Abstract

Social scientists are increasingly interested in methodological advances that can illuminate the distinct experiences and health outcomes produced by various systems of inequality (e.g., race, gender, religion, sexual orientation). However, innovative methodological strategies are needed to (a) capture the breadth, complexity, and dynamic nature of moments co-constructed by multiple axes of power and oppression (i.e., intersectional experiences) and (b) keep pace with the increasing interest in testing links between such events and health among underresearched groups. Mixed methods designs may be particularly well suited for these needs, but are seldom adopted. In light of this, we describe a new mixed methods experience sampling approach that can aid researchers in detecting and understanding intersectional experiences, as well as testing their day-to-day associations with aspects of health. Drawn from two separate experience sampling studies examining day-to-day links between intersectional experiences and psychological health—one focusing on Black American LGBQ individuals and another on Muslim American LGBQ individuals—we provide quantitative and qualitative data examples to illustrate how mixed methods investigations can advance the assessment, interpretation, and analysis of everyday experiences constructed by multiple systems of power. Limitations, possible future adaptations, implications for research, and relevance to the clinical context are discussed.

Keywords: mixed methods, experience sampling, intersectionality, stigma, LGBQ people of color

The U.S. context is shaped by multiple, long-enduring systems of advantage and disadvantage (e.g., White supremacy, patriarchy, capitalism) that differentially influence the experiences of people belonging to varying social groups (Collins, 1990; hooks, 1981). In recent decades, there has been growing interest in measuring and eliminating the health disparities resulting from such forms of social stratification, including a surge of research within counseling psychology to understand how social identity, stigma, and power may influence the psychosocial well-being of marginalized populations (e.g., Balsam & Mohr, 2007; Pieterse et al., 2012). Such work has advanced knowledge on how various axes of inequality (e.g., race, gender, religion, sexual orientation) inform everyday events, cognitive processes, and day-to-day mental health outcomes in vulnerable subgroups, including among individuals harmed by multiple, potentially interlocking systems of power (Jackson et al., 2020; Lewis et al., 2016; Nadal et al., 2015).

Intersectionality is the most well-established framework to guide the study of how multiple systems of privilege and oppression interlock to shape social life (Collins, 1990; Crenshaw, 1989). Rooted in Black feminist thought, critical race theory, and feminist legal studies, intersectional theorists propose that seemingly distinct macro-level systems of power— such as White supremacy and patriarchy—are often interconnected. While the framework of intersectionality has enriched the field of counseling psychology and advanced psychological research more broadly, its application within the field has been fraught with challenges. Both qualitative and quantitative research methods require careful consideration and modification to accurately detect and interpret experiences shaped by interlocking systems of inequality, and to evaluate their impact on health outcomes (Bowleg, 2008; Parent et al., 2013). Although scholars are beginning to consider the relative compatibility of various methodologies with intersectional theory (Bauer & Scheim, 2019; Bowleg, 2012; Else-Quest & Hyde, 2016b), such work is rare. Additionally, many efforts have focused on the strengths and limitations of qualitative and quantitative research, respectively, overlooking the distinct abilities of mixed methods study designs to detect elusive social phenomena (Castro et al., 2010; Hanson et al., 2005).

The present paper contributes to the growing interest and dialogue in this area, delineating how mixed methods experience sampling research can aid in identifying and studying intersectional experiences: any personal event or situation—whether major or minor—that is directly influenced by multiple systems of power. We begin with a brief introduction to intersectionality, before tracing the evolution of one particular thread of intersectionality scholarship: the study of intersectional experiences. We then provide our rationale for studying intersectionality in a manner that (a) focuses on experiences, as opposed to analyzing social identities as proxies for experiences (Cole, 2008), (b) considers both negative and positive intersectional experiences, based on individuals’ subjective viewpoints, and (c) uses an experience sampling mixed methods design. Lastly, we describe our methodology and provide examples from two recent experience sampling investigations of Black LGBQ and Muslim LGBQ people, respectively, to illustrate how mixed methods research addresses several gaps and methodological challenges in intersectionality research.

Intersectionality: Origins, Evolutions, and Experiences

Intersectionality asserts that systems of inequality interlock to co-construct individuals’ everyday lives, regularly conferring privilege or subjugation based upon each person’s location within power-stratified categories. Legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw popularized the term intersectionality within academia to highlight the ways Black women were differentially susceptible to legal bias, violence, discrimination, and intra-community invisibility within the U.S. context (Crenshaw, 1989, 1991). Her seminal works served to name a concept articulated by multiple Black feminist and womanist organizations outside of academia (e.g., Combahee River Collective, 1979), and numerous other Black women, including scholar-activists, literary authors, and poets (Collins, 1989; Davis, 1983; hooks, 1981; Lorde, 1984; Walker, 1983). The principal argument was that, even if summed together, feminist discourse (which implicitly prioritizes Whiteness) and anti-racist discourse (which implicitly prioritizes maleness) do not encompass the mutually-constitutive views, experiences, needs, and barriers of Black women.

Clarifying an Increasingly Multidisciplinary Concept

In recent decades, the use of intersectionality and related frameworks (e.g., matrix of domination; Collins, 1990) has increased within psychology, public health, and the social sciences more generally (Bauer, 2014; Bowleg, 2008; Cole, 2009; Moradi & Grzanka, 2017). However, as intersectional analyses have become more widely used within the social sciences, few new guidelines have been established to shepherd this work. There are, however, a number of unifying principles that contemporary scholars of intersectionality tend to agree upon. The first is a basic assumption that individuals are characterized by their relative position within multiple hierarchical power systems (e.g., race, gender, sexual orientation, religion, class), and that their various locations within these categories are mutually interdependent (Bowleg, 2012; Else-Quest & Hyde, 2016a). Second, it is argued that these social identities are stratified within systems of inequity, and thus, some groups experience relative advantage (i.e., power, unearned privileges), whereas others endure disadvantage (i.e., disenfranchisement, oppression; Cho et al., 2013; Cole, 2009; Moradi & Grzanka, 2017). Third, scholars of intersectionality argue that structural, macro-level manifestations of power (e.g., laws, institutional practices, social norms) differentially shape the everyday, micro-level experiences of individuals (Bowleg, 2012; Else-Quest & Hyde, 2016a). Finally, intersectional theorists contend that the salience of various vectors of privilege and oppression are context dependent, and thus, dynamic across time and space (Cho et al., 2013; A.-D. Christensen & Jensen, 2012; Else-Quest & Hyde, 2016a).

As intersectionality has grown in popularity, the term has proven vulnerable to misuse. Intersectionality was largely developed by and for women of color, with a particular emphasis on illuminating the easily-obscured experiences of interlocking oppression that Black women face (Nash, 2008). Thus, although intersectionality can conceivably be used to analyze all people’s experiences, the framework has had an enduring focus on the multiply marginalized. As a result, intersectionality is regularly conflated with multiple minority stress, a phrase that typically refers to the compounded strain associated with holding multiple marginalized social identities. Although some multiple minority stress experiences may reflect intersectional dynamics (e.g., gendered manifestations of racism endured by Black women; Lewis et al., 2016), many do not. For example, multiple minority stress typically relies on an additive or “double jeopardy” view of how different forms of stigma impact the multiply marginalized. This is in conflict with the staunchly non-additive approach of intersectionality, which makes clear that “the intersectional experience is greater than the sum” (Crenshaw, 1989, p. 140). Thus, unlike intersectionality, multiple minority stress can refer to an individual’s experience of various forms of discrimination, even if they are non-interlocking (e.g., experiencing Islamophobia and transphobia at different times within a week). Intersectionality can be further distinguished in that, despite the framework’s long-held focus on oppression (Bauer, 2014; McCall, 2005), it is also equipped to analyze the construction of privilege (Moradi & Grzanka, 2017).

