Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of death from cancer in the UK. Sporadic CRC evolves from premalignant lesions of the colorectum, through a cumulative effect of acquired genetic and epigenetic alterations, typically over the course of several years. Endoscopic polypectomy of these at-risk lesions can prevent the development of CRC. The paucity of lymphatic vessels above the muscularis mucosae enables curative endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) of even very extensive lesions that are limited to the mucosa.1 2

This review is aimed at endoscopy trainees, consultants and allied healthcare professionals and describes the place of EMR in therapeutic colonoscopy, clarifying its capabilities and limits, as well as describing newer methods and adjuncts to EMR designed to prevent and treat recurrence.

When should EMR be performed?

EMR is a well-established therapeutic technique which can be performed as an outpatient, day-case procedure and has emerged as a safe, efficient and cost-effective alternative to surgery for suitable non-invasive lesions.

The use of fluid injection to facilitate polypectomy was first described in 1955 and by the 1990s was popularised by Japanese endoscopists and was termed EMR. Injection solutions are used to create a submucosal cushion, separating the colonic lesion from the underlying muscle layer to allow complete resection of the lesion and to prevent full thickness perforation and thermal injury to the colonic wall.

The vast majority of colorectal polyps are small, 10 mm or less in size. Most of these can be managed using standard snare polypectomy technique.3 EMR is considered the procedure of choice for more difficult polyps, including those greater than 20 mm in size, where submucosal invasion is not suspected and where location poses challenges, such as the involvement of haustral folds or within areas of diverticulosis. Although epidemiological data are lacking, approximately 10%–15% of polyps can be categorised as difficult.4 Lesions which cannot be resected using EMR are even fewer in number.

Accurate assessment of lesions to aid decision making is of paramount importance. All lesions should be described using well-known classification systems, such as Paris for morphology, Kudo or NBI International Colorectal Endoscopic for surface or pit pattern5 and the Size/Morphology/Site/Access Score for overall lesion description (table 1).6 The latter scoring system has recently been validated and shown to predict failed EMR, adverse events and adenoma recurrence (table 2).7

Table 1.

Endoscopic classification systems

| Classification system | Description | Features |

| Paris | Morphology | Ip, pedunculated; Isp, subpedunculated; Is, sessile IIa, flat elevated; IIb, completely flat; IIc, depressed III, excavated |

| Kudo | Pit pattern | I, normal, round II, star-shaped IIIs, small round or tubular; IIIL, long tubular IV, branched Vi, irregular; Vn, non-structured |

| NICE | Colour, vessels, surface pattern | 1, hyperplastic: lighter, lacy vessels, uniform 2, adenoma: brown vessels surrounding white tubular or branched structures 3, deep submucosal invasive cancer: brown to dark brown with disrupted vessels and amorphous surface |

NICE, NBI International Colorectal Endoscopic.

Table 2.

Scoring system for determining the difficulty of polypectomy (SMSA Score)

| Parameter | Range | Points |

| Size (cm) | <1 | 1 |

| 1.0–1.9 | 3 | |

| 2.0–2.9 | 5 | |

| 3.0–3.9 | 7 | |

| >4 | 9 | |

| Morphology | Pedunculated | 1 |

| Sessile | 2 | |

| Flat | 3 | |

| Site | Left | 1 |

| Right | 2 | |

| Access | Easy | 1 |

| Difficult | 3 | |

| SMSA level | ||

| Level 1=4–5 | Predicted success rate at EMR7 | |

| Level 2=6–8 | SMSA 2=99.4% | |

| Level 3=9–12 | SMSA 3=97.8% | |

| Level 4≥12 | SMSA 4=92.9% |

EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; SMSA, Size/Morphology/Site/Access.

Lesions should only be biopsied if it is felt that there is already invasive malignancy. Otherwise, the lesion should be carefully described using a standard format, including details of its site, relationship to surrounding folds and best patient position identified. If it is likely to be endoscopically resectable, then a tattoo will not usually be necessary and runs the risk, like biopsy, of complicating future endoscopic resection.

