Abstract

Background

One common denominator to the clinical phenotypes of borderline personality disorder (BPD) and major depressive disorder (MDD) is emotion regulation impairment. Although these two conditions have been extensively studied separately, it remains unclear whether their emotion regulation impairments are underpinned by shared or distinct neurobiological alterations.

Methods

We contrasted the neural correlates of negative emotion regulation across an adult sample of BPD patients (n = 19), MDD patients (n = 20), and healthy controls (HCs; n = 19). Emotion regulation was assessed using an established functional magnetic resonance imaging cognitive reappraisal paradigm. We assessed both task-related activations and modulations of interregional connectivity.

Results

When compared to HCs, patients with BPD and MDD displayed homologous decreased activation in the right ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (vlPFC) during cognitive reappraisal. In addition, the MDD group presented decreased activations in other prefrontal areas (i.e., left dorsolateral and bilateral orbitofrontal cortices), while the BPD group was characterized by a more extended pattern of alteration in the connectivity between the vlPFC and cortices of the visual ventral stream during reappraisal.

Conclusions

This study identified, for the first time, a shared neurobiological contributor to emotion regulation deficits in MDD and BPD characterized by decreased vlPFC activity, although we also observed disorder-specific alterations. In MDD, results suggest a primary deficit in the strength of prefrontal activations, while BPD is better defined by connectivity disruptions between the vlPFC and temporal emotion processing regions. These findings substantiate, in neurobiological terms, the different profiles of emotion regulation alterations observed in these disorders.

Keywords: Borderline personality disorder, emotion regulation, fMRI, major depressive disorder, neuroimaging

Introduction

Emotion is a complex and multifaceted process that involves different evaluative components, including appraisal processes evaluating the meaning and relevance of actual or imagined events [1]. These appraisals may be consciously modulated to regulate emotions, such as during the reappraisal of negative emotions to neutral or positive terms. The ability to carry out this process is an important factor for determining well-being and the presence of psychopathology [2,3]. One way to modulate such emotion appraisals is via cognitive reappraisal, an antecedent-focused cognitive control strategy that allows reframing emotion-inducing stimuli or scenarios in positive terms, which leads to decreased sympathetic activity and negative affect, better interpersonal functioning, and increased physical and psychological well-being [4].

In neurobiological terms, emotion regulation is characteristically implemented by the circuits linking different regions of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) with subcortical structures, such as the amygdala, related to emotional responding [5–7]. More specifically, regulatory input to subcortical structures is assumed to be mediated by activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) and orbitofrontal cortices (OFCs), with recent evidence supporting that disturbances in these circuits are associated with emotion regulation behavior [8,9]. Moreover, other PFC regions, such as the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (vlPFC), have been shown to be implicated in selecting goal-appropriate responses and retrieving information from semantic memory, which can then be used to develop new appraisals [3,10].

Several studies have demonstrated that patients with psychiatric disorders have difficulties in using cognitive reappraisal [11], although the mechanisms of alteration may differ across conditions. Alterations in emotion regulation are central to both major depressive disorder (MDD) and borderline personality disorder (BPD); however, they may be underpinned by different pathological mechanisms. First, individuals with BPD show fluctuations in subcortical system functioning, which results in failure to habituate and hypersensitivity to threat cues [12,13]. Importantly, this has been suggested to underlie several of the pathological manifestations of this disorder, including affective instability, intense and tumultuous relationships, difficulty controlling anger, impulsivity, suicidal tendencies, and deliberate self-harm (thought to serve an emotion-regulating function) [14,15]. Patients with MDD, in contrast, present a distinctive clinical profile, and portray cognitive impairments related to basic elements of emotional processing [16]. These have been linked to decreased prefrontal recruitment during the explicit voluntary control of emotions [17]. Nevertheless, such putatively distinct neurobiological mechanisms of altered emotion regulation have not been directly compared. This comparison may be, however, of great interest not only to further understand the different mechanisms of psychological maladjustment in BPD and MDD, but also to develop disorder-specific approaches to improve emotion regulation capacity.

