ABSTRACT

Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis (referred to here as L. lactis) is a model lactic acid bacterium and one of the main constituents of the mesophilic cheese starter used for producing soft or semihard cheeses. Most dairy L. lactis strains grow optimally at around 30°C and are not particularly well adapted to the elevated temperatures (37 to 39°C) to which they are often exposed during cheese production. To overcome this challenge, we used adaptive laboratory evolution (ALE) in milk, using a setup where the temperature was gradually increased over time, and isolated two evolved strains (RD01 and RD07) better able to tolerate high growth temperatures. One of these, strain RD07, was isolated after 1.5 years of evolution (400 generations) and efficiently acidified milk at 41°C, which has not been reported for industrial L. lactis strains until now. Moreover, RD07 appeared to autolyze 2 to 3 times faster than its parent strain, which is another highly desired property of dairy lactococci and rarely observed in the L. lactis subspecies used in this study. Model cheese trials indicated that RD07 could potentially accelerate cheese ripening. Transcriptomics analysis revealed the potential underlying causes responsible for the enhanced growth at high temperatures for the mutants. These included downregulation of the pleiotropic transcription factor CodY and overexpression of genes, which most likely lowered the guanidine nucleotide pool. Cheese trials at ARLA Foods using RD01 blended with the commercial Flora Danica starter culture, including a 39.5°C cooking step, revealed better acidification and flavor formation than the pure starter culture.

IMPORTANCE In commercial mesophilic starter cultures, L. lactis is generally more thermotolerant than Lactococcus cremoris, whereas L. cremoris is more prone to autolysis, which is the key to flavor and aroma formation. In this study, we found that adaptation to higher thermotolerance can improve autolysis. Using whole-genome sequencing and RNA sequencing, we attempt to determine the underlying reason for the observed behavior. In terms of dairy applications, there are obvious advantages associated with using L. lactis strains with high thermotolerance, as these are less affected by curd cooking, which generally hampers the performance of the mesophilic starter. Cheese ripening, the costliest part of cheese manufacturing, can be reduced using autolytic strains. Thus, the solution presented here could simplify starter cultures, make the cheese manufacturing process more efficient, and enable novel types of harder cheese variants.

KEYWORDS: Lactococcus, adaptive mutations, autolysis, dairy, food microbiology, heat shock, stress adaptation

INTRODUCTION

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are widely applied in food fermentations, and they are particularly well known for their essential roles in the dairy industry (1). To stress the latter, in 2019, approximately 852 million tons of milk were produced globally, of which approximately 30% was fermented using LAB, resulting in products like cheese, yogurt, and fermented butter (2, 3). Ever since the first cheeses were produced more than 9,000 years ago, the urge to produce new products has driven the diversification and optimization of production processes and the responsible LAB (1, 4, 5). More than 75% of all cheeses are produced using the same steps (6). First, raw milk is pasteurized to inactivate pathogens and spoilage microorganisms and then standardized according to fat and protein content (7, 8). Subsequently, the milk is coagulated by proteolytic enzymes, for example, rennet, and fermented by LAB (6). The moisture content (firmness) and flavor of the cheese are controlled by heating the curd, which is called cooking or scalding (9). The temperature and duration of the cooking step determine which LAB can be used in the production. For cooking temperatures below 40°C, mesophilic LAB, such as Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis (referred to here as L. lactis), are used, whereas for higher temperatures, thermophilic LAB, such as Streptococcus thermophilus, are applied (10). The ripening phase is essential for flavor development and the costliest part of cheese production, as ripening is a slow process. Large, specialized facilities ensuring a stable environment in terms of temperature and humidity are required for storing the young cheeses for up to several months or even years. For example, the costs for a 9-month ripening period were estimated to be 500 to 800 € per ton of cheese. Therefore, short ripening times are desired, still allowing the complex biochemical reactions to occur, which facilitate flavor formation (11).

L. lactis and Lactococcus cremoris (formerly L. lactis subsp. cremoris [12]) have outstanding flavor-forming capacities and therefore constitute the main components of mesophilic cheese starter cultures. Nevertheless, their mesophilic nature limits the range of cheese variants that can be produced with these particular LAB (13). For example, Cheddar cheese is made using a mesophilic starter culture combined with a relatively high cooking temperature up to 39°C, and to ensure robust acidification at even slightly higher cooking temperatures, such as 39.5°C, S. thermophilus is often used to supplement the starter cultures (14–16). It is widely recognized that the lysis of LAB facilitates cheese ripening through the release of intracellular enzymes, and this is a rate-limiting step in flavor formation (10, 17–22). Generally, autolysis is highly strain dependent, and traditionally L. cremoris is more autolytic than L. lactis (21, 23). Consequently, mesophilic cheese starter cultures contain many LAB strains, typically L. cremoris, which autolyze well under the processing conditions (10, 22, 24, 25). Autolysis is usually initiated by environmental factors such as nutrient depletion (26), heat shock (27), or salt stress (28), which induce the expression of peptidoglycan (PG) hydrolases, so-called autolysins, that degrade the bacterial cell wall. In L. lactis and L. cremoris, two major autolysins have been reported, AcmA and AcmB, of which the former is considered to contribute most strongly to autolysis (29, 30).

Due to the complexity of the underlying mechanisms, stress tolerance is usually improved by applying random mutagenesis or evolutionary engineering (4, 5). In this context, adaptive laboratory evolution (ALE) has recently gained much attention as advancements in laboratory automation, sequencing technologies, and genome editing have emerged (31, 32). High-throughput sequencing technologies are vital for ALE experiments, as the beneficial mutations can be identified quickly and studied subsequently by editing the genome of the parent strain (33). ALE has become one of the most reliable methods for producing desirable phenotypes and gaining insight into the underlying mechanisms that control physiological stress responses. Last, this approach is particularly suitable for optimizing LAB which are intended to be applied in the food industry, as strains derived from ALE experiments are considered natural.

Here, we investigated if long-term ALE of L. lactis subsp. lactis bv. diacetylactis SD96 (SD96 in short), an industrial dairy strain (34), could be applied to obtain thermotolerant mutants with superior properties. ALE was carried out in milk to maintain essential plasmid-encoded traits, such as lactose metabolism or proteolytic activity. Two mutants were isolated, RD01 and RD07, which showed improved thermotolerance and autolysis, both desired industrial properties, with RD07 being superior in all aspects. The underlying molecular mechanisms were studied by identifying genetic and transcriptomic changes using next-generation sequencing.

(This research was conducted by Robin Dorau in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Ph.D. degree from the Technical University of Denmark [35].)

RESULTS

ALE results in strains that acidify milk faster at both low and high temperature.

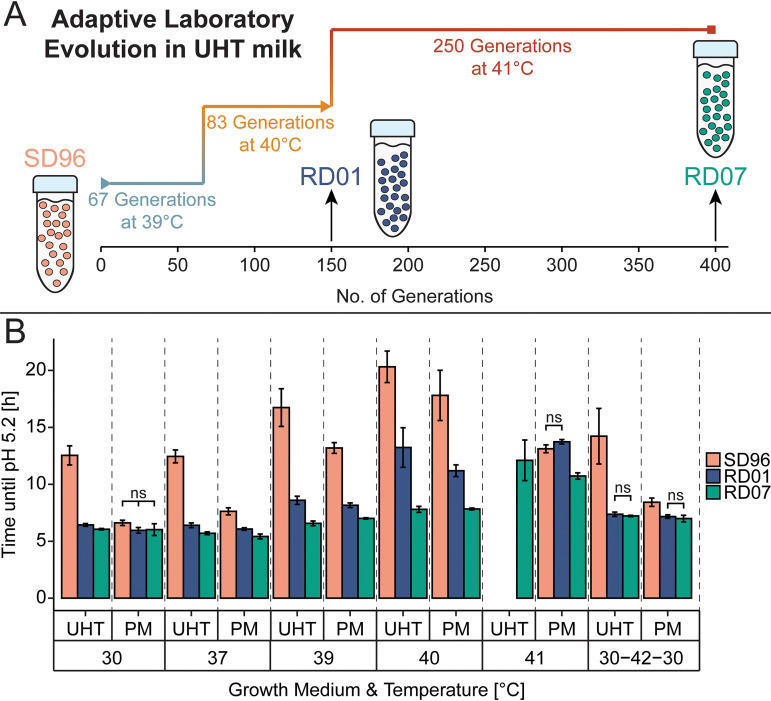

As a starting point for the ALE, we chose L. lactis SD96, a dairy isolate that grows well in milk and is generally insensitive to phage attacks (34). Although the optimum growth temperature for this particular strain is between 30°C and 37°C, growth was possible at 39°C in ultrahigh-temperature (UHT)-pasteurized milk and pasteurized milk (PM). For ALE, SD96 was subjected to growth at constant high temperature in UHT milk, resulting in the evolved strains RD01 and RD07. RD01 was isolated after approximately 150 generations, of which 67 were carried out at 39°C and 83 at 40°C. After isolation of RD01, the culture from which RD01 was isolated was propagated at 41°C for approximately 250 generations until RD07 was isolated. In total, RD07 was adapted for nearly 1.5 years, corresponding to approximately 400 generations (Fig. 1A). Upon isolation, the mutants were selected from agar plates as blue colonies, which indicates citrate utilization, to guarantee their ability to produce diacetyl.

FIG 1.

Overview and results of the central experiments carried out in this study. (A) Adaptive laboratory evolution (ALE) of SD96 (rose) at high temperature in ultrahigh-temperature (UHT)-pasteurized milk resulted in the evolved strains RD01 (blue) and RD07 (green). (B) Thermotolerance was improved as shown by decreased time until pH 5.2 was reached in UHT milk and pasteurized milk (PM). SD96 was compared to the evolved strains RD01 and RD07 at 30°C, 37°C, 39°C, 40°C, and 41°C. Additionally, the strains were tested by applying the temperature profile “30-42-30,” meaning that the strains were grown for 1 h at 30°C, followed by incubation for 1 h at 42°C and then returning to 30°C for 24 h. Experiments were carried out in three independent biological replicates. At the different temperatures, differences between the strains are statistically significant according to a t test (P < 0.05), except where data are indicated as nonsignificant (ns).

