjusted HRs and unadjusted risk differences for hypertension by time since delivery for different pregnancy durations using spline curves. Figure 2 shows adjusted HRs and 95% CIs for hypertension by pregnancy duration and time since delivery.

Figure 2. Adjusted Hazard Ratios (HRs) for Chronic Hypertension by Pregnancy Duration and Time Since Delivery, Sweden, 1973-2015.

Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

As an alternative to adjusting for preeclampsia or other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, exclusion of women with these disorders resulted in little change in risk estimates. For example, comparing preterm with full-term delivery, the adjusted HRs for chronic hypertension were 1.63 (95% CI, 1.54-1.72) at less than 10 years of follow-up, 1.42 (95% CI, 1.37-1.46) at 10 to 19 years of follow-up, 1.19 (95% CI, 1.17-1.22) at 20 to 29 years of follow-up, and 1.11 (95% CI, 1.09-1.13) at 30 to 43 years of follow-up (P < .001 for each).

Cosibling Analyses

Cosibling analyses to control for unmeasured shared familial factors resulted in partial attenuation of most but not all risk estimates (Table 3). For example, comparing preterm with full-term delivery, the adjusted HRs for hypertension were 1.67 (95% CI, 1.61-1.74) in the primary analysis vs 1.70 (95% CI, 1.39-2.07) in the cosibling analysis within 10 years after delivery, 1.40 (95% CI, 1.36-1.44) in the primary analysis vs 1.29 (95% CI, 1.15-1.45) in the cosibling analysis at 10 to 19 years after delivery, 1.20 (95% CI, 1.18-1.23) in the primary analysis vs 1.11 (95% CI, 1.04-1.19) in the cosibling analysis at 20 to 29 years after delivery, and 1.12 (95% CI, 1.10-1.14) in the primary analysis vs 1.07 (95% CI, 1.00-1.15) in the cosibling analysis at 30 to 43 years after delivery. Overall, these findings suggest that the associations observed in the main analyses were only partially attributable to shared genetic or early-life environmental factors in families.

Table 3. Cosibling Analyses of Women’s Pregnancy Duration and Subsequent Risk of Chronic Hypertension.

| Pregnancy duration and follow-up time | No. of cases | HR (95% CI)a | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0-43 y After delivery | |||

| Preterm (<37 wk) | 13 062 | 1.20 (1.16-1.24) | <.001 |

| Early term (37-38 wk) | 44 715 | 1.05 (1.03-1.08) | <.001 |

| Full term (39-41 wk) | 142 145 | 1 [Reference] | |

| Per additional wk (trend) | NA | 0.98 (0.97-0.98) | <.001 |

| <10 y After delivery | |||

| Preterm (<37 wk) | 2927 | 1.70 (1.39-2.07) | <.001 |

| Early term (37-38 wk) | 7586 | 1.21 (1.06-1.39) | .006 |

| Full term (39-41 wk) | 17 323 | 1 [Reference] | |

| Per additional wk (trend) | NA | 0.94 (0.91-0.96) | <.001 |

| 10-19 y After delivery | |||

| Preterm (<37 wk) | 3780 | 1.29 (1.15-1.45) | <.001 |

| Early term (37-38 wk) | 13 190 | 1.13 (1.04-1.22) | .003 |

| Full term (39-41 wk) | 39 750 | 1 [Reference] | |

| Per additional wk (trend) | NA | 0.97 (0.95-0.98) | <.001 |

| 20-29 y After delivery | |||

| Preterm (<37 wk) | 4653 | 1.11 (1.04-1.19) | .001 |

| Early term (37-38 wk) | 17 825 | 1.05 (1.00-1.10) | .04 |

| Full term (39-41 wk) | 58 863 | 1 [Reference] | |

| Per additional wk (trend) | NA | 0.98 (0.97-0.99) | <.001 |

| 30-43 y After delivery | |||

| Preterm (<37 wk) | 1702 | 1.07 (1.00-1.15) | .06 |

| Early term (37-38 wk) | 6114 | 1.00 (0.96-1.05) | .88 |

| Full term (39-41 wk) | 26 209 | 1 [Reference] | |

| Per additional wk (trend) | NA | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) | .22 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; NA, not applicable.

Adjusted for shared familial (genetic and/or environmental) factors and additionally for maternal age, year of delivery, parity, educational level, employment, income, body mass index, smoking, preeclampsia, other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, and diabetes.

