Abstract

Autophagy is a catabolic process that maintains internal homeostasis and energy balance through the lysosomal degradation of redundant or damaged cellular components. During virus infection, autophagy is triggered both in parenchymal and in immune cells with different finalistic objectives: in parenchymal cells, the goal is to destroy the virion particle while in macrophages and dendritic cells the goal is to expose virion-derived fragments for priming the lymphocytes and initiate the immune response. However, some viruses have developed a strategy to subvert the autophagy machinery to escape the destructive destiny and instead exploit it for virion assembly and exocytosis. Coronaviruses (like SARS-CoV-2) possess such ability. The autophagy process requires a set of proteins that constitute the core machinery and is controlled by several signaling pathways. Here, we report on natural products capable of interfering with SARS-CoV-2 cellular infection and replication through their action on autophagy. The present study provides support to the use of such natural products as adjuvant therapeutics for the management of COVID-19 pandemic to prevent the virus infection and replication, and so mitigating the progression of the disease.

Keywords: COVID-19, Virophagy, Coronavirus, Chloroquine, Pandemic, Phytotherapy, Resveratrol

Graphical abstract

Abbreviations

- ATG

autophagy-related

- BBR

berberine;

- CLPRO

chymotrypsin-like protease

- COVID-19

Corona Virus Disease 2019

- CoV

coronavirus

- DMV

double-membrane vesicle

- E

envelope

- EGCG

epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate

- EV71

enterovirus-71

- hACE2

human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2

- hCoV-229E

human coronavirus 229E

- IAV

influenza A virus

- IBV

infectious bronchitis virus

- M

membrane

- MAP-LC3

microtubule-associated protein-light chain 3

- MERS-CoV

middle east respiratory syndrome

- MHV

mouse hepatitis virus

- N

nucleocapsid

- nsps

non-structural proteins

- ORF

open reading frames

- PGG

1,2,3,4,6-penta-O-galloyl-β-d-glucose

- PL1PRO and PL2PRO

papain-like proteinases

- pp

polyproteins

- Q7G

quercetin-7-0-glucoside

- RABV

rabies virus

- RBD

receptor binding domain

- RdRp

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RTC

replication-transcription complex

- RV

resveratrol

- S

spike

- SARS

severe acute respiratory syndrome

- SARS-CoV

severe acute respiratory syndrome-CoV

- Ss

saikosaponin

- TF3

theaflavin 3,3'di-gallate

- TLR

Toll like receptor

- TMPRSS-2

transmembrane protease serine protease 2

- UTR

untranslated region

1. Introduction

In December 2019, rose in Wuhan (Hubei Province, China) what would soon become one of the most contagious viral pandemics in recent human history.1 The disease was named Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), after the family name of the causative virus SARS-CoV-2. The worse clinical complication of COVID-19 is dominated by a respiratory distress syndrome (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, SARS), which may cause death if untreated. As of 29 July 2021, there are 197 million confirmed cases of COVID-19, and more than 4 million confirmed deaths worldwide (WHO report at https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports). Although vaccination constitutes an important and useful means for preventing the spread of the disease, it remains urgent to identify effective strategies to treat at the earliest stages those who get infected. A variety of protocols for treating COVID-19 patients have been proposed, which include antiviral drugs, monoclonal antibodies, antibiotics, and anti-inflammatory drugs in combination and sequential administration depending on the disease stage and the clinical condition of the patient. Natural products provide a source of bioactive molecules that can be exploited for novel and effective treatments to prevent the fatal evolution of this disease.2, 3, 4, 5, 6 These natural biomolecules could interfere at any stage of the virus life cycle, from entering the cell to its replication, assembly, and exit from the cell, as well as by triggering virus clearance.3,7, 8, 9, 10 Autophagy, a vesicular-driven degradation pathway of cellular components, is triggered as a cellular stress response to viral infection, and it is involved in all steps of CoV replication and propagation.11,12

In this review, we will focus on those natural products that have been shown effective in preventing and limiting the infection and replication of CoV through the modulation of the autophagy process. First, we will introduce the principal cellular and molecular features of the autophagy process, then we will discuss how SARS-CoV-2 viral replication interacts with the autophagy-lysosomal vesicular traffic, and finally, we will present and discuss the mechanisms of action of the natural products that potentially interfere with these processes.

2. Autophagy at glance

Autophagy (herein referring to macroautophagy) is a catabolic process that maintains cell homeostasis and preserves cell viability under pathological stresses, including viral infections.11,13 The two other known autophagy pathways, namely microautophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy, play a little if any role in virus infections. Here, we will provide a glance at the autophagy machinery, as a comprehensive description of this process can be found elsewhere.14,15

Autophagy starts with the formation of a double-membrane vesicle, named the autophagosome that sequesters the substrates to be delivered to the lysosome for full degradation. The core machinery includes more than 30 autophagy-related (ATG) proteins. The main steps and ATG proteins involved in the autophagy process are depicted in Fig. 1. In brief, the autophagosome starts to form from an ‘omega-shaped’ membrane (the phagophore) in the proximity of the endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi area. Two important events mark this step. First, the cytosolic protein LC3 normally associated with the microtubules (MAP-LC3) is sequentially processed by certain ATG proteins (including ATG4, ATG5, ATG7, and ATG12) to be conjugated to phosphatidylethanolamine and thereafter be inserted into the bilayer of both the inner and outer membrane of the autophagosome. This vacuolar form of LC3 is known as isoform LC3-II. Second, while the autophagosome is under construction, the autophagy substrate (e.g., protein aggregates) to be degraded is bound by the p62/SQSTM1 protein and sequestered in the lumen. In the case of mitophagy, oxidized mitochondria are sequestered via interaction with BNIP3. The autophagosome will eventually fuse with endosomes and lysosomes to form the amphysome and autolysosome, respectively. The acidic pH and the hydrolytic enzymes (especially, cathepsins) ensure the complete digestion of the material within the autolysosome, from which the elementary substrates will be released in the cytoplasm for recycling.

Fig. 1.

Autophagy pathway. A schematic overview of the “canonical” pathway, and the main autophagy-related proteins and regulators: the picture shows the three steps starting from the phagophore formation, elongation, and maturation of autophagosome, until the autophagosome-lysosome fusion. The ATG proteins dispensable in the non-canonical pathway are light blue colored. For details refer to the text. ATG: autophagy-related gene or protein.

→: activation or induction; ⟂: inhibition; : interaction.

The autophagy process is finely tuned by redundant pathways that sense the lack of nutrients and growth factors or energy sources as well as the presence of bacteria and viruses in the cytoplasm or endocytic organelles.16 The main signaling pathways that control autophagy involve the PI3KC1-AKT-mTORC1 negative axis and the AMPK-mTORC1-ULK1 positive axis. The mTORC1 complex is the central hub receiving signals from amino acids, growth factors, and glucose, and controls negatively autophagy by inhibiting the ULK1 complex, whereas AMPK, triggered by the rise of AMP following ATP production impairment (as it occurs, for instance, when glucose is lacking), inhibits mTORC1 and activates ULKC1. Downstream to ULKC1 is the Vps15-BECLIN1-PI3KC3-ATG14L complex, known as the “autophagy interactome”, which starts the signal for the autophagosome formation.

The autophagy pathway described above is known as the “canonical” pathway, which is typically active at a basal rate in all eucaryotic cells for keeping the macromolecular homeostasis, and that is hyper-induced under starvation or proteotoxic stress. Besides, other noncanonical pathways have been described where certain ATG proteins (e.g., BECLIN1, ATG5, ATG7) are unnecessary for autophagosome formation.17,18 Alternative non-canonical regulatory pathways apart from the classic mTORC1–ULK1 circuit have also been described.19 For instance, it has been reported the regulation of BECLIN1-dependent autophagy via a MEK/ERK pathway20 and a MAPK/JNK pathway.21 Both canonical and non-canonical pathways are regulated at genetic and epigenetic levels, and thus the two pathways are dynamically modulated and can overlap depending on the metabolic state of the cell and the type of stimulus. To be noted, non-canonical autophagy pathways play a pivotal role in xenophagy, i.e. the lysosomal-mediated destruction of phagocytosed or intracellular localized microbes.22, 23, 24 For instance, one such non-canonical autophagy pathway is the so-called LC3-associated phagocytosis (LAP), where pathogens recognized by Toll-Like Receptors (TLR) are engulfed in single membrane vacuoles (endosomes, phagosomes) decorated with lipidated LC3. Recently, it has been shown that LAP protects from Influenza A Virus (IAV) pathogenicity, limiting viral replication in the lungs and preventing lung inflammation.25 Another non-canonical autophagy pathway is the so-called secretory autophagy, which can be hijacked by viruses for their engulfment into exosomes from where they are released and thus spread to other cells.24

3. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 cell infection and replication: interaction with the autophagy-lysosome system

Coronaviruses (CoVs) genome is made up of a long (∼30 kb) single-stranded positive-sense RNA, typically organized in a 5′ cap structure, followed by the leader sequence, the untranslated region (UTR), the sequences coding for replicase polyproteins, structural and accessory proteins, and finally the 3′ UTR along with a polyA tail.26 The SARS-CoV-2 genome includes at the 5′-terminal two overlapping open reading frames (ORF1a and 1b) encoding two polyproteins (pp1a/1 ab) that eventually are processed into 16 non-structural proteins (nsps), followed at the 3′-terminal by the coding sequences for the main structural proteins S (Spike), E (Envelope), M (Membrane) and N (Nucleocapside). Moreover, many other accessory proteins are involved in pp1a/pp1b processing, such as the chymotrypsin-like protease (3CLPRO; aka Main protease MPRO) and papain-like proteinases (PL1PRO and PL2PRO) and in genome replication27 (see also Fig. 3 below). Nsps, arising from the processing of pp1a/1 ab, are necessary to form the replication-transcription complex (RTC). The S protein (∼180 kDa), a class I fusion protein, forms homotrimers that mediate the attachment to human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (hACE2) on the host cell surface through its receptor-binding domain (RBD). The M protein (25–30 kDa) is crucial for promoting both the induction of membrane curvature and the binding to the N protein, while E protein is necessary for assembly and release of the viral genome. Lastly, N protein interacts with M protein and nsp3, a component of RTC, to promote the packaging of the viral genome into the viral particles.28

Fig. 3.

