ABSTRACT

To uncover metal toxicity targets and defense mechanisms of the facultative anaerobe Pantoea sp. strain MT58 (MT58), we used a multiomic strategy combining two global techniques, random bar code transposon site sequencing (RB-TnSeq) and activity-based metabolomics. MT58 is a metal-tolerant Oak Ridge Reservation (ORR) environmental isolate that was enriched in the presence of metals at concentrations measured in contaminated groundwater at an ORR nuclear waste site. The effects of three chemically different metals found at elevated concentrations in the ORR contaminated environment were investigated: the cation Al3+, the oxyanion CrO42−, and the oxycation UO22+. Both global techniques were applied using all three metals under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions to elucidate metal interactions mediated through the activity of metabolites and key genes/proteins. These revealed that Al3+ binds intracellular arginine, CrO42− enters the cell through sulfate transporters and oxidizes intracellular reduced thiols, and membrane-bound lipopolysaccharides protect the cell from UO22+ toxicity. In addition, the Tol outer membrane system contributed to the protection of cellular integrity from the toxic effects of all three metals. Likewise, we found evidence of regulation of lipid content in membranes under metal stress. Individually, RB-TnSeq and metabolomics are powerful tools to explore the impact various stresses have on biological systems. Here, we show that together they can be used synergistically to identify the molecular actors and mechanisms of these pertubations to an organism, furthering our understanding of how living systems interact with their environment.

IMPORTANCE Studying microbial interactions with their environment can lead to a deeper understanding of biological molecular mechanisms. In this study, two global techniques, RB-TnSeq and activity metabolomics, were successfully used to probe the interactions between a metal-resistant microorganism, Pantoea sp. strain MT58, and metals contaminating a site where the organism can be located. A number of novel metal-microbe interactions were uncovered, including Al3+ toxicity targeting arginine synthesis, which could lead to a deeper understanding of the impact Al3+ contamination has on microbial communities as well as its impact on higher-level organisms, including plants for whom Al3+ contamination is an issue. Using multiomic approaches like the one described here is a way to further our understanding of microbial interactions and their impacts on the environment overall.

KEYWORDS: metabolomics, metal resistance, transposon mutagenesis

INTRODUCTION

The contamination plume emanating from the former S-3 pond waste site at the Oak Ridge Reservation (ORR) is a unique environment containing interesting metal-related microbial interactions. Waste from uranium enrichment and other processes containing elevated concentrations of nitrate and mixed metals was deposited into four unlined clay S-3 pond reservoirs for over 30 years before the liquid was neutralized and removed, with contaminated sludge depositing at the bottom of the reservoirs. The S-3 ponds were capped in 1988 and are now used as a parking lot (1). Despite the cleanup effort, groundwater from wells surrounding the S-3 ponds have decreased pH (as low as 3.0) and elevated concentrations of nitrate (up to 230 mM) as well as a variety of potentially toxic metals compared to background groundwater, such as aluminum (Al; up to 21 mM), uranium (U; up to 580 μM), and chromium (Cr; up to 8.3 μM) (2, 3). A survey of the geochemical properties and microbial communities (by small subunit [SSU] rRNA gene sequencing) of 93 wells in both noncontaminated and contaminated areas at ORR found that several geochemical properties, including pH and U and nitrate concentrations, could be predicted based on the constituent bacterial community, demonstrating a tight link between ORR microbes and their environment (3). Bacterial strains discovered in the ORR S-3 pond contamination plume likely have molecular mechanisms that protect them from metal toxicity.

Pantoea is a genus of facultative anaerobic bacteria in the class Gammaproteobacteria that contains a number of species studied for their interactions with metals. P. agglomerans SP1 is a mesophilic facultative anaerobe that can couple the oxidation of acetate to the reduction of metals, including Fe(III), Mn(IV), and Cr(VI), with electrons being supplied by H2 oxidation (4). Pantoea sp. strain TEM18 also has been shown to accumulate Cr(VI), Cd(II), and Cu(II) (5). Here, we focus on Pantoea sp. strain MT58 (MT58), which is closely related to P. ananatis by SSU rRNA gene sequence (>99% identical) and was previously isolated from a pristine ORR groundwater sample (6). MT58 was isolated anaerobically on glucose and nitrate in the presence of a contaminated ORR environment metal mixture, approximating metal concentrations found in highly contaminated groundwater samples taken near the S-3 ponds (6). Analysis of exact sequence variants from SSU rRNA gene sequencing of 93 different ORR noncontaminated and contaminated groundwater wells revealed that MT58 (or relatives with the same SSU rRNA gene sequence) was located in both the pristine area from which it was isolated and in highly contaminated groundwater wells adjacent to the S-3 ponds (6).

The goal of this study was to identify molecular interactions that allow MT58 to be resistant to and grow in the presence of the range of metals found in the contaminated ORR environment. We used two orthogonal omic approaches that give us different types of information that, when taken together, resulted in an enhanced representation of how MT58 is impacted by various metal challenge conditions. Random bar code transposon site sequencing (RB-TnSeq) is a powerful technique to annotate gene function using a transposon mutant library. With the use of random DNA barcodes, this method has higher throughput than standard transposon mutagenesis with next-generation sequencing (TnSeq), allowing us to probe multiple metal challenges efficiently (7). Compared with other genomics techniques like transcriptomics, gene fitness pinpoints which genes are necessary for survival under a given condition, not just those genes that are expressed. The other technique, activity-based metabolomics, allows for rapid comparison of the metabolomes of various microbial samples grown under different conditions and the identification of metabolites with a condition-specific functional role in the biological process. Defining metabolomes is a critical step in understanding and discovering drivers of biological processes, as any one protein may perform a number of reactions and the metabolites themselves act to perform numerous functions in cells (8).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A complete genome assembly of MT58 was generated using a combination of PacBio and Illumina data. The draft genome of MT58 contained 4,675,847 bp in four contigs with a 54.37% G+C content (GenBank accession no. GCA_014495885.1). A total of 4,370 coding sequences were predicted and three plasmids were discovered. An RB-TnSeq fitness library was constructed for MT58 with 447,153 uniquely bar-coded single transposon mutations using previously described approaches (7). Using this library, we were able to calculate gene fitness scores for 3,820 out of the 4,370 predicted protein-encoding genes in the MT58 genome.

Base and metal challenge fitness experiments were conducted for three metals individually (Al3+, CrO42−, and UO22+) under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions at their half-maximal inhibitory concentration (1 mM for Al3+, 5 μM for CrO42−, and 200 μM for UO22+). Strain fitness values were calculated as previously described (7) and are expressed as the normalized log2 ratio of counts for each strain between the base or challenge growth sample and the reference (time-zero) sample (see Data File S1 in the supplemental material). Gene fitness values were calculated as a weighted average of the strain fitness values for a given gene (7). Changes in gene fitness values were calculated for each challenge condition by subtracting the corresponding base condition gene fitness value from the challenge condition gene fitness value. Genes that had negative changes in gene fitness to the metal challenges of log2 ≤−1.5 (defined as large negative fitness changes) are listed in Tables 1 (aerobic) and 2 (anaerobic). Large positive gene fitness changes (log2 ≥1.5) from the metal challenges are listed in Tables S1 (aerobic) and S2 (anaerobic). A negative change in gene fitness value indicates that the metal challenge resulted in a decrease in the fitness of library mutants lacking that gene. To give a perspective on the number of genes with large metal-related gene fitness changes, those falling within defined ranges are shown in Table S3. Less than 2% of the 3,880 genes in the library had large gene fitness changes (log2 ≥|1.5|), while over 90% of the genes had a change of gene fitness between −0.5 and 0.5 under any given challenge condition.

TABLE 1.

Genes with large negative fitness changes (log2 ≤−1.5) with aerobic metal challenges

