Abstract

In 1961, K Merendino ‘in pure curiosity’, while tracking the murmur of mitral regurgitation, placed his stethoscope ‘on the vertex of the head’, and ultimately led to a medical curiosity and exam finding that not only bears his name, but awes medical learners at all stages of their careers. Merendino and colleagues collected seven such cases of the ‘Murmur on Top of the Head’ building on the work of others who provided a detailed description of mitral regurgitation and noted murmur radiation to the neck and cervical/lumbosacral spine. The majority of patients suffered from rheumatic heart disease or subacute bacterial endocarditis in native heart valves. Here, we report on a case of the ‘Murmur on Top of the Head’ and provide the reader/listener with a direct recording of the ‘Merendino murmur’ (as well as its spinal correlate) in an elderly woman with a bioprosthetic mitral valve.

Keywords: valvar diseases, clinical diagnostic tests, radiology (diagnostics)

Background

In 1961, Merendino and Hessel more ‘in pure curiosity than recognisable purpose’, while tracking the murmur of mitral regurgitation, placed his stethoscope ‘on the vertex of the head, where to the surprise of the examiner, the systolic murmur could be clearly heard’, and ultimately led to a medical curiosity and physical examination finding that not only bears his name but continues to awe medical learners at all stages of their careers.1 Over the ensuing 6 years (1961–1967), Merendino and colleagues collected seven such cases of the ‘Merendino murmur’ or the ‘Murmur on Top of the Head’ building on the work of Bliefer et al who provided a detailed description of mitral regurgitation and Perloff and Harvey as well as Turrettini who noted murmur radiation to the neck and cervical/lumbosacral spine.2 3 In these cases, the majority of patients suffered from rheumatic heart disease, subacute bacterial endocarditis or to a lesser extent, rheumatic valvulitis and annular dilation with associated chordae tendineae rupture or direct leaflet excursion, all exclusively in native heart valves.1 3 Here, we report on a case of the ‘Murmur on Top of the Head’ and provide the reader/listener with a direct recording of the ‘Merendino murmur’ (as well as its spinal correlate) in an elderly woman with a bioprosthetic mitral valve.

Case presentation

A 70-year-old woman with a medical history of bioprosthetic mitral valve replacement (St Jude Biocor, 29 mm) secondary to endocarditis 13 years prior presented with progressively worsening dyspnoea on exertion accompanied by lower limb oedema, orthopnoea and early satiety. In the emergency department, she was haemodynamically stable. Laboratory diagnostics were unremarkable except for an elevated B-type natriuretic peptide (372 pg/mL) and a mildly elevated troponin I high sensitivity (64 ng/L). An ECG demonstrated left axis deviation, left atrial enlargement and left ventricular hypertrophy with poor R-wave progression. A transoesophageal echocardiogram performed 3 months prior to presentation demonstrated a left ventricular ejection fraction of 55%–60%, an appropriately seated 29-millimetre St Jude Biocor mitral bioprosthetic valve with a thickened medial cusp, and associated motion restriction. The lateral leaflet was noted to override the medial leaflet resulting in a central, although posteriorly directed jet that seemed to impinge on the medial wall of the left atrium. Moderate mitral regurgitation and a mean gradient of 6 mm Hg across the mitral valve at heart rate of 90 beats/min was noted (figure 1). Repeat transthoracic echocardiogram performed 1 month prior to presentation demonstrated hyperdynamic systolic function with an ejection fraction of 70%–75%. While the bioprosthetic mitral valve remained well seated, there was ongoing evidence of severely thickened mitral valve leaflets with a peak velocity of 1.8 m/s and a peak gradient across the mitral valve of 8 mm Hg.

