Abstract

Klebsiella oxytoca is a resident of the human gut. However, certain K. oxytoca toxigenic strains exist that secrete the nonribosomal peptide tilivalline (TV) cytotoxin. TV is a pyrrolobenzodiazepine that causes antibiotic-associated hemorrhagic colitis (AAHC). The biosynthesis of TV is driven by enzymes encoded by the aroX and NRPS operons. In this study, we determined the effect of environmental signals such as carbon sources, osmolarity, and divalent cations on the transcription of both TV biosynthetic operons. Gene expression was enhanced when bacteria were cultivated in tryptone lactose broth. Glucose, high osmolarity, and depletion of calcium and magnesium diminished gene expression, whereas glycerol increased transcription of both TV biosynthetic operons. The cAMP receptor protein (CRP) is a major transcriptional regulator in bacteria that plays a key role in metabolic regulation. To investigate the role of CRP on the cytotoxicity of K. oxytoca, we compared levels of expression of TV biosynthetic operons and synthesis of TV in wild-type strain MIT 09-7231 and a Δcrp isogenic mutant. In summary, we found that CRP directly activates the transcription of the aroX and NRPS operons and that the absence of CRP reduced cytotoxicity of K. oxytoca on HeLa cells, due to a significant reduction in TV production. This study highlights the importance of the CRP protein in the regulation of virulence genes in enteric bacteria and broadens our knowledge on the regulatory mechanisms of the TV cytotoxin.

Keywords: CRP, tilivalline cytotoxin, aroX, npsA, Klebsiella oxytoca

Introduction

The human gut microbiota is a complex community of microbial species that plays a fundamental role in the health and functioning of the human digestive tract. The homeostasis of this community provides protection against pathogens (Belkaid and Harrison, 2017; Lin et al., 2021). However, the use of antibiotics can break up this ecosystem and cause dysbiosis. Intestinal dysbiosis is defined as a cutback of beneficial commensal bacteria and development of damaging commensal bacteria termed opportunistic pathogens or pathobionts (Nagao-Kitamoto and Kamada, 2017; Kitamoto et al., 2020; Wei et al., 2021). The dysbiotic gut microbiota can trigger the initiation of gastrointestinal diseases including the antibiotic-associated hemorrhagic colitis (AAHC). Hospitalized patients who receive treatment with antibiotics may develop AAHC due to the pathobiont Klebsiella oxytoca, a Gram-negative bacterium that resides in the human gut. Toxigenic K. oxytoca strains carry a gene cluster that codes for proteins that synthesize a cytotoxin known as tilivalline (TV), which is largely responsible for this disease (Dornisch et al., 2017). Unlike other toxins, TV is not a protein, but a pentacyclic pyrrolobenzodiazepine metabolite. The cytotoxin biosynthetic gene cluster is a part of a pathogenicity island (PAI) and is organized in two operons termed aroX and NRPS. The aroX operon is a 6.1-kbp region encoding five genes: aroX, dhbX, icmX, adsX, and hmoX. The NRPS operon is a 6.2-kbp region encoding three genes: npsA, thdA, and npsB (Schneditz et al., 2014; Dornisch et al., 2017; Tse et al., 2017). TV disrupts cell cycle progression due to the enhancement of nucleation and elongation of tubulin polymerization (Unterhauser et al., 2019). Furthermore, TV induces epithelial apoptosis and changes the expression and localization of the tight junction protein claudin-1. Consequently, the intestinal barrier function is impaired (Schneditz et al., 2014; Hering et al., 2019).

The regulation of the expression of the aroX and NRPS operons has not been studied. Pathogenic bacteria possess a myriad of transcription factors that control their virulence (Crofts et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2019; King et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2020; Ramamurthy et al., 2020; Wójcicki et al., 2021). The cAMP receptor protein (CRP) is one of the most important global regulators controlling the expression of many genes in bacteria. It has been associated with the regulation of virulence factors, pathogenicity islands, and enzymes involved in the metabolism of various enterobacterial species such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (De la Cruz et al., 2016, 2017; Xue et al., 2016; Berry et al., 2018; El Mouali et al., 2018; Ares et al., 2019). CRP consists of a homodimer, and its function depends on its binding to cAMP. When such interaction occurs, the conformation of CRP changes and this allows it to bind to the promoters on DNA in order to regulate transcriptional expression (Lindemose et al., 2014; Gunasekara et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2021). There are no studies on the role of the global regulator CRP in K. oxytoca. Nevertheless, in its close relative K. pneumoniae, CRP is a negative regulator of the capsular polysaccharide and a positive regulator of type 3 fimbriae (Ou et al., 2017; Panjaitan et al., 2019). In E. coli, CRP has more than 260 binding sites (Salgado, 2004) and controls the transcription of genes that code for proteins involved in a wide range of cellular processes, including its well-known role in the regulation of the lac operon, biofilm formation, iron uptake, antibiotic multidrug resistance, quorum sensing, shikimate pathway, and oxidative stress resistance (Jiang and Zhang, 2016; Uppal and Jawali, 2016; Ritzert et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020b; Kumar et al., 2021). Additionally, CRP is involved in catabolite repression and metabolism of carbon sources. For example, in the absence of some rapidly metabolizable carbon sources such as glucose, CRP activates adenylate cyclase, which leads to an increase in enzyme production involved in the use of alternative carbon sources, such as lactose (Salgado, 2004; Geng and Jiang, 2015; Liu et al., 2020a). Indeed, it was previously reported that culturing a cytotoxin-producing K. oxytoca strain in a lactose-containing medium increases the production of TV and consequently the cytopathic effect on epithelial cells (Tse et al., 2017).

In this study, we sought to investigate the role of CRP in the transcriptional control of the enzymes encoded by the aroX and NRPS operons in the cytotoxin-producing K. oxytoca strain MIT 09-7231 (Darby et al., 2014). In addition, we evaluated the expression of aroX and NRPS operons in different environmental growth conditions including utilization of various carbon sources. Furthermore, we investigated the role of CRP protein in the transcriptional regulation of aroX and NRPS operons. The regulatory effect of CRP in production of TV cytotoxin was also analyzed by cytotoxicity assays on HeLa cells. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study addressing the transcriptional regulation of the TV biosynthetic gene cluster, in which CRP acts as an activator.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

Klebsiella oxytoca strains and bacterial constructs used in this study are listed in Table 1. K. oxytoca MIT 09-7231 was used as the prototypic toxigenic strain and for construction of the isogenic Δcrp mutant (Darby et al., 2014). To determine gene expression of aroX and NRPS operons, different liquid bacteriological media were used: lysogeny broth (LB), tryptone soy broth (TSB), tryptone lactose broth (TLB), and Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with high glucose (4.5g/l). The transcription of aroX and npsA genes was analyzed under different environmental conditions in TLB medium at 37°C with shaking, and samples were harvested when an OD600nm of 1.6 was reached for RNA extraction. TLB medium was prepared as previously described [17g/l tryptone, 10g/l lactose, and 2.5g/l dipotassium hydrogen phosphate (Tse et al., 2017)]. TLB medium was supplemented with 0.2% glucose, 0.2% glycerol, 0.3M NaCl, 1.0mM EDTA, 5.0mM CaCl2, or 5.0mM MgCl2. In order to examine the effect of lactose on the transcription of aroX and npsA genes, tryptone broth (TB) was used and gene expression results were compared with those obtained from cultures in TLB medium. Antibiotics [200μg/ml (ampicillin), 50μg/ml (kanamycin), or 10μg/ml (tetracycline)] were added to culture media when necessary.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strain or plasmid | Description | References |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| K. oxytoca WT | Wild-type K. oxytoca strain MIT 09-7231 | Darby et al., 2014 |

| K. oxytoca Δcrp | K. oxytoca Δcrp::FRT | This study |

| K. oxytoca ΔnpsA | K. oxytoca ΔnpsA::FRT | This study |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) | F−ompT hsdSB (rB−, mB−) gal dcm (DE3) | Invitrogen |

| Plasmids | ||

| pTrc99Acrp | crp expression plasmid; ApR | Kurabayashi et al., 2017 |

| pTrc99K-CRP | crp expression plasmid; KmR | This study |

| pQE80crp | N-terminal His6-Crp overexpression plasmid; ApR | Kurabayashi et al., 2017 |

| pKD119 | pINT-ts derivative containing the λ Red recombinase system under an arabinose-inducible promoter, TcR | Datsenko and Wanner, 2000 |

| pKD4 | pANTsy derivative template plasmid containing the kanamycin cassette for λ Red recombination, ApR | Datsenko and Wanner, 2000 |

| pCP20 | Plasmid that shows temperature-sensitive replication and thermal induction of FLP synthesis, ApR, CmR | Datsenko and Wanner, 2000 |

Construction of Isogenic Mutants

K. oxytoca MIT 09-7231 was targeted for mutagenesis of crp and npsA genes by using the lambda-Red recombinase system (Datsenko and Wanner, 2000). Briefly, PCR fragments containing crp or npsA sequences flanking a kanamycin resistance gene were obtained by using gene-specific primer pairs (Table 2). Each purified PCR product was electroporated independently into competent K. oxytoca carrying the lambda-Red recombinase helper plasmid pKD119, whose expression was induced by the addition of L-(+)-arabinose (Sigma) at a final concentration of 1%. The mutations were confirmed by PCR and sequencing. Subsequently, the FRT-flanked kanamycin cassettes were excised from both Δcrp and ΔnpsA mutant strains after transformation with pCP20 plasmid, as previously described (Datsenko and Wanner, 2000).

