Abstract

As the single cell field races to characterize each cell type, state, and behavior, the complexity of the computational analysis approaches the complexity of the biological systems. Single cell and imaging technologies now enable unprecedented measurements of state transitions in biological systems, providing high-throughput data that capture tens-of-thousands of measurements on hundreds-of-thousands of samples. Thus, the definition of cell type and state is evolving to encompass the broad range of biological questions now attainable. To answer these questions requires the development of computational tools for integrated multi-omics analysis. Merged with mathematical models, these algorithms will be able to forecast future states of biological systems, going from statistical inferences of phenotypes to time course predictions of the biological systems with dynamic maps analogous to weather systems. Thus, systems biology for forecasting biological system dynamics from multi-omic data represents the future of cell biology empowering a new generation of technology-driven predictive medicine.

Introduction

A technological revolution is transforming biology. Single cell and imaging technologies now enable unprecedented measurements of state transitions in biological systems, providing high-throughput data that capture tens of thousands of measurements on hundreds of thousands of samples. Atlas initiatives are currently characterizing the entire genome [1], transcriptome [2], epigenome [3], of every cell in the human body[2] and model organisms across multiple states including development and disease. Whereas previous atlas projects from bulk technologies aimed to characterize biological systems at baseline, single cell and imaging technologies can now track the multi-scale processes that regulate biological systems over time. Numerous computational tools have been developed to render knowledge from these emerging data streams. As the single cell field races to characterize each cell type, state, and behavior, the complexity of the computational analysis approaches the complexity of the biological systems.

As single cell analysis methods are developing it is apparent that each method can infer distinct biological processes and that these results can vary substantially when applying distinct methods to the same dataset based upon underlying mathematical rationale and assumptions that distinguish the method [4–9]. While distinct, all these results can reflect true biology. This is not a new phenomenta. In 1976, George Box coined the aphorism “All models are wrong, but some models are useful” [10]. As biology becomes evermore dependent on computational dissection of high dimensional data, a critical understanding of the methodologies will be tantamount to expertise in the biological system being investigated. As a notable example, low dimensional feature identification through matrix factorization or manifold learning approaches provide a common analysis approach for single cell datasets [11]. Hierarchy within biological systems has already demonstrated the necessity of considering multiple scales using an ensemble of these unsupervised learning analysis parameters [7,8,12,13]. Just as the definition of a gene has evolved from the single trait simplicity of Mendelian genetics to the complex layers of regulation revealed through Genome Wide Association Studies (GWAS) [14], the definition of cell type and state is evolving to encompass the broad range of biological questions now attainable. The transition from descriptive to predictive biology will require hypothesis specific curation and integration of data and methods.

The multi-resolution nature of biological systems further challenges interpretation of the more complex single-cell multi-omics datasets. Work to develop computational methods that formally integrate data modalities is already underway [15–19]. Many of these approaches rely on inferring correlations between features across molecular scales. However, biological regulation results from intra- and inter-cellular network interactions across temporal scales, which can limit the ability of direct correlative models to uncover the laws of biological systems. In contrast, systems biological approaches use computational models predicated on complex biological phenomena being greater than the sum of their individual parts. Thus, unraveling network dynamics and multiscale data integration are already core features of many mathematical and computational models employed in systems biology methodologies [20–22]. Separately, inference of gene regulation and cellular dynamics are each well developed fields (see [23–26] for reviews). However, integration of these two areas is still in its nascency. Recent advances in methods to use the static output of machine learning on high throughput data to inform mechanistic mathematics models has paved the way for the integration of these two fields [27–30].

Here, we focus on the foundational methodological advances in systems biology for forecasting biological system dynamics from multi-omic data. As much of this work has been done independently for the problems of multimodal single cell analysis and cell-based modeling, we review relevant advances in each of these areas. We also describe work in data integration and multiscale methods for whole cell and/or system level models. Finally, we discuss future opportunities and challenges to uncover regulatory dynamics and combat disease processes through mathematical modeling using current Atlas based initiatives and multi-omic profiling technologies.

Analytical Methods for high throughput single cell molecular profiling

Single cell sequencing (scSeq), and now multi-omic single cell profiling, have enabled the characterization of the molecular states defining cell types and states. This characterization has revealed novel sources of biological variation that have fundamentally challenged previous definitions and dogmas of biological systems [5,6]. As scSeq analysis studies continue their rapid advance, what has become increasingly clear is that no unified method to accurately define cell identity currently exists [5,31]. Instead, combining multiple analytic approaches is often necessary [7,9,12,32]. However, it is unclear whether the challenge of identifying cell types arises from the computational complexity of the data or whether cells exist in a continuum of states and discrete cell type labels are merely an artifact of previous low-throughput assays such as flow cytometry that were used to define cell types for hypothesis driven experimentation. Therefore, resolving cell type from cell state requires additional computational methods to leverage information across space, time, and modular modalities.[33,34]