| Locus tag | Gene product function | ΔFitnessa |

|---|---|---|

| Al3+ challenge | ||

| Periplasm and outer membrane related | ||

| IAI47_13685 | Tol-Pal system protein, TolB | −5.0 |

| IAI47_09245 | Putative membrane protein, YmiA (family) | −2.2 |

| IAI47_12645 | Outer membrane porin, OmpA | −2.1 |

| IAI47_13700 | Tol-Pal system protein, TolQ | −1.9 |

| IAI47_08355 | Flagellar protein, FlhE | −1.6 |

| Arginine synthesis | ||

| IAI47_00915 | Argininosuccinate synthase, ArgG | −2.3 |

| IAI47_00910 | Acetylglutamate kinase, ArgB | −2.1 |

| IAI47_03975 | Amino-acid N-acetyltransferase, ArgA | −2.0 |

| IAI47_16830 | Ornithine carbamoyltransferase, ArgF | −1.9 |

| IAI47_00920 | Argininosuccinate lyase, ArgH | −1.7 |

| IAI47_00905 | N-Acetyl-gamma-glutamyl-phosphate reductase, ArgC | −1.7 |

| Other amino acid synthesis | ||

| IAI47_16015 | 3-Isopropylmalate dehydratase small subunit | −2.3 |

| IAI47_01040 | Threonine ammonia-lyase | −2.2 |

| IAI47_16210 | Homoserine kinase | −2.0 |

| IAI47_15115 | Glutamate-5-semialdehyde dehydrogenase | −1.7 |

| IAI47_01030 | Branched-chain amino acid transaminase | −1.6 |

| IAI47_01035 | Dihydroxy-acid dehydratase | −1.6 |

| IAI47_16350 | Phosphoserine phosphatase | −1.5 |

| DNA division and repair | ||

| IAI47_03820 | Site-specific tyrosine recombinase, XerD | −2.3 |

| Other and hypothetical | ||

| IAI47_08085 | Helix-turn-helix domain-containing protein | −1.6 |

| IAI47_09305 | Cyclic di-GMP phosphodiesterase | −1.6 |

| IAI47_03550 | Membrane-bound lytic murein transglycosylase, MltC | −1.5 |

| IAI47_08705 | Carboxy-terminal-processing peptidase | −1.5 |

| CrO42− challenge | ||

| Periplasm and outer membrane related | ||

| IAI47_05420 | PTS glucose transporter, IIA | −2.9 |

| IAI47_05070 | Outer membrane protein assembly, BamB | −2.8 |

| IAI47_11830 | Muramoyltetrapeptide carboxypeptidase | −2.0 |

| IAI47_06395 | NADH-quinone oxidoreductase, NuoI | −1.9 |

| IAI47_05465 | Bile acid:sodium symporter | −1.6 |

| IAI47_00655 | Glycosyltransferase, WaaG | −1.5 |

| Sulfate assimilation | ||

| IAI47_00785 | Periplasmic sulfate binding protein, Sbp | −4.1 |

| IAI47_05405 | Cysteine synthase, CysM | −3.7 |

| IAI47_04180 | Sulfate adenylyltransferase, CysD | −2.2 |

| IAI47_05440 | Cysteine synthase, CysK | −1.9 |

| IAI47_04185 | Sulfate adenylyltransferase, CysN | −1.7 |

| Iron transport | ||

| IAI47_15605 | Fe3+-hydroxamate ABC transporter, FhuC | −4.3 |

| IAI47_15595 | Fe3+-hydroxamate ABC transporter, FhuB | −3.2 |

| IAI47_15600 | Fe3+-hydroxamate ABC transporter, FhuD | −2.7 |

| DNA division and repair | ||

| IAI47_13290 | DNA-binding protein YbiB | −2.6 |

| IAI47_03820 | Site-specific tyrosine recombinase, XerD | −2.5 |

| IAI47_04300 | DNA recombinase, RecA | −2.2 |

| IAI47_18400 | Site-specific tyrosine recombinase, XerC | −2.1 |

| IAI47_08450 | Holliday junction branch migration DNA helicase, RuvB | −1.7 |

| Other and hypothetical | ||

| IAI47_18830 | tRNA synthesis GTPase, MnmE | −2.1 |

| IAI47_08705 | Carboxy-terminal-processing peptidase | −2.1 |

| IAI47_09350 | Oxidoreductase | −1.9 |

| IAI47_15970 | 16S rRNA [cytosine1402-N(4)]-methyltransferase RsmH | −1.8 |

| IAI47_07015 | ABC transporter ATP-binding protein | −1.8 |

| IAI47_06680 | LysR family transcriptional regulator | −1.7 |

| IAI47_21665 | DUF333 domain-containing protein | −1.7 |

| IAI47_00905 | N-Acetyl-gamma-glutamyl-phosphate reductase, ArgC | −1.6 |

| IAI47_04175 | Uroporphyrinogen-III C-methyltransferase | −1.6 |

| IAI47_06245 | tRNA pseudouridine(38-40) synthase, TruA | −1.5 |

| UO22+ challenge | ||

| Periplasm and outer membrane related | ||

| IAI47_13685 | Tol-Pal system protein, TolB | −3.3 |

The Δfitness is the difference between the average gene fitness value (of biological triplicate samples) under the metal challenge condition to the control condition with no metal addition for each gene.

TABLE 2.

Genes with large negative fitness changes (log2 ≤−1.5) with anaerobic metal challenges

| Locus tag | Gene product function | ΔFitnessa |

|---|---|---|

| Al3+ challenge | ||

| Periplasm and outer membrane related | ||

| IAI47_13685 | Tol-Pal system protein, TolB | −2.1 |

| DNA division and repair | ||

| IAI47_12790 | Chromosome partition protein, MukE | −2.4 |

| Other and hypothetical | ||

| IAI47_09580 | FNR family transcription factor | −1.5 |

| CrO42− challenge | ||

| Periplasm and outer membrane related | ||

| IAI47_13685 | Tol-Pal system protein, TolB | −2.7 |

| IAI47_13695 | Tol-Pal system protein, TolR | −1.5 |

| Sulfate assimilation | ||

| IAI47_04160 | Phosphoadenylyl-sulfate reductase | −2.0 |

| IAI47_00785 | Periplasmic sulfate binding protein, Sbp | −1.8 |

| IAI47_04180 | Sulfate adenylyltransferase, CysD | −1.8 |

| IAI47_04185 | Sulfate adenylyltransferase, CysN | −1.5 |

| Other and hypothetical | ||

| IAI47_18530 | Thioredoxin, TrxA | −2.1 |

| IAI47_13745 | 2-Oxoglutarate dehydrogenase E1 component | −1.7 |

| IAI47_03725 | Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase | −1.7 |

| UO22+ challenge | ||

| Periplasm and outer membrane related | ||

| IAI47_13685 | Tol-Pal system protein, TolB | −2.2 |

| IAI47_00675 | Glycosyltransferase | −2.1 |

| IAI47_12645 | Outer membrane porin, OmpA | −1.8 |

| IAI47_13700 | Tol-Pal system protein, TolQ | −1.6 |

| IAI47_00670 | Glycosyltransferase | −1.6 |

| IAI47_03645 | O-antigen ligase, WaaL | −1.5 |

| IAI47_00655 | Glycosyltransferase, WaaG | −1.5 |

| IAI47_03640 | Lipopolysaccharide 1,6-galactosyltransferase | −1.5 |

| Other and hypothetical | ||

| IAI47_07070 | HisA | −1.8 |

| IAI47_09040 | NAD-dependent epimerase | −1.7 |

The Δfitness is the difference between the average gene fitness value (of biological triplicate samples) under the metal challenge condition to the control condition with no metal addition for each gene.

A complementary set of global activity-based metabolomic experiments using wild-type MT58 were conducted matching the metal challenge fitness experiments. Extracted metabolite mass features were measured using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), and fold differences in concentrations of the mass features were determined between the six metal challenge samples and their corresponding base conditions using the XCMS Online platform (9). Compound identification was performed by comparing the experimental MS2 spectra with those recorded in the METLIN library (10). A summary of the number of dysregulated features with fold changes of ≥1.5 (P < 0.01) is shown in Table 3, while identified compounds with dysregulated features for each metal challenge aerobically and anaerobically are listed in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. The relative number of significantly dysregulated metabolites was small (<251 of the several thousand features detected) under any condition. Comparing the results of the fitness and related metabolomics experiments uncovered a number of potential interaction points between MT58 and the metal challenges, which are described in the following sections.

TABLE 3.

Number of dysregulated features with fold changes ≥ 1.5 (P < 0.01) for aerobic and anaerobic metal challengesa

| Test type | No. of dysregulated features |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al (A) | Cr (A) | U (A) | Al (An) | Cr (An) | U (An) | |

| RP | 17 | 11 | 0 | 30 | 1 | 5 |

| HILIC | 46 | 195 | 46 | 221 | 9 | 105 |

| Total | 63 | 206 | 46 | 251 | 10 | 110 |

| Annotated | 8 | 14 | 6 | 22 | 15 | 15 |

A, aerobic; An, anaerobic.

TABLE 4.

Annotated dysregulated features with changes of ≥1.5 (P < 0.01) for aerobic metal challenges

| Annotated feature | m/z | RTa (min) | Fold changeb | P value | Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al3+ challenge | |||||

| Arginine synthesis | |||||

| Ornithine | 133.0971 | 14.4 | 2.2 | 3E−03 | Down |

| Citrulline | 176.1027 | 11.0 | 1.6 | 3E−03 | Down |

| Amino acid synthesis | |||||

| Tyrosine | 182.0810 | 8.4 | 1.6 | 6E−03 | Up |

| Other | |||||

| Met Glu | 279.1008 | 9.8 | 2.1 | 2E−02 | Down |

| Xanthine | 153.0408 | 5.8 | 1.7 | 9E−03 | Up |

| cis-Δ2-11-methyl-dodecenoic acid | 227.2005 | 9.6 | 1.7 | 3E−02 | Down |

| Glutathione, oxidized | 613.1583 | 14.4 | 1.5 | 4E−02 | Down |

| Pantothenic acid | 220.1177 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 9E−03 | Down |

| CrO42− challenge | |||||

| Sulfate assimilation and oxidative stress | |||||

| Gamma-glutamylcysteine | 251.0696 | 9.3 | 2.8 | 3E−04 | Down |

| Cysteine | 122.0271 | 9.3 | 2.7 | 1E−04 | Down |

| Glutathione, oxidized | 613.1554 | 14.2 | 2.5 | 1E−03 | Down |

| Glutathione | 308.0912 | 10.0 | 2.5 | 4E−03 | Down |

| Fatty acid/membrane | |||||

| Ethyl oleate | 311.2575 | 7.9 | 2.5 | 1E−03 | Up |

| LysoPE(16:1(9Z)/0:0) | 452.2775 | 6.5 | 2.3 | 1E−03 | Up |

| PE(18:1(9Z)/0:0) | 480.3079 | 6.4 | 2.2 | 4E−05 | Up |

| PE(16:0/0:0) | 454.2922 | 8.7 | 2.0 | 5E−04 | Up |

| cis-7-hexadecenoic acid; 11Z-hexadecenoic acid | 255.2317 | 9.9 | 1.9 | 8E−04 | Up |

| Other | |||||

| dl-2-aminoadipic acid; N-methyl-l-glutamate | 162.0743 | 9.1 | 33.6 | 1E−04 | Down |

| Pantothenic acid | 220.1174 | 1.9 | 11.9 | 3E−04 | Down |

| N-Acetyl-l-lysine | 189.1231 | 9.3 | 4.2 | 4E−04 | Down |

| dl-Phenylalanine | 166.0855 | 1.7 | 3.1 | 1E−02 | Down |

| dl-o-tyrosine | 182.0809 | 8.2 | 2.6 | 2E−04 | Down |

| UO22+ challenge | |||||

| Lysine | 147.1128 | 14.8 | 4.6 | 3E−03 | Down |

| Glutathione, oxidized | 613.1586 | 14.4 | 2.7 | 1E−03 | Down |

| Ornithine | 133.0971 | 14.4 | 2.4 | 2E−03 | Down |

| 1-Octadecanamine | 270.3153 | 9.0 | 1.8 | 4E−02 | Down |

| Glutamate | 148.0604 | 9.7 | 1.7 | 3E−03 | Down |

| Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide | 664.1159 | 14.2 | 1.7 | 2E−02 | Down |

RT, retention time.