SD96 and the evolved strains RD01 and RD07 were tested in various milk fermentations. The time required for the strains to acidify to pH 5.2 was used to compare the mutants in UHT milk and PM (Fig. 1B). In UHT milk, adaptation was most apparent, as SD96 acidified this growth medium relatively slowly, even at low temperatures. At 30°C and 37°C, both evolved strains acidified UHT milk to pH 5.2 within approximately 6 h, while SD96 needed approximately 12 h, indicating that adaptation to the UHT milk environment had occurred. RD07 required the least time to reach pH 5.2 throughout all temperatures and was the only strain that could acidify UHT milk to pH 5.2 at 41°C (12.1 ± 1.8 h). In comparison, RD01 required approximately 1.7-fold longer to reach pH 5.2 at 40°C than RD07 (13.2 ± 1.7 h, and 7.8 ± 0.3 h, respectively). In addition to these experiments, as a simple approximation of a real-life cheese fermentation with an unusually high cooking temperature, we also examined the impact of a 1-h exposure to 42°C. A fresh 1% inoculum was added to UHT milk and left for 1 h at 30°C. This was followed by a 1-h exposure to 42°C, whereafter the culture was returned to 30°C, and pH was monitored until pH 5.2 was reached. The evolved strains acidified the milk approximately two times faster than SD96.

Because of the slow growth of SD96 in UHT milk, the effect of the high-temperature adaptation was more revealing when PM was used, in which SD96 acidified to pH 5.2 in roughly the same time as RD01 or RD07 at 30°C (SD96, 6.6 ± 0.2 h; RD01, 6.0 ± 0.3 h; RD07, 6.0 ± 0.5 h). Interestingly, at 40°C, SD96 was still able to acidify PM to pH 5.2 but required approximately 2.7-fold more time than at 30°C, while RD01 was only 1.9-fold and RD07 1.3-fold slower. At 41°C, reasonable acidification was observed only with RD01 and RD07, which needed 13.7 ± 0.2 h and 10.7 ± 0.3 h, respectively, which are 1.9-fold and 1.5-fold longer than at 30°C. When the 42°C heat shock treatment, as described above, was applied, RD01 and RD07 required approximately 1.2-fold less time than SD96 to reach pH 5.2.

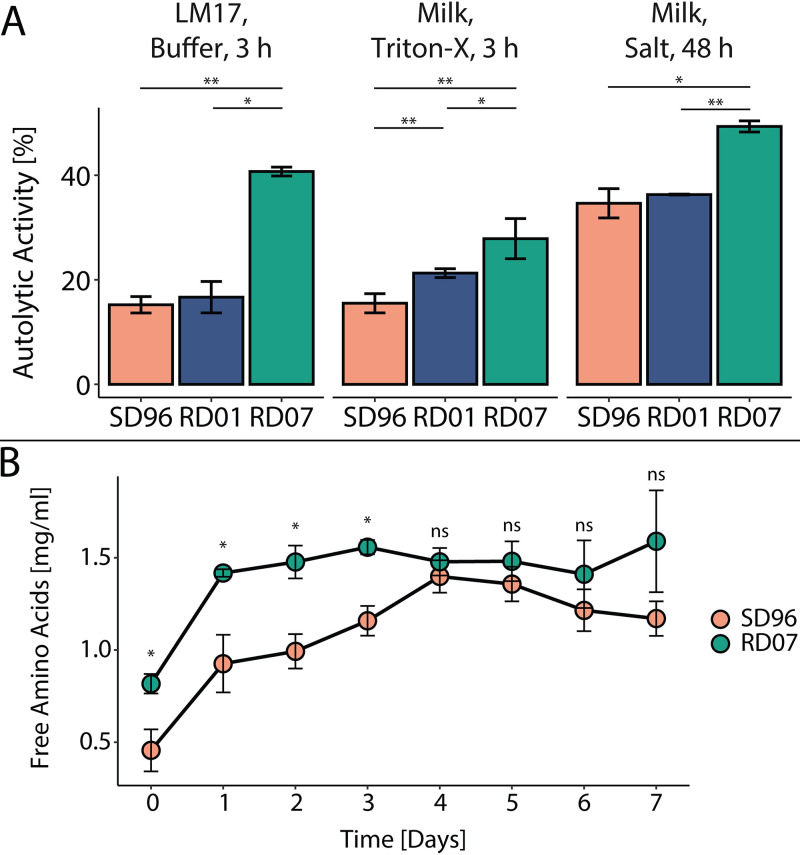

Adaptation of SD96 to elevated growth temperature leads to enhanced autolysis.

When characterizing growth in liquid cultures, we noticed a rapid drop in cell density after lactose depletion, and we speculated that this could result from autolysis. To examine this, we used previously reported methods for quantifying autolysis (36–39). In the data below, the autolytic activities are defined as the percent decrease in optical density at 600 nm (OD600) compared to the initial OD600 after 3 h at 30°C. Using M17 medium for cultivation, we found that RD07 showed 2.7-fold increased autolytic activity compared to SD96, while RD01 did not show significantly altered autolysis. (Fig. 2, left). The autolytic activity was also tested with cells isolated during milk fermentation at pH 5.2, which is similar to the fresh cheese curd environment, even though different amounts of residual lactose are present (11). Additionally, we added a surfactant to induce autolysis and determined autolytic activities of 15.5% ± 1.8%, 21.3% ± 0.8%, and 27.9% ± 3.8% for SD96, RD01, and RD07, respectively, revealing a trend similar to that previously observed (Fig. 2, middle). Last, we tested if RD07 also shows increased autolytic activity in a lactate buffer, simulating the conditions in the cheese curd (40). SD96 and RD01 showed similar autolytic activity after 48 h, but RD07 showed approximately 1.4-fold-increased autolysis compared to SD96 (Fig. 2, right).

FIG 2.

Autolysis and ripening of SD96 and the evolved strains RD01 and RD07. (A) Autolytic activity of SD96 (rose) and the evolved strains RD01 (blue) and RD07 (green) under different conditions. (Left) Autolysis after 3 h induced by nutrient depletion in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 7.0 using cells harvested during the exponential phase in M17. (Middle) Autolysis after 3 h induced by Triton X-100 in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 7.0 using cells harvested during milk fermentation at pH 5.2. (Right) Autolysis after 48 h induced by salt stress (0.5 M NaCl) in lactate buffer at pH 5.0 using cells harvested during milk fermentation at pH 5.2. (B) Ripening of model cheeses made with SD96 (rose) or RD07 (green). The release of free amino acids into the cheese matrix was measured using the OPA reagent. All values were determined from three biological replicates, and statistically significant differences determined by a t test are indicated with asterisks (ns, not significant [P > 0.05]; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005).

To evaluate if the increased autolysis of RD07 could contribute to accelerated cheese ripening, model cheese curds were prepared, and the release of free amino acids was measured as an indication for proteolysis and autolysis (Fig. 2B). With RD07, in the first 3 days, significantly higher free amino acid levels were observed, which were 1.8-fold to 1.3-fold higher than with SD96. After the fourth day, similar free amino acid levels were detected, indicating that complete proteolysis had been achieved.

Genome resequencing reveals plasmid loss and diverse mutations.

The evolved strains RD01 and RD07 were sequenced, and mutations in both the chromosome and the plasmids were compared to SD96 (see Section S1 in the supplemental material). The mutations are summarized in Table 1, and more details are given in Data Set S1 in the supplemental material. RD01 and RD07 were derived from the same lineage, and therefore, it was not surprising that they shared some mutations. Both strains had lost genetic material during the ALE through plasmid loss (pSD96_01, pSD96_03, pSD96_06, and pSD96_10) and a large chromosomal deletion (approximately 80 kb) (Data Set S2). RD01 and RD07 shared an interesting mutation in UDP-N-acetylmuramate-l-alanine ligase (MurC), which is involved in the biosynthesis of peptidoglycan (mutations RD01-4 and RD07-2). Furthermore, RD01 was found to have a mutation located 64 bp upstream of codY (RD01-1), potentially affecting transcription of this gene by altering the promoter region. In RD07, in total, eight mutations were identified (Table 1). Probably the most influential mutation, RD07-8, was located in purR, encoding the pur operon regulator PurR, a phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate (PRPP)-sensing transcriptional activator, and the mutation caused a glycine-to-serine substitution at position 206 (G206S).

TABLE 1.

Results of genome resequencing of the mutant strains RD01 and RD07

| Gene or protein | Mutation in RD01 | Identifier | Mutation in RD07 | Identifier |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| codY | Upstream | RD01-1 | ||

| relA | V469L | RD01-2 | ||

| EamA family transporter | Silent | RD01-3 | Silent | RD07-1 |

| murC | F54L | RD01-4 | F54L | RD07-2 |

| Chromosomal deletion | 1823878–1897135 | 1823878–1897135 | ||

| pheT | R546S | RD07-3 | ||

| Hypothetical protein | V957E | RD07-4 | ||

| DNA primase | A410S | RD07-5 | ||

| ftsH | Upstream | RD07-6 | ||

| rexA | D311Y | RD07-7 | ||

| purR | G206S | RD07-8 |

Mobile genetic elements encoding phage defense systems were lost in RD01 and RD07.

