Abstract

Objective:

Snacking among preschool aged children is nearly universal and has been associated with overconsumed nutrients, particularly solid fats and added sugars (SoFAS). This research examined caregivers’ schemas, or cognitive frameworks, for offering snacks to preschool-aged children.

Methods:

A qualitative design utilizing card sort methods was employed. Participants were 59 Black, Hispanic, and White caregivers of children aged 3 to 5 years with low-income backgrounds. Caregivers sorted 63 cards with images of commonly consumed foods/beverages by preschool-aged children in three separate card sorts to characterize snacking occasions, purposes, and contexts. The mean SoFAS content (kcal/100 g) of foods/beverages was evaluated by occasions (snacks vs. not-snacks), purposes, and contexts.

Results:

Just under two-thirds (38/63 food cards) of foods/beverages were classified as snacks with moderate to high agreement. Snacks were offered for non-nutritive (e.g., requests, rewards) and nutritive (e.g., hunger/thirst) purposes in routine (e.g., home, school) and social contexts (e.g., with grandparents). Snacks offered for non-nutritive purposes and in social contexts were higher in SoFAS than those offered for nutritive reasons and in routine contexts.

Conclusions:

Caregivers of young children offered various types of foods/beverages as snacks, with higher SoFAS snacks given for non-nutritive purposes and in social contexts. Understanding of caregivers’ schemas for offering snacks to young children may inform targets for obesity prevention and anticipatory guidance to promote the development of healthful eating behaviors.

1.0. Introduction

Snacking (i.e., eating between meals) among young children is nearly universal in the US and is also common in other parts of the world (Wang, van der Horst, Jacquier, Afeiche, & Eldridge, 2018). In 2017-2018, 95% of US children aged 2 to 5 years snacked daily, and more than two-thirds of children consumed between 2 to 4 snacks daily (U.S. Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service, 2020a). Secular increases in snacking among children over the past four decades have been most pronounced among racial/ethnic minority and low-income populations (Dunford & Popkin, 2018). Snacking contributes more energy to young children’s diets than any other single meal--currently 29% of daily energy (U.S. Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service, 2020b). The frequency, size, and energy density (kcal/g) of snacks consumed by US preschoolers also show links to overall diet quality (Kachurak, Bailey, Davey, Dabritz, & Fisher, 2019). In particular, roughly 40% of added sugars consumed by US preschoolers come from snacks (Shriver et al., 2018), suggesting that snacking is main point of entry for nutrient-poor foods in children’s diets (Slining & Popkin, 2013).

Caregivers have important influences on snacking behaviors among young children, given that the vast majority of snacking (~70%) (Gugger Dr., Bidwai, Joshi, Holschuh, & Albertson, 2015; Jacquier, Deming, & Eldridge, 2018) and daily energy intake (Poti & Popkin, 2011) occurs at home. While a growing cross-sectional evidence base has documented associations of food parenting practices with children’s intake of snack foods, few studies have assessed practices specific to the provision of snacks (Blaine, Kachurak, Davison, Klabunde, & Fisher, 2017). A number of qualitative studies suggest that caregivers approach feeding children snacks quite differently than meals. For example, in focus groups with mothers of preschool aged children with low-income backgrounds, family meals were viewed as opportunities to build strong relationships with children and teach lifelong lessons about structure and limit setting (Fisher et al., 2015; Herman, Malhotra, Wright, Fisher, & Whitaker, 2012; Malhotra et al., 2013). In contrast, snacks were viewed as challenging due to child nagging, and the types of snacks offered by other adults in the family, but were also viewed as appealing to the child and helpful to manage children’s behavior. Snacks have also been described as involving less balance, preparation, and planning than meals (Fisher et al., 2015; Loth et al., 2020). These findings collectively suggest that purposes for and contexts around child snacking may have implications for nutritional quality of foods offered to young children.

The present research aimed to advance understanding of caregiver schemas around child snacking by using card sorting methods to characterize snacking occasions, purposes, and contexts. Schemas characterize mental representations of concepts, like “child snacks,” that are organized in categories to guide behavior in familiar settings and shaped through experience (C. E. Blake, Bisogni, Sobal, Devine, & Jastran, 2007). They are grounded in experience, and therefore tend to be similar within groups that have common daily-life experiences. For instance, a schema about preparing breakfast for young children might include information about the expected sequence of events (e.g., parent cooks eggs, child sits at table) as well as the foods that the child likes to eat, are quick/easy to prepare, and will sustain the child until the next meal. Schemas have been investigated in numerous disciplines - from psychology to anthropology – to elucidate fundamental cognitive frameworks that underlie behavior (Barsalou, 1992; C. Blake & Bisogni, 2003; C. E. Blake et al., 2007; C. E. Blake, Bisogni, Sobal, Jastran, & Devine, 2008). To our knowledge, this is the first study to use card sorting methods to characterize caregivers’ cognitive schemas around child snacking occasions, purposes, and contexts to examine how the nutritional quality of snacks varies by those dimensions.