Table 2.

Primers used in this study.

| Primer | Sequence (5"- 3") | Target gene |

|---|---|---|

| For Gene Deletion | ||

| crp-H1P1 | TATAACAGAGGATAACCGCGCATGGTGCTTGGCAAACCGCAAACATGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTCG | crp |

| crp-H2P2 | GCAATACGCCGTTTTACCGACTTAACGGGTACCGTAGACGACGATCATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG | |

| npsA-H1P1 | CTAATTCTCCAGGAGAGAGTGATGACGCATTCAGCATATGTCTATTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTCG | npsA |

| npsA-H2P2 | GTTGCTCAACGTTGTCCATATTTACACCTGCTCCAGTAAAGAATTCATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG | |

| For Site-Directed Mutagenesis | ||

| aroX-npsA-CRPBox-F | TGCCGCCAGCTTACCACAGGATGCCCTCGGGCAAACACCGCAAAA | aroX-npsA |

| aroX-npsA-CRPBox-R | TTTTGCGGTGTTTGCCCGAGGGCATCCTGTGGTAAGCTGGCGGCA | |

| For Mutant Characterization | ||

| crp-MC-F | CGGCACCCGGAGATAGCTTA | crp |

| crp-MC-R | AGGGGAAAACAAAAACGGCG | |

| npsA-MC-F | TTTGCGGTGTTTTCTTAGAAGCA | npsA |

| npsA-MC-R | CGGGTTAATCGCCTCTGAATG | |

| FOR qPCR | ||

| aroX-F | TGTTGCCTGCAAGATTGACG | aroX |

| aroX-R | ATGTGTGAACGGCCAAAACG | |

| dhbX-F | ATGCGGCCAATCTGATGATG | dhbX |

| dhbX-R | AGCCCCAGAGCATAGGTAAATG | |

| icmx-F | TGATTGTCTGCGGCGTTTAC | icmX |

| icmX-R | GCTAGACGATGCTTTTCTTCGG | |

| adsX-F | TGCACATTGAACGGCAAGAC | adsX |

| adsX-R | ATCGAAGTGCAGGTTTCGTG | |

| hmoX-F | TCGCATGCCAAAGATTTCGC | hmoX |

| hmoX-R | ATGAGCTTGACGCGTTCAAC | |

| npsA-F | AAATACGTGGCTTCCGCATC | npsA |

| npsA-R | TCCTGCGTGACATAACAAGC | |

| thdA-F | TGGACAACGTTGAGCAACAG | thdA |

| thdA-R | TGCTTACCATTGACGCCAAC | |

| npsB-F | TGAGCATTTGCAGCTGGTTC | npsB |

| npsB-R | ATGCGTGGCAACTTTGTGTG | |

| crp-F | TGCTGAACCTGGCAAAACAG | crp |

| crp-R | ATTTTCAGGATGCGGCCAAC | |

| rrsH-F | CAGGGGTTTGGTCAGACACA | rrsH |

| rrsH-R | GTTAGCCGGTGCTTCTTCTG | |

| For EMSA | ||

| aroX-npsA-F | TCTCTCACTCGAAATTTAACAGGT | aroX-npsA |

| aroX-npsA-R | TCTCTCCTGGAGAATTAGGAACG | |

| estA2-F | CCAGAGGCGGTCGAACTC | estA2 |

| estA2-R | ATTACCTCCGAAACACGTCGT | |

| eltA-F | CCAGCGATAAAGTCTGTAAATACGG | eltA |

| eltA-R | TATCATACAAGAAGACAATCCGGA | |

The sequence corresponding to the template plasmid pKD4 is underlined.

Construction of ΔCRP-Box Mutant Probe by Site-Directed Mutagenesis

A fragment with targeted mutations in the putative CRP-Box of intergenic regulatory region of the divergent aroX and npsA genes was generated using overlapping PCR (Ho et al., 1989) with specific primers (Table 2). Two fragments were generated separately in a first round of PCR: one with the 5΄ half and other with the 3΄ half of the intergenic regulatory region of aroX and npsA genes including the overlapping mutated region. Subsequently, the two fragments were mixed and amplified in a second round of PCR. DNA sequencing was carried out to verify the introduction of the point mutations.

Construction of pTrc99K-CRP Plasmid

The pTrc99K-CRP plasmid was constructed for complementation experiments by subcloning the crp gene from the pTrc99Acrp plasmid (Kurabayashi et al., 2017). The pTrc99Acrp vector was digested with NcoI and BamHI, and the fragment corresponding to the crp gene was then purified and ligated into pTrc99K previously digested with the same restriction enzymes. The identity of the insert was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

RNA Extraction and Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from bacteria grown under different culture conditions using the hot phenol method (Jahn et al., 2008; Ares, 2012), with some modifications. Briefly, after the lysate was obtained, an equal volume of phenol-saturated water was added, mixed, and incubated at 65°C for 5min. The samples were chilled on ice and centrifuged at 19,000 × g for 10min at 4°C. The aqueous layer was transferred to a microtube, RNA was precipitated with cold ethanol, and it was incubated at −70°C overnight.

The RNA was pelleted by centrifugation at 19,000 x g for 10min at 4°C. Pellets were washed with cold 70% ethanol and centrifuged at 19,000 × g for 5min at 4°C. After careful removal of the ethanol, the pellets were air-dried for 15min in a Centrifugal Vacuum Concentrator 5,301 (Eppendorf). The pellets were resuspended in DEPC-treated water. Purification of RNA was performed using the TURBO DNA-free kit (Ambion, Inc.). Quality of RNA was assessed using the NanoDrop ONE (Thermo Scientific) and with a bleach denaturing 1.5% agarose gel, as previously described (Aranda et al., 2012). cDNA was synthesized using 1 μg of RNA, 5pmol/μl of random hexamer primers, and 200U/μl of RevertAid M-MulV-RT (Reverse transcriptase of Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus; Thermo Scientific).

Quantitative real-time PCR was performed in a LightCycler 480 instrument (Roche) to quantify the gene expression levels. Specific primers (Table 2) were designed using the Primer3Plus software1 (Untergasser et al., 2007). For LightCycler reactions, a master mix of the following components was prepared: 2.0 μl of PCR-grade water, 0.5 μl (10 μM) of forward primer, 0.5 μl (10 μM) of reverse primer, 5 μl of 2x Master Mix, and 2.5 μl of cDNA (~50ng). A multiwell plate containing all samples was loaded into the LightCycler 480 instrument. Amplification was performed in triplicate wells for each sample analyzed from three independent experiments. In each set of reactions, 16S rRNA (rrsH) was used as a reference gene for normalization of the cDNA amount. Real-time PCR analysis was performed using the following optimized assay conditions: (1) denaturation program (95°C for 10min); amplification and quantification programs were repeated for 45cycles (95°C for 10s, 59°C for 10s, 72°C for 10s with a single fluorescence measurement), (2) melting curve program (95°C for 10s, 65°C for 1min with continuous fluorescence measurement at 97°C), and (3) a cooling step at 40°C for 10s. The absence of contaminating DNA was tested by the lack of amplification products after 45 qPCR cycles using RNA as template. Control reactions with no RNA template and with no reverse transcriptase enzyme were run in all experiments. The relative gene expression was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001; Schmittgen and Livak, 2008). To ensure that 16S rRNA (rrsH) was an optimal reference gene for normalization of qPCR, absolute quantification was performed by obtaining a standard curve according to 10-fold dilutions of K. oxytoca 09–7231 chromosomal DNA (103, 104, 105, 106, and 107 theoretical copies). Ct values were interpolated to standard curve to obtain gene expression (gene copies per μg RNA). Expression of 16S rRNA (rrsH) gene remained unaffected in all conditions tested (Supplementary Figure S1).

