Abstract

Perianal manifestations of Crohn’s disease constitute a distinct disease phenotype commonly affecting patients and conferring an increased risk of disability and disease burden. Much research has gone into management of fistulising manifestations, with biological therapy changing the landscape of treatment. In this article, we discuss the up-to-date surgical and medical management of perianal fistulas, highlighting current consensus management guidelines and the evidence behind them, as well as future directions in management.

Keywords: crohn's disease, gastrointestinal fistulae

Introduction

Perianal fistulising Crohn’s disease (CD) was one of the first phenotypes of CD described and remains a more challenging manifestation, with a recognised propensity to a more aggressive disease course.1 2 Other perianal manifestations of CD can coexist and these include non fistulising manifestations including strictures, stenosis, ulceration, fissures, haemorrhoids, skin tags and, rarely, malignancy. These manifestations and their nuanced management have previously been described by our group.3 Perianal fistulas are the initial manifestation and the presenting complaint in 10% of Crohn’s diagnoses4 and occur in up to one-third of patients with CD.5 In this review, we discuss recent updates in the management of fistulising CD, specifying Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) recommendations6 and levels of evidence (http://www.cebm.net/oxford-centre-evidence-based-medicine-levels-evidence-march-2009) from referenced consensus guidelines.

Consensus on best management

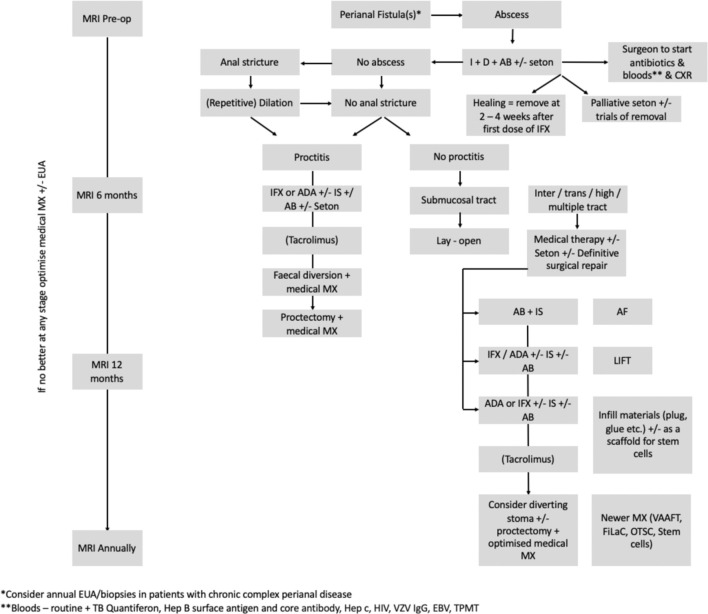

Recent consensus guidelines (British Society of Gastroenterology, European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation)7–9 advocate a multidisciplinary approach as standard of care in the management of perianal Crohn’s fistulising disease. Retrospective evidence from three UK referral centres suggest delays in accessing antitumour necrosis factor (TNF) therapy for patients perianal disease, which may have adverse effect.10 Our model of multidisciplinary management includes the delivery of joint outpatient clinics with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) gastroenterologist and surgeon conducting a joint consultation (with radiological input as necessary), which aids prompt and decisive assessment and management for patients at decision nodes. This facilitates the instigation of multimodal surgical and medical treatment (figure 1) with a combined decision from professionals and a fully informed patient, and adjunctive steps including monitoring, psychological support and access to additional IBD services.11 Best outcomes occur with combination of medical and surgical management, resulting in improved healing, decreased risk of relapse and increased time to relapse.12 13

Figure 1.

St Mark’s Algorithm for perianal Crohn’s disease (modified from Gecse et al.9). ADA, adalimumab; CXR, chest x-ray; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; EUA, examination under anaesthesia; FiLaC, fistula tract laser closure; Hep, hepatitis; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IFX, infiximab; IS, immunosuprresant; LIFT, ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract; MX, management; OTSC, over-the-scope clp; TB, tuberculosis; TPMT, thiopurine methyltransferase levels; VAAFT, video-assisted anal fistula treatment; VZV, varicella zoster virus.

A 2016 review of consensus statements in perianal fistula14 demonstrated good consensus with high-quality evidence in certain areas of fistula management (imaging/influence of proctitis on outcome). Contrast-enhanced pelvic MRI and endoanal ultrasound (in the absence of rectal stenosis) were considered the best imaging approaches (evidence level 2)8 in the assessment of perianal fistulas. Proctitis alters treatment options and has a negative effect on outcomes, including decreased fistula healing and increased fistula recurrence, and proctosigmoidoscopy is advocated routinely in initial evaluation (evidence level 2).8 Examination under anaesthesia also improves this assessment (GRADE: strong recommendation, high-quality evidence)7 and can be used as a diagnostic and monitoring tool, as those with chronic fistulas/perianal disease, require a heightened suspicion due to a risk of anal/rectal cancer15 16

Medical treatment (antibiotics, immunomodulators, biological therapy)

Antibiotics

Antibiotics alone have failed to demonstrate long-term benefit17 and are not recommended (GRADE: weak recommendation, low-quality evidence).18 However, randomised controlled trials have demonstrated superiority of combination therapies (ciprofloxacin and anti-TNF) in comparison with biologic therapy alone.19 20