2.0. Methods

2.1. Design

A qualitative design involving card sorting methods was employed in which participants grouped food/beverages depicted on cards in response to open ended questions about child snacking. Card sorting is an established method for assessing “information architecture” or mental models of concepts (Borgatti, 1999; Weller & Romney, 1988). The card sort data were collected as part of a larger cross-sectional, mixed-methods study on food parenting practices around child snacking that included in-depth interviews. In brief, three sequential card sorts were interspersed with open-ended questions about parenting around snacking; findings from the in-depth interviews have been presented elsewhere (Blake et al., 2015; Younginer et al., 2016). The card sorts were used to comprehensively characterize snacking occasions (Sort 1), the reasons or purposes for offering children snacks (Sort 2), and situations or contexts in which snacks are given (Sort 3). The SoFAS content (kcal/100 g) of foods/beverages depicted in each card were estimated using national food composition databases to describe the nutritional quality of food/beverages offered by eating occasion (snacks vs. not snacks), purpose, and context.

2.2. Sampling and recruitment

A community sample of primary caregivers of children aged 3 to 5 years was recruited and sampled to include roughly equal numbers of caregivers of self-reported Black, Hispanic, and White race/ethnicity. Participants were recruited from using flyers posted in WIC offices and online community event listings in two large US cities (Philadelphia, Boston). To be eligible, participants had to be at least 18 years and be a primary caregiver and food-provider of a child aged 3 to 5 years who did not have a severe food allergy, chronic medical condition, or developmental disorder that influenced feeding. All study procedures were reviewed, approved, and conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Institutional Review Boards at Temple University (IRB 13736) and Harvard School of Public Health (IRB 130181). Participants were provided $45 in compensation for their participation.

2.3. Snack food card sorts

As illustrated in Figure 1, cards to be sorted depicted commonly consumed foods and beverages by preschool-aged children. The cards were developed for the study using data from three independent samples of caregivers who provided proxy reports of their preschool-aged child’s dietary intake using 24-dietary recall or open-ended survey methods. Data from 219 caregivers in upstate New York, 15 caregivers drawn at random from a larger sample of 250 families (40% African American) from North Carolina, and 50 Hispanic caregivers in Texas were used to identify 63 frequently reported foods/beverages of varying SoFAS content. Given the interest in SoFAS, 30 of 63 cards were developed to show a high SoFAS version of a food/beverage on one side of the card (e.g., whole and 2% milk) and a low SoFAS version on the other side (e.g., skim and 1% milk). Caregivers were asked to indicate which version (low vs. high SoFAS) of the snack food or beverage they most often provided to their child as a snack and we used this version of each card for the entirety of the interview.

Figure 1.

Snack Food Card Examples

The mean SoFAS content (kcal/100 g) of foods/beverages depicted on each card was estimated using approximately 10 representative entries (e.g., cracker entries include soda crackers, cheese crackers, and butter crackers) from the USDA Food Patterns Equivalents database (Bowman et al., 2013). When multiple types of a food were shown on a card (e.g., cupcake, chocolate cake, sheet cake), multiple types of each version of the food were selected from the food composition database and the SoFAS content (kcal/100 g) was averaged for all foods. Multiple types of preparation entries were also included when applicable (e.g., beans with no added fat, with added fat). For the 30 cards that depicted low and high SoFAS versions of foods/beverages, the mean SoFAS content was estimated separately for each side of the card; the estimate for the version chosen by the caregiver was used in subsequent analyses.

2.4. Procedures

Participants completed card sort activities as part of a 60 to 90 min in-depth interview completed in English or Spanish with trained research assistants (including one English-Spanish bilingual assistant). Three sequential card sorts were conducted to evaluate the scheme dimensions of snacking: occasions (Sort 1), purposes (Sort 2), and contexts for offering snacks (Sort 3). For the occasion sort (Sort 1), each caregiver was asked to “Take out the cards showing foods or drinks your child has as a snack”; those cards were classified as “snacks.” Caregivers were then asked to review those foods/beverages not considered to be a snack and to identify any that their child would eat outside of a meal; those cards were classified as “outside of meals.” The remaining cards were classified as “not snacks” and were excluded from subsequent card sorts. For the purpose sort (Sort 2), the caregiver was asked to describe reasons why the child gets snacks. The interviewer wrote each reason on a small piece of paper. The caregiver was then instructed to sort the cards by those reasons and asked to indicate if any additional reasons came to mind during the process. This procedure was repeated for the context sort (Sort 3), in which the caregiver was asked to describe the situations and places in which snacks were provided. Participants were asked to describe their thought processes out loud as they classified foods/beverages cards.

2.5. Data analyses

For the occasion sort, the consistency of classification of food/beverage cards as snacks vs. not snacks was calculated based on level of agreement (Lamantia, 2003; Righi et al., 2013). Standard cut-off values were used to classify participant agreement for classification of a food/beverage in a category as high (≥75%), moderate (50-74%), or low (<50%). For example, if 46 of the 59 (78%) participants classified apple sauce as a snack, that food was classified as a “snack” with high agreement.

For the purpose and context sorts, labels given by caregivers to describe each pile of cards were examined and relabeled with a generic description used across caregivers to create a common set of purpose and context categories for analysis. For example, labels “in the house” and “my house” were relabeled with the generic label of “home.” The frequency of each purpose and context given was calculated.