Protein Purification

The His6-CRP expression plasmid pQE80crp (Kurabayashi et al., 2017) was electroporated into competent E. coli BL21 (DE3). Bacteria containing recombinant plasmid were grown at 37°C to an OD600nm of 0.5 in LB; 1.0mM IPTG was then added and cultured for 3h. Cells were then pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in urea buffer (8M urea, 100mM Na2HPO4, and 10mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) and lysed by sonication. The lysate was centrifuged, and the supernatant was filtered through Ni-NTA agarose column (Qiagen) pre-equilibrated with urea buffer. After washing with buffer containing 50mM imidazole (200ml), the protein was eluted with 500mM imidazole (10ml). Fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford procedure. Aliquots of the purified protein were stored at −70°C.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays

To evaluate CRP binding to the promotor sequence, a 448-bp DNA probe containing the intergenic regulatory region of the divergent aroX and npsA genes was used. In addition, the probe ΔCRP-Box containing the mutation in the putative CRP-binding site on the intergenic regulatory region of the divergent aroX and npsA genes was employed. DNA probes from the regulatory region of the enterotoxigenic E. coli estA2 and eltA genes were used as positive and negative controls (Haycocks et al., 2015). The binding reaction was performed with 100ng of DNA probes and increasing concentrations of purified His6-CRP with or without 200μM cAMP (Hirakawa et al., 2020) in a 20μl reaction mixture containing H/S 10X gel-shift binding buffer (400mM HEPES, 80mM MgCl2, 500mM KCl, 10mM DTT, 0.5% NP40, and 1mg/ml BSA, De la Cruz et al., 2007). Samples were incubated for 20min at room temperature and then separated by electrophoresis in 6% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gels using 0.5X Tris-borate-EDTA buffer at 4°C. The DNA bands were stained with ethidium bromide and visualized under UV light.

Cytotoxicity Assays

HeLa cell line (ATCC CCL-2) was used to determine cytotoxic activity as previously described (Darby et al., 2014). Approximately 1×106 cells were suspended in 900μl of DMEM high glucose (4.5g/l; Invitrogen) with 10% FBS (Gibco) and seeded into 24-well cell culture plates (Costar). To investigate cytotoxin production in the K. oxytoca strains (wild type, Δcrp, Δcrp pTrc99K-CRP, and ΔnpsA), 100μl of bacterial supernatants was filtered through a PVDF 0.22-μm sterile Millex-GV filter (Merck Millipore) and added to the wells containing HeLa cells. After 48h of incubation at 37°C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere, the cells were visualized using a Nikon TE300 inverted microscope at 10X magnification. Cytotoxin production was defined as >50% cell rounding and detachment and<50% confluency, as compared to the negative control samples [(TLB medium only or supernatant of the non-toxigenic K. oxytoca ΔnpsA strain (Schneditz et al., 2014; Dornisch et al., 2017; Tse et al., 2017)]. Negative control samples had a monolayer with minimal cell rounding or detachment and>80% confluency.

The LDH Cytotoxicity Assay Kit (Invitrogen) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions to measure lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) released from HeLa cells after damage of plasma membrane integrity. 1×104 HeLa cells were cultivated in 100μl DMEM high glucose (4.5g/l; Invitrogen) with 10% FBS (Gibco), seeded into 96-well flat-bottom culture plates (Costar), and incubated at 37°C under a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 48h. Subsequently, the medium was removed, and the cells washed with PBS. Then, 10μl of negative control (PBS), culture medium control (TLB), positive control (lysis buffer), and filtered bacterial supernatants (wild type, Δcrp, Δcrp pTrc99K-CRP, and ΔnpsA) as described before was added to DMEM medium without FBS for 48h. After treatment, an aliquot of 50μl each sample medium was transferred to a new 96-well plate, and kit solutions were added into each well. The absorbance was measured at 490nm and 680nm with a spectrophotometer (Multiskan Ascent, Thermo Scientific). All samples were tested in triplicate on three independent biological replicates, and the mean results were expressed as LDH cytotoxicity by subtracting the 680nm absorbance background value from the 490nm absorbance value.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, United States). Data represent the mean±standard deviation (SD). The mean differences were determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s comparison test. Values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Expression of aroX and NRPS Operons Is Enhanced by Growth in TLB Medium

To determine the optimal conditions of expression of the aroX and NRPS operons of K. oxytoca MIT 09-7231, the bacteria were cultivated in different culture media, such as LB, TSB, TLB, and DMEM transcription analyzed by RT-qPCR. The conventional LB medium was used as a reference to determine the basic levels of expression of genes encoded by the aroX and NRPS operons. The lowest levels of transcription of the aroX and NRPS operons occurred when the bacteria were cultivated in DMEM; this was rather surprising since expression of most virulence factors of pathogenic E. coli strains occurs upon growth in DMEM (Leverton and Kaper, 2005; Platenkamp and Mellies, 2018). In comparison with the growth of MIT 09-7231 in LB, the expression of aroX and NRPS operons of MIT 09-7231 cultivated in TSB and TLB media enhanced ~5- and~150-fold, respectively (Figure 1A). Unlike TSB medium, TLB contains lactose instead of soy. The expression levels of TV genes were very similar in the different culture media, supporting the notion that they are genetically organized in operons. Since aroX and npsA are the first genes of the aroX and NRPS operons, respectively, only the expression of these two genes was evaluated throughout the study. When K. oxytoca MIT 09-7231 was grown in TLB at 37°C for 12h, the highest levels of expression of aroX and npsA genes occurred at 9h and were maintained for 12h, which corresponds to stationary growth phase (Figure 1B). Our data indicate that growth in TLB medium, which contains lactose, favors the expression of K. oxytoca aroX and NRPS operons during stationary growth phase.

Figure 1.

Effect of environmental cues on aroX and NRPS operons expression. (A) Fold change expression detected by RT-qPCR of aroX and NRPS operons of K. oxytoca compared to LB. Bacterial cultures were grown at 37°C for 9h in different culture media: lysogenic broth (LB), tryptone soy broth (TSB), tryptone lactose broth (TLB), and Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with high glucose (4.5g/l). (B) Transcription of aroX and npsA genes during growth phases. (C) Transcription of aroX and npsA genes at stationary phase (OD600nm=1.6) at 37°C under different environmental conditions determined by RT-qPCR. (D) Growth curves of wild-type K. oxytoca in TLB medium at 37°C for 12h supplemented with glucose (GLU, 0.2%), glycerol (GLY, 0.2%), sodium chloride (NaCl, 0.3M), and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA, 1.0mM, supplemented or not supplemented with 5.0mM CaCl2/MgCl2). 16S rRNA was used as a reference gene for normalization of expression. These graphs represent the mean of three independent experiments performed in triplicate with standard deviations. Statistically significant with respect to bacteria grown in LB medium (A) or with respect to bacteria grown after 1h post-inoculation in TLB medium (B) or with respect to bacteria grown in non-supplemented TLB medium (C): **p<0.001. All values of p were calculated using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s comparison test.

Expression of aroX and npsA Genes Is Differentially Regulated by Nutritional and Environmental Factors

The influence of nutritional factors in the expression of genes involved in TV biosynthesis was quantified by RT-qPCR when K. oxytoca was grown in TLB supplemented with 0.2% glucose, 0.2% glycerol, 0.3M sodium chloride, and 1.0mM EDTA. The expression of aroX and npsA genes was repressed (~4-fold) and activated (~3-fold) by glucose and glycerol, respectively (Figure 1C). In high osmolarity (0.3M NaCl), the transcription of aroX and npsA decreased ~8-fold (Figure 1C). Transcription of these genes required divalent cations because the addition of EDTA dramatically diminished their expression (~50-fold), and this effect was partially and fully reverted by the addition of CaCl2 and MgCl2, respectively (Figure 1C). Of note, depletion of divalent cations by the addition of EDTA to the culture medium affected negatively bacterial growth (Figure 1D). This effect was reversed by the addition of CaCl2 and MgCl2 to TLB containing EDTA (Figure 1D). The data indicate that glucose, high osmolarity, and depletion of divalent cations from the growth medium repress aroX and npsA genes.

