Abstract

BACKGROUND

Pancreatic paragangliomas (PPGL) are rare benign neuroendocrine neoplasms but malignancy can occur. PPGL are often misdiagnosed as pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor or pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

CASE SUMMARY

We reviewed 47 case reports of PPGL published in PubMed to date. Fifteen patients (15/47) with PPGL underwent endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA). Only six (6/15) were correctly diagnosed as PPGL. All patients with PPGL underwent surgical resection except three (one patient surgery was aborted because of hypertensive crisis, two patients had metastasis or involvement of major vessels). Our patient remained on close surveillance as she was asymptomatic.

CONCLUSION

Accurate preoperative diagnosis of PPGL can be safely achieved by EUS-FNA with immunohistochemistry. Multidisciplinary team approach should be considered to bring the optimal results in the management of PPGL.

Keywords: Pancreatic paraganglioma, Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration, Meta-iodobenzylguanidine scan, Metanephrines, GATA-3, Immunohistochemistry, Case report

Core Tip: The morphologic overlap between pancreatic paraganglioma and neuroendocrine tumor is significant. An accurate diagnosis by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration requires firstly that the possibility of paraganglioma is considered and secondly that a cell block is available for immunohistochemical stains. A patient-centered approach supported by a multidisciplinary team of radiologists, advanced endoscopists, endocrinologists, pathologists, oncologists, and surgeons is paramount in the management of pancreatic paraganglioma.

INTRODUCTION

Paragangliomas are rare neuroendocrine neoplasms arising from the sympathetic and parasympathetic paraganglia. This tumor is called pheochromocytoma in the adrenal medulla and elsewhere is known as extra-adrenal paraganglioma or simply as paraganglioma. The malignant potential of these tumors is difficult to predict. Most behave in a benign manner, but metastasis, which best defines malignant paraganglioma, may occur in 15%-20%[1]. When found in or around the pancreas this tumor is often misdiagnosed as pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (PNET) or even pancreatic adenocarcinoma. In this study, we report a case of pancreatic paraganglioma diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) and review of the literature on pancreatic paraganglioma.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 73-year-old female presented with a chief complaint for evaluation of an incidental finding of peripancreatic lymph node.

History of present illness

She underwent computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis as part of her routine surveillance for extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT-lymphoma) of the lung and was found to have peripancreatic lymph node. She denied any abdominal pain, change in bowel habit, weight loss, nausea, or vomiting.

History of past illness

Her medical history was significant for MALT-lymphoma, invasive lobular breast carcinoma, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, mitral valve prolapse, mitral valve stenosis, and actinic keratosis. Her surgical history included a mastectomy with sentinel lymph node dissection, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, tonsillectomy, left knee replacement, and bilateral carpal tunnel repair.

Personal and family history

Her family history was significant for colon cancer in maternal grandmother at the age of 65 years, prostate cancer in brother at the age of 63 years, and melanoma in mother. She had no history of alcohol or tobacco abuse. She has 2 children and attained menopause at the age of 52 years. Her medications included aspirin, furosemide, carvedilol, rosuvastatin, amiodarone, digoxin, anastrozole, and Eliquis.

Physical examination

Her physical examination was unremarkable, and her abdomen was soft nontender, nondistended with no palpable mass.

Laboratory examinations

Laboratory exam including fractionated metanephrines, chromogranin, and gastrin were negative.