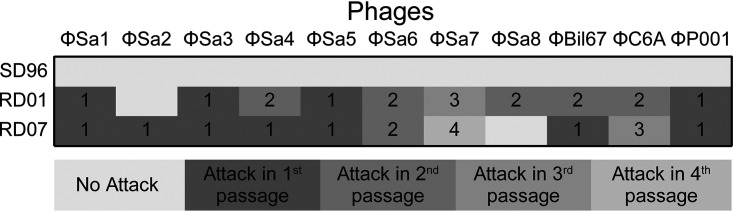

SD96 contains 10 plasmids, which encode, among others, the cell wall-bound proteinase PrtP and citrate permease CitP and carry lactose metabolism and phage resistance genes (Table S1). Plasmids pSD96_01, pSD96_06, and pSD96_10, which had been lost in RD01 and RD07, carried genes for phage resistance, such as a complete type I restriction-modification system (RMS) on pSD96_06 and two additional specificity subunits on pSD96_01 and pSD96_10. Additionally, the large chromosomal deletion (80 kb), lost in RD01 and RD07, contained a complete RMS (FTN78_RS09530 to FTN78_RS09570). The loss of phage resistance genes resulted in a sensitivity of RD01 and RD07 to 9 of more than 100 phages tested (Fig. 3), whereas SD96 was fully phage resistant. The nine phages which managed to infect RD01 and RD07 were ϕSa1, ϕSa3, ϕSa4, ϕSa5, ϕSa6, and ϕSa7 from Sacco’s internal collection (phage identifiers were changed due to confidentiality) and ϕBil67, ϕC6A, and ϕP001 from the Félix d’Hérelle Reference Center for Bacterial Viruses (Université Laval, Canada). The last three phages belong to the c2 group of the family Siphoviridae, which are rarely involved in failed dairy fermentations (41, 42). Additionally, RD01 was attacked by ϕSa8, but RD07 was resistant to this phage. In contrast, RD07 was sensitive to ϕSa2, but RD01 was not.

FIG 3.

Phage profiling of SD96 and the evolved strains JA24, RD01, and RD07. Over 100 phages were tested, of which 26 were from Félix d’Hérelle Reference Center for Bacterial Viruses (Université Laval, Canada). Phage profiling was performed by challenging liquid cultures of the three strains SD96, RD01, and RD07 with different phages. If a particular phage halted growth/acidification, this is indicated by “1” (attack in 1st passage). If growth/acidification occurred, the supernatant of the outgrown culture was used to infect a second culture, and if this second culture was affected, this is indicated by “2” (attack in 2nd passage). If not, the procedure was repeated. If the third or fourth culture was affected, this is indicated by “3” (attack in 3rd passage) or “4” (attack in 4th passage), respectively. However, if the culture withstood phage attack after three rounds of dilution, this is indicated by “no attack.”

RNA sequencing revealed strong changes in amino acid metabolism in RD01 and nucleotide metabolism in RD07.

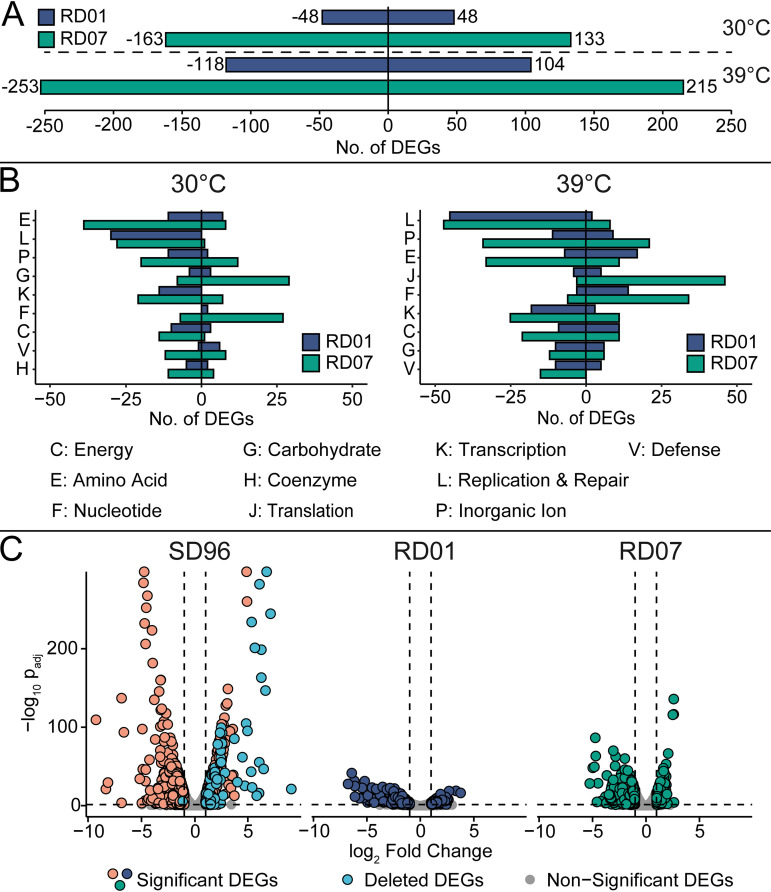

To characterize the changes that had taken place in the evolved strains, we decided to conduct a global transcription analysis for each of the strains. Sample distance and principal-component analysis (PCA) confirmed the clustering of the biological replicates and the data’s eligibility for analysis (Fig. S1 and S2). Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) analysis was conducted to evaluate the mutants’ global expression patterns (Fig. 4A and B). Therefore, significantly differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (absolute log2 fold change > 1 and adjusted P value [Padj] < 0.05) were assigned to COG categories, excluding the nondescriptive category Function Unknown (category S).

FIG 4.

Overview of the transcriptomics analysis using DESeq2. Only significant DEGs were considered, fulfilling the following criteria: absolute log2 fold change > 1 and Padj < 0.05. RD01 is shown in blue, RD07 in green, and SD96 in rose. (A) Total numbers of significant DEGs were derived from comparing RD01 and RD07 with SD96 at 30°C (top) and 39°C (bottom). Negative values indicate the number of downregulated genes, while positive values indicate upregulated genes. (B) COG analysis comparing RD01 and RD07 with SD96 at 30°C (left) and 39°C (right). Categories are as follows: C, Energy Production and Conversion; E, Amino Acid Metabolism and Transport; F, Nucleotide Metabolism and Transport; G, Carbohydrate Metabolism and Transport; H, Coenzyme Metabolism; J, Translation; K, Transcription; L, Replication and Repair; P, Inorganic Ion Transport and Metabolism; V, Defense Mechanisms. (C) Volcano plots showing DEGs for SD96 and the evolved strains RD01 and RD07, comparing expression at 30°C with expression at 39°C. Numbers of upregulated and downregulated DEGs are as follows: SD96, 348 and 370; RD01, 139 and 245; RD07, 101 and 191. Significant DEGs in SD96 located on regions deleted in RD01 and RD07 are shown in light blue. Corresponding COG analysis is shown in Fig. S3.

Comparing RD01 and RD07 with SD96 at 30°C revealed 133 upregulated and 163 downregulated genes in RD07, while RD01 showed 48 upregulated and 48 downregulated genes (Fig. 4A). Most of the DEGs were in the category Amino Acid Metabolism and Transport (category E), where RD07 showed 39 downregulated DEGs and 8 upregulated genes (Fig. 4B). Next, the category Replication and Repair (category L) was represented strongly in RD01 and RD07, with 30 and 28 downregulated genes and 0 and 1 upregulated gene, respectively, which could be explained by the loss of genetic material, since many genes located on the lost plasmids and the deleted 80-kb fragment belonged to this category. It was remarkable that RD07 had 29 upregulated genes in the categories Carbohydrate Metabolism and Transport (category G) and 27 upregulated genes in Nucleotide Metabolism and Transport (category F), while RD01 showed only 3 and 2 upregulated genes in these categories, respectively.

At 39°C, the numbers of DEGs were higher than at 30°C with 215 upregulated and 253 downregulated genes in RD07 and 104 upregulated and 118 downregulated genes in RD01 (Fig. 4A). Here, the category Replication and Repair (category L) was also strongly represented, with 45 downregulated genes in RD01 and 47 in RD07. Again, categories E and F showed remarkable differences between RD01 and RD07. In category E, 7 genes were downregulated in RD01 versus 33 in RD07, and in category F, 14 genes were upregulated in RD01 versus 34 in RD07. Surprisingly, category G was only weakly affected at 39°C in both strains. Interestingly, the category Translation (category J) contained 46 upregulated genes for RD07 but only 5 for RD01, indicating that protein biosynthesis was more affected in RD01 than in RD07. Changes in this category could also be due to the different growth rates of the strains at high temperatures.

DEGs, either upregulated or downregulated by high temperature, were determined for each strain by comparing gene expression at 30°C and 39°C (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, many significantly upregulated genes with large log2 fold changes in SD96 were located on the chromosomal region, which had been lost in RD01 and RD07 (“Deleted DEGs”), indicating that those genes imposed a burden on SD96 at 39°C without contributing to thermotolerance.

To summarize, the data revealed that at both 30°C and 39°C, RD07 showed more DEGs than RD01, but many categories were affected similarly. Differences between RD01 and RD07 were mostly related to amino acid and nucleotide metabolism (Fig. 4B). Compared to SD96, both mutants had lost an 80-kb chromosomal fragment carrying temperature-induced genes (Fig. 4C).

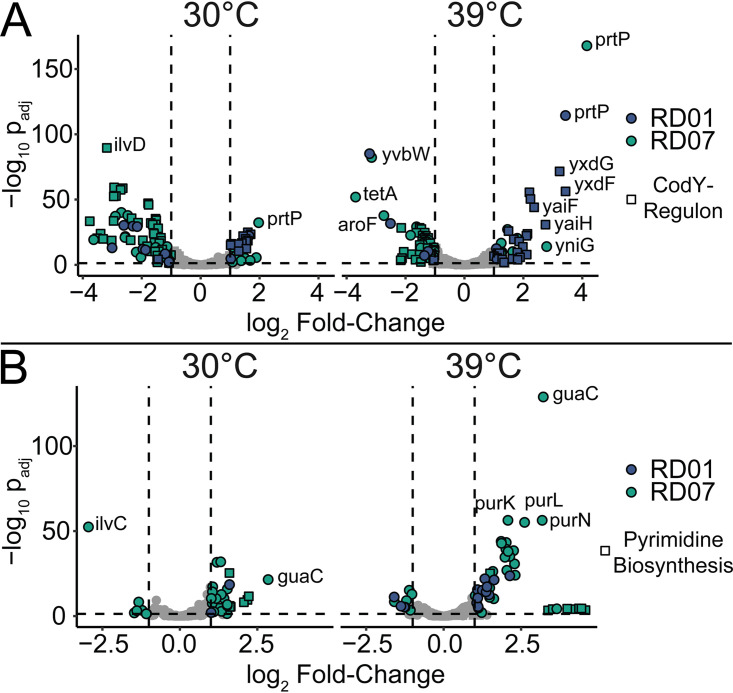

The CodY regulon is overexpressed in RD01, and nucleotide metabolism is overexpressed in RD07.