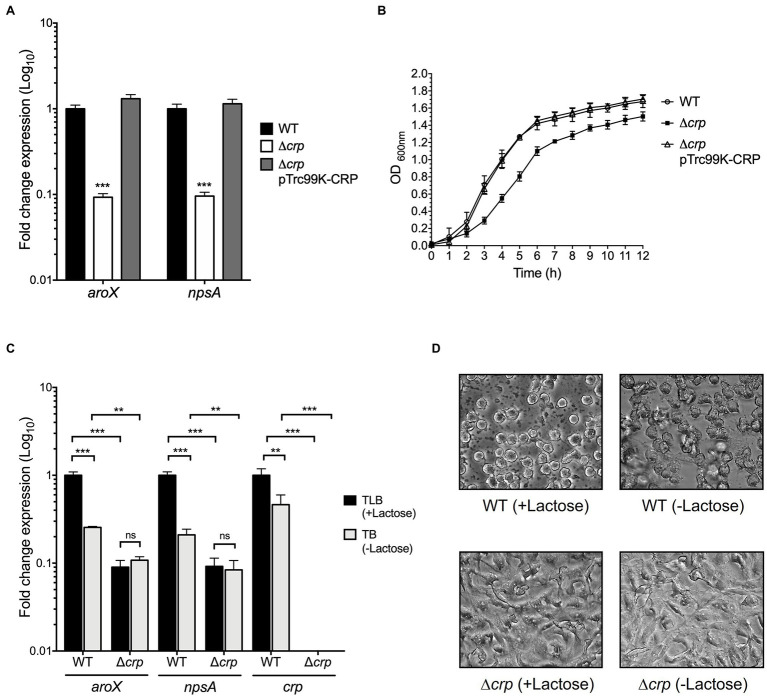

CRP Activates the Expression of aroX and npsA Genes

As described above, carbon sources such as lactose, glucose, and glycerol affect the transcription of aroX and npsA genes. CRP is a global regulator that senses the fluctuations of carbon sources and controls the transcription of some enzymes involved in metabolite biosynthesis (Bai et al., 2011; Gao et al., 2012; Soberón-Chávez et al., 2017; Jeong et al., 2021). Hence, we sought to investigate the role of CRP in the regulation of aroX and npsA genes. Growth rates and expression of these genes in the wild type and its derivative ∆crp isogenic mutant were compared after growth in TLB at stationary phase (OD600nm=1.6) by RT-qPCR. In the absence of CRP, growth was significantly attenuated and expression levels of both aroX and npsA genes were diminished ~10-fold. Both, growth rate and expression were reversed by the complementation of this mutant with the pTrc99K-CRP plasmid (Figures 2A,B). These results indicate that CRP positively regulates expression of aroX and npsA genes.

Figure 2.

Regulatory activity of CRP in expression of aroX and npsA genes. (A) Determination of transcriptional expression by RT-qPCR of aroX and npsA genes of wild-type K. oxytoca, Δcrp, and Δcrp pTrc99K-CRP in TLB medium at stationary phase (OD600nm=1.6) at 37°C. (B) Growth curves of wild-type K. oxytoca, Δcrp, and Δcrp pTrc99K-CRP, in TLB medium at 37°C. Bacterial cultures were grown for 12h. (C) Transcription of aroX, npsA, and crp genes at stationary phase (OD600nm=1.6) at 37°C determined by RT-qPCR in TLB (medium with lactose), and TB (medium without lactose) at 37°C for 12h. These graphs represent the mean of three independent experiments performed in triplicate with standard deviations. (D) HeLa cell culture inoculated with supernatants recovered from wild-type and Δcrp strains grown in TLB (medium with lactose) and TB (medium without lactose). Results represent the mean of three independent experiments performed in triplicate with standard deviations. Statistically significant with respect to wild-type strain (A) or with respect to bacteria grown in TLB medium (B): **p<0.01; ***p<0.001. All Values of p were calculated using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s comparison test.

Effect of Lactose on CRP-Mediated aroX and npsA Expression

We wanted to know whether the regulation exerted by lactose on TV genes implicated CRP. Thus, we quantified the transcription of aroX and npsA genes in the wild-type and ∆crp mutant strains growing in TLB (medium with lactose) and TB (tryptone broth), which is TLB without lactose. Growth of the wild-type strain in the absence of the lactose decreased TV gene transcription by ~5-fold (Figure 2C). This effect was CRP-dependent because transcription of aroX and npsA was not altered in the ∆crp mutant strain (Figure 2C). As an expression control of a lactose-regulated gene, we quantified the transcription of crp in the wild-type growing in the presence of lactose and found ~2-fold increase in expression. We hypothesized that lactose is involved in the CRP-dependent aroX and npsA transcription; thus, we analyzed TV-mediated cytotoxicity on HeLa epithelial cells using the supernatants of the wild-type and ∆crp mutant cultures grown in the presence and absence of lactose (Figure 2D). The supernatant recovered of the wild-type strain grown in TLB (with lactose) presented a higher cytotoxic effect on HeLa cells than the supernatant obtained from the wild-type strain grown in TB (without lactose). The supernatants from the ∆crp mutant grown with/without lactose caused a slight cytotoxic effect on HeLa cells (Figure 2D). These data support our hypothesis that lactose induces CRP-mediated aroX and npsA genes transcription and consequently triggers TV-mediated cytotoxicity on HeLa epithelial cells.

CRP Binds to the Intergenic Region of aroX and npsA Genes

Sequence analysis of the intergenic region of aroX and npsA genes identified a putative CRP-binding site (Figure 3A). This sequence (CGTGA-N6-TCTAA) shared 7 of 10bp with the E. coli consensus sequence (TGTGA-N6-TCACA; Figure 3B). Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) were performed using a recombinant His6-CRP protein and DNA probes. Indeed, CRP bound to the aroX-npsA intergenic region since CRP-DNA complexes were observed using 100nM of His6-CRP and this DNA-binding activity was dependent of the presence of cAMP (200μM; Figure 3C). To demonstrate whether the putative CRP-box was required for CRP binding to the aroX-npsA intergenic region, site-directed mutagenesis of the CRP-box was performed (Figure 3B). CRP did not bind to the aroX-npsA intergenic region containing the mutation of CRP-Box (Figure 3D). As positive and negative controls, estA2 and eltA regulatory regions were used (Figures 3E,F; Haycocks et al., 2015). These results clearly show that CRP binds directly to the aroX-npsA intergenic region through recognition of a specific binding site.

Figure 3.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay showing binding of CRP-cAMP to the intergenic region of aroX and npsA genes. (A) Genetic organization of the aroX and NRPS operons and putative CRP-binding sites located in the intergenic regulatory region. The putative CRP-binding site is indicated with bold and boxed letters. (B) The intergenic region of K. oxytoca aroX and npsA genes contains a CRP-Box similar to the CRP-binding consensus sequence found in E. coli. An altered CRP-Box was generated to determine CRP binding. Bases matching the consensus sequence are bold, and mutated bases are shown in red. EMSA experiments were conducted to determine the binding of purified recombinant His6-CRP protein to the corresponding DNA probe from the wild-type intergenic region of aroX and npsA genes (C) and from the intergenic region of aroX and npsA containing the mutation in the putative CRP-Box (D). DNA probes from the estA2 (E) and eltA (F) regulatory regions were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. 100ng of DNA probe of each regulatory region was mixed and incubated with increasing concentrations (μM) of purified recombinant His6-CRP protein (CRP) in the presence or absence of 200μM of cAMP. Free DNA and CRP-DNA complex stained with ethidium bromide are indicated.