Mean SoFAS content (kcal/100 g) of card piles for each participant identified category were calculated at an individual level. Ad hoc comparisons of mean SoFAS values across major occasion, purpose, and context categories were made using independent, 2-tailed, t-tests with statistical significance indicated at p<.05.

3.0. Results

3.1. Demographics

The sample of 59 caregivers was racially/ethnically diverse (22 Black, 20 Hispanic, 17 White) and included mostly mothers (55/59) with a mean age of 31 ± 8 years. Most interviews were conducted in English (45/59). Education, employment, and marital status were varied, with more caregivers reporting education beyond high school (32/59), unemployment (28/59), and being single/divorced (37/59) than not. Close to 70% of caregivers had overweight (11/59) or obesity (30/59). Most participants reported participation in a US federal food assistance program, with 48/59 participating in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and 42/59 participating in the Women, Infants, and Children Program.

3.2. Occasions

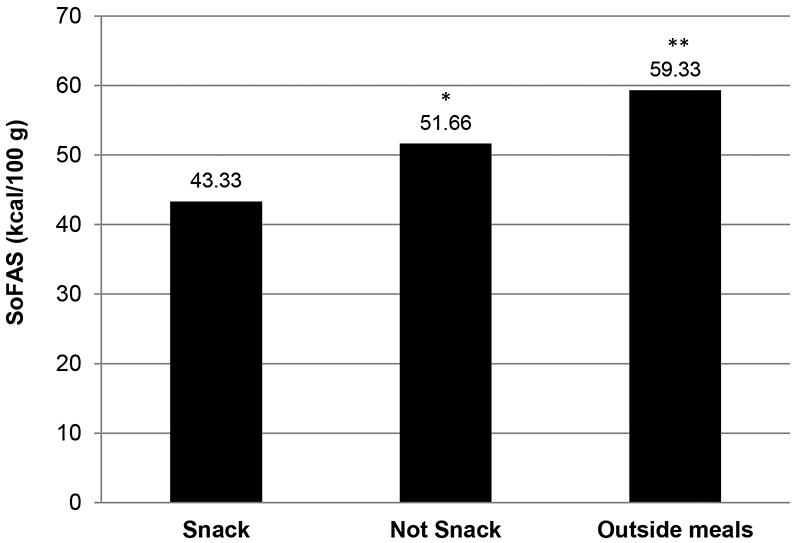

Caregivers' level of classification agreement was high to moderate (>75% and 50-74% respectively) for 42 of the 63 food/beverage cards classified in snack, in between meals, and not snack occasion categories (Table 1). Close to 60% (36/63 cards) of foods/beverages were classified as “snacks.” Of the 15 foods/beverages classified with high agreement as “snacks,” almost all were foods (as opposed to beverages). Of those foods, the largest number were fruits (n=6), followed by sweets/desserts (n=4), and then salty foods (n=2) and dairy (n=2). The six foods/beverages classified with high agreement as “not snacks” were varied and included legumes, grains, vegetables, mixed dishes, and a sugar sweetened beverage. Foods eaten in outside of meals but not considered snacks (i.e., “outside of meals”) were classified with low agreement among caregivers. As shown in Figure 2, the average SoFAS content of foods/beverages classified as “snacks” (Mean (SD) = 43.33 (10.30) kcal/100 g) was lower than those classified as foods consumed “not snacks” (Mean (SD) = 51.66 (16.33) or “outside of meals” (Mean (SD) = 59.33 (26.17) kcal/100 g; p<.01).

Table 1.

Classification of Foods and Beverages as Snack, Not Snack, or Outside of Meals

| Snacksa | Not Snacksb | Outside of Mealsc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Agreementd |

Moderate Agreemente |

High Agreementd |

Moderate Agreement e |

Low Agreementf |

| n=15 | n=21 | n=6 | n=11 | n=7 |

| Banana Apple Grapes Watermelon Oranges Yoghurt Cookies Fruit flavored pops Crackers Fruit snack Cheese Water Apple sauce Chips, Nachos, and Cheetos Fruit and granola bars |

Carrots Pudding Popcorn Canned fruit Milk Hard pretzel Mango Nuts Fruit drink Donut Soft pretzel Cake Chocolate candy Dried fruit Toast Cereals Sweet breads Flavored milk Jello Celery PBJ sandwich |

Tamale Spanish rice Peas Aquas Fresca/Horchata* Beans Soup |

Avocado Tortilla, tostada, taco shell Taco, Fajita, or Burrito Beef jerky Quesadilla Sausage Pasta or noodles Cherry tomatoes Soda Corn Waffles and pancakes |

Pizza Hamburger/Cheeseburger French fries, onion rings, tater tots Chicken nuggets Hot dog Hard candy Mac and cheese |

Note: Foods/beverages classified by caregivers of preschool-aged with low-income backgrounds as “snacks”, “not snacks”, and foods eaten “outside of meals” using card sorts involving 63 commonly consumed food/beverage items.

Snacks=Foods/beverages that caregivers classified as snacks for their child.

Not Snacks=Foods/beverages that caregivers classified as never being snacks for their child or never consumed at all.

