Abstract

DNA fingerprinting analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is used for epidemiological studies and the control of laboratory cross-contamination. Because standardized procedures are not entirely safe for mycobacteriology laboratory staff, the paper proposes a new technique for the processing of specimens. The technique ensures the inactivation of M. tuberculosis before DNA extraction without the loss of DNA integrity. The control of inactivated cultures should be rigorous and should involve the use of two different culture media incubated for at least 4 months.

Analysis of restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs) with the IS6110 sequence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a current practice in reference laboratories for epidemiological studies or for the detection of laboratory cross-contamination (1, 3, 4–6). However, standardized analytic procedures are not completely safe for mycobacteriology laboratory staff. In 1997, a case of pulmonary tuberculosis was reported to be acquired in the mycobacteriology laboratory by a laboratory technician who had no apparent risk factors (2). The individual was working in a biosafety level III laboratory with specific procedures to minimize laboratory cross-contamination. The infected individual was performing IS6110 RFLP analysis by the standardized protocol (5), in which a large load of M. tuberculosis in the culture was inactivated for 20 min at 80°C after overnight growth in d-cycloserine before lysozyme and proteinase K treatment, followed by phenol-chloroform DNA extraction. The BACTEC 12B vials inoculated with those extracts were found to be positive for M. tuberculosis at day 55. It was shown that a temperature of 80°C does not inactivate M. tuberculosis and that it is necessary to maintain the cultures for more than 42 days. This clearly indicates that the RFLP technique needs to be safer.

The present study evaluated the standardized procedures used to inactivate M. tuberculosis cultures before DNA fingerprinting analysis.

Six protocols were evaluated after overnight growth of M. tuberculosis cultures in d-cycloserine: (i) 40 cultures were heated for 20 min at 80°C; (ii) 20 cultures were incubated overnight with lysozyme (0.5 mg/ml) after heating for 20 min at 80°C; (iii) 20 cultures were treated with proteinase K for 4 h at 55°C (final concentration, 0.4 mg/ml) after heating for 20 min at 80°C and overnight incubation with lysozyme (final concentration, 0.5 mg/ml); (iv) 40 cultures were heated at 100°C for 5 min in a boiling-water bath with fully immersed screw-cap glass bottles; (v) 20 cultures were treated with lysozyme (0.5 mg/ml) after boiling for 5 min at 100°C; and (vi) 20 cultures were treated with proteinase K for 4 h at 55°C (final concentration, 0.4 mg/ml) after boiling for 5 min at 100°C and overnight incubation with lysozyme (final concentration, 0.5 mg/ml). All cultures were inoculated in BACTEC 12B vials and on Lowenstein-Jensen (LJ) slants and were incubated for 4 months. All vials that were sterile after 4 months were kept in LJ slants for a further 4 months. Both cultures heated at 80 and 100°C were electrophoresed on 1% agarose gels and were visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Table 1 presents the results obtained by the different inactivation procedures. M. tuberculosis was not inactivated at 80°C in 65% of the cultures in BACTEC 12B vials and 52% of the cultures on LJ slants. Time to culture positivity ranged from 16 to 55 days (28 ± 19.80 days) by the BACTEC 12B method and 21 to 62 days on solid media (38 ± 24.04 days). Treatment with lysozyme did not substantially reduce culture positivity for specimens treated for 20 min at 80°C: 20% of cultures were positive in BACTEC 12B vials (52 ± 53.74 days), and 80% of cultures were positive on LJ slants (30.5 ± 14.85 days). Although proteinase K treatment was more effective than treatment with lysozyme alone, 10% of the cultures on LJ slants remained positive (36 ± 7.07 days), but none of the cultures in BACTEC 12B vials remained positive. After the cultures were boiled for 5 min at 100°C, all media remained sterile for 8 months (4 months for primary cultures in BACTEC 12B vials and on LJ slants and another 4 months for cultures kept in sterile BACTEC 12B vials; see above).

TABLE 1.

Inactivation of M. tuberculosisa

| Procedure | No. of cultures | MTB-positive cultures

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BACTEC 12B vial

|

LJ slants

|

||||||

| No. (%) | Time to positivity (days)

|

No. (%) | Time to positivity (days)

|

||||

| Range | Mean ± SD | Range | Mean ± SD | ||||

| 80°C, 20 min | 40 | 26 (65) | 16–55 | 28 ± 19.80 | 21 (52) | 21–62 | 38 ± 24.04 |

| 80°C, 20 min + LYS treatment | 20 | 4 (20) | 14–90 | 52 ± 53.74 | 16 (80) | 21–41 | 30.5 ± 14.85 |

| 80°C, 20 min + LYS and PK treatment | 20 | 0 | 0 | 2 (10) | 31–41 | 36 ± 7.07 | |

| Boiling for 5 min | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Boiling for 5 min + LYS treatment | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Boiling for 5 min + LYS and PK treatment | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

Abbreviations: MTB, M. tuberculosis; SD, standard deviation; LYS, lysozyme; PK, proteinase K.