Pairwise jobs were performed in the XCMS platform to examine the fold change in metabolite features between bacteria cell samples grown under metal challenge and control conditions with no metal added in biological quintuplicate samples. A P value of <0.05 was set as the statistical significance threshold cutoff.

TABLE 5.

Annotated dysregulated features with changes of ≥1.5 (P < 0.01) for anaerobic metal challenges

| Annotated feature | m/z | RT (min) | Fold changea | P value | Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al3+ challenge | |||||

| Arginine synthesis | |||||

| Aspartic acid | 134.0448 | 9.9 | 25.0 | 2.00E−03 | Down |

| Ornithine | 133.0971 | 14.4 | 20.0 | 1.00E−04 | Down |

| Arginine | 175.1187 | 14.2 | 14.0 | 2.00E−03 | Down |

| Glutamate | 148.0604 | 9.8 | 5.2 | 3.00E−04 | Down |

| Citrulline | 176.1028 | 11.1 | 2.0 | 5.00E−03 | Down |

| Amino acid synthesis | |||||

| Histidine | 156.0766 | 14.1 | 15.0 | 8.00E−04 | Down |

| Threonine | 120.0656 | 9.8 | 2.9 | 8.00E−05 | Down |

| Phenylalanine | 166.0859 | 1.7 | 2.6 | 1.70E−02 | Down |

| Glutamine | 147.0764 | 10.4 | 2.4 | 5.00E−04 | Down |

| Fatty acid/membrane | |||||

| LysoPE(16:1(9Z)/0:0) | 452.2770 | 6.5 | 20.0 | 3.00E−02 | Down |

| PE(18:1(9Z)/0:0) | 480.3083 | 6.5 | 16.1 | 3.00E−03 | Down |

| PE(17:1(9Z)/0:0) | 466.2926 | 6.5 | 11.2 | 3.00E−03 | Down |

| PE(16:0/0:0) | 454.2920 | 8.5 | 7.2 | 3.00E−03 | Down |

| cis-7-hexadecenoic acid | 255.2313 | 9.9 | 3.0 | 6.00E−04 | Down |

| Oleic acid | 283.2629 | 10.6 | 2.6 | 2.00E−04 | Down |

| 1-palmitoyl-2-linoleoyl PE | 716.5216 | 5.3 | 2.0 | 3.00E−02 | Up |

| Other | |||||

| Betaine; 5-aminopentanoic acid | 118.0865 | 6.8 | 37.0 | 9.00E−03 | Down |

| Adenosine; vidarabine | 268.1040 | 7.0 | 11.0 | 4.00E−03 | Down |

| Glutathione, oxidized | 613.1588 | 14.4 | 9.0 | 9.80E−07 | Down |

| Deoxyadenosine | 252.1092 | 6.6 | 4.9 | 3.00E−03 | Down |

| Glutathione | 308.0909 | 10.2 | 3.3 | 3.00E−04 | Down |

| Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide | 664.1155 | 14.2 | 3.0 | 7.00E−04 | Down |

| CrO42− challenge | |||||

| Ophthalmic acid | 290.1347 | 10.1 | 3.2 | 4.00E−02 | Up |

| dl-Phenylalanine | 166.0855 | 1.7 | 3.1 | 1.00E−02 | Down |

| Betaine dimer | 235.1654 | 7.3 | 2.3 | 8.00E−03 | Down |

| Adenosine; vidarabine | 268.1041 | 7.0 | 2.2 | 1.00E−02 | Down |

| Riboflavin | 377.1458 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 3.00E−02 | Down |

| UO22+ challenge | |||||

| Fatty acid/membrane | |||||

| PE(16:0/0:0) | 454.2921 | 8.5 | 2.4 | 1.30E−02 | Down |

| PE(18:1(9Z)/0:0) | 480.3074 | 8.8 | 1.9 | 8.00E−03 | Down |

| 1-Palmitoyl-2-linoleoyl-PE | 716.5216 | 5.2 | 1.7 | 4.00E−02 | Down |

| Other | |||||

| Methylhistamine | 126.1025 | 5.1 | 59.0 | 5.00E−03 | Down |

| Lysine | 147.1128 | 15.0 | 23.0 | 3.00E−03 | Down |

| Ornithine | 133.0971 | 14.4 | 20.7 | 1.00E−04 | Down |

| S-Nitroso-l-glutathione | 337.0814 | 9.2 | 9.9 | 8.00E−03 | Up |

| Arginine | 175.1187 | 14.0 | 6.8 | 2.00E−03 | Down |

| Histidine | 156.0765 | 13.9 | 4.8 | 8.00E−04 | Down |

| Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide | 664.1158 | 14.1 | 3.6 | 1.00E−04 | Down |

| 2-Pyrrolidone−5-carboxylic acid | 130.0498 | 9.2 | 2.9 | 2.60E−02 | Up |

| Glutathione, oxidized | 613.1586 | 14.4 | 2.8 | 8.00E−03 | Down |

| Glutathione | 308.0911 | 10.0 | 2.2 | 2.00E−03 | Down |

| Niacin | 124.0393 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 3.00E−03 | Up |

| Serine | 106.0499 | 10.2 | 1.7 | 2.30E−02 | Down |

Pairwise jobs were performed in the XCMS platform to examine the fold change in metabolite features between bacteria cell samples grown under metal challenge and control conditions with no metal added in biological quintuplicate samples. A P value of <0.05 was set as the statistical significance threshold cutoff.

Al3+ impacts multiple amino acids, resulting in an arginine auxotrophy.

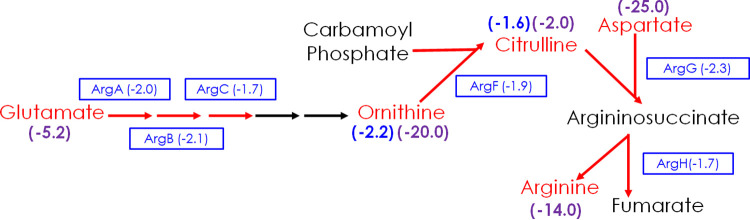

The aerobic and anaerobic Al3+ challenges of MT58 uncovered a link between Al3+ toxicity and arginine metabolism using both fitness and metabolomics data (Fig. 1). In the aerobic Al3+ fitness challenge, genes encoding six of the eight enzymes involved in converting glutamate to arginine had large negative gene fitness changes (ranging from −1.7 to −2.3), and two of the arginine synthetic pathway intermediate metabolites (ornithine [2.2-fold down] and citrulline [1.6-fold down]) were negatively dysregulated (Fig. 1). Arginine metabolism was also affected in the anaerobic Al3+ challenge with four intermediate metabolites (all amino acids), with arginine itself being negatively dysregulated (2.0- to 25.0-fold down) (Fig. 1). In contrast to the aerobic Al3+ challenge, while negative (ranging from −0.2 to −1.1), none of the arginine synthetic genes had large negative gene fitness changes in the anaerobic Al3+ challenge. Therefore, while Al3+ affects arginine metabolism under both oxygenation conditions, the observation is more pronounced using fitness data for the aerobic challenge and metabolomics data for the anaerobic challenge, illustrating how making use of both techniques was essential in making this observation.

FIG 1.

Aerobic and anaerobic Al3+ challenge results in negative fitness changes for multiple arginine synthesis genes and the decrease of key arginine synthetic pathway metabolites. Arginine synthesis pathway enzymes and metabolites that are impacted by Al3+ challenge are shown in red. Proteins encoded by genes with negative fitness changes are indicated in boxes with the change in parentheses, and metabolite fold changes are indicated in parentheses above or below the metabolite, with the negative sign indicating downward dysregulation. Aerobic Al3+ challenge effects are shown in blue, while anaerobic Al3+ challenge effects are shown in purple.

The metabolism of other amino acids was impacted by the aerobic and anaerobic Al3+ challenges as well. In the aerobic Al3+ challenge, a gene encoding one of the two enzymes involved in converting homoserine to threonine, and genes encoding three enzymes involved in branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) synthesis from threonine had large negative gene fitness changes, ranging from −1.6 to −2.3 (Table 1 and Fig. S1). In addition, genes encoding glutamate-5-semialdehyde dehydrogenase (−1.7) and phosphoserine phosphatase (−1.5), involved in proline and serine synthesis, respectively, had large negative gene fitness changes (Table 1). For the anaerobic Al3+ challenge, the metabolomics data showed that in addition to the amino acids involved in arginine synthesis discussed above (Fig. 1), several other amino acids were also negatively dysregulated severalfold, including threonine (2.9 down), histidine (15.0 down), phenylalanine (2.6 down), and glutamine (2.4 down) (Table 5).

It is interesting that we observed large fitness changes in amino acid synthesis genes while conducting the experiments in a minimal medium, as these strains are often auxotrophic for the amino acids in question. One explanation is that amino acid carryover from the LB recovery growth (despite washing) could have allowed limited growth of amino acid auxotrophic strains. This small amount of growth in turn could be negatively impacted by the Al3+ challenge. The fitness data support this hypothesis, with several amino acid synthesis genes having negative fitness values that decrease further upon Al3+ challenge (Fig. 2A, Table 1).

FIG 2.