Antibiotics are recommended as adjunctive treatment in combination with abscess drainage prior to commencement of anti-TNF agents (GRADE: strong recommendation, very low-quality evidence).7

Immunomodulators

Immunomodulators (eg, azathioprine/mercaptopurine) are used, but evidence in monotherapy is indirect, gleaned from secondary endpoints in clinical studies assessing efficacy for luminal disease.3 No prospective randomised trials exist. Importantly, their onset of action is generally 3–4 months, which has implications for those needing acute therapy. Monotherapy is not recommended for fistula closure (GRADE: weak recommendation, very low-quality evidence).18 A 2016 Cochrane review found no difference in fistula response among patients treated with azathioprine versus placebo (RR 2.0, 95% CI 0.67 to 5.93).21 A significant shortcoming of the review was the small number of patients included (only 18 patients) and the overall quality of data for included patients was found to be low. The biological therapies have changed the therapeutic landscape, and more recent studies have focused on thiopurine use in combination with anti-TNF agents.22 The Study of Biologic and Immunomodulator Naive Patients in Crohn’s Disease trial demonstrated superiority of combination therapy with azathioprine and infliximab22 in luminal disease. Concomitant therapy (with azathioprine or methotrexate) reduces the risk of development of antidrug antibodies in luminal disease.23 24 There is, however, insufficient evidence regarding this strategy or its effect on fistula healing in perianal CD18 25 26 (GRADE: weak recommendation, very low-quality evidence).

Biological therapy

Most guidelines recommend biological therapy (anti-TNF) for patients with complex/moderate-to-severe perianal CD9 27 and this is largely based on two prospective randomised trials28 29 and several other non-randomised/real-world data,30–32 demonstrating efficacy with induction and maintenance therapy. In a recent UK survey of expert gastroenterologists with IBD interest, just over half (56/93 respondents) use anti-TNF and 54/93 respondents favoured thiopurines. However, 44% respondents used these in combination, and only one-third would combine antibiotics, thiopurines and anti-TNF therapy (31/93).33 While there are limitations to survey-based research, this suggests some discrepancy between consensus guidelines and real-world practice.

Which biological therapy?

The anti-TNF agents, and in particular infliximab, are supported by the greatest weight of evidence among the biological therapies, although some of the evidence is indirect as fistula healing was not a primary endpoint in some of the randomised trials which evaluated their efficacy.28 29 There has also been a reported tendency towards benefit with adalimumab for induction and maintenance of remission (GRADE: weak recommendation, very low-quality evidence).18 Newer biological therapies like vedolizumab (GRADE: weak recommendation, low-quality evidence)18 and ustekinumab have had emerging reports of use in patents with perianal fistula with some success,26 34 however, data are still rudimentary and inconclusive. These will need to be evaluated further to determine their true efficacy in perianal CD.

Measuring response

In studies in perianal Crohn’s fistulas (including the randomised trials with the anti-TNF agents), success is usually measured by clinical assessment of the fistula tracks and whether they close in response to treatment. This may rarely be accompanied by radiological assessment to confirm ‘healing’. The outcome measure ‘sustained fistula closure’ or ‘healing’ has been a challenging one, both to achieve and to define clinically because of the high rates of failure, recurrence or symptom relapse in the reported literature. The fistula drainage assessment is often used and assesses the external opening and discharge from it in response to gentle finger pressure, but the natural history of fistulae is to close their external openings intermittently and correlation with deep tissue healing has not been shown. In fact, when it occurs, radiological evidence of deep tissue healing lags behind clinical healing by a year.

There has been great heterogeneity in outcome reporting in interventional studies of perianal Crohn’s fistula.35 This heterogeneity impedes meta-analysis, making it difficult to determine and compare the role and value of interventions in perianal CD. A core outcome set for this disease has recently been published by a national collaborative group, and the importance of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) were emphasised in this process,36 as well as in an European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) consensus highlighting unmet needs in the study and management of perianal Crohn’s fistulas.27 A new disease-specific PROM, the Crohn’s anal fistula quality of life (QoL) scale, has recently been developed which may aid patient-centred evaluation of treatment in a challenging landscape of heterogeneous outcomes and multiple treatment options with limited data.37

Dosing of anti-TNF agents, loss of response and switching therapy

With the anti-TNF has come an understanding that the response an individual patient will have to a specific anti-TNF agent and dose, is difficult to predict compared with non-biological therapies.38 In luminal Crohn’s about one-third of patients, do not respond to anti-TNF therapy (primary non-response) and almost half of those who do, subsequently lose response (ie, secondary loss of response) over time, requiring dose escalation or switch in therapy.39–46 Reasons for loss of response are not fully understood, but are thought to be multifactorial and in secondary cases, include immunogenicity, whereby patients develop antibodies to anti-TNF drugs.38

In order to optimise outcomes, there has been recent interest in assessment and optimisation of therapeutic dosing of anti-TNF agents. Optimal trough levels have been suggested for luminal disease but have not been fully evaluated for perianal disease. However, recent studies have suggested a fistula response and fistula closure benefit from higher serum infliximab trough levels47 48 and supranormal trough levels are often sought when symptoms persist.