Potential autophagic-inhibiting properties of herbs and natural compounds in SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19. The in silico research on herbs-compounds that may target SARS-CoV-2 proteins involved in autophagy and vesicle-dependent viral entry and replication. For all docking scores, see Table 1.

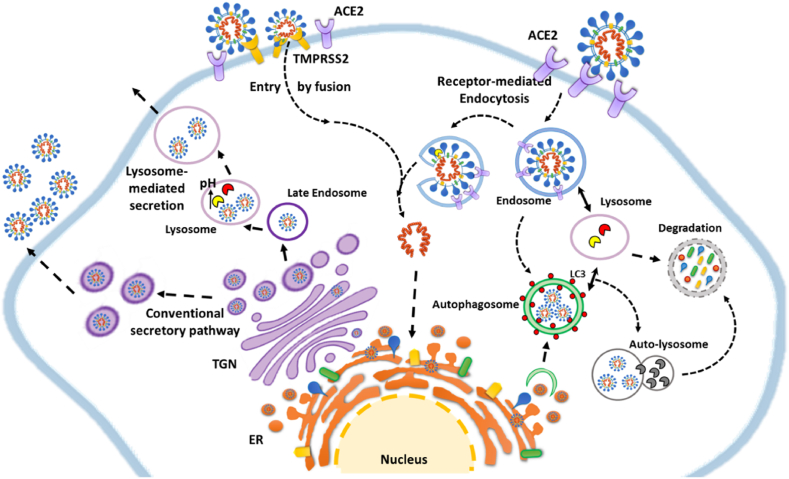

The mechanisms through which CoV enter the cells, replicate within, and exit from them are illustrated in Fig. 2. In brief, CoV life cycle begins once the virus has entered the target host cell. The main path for CoV entry is via clathrin-mediated or clathrin/caveolae-independent endocytosis.28,29 The endocytosed virus can be delivered to the autophagy-lysosomal organelles for degradation. Within the endosome, the β-CoV ssRNA triggers the Toll-like receptor (specifically TLR7 and TLR8) response.30 However, the virus RNA can escape from endocytic vesicles (upon cathepsin L-mediated processing of S and virus envelope-membrane fusion), and relocate in the cytoplasm, where here again it could (or not) be trapped within autophagosomes (which also are provided with TLRs). Additionally, the virus may enter the cell by lipid blending of the virus envelope and the host cell membrane. Cells expressing ACE2 on the membrane are specifically targeted by SARS-CoV-2 through the S protein.31 Whichever the path used for entering the cell, the cleavage of the S protein into the subunits S1 and S2 by host proteases such as endosomal cathepsin L, furin, trypsin, transmembrane protease serine protease 2 (TMPRSS-2), or human airway trypsin-like protease is an obligated step for allowing the fusion between the viral envelope and host cell membranes (either endosomal or plasma membrane) and the release of the genome into the cytoplasm.31,32 Accordingly, inhibition of this proteolytic step greatly reduces the cellular viral load.28,31

Fig. 2.

Cellular mechanistic interaction between coronavirus and endocytic-autophagy-lysosomal compartment. The cartoon shows an overview of strategies related to the modulation of autophagy during the entry (receptor-mediates endocytosis and fusion), viral replication and exit of virions (conventional secretory pathway and lysosome-mediated secretion). For details refer to the manuscript. TGN = Trans Golgi Network; ER = Endoplasmic reticulum; ACE2 = angiotensin-converting enzyme 2.

→ and -→ = promotion; = interaction.

Once the viral genome is free in the cytoplasm, the translation at the endoplasmic reticulum starts with the synthesis of the pp1a and pp1ab that are subsequently processed to produce the nsps. The latter, and particularly nsps 3, 4, and 6, induce the formation of a double-membrane vesicle (DMV) from deranged membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum.33 Also, the 3′-terminal of the viral genome is translated to produce the S, E, M, N, and accessory proteins. Meanwhile, the RNA genome is replicated. DMV is the platform where the virus assembles.28 It has been reported that CoV particles egress the cell via the conventional secretory pathway passing through the Golgi apparatus. Yet, it seems that β-CoV virions are preferentially de-routed into the endosomal-lysosomal system and then secreted via calcium-dependent lysosome exocytosis.34

The connection between β-CoV infection/replication and autophagy was first recognized in studies on Mouse Hepatitis Virus (MHV), Infectious Bronchitis Virus (IBV), Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS-CoV), and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-CoV-1 (SARS-CoV-1).35 Intriguingly, the DMV used for β-CoV assembly resembles the structure of the autophagosome, although it is smaller in size (<0.3 μm) and contains LC3-I, but not LC3-II.36 Both canonical and noncanonical autophagy pathways are triggered by and play a role in CoV infection and replication.37 Interestingly, knock-down of either ATG5, ATG7, or BECLIN1 did not abrogate (or it could improve) CoVs replication in cultured cells38 (reviewed in37), suggesting that noncanonical autophagy probably plays a major role. To be noted, the actual role of macroautophagy in viral infection is double-faced, as it can either promote or inhibit viral replication,39 the outcome likely reflecting the cell type (with its genetic and epigenetic background) and the surrounding microenvironment that together impinge on the regulation of autophagy. Additionally, viral proteins impact the autophagy-lysosomal machinery as briefly illustrated below. Particularly, like other virus families, CoVs have evolved strategies to hijack autophagy at different steps to benefit from its stimulation or inhibition while avoiding degradation.39 For instance, human SARS-CoV nsp6 stimulates autophagosome formation and at the same time, it limits autophagosome expansion and fusion with lysosomes, thus impairing autophagy clearance efficiency.10,40,41 The combined effect is that autophagosomal membranes accumulate and could be retrieved for the generation of DMV, where the virus assembles.41,42 Further, it has been hypothesized that such an effect in antigen-presenting cells would compromise the capability of autophagosomes to deliver viral components to lysosomes for degradation as well as reducing antigen presentation and/or exposure to TLRs.41 In line with this finding, it has been shown that membrane-associated papain-like protease PLP2 (PLP2-TM) of SARS-CoV interacts with BECLIN1 and promotes the accumulation of autophagosomes through impairment of autophagosome-lysosome fusion.43 In the same line, MERS-CoV replication was associated with proteasomal degradation of BECLIN1 and impaired fusion of autophagosomes and lysosomes.44 Inhibiting BECLIN1 degradation restored autophagy and drastically reduced MERS-CoV replication,44 implying that stimulation of autophagy to completion could be a strategy for limiting the viral output.

The mechanistic interaction between CoV entry, replication, and exit processes with the endocytic, autophagy, and endosomal-lysosomal system is schematized in Fig. 2.

Taken together, the studies on the five better known CoVs, namely IBV, MHV, MERS, SARS-CoV-1, and SARS-CoV-2, indicate that during their infection and propagation these viruses interact with the autophagy-lysosomal system at three levels, and precisely: (i) when they enter via endocytosis and exploit endosomal cathepsin L; (ii) when they induce autophagosomes and meanwhile impair autolysosome formation, thus escaping from degradation and exploiting autophagosomal membranes for the construction of DMV; and (iii) when they exit via the unconventional lysosomal secretory pathway.

The relationship between autophagy and viral infection also includes the participation of autophagy in innate and adaptive immunity and modulation of the inflammatory response.45 Autophagy plays a major role in viral antigen processing and priming of CD4+ and CD8+ T-lymphocytes that is instrumental for humoral and cellular response to virus infection.39,46 Autophagy also dampens inflammation. Lack of ATG5 in dendritic cells resulted in increased secretion of proinflammatory cytokines upon respiratory syncytial virus infection.47 Similarly, the lack of RUBICON, a BECLIN-1 interacting protein essential in the non-canonical autophagy pathway LAP, resulted in significant production of IL-6, IL-1β, and IL-12 upon viral infection.48

In the next paragraph, we present the natural products that have the potential to interfere with the autophagy-dependent infection and replication of the main human pathogenic viruses. We discuss their mechanism of action in light of similarities with SARS-CoV-2, and aim to provide additional supporting information for the development of new drugs for the management of the current pandemic.