Arginine corrects the growth defect caused by Al3+ in MT58. (A) Gene fitness value comparisons between aerobic base and aerobic Al3+ challenge conditions. Data points shown in red correspond to arginine synthetic genes with large changes in fitness values upon Al3+ challenge, while those in black correspond to other amino acid synthetic genes with large changes in fitness values upon Al3+ challenge. (B) Endpoint growth at 22 h of MT58 grown in the absence (black) and presence (gray) of 3 mM Al3+ with and without the addition of various amino acids (5 mM).

Under environmentally relevant conditions, Al3+ is not redox active. The Al3+ cation has a slow ligand exchange rate, and although it is largely insoluble at neutral pH, forming amorphous Al(OH)3 and mineralizing as Gibbsite [also Al(OH)3], it can remain in solution, interacting with numerous anions. Al3+ has a strong preference for negatively charged oxygen atoms, including those of SO42− and CO32−, and this also includes the carboxylic acid groups of amino acids (11). In human serum, Al3+ was shown to interact with several amino acids, with its affinity for lysine being the greatest, followed by affinity for ornithine, tyrosine, glutamate, and aspartate, respectively, although arginine was not reported (12).

To further test the impact of Al3+ on arginine metabolism, wild-type MT58 was grown aerobically in the presence and absence of 3 mM Al3+ at pH 6.5 in the presence and absence of several amino acids (5 mM) (Fig. 2B). Of the amino acids tested, only arginine supplementation was able to correct the growth defect caused by Al3+ (Fig. 2B). Taken together, the data support a model in which Al3+ binds to multiple amino acids intracellularly, resulting in their dysregulation, with the primary observable toxic effect being an arginine auxotrophy. Both the RB-TnSeq and metabolomics data indicate that Al3+ has a wider impact on amino acid metabolism in MT58 than just arginine synthesis, causing multiple large negative gene fitness changes in BCAA synthetic genes (Table 1) and the downward dysregulation of threonine among several other amino acids (Table 5). However, only the addition of arginine was able to correct growth in the presence of Al3+. The most likely explanation for the specificity of the arginine auxotrophy is that arginine synthesis involves four amino acids in addition to arginine that are dysregulated by Al3+, resulting predominantly in severe arginine limitation. We can also conclude that the Al3+ toxicity is mediated intracellularly as the fitness and metabolomics data were gathered using minimal medium growth conditions without arginine present. It follows that Al3+ binding arginine in the growth medium cannot be part of the toxicity mechanism. Additionally, if Al3+ toxicity could be prevented with extracellular binding, other amino acids would be expected to correct growth, particularly ornithine, which is chemically similar to arginine (with an amine rather than a guanidino side group at the end of the C3 aliphatic chain) and is known to bind Al3+ with high affinity (12).

Chromate enters MT58 through a sulfate transporter and oxidizes reduced intracellular sulfur species.

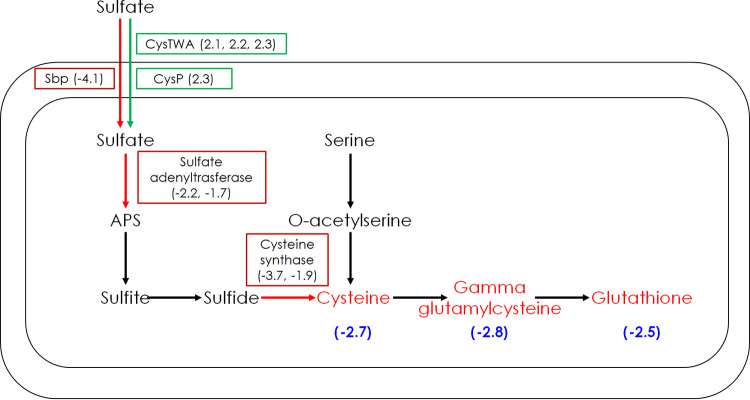

The hexavalent oxyanion chromate [CrO42−, Cr(VI)] is stable and highly soluble, but in contrast to Al3+, it is redox active under typical environmental conditions and can be reduced to the Cr(V), Cr(IV), and Cr(III) oxidation states. CrO42− is known to be toxic to biological systems and is both mutagenic and carcinogenic (13–18). CrO42− has chemical properties similar to those of sulfate (SO42−) and previously has been shown to enter bacterial cells through sulfate transporters (13, 19). When the MT58 library was exposed to CrO42− aerobically, the component genes of the ABC-type sulfate/thiosulfate transporter (cysT [2.1], cysW [2.2], and cysA [2.3]) all had large positive fitness changes, indicating that CrO42− enters the cell using this sulfate transporter, as inactivation would prevent a key step in the CrO42− toxicity mechanism (Fig. 3). The family of ABC-type transporters that CysTWA belongs to requires a periplasmic substrate binding protein (in the case of CysTWA a periplasmic sulfate binding protein) (20). In MT58, a gene encoding a periplasmic sulfate binding protein (cysP) is in the same operon as the cysTWA genes. Under the aerobic CrO42− challenge, cysP has a large positive gene fitness change (2.3) of magnitude similar to that of the cysTWA genes. Interestingly, MT58 encodes a second periplasmic sulfate binding protein (Sbp) whose gene has a large negative gene fitness change (−4.1) upon aerobic CrO42− challenge, opposite the fitness changes observed for the cysTWAP genes. It was previously shown in Escherichia coli that the two periplasmic sulfate binding proteins (CysP and Sbp) have overlapping functions (21). In E. coli, single cysP and sbp mutants can use sulfate and thiosulfate as sole sources of sulfur, but when both genes are inactivated, sulfate transport is blocked and a different sulfur source, like cysteine, is required for growth (21). The negative gene fitness change for sbp then would indicate that sulfate transport using Sbp (unlike CysP) as the periplasmic sulfate binding protein results in some level of protection from CrO42− toxicity.

FIG 3.

Aerobic CrO42− challenge impacts the sulfate assimilatory pathway. The genes encoding enzymes in red have negative fitness changes with the metal challenge, while those in green have positive fitness changes, with gene fitness change values in parentheses. Multiple fitness change values indicate the genes encoding multiple subunits of the protein. Metabolites in red are dysregulated in a downward fashion with the metal challenge, and the fold change is in parentheses below the metabolite, with the negative sign indicating downward dysregulation.

Once sulfate is transported into the cell, a series of biochemical steps take place (Fig. 3), resulting in the synthesis of reduced sulfur species. When exposed to CrO42− aerobically, a number of sulfate assimilation genes were found to have large negative changes in gene fitness (Table 1), including the genes of both subunits of sulfate adenylyltransferase (−2.2, −1.7) and of cysteine synthase (−3.7, −1.9). One previously proposed mechanism of CrO42− toxicity is that CrO42− oxidizes intracellular reduced sulfur species. Chromate is known to oxidize sulfide in vitro (22), and intracellular CrO42− reduction has been demonstrated in vivo using electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy in metabolically active rat thymocytes in which reduced forms of Cr [Cr(V) or Cr(III)] were detected upon CrO42− exposure (23). In addition, in our previous RB-TnSeq study characterizing the anaerobic effects of CrO42− toxicity on Pseudomonas stutzeri RCH2 (RCH2), fitness results combined with physiological growth studies were used to propose oxidation of reduced sulfur species as a mechanism of CrO42− toxicity (24). In that study, however, quantitation of the reduced thiol pool of RCH2 cells grown with and without CrO42− revealed similar reduced thiol concentrations. It was concluded that the cells maintained a consistent intracellular concentration of reduced thiols and that oxidation of the thiols by CrO42− only had the observable effect of decreasing growth (24). Hence, the metabolomics analysis reported here of the samples both exposed and not exposed to CrO42− allow us to further test the hypothesis that CrO42− oxidation of reduced sulfur compounds intracellularly is a mechanism of toxicity. Indeed, the concentrations of multiple reduced sulfur species were found to be decreased intracellularly upon MT58 exposure to CrO42−, including cysteine (2.7 down), gamma-glutamylecysteine (2.8 down), and glutathione (2.5 down) (Table 4).

One CrO42− toxicity mechanism previously observed is the generation of reactive oxygen species that damage DNA when CrO42− is reduced by species such as ascorbic acid and glutathione (25–27). For the aerobic CrO42− challenge, five DNA repair and/or division genes had large negative gene fitness changes (recA [−2.2] and ruvB [−1.7], involved in homologous recombination, xerD [−2.5] and xerC [−2.1], involved in chromosomal segregation during cell division, and ybiB [−2.6], a DNA binding protein induced in the DNA damage SOS response) (Table 1) (28–31). No DNA repair and/or division genes had large negative gene fitness changes in the anaerobic CrO42− challenge (Table 2), indicating that for MT58 this mechanism of CrO42− toxicity is elevated in or exclusive to aerobic growth. Does CrO42− target sulfate transport and assimilation under anaerobic conditions, as seen above in the aerobic CrO42− challenge? Although none of the reduced sulfur species that were negatively dysregulated under the aerobic CrO42− challenge were dysregulated anaerobically, several sulfate transport and assimilation genes had negative fitness changes with the anaerobic CrO42− challenge, although to a lesser degree, including Sbp (−1.8) and the two subunits of sulfate adenylyltransferase (−1.8, −1.5) (Table 2). The lower magnitude of the anaerobic CrO42− fitness response targeting sulfate assimilation compared to aerobic conditions may reflect a lower requirement for reduced sulfur species like glutathione, which is needed to repair oxidative stress damage, among other uses.

Lipopolysaccharide protects MT58 from anaerobic uranium challenge.