For those patients who lose response, results of switching therapy are modest and largely short-term data exist,49–51 however, due to limited options in those who lose response, empirical trials of other biologics are suggested. Local injection of anti-TNF has also been used in a few pilot studies of patients with refractory fistulas with suggested benefit, however, the limited data, variable dosing regime, outcome measures and short-term nature of the data, make this therapeutic option difficult to draw conclusions about.52

Withdrawal of biological therapy

Several studies have addressed the issue of withdrawal of biological therapy after fistula remission with inconclusive results, perhaps due to heterogeneity in the disease phenotype included, and variability in definitions/duration of clinical remission prior to withdrawal.38 It is proposed that anti-TNF-α agents in patients with IBD who respond should not be routinely stopped, especially in those with disabling features of disease and/or at high risk of relapse,38 53 of which perianal CD represents a significant cohort. Retrospective data suggest that even achieving radiological fistula healing does not equate with cure, with a significant proportion of patients developing recurrence on withdrawal of biological therapy.54

Surgical therapy for perianal Crohn’s fistulas

Seton use and removal

Consensus exists with regard to the principles of surgical treatment in fistulising perianal CD, particularly with regard to the need for drainage of any collections/abscesses prior to commencement of anti-TNF therapy (GRADE: strong recommendation, very low-quality evidence).7 7 The insertion of a loose seton is recommended (GRADE: strong recommendation, moderate-quality evidence),7 and this in conjunction with medical treatment in a drained fistula complex, aims to reduce the risk of abscess formation and improve the likelihood of success of medical treatment.55 56 This represents the standard approach for symptom control in most guidelines. Corroborative results for this strategy were reported in the recent multicentre study57 (involving 19 European centres), a randomised trial assessing multimodal treatment of perianal fistulas in Crohn's disease, ie. seton versus anti-TNF versus advancement plasty (PISA). The authors reported the study stopped by the data safety monitoring board because of a poor outcome in the seton drainage alone arm57 although with only few numbers having undergone intervention (ie, 10 vs 6 vs 3 in each group). However, the design of the PISA study may have worked against a non-curative, symptom control arm into which patients were randomised when they might instead have been offered curative medical or surgical treatments in the other arms. The registry side of the PISA trial in which patients selected their own treatment arm to align with their expectations and goals, did not find the same poor outcomes in the seton arm.

There is debate as to the optimum seton material and timing of insertion/removal of setons. This is also dependent on the goals of treatment, that is, whether aiming for fistula healing (medically/surgically) or long-term drainage/prevention of abscess formation. For medical treatment, limited evidence exists regarding optimal timing of removal to maximise the chance of healing with concomitant medical therapy. Early studies with anti-TNF suggested an increased risk of abscess recurrence when stopped prior to 2 weeks postinfliximab induction, however, subsequent studies have been inconclusive in regard to the duration of seton drainage and its role in prevention of abscess recurrence.58 59 Some studies have suggested removal prior to 2 months is associated with higher closure rates,57 60 however, specific data answering this question are lacking. Given the findings of the Admire study and outcomes from surgical repair (see below), IBD multidisciplinary team meetings (MDTs) might ask whether seton removal alone represents an adequate option when the goal is fistula closure, and whether a direct repair attempt at the time of seton removal in the context of optimised and effective medical treatment would be preferable.

Combined with surgical therapy, seton use for a period of a few weeks has been arbitrarily used in interventional studies with the intention to allow the fistula track to ‘mature’ prior to attempts at definitive repair. The aim is to reduce inflammation, however, prolonged setons may also induce epithelialisation, which could increase the risk of failure of the fistula repair as well as potentially play a role in fistula persistence.56 In the PISA study57 (mentioned above) all three arms underwent loose seton insertion and a 2-week course of antibiotics to reduce inflammation. This was followed by subsequent removal at 6 weeks after induction in the anti-TNF group and 8–10 weeks in the surgery group (at the time of repair, after anti-TNF induction). Unfortunately, the results do not allow for interpretation of the duration of seton use and further work is required in this area to clarify optimum timing of seton removal.

Fistula repair

The selection of appropriate options for local surgical repair of perianal fistula relies heavily on an understanding of fistula anatomy. In CD, other factors are known or thought likely to influence surgical options and outcomes. Classification is, therefore, crucial to guide patient selection for a given technique, and unfortunately remains poor.

The American Gastroenterological Association 2003 guidelines represent the last major undertaking in this regard,17 and currently, there is no classification system designed to aid algorithmic management of different phenotypes.

Fistulotomy and sphincter preserving procedures

Fistulotomy is rarely appropriate in CD, due to the risks of impairment of continence, recurrence and poor wound healing, however, it can be used very occasionally for superficial/very low intersphincteric fistulas in patients without proctitis or other features of perianal disease (GRADE: weak recommendation, very low-quality evidence).9 Sphincter preserving procedures (SPPs) may be considered and data on drainage procedures (long term loose seton), disconnection procedures (advancement flaps, the LIFT procedure), infill procedures (glues, plugs) and ablative procedures (video-assisted anal fistula treatment (VAAFT), fistula tract using laser (FiLaC)), while mostly limited to case series, have shown feasibility in CD (GRADE: weak recommendation, low-quality evidence).9