Imaging examinations

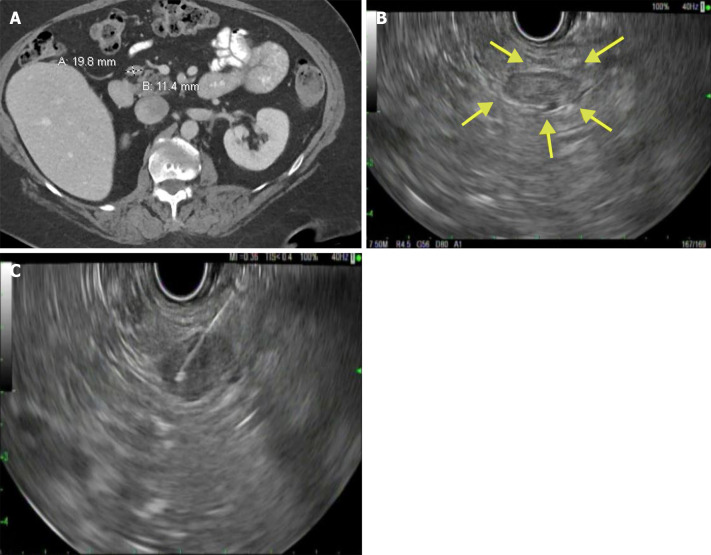

CT of the abdomen and pelvis showed 2 cm × 1.1 cm lymph node adjacent to the pancreatic head (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Computed tomography and endoscopy examinations. A: Computed tomography of abdomen pelvis showing a peripancreatic lymph node adjacent to the pancreatic head; B: Endoscopic ultrasonography showing a hypoechoic lesion near the pancreatic head; C: Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration of the peripancreatic lesion.

Endoscopy

EUS showed a 19 mm × 11.5 mm hypoechoic lesion near the pancreatic head (Figure 1B). Two FNA passes using a 25-gauge needle were performed via transduodenal approach (Figure 1C).

Pathology

Direct FNA smears showed tumor with neuroendocrine features. Initial immunoperoxidase stains performed on cell block sections were positive for synaptophysin and chromogranin, which seemed to confirm the morphologic impression of PNET. The pathologist was subsequently informed about the peripancreatic location and lack of a definite pancreatic lesion.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

After additional testing showed the tumor to be positive for GATA-3 and negative for keratin with low expression of Ki-67 (less than 1%), the FNA diagnosis was revised to paraganglioma.

TREATMENT

Our patient was referred to endocrine surgery team after the FNA diagnosis of paraganglioma. After a thorough discussion with the patient on the benefits and risks of surgical resection, the patient elected to remain on close surveillance since she was asymptomatic with a 2-cm, nonfunctioning paraganglioma.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

After a 1-year follow up, patient was found to have stable asymptomatic peripancreatic paraganglioma with no increase in size.

DISCUSSION

Paragangliomas are non-epithelial neuroendocrine neoplasms arising in close association with components of the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems[2]. Most parasympathetic paragangliomas are nonfunctional and located along the glossopharyngeal and vagal nerves in the neck and base of the skull[3]. Sympathetic paraganglia secrete catecholamines (functional) and they are commonly located in the paravertebral ganglia of thorax, abdomen, and pelvis[3]. The incidence of extra-adrenal paraganglioma is unclear as these are often described with pheochromocytoma. In the United States, approximately 500-1600 cases are diagnosed every year and the combined annual incidence of pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma is approximately 0.8 per 100000 person-years[4,5]. Pancreatic paragangliomas are more common in women than men (2:1) and the mean age of incidence is 52 years (19-85 years)[6].

Patients with functional paragangliomas can experience hypertension, headache, sweating, and palpitations due to the excessive secretion of catecholamines[7]. Nonsecretory paragangliomas may present with abdominal mass with or without abdominal pain, but most are found incidentally on imaging studies[8,9]. CT has a sensitivity of approximately 90% in the identification of extra-adrenal paragangliomas, which frequently appear as highly vascular structures with areas of intralesional hemorrhage and necrosis[8,10]. The CT findings of pancreatic paragangliomas differ from those of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by their location at the pancreatic head and absence of biliary dilation, although mild pancreatic duct dilatation is sometimes seen[11]. Paragangliomas are also differentiated from nonfunctioning islet cell tumor of the pancreas by observation of early contrast filling of the prominent draining veins of the tumor and the portal vein[12]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides tissue characterization superior to CT without radiation[13]. Working synergistically, meta-iodobenzylguanidine (MIBG, I123 or I131) scan is useful in differentiating functional from nonfunctional paragangliomas as well as in the detection of tumors in unusual locations, multiple primary tumors, and metastasis[13]. MIBG scan has a sensitivity of 85% and specificity of 95%-100% in the detection of extra-adrenal paragangliomas. Plasma or urinary metanephrines can be used to further establish the diagnosis of functional paragangliomas[13,14].

While most paragangliomas are solitary and sporadic, they can be multicentric and hereditary. Genetic testing should be considered in all patients diagnosed with paraganglioma as nearly 40% (pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma) carry germline mutations. Genetic testing allows for the identification of simultaneous cancers in hereditary syndromes and assists with screening family members at high risk[15]. The most common genetic mutations associated with paragangliomas are RET gene in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A and 2B, VHL in von Hippel-Lindau disease, NF1 in neurofibromatosis type 1, and succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) B, D, C genes[15].