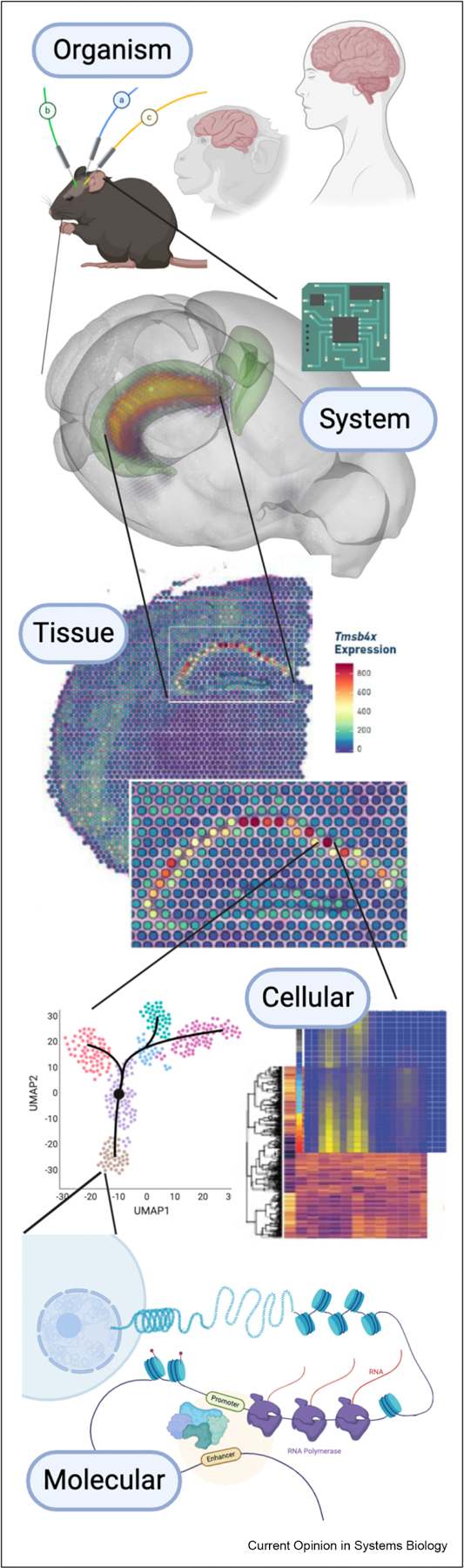

The complexity of cell identity can be understood in the context of the complexity and hierarchy of biological systems (Figure 1). A single gene’s expression requires the recruitment and assembly of the entire transcriptional machinery, the initiation and procession of that machinery, and the release and post-transcriptional editing of its product [35]. This process involves numerous molecules and molecular factors, including transcription factors, cofactors (both coactivators and corepressors), and chromatin regulators [14,36,37]. Modeling the relationships between these factors in regulating cells from distinct tissues and individuals has been one of the primary goals of dimension reduction techniques and gene regulatory network (GRN) analysis (see [11] and [38], respectively). Single cell molecular profiling has revolutionized the precision and scale of the data available for cell-type specific regulatory inference. However, the increased sparsity, biologically meaningful stochasticity [31,37], intracellular variability, and scale of the measurements also introduces challenges for analysis and interpretation.

Figure 1.

The hierarchy of biological systems requires in silico models to be multiscale. For example, drug action at the molecular scale must be linked to clinical outcomes at the tissue, system, and organism scale. Methods to analyse high dimensional data across molecular scales from emerging single-cell multi-omics technologies will be foundational to parameterize mechanistic and computational systems level models, and likewise to inform constraints within machine learning-based multi-omics analysis algorithms themselves. Thus, systems biology is on the precipice of codifying the laws of biological systems into governing equations necessary for multiscale dynamic prediction.

Robust to increased noise of single cell measurements and variable normalization procedures, latent space and dimension reduction methods were some of the first algorithms adopted for single cell analysis (see [39,40] for method comparisons). These methods reduce high dimensional data into lower dimensional latent factors representative of the coregulation of molecular species for a given biological process. Ensemble and consensus based approaches rely on aggregating information across independent methodologies [41–43] or related datasets [7,44,45] (for a comprehensive review, see [46]). The primary advantage of these approaches is the reduction of the number of false-positives [7] [47] While most of these latent space methods are data driven, supervised and semi-surprised algorithms have built on the natural extension of this interpretation to pathway level analysis [11,48]. While matrix factorization methods enable direct association of molecular changes with specific low dimensional features in the data[11], non-linear embeddings can further capture the complex, non-linear regulatory processes hidden in single cell data[49–51]. These techniques often rely on deep learning approaches, and future work on interpretable AI to link the inferred non-linear features to specific biological mechanisms in the data. In all cases, these dimension reduction methods have the inherent advantage of aiding in visualization.

Beyond latent space and dimension reduction methods, GRNs have been developed to infer intra- and inter-cellular interactions that underlie cell fate decisions directly from single cell data. Whereas latent space methods are largely based upon fully unsupervised learning, the GRNs learned from these algorithms have additional predefined mechanisms for these interactions that are built into the assumptions of the model. Networks model molecules as nodes and the relationship between nodes as edges. Edges can be directed, weighted, and/or bipartite. The formulation of the edges provides the hypothesis to be tested in silico. Common relationships encoded as edges include mechanistic interactions, statistical similarities, or other forms of computational inference, including dimension reduction [21,52,53]. Benchmarking efforts have demonstrated that different methods infer networks that vary substantially, reflecting the underlying mathematical rationale and assumptions that distinguish network methods from each other [4,12,53]. Transfer learning techniques exploit the fact that if two datasets share common latent spaces, a feature mapping between the two can identify and characterize relationships often representing specific biological processes between the data defined by individual latent spaces [54–57]Thus, these can enable in silico validation of processes inferred from one dataset in datasets from related biology to distinguish true biological sources of variation from technical noise [54]. Recent GRN algorithms in the single cell literature are also being developed with further constraints based upon prior biological knowledge of ligand, receptor, and transcription factor regulatory networks[58–60]. However, reliance on previously established interactions limits the inference of novel regulatory mechanisms that is the promise of single cell technologies. Thus, a hybrid approach balancing prior knowledge for inference is essential and experimental validation must be the gold standard for assessing model accuracy.

Layering levels of regulation through multi-omics: from epigenetic regulation of transcription through translation to protein

Regulatory networks fundamentally scale multiple molecular dimensions. Before transcription can begin, the DNA must be accessible, a process which is controlled on both a chromatin level by histone modifications, nuclear localization, and chromatin remodeling proteins, and a sequence level via other epigenetic mechanisms such as methylation and enhancer-promoter looping. The basal transcriptional machinery often interacts with the molecular species responsible for these epigenetic modifications leading to both synergistic effects and offsets in timing between the different levels of regulation [17,18]. High throughput single cells epigenetic data is extremely sparse (see [61] for a review of current single cell epigenetic profiling techniques). Thus, many algorithms rely on this close relationship with gene expression to borrow information in addition to making regulatory inferences [62–66]. Further, the many algorithms to integrate epigenetics and expression data currently rely on single cell RNAseq to deconvolute bulk epigenetic profiling [15,67–69] or adopt the transfer learning approach used for in silico validation to establish epigenetic regulation between these data modalities [54,70].