The present study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first to investigate the neurobiological underpinnings of disrupted emotion regulation in MDD and BPD using a cognitive reappraisal paradigm and the concurrent evaluation of regional brain activity with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Moreover, given the central role of interregional connectivity alterations in neurobiological models of emotion regulation, we decided to not only assess task-related activations, but also task-modulations of interregional connectivity. We hypothesized that both MDD and BPD groups would differ from health controls (HCs) in measures of brain activity and connectivity during cognitive reappraisal. More specifically, we hypothesized that patients with BPD would show increased subcortical activations related to inefficient regulatory input from prefrontal areas, while patients with MDD would present reduced recruitment of prefrontal areas during cognitive reappraisal. Finally, we also anticipated that these neurobiological alterations would be correlated to core clinical measurements in both patient groups.

Methods

Sample

The study included three groups of participants: patients with BPD (n = 19), patients with MDD (n = 20), and HCs (n = 19), which were recruited at Fundación Lucha contra las Enfermedades Neurológicas en la Infancia (FLENI Foundation) in Buenos Aires, Argentina. The groups consisted of 19 males and 39 females, ranging from 21 to 63 years of age (mean = 41.26; SD = 13.11). Patients were consecutively recruited when attending the Department of Psychiatry at FLENI Foundation if they met DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for BPD or MDD. All participants were evaluated via a clinical interview in order to confirm their DSM-5 diagnosis (patients) or the absence of any present or past diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder (HCs). Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic and clinical features of the study participants. As can be seen in this table, mean Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) scores indicated that most patients with MDD were in remission at the time of study. Specifically, 65% of patients with MDD, and also 68% of patients with BPD, scored below the 7-point cutoff value for depression, and, therefore, results of this study should be considered as related to stable depression features more than to transient alterations related to fluctuations in mood state. Further information regarding the sample and exclusion criteria can be found in the Supplementary Material.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study group.

| Sample | HCs (n = 19) | BPD (n = 19) | MDD (n = 20) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | N(%) | N(%) | N(%) |

| Female | 15(79) | 10(53) | 14(70) |

| (Mean ± SD) | (Mean ± SD) | (Mean ± SD) | |

| Age | 35.84 ± 10.38 | 37.68 ± 11.25^ | 49.80 ± 13.24°^ |

| Psychometric evaluations | |||

| CERQ reappraisal a | 10.37 ± 4.57 | 8.32 ± 4.74 | 8.00 ± 3.65 |

| CERQ rumination a | 8.89 ± 3.16 | 9.74 ± 2.60 | 9.65 ± 3.11 |

| DERS total | 58.21 ± 15.10 | 96.95 ± 33.05* | 89.15 ± 21.88° |

| HDRS total | 0.16 ± 0.68 | 5.58 ± 5.80* | 6.70 ± 6.35° |

| HARS total | 0.68 ± 1.63 | 9.89 ± 9.27* | 5.40 ± 4.10 |

Notes: Symbol references for significant pair-wise between-group differences: *HC–BPD; °HC–MDD; ^BPD–MDD.

Abbreviations: BPD, borderline personality disorder; CERQ, Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire; DERS, Difficulties in Emotion Regulation; HARS, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; HCs, healthy controls; HDRS, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; MDD, major depressive disorder.

Although no across-group differences were observed in these variables, in clinical groups, these values significantly differed (one-sample t-tests) from those obtained in a population of nondepressed older adults [18]: CERQ reappraisal (lower values in clinical groups), HCs: p = 0.882 (n.s.), BPD: p = 0.098 (trend-level), MDD: p = 0.017; CERQ rumination (higher values in all groups), HCs: p = 0.019, BPD: p < 0.0005, MDD: p = 0.001.

The present study was carried out in accordance with the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee in clinical research of FLENI Foundation approved the study. Signed informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Psychometric assessment

All participants completed the validated Spanish versions of the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ) and the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) to evaluate emotion dysregulation. Likewise, all subjects also completed the HDRS and the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HARS) to assess severity of depression and anxiety symptoms, respectively [18–24].