One of the most valuable tools that can assist in establishing the diagnosis of paraganglioma is EUS, which both enables localization of the mass and acquisition of tissue samples for cytology via FNA. When not considered in the differential diagnosis, pancreatic paragangliomas can be easily misdiagnosed on EUS-FNA cytology as pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (NET)[16,17]. Some authors suggest that EUS-FNA should not be done in functional paragangliomas as it can trigger the secretion of catecholamines[18]. In our case, the diagnosis was not established before EUS-FNA and there were no complications during and after the procedure.

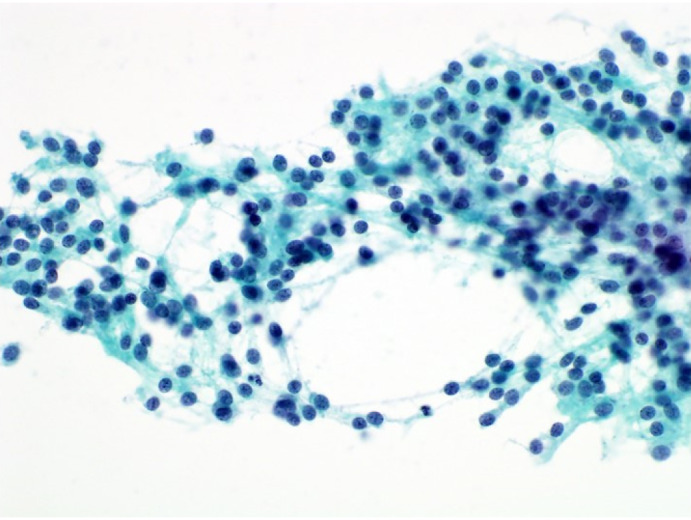

On cytology, the cells of paragangliomas are relatively uniform in size, epithelioid in appearance with round to oval nuclei, and arranged in loosely cohesive clusters[19]. Morphological patterns like acinar/glandular architecture and rosette-like arrangements can be observed in paragangliomas[20]. In histologic sections, the tumor is typically composed of nests of cells separated by a highly vascularized network[21].

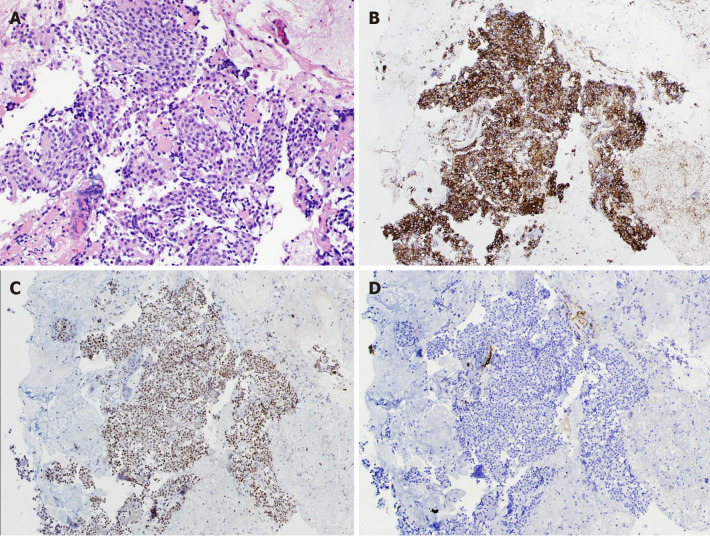

Although the morphologic overlap between paraganglioma and NET is significant, the distinction can be confidently made with immunoperoxidase stains, which require a cell block preparation. Both pancreatic paragangliomas and NETs readily express neuroendocrine markers like synaptophysin and chromogranin[19]. While most NETs are immunoreactive to pancytokeratins (AE1/AE3 and CAM 5.2) but not vimentin, paragangliomas show the opposite profile[19]. GATA-3 and PAX-8 can also be used to distinguish paragangliomas from NETs. Paragangliomas from any anatomic site are immunoreactive to GATA-3 in approximately 55% of the cases, but NETs are always nonreactive[22]. Of note, GATA-3 can be positive in cells of breast, urothelial, and pancreatic origin[23]. PAX-8 has a sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 74% for primary pancreatic NETs, but paragangliomas have weak or negative immunoreactivity to PAX -8[24-26]. In our case, FNA smears with Papanicolaou stain showed abundant, tangled cellular processes and relatively uniform nuclei with finely granular chromatin and indistinct nucleoli (Figure 2). FNA cell block with hematoxylin and eosin stain (Figure 3A), diffuse cytoplasmic staining with chromogranin (Figure 3B), diffuse nuclear staining with GATA-3 (Figure 3C), and no staining with keratin cocktail (Figure 3D).

