Abstract

Introduction

HIV programmes in sub-Saharan Africa are well funded but programmes for diabetes and hypertension are weak with only a small proportion of patients in regular care. Healthcare provision is organised from stand-alone clinics. In this cluster randomised trial, we are evaluating a concept of integrated care for people with HIV infection, diabetes or hypertension from a single point of care.

Methods and analysis

32 primary care health facilities in Dar es Salaam and Kampala regions were randomised to either integrated or standard vertical care. In the integrated care arm, services are organised from a single clinic where patients with either HIV infection, diabetes or hypertension are managed by the same clinical and counselling teams. They use the same pharmacy and laboratory and have the same style of patient records. Standard care involves separate pathways, that is, separate clinics, waiting and counselling areas, a separate pharmacy and separate medical records. The trial has two primary endpoints: retention in care of people with hypertension or diabetes and plasma viral load suppression. Recruitment is expected to take 6 months and follow-up is for 12 months. With 100 participants enrolled in each facility with diabetes or hypertension, the trial will provide 90% power to detect an absolute difference in retention of 15% between the study arms (at the 5% two-sided significance level). If 100 participants with HIV infection are also enrolled in each facility, we will have 90% power to show non-inferiority in virological suppression to a delta=10% margin (ie, that the upper limit of the one-sided 95% CI of the difference between the two arms will not exceed 10%). To allow for lost to follow-up, the trial will enrol over 220 persons per facility. This is the only trial of its kind evaluating the concept of a single integrated clinic for chronic conditions in Africa.

Ethics and dissemination

The protocol has been approved by ethics committee of The AIDS Support Organisation, National Institute of Medical Research and the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. Dissemination of findings will be done through journal publications and meetings involving study participants, healthcare providers and other stakeholders.

Trial registration number

Keywords: public health, diabetes & endocrinology, hypertension, HIV & AIDS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the largest trial of its kind with replication in over 30 health facilities and 2 countries.

It was designed, implemented and is being monitored in partnership with patient representatives, healthcare providers, policy-makers and other stakeholders.

The trial is measuring objective markers of effectiveness and is multidisciplinary.

The trial has a relatively short follow-up of 12 months and cannot estimate effect against mortality or other longer-term outcomes.

The trial cannot be blinded—both healthcare providers and patients know the intervention being delivered at each health facility.

Introduction

In sub-Saharan Africa, over 2 million deaths a year are attributed to hypertension and diabetes annually and this number is rising rapidly.1–3 Health service provision for these conditions and for HIV, which also requires chronic lifelong care, is organised separately from vertical stand-alone clinics across sub-Saharan Africa. This duplicates resources and is particularly difficult to access for the increasing number of people who have multiple conditions.4

There is little or no evidence that integration of primary care health services improves the health status of people in low-income or middle-income countries.5 6 Studies from sub-Saharan Africa evaluating complete integration—that is, a single clinic that can manage multiple chronic conditions—for people living with any one or more chronic conditions are particularly scarce.7 We found one study from a Médecins Sans Frontières—supported health facility serving an informal settlement in Nairobi, Kenya. Patients with either HIV infection or non-communicable conditions (mostly hypertension) were seen together for basic monitoring and provision of drugs. However, the study size was just 1432 patients, it was retrospective and done at a single site.8 Limited evidence is also available from South Africa,9 10 but the health system here is much stronger and findings difficult to generalise to other parts of sub-Saharan Africa.

Given the limited evidence, we first conducted a large preliminary study to evaluate the acceptability and feasibility of integration of services for HIV, diabetes and hypertension in Tanzania and Uganda. We enrolled 2273 participants in a cohort study to receive integrated care from 10 health facilities and followed the cohort for between 6 and 12 months. Retention was high and analysis suggested that the integrated model could be highly cost-effective.11 However, the study did not have a comparative group. Here, we present the plans for a large pragmatic cluster-randomised trial that follows the initial study and is designed to inform policy.