4. Natural products targeting autophagy to halt cell-to-cell virus propagation

Herbs and natural compounds interfere in different stages of the viral cycle and exert a supportive role on the host immune response for clearing viral infections.49 For instance, berberine, baicalin, and resveratrol inhibited the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), influenza A virus (IAV), human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), and many others through different pathways.49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55 Here, we present a selection of herbs and phytocompounds that specifically explored autophagic mechanisms to counteract the infection and replication of RNA viruses such as enterovirus-71 (EV71), influenza viruses (H1N1, H3N2, H5N1, H9N2), and HCV. Also, we extended our search by looking at the in silico evidence of each herb-compound for its possible activity toward SARS-CoV-2 infection (Table 1, Table 2).

Table 1.

The influence of herbs-compounds on autophagy in RNA viral models and their potential to counteract autophagy through SARS-CoV-2/host protein inhibition. The second column provides a summary of autophagy markers after the intervention of natural products. The third column shows the interaction between SARS-CoV-2/host proteins and herbs-compounds. Herbs and compounds that block proteins implicated in the autophagic process may be able to inhibit viral entry, fusion, and endocytosis (S protein, ACE-2, S/ACE-2 complex, Furin, TMPSS2 receptor, Cathepsin-L (CTSL)) and autophagosome and DMV biogenesis (nsp3/PLPRO, nsp4, nsp6, nsp8, 3CLPRO, and possibly nsp2). Some of the herbs-compounds are multi-target proteins and could interfere in different phases of the viral life cycle. Note that, in the in silico studies, researchers have different opinions on the docking score levels able to strongly and stably block proteins and markers. Thus, some scores may be considered appreciable as protein inhibitors while others may be considered weak. NOTE: references to Table 1 are listed in supplementary file.

| Herb or phytocompound | Autophagic mechanisms/markers in response to herbs or phytocompounds in RNA viral models | SARS-CoV-2/host proteins (in silico studies – potential inhibition action of herbs-compounds) |

|---|---|---|

| Berberine (BBR) |

Autophagy induction (H1N1) – in vitro and in vivo animal models ↑ BNIP3 ↑ MMP ↑ LC3-II ↓ p62 ↓ mtROS ↓ caspase-1 ↓ 1L-1β ↓ NLRP3 (Liu et al., 2020) |

ACE-2: 71.50 kcal/mol (Lakshmi et al., 2020)

MAPK8: 8.6 kcal/mol TNF-α: 8.2 kcal/mol) MAPK1: 8.2 kcal/mol BAX: 8.1 kcal/mol) NF-Kβ1: 7.3 kcal/mol CHUK: 7.3 kcal/mol ACE-2 receptor: 9.8 kcal/mol (Wang et al., 2020) |

|

Autophagy inhibition (EV71) -(BBR and its derivative 2d) ↑ Akt ↑ SQSTM1/p62 ↓ JNK ↓ PI3K-III ↓ LC3B-II ↓ MEK/ERK No effect on Beclin-1 (Wang et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018) | ||

| Baicalin |

Autophagy inhibition (H3N2) ↑ mTOR ↓ LC3-II/GAPDH ratio ↓ Atg5-Atg12 (Zhu et al., 2015) |

Baicalin: 8.458 Herbacetin: 9.402 (Liu et al., 2021)

Hesperidin: 2.87 kcal/mol Baicalin: 6.68 kcal/mol) 21 Baicalin derivatives: 5.45 to - 7.78 kcal/mol (Ghosh et al., 2021)

Herbacetin: 8.738 Pectolinarin: 10.969 (Jo et al., 2020)

Nsp15: 7.4 kcal/mol RdRp: 8.7 kcal/mol (Alazmi and Motwalli, 2020)

3CLPRO: 6.58 kcal/mol PLPRO: 5.95 kcal/mol Furin: 7.40 kcal/mol (Manikyam and Joshi, 2020) |

| Resveratrol (RES) and RES-loaded nanoparticles |

Autophagy inhibition (EV71) ↓ p-PERK, P-eIF2, ATF4, GRP78, and CHOP ↓ LC3-II ↓ LC3-II/LC3-I ratio ↓ IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α ↓ MDA and ROS ↑ SOD (Du et al., 2019) |

RV12 (RdRp -173.76 kj/mol) (Ranjbar et al., 2020)

|

| Catechin (C) and Tea Polyphenols |

Autophagy inhibition (H1N1) ↓ M2 ↓ NP ↓ LC3B ↓ PI3K-III (Chang et al., 2020) |

CTSL: 7.68 kcal/mol S protein RBD: 5.79 kcal/mol nsp6: 7.04 kcal/mol N protein: 6.23 kcal/mol) (cut off range > 5.0 kcal/mol) (Mishra et al., 2020)

ACE-2: 8.9 kcal/mol S-RBD/ACE-2 complex: 9.1 kcal/mol (Jena et al., 2021)

3CLPRO-TF3: 8.4 kcal/mol S protein RBD-EGCG: 9.7 kcal/mol S RBD-TF3: 11.6 kcal/mol PLPRO-EGCG: 8.9 kcal/mol PLPRO-TF3: 11.3 kcal/mol RdRp-EGCG: 5.7 kcal/mol RdRp-TF3: 6.0 kcal/mol ACE2/S RBD-EGCG: 8.5 kcal/mol ACE2/S RBD-TF3: 8.0 kcal/mol (Mhatre et al., 2021) |

| Procyanidins |

Autophagy inhibition (IAV) ↓ LC3-II/β-actin ratio ↓ LC3-II accumulation ↓ LCB3-I to II conversion ↓ Atg7, 5, and 12 expression ↓ Atg5-Atg12/Atg16 heterotrimer Stabilized beclin1/bcl2 heterodimer (Dai et al., 2012–1) |

Procyanidin A2 (PA2): 9.2 (−)-epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate (EGCG): 8.7 (−)-gallocatechin-3-O-gallate (GCG): 8.7 (−)-epicatechin-3-O-gallete (ECG): 8.7 (+)-catechin-3-O-gallate (CAG): −8.3 (−)-epigallocatechin (EGC): 7.7 (+)-gallocatechin (GC): 7.6 (−)-epicatechin (EPC): 7.5 (+)-catechin (CA): 7.5 (−)-epiafzelechin (EAF): 7.5 (−)-afzelechin (AF): 7.0 Lopinavir (LOP): 8.0 Ebselen (EBS): 6.6 Cinanserin (INN): 5.4) (Zhu and Xie, 2020)

Theaflavin 3,3'di-gallate (TF3): 14.92 Theaflavin 3′-gallate (TF2a): 13.26 Digalloylprocyanidin B2: 13.26 3CLPRO: Procyanidin: 11.68 TF2a: 11.52 Theaflavin: 11.07 PLPRO: TF2a: 10.90 Theasinensin A: 10.81 Theasinensin B: 10.73 (Gogoi et al., 2021)

Nsp2: 8.8 kcal/mol PLPRO: 9.7 kcal/mol Nsp4: 9.7 kcal/mol Nsp6: 8.9 kcal/mol Nsp7: 8.1 kcal/mol Nsp8: 8.7 kcal/mol Nsp9: 8.4 kcal/mol Nsp10: 8.3 kcal/mol RdRp: 8.9 kcal/mol Helicase: 9.5 kcal/mol ExonN: 9.6 kcal/mol NendoU: 8.2 kcal/mol 2′-O-MT: 10.1 kcal/mol ORF3a: 7.9 kcal/mol E protein: 9.0 kcal/mol M protein: 7.8 kcal/mol ORF6: 6.7 kcal/mol ORF7a: 8.0 kcal/mol ORF8: 8.9 kcal/mol N protein: 9.7 kcal/mol ORF10: 7.2 kcal/mol ACE-2: 8.9 kcal/mol MPRO: 9.2 kcal/mol S protein: 9.5 kcal/mol (Maroli et al., 2020) |

| Quercetin-7-0-glucoside (Q7G) |

Autophagy inhibition (IAV) – in vitro ↓ Acidic Vesicular Organelles (AVO) ↓ Atg-5, Atg-7 ↓ LCB-3 ↓ ROS (Gansukh et al., 2016) |

S protein: 5.19 kcal/mol RdRp: 5.89 kcal/mol PLPRO: 5.41 kcal/mol Others: see original paper (Saakre et al., 2021) |

|

Saikosaponins (Ss) (SsA and SsD) |

Autophagy inhibition (EV71) – in vitro Activation of RAB-5 > defects in lysosome biogenesis and increase lysosomal pH ↑ Lysosomal pH > induces TFEB nuclear translocation Inhibition of autophagosome-lysosome fusion ↑ LC3-II accumulation ↑ p62 No effect on mTOR SsD-mediated autophagy > independent of ER or lysosomal Ca2+ pools (Li et al., 2019) |

S protein: 8.299 to -5.638 Strongest inhibitors: saikosaponin V and U (Sinha et al., 2020)

IL-6-SsV: −7.077 kcal/mol JAK3-SsB4: 7.981 kcal/mol JAK3-SsI: 7.942 kcal/mol NOX5-SsBK1: 7.813 kcal/mol NOX5-SsC: 9.202 kcal/mol Best interactions: JAK3-Ss compounds Saikosaponins interacted with CAT Gene CAT (Catalase) and Checkpoint kinase (CHEK1) (Chikhale et al., 2021) |

| Eugenol |

Autophagy inhibition (IAV) – in vitro ↓ ERK ↓ p38 MAPK ↓ IKK/NF-Kβ ↓ dissociation of Beclin 1-Blc-2 heterodimer ↓ TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-8 (Dai et al., 2013) |