Figure 2.

Fine needle aspiration direct smear. Papanicolaou stain, × 400.

Figure 3.

Fine needle aspiration cell block. A: Hematoxylin and eosin stain, × 200; B: Diffuse cytoplasmic staining, chromogranin (× 100); C: Diffuse nuclear staining, GATA-3, (× 100); D: No staining, keratin cocktail (× 100).

Since there are no definitive criteria for the diagnosis of malignancy in paraganglioma apart from metastasis, the treatment of choice for paraganglioma is surgical resection. For functional paragangliomas, preoperative administration of α-adrenergic receptor blocker can help prevent a hypertensive crisis during the surgery[27]. The most common sites of metastasis include the regional lymph nodes, bone, lung, and liver, and the dissemination usually occurs through blood or lymph nodes[28]. When surgery is not feasible, radiation therapy can be considered[29]. For malignant paragangliomas, treatment with I131 MIBG or combination chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and dacarbazine) is effective[30]. Octreotide is also useful in inoperable paragangliomas[31].

Our review of the literature in the English language found 47 case reports of pancreatic paragangliomas published in PubMed to date (Table 1). Fifteen patients with pancreatic paragangliomas underwent EUS-FNA; six were correctly diagnosed as paraganglioma; six were misdiagnosed as NET; one had no diagnosis; one was diagnosed as spindle cell neoplasm; and one was diagnosed as pseudocyst. All patients with a pancreatic paraganglioma underwent surgery except three: one patient who developed a hypertensive crisis during the surgery (thus surgery was aborted)[32]; and two patients with metastasis or involvement of the major vessels[10,16].

Table 1.

Reported cases of pancreatic paraganglioma in the literature

|

No.

|

Ref.

|

Age

|

Gender

|

Size

|

Location

|

EUS-FNA

|

Preop-diagnosis

|

Surgery

|

Postop diagnosis

|

| 1 | Fujino et al[21] | 61 | Male | 2.5 cm | Uncinate process | No | PNET | Pancreaticoduodenectomy | PPGL |

| 2 | Ohkawara et al[33] | 72 | Female | 4 cm | Head | No | NET | Surgical resection of head | PPGL |

| 3 | Perrot et al[34] | 41 | Female | 4.3 cm | Tail | No | PPGL | Tumor resection | PPGL |

| 4 | Tsukada et al[35] | 51 | Male | 2.5 cm | Uncinate | No | PNET | Surgical resection | PPGL |

| 5 | Kim et al[12] | 57 | Female | 7 cm | Head | No | Non-functioning islet cell tumor | Pancreaticoduodenectomy | PPGL |

| 6 | Paik[36] | 70 | Female | 4.2 cm | Tail | No | None | Distal pancreatectomy | PPGL |

| 7 | He et al[37] | 40 | Female | 4.5 cm | Uncinate | No | None | Surgical resection | PPGL |

| 8 | Higa and Kapur[38] | 65 | Female | 2.1 cm | Uncinate | No | None | Pancreaticoduodenectomy | PPGL |

| 9 | Al-jiffry et al[39] | 19 | Female | 9.5 cm | Head and neck | No | Sarcoma | Pancreaticoduodenectomy | PPGL |

| 10 | Zhang et al[27] | 50 | Female | 6 cm | Head | Yes | Functional PPGL | Chemotherapy | PPGL |

| 11 | Zhang et al[27] | 63 | Female | 4 cm | Head | No | Functional PPGL | Surgical resection | PPGL |

| 12 | Borgohain et al[40] | 55 | Female | 19 cm | Tail | No | Pancreatic cancer | Surgical resection | PPGL |

| 13 | Straka et al[41] | 53 | Female | Not mentioned | Head | No | None | Surgical resection | PPGL |