MRI acquisition

This information can be found in the Supplementary Material.

fMRI task, cognitive reappraisal paradigm

We used a well-validated paradigm to evaluate brain activations during emotion regulation with fMRI using negative images and in-scanner behavioral ratings [6,25]. Picture stimuli were obtained from the International Affective Picture System [26]. The task consisted of three conditions (“observe,” “maintain,” and “regulate”) presented in an ABC design with four blocks per condition (i.e., a total of 12 blocks). An additional description of the task is detailed in the Supplementary Material. Like in most previous research, participants were instructed to use distancing or reinterpretation as reappraisal strategies. These are two antecedent-focused strategies acting before emotional responses have been completely generated. The former refers to rationalizing the content of a situation by adopting the perspective of an uninvolved observer, while the latter refers to changing the meaning of stimuli in order to view the outcome of a situation in a more positive light [27]. All blocks consisted of two consecutive images (each image was presented on screen for 10 s, with no interstimulus interval), and each block was followed by 10s of baseline during which a cross fixation was presented on the screen to minimize carryover effects [28].

fMRI preprocessing and analysis

A thorough description of this section can be found in the Supplementary Material.

Results

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are displayed in Table 1. Because patients were consecutively recruited, groups significantly differed in age (patients with MDD were older). For this reason, age was introduced as a nuisance covariate in all analyses.

Intrascanner ratings

Overall, in-scanner emotion ratings were the highest during the maintain blocks (mean = 3.08; SD = 0.89), followed by regulate (mean = 2.56; SD = 0.90) and observe (mean = 1.860; SD = 0.99) blocks (F = 4.30; p = 0.02). We did not observe, however, significant across-group differences or a group × condition interaction in these ratings.

fMRI task-related activations

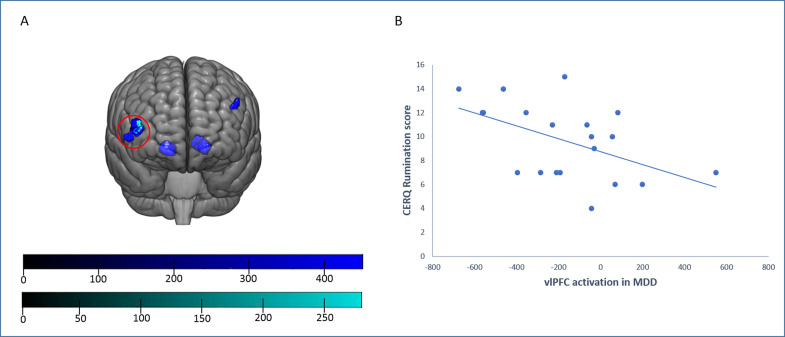

In the regulate versus maintain contrast, a direct between-group comparison showed that when compared to HCs, individuals within the BPD and MDD groups presented overlapping decreased activations in the right vlPFC during cognitive reappraisal. In addition, patients with MDD, also in comparison to HCs, showed decreased activations in the left dlPFC and in the bilateral OFC (Figure 1A and Table 2). These results remained significant when controlling for sex in addition to age (Supplementary Table 1). Moreover, we observe no significant across-group differences during the Maintain > Observe contrast, although we observed a significant (at an uncorrected level) across-group activation in the right amygdala in this contrast, indicating successful emotion induction (Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Figure 1). Interestingly, in the Maintain > Observe contrast, we also observed that both patient groups tended to activate the vlPFC and the bilateral OFC more than HCs during the maintain condition, although at an uncorrected significance level (Supplementary Table 3).

Figure 1.

Between-group differences in task-related activations. (A) Patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD; cyan) and patients with major depressive disorder (MDD; blue) showed overlapping decreased activations in comparison to healthy controls (HCs) during emotion regulation in the right ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (vlPFC; red circle). Patients with MDD showed additional hypoactivation in the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the orbitofrontal cortex (bilaterally). Top color bar: MDD versus HC TFCE (Threshold Free Cluster Enhancement) values; bottom color bar: BPD versus HC TFCE (Threshold Free Cluster Enhancement) values. (B) Correlation between Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire rumination scores and right vlPFC activation in patients with MDD.

Table 2.