As the COG analysis revealed significant differences in amino acid and nucleotide metabolism in RD01 and RD07, we hypothesized that the genes under the regulation of transcription factors which were affected by mutations, CodY (RD01) and PurR (RD07), might be differentially expressed in the evolved strains. Therefore, we evaluated the expression of the genes belonging to COG categories E and F in detail (Fig. 5). Additionally, genes of the CodY regulon, as described elsewhere (43), were included.

FIG 5.

Differential expression of selected genes involved in amino acid and nucleotide metabolism. RD01 and RD07 were compared to SD96 at 30°C and 39°C. The mutants RD01 and RD07 are shown in blue and green, respectively. (A) Genes belonging to the COG category Amino Acid Metabolism and Transport (category E) and CodY regulon (squares). (B) Genes belonging to the COG category Nucleotide Metabolism (category F). Squares represent pyrimidine biosynthesis genes.

In RD01, a nearly 3-fold reduction of codY expression was detected, which did not seem to be influenced by growth temperature (Table S2). Accordingly, derepression of codY-regulated genes was detected, including dppA, ilvD, gltD, icD, citB, and prtP (Fig. 5A and Data Set S3). In contrast, in RD07, many of these genes were downregulated. One striking exception is the expression of prtP, the cell wall bound and plasmid-encoded protease, which is essential for fast growth in milk. At 30°C, prtP was upregulated in RD01 (3.0 ± 1.1-fold) and RD07 (4.0 ± 1.1-fold), and even more at 39°C, i.e., 10.6 ± 1.1-fold and 18.4 ± 1.1-fold, respectively. In agreement with this observation, an increase in proteolytic activity was observed for RD01 and RD07 (28% ± 3% and 61% ± 6%, respectively), compared to SD96 (Section S2).

Only RD07 displayed significant changes in gene expression in nucleotide metabolism (Fig. 5B and Data Set S4). The purine biosynthesis genes were significantly upregulated in RD07 at 30°C and 39°C with approximately 2-fold and 4-fold increases. Notably, the guaC gene stands out with high differential expression at both 30°C (7.2 ± 1.2-fold) and 39°C in RD07 (9.3 ± 1.1-fold). Interestingly, genes belonging to the pyrimidine metabolism were also upregulated, particularly at 39°C.

RD01 provides appealing flavor in high-temperature-cooked Havarti-style cheese.

As an initial test for its applicability in a starter culture, the evolved strain RD01 has been tested in cheese trials at Arla Foods in Denmark. Two batches of cheese were made, including and excluding the evolved strain. Before inoculation, RD01 was mixed 1:5 (vol/vol) with a commercially available undefined mesophilic starter culture (Flora Danica; Chr. Hansen, Hørsholm, Denmark). Havarti-style cheeses were made according to Arla’s internal protocols using an exceptionally high cooking temperature of 39.5°C. According to a panel of six experts, the cheeses involving RD01 had a taste superior to that of the control cheeses (Flora Danica only). Cheese trials with RD07 are planned.

DISCUSSION

RD01 and RD07 are unique thermotolerant strains with industrially relevant phenotypes.

We report two thermotolerant strains of L. lactis subsp. lactis biovar diacetylactis SD96, RD01 and RD07, obtained by using high-temperature ALE. Previously, ALE has been used to increase the thermotolerance of L. cremoris MG1363, resulting in the thermotolerant mutant TM29. A maximal growth temperature of 40°C in GM17 was realized in that study, but preincubation at high temperature was required to allow slow growth at 40°C (44). So far, this has been the only example where the maximal growth temperature of an LAB has been increased by using ALE. As an alternative to ALE, short-term exposure to sublethal high temperatures was frequently used to obtain strains with improved survival at high temperatures based on spontaneous mutations (40, 45, 46). Comparing our mutants, RD01 and RD07, with other thermotolerant L. lactis strains is complicated, as different strains, experimental setups, or success criteria have been used (45–51).

Adaptation to growth in UHT milk resulted in dramatic downregulation of CodY and overexpression of PrtP.

The different heat treatments used for preparing UHT milk and PM altered the milk proteins’ availability for utilization by LAB. For example, it has been shown that caseins and whey proteins are more denatured after UHT treatment than pasteurization and experience temperature-induced interactions (52–54). Those structural differences are believed to affect L. lactis’ ability to metabolize the milk proteins (55). Consequently, we hypothesize that SD96 suffered from amino acid starvation when grown in UHT milk, which RD01 and RD07 overcame by different means. This hypothesis could be supported by the observation that supplementing UHT milk with peptone was beneficial for acidification using SD96 (Fig. S4). In RD01, we detected strong downregulation of codY expression, causing upregulation of amino acid metabolism. Furthermore, bifunctional (p)ppGpp synthetase (RelA) was mutated in RD01 (RD01-2), which plays a crucial role in modulating the stringent response by mediating the synthesis of the second messenger (p)ppGpp (56). RelA senses the availability of amino acids by being activated by uncharged tRNAs (57, 58). These two mutations strongly support the hypothesis that SD96 starved for amino acids during ALE in UHT, which was overcome in RD01 by downregulating codY and mutating RelA. Surprisingly, RD07 did not have mutations affecting amino acid metabolism, but we found the cell wall-bound proteinase PrtP to be upregulated 18-fold, which might be sufficient to overcome amino acid limitation in UHT milk.

The autolytic activity of RD07 is comparable to that of other highly autolytic strains.

Besides showing increased thermotolerance, RD07 appeared more autolytic than SD96, which is highly unusual as typically L. cremoris are considered more autolytic than L. lactis. Compared to L. cremoris CO and 2250, two highly autolytic strains, with 45% and 36% autolytic activities, respectively, RD07 showed similar autolytic activity (40.7% ± 0.9%). Cheese trials will reveal how RD07 affects cheese ripening compared to SD96. Since the role of autolysis in cheese ripening is still discussed in the scientific literature, SD96 and RD07, as nearly isogenic strains with different autolytic behavior, present an interesting test bed for studying the role of autolysis in flavor formation during cheese ripening (59).

Previously, Smith et al. described thermotolerant mutants of L. cremoris MG1363 and the industrial strain L. cremoris ASCC892185, which were more sensitive to osmotic pressure, indicating increased autolytic properties (45). Analogously, Spus et al. isolated spontaneous thermotolerant mutants of Lactobacillus helveticus DSM 20075 and revealed that temperature adaptation led to improved autolytic properties of the strain (40). In summary, these studies and our findings suggest a conserved connection between thermotolerance and autolysis in LAB, which may be independent of how thermotolerance was achieved.

Altered amino acid metabolism might be responsible for increased autolysis.

Huang et al. showed that l-Ala starvation caused an autolytic phenotype by preventing cross-linking of the PG units (60). RD01 and RD07 both have the same mutation (F54L) in MurC, the enzyme responsible for incorporating l-Ala into PG. This mutation might influence the PG structure, and thereby the mutants’ phenotypes, by affecting the substrate specificity or activity of MurC (61–63). Solopova et al. established that l-Asp availability, modulated by pyrimidine metabolism, influences the cell wall rigidity of L. lactis and thus its autolytic properties (64). In RD07, but not in RD01, pyrimidine biosynthesis was upregulated, which might contribute to its autolytic phenotype, as pyrimidine biosynthesis requires l-Asp, which is essential for cross-linking PG units, and a limited supply might lead to a fragile cell wall. Interestingly, SD96 showed a tendency to form globular cell aggregates, while RD01 and RD07 did not, which indicates that cell surface properties of RD01 and RD07 were altered (Fig. S5).

Transcriptional analysis into the expression of autolysins revealed no significant alterations when RD07 and SD96 were compared. As autolysis has generally been shown to correlate with the presence of temperate prophages, we investigated the presence of putative prophages in SD96 (65). For this, we mined the genome of SD96 using the PHASTER tool (66, 67). Seven prophages were identified, of which five were intact according to the tool (Table S3). Only prophages 1 and 3 encode lysin genes, which were expressed at low levels in all strains and conditions (<40 transcripts per million [TPM]), which did not suggest that prophages were responsible for the increased autolysis of RD07. Since the autolysis experiments were carried out in a buffer without sugars or nutrients, we further exclude gene expression changes as a cause of the lytic phenotype, as such changes require much ATP.

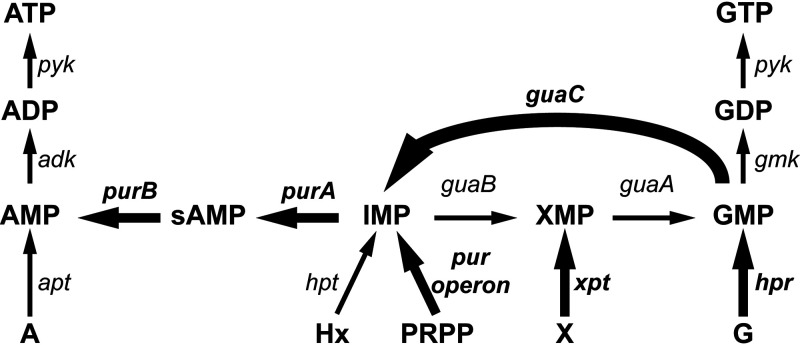

Changes in nucleotide metabolism possibly result in a multistress-resistant phenotype in RD07.