Intersectional Experiences

One early and enduring area of interest among scholars of intersectionality concerns daily experiences. In fact, Sojourner Truth’s famous “Ain’t I A Woman?” speech (1851), one of the earliest recorded articulations of intersectional ideas, charged listeners to consider her everyday experiences as evidence that Black women were granted a qualified sense of womanhood and human dignity. Within their seminal intersectional works, Crenshaw (1989, 1991) and Collins (1989, 1998) also shared narratives from their personal lives—and the lives of those they knew—both to reveal how intersectional forces color everyday experiences and articulate theory:

Experiences of women of color are frequently the product of intersecting patterns of racism and sexism, and how these experiences tend not to be represented within the discourses of either feminism or antiracism. Because of their intersectional identity as both women and of color within discourses that are shaped to respond to one or the other, women of color are marginalized within both.

(Crenshaw, 1991, p. 1243)

The types of experiences cited within early intersectionality scholarship regularly included: (a) stereotypes based upon multiple systems of oppression (e.g., Black women being characterized as a mammy, a bulldager, or as sexually promiscuous; Combahee River Collective, 1979), (b) intra-community stigma (e.g., oppression, tokenism, and erasure within the predominantly White, middle class women’s movements; Collins, 1989; Crenshaw, 1989; Truth, 1851), and (c) the overall invisibility of Black women’s subjugation (e.g., violence; Crenshaw, 1991).

Contemporary social scientific research on intersectional experiences reflects many of these through-lines. For instance, numerous studies highlight that intersectional dynamics can produce distinct stereotypes, but today, this work has expanded to discuss the experiences of additional social groups. Within psychology, this research has helped to uncover distinct assumptions and characterizations based not only upon gender/race (Jerald et al., 2017; Keum et al., 2018; Lewis et al., 2016; Sevelius, 2013), but also upon intersections that include one’s lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer (LGBQ) status, such as studies on race/sexual orientation (Calabrese et al., 2018; Petsko & Bodenhausen, 2019; Wilson et al., 2009), age/sexual orientation (Wright & Canetto, 2009), and gender/sexual orientation (Mohr et al., 2013). The aforementioned interest in intra-community stigma has also endured, spurring numerous qualitative (Bowleg, 2013; Han, 2007; Mark, 2008; Minwalla et al., 2005), growing quantitative (Balsam et al., 2011; McConnell et al., 2018), and occasional mixed methods contributions (Bowleg et al., 2008; Juan et al., 2016). Engaging these themes, one investigation combined data from six qualitative studies focusing on various marginalized populations (Nadal et al., 2015), demonstrating that research participants can indeed identify intersectional experiences within their everyday lives, including intersectional stereotypes (e.g., gender-based stereotypes endured by Muslims, assumptions of criminality experienced by men of color) and intra-community discrimination (e.g., among LGBQ people within their racial and religious communities).

Counseling psychologists have greatly advanced the literature on intersectionality (for a review, see Shin et al., 2017), including works related to intersectional experiences. The field has not only contributed studies that aim to unearth and understand intersectional events, but also those that demonstrate how these experiences relate to health (Capodilupo & Kim, 2014; Cerezo et al., 2019; Lewis et al., 2017). For example, counseling psychology research suggests that— unless adequately coped with—intra-community stressors can trigger a sense of conflict between one’s social identities and undermine the degree to which one feels “at home” within their social groups (Jackson et al., 2020; Santos & VanDaalen, 2016; Sarno et al., 2015; Singh, 2013). Counseling psychologists have also been at the forefront of identifying intersectionally-informed resilience factors and coping strategies (Lewis et al., 2013; Singh, 2013), and imagining ways intersectionality may inform clinical practice (Burnes & Singh, 2016; Moradi, 2017).

Developing Our Mixed Methods Approach to Studying Intersectional Experiences

We had to make a number of decisions to determine how to best structure our studies, including our conceptualization of intersectionality and selection of a study design. Our decisions—and the rationale for each—are presented below.

Why Study Intersectionality via Everyday Experiences?

Although a variety of approaches to the study of intersectionality are needed to advance knowledge, focusing on everyday experiences offers unique benefits. First, we argue that experiences of intersectional dynamics—not multiple, intersecting social identities alone— should play a central role in health research. Whereas using social identities (e.g., asexual, Black, Muslim) as predictors can allow us to examine if one’s specific positions within multiple categories of inequality interact to produce distinct outcomes, such research does little to clarify why (e.g., because of what types of events) and how (e.g., through what mechanisms) residing at the intersection of axes of oppression impacts health (for a discussion of this tendency, see Shin et al., 2017). Minority health researchers have long critiqued the use of racial categories—which lack scientific meaning—instead of more suitable explanatory variables (e.g., experiences of racial stigma) to understand links between minority status and health (Helms et al., 2005). Indeed, scholars of intersectionality have cautioned against approaches focusing solely on social identities and positions—suggesting they obscure the root problems of power and oppression that are at the foundation of intersectionality—and have recommended instead a focus on social processes (Bauer, 2014; Bowleg, 2008; Cole, 2008).

Studying intersectional forces in the context of everyday experiences may also support researchers’ ability to conceptualize oppression and privilege as fluid over time, with the salience and meaning of group memberships changing across contexts. Such dynamic processes can be observed by monitoring how experiences related to interlocking systems of inequality manifest from day-to-day, across various environments, or in interactions with people who hold similar or different social identities. Additionally, a careful focus on everyday intersectional events may help safeguard against the tendency of researchers to unintentionally revert to additive analyses.

“[…] one way to circumvent the problem of non-additivity could be to focus on everyday life. Everyday lives are rarely—if ever—separated into processes related to gender, processes related to ethnicity, and processes related to class. On the contrary, everyday life is a melting-pot (Gullestad, 1989), and it must be seen as a condensation of social processes, interactions, and positions where intersecting categories are inextricably linked.”

(A.-D. Christensen & Jensen, 2012, p. 117)

This point can be further extended by considering Else-Quest and Hyde’s (2016) observation that, beyond additive and multiplicative effects, there exist intersectional effects wherein one’s “intersectional location may give rise to distinct phenomena” (p. 162). The study of everyday experiences may offer a means of identifying such intersectional dynamics, understanding their antecedents, and examining their incremental impact on well-being.

Daily experiences also are a social location at which the influence of macro-level factors on individuals is readily accessible—i.e., where structural forces, interpersonal relationships, and an individual’s social identities collide (Galliher et al., 2017). Thus, the study of everyday experiences is not mutually exclusive from the study of structural oppression but rather may represent a way to reveal the power-laden quality of social identities and how they relate to the social structures (e.g., healthcare, education, criminal justice system) people encounter within their daily lives (A.-D. Christensen & Jensen, 2012). For scholars in psychology and public health, who are often interested in identifying points of intervention through which to reduce the impacts of stigma (Bauer & Scheim, 2019), daily experiences may represent a site of modifiable mechanisms (e.g., resiliency factors) between macro-level structural forces and health inequities.

What Types of Experiences Should Count as Intersectional?