Methods

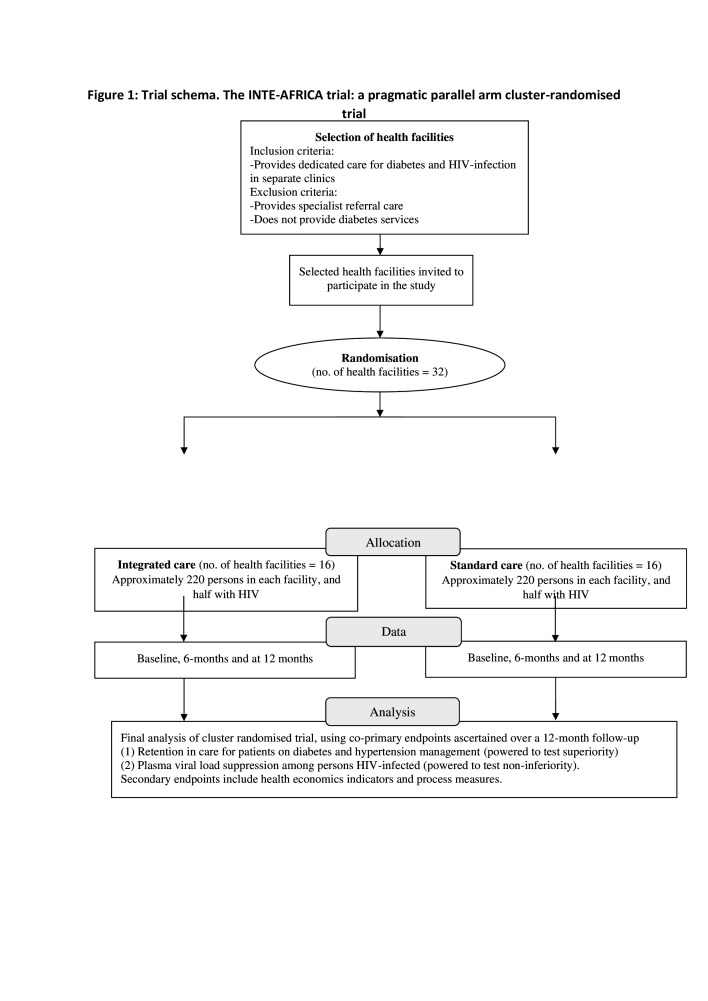

The INTE-AFRICA trial is a pragmatic parallel arm cluster randomised-controlled trial, comparing integrated health services for HIV infection diabetes and hypertension with a standard care approach (ie, stand-alone care) in Tanzania and in Uganda. Health facilities have been randomised to either integrated care or current standard care. Enrolment began on 30 June 2020 and finished in April 2021. Follow-up will continue for 12 months. Figure 1 shows the trial schema. Procedures for enrolment and the management of participants are identical in the two arms. The research team sees the participants at baseline, 6 months and 12 months and each time they self-refer (eg, attend because they are sick) for data collection.

Figure 1.

Trial schema. The INTE-AFRICA trial: a pragmatic parallel arm cluster randomised trial.

The integrated care arm comprises:

A single clinic where patients with either HIV infection, diabetes or hypertension are managed. Patients can have one or more of these conditions.

There is one area where patients register and wait.

They are managed by the same clinicians, nurses, counsellors and other staff.

There is one pharmacy where the dispensing of medicines is integrated.

Patient records are the same for all patients.

Laboratory samples are managed and tested in the same laboratory service where possible.

Patients usually attend health facilities 3-monthly for routine appointments.

The standard vertical care provided in Tanzania and Uganda is the control arm and comprises:

Vertical care in separate clinics for HIV infection, diabetes and hypertension, (ie, standard current practice).

HIV services have separate waiting areas and separate consultation rooms, a separate dedicated pharmacy, separate medical records and laboratory samples are managed separately from those for diabetes and hypertension services.

Patients with HIV usually attend for routine appointments 3-monthly but those with diabetes or hypertension attend their clinics monthly.

Diabetes and hypertension services continue as they are. Patients with these conditions are usually managed in separate clinics and they use the general hospital pharmacy. These patients will usually attend health facilities monthly for routine appointments.

Thousands of patients are receiving care for HIV infection, diabetes and hypertension at each health facility but for the sample size requirements, we only need to enrol a subset of participants at each facility. Therefore, in those facilities randomised to integration, stand-alone ‘integrated clinics’ have been set up. In some facilities, these run on a day when the separate standalone HIV, diabetes and hypertension clinics are not operating. In others, it is run in separate rooms away from the main vertical standalone clinics. In the standard care, participants are enrolled into the research study and continue to receive standard care.

We have attempted to bring clinical staff to a common level of understanding of the management of HIV infection, diabetes and hypertension in both the arms of the trial. Thus, government clinical and counselling staff have had classroom training on the management of HIV infection, diabetes and hypertension for 1–2 days. Both healthcare and all research staff have also received training on the protocol, also for 1 day.

Thereafter, staff received on-the-job training for a period of 1 month. Within the integrated care clinics, staff specialised in one condition supported staff new to managing the other two conditions. For example, the doctors who have traditionally managed patients with HIV infection periodically observe staff from diabetes and hypertension clinics treating HIV-infected patients. They provide constructive feedback and support.

Staff in the vertical standalone clinics also receive on-the-job training. Those managing the single conditions are observed at least once every week for 4 weeks. They receive constructive feedback and support.