Other Secondary Analyses

Associations between the number of preterm deliveries and risk of hypertension among women with at least 2 singleton deliveries are given in eTable 2 in the Supplement. Women with recurrent preterm delivery had further increases in risk. The adjusted HRs per each additional preterm delivery were 1.51 (95% CI, 1.47-1.56) at less than 10 years of follow-up, 1.28 (95% CI, 1.26-1.31) at 10 to 19 years of follow-up, 1.12 (95% CI, 1.10-1.14) at 20 to 29 years of follow-up, and 1.10 (95% CI, 1.08-1.11) at 30 to 43 years of follow-up (P < .001 for each).

Both spontaneous and medically indicated delivery at preterm or early term were associated with increased risks of chronic hypertension compared with full-term delivery (eg, spontaneous preterm: adjusted HR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.21-1.30; P < .001; medically indicated preterm: adjusted HR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.42-1.50; P < .001) (eTable 3 in the Supplement). However, medically indicated delivery was the stronger risk factor (P < .001 for difference in these HRs). Medically indicated preterm delivery that was specifically related to preeclampsia or other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy was associated with nearly a 1.7-fold subsequent risk (adjusted HR, 1.67; 95% CI, 1.62-1.73; P < .001), whereas preterm delivery for other indications (predominantly diabetes) was associated with a 1.4-fold risk (adjusted HR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.35-1.47; P < .001) of chronic hypertension.

Among women with 2 deliveries, the subsequent risk of hypertension did not vary significantly by whether the first vs second delivery occurred preterm. In addition, all results were negligibly changed in other analyses that further adjusted for oral contraceptive use, assessed alternatives to multiple imputation for missing data, ascertained hypertension based on 2 or more (rather than ≥1) diagnoses, or restricted to each woman's first delivery. These analyses are reported in the eResults in the Supplement.

Discussion

In this large national cohort study of women, shorter pregnancy duration was associated with significantly higher future risks of chronic hypertension, even after adjusting for preeclampsia, other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, and other potential confounders. Women who delivered preterm had greater than 1.6-fold and those who delivered extremely preterm had 2.2-fold risks of hypertension within the next 10 years compared with those who delivered full term. These risks subsequently decreased but remained slightly elevated (approximately 1.1-fold) even 30 to 43 years after delivery. Early-term delivery (37-38 weeks of gestation) also was associated with modestly increased risks of chronic hypertension. Cosibling analyses suggested that these findings were only partially explained by familial (genetic and/or early-life environmental) factors that are shared determinants of both preterm delivery and hypertension.

To our knowledge, this is the largest study to date of preterm delivery in relation to future risks of hypertension and the first to assess for potential confounding by shared familial factors using a cosibling design. Most of the risk estimates were consistent with or slightly higher than those from previous smaller studies.15,16,17 For example, a US study15 based on self-reported data in 57 904 women found that a first delivery that was preterm was associated with a 1.4-fold risk of hypertension within the next 10 years (HR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.20-1.70) and a 1.1-fold risk after a median follow-up of 28 years (HR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.06-1.17). A Danish cohort study16 based on hospital and death data for 427 775 women (average follow-up, 28 years) reported a nearly 1.3-fold risk of hypertension associated with preterm delivery (adjusted HR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.21-1.34). In an overlapping Danish cohort of 782 287 women (median follow-up, 14.6 years), the adjusted HRs for hypertension were 1.49 (95% CI, 1.09-2.04) for those who delivered at less than 28 weeks of gestation, 1.50 (95% CI, 1.25-1.80) for those who delivered at 28 to 31 weeks of gestation, and 1.30 (95% CI, 1.20-1.40) for those who delivered at 32 to 36 weeks of gestation.17 However, each of those studies lacked data from primary care settings; thus, hypertension likely was substantially underreported. A prospective US cohort study31 of 4484 women reported that preterm delivery was associated with a 2.2-fold risk of hypertension (95% CI, 1.6-3.1) after a mean follow-up of 3.2 years. Smaller clinical studies32,33,34,35 also reported that preterm delivery was associated with slightly higher systolic blood pressure (2-5 mm Hg higher mean levels) and diastolic blood pressure (1-4 mm Hg higher mean levels) after follow-up that ranged from 3 to 20 years.

The current study extends prior evidence by incorporating primary care, specialty outpatient, and inpatient data for a large national cohort with up to 43 years of follow-up and more than 12-fold as many hypertension cases as prior studies.15,16,17 In this cohort, more than 70% of hypertension cases would have been missed without primary care records. The findings indicated that hypertension risks after preterm delivery were highest within the next 10 years yet remained significantly elevated for at least 40 years. The relative risks decreased with longer follow-up, likely because of the increasing incidence of hypertension at older ages that is unrelated to preterm delivery. However, the excess hypertension cases (ie, risk differences) associated with preterm delivery, and thus the public health impacts, increased with longer follow-up to ages when hypertension is more likely to manifest. Women who delivered at early term (37-38 weeks of gestation) also had persistent, slightly increased risks compared with those who delivered at full term. Hypertension risks were significantly increased even after spontaneous preterm delivery and in women without preeclampsia or other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Women with recurrent preterm delivery had further increases in risk.