Regions showing significant activation differences during Regulate > Maintain.

| Activations: Regulate > Maintain | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contrast | Anatomical area | MNI coordinates | kE | P FWE | ||

| x | y | z | ||||

| HCs > BPD | Right vlPFC | 45 | 60 | 6 | 117 | 0.030 |

| HCs > MDD | Right vlPFC | 47 | 56 | 8 | 393 | 0.008 |

| Right OFC | 18 | 38 | −9 | 342 | 0.011 | |

| Left OFC | −17 | 42 | −9 | 443 | 0.011 | |

| Left dlPFC | −47 | 45 | 33 | 65 | 0.018 | |

Abbreviations: BPD, borderline personality disorder; dlPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; FWE, family-wise error; HCs, healthy controls; kE, cluster extent; MDD, major depressive disorder; MNI, Montreal Neurological Institute; OFC, orbitofrontal cortex; vlPFC, ventrolateral prefrontal cortex.

gPPI analyses

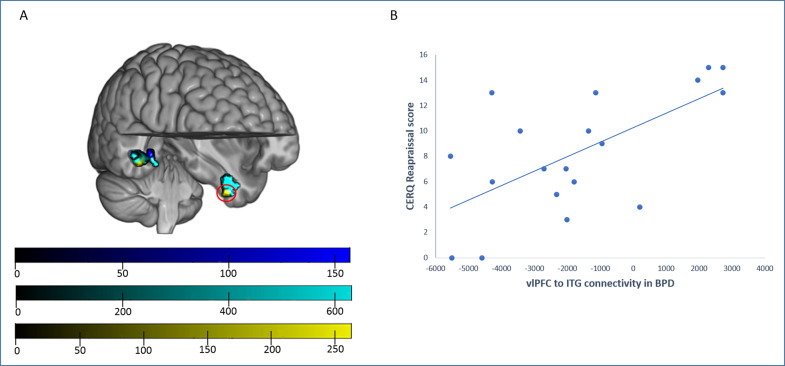

Generalized psychophysiological interactions (gPPIs) revealed between-group differences when assessing right vlPFC connectivity. Specifically, in comparison to HCs, individuals from both the BPD and MDD groups showed a similar pattern of reduced connectivity with right posterior temporal areas (although peak coordinates of the different group comparisons were located in different gyri, all these clusters overlapped in the posterior temporal cortex). Nevertheless, the BPD group showed an additional cluster of decreased connectivity with the right vlPFC involving the left inferior temporal cortex. In addition, when directly comparing both clinical groups, patients with BPD showed decreased connectivity values in comparison to patients with MDD within these same clusters (Figure 2A and Table 3).

Figure 2.

Between-group differences in generalized psychophysiological interaction (gPPI) analyses from the right vlPFC seed. (A) In comparison to healthy controls (HCs), patients with major depressive disorder (MDD; blue) showed a decreased connectivity with right posterior temporal areas, involving the medial temporal gyrus and the parahippocampal gyrus. Patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD; cyan) showed also decreased connectivity with posterior temporal areas (in this case, with peak differences in the fusiform gyrus) and, specific to these subjects, with the left inferior temporal gyrus (ITG). Moreover, patients with BPD showed, in comparison to the MDD group (yellow), decreased connectivity between the right vlPFC and the left ITG and the right fusiform gyrus. Top color bar: MDD versus HC TFCE (Threshold Free Cluster Enhancement) values; middle color bar; BPD versus HC TFCE (Threshold Free Cluster Enhancement) values; bottom color bar; BPD versus MDD TFCE (Threshold Free Cluster Enhancement) values. (B) The Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire reappraisal scores correlated positively with right vlPFC–left ITG connectivity (red circle) in the BPD group.

Table 3.

Regions showing significant connectivity differences during Regulate > Maintain.

| Connectivity (gPPI) ➔ vlPFC: Regulate > Maintain | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contrast | Anatomical area | MNI coordinates | kE | P FWE | ||

| x | y | z | ||||

| HC > BPD | Right posterior temporal cortex (peak at FG) | 48 | −36 | −14 | 475 | 0.001 |

| Left ITG | −39 | −9 | −33 | 364 | 0.002 | |

| HC > MDD | Right posterior temporal cortex (peak at PG) | 33 | −36 | −6 | 58 | 0.007 |

| Right posterior temporal cortex (peak at MTG) | 53 | −35 | −11 | 42 | 0.033 | |

| MDD > BPD | Right posterior temporal cortex (peak at FG) | 45 | −45 | −8 | 161 | 0.009 |

| Left ITG | −35 | −9 | −39 | 54 | 0.024 | |

Abbreviations: BPD, borderline personality disorder; FG, fusiform gyrus; FWE, family-wise error; gPPI, generalized psychophysiological interaction; HCs, healthy controls; ITG, inferior temporal gyrus; kE, cluster extent; MDD, major depressive disorder; MNI, Montreal Neurological Institute; MTG, medial temporal gyrus; PG, parahippocampal gyrus; vlPFC, ventrolateral prefrontal cortex.