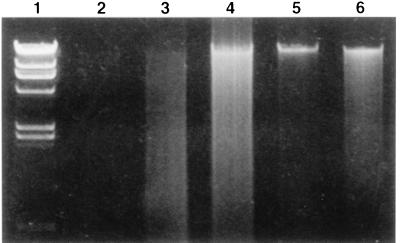

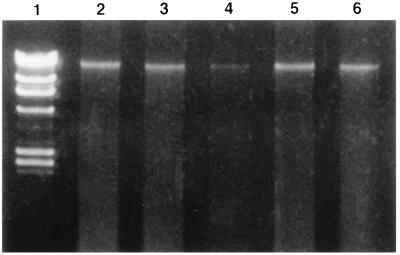

Electrophoresis of M. tuberculosis genomic DNA heated for 20 min at 80°C indicated that the DNA was sheared into pieces and had a smeared appearance (Fig. 1). Conversely, boiling of M. tuberculosis cultures for 5 min at 100°C did not modify the integrity of the genomic DNA, as shown in Fig. 1 and 2.

FIG. 1.

Analysis of M. tuberculosis genomic DNA after heat lysis. Lane 1, lambda phage molecular size markers (23.1, 9.4, 6.6, 4.4, 2.3, 2.0, and 0.6 kb); lane 2, negative control; lanes 3 and 4, M. tuberculosis DNA after 20 min of incubation at 80°C; lanes 5 and 6, M. tuberculosis DNA after heating 5 min at 100°C in a boiling-water bath.

FIG. 2.

Effect of lysozyme and proteinase K treatment on integrity of M. tuberculosis DNA boiled at 100°C for 5 min. Lane 1, lambda phage molecular size markers (23.1, 9.4, 6.6, 4.4, 2.3, 2.0, and 0.6 kb); lanes 2 to 6, genomic DNAs of five different mycobacterial isolates, respectively.

Experiments performed to investigate a laboratory case of tuberculosis contamination showed that not all tubercle bacilli are inactivated at 80°C, even after lysozyme and proteinase K treatment. These results confirm those of heat-kill experiments conducted by Zwadyk et al. (7). DNA fingerprinting analysis requires the use of greater safety precautions, and standardized procedures must ensure that M. tuberculosis cultures are really inactivated before DNA extraction is performed. The inactivated cultures should be inoculated on both a solid culture medium and a liquid culture medium to ensure that the bacteria have been inactivated. Solid media were more sensitive than liquid media since 80% of cultures grown on LJ slants versus 20% of cultures grown in BACTEC 12B vials were positive after lysozyme treatment, and 10% of cultures grown on LJ slants versus 0% of cultures grown in BACTEC 12B vials remained positive for M. tuberculosis after lysozyme and proteinase K treatment. The liquid and solid media should be incubated for at least 4 months, since some cultures became positive as long as 90 days after inoculation (Table 1). This study showed that heating of cultures at 100°C for at least 5 min is sufficient to inactivate M. tuberculosis. After heat lysis at 100°C for 5 min, the integrity of M. tuberculosis genomic DNA is conserved, as shown in our study (Fig. 1 and 2). The heating time seems to be more important than the heating temperature in preserving the integrity of the M. tuberculosis DNA. A previous study showed that genomic DNA is sheared into small pieces if it is heated for 30 min (7).

This paper proposes a method which inactivates M. tuberculosis and produces genomic DNA suitable for RFLP typing analysis.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Marie-José Gouzerh and the Mycobacteriology Laboratory of the Nantes Hospital for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bauer J, Yang Z, Poulsen S, Andersen A B. Results from 5 years of nationwide DNA fingerprinting of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex isolates in a country with a low incidence of M. tuberculosis infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:305–308. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.1.305-308.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bemer-Melchior P, Gouzerh M J, Drugeon H B. Program and abstracts of the 5th International Conference on the Prevention of Infection. 1998. Transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a mycobacteriology laboratory, abstr. 06; p. 113. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braden C R, Templeton G L, Stead W W, Bates J H, Cave M D, Valway S H. Retrospective detection of laboratory cross-contamination of Mycobacterium tuberculosis cultures with use of DNA fingerprint analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:35–40. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Small P M, McClenny N B, Singh S P, Schoolnik G K, Tompkins L S, Mickelsen P A. Molecular strain typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to confirm cross-contamination in the mycobacteriology laboratory and modification of procedures to minimize occurrence of false-positive cultures. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1677–1682. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.7.1677-1682.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Embden J D, Cave M D, Crawford J T, Dale J W, Eisenach K D, Gicquel B, Hermans P, Martin C, McAdam R, Shinnick T M, Small P M. Strain identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by DNA fingerprinting: recommendations for a standardized methodology. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:406–409. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.406-409.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Soolingen D, Hermans P W M, de Haas P E W, Soll D R, Van Embden J D A. The occurrence and stability of insertion sequences in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains: evaluation of an insertion sequence-dependent DNA polymorphism as a tool in the epidemiology of tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2578–2586. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.11.2578-2586.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zwadyk P J R, Down J A, Myers N, Dey M S. Rendering mycobacteria safe for molecular diagnostic studies and development of a lysis method for strand displacement amplification and PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2140–2146. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.9.2140-2146.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]