If there are no features suspicious for submucosal invasion, then resection can be performed. In general, lesions up to 20 mm in size can be resected en bloc, which reduces the chance of incomplete resection. Lesions >20 mm in size should usually be resected using a piecemeal approach.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is an alternative to EMR; however, this method is technically challenging, with lengthy procedure times and few centres with expertise in the West. A recent Western cost-effectiveness study found that while ESD is justified for laterally spreading colorectal lesions (LSLs) at high risk of malignancy, these form a only a minority of cases, and a selective ESD approach is preferred (43 ESDs per 1000 LSLs modelled in this study).8 EMR is therefore a safe and effective treatment for most LSLs.

Principles of EMR

Preprocedural considerations

Patient selection and decision making can be complex. Some of the factors to be considered are shown in table 3.9

Table 3.

Factors to be considered prior to attempting endoscopic mucosal resection

| Patient-related factors | Polyp related factors |

| Age/life expectancy Comorbidity Drug history

Consent and patient wishes Difficulties with bowel preparation

Social circumstances, for example,

|

SMSA score Increased risk of malignancy

Difficult site (eg, appendix and diverticular segment) Endoscopic access to the lesion Previous intervention Lesions within an inflamed segment of colitis Non-lifting sign Endoscopist inexperience |

NICE, NBI International Colorectal Endoscopic; SMSA, Size/Morphology/Site/Access.

It is good practice to discuss complex EMR cases in a multidisciplinary setting. Prior to any therapeutic endoscopic procedure, it is important the patient is adequately informed of the risks (table 4) and potential therapeutic alternatives are discussed so that full consent can be given.

Table 4.

Risks of colonic EMR

| Risks of colonic EMR13, 27 | |

| Perforation | 1%–2% |

| Bleeding | |

| Immediate | Up to 11% (rarely serious and readily amenable to endoscopic haemostasis) |

| Delayed (up to 14 days after the procedure) | Up to 7% |

| Postpolypectomy syndrome | 0.07% |

| Recurrence | 10%–30% (usually easily treated during surveillance endoscopy) |

| Incomplete removal | Further endoscopic resection or an operation may be required. |

| Narrowing/stricturing | Removing large lesions (ie, ≥75% of circumference) can lead to scarring and narrowing. |

EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection.

The patient’s medical and drug history should be reviewed and incorporated into the decision-making process. Management of patients on antithrombotic agents should follow current British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG)/European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guidelines.10 It is particularly useful to review the previous colonoscopy report to ensure adequate bowel preparation is used and to anticipate difficulties with access to the lesion. For example, some lesions, or part of a lesion, may be best accessed in a retroflexed position, and in this situation, a smaller calibre endoscope may be easier to manipulate. For lesions in the left colon and rectum a shorter endoscope may be easier to manoeuvre and quicker for instrument exchange. Large polyp EMR carries greater risk and for this reason: polyps>20 mm are not usually resected at index colonoscopy unless consent, time and expertise allow.

Patients will almost always be sedated for therapeutic procedures. This does not necessarily require deep propofol sedation or general anaesthetic; however, if a prolonged or difficult resection is anticipated, this may be more appropriate.

The endoscopist should always consider a strategy for resection prior to commencing the procedure. Any therapy is best attempted with the endoscope in a neutral or ‘straight’ position, and it should be remembered that access onto a lesion may require patient position change to optimise the view. In certain situations, a transparent cap on the end of the endoscope can help to maintain views during EMR by providing tip stability and the ability to manipulate mucosal folds in difficult locations.

Careful examination of the lesion is imperative even if it has been previously described and imaged. Digital video recording is particularly helpful if available. The endoscopist should reassess and photodocument the full extent of the lesion in a systematic way with careful washing of the lesion and overview in white light to determine the Paris classification. Advanced imaging techniques such as virtual chromoendoscopy (NBI, FICE and i-SCAN), and near focus/magnification should ideally be used to assess surface morphology, vessels and pit patterns.