As the technology to perform single cell epigenetic profiling matures [71,72], the ability to profile epigenetic and transcriptional information from the same cell has the potential to elucidate causality via mechanistic models. However, such causal modeling across molecular scales remains an open problem within the field of single cell multi-omics [16,33].

Translation of the mRNA transcript into protein similarly requires the assembly and operation of its own machinery and its own levels of regulation. Thus, it can not be simply assumed that mRNA and protein levels are positively correlated [73–76]. Despite this, many algorithms to integrate these two data types rely on common or correlated information [74,77,78]. Alternatively, mechanistic models of gene expression have been developed that do not use mRNA observations as a proxy for proteins [38,79,80]. These methods have the additional advantage of revealing useful theoretical properties of the biological system in question. For example, in [38] fitting single-cell protein and mRNA data to build a mechanistic gene network model that is inherently stochastic demonstrated that the theoretical distribution was a close approximation to the case of a simple toggle-switch. When dealing with single cell measurements, the treatment of noise and other sources of variability can have profound effects on the results. To address this challenge, [80] used a mechanistic model to show that integrating single cell mRNA and protein can replace dual reporters, enabling the noise decomposition to be obtained from a single gene. Further, they demonstrate mathematically that it is in general impossible to identify the sources of variability, and consequently, the underlying transcription dynamics, from the observed transcript abundance distribution alone, which underlines the need for methods to leverage information across multiple sources [80].

Cell trajectory inference: Pooling information across time

High throughput single cell data captures a “snap-shot” of a cell—a single vector in a space defined by the molecular species being profiled. As the cell is destroyed by the measurement process of current single cell technologies, it is not yet feasible to obtain sufficient long-term longitudinal profiling that is required to parameterize many dynamical systems models of phenotypic decisions. Nonetheless, the inherent variability in cell response to induction results in a wide distribution of states in single cell data obtained at a given sampling time. Thus, algorithms designed to accomplish trajectory inference or a pseudotemporal ordering of cells based on their molecular profiles have generated great interest and insights (see [81] for a comparison of methods).

A popular formation of this problem was first proposed by Waddington, who described the cellular state transitions of differentiation as marbles rolling down an energetic surface, or landscape.[82] The valleys and watersheds of Waddington’s epigenetic landscape represent the trajectories and branch points, respectively. While the molecular effectors of this landscape were unknown at the time, the availability of high throughput molecular data has enabled the theoretical and quantitative characterization of this dynamic process from time course data [83–88] Alternative techniques based on the RNA velocity kinetic model are able to make regulatory inference from single-cell transcriptomic data without requiring perturbation, temporal experiments, or prior biological knowledge [83,89] Taking into account the additional intercellular complexity introduced by the maturation, via splicing, of the mRNA transcript itself, RNA velocity generates a time derivative of the gene expression state from the ratio of spliced to unspiced mRNAs [90,91] Further extension of these techniques in multi-omics analysis utilizing concurrent measurements of protein and mRNA expression at a single cell resolution through techniques such as CITE-seq enables further predictions of future state transitions to complement the temporal history in the transcriptional profiles, moving to predictive modeling.

In spite of the limitations of long-scale temporal profiling, the heterogeneous cell states captured in individual snapshots can still provide dynamics of fate decisions to parameterize systems biology models over short term time scales. Mechanistic models of cell fate transitions are particularly appealing given their concurrent ability to elucidate temporal dynamics and emergent properties of biological systems based upon first principles. Such mechanistic models have been developed using ODEs [22,92,93], regression [94,95], partial information decomposition [96], Markov process, Boolean networks [97], optimal-transport analysis [84], neural networks [85], amongst other. Notably, an entropy-based model studying the differentiation of stem cells has demonstrated that the stochastic dynamics governing the transition between differentiation states to another are marked by a peak in gene expression variability at the point of fate commitment[98]. This provides a foundation for further integration of mechanistic models at the single cell resolution with computational analysis of single cell data to generate movies tracing how changes in molecular states ultimately drive cell fate decisions and predict the impact of molecular perturbations on those states.

Cell-based Mathematical Models

Single cell measurement technologies have led to a biological revolution in no small part because the cell is the basic biological unit of life. A rich field of cell-based mathematical models has also been developed independently of this technological advance (see [25] for a review in the context of cancer biology and [24] for whole cell modeling). Although historically limited by data availability and computational cost, these models successfully abstract representations of key features of cell biology and behavior. For example, Turing models approximate tissues as continuums using reaction-diffusion partial differential equations (PDEs) to describe the spatial dynamics of the system, i.e. movement of nutrients, morphogens, pharmacological agents, and small molecules [99]. Hybrid models are currently the most common cell-based models as they couple continuous environmental factors to discrete cells. Early hybrids coupled ordinary differential equations (ODEs) to represent molecular processes in individual cells with PDEs to represent environmental factors. However, growing computational capabilities and interest in encoding stochasticity has generated an expanding set of multi-class, multiscale methods (see [20] for a review). However, the lack of temporal data introduces challenges in parameterizing these models, limiting their applications to qualitative rather than quantitative predictions of cellular systems.

The recent technological advances to profile the molecular state of single cells provide the opportunity to parameterize and even enable more complex dynamic models of biological systems. Benefiting from computational advances, agent based models (ABMs) are becoming popular as the autonomous agents are an intuitive surrogate for individual cells [20,24,25]. Each autonomous agent has its own rules for interacting with their neighbors and environment. As these rule sets are modular, relevant molecular information for different cell types or states can be substituted depending on the hypothesis in question. Current technologies can profile the genetic, transcriptional, epigenetic, and proteomic data of tens of thousands of cells per sample. Incorporating this data into cell-based models requires the ability to extract the relevant rules, regulatory interaction, and parameter values from this data.