One of the fundamental questions we faced when designing our studies was how to define and assess intersectional experiences. We opted for an inclusive operationalization that centralizes each person’s perception of their own experiences, specifically with respect to whether they view an experience as reflecting the operation of multiple axes of power. We believed this approach was consistent with the feminist and womanist roots of intersectional theory. This approach also seemed to be a good match for the nascent state of knowledge on intersectional experiences in everyday life, which we thought called for a discovery-oriented perspective. As we later discuss, we implemented procedures to ensure that, at least to some extent, the experiences participants reported as intersectional were consistent with our definition.

One implication of our inclusive approach was that our participants might report positive events related to the operation of two marginalized identities. Understandably, intersectional dynamics are discussed most often with respect to their role in producing unjust and stressful circumstances; however, scholars have highlighted the positive experiences that can emerge within the context of cruel systems of oppression (Bowleg et al., 2016; Singh & McKleroy, 2011). Indeed, within her work pioneering on intersectionality, sociologist Patricia Hill Collins used an intersectional lens to speak about the strengths and power of Black women, including (a) the ways Black women’s culture (e.g., artistic expression) can serve as a means of self-definition and self-valuation in the face of dehumanization (Collins, 1986), (b) how solidarity and everyday acts of resistance are used to survive systems of subordination (Collins, 1989, 1993), and (c) the fact that some Black women embrace and celebrate their distinctive “outsider within” standpoint (Collins, 1986). Though positive and empowering, these micro-liberation events are not quite experiences of intersectional privilege—which refer to moments in which unfair advantages are conferred by axes of inequality. Rather, we define positive intersectional experiences as moments of healing, joy, and triumph despite unfair systems of power, not because of them.

Considering one of our populations of interest, it is easy to imagine that—against the backdrop of intersectional stigma, invisibility, isolation, and stress—a Muslim LGBQ individual can have occasional experiences of acceptance, visibility, connection, and resiliency related to both their religious and sexual minority identities (e.g., feeling prideful and validated by a positive representation of an LGBQ Muslim person within the context of LGBQ media, perceiving one’s sexual orientation to be affirmed and accepted within an Islamic space, feeling a sense of connection and catharsis after receiving support from an LGBQ Muslim friend). Although these are not experiences of intersectional oppression, they are still legitimately intersectional insofar as they are produced by multiple systems of social stratification. Ironically, many such positive intersectional experiences—including those provided above—are likely appraised as such at least in part because of prior experiences of intersectional oppression (e.g., lack of positive Muslim representation within the LGBQ media, anti-LGBQ persecution within Islamic communities, isolation from similar others). The fact that intersectional experiences can be both positive and negative underscores how the link between one’s social identities and one’s experiences varies across space and time (Else-Quest & Hyde, 2016a). Counseling psychologists, who have demonstrated a long-held commitment to social justice and to studying the positive aspects of human functioning (Gerstein, 2006), are well positioned to adopt a strengths perspective to study these moments of resiliency, perseverance, and collective coping.

Why Study Intersectionality Using Mixed Methods Experience Sampling?

Mixed methods experience sampling research has the potential to advance intersectional inquiry within the social sciences. Experience sampling designs (Mehl & Conner, 2012; Shiffman et al., 2008) use repeated measures to collect data over time, effectively allowing participants to “document their thoughts, feelings, and actions outside the walls of a laboratory and within the context of everyday life” (T. C. Christensen et al., 2003, p. 53). Experience sampling research—which can be qualitative, quantitative, or include both types of assessment— has advanced knowledge concerning how, when, and to what effect experiences related to one’s social identity occur. However, there is little precedent for mixed methods experience sampling research being applied to assess everyday intersectional dynamics “in ways that cumulatively capture the texture and breadth of people’s experiences” (Moradi & Grzanka, 2017, p. 505).

We presumed that a mixed methods experience sampling approach would be well suited to address the current limitations of intersectionality research in counseling psychology by detecting dynamic, context-dependent processes (e.g., temporal associations) and by testing the relations between individuals’ perceived intersectional experiences and health. Further, as opposed to cross-sectional mixed methods study designs—which are vulnerable to recall biases and cannot test temporal hypotheses—experience sampling mixed methods approaches allow researchers to identify short-term microprocesses, maximize ecological validity in quantitative and qualitative assessments, and minimize retrospective memory bias (Shiffman et al., 2008).

We were particularly interested in the potential of experience sampling methods to collect and analyze both quantitative and qualitative data within a single study. The increasing call to use mixed methods in intersectionality research has focused on the potential complementarity of quantitative and qualitative methods based on their relative strengths and weaknesses (e.g., Bowleg & Bauer, 2016; Else-Quest & Hyde, 2016b). Our research focus was on testing and explaining the relation between intersectional experiences and daily mood using quantitative methods, but we also wanted to learn more about the nature of these experiences in participants’ own words. These descriptions not only deepened our understanding of the associations uncovered by the quantitative analyses, but also allowed us to determine which of the experiences described were most consistent with our definition of intersectional experiences.

Mixed methods studies come in many forms and are often categorized according to the relative emphasis on qualitative versus quantitative data (Hanson et al., 2005), including studies in which one is emphasized more (i.e., nested design), both are equally emphasized (i.e., triangulation design), or in which either approach is adopted along with an advocacy lens (i.e., transformative design). Plano Clark and colleagues (2015) developed a typology of mixed method designs for investigating social phenomena over time, based on whether the qualitative data is collected (a) once at the first time-point (i.e., prospective design), (b) once at the final time point (i.e., retrospective design), or (c) along with quantitative data at every timepoint (i.e., concurrent design). Throughout the remainder of this paper, we refer to these taxonomies of mixed methods designs to discuss variations on our approach and to illustrate the rich possibilities for the application of mixed methods to the study of intersectional experiences.

Our Mixed Methods Experience Sampling Approach

To encourage the use of mixed methods experience sampling research and respond to calls for measures informed by intersectionality that capture both the breadth and nuanced texture of people’s experiences (Moradi & Grzanka, 2017), we detail our approach to detecting and studying intersectional experiences as executed within two mixed methods experience sampling studies: one unpublished and one published (Jackson et al., 2020). The studies were developed in response to the paucity of research that examines how multiple power-structured systems (e.g., race, religion, sexual orientation) jointly influence the psychological experiences of LGBQ racial and religious minorities. Focusing on two multiply oppressed subpopulations— Study 1 included Black LGBQ participants and Study 2 included Muslim LGBQ participants— these investigations featured nearly identical study aims. Both studies sought to (a) assess the prevalence, common manifestations, and stability of positive and negative intersectional experiences; (b) examine relations between positive and negative intersectional experiences, respectively, and psychological health (e.g., mood); and (c) test mediators between these links, including variables related to social identity strain (e.g., identity conflict between one’s sexual and racial/religious identities) and general psychological variables (e.g., rumination). Here we focus specifically on our three-step assessment of intersectional experiences. Details on other study variables and study covariates included to control for extraneous variance in outcome variables (e.g., day of participation, non-intersectional experiences) are available elsewhere (Jackson et al., 2020). Most variables were assessed quantitatively; that said, our assessment of everyday intersectional experiences balanced qualitative and quantitative data, reflecting a triangulation design (Hanson et al., 2005). We opted for this approach, in part, because it afforded us the flexibility to produce quantitatively focused studies (e.g., Jackson et al., 2020), qualitatively-focused studies, or studies that fully integrate qualitative and quantitative findings.