Previously, purine metabolism and, more specifically, the excess of guanine nucleotides were shown to induce stress sensitivity toward acid and heat stress in lactococci (51). Since, in comparison to RD01, RD07 stands out with many upregulated genes in the category Nucleotide Metabolism and Transport, we investigated this category further. We examined the genes involved in guanine biosynthesis or scavenging. Among adk, apt, gmk, guaA, guaB, guaC, hpr, hpt, pyk, xpt, and the pur genes, only guaC, xpt, and the pur genes were differentially expressed in RD07. Most strikingly, compared to SD96 and RD01, guaC and the pur genes were upregulated in RD07. Overall, this expression pattern could result in a reduced guanidine nucleotide pool, as overexpression of guaC, purA, and purB would favor adenine nucleotide synthesis (Fig. 6). A similar observation was described previously, where the inactivation of guaA led to multistress resistance (68, 69). Consequently, we speculate that a reduced guanine nucleotide pool in RD07 might be the reason for its heat-resistant phenotype.

FIG 6.

Scheme of purine metabolism with emphasis on the differential expression in RD07. Compared to SD96 and RD01, in RD07, guaC is strongly upregulated (thick arrow), while the pur genes, xpt, and hpr were only moderately upregulated (medium arrows), and the remaining genes were unaltered (thin arrows). This differential expression pattern suggests a reduced GMP pool, which is beneficial for stress tolerance. adk, adenylate kinase; apt, adenine phosphoribosyltransferase; gmk, guanylate kinase; guaA, GMP synthase; guaB, IMP dehydrogenase; guaC, GMP reductase; hpt, hypoxanthine/guanine phosphoribosyltransferase; hpr, hypoxanthine/guanine phosphoribosyltransferase; purA, adenylosuccinate synthase; purB, adenylosuccinate lyase; pur operon, purCSQLF, purMN, and purDEK; pyk, pyruvate kinase; xpt, xanthine phosphoribosyltransferase. A, adenine; Hx, hypoxanthine; PRPP, phosphoribosyl diphosphate; X, xanthine; G, guanine; I, inosine; sAMP, adenylosuccinate. xMP, monophosphate; xDP, diphosphate; xTP, triphosphate (where x is A, G, I, or X). Modified from reference 51.

Other unique mutations in RD07 are involved in stress response mechanisms.

Mutation RD07-6 lies in the promoter region of hflB/ftsH, coding for ATP-dependent zinc metalloprotease FtsH, which is involved in cellular stress regulation (70). This enzyme is essential for stress resistance and thermotolerance, as it contributes to the quality control of cytosolic and membrane proteins (71, 72). The deletion of FtsH in Lactobacillus plantarum resulted in a heat-sensitive phenotype, while overexpression produced a robust strain (73). Our transcriptomic analysis revealed that FtsH was downregulated in RD07 (Table S2). This observation is surprising, as the opposite would be expected. Potentially, FtsH has other functions in L. lactis than in Lactobacillus plantarum and is, for instance, involved in regulating cell envelope composition, as suggested previously (74). Mutation RD07-7 caused a point mutation (D311Y) in RexA, an ATP-dependent exonuclease (subunit A) which is involved in the repair of double-strand breaks (75). This mutation might be advantageous for repairing DNA damage originating from reactive oxygen species at high temperatures (13). Interestingly, increased expression of chaperones or transporter proteins, as observed in TM29, was not detected in RD07 (44).

Unfortunately, genetic manipulation of SD96 was hindered by a low transformation efficiency, and thus, unambiguous evidence for the mutations’ effects on SD96 leading to thermotolerance could not be produced. Hence, we decided to integrate the genomics analysis with RNA sequencing-based transcriptomics analysis at low and high temperatures to identify the most likely underlying reason for improved growth in UHT milk and thermotolerance.

In conclusion, we have described two naturally evolved strains, namely, RD01 and RD07, with increased thermotolerance and autolytic properties derived from L. lactis subsp. lactis bv. diacetylactis SD96 by ALE. Both strains showed improved acidification in milk, with RD07 being the most thermotolerant and efficient strain. This strain can efficiently acidify milk at 41°C, which is rare for a mesophilic L. lactis subsp. lactis strain. Besides having an increased phage attack susceptibility, the mutants have kept their ability to grow independently in milk and produce flavor compounds from citrate. Moreover, we demonstrated that RD07 is more autolytic than SD96 and that it has the potential to accelerate cheese ripening, which will be studied in more detail in future cheese trials. Genome and RNA sequencing revealed genomic and transcriptomic changes, which were established during ALE. Both mutants seem to have found different strategies for improved growth in UHT milk and increased survival at high temperatures. RD07, the most thermotolerant strain, also showed the most complex set of mutations, and their potential effects on the phenotype are discussed. We argue that the drainage of the guanidine nucleotide pool is a likely cause of the thermotolerance of RD07. Other mutations involved in DNA and protein quality control mechanisms likely support the stress resistance of this strain.

To summarize, we showed how ALE could be applied for producing promising strains for the starter culture industry. As the mutants are based on an industrial strain already used in many starter cultures, they are readily applicable for cheese production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Adaptive laboratory evolution.

L. lactis subsp. lactis biovar diacetylactis SD96 was cultivated on M17 agar supplemented with 0.5% lactose (LM17), and a single colony was used to start two separate cultures in 9 ml UHT milk. Generally, when the milk was coagulated, the culture was considered fully grown with approximately 1010 cells (76). Fully grown cultures were homogenized by shaking and propagated in 9 ml fresh UHT milk. Then the procedure was repeated. Every week, the culture was saved by mixing a fully grown culture with 50% glycerol 1:1 and storing it at −80°C. When required, freshly inoculated cultures were stored at −20°C.

The culture was kept continuously at high temperatures. To avoid a long time between propagation steps, the coagulated, fully grown culture was propagated by diluting 10-fold into 9 ml fresh UHT-milk, which corresponds to 3.32 generations per propagation step. Initially, SD96 was grown at 39°C, and the coagulation of the UHT milk was observable after approximately 48 h. Twenty propagation steps were conducted until coagulation was observable after ca. 24 h, and then the temperature was increased to 40°C, again resulting in coagulation after ca. 48 h. After 25 propagation steps at 40°C (45 propagation steps in total, 150 generations), coagulation was observable after 24 h, and RD01 was isolated. RD01 was isolated approximately 5 months after the ALE was started. Subsequently, the temperature was increased to 41°C, and another 75 propagation steps (120 propagation steps in total, 400 generations) were needed until solidification was visible after 24 h, which was when RD07 was isolated. Overall, ALE was carried out for more than 1 year.

When the cultures began to grow more slowly than before, judged by visual inspection, they were enriched for protease-positive strains by plating on UHT milk agar (1% UHT milk, 1.5% agar) and subsequent harvesting of the colonies. On the UHT agar, protease-positive strains formed larger colonies so that after harvesting, they constituted a larger fraction of the entire culture. After the enrichment step, the fraction of protease-positive strains was increased by approximately 7-fold (Section S3). This enrichment was done twice during the ALE at high temperatures.

Isolation of evolved strains.

The evolved strains RD01 and RD07 were isolated from the propagated cultures at the time points indicated above. As plasmid loss was reported to occur frequently during propagation in milk (76), we screened for strains that grew fast in milk and utilized citric acid. Therefore, cultures were plated on medium containing 1% (wt/vol) skim milk powder, 0.25% peptone, 0.25% lactose, 1.5% agar, 0.1% potassium ferricyanide, 0.025% ferric citrate, and 0.02% sodium citrate, as adapted from reference 77. The skim milk powder, peptone, lactose, and agar were mixed and dissolved. Then, the pH was adjusted to 6.5, and the mixture was autoclaved and cooled to 60°C. A 10% potassium ferricyanide solution and a solution containing 2.5% ferric citrate and 2.5% sodium citrate were steamed at 100°C for 30 min and added 1:100 into the agar solution. Large, dark blue colonies, indicating efficient lactose and citric acid utilization, were streaked on medium containing 1% UHT milk and 1.5% agar. Protease-positive strains formed larger colonies on this agar than protease-negative strains. A simple coagulation test confirmed several candidates. For this, 1 ml UHT milk was inoculated with a single colony and incubated at 30°C overnight. When the milk was fully coagulated, the strain was considered protease positive. Lastly, the thermotolerance of several isolates fulfilling the above criteria was assessed by measuring the acidification curve at the temperatures applied during ALE using 96-well microtiter plates with integrated chemical, optical pH sensors (HydroPlate HP96U; PreSens Precision Sensing GmbH, Germany), in combination with a Tecan Infinite 200 Pro microplate reader (Tecan Trading AG, Switzerland). From those measurements, the fastest strain was chosen and designated RD01 or RD07.

Milk acidification.

Cultures were inoculated from LM17 agar into fresh milk (UHT milk, PM, or reconstituted skim milk [RSM]) and, as a first preculture, cultivated at 30°C for 16 h. A second preculture was started by diluting the first preculture 1:100 into fresh milk, followed by incubation at 30°C for 16 h. The number of CFU was determined before inoculation (Fig. S6). Then, the cultures were inoculated into prewarmed fresh milk using a 1:100 dilution. The cultures were equipped with a pH probe, and acidification was monitored for 20 h using an iCinac instrument. For cultivations applying the 42°C heat shock, the cultures were transferred between two water baths, one at 30°C and one at 42°C, so that a rapid temperature change happened. Before inoculation, the pH probes were calibrated at the temperature applied during milk fermentation. From the acidification curve, the time needed to reach pH 5.2 was calculated and presented.

Surfactant-induced autolysis.

Milk fermentation was carried out using RSM with 10% milk solids after autoclaving at 121°C for 5 min. From an LM17 plate, the first preculture in RSM was inoculated using a single colony and incubated at 30°C for 16 h. This preculture was used to inoculate a second preculture in RSM using 100-fold dilution, followed by incubation at 30°C for 16 h. The second preculture was used to inoculate 50 ml RSM 1:100, followed by incubation at 30°C. The pH was monitored using an iCinac instrument. When pH 5.20 was reached, the cultures were put on ice to stop the fermentation. Then, the cultures were diluted 10-fold into a cold EDTA solution (2 g/liter, pH 12.0) to dissolve the casein. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C and washed again using EDTA solution to remove residual casein. The obtained pellets were washed twice using cold sodium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.0), and OD600 was determined. Finally, the cells were resuspended to an OD600 of 1 in sodium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.0) supplemented with 0.05% Triton X-100. Autolysis was determined by observing the decrease of intact cells by measuring OD600 over time. Two hundred microliters of each suspension was transferred into a honeycomb microplate, and OD600 was measured every 20 min using a Bioscreen C analyzer while incubating at 30°C for 36 h. Before each measurement, the plates were shaken vigorously to ensure homogenous suspension of the cells. Two technical replicates were analyzed. Autolytic activity, defined as a decrease in OD600 after the first 3 h (in percent), was derived from the data.