Multiscale methods to unify data integration with mechanistic modeling

Recently, integration of single cell data into a mathematical modeling framework has been successfully employed in the field of differentiation by quantifying the changing proportion of cells in distinct cell states over time [27] Building off of this infrastructure by integrating single cell clonally-resolved transcriptome datasets with longitudinal treatment response data into a mechanistic mathematical model of drug resistance dynamics, [28] was able to show that the explicit inclusion of the transcriptomic information in the parameter estimation is critical for identification of the model parameters and enables accurate prediction of new treatment regimens. However, as these methods are constructed and tested, it will be important to remember that most existing metrics to assess algorithm performance do not take into account the correctness of higher-order network structure [12].

While each high-throughput measurement technology can resolve specific biological scales, complementary data integration techniques can reveal multi-scale interactions between modalities. Work is already underway to define multi-cellular programs as the combinations of different cellular programs in different cell types that are coordinated together in the tissue, thus forming a higher-order functional unit at the tissue-level, rather than only at the cell-level [100] For example, techniques to incorporate newly developed spatial transcriptomic data are able to capture both the autonomous behavior of single cells and the interactions of a cell with its neighbors simultaneously [101]. The entire field of metabolomics has emerged as a result of the integration of hierarchical analysis to study this regulation at the metabolic, gene-expression, and signaling levels [102,103]. Methods to analyse this high dimensional data across molecular scales from emerging single-cell multi-omics technologies will be foundational to parameterize these mechanistic models, and likewise to inform mechanistic constraints within machine learning-based multi-omics analysis algorithms themselves.

Codifying the laws of biological systems into governing equations is essential to accurately modeling the regulatory relations across molecular and cellular scales [104]. Finding these laws is now a tantalizing possibility for basic scientists as single-cell profiling technologies continue to advance spurring the formation of tremendous new data resources and atlas-based initiatives. Computational techniques and benchmarking strategies to integrate these datasets are emerging as an active areas of research [54,78,105]. When integrated with mathematical models, they also have the opportunity to forecast future states of biological systems, going from statistical predictions of phenotypes to time course predictions of the biological systems with dynamic maps that are analogous to weather forecasts systems. These predictive systems will have broad sweeping applications ranging from basic science to precision medicine. However, accuracy from a clinical perspective requires in silico models to be multiscale [106,107]. For example, drug action at the molecular scale must be linked to clinical outcomes at the tissue or organism scale [108]. Thus, systems biology for forecasting biological system dynamics from multi-omic data represents the future of cell biology. Through further advances to mechanistic modeling of high-throughput data and expanded time-course multi-omics profiling technologie, its application will ultimately empower a new generation of technology-driven predictive medicine

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers U01CA212007, U01CA253403]; the Emerson Foundation [grant number 640183]; the Lustgarten Foundation, the Kavli NDS Distinguished Postdoctoral Fellowship, and the Johns Hopkins Provost Postdoctoral Fellowship.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: E.J. Fertig serves on the Scientific Advisory Board of Viosera Therapeutics

References

- 1.Kim-Hellmuth S, Aguet F, Oliva M, Muñoz-Aguirre M, Kasela S, Wucher V, Castel SE, Hamel AR, Viñuela A, Roberts AL, et al. : Cell type-specific genetic regulation of gene expression across human tissues. Science 2020, 369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Stubbington MJT, Regev A, Teichmann SA: The Human Cell Atlas: from vision to reality. Nature 2017, 550:451–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium, Kundaje A, Meuleman W, Ernst J, Bilenky M, Yen A, Heravi-Moussavi A, Kheradpour P, Zhang Z, Wang J, et al. : Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature 2015, 518:317–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen S, Mar JC: Evaluating methods of inferring gene regulatory networks highlights their lack of performance for single cell gene expression data. BMC Bioinformatics 2018, 19:232. The authors evaluate the performance of GRN for single cell data and find that different methods infer networks that vary substantially reflects the underlying mathematical rationale and assumptions that distinguish network methods from each other.

- 5.Morris SA: The evolving concept of cell identity in the single cell era. Development 2019, 146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clevers H, Rafelski S, Elowitz M, Klein A, Shendure J, Trapnell C, Lein E, Lundberg E, Uhlen M, Martinez-Arias A, et al. : What Is Your Conceptual Definition of “ Cell Type” in the Context of a Mature Organism? Cell Systems 2017, 4:255–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stumpf MPH: Multi-model and network inference based on ensemble estimates: avoiding the madness of crowds. J R Soc Interface 2020, 17:20200419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Way GP, Zietz M, Rubinetti V, Himmelstein DS, Greene CS: Sequential compression of gene expression across dimensionalities and methods reveals no single best method or dimensionality. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory 2019.

- 9.Babtie AC, Chan TE, Stumpf MPH: Learning regulatory models for cell development from single cell transcriptomic data. Current Opinion in Systems Biology 2017, 5:72–81. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Box GEP, Draper NR: Empirical model-building and response surfaces. Wiley series in probability and mathematical statistics 1987, 669. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stein-O’Brien GL, Arora R, Culhane AC, Favorov AV, Garmire LX, Greene CS, Goff LA, Li Y, Ngom A, Ochs MF, et al. : Enter the Matrix: Factorization Uncovers Knowledge from Omics. Trends Genet 2018, 34:790–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Oates CJ, Amos R, Spencer SEF: Quantifying the multi-scale performance of network inference algorithms. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol 2014, 13:611–631. A review of metrics for assessing GRN performance. The authors demonstrate that existing metrics to assess algorithm performance do not take into account the correctness of higher-order network structure and that performance of a network inference algorithm depends crucially on the scale at which inferences are to be made; in particular strong local performance does not guarantee accurate reconstruction of higher-order topology. They go on to propose a metric to combat this.

- 13.Way GP, Zietz M, Rubinetti V, Himmelstein DS, Greene CS: Compressing gene expression data using multiple latent space dimensionalities learns complementary biological representations. Genome Biol 2020, 21:109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Boyle EA, Li YI, Pritchard JK: An Expanded View of Complex Traits: From Polygenic to Omnigenic. Cell 2017, 169:1177–1186. Complex traits are the result of extremely large numbers of variants of small effects. The authors suggest that this could potentially implicate regulatory variants active in disease-relevant tissue. The ‘omnigenic’ model proposed by Boyle et al, indicates potential implications for “next generation mapping studies”, particularly in the area of large-scale genotyping for personalized risk prediction and modeling the flow of regulatory information through cellular networks.