Like Cr, U can be redox active under physiological conditions and is present in environmental groundwaters in three different oxidation states [U(IV), U(V), and U(VI)], and these form different soluble and insoluble complexes depending on the pH, oxygen level, and geochemical composition of the environment (32). In oxic groundwater, U is present in the U(VI) oxidation state as the soluble uranyl oxycation (UO22+). In anoxic groundwater, U(V) and U(IV) predominate and U(V) usually forms soluble complexes, but U(IV) tends to precipitate as uraninite (UO2) (32). However, uraninite is easily oxidized to soluble UO22+ by O2, NO3−, and Fe(III) (33–35). In the present experiments, soluble UO22+ was added to both the aerobic and anaerobic U challenge cultures.

The anaerobic (but not aerobic) UO22+ challenge resulted in negative fitness changes for multiple genes involved in lipopolysaccharide (LPS) synthesis. LPS is a major component of the outer membrane in Gram-negative bacteria and is composed of three different sections, a lipid A hydrophobic membrane anchor, a core region made up of phosphorylated oligosaccharides, and an O-antigen composed of variable polysaccharides in repeating units. The genes encoding two enzymes involved in synthesis of the LPS core region (waaG [−1.5] and lipolysaccharide 1,6-galactosyltransferase [−1.5]) had large negative fitness changes in the anaerobic UO22+ challenge (Table 2). The LPS core region could be key to protecting microbes from UO22+ stress, as several studies have shown that the positively charged UO22+ ion binds to negatively charged phosphate residues in the LPS core region (36, 37). In E. coli, deletion of waaG resulted in a truncated LPS core section lacking most of the negatively charged phosphate groups where the UO22+ cation binds (38). A large negative fitness change was also observed for the gene encoding O-antigen ligase (waaL, −1.5). This protein ligates the O-antigen to the already constructed core region. Previously, a waaL deletion mutant in Pseudomonas aeruginosa was shown to result in cells with “rough” LPS that lacked the O-antigen (39). Additionally, two hypothetical genes next to each other in the MT58 genome, IAI47_00675 (−2.1) and IAI47_00670 (−1.6), had negative fitness changes upon anaerobic UO22+ challenge. Both genes are part of glycosyltransferase families that are involved in several steps of LPS synthesis (40), and the same is presumably true for LPS synthesis in MT58. LPS may also protect MT58 from aerobic CrO42− stress, as waaG (−1.5) has a large negative fitness change in this challenge experiment (Table 1). Although it has previously been reported that the UO22+ cation binds to LPS (36, 37), our fitness experiments show that this interaction is part of a defense mechanism that protects the organism from UO22+ toxicity. LPS molecules were not significantly dysregulated in the metabolomics analysis, and this is consistent with the proposed mechanism because the UO22+ cation binding to LPS would not necessarily alter the concentration of LPS as detected by mass spectrometry.

The Tol outer membrane integrity system protects MT58 from the challenge of multiple metals.

Our results show that the Tol proteins are important for MT58 fitness under multiple different metal challenges both aerobically and anaerobically (Tables 1 and 2). These proteins include an inner membrane complex composed of TolQ, TolR, and TolA along with the periplasmic protein TolB, which is known to interact with both TolA and the outer membrane lipoprotein anchor Pal (41). Large negative fitness changes were observed for TolB under five out of six (not the aerobic CrO42− challenge) metal challenge conditions, ranging from −2.1 (anaerobic Al3+ challenge) to −5.0 (aerobic Al3+ challenge) (Tables 1 and 2). In addition, TolR had large negative fitness changes in the anaerobic CrO42− (−1.5) challenge, while TolQ had large negative fitness changes in both the aerobic Al3+ (−1.9) and anaerobic UO22+ (−1.6) challenges. There are multiple theories for the exact physiological role of the Tol system, although it is likely that the Tol proteins are connected to several outer membrane processes. The Tol proteins are important for outer membrane integrity, since mutant strains lacking these proteins are osmosensitive (42). It has been suggested that the Tol proteins are used to bring the inner and outer membranes together in certain locations to help transport outer membrane components, such as the abundant outer membrane porin OmpA (41). The reverse of this process has been shown, whereby filamentous phage DNA and specific colicin antibiotic proteins are known to require components of the Tol system to enter the cell through outer membrane porins. For example, ColE9′ enters the cell through the porin OmpF, and the import process is dependent on TolB (43). OmpA is one of the most abundant outer membrane proteins and has been extensively studied, as it is a site for phage attachment. OmpA mutants are sensitive to several stresses, including sodium dodecyl sulfate, acid, and high osmolarity (44). Here, aerobic Al3+ (−2.1) and anaerobic UO22+ (−1.8) challenges resulted in large negative gene fitness changes for ompA. The fitness data here show that the outer membrane integrity Tol system as well as the abundant outer membrane porin OmpA are critical for defense against multiple types of metal stresses (cation, oxyanion, and oxycation) in addition to previously observed environmental stresses, including pH and osmolarity changes.

Membrane phosphatidylethanolamine metabolites are dysregulated in multiple metal challenges.

While fitness data were instrumental in determining the critical role of the outer membrane in metal stress, metabolomics data indicate that phospholipid molecules used to make both the inner and outer membranes are potential targets of general metal stress as well. A variety of metabolites associated with the bacterial cell membranes changed significantly under multiple metal challenge conditions (Table 6). Phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) is the principal phospholipid in bacterial membranes (45), and we found that several PEs or PE-associated metabolites, including PE(16:0/0:0), PE(17:1(9Z)/0:0), PE(18:1(9Z)/0:0), 1-palmitoyl-2-linoleoyl PE, and lysoPE(16:1(9Z)/0:0), were dysregulated significantly under anaerobic Al3+, anaerobic UO22+, and aerobic CrO42− challenges. Differences in the direction of dysregulation between aerobic and anaerobic conditions were observed: up-dysregulated in aerobic CrO42− challenge and down-dysregulated in anaerobic Al3+ and UO22+ challenge (1-palmitoyl-2-linoleoyl PE is the only exception in anaerobic Al3+ challenge). A monounsaturated fatty acid cis-7-hexadecenoic acid, known as a component of the cellular membranes of autotrophic bacteria (46), was significantly up dysregulated for aerobic CrO42− (1.9 up) challenge, while serine, used for the synthesis of sphingolipids and phospholipids in cellular membranes (47), was significantly down-dysregulated in anaerobic UO22+ (1.7 down) challenge. Lysine, which is critical to the stability of bacterial cell walls (48), was also significantly down-dysregulated in anaerobic UO22+ (23 down) challenge. Dysregulation of the various forms of PE may indicate direct damage done to the outer membrane by the various metals, or it could be due to the organism sensing the metal stress and changing the regulation of genes involved at different points in PE synthesis. This could account for the dysregulation in different directions of the aerobic and anaerobic metal stresses. Many genes involved in PE synthesis and differentiation are either essential or temperature sensitive, which may account for why we did not observe any large fitness effects for them in the metal challenges (49). The different sensitivities and limitations of the two global techniques demonstrates the need for both to provide information the other may miss that can lead to a deeper understanding of the molecular processes driving microbial interactions with their environment.

TABLE 6.

Cellular membrane related metabolites dysregulated under aerobic and anaerobic metal challengesa

| Metabolite | CrO42− (A) | Al3+ (An) | UO22+ (An) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LysoPE(16:1(9Z)/0:0) | 2.3 | −20 | |

| PE(16:0/0:0) | 2.0 | −7.2 | −2.4 |

| PE(17:1(9Z)/0:0) | −11 | ||

| PE(18:1(9Z)/0:0) | 2.2 | −16 | −1.9 |

| 1-palmitoyl-2-linoleoyl PE | 2.0 | −1.7 | |

| cis-7-hexadecenoic acid | 1.9 | ||

| Serine | −1.7 | ||

| Lysine | −23 |

A, aerobic; An, anaerobic.

Challenges in combining metabolomics and fitness data.

The challenge in combining metabolomics with genomics-based experiments such as fitness, transcriptomics, and metagenomics functional prediction comes from limitations of both technology types. Metabolomics aims to profile all of the metabolites present in biofluids, cells, and tissues (50). However, it is not yet possible to obtain all metabolite classes simultaneously, as many factors affect the metabolome coverage, such as sample pretreatment method, separation column, mobile-phase composition, and ionization mode. To capture the majority of the compounds in a complex mixture, several complementary analytical techniques are often needed in a metabolomics experiment. Here, we used both reverse-phase (RP) and hydrophilic interaction (HILIC) LC columns to facilitate the separation of both nonpolar and polar molecules; however, only positive ionization mode was used in the mass spectrometry analysis in both cases. Thus, those molecules that can only be measured in negative ionization mode or separated using gas chromatography would be missed. For example, LPS that was shown from the fitness data to be critical in the anaerobic UO22+ challenge is often measured via the detection of β-hydroxy fatty acids in negative ionization mode (51). Further, the instrument MS acquisition range of 40 to 1,000 m/z was used in the analysis, and those molecules with precursor ions outside this mass range, including LPS, cannot be detected. Molecules at concentration levels below the limits of detection for the quadrupole time-of-flight (QTOF) instrument used in this experiment also would be missing from the processed data. More importantly, only a subset of acquired metabolite features from any experiment can be confidently identified because of the limitations in metabolic feature analysis algorithms (52) and availability of reference molecule spectra in metabolite databases (53). However, through advancements in instrument technology, automated data processing, increased coverage in spectral databases, and better metabolite identification workflows, metabolomics is starting to overcome these challenges and have throughput to match genome-based omic technologies.

The challenges with fitness or genomics lie in the ability to have a genetic system in diverse microbes and in gene annotation (54, 55). In particular, limitations exist in the functional annotation of genes and the existence of uncharacterized metabolic pathways. We may see genes or gene products respond together with metabolites, but the connection between a particular metabolite and gene may not be described in the literature or databases (56, 57). This could be from unknown gene product activities or from unknown or uncharacterized pathways. This problem is increased when using nonmodel organisms, as we did in this study. Trying to overcome these issues was part of our rationale for this study in selecting fitness profiling, as it confirms a functional role in response to a specific condition, just as changes in the metabolome can be attributed to a direct response to the condition of interest. There are also limitations in being able to generate transposon libraries in many different types of organisms, although, like improvements to metabolite identification databases and automated workflows, there have been recent demonstrations of new methods that extend fitness profiling to many organisms (58, 59).