Dynamic injection technique

A prediction should be made as to how the tissues will respond when the lifting solution is injected. A dynamic submucosal injection technique can be used to optimise access onto the lesion when compared with a static technique.11 While fluid is injected, pierce the needle into the mucosa and gently withdraw the tip to identify the submucosal plane. Submucosal fluid generally accumulates in an area of low pressure, with the fluid usually pooling in a direction opposite to where the catheter is deflected; that is, if the needle tip is moved to the left, fluid accumulates on the right. Suction of luminal air and withdrawal of the needle during injection can also increase the prominence of the bleb. Injecting at the proximal (oral) border of the lesion usually ensures optimal views are maintained. In some cases, particularly with the resection of larger lesions, debulking distally (anal) first may be the most efficient strategy.

Snare choice

For hot EMR, choose the smallest possible snare for both en bloc or piecemeal resections. We prefer braided snares of 15–20 mm as they offer better control over larger diameter snares. A 10 mm snare can also be substituted during the same polypectomy for difficult to access areas or small residual polyp. For cold EMR, a dedicated cold snare which has a stiff outer catheter and thin filament is recommended to aid tissue capture and resection.

Diathermy settings

Microprocessor controlled electrosurgical units reduce the risk of deep mural injury during polypectomy; however, the correct settings need to be employed. Preset right colon settings should be used proximal to the splenic flexure and left colon settings for polyps that are distal.12 For resection of non-pedunculated lesions, a blended current combining both cut and coagulation is recommended (eg, Endocut Q; ERBE VIO, Tubingen, Germany).13 This differs from left-sided pedunculated or subpedunculated polyps, where a predominant coagulation current may be used, particularly if there is a large feeding vessel to reduce postpolypectomy bleeding, provided there is sufficient submucosal protection (eg, forced coagulation, ERBE VIO). It is important to note that thinner snares offer less coagulation compared with thicker snares. If snare resection is not achieved within 3 s of diathermy, carefully assess the snare position to avoid transmitting excess thermal energy to the muscle. Intraprocedural bleeding and thermal edge ablation can be addressed with snare-tip coagulation (Soft Coag 80W effect 4, ERBE VIO).14

EMR procedure

EMR should be a sequential, logical stepwise procedure (figure 1). Here we list the key principles.

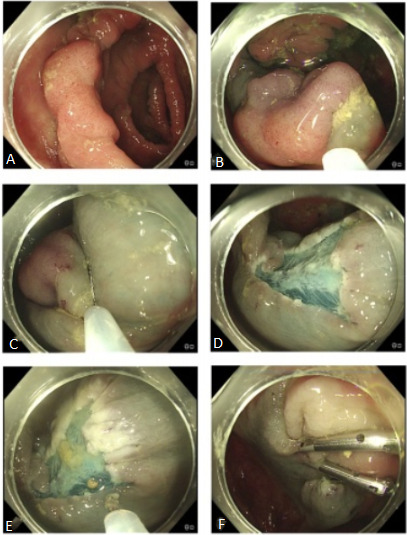

Figure 1.

Piecemeal endoscopic mucosal resection. (A) Twenty-five-millimetre mid-ascending colon Paris IIA polyp. (B) Lesion oriented to 6 o’clock and lifted with submucosal injection. (C) Stepwise resection and lift. (D) Resection defect free from visible polyp. (E) Snare tip soft coagulation 80 W applied to thermally ablate the defect edge. (F) Defect closed with clips to reduce delayed bleeding. Histology: tubular adenoma with low-grade dysplasia.

Optimise the position of the area to be resected in the 6 o’clock position (or lining up with the instrument channel of the endoscope).

Consider gravity and where fluid, polyp pieces and blood will pool as these may obscure the view; patient position change will aid this.