| 14 | Meng et al[11] | 54 | Female | 3 cm | Head | No | None | Surgical resection | PPGL |

| 15 | Meng et al[11] | 41 | Female | 6.2 cm | Head | No | None | Surgical resection | PPGL |

| 16 | Misumi et al[42] | 47 | Female | 1.5 cm | Head | EUS only | PNET | Pancreaticoduodenectomy | PPGL |

| 17 | Bartley et al[43] | 75 | Female | 15 cm | Tail | No | Pancreatic cyst | Not available | PPGL |

| 18 | Bartley et al[43] | 70 | Female | 3 cm | Head | No | Pancreatic cyst | Not available | PPGL |

| 19 | Cope et al[44] | 72 | Female | 14 cm | Head | No | Cystadenoma | Not available | PPGL |

| 20 | Zamir et al[45] | 47 | Male | 10 cm | Body | No | Pancreatic cyst | Not available | PPGL |

| 21 | Parithivel et al[46] | 85 | Male | 6 cm | Head | No | NET | Surgical resection | PPGL |

| 22 | Wang et al[32] | 30 | Female | 6.4 cm | Tail | No | None | No surgery | PPGL |

| 23 | Ganc et al[18] | 37 | Female | 4.8 cm | Head | Yes | NET | Pancreatico duodenectomy | PPGL |

| 24 | Tumuluru et al[47] | 62 | Female | 2.9 cm | Body | Yes | NET | Distal pancreatectomy/splenectomy | PPGL |

| 25 | Ginesu et al[48] | 55 | Male | 2.5 cm | Uncinate | No | NET | pancreaticoduodenectomy | PPGL |

| 26 | Liang and Xu[6] | 41 | Male | 6.4 cm | Uncinate | No | NET | pancreaticoduodenectomy | PPGL |

| 27 | Lin et al[3] | 42 | Female | 6.3 cm | Body | No | NET | Middlesegment pancreatectomy | PPGL |

| 28 | Nguyen et al[23] | 70 | Female | 5.8 cm | Tail | Yes | PPGL | Surgical resection | PPGL |

| 29 | Zeng et al[19] | 58 | Female | 6.5 cm | Head | Yes | NET | Surgical resection | PPGL |

| 30 | Zeng et al[19] | 53 | Female | 2.5 cm | Head | Yes | NET | Surgical resecion | PPGL |

| 31 | Singhi et al[16] | 61 | Female | 14 cm | Tail | Yes | Pseudocyst | Surgical resection | PPGL |

| 32 | Singhi et al[16] | 52 | Female | 14 cm | Body | Yes | PPGL | Not performed | PPGL |

| 33 | Singhi et al[16] | 54 | Female | 6.5 cm | Head | Yes | PPGL | Surgical resection | PPGL |

| 34 | Singhi et al[16] | 40 | Male | 5.1 cm | Body | Yes | NET | Surgical resection | PPGL |

| 35 | Singhi et al[16] | 78 | Female | 17 cm | Body | Yes | Spindle cell neoplasm | Surgical resection | PPGL |

| 36 | Singhi et al[16] | 44 | Male | 5.5 cm | Head | Yes | PPGL | Surgical resection | PPGL |

| 37 | Singhi et al[16] | 38 | Male | 15 cm | Body | No | None | Surgical resection | PPGL |

| 38 | Singhi et al[16] | 47 | Male | 7.5 cm | Body | No | NET | Surgical resection | PPGL |

| 39 | Singhi et al[16] | 37 | Female | 5.7 cm | Tail | No | NET | Surgical resection | PPGL |

| 40 | Fite and Maleki[49] | 40 | Male | 5.1 cm | Peripancreatic | No | NET | Surgical resection | PPGL |

| 41 | Fite and Maleki[49] | 23 | Female | 7.0 cm | Peripancreatic | No | NET | Surgical resection | PPGL |

| 42 | Malthouse et al[50] | 58 | Male | 8 cm | Head | No | NET | Not available | PPGL |

| 43 | Malthouse et al[50] | 45 | Female | 8 cm | Head | No | Retro peritoneal tumor | Not available | PPGL |

| 44 | Sangster et al[10] | 50 | Male | Not available | Head | Yes | Poorly differentiatedcarcinoma | Radiation treatment | PPGL |

| 45 | Lightfoot et al[51] | 66 | Male | 6 cm | Head/uncinate | No | None | Pancreaticoduodenectomy | PPGL |

| 46 | Abbasi et al[52] | 61 | Female | 7.2 cm | Head/uncinate | Yes | NET | Pancreaticoduodenenctomy | PPGL |

| 47 | Present case | 73 | Female | 2 cm | Head | Yes | PPGL | No surgery | PPGL |

PPGL: Pancreatic paraganglioma; PNET: Pancreatic Neuroendocrine tumor; EUS-FNA: Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration.