Outside of meals= foods/beverages that caregivers classified as items consumed by their child between meals that were not considered snacks.

Items that >75% of caregivers agreed were classified in this category.

Items that >50% of caregivers agreed were classified in this category.

Items that 25-50% of caregivers agreed were classified in this category; these were the foods/beverages with the highest levels of agreement for inclusion in the outside of meals category.

Among Hispanic caregivers there was moderate level agreement (55%) to classify Aquas Frescas as “not snack”

Figure 2. Mean SoFAS Content (kcal/100 g) of Snack Foods/Beverages by Type of Eating Occasion.

Note. Mean SoFAS content of snack foods/beverages by eating occasion type; Two-tailed independent t-tests compared “snacks” vs. “not snacks” and “outside of meals” occasions, *p<.01, **p<.001.

3.3. Purposes for offering snacks

As shown in Table 2, caregivers described more non-nutritive reasons (n=6 categories) for offering snacks than reasons reflecting nutrition/health (n=4 categories). Giving snacks because the “child asks” was the top overall and non-nutritive reason cited by caregivers (32/59 caregivers). Specific labels given in this category included because “he/she wants it,” “he/she likes it,” “sees somebody eating and wants it,” and “child is bored, wants something to do.” The second most frequent overall and non-nutritive reason or purpose for giving children snacks was as a reward for good behavior (25/59). Specific labels given in this category include “the child is being good,” “eats all of his/her food at mealtime,” “eats all his/her vegetables,” and “when he/she doesn’t misbehave.” Other less frequently cited non-nutritive reasons cited by caregivers included giving snacks to distract/bribe the child, such as “keep him/her busy or calm” and “stop whining,” and giving snacks as part of a social activity, including playing or special occasion such as parties.

Table 2.

Count and Rank of Snack Purpose Categories

| Snack Purpose | Count (n) | Rank |

|---|---|---|

| Non-nutritive | ||

| Child asks-wants it-craves regardless of reason | 32 | 1 |

| Reward for good behavior | 25 | 2 |

| Distraction-bribe or to stop or prevent bad behavior | 15 | 4 |

| Part of playing-social activity | 13 | 6 |

| Part of a special event/ occasion/ celebration | 11 | 7 |

| Treat for no specific reason | 8 | 8 |

| Nutritive | ||

| Specific for current hunger or thirst | 23 | 3 |

| “Hold over” to prevent hunger or thirst | 23 | 3 |

| To promote health | 13 | 6 |

| Part of the daily routine | 14 | 5 |

Giving snacks for nutritive reasons because the child was thirsty/hungry (23/59) or as a “hold over” to prevent thirst and/or hunger (23/59) were the third most frequently described overall purpose categories. Specific labels given in these categories include “still hungry after a meal,” “hungry before lunch,” “hold him/her over to lunch/dinner,” and “does eat all his/her food at meals.” Other less frequently cited nutritive reasons for providing snacks included promoting health, such as “offer a healthy choice” and “to keep her energy up,” as well as part of a routine including specific times of day like “after school snack” and “after dinner snack.”

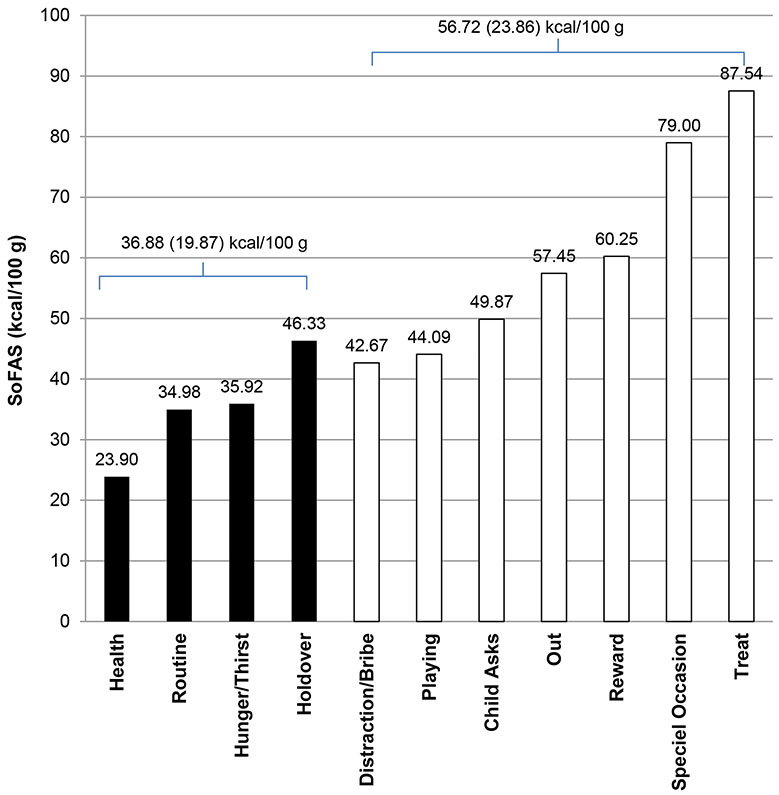

The average SoFAS content of foods/beverages varied across child snack purposes. As shown in Figure 2, snacks given for non-nutritive purposes (overall Mean (SD) = 56.72(23.86) kcal/100 g), such as treat (Mean (SD) = 87.54 (16.98) kcal/100 g) and special occasion (Mean (SD) =79.00 (12.79) kcal/100 g) tended to have higher SoFAS content than nutritive purposes (overall Mean (SD) = 36.88 (19.87) kcal/100 g) including health (Mean (SD) = 23.90 (20.28) kcal/100 g), routine (Mean (SD) = 34.98 (14.61) kcal/100 g), and thirst/hunger (Mean (SD) =35.92 (19.90) kcal/100 g), p<.001.