- 15.Argelaguet R, Velten B, Arnol D, Dietrich S, Zenz T, Marioni JC, Huber W, Buettner F, Stegle O: Multi-Omics factor analysis - a framework for unsupervised integration of multi-omic data sets. bioRxiv 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Stuart T, Satija R: Integrative single-cell analysis. Nat Rev Genet 2019, 20:257–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stein-O’Brien G, Kagohara LT, Li S, Thakar M, Ranaweera R, Ozawa H, Cheng H, Considine M, Schmitz S, Favorov AV, et al. : Integrated time course omics analysis distinguishes immediate therapeutic response from acquired resistance. Genome Med 2018, 10:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kagohara LT, Stein-O’Brien GL, Kelley D, Flam E, Wick HC, Danilova LV, Easwaran H, Favorov AV, Qian J, Gaykalova DA, et al. : Epigenetic regulation of gene expression in cancer: techniques, resources and analysis. Brief Funct Genomics 2017, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Method of the Year 2019: Single-cell multimodal omics. Nat Methods 2020, 17:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu JS, Bagheri N: Multi-class and multi-scale models of complex biological phenomena. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2016, 39:167–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oates CJ, Mukherjee S: Network Inference and Biological Dynamics. Ann Appl Stat 2012, 6:1209–1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ocone A, Haghverdi L, Mueller NS, Theis FJ: Reconstructing gene regulatory dynamics from high-dimensional single-cell snapshot data. Bioinformatics 2015, 31:i89–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Babtie AC, Stumpf MPH, Thorne T: Gene regulatory network inference. In Reference Module in Biomedical Sciences Edited by Voit E Elsevier; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Babtie AC, Stumpf MPH: How to deal with parameters for whole-cell modelling. J R Soc Interface 2017, 14. A review demonstrating the complexity of whole-cell modelling over simpler submodels particularly in the selection and estimation of parameters. Bayesian statistical frameworks offer advantages over the traditional likelihood approach but it can prove computationally prohibitive. Studies generally lack comprehensive in vivo measurements needed to automate obtaining relevant parameter estimates. Currently it is impractical to use inference techniques on WCMs however these are useful to parameterize component submodels, in order to account for cellular and system context. Parameter uncertainty may best be mitigated with sensitivity analysis, particularly for models with large numbers of parameters. Over reliance on combined, well parameterized submodels introduces significant problems in respect to correlation. WCM’s rely too heavily on simplification of processes and are as a result biased to our current understanding. The lack of a detailed study of dynamical determinants undermines the value represented by WCMs.

- 25.Metzcar J, Wang Y, Heiland R, Macklin P: A Review of Cell-Based Computational Modeling in Cancer Biology. JCO Clin Cancer Inform 2019, 3:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Jong H: Modeling and simulation of genetic regulatory systems: a literature review. J Comput Biol 2002, 9:67–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stumpf PS, Smith RCG, Lenz M, Schuppert A, Müller F-J, Babtie A, Chan TE, Stumpf MPH, Please CP, Howison SD, et al. : Stem Cell Differentiation as a Non-Markov Stochastic Process. Cell Syst 2017, 5:268–282.e7. One of the first integrations of single cell data into a mechanistic mathematical modeling framework. Quantifies the changing proportion of cells in distinct cell states over time during differentiation.

- 28. Johnson KE, Howard GR, Morgan D, Brenner E: Integrating multimodal data sets into a mathematical framework to describe and predict therapeutic resistance in cancer. bioRxiv 2020. The authors suggest an experimental-computational framework for using multimodal data sets when selecting parameters in a mechanistic model of drug resistance dynamics in the response to treatment in cancer. Johnson et al, show that their model is capable of accurately predicting treatment response dynamics. To achieve this they developed a machine learning classifier which estimates the class identity of an individual cell-basedcell based on its transcriptome. The authors propose that this framework might well be applicable not just in experimental settings but may also be applied to highly targeted therapies.

- 29.Yuan B, Shen C, Luna A, Korkut A, Marks DS, Ingraham J, Sander C: CellBox: Interpretable Machine Learning for Perturbation Biology with Application to the Design of Cancer Combination Therapy. Cell Syst 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30. Kim JK, Marioni JC: Inferring the kinetics of stochastic gene expression from single-cell RNA-sequencing data. Genome Biol 2013, 14:R7. Authors develop a statistical framework motivated by a kinetic model for transcriptional bursting to model the biological variability present in single-cell RNA-seq data and find evidence that histone modifications affect transcriptional bursting by modulating both burst size and frequency.

- 31.Symmons O, Raj A: What’s Luck Got to Do with It: Single Cells, Multiple Fates, and Biological Nondeterminism. Molecular Cell 2016, 62:788–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castro DM, de Veaux NR, Miraldi ER, Bonneau R: Multi-study inference of regulatory networks for more accurate models of gene regulation. PLoS Comput Biol 2019, 15:e1006591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lähnemann D, Köster J, Szczurek E, McCarthy DJ, Hicks SC, Robinson MD, Vallejos CA, Campbell KR, Beerenwinkel N, Mahfouz A, et al. : Eleven grand challenges in single-cell data science. Genome Biol 2020, 21:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cahan P, Cacchiarelli D, Dunn S-J, Hemberg M, de Sousa Lopes SMC, Morris SA, Rackham OJL, Del Sol A, Wells CA: Computational Stem Cell Biology: Open Questions and Guiding Principles. Cell Stem Cell 2021, 28:20–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manning KS, Cooper TA: The roles of RNA processing in translating genotype to phenotype. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2017, 18:102–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Viñuelas J, Kaneko G, Coulon A, Vallin E, Morin V, Mejia-Pous C, Kupiec J-J, Beslon G, Gandrillon O: Quantifying the contribution of chromatin dynamics to stochastic gene expression reveals long, locus-dependent periods between transcriptional bursts. BMC Biol 2013, 11:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coulon A, Gandrillon O, Beslon G: On the spontaneous stochastic dynamics of a single gene: complexity of the molecular interplay at the promoter. BMC Syst Biol 2010, 4:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Herbach U, Bonnaffoux A, Espinasse T, Gandrillon O: Inferring gene regulatory networks from single-cell data: a mechanistic approach. BMC Syst Biol 2017, 11:105. The authors fit single-cell protein and mRNA data to build a mechanistic gene network model that is inherently stochastic and turns out to be extremely close to the theoretical distribution in the case of a simple toggle-switch.