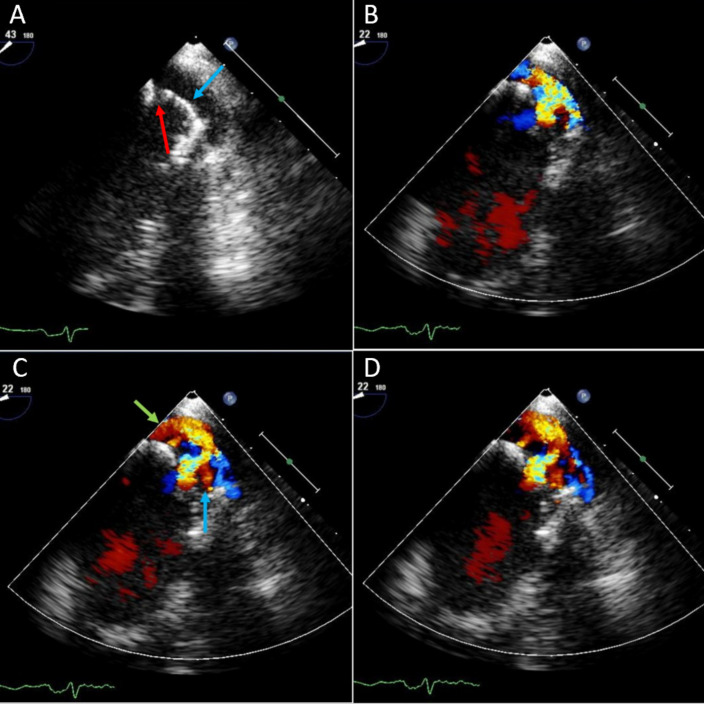

Figure 1.

Transoesophageal echocardiogram. Echocardiography (A) demonstrates a well-seated bioprosthetic mitral valve with a prolapsed, thickened anterior leaflet (blue arrow) and course of the posteriorly directed regurgitant jet (red arrow), (B) demonstrates the posteriorly directed jet at the start of systole, while (C) demonstrates prolapse of the anterior leaflet into the left atrium (below arrow), leading to a pathway which the regurgitant jet takes (green arrow), towards the posterior wall of the left atrium and (D) demonstrates the flow of blood as systole ends and diastole begins.

Physical examination demonstrated an otherwise well-appearing African–American woman with jugular venous pressure 6 cm above the sternal angle at 45°, and 2+ bilateral lower extremity oedema. Coarse crackles were noted in the posterior lung fields. Cardiac examination demonstrated a parasternal heave, thrill on palpation and a harsh, high-pitched, blowing, pansystolic murmur most prominent at the apex with radiation to the axilla that was augmented with hand grip and diminished with Valsalva manoeuvre. Placement of the stethoscope revealed radiation of the murmur to the cervical, thoracic and lumbosacral (online supplemental audio 1) spine. Much to the surprise of the observing medical students and residents, the stethoscope was placed on top of the head with appreciation of a murmur that similarly augmented with hand grip and diminished with Valsalva manoeuvre (online supplemental audio 2).

bcr-2021-245117supp001.mp3 (75.6KB, mp3)

bcr-2021-245117supp002.mp3 (77.4KB, mp3)

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was managed for a heart failure exacerbation with marked improvement in her symptomatology and was ultimately discharged on diuretics and instructions to follow with cardiology and cardiovascular surgery for valvular repair. She underwent a transcutaneous mitral valve replacement with postoperative echocardiogram demonstrating a preserved ejection fraction, and a well-seated, recently replaced 29-millimetre Edwards S3 valve. The bioprosthetic leaflets were noted to be thin and without restricted motion. Dynamics included a mean diastolic gradient of 5.4 mm Hg at 65 beats/min and a peak diastolic velocity of 1.9 m/s, and pressure half-time of 124 ms. She has not had another heart failure exacerbation and was subsequently taken off diuretic therapy.