The primary goal of sharing this methodology is to showcase the unique assessment and data analytic possibilities that can arise from studying intersectional experiences using a mixed methods experience sampling study design, not to advocate for the inflexible implementation of this new approach. Thus, although we explain the rationale for our study design decisions and hope that researchers will apply this methodology to study intersectional experiences within the context of everyday life, this goal is secondary. To encourage researchers to think carefully and with flexibility as they consider how to design a mixed methods experience sampling study, we fluctuate between discussing (a) our approach, where we detail our method, prioritizing the decisions most relevant to mixed methods and/or intersectionality research, and (b) potential alterations to demonstrate how the essence of this method can be modified to align with different researchers’ conceptualizations of intersectionality, populations of interest, and study aims. Although we discuss our approach to both data collection and analysis within this section, we give more attention to our three-step data collection procedure, which reflects greater innovation and it lends itself to a number of different data analytic possibilities and theoretical lenses (e.g, post-positivism, constructivist, advocacy; Hanson et al., 2005).

Study Procedures

The Institutional Review Board of the University of Maryland, College Park, approved the two studies described herein. An account of our study procedures is provided in a separate empirical contribution (Jackson et al., 2020); thus, here we overview the design before focusing on three study decisions that have special implications for intersectionality research. Adopting a type of experience sampling methodology known as daily diary study design (Bolger et al., 2003), we asked respondents to complete an online survey—accessible via smartphone or computer— every day for one week. We collected qualitative and quantitative data together throughout our microlongitudinal process, reflecting a concurrent model (Plano Clark et al., 2015).

To reduce the burden on participants, we limited the time needed to complete the surveys (e.g., less than 15 minutes per day) and number of data collection points (i.e., seven days), as lengthy surveys administered over longer durations are cited as barriers to retention in daily diary research (Mehl & Conner, 2012). We opted to use what is referred to as a fixed-assessment schedule (Bolger et al., 2003), and imagined that assessing the day each evening before bed could support recall and aid participants in developing a survey response routine, thus further minimizing participant burden (T. C. Christensen et al., 2003). Therefore, each evening at the start of the survey period (6 PM Eastern Time), participants were emailed individualized links with participation recommended in the two hours prior to bedtime that day. Participants who missed a survey were reminded by email to complete the next day’s survey, and those who missed three surveys were reminded that only four in total could be missed before study disqualification. Our compensation protocol encouraged retention by providing participants with greater compensation for later surveys, with participants receiving $1 for each of the first through fifth surveys and $5 for each of the final two surveys.

Many of the decisions on how to structure our study were in some way informed by it being a mixed methods research study focusing on intersectionality. First, recruiting study participants based on multiple aspects of social identity inherently restricts those eligible to participate—this challenge is only exacerbated by the fact that much intersectionality research focuses on doubly stigmatized populations, which may be particularly difficult to reach. Thus, although remuneration is encouraged for all experience sampling studies given the time-intensive nature of study participation (T. C. Christensen et al., 2003; Mehl & Conner, 2012), we believe our ability to compensate participants (up to $15) was especially important because of the documented challenges in recruiting LGBQ people of color (DeBlaere et al., 2010).

Second, to conduct experience sampling research using a fixed-assessment schedule, researchers must consider how frequently to ask participants to report on their experiences. For those studying intersectional events, this can be difficult, considering the relative dearth of research on the prevalence of these experiences among various subpopulations. For example, we were not able to identify past research concerning the frequency of intersectional experiences among Black and/or Muslim LGBQ people. This raised a concern: Considering our relatively brief experience sampling period of one week, many participants may not have had any intersectional experiences to report—especially if they missed multiple surveys during their study period. To mitigate this issue, we elected to lengthen participants’ study period by one day for each missed survey. If resources allow, researchers may consider implementing a two-week study design, which is common within daily diary research (Galliher et al., 2017).

Finally, although confidentiality is always of high importance, for those conducting research among the multiply marginalized that involves the participants disclosing stigmatized social identities (e.g., sexual minority status, undocumented immigration status) and sensitive information (e.g., descriptions of negative intersectional experiences), additional protections are warranted. One manner in which we addressed this was to be particularly upfront and transparent about all safeguards put into place to protect privacy and, on multiple occasions, assuring participants that their data would not be linked with any identifying information. For example, we informed study participants that although compensation required us to obtain respondents’ names and mailing addresses, this information would be collected in a separate survey and participants were permitted to decline compensation.

Assessment of intersectional experiences

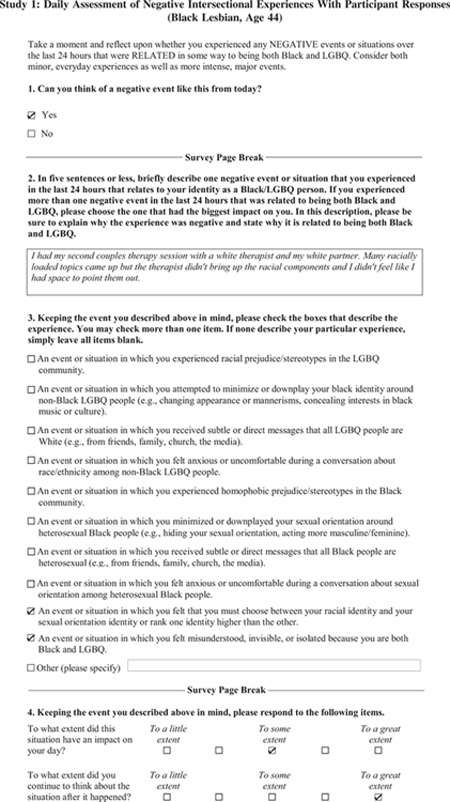

Our three-step approach to the daily assessment of intersectional experiences (Appendix A) was inspired by the previous experience sampling work of one of the present authors; this work assessed positive and negative experiences related to one’s sexual identity (Mohr & Sarno, 2016). This procedure had the ability to generate quantitative and qualitative data and could be easily extended to the study of intersectional experiences. Thus, we opted to modify its overarching methodology used to identify a type of experience related to only one system of inequality (i.e., sexual orientation) to instead capture intersectional experiences. Although the three steps described below (and presented within Appendix A) focus on negative intersectional experiences, we assessed positive intersectional experiences in an identical manner.

Step 1. Assess the (potential) presence of an intersectional event.

Participants were first asked a question suitable to capture intersectional experiences—e.g., whether they “experienced any negative events or situations over the last 24 hours that were related in some way to being both [Black or Muslim] and LGBQ.” We further clarified that this could include “both minor, everyday experiences as well as more intense, major events.” Four key considerations led us to ask about intersectional experiences in this manner.

First, we sought to maintain brevity in our questioning. Because experience sampling surveys already ask for ongoing participant engagement, it is recommended that researchers conducting such studies consider ways to minimize additional burden to participants (e.g., by reducing survey length; Plano Clark et al., 2015). Second, not all negative experiences occurring within the lives of Black or Muslim sexual minority people are intersectional or even power-related. Thus, we intentionally avoided focusing on multiple identifications as a proxy for intersectional experiences, and instead focused on “events and situations” occurring because of one’s combination of social identities. We believed that these social groups were so deeply embedded within stratified systems on inequality that participants would be hard-pressed to identify experiences occurring as a result of their specific social location that were completely unrelated to power. Thus, we expected that—even without mentioning manifestations of power by name (e.g., racism, Islamophobia, homophobia, biphobia)—our daily assessment would (a) overwhelmingly generate experiences that related to inequality and (b) occasionally generate experiences with no conceivable relationship to inequality, which would be readily identifiable.

