Abstract

Clear cell ("hemangioblastoma-like”) stromal tumor of the lung (CCST-L) is a recently described distinctive rare pulmonary neoplasm of unknown histogenesis and molecular pathogenesis. Only seven cases have been reported in two recent studies, although additional cases might have been reported under the heading of extra-neural pulmonary hemangioblastoma. We herein describe 4 CCST-L cases, 3 of them harboring a YAP1-TFE3 fusion. The fusion-positive tumors occurred in 3 females, aged 29, 56 and 69 years. All presented with solitary lung nodules measuring 2.3 to 9.5 cm. Histologically, all tumors showed similar features being composed of relatively uniform medium-sized epithelioid to ovoid cells with clear cytoplasm and small round monomorphic nuclei. Scattered larger cells with enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei and marked pleomorphism were noted in two cases. The tumors were associated with a hypervascularized stroma with variable but essentially subtle resemblance to capillary hemangioblastoma and perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa). Immunohistochemistry was negative for all lineage-specific markers. Targeted RNA sequencing revealed a YAP1-TFE3 fusion in 3 of 4 cases. All three tumors revealed homogeneous nuclear TFE3 immunoreactivity. Two patients were disease-free at 36 and 12 month. The third patient had biopsy-proven synchronous renal and hepatic metastases, but extended follow-up is not available (recent case). The 4th case lacking the fusion affected a 66-year-old female and showed subtle histological differences from the fusion-positive cases, but had comparable TFE3 immunoreactivity. CCST-L represents a distinctive entity unrelated to hemangioblastoma and likely driven by recurrent YAP1-TFE3 fusions in most cases. The relationship of our cases to the recently reported “hemangioblastoma-like” CCST-L remains to be determined. Analysis of larger series is paramount to delineate the morphologic spectrum and biologic behaviour of this poorly characterized entity.

Keywords: hemangioblastoma, clear cell sugar tumor, PEComa, TFE3, YAP1, lung, VHL

INTRODUCTION

In contrast to metastases from diverse soft tissue sarcomas, primary mesenchymal neoplasms of the lung are uncommon. Hemangioblastoma is a rare mesenchymal neoplasm mostly involving the central nervous system (cerebellum) and rarely other extraneural sites, composed of an admixture of clear "lipid-rich" epithelioid cells embedded in a highly vascularized stroma rich in capillaries, hence the name capillary hemangioblastoma.1-3 Among ~200 reported cases (reviewed by Bisceglia et al1), none of 65 peripheral cases (15 within soft tissue, 6 of peripheral nerve origin, 5 within bone, 26 renal and 13 within other organs) was pulmonary in origin.1 Hemangioblastoma is considered a marker lesion of von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL) with half of reported peripheral hemangioblastomas affecting patients with features suggestive of VHL1 while one patient had tuberous sclerosis.3 Pulmonary hemangioblastoma is exceptionally rare. Its first description dates back to 1943.4 Since then, only four cases have been described; all presented with multiple, frequently bilateral tumors in patients with extrapulmonary (mainly central) disease and were hence interpreted as metastatic (reviewed in ref. [5]).

In 2013, Falconieri et al described two primary lung lesions that were morphologically overlapping with hemangioblastoma but lacking phenotypic features of that entity.6 They coined the term "hemangioblastoma-like clear cell stromal tumor of the lung" for this rare putative tumor entity.6 More recently, a series describing 5 additional tumors was published by Lindholm and Moran.5 We herein describe 4 new cases of this rare lesion, in which targeted RNA-based next generation sequencing revealed a novel YAP1-TFE3 fusion in three of the four cases tested.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cases were identified in the consultation files of the authors. The tissue specimens were fixed in formalin and processed routinely for histopathology. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed on 3-μm sections cut from paraffin blocks using a fully automated system (“Benchmark XT System”, Ventana Medical Systems Inc., 1910 Innovation Park Drive, Tucson, Arizona, USA) and the following antibodies: vimentin (V9, 1:100, Dako), keratin cocktail (clone AE1/AE3, 1:40, Zytomed, Berlin, Germany), p63 (SSI6, 1: 100, DCS), desmin (clone D33, 1:250, Dako), alpha smooth muscle actin (clone 1A4, 1:200, Dako), HMB45 (clone HMB45, 1:50, Enzo), Melan A (clone A103, 1:50, Dako), CD34 (clone BI-3C5, 1:200, Zytomed), ERG (EPR3864, prediluted, Ventana), CD31 (clone JC70A, 1:20, Dako), S100 protein (polyclonal, 1:2500, Dako), SOX10 (polyclonal, 1:25, DCS), PAX8 (polyclonal rabbit anti-PAX8, 1:50, Cell Marque), NSE (clone BBS/NC/VI-H1, 1:300, Dako), TTF1 (clone 8G7G3/1, 1:500, Zytomed Systems, Berlin, Germany), Napsin A (MRQ-60, ready-to-use, Medac), calretinin (polyclonal, 1:100, Zytomed), alpha-inhibin (clone R1, 1:50, Serotec), GFAP (Clone GFA, 1/1000, DakoPatts, Denmark), EMA (clone E29, 1:200, Dako), STAT6 (clone S-20, 1:1000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), TFE3 (clone MRQ-37, 1:100, Cell Marque), Cathepsin-K (clone 3F9, 1:50, Abcam) and Ki67 (clone MiB1, 1:100, Dako).