S protein (6VXX): 6.1 kcal/mol EGCG: SARS-CoV-2 S protein: 9.8 kcal/mol 3CLPRO: 7.8 kcal/mol kcal/mol Hesperidin: SARS-CoV-2 3CLPRO(6LU7): 8.3 kcal/mol S protein (6VXX): 10.4 kcal/mol (Tallei et al., 2020)

Nsp15: 3.8 kcal/mol RdRp: 3.2 kcal/mol (Saxena et al., 2021)

Nsp15: 91.7 kj/mol ADP ribose phosphatase: 105.2 kj/mol RdRp: 80.0 kj/mol S protein: 79.1 kj/mol ACE-2: 88.4 kj/mol(≤ 80 kJ/mol: strongest docking activity) (Da Silva et al., 2020) |

| PGG |

Autophagy inhibition (RABV) – in vitro and in vivo animal model ↓ LC3-II ↑ SQSTM1/p62 ↑ mTOR ↓ viral absorption and entry ↓ viral titers ↓ P protein expression ↓ mRNA expression and protein synthesis ↓ symptoms and mortality (mice) (Tu et al., 2018) |

EGCG: H41 residue - 3.5 kcal/mol and C145 residue - 6.0 kcal/mol (Chiou et al., 2021)

|

| Aloe vera |

Autophagy inhibition (IAV) – in vitro Inhibition of IAV-induced autophagy > Fluorescence microscopy and Cyto-ID® Autophagy Detection Kit In silico – binding affinities: Aloe-emodin-M2: −5.47 kcal/mol Catechin hydrate-M2: −5.48 kcal/mol Quercetin-M2: −5.35 kcal/mol Amantadine-M2 (control): −4.52 kcal/mol (Choi et al., 2019) |

Aloe vera molecules- SARS-CoV-2 3CLPRO: Feralolide: 7.9 kcal/mol 9-dihydroxyl-2-O-(z)-cinnamoyl-7-methoxy-aloesia: 7.7 kcal/mol Aloeresin: 7.7 kcal/mol Isoaloeresin: 7.3 kcal/mol Aloin A: 7.1 kcal/mol Elgonica dimer A: 7.1 kcal/mol 7-O-methylaloeresin: 7.0 kcal/mol Chrysophanol: 6.8 kcal/mol Aloe-emodin: 6.7 kcal/mol Aloin B: 6.7 kcal/mol (Mpiana et al., 2020) |

| Evodiamine |

Autophagy inhibition (IAV) – in vitro ↓ Atg5-Atg12/Atg16 heterotrimer formation ↓ Atg5, Atg12, and Atg16 protein expression ↓ LC3-II and p62 accumulation ↓ AMPK/↓ TSC2/↑mTOR pathway ↓ TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 (Dai et al., 2012–2) |

No articles found |

| Deguelin |

Autophagy inhibition (HCV) – in vitro ↓ LC3B-II (LC3B-II/β-actin) ↓ LC3B–I to LC3B-II conversion ↑ p62 ↓ Beclin-1 (Liao et al., 2020) |

No articles found. |

| Kurarinone |

Autophagy inhibition (HCoV-OC43) – in vitro ↓ LC3-I/LC3-II transversion (LC3-II/LC3-I ratio) ↑ p62/SQSTM1 (Min et al., 2020) |

No articles found. |

Table 2.

Summary of herbs-compounds that may potentially inhibit SARS-CoV-2/host proteins. The proteins/receptors that would be especially important to prevent or inhibit SARS-CoV-2-induced autophagy are S, ACE-2, S/ACE-2 complex, TMPSS2, Furin, CTSL, nsp2, nsp3/PLPRO, nsp4, nsp5/3CLPRO, nsp6, and nsp8. This table shows the herbal-protein interactions. For specific docking scores see Table 1.

| SARS-CoV-2/host proteins | Herbs/Compounds |

|---|---|

| S protein | Berberine, Baicalin, Saikosaponins, Catechin (C), EGCG, TF3, Procyanidins, Eugenol, and Quercetins |

| ACE-2 receptor | Berberine, immunotherapeutic-BBR nanomedicine (NIT-X), Catechin (C), Procyanidins, Eugenol |

| S/ACE-2 complex | Resveratrol, Catechin (C), EGCG, TF3, Quercetins, PGG |

| Furin | Baicalin |

| TMPSS2 receptor | NIT-X |

| Cathepsin-L (CTSL) | Catechin (C) |

| Nsp1 | Procyanidins |

| Nsp2 | Procyanidins |

| PLPRO(is a domain of nsp3) | Baicalin (interacted with PLPRO), Resveratrol, EGCG, TF3, TF2a, Theasinesin, Procyanidins, Quercetins |

| ADP ribose phosphatase | Eugenol |

| Nsp4 | Baicalin, Procyanidins |

| Nsp5/3CLPRO(processes nsp4-16) | Berberine, Scutellaria baicalensis, baicalein, baicalin, baicalin derivatives, Catechin (C), EGCG, TF3, Procyanidins, GCG, ECG, CAG, EGC, GC, EPC, EAF, AF, TF2a, Eugenol, PGG, Quercetins, Aloe vera compounds (e.g. feralolide, 9-dihydroxyl-2-O-(z)-cinnamoyl-7-methoxy-aloesia and aloeresin) |

| Nsp6 | Catechin (C), Procyanidins |

| Nsp7 | Procyanidins |

| Nsp8 | Procyanidins |

| Nsp9 | Procyanidins |

| Nsp10 | Procyanidins |

| Nsp12 (RdRp) | Baicalin, Resveratrol, EGCG, TF3, TF2a, Procyanidins, Eugenol, Quercetins |

| Nsp13 (Helicase) | Procyanidins |

| Nsp14 (ExonN) | Baicalein (nsp14 N and C terminals), Procyanidins |

| Nsp15 (NendoU) | Baicalin, Saikosaponins, Procyanidins, Eugenol, Quercetins |

| 2′-O-ribose methyltransferase (MTase) - nsp16 | Baicalin, Procyanidins |

| N protein | Catechin (C), catechin skeleton compounds, Procyanidins |

| ORF3a, E protein, M protein, ORF6, ORF7a, ORF8, ORF10 | Procyanidins |

4.1. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity of berberine

Berberine (BBR) is an isoquinoline alkaloid present in several herbal species such as Coptidis rhizome, Phellodendron chinese, and Berberis vulgaris.56 BBR was able to contrast the influenza virus H1N1 infection through stimulation of the autophagy flux and mitophagy, as indicated by the upregulation of BNIP3 and LC3-II expression.57 Consequently, BBR mitigated the mitochondrial production of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, and reduced activation of caspase-1 and secretion of IL-1β, thus improving pulmonary inflammatory lesions, edema, and hemorrhage in pneumonia-induced influenza.57 Additionally, BBR was shown to prevent enterovirus 71 replication by inhibiting the virus-mediated induction of autophagy, which consistently suggests that induction of autophagosome formation was instrumental to virus biogenesis and assembly.58

Molecular docking and dynamics simulations revealed that BBR significantly interacts with SARS-CoV-2 3CLPRO, S protein, and ACE2 receptor59, 60, 61 (Table 1). This suggests that BBR could prevent viral entry and fusion and interfere with the autophagy processes and the biogenesis of DMV by affecting the 3CLPRO-mediated generation of nsps 4–16.62 Accordingly, BBR potently inhibited SARS-CoV-2 replication.63,64 Advantages of using BBR include the reported low cytotoxicity and high cellular viability, prevention of infection at low concentrations, no serious adverse effects, and easy penetration in various organ systems (e.g., liver, kidneys, muscles, and brain).63,65 Disadvantages to its use include poor aqueous solubility and rapid metabolism. Yet, this issue can be resolved by using nanoparticles and lipid-based nanocarriers.65

4.2. Anti-CoV activity of baicalin and baicalein

Baicalin, a flavonoid extracted from Scutellaria baicalensis can hinder the formation of autophagosomes and inhibit the H3N2-induced autophagy by counteracting the mTOR suppression in the infected epithelial and macrophage cells.66 Also, baicalin downregulated the expression of LC3-II, ATG5, and ATG12, and this led to a decreased virus replication.66 Baicalin may interact with the SARS-CoV-2 S and PLPRO, nsp4, and 3CLPRO proteins,3,34,67,68 suggesting another way to prevent the induction of autophagy. Notably, the in silico evidence indicates the potential of baicalein, baicalin, and some baicalin derivatives to block 3CLPRO3,34,69,70, baicalin to counteract nsp4, nsp15, nsp16, RdRp, and furin,66,67,71 and baicalein to inhibit nsp14 N and C terminals.72

4.3. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity of resveratrol

Resveratrol (RV) is a naturally occurring stilbene molecule of the polyphenol family present in plants such as Polygonun cuspidatum, Panax pseudoginseng, Smilax glabra, and Aloe vera L. var. chinensis.73 RV effectively decreased the synthesis of EV71 capsid protein VP1 and virus replication along with attenuation of oxidative stress and inhibition of cytokines IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α secretion.74 Also, RV reduced the expression of N protein and contrasted virus-induced apoptosis in MERS-CoV-infected cells.75 In vitro studies show that RV may be effective at suppressing CoVs including the SARS-CoV-2 with low cytotoxicity while maintaining cell viability even at high concentrations.76,77 In silico analysis demonstrated the ability of RV and its derivatives to strongly and stably block SARS-CoV-2 proteins PLPRO, RdRp, and S protein.78,79 RV could act as an ACE2 receptor inhibitor, preventing the formation of the S1/ACE2 complex and viral endocytosis, and DMV biogenesis. Furthermore, RV could impact the autophagic process through inhibition of PLPRO-mediated generation of nsps. These actions make RV an interesting candidate for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