Third, to further improve our ability to accurately assess intersectional experiences, we worked to minimize jargon in this item. Academic framings of intersectionality—though valuable in many contexts—often include terminology that may be unfamiliar or alienating to participants within a brief survey. Further, the nuance with which an individual can appraise and articulate whether and how their perceived group memberships relate to their treatment in the world (e.g., social identity development, critical consciousness) is understood to be a developmental issue, often acquired over time (Quintana & Segura-Herrera, 2003; Thomas et al., 2014). Thus, rather than using the term intersectionality or other academic language within our survey (e.g., co-construction, structural forces, vectors of oppression), we opted for simple, straightforward language—even if it risked capturing responses that ultimately did not meet our definition of intersectional experiences. Clear and concise language was also essential due to the online nature of our studies, as respondents could not ask clarifying questions.

Potential modifications.

Researchers are encouraged to alter this question to fit the unique needs and foci of their study. Most obviously, this question could be asked at a different frequency (e.g., every eight hours, every 72 hours) or using an event-contingent approach (e.g., whenever an intersectional experience occurs, whenever one attends their place of worship). One might also opt to focus on different axes of oppression (e.g., race and gender) or even focus the question on areas of privilege (e.g., “have you experienced any events or situations over the last 24 hours that you feel were shaped by your being both White and male?”).

Second, for researchers solely interested in the negative ramifications of intersectional dynamics, the question about positive intersectional experiences can be eliminated. Others may wish to focus exclusively on positive experiences, such as to highlight potential targets for interventions that harness resources to build resilience. Even if both items are retained, they are not exhaustive, as not all intersectional events can be easily dichotomized into positive or negative events (e.g., experiences that contain both challenging and pleasurable components). To remedy this, researchers may (a) add a third question, in which participants can endorse events that do not easily fit within this dichotomy or (b) choose to ask a single question to elicit intersectional experiences, without any reference to the valence of the event. If this latter option is adopted, participants will be limited to reporting a single intersectional experience each day. Further, unless researchers explicitly state that all experiences—positive, negative, or otherwise—are acceptable, participants may assume that the item refers to negative experiences.

Finally, some researchers may understandably not wish to collect descriptions of just any type of same-day experience that occurred because one is LGBQ and Muslim and/or Black. For example, researchers interested in multiple minority stress may broaden this question to assess experiences related to “being Muslim or LGBQ” (as opposed to “Muslim and LGBQ”). Conversely, some researchers may want to narrow the focus of our item. For example, in response to calls for intersectionality research that more explicitly centralizes power and structural inequalities (Bauer, 2014; Moradi & Grzanka, 2017) one could conceivably alter the item to inquire about (a) events within one or more institutional settings (e.g., healthcare system, educational institution, criminal justice system) over the last 24 hours or (b) experiences related to “both racism and Islamophobia” (rather than experiences related to “being both Muslim and LGBQ”). Researchers should carefully consider whether it is preferable to circumscribe the question or to simply direct their focus toward structural factors during data interpretation.

Step 2. Elicit a brief qualitative description of the event.

If participants indicated having experienced an event, we then requested they provide a short description (five or fewer sentences) that specified why they perceived it as negative and how it related to their being both [Black or Muslim] and LGBQ. To reduce survey burden, if multiple negative intersectional experiences had occurred within the previous 24 hours, we asked participants to only detail the event that had most affected them. Although there are potential benefits to asking about multiple experiences (e.g., more robust data, the ability to study how multiple experiences of intersectional stress relate to study outcomes), for us these advantages did not outweigh the expected costs (e.g., higher potential for study dropout given the increased effort required for each daily survey). Asking participants to choose a single event may also help to safeguard against the unintentional collection of experiences of multiple minority stress. Specifically, we thought that by asking participants to identify a single experience defined by multiple power-laden aspects of social identity, they were more likely to offer experiences that were co-constructed by the hierarchical systems of inequality (e.g., religion, sexual orientation), rather than furnishing experiences of multiple minority stress (such as reporting that Islamophobia and homophobia occurred at different times within the last 24 hours).

Potential modifications.

Although we limited participants to describing only their most impactful positive experience and negative experience each day, other researchers might opt to assess all relevant experiences. Those interested in the potentially compounding effect of having multiple intersectional experiences within a given day might even consider departing from the regimen of once-daily sampling. Mobile technologies now allow researchers to gather audio, geospatial, and physiological data throughout the day—be it continuously, at random moments, or in response to triggers (e.g., a certain physiological state or location, initiation of an experience sampling survey by the participant). Further, if researchers opt to modify the Step 1 item we presented earlier, they should consider how those alterations might inform what details they ask participants to include in their narrative descriptions when responding to Step 2.

Step 3. Probe for key information about the event to make implicit details explicit.

Once participants had explained their event, we listed several general types of negative intersectional experiences (e.g., an event or situation in which you experienced homophobic prejudice/stereotypes in the [Black or Muslim] community), and asked participants to select the checkbox next to any or all labels that matched their description. Lastly, respondents rated the impact of the event in one of two ways. In Study 1, Black LGBQ participants were asked how much the event had impacted them and how much they had ruminated about the event, in each case using a 5-point Likert scale. In Study 2, we replaced these items with a sliding bar (−100 to 100) where participants could rate the supportiveness (or unsupportiveness) of each event for their Muslim identity, LGBQ identity, racial identity, gender identity, and if specified, another type of social identity (e.g., ability, socioeconomic status).

Potential modifications.

As demonstrated by the somewhat different approaches in Study 1 and Study 2, the focus of the probes can be altered to align with the aims of one’s study. For example, researchers interested in multiple minority stress could include checkboxes allowing participants to communicate whether the event related to one stigmatized status, to another stigmatized status, or to both. Other modifications concern how one might pair this information with additional data collection components. For example, researchers could monitor survey responses each day and reach out to participants with probing questions about experiences (e.g., through text messages). Events could be targeted for follow-up interviews randomly, based on the checkbox selections, or in certain interpersonal situations or contexts (e.g., interactions with in-group members, experiences in clinical settings). Whatever the modifications, the essence of this step should remain intact: to gather key information about the event to increase the likelihood that one can interpret it accurately, evaluate whether it adheres to one’s variable conceptualization, and understand how the participant experiences the event.

To expand the possibilities for studying precursors and consequences of intersectional experiences, contextual data could be gathered throughout the day rather than at a single point in the evening. A simple application of this approach might be to have participants complete a brief survey on their smartphones to indicate the occurrence of an intersectional event, as well as to provide basic information about the nature of the experience and their immediate response and affective state. This survey could then trigger one or more surveys later in the day to track the evolving impact of the event, including the person’s responses (e.g., coping behavior, affect). Integrating this into the present study design would allow researchers to investigate questions about direction of influence, such as whether intersectional events precede upticks in anxiety within the days they occur (compared to the days they do not occur).

Inspection of Data

Bowleg (2008) highlighted the complexities of determining what qualifies as an intersectional narrative account, given the often implicit nature of intersectional dynamics within qualitative data. In reflecting on the qualitative work of herself and her colleagues, she noted that at times participants “did not articulate the experience of intersectionality explicitly,” even when intersectional dynamics might have been at play (Bowleg, 2008, p. 318). To address the fact that these dynamics might remain hidden and unnamed within qualitative descriptions, we adopted a rating strategy: three raters familiar with intersectional theory as applied to LGBQ racial and religious minorities rated each participant-identified intersectional experience. Upon reading each potential intersectional event, raters considered whether it could—by any interpretation— legitimately represent a moment co-constructed by race and sexual orientation (Study 1) or religion and sexual orientation (Study 2). In the hope of retaining implicit intersectional data, they then used a fully anchored 5-point scale of 0 (very certain it is not intersectional, no substantial doubts) to 4 (very certain it is intersectional, no substantial doubts) to evaluate each potential intersectional experience.