Our case illustrates that accurate preoperative diagnosis of paraganglioma can be safely made by EUS-FNA. When paragangliomas are small and asymptomatic, it would be reasonable to follow them with periodic imaging studies.

CONCLUSION

Pancreatic paragangliomas are rare and EUS-FNA is a valuable tool in establishing the diagnosis. When assessing a lesion in the pancreas, paraganglioma should be included in the differential diagnoses along with PNET and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. As EUS-FNA can trigger a hypertensive crisis in functional pancreatic paragangliomas, pre-procedure use of alpha-adrenergic blocker should be considered. To bring the optimal result in the management of paraganglioma, it is imperative to have a multidisciplinary team approach involving radiologists, advanced endoscopists, endocrinologists, pathologists, oncologists, and surgeons.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: None of the authors have any potential conflicts (financial, professional, or personal) that are relevant to the manuscript.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: April 6, 2021

First decision: June 17, 2021

Article in press: September 3, 2021

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Zhou Y S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

Contributor Information

Gandhi Lanke, Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Lubbock, TX 79407, United States.

John M Stewart, Pathology-lab Medicine Division, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77030, United States.

Jeffrey H Lee, Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77030, United States. jefflee@mdanderson.org.

References

- 1.Lenders JW, Eisenhofer G, Mannelli M, Pacak K. Phaeochromocytoma. Lancet. 2005;366:665–675. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asa SL, Ezzat S, Mete O. The Diagnosis and Clinical Significance of Paragangliomas in Unusual Locations. J Clin Med. 2018;7 doi: 10.3390/jcm7090280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin S, Peng L, Huang S, Li Y, Xiao W. Primary pancreatic paraganglioma: a case report and literature review. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14:19. doi: 10.1186/s12957-016-0771-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beard CM, Sheps SG, Kurland LT, Carney JA, Lie JT. Occurrence of pheochromocytoma in Rochester, Minnesota, 1950 through 1979. Mayo Clin Proc. 1983;58:802–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen H, Sippel RS, O'Dorisio MS, Vinik AI, Lloyd RV, Pacak K North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (NANETS) The North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society consensus guideline for the diagnosis and management of neuroendocrine tumors: pheochromocytoma, paraganglioma, and medullary thyroid cancer. Pancreas. 2010;39:775–783. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181ebb4f0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liang W, Xu S. CT and MR Imaging Findings of Pancreatic Paragangliomas: A Case Report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e2959. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lack EE, Cubilla AL, Woodruff JM, Lieberman PH. Extra-adrenal paragangliomas of the retroperitoneum: A clinicopathologic study of 12 tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 1980;4:109–120. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198004000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaltsas GA, Besser GM, Grossman AB. The diagnosis and medical management of advanced neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:458–511. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elder EE, Elder G, Larsson C. Pheochromocytoma and functional paraganglioma syndrome: no longer the 10% tumor. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89:193–201. doi: 10.1002/jso.20177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sangster G, Do D, Previgliano C, Li B, LaFrance D, Heldmann M. Primary retroperitoneal paraganglioma simulating a pancreatic mass: a case report and review of the literature. HPB Surg. 2010;2010:645728. doi: 10.1155/2010/645728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meng L, Wang J, Fang SH. Primary pancreatic paraganglioma: a report of two cases and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:1036–1039. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i3.1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim SY, Byun JH, Choi G, Yu E, Choi EK, Park SH, Lee MG. A case of primary paraganglioma that arose in the pancreas: the Color Doppler ultrasonography and dynamic CT features. Korean J Radiol. 2008;9 Suppl:S18–S21. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2008.9.s.s18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Gils AP, Falke TH, van Erkel AR, Arndt JW, Sandler MP, van der Mey AG, Hoogma RP. MR imaging and MIBG scintigraphy of pheochromocytomas and extraadrenal functioning paragangliomas. Radiographics. 1991;11:37–57. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.11.1.1671719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plouin PF, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP. Initial work-up and long-term follow-up in patients with phaeochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;20:421–434. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dahia PL. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma pathogenesis: learning from genetic heterogeneity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:108–119. doi: 10.1038/nrc3648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singhi AD, Hruban RH, Fabre M, Imura J, Schulick R, Wolfgang C, Ali SZ. Peripancreatic paraganglioma: a potential diagnostic challenge in cytopathology and surgical pathology. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1498–1504. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182281767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiménez-Heffernan JA, Vicandi B, López-Ferrer P, González-Peramato P, Pérez-Campos A, Viguer JM. Cytologic features of pheochromocytoma and retroperitoneal paraganglioma: a morphologic and immunohistochemical study of 13 cases. Acta Cytol. 2006;50:372–378. doi: 10.1159/000325975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ganc RL, Castro AC, Colaiacovo R, Vigil R, Rossini LG, Altenfelder R. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration for the diagnosis of nonfunctional paragangliomas: a case report and review of the literature. Endosc Ultrasound. 2012;1:108–109. doi: 10.7178/eus.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeng J, Simsir A, Oweity T, Hajdu C, Cohen S, Shi Y. Peripancreatic paraganglioma mimics pancreatic/gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumor on fine needle aspiration: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Diagn Cytopathol. 2017;45:947–952. doi: 10.1002/dc.23761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gong Y, DeFrias DV, Nayar R. Pitfalls in fine needle aspiration cytology of extraadrenal paraganglioma. A report of 2 cases. Acta Cytol. 2003;47:1082–1086. doi: 10.1159/000326652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujino Y, Nagata Y, Ogino K, Watahiki H, Ogawa H, Saitoh Y. Nonfunctional paraganglioma of the pancreas: report of a case. Surg Today. 1998;28:209–212. doi: 10.1007/s005950050108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weissferdt A, Kalhor N, Liu H, Rodriguez J, Fujimoto J, Tang X, Wistuba II, Moran CA. Thymic neuroendocrine tumors (paraganglioma and carcinoid tumors): a comparative immunohistochemical study of 46 cases. Hum Pathol. 2014;45:2463–2470. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2014.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen E, Nakasaki M, Lee TK, Lu D. Diagnosis of paraganglioma as a pancreatic mass: A case report. Diagn Cytopathol. 2018;46:804–806. doi: 10.1002/dc.23974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sangoi AR, Ohgami RS, Pai RK, Beck AH, McKenney JK. PAX8 expression reliably distinguishes pancreatic well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors from ileal and pulmonary well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors and pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:412–424. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koo J, Mertens RB, Mirocha JM, Wang HL, Dhall D. Value of Islet 1 and PAX8 in identifying metastatic neuroendocrine tumors of pancreatic origin. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:893–901. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Long KB, Srivastava A, Hirsch MS, Hornick JL. PAX8 Expression in well-differentiated pancreatic endocrine tumors: correlation with clinicopathologic features and comparison with gastrointestinal and pulmonary carcinoid tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:723–729. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181da0a20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang L, Liao Q, Hu Y, Zhao Y. Paraganglioma of the pancreas: a potentially functional and malignant tumor. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:218. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-12-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verma A, Pandey D, Akhtar A, Arsia A, Singh N. Non-functional paraganglioma of retroperitoneum mimicking pancreatic mass with concurrent urinary bladder paraganglioma: an extremely rare entity. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:XD09–XD11. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/11156.5570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang JH, Bae SJ, Park S, Park HK, Jung HS, Chung JH, Min YK, Lee MS, Kim KW, Lee MK. Bilateral pheochromocytoma associated with paraganglioma and papillary thyroid carcinoma: report of an unusual case. Endocr J. 2007;54:227–231. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k06-068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fitzgerald PA, Goldsby RE, Huberty JP, Price DC, Hawkins RA, Veatch JJ, Dela Cruz F, Jahan TM, Linker CA, Damon L, Matthay KK. Malignant pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas: a phase II study of therapy with high-dose 131I-metaiodobenzylguanidine (131I-MIBG) Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1073:465–490. doi: 10.1196/annals.1353.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tonyukuk V, Emral R, Temizkan S, Sertçelik A, Erden I, Corapçioğlu D. Case report: patient with multiple paragangliomas treated with long acting somatostatin analogue. Endocr J. 2003;50:507–513. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.50.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang ZL, Fu L, Zhang Y, Babu SR, Tian B. An asymptomatic pheochromocytoma originating from the tail of the pancreas. Pancreas. 2012;41:165–167. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31822362d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohkawara T, Naruse H, Takeda H, Asaka M. Primary paraganglioma of the head of pancreas: contribution of combinatorial image analyses to the diagnosis of disease. Intern Med. 2005;44:1195–1196. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.44.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perrot G, Pavic M, Milou F, Crozes C, Faucompret S, Vincent E. [Difficult diagnosis of a pancreatic paraganglioma] Rev Med Interne. 2007;28:701–704. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsukada A, Ishizaki Y, Nobukawa B, Kawasaki S. Paraganglioma of the pancreas: a case report and review of the literature. Pancreas. 2008;36:214–216. doi: 10.1097/01.MPA.0000311841.35183.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paik KY. [Paraganglioma of the pancreas metastasized to the adrenal gland: a case report] Korean J Gastroenterol. 2009;54:409–412. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2009.54.6.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.He J, Zhao F, Li H, Zhou K, Zhu B. Pancreatic paraganglioma: A case report of CT manifestations and literature review. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2011;1:41–43. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4292.2011.08.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Higa B, Kapur U. Malignant paraganglioma of the pancreas. Pathology. 2012;44:53–55. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0b013e32834e42b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al-Jiffry BO, Alnemary Y, Khayat SH, Haiba M, Hatem M. Malignant extra-adrenal pancreatic paraganglioma: case report and literature review. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:486. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Borgohain M, Gogoi G, Das D, Biswas M. Pancreatic paraganglioma: An extremely rare entity and crucial role of immunohistochemistry for diagnosis. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;17:917–919. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.117217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Straka M, Soumarova R, Migrova M, Vojtek C. Pancreatic paraganglioma - a rare and dangerous entity. Vascular anatomy and impact on management. J Surg Case Rep. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1093/jscr/rju074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Misumi Y, Fujisawa T, Hashimoto H, Kagawa K, Noie T, Chiba H, Horiuchi H, Harihara Y, Matsuhashi N. Pancreatic paraganglioma with draining vessels. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:9442–9447. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i31.9442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bartley O, Ekdahl PH, Hultén L. Paraganglioma simulating pancreatic cyst. Acta Chir Scand. 1966;132:289–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cope C, Greenberg SH, Vidal JJ, Cohen EA. Nonfunctioning nonchromaffin paraganglioma of the pancreas. Arch Surg. 1974;109:440–442. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1974.01360030092024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zamir O, Amir G, Lernau O, Ne'eman Z, Nissan S. Nonfunctional paraganglioma of the pancreas. Am J Gastroenterol. 1984;79:761–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parithivel VS, Niazi M, Malhotra AK, Swaminathan K, Kaul A, Shah AK. Paraganglioma of the pancreas: literature review and case report. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:438–441. doi: 10.1023/a:1005401718763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tumuluru S, Mellnick V, Doyle M, Goyal B. Pancreatic Paraganglioma: A Case Report. Case Rep Pancreat Cancer. 2016;2:79–83. doi: 10.1089/crpc.2016.0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ginesu GC, Barmina M, Paliogiannis P, Trombetta M, Cossu ML, Feo CF, Addis F, Porcu A. Nonfunctional paraganglioma of the head of the pancreas: A rare case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;28:81–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fite JJ, Maleki Z. Paraganglioma: Cytomorphologic features, radiologic and clinical findings in 12 cases. Diagn Cytopathol. 2018;46:473–481. doi: 10.1002/dc.23928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Malthouse SR, Robinson L, Rankin SC. Ultrasonic and computed tomographic appearances of paraganglioma simulating pancreatic mass. Clin Radiol. 1992;45:271–272. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(05)80013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lightfoot N, Santos P, Nikfarjam M. Paraganglioma mimicking a pancreatic neoplasm. JOP. 2011;12:259–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abbasi A, Wakeman KM, Pillarisetty VG. Pancreatic paraganglioma mimicking pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. Rare Tumors. 2020;12:2036361320982799. doi: 10.1177/2036361320982799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]