Ripening of model cheeses.

The effect of the adaptive laboratory evolution on cheese ripening was estimated using model cheeses prepared as described by Garbowska et al. with alterations (78). The model cheeses were prepared using three independent replicates. Fresh pasteurized milk with 1.5% fat was purchased 1 day after filling and immediately used for the experiment. In sterile centrifugation tubes, 250 ml milk was inoculated with 2.5 ml overnight culture of either SD96 or RD07. After 30 min incubation at 30°C, sterilized rennet from Mucor miehei (Sigma-Aldrich; R5876) was added to a final concentration of 0.008% (wt/vol), followed by incubation at 30°C for 30 min. The resulting curds were cut using sterile L-shaped cell spreaders as follows: first, the curds were cut vertically into four equally sized pieces using a cross pattern, and second, by rotating the spreader at three vertical positions, the curds were cut horizontally into 20 equally sized pieces. Immediately after cutting, the curds were incubated at 39°C for 1 h to facilitate syneresis. Afterward, the curds were centrifuged at 20 × g for 3 min, and the whey was removed by decanting. The resulting soft curds were cut into four equally sized pieces and washed with 150 ml sterile water (30°C) by shaking for 2 min, followed by a second centrifugation step using the same conditions. The water was removed by decanting, and the pressed curds were submerged with sterile water and equipped with a pH probe (iCinac). The curds were returned to a 30°C water bath and incubated until pH 5.20 was reached. After reaching the desired pH, the water was removed, and the curds were suspended in a brine solution (270 g/liter NaCl) and incubated at 20°C for 5 min. The brine solution was removed by decanting after centrifugation (100 × g, 3 min). Next, the curds were transferred into sterile 100-ml flasks and incubated at 30°C for 1 week. The relatively high temperature was chosen to accelerate the experiment. Whey was removed regularly. Samples were taken daily and stored at −20°C until analysis.

During the analysis, the curds were kept on ice. The curds were resuspended with a 2-fold amount of water (vol/wt) and homogenized using a FastPrep at maximal speed (6.5 m/s) for 1 min. The homogeneous mixtures were centrifuged for 2 min at 20,000 × g, and the supernatants were filtered with 0.45-μm syringe filters. The resulting extracts were diluted 100-fold with water, and eventually, 10 μl was mixed with 100 μl o-phthaldialdehyde (OPA) reagent (Sigma-Aldrich; P0532). After 2 min incubation at 20°C, the fluorescent intensity was measured (excitation, 430 nm; emission, 455 nm). An amino acid standard (Sigma, Supelco; AAS18) ranging from 5 μg/ml to 100 μg/ml was used for quantification.

Phage profiling.

Phage profiling was carried out at Sacco S.r.l. using the internal comprehensive phage collection. The collection comprised over 100 phages, of which 26 were from the Félix d’Hérelle Reference Center for Bacterial Viruses, Université Laval, Canada, including ϕbIL170, ϕP008, ϕsk1, ϕ712, ϕhp, ϕc2, ϕbil67, ϕrlt, ϕeb1, ϕQ54, ϕml3, ϕC6A, ϕTuc2009, ϕP369, ϕ949, ϕP335, ϕP270, ϕP107, ϕ1706, ϕ936, ϕul36, ϕp2, ϕP087, ϕ1483, ϕBK5-T, ϕP001. Single phages were contained in whey obtained from infected strains and filtered before use (0.4 μm). Phages were mixed in pools of five to seven phages. Five milliliters of RSM supplemented with 0.1% yeast extract, bromcresol green, and bromcresol purple was inoculated with 100 μl of a fully grown culture in RSM. Next, 100 μl of whey containing a phage pool or a single phage was added, followed by incubation at 30°C in a water bath. Acidification was monitored by observing the milk’s color change in a 96-well plate using a custom-made pH scanner. When acidification failed using a phage pool, the single phages contained in the pool were tested individually. Each pool or single phage was propagated four times as follows. When the milk was acidified successfully, meaning that no phage had attacked or the attack happened late during the fermentation, the culture was centrifuged (5,000 × g, 10 min), and the whey was collected and used as described above for infecting a new culture. In this manner, attacking phages were concentrated and identified, even if they required a higher titer for attacking than was initially present.

DNA isolation and genome resequencing.

De novo sequencing of SD96 is described elsewhere (34). Further bioinformatics analysis was carried out by homology search using BLAST, and phage defense genes were identified using a database containing lactococcal phage defense proteins, mapped to the genome of SD96 (79, 80). Genome resequencing of the evolved strains was performed as described previously with minor modifications (34). Cells from the early stationary phase were harvested from LM17 broth. Cell growth was monitored by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600). The cell wall was digested for 16 h at 22°C using 0.5 mg/ml lysozyme in Tris-NaCl buffer (10 mM each, pH 8.0) with 1% Triton X-100 and 10 mM EDTA. DNA was then isolated using a genomic DNA purification kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific; product number K0512), following the standard protocol with minor modifications. The chloroform-precipitated cell lysate was centrifuged for 15 min at 20,000 × g instead of 2 min. Sequencing was carried out by BGI China on an Illumina HiSeq 4000 platform using PE150 PCR-free libraries. The raw paired-end 150-bp reads were processed using Geneious Prime (version 2019.1.3) (81). First, adapter sequences and low-quality sequences were trimmed from both ends, and, finally, reads shorter than 50 bp were discarded. The reads were assembled to the chromosome and plasmids of SD96 (accession numbers NZ_CP043518 to NZ_CP043528) using Bowtie2 (version 2.3.0) in Geneious (82). Next, variant calling was performed using the respective function in Geneious accepting variants with >95% variant frequency. For identifying false-positive mutations, variant calling was also performed using sequencing data from SD96 using the same methods as for the mutants. Mutations occurring in both evolved strains and SD96 were not considered in the analysis.

RNA isolation, sequencing, and differential expression analysis.

RNA sequencing was carried out for SD96, RD01, and RD07 grown in RSM at 30°C and 39°C. Those conditions were chosen to guarantee proper growth for all strains. At 39°C, the growth of SD96 was severely inhibited but measurable after a longer lag phase than the other strains. In praxis, 10 ml RSM was inoculated with LM17 using a single colony and incubated for 16 h at 30°C (first preculture). A second preculture was inoculated from the first using a 100-fold dilution. The second preculture was used to inoculate 50 ml prewarmed RSM. Growth was monitored spectrophotometrically (OD600) after 10-fold dilution in EDTA solution (2 g/liter, pH 12.0), and the pH was monitored simultaneously using an iCinac instrument as described above. When the cultures reached the exponential phase (OD600, 0.7 to 0.9), cells were harvested. Thus, 10 ml of the culture were withdrawn, immediately cooled on ice, and centrifuged at 4°C (5,000 × g, 10 min). The resulting pellet was quickly resuspended in RNAlater solution (Invitrogen) and stored at 4°C. Half of the collected sample was used for isolating RNA using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen) according to the protocol “Purification of total RNA from bacteria (RY28 Nov-06).” The following steps, including RNA sequencing, were carried out at BGI China. rRNA was removed using the Ribo-off rRNA depletion kit (bacteria) from Vazyme. RNA sequencing was carried out using a PE100 library on a BGISEQ (DNBseq Technology) platform, resulting in paired-end 100-bp reads. Next, quality trimming and mapping to the SD96 genome were carried out in Geneious, as described above. Raw-read counts (reads per kilobase per million [RPKM], fragments per kilobase per million [FPKM], and TPM) were calculated in Geneious using the built-in Calculate Expression Levels feature. For differential gene expression analysis, raw-read counts were exported and analyzed manually using the DESeq2 package in RStudio (83). Log2 fold changes and corresponding log2-fold standard errors were obtained. The adjusted P value (Padj) was considered for evaluating the confidence of the differential expression values. Clusters of Orthologous Groups analysis was carried out by annotating all coding sequences (CDS) of SD96 using the eggNOG-mapper v2 (84) based on eggNOG v5.0 clusters and phylogenies (85). CDS which were not assigned to a COG category were excluded from the analysis. Furthermore, CDS located on lost genetic elements in RD01 and RD07 were treated separately during the analysis.

Data availability.

All experimentally generated data are included in this article or its supplemental files. Sequencing data are publicly available, including DNA sequencing results of RD01 (SRR13214404) and RD07 (SRR13214403) and the RNA sequencing data set (BioProject accession number: PRJNA670051).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the support from Sacco S.r.l. through which the phage profiling of SD96, RD01, and RD07 was realized.

We thank Fabio Dal Bello and Per Dedenroth Pedersen for accepting R.D. as a guest researcher and Donatella Chirico, Giovanni Eraclio, and Simona Cislaghi for technical support.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Christian Solem, Email: chso@food.dtu.dk.

Danilo Ercolini, University of Naples Federico II.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kindstedt PS. 2017. The history of cheese, p 3–19. In Papademas P, Bintsis T (ed), Global cheesemaking technology: cheese quality and characteristics. John Wiley & Sons Ltd., Hoboken, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- 2.United States Department of Agriculture. 2019. Dairy: world markets and trade.

- 3.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2019. OECD-FAO agricultural outlook 2019-2028—dairy and dairy products.