A previously unanswered key question was whether associations between preterm delivery and CVD are related to preexisting shared determinants of these outcomes or whether preterm delivery itself contributes to or modulates the pathophysiologic mechanisms that lead to CVD.17,36 Our findings for hypertension, as well as previous findings for stroke,13 IHD,14 and CVD mortality,22 suggest that the latter pathway is likely relevant. We found that associations between preterm delivery and hypertension were only partially attenuated after adjusting for unmeasured shared familial (genetic and/or early-life environmental) factors in cosibling analyses. Preeclampsia and other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy also are common causes of preterm delivery11 and linked with higher subsequent risks of hypertension8,9,10 and CVD mortality.10,37 However, even adjusting for or excluding these conditions, women with preterm delivery still had persistently elevated long-term risks of hypertension. Recent evidence suggests that preterm delivery may be a key event that triggers endothelial-specific inflammation that is undetectable before pregnancy.38 The resulting endothelial dysfunction is associated with functional changes in the microvasculature, including impaired ability to release endothelium-derived relaxing factors, leading to increased constrictive tone.39 These functional changes may contribute to subsequent development of hypertension and CVD.40,41,42 Further delineation of these mechanisms may eventually reveal new targets for intervention to prevent both preterm delivery and development of hypertension and CVD.

The current findings are consistent with previously reported associations between preterm delivery and long-term risks of stroke,13 IHD,14 and all-cause and CVD mortality.22,43 These findings have important clinical implications. Preterm delivery should now be recognized by clinicians and patients as a lifelong major risk factor for hypertension and CVD. Cardiovascular risk assessment in women should routinely include reproductive history that covers preterm delivery and other adverse pregnancy outcomes. This history should be a required element of electronic health records and linked with primary care to facilitate access by clinicians across patients’ life course.44 A history of preterm delivery may help identify women at high risk of hypertension and CVD potentially long before the onset of these conditions. Such women need early preventive actions to reduce other modifiable risk factors, including obesity, unhealthy diet, excessive alcohol use, smoking, and physical inactivity.1,6,7 These interventions should be implemented soon after preterm delivery, followed by long-term clinical monitoring for hypertension and other CVD risk factors. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring may be needed for better detection of hypertension in high-risk women.45,46 Our findings also underscore the importance of public health strategies to help prevent preterm delivery, including better access to high-quality preconception and prenatal care,47 especially in the US and other populations with a high prevalence of preterm birth.12

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths. A major strength is its large national cohort design, with up to 43 years of follow-up. The use of highly complete nationwide prenatal and birth records helped minimize potential selection biases. The availability of primary care, specialty outpatient, and inpatient diagnoses enabled, for the first time, highly complete ascertainment of hypertension that included primary care settings, where most cases are diagnosed.18 The large size of this cohort afforded high statistical power to assess narrowly defined pregnancy durations and key subgroups. Many maternal factors that are potential confounders were controlled for, as were unmeasured shared familial factors using cosibling analyses.

The study also has limitations, including the lack of detailed clinical records needed to verify hypertension diagnoses. High positive predictive values have been reported using Swedish registry data.24 However, to our knowledge, these values and the sensitivity and specificity have not been estimated specifically using outpatient records. In the current study, their sensitivity is likely greatly enhanced by the inclusion of primary care data to enable more complete capture of cases.48 Maternal report of last menstrual period (used mainly in the 1970s) may overestimate gestational age by approximately 2 days,49 causing a slight conservative bias to risk estimates. From the 1980s onward, gestational age was determined by ultrasonography, reducing potential misclassification. The 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association diagnostic criteria for hypertension5 have lower blood pressure cutoffs than those used in the current study period, which would result in a higher prevalence of hypertension than reported in this study. Lifestyle factors later in life may be important risk modifiers after preterm delivery and should be examined in future studies with access to this information. The current study also was limited to one country and will need replication in other populations when feasible. A priority for future research is to extend these findings to racial and ethnic subgroups that are at highest risk of preterm delivery and hypertension. Additional follow-up will be needed to examine these associations in older adulthood when hypertension increasingly and disproportionately affects women.5,50