4.4. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 properties of Catechin

Catechins are major polyphenol compounds found in green tea leaves. There are five major types of catechins, namely catechin, epicatechin, epigallocatechin, epicatechin-3-O-gallate, and epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate.80 Catechin decreased the viral load of influenza A virus (IAV) H1N1 in a dose-dependent manner and protected the infected cells, and this effect was associated with inhibition of H1N1 M2 and NP proteins and downregulation of autophagy.81 Catechin interfered with SARS-CoV-2 infection and replication by neutralizing 3CLPRO, S protein RBD, ACE2, S/ACE2 complex, cathepsin L, nsp6, and N protein.82, 83, 84 Tea polyphenols, including epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate (EGCG) and theaflavin 3,3'di-gallate, can strongly dock to 3CLPRO, S protein, S/ACE2 complex, PLPRO, and RdRp.85, 86, 87 Also, a computational analysis revealed that several compounds with a common catechin skeleton can inhibit SARS-CoV-2 protein N.88 Altogether, these compounds could suppress the SARS-CoV-2 replication through the inhibition of viral proteins involved in DMV biogenesis and autophagy. However, green tea polyphenols have low bio-accessibility (90% is lost upon gastric and intestinal digestion) and low bioavailability. Therefore, more research is needed to inform clinical applications of catechins for CoVs.

4.5. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 properties of procyanidins

While catechins are monomers of flavan-3-ol, procyanidins are oligomers and polymers of flavan-3-ol units found especially in Vaccinium aungustifolium Ait (blueberry), Vitis vinifera L. (grape seed), and Cinnamomum cassia Presl (cinnamon bark).89 Procyanidin can significantly inhibit IAV replication in a concentration-dependent manner with no cytotoxicity.90 Importantly, procyanidin's antiviral mechanism is associated with reduced production and accumulation of LC3-II and decreased expression of ATG5, ATG7, and ATG12 90. Additionally, procyanidin inhibited the formation of ATG5-ATG12/ATG16 heterotrimer and stabilized the BECLIN1/BCL-2 heterodimer.90 These data support the idea that the antiviral property of procyanidin relies on its ability to inhibit the autophagy process. Procyanidin A2 and B1 have shown moderate anti-SARS-CoV activity.91 The latest research has evidenced the capacity of procyanidins to significantly interact with SARS-CoV-2 3CLPRO, nsp1, nsp2, PLPRO, nsp4, nsp6, nsp7, nsp8, nsp9, nsp10, RdRp, helicase, exon N, NendoU, 2′-O-MT, ORF3a, E protein, M protein, ORF6, ORF7a, ORF8, N protein, ORF10, ACE2, and S protein.84,87,92 Interestingly, flavan-3-ols and procyanidins were also associated with ACE inhibition in vitro.93 These studies highlight the extension of the potential of flavanols (e.g. procyanidins and catechins) to inhibit SARS-CoV-2/host proteins, especially those involved in DMV biogenesis and the regulation of autophagy. However, like catechins, procyanidins have a limited absorption,94 and modes of administration that optimize cell delivery may need to be developed to further the SARS-CoV-2 model studies.

4.6. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity of quercetin-7-0-glucoside

Quercetin-7-0-glucoside (Q7G) is composed of a glucosyl residue attached at position 7 of quercetin via a β-glycosidic link. In IAV-infected cells, Q7G prevented IAV replication by blocking viral RNA synthesis, and in parallel prevented the accumulation of acidic vesicular organelles.95 However, the labeling of acidic organelles with acridine orange indicates that Q7G only prevented the organelle acidification during the viral infection, and nothing can be said about autophagy. The molecular docking analysis revealed that Q7G blocks the PB2 subunit of the RdRp (- 9.5 kcal/mol), which is important for RNA viral synthesis.95 In silico studies have evidenced different interaction strengths of quercetin(s) with SARS-CoV-2 3CLPRO, S protein, S/ACE2 complex, RdRp, PLPRO, and nsp15.96, 97, 98, 99, 100 Based on the above, it is conceivable that quercetins could prevent SARS-CoV-2 endocytosis, DMV formation, and SARS-CoV-2-dysregulation of autophagy (the latter, by blocking PLPRO and 3CLPRO-mediated generation of nsps 4–16). However, further studies are needed to validate this hypothesis.

4.7. Saikosaponin (Ss), Eugenol, 1,2,3,4,6-penta-O-galloyl-β-d-glucose (PGG), Aloe vera, evodiamine, deguelin, and Kurarinone: inhibition of virus-induced autophagy

Another series of less discussed herbs and phytocompounds have demonstrated their capacity to inhibit autophagic pathways to suppress RNA viral replication.

The triterpenoid saponins saikosaponin A (SsA) and B (SsB) extracted from Bupleurum falcatum and other Bupleurum spp. can activate RAB-5, increase lysosomal pH, inhibit autophagosome-lysosome fusion in EV71-infected HeLa cells resulting in the accumulation of autophagosomes.101 This was interpreted as autophagy inhibition rather than stimulation of autophagy in the early stages.101 Also, saikosaponins (A and B2) have shown anti-human coronavirus 229E (hCoV-229E) activity in vitro with no toxicity.102 SsB2 was confirmed as a novel anti-CoV potently hindering the viral attachment and entry during the early stage and detaching the viruses that had already adhered to cells.102 Also, SsD is capable of strongly reducing viral RNA replication, protein synthesis, and titers with little toxicity while significantly inhibiting EV71-induced cell death.101 In silico studies have ascertained the capacity of saikosaponins to potently block SARS-CoV-2 S protein and nsp15.103 Thus, saikosaponins could be valuable resources to fight viral-induced autophagy, reduce inflammation, ROS, necrosis, and cell damage in COVID-19.

Eugenol, the major constituent of Sygygium aromaticum, inhibited IAV replication along with the inhibition of autophagy.104 One possible mechanism for downregulation of autophagy relies on the ability of Eugenol to inhibit the dissociation of BECLIN1-BCL-2 heterodimer.104 So far, the research on Eugenol for SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 has been restricted to a few in silico studies. Eugenol appears to be able to interact with some of the virus/host proteins such as 3CLPRO, S protein, ACE2, nsp15, RdRp, and ADP ribose phosphatase, thus interfering in the viral life cycle by preventing the attachment to target cells, endocytosis, and DMV biogenesis.86,105,106

PGG (1,2,3,4,6-penta-O-galloyl-β-d-glucose), a simple hydrolysable tannin present in many medicinal plants such as Rhus chinensis Mill and Peonia suffruticosa, demonstrated inhibitory activity against rabies virus (RABV) limiting viral RNA synthesis in infected mice and in vitro. This effect was associated with mTOR-mediated inhibition of autophagy.107 On the contrary, PGG was active against IAV, limiting the expression of viral M2 and NP proteins through induction of autophagy.108 In silico studies show that PGG can interact with SARS-CoV-2 3CLPRO and S/ACE2 complex109,110 (Supplementary Table 1). Additional in vitro and FRET analyses also demonstrated that PGG may hinder SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 109. Altogether, PGG could halt SARS-CoV-2 through impeding attachment and endocytosis, and through modulation of the autophagic pathway.

Aloe vera extract can suppress IAV (H1N1 and H3N2)-induced autophagy.111 In vitro, Aloe vera extract limited the expression of all influenza viral proteins (M1, M2, and HA) in a concentration-dependent manner, and reduced viral mRNA levels.111 Since suppression of IAV M2 proton channel activity leads to the blockage of autophagosome-lysosome fusion, interactions between M2 and Aloe vera compounds such as aloe-emodin, catechin, and quercetin could potentially provide autophagy-mediated antiviral options for RNA viral infections.111 Based on the in silico activity against 3CLPRO, Aloe vera molecules may indirectly inhibit DMV formation and SARS-CoV-2 induced autophagy112 (Table 1). However, Aloe vera and its isolates may inhibit other SARS-CoV-2 structural and non-structural proteins that we are unaware of.

Evodiamine, the major active compound of Evodia rutaecarpa, was shown to inhibit IAV-induced autophagy by either acting on the AMPK/TSC2/mTOR pathway or by suppressing ATG5, ATG12, and ATG16 protein expression.113 However, the possible inhibitory effects of evodiamine or Evodia rutaecarpa on CoVs infection and replication have not been explored yet.

Deguelin is a rotenoid extracted from plants of the Leguminosae family such as Mundulea sericea (bark), Derris trifoliata Lour (root), Tephrosia vogelli Hook (leaves), and Derris trifoliate (root).114,115 Deguelin inhibited the HCV-induced autophagy at its early stage, as demonstrated by downregulation of LC3B–I to LC3B-II conversion and accumulation of p62/SQSTM1.115 Deguelin also suppressed the expression of BECLIN1 leading to the activation of type I IFN response, which further contributed to the inhibition of viral replication.115 Whether deguelin can exert similar antiviral activity on CoVs has not been investigated yet.