- 39.Palla G, Ferrero E: Latent Factor Modeling of scRNA-Seq Data Uncovers Dysregulated Pathways in Autoimmune Disease Patients. iScience 2020, 23:101451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun S, Zhu J, Ma Y, Zhou X: Accuracy, robustness and scalability of dimensionality reduction methods for single-cell RNA-seq analysis. Genome Biol 2019, 20:269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marbach D, Costello JC, Küffner R, Vega NM, Prill RJ, Camacho DM, Allison KR, DREAM5 Consortium, Kellis M, Collins JJ, et al. : Wisdom of crowds for robust gene network inference. Nat Methods 2012, 9:796–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meyer P, Cokelaer T, Chandran D, Kim KH, Loh P-R, Tucker G, Lipson M, Berger B, Kreutz C, Raue A, et al. : Network topology and parameter estimation: from experimental design methods to gene regulatory network kinetics using a community based approach. BMC Syst Biol 2014, 8:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vittadello ST, Stumpf MPH: Model comparison via simplicial complexes and persistent homology. arXiv [mathAT] 2020, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Stein-O’Brien GL, Carey JL, Lee WS, Considine M, Favorov AV, Flam E, Guo T, Li S, Marchionni L, Sherman T, et al. : PatternMarkers & GWCoGAPS for novel data-driven biomarkers via whole transcriptome NMF. Bioinformatics 2017, 33:1892–1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Waardenberg AJ, Field MA: consensusDE: an R package for assessing consensus of multiple RNA-seq algorithms with RUV correction. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Kuncheva LI: Combining Pattern Classifiers: Methods and Algorithms John Wiley & Sons; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mohammadi S, Davila-Velderrain J, Kellis M: A multiresolution framework to characterize single-cell state landscapes. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mao W, Zaslavsky E, Hartmann BM, Sealfon SC, Chikina M: Pathway-level information extractor (PLIER) for gene expression data. Nat Methods 2019, 16:607–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McInnes L, Healy J: UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction. arXiv [statML] 2018,

- 50.Moon KR, van Dijk D, Wang Z, Chen W, Hirn MJ, Coifman RR, Ivanova NB, Wolf G, Krishnaswamy S: PHATE: A Dimensionality Reduction Method for Visualizing Trajectory Structures in High-Dimensional Biological Data. bioRxiv 2017.

- 51.van der Maaten LJP and Hinton GE Visualizing High-Dimensional Data Using t-SNE. Journal of Machine Learning Research 9(November):2579–2605, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jin S, Zhang L, Nie Q: scAI: an unsupervised approach for the integrative analysis of parallel single-cell transcriptomic and epigenomic profiles. Genome Biol 2020, 21:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parikshak NN, Gandal MJ, Geschwind DH: Systems biology and gene networks in neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders. Nat Rev Genet 2015, 16:441–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stein-O’Brien GL, Clark BS, Sherman T, Zibetti C, Hu Q, Sealfon R, Liu S, Qian J, Colantuoni C, Blackshaw S, et al. : Decomposing Cell Identity for Transfer Learning across Cellular Measurements, Platforms, Tissues, and Species. Cell Syst 2019, 8:395–411.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sharma G, Colantuoni C, Goff LA, Fertig EJ, Stein-O’Brien G: projectR: An R/Bioconductor package for transfer learning via PCA, NMF, correlation, and clustering. Bioinformatics 2019, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Lotfollahi M, Naghipourfar M, Theis FJ, Wolf FA: Conditional out-of-distribution generation for unpaired data using transfer VAE. Bioinformatics 2020, 36:i610–i617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pan SJ, Kwok JT, Yang Q: Transfer learning via dimensionality reduction AAAI; 2008, [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cherry C, Maestas DR, Han J, Andorko JI, Cahan P, Fertig EJ, Garmire LX, Elisseeff JH: Intercellular signaling dynamics from a single cell atlas of the biomaterials response. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory 2020.

- 59.Efremova M, Vento-Tormo M, Teichmann SA, Vento-Tormo R: CellPhoneDB: inferring cell-cell communication from combined expression of multi-subunit ligand-receptor complexes. Nat Protoc 2020, 15:1484–1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Browaeys R, Saelens W, Saeys Y: NicheNet: modeling intercellular communication by linking ligands to target genes. Nat Methods 2020, 17:159–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lo P-K, Zhou Q: Emerging techniques in single-cell epigenomics and their applications to cancer research. J Clin Genom 2018, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Wang A, Chiou J, Poirion OB, Buchanan J, Valdez MJ, Verheyden JM, Hou X, Kudtarkar P, Narendra S, Newsome JM, et al. : Single-cell multiomic profiling of human lungs reveals cell-type-specific and age-dynamic control of SARS-CoV2 host genes. Elife 2020, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu J, Gao C, Sodicoff J, Kozareva V, Macosko EZ, Welch JD: Jointly defining cell types from multiple single-cell datasets using LIGER. Nat Protoc 2020, 15:3632–3662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Welch J, Kozareva V, Ferreira A, Vanderburg C, Martin C, Macosko E: Integrative inference of brain cell similarities and differences from single-cell genomics. bioRxiv 2018.