Disconnection procedures

Endorectal advancement flaps involve the creation of a rectal flap from the adjacent tissue and using it to cover the internal opening of the fistula. Similar to the LIFT procedure (ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract), it disconnects the fistula tract from the anorectal lumen. These two procedures have been used in perianal fistulising Crohn’s patients with limited success.3 61 Proponents advocate advancement flap use in the absence of proctitis and reviews have described initial healing rates of up to 85%, although 1-year recurrence rates were up to 50%.62 63 The LIFT procedure is limited to small case series demonstrating clinical healing in just over half of the patients reported.64 65

Infill procedures

Anal fistula plugs have been proposed to achieve closure of fistula tracts and subjected to a randomised trial involving 106 patients randomised to seton removal (n=52) vs fistula plug(n=54). They demonstrated non-superiority to seton-use alone, in terms of week 12 fistula closure rates (31.5% in patients treated with fistula plug vs 23.1% in patients with removal of seton alone (RR 1.31, 95% CI 0.59 to 4.02, p=0.19)).66 Systematic reviews analysing case series describe a benefit to the plug in CD but highlight the paucity of data in Crohn’s population, with small study cohorts, widely varying closure rates between studies, grouping of fistulas in Crohn’s cohorts with other types.67 68 Fibrin glue has also been used in Crohn’s fistula and is instilled into the tract often with concomitant closure of the internal opening with the aim of causing tract fibrosis and healing (similar to the plug). There is again a paucity of literature and they have fallen out of routine practice with no convincing evidence of increased or sustained healing with these techniques over others.

Ablative procedures

These techniques involve ablation of the FiLaC or electrocautery (VAAFT) with or without closure of the internal opening. The ablation of the fistula tract lining play a role in tackling certain aspects of fistula pathogenesis including removal of epithelialisation and obliteration of the dead space.56 While feasibility has been demonstrated, only a few case series have been reported, although with promising results.69 As these procedures are in their infancy, they require familiarity with new equipment, establishing of learning curves, leading to an unmet need for evaluation in larger numbers of patients with perianal fistula to understand their role in multimodal treatment. Data are limited to small series and there is an understandably lower uptake of some of these sphincter sparing procedures as options of therapy among colorectal surgeons managing Crohn’s perianal fistula patients.70 In a recent UK survey70 of consultant colorectal surgeons (n=133 respondents), a majority of respondents (approximately 70%) demonstrated a tendency towards conservative options considering sepsis drainage and seton insertion followed by subsequent removal. Sphincter sparing procedures such as advancement flap/fistula plug, LIFT, fistulectomy and fibrin glue were less commonly considered (fewer than 40%) and even less so were the more novel ablative procedures (fewer than 5%). No attempt was made to determine whether surgeons indicating they would consider offering SPPs in CD ever actually undertake any such procedures.

At present, the bulk of the (very limited) data in sphincter sparing treatments suggest that those which succeed in robust disconnection of the track (advancement flap/LIFT) from the gut lumen offer the greatest promise of healing. However, an emerging concept is that of symptom amelioration, which may lend itself to some of the novel techniques with reported minimal effects on continence, minimal morbidity with suitability to repeated attempts being used within an aggressive, proactive algorithm of symptom control, including medical treatment, seton drainage and VAAFT to reduce symptoms of pain and discharge, for example.71 SPPs have an obvious appeal in patients with Crohn’s perianal fistula due to the need to preserve sphincter function in patients with a destructive disease process and the potential for a loose stool in years to come, and also to avoid problems with defective wound healing. However, their ability to actually heal Crohn’s perianal fistulas remains to be seen.

Mesenchymal stem cells

Intrafistula injection of mesenchymal stem cells has been shown to be safe and has shown benefit in phase I, II and III clinical studies in previously refractory complex fistula,72–74 and are recognised as a promising avenue of treatment.75 The largest study is a randomised controlled trial by Panés et al 76 reporting significantly higher rates of combined remission (clinical and radiological remission) in stem cell treated patients compared with those in the comparator arm at 24 weeks, with the results maintained at 52 weeks.77 These stem cells are thought to bring to bear immunomodulatory, immunosuppressive and wound healing properties, however, the exact mechanism is unknown. A systematic review of studies investigating their use reported benefit when compared with controls, however, this was short term (6–24 weeks) and not sustained past 24 weeks (at which point, there was no significant difference).78 Despite this, almost all patients enrolled in trials for stem cells were refractory to standard therapy and, regardless of the origin of the mesenchmal stem cells (MSCs), or the dose and method of administration, results have largely suggested superior efficacy compared with conventional therapy in a difficult-to-treat subgroup.3 In Europe, stem cell therapy has been granted approval from the European Medicines Agency,79 and a postmarketing registry aims to capture real world efficacy/safety.80 The Admire II study (Adult Allogeneic Expanded Adipose-Derived Stem Cells (eASC) for the Treatment of Complex Perianal Fistula(s) in Patients with CD) is currently recruiting in the USA and Europe and will soon open in the UK, aiming to demonstrate efficacy and longer-term outcomes. Although the combined remission endpoint includes radiological remission, the definition of this is weak and it is not clear whether fistulae treated with MSCs genuinely heal. However, small number of patients followed for longer periods do seem to maintain closed fistulae. The delta between the treatment and comparator arms in Admire-CD was small but the comparator arm represents a higher level of treatment than the current standard of care, with optimised medical treatment, followed by two operations, one to curette and prepare the tract and the second, 2–3 week slater, to clean it again and to close the internal opening. That this arm demonstrated combined remission in around a third of patients supports the argument that seton removal alone is harder to justify if fistula closure is the goal of treatment.