3.4. Sort 3: Contexts in which snacks are offered

As shown in Table 3, caregivers described routine contexts (n=5 categories) for giving snacks as well as explicit social contexts (n=4 categories). The top three snacking contexts were routine contexts of home (56/59), out/car (37/59), and school/daycare (31/59). Specific labels given in the home category included locations in the house (e.g., living room, in the kitchen), other activities occurring during the snack (e.g., “sofa watching TV”), timing relative to household routines (e.g., “snack between daycare and dinner”), and the presence of others during the snack (e.g., “with dad/mom”). Specific labels given in the “out/car” category described snacking in the context of errands (e.g., “out shopping”), appointments, and traveling (e.g., “out on the road” and “out and about”). Specific labels in the school/daycare category referred to school or childcare settings, babysitters, field trips, summer programs, after-school programs, camps, or special classes. A less frequently mentioned routine context was unstructured recreation, such as being outside and playing. The top social context was other family/friends (25/59), followed by grandparents (18/59) and structured recreation (16/59), such as parties, movies, and organized outings (e.g., a trip to the museum). Specific labels within this context category included “family/relatives” (e.g., “aunt’s house”) and “friends”.

Table 3.

Count and Rank of Snack Context/Location Categories

| Snack Context | Count (n) | Rank |

|---|---|---|

| Routine | ||

| Home | 56 | 1 |

| Out/car | 37 | 2 |

| School/daycare | 31 | 3 |

| Unstructured recreation (e.g., outside/park) | 16 | 6 |

| Doctor | 5 | 8 |

| Social | ||

| Other family/friends | 25 | 4 |

| Grandparent | 18 | 5 |

| Structured recreation (e.g., parties, sports) | 16 | 6 |

| Restaurant | 6 | 7 |

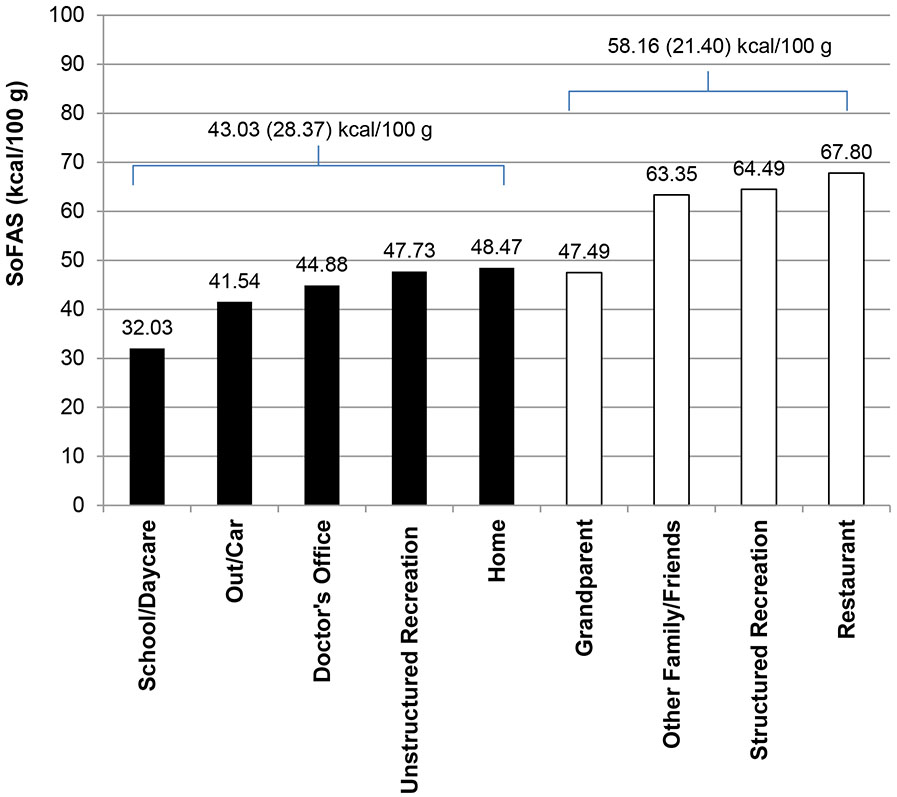

The average SoFAS content of foods/beverages varied across routine and social contexts in which snacks were given. As shown in Figure 3, social contexts (Mean (SD) = 58.16 (21.40) kcal/100 g) including “other/family friends” (Mean (SD) = 63.35 (22.04) kcal/100 g; p<.0001) and “structured recreation,” (e.g., parties, movies) (Mean (SD) = 64.06 (26.94) kcal/100 g, p<.001) involved higher SoFAS snacks that routine contexts (Mean (SD) = 43.03 (28.37) kcal/100 g) like school/childcare (Mean (SD) = 32.03 (23.76) kcal/100 g), p<0.001) and home (Mean (SD) =48.47 (18.71) kcal/100 g, p<.001), p<0.001.