Kurarinone, a flavanone present in S. flavescens, has demonstrated its ability to inhibit HCoV-OC43 in vitro in a dose-dependent manner (IC50 3.34 μM) at the early stage of infection.116 This antiviral activity was paralleled by inhibition of autophagy, as indicated by decreased LC3-I/LC3-II conversion and increased level of p62/SQSTM1.116 As of now, there are no studies on Sophora flavescens and its phytocompounds for SARS-CoV-2.

5. Limitations and perspectives

It is evident that we have a lot more information on natural products that inhibit rather than induce autophagy for contrasting RNA viral infections. Also, some herbs (e.g., berberine) could either promote or inhibit autophagy. It may appear confusing that the reported studies on the antiviral effect elicited by the natural products could be obtained either way, through induction or inhibition of autophagy. One first possible explanation resides in differences in the experimental models such as the type of RNA virus researched, i.e., its modality of entry in the cell, its replication and egress from the cell, and the genetic background of the cell (that determine how the autophagy stress response is regulated). Importantly, the RNA virus itself can induce autophagy or impair the autophagy flux depending on its stage of replication, i.e., the viral proteins being synthesized and processed. Besides, and most importantly, we have to consider the methodology employed to assess autophagy, which could lead to misinterpretations of the actual role of autophagy. In fact, not all the studies strictly adhered to the guidelines when choosing the markers and the appropriate pharmacologic/genetic manipulations of ATG proteins for monitoring autophagy.15 Another important limitation when interpreting these data is represented by the stage of the infection at which the involvement of autophagy is investigated. These natural products have a broad action in the regulation of the vesicular traffic that include endocytosis, DMV biogenesis, autophagosome formation and maturation, endosomal-lysosomal secretion, which means they can intervene in all the steps of the viral life cycle. Thus, a natural product as a proper therapeutic agent must be selected in terms of concentration, according to the autophagy developmental stage, and of its effective role in the precise step of virus infection. The timing of administration of the herb-derived antiviral drug acting on autophagy likely impacts the outcome, which could mean either improvement or worsening of the symptoms in COVID-19 patients. This is well illustrated in the case of hydroxychloroquine, the antimalarial alkaloid from chinkuna repurposed for COVID-19 treatment.

One of the most challenging issues in drug discovery is finding drugs that exert antiviral properties while still preserving cell viability. Besides, cytotoxicity, solubility, and bioavailability are also important concerns. This is especially troubling when dealing with viruses that can rapidly cause tissue damage, lung fibrosis, oxidative stress, and impaired tissue function. Many of the herbs reviewed here exerted anti-SARS-CoV-2 action at low concentrations, with acceptable bioavailability, and minimum or no cytotoxicity. Nonetheless, low bioavailability could be overcome through the inclusion of the natural biomolecules in lipid-based nanoparticles.61,74 Since viruses need to import or synthesize lipid constituents to make DMVs,62 we theorize that herbal-loaded lipid-nanocarriers, especially those that target nsps involved in the DMV biogenesis and inhibition of the autophagy flux, could be a smart way to easier penetrate cells, modulate autophagy, and hinder SARS-CoV-2. However, since CoVs can create a variety of strategies to use or mimic the host autophagic machinery to replicate, uncovering unexplored autophagy signaling pathways and mechanisms involved in the SARS-CoV-2 infection may open other possibilities for the use of phytocompounds.

Although the SARS-CoV-2 mutations are happening much more slowly than HIV and influenza virus, researchers detected 12,706 mutations in its genome, the majority being single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (reviewed in117). Viral mutations can be neutral, beneficial, or deleterious. So far, the majority of mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 genome are considered neutral, and most of them involve the nsp6, nsp11, nsp13, and S protein (reviewed in117). The role of SARS-CoV-2 structural and non-structural protein mutations on the autophagic process is still uncertain.118 As autophagy is a double-edged sword, it is unclear, for example, if nsp6 mutations would favor viral replication and evasion from the host immune response, or if it would counteract it.118 However, the main mutation of the D614G variant is at the interface between the individual spike protomers, and not in the RBD of S protein.117,119 Therefore, the herbs and compounds seen to block the S protein RBD are still potentially useful to impede adhesion and halt virus-induced autophagy. As the mutations continue to happen, their interference in the autophagic machinery and the usefulness of herbs and compounds depend on our understanding of these same mutations.

6. Concluding remark

The interaction between autophagy, either canonical and non-canonical, and virus infection is complex and may result in: (i) the virus is effectively degraded via autophagy (virophagy) or (ii) the virus de-regulates the process and uses the autophagy machinery for its replication and egression from the cell.120 Several drugs targeting autophagy have been repurposed as possible therapeutics for COVID-19.12,121 Here, we reported the literature data on natural products that showed an effect on the autophagy process in RNA viral infections. Based on the similarity among RNA viruses, and the research of these herbs for SARS-CoV-2, we hypothesize that they may also work for SARS-CoV-2. Yet, extensive additional research is necessary to validate in vivo this hypothesis. In support of our hypothesis, we also associated, first hand, the results of the in silico research of herbs and natural compounds for SARS-CoV-2 and how intervention on the reported target proteins could hinder attachment, fusion, endocytosis, and DMV biogenesis and consequently inhibit virus-induced autophagy (Fig. 3).

Thus, in silico research could provide important hints for research on target proteins and autophagic pathways for viral infections. In this line, a recent review uncovered the capacity of artemisinin derivatives to block SARS-CoV-2/host proteins such as artesunate (3CLPRO, E protein, helicase, N protein, and nsp3, 10, 14, and 15), artemisinin (3CLPRO, GRP78 receptor), artemether (N protein, helicase, nsp10, and nsp15), MOL736 (cathepsin-L), artelinic acid (S protein), arteannuin B (N protein), and artenimol/DHA (N protein).122 As the strongest inhibition were attained by artesunate and artemisinin, it gives us a hint that they may potentially impede DMV biogenesis and autophagy, and hinder viral replication pointing to potential future research. Interestingly, a recent in vitro study reported the suppression of SARS-CoV-2 and two of its variants (UK B1.1.7 and South Africa B1.351) by the A. annua hot water leaf extract.123 In this study, artemisinin was not the main antiviral agent, while artesunate, artemether, and dihydroartemisinin were deemed ineffective or cytotoxic at elevated concentrations.123 Likely, the viral inhibition was due to the combined components present in the plant, their great bioavailability, and yet unexplored mechanisms (e.g., autophagy). Ultimately, the treatment goal would be to hand back the control of the autophagy machinery to the host no matter the disease stage, while also exerting other biological properties such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antipyretic, analgesic, and anti-pulmonary fibrosis. In this line, it is worth mentioning that phytochemicals elicit an anti-inflammatory activity through modulating autophagy in stromal cells as well, including fibroblasts and immune cells.10 Accordingly, one of the attractive advantages of deepening the knowledge of autophagic pathways for SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 is the direct modulatory therapeutic interventions on the host rather than acting on the virus, which is prone to mutations over time.

Author's contribution

All authors worked in a coordinated and integrated manner. Specifically, CV and AFe: literature searching and drafting of chapters 1–3, drawing of Fig. 1, Fig. 2 and of Graphical Abstract; AFu: literature search and drafting of chapters 4, limitations and perspectives, conclusion, Table 1, Table 2, and Fig. 3; CI: conceptualization, coordination of the teamwork, revision, harmonization, and finalization of the whole manuscript. All authors have read and approved the last version.

Declaration of competing interest

Nothing to declare.

