Abstract

Introduction

Suboptimal control of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) can result in increased rates of adverse pregnancy-related outcomes. We aimed to describe the current landscape of provision of antenatal care for women with IBD in the UK.

Methods

This cross-sectional survey collected data on service setup; principles of care pre-conception, during pregnancy and post partum; and on perceived roles and responsibilities of relevant clinicians.

Results

Data were provided for 97 IBD units. Prepregnancy counselling was offered mostly on request only (54%) and in an ad hoc manner. In 86% of units, IBD antenatal care was provided by the patient’s usual gastroenterologist, rather than a gastroenterologist with expertise in pregnancy (14%). Combined clinics with obstetricians and gastroenterologists were offered in 14% of units (24% academic vs 7% district hospitals; p=0.043). Communication with obstetrics was ‘as and when required’ in 51% and 30% of IBD units reviewed pregnant women with IBD ‘only when required’. The majority of respondents thought gastroenterologists should be involved in decisions regarding routine vaccinations (70%), breast feeding (80%), folic acid dosage (61%) and venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis (53%). Sixty-five per cent of respondents thought that gastroenterologists should be involved in decisions around mode of delivery and 30% recommended caesarean sections for previous but healed perianal disease.

Conclusions

This nationwide survey found considerable variation in IBD antenatal services. We identified deficiencies in service setup, care provided by IBD units and clinician knowledge. A basic framework to inform service setup, and better education on the available clinical guidance, is required to ensure consistent high-quality multidisciplinary care.

Keywords: ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Women with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) have a higher risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes.

IBD disease activity is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes.

British Society of Gastroenterology and British Maternal & Fetal Medicine Society have recently published guidance on service setup and minimum standards for care for pregnant women with IBD.

What are the new findings?

Robust systems to manage IBD during pregnancy are lacking in many UK IBD units.

Communication with obstetric teams is irregular and likely insufficient.

IBD units are often not getting involved in decision making for pregnant women with IBD.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

IBD units should devise systems that ensure regular review during pregnancy by suitable experienced clinicians.

IBD units should ensure regular communication with obstetric services and involvement in key decisions.

Dedicated IBD antenatal clinics should be considered where demand is high.

Background

The peak incidence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is between the second and fourth decades of life, which coincides with prime reproductive years and emphasises the importance of reproductive planning by healthcare providers.1–3

Fertility rates in women with IBD are generally similar to the normal population, with the exception of women experiencing moderate to severely active IBD and those who have had deep pelvic surgery.4–7 In addition, rates of voluntary childlessness are higher in women with IBD than in the general population and associated with poor knowledge of pregnancy-related issues in IBD.8 9

Women with IBD are at higher risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes including preterm birth, low gestation weight, congenital abnormalities, fetal loss and increased rates of caesarean section.10 The risks of negative pregnancy outcomes are much lower when the disease is optimally managed.10 Achieving remission prior to conception and maintenance of remission throughout pregnancy are crucial.5 Complex decisions must be made to optimise the mother’s health and achieve the best chances of a successful pregnancy. The importance of prepregnancy counselling in the general population is underlined by studies demonstrating that intended pregnancies were associated with less maternal smoking, better maternal and fetal outcomes, better mother–child relationships, better self-esteem of children and higher breastfeeding rates.11–15

International guidelines from the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation and American Gastroenterology Association provide an evidence-based consensus on IBD medication during pregnancy, delivery method and breast feeding.5 16 Although these guidelines provide advice on care for individual patients, little is known regarding how often units implement the guidance and how local services are organised. IBD-specific antenatal clinics can facilitate optimal care, alongside proactive prepregnancy counselling, which is associated with better maternal and fetal outcomes.2 17 Until now there has been limited research and guidance available in the UK on service setup. A recent endorsed guidance statement from the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and endorsed by the British Maternal & Fetal Medicine Society (BMFMS) has defined minimum standards of care for women with IBD in the UK (box 1).18 In addition, the endorsed guidance statement makes recommendations for service setup and provision. This study aimed to conduct a nationwide survey to understand how antenatal care is currently provided to women with IBD.