- 4.Bachmann H, Pronk JT, Kleerebezem M, Teusink B. 2015. Evolutionary engineering to enhance starter culture performance in food fermentations. Curr Opin Biotechnol 32:1–7. 10.1016/j.copbio.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johansen E. 2018. Use of natural selection and evolution to develop new starter cultures for fermented foods. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol 9:411–428. 10.1146/annurev-food-030117-012450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fox PF, Mcsweeney PLH. 2017. Cheese: an overview, p 5–21. In McSweeney PLH, Fox PF, Cotter PD, Everett DW (ed), Cheese: chemistry, physics and microbiology, 4th ed. Elsevier Ltd., Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelly AL, Huppertz T, Sheehan JJ. 2008. Pre-treatment of cheese milk: principles and developments. Dairy Sci Technol 88:549–572. 10.1051/dst:2008017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Panthi RR, Jordan KN, Kelly AL, Sheehan JJD. 2017. Selection and treatment of milk for cheesemaking, p 23–50. In McSweeney PLH, Fox PF, Cotter PD, Everett DW (ed), Cheese: chemistry, physics and microbiology, 4th ed. Elsevier Ltd., Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fagan CC, O’Callaghan DJ, Mateo MJ, Dejmek P. 2017. The syneresis of rennet-coagulated curd, p 145–177. In McSweeney PLH, Fox PF, Cotter PD, Everett DW (ed), Cheese: chemistry, physics and microbiology, 4th ed. Elsevier Ltd., Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parente E, Cogan TM, Powell IB. 2017. Starter cultures: general aspects, p 201–226. In McSweeney PLH, Fox PF, Cotter PD, Everett DW (ed), Cheese: chemistry, physics and microbiology, 4th ed. Elsevier Ltd., Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McSweeney PLH. 2017. Biochemistry of cheese ripening: introduction and overview, p 379–387. In McSweeney PLH, Fox PF, Cotter PD, Everett DW (ed), Cheese: chemistry, physics and microbiology, 4th ed. Elsevier Ltd., Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li TT, Tian WL, Gu CT. 2021. Elevation of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris to the species level as Lactococcus cremoris sp. nov. and transfer of Lactococcus lactis subsp. tructae to Lactococcus cremoris as Lactococcus cremoris subsp. tructae comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 71:e004727. 10.1099/ijsem.0.004727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen J, Shen J, Solem C, Jensen PR. 2013. Oxidative stress at high temperatures in Lactococcus lactis due to an insufficient supply of riboflavin. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:6140–6147. 10.1128/AEM.01953-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ong L, Lawrence RC, Gilles J, Creamer LK, Crow VL, Heap HA, Honoré CG, Johnston KA, Samal PK, Powell IB, Gras SL. 2017. Cheddar cheese and related dry-salted cheese varieties, p 829–863. In McSweeney PLH, Fox PF, Cotter PD, Everett DW (ed), Cheese: chemistry, physics and microbiology, 4th ed. Elsevier Ltd., Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michel V, Martley FG. 2001. Streptococcus thermophilus in Cheddar cheese—production and fate of galactose. J Dairy Res 68:317–325. 10.1017/s0022029901004812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stokes D, Ross RP, Fitzgerald GF, Coffey A. 2001. Application of Streptococcus thermophilus DPC1842 as an adjunct to counteract bacteriophage disruption in a predominantly lactococcal Cheddar cheese starter: use in bulk starter culture systems. Lait 81:327–334. 10.1051/lait:2001107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blaya J, Barzideh Z, LaPointe G. 2018. Symposium review: interaction of starter cultures and nonstarter lactic acid bacteria in the cheese environment. J Dairy Sci 101:3611–3629. 10.3168/jds.2017-13345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crow VL, Coolbear T, Gopal PK, Martley FG, McKay LL, Riepe H. 1995. The role of autolysis of lactic acid bacteria in the ripening of cheese. Int Dairy J 5:855–875. 10.1016/0958-6946(95)00036-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilkinson MG, Guinee TP, O’Callaghan DM, Fox PF. 1994. Autolysis and proteolysis in different strains of starter bacteria during Cheddar cheese ripening. J Dairy Res 61:249–262. 10.1017/S0022029900028260. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Donovan CM, Wilkinson MG, Guinee TP, Fox PF. 1996. An investigation of the autolytic properties of three lactococcal strains during cheese ripening. Int Dairy J 6:1149–1165. 10.1016/S0958-6946(96)00024-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chapot-Chartier MP, Deniel C, Rousseau M, Vassal L, Gripon JC. 1994. Autolysis of two strains of Lactococcus lactis during cheese ripening. Int Dairy J 4:251–269. 10.1016/0958-6946(94)90016-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hannon JA, Wilkinson MG, Delahunty CM, Wallace JM, Morrissey PA, Beresford TP. 2003. Use of autolytic starter systems to accelerate the ripening of Cheddar cheese. Int Dairy J 13:313–323. 10.1016/S0958-6946(02)00178-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crow VL, Coolbear T, Holland R, Pritchard GG, Martley FG. 1993. Starters as finishers: starter properties relevant to cheese ripening. Int Dairy J 3:423–460. 10.1016/0958-6946(93)90026-V. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fox PF, Wallace JM, Morgan S, Lynch CM, Niland EJ, Tobin J. 1996. Acceleration of cheese ripening. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 70:271–297. 10.1007/BF00395937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Upadhyay VK, McSweeney PLH. 2003. Acceleration of cheese ripening, p 419–447. In Smit G (ed), Dairy processing: improving quality. Woodhead Publishing Ltd., Sawston, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ganesan B, Stuart MR, Weimer BC. 2007. Carbohydrate starvation causes a metabolically active but nonculturable state in Lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:2498–2512. 10.1128/AEM.01832-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feirtag JM, McKay LL. 1987. Thermoinducible lysis of temperature-sensitive Streptococcus cremoris strains. J Dairy Sci 70:1779–1784. 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(87)80214-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Søndergaard L, Ryssel M, Svendsen C, Høier E, Andersen U, Hammershøj M, Møller JR, Arneborg N, Jespersen L. 2015. Impact of NaCl reduction in Danish semi-hard Samsoe cheeses on proliferation and autolysis of DL-starter cultures. Int J Food Microbiol 213:59–70. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pillidge CJ, Rallabhandi PSVS, Tong XZ, Gopal PK, Farley PC, Sullivan PA. 2002. Autolysis of Lactococcus lactis. Int Dairy J 12:133–140. 10.1016/S0958-6946(01)00135-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buist G, Karsens H, Nauta A, Van Sinderen D, Venema G, Kok J. 1997. Autolysis of Lactococcus lactis caused by induced overproduction of its major autolysin, AcmA. Appl Environ Microbiol 63:2722–2728. 10.1128/aem.63.7.2722-2728.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sandberg TE, Salazar MJ, Weng LL, Palsson BO, Feist AM. 2019. The emergence of adaptive laboratory evolution as an efficient tool for biological discovery and industrial biotechnology. Metab Eng 56:1–16. 10.1016/j.ymben.2019.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bachmann H, Molenaar D, Branco F, Teusink B. 2017. Experimental evolution and the adjustment of metabolic strategies in lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev 24:1–19. 10.1093/femsre/fux024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dragosits M, Mattanovich D. 2013. Adaptive laboratory evolution—principles and applications for biotechnology. Microb Cell Fact 12:64. 10.1186/1475-2859-12-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dorau R, Chen J, Jensen PR, Solem C. 2020. Complete genome sequence of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis bv. diacetylactis SD96. Microb Resour Announc 9:e01140-19. 10.1128/MRA.01140-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dorau R. 2020. Evolutionary and metabolic engineering of Lactococcus lactis for improved food and flavor compound production. Ph.D. thesis. Technical University of Denmark, Kongens Lyngby, Denmark. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cornett JB, Shockman GD. 1978. Cellular lysis of Streptococcus faecalis induced with Triton X-100. J Bacteriol 135:153–160. 10.1128/jb.135.1.153-160.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.López-González MJ, Escobedo S, Rodríguez A, Neves AR, Janzen T, Martínez B. 2018. Adaptive evolution of industrial Lactococcus lactis under cell envelope stress provides phenotypic diversity. Front Microbiol 9:2654. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meyrand M, Boughammoura A, Courtin P, Mézange C, Guillot A, Chapot-Chartier MP. 2007. Peptidoglycan N-acetylglucosamine deacetylation decreases autolysis in Lactococcus lactis. Microbiology (Reading) 153:3275–3285. 10.1099/mic.0.2007/005835-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riepe HR, Pillidge CJ, Gopal PK, Mckay LL. 1997. Characterization of the highly autolytic Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris strains CO and 2250. Appl Environ Microbiol 63:3757–3763. 10.1128/aem.63.10.3757-3763.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spus M, Liu H, Wels M, Abee T, Smid EJ. 2017. Isolation and characterization of Lactobacillus helveticus DSM 20075 variants with improved autolytic capacity. Int J Food Microbiol 241:173–180. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deveau H, Labrie SJ, Chopin MC, Moineau S. 2006. Biodiversity and classification of lactococcal phages. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:4338–4346. 10.1128/AEM.02517-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oliveira J, Mahony J, Hanemaaijer L, Kouwen TRHM, van Sinderen D. 2018. Biodiversity of bacteriophages infecting Lactococcus lactis starter cultures. J Dairy Sci 101:96–105. 10.3168/jds.2017-13403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Den Hengst CD, Van Hijum SAFT, Geurts JMW, Nauta A, Kok J, Kuipers OP. 2005. The Lactococcus lactis CodY regulon: identification of a conserved cis-regulatory element. J Biol Chem 280:34332–34342. 10.1074/jbc.M502349200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen J, Shen J, Ingvar Hellgren L, Ruhdal Jensen P, Solem C. 2015. Adaptation of Lactococcus lactis to high growth temperature leads to a dramatic increase in acidification rate. Sci Rep 5:14199. 10.1038/srep14199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith WM, Pham TH, Lei L, Dou J, Soomro AH, Beatson SA, Dykes GA, Turner MS. 2012. Heat resistance and salt hypersensitivity in Lactococcus lactis due to spontaneous mutation of llmg_1816 (gdpP) induced by high-temperature growth. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:7753–7759. 