- 65.Argelaguet R, Arnol D, Bredikhin D, Deloro Y, Velten B, Marioni JC, Stegle O: MOFA+: a probabilistic framework for comprehensive integration of structured single-cell data. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Gu C, Liu S, Wu Q, Zhang L, Guo F: Integrative single-cell analysis of transcriptome, DNA methylome and chromatin accessibility in mouse oocytes. Cell Res 2019, 29:110–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ardakani FB, Kattler K, Nordström K, Gasparoni N, Gasparoni G, Fuchs S, Sinha A, Barann M, Ebert P, Fischer J, et al. : Integrative analysis of single-cell expression data reveals distinct regulatory states in bidirectional promoters. Epigenetics & Chromatin 2018, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Welch JD, Hartemink AJ, Prins JF: MATCHER: manifold alignment reveals correspondence between single cell transcriptome and epigenome dynamics. Genome Biology 2017, 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Duren Z, Chen X, Zamanighomi M, Zeng W, Satpathy AT, Chang HY, Wang Y, Wong WH: Integrative analysis of single-cell genomics data by coupled nonnegative matrix factorizations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115:7723–7728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Erbe R, Kessler MD, Favorov AV, Easwaran H, Gaykalova DA, Fertig EJ: Matrix factorization and transfer learning uncover regulatory biology across multiple single-cell ATAC-seq data sets. Nucleic Acids Res 2020, 48:e68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cheow LF, Courtois ET, Tan Y, Viswanathan R, Xing Q, Tan RZ, Tan DSW, Robson P, Loh Y-H, Quake SR, et al. : Single-cell multimodal profiling reveals cellular epigenetic heterogeneity. Nat Methods 2016, 13:833–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Angermueller C, Clark SJ, Lee HJ, Macaulay IC, Teng MJ, Hu TX, Krueger F, Smallwood S, Ponting CP, Voet T, et al. : Parallel single-cell sequencing links transcriptional and epigenetic heterogeneity. Nat Methods 2016, 13:229–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Taniguchi Y, Choi PJ, Li G-W, Chen H, Babu M, Hearn J, Emili A, Xie XS: Quantifying E. coli proteome and transcriptome with single-molecule sensitivity in single cells. Science 2010, 329:533–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hao Y, Hao S, Andersen-Nissen E, Mauck WM, Zheng S, Butler A, Lee MJ, Wilk AJ, Darby C, Zagar M, et al. : Integrated analysis of multimodal single-cell data. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75.Edfors F, Danielsson F, Hallström BM, Käll L, Lundberg E, Pontén F, Forsström B, Uhlén M: Gene-specific correlation of RNA and protein levels in human cells and tissues. Mol Syst Biol 2016, 12:883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Magnusson R, Rundquist O, Kim MJ, Hellberg S, Na CH, Benson M, Gomez-Cabrero D, Kockum I, Tegnér J, Piehl F, et al. : A validated strategy to infer protein biomarkers from RNA-Seq by combining multiple mRNA splice variants and time-delay. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory 2020.

- 77.Singh A, Shannon CP, Gautier B, Rohart F, Vacher M, Tebbutt SJ, Lê Cao K-A: DIABLO: an integrative approach for identifying key molecular drivers from multi-omics assays. Bioinformatics 2019, 35:3055–3062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stuart T, Butler A, Hoffman P, Hafemeister C, Papalexi E, Mauck WM 3rd, Hao Y, Stoeckius M, Smibert P, Satija R: Comprehensive Integration of Single-Cell Data. Cell 2019, 177:1888–1902.e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bonnaffoux A, Herbach U, Richard A, Guillemin A, Gonin-Giraud S, Gros P-A, Gandrillon O: WASABI: a dynamic iterative framework for gene regulatory network inference. BMC Bioinformatics 2019, 20:220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Ham L, Jackson M, Stumpf MPH: Pathway dynamics can delineate the sources of transcriptional noise in gene expression. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory 2020. The authors demonstrate mathematically that it is in general impossible to identify the sources of variability, and consequently, the underlying transcription dynamics, from the observed transcript abundance distribution alone. They show that measurements taken from the same biochemical pathway (e.g. mRNA and protein) can replace dual reporters, enabling the noise decomposition to be obtained from a single gene. This completely circumvents the requirement of strictly independent and identically regulated reporter genes.

- 81. Saelens W, Cannoodt R, Todorov H, Saeys Y: A comparison of single-cell trajectory inference methods. Nat Biotechnol 2019, 37:547–554. A very throughout comparison of trajectory methods. The authors make acute observations and recommendations including that new methods should focus on improving the unbiased inference of tree, cyclic graph and disconnected topologies. They find that methods repeatedly overestimate or underestimate the complexity of the underlying topology, even if the trajectory could easily be identified using a dimensionality reduction method and that most TI algorithms have difficulty inferring even simple graphs which may include cycles or disconnected subgraphs.

- 82.Waddington CH: The Strategy of the Genes. Allen 1957,

- 83. Soto LM, Bernal-Tamayo JP, Lehmann R, Balsamy S: scMomentum: Inference of Cell-Type-Specific Regulatory Networks and Energy Landscapes. bioRxiv 2020. The authors explore the assumption that regulatory signals are specific and similar among cells belonging to the same cell type, as they would be with a quasistable attractor. They do this by using a linear approximation while still accounting for a non-zero velocity in the quasi-stable state.

- 84. Schiebinger G, Shu J, Tabaka M, Cleary B, Subramanian V, Solomon A, Gould J, Liu S, Lin S, Berube P, et al. : Optimal-Transport Analysis of Single-Cell Gene Expression Identifies Developmental Trajectories in Reprogramming. Cell 2019, 176:1517. The authors describe a novel approach to studying development time courses to infer ancestor-descendant fates. Current approaches, with few exceptions, do not take into account temporal information, most focus on stationary processes and rely strongly on graph theory which constrain the models. By implementing the mathematical approach of Optimal Transport the authors use scRNA-seq data across time to infer how probability distributions of origins and fates evolve.

- 85.Guo J, Zheng J: HopLand: single-cell pseudotime recovery using continuous Hopfield network-based modeling of Waddington’s epigenetic landscape. Bioinformatics 2017, 33:i102–i109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Moris N, Pina C, Arias AM: Transition states and cell fate decisions in epigenetic landscapes. Nat Rev Genet 2016, 17:693–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gao NP, Gandrillon O, Páldi A, Herbach U, Gunawan R: Universality of cell differentiation trajectories revealed by a reconstruction of transcriptional uncertainty landscapes from single-cell transcriptomic data. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory 2020.