This inspection of respondents’ narrative accounts revealed that some events did not, as described, correspond with our studies’ definition of intersectional experiences. For example, events that were not conceivably shaped by power, experiences seemingly shaped solely by a single system of power (e.g., experiences of homophobia), and situations attributable to axes of power that were not the foci of the studies (e.g., race and gender) were—in lieu of additional information—insufficient for inclusion. When event descriptions encompassed the two requisite systems of inequality, raters considered whether it was conceivable that they co-constructed an intersectional experience. For example, in Study 2, an experience of Islamophobia in the morning and homophobia in the afternoon would not qualify as intersectional—that is, unless the participant also discussed how these distinct, asynchronous events joined to produce their experience (e.g., feeling isolated and misunderstood in the evening as a result of facing both Islamophobia and homophobia in a single day). Inter-rater reliabilities, estimated with the intraclass correlation coefficient, were deemed suitable for positive and negative intersectional experiences within both studies. The principal investigators reviewed all description ratings for fidelity to the framework of intersectionality and to consider whether the rating strategy meaningfully addressed the potential for implicit intersectional data. Alternatively, researchers may opt to resolve discrepancies between raters through consensus-building discussions.

We aimed to embrace participants’ subjective understanding of their own experience and thus, adopted an intentionally low threshold for which events to include in our study. If any of our three raters thought it in any way possible that the narrative description might reflect our definition of intersectional experiences, it was retained. By this method, only a small number of reported positive and negative events were recoded as non-intersectional events. In one of our studies, to examine whether quantitative results were influenced by our inclusive approach, we tested hypotheses with a generous, moderate, and conservative rating score cut-off to determine which experiences were to be counted as intersectional. The direction and significance of quantitative study results were unchanged, and thus we maintained the most generous cut-off (i.e., those with an average rater score of 0 were not coded as intersectional events, while all others were considered qualifying intersectional experiences for our analyses).

Discussion and Illustration of Mixed Methods Data Analytic Opportunities

Below, we present select qualitative and quantitative data examples from our two studies, including several of the 557 intersectional experience descriptions furnished across both. Here again, our presentation of data is not intended to provide a complete picture of our studies’ results, but rather to showcase the unique data and analytic opportunities afforded by our mixed methods experience sampling design. Where relevant, we offer key insights and lessons that may aid researchers in applying, adapting, and improving upon our methodology.

Illustration 1. Understanding How (and How Often) Intersectional Experiences Manifest

Our approach can easily generate descriptive information about the frequency and valence of intersectional experiences. Black LGBQ participants in Study 1 (n = 131) provided 849 days of data in total, with positive intersectional experiences reported on 31.0% of study days and negative intersectional experiences on 11.4% of study days; Muslim LGBQ participants in Study 2 (n = 91) contributed 570 days of data, identifying positive and negative intersectional events on 20.2% and 14.4% of study days, respectively. One can easily glean similarities between the event frequencies (e.g., the number of days featuring a positive intersectional experience was greater than the number of days featuring a negative intersectional experience), as well as differences (e.g., compared to the Black LGBQ sample, the Muslim LGBQ sample reported positive intersectional experiences less frequently). Such findings can inform theories and guide quantitative research aiming to understand health differences between intersectional subgroups.

These descriptive statistics illuminate how often intersectional experiences occur, but tell us little about how they manifest and how these events are appraised by LGBQ racial and religious minorities. One primary benefit for researchers of intersectionality who collect qualitative descriptions alongside quantitative data is the ability to humanize quantitative study results using participants’ own words. We only needed information about whether an intersectional experience occurred (i.e., response item 1 within Appendix A) to quantitatively test our hypotheses about intersectional experiences, but this binary variable could not capture the voices of our Black and Muslim LGBQ participants or the nuance in their daily lives. Consider the difference between merely knowing whether an intersectional event occurred versus receiving a vivid description of the event in the participant’s own words, as below:

Appointment with doctor started with me having a long wait in a cramped receptionist room with all Black patients. While waiting, there was a TV program about marriage equity that prompted one patient to make homophobic statement [sic] about same-gender marriages and relationships in general […].

–Black bisexual man, age 71

I went to a Palestinian Solidarity Committee and a pretty well known poet came and performed poetry to us about Palestinian solidarity, faith and queerness. The reason why it was positive in both aspects is because, in a lot of ways, I relate my Muslim identity to my Palestinian identity […] so just being in a room full of people who I know would accept my queerness along with my Muslim identity is always comforting. Hearing a queer Palestinian poet perform also made me really happy. I know a some [sic] queer Arabs and a few queer muslims but I know even less queer Palestinians so one being the focus of our meeting this week was just so great.

–Muslim bisexual woman, age 21

Such details not only center and amplify the voices of oppressed group members, but also help to fill gaps in knowledge about the complex ways and varied contexts in which intersectional experiences manifest among LGBQ racial and religious minorities.

These qualitative data also offer a number of analytical opportunities. For example, Castro and colleagues (2010) described a concurrent triangulation design in which qualitative data are coded and dimensionalized; in turn, these dimensions are used in quantitative analyses to predict outcomes of interest. Such an approach could be implemented in experience sampling research by using qualitative methods to identify dimensions along which intersectional experiences vary (e.g., age, gender identity, sexual orientation outness). Further, the qualitative events from our studies could be re-coded into specific subcategories of intersectional experiences (e.g., intersectional stereotypes, intra-community stigma, intersectional invisibility). This coding process can create new variables that might be analyzed in a number of ways, including regression or multiple regression analyses, to understand the overall or particular association between distinct types of intersectional events and aspects of social identity adjustment (e.g., religious/sexual identity conflict) or mental health (e.g., affect, rumination).

As previously discussed, many quantitative studies require participants to recall and assess the impact of stigma-related experiences that occurred long ago. In such cases, older and more minor events may be forgotten or distorted over time (Bolger et al., 2003; Shiffman et al., 2008). Our experience sampling study design helped to address this, likely garnering greater detail by asking participants to only describe experiences from the prior 24 hours. Also, we are confident that this approach better captured minor everyday experiences (e.g., subtle microaggressions, small victories) that might otherwise have been forgotten, despite their contribution to the accumulation or amelioration of stress. For example, the below narratives describe fleeting experiences that might be subject to retrospective memory bias.

At a Muslim service today…a guy that I suspect is not comfortable with the fact that I’m bisexual…did not say salaam to me & seemed to avoid eye contact.

–Muslim bisexual woman, age 25

I had several really positive text interactions today with friends who are both Black and LGBT. In them we were able to connect by making jokes with one another which were mostly funny given our social positioning as members of intersecting groups. Something that simple is usually enough to make a good day just slightly better.

–Black lesbian, age 28

If researchers truly want to understand the full range of ways intersectional dynamics manifest in participants’ lives—including in events that, though impactful, might not be easily or accurately recalled weeks or months later—experience sampling methods such as these may be helpful.