Box 1. Key recommendations for optimal IBD antenatal care.

-

Prepregnancy counselling is routinely offered covering:

contraception (where desired).

optimisation of maternal IBD prior to pregnancy.

advice on medical treatment and the importance of adherence during pregnancy.20–22

general health advice for pregnancy (smoking, alcohol and folic acid).

how to contact IBD and antenatal service once pregnancy is confirmed.

a plan for care during pregnancy.

Pregnant women with IBD should all be reviewed at least once in a consultant-led obstetric clinic.

IBD services should arrange a review in every trimester (can be telephone or video).

-

IBD unit should provide input on:

Folic acid supplementation.

IBD implications on the mode of delivery.

IBD medications during pregnancy and breast feeding.

Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis.

Communication between IBD units and obstetric teams needs to be regular to ensure optimal joint up care.

Where suitable joint IBD antenatal clinics can provide optimal care.

IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey design was chosen to provide an overview of the current provision across the UK. From the BSG membership database, a list of all UK gastroenterology units within the UK was compiled. We identified one clinician (consultant gastroenterologist or IBD specialist nurse) for each unit and sent up to three personal email invites to the online survey. The survey was developed by the authors consisting of a group of gastroenterologists, medical students, IBD specialist nurses, an obstetrician and an obstetric physician to cover service set up and perceived responsibilities of care.

Data were collected on IBD unit setup, obstetric services, estimated number of IBD pregnancies per year, frequency of routine IBD review during pregnancy, nominated clinicians caring for patients with IBD during pregnancy, availability of a combined IBD antenatal clinic, frequency and form of communication with obstetrics and availability of prepregnancy counselling. Furthermore, respondents were asked which clinician(s) were responsible for offering advice on the safety of IBD medication during pregnancy, folic acid dosing, thromboembolism prophylaxis, delivery methods, childhood vaccinations and breast feeding.

Data were collected and distributed via an online survey instrument provided by the University of Leeds. In line with the University of Leeds Research Ethics Policy ethical approval was not required.

Results

Data were provided by 71 survey responses representing 97 of 273 gastroenterology units within the UK. A single survey response could be completed for multiple units if they came under the umbrella care of a single gastroenterology unit. Sixty-nine per cent of survey responses were by consultant gastroenterologists, 28% by IBD specialist nurses and 2% of responses from a clinical fellow and a consultant nurse.

Service setup

Specialist IBD clinics were provided by 69% of units, whereas 31% provided IBD care through gastroenterology clinics only. Seventy-nine per cent of units had a consultant-led obstetric service available within the same National Health Service (NHS) Trust. In addition, 10% did not have a consultant-led obstetric service directly available but could access a dedicated obstetric service through a neighbouring NHS Trust. Eleven per cent of gastroenterology units reported that they had no access to a consultant-led obstetric service.

In 92% of units, a nominated consultant was available to oversee pregnancy-related care for IBD. In 86% of these units, the nominated consultant would be the patient’s usual IBD consultant, whereas in only 14% would this be a consultant with expertise in IBD pregnancy care. In addition, 61% of units nominated an IBD specialist nurse to oversee the patient’s pregnancy. During pregnancy, 55% of gastroenterology units reviewed their patients once during each trimester, 15% reviewed their patients on a monthly basis and 30% reviewed patients only as and when needed.

Combined clinics (obstetricians and gastroenterologists present within the same consultation) were offered by 14% of units. Teaching hospitals were significantly more likely to have a combined clinic than district general hospitals (24% vs 7%, p=0.043). All combined clinics offered antenatal care with 60% also offering pre-conception appointments and 20% offering postnatal reviews.