10.1128/AEM.02316-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dijkstra AR, Starrenburg MJC, Todt T, Van Hijum SAFT, Hugenholtz J, Bron PA. 2018. Transcriptome analysis of a spray drying-resistant subpopulation reveals a zinc-dependent mechanism for robustness in L. lactis SK11. Front Microbiol 9:2418. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weidmann S, Maitre M, Laurent J, Coucheney F, Rieu A, Guzzo J. 2017. Production of the small heat shock protein Lo18 from Oenococcus oeni in Lactococcus lactis improves its stress tolerance. Int J Food Microbiol 247:18–23. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Desmond C, Fitzgerald GF, Stanton C, Ross RP, Al DET, Icrobiol A. 2004. Improved stress tolerance of GroESL-overproducing Lactococcus lactis and probiotic Lactobacillus paracasei NFBC 338. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:5929–5936. 10.1128/AEM.70.10.5929-5936.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dijkstra AR, Setyawati MC, Bayjanov JR, Alkema W, Van Hijum SAFT, Bron PA, Hugenholtz J. 2014. Diversity in robustness of Lactococcus lactis strains during heat stress, oxidative stress, and spray drying stress. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:603–611. 10.1128/AEM.03434-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abdullah-Al-Mahin Sugimoto S, Higashi C, Matsumoto S, Sonomoto K. 2010. Improvement of multiple-stress tolerance and lactic acid production in Lactococcus lactis NZ9000 under conditions of thermal stress by heterologous expression of Escherichia coli dnaK. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:4277–4285. 10.1128/AEM.02878-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ryssel M, Meisner Hviid AM, Dawish MS, Haaber J, Hammer K, Martinussen J, Kilstrup M. 2014. Multi-stress resistance in Lactococcus lactis is actually escape from purine-induced stress sensitivity. Microbiology (Reading) 160:2551–2559. 10.1099/mic.0.082586-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zittle CA, Thompson MP, Custer JH, Cerbulis J. 1962. κ-Casein-β-lactoglobulin interaction in solution when heated. J Dairy Sci 45:807–810. 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(62)89501-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McMahon DJ, Yousif BH, Kaláb M. 1993. Effect of whey protein denaturation on structure of casein micelles and their rennetability after ultra-high temperature processing of milk with or without ultrafiltration. Int Dairy J 3:239–256. 10.1016/0958-6946(93)90067-A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Douglas FW, Greenberg R, Farrell HM, Edmondson LF. 1981. Effects of ultra-high-temperature pasteurization on milk proteins. J Agric Food Chem 29:11–15. 10.1021/jf00103a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stulova I, Kabanova N, Kriščiunaite T, Laht TM, Vilu R. 2011. The effect of milk heat treatment on the growth characteristics of lactic acid bacteria. Agron Res 9:473–478. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Geiger T, Wolz C. 2014. Intersection of the stringent response and the CodY regulon in low GC Gram-positive bacteria. Int J Med Microbiol 304:150–155. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kushwaha GS, Bange G, Bhavesh NS. 2019. Interaction studies on bacterial stringent response protein RelA with uncharged tRNA provide evidence for its prerequisite complex for ribosome binding. Curr Genet 65:1173–1184. 10.1007/s00294-019-00966-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Loveland AB, Bah E, Madireddy R, Zhang Y, Brilot AF, Grigorieff N, Korostelev AA. 2016. Ribosome-RelA structures reveal the mechanism of stringent response activation. Elife 5:e17029. 10.7554/eLife.17029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nugroho ADW, Kleerebezem M, Bachmann H. 2021. Growth, dormancy and lysis: the complex relation of starter culture physiology and cheese flavour formation. Curr Opin Food Sci 39:22–30. 10.1016/j.cofs.2020.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang C, Hernandez-Valdes JA, Kuipers OP, Kok J. 2020. Lysis of a Lactococcus lactis dipeptidase mutant and rescue by mutation in the pleiotropic regulator CodY. Appl Environ Microbiol 86:e02937-19. 10.1128/AEM.02937-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hao P, Liang D, Cao L, Qiao B, Wu H, Caiyin Q, Zhu H, Qiao J. 2017. Promoting acid resistance and nisin yield of Lactococcus lactis F44 by genetically increasing D-Asp amidation level inside cell wall. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 101:6137–6153. 10.1007/s00253-017-8365-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu H, Xue E, Zhi N, Song Q, Tian K, Caiyin Q, Yuan L, Qiao J. 2020. D-methionine and D-phenylalanine improve Lactococcus lactis F44 acid resistance and nisin yield by governing cell wall remodeling. Appl Environ Microbiol 86:e02981-19. 10.1128/AEM.02981-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Emanuele JJ, Jin H, Jacobson BL, Chang CY, Einspahr HM, Villafranca JJ. 1996. Kinetic and crystallographic studies of Escherichia coli UDP-N-acety-muramate:L-alanine ligase. Protein Sci 5:2566–2574. 10.1002/pro.5560051219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Solopova A, Formosa-Dague C, Courtin P, Furlan S, Veiga P, Péchoux C, Armalyte J, Sadauskas M, Kok J, Hols P, Dufrêne YF, Kuipers OP, Chapot-Chartier MP, Kulakauskas S. 2016. Regulation of cell wall plasticity by nucleotide metabolism in Lactococcus lactis. J Biol Chem 291:11323–11336. 10.1074/jbc.M116.714303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.O’Sullivan D, Ross RP, Fitzgerald GF, Coffey A. 2000. Investigation of the relationship between lysogeny and lysis of Lactococcus lactis in cheese using prophage-targeted PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol 66:2192–2198. 10.1128/AEM.66.5.2192-2198.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhou Y, Liang Y, Lynch KH, Dennis JJ, Wishart DS. 2011. PHAST: a fast phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res 39:W347–W352. 10.1093/nar/gkr485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Arndt D, Grant JR, Marcu A, Sajed T, Pon A, Liang Y, Wishart DS. 2016. PHASTER: a better, faster version of the PHAST phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res 44:W16–W21. 10.1093/nar/gkw387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Duwat P, Ehrlich SD, Gruss A. 1999. Effects of metabolic flux on stress response pathways in Lactococcus lactis. Mol Microbiol 31:845–858. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rallu F, Gruss A, Ehrlich SD, Maguin E. 2000. Acid- and multistress-resistant mutants of Lactococcus lactis: identification of intracellular stress signals. Mol Microbiol 35:517–528. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nilsson D, Lauridsen AA, Tomoyasu T, Ogura T. 1994. A Lactococcus lactis gene encodes a membrane protein with putative ATPase activity that is homologous to the essential Escherichia coli ftsH gene product. Microbiology (Reading) 140(Pt 10):2601–2610. 10.1099/00221287-140-10-2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ito K, Akiyama Y. 2005. Cellular functions, mechanism of action, and regulation of Ftsh protease. Annu Rev Microbiol 59:211–231. 10.1146/annurev.micro.59.030804.121316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Narberhaus F, Obrist M, Führer F, Langklotz S. 2009. Degradation of cytoplasmic substrates by FtsH, a membrane-anchored protease with many talents. Res Microbiol 160:652–659. 10.1016/j.resmic.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bove P, Capozzi V, Garofalo C, Rieu A, Spano G, Fiocco D. 2012. Inactivation of the ftsH gene of Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1: effects on growth, stress tolerance, cell surface properties and biofilm formation. Microbiol Res 167:187–193. 10.1016/j.micres.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Roces C, Campelo AB, Escobedo S, Wegmann U, García P, Rodríguez A, Martínez B. 2016. Reduced binding of the endolysin LysTP712 to Lactococcus lactis ΔftsH contributes to phage resistance. Front Microbiol 7:138. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.El Karoui M, Ehrlich D, Gruss A. 1998. Identification of the lactococcal exonuclease/recombinase and its modulation by the putative Chi sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:626–631. 10.1073/pnas.95.2.626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bachmann H, Starrenburg MJC, Molenaar D, Kleerebezem M, Vlieg J. 2012. Microbial domestication signatures of Lactococcus lactis can be reproduced by experimental evolution. Genome Res 22:115–124. 10.1101/gr.121285.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kempler GM, McKay LL. 1980. Improved medium for detection of citrate-fermenting Streptococcus lactis subsp. diacetylactis. Appl Environ Microbiol 39:926–927. 10.1128/aem.39.4.926-927.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Garbowska M, Pluta A, Berthold-Pluta A. 2020. Proteolytic and ACE-inhibitory activities of Dutch-type cheese models prepared with different strains of Lactococcus lactis. Food Biosci 35:100604. 10.1016/j.fbio.2020.100604. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang Y, Zhang Z, Zhang H, Zhao Y, Zhang Z, Xiao J. 2020. PADS Arsenal: a database of prokaryotic defense systems related genes. Nucleic Acids Res 48:D590–D598. 10.1093/nar/gkz916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215:403–410. 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, Buxton S, Cooper A, Markowitz S, Duran C, Thierer T, Ashton B, Meintjes P, Drummond A. 2012. Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28:1647–1649. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. 2012. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9:357–359. 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. 2014. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15:550–521. 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Huerta-Cepas J, Forslund K, Coelho LP, Szklarczyk D, Jensen LJ, Von Mering C, Bork P. 2017. Fast genome-wide functional annotation through orthology assignment by eggNOG-mapper. Mol Biol Evol 34:2115–2122. 10.1093/molbev/msx148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Huerta-Cepas J, Szklarczyk D, Heller D, Hernández-Plaza A, Forslund SK, Cook H, Mende DR, Letunic I, Rattei T, Jensen LJ, Von Mering C, Bork P. 2019. EggNOG 5.0: a hierarchical, functionally and phylogenetically annotated orthology resource based on 5090 organisms and 2502 viruses. Nucleic Acids Res 47:D309–D314. 10.1093/nar/gky1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Sets S1 to S4. Download AEM.01035-21-s0001.xlsx, XLSX file, 0.07 MB (71.8KB, xlsx)

Sections S1 to S3, Tables S1 to S3, Fig. S1 to S6. Download AEM.01035-21-s0002.pdf, PDF file, 0.7 MB (695.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All experimentally generated data are included in this article or its supplemental files. Sequencing data are publicly available, including DNA sequencing results of RD01 (SRR13214404) and RD07 (SRR13214403) and the RNA sequencing data set (BioProject accession number: PRJNA670051).