Figure 3. Mean SoFAS Content (kcal/100 g) of Snack Foods/Beverages by Purposes for Offering Snacks.

Note. Mean SoFAS content (kcal/100 g) of snack foods/beverages by nutritive (black bars) vs. non-nutritive (white bars) purposes for offering snacks; Two-tailed independent t-test were used to compare compared nutritive vs. non-nutritive purposes, p<.001.

4.0. Discussion

Parents of young children generally describe snacking in terms of the types of foods offered, portion sizes, time of day, and location/context (C.E. Blake et al., 2015; Jacquier et al., 2018; Marx, Hoffmann, & Musher-Eizenman, 2016; Moore, Vadiveloo, McCurdy, Bouchard, & Tovar, 2021; Younginer et al., 2016). The findings of this study provide new evidence that the nutritional quality of snacks offered to young children varies with the purposes for offering snacks and contexts in which snacks are offered. To our knowledge, this is the first study to use card sorting to characterize caregivers’ “information architecture” or cognitive schemas around snacking occasions, purposes, and contexts. In this racially-ethnically diverse sample of families with low incomes, foods classified by caregivers as snacks tended to be sweet but had lower SoFAS content than those characterized as not snacks or outside of meals. Non-nutritive purposes for offering snacks were described more frequently than those purposes related to nutrition/health and were associated with higher SoFAS foods/beverages. Snacks offered in socially oriented contexts tended to have higher SoFAS than more routine location-based contexts. These findings advance understanding of excessive intakes from snacking among young children, suggesting that snacks used for non-nutritive purposes and in social contexts may be a focal source of SoFAS in young children’s diets.

Few studies to date have examined food-level schemas of snacks offered to preschoolers by caregivers. The findings of this study revealed a fair degree of agreement in the types of foods that caregivers view as snacks versus non-snacks. Snack food classifications highlighted sweetness as a common dimension (i.e., fruits, sweets/desserts) of snacks given to young children. These findings are consistent with the findings of an online survey in which parents of preschool aged children classified various foods and beverages as meals or snacks; a majority parents classified cookies/brownies (81%), chips/pretzels (77%), and candy (69%) as snacks (Marx et al., 2016). Similarly, the US 2008 Feeding Infants and Toddlers Study survey revealed that sweets were the most common snack offered to preschool children, both at and away from home (Jacquier et al., 2018). At the same time, in this study, foods classified by caregivers as “snacks” had lower mean SoFAS values than foods classified as “not-snacks” or “outside of meals.” It is important to note, however, that the results of this study do not reflect the frequency with which different types of foods/beverages are offered as snacks. Finally, the highest SoFAS content was seen for foods/beverages that were not considered to be “snacks” but were offered to children outside of meals. It is possible that foods/beverages in this category represent foods that are typically offered at meals and are also sometimes offered outside of regular mealtimes. Whether such foods are offered to children with a similar frequency to those categorized as “snacks” is unclear from the data presented. In any case, however, the findings suggest that some high SoFAS foods eaten outside of meals may not be fully captured in caregivers’ conceptualizations of “snacks.” These observations merit further inquiry and have implications for child dietary assessment as well as obesity prevention interventions targeting “snacking.”

The present findings provide new evidence that the SoFAS content of snacks offered to children may vary by purposes for offering snacks and the contexts in which snacks are given. Our findings are consistent with previous work indicating that snacks are provided to young children for a variety of non-nutritive as well as nutritive purposes. (Blaine et al., 2015; Fisher et al., 2015; Marx et al., 2016). For example, in this study, “child asks for it/wants it” was the most frequently purpose for offering children snacks. Similarly, an online survey of parents of preschool-children reported that “only when children ask for it” was the most frequent time-related cue for providing snacks among parents of preschool aged children (Marx et al., 2016). Parent reports of offering children 2-12 years snacks for non-nutritive reasons have also been associated with lower adherence to dietary recommendations relevant to obesity among children 2-12 years (Blaine et al., 2015). The present findings provide new descriptive evidence that offering snacks for non-nutritive purposes may shift the type of snack offered by caregivers to options with greater levels of solid fats and added sugar. A recent qualitative analysis of low-income mothers' definitions of snacks and purposes for offering snacks to infants revealed that the use of snacks for managing behavior may begin well before the preschool period (Moore et al., 2021). Collectively, the findings suggest that giving snacks to children for non-nutritive purposes is common and may represent a focal point of entry of high SoFAS foods into children’s diets. The non-nutritive purposes described appear to be situationally reactive, spontaneous, and oriented to managing children’s behavior. Not surprisingly, snacks given as treats and/or at special occasions were also associated with higher SoFAS values, highlighting the central cultural role of food in celebrations. The findings raise questions for future research regarding the extent to which offering palatable-energy dense snacks as rewards and/or in positive social contexts (Birch, Zimmerman, & Hind, 1980) may reinforce the hedonics of palatable foods that children tend to readily accept.