Patient and public involvement

How was the development of the research question and outcome measures informed by patients’ priorities, experience and preferences?

We conducted a large pilot study. Integrated care clinics for patients living with HIV infection, diabetes or hypertension were set up in 10 health facilities in Tanzania and Uganda. Over 2000 patients with one or more of these chronic conditions were followed up for 6–12 months. Acceptance was high and retention in care at the study end exceeded 80%. Integrated care was particularly welcomed by patients who had more than one condition and who would otherwise visit the health facility multiple times.

Before the pilot study started, we set up steering committees in both Tanzania and Uganda, which comprised researchers, policy-makers and had patient representatives. We held investigator meetings involving all of the partners. These included a patient representative and at the last meeting, held in December 2019 in Uganda (prior to the start of this trial), one of the patient representatives gave a talk on why integrated management was important to him and other patients.

How did you involve patients in the design of this study?

Patient representatives attended our planning meetings and contributed to the design of the study and other aspects of the research, such as its implementation.

Are patients involved in the recruitment to and conduct of the study?

Patient representatives remain on the steering committees and are invited to the large investigator meetings. The steering committees meet every 3–6 months. At these meetings, patient representatives provide input into the recruitment and conduct of the study.

How will the results be disseminated to study participants?

This will be done through information leaflets, written for study participants. We will distribute these to all study participants. We will also present the findings to the steering committees, which are attended by patient representatives, and publish the findings in a journal.

For randomised controlled trials, was the burden of the intervention assessed by patients themselves?

The patients were fully informed about the intervention. The intervention was designed to reduce the burden of visits for patients.

Governance and oversight

As mentioned above, each partner country has a steering committee. There is also a single international steering committee, which is chaired by and has majority participation of independent researchers, and an independent data and safety monitoring committee. The composition and charter of the independent data and safety monitoring committee is available on request.

The trial Sponsor is the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (lstmgov@lstmed.ac.uk).

Study design and setting

INTE-AFRICA comprises 32 health facilities that have been randomised in the 2 countries—16 to integrated care and 16 to the standard care (control arm). Seventeen facilities are in Uganda and 15 in Tanzania. Health policies in both countries support integrated management for chronic conditions but clinical practice involves vertical healthcare delivery for HIV, diabetes and hypertension, with clinics for these conditions typically run on different days of the week in most health facilities.12 As in most of sub-Saharan Africa, shortages in medicines for diabetes and hypertension are common.13–15 HIV services are organised in separate areas of the health facilities, with separate clinical and counselling staff, separate medicines procurement and separate medical records.16

The trial is being done in close to normal health service conditions, with government healthcare staff managing patients.17 Thus, healthcare provision, including setting up of the integrated care clinics, has been done by health services, with limited support from the research team. The research team organised basic training in the management of patients with chronic conditions, as mentioned above, and supported health facilities to strengthen the provision of medicines supply for hypertension and diabetes.18 In Uganda, in a few health facilities in the region, groups of participants had formed ‘clubs’ whereby each patient contributes money into a single fund and the Club uses it to purchase drugs when government supplies are limited. The research team supported the health facility managers to kick-start these Clubs in each facility participating in the trial for the purchase of medicines for diabetes and hypertension. The health facility managers gathered patients together to discuss procedures, the setting up of a common bank account, and agreeing a drug procurement and dispensing system. Each patient contributed about £5 per month. The bulk purchasing led to a 50%–60% reduction in drug costs compared with pharmacy prices. The drugs were delivered to the facility pharmacy, which distributed them to participants. This was done by the pharmacist and overseen by one of the patient volunteers. To support this effort, the research team provided buffer drug supplies for 2 months when a facility ran short to enable the patients’ central fund to grow and after this period, the club was self-sustaining.

In Tanzania, some patients are on insurance schemes and so had a reliable medicines supply. Others were expected to pay for their medicines if they could afford this. The health facilities have an established protocol for evaluating patients who have no insurance and are not able to pay. The project provided a buffer to the facilities for the few patients that are not able to purchase the drugs.

Research data collection is minimal and done mostly by trained researchers while patients wait for consultations. For our coprimary endpoint of plasma viral load suppression, samples are taken by healthcare staff and tested in government laboratories. Where needed, the research programme pays for the tests and the data are used by both the research team and the healthcare teams for patient management.

INTE-AFRICA is being conducted in medium-large sized health facilities that focus on offering ambulatory care. All of the facilities are run by physicians or medical officers, supported by part-qualified physicians (clinical officers or assistant medical officers). The facilities are located in largely urban settings in Dar es Salaam in Tanzania and Kampala region in Uganda. They were selected according to the following criteria:

Inclusion criteria

Provides dedicated care for diabetes and HIV infection in separate clinics.