More generally, when we consider the alignment of metabolomics with fitness in systems biology analysis frameworks, we must take into account the differences in the techniques, both the biological dynamics they represent and the analytical limitations of the method or instrumentation. Metabolomics captures a time point snapshot of the state of overall metabolism in a cell. We also know that compared to transcription and translation, the metabolome responds fastest and most directly to changing environmental conditions (8). Gene fitness, on the other hand, is a measure of strain survival during growth that spans several doubling times before harvest (60). To maximize overlapping observations from the two different techniques, we measured the metabolites from the same time point that the RB-TnSeq was measured and examined the data from both the perspective of starting with top fitness hits and then looking for metabolites related to those pathways and, in parallel, identifying the top dysregulated features in the metabolomics data and then looking for related genes in the RB-TnSeq data with large fitness changes. The majority of significantly dysregulated metabolites identified in this study aligned well with the Rb-TnSeq results. However, we did identify a few significantly dysregulated metabolites that were not on known metabolic pathways identified by the RB-TnSeq technique. For example, the aerobic Al3+ challenge induced significant downregulation of cis-Δ2-11-methyl-dodecenoic acid (1.7 down), which is responsible for extracellular microbial communication, a response not noted from the fitness results. In other systems in studies we previously conducted combining transcriptomic and metabolomic profiling, we typically identified more metabolites that did not have a direct correlation with gene expression values (61). This appears to be an advantage of gene fitness over transcriptomic results, because expression does not always imply activity or function of the gene product, whereas fitness phenotypes do provide a direct connection from gene product to a functional role in phenotype presentation. By analyzing data from the metabolomics and genomics sides and following up on the generated hypotheses, we are currently able to use these different techniques on similar footage.

Summary.

Multiomic approaches are useful for uncovering complex biological interactions. For example, metabolomics and TnSeq were previously combined to probe the interaction of the plant pathogen Agrobacterium tumefaciens and its host to discover plant metabolites exploited as nutrients by A. tumefaciens central metabolism (62). Here, we used RB-TnSeq and activity-based metabolomics to probe the interaction of the metal-tolerant ORR strain MT58 to toxic metals found in the ORR S-3 pond contamination plume. In some cases, like LPS protecting the cell from UO22+ stress, only one of the techniques, in this case RB-TnSeq, provided evidence of the interaction. However, in most cases both RB-TnSeq and metabolomics provided complementary evidence for the metal interactions we observed with MT58. Fitness changes in six different genes and dysregulation of five metabolites uncovered that arginine is a primary target of Al3+ stress (Fig. 1). Fitness changes in nine different genes (some encoding multisubunit proteins) and 3 dysregulated metabolites also resulted in new observations on CrO42− toxicity impacting SO42- transport and assimilation, including that Sbp allows MT58 to differentiate CrO42− from SO42- (Fig. 3). Both techniques also led to insights into how critical the outer membrane is for resistance to metals in general, whether in the form of cations, oxyanions, or oxycations. All three tested metals, with these different chemistries, under either aerobic or anaerobic conditions, had large negative fitness changes for protein(s) in the Tol system involved in several outer membrane processes, while several PE-related metabolites were dysregulated in the metal challenge experiments. Therefore, the use of multiomic techniques provides a way to probe complex molecular interactions surrounding metal toxicity and resistance, key factors driving microbial survival in contaminated environments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genome sequencing.

The MT58 genome (GenBank accession no. GCA_014495885.1) was sequenced using both the Illumina and PacBio platforms. Illumina reads were cleaned and trimmed using BBtools (https://jgi.doe.gov/data-and-tools/bbtools) with default parameters. The resulting clean and trimmed Illumina reads were then assembled as a hybrid assembly with the raw PacBio reads using Unicycler with default parameters (63). This resulted in 4 circular contigs. These were then polished using the Illumina reads and Pilon until two successive passes produced no further changes (64). The 3 longest contigs were rotated to start with UniRef90_C9P927 (dnaA), UniRef90_A0A0E9C431 (repA), and UniRef90_A0A0F5F2F9 (repA). For the fourth, no suitable initiation replication match could be found.

Growth conditions.

Base medium containing 20 mM glucose, 4.7 mM NH4Cl, 1.3 mM KCl, 2 mM MgSO4, 0.2 mM NaCl, 1.2 mM NaHCO3, 5 mM NaH2PO4, and 0.1 mM CaCl2 with 1× vitamins and 1× trace elements was used to grow strains. The trace elements were prepared at 1,000× and contained 65.4 mM nitrilotriacetic acid, 25.3 mM MnCl2·4H2O, 7.4 mM FeCl3·6H2O, 7.7 mM CoCl2·6H2O, 9.5 mM ZnCl2, 0.4 mM CuCl2·2H2O, 0.4 mM AlK(SO4)2·12H2O, 1.6 mM H3BO3, 1.0 mM (NH4)2MoO4·4H2O, 1.9 mM NiCl2·6H2O, 0.8 mM Na2WO4·2H2O, and 1.1 Na2SeO3. The vitamin mix was prepared at 1,000× and contained 0.08 mM d-biotin, 0.05 mM folic acid, 0.49 mM pyridoxine HCl, 0.13 mM riboflavin, 0.19 mM thiamine, 0.41 nicotinic acid, 0.23 mM pantothenic acid, 0.74 μM vitamin B12, 0.36 mM p-amino benzoic acid, and 0.24 mM thiotic acid. Unless otherwise stated, 5 M HCl was used to adjust the medium pH to 7.0, and the medium was filter sterilized before use. For anaerobic growth, 20 mM KNO3 was added to the growth medium. Growth experiments were performed at 23°C with shaking (150 rpm). For growth curves, growth was monitored in a Bioscreen C (Thermo Labsystems, Milford, MA) by monitoring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600). For anaerobic growth, the Bioscreen C was placed in an anaerobic chamber (Plas Labs, Lansing, MI) with an atmospheric composition of 95% Ar and 5% H2. Growth curves were performed in biological triplicate with error bars representing the standard deviation. For metal challenge experiments, KAl(SO4)2·12H2O, K2Cr2O7, and C4H6O6U metal compounds were used.

Mutant library construction and growth.

The MT58 RB-TnSeq library was generated by conjugation using the E. coli donor strain WM3064 carrying the barcoded mariner transposon vector pHLL250 (strain AMD290) (65). Mid-log-phase MT58 was conjugated with mid-log-phase AMD290 at a 1:1 ratio for 6 h at 30°C on an LB agar plate supplemented with diaminopimelate. Mutant colonies were selected by plating on LB plates supplemented with 100 μg/ml kanamycin. Resistant colonies were pooled to make the final mutant library. To map transposon insertions and to associate these insertions with the random DNA barcodes, we used a TnSeq-like protocol (PMID 25968644). The MT58 RB-TNSeq mutant library contains 447,153 single mapped transposon mutations (7). Frozen (−80°C) library 10% glycerol stocks were recovered aerobically in LB with 50 μg/ml kanamycin to an OD600 of 1.0. Samples of the recovery culture were saved as the reference (time zero) samples. Base and challenge fitness growth experiments were carried out in triplicate in 5-ml cultures of base medium with and without the indicated challenge metals (1 mM for Al3+, 5 μM for CrO42−, and 200 μM for UO22+) inoculated to an OD600 of 0.02 from the recovery culture that had been washed once with basal medium and grown for 5 to 10 h to an OD600 of approximately 1.0 for aerobic growth and 0.5 for anaerobic growth. For anaerobic fitness growth, sealed Hungate tubes with an argon atmosphere were used. At the end of growth, the OD600 of each culture was recorded, and the cells were harvested by centrifugation (7,500 rpm for 10 min) as postgrowth samples. Both pregrowth and postgrowth samples were flash frozen and kept at −80°C until used for DNA extraction.

Metabolomics culture growth.

Cultures of wild-type MT58 for metabolomics experiments were grown in quintuplicate under identical conditions as described above for fitness growth. At the end of growth, a 1-ml sample was taken to determine the protein content of each culture using Bradford reagent (Millipore, St. Louis, MO), and the remaining cells were harvested by centrifugation (7,500 rpm for 10 min), flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and kept at 80°C until used for global metabolomics analysis.

DNA preparation, sequencing, and fitness analysis.

Frozen pellets from the fitness growth were processed for DNA isolation, sequencing, and sequence analysis as previously described using the BarSeq98 method (7). PCR products were sequenced with the Illumina HiSeq system. Fitness of each strain, defined as the binary logarithm of the ratio of postgrowth to pregrowth relative abundances, was calculated for individual transposon insertion strains before gene fitness values were calculated as previously described (7). Data quality control and normalization were performed as previously reported (7).

Global metabolomics.