Refractory perianal disease and temporary faecal diversion/proctectomy

The durability of maintenance therapy over years has not been defined for Crohn’s perianal fistula, and consequently, the true frequency of loss of efficacy and requirement of anti-TNF dose intensification or drug switch in the long term is not fully understood.51 Few treatment options exist for drug-treatment-refractory patients, and repeated surgical options can be associated with substantial morbidity (eg, sphincter injury and continence impairment). A recent national survey revealed highlighted divergent practice including choices of definitive surgery and multimodal management.70 This points to the absence of an optimal strategy27 and a significant proportion of patients’ fistulas are refractory to treatment, with limited options (even with the recent introduction of stem cell therapy)26 76 81 and severe and debilitating symptoms; for them, faecal diversion represents the only option for symptom control.

Faecal diversion (either in the form of defunctioning colostomy or ileostomy) has been used as a means of therapy on its own, as well as an adjunct to complex fistula operations. A meta-analysis of 16 cohort studies (556 patients) found that 63.8% (95% CI 54.1% to 72.5%) of patients had early clinical response after faecal diversion for refractory Crohn’s fistulas. Despite the decision to defunction being regarded as temporary, the same study reported that restoration of bowel continuity was only attempted in 34.5% (95% CI 27.0% to 42.8%) of patients, and was successful (without relapse of symptoms or need for additional surgery) in only 17% of patients.82 Permanent faecal diversion including proctectomy is considered in severe and refractory perianal disease. Proctectomy is more frequent in patients with other manifestations of anorectal CD, and the presence of proctitis, colonic disease, rectovaginal fistula and anorectal strictures are associated with an increased risk of proctectomy in the presence of fistula.83 In the aforementioned review, around 42% of patients eventually required proctectomy, following primary or secondary non/loss of response to initial diversion, or relapse following restoration of continuity.82 This does not always signify the end of the journey either, as a combination of immunosuppressive medications and chronic disease often mean the rates of poor perineal wound healing are high.84 Other postoperative complications include recurrent abscess and fluid collections in the ‘dead space’ created, and damage to pelvic nerves. Proctectomy is often seen as a failure of management but in a few patients with very severe perianal disease and/or proctitis, it may be a life-changing intervention and the concept of a stoma representing failure may be iatrogenic. Careful discussion and counselling are crucial and for some patients, rather than meaning failure, proctectomy is the only intervention which leads to an improved QoL.3 85 Guidelines recommend faecal stream diversion in patients with severe refractory disease (ie, to medical therapy), with counselling regarding low rates of successful reversal and likelihood of progression to proctectomy (GRADE: strong recommendation, low-quality evidence).7 8

Conclusion

There remain many limitations to the current management of perianal CD, notwithstanding our limited understanding of the reasons for fistula persistence/aetiopathogenesis.56 Existing management algorithms (figure 1) rely on a stepwise approach involving abscess drainage, seton insertion, combined antibiotic/immunomodulator/anti-TNF treatment and then sometimes (perhaps too infrequently) progression on to reparative surgery and in some cases, to defunctioning ostomy or proctectomy.56 Further work in larger numbers of patients is required to improve our understanding and optimise the various options encompassed in multimodal treatment strategies. Improvement in management will likely follow a renewed emphasis on classification, improved therapeutic drug monitoring, patient selection and outcomes in reparative surgery and the use of PROMs. At present, the principles of treatment of Crohn’s perianal fistulas are to drain the underlying sepsis and place setons, aggressively manage proctitis and medically treat the fistulas with a combination of antibiotics, immunosuppressants and anti-TNF therapy.86