Illustration 2. Assessing the Impact of Intersectional Experiences

Contemporary stigma researchers argue that internal stress reactions to a particular situation may vary substantially between individuals (Meyer, 2003). In line with this understanding, our studies adopted a subjective stance on the stress (or pleasure) triggered by a given intersectional experience. This viewpoint suggests that assessing whether one perceives an event to be discriminatory is of greater utility than objective measures of discrimination in the prediction of stress and health risk (Meyer, 2003). For example, recall the intersectional event presented earlier, in which the participant heard a homophobic comment while waiting for a doctor’s appointment. The participant’s full description was as follows:

Appointment with doctor started with me having a long wait in a cramped receptionist room with all Black patients. While waiting, there was a TV program about marriage equity that prompted one patient to make homophobic statement [sic] about same-gender marriages and relationships in general. I opened my mouth to counter her comments, but several persons beat me to it and read her up one side and down the other. The discussion continued after the homophobic person went in to see the doctor and I was able to participate in the discussion with lots of affirmation about marriage equity.

–Black bisexual man, age 71

Although this participant appraised the experience as positive, one could imagine another Black LGBQ individual having a different reaction to this complex event, perhaps feeling disappointed or angry at the homophobic statements rather than affirmed by the inclusive views of others in the waiting room. We chose to honor the subjective standpoints of our study participants, unless we perceived—based on the aforementioned rating protocol—that they had likely misunderstood the question. Other researchers may handle ambiguous data differently, as such decisions are highly dependent upon a researcher’s qualitative paradigm (Bowleg, 2008; Morrow, 2007).

By collecting quantitative, day-to-day data on intersectional events and psychological well-being, we could use multilevel regression modeling to assess whether intersectional experiences reliably ebbed and flowed with other psychosocial factors (e.g., positive and negative affect). Our mixed methods approach allowed us to examine such relations qualitatively as well. For example, by asking participants to explain why reported intersectional experiences were negative or positive, we generated responses demonstrating how participants perceived these events to influence their mood (emphasis added).

A Muslim friend of mine mentioned that his mother (my mom’s best friend) asked him if my partner and I are dating. I’ve been really concerned that this means my mom is also suspicious, and I am completely paranoid about it. My mom texted me telling me that she loves me and I burst into tears because I’m not ready to be outed to my family. I think my parents will reject my being queer because they consider that haraam.

–Muslim queer woman, age 22

Saw an adult film involving a masculine black woman, as well as another masculine woman of color. I have been searching for films like these for a while now, so I was very happy I found it. The movie was shot in a way that was affirming and validating of sex acts involving Black Queer Women and did not seem objectifying at all.

–Black lesbian, age 23

This approach balanced our desire to qualitatively capture the breadth, complexity, and dynamic nature of intersectional experiences with our plan to quantitatively analyze theorized links between intersectional events and health. Our method also allows for the possibility of presenting qualitative and quantitative data at the level of the individual person (Plano Clark et al., 2015).

Illustration 3. Capturing a Dynamic, Context-Dependent Phenomenon

The present experience sampling mixed methods approach let us identify how regularly intersectional experiences occur and detect how various social identities, experiences, and outcomes interrelate across time and context. In both studies, we reviewed the qualitative data generated by our repeated measures to examine the fluctuations in whether and how intersectional forces manifested in our participants’ lives. There were many instances in which a participant’s experience of their intersectional status shifted daily during the weeklong study period, including for the below 24-year-old Muslim gay male participant, who on occasion had both positive and negative intersectional events within the same 24-hour period.

[Day 1] Watched a YouTube video about decolonizing queerness and faith that made me feel validated that queerness is not only viewed negatively in religion and that my faith is a reflection of my own feelings, not something others get to dictate for me.

(Positive intersectional experience)

[Day 2] Had a therapy session with my LGBT therapist about family after spending Thanksgiving with them. (Positive intersectional experience); Went on a date with a white non-Muslim gay guy and felt that I could not relate to him mainly because our experiences with race and sexuality were so different.

(Negative intersectional experience)

[Day 3] Spent time with a queer Muslim friend after attending an on-campus talk about encouraging Muslims to support secular values and human rights. (Positive intersectional experience); Went to a talk that at times seemed to imply that being LGBT is unthinkable in mainstream dominant Muslim thought.

(Negative intersectional experience)

[Day 5] Had a phone conversation with a good friend who is non-queer non-Muslim about staying empowered in my identity as a queer, Muslim, South Asian American.

(Positive intersectional experience)

[Day 6] Texted a straight desi friend who assumes I’m straight and asked me if I’ve “found the lucky gal yet.” I considered coming out to her but realized she would probably just act more surprised than supportive and require me to do emotional labor.

(Negative intersectional experience)

The quantitative data provided a different basis for considering questions about stability and change in intersectional experiences. For example, among the Black LGBQ participants, the intraclass correlation coefficient for identity conflict (i.e., one’s internal sense of compatibility between their racial and sexual identities) demonstrated that approximately 55% of the variability in this construct was due to stable differences between participants. The remaining 45% of the variability was due to fluctuations within participants (and error). This combination of stability and fluctuation was also seen in the relation between negative intersectional experiences and identity conflict. At the between-person level of analysis, we found that the participants who reported the most negative intersectional experiences over the course of the study also reported the highest levels of daily identity conflict. Within persons, we found that participants’ identity conflict levels were highest on days they reported a negative intersectional experience. Taken together, these results provide evidence of simultaneous stable and dynamic intersectional processes linking elements of a person’s environment with their identity conflict.

In addition to assessing the stability of intersectional experiences, we sought to better understand the range of these experiences, including the contexts in which they arose. The qualitative component of our mixed methods design collected descriptions of daily intersectional events, providing us with insight into the valence, context, and relational components of participants’ experiences. While we asked about intersectional experiences in a broad and non-context-specific manner, the sheer number of responses allowed for a closer examination of those linked to specific relationships or environments. As represented in the below qualitative descriptions, a number of responses related to intersectional stress or affirmation sparked by media depictions of LGBQ racial and religious minorities.

I was a bit upset and disturb [sic] after watching a show in which a gay person of color was unexpectedly killed. It brought to mind how often those in our community who are also poc are killed, and if I’ll ever be killed for being a black, gay, woman (something I think about from time to time).

–Black lesbian, age 22

[…] today I was watching a TV show (the bold type), which features a lesbian couple— one is Muslim and one is not, but is a person of color, and it was just nice to see a character like me on TV.

–Muslim lesbian, age 19

In response to our broad question about intersectional events, participants provided examples occurring within expected relationships (e.g., family, friends, coworkers, strangers), interpersonal environments (e.g., home, work, virtual spaces), and institutional contexts (e.g., education, healthcare), but also within unexpected domains. For example, we were intrigued to review a number of qualitative descriptions of intersectional events that were not interpersonal at all, involving no direct interaction with others.

I experienced loneliness and boredom because I live in a community with limited positive activities for both black/LGBT people. Most activities are centered around club life but those that do not are far and few in between […].

– Black lesbian, age 53

I had a dream last night that my parents found out about my being a lesbian and they were ok with it and that was somewhat upsetting to me when I woke up in the morning because I was reminded that that was something that wouldn’t happen.