Discussion

While the murmur of mitral regurgitation is classically described as radiating to the axilla, multiple prior reports have documented radiation to other locations. Perhaps, the most intriguing locations include radiation to the neck, to the spinal column and to the top of the head, as previously described.1 3 4 While the majority of these ‘unexpected’ murmurs occurred in the context of native valve rheumatic heart disease or subacute bacterial endocarditis secondary to ruptured chordae tendineae, several cases occurred without chordae rupture, with only rheumatic valvulitis and annular dilation.1 3 4 In contrast, no studies have demonstrated such findings in the context of a bioprosthetic valve. These early studies correctly posited that murmur radiation was dependent on the leaflet affected and subsequent regurgitant jet—the anterior leaflet resulted in a regurgitant stream directed towards the lateral wall with radiation to the axilla, whereas the posterior leaflet resulted in a regurgitant stream directed towards the base of the aorta to the aortic area.1 5 6 In addition to the leaflet affected, murmur radiation was also noted to be dependent on the patient’s body habitus. Merendino and Hessel attributed the murmur on top of the head to prerequisite factors such as rupture of the anterior leaflet chordae tendineae, mobile and flexible leaflets without calcifications and jet direction regardless of the underlying aetiology.1 Spinal radiation was posited to occur in the context of a posteriorly directed jet that made direct contact with the spine with associated bone conduction throughout the column.1Sufficiently high-energy, posteriorly directed jets would radiate by bone conduction to the skull or in those with a sufficiently small thoracic cavity.1 Nevertheless, the affected leaflets seemed to poorly correlate with the noted radiation1 given murmur appreciation not only in the neck, but also in the spine and to the top of the head with dysfunction of both the anterior and posterior leaflets.1

The patient presented in this case was noted not only to have a pan-spinal murmur, but also a murmur that radiated to the top of the head in the context of mitral valve regurgitation from a bioprosthetic mitral valve. Review of the transoesophageal echocardiogram clearly demonstrated anterior leaflet prolapse during systole with a resultant posteriorly directed jet focused on the posterior atrial wall. This posteriorly directed jet, coupled with the patients diminutive anterior–posterior chest diameter facilitated more direct contact with adjacent vertebral bodies, and subsequent murmur conduction in the rostral–caudal direction along the spine and to the vertex. While the Merendino murmur is certainly not novel, its report in the context of a bioprosthetic mitral valve is, and its physical manifestation is a medical curio that continues to awe the unsuspecting medical learner.

The murmur of mitral regurgitation may not only radiate to the axilla, but depending on the leaflet affected, to the scapula, the spinal column or the top of the head. This latter murmur, colloquially known as the Merendino murmur after its author, was first discovered in 1961 and subsequently codified in 1967 in a series of patients with native valve mitral regurgitation secondary to ruptured chordae tendineae tethering the anterior leaflets due to rheumatic fever or subacute bacterial endocarditis, or in patients with rheumatic valvulitis and associated annular dilation.1 The patient’s body size and direction of the murmur allowed for the murmur to be heard on the top of the head. There is no correlation between severity of the mitral regurgitation and the radiation of the murmur. This case demonstrates the Merendino murmur in the context of a bioprosthetic mitral valve and provides audio samplings highlighting not only the location of this murmur, but its augmentation and diminution with classic physical examination techniques.

Learning points.

This is a first time heard audio files of mitral regurgitation murmur radiating to the top of the head and lumbar spine.

Mitral regurgitation murmurs may radiate to multiple sites depending on the leaflet affected and the direction of the jet.

A Unique mitral regurgitation murmur that is heard in a patient with bioprosthetic valve which radiates to the top of the head.

Footnotes

Contributors: AM: wrote the case reports. AS: wrote part of the report. AA-A: review the paper. CH: mentored, reviewed and was part of planning of the case report.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s).

References

- 1.Merendino KA, Hessel EA. The "murmur on top of the head" in acquired mitral insufficiency. Pathological and clinical significance. JAMA 1967;199:892–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bleifer S, Dack S, Grishman A, et al. The auscultatory and phonocardiographic findings in mitral regurgitation. Am J Cardiol 1960;5:836–42. 10.1016/0002-9149(60)90064-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perloff JK, Harvey WP. Auscultatory and phonocardiographic manifestations of pure mitral regurgitation. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 1962;5:172–94. 10.1016/S0033-0620(62)80028-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sleeper JC, Orgain ES, McINTOSH HD. Mitral insufficiency simulation aortic stenosis. Circulation 1962;26:428–33. 10.1161/01.CIR.26.3.428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osmundson PJ, Callahan JA, Edwards JE. Ruptured mitral chordae tendineae. Circulation 1961;23:42–54. 10.1161/01.CIR.23.1.42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Askey JM. Spontaneous rupture of a papillary muscle of the heart; review with 8 additional cases. Am J Med 1950;9:528–40. 10.1016/0002-9343(50)90204-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bcr-2021-245117supp001.mp3 (75.6KB, mp3)

bcr-2021-245117supp002.mp3 (77.4KB, mp3)