Correlations between clinical and imaging data

We observed a significant negative correlation between right vlPFC activation and CERQ rumination scores in the MDD group (Pearson’s r = −0.505; p = 0.023; Figure 1B), which significantly differed (z = −1.881; p = 0.03) from the same correlation in the BPD group (Pearson’s r = 0.099; p = 0.686). Nevertheless, the difference with the correlation in HCs (Pearson’s r = −0.22; p = 0.365) did not reach statistical significance (z = −0.954; p = 0.17). Furthermore, we observed that patients with BPD showed a significant positive correlation between CERQ reappraisal scores and right vlPFC–left inferior temporal gyrus (ITG) connectivity (Pearson’s r = 0.644; p = 0.003; Figure 2B). This correlation differed from what was observed in MDD (Pearson’s r = 0.004; p = 0.986) and HC (Pearson’s r = −0.112; p = 0.648) groups (z = −2.208; p = 0.014; and z = −1.846; p = 0.032, respectively). We found no further correlations between clinical and imaging data, including depression (HDRS) and anxiety (HARS) scores.

Discussion

Our results showed that both individuals with MDD and individuals with BPD display decreased activation in the vlPFC during cognitive reappraisal. Nevertheless, such hypoactivation was more extensive in the MDD group, who also showed a negative correlation between reappraisal-related vlPFC activity and rumination. Likewise, patients with MDD displayed other clusters of significant hypoactivation during cognitive reappraisal, including the left dlPFC and the bilateral OFC. Conversely, patients with BPD showed greater connectivity decreases between the vlPFC and left inferior and right posterior temporal regions during reappraisal. Furthermore, these connectivity alterations were significantly associated with psychometric measures of cognitive reappraisal. Overall, this pattern of results confirms our a priori hypotheses, since patients with MDD seem to recruit prefrontal regions to a lesser extent during regulation of emotions, while the BPD group displayed inefficient regulatory input from prefrontal areas.

Our findings reporting decreased vlPFC activation during emotional processing in both patient groups are in agreement with previous research [29]. The vlPFC plays a crucial role in response selection and inhibition [30], and, in particular, in the inhibition of emotional appraisals [31]. Our present results are, therefore, indicative of cognitive reappraisal impairments in MDD and BPD that may be partly a consequence of ineffective management of inhibitory resources. Notably, the vlPFC has been related to the use of reinterpretation strategies during reappraisal, as opposed to the use of distancing strategies engaging parietal regions [7,32]. Consequently, MDD and BPD seem to share a diminished capacity to reinterpret negative emotions. Moreover, among MDDs, decreased vlPFC activation was inversely related to rumination scores, a core feature of the depression phenotype. This concurs with reports in HC samples [33] and other findings indicating that the lateral PFC plays a general inhibitory role limiting the impact, or carryover effects, of an emotional state onto emotional states evoked by subsequent events [34]. On the other hand, the lateralization of this finding to the right hemisphere is in agreement with previous reports in MDD [35] and BPD [36] samples, although not with recent meta-analytic evidence in anxiety and depression groups [7]. The recruitment of the right vlPFC has been associated with particular features of cognitive reappraisal, such as reiteratively implementing the same reappraisal strategies to counteract negative affect [37], or the implementation of operations needed to maintain strategies in working memory and to monitor its success during the late phases of emotional situations [38]. Therefore, the right hemisphere lateralization of findings observed here may stem as a consequence of the specific instructions given to participants in this study, whom may have probably implemented a limited choice of strategies, in interaction with a decreased capacity in the maintenance and monitoring of ongoing reappraisal efforts in patients.