Acknowledgements

CV is supported with a post-doctoral fellowship from Università del Piemonte Orientale (Novara, Italy) in collaboration with Università degli Studi Magna Græcia (Catanzaro, Italy). AFe is recipient of a post-doctoral fellowship “Paolina Troiano” (id. 24094) granted by Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC, Milan, Italy). Thanks to Associazione per la Ricerca Medica Ippocrate-Rhazi (ARM-IR, Novara, Italy) for support.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of The Center for Food and Biomolecules, National Taiwan University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcme.2021.10.003.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quiles J.L., Rivas-García L., Varela-López A., Llopis J., Battino M., Sánchez-González C. Do nutrients and other bioactive molecules from foods have anything to say in the treatment against COVID-19? Environ Res. 2020;191:110053. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Islam M.T., Sarkar C., El-Kersh D.M., et al. Natural products and their derivatives against coronavirus: a review of the non-clinical and pre-clinical data. Phytother Res. 2020;34(10):2471–2492. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colunga Biancatelli R.M.L., Berrill M., Catravas J.D., Marik P.E. Quercetin and vitamin C: an experimental, synergistic therapy for the prevention and treatment of SARS-CoV-2 related disease (COVID-19) Front Immunol. 2020;11:1451. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merarchi M., Dudha N., Das B.C., Garg M. Natural products and phytochemicals as potential anti-SARS-CoV-2 drugs. Phytother Res. 2021 doi: 10.1002/ptr.7151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alam S., Sarker M.M.R., Afrin S., et al. Traditional herbal medicines, bioactive metabolites, and plant products against COVID-19: update on clinical trials and mechanism of actions. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:671498. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.671498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuzimoto A.D., Isidoro C. The antiviral and coronavirus-host protein pathways inhibiting properties of herbs and natural compounds - additional weapons in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic? J Tradit Complement Med. 2020;10(4):405–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2020.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swargiary A., Mahmud S., Saleh M.A. Screening of phytochemicals as potent inhibitor of 3-chymotrypsin and papain-like proteases of SARS-CoV2: an in silico approach to combat COVID-19. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2020:1–15. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1835729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basu A., Sarkar A., Maulik U. Molecular docking study of potential phytochemicals and their effects on the complex of SARS-CoV2 spike protein and human ACE2. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):17699. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-74715-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Limanaqi F., Busceti C.L., Biagioni F., et al. Cell clearing systems as targets of polyphenols in viral infections: potential implications for COVID-19 pathogenesis. Antioxidants. 2020;9(11):1105. doi: 10.3390/antiox9111105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller K., McGrath M.E., Hu Z., et al. Coronavirus interactions with the cellular autophagy machinery. Autophagy. 2020;16(12):2131–2139. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2020.1817280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sargazi S., Sheervalilou R., Rokni M., Shirvaliloo M., Shahraki O., Rezaei N. The role of autophagy in controlling SARS-CoV-2 infection: an overview on virophagy-mediated molecular drug targets. Cell Biol Int. 2021;45(8):1599–1612. doi: 10.1002/cbin.11609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sumpter R., Jr., Levine B. Selective autophagy and viruses. Autophagy. 2011;7(3):260–265. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.3.14281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yin Z., Pascual C., Klionsky D.J. Autophagy: machinery and regulation. Microb Cell. 2016;3(12):588–596. doi: 10.15698/mic2016.12.546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klionsky D.J., Abdel-Aziz A.K., Abdelfatah S., et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (4th edition) Autophagy. 2021;17(1):1–382. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2020.1797280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corona Velazquez A.F., Jackson W.T. So many roads: the multifaceted regulation of autophagy induction. Mol Cell Biol. 2018;38(21):e00303–e00318. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00303-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Codogno P., Mehrpour M., Proikas-Cezanne T. Canonical and non-canonical autophagy: variations on a common theme of self-eating? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;13(1):7–12. doi: 10.1038/nrm3249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dupont N., Codogno P. Non-canonical autophagy: facts and prospects. Curr Pathobiol Rep. 2013;1:263–271. doi: 10.1007/s40139-013-0030-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Bari M.A.A., Xu P. Molecular regulation of autophagy machinery by mTOR-dependent and -independent pathways. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2020;1467(1):3–20. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang J., Whiteman M.W., Lian H., et al. A non-canonical MEK/ERK signaling pathway regulates autophagy via regulating Beclin 1. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(32):21412–21424. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.026013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou Y.Y., Li Y., Jiang W.Q., Zhou L.F. MAPK/JNK signalling: a potential autophagy regulation pathway. Biosci Rep. 2015;35(3) doi: 10.1042/BSR20140141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanjuan M.A., Dillon C.P., Tait S.W., et al. Toll-like receptor signalling in macrophages links the autophagy pathway to phagocytosis. Nature. 2007;450(7173):1253–1257. doi: 10.1038/nature06421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sil P., Muse G., Martinez J. A ravenous defense: canonical and non-canonical autophagy in immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2018;50:21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2017.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pleet M.L., Branscome H., DeMarino C., et al. Autophagy, EVs, and infections: a perfect question for a perfect time. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018;8:362. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y., Sharma P., Jefferson M., et al. Non-canonical autophagy functions of ATG16L1 in epithelial cells limit lethal infection by influenza A virus. EMBO J. 2021;40(6) doi: 10.15252/embj.2020105543. Epub 2021 Feb 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fehr A.R., Perlman S. Coronaviruses: an overview of their replication and pathogenesis. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1282:1–23. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2438-7_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan J.F., Kok K.H., Zhu Z., et al. Genomic characterization of the 2019 novel human-pathogenic coronavirus isolated from a patient with atypical pneumonia after visiting Wuhan. Emerg Microb Infect. 2020;9(1):221–236. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1719902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong N.A., Saier M.H., Jr. The SARS-coronavirus infection cycle: a survey of viral membrane proteins, their functional interactions and pathogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(3):1308. doi: 10.3390/ijms22031308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burkard C., Verheije M.H., Wicht O., et al. Coronavirus cell entry occurs through the endo-/lysosomal pathway in a proteolysis-dependent manner. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tatematsu M., Funami K., Seya T., Matsumoto M. Extracellular RNA sensing by pattern recognition receptors. J Innate Immun. 2018;10(5-6):398–406. doi: 10.1159/000494034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ou X., Liu Y., Lei X., et al. Characterization of spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 on virus entry and its immune cross-reactivity with SARS-CoV. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):1620. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15562-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tang T., Bidon M., Jaimes J.A., Whittaker G.R., Daniel S. Coronavirus membrane fusion mechanism offers a potential target for antiviral development. Antivir Res. 2020;178:104792. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Angelini M.M., Akhlaghpour M., Neuman B.W., Buchmeier M.J. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus nonstructural proteins 3, 4, and 6 induce double-membrane vesicles. mBio. 2013;4(4) doi: 10.1128/mBio.00524-13. e00524-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghosh S., Dellibovi-Ragheb T.A., Kerviel A., et al. β-Coronaviruses use lysosomes for egress instead of the biosynthetic secretory pathway. Cell. 2020;183(6):1520–1535. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.039. e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jackson W.T. Viruses and the autophagy pathway. Virology. 2015;479–480:450–456. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reggiori F., Monastyrska I., Verheije M.H., et al. Coronaviruses Hijack the LC3-I-positive EDEMosomes, ER-derived vesicles exporting short-lived ERAD regulators, for replication. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7(6):500–508. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bello-Perez M., Sola I., Novoa B., Klionsky D.J., Falco A. Canonical and noncanonical autophagy as potential targets for COVID-19. Cells. 2020;9(7):1619. doi: 10.3390/cells9071619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao Z., Thackray L.B., Miller B.C., et al. Coronavirus replication does not require the autophagy gene ATG5. Autophagy. 2007;3(6):581–585. doi: 10.4161/auto.4782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choi Y., Bowman J.W., Jung J.U. Autophagy during viral infection - a double-edged sword. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2018;16(6):341–354. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0003-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cottam E.M., Maier H.J., Manifava M., et al. Coronavirus nsp6 proteins generate autophagosomes from the endoplasmic reticulum via an omegasome intermediate. Autophagy. 2011;7(11):1335–1347. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.11.16642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cottam E.M., Whelband M.C., Wileman T. Coronavirus NSP6 restricts autophagosome expansion. Autophagy. 2014;10(8):1426–1441. doi: 10.4161/auto.29309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jackson W.T., Giddings T.H., Jr., Taylor M.P., et al. Subversion of cellular autophagosomal machinery by RNA viruses. PLoS Biol. 2005;3(5):e156. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen X., Wang K., Xing Y., et al. Coronavirus membrane-associated papain-like proteases induce autophagy through interacting with Beclin1 to negatively regulate antiviral innate immunity. Protein Cell. 2014;5(12):912–927. doi: 10.1007/s13238-014-0104-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gassen N.C., Niemeyer D., Muth D., et al. SKP2 attenuates autophagy through Beclin1-ubiquitination and its inhibition reduces MERS-Coronavirus infection. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):5770. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13659-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuballa P., Nolte W.M., Castoreno A.B., Xavier R.J. Autophagy and the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:611–646. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-074948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Münz C. Autophagy proteins in antigen processing for presentation on MHC molecules. Immunol Rev. 2016;272(1):17–27. doi: 10.1111/imr.12422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oh D.S., Park J.H., Jung H.E., Kim H.J., Lee H.K. Autophagic protein ATG5 controls antiviral immunity via glycolytic reprogramming of dendritic cells against respiratory syncytial virus infection. Autophagy. 2020:1–17. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2020.1812218. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang C.S., Rodgers M., Min C.K., et al. The autophagy regulator Rubicon is a feedback inhibitor of CARD9-mediated host innate immunity. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11(3):277–289. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Warowicka A., Nawrot R., Goździcka-Józefiak A. Antiviral activity of berberine. Arch Virol. 2020;165(9):1935–1945. doi: 10.1007/s00705-020-04706-3. Epub 2020 Jun 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ding Y., Dou J., Teng Z., et al. Antiviral activity of baicalin against influenza A (H1N1/H3N2) virus in cell culture and in mice and its inhibition of neuraminidase. Arch Virol. 