Choice of fluid for injection will depend on personal preference, site and morphology of the lesion. Normal saline is inexpensive and simple to use, although the submucosal cushion is only maintained for a short period. Alternatives that remain in the submucosal space for a longer time include gelofusine and hyaluronic acid. Dyes such as indigo carmine 4.5% are often incorporated to help delineate the lesion’s margins. Dilute epinephrine (1:100 000) can be added due to theoretical benefits of reduced bleeding. In general, an endoscopist and team should be familiar with a few options and stick to these rather than having very many options with which they are less familiar.

The resection is a repetitive three-step process: submucosal injection, snare resection and inspection.

The first resection should include a rim of normal mucosa to facilitate clear mucosal edges. Sequential resections should then aim to overlap so that no islands of polyp tissue remain.

At completion of the resection, time should be taken to thoroughly inspect the whole defect for areas of residual polyp tissue, deep mural injury or vessels at risk of bleeding. Any residual tissue should ideally be snare resected. Thermal ablation can be used for very tiny pieces; however, this may not completely eradicate dysplastic tissue.

Consideration of defect closure. The pros and cons of doing so should be weighed up on a case-by-case basis. Consider clipping a defect in lesions where bleeding appears to be more likely, for example, where there has been significant intraprocedural bleeding: in patients who need to restart anticoagulants; in those who have a lesion that has been difficult to access, for example, where there is a difficult insertion; and in patients with significant comorbidity in whom a significant bleed would be catastrophic.

In a recent randomised trial comparing closing the resection defect with clips to not closing it among 918 patients undergoing EMR of large (≥20 mm) polyps, clip closure reduced the risk of delayed bleeding from 7.1% to 3.5% (p=0.015).13 The reduced bleeding rate was only seen for polyps in the right colon.

Using the stepwise technique described earlier, very large and even circumferential or almost circumferential lesions can be resected using EMR. Consideration should be given to alternative techniques in very rare cases. For example, in very young patients who have very large lesions, as the risk of recurrence is greater the bigger a polyp gets, this may result in a young person having very many years of follow-up with resection of recurrent polyp unless the index procedure is performed fastidiously. Site checks and follow-up to ensure complete resection should follow the BSG postpolypectomy surveillance guidelines.15

Limits of EMR

Lesions with submucosal invasion are unsuitable for EMR and should ideally be removed en bloc with ESD or surgery. In a prospective study of over 2000 patients with non-pedunculated polyps of >20 mm referred for EMR, the key risk factors for submucosal invasive cancer (SMIC) were defined.16 The strongest predictor of SMIC was Kudo pit pattern V (OR 14.2, p<0.001). A depressed (IIc) component to the lesion was also an independent predictor of SMIC. Lesions with a granular surface had a very low cancer risk. In lesions without overt endoscopic evidence of cancer (Kudo V and depressed IIc morphology), recto-sigmoid location, increasing size, non-granular surface, and combined Paris classification and surface morphology stratified the risk of covert cancer. Distally located Is and IIa+Is non-granular lesions had a high risk of SMIC, whereas proximally located Is or IIa granular lesions have a very low risk.16

Among Paris IIa+Is lesions, the risk of submucosal invasion is most frequently below the Is component. In such cases, resection of the dominant nodule or Is component should take place first if piecemeal excision is planned, and this specimen should be retrieved separately for histopathological analysis, if possible.17

Other features that might suggest submucosal invasion include converging mucosal folds, hardness felt when probing the lesion with biopsy forceps, fixation to the underlying bowel wall and non-lifting. Non-lifting is evident when submucosal injection fails to elevate the lesion, but lifts the surrounding mucosa and is strongly associated with submucosal invasion.18 Previous biopsy sampling or submucosal injection may, however, cause fibrosis, leading to a false - non-lifting sign.

Adjuncts to and new methods of EMR

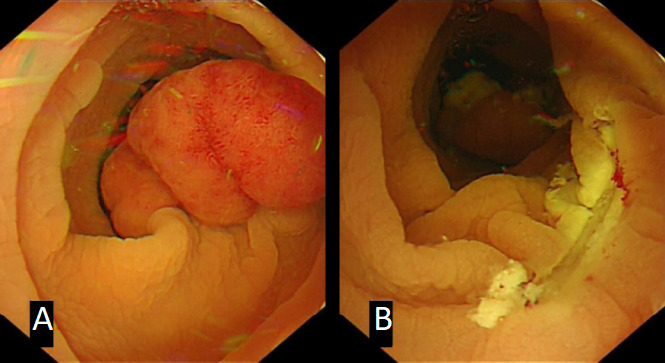

In some challenging situations, EMR may still be possible but with adaptations in technique. Lesions that have been previously biopsied or are recurrent polyps are often scarred and are difficult to lift. Underwater EMR (U-EMR) is a relatively newly described technique where the lumen of the colon is filled with water or saline and gas is suctioned. After water immersion, the adenoma-bearing mucosa and submucosa elevates or ‘floats’ away from the deeper muscularis propria, which remains circular.19 The polyp tissue is then hot or cold snare resected (figure 2). Cold snare resection is also helpful for small, very flat lesions which can then be resected en bloc; cautery artefact is avoided, allowing for a more accurate pathological assessment.

Figure 2.

Underwater endoscopic mucosal resection. (A) Twenty-millimetre sigmoid colon Paris Isp (subpedunculated) polyp, (B) resected underwater with hot snare.

Cold piecemeal EMR is a useful technique particularly for serrated lesions. These are often flat lesions occurring frequently in the right colon, where the wall is thinner and easily damaged by diathermy during polypectomy, carrying a risk of delayed bleeding, perforation and postpolypectomy syndrome. These lesions can be safely resected using conservative submucosal injection and a thin cold snare, taking care to cut normal mucosa at the polyp edge to secure clear lateral margins to achieve radical resection of these often very subtle lesions.20

Lesions involving the appendiceal orifice, ileocaecal valve and dentate line pose a challenge but still may be resected using EMR. Adjustments to technique may be required:

Appendiceal orifice: if <50% is involved, lift the lesion out of the orifice to ensure the edge of the dysplastic tissue is free of the appendix. Use a small stiff snare. Consider using cold or U-EMR (no diathermy) as the caecum has the highest risk of perforation

Ileocaecal valve (ICV): often a challenging approach requiring retroflexion or a transparent cap to access the lesion if arising from the ileal mucosa. These lesions have a high risk of recurrence.

Dentate line: add a local anaesthetic (1%–2% lidocaine) to the lifting solution and consider prophylactic antibiotics.

Recurrence

The most often cited drawback of colonic EMR is the relatively high rate of adenoma recurrence (10%–30%) at follow-up.13 Risk factors for residual or recurrent adenoma after EMR include lesion size of >40 mm, piecemeal resection, bleeding during the procedure and high-grade dysplasia in the resection specimen.21

In a prospective study of 390 patients with large laterally spreading colonic lesions (>20 mm), thermal ablation of the post-EMR defect margin with soft coagulation using the snare tip resulted in a fourfold reduction in adenoma recurrence rates at 6 months,2 suggesting that invisible residual adenoma at the resection margin may account for a significant proportion of recurrences. The relative risk of recurrence in the thermal ablation group was 0.25 compared with the control group (95% CI 0.13 to 0.48). In a prior small pilot study, argon plasma coagulation (APC) was used to ablate the lesion margin after complete snare excision and also demonstrated a reduction in adenomatous recurrence.22

Although most local recurrences can be treated endoscopically, additional endoscopic resection can be technically challenging due to fibrosis at the original resection site and non-lifting with submucosal fluid injection. ESD for such recurrences is technically difficult and typically a lengthy procedure.23

Several rescue endoscopic techniques have been described, although prospective long-term data are limited. In a retrospective study to assess the feasibility of salvage U-EMR for the treatment of recurrent adenoma after piecemeal EMR of colorectal LSLs of >20 mm, the en bloc resection rate and complete resection rate were significantly higher in the U-EMR group versus conventional EMR (88.9% vs 31.8%, p<0.001).24

Endoscopic mucosal ablation is a technique described to complement the eradication of recurrent fibrotic colon polyps and appears to be safe and easily applicable.25 It involves using high-power APC destruction, preceded by injection of a submucosal fluid cushion to protect the muscle layer and to augment further piecemeal EMR and polyp eradication.