Decreased activation of the dlPFC has been also previously reported in clinical samples, including not only depression and anxiety patients [11,39]. This region contributes to different executive functions [40], and, in the context of emotion regulation, its role seems to be related to the active manipulation of information to reappraise emotional stimuli [32]. This alteration concurs with the executive function alterations commonly described in depression samples [41]. In this case, however, findings were lateralized to the left hemisphere. This may be partially accounted for by the role of right dlPFC activation in negative emotion appraisal, which is related to depression severity and may, therefore, compensate for the executive function-related hypoactivations allegedly occurring during reappraisal [6,42].

Regarding the hypoactivations also observed in the medial OFC in patients with MDD, it should be noted that this region, like other medial prefrontal structures, has been shown to downregulate activity in subcortical structures [9], and, indeed, its functional connectivity with the amygdala is increased during threat-induced anxiety in HCs [43]. According to our findings, the medial OFC of patients with MDD is probably not properly exerting this downregulatory input into emotion-processing structures, including, but not limited to, the amygdala [7,9]. In addition, it is important to note that both the OFC and the vlPFC showed a trend to increase activation in patient groups during the Maintain condition (as compared to the control Observe condition). This result suggests that patients engage in a regulation effort during the Maintain condition, which may also contribute to the decreased activation levels in these same regions (especially in the MDD group) observed when contrasting Regulate and Maintain conditions.

Patients with BPD did, however, not show such extended prefrontal hypoactivation, but rather decreased functional connectivity between the vlPFC and visual association cortices of the ventral stream, implicated in complex visual feature detection and recognition of facial expression [44]. Different studies have consistently described hyperresponsiveness of the visual system in BPD patients when processing emotional information, especially, emotional faces, extending from primary cortices to association cortices of the temporal lobe [29,45–48]. Although we here have not observed such increased activation in the visual system, the regulatory input from the vlPFC cortex was diminished in patients with BPD, which seems to be a plausible mechanism to account for the visual hyperresponse described with other emotional tasks in the above studies. Likewise, although patients with MDD also showed some degree of decreased connectivity from the vlPFC to early visual perception areas, their clusters were less extended, and, at least for some of these clusters (i.e., right posterior fusiform gyrus), we also observed a significant difference between the clinical groups, with MDD patients showing significant connectivity increases in comparison to the BPD group.

According to these results, it can be concluded that alterations in cognitive reappraisal in patients with BPD (and to a lesser extent, in patients with MDD) could start at perceptive stages, before information reaches emotion-processing structures. Nevertheless, since information is conveyed from these visual association to limbic cortices [49,50], it is expected that such (lack of) modulation of perceptive input will indirectly weaken the regulatory input from prefrontal structures to emotion-processing regions. In this sense, it is worth mentioning that only patients with BPD, but not patients with MDD, showed decreased connectivity between the vlPFC and more rostral parts of the ITG. It can, therefore, be suggested that as information progresses through the ventral stream, alterations in prefrontal modulation of visuo-emotional processing are exclusively observed in patients with BPD. Interestingly, alterations in the white matter tracts linking anterior brain areas with visual association cortices (i.e., the inferior fronto-occipital and the inferior longitudinal fasciculi) have been described in patients with BPD [51].

Overall, the above notions concur with recent reports suggesting that, in comparison to patients with MDD, patients with BPD show an exaggerated response during emotional induction paradigms [52]. It is also noteworthy that correlations between interregional connectivity alterations and emotion regulation scores were only observed in patients with BPD. Specifically, we observed a positive association between reappraisal scores and vlPFC–rostral ITG connectivity, indicating that prefrontal input at this particular stage of visuo-emotional processing within the ventral stream may critically determine emotion regulation success in this clinical group. In sum, these prefrontovisual association connectivity alterations observed in BPD are likely to account for the increased sensitivity to emotional aspects of the environment [53] and the general higher sensitivity to emotional stimuli and slow return of emotional arousal to baseline that characterize patients with BPD [54].

Importantly, the correlations between imaging and psychometric data observed in the clinical groups should be interpreted with caution, because CERQ scores did not differ across the study groups (although they significantly differed from those of a reference population; see Table 1). Nevertheless, our findings suggest that the extent of alterations in vlPFC activation (patients with MDD) and vlPFC–rostral ITG connectivity (patients with BPD) seems to be preferentially accounting for, among all the emotion regulation facets, interpatient variability in rumination and reappraisal, respectively. Anyhow, these do not exclude that these same neurobiological changes may be also related, to a lesser extent, to other emotion regulation facets, and this is probably the reason why these imaging alterations are significant at the group level.