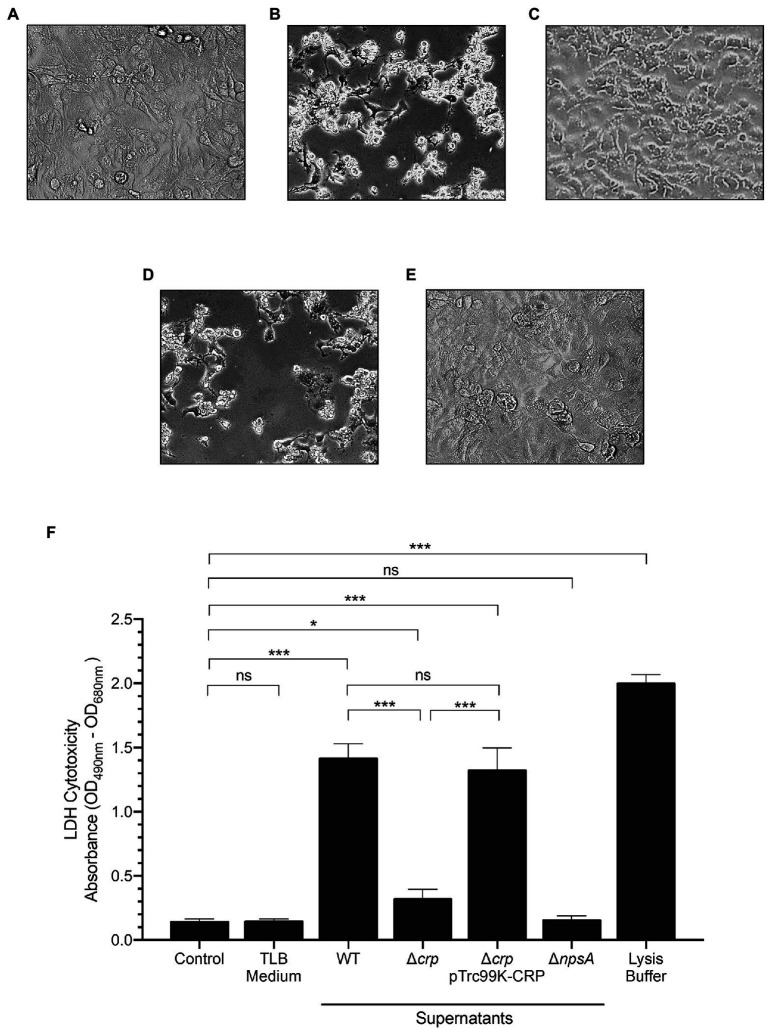

CRP Induces TV-Mediated Cytotoxicity on Epithelial Cells

To corroborate the role of CRP on the aroX and npsA genes transcription, we determined the TV-mediated cytotoxicity on epithelial cells using the supernatants from K. oxytoca wild type, ∆crp mutant, and complemented ∆crp mutant. Cytotoxicity was severely affected in the ∆crp mutant as compared to the wild type and the complemented mutant. As expected, the supernatant of the non-toxigenic ∆npsA strain did not cause any cytotoxic effect on HeLa cells (Figure 4A). Further, the LDH release activity assay showed that wild-type strain supernatant induced death of HeLa cells (~14-fold) as compared to the PBS control. In contrast, the ∆crp mutant supernatant significantly reduced the death of HeLa cells by ~6-fold as compared to the wild-type strain supernatant. Levels of released LDH by HeLa cells treated with the supernatant of the complemented ∆crp mutant were similar to that of wild-type strain supernatant. Neither the TLB medium nor the non-toxigenic ∆npsA supernatant induced death of HeLa cells (Figure 4B). These phenotypic data support the role of CRP global regulator as a transcriptional activator of genes involved in the K. oxytoca TV biosynthesis.

Figure 4.

Cytotoxicity of K. oxytoca Δcrp mutant strain. HeLa cell culture inoculated with: (A) TLB medium as control, and (B) wild-type (C) Δcrp (D) Δcrp pTrc99K-CRP, and (E) ΔnpsA K. oxytoca supernatants. (F) HeLa cells were treated with TLB medium, and K. oxytoca supernatants (wild-type, Δcrp, Δcrp pTrc99K-CRP, and ΔnpsA) for 48h. Following treatment, aliquots were obtained for measurement of extracellular LDH. Minimal and maximal measurable LDH release was determined by incubating cells with PBS (control), and lysis buffer, respectively. Statistically significant: *p<0.05; ***p<0.001; ns: not significant. All values of p were calculated using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s comparison test.

Discussion

K. oxytoca is a pathobiont of the intestinal microbiota that can produce TV cytotoxin (Beaugerie et al., 2003; Högenauer et al., 2006; Zollner-Schwetz et al., 2015; Glabonjat et al., 2021). After penicillin treatment, alteration of the enteric microbiota occurs, and overgrowth of K. oxytoca is originated in the colon causing a severe dysbiosis (Schneditz et al., 2014; Hajishengallis and Lamont, 2016; Dornisch et al., 2017; von Tesmar et al., 2018; Alexander et al., 2020). The imbalance in the gut microbiota and the production of TV cytotoxin result in AAHC (Högenauer et al., 2006; Unterhauser et al., 2019). The aroX and NRPS operons encode the proteins involved in the biosynthesis of TV and are clustered in a PAI that is only present in the K. oxytoca toxigenic strains (Schneditz et al., 2014; Dornisch et al., 2017). In this study, we analyzed the expression of aroX and NRPS operons in strains growing in various culture media since previous work has determined that nutritional components are environmental stimuli that trigger a differential expression of genes related to bacterial virulence (Blair et al., 2013; De la Cruz et al., 2017; Han et al., 2017; Ares et al., 2019; Soria-Bustos et al., 2020; Jiang et al., 2021). Our results showed that TLB culture medium significantly enhanced the expression of the aroX and NRPS operons, in agreement with a previous report in which the production of TV significantly increased in the toxigenic strain K. oxytoca MH43-1 when the bacterium was grown in TLB as compared with TSB and LB (Tse et al., 2017). A previous report showed that TV production reaches maximum levels at late exponential and stationary growth phases (Joainig et al., 2010). We determined the expression of aroX and npsA genes during 12h of growth in TLB medium and, as expected, transcription attained maximum levels at 9h and remained as such until 12h of growth, which corresponds to stationary growth phase. In addition to the effect of nutritional components from different culture media being analyzed, we evaluated the influence of other environmental stimuli such as glucose, glycerol, osmolarity, and divalent cations. Regarding the role of carbon source in transcription, glucose and glycerol repressed and activated the aroX and npsA gene expression, respectively. It was reported that glucose and glycerol have antagonistic activities in the control of cAMP production, which is necessary for the regulatory activity of the CRP protein (Soberón-Chávez et al., 2017). While glucose inhibits, glycerol induces cAMP synthesis (Deutscher et al., 2006; Fic et al., 2009; Pannuri et al., 2016). Glucose concentration is higher in the small intestine, while glycerol is produced abundantly by enteric microorganisms residing in the colon (Yuasa et al., 2003; Fujimoto et al., 2006; Ohta et al., 2006; De Weirdt et al., 2010). Our results suggest that the genes involved in TV biosynthesis could be expressed in the glycerol-rich colon environment under regulation of CRP. We found here that sodium chloride repressed aroX and npsA gene expression. Previously, it was reported that when Listeria monocytogenes grows in the presence of high concentrations of sodium chloride, some genes that code for metabolic enzymes and virulence factors are repressed (Bae et al., 2012). In enterotoxigenic E. coli, the addition of sodium chloride to culture medium also repressed transcription of the coli surface antigen CS3 (Ares et al., 2019). In contrast, high osmolarity increases the gene expression of the enterotoxigenic E. coli Longus pilus (De la Cruz et al., 2017). The ubiquitous divalent cations magnesium and calcium are important nutrients required by bacteria for growth and cell maintenance. The effects of calcium and magnesium can be highlighted in physio-chemical interactions, gene regulation, and bio-macromolecular structural modification (Groisman et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2019). Moreover, it has been reported that divalent cations are involved in transcriptional regulation of virulence factors in pathogenic E. coli, Aeromonas hydrophila, P. aeruginosa, Vibrio cholerae, and Yersinia enterocolitica (Fälker et al., 2006; Bilecen and Yildiz, 2009; Vilches et al., 2009; Anderson et al., 2010; De la Cruz et al., 2017; Ares et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020c). In our study, the presence of calcium and magnesium divalent cations was required for aroX and npsA gene expression.