–Muslim lesbian, age 18

Illustration 4. Making Intersectionality Less Elusive to Participants and Researchers

As previously discussed, individuals do not necessarily view their social world through an intersectional lens (Bowleg, 2008). Although some participants in our studies seemed familiar with intersectionality—using the term within their responses—many respondents undoubtedly were unfamiliar with the framework. We do believe that due to the structure of our assessment, many of our participants were able to effectively communicate intersectional experiences without having any formal or colloquial education about intersectionality. As discussed in our methodological overview, we intentionally avoided using jargon in our questions in an attempt to make our assessments of intersectionality as understandable as possible. Additionally, our asking participants about these experiences each day likely made respondents more watchful for intersectional dynamics in their lives. Furthermore, our decision to have participants categorize their intersectional events under one or more broad descriptions may have helped educate them on the concept of intersectionality and how it might appear in their lives, effectively providing them a framework—or sharpening their existing framework—to think in a manner that is consistent with intersectionality. Although we controlled for day of study participation at the within-person level to minimize the effect of time-related linear trends, if such changes are of interest to the researcher, the present study design makes it possible for scholars to assess whether intersectional event reports increase in frequency or quality over the course of the study.

Although the qualitative question in this study (i.e., response item 2 within Appendix A) is well suited to generating a range of responses, its broad nature is vulnerable to capturing answers that are vague or that do not—on the surface—seem to qualify as intersectional experiences. In such cases, the qualitative analysts may struggle to determine whether certain reported events are indeed intersectional. For example, a 27-year-old Muslim woman in Study 2 shared, “The person I discussed wearing hijab with today was pretty supportive and appropriately questioning about what it would mean for me.” This event description—at first glance—is not clearly intersectional in nature. However, from this information alone, the analyst cannot determine whether this response resulted from problems related to (a) research assessment (e.g., the participant did not understand the construct), (b) participant motivation (e.g., the participant did not attempt to carefully consider and thoroughly answer the question), (c) communication (e.g., the participant struggled to adequately describe a legitimately intersectional experience), or (d) interpretation (e.g., the analyst struggled to detect implicit intersectional content in the description provided).

It is precisely because of the challenges in capturing and analyzing intersectional events that we used a combination of quantitative and qualitative assessments, providing multiple data sources to verify each participant’s report of an intersectional experience. After the first step—in which respondents reported an experience related to both their sexual orientation and racial or religious identity—they then described the experience, indicating why it was positive or negative and how it was co-constructed. Participants with an understanding of intersectionality might have been best suited to provide such descriptions. The third question, however, afforded participants the opportunity to label their responses using checkboxes, which might have aided participants less familiar with intersectionality in communicating their experiences; this in turn helped the analysts who later reviewed their responses. By gathering data in three ways, our mixed methods approach allowed us to use data from each step to corroborate the others.

Our checkboxes (i.e., response item 3 within Appendix A), which listed broad intersectional event categories, helped us interpret especially undetailed or unclear participant responses. In the example provided above, the respondent used the checkboxes to clarify why the discussion around wearing the hijab was intersectional. Specifically, this participant selected two of the provided checkboxes to indicate that the experience was: 1) An event or situation in which [she] experienced acceptance as a Muslim person within the LGBTQ community; and 2) An event or situation in which [she] felt included, affirmed, or empowered during a conversation about religion/Islam among non-Muslim LGBTQ people. These selections provided information the analysts did not have previously: the supportive individual was a member of the LGBTQ community. Across our studies, many intersectional event descriptions might have been deemed non-intersectional and eliminated from our analysis had we not collected this information. This form of bi-directional corroboration—in which qualitative data can support or call into question the validity of quantitative data and quantitative data can clarify vague or atypical qualitative data—is one reason mixed methods research is well suited to advance intersectionality research: it allows for more precise identification of what is (and is not) intersectional.

Limitations and Future Applications

We believe our approach to studying intersectional dimensions of everyday experience offers some exciting possibilities for future research, and can be extended in ways that both increase its applicability to a variety of research goals and address some of its limitations. Despite its many advantages, the microlongitudinal nature of experience sampling data collection has drawbacks. Although daily event narratives can be rich and informative, they are generally far briefer than traditional qualitative accounts, considering the inherently intensive nature of responding to a daily survey. As a result, the narrative accounts generated by experience sampling methods may lack the depth characteristic of more common forms of qualitative data collection (e.g., interviews, focus groups). Also, although same-day assessment may reduce retrospective memory bias, it simultaneously reduces the time participants have to make meaning of their experiences. One potentially useful refinement of our approach would be to use different follow-up questions to clarify the nature of the experiences reported by participants and to deepen insight into the participant’s understanding of those experiences. Such questions could be built into a survey to encourage the participant to relay information that would help researchers determine what is intersectional about the experience (e.g., the social positions of the people involved in an experience). Intersectionality researchers interested in assessing meaning-making processes may consider modifying the method to allow for follow-up interviews. For example, using a retrospective design (Plano Clark et al., 2015), quantitative analyses of daily data could be used to select interviewees who are exemplars different study subgroups (Hanson et al., 2005) based on variables of interest (e.g., rejection sensitivity, outness, identity conflict). Alternatively, interview data collected from all participants at the end of the study could be analyzed using qualitative methods, used to inform the quantitative data, or fully integrated with the quantitative data to reach a fuller understanding of intersectional experiences (Castro et al., 2010).

Perhaps most obvious is the potential for studying other populations’ intersectional experiences. In particular, further research is warranted to understand how this method fairs when used to capture daily experiences related to more than two systems of oppression. Also, in line with calls for research that examines privilege—in addition to oppression—through an intersectional framework (Bauer, 2014; Moradi & Grzanka, 2017), future investigations should explore whether this method can advance research on intersectional manifestations of privilege. Such research could also investigate how positions of oppression and privilege may co-construct distinct experiences (e.g., identity conflict among LGBQ Christians; gender role threat among cisgender Asian men). This approach could additionally be used to study differences in the frequency and nature of experiences within a population—for example, future studies could probe the gendered or developmental aspects of intersectional stress (e.g., comparing the experiences reported by female, male, and nonbinary participants; examining differences across developmental age cohorts). Similarly, our approach could be applied to specific settings, aiding researchers interested in understanding intersectional dynamics and disparities within systems (e.g., healthcare, education, criminal justice) or the climate within particular organizations.

The method described involved sampling once per day, which has both benefits and drawbacks. On the positive side, this approach allowed us to meaningfully assess within-person links among intersectional experiences, identity conflict, and daily well-being. Moreover, the survey administration minimized disruption to participants’ lives by allowing them to provide data once per evening at their convenience. That said, this approach also carries limitations, the most obvious being that participants were not provided a space to describe multiple positive or multiple negative experiences in a given day. This in turn precluded investigating intriguing questions about (a) the frequency of intersectional experiences within a day, (b) within-day interplay among experiences and facets of social identity and well-being, and (c) cumulative and interactive effects of intersectional experiences on daily functioning. As described previously, smartphones could allow for collection of data on multiple intersectional experiences per day by having participants complete short phone-based surveys each time an event occurred.

As with most research on intersectionality in psychology, our approach focuses on experiences that participants are aware of and are willing to report. Counseling psychology researchers have highlighted the limitations of using such self-report approaches as definitive evidence of the links between constructs (Polkinghorne, 2005). Accordingly, our method is unlikely to capture all participant experiences that are shaped by multiple systems of power. In some cases, determining that an experience is intersectional may require information that a participant does not possess. For example, a particular challenging situation may have originated from structural factors that are not readily apparent (e.g., a classified directive given to a city’s police force to profile citizens based on race and gender). Similarly, it is not always possible for participants to infer others’ motivations and attitudes, even though such factors can contribute to intersectional experiences. Two participants may also appraise the same event differently due to individual differences—including their level of stigma consciousness, endorsement of ideologies that legitimize social inequity, and understanding of the concept of intersectionality itself.