Next generation sequencing

For Cases 1, 2, and 4 (Table 1), RNA was isolated from formalin-fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tissue sections using RNeasy FFPE Kit of Qiagen (Hilden, Germany) and quantified spectrophotometrically using NanoDrop-1000 (Waltham, United States). Molecular analysis was performed using the TruSight RNA Fusion panel (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) with 500 ng RNA as input according to the manufacturer`s protocol. Libraries were sequenced on a MiSeq (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) with > 3 million reads per case, and sequences were analyzed using the RNA-Seq Alignment workflow, version 2.0.1 (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV), version 2.2.13 (Broad Institute, REF) was used for data visualization.7

Clinicopathological and molecular features of clear cell stromal tumors of the lung

| Age/sex | Site/size(cm) | Original diagnosis | Treatment | Other manifestations | RNA fusion panel | TFE3 IHC | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 56/F | LUL/ lingula/ 2.3 cm | Unusual TFE3+ PEComa | Upper lobectomy | No | YAP1 exon 4/ TFE3 exon 7 | +++ | NED (36 mo) |

| 2 | 29/F | Lung not specified/ 9.5 cm | Hemangioblastoma-like CCST | Not specified | Multiple metastases in both kidneys & liver | YAP1 exon 5/TFE3 intron 6 | +++ | NA (recent case) |

| 3 | 69/F | LUL/ 4 cm | DDx: GLI1-positive tumor | Pneumonectomy | Hilar nodes positive | YAP1 exon 4/ TFE3 exon 7 | +++ | NED (12 mo) |

| 4 | 66/F | Left main bronchus/NA | Hemangioblastoma-like CCST | Biopsied | No | No fusion | +++ | Persistent disease over 4 years |

NA=not available; CCST=clear cell stroma tumor; DDx: differential diagnosis; F=female; IHC=immunohistochemistry; LUL= left upper lobe; mo=month; NA=not available

NED=no evidence of disease

Case 3 was subjected to targeted RNA sequencing (Archer FusionPlex Custom Solid Panel) to assess for gene fusions. The detailed procedure of Anchored Multiplex PCR RNA sequencing assay has been previously described.8,9 Unidirectional gene-specific primers were designed to target specific exons in 62 genes known to be involved in oncogenic fusions in solid tumors. Both DNA and RNA sequencing was additionally performed in Case 4 using Illumina TruSight Oncology 500 panel (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer`s protocol.

Fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) was performed in Case 1, 2 and 4 using the ZytoLight SPEC TFE3 Dual Color Break Apart Probe (ZytoVision, Bremerhaven, Germany) designed to detect translocations involving the chromosomal region Xp11.23 harboring the TFE3 gene with standard protocols according to the manufacturer`s instructions. Fifty tumor cells were visually inspected using a fluorescence microscope. As all patients were females, the presence of two pairs of fused green and orange signals was considered normal findings. On the other hand, presence of one fused orange/green signal and one separate orange and green signal indicates translocation. For Case 3 custom BAC probes were applied as previously described10, which showed the presence of both TFE3 and YAP1 gene rearrangements. Case 4 was also analyzed using SureFISH 11q22.1 YAP1 Break Apart Probe (SureFISH / Agilent).

RESULTS

Clinical features of YAP1-TFE3 fusion-positive CCST of the lung

Patients were three females aged 29, 56 and 69 years (median, 56; Table 1). None had clinical evidence of VHL or other genetic abnormality. Two patients (Cases 1 and 2) initially presented with hemoptysis. Two tumors with detailed findings were located in the upper lobe (Fig. 1A and B) and one at an unspecified lung site. Case 1 (depicted in figure 1) was positive on PET scan and radiological diagnosis was in keeping with a “malignant lung tumor”. Detailed imaging findings were not available for other cases. The tumors were removed via variable surgical procedures including lobectomy (1), total pneumonectomy (1) or unspecified excision (1). One tumor was biopsied only. Extended follow-up data was available for three cases (12, 36 and 48 months). Two patients had no evidence of disease 12 and 36 months after diagnosis. One tumor has been initially biopsied only and persisted over 4 years. One patient (Case 2 with the largest tumor) presented with multiple synchronous biopsy-proven metastases in the kidneys and the liver, but no extended follow-up is available (recent case).

FIGURE 1.

Preoperative CT (A) and PET-CT (B) of case 1 show a well-circumscribed tumor nodule in the left upper lobe of the lung.

Pathological findings

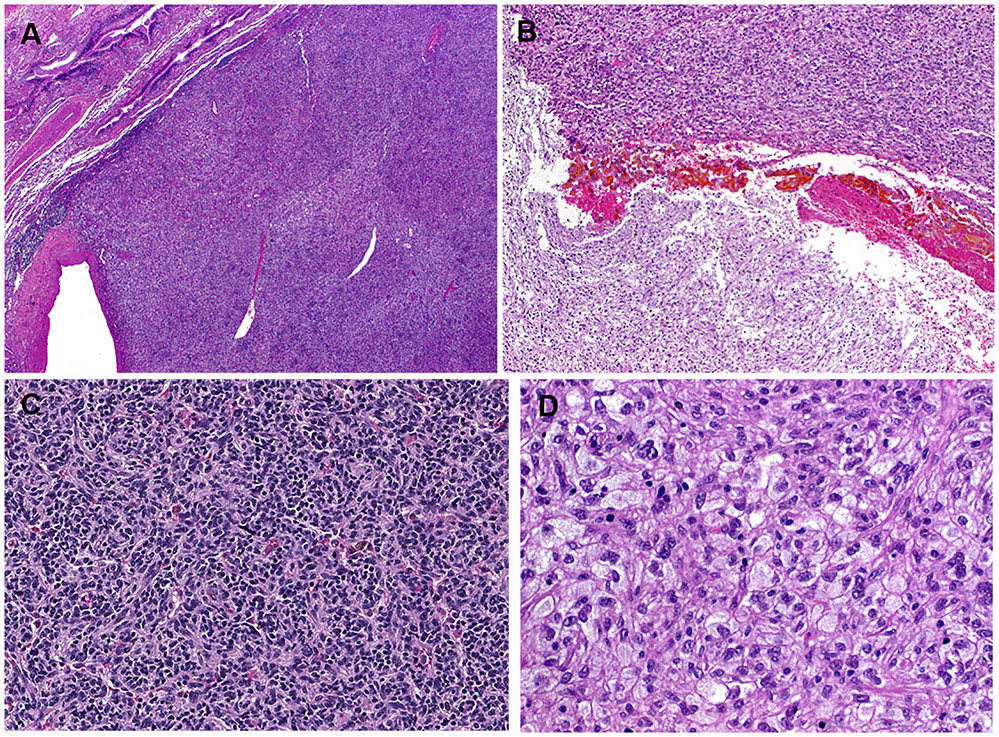

The tumor size ranged from 2.3 to 9.5 cm (median, 4). All tumors were solitary and well circumscribed but non-encapsulated. There was significant histological overlap among all cases. The tumors were closely associated with the bronchial tree and were well defined peripherally (Fig. 2A). Central areas of confluent, partially hemorrhagic, ischemic-type necrosis were seen in two cases (Fig. 2B). The tumor cells were medium to large-sized monomorphic polygonal epithelioid to ovoid or slightly spindled cells, with variably clear, pale and focally foamy histiocytoid or flocculent cytoplasm (Fig. 2C-D). Microvesicular, lipid-rich xanthomatous cytoplasmic features were however not evident. The vascular spaces ranged from thin-walled to hyalinized or rarely thick-walled (Fig. 3A). Scattered cells with mummified, larger and hyperchromatic nuclei with irregular lobulated nuclear contours were seen in two cases (Fig. 3A, B). Foci of spindle cells were observed in all cases (Fig. 3C). Involvement of the adjacent lung tissue was seen at the periphery of all cases despite the overall well circumscription, where entrapped alveolar tissue mimicked pseudovascular pattern (Fig. 3D) or a biphasic neoplasm (Fig. 3E). The PAS stain highlighted abundant diastase-sensitive intracytoplasmic material consistent with glycogen deposits (Fig. 3F). There were also scattered focally prominent mononuclear inflammatory cells within the stroma (Fig. 3C). The nuclei were bland without mitoses. No coagulative necrosis was seen. Lymphovascular and perineural invasion were absent in all cases. The resection margins were free of tumor.

FIGURE 2.

Representative images of clear cell stromal tumor of the lung (CCST-L). At low-power, the tumors are closely associated with the bronchial tree and look well circumscribed peripherally (A). Confluent central areas of ischemic-type necrosis are seen (B). At low-power, areas with moderate cellularity and vaguely nested pattern with scattered small lymphocytes in the background are seen (C). At high power, the stroma is sparse and the cytology was clear cell to flocculent and pale with histiocytoid appearance (D).

FIGURE 3.

Potentially misleading features in CCST-L include thick-walled pericytoma-like vessels (A), scattered bizarre hyperchromatic lobulated likely degenerative nuclei (A, B), spindling with scattered monocular cells resembling inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (C), entrapped pseudovascular alveolar spaces (D), and prominent entrapment of regenerative alveolar epithelium mimicking salivary-type biphasic lesion (E). Periodic Schiff stain highlights prominent cytoplasmic glycogen (F).

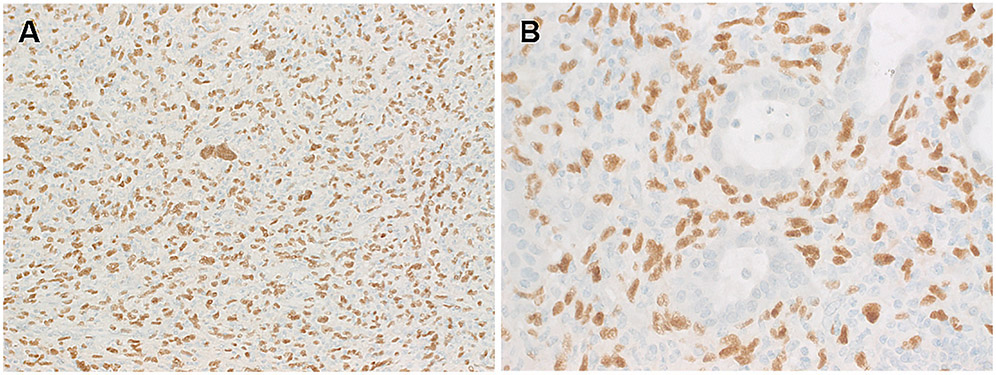

Immunohistochemistry revealed uniform expression of vimentin, but not pankeratin, PAX8, endothelial markers, S100, inhibin, NSE or other markers listed in the method section. Case 3 showed reactivity for CD10, focal NSE, and rare labeling for SMA. All three tumors showed uniform strong and diffuse nuclear expression of TFE3 limited to the neoplastic cells (Fig. 4A-B). Ki67 labeled <2% of the nuclei in Cases 1, 2 and 20% in Case 3.

FIGURE 4.

By immunohistochemistry, the neoplastic cells of CCST-L lacked expression of any lineage markers but expressed diffusely vimentin (not shown) and TFE3. Note strong, diffuse and homogeneous TFE3 immunoreactivity limited to the neoplastic cells highlighting also the scattered bizarre nuclei (in A) and sparing the entrapped alveolar glands (in B).

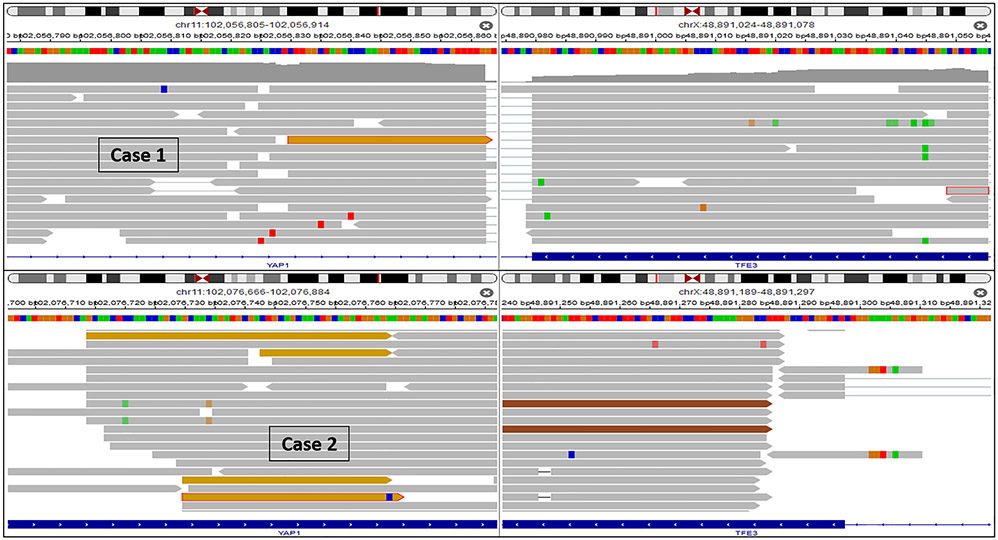

Molecular results

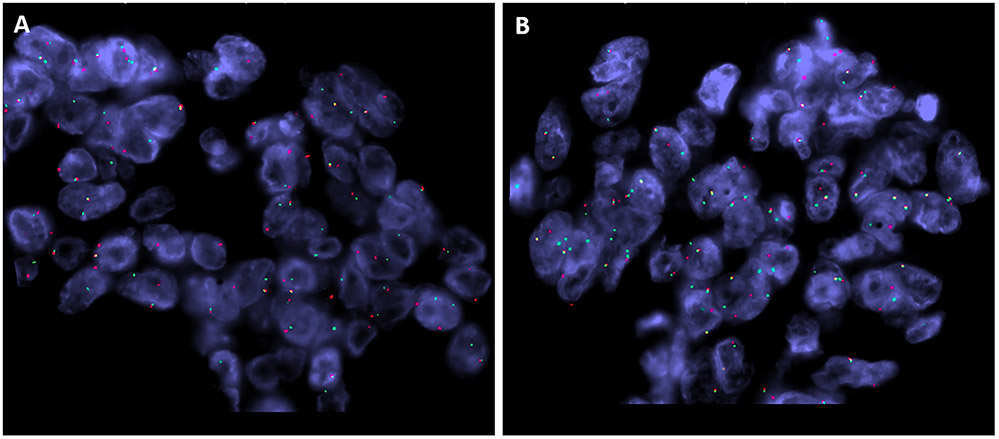

Case 1, 2 and 3 revealed a YAP1-TFE3 gene fusion. In Case 1 and 3, the fusion breakpoints were located in exon 4 (chr11:102056861:+) of YAP1 and in exon 7 (chrX:48891297:-) of TFE3. In case 2 the fusion breakpoints were located in exon 5 (chr11:102076763:+) of YAP1 and intron 6 (chrX:48891616:-) of TFE3 (Fig. 5). FISH analysis was negative for translocation in Case 1 (likely due to the design of the FISH probe which we used) and failed in Case 2. FISH performed in Case 3 showed break-apart signals for both TFE3 and YAP1 in keeping with gene rearrangements (Fig 6).

FIGURE 5.

IGV split-screen view of read alignments of the identified YAP1-TFE3 fusion event of case 1 and 2. Shown are the breakpoints in the YAP1 (left) and the TFE3 locus (right), respectively. Alignments whose mate pairs are mapped to the fusion sequence on the other chromosome are colored ocher. All other alignments are colored grey, green, red and brown.

FIGURE 6.

FISH (Case 3) showing break-apart signals for both TFE3 (A) and YAP1 (B), in keeping with gene rearrangements (red, centromeric; green, telomeric).

YAP1-TFE3 fusion-negative CCST of the lung

Case 4 affected a 66-year-old female who presented with an exophytic lesion blocking the left main bronchus. The tumor was biopsied initially and persisted over the next 4 years. Histologically, this fusion-negative case displayed essentially comparable overall appearance with medium-sized polygonal clear cells disposed into diffuse sheets within a fibrovascular stroma (Fig. 7A-B). However, compared to the fusion-positive cases, the lesional clear cells had better delineated cell borders, lacked the prominent flocculent cytoplasmic appearance and showed smaller and more uniform condensed nuclei (Fig. 7C). Immunohistochemical findings were similar to the fusion-positive cases, including homogeneous TFE3 expression (Fig. 7D). Ki67 labeled <2% of the nuclei. The targeted RNA sequencing was negative for YAP1-TFE3 and other fusions. The FISH testing for TFE3 abnormalities was negative for rearrangements or amplification. The DNA sequencing in this case (Illumina TruSight Oncology 500 panel) revealed a SETD2 (c.4742G>A, p.(Gly1581Glu)) mutation. Unfortunately, non-neoplastic tissue was not available for comparison to filter out germline variants.

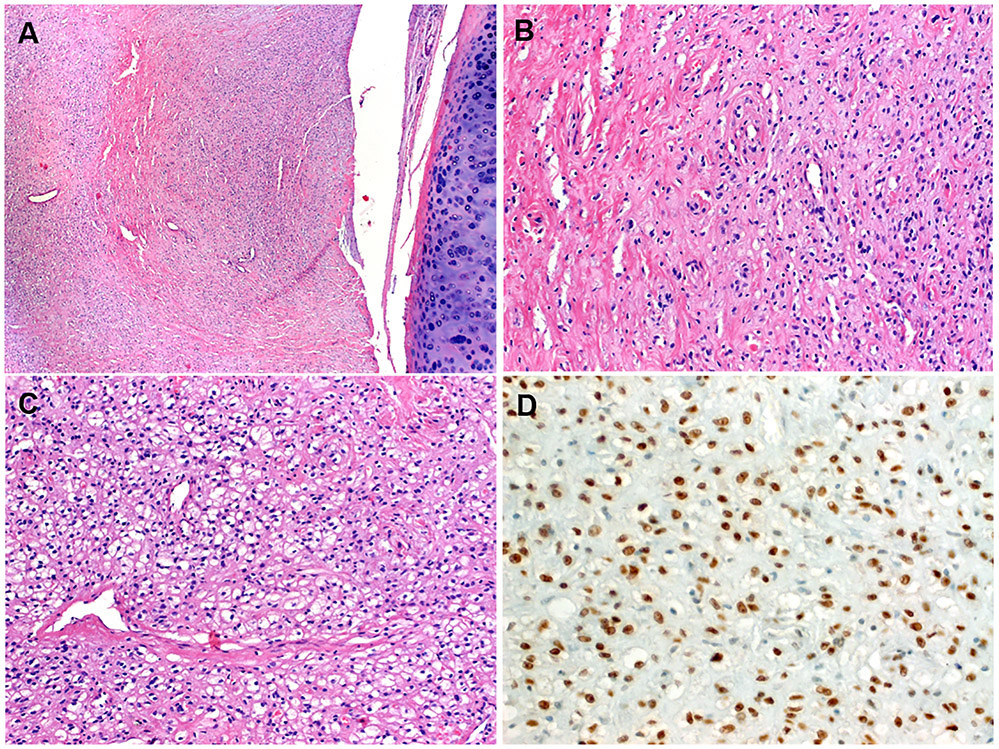

FIGURE 7.

The fusion-negative case showed endobronchial location (A) and a variably collagenized (B) to sparse (C) stroma. The cells had predominantly well-defined borders and clear cell (C); note scattered hyalinized or thin-walled vessels. TFE3 immunoreactivity comparable to other cases was observed in this tumor which lacked a fusion by NGS testing (D).

DISCUSSION

Hemangioblastoma is characterized by specific morphological, immunophenotypic and genetic features that permit their identification at unusual or unexpected sites and separation form their mimics. The majority of conventional hemangioblastomas, both central and peripheral, are positive for vimentin, NSE, inhibin and S-100.1-3 Molecular analysis of extra-neuraxial and peripheral cases revealed vhl alterations in a subset of cases, either as germline or acquired somatic mutations.11,12

The lesions reported by Falconieri et al (n=2)6, Lindholm and Moran (n=5)5 and those we are presenting herein (n=4) as clear cell stromal tumors of the lung (CCST-L) share clinicopathological, histological and immunophenotypic features, but appear distinct from conventional hemangioblastoma, despite some morphological similarities. In contrast to genuine hemangioblastomas, which consistently express S100, NSE, inhibin and vimentin, CCST-L expresses only vimentin, but not these markers.1-3,5,6 In addition, none of reported cases of CCST-L had clinical evidence of VHL.5,6 Critical assessment of the current lesions showed significant differences from conventional hemangioblastoma, in particular at the cytological level. Indeed, the vascular stroma and the variable cytoplasmic clearing seem to be the only morphological features shared by these distinctive pulmonary lesions and hemangioblastoma. The CCST-L tends to have medium-sized cells that lack the copious cytoplasm seen in the majority of genuine hemangioblastoma. Moreover, the xanthomatous lipid-rich clear cell quality is more striking in conventional hemangioblastoma and is only subtle in CCST-L, being appreciated focally at high power. Instead, a faint cytoplasmic granularity and flocculent appearance are observed in the cells of CCST-L. Moreover, the variable cytoplasmic clearing of CCST-L is likely due to prominent glycogen deposits or other cytopathic changes and not a consequence of mere lipid accumulation as seen in conventional hemangioblastoma. Consistent with recent reports, our CCST-L cases showed a distinct solid and nested growth pattern within a vascularized stroma. Focal areas of hyalinization were seen, as well as ischemic-type necrosis, but coagulative-type necrosis, increased mitotic activity or significant cytological atypia are absent. Although available follow-up revealed a benign course in the few reported CCST-L cases5,6, we herein document metastatic potential in one case with biopsy-proven multiple synchronous liver and kidney metastases.

To our knowledge, none of the presumable pulmonary “true hemangioblastomas” or the recently proposed CCST-L have been subjected to RNA-based testing for oncogenic gene fusions before. We have tested our initial “index” case, thought to represent a pulmonary PEComa (due to prominent TFE3 immunoreactivity and the clear cell morphology), but otherwise non-specific immunoprofile and a YAP1-TFE3 fusion was detected. The second case was investigated due to striking similarity with the index case and the prominent TFE3 reactivity. The third case was submitted in consultation with the main consideration of a GLI1-fusion positive neoplasm and subjected to targeted RNA sequencing, when a YAP1-TFE3 fusion was detected. This latter result was subsequently confirmed by FISH and also by diffuse expression of TFE3 at protein level. Taken together, 3 of the 4 cases tested had the YAP1-TFE3 fusion, including the clinically malignant case. Notably, the fusion-negative case showed TFE3 expression that is comparable to the reactivity seen in the fusion-positive cases suggesting possible activation or overexpression via other unknown mechanisms. A thorough search of our routine and consultation files revealed several PEComas, but no additional potential cases of CCST-L or hemangioblastomas could be detected, highlighting the rarity of this tumor. Notably, a subset of the pulmonary PEComas were tested with TFE3 immunohistochemistry and were negative; one case was also tested with same RNA Panel and had no fusion (data not shown).

With increasing use of NGS, the TFE3 fusion family of neoplasms has been continuously expanding to include MiTF-associated renal cell carcinoma13, alveolar soft part sarcoma14, and subsets of PEComas.15,16 Although several different TFE3 fusion partners have been identified in different TFE3-rerranged neoplastic entities with variable phenotypic-genotypic correlations in some of them13-16, the YAP1-TFE3 fusion has been only described in a rare subset of epithelioid hemangioendothelioma (EHE) lacking the classical WWTR1-CAMTA1 fusion.10 Compared to the common WWTR1-CAMTA1-positive counterpart, YAP1-TFE3-rearranged EHE has distinct morphology, with well-formed vessels and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm.10,17 All TFE3-rearranged EHE expressed endothelial markers in addition to a strong nuclear TFE3 reactivity.10 However, this rare EHE subset shares a similar clinical presentation with the classic EHE with WWTR1-CAMTA1 fusion.10,17 Our current cases and those recently reported similar cases of CCST-L have been negative for all endothelial markers and lacked the typical morphology of the YAP1-TFE3-rearranged EHE.5,6,10

The identification of recurrent YAP1-TFE3 gene fusion in three of our four cases and associated with diffuse TFE3 overexpression are in keeping with TFE3 oncogenic activation secondary to gene rearrangements, which is distinct from the peripheral (visceral) hemangioblastoma pathogenesis. The common feature of all TFE3 fusion proteins is preservation of the bHLH-LZ and transcriptional activation domains of TFE3, which is also the case in the current study group as well as EHE harboring YAP1-TFE3 fusion.10,17 YAP1 represents a transcriptional co-activator downstream of the Hippo pathway, likely providing a strong promoter for the oncogenic activation of TFE3.

The diagnostic value of TFE3 IHC in screening for YAP1-TFE3 fusions in putative pulmonary hemangioblastomas and related tumors remains to be determined. Some controversy remains around the use of TFE3 IHC as surrogate for TFE3 gene fusions in routine practice. This is mainly due to the fact that a variety of non-TFE3-altered neoplasms may variably express the wildtype TFE3.18,19 One study comparing two different TFE3 antibodies tested in two laboratories showed an overall sensitivity and specificity of TFE3 IHC as surrogate for TFE3-rearrangements of 85% and 57% in one Laboratory and 70% and 95% in the other.18 However, as TFE3 represents a transcript product of the TFE3 fusions and not a differentiation marker, an approach similar to other molecular antibodies (e.g. TP53, etc.) is mandatory to avoid overinterpretation of variable reactivity with the wildtype TFE3 observed in several neoplasms lacking the TFE3 fusions. Neoplasms with oncogenic TFE3 fusions frequently display aberrant reactivity pattern (strong, diffuse and homogeneous staining in all tumor cells that is comparable to the onslide control) as opposed to the wildtype pattern (usually highly heterogeneous and variable compared to the control). In our experience with different TFE3-related entities, the “aberrant” expression pattern highly correlates with the presence of a TFE3 fusion. However, we observed diffuse expression in the one case that lacked the fusion in the current study, suggesting that alternative TFE3 activation mechanisms might be responsible for this case, but this remains speculative. Notably, this fusion-negative case lacked TFE3 rearrangements and amplification by FISH, and, instead, revealed a STED2 mutation by next generation sequencing.

The most relevant differential diagnosis of CCST-L is intrapulmonary primary or metastatic hemangioblastoma, which has been discussed above in detail. Primary pulmonary PEComa (“clear cell sugar tumor”20) and, in particular, late solitary metastasis from genitourinary and other PEComas21 are entities that might be closely similar to CCST-L. These tumors, however, can be ruled out based on their immunoreactivity with the melanocytic markers (HMB45) and Cathepsin K.20,22 Based on TFE3 immunoexpression, primary pulmonary or metastatic alveolar soft part sarcoma23 and TFE3-rerranged EHE10 should be ruled out. However, these entities are readily distinguishable from CCST-L on morphologic grounds. In addition, well vascularized epithelioid lesions such as carcinoid tumor and paraganglioma are all readily excluded by their conventional histological and immunophenotypic features. Notably, CCST-L lacks reactivity with pankeratin and neuroendocrine markers.5,6 Another important differential to be ruled out is metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma (pankeratin+ /PAX8+). Focal entrapment of regenerative alveolar epithelium within CCST-L might be misinterpreted as evidence of epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma. However, lack of myoepithelial and epithelial markers in CCST-L rules out this consideration. Finally, intrapulmonary solitary fibrous tumor could be ruled out by negativity for CD34 and STAT6.

In summary, we herein describe four new cases of clear cell stromal tumor of the lung (CCST-L) bringing up the total number of reported cases to 11. We demonstrated for the first time that a significant number of these tumors are driven by oncogenic novel YAP1-TFE3 fusions. These observations further underline the distinctness of CCST-L from conventional hemangioblastoma, with which they have likely been confused in the past. Our study adds to the expanding family of TFE3-related neoplasms and represents a novel contribution to the YAP1-TFE3-rearranged subgroup. The biology of these tumors cannot be predicted from our few cases, but they seem to possess a malignant potential at least in a subset of the cases. Future molecular analysis of reported visceral hemangioblastomas from different organs should address the justified question, whether pulmonary-type CCST does exist in other organs.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Supported in part by: P50 CA217694 (CRA), P50 CA140146 (CRA), P30 CA008748 (CRA), Cycle for Survival (CRA).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none

REFERENCES

- 1.Bisceglia M, Muscarella LA, Galliani CA, Zidar N, Ben-Dor D, Pasquinelli G, la Torre A, Sparaneo A, Fanburg-Smith JC, Lamovec J, Michal M, Bacchi CE. Extraneuraxial Hemangioblastoma: Clinicopathologic Features and Review of the Literature. Adv Anat Pathol. 2018;25:197–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michal M, Vanecek T, Sima R, et al. Primary capillary hemangioblastoma of peripheral soft tissues. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:962–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doyle LA, Fletcher CD. Peripheral hemangioblastoma: clinicopathologic characterization in a series of 22 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2014;38:119–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abbott KH, Love JG. Metastasizing intracranial tumors. Ann Surg. 1943;118:343–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindholm KE, Moran CA. Hemangioblastoma-like Clear Cell Stromal Tumor of the Lung: A Clinicopathologic and Immunohistochemical Study of 5 Cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020;44:771–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falconieri G, Mirra M, Michal M, Suster S. Hemangioblastoma-like clear cell stromal tumor of the lung. Adv Anat Pathol 2013;20:130–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdóttir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, Mesirov JP. Integrative Genomics Viewer. Nature Biotechnology 2011;29:24–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng Z, Liebers M, Zhelyazkova B, Cao Y, Panditi D, Lynch KD, Chen J, Robinson HE, Shim HS, Chmielecki J, Pao W, Engelman JA, Iafrate AJ, Le LP. Anchored multiplex PCR for targeted next-generation sequencing. Nat Med. 2014;20:1479–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu G, Benayed R, Ho C, Mullaney K, Sukhadia P, Rios K, Berry R, Rubin BP, Nafa K, Wang L, Klimstra DS, Ladanyi M, Hameed MR. Diagnosis of known sarcoma fusions and novel fusion partners by targeted RNA sequencing with identification of a recurrent ACTB-FOSB fusion in pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma. Mod Pathol. 2019;32:609–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Antonescu CR, Le Loarer F, Mosquera JM, Sboner A, Zhang L, Chen CL, Chen HW, Pathan N, Krausz T, Dickson BC, Weinreb I, Rubin MA, Hameed M, Fletcher CD. Novel YAP1-TFE3 fusion defines a distinct subset of epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2013;52:775–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muscarella LA, Bisceglia M, Galliani CA, Zidar N, Ben-Dor DJ, Pasquinelli G, la Torre A, Sparaneo A, Fanburg-Smith JC, Lamovec J, Michal M, Bacchi CE. Extraneuraxial hemangioblastoma: A clinicopathologic study of 10 cases with molecular analysis of the VHL gene. Pathol Res Pract. 2018;214:1156–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Segawa K, Sugita S, Aoyama T, Minami S, Nagashima K, Tsuda M, Tanaka S, Hasegawa T. Detection of VHL deletion by fluorescence in situ hybridization in extraneuraxial hemangioblastoma of soft tissue. Pathol Int 2020;70:473–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Argani P, Zhong M, Reuter VE, Fallon JT, Epstein JI, Netto GJ, Antonescu CR. TFE3-Fusion Variant Analysis Defines Specific Clinicopathologic Associations Among Xp11 Translocation Cancers. Am J Surg Pathol 2016;40:723–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dickson BC, Chung CT, Hurlbut DJ, Marrano P, Shago M, Sung YS, Swanson D, Zhang L, Antonescu CR. Genetic diversity in alveolar soft part sarcoma: A subset contain variant fusion genes, highlighting broader molecular kinship with other MiT family tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2019. August 21: 10.1002/gcc.22803. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Argani P, Aulmann S, Illei PB, Netto GJ, Ro J, Cho HY, Dogan S, Ladanyi M, Martignoni G, Goldblum JR, Weiss SW. A distinctive subset of PEComas harbors TFE3 gene fusions. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1395–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agaram NP, Sung YS, Zhang L, Chen CL, Chen HW, Singer S, Dickson MA, Berger MF, Antonescu CR. Dichotomy of Genetic Abnormalities in PEComas With Therapeutic Implications. Am J Surg Pathol 2015;39:813–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenbaum E, Jadeja B, Xu B, Zhang L, Agaram NP, Travis W, Singer S, Tap WD, Antonescu CR. Prognostic stratification of clinical and molecular epithelioid hemangioendothelioma subsets. Mod Pathol. 2020;33:591–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharain RF, Gown AM, Greipp PT, Folpe AL. Immunohistochemistry for TFE3 lacks specificity and sensitivity in the diagnosis of TFE3-rearranged neoplasms: a comparative, 2-laboratory study. Hum Pathol 2019;87:65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flucke U, Vogels RJ, de Saint Aubain Somerhausen N, Creytens DH, Riedl RG, van Gorp JM, Milne AN, Huysentruyt CJ, Verdijk MA, van Asseldonk MM, Suurmeijer AJ, Bras J, Palmedo G, Groenen PJ, Mentzel T. Epithelioid Hemangioendothelioma: clinicopathologic, immunhistochemical, and molecular genetic analysis of 39 cases. Diagn Pathol. 2014;9:131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thway K, Fisher C. PEComa: morphology and genetics of a complex tumor family. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2015;19:359–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dimmler A, Seitz G, Hohenberger W, Kirchner T, Faller G. Late pulmonary metastasis in uterine PEComa. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:627–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caliò A, Mengoli MC, Cavazza A, Rossi G, Ghimenton C, Brunelli M, Pea M, Chilosi M, Marcolini L, Martignoni G. Cathepsin K expression in clear cell "sugar" tumor (PEComa) of the lung. Virchows Arch 2018;473:55–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao M, Rao Q, Wu C, Zhao Z, He X, Ru G. Alveolar soft part sarcoma of lung: report of a unique case with emphasis on diagnostic utility of molecular genetic analysis for TFE3 gene rearrangement and immunohistochemistry for TFE3 antigen expression. Diagn Pathol. 2015;10:160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]