Conclusions

In this national cohort of more than 2 million women, preterm delivery was associated with higher future risks of chronic hypertension even after adjusting for preeclampsia, other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, other maternal factors, and unmeasured shared familial factors. These risks were highest within the first 10 years but remained significantly elevated at least 40 years later. Preterm delivery should now be recognized as a risk factor for hypertension across the life course. Women with a history of preterm delivery need early preventive evaluation and long-term risk reduction and monitoring for hypertension.

eMethods. Supplemental Methods

eResults. Supplemental Results

eReferences

eTable 1. International Classification of Diseases (ICD) Codes Used in the Analyses.

eTable 2. Associations Between Number of Preterm Deliveries and Subsequent Risk of Chronic Hypertension Among Women With at Least Two Singleton Deliveries

eTable 3. Spontaneous or Medically Indicated Delivery and Subsequent Risk of Chronic Hypertension, Sweden, 1990-2015

References

- 1.Virani SS, Alonso A, Aparicio HJ, et al. ; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart disease and stroke statistics-2021 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143(8):e254-e743. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehta LS, Beckie TM, DeVon HA, et al. ; American Heart Association Cardiovascular Disease in Women and Special Populations Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, and Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Acute myocardial infarction in women: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133(9):916-947. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators . Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1659-1724. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31679-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forouzanfar MH, Liu P, Roth GA, et al. Global burden of hypertension and systolic blood pressure of at least 110 to 115 mm Hg, 1990-2015. JAMA. 2017;317(2):165-182. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.19043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2018;138(17):e426-e483. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forman JP, Stampfer MJ, Curhan GC. Diet and lifestyle risk factors associated with incident hypertension in women. JAMA. 2009;302(4):401-411. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Staessen JA, Wang J, Bianchi G, Birkenhäger WH. Essential hypertension. Lancet. 2003;361(9369):1629-1641. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13302-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Williams DJ. Pre-eclampsia and risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer in later life: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007;335(7627):974. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39335.385301.BE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Behrens I, Basit S, Melbye M, et al. Risk of post-pregnancy hypertension in women with a history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: nationwide cohort study. BMJ. 2017;358:j3078. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson BJ, Watson MS, Prescott GJ, et al. Hypertensive diseases of pregnancy and risk of hypertension and stroke in later life: results from cohort study. BMJ. 2003;326(7394):845. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7394.845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371(9606):75-84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chawanpaiboon S, Vogel JP, Moller AB, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of levels of preterm birth in 2014: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(1):e37-e46. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30451-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crump C, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Preterm delivery and long-term risk of stroke in women: a national cohort and cosibling study. Circulation. 2021;143(21):2032-2044. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.052268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crump C, Sundquist J, Howell EA, McLaughlin MA, Stroustrup A, Sundquist K. Pre-term delivery and risk of ischemic heart disease in women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(1):57-67. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanz LJ, Stuart JJ, Williams PL, et al. Preterm delivery and maternal cardiovascular disease risk factors: the Nurses’ Health Study II. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2019;28(5):677-685. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2018.7150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Catov JM, Wu CS, Olsen J, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Li J, Nohr EA. Early or recurrent preterm birth and maternal cardiovascular disease risk. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20(8):604-609. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lykke JA, Paidas MJ, Damm P, Triche EW, Kuczynski E, Langhoff-Roos J. Preterm delivery and risk of subsequent cardiovascular morbidity and type-II diabetes in the mother. BJOG. 2010;117(3):274-281. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02448.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tschanz CMP, Cushman WC, Harrell CTE, Berlowitz DR, Sall JL. Synopsis of the 2020 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs/U.S. Department of Defense clinical practice guideline: the diagnosis and management of hypertension in the primary care setting. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(11):904-913. doi: 10.7326/M20-3798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Statistics Sweden. The Swedish Medical Birth Register. Accessed March 9, 2021. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/en/statistics-and-data/registers/register-information/the-swedish-medical-birth-register/