The results of this study have to be interpreted in the context of the following limitations. First, our overall sample was small (n = 58, with 19/20 subjects per group), which may have limited the power of our analyses to detect additional significant findings. Nonetheless, we would like to stress that our subjects were carefully recruited according to strict inclusion criteria, and we have obtained several significant differences between the study groups at a strict family-wise error threshold. Likewise, the sample size of our study is similar to sample sizes in most neuroimaging emotion regulation studies in MDD or BPD samples (see, e.g., the studies included in the reviews and meta-analyses by Sicorello and Schmahl [13], Rive et al. [17], or Picó-Pérez et al. [7]). We acknowledge, however, that there are some notable exceptions to this trend, such as the studies by van Zutphen et al. (n = 55 BPD patients) [55] and Silvers et al. (n = 60 BPD patients) [56]. Second, patients with MDD were older than the other two groups, although this is reflective of the clinical setting in which this study took place and adds external validity to our study. Moreover, we controlled for age in all our analyses. Anyhow, future studies should try to provide a more accurate matching across study groups. This is especially important when comparing clinical groups overlapping in clinically relevant variables such as depression or anxiety. Although our clinical groups did not differ in these variables, an accurate matching of nuisance factors is expected to provide clearer results and, consequently, allow drawing straightforward conclusions. Third, we observed no significant across-group differences in intrascanner ratings, although this is commonly observed in emotion regulation studies and should not be interpreted as evidence of similar cognitive reappraisal implementation [7]. Indeed, our groups differed from HCs in psychometric measurements of emotion regulation (i.e., DERS scores). Moreover, intrascanner ratings showed that negative emotion reactivity was successfully induced in all groups. There are, nevertheless, different reasons for this lack of between-group differences in intrascanner ratings, such as the inherent limitations of subjective behavioral assessments, social desirability effects, or impaired self-awareness of emotional experience, as suggested by Zilverstand, Parvaz, and Goldstein [57]. Finally, we did not collect any measure of BPD severity [58], and we assessed dispositional use of emotion regulation strategies with a retrospective self-report measure. Although previous research has shown that such measurements may significantly predict real-life outcomes, such as well-being and depressive symptomatology [4], future research can benefit from real-time and real-life approaches, such as ecological momentary assessments.

Taken together, our findings indicate that MDD and BPD share an altered neural response during cognitive reappraisal involving the right vlPFC, indicating that this region is implicated in the emotion regulation shortcomings that characterize both disorders. Nevertheless, MDD patients showed a more widespread pattern of reduced prefrontal activation, which may be interpreted in the context of a pervasive alteration in executive functioning probably stemming from a primary deficit in the strength of prefrontal activations. On the other hand, BPD patients showed a more extended pattern of dysfunctional connectivity between prefrontal areas and visual association cortices that may lead to the higher sensitivity to emotional stimuli typically observed in these patients. These findings substantiate in neurobiological terms the existence of dissimilar profiles of emotion regulation alteration between these disorders, and may ultimately be of relevance for the development or optimization of clinical interventions aimed at restoring emotion regulation capacities.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank CERCA Program/Generalitat de Catalunya for institutional support. We would also like to thank all the participants who contributed to this study.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.2231.

click here to view supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study and the brain maps of all analyses are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: X.G., N.C., S.M.G., and C.S.-M.; Data curation: X.G., S.M.G., and C.S.-M.; Formal analysis: V.D.P.-A., M.B.-S., and T.S.; Funding acquisition: J.M.M., S.M.G., and C.S.-M.; Investigation: V.D.P.-A., M.B.-S., X.G., A.W., and C.A.; Methodology: V.D.P.-A., M.B.-S., T.S., I.M.-Z., and A.W.; Project administration: S.M.G. and C.S.-M.; Resources: A.W., C.A., M.N.C., and M.V.; Software: I.M.-Z.; Supervision: N.C., M.N.C., M.V., S.M.G., and C.S.-M.; Validation: A.W., C.A., S.M.G., and C.S.-M.; Visualization: V.D.P.-A. and M.B.-S.; Writing & original draft: V.D.P.-A., S.M.G., and C.S.-M.; Writing, review, & editing: V.D.P.-A., M.B.-S., T.S., I.M.-Z., X.G., A.W., C.A., N.C., M.N.C., M.V., and J.M.M.