Has a minimum of n=100 patients in care with diabetes.

Exclusion criteria

Provide specialist referral care.

Does not provide diabetes services.

We chose to enrol facilities that have dedicated separate clinics for HIV infection and diabetes. We have not specified hypertension in our inclusion criteria. In the health facilities where we are working, hypertension clinics are sometimes standalone and sometimes integrated with diabetes clinics, depending on the volume of patients. Since these health facilities currently provide care separately for HIV infection and diabetes/hypertension, integration will involve the greatest change for the health facility and therefore the greatest advance in knowledge. Diabetes care is fragmented and screening to identify people with diabetes is limited. We had a minimum of 100 people with diabetes as a requirement since some clinics manage few patients with diabetes.

We are not intervening in large referral hospitals that offer specialised care. They act as referral centres. We are also not enrolling at smaller health facilities that do not offer diabetes services as such facilities could not act as effective control clinics for vertical care.

Government health facilities fulfilling these criteria are large health centres (health centre IVs and a few health centre IIIs) in Uganda. In Tanzania, the comparable centres are the smaller district and municipal hospitals, and the larger health centres.

In both Tanzania and Uganda, the not-for-profit non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are responsible for a substantial amount of healthcare delivery, which is organised in accordance with national guidelines. They are also major players in training and strengthening healthcare provision in government health facilities. We are recruiting a small number of NGO-run health facilities that are similar to the government health facilities providing dedicated primary healthcare.

We chose the regions, based on ease of access for the research team. We then visited the large facilities that fulfilled the criteria above. We omitted a small number that were inaccessible.

In the selection of study participants, we kept the criteria minimal so as to maximise generalisability of findings.

Inclusion criteria

Adult, 18 years or older.

Confirmed HIV infection, diabetes or hypertension.

Living within the catchment population of the health facility.

Likely to remain in the catchment population for 6 months.

Willing to provide written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Sick, requiring immediate hospital care.

We know that at each of the study health facilities, the numbers of patients receiving diabetes care or those with multiple conditions are limited and so patients with these conditions are being enrolled consecutively.

The health facilities have a high volume of patients with HIV infection and with hypertension. Some health facilities do not offer appointments and so there is no way of knowing who will present the next day. In larger health facilities, appointments are given out in 3–4 blocks during the day so as to spread the patient load.

Selection of patients using simple random sampling minimises bias but is difficult to achieve. Therefore, we are conducting systematic sampling to enrol patients with HIV infection or hypertension—that is taking every 5th or 10th patient consecutively in order of their attendance at the health facility, depending on the patient load. If the study team are late arriving at the facility, or if a patient refuses to join the study, then they maintain the systematic sequence and start at the next sequence number (ie, offer enrolment to the next 5th or next 10th patient).

In the HIV or hypertension clinics, patients’ details are entered onto a clinic register when they arrive and research staff use the register to determine the first patient for enrolment, second patient and so on.

Sampled patients are then invited to participate in the trial following written informed consent.

Randomisation

The study is cluster randomised since the intervention is delivered at a clinic level.

There is considerable variation in infrastructure and service provision between health facilities. Therefore, to ensure balance between the intervention and control arms, we stratified the randomisation. The strata comprised:

District hospitals or large health centres.

Health centres or large dispensaries.

Not-for-profit health facilities.

Within each stratum, we randomised facilities in a 1:1 ratio to either integrated care or standard care using a permuted block randomisation method generated by SAS PROC PLAN (V 9.4).

We considered changing the mode of care entirely for all patients at each clinic to either integrated or vertical care, depending on the randomisation. This would have replicated real life healthcare delivery. However, it would have represented a major change for the health services, without the evidence to support such a move. It would also have meant that those people who were currently receiving vertical care and did not wish to change, would not have had the choice to continue. Therefore, although randomised by clinic, we are enrolling only a small proportion of the very many patients attending health services at the clinic. In the clinics randomised to provide integrated care, they are the sole point of integration in that facility for HIV infection, diabetes and hypertension as integrated services are not provided anywhere else in either country.

Primary endpoints

The study has two coprimary endpoints, which will be ascertained over a 12-month follow-up:

Retention in care for patients on diabetes and hypertension management. This is measured as the proportion of people alive and in care at 12 months of follow-up.

Plasma viral load suppression among persons HIV infected. This is defined as plasma viral load less than 1000 copies per mL.

We will define a participant as being retained in care if he/she has attended clinic for their routine 6-month assessment or anytime after that and in the subsequent 6 months (ie, up to month 12), that he/she has not been declared lost to follow-up, has not withdrawn and has not died.