There was considerable variation in the annual number of pregnant patients with IBD seen in different units. Ten per cent of units saw up to 5 patients per year, 28% between 5 and 10 patients and another 28% between 10 and 20 pregnant patients. Fourteen per cent of units saw between 20 and 50 patients and 20% did not know the number of patients seen.

Prepregnancy counselling

Prepregnancy counselling was reported to be routinely offered to patients with IBD by 39% of respondents, 54% stated that counselling was available on request and 7% of respondents stated that prepregnancy counselling was not available. Of units offering prepregnancy counselling, 9% of units delivered this counselling via a specialist setup, whereas 91% delivered this in an ad hoc manner only.

Multidisciplinary communication

For units without a combined clinic, data were collected on how and when gastroenterologists and obstetricians communicated. Forty-nine per cent of gastroenterology units communicated with obstetrics after every clinic encounter, but 51% would only communicate as and when they felt this was required. When communicating with the obstetrics team, 100% of the respondents reported communication via letters, whereas 64% also used emails, 28% used hospital patient notes (but no obstetric patient records), 44% also communicated with each other over the telephone and 10% used meetings to communicate (multiple responses allowed).

Responsibilities of specialities

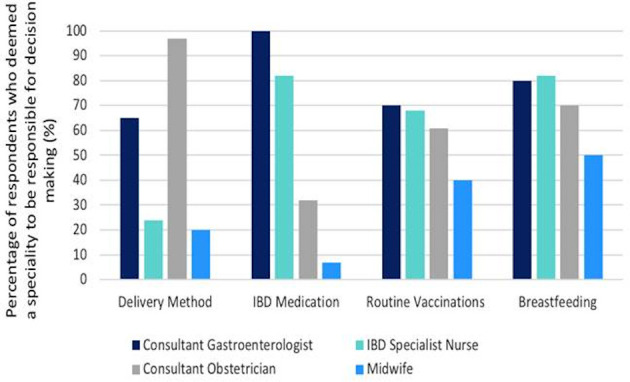

Participants were asked to state which specialties, in their opinion, should provide input/make recommendations for pregnancy care-related issues (multiple responses allowed, figure 1). The analysis focused on the perceived responsibilities of gastroenterologists to provide recommendations. Ninety-seven per cent of participants thought consultant obstetricians should offer advice on the method of delivery, but only 65% felt that consultant gastroenterologists should provide recommendations. Regarding IBD medication, 100% of participants stated that gastroenterologists were responsible for decision making, with 82% also selecting IBD nurses. Seventy per cent of participants believed gastroenterologists were responsible for offering advice on routine vaccinations for the newborn, 68% also selecting IBD specialist nurses, 61% selecting obstetricians and 39% selecting midwives. For decisions around breast feeding, 80% thought gastroenterologists were responsible, 82% selected IBD specialist nurses, 70% obstetricians and 51% midwives.

Figure 1.

The decision-making responsibilities of different specialties. A bar chart indicating which specialities respondents thought were responsible for decision making/offering advice on delivery method, IBD medication, routine vaccinations for the infant and breast feeding. IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

For folic acid recommendations and dosage, 61% felt this should be a joint decision between gastroenterology and obstetrics, 39% thought that obstetricians should be solely responsible. Regarding thromboprophylaxis, 52% thought this should be a joint decision between obstetrics and gastroenterologists, 47% thought that obstetricians were solely responsible and 1% thought this decision should be made by supervising gastroenterologists.

Fetal growth scans

We obtained information on the current practice of fetal growth scans for women with IBD in the absence of current national consensus. 65% of respondents thought that women with IBD should be routinely offered additional growth scans even if there are no other indications. In addition, or as an alternative to these routine scans, 94% of respondents thought that poorly controlled IBD was an indication for additional growth scans. Other indications for additional scans included immunomodulator therapy (15%), biological therapy (24%) and other obstetric indications (78%).

Delivery methods: current practice and knowledge of gastroenterologists

Overall, 65% of participants thought that gastroenterologists should be involved in decision making regarding the mode of delivery. However, 35% did not see a role for gastroenterologists in the decision-making process on the delivery method. Ninety-four per cent of participants thought active perianal disease was an indication for an elective caesarean section, but 30% also felt that previous but healed perianal disease (30%) was an indication. Ileoanal pouch surgery (56%) and previous abdominal and/or pelvic surgery (20%) were seen as other indications for caesarean section. In addition, 25% also thought that maternal request should be an indication for an elective caesarean section.

Discussion

Care for pregnant women with IBD requires complex decision making and multidisciplinary input to avoid adverse outcomes related to poorly controlled IBD.2 16 This study is the first to ascertain how UK-based IBD services are set up to provide antenatal care. We have detected considerable variation in service setup and care provision, thus highlighting areas requiring urgent improvement.

The reported number of pregnant patients seen with IBD was ≤10 patients for 37% of the units surveyed. Using the authors’ local databases where all IBD pregnancies are captured we estimate that secondary care IBD services covering a population of 350 000 may serve approximately 15–20 pregnant women annually in their geographical area. Our survey, therefore, suggests that many units underestimate the number of pregnant women with IBD. Women with IBD are at risk of not receiving IBD advice during their pregnancy. We feel that measures such as case reporting via community midwives would be invaluable to ensure that pregnant patients with IBD are identified and subsequently receive the specialist care required.

We found that the provision of prepregnancy counselling, which is associated with better maternal and fetal outcomes,2 was inconsistent. With only 54% of units providing prepregnancy counselling and in an ad hoc manner, many women will not receive adequate counselling. Ideally, prepregnancy counselling should be delivered in joint consultation with obstetric services, but we recognise that the current UK maternity funding model does not allow for universal adoption of such collaboration. IBD services need to develop robust approaches for providing easily accessible prepregnancy counselling (box 1).

Combined IBD antenatal clinics where gastroenterologists and obstetricians are both present during the patient consultation can facilitate optimal care. This can avoid conflicting advice while providing consistent information, excellent and instant communications between teams, and decision making incorporating IBD and obstetric needs (especially delivery methods, appropriate medical treatments and thromboembolism prophylaxis). This model may be impractical for units with low numbers of pregnant women with IBD or those without obstetric departments in the same NHS Trust. Funding, under the current model, remains challenging for many units. As a minimum, units should establish local expertise with nominated link clinicians to communicate with obstetric services. In some areas, referral to regional maternal medicine centres for prepregnancy or antenatal advice may be appropriate.

The model for providing care for women with IBD during pregnancy requires improvement. In 89% of cases, women are looked after by their usual gastroenterologists, who may not have expertise in IBD and specifically IBD-related antenatal care. Although continuity of care has its merits, it is possible that in this scenario, some women may not receive the specialist care they need. Of concern, 30% of units did not review pregnant women with IBD routinely during pregnancy. This carries a risk of not treating active IBD, unnecessary/inappropriate cessation of medication and missed opportunities for input into decisions on the mode of delivery, breast feeding and childhood vaccinations. A robust system for review of patients with IBD during pregnancy should be established.

Rapid and effective communication is key to multidisciplinary IBD antenatal care. We found that 51% of units do not engage in routine communication. Ad hoc communication is insufficient for optimal care and indicates a lack of appreciation for the information obstetric services require to deliver optimal care. Obstetric teams should be provided with information on IBD disease activity and, if applicable, the impact of IBD on delivery, to plan and deliver obstetric care.18 Communication by letter is slow and haphazard as many NHS Trusts have separate paper and/or electronic systems for general hospital and obstetric care. Many women will be under midwifery-led care and not know the name of her obstetrician who may not ever receive the letter. Patients should receive a copy of the letter.

The need and timing of additional fetal growth scans for all women with IBD remain controversial and current guidelines do not mandate this.19 However, women with active IBD are at increased risk for fetal growth retardation.10 Women with active IBD should receive at least one additional growth scan in the third trimester.16 This underpins the need for close and effective communication between IBD and obstetric teams.

As a minimum, it is suggested that women with IBD should be reviewed by their gastroenterologist once during pregnancy.18 Other guidance suggests patients should be reviewed in the first and second trimesters and more frequently if the disease is active (14). However, almost one-third of the units reported reviewing their patients ‘as and when needed’. Although the current guidelines do not outline a definitive number of reviews required, there is an expectation that at least one routine review takes place, in order to promote optimal disease management and provide specialist pregnancy-related IBD care and counselling.18

Although the majority of women with IBD can have a normal vaginal delivery, the rates of caesarean sections are much higher for women with IBD than seen in the general population.5 10 Current perianal disease is a mandatory indication for a caesarean section, whereas ileoanal pouch surgery is a relative indication for a caesarean section. Despite clear guidance, one-third of respondents did not feel that gastroenterologists need to advise whether IBD should influence the mode of delivery.5 16 Worryingly, there was a clear lack of knowledge in a sizeable minority of respondents as 30% incorrectly identified previous but healed perianal disease and 20% incorrectly identified previous abdominal and/or pelvic surgery as an indication for a caesarean section.

There are a number of limitations to our study. Our data collection was dependent on clinicians completing an online survey and we achieved a response rate of 36% of gastroenterology units. The possibility of selection bias exists. Although this may accurately reflect UK practice it may not reflect models of healthcare delivery in other countries. This study was susceptible to non-response bias; clinicians with an interest or specialism in pregnancy-related IBD care are more inclined to respond. From this, it is not implausible that the responses we received may reflect better results than those likely to be seen in units that did not submit their responses. We acknowledge that we would not have provided comprehensive coverage of an entire spectrum of UK-based practice of managing IBD care in pregnancy. Finally, it is possible that due to the nature of our survey, responses reported may have been aspirational rather than reflecting usual care for most patients.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated considerable variations in the provision of services and care for pregnant women with IBD. Urgent improvements are required to develop more robust models of care and to improve the knowledge of clinicians providing IBD antenatal care. We hope that taken together, our findings and the publication of recent guidelines and UK-specific endorsed guidance statements on antenatal care provide much-needed impetus to the holistic care of women with IBD exemplifying the virtues of such personalised medicine through collaborative working and multidisciplinary expertise.

Footnotes

Contributors: SW, EM, CS and TG designed the study. SW and EM performed the data collection and initial analysis. SW, EM, TG, JL, KBK, AF, AK, KM, CN-P and CS reviewed and analysed the data. CS wrote the draft manuscript. SW, EM, TG, JL, KBK, AF, AK, KM and CN-P critically reviewed the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: CS has received unrestricted research grants from Warner Chilcott, Janssen and AbbVie, has provided consultancy to Warner Chilcott, Dr Falk, AbbVie, Takeda, Fresenius Kabi and Janssen, and had speaker arrangements with Warner Chilcott, Dr Falk, AbbVie, MSD, Pfizer and Takeda.CN-P had speaker arrangements with Dr Falk, UCB, Sanofi, Alliance and Alexion. KBK has provided consultancy to Amgen and PredictImmune, and had speaker arrangements with Janssen and Takeda. AK has provided consultancy to AbbVie, and had speaker arrangements with Pfizer, Janssen and Takeda. JL has received research grants from AbbVie and Takeda, has provided consultancy to AbbVie, Janssen, Pfizer, Viforpharma and Takeda and had speaker arrangements with AbbVie, MSD, Janssen, Pfizer and Takeda. All other authors do not declare any conflict of interest.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