Footnotes

Contributors: SOA, PT and AH conceptualised the review outline. SOA, KS, CT-B, NI and LR performed the literature review for the manuscript; SOA, KS, CT-B, NI and LR prepared the manuscript; JW, PL, PT and AH have reviewed and revised the manuscript critically, making key directional changes and prepared the final version of the manuscript. All authors approved the final draft prior to submission.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1. Bernell O, Lapidus A, Hellers G. Risk factors for surgery and postoperative recurrence in Crohn's disease. Ann Surg 2000;231:38–45. 10.1097/00000658-200001000-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Whelan G, Farmer RG, Fazio VW, et al. Recurrence after surgery in Crohn's disease. Relationship to location of disease (clinical pattern) and surgical indication. Gastroenterology 1985;88:1826–33. 10.1016/0016-5085(85)90007-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Adegbola SO, Pisani A, Sahnan K, et al. Medical and surgical management of perianal Crohn's disease. Ann Gastroenterol 2018;31:129–39. 10.20524/aog.2018.0236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hellers G, Bergstrand O, Ewerth S, et al. Occurrence and outcome after primary treatment of anal fistulae in Crohn's disease. Gut 1980;21:525–7. 10.1136/gut.21.6.525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lightner AL, Faubion WA, Fletcher JG. Interdisciplinary Management of Perianal Crohn’s Disease, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2004;328:1490. 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lamb CA, Kennedy NA, Raine T, et al. British Society of gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 2019;68:s1–106. 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gionchetti P, Dignass A, Danese S, et al. 3rd European Evidence-based Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Crohn’s Disease 2016: Part 2: Surgical Management and Special Situations. J Crohn’s Colitis 2017;11:135–49. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gecse KB, Bemelman W, Kamm MA, et al. A global consensus on the classification, diagnosis and multidisciplinary treatment of perianal fistulising Crohn's disease. Gut 2014;63:1381–92. 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee MJ, Freer C, Adegbola S, et al. Patients with perianal Crohn's fistulas experience delays in accessing anti-TNF therapy due to slow recognition, diagnosis and integration of specialist services: lessons learned from three referral centres. Colorectal Dis 2018;20:797–803. 10.1111/codi.14102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sahnan K, Adegbola SO, Fareleira A, et al. Medical-Surgical combined approach in perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease (CD): doing it together. Curr Drug Targets 2019;20:1373–83. 10.2174/1389450120666190520103454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hyder SA, Travis SPL, Jewell DP, et al. Fistulating anal Crohn's disease: results of combined surgical and infliximab treatment. Dis Colon Rectum 2006;49:1837–41. 10.1007/s10350-006-0656-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. El-Gazzaz G, Hull T, Church JM. Biological immunomodulators improve the healing rate in surgically treated perianal Crohn's fistulas. Colorectal Dis 2012;14:1217–23. 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.02944.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. de Groof EJ, Cabral VN, Buskens CJ, et al. Systematic review of evidence and consensus on perianal fistula: an analysis of national and international guidelines. Colorectal Dis 2016;18:O119–34. 10.1111/codi.13286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Beaugerie L, Carrat F, Nahon S, et al. High risk of anal and rectal cancer in patients with anal and/or perianal Crohn's disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;16:892–9. 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.11.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Corr A, Reza L, Lung P, et al. P279 Early detection of mucinous adenocarcinoma within fistulating peri-anal Crohn’s disease. J Crohn’s Colitis 2020;14:S290–1. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz203.408 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sandborn WJ, Fazio VW, Feagan BG, et al. AGA technical review on perianal Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 2003;125:1508–30. 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.08.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Torres J, Bonovas S, Doherty G, et al. ECCO guidelines on therapeutics in Crohn's disease: medical treatment. J Crohns Colitis 2020;14:4–22. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. West RL, van der Woude CJ, Hansen BE, et al. Clinical and endosonographic effect of ciprofloxacin on the treatment of perianal fistulae in Crohn's disease with infliximab: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;20:1329–36. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02247.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dewint P, Hansen BE, Verhey E, et al. Adalimumab combined with ciprofloxacin is superior to adalimumab monotherapy in perianal fistula closure in Crohn's disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled trial (ADAFI). Gut 2014;63:292–9. 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Prefontaine E, MacDonald JK, Sutherland LR. Azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine for induction of remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, et al. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1383–95. 10.1056/NEJMoa0904492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ong DEH, Kamm MA, Hartono JL, et al. Addition of thiopurines can recapture response in patients with Crohn's disease who have lost response to anti-tumor necrosis factor monotherapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;28:1595–9. 10.1111/jgh.12263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Baert F, Noman M, Vermeire S, et al. Influence of immunogenicity on the long-term efficacy of infliximab in Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med 2003;348:601–8. 10.1056/NEJMoa020888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schröder O, Blumenstein I, Schulte-Bockholt A, et al. Combining infliximab and methotrexate in fistulizing Crohn's disease resistant or intolerant to azathioprine. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;19:295–301. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01850.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kotze PG, Shen B, Lightner A, et al. Modern management of perianal fistulas in Crohn's disease: future directions. Gut 2018;67:1181–94. 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gecse KB, Sebastian S, de HG, et al. Results of the Fifth Scientific Workshop of the ECCO [II]: Clinical Aspects of Perianal Fistulising Crohn’s Disease—the Unmet Needs: Table 1. J Crohn’s Colitis 2016:jjw039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan S, et al. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med 1999;340:1398–405. 10.1056/NEJM199905063401804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sands BE, Anderson FH, Bernstein CN, et al. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med 2004;350:876–85. 10.1056/NEJMoa030815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Colombel J-F, Schwartz DA, Sandborn WJ, et al. Adalimumab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease. Gut 2009;58:940–8. 