Financial Support

This project has received funding from the European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Sklowdowska Curie grant agreement No. 714673 and Fundación Bancaria “la Caixa.” This study was supported in part by grants PI16/00889 and PI19/01171 (Carlos III Health Institute, Spain), co-funded by European Regional Development Fund-ERDF, a way to build Europe, the Departament de Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya (PERIS SLT006/17/249), the Agència de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca (2017 SGR 1247), and the Agencia Nacional de Promoción de la Investigación, el Desarrollo Tecnológico y la Innovación PICT-2019-02328 (Argentina). V.D.P.-A. was supported by “la Caixa” Foundation (ID 100010434, fellowship code LCF/BQ/IN17/11620071). T.S. was supported by the University of Melbourne McKenzie Fellowship and an NHMRC/Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF) Investigator Grant (MRF1193736). I.M.-Z. was supported by a PFIS grant (FI17/00294) from the Carlos III health Institute. X.G. was supported by the Health Department of the Generalitat de Catalunya (SLT002/16/00237).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare none.

Ethical Standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

References

- [1]. Peil KT. Emotion: the self-regulatory sense. Glob Adv Health Med. 2014;3(2):80–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Aldao A, Gee D, De Los Reyes A, Seager I. Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic factor in the development of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology: current and future directions. Dev Psychopathol. 2016;28:927–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Thompson-Schill SL, Bedny M, Goldberg RF. The frontal lobes and the regulation of mental activity. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:219–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Gross JJ, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85:348–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Goldin PR, McRae K, Ramel W, Gross JJ. The neural bases of emotion regulation: reappraisal and suppression of negative emotion. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(6):577–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Phan KL, Fitzgerald DA, Nathan PJ, Moore GJ, Uhde TW, Tancer ME. Neural substrates for voluntary suppression of negative affect: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(3):210–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Picó-Pérez M, Radua J, Steward T, Menchón JM, Soriano-Mas C. Emotion regulation in mood and anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis of fMRI cognitive reappraisal studies. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2017;79(Pt B):96–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Scheuerecker J. Orbitofrontal volume reductions during emotion recognition in patients with major depression. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2010;35(5): 311–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9]. Steward T, Davey C, Jamieson A, Stephanou K, Soriano-Mas C, Felmingham K, Harrison B. Dynamic neural interactions supporting the cognitive reappraisal of emotion. Cereb Cortex. 2021;31:961–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Badre D, Wagner AD. Left ventrolateral prefrontal cortex and the cognitive control of memory. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:2883–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Campbell-Sills L, Ellard KK, Barlow DH. Emotion regulation in anxiety disorders. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation, New York: The Guilford Press; 2014, p. 393–412. [Google Scholar]

- [12]. Gunderson J, Herpertz S, Skodol A, Torgersen S, Zanarini M. Borderline personality disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:18029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13]. Sicorello M, Schmahl C. Emotion dysregulation in borderline personality disorder: a fronto–limbic imbalance?. Curr Opin Psychol. 2021;37:114–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Harford T, Chen C, Kerridge B, Grant B. Borderline personality disorder and violence toward self and others: a national study. J Pers Disord. 2019;33:653–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Schulze L, Domes G, Krüger A, Berger C, Fleischer M, Prehn K, et al. Neuronal correlates of cognitive reappraisal in borderline patients with affective instability. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:564–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]. Heinzel A, Northoff G, Boeker H, Boesiger P, Grimm S. Emotional processing and executive functions in major depressive disorder: dorsal prefrontal activity correlates with performance in the intra–extra dimensional set shift. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2010;22(6):269–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17]. Rive MM, van Rooijen G, Veltman DJ, Phillips ML, Schene AH, Ruhé HG. Neural correlates of dysfunctional emotion regulation in major depressive disorder. A systematic review of neuroimaging studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37(10):2529–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18]. