Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused organizational crises leading to shutdowns, mergers, downsizing or restructuring to minimize survival costs. In such organizational crises, employees tend to experience a loss or lack of resources, and they are more likely to engage in knowledge hiding to maintain their resources and competitive advantage. Knowledge hiding has often caused significant adverse consequences, and the research on knowledge hiding is limited. Drawing upon the Conservation of Resources and Transformational Leadership theories, a conceptual framework was developed to examine knowledge hiding behavior and its antecedents and consequences. We collected data from 281 Vietnamese employees working during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our results show that role conflict, job insecurity, and cynicism positively impact knowledge hiding behavior. Knowledge hiding behavior negatively affects job performance and mediates the antecedents of knowledge hiding on job performance. Transformational leadership moderated the impact of role conflict on knowledge hiding.

Keywords: Knowledge hiding, Transformational leadership, Cynicism, Role conflict, Job insecurity, Job performance, Vietnam, Covid-19

1. Introduction

The last three decades have seen several significant crises that have affected the attitudes and behaviours of employees at work (Budhwar and Cumming, 2020, Collings et al., 2021, Malik et al., 2019). The COVID-19 pandemic has been one of the biggest crises in human history, and it may take years to recover from its impacts (Ozili & Arun, 2020). Many organizations have experienced organizational crises because they had to shut down, merge, downsize or restructure to minimize costs to survive the pandemic (Malik, 2013, Malik, 2018, Ozili and Arun, 2020). Organizational crises can create enduring employee role conflict, job insecurity, and cynicism, leading to knowledge hiding (König et al., 2020). Employees may need to carry out more tasks, which they may feel they cannot complete because of the lack of information and capability, leading to low job engagement and unwillingness to share knowledge with others. Employees are unsure about job security; therefore, they keep the knowledge to maintain their competitive advantage (Aarabi et al., 2013). Such an environment can lead to employees being cynical about their workplace, which leads to several adverse consequences, including knowledge hiding behaviors by employees.

Knowledge hiding is known to cause significant negative consequences (Huo et al., 2016, Jiang et al., 2019, Ellmer and Reichel, 2021). For instance, in 2018, the losses associated with knowledge hiding behavior were reported to cost American organizations up to US$ 47 million in productivity (Panopto, 2018). Panopto (2018) notes that in 2018, American workers wasted approximately 5.3 h every week because they need to wait for their co-workers to share existing information or knowledge. That wasted time slows down organizational creativity and development, leading to several missed opportunities, lack of collaboration among employees and non-compliance of employees to work norms (Kwahk and Park, 2016, Hickland et al., 2020). Although organizations often make significant efforts to encourage employees to share knowledge and voice concerns, many employees do not want to share knowledge with others and choose to hide it deliberately (Prouska & Kapsale, 2021). Still, others share knowledge based on their attributions towards pay secrecy policies (Montag‐Smit & Smit, 2020). Connelly et al. (2012) point out that knowledge hiding does not mean a lack of knowledge; instead, employees may intently withhold or conceal knowledge that has been requested by their co-workers (Connelly et al., 2012). That leads to the need to examine the antecedents of knowledge hiding behaviour. Despite the importance of knowledge hiding, research on the topic is somewhat limited. As knowledge hiding occurs in the context of interactions between two or more co-workers, it is generally governed by an implicit and sometimes an explicit social exchange (Blau, 1964). Knowledge hiding is low in contexts where there is a norm for reciprocity of social exchange between co-workers (Černe et al., 2014). However, in times of a major global crisis, such as the COVID-19 crisis, the potential economic loss of resources and livelihood can trigger a very different set of agentic resources (Malik & Sanders, 2021) and drivers for employees’ knowledge hiding behaviors. Knowledge hiding in such contexts can be viewed as selfish conservation of resources (Hobfoll, 1989) by employees to circumvent any adverse effects of their resource sharing, especially in times of a crisis, as employees tend to retain their threatened resources (Riaz, Xu & Hussain, 2019). Organizations need to examine the antecedents of knowledge hiding to prevent it and investigate its consequences to understand its negative impact. Moreover, only very few studies discuss the antecedents of knowledge hiding in an organizational crisis context. Therefore, investigating the antecedents and consequences of knowledge hiding in an organizational crisis will provide valuable insights to understand the dynamics core to knowledge hiding behavior.

During organizational crises, transformational leadership plays a crucial role in helping organizations overcome difficulties and challenges. Increased attention has been paid to transformational leadership by linking it to employees’ responses (Schmid et al., 2018, Schmid et al., 2019, Pircher Verdorfer, 2019). For instance, Le and Lei (2018) found that transformational leadership positively impacted knowledge sharing behavior. However, transformational leadership may also have a moderating effect on the antecedents of knowledge hiding behavior. Through transformational leadership, employees can be encouraged, inspired, and motivated to innovate, accept changes, take more challenges, and contribute to the organization’s development. Despite the above benefits, little research has been undertaken to understanding how transformational leadership may affect knowledge hiding behaviors of intentionally concealing specific knowledge requested by co-workers. It is important to address this because knowledge hiding is prevalent in organizations and can negatively impact employees’ job performance. To the best of our knowledge, the moderating effects of transformational leadership on the impact of the antecedents of knowledge hiding behavior have not been investigated.

This study’s objectives are twofold: (1) to examine the antecedents and consequences of knowledge hiding behaviors, and (2) to investigate the moderating role of transformational leadership on knowledge hiding behaviors. By addressing these objectives, this study offers novel insights through our recent data and current context that integrates the impact of pandemic and crisis management and online knowledge hiding behaviors, thereby contributing to the knowledge hiding literature by examining its antecedents and consequences during a global crisis affecting nearly all organizations. Furthermore, this research extends our understanding of the underlying mechanisms in which transformational leadership interacts with the antecedents of knowledge hiding behavior by demonstrating the moderating role of transformational leadership. The findings of this study should have useful implications for scholars researching crisis management, transformational leadership and conservation of resources (Bass, 1995, Coleman, 1988, Hobfoll, 1989) and address knowledge hiding behaviors (Connelly et al., 2012) in organizations to manage human resources to prevent the reduction in employee job performance (Saundry, Fisher & Kinsey, 2021).

2. Literature review

Knowledge often refers to information, skills, and experiences acquired through perceiving, discovering, or learning (Kang et al., 2017; Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995). In general, knowledge is often categorized as explicit or tacit (Polanyi, 1962). The former involves the knowledge which can be expressed in a written form, including grammatical rules, policy statements, mathematical expressions, and manuals (Small & Sage, 2005); while the latter refers to the kind of knowledge that is difficult to transfer to other people utilizing writing or verbalizing such as individual skills, ideas, and experiences (Chowdhury, 2005, Hwang, 2012). The transfer of explicit knowledge is more straightforward than implicit knowledge because this type of knowledge is hard (if not impossible) to hide (Chowdhury, 2005, Hwang, 2012). However, Nguyen (2020) estimates that up to ninety per cent of the knowledge in any organization is tacit, which often resides in people’s heads. This knowledge is widely regarded as the most critical organizational resource to maintain organizational competitive advantage (Maravilhas & Martins, 2019). Tacit knowledge is personal, invisible and hard to codify and express (Civi, 2000, Haldin-Herrgard, 2000, Perry-Smith, 2006) and is rooted in action, involvement, and commitment in specific contexts (Nonaka, 1994). In reality, numerous employees tend to make deliberate attempts to hide tacit knowledge in organizations, leading to many negative consequences such as duplication of efforts or reduction in employee job performance (Nguyen, 2020, Beijer et al., 2021). Therefore, there is a need to examine the antecedents of knowledge hiding behavior involving tacit knowledge in organizations.

In the literature on knowledge hiding, several factors are identified as potential predictors of knowledge hiding behavior. For example, as “knowledge is power”, employees hide knowledge because they may want to gain a superior position, desire to do well relative to others, and be positively evaluated. The reasons for knowledge hiding may also stem from the fear of losing market value which is “hardly won” due to significant effort and a long period of training, and the fear of hosting “knowledge parasites” who just want to take advantage of requesting knowledge without putting sufficient effort to acquire themselves. In some circumstances, knowledge hiding aims to avoid the dark side, such as leaking information to competitors. Besides, personality traits and cultural factors may affect knowledge hiding behavior. Those who are not talkative often tend to be introverts in sharing knowledge with co-workers (Arshad & Ismail, 2018). Cultural contexts also may impact employees’ attitudes toward knowledge hiding (Nguyen et al., 2019).

Knowledge hiding has been rarely examined in the context of organizational crisis. Given the complex nature of the phenomenon of knowledge hiding, it is logical to draw on two relevant theoretical frameworks - Conservation of Resources Theory (COR) (Hobfoll, 1989) and Transformational Leadership Theory (TLT) (Bass, 1995) to gain deeper insights into knowledge hiding behavior during organizational crises. The COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989) helps explain why employees hide their essential resource, i.e., knowledge. Employees are motivated to protect the things that they value (Simha et al., 2014). They will endeavor to maintain resources if they perceive a threat against a valued resource (Hobfoll, 1989, Simha et al., 2014). These threats could come from role conflict, job security, or cynicism, often resulting from organizational crises. Organizational crises are often acute, public, and pose onerous threats to an organization and its employees. In organizational crises, employees may be expected to carry more work and greater responsibility, leading to role conflict (Cartwright & Holmes, 2006). In addition, the organizations which are in a crisis may experience mergers, downsizing, and restructuring. Therefore, employees tend to perceive a high level of job insecurity during such times (James et al., 2011). While some may adapt to new situations of organizational crises rapidly, for many, these changes mark a sense of cynicism (Cole et al., 2012).

Our literature review suggests that several core variables that have focused on the COR theory have been extensively researched. These include variables, such as work/family stress (Grandey & Cropanzano, 1999), burnout (Halbesleben, Harvey & Bolino, 2009) and general stress (Halbesleben, 2006). Indeed, Park et al.’s (2009) meta-analysis tested COR its key constructs, such as job control, burnout, autonomy, authority, skill discretion, and decision latitude. Moreover, this research extends the COR research by incorporating other variables that have been identified as potential antecedents of knowledge hiding behaviour, such as personality traits. However, in our paper, we have stressed that knowledge hiding was rarely examined in the literature on organizational crises, which often involves role conflict, job insecurity and cynicism.

During organizational crises, employees often experience pressure on the resources available to them to complete tasks due to role conflict and fear of loss of employment due to a high level of job insecurity and cynicism (Cole et al., 2012). According to the COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989), employees tend to maintain their resources to avoid further losses. When employees have a sense of losing resources due to the threats of role conflict, job insecurity, and cynicism, they are more likely to engage in knowledge hiding behaviors (Zhao et al. 2016). Employees tend to feel more psychologically safe and secure by concealing knowledge because they can retain their resources (Hernaus et al., 2018). Furthermore, employees may be required to do overtime; they may get a pay freeze and pay cuts. These may push employees out of their comfort zones, stir up strong emotions, such as anxiety, panic, and distress and require them to be more productive to save the organization. Thus, to maintain their value and competitive advantage in organizations, employees are more inclined to knowledge hiding to keep unique skills or expertise. Although numerous antecedents of knowledge hiding behavior exist in the knowledge hiding literature, due to the lack of studies in the organizational crisis context, role conflict, job insecurity, and cynicism have been overlooked. However, these factors are crucial to providing a deep understanding of how employees respond to organizational crises.

Furthermore, it is worth noting that not all employees react in the same way during an organizational crisis (Le & Lei, 2018). According to the Transformational Leadership Theory (TLT) (Bass, 1995), employees’ response to resource loss in an organizational crisis is contingent on transformational leadership. Prior studies (e.g., Le & Lei, 2018) have indicated that transformational leadership can function as an accelerator in motivating employees to share knowledge and demotivate knowledge hiding. Inspired by this, our conceptual framework extends the literature by proposing the moderating effects of transformational leadership in examining the relationship between three COR variables and knowledge hiding behaviors. In particular, confronted with an organizational crisis, employees are more inclined to shape their behavioral responses based on their perceptions of transformational leadership shape (Sahu et al., 2018). Thus, leadership becomes crucial to help organizations address difficulties and make employees feel secure (Arnold et al., 2016).

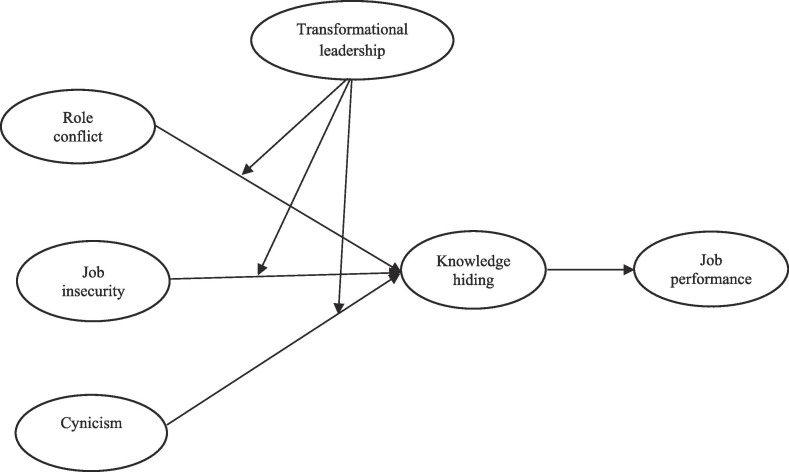

Given the complexity of the phenomenon of knowledge hiding, several scholars have examined this through various theoretical lenses, such as self-determination theory, self-perception theory and social learning and trait theories (Bircham-Connolly et al., 2005). Therefore, an integrated conceptual framework involving knowledge hiding and its antecedents and consequences is developed in this study from the guiding theoretical lenses of the COR and TL theories. The study’s conceptual framework incorporates the aforementioned research objectives, and its hypothesized relationships among variables are presented in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Conceptual framework.

2.1. Hypotheses development

2.1.1. Role conflict and knowledge hiding

In an organizational setting, employees are holders of expert knowledge and skills critical to their and possibly others’ successful completion of tasks and job performance. Role conflict is a common experience in organizations, and it often becomes more intense during organizational crises (De Dreu et al., 2004). Although both managers and employers may be aware of role conflict, it has never been easy to manage it either for employees or managers due to its complexity and dynamism (ALPER et al., 2000, Lefevre et al., 2002). However, role conflict influences working activities and other intentional behaviors, including knowledge hiding. When employees have been told to complete a task where they lack training, role conflict can be predicted to impact knowledge hiding behavior because it affects the employees’ ways of working and reacting (Boz Semerci, 2019). Further, role conflict may be linked with knowledge hiding behaviors because role conflict often impacts the responses of employees, especially in times of a crisis (Semeri, 2019) Semeri (2019) argues that if role conflict in an organization increases, employees may have tendencies to retaliate against others and react negatively, hide knowledge and may find themselves right to do it.

The COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989) can explain knowledge hiding behavior when employees face job conflict. This theory emphasizes reciprocal interdependence, where employees will take action to respond to the organization. Role conflict is regarded as a negative relationship between employees and organizations because employees become confused about their tasks and feel that they cannot complete the task. According to the COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989), negative social interactions, such as perceived role conflict can generate adverse consequences, including knowledge hiding behavior. Role conflict may strengthen the employee’s tendencies to retaliate against others (Schulz-Hardt et al., 2002). Therefore, as role conflict increases, employees react negatively and may withhold knowledge (Boz Semerci, 2019). Thus, it is expected that role conflict may result in knowledge hiding. Aligning with this argument, research (e.g., Schulz-Hardt et al., 2002) shows that employees who perceive role conflict tend to produce less mutually rewarding outcomes. Chen et al. (2011) argue that role conflict tends to provoke interpersonal attacks in attempting to reach an outcome; thus, employees are less likely to exchange useful knowledge with others to maintain a competitive advantage in organizations. Role conflict is generated by different ideas or points of view (Moore, 2000). Role conflict can also lead to interpersonal friction and resentment when employees are not clear about their tasks and think others may be doing their task, or when they may suddenly be given a task that is not in the job description, and they feel they are not competent to finish it (Moore, 2000, Roper and Higgins, 2020). In addition, if employees consider they are being treated unfairly or disrespectfully due to role conflict, they will be more likely to hide their knowledge (Boz Semerci, 2019). Consequently, it might be expected that a high level of role conflict will make employees hide more knowledge from colleagues and vice versa. The above leads to the following hypothesis:

H1: Role conflict among employees in an organization is positively associated with knowledge hiding.

2.1.2. Job insecurity and knowledge hiding

Job insecurity refers to uncertainty surrounding whether employees can keep their job (Bartol et al., 2009, Coupe, 2019). In an era characterized by increasingly volatile, competitive environments and rapid advances in information technology and artificial intelligence, employees tend to have a low level of job security (Bartol et al., 2009, Coupe, 2019). Job insecurity has been reported to affect employees’ knowledge hiding behavior (Ali et al., 2020). Most employees view critical knowledge as a source of power that guarantees continued employment (Ali et al., 2020). Employees experiencing high job insecurity may think they need to keep the knowledge to maintain their competitive advantage (Issac et al., 2020). Their skills and expertise can be highly specialized if few people have these skills and expertise (Issac et al., 2020). During an organizational crisis, the perception of high job insecurity is often common; therefore, employees are more likely to engage in knowledge hiding because they do not want to lose their competitive advantage (Issac & Baral, 2018). They may think that sharing valuable knowledge, skills, or expertise will allow others to replace them in the organization (Issac & Baral, 2018).

Evidence also indicates a negative relationship between job insecurity and knowledge hiding. Job insecurity may significantly impact knowledge hiding behavior because employees are less motivated to share useful knowledge when job security is low (Ali et al., 2020). Previous studies (Domenighetti et al., 2000) indicate that employee cooperation deteriorates as soon as employees worry about job loss. Thus, researchers on this subject, such as Senol (2011), suggest that job insecurity generates low motivation in employees, affecting other motivation levels. In this regard, Şenol’s research (2011) revealed job security as one of the three most important motivators to interact with co-workers, share expertise, and help one another increase job performance. Lack of job security was one possible reason for knowledge hiding and a high turnover of employees. Aarabi et al. (2013) argue that job insecurity functions as an important factor that leads to negative work behaviors such as knowledge hiding, low job creativity and the thought of resigning. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2: Perception of job insecurity of employees in an organization is positively associated with knowledge hiding.

2.1.3. Cynicism and knowledge hiding

Over the last decade, increasing attention has been paid to the importance of employee reactions to organizational change, especially in crises (Stanley et al. 2005). Moreover, employee support for organizational crises has been the key to success during change (Connelly et al., 2019). During an organizational crisis, cynicism is critical to managing as it promotes resistance to organizational change (Jiang et al., 2019). Cynical employees often doubt their value in organizations, and they tend not to share knowledge because they are less likely to think they have sufficient resources and capability to share knowledge that is valuable to others (Cartwright & Holmes, 2006). Cynics are highly likely to engage in knowledge hiding because knowledge hiding may help them protect themselves, thereby maintaining a competitive advantage (Jiang et al., 2019).

Further, cynicism involves suspicious attitudes toward work tasks (Aljawarneh & Atan, 2018). Thus, employees tend not to cooperate with others and do not want to share valuable knowledge. Cynicism may cause employees to behave unethically on the job (Bergström et al., 2014). Cynicism may result in a refusal to share the knowledge requested by others, and the refusal may not stem from a lack of knowledge (Aljawarneh & Atan, 2018).

Cynicism is more likely to prevent employees from spending energy on adaptive work behaviors, leading to knowledge hiding behavior (Bedeian, 2007). Cynical employees tend to feel they have a low work accomplishment level (Bergström et al., 2014). They tend to be more cynical about if their work contributes anything and doubt the significance of their work in their organization (Cartwright & Holmes, 2006). Cynicism can result in adverse outcomes, resulting in negative feelings, including a sense of disappointment toward their work (Cole et al., 2006). Particularly in organizational crises, employees seem to have a high level of cynical opposition to change; thus, they are more inclined to engage in knowledge hiding (Reichers et al., 1997). Besides, cynical employees often do not believe they can receive a fair share of organizational rewards because they may think they are exploited, and the jobs are not worthy of their commitment; therefore, they do not work as hard as they can and do not want to share knowledge with co-workers (Stanley et al. 2005). Cynicism then increases employees’ general attitude that they cannot depend on others to be trustworthy and sincere (Bergström et al., 2014).

Consequently, cynical employees are more inclined to hide their talent, ideas, and knowledge and do not want their co-workers to know them. Cynicism increases a negative feeling towards and distrust of co-workers (Bergström et al., 2014). Without social ties, it is unlikely that employees are willing to share their knowledge (Cartwright & Holmes, 2006). Accordingly, we hypothesize that:

H3: Cynicism of employees in an organization is positively associated with knowledge hiding.

2.2. Knowledge hiding and job performance

Job performance refers to employees’ behavior contributing to the organization’s effectiveness (Singh, 2019). Xiao and Cooke (2018) offer three possible reasons for the possible influence of knowledge hiding on job performance. First, knowledge hiding reduces knowledge availability to facilitate better performance (Xiao & Cooke, 2018). Secondly, employees who hide knowledge tend to have a mindset that sets up a negative, vicious cycle that is not inclined to search for support or support others; therefore, they do not have confidence in the support other colleagues offer (Xiao & Cooke, 2018). The predictable consequence is that performance declines. Finally, knowledge hiding often underestimates that co-workers can identify knowledge hiding by their colleagues when it occurs (Xiao & Cooke, 2018). If knowledge-collectors know that an individual is hiding their knowledge, conflict or trust is very likely to be reduced (Xiao & Cooke, 2018).

According to researchers such as Chen et al. (2006), knowledge hiding often hinders the transfer of knowledge - a systematic process of transmitting, distributing, and disseminating knowledge in a multidimensional context of a person or organization to the person or organization in need. This knowledge transfer process often aims to optimize or exploit existing knowledge among employees to improve job performance due to learning and combining different types of knowledge (Wuryanti & Setiawan, 2017). Therefore, knowledge hiding often reduces employee job performance for three reasons: reduced decision-making, problem-solving, and creativity (Davenport et al., 2016). Employees cannot utilize knowledge together to generate new knowledge (Foss et al., 2015, Lee, 2016). Besides, knowledge hiding often hinders individual tacit knowledge’s transformation into explicit knowledge to create an organizational knowledge pool (Nguyen, 2020). Thus, knowledge hiding reduces innovation capabilities and decreases employee job performance (Wang & Noe, 2010). Knowledge hiding among employees minimizes the use of existing knowledge resources to make innovation (Huang, 2009, Nguyen, 2020, Wang and Noe, 2010) because knowledge hiding results in employees withholding their tacit knowledge. Thus, knowledge hiding has substantial implications for reducing employee job performance (Huang, 2009, Wang and Noe, 2010). Knowledge hiding tends to make employees unable to access co-workers and others’ tacit knowledge across organizational boundaries and prevents them from generating creative solutions (Chen et al., 2011). Accordingly, we hypothesize that:

H4: Knowledge hiding among employees in an organization is negatively associated with job performance.

Organizational crises tend to make employees perceive their role conflict, job insecurity and cynicism at a higher level. Consequently, they are more likely to be in a psychological state of resource depletion (Debus & Unger, 2017). In an organizational crisis, employees tend to face more role conflict, making them feel they lack resources to complete tasks and lose self-confidence (Cartwright & Holmes, 2006). An organizational crisis also tends to increase employees’ feelings about the possibility of losing a job, which often leads to strain and/or stress in employees (James et al., 2011). Besides, cynicism is employees’ feeling which is often found in organizational crises. Employees often feel they are less trusted by their co-workers and that most people in organizations act out of self-interest (Cole et al., 2012). According to the COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989), knowledge hiding behaviour is typically used by employees to respond to role conflict, job insecurity and cynicism to protect their finite resources. Those who are inclined to knowledge hiding to prevent further loss due to facing role conflict, job insecurity and cynicism often do not want to share their valuable skills and expertise with colleagues. However, hiding knowledge is more likely to decrease the knowledge exchange process, and employees cannot learn from each other. Therefore, knowledge hiding behavior often makes the protection of further resource loss respond to role conflict, job insecurity, and cynicism in an organizational crisis become barriers in knowledge exchange, which often negatively impact job performance (Wang & Noe, 2010). In sum, we predict that the impact of role conflict, job insecurity and cynicism on job performance will be mediated by knowledge hiding as proposed in the following hypothesis:

H5: Knowledge hiding mediates the impact of a) role conflict, b) job insecurity, and c) cynicism on job performance

Transformational leadership refers to a leadership style in which employees are encouraged, inspired, and motivated to innovate and create changes (Le and Lei, 2019, Gahan et al., 2021). Transformational leadership often motivates employees to transcend their self-interest for the organization’s benefit (Leong & Fischer, 2010). Under a high level of transformational leadership, employees tend to accept challenges, even in the face of difficulties. In contrast, employees may not pursue solutions in a climate of low transformational leadership (Leong & Fischer, 2010).

Research has shown that transformational leaders’ behaviour may have a moderating effect on the impact of the antecedents of knowledge hiding behavior due to a high level of trust and admiration toward the leader (Le & Lei, 2019). Regarding role conflict, transformational leadership incentivizes employees to contribute to the organization, inspires them to attain common goals, and elicits positive attitudes toward knowledge sharing behavior. Lin (2007) underlines the role of transformational leadership and its possible impact on employee attitudes and behavior toward sharing knowledge and skill with colleagues. Thus, employees tend to have less knowledge hiding behavior with colleagues and help each other address work challenges and difficulties for the organization’s sake (Lin, 2007). Along the same lines, Khan et al. (2019) argue that transformational leaders often leverage employees’ organizational citizenship behavior (OCB), reducing knowledge hiding behavior.

Transformational leadership may moderate the impact of job insecurity on knowledge hiding. Qian et al. (2020) argue that job insecurity is related to employees’ perception; therefore, it is subjective. Given the same working conditions, different employees may perceive different job insecurity levels, partly relying on the transformational leadership approach (Qian et al., 2020). Transformational leadership in organizational crises helps employees commit to the organization and engage in knowledge sharing because transformational leadership involves a set of interrelated behaviors to increase employees’ motivation, morale, and performance (Le & Lei, 2019). Further, the relationship between cynicism and knowledge hiding may be moderated by transformational leadership (Kranabetter & Niessen, 2017). Qian et al. (2020) explain four reasons for such a potential moderating role of transformation leadership. First, a high level of transformational leadership makes employees feel that their needs and concerns are recognized by management. Second, transformational leadership often applies intellectual stimulation to inspire employees to see work difficulties from a new perspective, enabling them to challenge the status quo. Third, transformational leadership often produces favourable conditions for knowledge sharing by increasing mutual trust, motivating employees to interact with colleagues, and support one another (Yin et al., 2019). Fourth, transformational leadership highlights the significance of employee contribution in organizations (Qian et al., 2020). As a result, employees are more likely to be satisfied with and trust their leaders, reducing cynicism’s negative effect on knowledge hiding. Accordingly, we hypothesize that:

H6: Transformational leadership moderates the impact of a) role conflict, b) job insecurity, and c) cynicism on knowledge hiding.

3. Method

3.1. Sample and data collection procedure

This research was conducted in the Vietnamese context via a questionnaire survey. The original questionnaire was in English and translated into Vietnamese through a back-translation approach to ensure accuracy (Brislin, 2016). In particular, two bilingual Vietnamese professionals independently translated the questionnaire from English to Vietnamese. Another bilingual Vietnamese professional translated it back to English and compared it with the original version. A pilot test was conducted on 25 respondents to check the questionnaire’s measures’ validity and reliability. For the primary survey, an anonymous online questionnaire was designed using the Qualtrics platform and distributed via social media platforms, including Facebook and LinkedIn. The target respondents were over 18 years of age, working in Vietnam during the COVID-19 pandemic, and participating in online knowledge sharing in their organizations. After excluding the incomplete responses, 281 usable responses were collected and used for data analysis.

3.2. Measures

This study adopted the construct measures from previous studies. Role conflict was measured using a five-item scale adapted from Moore (2000). An example item of the scale is: “I receive a work task without the manpower to complete it”. Role conflict was measured on a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for role conflict was 0.91. Job insecurity was measured using a seven-item scale developed by Vander Elst et al. (2014). An example of it is: “Chances are I will soon lose my job”. Job insecurity was also measured on a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for job insecurity was 0.97. Cynicism was measured cynicism using an adapted subscale of the Maslach Burnout Inventory–General Survey (Maslach et al., 1996). An example of it is: “Chances are I will soon lose my job”. Cynicism was measured on a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for cynicism was 0.90. Knowledge hiding was measured using Peng’s (2012) four-item scale. An example of it is: “I do not want to transfer personal knowledge and experience to others”. Knowledge hiding was measured on a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for knowledge hiding was 0.89. The job performance scale was adapted from the five-item scale by Chiang and Hsieh (2012). An example of it is: “I fulfilled my job responsibilities”. Job performance was measured on a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for job performance was 0.91. Finally, transformational leadership was measured using a four-item scale adapted from Dai et al. (2013). An example of it is: “The supervisors can understand my situation and give me encouragement and assistance”. Transformational leadership was measured on a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for transformational leadership was 0.78. All variables in this study were reflective because all construct items shared a common theme, had a high level of correlation among each other and were interchangeable. In addition, dropping an item did not alter the conceptual meaning of the construct. Furthermore, although the constructs were not directly measurable, they existed independently of their items. Therefore, following the suggestion of Jarvis et al. (2003), a reflective model should be used.

3.3. Common method variance

A pilot test was conducted to improve and refine the item wordings. In addition, the measurement items for the research constructs were presented in different sections of the questionnaire, and the respondents were informed that their responses would be kept confidential. Regarding ex-post statistical remedies, we followed Podsakoff et al. (2003) recommendations. First, exploratory factor analysis was conducted, which generated six separate factors with no single factor accounting for most of the covariance. Confirmatory factor analysis was than conducted with a poor fit for one-factor model (χ2 = 4500, df = 404, χ2/df = 11.14, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.49; TLI = 0.45; RMSEA = 0.19). Then the measurement model was run with a marker variable added, but all factor loadings were still significant, and the addition of marker variable did not improve statistically. Therefore, this study did not have any issue with common method bias.

4. Results

Covariance based structural equation modelling (CB-SEM) was employed using IBM AMOS 24 for data analysis. The CB-SEM is more suitable in this study because the proposed model was developed based on rigid sound theoretical foundations (the Conservation of Resources and Transformational Leadership theories) for explanatory purposes. Furthermore, the CB-SEM helps to determine how well a theoretical model can estimate the covariance matrix for a sample dataset that suits the proposed model (Hair et al., 2010). In other words, CB-SEM provides fit statistics to evaluate the extent to which the empirical data fit the theoretical research model (Hair et al., 2010).

4.1. Structural model

In order to assess the reliability and validity of the study’s proposed model, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with maximum likelihood estimation was conducted. CFA testing for the whole model presents reasonable fit indices: χ2 = 796.63, df = 389, χ2/df = 2.05, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.95; TLI = 0.94; RMSEA = 0.06 (see Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). Table 1 shows the standardized factor loadings, composite reliabilities, and average variance extracted (AVEs). All of the composite reliabilities exceeded the cut-off level of 0.7 (Nunnally, 1994). All of the AVE values of constructs were above 0.5 (Hair et al., 2010). The data showed adequate discriminant validity because all the values of the AVEs were larger than the squared correlations for each pair of constructs (Fornell & Larcker, 1981) (Table 2 ).

Table 1.

Reliabilities and validities of the study variables.

| Variables | Source | Items | Factor loadings | α | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Role conflict (RC) | Moore (2000) | RC1 | I receive a work task without the manpower to complete it | 0.73 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.69 |

| RC2 | I receive incompatible work requests from two or more people | 0.88 | |||||

| RC3 | I do things that are apt to be accepted by one person and not accepted by others | 0.84 | |||||

| RC4 | I receive a work task without adequate resources and materials to execute it | 0.83 | |||||

| RC5 | I work on unnecessary things | 0.86 | |||||

| Job insecurity (JI) | Vander Elst et al. (2014) | JI1 | Chances are I will soon lose my job | 0.87 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.83 |

| JI2 | I am not sure I can keep my job | 0.81 | |||||

| JI3 | I feel insecure about the future of my job | 0.89 | |||||

| JI4 | I think I might lose my job in the near future | 0.96 | |||||

| JI5 | I am worried about having to leave my job before I would like to | 0.96 | |||||

| JI6 | There is a risk that I will lose my present job in the coming year | 0.92 | |||||

| JI7 | I am worried that I could lose my present job in the near future | 0.95 | |||||

| Cynicism (CN) | Maslach et al. (1996) | CN1 | I have become less enthusiastic about my work | 0.75 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.66 |

| CN2 | I have become more cynical about whether my work contributes anything | 0.90 | |||||

| CN3 | I doubt the significance of my work | 0.86 | |||||

| CN4 | I have become less interested in my work | 0.84 | |||||

| CN5 | I lost my concentration and was bothered by COVID-19 | 0.70 | |||||

| Knowledge hiding (KH) | Peng (2012) | KH1 | I do not want to transfer personal knowledge and experience to others | 0.77 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.69 |

| KH2 | I withhold helpful information or knowledge from others | 0.86 | |||||

| KH3 | I do not want to transform valuable skills and expertise into organizational knowledge | 0.92 | |||||

| KH4 | I do not want to share innovative achievements | 0.75 | |||||

| Job performance(JP) | Chiang and Hsieh (2012) | JP1 | I fulfilled my job responsibilities | 0.82 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.70 |

| JP2 | I met performance standards and expectations of the job | 0.90 | |||||

| JP3 | My performance level satisfied my manager | 0.91 | |||||

| JP4 | I was effective in my job | 0.87 | |||||

| JP5 | My performance was still good as the time before the pandemic | 0.67 | |||||

| Transformational leadership (TL) | Dai et al. (2013) | TL1 | The supervisors can understand my situation and give me encouragement and assistance | 0.86 | 0.78 | 0.93 | 0.78 |

| TL2 | The supervisor encourages me to take the pandemic as challenges | 0.93 | |||||

| TL3 | The supervisor encourages us to make efforts towards fulfilling the company vision during the pandemic | 0.92 | |||||

| TL4 | The supervisor encourages me to think about the pandemic from a new perspective | 0.82 |

Note: α = Cronbach's alpha, CR = composite reliability, AVE = average variance extracted.

Table 2.

Correlation matrix.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Role conflict | 0.83 | |||||

| 2. Job insecurity | 0.53 | 0.91 | ||||

| 3. Cynicism | 0.50 | 0.48 | 0.81 | |||

| 4. Knowledge hiding | 0.45 | 0.48 | 0.52 | 0.83 | ||

| 5. Job performance | −0.02 | −0.18 | −0.16 | −0.19 | 0.84 | |

| 6. Transformational leadership | 0.05 | −0.03 | −0.16 | −0.06 | 0.34 | 0.88 |

The italic numbers in the diagonal row are the square roots of AVE

4.2. Hypotheses testing

Structural equation modelling was performed to test the hypotheses (see Table 3 and Fig. 2 ). We added gender, age, and education as control variables following Tarcan et al. (2017). The model fit was acceptable: χ2 = 736.11, df = 35, χ2/df = 2.07, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.95; TLI = 0.94; RMSEA = 0.06. H1 predicted a positive relationship between role conflict and knowledge hiding. The results support H1 and show that role conflict positively impacts knowledge hiding (ß= 0.16, p < 0.05). H2 predicted a positive relationship between job security and knowledge hiding. Job insecurity also positively affects knowledge hiding (ß= 0.28, p < 0.001), thus supporting H2. H3 predicted a positive relationship between cynicism and knowledge hiding. Cynicism also positively impacts knowledge hiding (ß= 0.32, p < 0.001); therefore, H3 is supported. H4 predicted that knowledge hiding would negatively influence job performance. A negative influence from knowledge hiding on job performance (ß= −0.19, p < 0.01) is found, thus, supporting H4.

Table 3.

Structural equation model.

| Direct effect | |||||

| Knowledge hiding | Job performance | ||||

| Gender | 0.06 | 0.02 | |||

| Age | 0.00 | −0.01 | |||

| Education | 0.08 | 0.12 | |||

| Role conflict | 0.16* | ||||

| Job insecurity | 0.28*** | ||||

| Cynicism | 0.32*** | ||||

| Knowledge hiding | −0.19** | ||||

| Mediating effect of knowledge hiding | |||||

| β | SE | ||||

| Role conflict → Knowledge hiding → Job performance | −0.04* | 0.02 | |||

| Job insecurity → Knowledge hiding → Job performance | −0.02* | 0.01 | |||

| Cynicism → Knowledge hiding → Job performance | −0.03** | 0.02 | |||

| Moderating effect of transformational leadership | |||||

| Standardized regression weight on DV | |||||

| IV | MOD | DV | IV | MOD | IAT |

| Role conflict | Transformational Leadership | Knowledge hiding | −0.04 | 0.36* | −0.13** |

| Job insecurity | Transformational Leadership | Knowledge hiding | 0.32* | −0.02 | 0.02 |

| Cynicism | Transformational Leadership | Knowledge hiding | 0.27 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

Notes: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

DV = Dependent variable; IV = Independent variable; MOD = moderator; IAT = interaction term.

Fig. 2.

The results of measurement and structural model Notes: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

The mediating role of knowledge hiding on the impact of role conflict, job insecurity and cynicism on job performance was analyzed using a bias-corrected bootstrapping procedure with a 5000 bootstrap sample and a 95% confidence level. The results support H5, wherein a significant mediating effect of knowledge hiding on the impact of role conflict (ß= −0.04, p < 0.05), job insecurity (ß= −0.02, p < 0.05) and cynicism (ß= −0.03, p < 0.01), on job performance was noted.

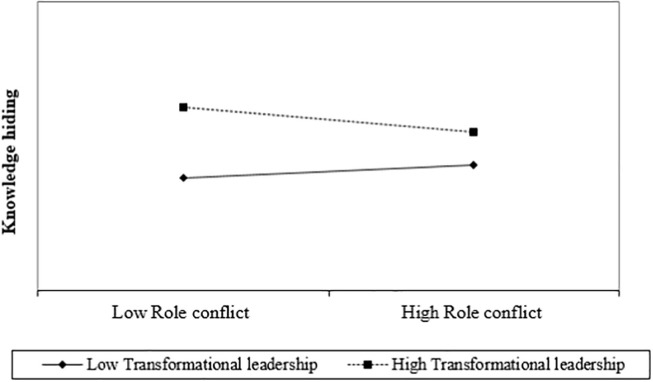

Next, the moderating role of transformational leadership was analyzed. The interactions between transformational leadership and the three antecedents of knowledge hiding (role conflict, job insecurity, and cynicism) were analyzed. The results in Table 3 and Fig. 3 indicate that transformational leadership only moderated the relationship between role conflict and knowledge hiding (ß= −0.13, p < 0.01). Transformational leadership did not moderate the impact of job insecurity (ß= 0.01, p > 0.05) and cynicism (ß= 0.05, p > 0.05) on knowledge hiding. Therefore, H6a was supported, but H6b and H6c were not supported.

Fig. 3.

Moderating effect of transformational leadership.

5. Discussion

This study examined the impact of role conflict, job insecurity, and cynicism on knowledge hiding behavior and the impact of knowledge hiding on job performance. This study shows that role conflict, job insecurity, and cynicism positively influenced knowledge hiding behavior. Role conflict is often manifested in receiving a work task without human resources or adequate resources and materials to complete or incompatible work requests from two or more people. Role conflict tends to make employees feel that they lack resources in the workplace, which motivates them to hold their valuable knowledge to keep their resources not lower than others which is supported by Boz Semerci (2019). The manifestation of job insecurity often permeates the perception that employees will soon lose their jobs and feel insecure about the future of their job, worried about having to leave their job before they would like to (Vander Elst et al. 2014). Such perception often makes employees feel unstable, motivating knowledge hiding to keep their competitive advantage to maintain their job. Similarly, cynicism often makes employees doubt their significance and their ability to contribute to the organization. Consequently, cynical employees tend to hide knowledge because they do not think their knowledge can be valuable to others. These findings are aligned with the COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989). When facing a threat of resource loss (role conflict, job insecurity, and cynicism), employees tend to experience psychological strains, which subsequently motivate employees to react to protect resources (e.g., knowledge hiding) (Hobfoll, 1989, Guo et al., 2020). However, this study extends COR theory by identifying that employees’ threat in organizational crises includes role conflict, job insecurity and cynicism, which are the crucial antecedents of knowledge hiding behavior.

This study also found that knowledge hiding led to a reduction in employee job performance, which is not surprising and in line with Singh (2019) research on the adverse impacts of knowledge hiding on job performance. For example, employees who hide knowledge are inclined to engage in lesser social interactions and knowledge exchange to address their job issues, resulting in lower job performance. However, this study leverages the findings of previous studies, such as by Singh (2019), indicating the mediating role of knowledge hiding, which is rarely examined in existing research. Role conflict, job insecurity, and cynicism are indicated in this study that they affect knowledge hiding and knowledge hiding impacts job performance adversely.

Despite increasing research on transformational leadership and knowledge hiding, scholars to date have investigated these two fields separately (Le & Lei, 2019), and the possible link between them has received less attention. This study examined how, when and why transformational leadership moderates the impact of antecedents on knowledge hiding through the lens of TLT theory (Bass, 1995), thereby addressing a critical gap in the literature.

The existing literature points to a positive relationship between transformational leadership and employee well-being (Arnold, 2017). Although the dominant view in the literature suggests that the moderating effect of transformational leadership can reduce the adverse effect of role conflict, cynicism, and job insecurity on knowledge hiding, we only found support for this relationship between role conflict and knowledge hiding. There was no moderating effect noted for cynicism and job insecurity. A possible explanation for this could be that in times of a crisis, resource depletion also occurs for leaders, which can be draining for them as their emotional and cognitive resources are under pressure, and they become ineffective in reducing the negative relationship noted above (Harms et al., 2017). Additionally, others have found that cynical employees are often close-minded and disillusioned (Stanley et al. 2005). Cynicism can also lead to lower trust among employees towards their leaders (Karlgaard, 2014). The above could lead to the ineffectiveness of TFL in examining this relationship. Finally, concerning job insecurity, as noted above, the perceived sense of job insecurity and helplessness among employees (Greenhalgh & Rosenblatt, 1984) is likely to increase in times of a crisis, and it is unlikely to be reassured with what leaders do if the employees have high levels of cynicism.

This may well help explain the mixed results on the broader research and the insignificance reported in our research. This study’s findings show that transformational leadership moderated the impact of role conflict on knowledge hiding behavior in line with our expectations. Thus, this study shows that it is useful to investigate transformational leadership’s moderating role when examining knowledge hiding.

5.1. Implications

5.1.1. Theoretical implications

Our findings make three key contributions. First, this study contributes to the current body of knowledge hiding literature and extends COR theory by exploring knowledge hiding and its antecedents and consequences in times of organizational crises. Second, this study examines role conflict, job insecurity and cynicism as antecedents of knowledge hiding behavior. Third, this study shows that employees often experience role conflict, job insecurity, and cynicism, especially during organizational crises, which are more likely to make employees engage in knowledge hiding behavior. Although previous studies, such as by Nguyen and Malik (2020), indicate the impact of these factors on knowledge sharing behavior, their impact on the opposite behavior, knowledge hiding, has not been explored.

Second, this study is one of the first to examine the mediation role of knowledge hiding behavior and the impact of role conflict, job insecurity, and cynicism on job performance. Third, this study advances our understanding of the underlying mechanisms between knowledge hiding and its antecedents and consequences. Previous research by Khalid et al., 2018, Singh, 2019 has explored the antecedents’ direct effect on knowledge hiding and knowledge hiding on job performance. Surprisingly, however, less effort has been devoted to understanding the mediation of knowledge hiding and the underlying mechanism in which knowledge hiding links its antecedents with consequences. Drawing on the COR theory, knowledge hiding is considered a reaction to avoid further resource loss due to increased perception of role conflict, job insecurity, and cynicism; then, knowledge hiding behavior decreases job performance. Future research should consider exploring the mediation role of knowledge hiding to further shed light on psychological mechanisms which link the antecedents and consequences of knowledge hiding behavior.

Third, this study contributes to the emerging but limited transformational leadership literature by identifying its role as a moderator in the relationship between antecedents and knowledge hiding behavior. To the best of our knowledge, no study has examined transformational leadership’s moderating role in the relationship between knowledge hiding and its antecedents. Previous scholars such as Le and Lei (2018) have tended to investigate transformational leadership as an antecedent of knowledge sharing behavior, but its moderating role in weakening antecedents’ negative effect on knowledge hiding has rarely been explored. This study’s findings suggest that transformational leadership effectively reduces perception about role conflict, which reduces the effect of role conflict on knowledge hiding behavior. By verifying the moderating role of transformational leadership, this study provides insights into the boundary conditions under which transformational leadership creates a favourable working environment. In such an environment, role conflict is less detrimental to employees’ psychological constraints, leading to negative reactions, including knowledge hiding. Future researchers may wish to explore the moderation role of transformational leadership to provide more insights into strategies designed to minimize knowledge hiding behavior. Fourth, this study develops a conceptual model and empirically validates the relationships by integrating three related theories. Finally, the paper also contributes contextually by studying the impact of organizational crises in Vietnam’s emerging market context.

5.1.2. Practical implications

From the findings of this study, some practical implications are proposed. First, the finding of this study showed that role conflict could prompt knowledge-hiding behavior; thus, organizations need to make an effort to minimize role conflict. For instance, managers may need to understand their employees’ capabilities and goals to allocate tasks. Training or mentoring can be helpful for newly assigned roles or tasks.

This study shows that decreased job insecurity and cynicism can reduce knowledge hiding behavior and indirectly influence employee job performance. Therefore, managers should consider job re-design, offer work enrichment and empowerment, and develop adequate compensation policies to encourage employees to share their resources in an inclusive and caring environment (Pee & Lee, 2015). In addition, leadership needs to provide encouragement, necessary help, and assistance to motivate employees to share knowledge (Le & Lei, 2019). Leadership also needs to encourage employees to perceive that success in their goal and career and the company vision is closely related to knowledge sharing, with an understanding that knowledge hiding will lead to negative consequences for the organization’s development. In such cases, employees will be more motivated to share knowledge and reduce knowledge hiding behavior.

5.2. Limitation and future research

Our study has some limitations that offer avenues for future research. First, this study examined the conceptual framework in a single country, Vietnam. Future studies may want to investigate the model in other countries or contexts. Second, the data were collected in a single time point and used a self-reported survey. A longitudinal study or experiments will be useful to examine behaviour changes over different periods. We also recommend collecting data from different countries to compare the results across countries or control cultural backgrounds.

Furthermore, future researchers may want to consider different target respondents, such as supervisor-employee dyads. Third, another limitation of this study is the lack of personality trait variables when examining the model. Future researchers may want to include personality trait variables to understand further knowledge hiding behavior linked to different personality trait variables. Fourth, the present study merely explores transformational leadership’s moderating role in the relationship between knowledge hiding and its antecedents. We hope that in the future, researchers explore diverse sets of leadership styles for examining its moderating influence on knowledge hiding and its antecedents. However, other possible moderators such as top management support can be considered to draw a complete picture of the factors that may weaken this relationship. Finally, this research investigated job performance as the outcome of knowledge hiding. Future research should investigate other outcomes, such as the impact on innovation or productivity. Despite the above limitations, this paper convincingly addressed our research objectives.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Biographies

Tuyet-Mai is a research fellow in the Social Marketing @ Griffith at Griffith University in Brisbane, Australia. She is also a senior lecturer at Thuongmai University, Vietnam. Her research interests are Knowledge Management, Human Resource Management and Social Marketing. Her work is published in several high-ranked journals, including Journal of Knowledge Management and Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services. She can be contacted at mai.journalarticles@gmail.com or maidhtm@tmu.edu.vn

Ashish is an Associate Professor at University of Newcastle, Central Coast, Australia. His research is at the interface of strategy, HRM and innovation management focusing on knowledge-intensive services industries in an international context. He serves as Associate Editor (HRM) for the Journal of Business Research and Asian & Business Management and a member of Editorial Board of Human Resource Management Review and Journal of Knowledge Management. His work is published in several high-ranked journals, including Harvard Business Review, MIT Sloan Management Review, Human Resource Management Review, International Journal of Human Resource Management, Industrial Marketing Management, Journal of Business Research, Journal of International Management, among others. He can be contacted at ashish.malik@newcastle.edu.au

Professor Pawan Budhwar is the Head of Aston Business School and is the 50th Anniversary Professor of International HRM at Aston Business School. He is the Joint Director of Aston India Centre for Applied Research at Aston University and the Co-Editor-in-Chief of British Journal of Management. Pawan is the co-founder and first President of the Indian Academy of Management, an affiliate of AOM. Pawan has published over 150 articles in leading journals on topics related to people management, with a specific focus on India. He has also written and/or co-edited 21 books on HRM-related topics for different national and regional contexts. He is Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences, the Higher Education Academy, the British Academy of Management and the Indian Academy of Management, and chartered member of the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD).

References

- Aarabi M.S., Subramaniam I.D., Akeel A.B.A.A.B. Relationship between motivational factors and job performance of employees in Malaysian service industry. Asian Social Science. 2013;9(9):301–310. doi: 10.5539/ass.v9n9p301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ali M., Ali I., Albort-Morant G., Leal-Rodríguez A.L. How do job insecurity and perceived well-being affect expatriate employees’ willingness to share or hide knowledge? International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11365-020-00638-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aljawarneh N.M.S., Atan T. Linking tolerance to workplace incivility, service innovative, knowledge hiding, and job search behavior: The mediating role of employee cynicism. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research. 2018;11(4):298–320. doi: 10.1111/ncmr.2018.11.issue-410.1111/ncmr.12136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alper S., Tjosvold D., Law K.S. Conflict management, efficacy, and performance in organizational teams. Personnel Psychology. 2000;53(3):625–642. doi: 10.1111/peps.2000.53.issue-310.1111/j.1744-6570.2000.tb00216.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold K.A. Transformational leadership and employee psychological well-being: A review and directions for future research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2017;22(3):381–393. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blau P.M. Transaction Publishers; New Brunswick: 1964. Exchange and power in social life. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold K.A., Loughlin C., Walsh M.M. Transformational leadership in an extreme context. Leadership & Organization Development Journal. 2016;37(6):774–788. doi: 10.1108/LODJ-10-2014-0202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arshad R., Ismail I.R. Workplace incivility and knowledge hiding behavior: Does personality matter? Journal of Organizational Effectiveness. 2018;5(3):278–288. doi: 10.1108/JOEPP-06-2018-0041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartol K.M., Liu W., Zeng X., Wu K. Social exchange and knowledge sharing among knowledge workers: The moderating role of perceived job security. Management and Organization Review. 2009;5(2):223–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8784.2009.00146.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury S. The role of affect-and cognition-based trust in complex knowledge sharing. Journal of Managerial issues. 2005;17(3):310–326. [Google Scholar]

- Bass B.M. Theory of transformational leadership redux. The Leadership Quarterly. 1995;6(4):463–478. doi: 10.1016/1048-9843(95)90021-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bedeian A.G. Even if the tower is “Ivory”, it isn’t “White:” Understanding the consequences of faculty cynicism. Academy of Management Learning & Education. 2007;6(1):9–32. doi: 10.5465/AMLE.2007.24401700. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bircham-Connolly H., Corner J., Bowden S. An empirical study of the impact of question structure on recipient attitude during knowledge sharing. Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management. 2005;32(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Beijer S., Peccei R., Veldhoven M., Paauwe J. The turn to employees in the measurement of human resource practices: A critical review and proposed way forward. Human Resource Management Journal. 2021;31(1):1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bergström O., Styhre A., Thilander P. Paradoxifying organizational change: Cynicism and resistance in the Swedish Armed Forces. Journal of Change Management. 2014;14(3):384–404. [Google Scholar]

- Boz Semerci A. Examination of knowledge hiding with conflict, competition and personal values. The International Journal of Conflict Management. 2019;30(1):111–131. doi: 10.1108/ijcma-03-2018-0044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brislin R.W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-cultural Psychology. 2016;1(3):185–216. doi: 10.1177/135910457000100301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Budhwar P., Cumming D. New directions in management research and communication: Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic. British Journal of Management. 2020;31:441. [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright S., Holmes N. The meaning of work: The challenge of regaining employee engagement and reducing cynicism. Human Resource Management Review. 2006;16(2):199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2006.03.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Černe M., Nerstad C.G.L., Dysvik A., Škerlavaj M. What goes around comes around: Knowledge hiding, perceived motivational climate, and creativity. Academy of Management Journal. 2014;57(1):172–192. [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Duan Y., Edwards J.S., Lehaney B. Toward understanding inter-organizational knowledge transfer needs in SMEs: Insight from a UK investigation. Journal of Knowledge Management. 2006;10(3):6–23. doi: 10.1108/13673270610670821. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Zhang X., Vogel D. Exploring the underlying processes between conflict and knowledge sharing: A work-engagement perspective. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2011;41(5):1005–1033. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2011.00745.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang C.-F., Hsieh T.-S. The impacts of perceived organizational support and psychological empowerment on job performance: The mediating effects of organizational citizenship behavior. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2012;31(1):180–190. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.04.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Civi E. Knowledge management as a competitive asset: A review. Marketing Intelligence & Planning. 2000;18(4):166–174. doi: 10.1108/02634500010333280. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cole M.S., Bruch H., Vogel B. Emotion as mediators of the relations between perceived supervisor support and psychological hardiness on employee cynicism. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2006;27(4):463–484. doi: 10.1002/(ISSN)1099-137910.1002/job.v27:410.1002/job.381. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cole M.S., Walter F., Bedeian A.G., O’Boyle E.H. Job burnout and employee engagement: A meta-analytic examination of construct proliferation. Journal of Management. 2012;38(5):1550–1581. doi: 10.1177/0149206311415252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman J.S. Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology. 1988;94:S95–S120. [Google Scholar]

- Collings D.G., Nyberg A.J., Wright P.M., McMackin J. Leading through paradox in a COVID-19 world: Human resources comes of age. Human Resource Management Journal. 2021 doi: 10.1111/1748-8583.12343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly C.E., Černe M., Dysvik A., Škerlavaj M. Understanding knowledge hiding in organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2019;40(7):779–782. doi: 10.1002/job.v40.710.1002/job.2407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly C.E., Zweig D., Webster J., Trougakos J.P. Knowledge hiding in organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2012;33(1):64–88. doi: 10.1002/job.737. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coupe T. Automation, job characteristics and job insecurity. International Journal of Manpower. 2019;40(7):1288–1304. doi: 10.1108/IJM-12-2018-0418. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y.-D., Dai Y.-Y., Chen K.-Y., Wu H.-C. Transformational vs transactional leadership: Which is better? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. 2013;25(5):760–778. doi: 10.1108/ijchm-dec-2011-0223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport L.J., Allisey A.F., Page K.M., LaMontagne A.D., Reavley N.J. How can organizations help employees thrive? The development of guidelines for promoting positive mental health at work. International Journal of Workplace Health Management. 2016;9(4):411–427. doi: 10.1108/IJWHM-01-2016-0001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Dreu C.K.W., van Dierendonck D., Dijkstra M.T.M. Conflict at work and individual well-being. The International Journal of Conflict Management. 2004;15(1):6–26. doi: 10.1108/eb022905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Debus M.E., Unger D. The interactive effects of dual-earner couples’ job insecurity: Linking conservation of resources theory with crossover research. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 2017;90(2):225–247. doi: 10.1111/joop.2017.90.issue-210.1111/joop.12169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Domenighetti G., D’Avanzo B., Bisig B. Health effects of job insecurity among employees in the Swiss general population. International Journal of Health Services. 2000;30(3):477–490. doi: 10.2190/B1KM-VGN7-50GF-8XJ4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellmer M., Reichel A. Mind the channel! An affordance perspective on how digital voice channels encourage or discourage employee voice. Human Resource Management Journal. 2021;31(1):259–276. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell C., Larcker D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research. 1981;18(1):39–50. doi: 10.2307/3151312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foss N.J., Pedersen T., Reinholt Fosgaard M., Stea D. Why complementary HRM practices impact performance: The case of rewards, job design, and work climate in a knowledge-sharing context. Human Resource Management. 2015;54(6):955–976. doi: 10.1002/hrm.21649. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gahan P., Theilacker M., Adamovic M., Choi D., Harley B., Healy J., Olsen J.E. Between fit and flexibility? The benefits of high-performance work practices and leadership capability for innovation outcomes. Human Resource Management Journal. 2021;31(2):414–437. [Google Scholar]

- Grandey A., Cropanzano R. The Conservation of Resources model applied to work-family conflict and strain. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 1999;54(2):350–370. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.1998.1666. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh L., Rosenblatt Z. Job insecurity: Toward conceptual clarity. Academy of Management Review. 1984;9(3):438–448. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L., Cheng, K., & Luo, J. (2020). The effect of exploitative leadership on knowledge hiding: a conservation of resources perspective. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 42(1): 83-98. 10.1108/LODJ-03-2020-0085.

- Haldin-Herrgard T. Difficulties in diffusion of tacit knowledge in organizations. Journal of Intellectual capital. 2000;1(4):357–365. doi: 10.1108/14691930010359252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective (7th ed.). New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Halbesleben J.R. Sources of support and burnout: A meta analytic test of the conservation of resources model. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2006;91(5):1134–1145. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.5.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbesleben J.R., Harvey J., Bolino M.C. A conservation of resources view of the relationship between work engagement and work interference with family. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2009;94(6):1452–1465. doi: 10.1037/a0017595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harms P.D., Credé M., Tynan M., Leon M., Jeung W. Leadership and stress: A meta-analytic review. The Leadership Quarterly. 2017;28(1):178–194. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang Y. Understanding moderating effects of collectivist cultural orientation on the knowledge sharing attitude by email. Computers in Human Behavior. 2012;28(6):2169–2174. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2012.06.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hernaus T., Cerne M., Connelly C., Poloski Vokic N., Škerlavaj M. Evasive knowledge hiding in academia: When competitive individuals are asked to collaborate. Journal of Knowledge Management. 2018 doi: 10.1108/JKM-11-2017-0531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hickland E., Cullinane N., Dobbins T., Dundon T., Donaghey J. Employer silencing in a context of voice regulations: Case studies of non-compliance. Human Resource Management Journal. 2020;30(4):537–552. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. The American Psychologist. 1989;44(3):513–524. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C.-C. Knowledge sharing and group cohesiveness on performance: An empirical study of technology R&D teams in Taiwan. Technovation. 2009;29(11):786–797. doi: 10.1016/j.technovation.2009.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huo W.W., Cai Z.Y., Luo J.L., Men C.H., Jia R.Q. Antecedents and intervention mechanisms: A multilevel study of R&D team’s knowledge hiding behavior. Journal of Knowledge Management. 2016;20(5):880–897. doi: 10.1108/JKM-11-2015-0451. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Issac A.C., Baral R. Dissecting knowledge hiding: A note on what it is and what it is not. Human Resource Management International Digest. 2018;26(7):20–24. doi: 10.1108/HRMID-09-2018-0179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Issac A.C., Baral R., Bednall T.C. Don’t play the odds, play the man: Estimating the driving potency of factors engendering knowledge hiding behaviour in stakeholders. European Business Review. 2020;32(3):531–551. doi: 10.1108/EBR-06-2019-0130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- James E.H., Wooten L.P., Dushek K. Crisis management: Informing a new leadership research agenda. Academy of Management Annals. 2011;5(1):455–493. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis C., MacKenzie S., Podsakoff P. A critical review of construct indicators and measurement model misspecification in marketing and consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research. 2003;30(2):199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z., Hu X., Wang Z., Jiang X. Knowledge hiding as a barrier to thriving: The mediating role of psychological safety and the moderating role of organizational cynicism. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2019;40(7):800–818. doi: 10.1002/job.2358. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y.J., Lee J.Y., Kim H.-W. A psychological empowerment approach to online knowledge sharing. Computers in Human Behavior. 2017;74(Supplement C):175–187. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.04.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karlgaard R. John Wiley & Sons; 2014. The soft edge: Where great companies find lasting success. [Google Scholar]

- Khalid M., Bashir S., Khan A.K., Abbas N. When and how abusive supervision leads to knowledge hiding behaviors: An Islamic work ethics perspective. Leadership and Organization Development Journal. 2018;39(6):794–806. doi: 10.1108/LODJ-05-2017-0140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khan N.A., Khan A.N., Gul S. Relationship between perception of organizational politics and organizational citizenship behavior: Testing a moderated mediation model. Asian Business & Management. 2019;18(2):122–141. doi: 10.1057/s41291-018-00057-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- König A., Graf-Vlachy L., Bundy J., Little L.M. A blessing and a curse: How CEOs’ trait empathy affects their management of organizational crises. The Academy of Management Review. 2020;45(1):130–153. doi: 10.5465/amr.2017.0387. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kranabetter C., Niessen C. Managers as role models for health: Moderators of the relationship of transformational leadership with employee exhaustion and cynicism. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2017;22(4):492–502. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwahk K.-Y., Park D.-H. The effects of network sharing on knowledge-sharing activities and job performance in enterprise social media environments. Computers in Human Behavior. 2016;55:826–839. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Le P.B., Lei H. The mediating role of trust in stimulating the relationship between transformational leadership and knowledge sharing processes. Journal of Knowledge Management. 2018;22(3):521–537. [Google Scholar]

- Le P.B., Lei H. Determinants of innovation capability: The roles of transformational leadership, knowledge sharing and perceived organizational support. Journal of Knowledge Management. 2019;23(3):527–547. [Google Scholar]

- Lee K.-J. Sense of calling and career satisfaction of hotel frontline employees: Mediation through knowledge sharing with organizational members. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. 2016;28(2):346–365. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-01-2014-0026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lefevre E., Colot O., Vannoorenberghe P. Belief function combination and conflict management. Information Fusion. 2002;3(2):149–162. doi: 10.1016/s1566-2535(02)00053-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leong L.Y.C., Fischer R. Is transformational leadership universal? A meta-analytical investigation of multifactor leadership questionnaire means across cultures. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies. 2010;18(2):164–174. doi: 10.1177/1548051810385003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H.F. Effects of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation on employee knowledge sharing intentions. Journal of Information Science. 2007;33(2):135–149. doi: 10.1177/0165551506068174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malik A. Post-GFC people management challenges: A study of India’s information technology sector. Asia PacificBusiness Review. 2013;19(2):230–246. [Google Scholar]

- Malik A. Routledge; London, UK: 2018. Human resource management and the global financial crisis: Evidence from India’s IT/BPO Industry. [Google Scholar]

- Malik A., Sanders K. Managing human resources during a global crisis: A multilevel perspective. British Journal of Management. 2021 doi: 10.1111/1467-8551.12484. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malik A., Sinha P., Pereira V., Rowley C. Implementing global-local strategies in a post-GFC era: Creating an ambidextrous context through strategic choice and HRM. Journal of Business Research. 2019;103:557–569. [Google Scholar]

- Maravilhas S., Martins J. Strategic knowledge management in a digital environment: Tacit and explicit knowledge in Fab Labs. Journal of Business Research. 2019;94:353–359. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.01.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maslach C., Jackson S., Leiter M. 3rd ed. Consulting Psychologists Press Inc.; Palo Alto (CA): 1996. Maslach burnout inventory manual. [Google Scholar]

- Montag‐Smit, T. A., & Smit, B. W. (2020). What are you hiding? Employee attributions for pay secrecy policies. Human Resource Management Journal, 10.1111/1748-8583.12292.

- Moore J.E. One road to turnover: An examination of work exhaustion in technology professionals. MIS Quarterly. 2000;24(1):141–168. doi: 10.2307/3250982. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T.-M., Malik A. Cognitive processes, rewards and online knowledge sharing behaviour: The moderating effect of organizational innovation. Journal of Knowledge Management. 2020;24(6):1241–1261. doi: 10.1108/JKM-12-2019-0742. [DOI] [Google Scholar]