- 20.Stock S, Norman J. Preterm and term labour in multiple pregnancies. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;15(6):336-341. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2010.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmad A, Oparil S. Hypertension in women: recent advances and lingering questions. Hypertension. 2017;70(1):19-26. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.08317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crump C, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Preterm delivery and long term mortality in women: national cohort and co-sibling study. BMJ. 2020;370:m2533. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crump C, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Risk of hypertension into adulthood in persons born prematurely: a national cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(16):1542-1550. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:450. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sundquist J, Ohlsson H, Sundquist K, Kendler KS. Common adult psychiatric disorders in Swedish primary care where most mental health patients are treated. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):235. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1381-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guidelines Subcommittee of the WHO/ISH Mild Hypertension Liaison Committee . 1993 Guidelines for the management of mild hypertension: memorandum from a World Health Organization/International Society of Hypertension meeting. Hypertension. 1993;22(3):392-403. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.22.3.392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, et al. ; Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension; European Society of Cardiology . 2007 Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens. 2007;25(6):1105-1187. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3281fc975a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rubin DB, ed. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Wiley; 1987. doi: 10.1002/9780470316696 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fleiss JL, Levin B, Paik MC. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. 3rd ed.. Wiley; 2003. doi: 10.1002/0471445428 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grambsch PM. Goodness-of-fit and diagnostics for proportional hazards regression models. Cancer Treat Res. 1995;75:95-112. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2009-2_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haas DM, Parker CB, Marsh DJ, et al. ; NHLBI nuMoM2b Heart Health Study . Association of adverse pregnancy outcomes with hypertension 2 to 7 years postpartum. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(19):e013092. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.013092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Catov JM, Dodge R, Barinas-Mitchell E, et al. Prior preterm birth and maternal subclinical cardiovascular disease 4 to 12 years after pregnancy. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2013;22(10):835-843. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2013.4248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Catov JM, Lewis CE, Lee M, Wellons MF, Gunderson EP. Preterm birth and future maternal blood pressure, inflammation, and intimal-medial thickness: the CARDIA study. Hypertension. 2013;61(3):641-646. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fraser A, Nelson SM, Macdonald-Wallis C, et al. Associations of pregnancy complications with calculated cardiovascular disease risk and cardiovascular risk factors in middle age: the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Circulation. 2012;125(11):1367-1380. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.044784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perng W, Stuart J, Rifas-Shiman SL, Rich-Edwards JW, Stuebe A, Oken E. Preterm birth and long-term maternal cardiovascular health. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(1):40-45. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rich-Edwards JW, Fraser A, Lawlor DA, Catov JM. Pregnancy characteristics and women’s future cardiovascular health: an underused opportunity to improve women’s health? Epidemiol Rev. 2014;36:57-70. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxt006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Theilen LH, Fraser A, Hollingshaus MS, et al. All-cause and cause-specific mortality after hypertensive disease of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(2):238-244. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lane-Cordova AD, Gunderson EP, Carnethon MR, et al. Pre-pregnancy endothelial dysfunction and birth outcomes: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Hypertens Res. 2018;41(4):282-289. doi: 10.1038/s41440-018-0017-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Konukoglu D, Uzun H. Endothelial dysfunction and hypertension. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;956:511-540. doi: 10.1007/5584_2016_90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blake GJ, Ridker PM. Novel clinical markers of vascular wall inflammation. Circ Res. 2001;89(9):763-771. doi: 10.1161/hh2101.099270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Libby P. Inflammation and cardiovascular disease mechanisms. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(2):456S-460S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.2.456S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Libby P, Ridker PM, Hansson GK; Leducq Transatlantic Network on Atherothrombosis . Inflammation in atherosclerosis: from pathophysiology to practice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(23):2129-2138. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu P, Gulati M, Kwok CS, et al. Preterm delivery and future risk of maternal cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(2):e007809. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quesada O, Shufelt C, Bairey Merz CN. Can we improve cardiovascular disease for women using data under our noses? a need for changes in policy and focus. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(12):1398-1400. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.4117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benschop L, Duvekot JJ, Versmissen J, van Broekhoven V, Steegers EAP, Roeters van Lennep JE. Blood pressure profile 1 year after severe preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2018;71(3):491-498. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.10338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salazar MR, Espeche WG, Balbín E, et al. Office blood pressure values and the necessity of out-of-office measurements in high-risk pregnancies. J Hypertens. 2019;37(9):1838-1844. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000002140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Barfield WD, Henderson Z, et al. CDC Grand Rounds: public health strategies to prevent preterm birth. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(32):826-830. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6532a4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wiréhn AB, Karlsson HM, Carstensen JM. Estimating disease prevalence using a population-based administrative healthcare database. Scand J Public Health. 2007;35(4):424-431. doi: 10.1080/14034940701195230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Høgberg U, Larsson N. Early dating by ultrasound and perinatal outcome. a cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1997;76(10):907-912. doi: 10.3109/00016349709034900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brahmbhatt Y, Gupta M, Hamrahian S. Hypertension in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2019;21(10):74. doi: 10.1007/s11906-019-0979-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Supplemental Methods

eResults. Supplemental Results

eReferences

eTable 1. International Classification of Diseases (ICD) Codes Used in the Analyses.

eTable 2. Associations Between Number of Preterm Deliveries and Subsequent Risk of Chronic Hypertension Among Women With at Least Two Singleton Deliveries

eTable 3. Spontaneous or Medically Indicated Delivery and Subsequent Risk of Chronic Hypertension, Sweden, 1990-2015