Participants who have transferred away for their care will be contacted by phone. In many cases, this will be because of referral for specialist care. If they are still in care in the places that they transferred out to, then they will be assumed to be retained for the purposes of the primary analysis.

Viral suppression will be defined as a viral load of <1000 copies per mL (or reported as undetectable viral load). Any viral load measurements taken at or after 6 months after enrolment in the trial will be used in this endpoint analysis.

Rationale

Retention in care is fundamental to disease control and has been very low for people with diabetes or hypertension in African settings, even where healthcare and medicines are provided for free. It is also a common indicator to both conditions.

We considered blood pressure and glycaemia control as primary endpoints but decided on retention as that is the immediate aim of our intervention. Once African health services can achieve good retention, the next stage of the research will be to assess impact on clinical indicators. At present, there are few reliable background data from Africa on blood pressure and glycaemia control achieved by populations able to access treatments. However, in high-income countries, only about one in four persons with known hypertension and one in two persons with known diabetes achieve adequate blood pressure and glycaemia control, respectively, and control is poorer in low-resource settings.19–22

We also considered a disease-based composite outcome such as either a stroke, myocardial infarction, or all cause-mortality, but this would need many years of follow-up. Also, given the poor retention in care, measuring disease incidence is fraught with bias. For these reasons, we chose retention as one of the primary endpoints.

The trial will also test whether there is an adverse effect of integrated services on HIV outcomes. In other words, does integration lead to poorer HIV viral suppression as compared with standard vertical care? To answer this question, HIV viral load was selected as a coprimary endpoint.

Secondary endpoints will include control of blood pressure and glycaemia, cost of illness and healthcare, incidence of clinical events including hospital admissions and deaths and plasma viral load >100 copies per mL. Definitions of the control of blood pressure will include achieving a blood pressure <140/90 mm Hg and of diabetes as achieving fasting blood glucose <7 mmol/L. The indicators will also be analysed on a continuum.

Although the study has two coprimary outcomes, they are being measured in different populations, one among people with hypertension or diabetes and the other in people with HIV infection. The plasma viral load is also a safety outcome in that we wish test whether integration could do harm to outcomes of people with HIV infection. Therefore, we will not adjust the final analyses for multiplicity.

Sample size considerations

Retention in care endpoint

We assumed that with the training and improved procedures, retention in care for persons with diabetes and hypertension would improve under current standard care—probably to a figure around 60%–70%. As a comparison, for HIV infection, this figure was around 70%–80% prior to about 2006 and is generally around 90% today.23

We hypothesised that in the intervention arm, integration would lead to further improved retention rates compared with the standard vertical care for diabetes and hypertension. Thus, this endpoint was powered on an assumption of superiority.

The sample size calculation must take clustering at health facility into account (ie, the variation between health facilities as well as variation between patients). We have done this for different values of the intraclass correlation coefficient. This is a measure of the variation between health facilities, which we can minimise between arms by stratification. In many trials, the intraclass correlation coefficient is assumed to be 0.05 but we were conservative in accepting a higher level of variation of 0.06.24 25

The calculations show that for hypertension and diabetes, if the retention in the standard vertical care arm is 60% at 12 months, then 32 facilities (16 randomised to integration and 16 to standard vertical care), with 100 patients studied in each facility, will provide 90% power to detect an absolute difference of 15% between the two study arms (ie, a retention of 60% vs 75%, respectively, in the standard care and intervention arms) (table 1). If the variation between health facilities turns out to be higher (ie, intraclass coefficient is 0.07, power will still exceed 80%). If the retention rate in the control arm is 70%, then power to detect differences will be even higher.

Table 1.

Total number of facilities needed in both arms to demonstrate absolute differences of between 10% and 20% for different values of variation between health facilities (intraclass coefficient of variation) and of numbers of patients needed in each facility

| Intraclass coefficient of variation | No of patients per facility | Proportion retained in care in the integrated care arm | ||

| 70% | 75% | 80% | ||

| 0.05 | 50 | 74 | 32 | 18 |

| 0.06 | 50 | 84 | 36 | 20 |

| 0.07 | 50 | 94 | 40 | 22 |

| 0.05 | 100 | 64 | 28 | 16 |

| 0.06 | 100 | 74 | 32 | 18 |

| 0.07 | 100 | 86 | 36 | 20 |

| 0.05 | 200 | 60 | 26 | 14 |

| 0.06 | 200 | 70 | 30 | 16 |

| 0.07 | 200 | 80 | 34 | 20 |

The calculations assume 90% power and a two-sided significance level of 5%.