Global metabolites were extracted from bacterial cell pellets using a mixture of acetonitrile-methanol-water (2:2:1; vol/vol) as previously described (66). Bacterial cellular metabolites were profiled using electrospray ionization quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (ESI-QTOF-MS) (Bruker impact II) in positive mode and separated under both RP and HILIC conditions using ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) columns, ACQUITY BEH C18 column (2.1 by 100 mm, 1.7 μm) and ACQUITY BEH amide column (2.1 by 100 mm, 1.7 μm; Waters Corp.), respectively. The mobile phases were comprised of water containing 0.1% formic acid (A) and acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid (B). In the RP analysis, the gradient started with 1% B (0 to 1 min), increased to 99% B in 9 min, and held for 3 min, followed by a 4-min reequilibration time. In the HILIC analysis, the gradient started with 1% A (0 to 1 min), increased to 35% A in 13 min, and then further increased to 60% A in 3 min, held for 1 min, and reequilibrated for 5 min. The flow rate was 150 μl/min, and the sample injection volume was 3 μl. ESI source parameters were set as the following: dry temperature, 200°C; dry gas, 8 liters/min; nebulizer, 29 lb/in2; capillary voltage, 4,000 V; and transfer in-source collision-induced dissociation energy, 0 eV. The instrument acquisition range was set at 40 to 1,000 m/z, and the MS acquisition rate was 2 spectra/s. A data-dependent auto-MS/MS workflow was performed to acquire the MS/MS spectra of metabolite features with the following settings: intensity threshold of 55; cycle time of 3 s; a smart exclusion after two spectra; and a precursor reconsideration if the intensity difference is >4. The MS/MS spectra were acquired at multiple collision energies (10, 20, and 50 eV) at an acquisition rate of 2 spectra/s over the m/z range of 25 to 1,000.

After manually checking the LC-MS data using the vendor software (Bruker Compass Data Analysis 4.3), the XCMS Online web platform was used for data processing (https://xcmsonline.scripps.edu). Pairwise jobs were performed to examine the differences of metabolite features between bacteria cell samples were grown under different conditions, with a P value of <0.05 set as the statistical significance threshold cutoff. Metabolite identification was done using accurate mass comparison and matching MS2 spectra through the METLIN metabolite repository. Additionally, many metabolite identities were validated through comparison with authentic reference standards.

Data availability.

The assembly was uploaded to NCBI and was annotated using the prokaryotic genome assembly pipeline (GCA_014495885.1).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The material by ENIGMA (Ecosystems and Networks Integrated with Genes and Molecular Assemblies) (http://enigma.lbl.gov), a Scientific Focus Area Program at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, is based upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, under contract number DE-AC02-05CH11231.

We thank Astrid Terry for project management.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Erica L. W. Majumder, Email: emajumder@wisc.edu.

Michael W. W. Adams, Email: adamsm@uga.edu.