2014;159(12):3269–3278. doi: 10.1007/s00705-014-2192-2. Epub 2014 Jul 31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shi H., Ren K., Lv B., et al. Baicalin from Scutellaria baicalensis blocks respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection and reduces inflammatory cell infiltration and lung injury in mice. Sci Rep. 2016;6:35851. doi: 10.1038/srep35851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oo A., Rausalu K., Merits A., et al. Deciphering the potential of baicalin as an antiviral agent for Chikungunya virus infection. Antivir Res. 2018;150:101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.12.012. Epub 2017 Dec 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li B.Q., Fu T., Dongyan Y., Mikovits J.A., Ruscetti F.W., Wang J.M. Flavonoid baicalin inhibits HIV-1 infection at the level of viral entry. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;276(2):534–538. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moghaddam E., Teoh B.T., Sam S.S., et al. Baicalin, a metabolite of baicalein with antiviral activity against dengue virus. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5452. doi: 10.1038/srep05452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Abba Y., Hassim H., Hamzah H., Noordin M.M. Antiviral activity of resveratrol against human and animal viruses. Adv Virol. 2015;2015:184241. doi: 10.1155/2015/184241. Epub 2015 Nov 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Neag M.A., Mocan A., Echeverría J., et al. Berberine: botanical occurrence, traditional uses, extraction methods, and relevance in cardiovascular, metabolic, hepatic, and renal disorders. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:557. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu H., You L., Wu J., et al. Berberine suppresses influenza virus-triggered NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophages by inducing mitophagy and decreasing mitochondrial ROS. J Leukoc Biol. 2020;108(1):253–266. doi: 10.1002/JLB.3MA0320-358RR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang Y.X., Yang L., Wang H.Q., et al. Synthesis and evolution of berberine derivatives as a new class of antiviral agents against enterovirus 71 through the MEK/ERK pathway and autophagy. Molecules. 2018;23(8):2084. doi: 10.3390/molecules23082084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alagu Lakshmi S., Shafreen R.M.B., Priya A., Shunmugiah K.P. Ethnomedicines of Indian origin for combating COVID-19 infection by hampering the viral replication: using structure-based drug discovery approach. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2020:1–16. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1778537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chowdhury P. In silico investigation of phytoconstituents from Indian medicinal herb 'Tinospora cordifolia (giloy)' against SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) by molecular dynamics approach. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2020:1–18. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1803968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang Z.Z., Li K., Maskey A.R., et al. A small molecule compound berberine as an orally active therapeutic candidate against COVID-19 and SARS: a computational and mechanistic study. Faseb J. 2021;35(4) doi: 10.1096/fj.202001792R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wolff G., Melia C.E., Snijder E.J., Bárcena M. Double-membrane vesicles as platforms for viral replication. Trends Microbiol. 2020;28(12):1022–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2020.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Varghese F.S., van Woudenbergh E., Overheul G.J., et al. Berberine and obatoclax inhibit SARS-cov-2 replication in primary human nasal epithelial cells in vitro. Viruses. 2021;13(2):282. doi: 10.3390/v13020282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pizzorno A., Padey B., Dubois J., et al. In vitro evaluation of antiviral activity of single and combined repurposable drugs against SARS-CoV-2. Antivir Res. 2020;181:104878. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Batista M.N., Braga A.C.S., Campos G.R.F., et al. Natural products isolated from oriental medicinal herbs inactivate zika virus. Viruses. 2019;11(1):49. doi: 10.3390/v11010049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhu H.Y., Han L., Shi X.L., et al. Baicalin inhibits autophagy induced by influenza A virus H3N2. Antivir Res. 2015;113:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chandra A., Chaudhary M., Qamar I., Singh N., Nain V. In silico identification and validation of natural antiviral compounds as potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 methyltransferase. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2021:1–11. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2021.1886174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Manikyam H.K., Joshi S.K. Whole genome analysis and targeted drug discovery using computational methods and high throughput screening tools for emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) J Pharm Drug Res. 2020;3(2):341–361. PMID: 32617527; PMCID: PMC7331973. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu H., Ye F., Sun Q., et al. Scutellaria baicalensis extract and baicalein inhibit replication of SARS-CoV-2 and its 3C-like protease in vitro. J Enzym Inhib Med Chem. 2021;36(1):497–503. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2021.1873977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jo S., Kim S., Kim D.Y., Kim M.S., Shin D.H. Flavonoids with inhibitory activity against SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro. J Enzym Inhib Med Chem. 2020;35(1):1539–1544. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2020.1801672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Alazmi M., Motwalli O. In silico virtual screening, characterization, docking and molecular dynamics studies of crucial SARS-CoV-2 proteins. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2020:1–11. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1803965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu C., Zhu X., Lu Y., Zhang X., Jia X., Yang T. Potential treatment with Chinese and Western medicine targeting NSP14 of SARS-CoV-2. J Pharm Anal. 2021;11(3):272–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2020.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tian B., Liu J. Resveratrol: a review of plant sources, synthesis, stability, modification and food application. J Sci Food Agric. 2020;100(4):1392–1404. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.10152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Du N., Li X.H., Bao W.G., Wang B., Xu G., Wang F. Resveratrol-loaded nanoparticles inhibit enterovirus 71 replication through the oxidative stress-mediated ERS/autophagy pathway. Int J Mol Med. 2019;44(2):737–749. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2019.4211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lin S.C., Ho C.T., Chuo W.H., Li S., Wang T.T., Lin C.C. Effective inhibition of MERS-CoV infection by resveratrol. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):144. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2253-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pasquereau S., Nehme Z., Haidar Ahmad S., et al. Resveratrol inhibits HCoV-229E and SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus replication in vitro. Viruses. 2021;13(2):354. doi: 10.3390/v13020354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yang M., Wei J., Huang T., et al. Resveratrol inhibits the replication of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in cultured Vero cells. Phytother Res. 2021;35(3):1127–1129. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ranjbar A., Jamshidi M., Torabi S. Molecular modelling of the antiviral action of Resveratrol derivatives against the activity of two novel SARS CoV-2 and 2019-nCoV receptors. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24(14):7834–7844. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202007_22288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wahedi H.M., Ahmad S., Abbasi S.W. Stilbene-based natural compounds as promising drug candidates against COVID-19. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2021;39(9):3225–3234. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1762743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Xu J., Xu Z., Zheng W. A review of the antiviral role of green tea catechins. Molecules. 2017;22(8):1337. doi: 10.3390/molecules22081337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chang C.C., You H.L., Huang S.T. Catechin inhibiting the H1N1 influenza virus associated with the regulation of autophagy. J Chin Med Assoc. 2020;83(4):386–393. doi: 10.1097/JCMA.0000000000000289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mishra C.B., Pandey P., Sharma R.D., et al. Identifying the natural polyphenol catechin as a multi-targeted agent against SARS-CoV-2 for the plausible therapy of COVID-19: an integrated computational approach. Briefings Bioinf. 2021;22(2):1346–1360. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbaa378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jena A.B., Kanungo N., Nayak V., Gbn Chainy, Dandapat J. Catechin and curcumin interact with S protein of SARS-CoV2 and ACE2 of human cell membrane: insights from computational studies. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):2043. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-81462-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhu Y., Xie D.Y. Docking characterization and in vitro inhibitory activity of flavan-3-ols and dimeric proanthocyanidins against the main protease activity of SARS-cov-2. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:601316. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.601316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mhatre S., Naik S., Patravale V. A molecular docking study of EGCG and theaflavin digallate with the druggable targets of SARS-CoV-2. Comput Biol Med. 2021;129:104137. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2020.104137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tallei T.E., Tumilaar S.G., Niode N.J., et al. Potential of plant bioactive compounds as SARS-CoV-2 main protease (mpro) and spike (S) glycoprotein inhibitors: a molecular docking study. Sci Tech Rep. 2020;2020:6307457. doi: 10.1155/2020/6307457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gogoi M., Borkotoky M., Borchetia S., Chowdhury P., Mahanta S., Barooah A.K. Black tea bioactives as inhibitors of multiple targets of SARS-CoV-2 (3CLpro, PLpro and RdRp): a virtual screening and molecular dynamic simulation study. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2021:1–24. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2021.1897679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fernández J.F., Lavecchia M.J. Small molecule stabilization of non-native protein-protein interactions of SARS-CoV-2 N protein as a mechanism of action against COVID-19. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1860828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Woo-Sik Jeong & Ah-Ng Tony Kong Biological properties of monomeric and polymeric catechins: green tea catechins and procyanidins. Pharmaceut Biol. 2004;42:84–93. doi: 10.3109/13880200490893500. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dai J., Wang G., Li W., et al. High-throughput screening for anti-influenza A virus drugs and study of the mechanism of procyanidin on influenza A virus-induced autophagy. J Biomol Screen. 2012;17(5):605–617. doi: 10.1177/1087057111435236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhuang M., Jiang H., Suzuki Y., et al. Procyanidins and butanol extract of Cinnamomi Cortex inhibit SARS-CoV infection. Antivir Res. 2009;82(1):73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Maroli N., Bhasuran B., Natarajan J., Kolandaivel P. The potential role of procyanidin as a therapeutic agent against SARS-CoV-2: a text mining, molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation approach. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2020:1–16. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1823887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Actis-Goretta L., Ottaviani J.I., Keen C.L., Fraga C.G. Inhibition of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) activity by flavan-3-ols and procyanidins. FEBS Lett. 2003;555(3):597–600. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01355-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Serra A., Macià A., Romero M.P., et al. Bioavailability of procyanidin dimers and trimers and matrix food effects in in vitro and in vivo models. Br J Nutr. 2010;103(7):944–952. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509992741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gansukh E., Kazibwe Z., Pandurangan M., Judy G., Kim D.H. Probing the impact of quercetin-7-O-glucoside on influenza virus replication influence. Phytomedicine. 2016;23(9):958–967. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zhang D.H., Wu K.L., Zhang X., Deng S.Q., Peng B. In silico screening of Chinese herbal medicines with the potential to directly inhibit 2019 novel coronavirus. J Integr Med. 2020;18(2):152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.joim.2020.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Abian O., Ortega-Alarcon D., Jimenez-Alesanco A., et al. Structural stability of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro and identification of quercetin as an inhibitor by experimental screening. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;164:1693–1703. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.07.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]