In one study, the combined use of endoscopic knives and snares, known as knife-assisted snare resection (KAR) was associated with an overall cure rate for complex scarred colonic polyps of 90%.26 The KAR procedure begins with submucosal injection followed by a mucosal incision made outside the scarred area and slowly extended to create a circumferential groove around the lesion in which to engage a snare. Depending on the extent of submucosal dissection and the size of the lesion, snare resection in a piecemeal or en bloc fashion can then be performed.

Finally, endoscopic full-thickness resection with an over-the-scope device offers the option of complete resection for difficult-to-treat recurrent or residual colorectal neoplasia after previous EMR, but prospective data are lacking.

Conclusion

The vast majority of colorectal lesions can be resected using a straightforward EMR technique with a low and acceptable rate of adverse events. Larger lesions suitable for EMR should be referred to endoscopists who have a high-volume practice to ensure familiarity with the tools and techniques and to have the experience required to manage complications and to reduce the risk of recurrence. All lesions should be carefully inspected and biopsies avoided unless invasive malignancy is suspected. Although EMR carries a risk of recurrent adenoma, this can be mitigated with thorough assessment, precise technique and careful inspection of the polypectomy defect. Recurrence can be successfully managed endoscopically in most cases. Given the effectiveness of wide-field EMR for benign lesions and the infrequency of low-risk SMIC lesions, a universal ESD strategy in the colorectum is unjustified.8

flgastro-2019-101357supp001.m4v (313.3MB, m4v)

Footnotes

Twitter: @SiwanTG, @DrMattChoy, @AngadDhillon

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it published Online First. A supplementary file has been added.

Contributors: ST-G: manuscript planning, writing, review, responsible for overall content. MC: manuscript editing and video editing. ASD: manuscript writing, editing and submission.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1. Fogt F, Zimmerman RL, Ross HM, et al. Identification of lymphatic vessels in malignant, adenomatous and normal colonic mucosa using the novel immunostain D2-40. Oncol Rep 2004;11:47–50. 10.3892/or.11.1.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Klein A, Tate DJ, Jayasekeran V, et al. Thermal ablation of mucosal defect margins reduces adenoma recurrence after colonic endoscopic mucosal resection. Gastroenterology 2019;156:604–13. 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rex DK, Dekker E. How we resect colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc 2019;89:449–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gallegos-Orozco JF, Gurudu SR. Complex colon polypectomy. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;6:375–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Neilson LJ, Rutter MD, Saunders BP, et al. Assessment and management of the malignant colorectal polyp. Frontline Gastroenterol 2015;6:117–26. 10.1136/flgastro-2015-100565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gupta S, Miskovic D, Bhandari P, et al. A novel method for determining the difficulty of colonoscopic polypectomy. Frontline Gastroenterol 2013;4:244–8. 10.1136/flgastro-2013-100331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sidhu M, Tate DJ, Desomer L, et al. The size, morphology, site, and access score predicts critical outcomes of endoscopic mucosal resection in the colon. Endoscopy 2018;50): :684–92. 10.1055/s-0043-124081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bahin FF, Heitman SJ, Bourke MJ. Wide-Field endoscopic mucosal resection versus endoscopic submucosal dissection for laterally spreading colorectal lesions: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Gut 2019;68:1130. 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rutter MD, Chattree A, Barbour JA, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology/Association of Coloproctologists of great britain and ireland guidelines for the management of large non-pedunculated colorectal polyps. Gut 2015;64:1847–73. 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Veitch AM, Vanbiervliet G, Gershlick AH, et al. Endoscopy in patients on antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy, including direct oral anticoagulants: British Society of gastroenterology (BSG) and European Society of gastrointestinal endoscopy (ESGE) guidelines. Gut 2016;65:374–89. 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-311110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Soetikno R, Kaltenbach T. Dynamic submucosal injection technique. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2010;20:497–502. 10.1016/j.giec.2010.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Eickhoff A, et al. Electrosurgical pocket guide for Gi interventions 2016, Erbe Elektromedizin GmbH:42–9.

- 13. Klein A, Bourke MJ. How to perform high-quality endoscopic mucosal resection during colonoscopy. Gastroenterology 2017;152:466–71. 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.12.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fahrtash-Bahin F, Holt BA, Jayasekeran V, et al. Snare tip soft coagulation achieves effective and safe endoscopic hemostasis during wide-field endoscopic resection of large colonic lesions (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc 2013;78:158–63. 10.1016/j.gie.2013.02.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rutter MD, East J, Rees CJ, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology/Association of Coloproctology of great britain and Ireland/Public health England post-polypectomy and post-colorectal cancer resection surveillance guidelines. Gut 2020;69:201–23. 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Burgess NG, Hourigan LF, Zanati SA, et al. Risk Stratification for Covert Invasive Cancer Among Patients Referred for Colonic Endoscopic Mucosal Resection: A Large Multicenter Cohort. Gastroenterology 2017;153:732–42. 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Holt BA, Bourke MJ. Wide field endoscopic resection for advanced colonic mucosal neoplasia: current status and future directions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10:969–79. 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Uno Y, Munakata A. The non-lifting sign of invasive colon cancer. Gastrointest Endosc 1994;40:485–9. 10.1016/S0016-5107(94)70216-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Binmoeller KF, Weilert F, Shah J, et al. "Underwater" EMR without submucosal injection for large sessile colorectal polyps (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2012;75:1086–91. 10.1016/j.gie.2011.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rameshshanker R, Tsiamoulos Z, Latchford A, et al. Resection of large sessile serrated polyps by cold piecemeal endoscopic mucosal resection: serrated cold Piecemeal endoscopic mucosal resection (scope). Endoscopy 2018;50:E165–7. 10.1055/a-0599-0346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tate DJ, Desomer L, Klein A, et al. Adenoma recurrence after piecemeal colonic EMR is predictable: the Sydney EMR recurrence tool. Gastrointest Endosc 2017;85:647–56. 10.1016/j.gie.2016.11.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brooker JC, Saunders BP, Shah SG, et al. Treatment with argon plasma coagulation reduces recurrence after piecemeal resection of large sessile colonic polyps: a randomized trial and recommendations. Gastrointest Endosc 2002;55:371–5. 10.1067/mge.2002.121597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shichijo S, Takeuchi Y, Uedo N, et al. Management of local recurrence after endoscopic resection of neoplastic colonic polyps. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2018;10:378–82. 10.4253/wjge.v10.i12.378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kim HG, Thosani N, Banerjee S, et al. Underwater endoscopic mucosal resection for recurrences after previous piecemeal resection of colorectal polyps (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2014;80:1094–102. 10.1016/j.gie.2014.05.318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tsiamoulos ZP, Bourikas LA, Saunders BP. Endoscopic mucosal ablation: a new argon plasma coagulation/injection technique to assist complete resection of recurrent, fibrotic colon polyps (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 2012;75:400–4. 10.1016/j.gie.2011.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chedgy FJQ, Bhattacharyya R, Kandiah K, et al. Knife-assisted SNARE resection: a novel technique for resection of scarred polyps in the colon. Endoscopy 2016;48:277–80. 10.1055/s-0035-1569647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cha JM, Lim KS, Lee SH, et al. Clinical outcomes and risk factors of post-polypectomy coagulation syndrome: a multicenter, retrospective, case-control study. Endoscopy 2013;45:202–7. 10.1055/s-0032-1326104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

flgastro-2019-101357supp001.m4v (313.3MB, m4v)