Rebecca E. Parales, University of California, Davis

REFERENCES

- 1.Brooks SC. 2001. Waste characteristics of the former S-3 ponds and outline of uranium chemistry relevant to NABIR Field Research Center studies. Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, TN. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thorgersen MP, Lancaster WA, Vaccaro BJ, Poole FL, Rocha AM, Mehlhorn T, Pettenato A, Ray J, Waters RJ, Melnyk RA, Chakraborty R, Hazen TC, Deutschbauer AM, Arkin AP, Adams MW. 2015. Molybdenum availability is key to nitrate removal in contaminated groundwater environments. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:4976–4983. 10.1128/AEM.00917-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith MB, Rocha AM, Smillie CS, Olesen SW, Paradis C, Wu L, Campbell JH, Fortney JL, Mehlhorn TL, Lowe KA, Earles JE, Phillips J, Techtmann SM, Joyner DC, Elias DA, Bailey KL, Hurt RA, Preheim SP, Sanders MC, Yang J, Mueller MA, Brooks S, Watson DB, Zhang P, He Z, Dubinsky EA, Adams PD, Arkin AP, Fields MW, Zhou J, Alm EJ, Hazen TC. 2015. Natural bacterial communities serve as quantitative geochemical biosensors. mBio 6:e00326-15. 10.1128/mBio.00326-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Francis CA, Obraztsova AY, Tebo BM. 2000. Dissimilatory metal reduction by the facultative anaerobe Pantoea agglomerans SP1. Appl Environ Microbiol 66:543–548. 10.1128/AEM.66.2.543-548.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ozdemir G, Ceyhan N, Ozturk T, Akirmak F, Cosar T. 2004. Biosorption of chromium (VI), cadmium (II) and copper (II) by Pantoea sp. TEM18. Chem Eng J 102:249–253. 10.1016/j.cej.2004.01.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thorgersen MP, Ge X, Poole FL, Price MN, Arkin AP, Adams MW. 2019. Nitrate-utilizing microorganisms resistant to multiple metals from the heavily contaminated Oak Ridge Reservation. Appl Environ Microbiol 85:e00896-19. 10.1128/AEM.00896-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wetmore KM, Price MN, Waters RJ, Lamson JS, He J, Hoover CA, Blow MJ, Bristow J, Butland G, Arkin AP, Deutschbauer A. 2015. Rapid quantification of mutant fitness in diverse bacteria by sequencing randomly bar-coded transposons. mBio 6:e00306-15. 10.1128/mBio.00306-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rinschen MM, Ivanisevic J, Giera M, Siuzdak G. 2019. Identification of bioactive metabolites using activity metabolomics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 20:353–367. 10.1038/s41580-019-0108-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tautenhahn R, Patti GJ, Rinehart D, Siuzdak G. 2012. XCMS Online: a web-based platform to process untargeted metabolomic data. Anal Chem 84:5035–5039. 10.1021/ac300698c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guijas C, Montenegro-Burke JR, Domingo-Almenara X, Palermo A, Warth B, Hermann G, Koellensperger G, Huan T, Uritboonthai W, Aisporna AE, Wolan DW, Spilker ME, Benton HP, Siuzdak G. 2018. METLIN: a technology platform for identifying knowns and unknowns. Anal Chem 90:3156–3164. 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b04424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gensemer RW, Playle RC. 1999. The bioavailability and toxicity of aluminum in aquatic environments. Crit Rev Env Sci Tec 29:315–450. 10.1080/10643389991259245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bohrer D, Do Nascimento P, Mendonça J, Polli V, de Carvalho L. 2004. Interaction of aluminium ions with some amino acids present in human blood. Amino Acids 27:75–83. 10.1007/s00726-004-0069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cervantes C, Campos-García J, Devars S, Gutiérrez-Corona F, Loza-Tavera H, Torres-Guzmán JC, Moreno-Sánchez R. 2001. Interactions of chromium with microorganisms and plants. FEMS Microbiol Rev 25:335–347. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2001.tb00581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheung K, Gu J-D. 2007. Mechanism of hexavalent chromium detoxification by microorganisms and bioremediation application potential: a review. Int Biodeter Biodegr 59:8–15. 10.1016/j.ibiod.2006.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohtake H, Fujii E, Toda K. 1990. Reduction of toxic chromate in an industrial effluent by use of a chromate-reducing strain of Enterobacter cloacae. Environ Technol 11:663–668. 10.1080/09593339009384909. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Venitt S, Levy L. 1974. Mutagenicity of chromates in bacteria and its relevance to chromate carcinogenesis. Nature 250:493–495. 10.1038/250493a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishioka H. 1975. Mutagenic activities of metal compounds in bacteria. Mut Res Environ Mut 31:185–189. 10.1016/0165-1161(75)90088-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petrilli FL, De Flora S. 1977. Toxicity and mutagenicity of hexavalent chromium on Salmonella typhimurium. Appl Environ Microbiol 33:805–809. 10.1128/aem.33.4.805-809.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aguilar-Barajas E, Diaz-Perez C, Ramirez-Diaz MI, Riveros-Rosas H, Cervantes C. 2011. Bacterial transport of sulfate, molybdate, and related oxyanions. Biometals 24:687–707. 10.1007/s10534-011-9421-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adams M, Oxender DL. 1989. Bacterial periplasmic binding protein tertiary structures. J Biol Chem 264:15739–15742. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)71535-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sirko A, Zatyka M, Sadowy E, Hulanicka D. 1995. Sulfate and thiosulfate transport in Escherichia coli K-12: evidence for a functional overlapping of sulfate-and thiosulfate-binding proteins. J Bacteriol 177:4134–4136. 10.1128/jb.177.14.4134-4136.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim C, Zhou Q, Deng B, Thornton EC, Xu H. 2001. Chromium (VI) reduction by hydrogen sulfide in aqueous media: stoichiometry and kinetics. Environ Sci Technol 35:2219–2225. 10.1021/es0017007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arslan P, Beltrame M, Tomasi A. 1987. Intracellular chromium reduction. Biochim Biophys Acta 931:10–15. 10.1016/0167-4889(87)90044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thorgersen MP, Lancaster WA, Ge X, Zane GM, Wetmore KM, Vaccaro BJ, Poole FL, Younkin AD, Deutschbauer AM, Arkin AP, Wall JD, Adams MWW. 2017. Mechanisms of chromium and uranium toxicity in Pseudomonas stutzeri RCH2 grown under anaerobic nitrate-reducing conditions. Front Microbiol 8:1529. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kortenkamp A, O'Brien P. 1994. The generation of DNA single-strand breaks during the reduction of chromate by ascorbic acid and/or glutathione in vitro. Environ Health Persp 102:237–241. 10.2307/3431793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu P, Brodie EL, Suzuki Y, McAdams HH, Andersen GL. 2005. Whole-genome transcriptional analysis of heavy metal stresses in Caulobacter crescentus. J Bacteriol 187:8437–8449. 10.1128/JB.187.24.8437-8449.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Llagostera M, Garrido S, Guerrero R, Barbé J. 1986. Induction of SOS genes of Escherichia coli by chromium compounds. Environ Mutagen 8:571–577. 10.1002/em.2860080408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morimatsu K, Kowalczykowski SC. 2003. RecFOR proteins load RecA protein onto gapped DNA to accelerate DNA strand exchange: a universal step of recombinational repair. Mol Cell 11:1337–1347. 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00188-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adams DE, Tsaneva IR, West SC. 1994. Dissociation of RecA filaments from duplex DNA by the RuvA and RuvB DNA repair proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:9901–9905. 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blakely GW, Davidson AO, Sherratt DJ. 2000. Sequential strand exchange by XerC and XerD during site-specific recombination at dif. J Biol Chem 275:9930–9936. 10.1074/jbc.275.14.9930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schneider D, Kaiser W, Stutz C, Holinski A, Mayans O, Babinger P. 2015. YbiB from Escherichia coli, the defining member of the novel TrpD2 family of prokaryotic DNA-binding proteins. J Biol Chem 290:19527–19539. 10.1074/jbc.M114.620575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Markich SJ. 2002. Uranium speciation and bioavailability in aquatic systems: an overview. Sci World J 2:707–729. 10.1100/tsw.2002.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bencheikh-Latmani R, Williams SM, Haucke L, Criddle CS, Wu L, Zhou J, Tebo BM. 2005. Global transcriptional profiling of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 during Cr(VI) and U(VI) reduction. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:7453–7460. 10.1128/AEM.71.11.7453-7460.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holmes DE, Finneran KT, O'neil RA, Lovley DR. 2002. Enrichment of members of the family Geobacteraceae associated with stimulation of dissimilatory metal reduction in uranium-contaminated aquifer sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol 68:2300–2306. 10.1128/AEM.68.5.2300-2306.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu W-M, Carley J, Luo J, Ginder-Vogel MA, Cardenas E, Leigh MB, Hwang C, Kelly SD, Ruan C, Wu L, Van Nostrand J, Gentry T, Lowe K, Carroll S, Luo W, Fields MW, Gu B, Watson D, Kemner KM, Marsh T, Tiedje J, Zhou J, Fendorf S, Kitanidis PK, Jardine PM, Criddle CS. 2007. In situ bioreduction of uranium(VI) to submicromolar levels and reoxidation by dissolved oxygen. Environ Sci Technol 41:5716–5723. 10.1021/es062657b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Macaskie LE, Bonthrone KM, Yong P, Goddard DT. 2000. Enzymically mediated bioprecipitation of uranium by a Citrobacter sp.: a concerted role for exocellular lipopolysaccharide and associated phosphatase in biomineral formation. Microbiology (Reading) 146:1855–1867. 10.1099/00221287-146-8-1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barkleit A, Foerstendorf H, Li B, Rossberg A, Moll H, Bernhard G. 2011. Coordination of uranium(VI) with functional groups of bacterial lipopolysaccharide studied by EXAFS and FT-IR spectroscopy. Dalton Trans 40:9868–9876. 10.1039/c1dt10546a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yethon JA, Vinogradov E, Perry MB, Whitfield C. 2000. Mutation of the lipopolysaccharide core glycosyltransferase encoded by waaG destabilizes the outer membrane of Escherichia coli by interfering with core phosphorylation. J Bacteriol 182:5620–5623. 10.1128/JB.182.19.5620-5623.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abeyrathne PD, Daniels C, Poon KK, Matewish MJ, Lam JS. 2005. Functional characterization of WaaL, a ligase associated with linking O-antigen polysaccharide to the core of Pseudomonas aeruginosa lipopolysaccharide. J Bacteriol 187:3002–3012. 10.1128/JB.187.9.3002-3012.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schnaitman CA, Klena JD. 1993. Genetics of lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis in enteric bacteria. Microbiol Rev 57:655–682. 10.1128/mr.57.3.655-682.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clavel T, Germon P, Vianney A, Portalier R, Lazzaroni JC. 1998. TolB protein of Escherichia coli K‐12 interacts with the outer membrane peptidoglycan‐associated proteins Pal, Lpp and OmpA. Mol Microbiol 29:359–367. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kennedy EP. 1982. Osmotic regulation and the biosynthesis of membrane-derived oligosaccharides in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 79:1092–1095. 10.1073/pnas.79.4.1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Housden NG, Hopper JTS, Lukoyanova N, Rodriguez-Larrea D, Wojdyla JA, Klein A, Kaminska R, Bayley H, Saibil HR, Robinson CV, Kleanthous C. 2013. Intrinsically disordered protein threads through the bacterial outer-membrane porin OmpF. Science 340:1570–1574. 10.1126/science.1237864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang Y. 2002. The function of OmpA in Escherichia coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 292:396–401. 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DeChavigny A, Heacock PN, Dowhan W. 1991. Sequence and inactivation of the pss gene of Escherichia coli. Phosphatidylethanolamine may not be essential for cell viability. J Biol Chem 266:10710–15332. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)99281-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Knief C, Altendorf K, Lipski A. 2003. Linking autotrophic activity in environmental samples with specific bacterial taxa by detection of 13C‐labelled fatty acids. Environ Microbiol 5:1155–1167. 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ferreira CR, Goorden SMI, Soldatos A, Byers HM, Ghauharali-van der Vlugt JMM, Beers-Stet FS, Groden C, van Karnebeek CD, Gahl WA, Vaz FM, Jiang X, Vernon HJ. 2018. Deoxysphingolipid precursors indicate abnormal sphingolipid metabolism in individuals with primary and secondary disturbances of serine availability. Mol Genet Metab 124:204–209. 10.1016/j.ymgme.2018.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vollmer W, Blanot D, De Pedro MA. 2008. Peptidoglycan structure and architecture. FEMS Microbiol Rev 32:149–167. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dowhan W. 2013. A retrospective: use of Escherichia coli as a vehicle to study phospholipid synthesis and function. Biochim Biophys Acta 1831:471–494. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Johnson CH, Ivanisevic J, Siuzdak G. 2016. Metabolomics: beyond biomarkers and towards mechanisms. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 17:451–459. 10.1038/nrm.2016.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pais de Barros J-P, Gautier T, Sali W, Adrie C, Choubley H, Charron E, Lalande C, Le Guern N, Deckert V, Monchi M, Quenot J-P, Lagrost L. 2015. Quantitative lipopolysaccharide analysis using HPLC/MS/MS and its combination with the limulus amebocyte lysate assay. J Lipid Res 56:1363–1369. 10.1194/jlr.D059725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu Y, Cai B, Huan T. 2019. Enhancing metabolome coverage in data-dependent LC–MS/MS analysis through an integrated feature extraction strategy. Anal Chem 91:14433–14441. 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b02980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xue J, Guijas C, Benton HP, Warth B, Siuzdak G. 2020. METLIN MS 2 molecular standards database: a broad chemical and biological resource. Nat Methods 17:953–954. 10.1038/s41592-020-0942-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Otwell AE, López García de Lomana A, Gibbons SM, Orellana MV, Baliga NS. 2018. Systems biology approaches towards predictive microbial ecology. Environ Microbiol 20:4197–4209. 10.1111/1462-2920.14378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lui LM, Majumder EL-W, Smith HJ, Carlson HK, von Netzer F, Fields MW, Stahl DA, Zhou J, Hazen TC, Baliga NS. 2021. Mechanism across scales: a holistic modeling framework integrating laboratory and field studies for microbial ecology. Front Microbiol 12:642422. 10.3389/fmicb.2021.642422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huan T, Forsberg EM, Rinehart D, Johnson CH, Ivanisevic J, Benton HP, Fang M, Aisporna A, Hilmers B, Poole FL, Thorgersen MP, Adams MWW, Krantz G, Fields MW, Robbins PD, Niedernhofer LJ, Ideker T, Majumder EL, Wall JD, Rattray NJW, Goodacre R, Lairson LL, Siuzdak G. 2017. Systems biology guided by XCMS Online metabolomics. Nat Methods 14:461–462. 10.1038/nmeth.4260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Majumder EL-W, Billings EM, Benton HP, Martin RL, Palermo A, Guijas C, Rinschen MM, Domingo-Almenara X, Montenegro-Burke JR, Tagtow BA, Plumb RS, Siuzdak G. 2021. Cognitive analysis of metabolomics data for systems biology. Nat Protoc 16:1376–1418. 10.1038/s41596-020-00455-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu H, Price MN, Waters RJ, Ray J, Carlson HK, Lamson JS, Chakraborty R, Arkin AP, Deutschbauer AM. 2018. Magic pools: parallel assessment of transposon delivery vectors in bacteria. mSystems 3:e00143-17. 10.1128/mSystems.00143-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Price MN, Wetmore KM, Waters RJ, Callaghan M, Ray J, Liu H, Kuehl JV, Melnyk RA, Lamson JS, Suh Y, Carlson HK, Esquivel Z, Sadeeshkumar H, Chakraborty R, Zane GM, Rubin BE, Wall JD, Visel A, Bristow J, Blow MJ, Arkin AP, Deutschbauer AM. 2018. Mutant phenotypes for thousands of bacterial genes of unknown function. Nature 557:503–509. 10.1038/s41586-018-0124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thompson MG, Blake-Hedges JM, Cruz-Morales P, Barajas JF, Curran SC, Eiben CB, Harris NC, Benites VT, Gin JW, Sharpless WA, Twigg FF, Skyrud W, Krishna RN, Pereira JH, Baidoo EEK, Petzold CJ, Adams PD, Arkin AP, Deutschbauer AM, Keasling JD. 2019. Massively parallel fitness profiling reveals multiple novel enzymes in Pseudomonas putida lysine metabolism. mBio 10:e02577-18. 10.1128/mBio.02577-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Otwell AE, Carr AV, Majumder ELW, Ruiz MK, Wilpiszeski RL, Hoang LT, Webb B, Turkarslan S, Gibbons SM, Elias DA, Stahl DA, Siuzdak G, Baliga NS. 2021. Sulfur metabolites play key system-level roles in modulating denitrification. mSystems 6:e01025-20. 10.1128/mSystems.01025-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gonzalez‐Mula A, Lachat J, Mathias L, Naquin D, Lamouche F, Mergaert P, Faure D. 2019. The biotroph Agrobacterium tumefaciens thrives in tumors by exploiting a wide spectrum of plant host metabolites. New Phytol 222:455–467. 10.1111/nph.15598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wick RR, Judd LM, Gorrie CL, Holt KE. 2017. Unicycler: resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput Biol 13:e1005595. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]