10.1136/gut.2008.159251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Castaño-Milla C, Chaparro M, Saro C, et al. Effectiveness of adalimumab in perianal fistulas in Crohn's disease patients naive to anti-TNF therapy. J Clin Gastroenterol 2015;49:34–40. 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schreiber S, Lawrance IC, Thomsen O Ø, et al. Randomised clinical trial: certolizumab pegol for fistulas in Crohn's disease - subgroup results from a placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;33:185–93. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04509.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lee MJ, Brown SR, Fearnhead NS, et al. How are we managing fistulating perianal Crohn’s disease? Results of a national survey of consultant gastroenterologists. Frontline Gastroenterol 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tadbiri S, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Serrero M, et al. Impact of vedolizumab therapy on extra-intestinal manifestations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a multicentre cohort study nested in the OBSERV-IBD cohort. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018;47:485–93. 10.1111/apt.14419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sahnan K, Adegbola SO, Tozer PJ, et al. P245 a systematic review of outcomes reported in studies on fistulising perianal Crohn's disease. J Crohn’s Colitis 2017;11:S202. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx002.370 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sahnan K, Tozer PJ, Adegbola SO, et al. Developing a core outcome set for fistulising perianal Crohn's disease. Gut 2019;68:226–38. 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-315503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Adegbola S, Dibley L, Sahnan K, et al. P487 Development and validation of a new patient-reported outcome measure for Crohn’s perianal fistula: Crohn’s anal fistula quality-of-life (CAF-QoL) scale. J Crohn’s Colitis 2020;14:S428. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz203.616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Adegbola SO, Sahnan K, Warusavitarne J, et al. Anti-TNF Therapy in Crohn’s Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2018;19:2244–22. 10.3390/ijms19082244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yarur AJ, Rubin DT. Therapeutic drug monitoring of anti-tumor necrosis factor agents in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2015;21:1709–18. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sandborn WJ, Abreu MT, D'Haens G, et al. Certolizumab pegol in patients with moderate to severe Crohn's disease and secondary failure to infliximab. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;8:688–95. 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Enns R, et al. Adalimumab induction therapy for Crohn disease previously treated with infliximab: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:829–38. 10.7326/0003-4819-146-12-200706190-00159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ford AC, Sandborn WJ, Khan KJ, et al. Efficacy of biological therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:644–59. 10.1038/ajg.2011.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sprakes MB, Ford AC, Warren L, et al. Efficacy, tolerability, and predictors of response to infliximab therapy for Crohn's disease: a large single centre experience. J Crohn's Colitis 2012;6:143–53. 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Allez M, Karmiris K, Louis E, et al. Report of the ECCO pathogenesis workshop on anti-TNF therapy failures in inflammatory bowel diseases: definitions, frequency and pharmacological aspects. J Crohns Colitis 2010;4:355–66. 10.1016/j.crohns.2010.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ben-Horin S, Chowers Y. Review article: loss of response to anti-TNF treatments in Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;33:987–95. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04612.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ben-Horin S. Loss of response to anti-tumor necrosis factors: what is the next step? Dig Dis 2014;32:384–8. 10.1159/000358142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yarur AJ, Kanagala V, Stein DJ, et al. Higher infliximab Trough levels are associated with perianal fistula healing in patients with Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;45:933–40. 10.1111/apt.13970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Davidov Y, Ungar B, Bar-Yoseph H, et al. Association of Induction Infliximab Levels With Clinical Response in Perianal Crohn’s Disease. J Crohn’s Colitis 2016:jjw182. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cohen BL, Sachar DB. Update on anti-tumor necrosis factor agents and other new drugs for inflammatory bowel disease. BMJ 2017;357:j2505. 10.1136/bmj.j2505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Billioud V, Sandborn WJ, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Loss of response and need for adalimumab dose intensification in Crohn's disease: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:674–84. 10.1038/ajg.2011.60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gisbert JP, Panés J. Loss of response and requirement of infliximab dose intensification in Crohn's disease: a review. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:760–7. 10.1038/ajg.2008.88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Adegbola SO, Sahnan K, Tozer PJ, et al. Review of local injection of anti-TNF for perianal fistulising Crohn's disease. Int J Colorectal Dis 2017;32:1539–44. 10.1007/s00384-017-2899-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Papamichael K, Vermeire S. Withdrawal of anti-tumour necrosis factor α therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol Gastroenterol 2015;21:4773–8. 10.3748/wjg.v21.i16.4773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Mak WY, Lung PFC, Hart A. In Patients With Perianal Crohn’s Fistulas, What Are the Outcomes When ‘Radiological Healing’ Is Achieved? Does Radiological Healing of Perianal Crohn’s Fistulas Herald the Time Point for Stopping a Biologic? J Crohn’s Colitis 2017;11:1506. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Regueiro M, Mardini H. Treatment of perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease with infliximab alone or as an adjunct to exam under anesthesia with Seton placement. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2003;9:98–103. 10.1097/00054725-200303000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tozer PJ, Lung P, Lobo AJ, et al. Review article: pathogenesis of Crohn's perianal fistula-understanding factors impacting on success and failure of treatment strategies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018;48:260–9. 10.1111/apt.14814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wasmann KA, de Groof EJ, Stellingwerf ME, et al. Treatment of Perianal Fistulas in Crohn’s Disease, Seton Versus Anti-TNF Versus Surgical Closure Following Anti-TNF [PISA]: A Randomised Controlled Trial. J Crohn’s Colitis 2020;21. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bouguen G, Siproudhis L, Gizard E, et al. Long-Term outcome of perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease treated with infliximab. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;11:975–81. 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.12.