This work underlines for the first time, the regulatory activity of CRP in the transcription of genes involved in TV biosynthesis. The K. oxytoca CRP protein is homologous to other CRP proteins from several enteropathogens such as K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and S. enterica. The absence of CRP exhibited a growth defect in both exponential and stationary phases, as observed in Vibrio vulnificus (Kim et al., 2013), E. coli (Basak et al., 2014), K. pneumoniae (Ou et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2018), and Haemophilus parasuis (Jiang et al., 2020). These observations are in accordance with previous reports that explain how growth fitness is affected by the crp deletion, which produces fluctuations of metabolic gene expression and alterations of carbon metabolites, α-ketoacids, cAMP, and amino acids that promote proper coordination of protein biosynthesis machinery during metabolism (Klumpp et al., 2009; Berthoumieux et al., 2013; You et al., 2013; Pal et al., 2020). CRP is a central regulator of carbon metabolism and has been implicated as an important facilitator of host colonization and virulence in many bacterial pathogens, including K. pneumoniae (Xue et al., 2016; Lin et al., 2018; Panjaitan et al., 2019). In this study, we demonstrated that CRP positively regulates the expression of the aroX and NRPS operons and plays a regulatory role in response to lactose as was previously demonstrated in E. coli and K. pneumoniae, where lactose acts as glycerol inducing the augmentation of cAMP (Deutscher et al., 2006; Panjaitan et al., 2019). We also showed that CRP directly activates the expression of aroX and npsA genes by binding to their intergenic regulatory region and that cAMP is indispensable for this DNA-binding activity.

Cytotoxic effects of toxigenic K. oxytoca strains have been previously reported (Minami et al., 1989, 1994; Higaki et al., 1990; Beaugerie et al., 2003; Darby et al., 2014; Schneditz et al., 2014; Tse et al., 2017; Paveglio et al., 2020). We found that the Δcrp mutant strain was remarkably less cytotoxic than the wild-type strain. This was due to downregulation of the TV biosynthetic aroX and NRPS operons and reduced TV production in the absence of CRP.

Conclusion

This study underscores the role of the CRP-cAMP signaling pathway in the activation of genes involved in TV biosynthesis of toxigenic K. oxytoca and provides clues about the intestinal signals that trigger CRP-mediated TV production.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author Contributions

DR-V, MC, and MA conceived and designed the study. DR-V, NL-M, JS-B, JM-C, RG-U, RR-R, and LG-M performed the experiments. DR-V, SR-G, JG-M, HH, JF, MC, and MA analyzed the data. DR-V, JAG, MC, and MA wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

DR-V was supported by pre-doctoral fellowships from CONACYT (734002) and IMSS (99097641). This paper constitutes the fulfillment of DR-V’s requirement for the PhD Graduate Program in Biomedicine and Molecular Biotechnology, National Polytechnic Institute (IPN), Mexico. The authors thank J. David García for his help with CRP protein purification.

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2021.743594/full#supplementary-material

Expression of reference gene (rrsH) under the different conditions tested in this study. Panels show the expression of reference gene in different: (A) growth conditions, (B) growth phases, (C) environmental cues, (D) K. oxytoca strains, and (E) growth culture medium with or without lactose. Quantification of expression is showed as rrsH (16S rRNA) copies per microgram of RNA.