We will enrol 110 patients in each of the 32 facilities to allow for a 10% refusal rate. This refusal rate is conservative as in previous large studies in these settings, our refusal rate has been close to zero.26 The group of 110 patients in each facility will be a mix of persons with either diabetes or hypertension or both conditions. The total number of patients within this randomised evaluation will be 3520.

HIV plasma viral load endpoint

The sample size for the HIV component is calculated to show non-inferiority between the integration and the standard vertical care arms. We will enrol the same number of persons with HIV infection (3520 comprising 110 patients in each of 32 facilities) as the number with hypertension or diabetes in the cluster randomised trial.

The numbers of HIV-infected people with known diabetes, hypertension or both is likely to be small as testing is limited across Africa. We will enrol all patients with known multimorbidity to add to the 3520 HIV-infected persons and 3520 with diabetes or hypertension.

In terms of virological suppression, if we assume that this is 85% at 12 months in the standard care arm, we will have 90% power to show non-inferiority between the two arms to a delta=10% margin (ie, that the upper limit of the one-sided 95% CI of the difference between the standard care and intervention arms will not exceed 10%). This also assumes an intraclass coefficient of variation of 0.06 and one-sided 95% CI.

Health economics endpoints

A substudy on costs is nested in the trial. Its aim is to provide evidence on the costs associated with accessing care for study participants and the costs of delivering care from the health providers perspective.

The economic evaluation will be based on the clinical and operational outcome parameters to define the economic effectiveness outcomes. The primary outcomes will be the incremental cost per additional person retained in the programme and the incremental cost per additional person virologically suppressed. Other outcomes will be the healthcare cost per patient category per year in integrated care and standard care, the average healthcare costs per additional patient treated and the change in the average healthcare costs/societal cost per additional patient with a controlled condition.

Given that costs and benefits of integrated care services may extend beyond the follow-up period and that these chronic conditions have lifelong consequences, we will construct an individual-based microsimulation model to estimate the long-term and lifelong cost-effectiveness of different methods of care for patients with different conditions and explore the cost-effectiveness of future scale up of these healthcare approaches.

Statistical analysis

The primary indicators will be compared between the intervention arm and standard care, while controlling for possible confounders, defined a priori. General estimating equation models will be used for the analysis to take account of clustering of data within health facilities.

The primary measure of effectiveness for the primary outcomes will be absolute risk differences and risk ratios. Time to event analysis—that is, time to loss from care—will also be conducted. We will not adjust for multiple comparisons. Although we have two coprimary endpoints, they are in different populations.

An intention-to-treat analysis strategy will be used for the primary analysis. Every effort will be made to minimise missing outcome data at each visit. Sensitivity analyses will be conducted to assess the robustness of the missing data assumption made in the primary analysis. Detailed statistical analyses will be described in the statistical analysis plan.

Process evaluation

Concurrent process evaluation is being done alongside the implementation of INTE-AFRICA to understand the context, description of the intervention and its causal assumptions, implementation, mechanisms of impact and outcomes and document stakeholders experiences, attitudes and practices during implementation, and to understand the impact of structural and contextual factors (macro/meso/micro) on implementation.27 This is described elsewhere.4

Data management

The study is run in accordance with good clinical practice. This involves regular monitoring of procedures and checking of data collected. A custom electronic database has been designed for the trial. Staff received training on the electronic database as well as on how to report issues and make suggestions. Trial data are collected and validated electronically in real- time with built in data type and logic checks with the patient at the point of care. The real-time validation logic is custom to the protocol and references new and existing patient data for immediate feedback to the user. Data modifications are tracked in a comprehensive electronic audit trail so as to not obscure changes. Changes to the source code of the electronic database are tracked and versioned. The current software version is stamped on each record as it is modified.

Data may be viewed, created, modified, deleted or exported by delegated persons according to the access roles associated with their personal accounts. The sponsor and other relevant parties may be given access to data separately with suitable notice. Security of data is ensured using authentication and encryption to render subject identity and personal health information unusable, unreadable and indecipherable to unauthorised individuals. The application and database layers use a combination of hashing and field-level encryption for sensitive and personal data. Study data are not stored on devices in the field.

Ethics and dissemination

The protocol has been approved by ethics committee of The AIDS Support Organisation, Uganda (reference number TASOREC/090/19-UG-REC-009), National Institute of Medical Research, Tanzania (reference number NIMR/HQ/R.8a/Vol. IX/3394, 23 March 2020) and the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, UK (reference number 19-100, 2 July 2020).

The findings of the study will be shared with policy-makers and senior programme managers, with civil societies (including the East African NCD (Non Communicable Disease) Alliance, the Tanzania Diabetes Association and others), with patient groups and with the participants. The findings will also be published in peer-reviewed journals.

Discussion

In this trial, we are testing the concept of a single chronic care clinic where people living with any one or more of the target conditions—HIV infection, diabetes or hypertension—may come for health services and care. Very few settings in Africa have even attempted screening of people with HIV infection for chronic conditions, despite their high prevalence. To our knowledge, there have been no attempts of a fully integrated approach to these chronic conditions as being tested in this trial.

This approach is controversial on a number of fronts. The HIV programmes are well funded and have achieved high levels of coverage of antiretroviral therapy across Africa, and we are asking them to merge with much weaker programmes. Patients have traditionally been managed in standalone specialist clinics and we are now asking them to move to management by generalist clinical staff, which will seem inferior to many specialists. Finally, patients with HIV infection have always been segregated from others, and we are now asking everyone to sit together, which will be uncomfortable to some due to the stigma associated with HIV infection.

Furthermore, the research programme cannot compensate government clinical staff for the added time that the research will take, pay for medicines or compensate patients for their time, unlike the situation in many clinical trials. For our findings to be relevant to policy-makers and other stakeholders, healthcare must be provided in close to normal health service conditions.

Central to the success of such research is the development of partnerships with policy-makers, healthcare managers and providers, patient groups and community representatives. Each of these stakeholders, in particular the policy-makers, are consulted at regular intervals and to date, they have given considerable time in setting the research strategy and the design and implementation of the research studies. Over time we created formal structures to ensure their voices were heard. Each country has a steering committee that includes representatives of the stakeholders, and which meets at least 3-monthly. We also have an international steering committee, which includes representation from the different partners and is dominated by independent researchers.

The study also involves researchers from multiple different disciplines, including clinical trialists and statisticians, social scientists and health economists, clinical researchers and programme managers and from both African and European institutions. Crucial to the success of the research programme to date has been that we operate on an ethos of equality and openness. This means that meetings are an inclusive opportunity and support where needed is given to people to contribute. We have also invested in training in communications and unconscious bias.

We have focused on just three conditions, and of the non-communicable conditions, we chose diabetes and hypertension as these are responsible for a very high disease burden and are probably more modifiable by intervention than many other chronic conditions. However, we see the test of these three conditions in integration as a test of proof of concept so that if integration is shown to be effective, expansion to include other conditions could be considered.

Although the trial is large, we are testing integration in a small proportion of patients attending health facilities. The evidence was simply lacking to change the healthcare model at each clinic. Thus, further research will be needed to estimate the effects of transforming entire clinics to integration.

We did consider other study designs to answer our question. For example, it would have been possible to recruit patients in integrated and in vertical care from the same health facilities as the clinics often run on different days. This could have reduced costs; but risked greater contamination between the intervention and control arms and risked confusion among busy clinical staff and facility managers.

A challenge of such cluster randomised trials is that participants and clinicians cannot be blinded, and further, that people may have their biases of which intervention should work. Thus, we have restricted evaluation to largely biomedical objective endpoints. We also train staff regularly, reminding them of the critical role of equipoise in trials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all of our patient representatives and focus discussion groups who have contributed to our research.

Footnotes

Twitter: @JVLazarus

SGM and MJN contributed equally.

Contributors: SGM, MJN and SJ wrote the original protocol, secured funding and wrote the first draft of the protocol and designed the study. SGM, GM, JMg, JMu, M-CVH, MB, AG, DB, WC, LWN, EHS, KR, DW, LEC, BME, JL, SMa, SMe and KM contributed to the design of the study and to various versions of the protocol and this paper. JL, GG, NS, PGS and AK also contributed to the study design and oversaw the study as members of the study steering committee. SK, JB and IN co-ordinated the implementation of the study in Tanzania and Uganda with support from JO. EvW designed the data systems. We would like to thank all of our patient representatives and focus discussion groups who have contributed to our research.

Funding: This work is funded by the EU Horizon 2020 programme, grant number 825 698.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Atun R, Davies JI, Gale EAM, et al. Diabetes in sub-Saharan Africa: from clinical care to health policy. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2017;5:622–67. 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30181-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators . Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet 2016;388:1659–724. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31679-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organizaion . World health organisation fact sheets 2020.

- 4.Van Hout M-C, Bachmann M, Lazarus JV, et al. Strengthening integration of chronic care in Africa: protocol for the qualitative process evaluation of integrated HIV, diabetes and hypertension care in a cluster randomised controlled trial in Tanzania and Uganda. BMJ Open 2020;10:e039237. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dudley L, Garner P. Strategies for integrating primary health services in low- and middle-income countries at the point of delivery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;7:CD003318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haregu TN, Setswe G, Elliott J, et al. Integration of HIV/AIDS and noncommunicable diseases in developing countries: rationale, policies and models. IJH 2015;1:21–7. 10.5430/ijh.v1n1p21 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haldane V, Legido-Quigley H, Chuah FLH, et al. Integrating cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, and diabetes with HIV services: a systematic review. AIDS Care 2018;30:103–15. 10.1080/09540121.2017.1344350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khabala KB, Edwards JK, Baruani B, et al. Medication adherence clubs: a potential solution to managing large numbers of stable patients with multiple chronic diseases in informal settlements. Trop Med Int Health 2015;20:1265–70. 10.1111/tmi.12539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ameh S. Evaluation of an integrated HIV and hypertension management model in rural South Africa: a mixed methods approach. Glob Health Action 2020;13:1750216. 10.1080/16549716.2020.1750216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahomed OH, Asmall S. Development and implementation of an integrated chronic disease model in South Africa: lessons in the management of change through improving the quality of clinical practice. Int J Integr Care 2015;15:e038. 10.5334/ijic.1454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shiri T, Birungi J, Garrib AV, et al. Patient and health provider costs of integrated HIV, diabetes and hypertension ambulatory health services in low-income settings - an empirical socio-economic cohort study in Tanzania and Uganda. BMC Med. In Press 2021;19:230. 10.1186/s12916-021-02094-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adeyemi O, Lyons M, Njim T, et al. Integration of non-communicable disease and HIV/AIDS management: a review of healthcare policies and plans in East Africa. BMJ Glob Health 2021;6:e004669. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bintabara D, Ngajilo D. Readiness of health facilities for the outpatient management of non-communicable diseases in a low-resource setting: an example from a facility-based cross-sectional survey in Tanzania. BMJ Open 2020;10:e040908. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bintabara D, Shayo FK. Disparities in availability of services and prediction of the readiness of primary healthcare to manage diabetes in Tanzania. Prim Care Diabetes 2021;15:365–71. 10.1016/j.pcd.2020.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katende D, Mutungi G, Baisley K, et al. Readiness of Ugandan health services for the management of outpatients with chronic diseases. Trop Med Int Health 2015;20:1385–95. 10.1111/tmi.12560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ford N, Ball A, Baggaley R, et al. The WHO public health approach to HIV treatment and care: looking back and looking ahead. Lancet Infect Dis 2018;18:e76–86. 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30482-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jaffar S, Amuron B, Birungi J, et al. Integrating research into routine service delivery in an antiretroviral treatment programme: lessons learnt from a cluster randomized trial comparing strategies of HIV care in Jinja, Uganda. Trop Med Int Health 2008;13:795–800. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02068.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shayo E, Van Hout MC, Birungi J, et al. Ethical issues in intervention studies on the prevention and management of diabetes and hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa. BMJ Glob Health 2020;5:e002193. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.(CDC) CfDCaP . Hypertension Cascade: Hypertension Prevalence, Treatment and Control Estimates Among US Adults Aged 18 Years and Older Applying the Criteria From the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association’s 2017 Hypertension Guideline—NHANES 2013–2016, 2019. Available: https://millionhearts.hhs.gov/data-reports/hypertension-prevalence.html [Accessed 12 Nov 2020].

- 20.Gill G, Gebrekidan A, English P, et al. Diabetic complications and glycaemic control in remote North Africa. QJM 2008;101:793–8. 10.1093/qjmed/hcn096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manne-Goehler J, Geldsetzer P, Agoudavi K, et al. Health system performance for people with diabetes in 28 low- and middle-income countries: a cross-sectional study of nationally representative surveys. PLoS Med 2019;16:e1002751. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mills KT, Bundy JD, Kelly TN, et al. Global disparities of hypertension prevalence and control: a systematic analysis of population-based studies from 90 countries. Circulation 2016;134:441–50. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosen S, Fox MP, Gill CJ. Patient retention in antiretroviral therapy programs in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PLoS Med 2007;4:e298. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adams G, Gulliford MC, Ukoumunne OC, et al. Patterns of intra-cluster correlation from primary care research to inform study design and analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 2004;57:785–94. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Campbell MK, Fayers PM, Grimshaw JM. Determinants of the intracluster correlation coefficient in cluster randomized trials: the case of implementation research. Clin Trials 2005;2:99–107. 10.1191/1740774505cn071oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mfinanga S, Chanda D, Kivuyo SL, et al. Cryptococcal meningitis screening and community-based early adherence support in people with advanced HIV infection starting antiretroviral therapy in Tanzania and Zambia: an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015;385:2173–82. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60164-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655. 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.