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tanaka S, Matsuo K, Sasaki T, et al. Clinical advantages of combined Seton placement and infliximab maintenance therapy for perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease: when and how were the Seton drains removed? Hepatogastroenterology 2010;57:3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gaertner WB, Decanini A, Mellgren A, et al. Does infliximab infusion impact results of operative treatment for Crohn's perianal fistulas? Dis Colon Rectum 2007;50:1754–60. 10.1007/s10350-007-9077-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Stellingwerf ME, van Praag EM, Tozer PJ, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of endorectal advancement flap and ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract for cryptoglandular and Crohn's high perianal fistulas. BJS Open 2019;3:231–41. 10.1002/bjs5.50129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lee MJ, Heywood N, Adegbola S, et al. Systematic review of surgical interventions for Crohn's anal fistula. BJS Open 2017;1:55–66. 10.1002/bjs5.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Soltani A, Kaiser AM. Endorectal advancement flap for cryptoglandular or Crohn's fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum 2010;53:486–95. 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181ce8b01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kamiński JP, Zaghiyan K, Fleshner P. Increasing experience of ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract for patients with Crohn's disease: what have we learned? Colorectal Dis 2017;19:750–5. 10.1111/codi.13668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Gingold DS, Murrell ZA, Fleshner PR. A prospective evaluation of the ligation of the intersphincteric tract procedure for complex anal fistula in patients with Crohn's disease. Ann Surg 2014;260:1057–61. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Senéjoux A, Siproudhis L, Abramowitz L, et al. Fistula Plug in Fistulising Ano-Perineal Crohn’s Disease: a Randomised Controlled Trial. J Crohn’s Colitis 2016;10:141–8. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Nasseri Y, Cassella L, Berns M, et al. The anal fistula plug in Crohn's disease patients with fistula-in-ano: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis 2016;18:351–6. 10.1111/codi.13268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. O'Riordan JM, Datta I, Johnston C, et al. A systematic review of the anal fistula plug for patients with Crohn's and non-Crohn's related fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum 2012;55:351–8. 10.1097/DCR.0b013e318239d1e4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Adegbola SO, Sahnan K, Pellino G, et al. Short-Term efficacy and safety of three novel sphincter-sparing techniques for anal fistulae: a systematic review. Tech Coloproctol 2017;21:775–82. 10.1007/s10151-017-1699-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Lee MJ, Heywood N, Sagar PM, et al. Surgical management of fistulating perianal Crohn's disease: a UK survey. Colorectal Dis 2017;19:266–73. 10.1111/codi.13462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Adegbola SO, Sahnan K, Tozer PJ, et al. Symptom amelioration in Crohn’s perianal fistulas using video assisted anal fistula treatment (VAAFT). J Crohn’s Colitis 2018:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. de la Portilla F, Alba F, García-Olmo D, et al. Expanded allogeneic adipose-derived stem cells (eASCs) for the treatment of complex perianal fistula in Crohn's disease: results from a multicenter phase I/IIa clinical trial. Int J Colorectal Dis 2013;28:313–23. 10.1007/s00384-012-1581-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. García-Olmo D, García-Arranz M, Herreros D, et al. A phase I clinical trial of the treatment of Crohn's fistula by adipose mesenchymal stem cell transplantation. Dis Colon Rectum 2005;48:1416–23. 10.1007/s10350-005-0052-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Garcia-Olmo D, Phd M, Phd G-A, et al. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy Expanded adipose-derived stem cells for the treatment of complex perianal fistula including Crohn’s disease (2008) Expanded adipose-derived stem cells for the treatment of complex perianal fistula including Crohn’s dis. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2017;8:1417–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Adamina M, Bonovas S, Raine T, et al. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Crohn’s Disease: Surgical Treatment Oded Zmora as ; on behalf of the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation [ECCO]. J Crohn’s Colitis 2020;2019:155–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Panés J, García-Olmo D, Van Assche G, et al. Expanded allogeneic adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (Cx601) for complex perianal fistulas in Crohn's disease: a phase 3 randomised, double-blind controlled trial. Lancet 2016;388:1281–90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31203-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Panés J, García-Olmo D, Van Assche G, et al. Long-Term efficacy and safety of stem cell therapy (Cx601) for complex perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 2018;154:1334–42. 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Lightner AL, Wang Z, Zubair AC, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of mesenchymal stem cell injections for the treatment of perianal Crohn's disease: progress made and future directions. Dis Colon Rectum 2018;61:629–40. 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Kotze PG, Spinelli A, Warusavitarne J, et al. Darvadstrocel for the treatment of patients with perianal fistulas in Crohn's disease. Drugs Today 2019;55:95–105. 10.1358/dot.2019.55.2.2914336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Carvello M, Lightner A, Yamamoto T, et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Perianal Crohn’s Disease. Cells 2019;8:764. 10.3390/cells8070764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Pellino G, Selvaggi F. Surgical Treatment of Perianal Fistulizing Crohn’s Disease: From Lay-Open to Cell-Based Therapy—An Overview. Sci World J 2014;2014:1–8. 10.1155/2014/146281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Singh S, Ding NS, Mathis KL, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: faecal diversion for management of perianal Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;42:783–92. 10.1111/apt.13356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Galandiuk S, Kimberling J, Al-Mishlab TG, et al. Perianal Crohn disease: predictors of need for permanent diversion. Ann Surg 2005;241:796–801. discussion 801-2. 10.1097/01.sla.0000161030.25860.c1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Yamamoto T, Bain IM, Allan RN, et al. Persistent perineal sinus after proctocolectomy for Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum 1999;42:96–101. 10.1007/BF02235190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Adegbola SO, Sahnan K, Tozer PJ, et al. Management of Perianal Crohn’s Disease in the Biologic Era. In: Coloproctology. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2017: 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 86. Tozer PJ, Burling D, Gupta A, et al. Review article: medical, surgical and radiological management of perianal Crohn's fistulas. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;33:5–22. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04486.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]