- 88.Trapnell C: Defining cell types and states with single-cell genomics. Genome Res 2015, 25:1491–1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Lange M, Bergen V, Klein M, Setty M, Reuter B, Bakhti M, Lickert H, Ansari M, Schniering J, Schiller HB, et al. : CellRank for directed single-cell fate mapping. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory 2020. CellRank is a highly efficient and robust software package that allows for the estimation of directed trajectories of cells in development and regeneration. In as much as is a method to quantitatively analyze RNA velocity induced vector fields, it does not ignore the stochastic nature of cellular fate decisions and velocity uncertainty and it focuses on trajectory reconstruction. It is “simulation free, independent of any low-dimensional embedding, takes into account velocity uncertainty and is able to identify individual initial and terminal states.”

- 90.La Manno G, Soldatov R, Zeisel A, Braun E, Hochgerner H, Petukhov V, Lidschreiber K, Kastriti ME, Lönnerberg P, Furlan A, et al. : RNA velocity of single cells. Nature 2018, 560:494–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bergen V, Lange M, Peidli S, Wolf FA, Theis FJ: Generalizing RNA velocity to transient cell states through dynamical modeling. Nat Biotechnol 2020, 38:1408–1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zheng X, Huang Y, Zou X: scPADGRN: A preconditioned ADMM approach for reconstructing dynamic gene regulatory network using single-cell RNA sequencing data. PLoS Comput Biol 2020, 16:e1007471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Matsumoto H, Kiryu H, Furusawa C, Ko MSH, Ko SBH, Gouda N, Hayashi T, Nikaido I: SCODE: an efficient regulatory network inference algorithm from single-cell RNA-Seq during differentiation. Bioinformatics 2017, 33:2314–2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Peng J, Chembazhi UV, Bangru S, Traniello IM, Kalsotra A, Ochoa I, Hernaez M: SimiC: A Single Cell Gene Regulatory Network Inference method with Similarity Constraints. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory 2020.

- 95.Sanchez-Castillo M, Blanco D, Tienda-Luna IM, Carrion MC, Huang Y: A Bayesian framework for the inference of gene regulatory networks from time and pseudo-time series data. Bioinformatics 2018, 34:964–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chan TE, Stumpf MPH, Babtie AC: Gene Regulatory Network Inference from Single-Cell Data Using Multivariate Information Measures. Cell Syst 2017, 5:251–267.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Moignard V, Woodhouse S, Haghverdi L, Lilly AJ, Tanaka Y, Wilkinson AC, Buettner F, Macaulay IC, Jawaid W, Diamanti E, et al. : Decoding the regulatory network of early blood development from single-cell gene expression measurements. Nat Biotechnol 2015, 33:269–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Richard A, Boullu L, Herbach U, Bonnafoux A, Morin V, Vallin E, Guillemin A, Gao NP, Gunawan R, Cosette J, et al. : Single-Cell-Based Analysis Highlights a Surge in Cell-to-Cell Molecular Variability Preceding Irreversible Commitment in a Differentiation Process. PLOS Biology 2016, 14:e1002585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Turing AM: The chemical basis of morphogenesis. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 1952, 237:37–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Jerby-Arnon L, Regev A: Mapping multicellular programs from single-cell profiles [date unknown]. The authors define multi-cellular programs as the combinations of different cellular programs in different cell types that are coordinated together in the tissue, thus forming a higher-order functional unit at the tissue-level, rather than only at the cell-level.

- 101.Verma A, Jena SG, Isakov DR, Aoki K, Toettcher JE, Engelhardt BE: A self-exciting point process to study multi-cellular spatial signaling patterns. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 102.He F, Stumpf MPH: Quantifying Dynamic Regulation in Metabolic Pathways with Nonparametric Flux Inference. Biophys J 2019, 116:2035–2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Chowdhury A, Maranas CD: Personalized Kinetic Models for Predictive Healthcare. Cell Syst 2015, 1:250–251. The authors suggest that advances are required for genome-scale models because existing models fail to establish a relationship between a causative agent and an observed shift in metabolism, also constraint based modeling overlooks the dynamic substrate-level mass action and regulation. They note that personalized drug targets and potential off-target effects have been facilitated. Ideally they postulate the need for a single kinetic model capable of predicting individual phenotypes over multiple perturbations and/or drug exposures.

- 104. Walpole J, Papin JA, Peirce SM: Multiscale computational models of complex biological systems. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 2013, 15:137–154. No single comprehensive gene-to-organism multiscale model has been developed and remains a goal of this field of research given the extent of utility derived from existing multiscale models to examine complex biological systems. These models principally enhance traditional experimental findings by allowing for hypothesis generation and testing otherwise impossible. This allows translation of observations and deductions into in-vivo systems.

- 105.Angel PW, Rajab N, Deng Y, Pacheco CM, Chen T, Lê Cao K-A, Choi J, Wells CA: A simple, scalable approach to building a cross-platform transcriptome atlas. PLoS Comput Biol 2020, 16:e1008219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Szeto GL, Finley SD: Integrative Approaches to Cancer Immunotherapy. Trends Cancer Res 2019, 5:400–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Chen R, Mias GI, Li-Pook-Than J, Jiang L, Lam HYK, Chen R, Miriami E, Karczewski KJ, Hariharan M, Dewey FE, et al. : Personal omics profiling reveals dynamic molecular and medical phenotypes. Cell 2012, 148:1293–1307. Chen, Mias et al describe what they claim to be the first extensive integrative personal omics profile (iPOP) of an individual through healthy and diseased states. This provided the ability to identify disease risk and represented a proof-of-principle of personalized medicine which enhances health monitoring, diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of diseased states.

- 108.Clarke R, Tyson JJ, Tan M, Baumann WT, Jin L, Xuan J, Wang Y: Systems biology: perspectives on multiscale modeling in research on endocrine-related cancers. Endocr Relat Cancer 2019, 26:R345–R368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]