References

- Alexander E. M., Kreitler D. F., Guidolin V., Hurben A. K., Drake E., Villalta P. W., et al. (2020). Biosynthesis, mechanism of action, and inhibition of the enterotoxin Tilimycin produced by the opportunistic pathogen Klebsiella oxytoca. ACS Infect. Dis. 6, 1976–1997. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.0c00326, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson G. G., Yahr T. L., Lovewell R. R., O’Toole G. A. (2010). The Pseudomonas aeruginosa magnesium transporter MgtE inhibits transcription of the type III secretion system. Infect. Immun. 78, 1239–1249. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00865-09, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aranda P. S., LaJoie D. M., Jorcyk C. L. (2012). Bleach gel: A simple agarose gel for analyzing RNA quality. Electrophoresis 33, 366–369. doi: 10.1002/elps.201100335, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ares M. (2012). Bacterial RNA isolation. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2012, 1024–1027. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot071068, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ares M. A., Abundes-Gallegos J., Rodríguez-Valverde D., Panunzi L. G., Jiménez-Galicia C., Jarillo-Quijada M. D., et al. (2019). The coli surface antigen CS3 of Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli is differentially regulated by H-NS, CRP, and CpxRA global regulators. Front. Microbiol. 10:1685. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae D., Liu C., Zhang T., Jones M., Peterson S. N., Wang C. (2012). Global gene expression of Listeria monocytogenes to salt stress. J. Food Prot. 75, 906–912. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-11-282, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai G., Schaak D. D., Smith E. A., McDonough K. A. (2011). Dysregulation of serine biosynthesis contributes to the growth defect of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis crp mutant. Mol. Microbiol. 82, 180–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07806.x, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basak S., Geng H., Jiang R. (2014). Rewiring global regulator cAMP receptor protein (CRP) to improve E. coli tolerance towards low pH. J. Biotechnol. 173, 68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.01.015, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaugerie L., Metz M., Barbut F., Bellaiche G., Bouhnik Y., Raskine L., et al. (2003). Klebsiella oxytoca as an agent of antibiotic-associated hemorrhagic colitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 1, 370–376. doi: 10.1053/S1542-3565(03)00183-6, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belkaid Y., Harrison O. J. (2017). Homeostatic immunity and the microbiota. Immunity 46, 562–576. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.04.008, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry A., Han K., Trouillon J., Robert-Genthon M., Ragno M., Lory S., et al. (2018). cAMP and Vfr control Exolysin expression and cytotoxicity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa taxonomic outliers. J. Bacteriol. 200:e00135-18. doi: 10.1128/JB.00135-18, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthoumieux S., de Jong H., Baptist G., Pinel C., Ranquet C., Ropers D., et al. (2013). Shared control of gene expression in bacteria by transcription factors and global physiology of the cell. Mol. Syst. Biol. 9:634. doi: 10.1038/msb.2012.70, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilecen K., Yildiz F. H. (2009). Identification of a calcium-controlled negative regulatory system affecting Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation. Environ. Microbiol. 11, 2015–2029. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01923.x, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair J. M. A., Richmond G. E., Bailey A. M., Ivens A., Piddock L. J. V. (2013). Choice of bacterial growth medium alters the transcriptome and phenotype of Ssalmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium. PLoS One 8:e63912. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063912, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crofts A. A., Giovanetti S. M., Rubin E. J., Poly F. M., Gutiérrez R. L., Talaat K. R., et al. (2018). Enterotoxigenic E. coli virulence gene regulation in human infections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 115, E8968–E8976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1808982115, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darby A., Lertpiriyapong K., Sarkar U., Seneviratne U., Park D. S., Gamazon E. R., et al. (2014). Cytotoxic and pathogenic properties of Klebsiella oxytoca isolated from laboratory animals. PLoS One 9:e100542. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100542, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datsenko K. A., Wanner B. L. (2000). One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97, 6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la Cruz M. Á., Fernández-Mora M., Guadarrama C., Flores-Valdez M. A., Bustamante V. H., Vázquez A., et al. (2007). LeuO antagonizes H-NS and StpA-dependent repression in Salmonella enterica ompS1. Mol. Microbiol. 66, 727–743. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05958.x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la Cruz M. A., Morgan J. K., Ares M. A., Yáñez-Santos J. A., Riordan J. T., Girón J. A. (2016). The two-component system CpxRA negatively regulates the locus of enterocyte effacement of Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli involving σ(32) and Lon protease. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 6:11. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2016.00011, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la Cruz M. A., Ruiz-Tagle A., Ares M. A., Pacheco S., Yáñez J. A., Cedillo L., et al. (2017). The expression of longus type 4 pilus of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli is regulated by LngR and LngS and by H-NS, CpxR and CRP global regulators. Environ. Microbiol. 19, 1761–1775. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13644, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Weirdt R., Possemiers S., Vermeulen G., Moerdijk-Poortvliet T. C. W., Boschker H. T. S., Verstraete W., et al. (2010). Human faecal microbiota display variable patterns of glycerol metabolism. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 74, 601–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2010.00974.x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutscher J., Francke C., Postma P. W. (2006). How phosphotransferase system-related protein phosphorylation regulates carbohydrate metabolism in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70, 939–1031. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00024-06, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dornisch E., Pletz J., Glabonjat R. A., Martin F., Lembacher-Fadum C., Neger M., et al. (2017). Biosynthesis of the Enterotoxic Pyrrolobenzodiazepine natural product Tilivalline. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 14753–14757. doi: 10.1002/anie.201707737, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Mouali Y., Gaviria-Cantin T., Sánchez-Romero M. A., Gibert M., Westermann A. J., Vogel J., et al. (2018). CRP-cAMP mediates silencing of Salmonella virulence at the post-transcriptional level. PLoS Genet. 14:e1007401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007401, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fälker S., Schmidt M. A., Heusipp G. (2006). Altered Ca(2+) regulation of Yop secretion in Yersinia enterocolitica after DNA adenine methyltransferase overproduction is mediated by Clp-dependent degradation of LcrG. J. Bacteriol. 188, 7072–7081. doi: 10.1128/JB.00583-06, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fic E., Bonarek P., Górecki A., Kedracka-Krok S., Mikolajczak J., Polit A., et al. (2009). cAMP receptor protein from Escherichia coli as a model of signal transduction in proteins–a review. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 17, 1–11. doi: 10.1159/000178014, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto N., Inoue K., Hayashi Y., Yuasa H. (2006). Glycerol uptake in HCT-15 human colon cancer cell line by Na(+)-dependent carrier-mediated transport. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 29, 150–154. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.150, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao C., Hindra M., Mulde D., Yin C., Elliot M. A. (2012). Crp is a global regulator of antibiotic production in Streptomyces. MBio 3:e00407-12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00407-12, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng H., Jiang R. (2015). cAMP receptor protein (CRP)-mediated resistance/tolerance in bacteria: mechanism and utilization in biotechnology. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 99, 4533–4543. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6587-0, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glabonjat R. A., Kitsera M., Unterhauser K., Lembacher-Fadum C., Högenauer C., Raber G., et al. (2021). Simultaneous quantification of enterotoxins tilimycin and tilivalline in biological matrices using HPLC high resolution ESMS(2) based on isotopically (15)N-labeled internal standards. Talanta 222:121677. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2020.121677, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groisman E. A., Hollands K., Kriner M. A., Lee E.-J., Park S.-Y., Pontes M. H. (2013). Bacterial Mg2+ homeostasis, transport, and virulence. Annu. Rev. Genet. 47, 625–646. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-051313-051025, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunasekara S. M., Hicks M. N., Park J., Brooks C. L., Serate J., Saunders C. V., et al. (2015). Directed evolution of the Escherichia coli cAMP receptor protein at the cAMP pocket. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 26587–26596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.678474, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G., Lamont R. J. (2016). Dancing with the stars: how choreographed bacterial interactions dictate Nososymbiocity and give rise to keystone pathogens, accessory pathogens, and Pathobionts. Trends Microbiol. 24, 477–489. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.02.010, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han R., Xu L., Wang T., Liu B., Wang L. (2017). A small regulatory RNA contributes to the preferential colonization of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in the large intestine in response to a low DNA concentration. Front. Microbiol. 8:274. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00274, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haycocks J. R. J., Sharma P., Stringer A. M., Wade J. T., Grainger D. C. (2015). The molecular basis for control of ETEC enterotoxin expression in response to environment and host. PLoS Pathog. 11:e1004605. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004605, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hering F., Bücker G., Zechner H., Gorkiewicz G., Zechner E., Högenauer C., et al. (2019). Tilivalline- and Tilimycin-independent effects of Klebsiella oxytoca on tight junction-mediated intestinal barrier impairment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20:5595. doi: 10.3390/ijms20225595, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higaki M., Chida T., Takano H., Nakaya R. (1990). Cytotoxic component (s) of Klebsiella oxytoca on HEp-2 cells. Microbiol. Immunol. 34, 147–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1990.tb00999.x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirakawa H., Takita A., Kato M., Mizumoto H., Tomita H. (2020). Roles of CytR, an anti-activator of cyclic-AMP receptor protein (CRP) on flagellar expression and virulence in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 521, 555–561. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.10.165, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho S. N., Hunt H. D., Horton R. M., Pullen J. K., Pease L. R. (1989). Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene 77, 51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Högenauer C., Langner C., Beubler E., Lippe I. T., Schicho R., Gorkiewicz G., et al. (2006). Klebsiella oxytoca as a causative organism of antibiotic-associated hemorrhagic colitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 355, 2418–2426. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054765, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H., Shao X., Xie Y., Wang T., Zhang Y., Wang X., et al. (2019). An integrated genomic regulatory network of virulence-related transcriptional factors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nat. Commun. 10:2931. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10778-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn C. E., Charkowski A. O., Willis D. K. (2008). Evaluation of isolation methods and RNA integrity for bacterial RNA quantitation. J. Microbiol. Methods 75, 318–324. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2008.07.004, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong S.-H., Park J.-B., Wang Y., Kim G.-H., Zhang G., Wei G., et al. (2021). Regulatory molecule cAMP changes cell fitness of the engineered Escherichia coli for terpenoids production. Metab. Eng. 65, 178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2020.11.009, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C., Cheng Y., Cao H., Zhang B., Li J., Zhu L., et al. (2020). Effect of cAMP receptor protein gene on growth characteristics and stress resistance of Haemophilus parasuis Serovar 5. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 10:19. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L., Wang P., Song X., Zhang H., Ma S., Wang J., et al. (2021). Salmonella Typhimurium reprograms macrophage metabolism via T3SS effector SopE2 to promote intracellular replication and virulence. Nat. Commun. 12:879. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21186-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M., Zhang H. (2016). Engineering the shikimate pathway for biosynthesis of molecules with pharmaceutical activities in E. coli. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 42, 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2016.01.016, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joainig M. M., Gorkiewicz G., Leitner E., Weberhofer P., Zollner-Schwetz I., Lippe I., et al. (2010). Cytotoxic effects of Klebsiella oxytoca strains isolated from patients with antibiotic-associated hemorrhagic colitis or other diseases caused by infections and from healthy subjects. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48, 817–824. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01741-09, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. R., Lee S. E., Kim B., Choy H., Rhee J. H. (2013). A dual regulatory role of cyclic adenosine monophosphate receptor protein in various virulence traits of Vibrio vulnificus. Microbiol. Immunol. 57, 273–280. doi: 10.1111/1348-0421.12031, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King A. N., de Mets F., Brinsmade S. R. (2020). Who’s in control? Regulation of metabolism and pathogenesis in space and time. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 55, 88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2020.05.009, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamoto S., Nagao-Kitamoto H., Jiao Y., Gillilland M. G., III, Hayashi A., Imai J., et al. (2020). The Intermucosal connection between the mouth and gut in commensal Pathobiont-driven colitis. Cell 182, 447.e14–462.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klumpp S., Zhang Z., Hwa T. (2009). Growth rate-dependent global effects on gene expression in bacteria. Cell 139, 1366–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.001, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar J., Chauhan A. S., Gupta J. A., Rathore A. S. (2021). Supplementation of critical amino acids improves glycerol and lactose uptake and enhances recombinant protein production in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. J. 16:e2100143. doi: 10.1002/biot.202100143, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurabayashi K., Tanimoto K., Tomita H., Hirakawa H. (2017). Cooperative actions of CRP-cAMP and FNR increase the Fosfomycin susceptibility of Enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) by elevating the expression of glpT and uhpT under anaerobic conditions. Front. Microbiol. 8:426. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00426, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Z.-W., Hwang S.-H., Choi G., Jang K. K., Lee T. H., Chung K. M., et al. (2020). A MARTX toxin rtxA gene is controlled by host environmental signals through a CRP-coordinated regulatory network in Vibrio vulnificus. MBio 11:e00723-20. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00723-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leverton L. Q., Kaper J. B. (2005). Temporal expression of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli virulence genes in an in vitro model of infection. Infect. Immun. 73, 1034–1043. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.2.1034-1043.2005, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W., Djukovic A., Mathur D., Xavier J. B. (2021). Listening in on the conversation between the human gut microbiome and its host. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 63, 150–157. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2021.07.009, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D., Fan J., Wang J., Liu L., Xu L., Li F., et al. (2018). The fructose-specific phosphotransferase system of Klebsiella pneumoniae is regulated by global regulator CRP and linked to virulence and growth. Infect. Immun. 86:e00340-18. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00340-18, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindemose S., Nielsen P. E., Valentin-Hansen P., Møllegaard N. E. (2014). A novel indirect sequence readout component in the E. coli cyclic AMP receptor protein operator. ACS Chem. Biologicals 9, 752–760. doi: 10.1021/cb4008309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Han R., Wang J., Yang P., Wang F., Yang B. (2020c). Magnesium sensing regulates intestinal colonization of Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. MBio 11:e02470-20. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02470-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Li F., Xu L., Wang J., Li M., Yuan J., et al. (2020b). Cyclic AMP-CRP modulates the cell morphology of Klebsiella pneumoniae in high-glucose environment. Front. Microbiol. 10:2984. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Sun D., Zhu J., Liu J., Liu W. (2020a). The regulation of bacterial biofilm formation by cAMP-CRP: A mini-review. Front. Microbiol. 11:802. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2− ΔΔCT method. Methods 25, 402–408. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02470-20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minami J., Katayama S., Matsushita O., Sakamoto H., Okabe A. (1994). Enterotoxic activity of Klebsiella oxytoca cytotoxin in rabbit intestinal loops. Infect. Immun. 62, 172–177. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.1.172-177.1994, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minami J., Okabe A., Shiode J., Hayashi H. (1989). Production of a unique cytotoxin by Klebsiella oxytoca. Microb. Pathog. 7, 203–211. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(89)90056-9, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagao-Kitamoto H., Kamada N. (2017). Host-microbial cross-talk in inflammatory bowel disease. Immune Netw. 17, 1–12. doi: 10.4110/in.2017.17.1.1, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta K.-Y., Inoue K., Hayashi Y., Yuasa H. (2006). Carrier-mediated transport of glycerol in the perfused rat small intestine. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 29, 785–789. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.785, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou Q., Fan J., Duan D., Xu L., Wang J., Zhou D., et al. (2017). Involvement of cAMP receptor protein in biofilm formation, fimbria production, capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis and lethality in mouse of Klebsiella pneumoniae serotype K1 causing pyogenic liver abscess. J. Med. Microbiol. 66, 1–7. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000391, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal A., Iyer M. S., Srinivasan S., Seshasayee A. S., Venkatesh K. V. (2020). Global pleiotropic effects in adaptively evolved Escherichia coli lacking CRP reveal molecular mechanisms that define growth physiology. bioRxiv [Preprint]. doi: 10.1101/2020.06.18.159491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panjaitan N. S. D., Horng Y.-T., Cheng S.-W., Chung W.-T., Soo P.-C. (2019). EtcABC, a putative EII complex, regulates type 3 fimbriae via CRP-cAMP signaling in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1–15. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannuri A., Vakulskas C. A., Zere T., McGibbon L. C., Edwards A. N., Georgellis D., et al. (2016). Circuitry linking the catabolite repression and Csr global regulatory Systems of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 198, 3000–3015. doi: 10.1128/JB.00454-16, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paveglio S., Ledala N., Rezaul K., Lin Q., Zhou Y., Provatas A. A., et al. (2020). Cytotoxin-producing Klebsiella oxytoca in the preterm gut and its association with necrotizing enterocolitis. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 9, 1321–1329. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1773743, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platenkamp A., Mellies J. L. (2018). Environment controls LEE regulation in Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Front. Microbiol. 9:1694. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramamurthy T., Nandy R. K., Mukhopadhyay A. K., Dutta S., Mutreja A., Okamoto K., et al. (2020). Virulence regulation and innate host response in the pathogenicity of Vibrio cholerae. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 10:572096. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.572096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritzert J. T., Minasov G., Embry R., Schipma M. J., Satchell K. J. F. (2019). The cyclic AMP receptor protein regulates quorum sensing and global gene expression in Yersinia pestis during planktonic growth and growth in biofilms. MBio 10:e02613-19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02613-19, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salgado H. (2004). RegulonDB (version 4.0): transcriptional regulation, operon organization and growth conditions in Escherichia coli K-12. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 303D–306D. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh140, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen T. D., Livak K. J. (2008). Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C T method. Nat. Protoc. 3:1101. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneditz G., Rentner J., Roier S., Pletz J., Herzog K. A. T., Bucker R., et al. (2014). Enterotoxicity of a nonribosomal peptide causes antibiotic-associated colitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 13181–13186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403274111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soberón-Chávez G., Alcaraz L. D., Morales E., Ponce-Soto G. Y., Servín-González L. (2017). The transcriptional regulators of the CRP family regulate different essential bacterial functions and can be inherited vertically and horizontally. Front. Microbiol. 8:959. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soria-Bustos J., Ares M. A., Gómez-Aldapa C. A., González-Y-Merchand J. A., Girón J. A., De la Cruz M. A. (2020). Two type VI secretion systems of Enterobacter cloacae are required for bacterial competition, cell adherence, and intestinal colonization. Front. Microbiol. 11:560488. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.560488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse H., Gu Q., Sze K.-H., Chu I. K., Kao R. Y. T., Lee K.-C., et al. (2017). A tricyclic pyrrolobenzodiazepine produced by Klebsiella oxytoca is associated with cytotoxicity in antibiotic-associated hemorrhagic colitis. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 19503–19520. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.791558, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Untergasser A., Nijveen H., Rao X., Bisseling T., Geurts R., Leunissen J. A. M. (2007). Primer3Plus, an enhanced web interface to Primer3. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W71–W714. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm306, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unterhauser K., Pöltl L., Schneditz G., Kienesberger S., Glabonjat R. A., Kitsera M., et al. (2019). Klebsiella oxytoca enterotoxins tilimycin and tilivalline have distinct host DNA-damaging and microtubule-stabilizing activities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 3774–3783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1819154116, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uppal S., Jawali N. (2016). The cyclic AMP receptor protein (CRP) regulates mqsRA, coding for the bacterial toxin-antitoxin gene pair, in Escherichia coli. Res. Microbiol. 167, 58–62. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2015.09.001, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilches S., Jimenez N., Tomás J. M., Merino S. (2009). Aeromonas hydrophila AH-3 type III secretion system expression and regulatory network. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 6382–6392. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00222-09, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Tesmar A., Hoffmann M., Abou Fayad A., Hüttel S., Schmitt V., Herrmann J., et al. (2018). Biosynthesis of the Klebsiella oxytoca pathogenicity factor Tilivalline: heterologous expression, in vitro biosynthesis, and inhibitor development. ACS Chem. Biol. 13, 812–819. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.7b00990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Flint S., Palmer J. (2019). Magnesium and calcium ions: roles in bacterial cell attachment and biofilm structure maturation. Biofouling 35, 959–974. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2019.1674811, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei S., Bahl M. I., Baunwall S. M. D., Hvas C. L., Licht T. R. (2021). Determining gut microbial Dysbiosis: a review of applied indexes for assessment of intestinal microbiota imbalances. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 87:e00395-21. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00395-21, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wójcicki M., Świder O., Daniluk K. J., Średnicka P., Akimowicz M., Roszko M. Ł., et al. (2021). Transcriptional regulation of the multiple resistance mechanisms in Salmonella A review. PathoGenetics 10:801. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10070801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu K., Lin L., Shen D., Chou S.-H., Qian G. (2021). Clp is a “busy” transcription factor in the bacterial warrior, Lysobacter enzymogenes. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 19, 3564–3572. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2021.06.020, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue J., Tan B., Yang S., Luo M., Xia H., Zhang X., et al. (2016). Influence of cAMP receptor protein (CRP) on bacterial virulence and transcriptional regulation of allS by CRP in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Gene 593, 28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2016.08.006, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You C., Okano H., Hui S., Zhang Z., Kim M., Gunderson C. W., et al. (2013). Coordination of bacterial proteome with metabolism by cyclic AMP signalling. Nature 500, 301–306. doi: 10.1038/nature12446, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuasa H., Hamamoto K., Dogu S., Marutani T., Nakajima A., Kato T., et al. (2003). Saturable absorption of glycerol in the rat intestine. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 26, 1633–1636. doi: 10.1248/bpb.26.1633, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zollner-Schwetz I., Herzog K. A. T., Feierl G., Leitner E., Schneditz G., Sprenger H., et al. (2015). The toxin-producing Pathobiont Klebsiella oxytoca is not associated with flares of inflammatory bowel diseases. Dig. Dis. Sci. 60, 3393–3398. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3765-y, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Expression of reference gene (rrsH) under the different conditions tested in this study. Panels show the expression of reference gene in different: (A) growth conditions, (B) growth phases, (C) environmental cues, (D) K. oxytoca strains, and (E) growth culture medium with or without lactose. Quantification of expression is showed as rrsH (16S rRNA) copies per microgram of RNA.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.