No data are available. No data are available for public sharing.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1. Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology 2012;142:46–54. e42; quiz e30. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. de Lima A, Zelinkova Z, Mulders AGMGJ, et al. Preconception care reduces relapse of inflammatory bowel disease during pregnancy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:1285–92. 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Johnston RD, Logan RFA. What is the peak age for onset of IBD? Inflamm Bowel Dis 2008;14(Suppl 2):S4–5. 10.1002/ibd.20545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ban L, Tata LJ, Humes DJ, et al. Decreased fertility rates in 9639 women diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease: a United Kingdom population-based cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;42:855–66. 10.1111/apt.13354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van der Woude CJ, Ardizzone S, Bengtson MB, et al. The second European evidenced-based consensus on reproduction and pregnancy in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2015;9:107–24. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jju006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mañosa M, Navarro-Llavat M, Marín L, et al. Fecundity, pregnancy outcomes, and breastfeeding in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a large cohort survey. Scand J Gastroenterol 2013;48:427–32. 10.3109/00365521.2013.772229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beyer-Berjot L, Maggiori L, Birnbaum D, et al. A total laparoscopic approach reduces the infertility rate after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: a 2-center study. Ann Surg 2013;258:275–82. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182813741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Selinger CP, Ghorayeb J, Madill A. What factors might drive voluntary childlessness (vc) in women with IBD? does IBD-specific pregnancy-related knowledge matter? J Crohns Colitis 2016;10:1151–8. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marri SR, Ahn C, Buchman AL. Voluntary childlessness is increased in women with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2007;13:591–9. 10.1002/ibd.20082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tandon P, Govardhanam V, Leung K, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: risk of adverse pregnancy-related outcomes in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2020;51:320–33. 10.1111/apt.15587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hellerstedt WL, Pirie PL, Lando HA, et al. Differences in preconceptional and prenatal behaviors in women with intended and unintended pregnancies. Am J Public Health 1998;88:663–6. 10.2105/AJPH.88.4.663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barber JS, Axinn WG, Thornton A. Unwanted childbearing, health, and mother-child relationships. J Health Soc Behav 1999;40:231–57. 10.2307/2676350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Axinn WG, Barber JS, Thornton A. The long-term impact of parents' childbearing decisions on children's self-esteem. Demography 1998;35:435–43. 10.2307/3004012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kost K, Lindberg L. Pregnancy intentions, maternal behaviors, and infant health: investigating relationships with new measures and propensity score analysis. Demography 2015;52:83–111. 10.1007/s13524-014-0359-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lindberg L, Maddow-Zimet I, Kost K, et al. Pregnancy intentions and maternal and child health: an analysis of longitudinal data in Oklahoma. Matern Child Health J 2015;19:1087–96. 10.1007/s10995-014-1609-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mahadevan U, Robinson C, Bernasko N, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in pregnancy clinical care pathway: a report from the American gastroenterological association IBD parenthood project Working group. Gastroenterology 2019;156:1508–24. 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. de Lima A, Zelinkova Z, van der Ent C, et al. Tailored anti-TNF therapy during pregnancy in patients with IBD: maternal and fetal safety. Gut 2016;65:1261–8. 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Selinger C, Carey N, Cassere S, et al. Standards for the provision of antenatal care for patients with inflammatory bowel disease: guidance endorsed by the British Society of gastroenterology and the British maternal and fetal medicine Society. Frontline Gastroenterol 2020;7. 10.1136/flgastro-2020-101459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Salomon LJ, Alfirevic Z, Da Silva Costa F, et al. ISUOG practice guidelines: ultrasound assessment of fetal biometry and growth. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2019;53:715–23. 10.1002/uog.20272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee S, Seow CH, Adhikari K, et al. Pregnant women with IBD are more likely to be adherent to biologic therapies than other medications. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2020;51:544–52. 10.1111/apt.15596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Watanabe C, Nagahori M, Fujii T, et al. Non-adherence to medications in pregnant ulcerative colitis patients contributes to disease flares and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Dig Dis Sci 2020. 10.1007/s10620-020-06221-6. [Epub ahead of print: 06 Apr 2020]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Laube R, Selinger CP. Letter: pregnant women with IBD are more likely to be adherent to biologic therapies than other medications. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2020;51:915–6. 10.1111/apt.15686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data are available. No data are available for public sharing.