Previous qualitative analyses have revealed that caregivers define snacks offered to children based on contextual factors, including time of day and location, as well as the types and amounts of foods offered (Jacquier, Gatrell, & Bingley, 2017; Younginer et al., 2016). In the present study, home was the most frequent context in which snacks were offered to children. This finding is consistent with nationally representative US data showing that young children consume most snacking calories at home (Jacquier et al., 2018). In this study, however, caregivers identified a number of other snacking contexts/locations outside the home. In particular, the findings of this study provide new evidence snacks offered in routine contexts like childcare and school tend to be lower in SoFAS than those offered in explicitly social contexts. These findings suggest that social/recreational contexts outside the home may be focal settings for the consumption of overconsumed nutrients among young children.

The qualitative nature of the research and use of convenience sampling limit the generalizability of the findings. Whether the findings generalize to caregivers with higher-resource backgrounds is unclear. Similarly, the extent to which the findings have bearing for parenting around snacking among older children is unclear. Card sort methods are powerful qualitative tools for understanding caregivers’ schemas of snacks offered to preschoolers. However, while these data provide insight into the way that caregivers of young children think about snacking, they do not reflect actual behavior. Consequently, the extent to which cognitive schemas are aligned with actual provision of snack foods and other food parenting practices around child snacking is unclear. Finally, SoFAS content of foods were estimated using the most robust nutrient database available at the time of data collection. However, the SoFAS estimates represent a crude value for the general category shown on each card and may not accurately reflect the nutrient content of foods offered as snacks by caregivers in this study.

In conclusion, this qualitative research provides new descriptive evidence that caregivers of young children offer a variety of different types of snacks to children, with higher SOFAS snacks offered in social contexts and for non-nutritive purposes. These findings suggest that hedonics of highly palatable foods and beverages may be reinforced by being offered to children as snacks preferentially to manage/reward behavior and in socially rewarding contexts. The extent to which caregiver feeding practices around children’s snacking may influence the reinforcing value of palatable foods is not well characterized and an important question for future research. At least one randomized clinical trial to date has demonstrated that targeting parenting skills around snacks and sugary beverages is efficacious for reducing intake of SoFAS among preschool aged children with low-income backgrounds(Fisher et al., 2019). Research addressing the purposes and contexts for offering children foods and beverages in between meals may be a focal target for promoting healthy snacking behaviors and reducing children’s consumption of overconsumed nutrients.

Figure 4. Mean SoFAS Content (kcal/100 g) of Snack Foods/Beverages by Contexts for Offering Snacks.

Note. Mean SoFAS content (kcal/100 g) of snack foods/beverages by routine (black bars) vs. social (white bars) contexts for offering snacks; Two-tailed independent t-test compared routine vs. social contexts, p<.001.

Funding:

Funding for this research was provided by NIH R21HD074554. The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data.

Footnotes

Data and code availability: data are available upon request to the authors; the lead author has full access to the data reported in the manuscript.

Declarations of interest: none

Ethical Statement: All study procedures were reviewed, approved, and conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Institutional Review Boards at Temple University (IRB 13736) and Harvard School of Public Health (IRB 130181).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Barsalou LW (1992). Cognitive Psychology: An Overview for Cognitive Scientists. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates [Google Scholar]

- Birch LL, Zimmerman SI, & Hind H (1980). The influence of social-affective context on the formation of children's food preferences. Child Development, 51(3), 856–861. doi: 10.2307/1129474 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blaine RE, Fisher JO, Taveras EM, Geller AC, Rimm EB, Land T, … Davison KK (2015). Reasons low-income parents offer snacks to children: How feeding rationale influences snack frequency and adherence to dietary recommendations. Nutrients, 7(7), 5982–5999. doi: 10.3390/nu7075265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaine RE, Kachurak A, Davison KK, Klabunde R, & Fisher JO (2017). Food parenting and child snacking: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act, 14(1), 146. doi: 10.1186/s12966-017-0593-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake C, & Bisogni CA (2003). Personal and family food choice schemas of rural women in upstate New York. J Nutr Educ Behav, 35(6), 282–293. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60342-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake CE, Bisogni CA, Sobal J, Devine CM, & Jastran M (2007). Classifying foods in contexts: how adults categorize foods for different eating settings. Appetite, 49(2), 500–510. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake CE, Bisogni CA, Sobal J, Jastran M, & Devine CM (2008). How adults construct evening meals. Scripts for food choice. Appetite, 51(3), 654–662. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.05.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake CE, Fisher JO, Ganter C, Younginer N, Orloski A, Blaine RE, … Davison KK (2015). A qualitative study of parents' perceptions and use of portion size strategies for preschool children's snacks. Appetite, 88, 17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgatti SP (1999). Elicitation techniques for cultural domain analysis. In Schensul JJ & LeCompte MD (Eds.), The Ethnographer's Toolkit (Vol. 3). Walnut Creek, CA: Altimira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman SA, Clemens JC, Thoerig RC, Friday JE, Shimizu M, & AJ. M (2013). Food Patterns Equivalents Database 2009-10: Methodology and User Guide [Online]. Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food Surveys Research Group, Beltsville Human Nutrition Research Center, Beltsville, Maryland. Available at: http://www.ars.usda.gov/ba/bhnrc/fsrg. Retrieved from https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/80400530/pdf/fped/FPED_0910.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Dunford EK, & Popkin BM (2018). 37 year snacking trends for US children 1977-2014. Pediatr Obes, 13(4), 247–255. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JO, Serrano EL, Foster GD, Hart CN, Davey A, Bruton YP, … Polonsky HM (2019). Efficacy of a food parenting intervention for mothers with low income to reduce preschooler's solid fat and added sugar intakes: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act, 16(1), 6. doi: 10.1186/s12966-018-0764-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JO, Wright G, Herman AN, Malhotra K, Serrano EL, Foster GD, & Whitaker RC (2015). "Snacks are not food". Low-income, urban mothers' perceptions of feeding snacks to their preschool-aged children. Appetite, 84, 61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gugger C, Bidwai S, Joshi N, Holschuh N, & Albertson A (2015). Nutrient Contribution of Snacking in Americans: Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011-2012. The FASEB Journal, 29(S1), 587.514. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.29.1_supplement.587.14 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herman AN, Malhotra K, Wright G, Fisher JO, & Whitaker RC (2012). A qualitative study of the aspirations and challenges of low-income mothers in feeding their preschool-aged children. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act, 9, 132. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquier EF, Deming DM, & Eldridge AL (2018). Location influences snacking behavior of US infants, toddlers and preschool children. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 725. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5576-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquier EF, Gatrell A, & Bingley A (2017). "We don't snack": Attitudes and perceptions about eating in-between meals amongst caregivers of young children. Appetite, 108, 483–490. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachurak A, Bailey RL, Davey A, Dabritz L, & Fisher JO (2019). Daily snacking occasions, snack size, and snack energy density as predictors of diet quality among US children aged 2 to 5 years. Nutrients, 11(7). doi: 10.3390/nu11071440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamantia J (2003). Analyzing Card Sort Results with a Spreadsheet Template. Available from: . Retrieved from https://boxesandarrows.com/analyzing-card-sort-results-with-a-spreadsheet-template/ [Google Scholar]

- Loth KA, Tate AD, Trofholz A, Fisher JO, Miller L, Neumark-Sztainer D, & Berge JM (2020). Ecological momentary assessment of the snacking environments of children from racially/ethnically diverse households. Appetite, 145, 104497. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2019.104497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra K, Herman AN, Wright G, Bruton Y, Fisher JO, & Whitaker RC (2013). Perceived benefits and challenges for low-income mothers of having family meals with preschool-aged children: childhood memories matter. J Acad Nutr Diet, 113(11), 1484–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2013.07.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx JM, Hoffmann DA, & Musher-Eizenman DR (2016). Meals and snacks: Children's characterizations of food and eating cues. Appetite, 97, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore AM, Vadiveloo M, McCurdy K, Bouchard K, & Tovar A (2021). A recurrent cross-sectional qualitative study exploring how low-income mothers define snacks and reasons for offering snacks during infancy. Appetite, 105169. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2021.105169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poti JM, & Popkin BM (2011). Trends in energy intake among US children by eating location and food source, 1977-2006. J Am Diet Assoc, 111(8), 1156–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Righi C, James J, Beasley M, Day DL, Fox JE, Gieber J, … Lacoyna R (2013). Card Sort Analysis Best Practices. Journal of Usability Studies, 8(3), 69–89. [Google Scholar]

- Shriver LH, Marriage BJ, Bloch TD, Spees CK, Ramsay SA, Watowicz RP, & Taylor CA (2018). Contribution of snacks to dietary intakes of young children in the United States. Matern Child Nutr, 14(1). doi: 10.1111/mcn.12454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slining MM, & Popkin BM (2013). Trends in intakes and sources of solid fats and added sugars among U.S. children and adolescents: 1994-2010. Pediatr Obes, 8(4), 307–324. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2013.00156.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service. (2020a). Snacks: Distribution of Snack Occasions, by Gender and Age, What We Eat in America, NHANES 2017-2018. Retrieved from

- U.S. Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service. (2020b). Snacks: Percentages of Selected Nutrients Contributed by Food and Beverages Consumed at Snack Occasions, by Gender and Age, What We Eat in America, NHANES 2017-2018. Retrieved from

- Wang D, van der Horst K, Jacquier EF, Afeiche MC, & Eldridge AL (2018). Snacking Patterns in Children: A Comparison between Australia, China, Mexico, and the US. Nutrients, 10(2). doi: 10.3390/nu10020198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller SC, & Romney AK (1988). Systematic Data Collection. In. [Google Scholar]

- Younginer NA, Blake CE, Davison KK, Blaine RE, Ganter C, Orloski A, & Fisher JO (2016). "What do you think of when I say the word 'snack'?" Towards a cohesive definition among low-income caregivers of preschool-age children. Appetite, 98, 35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]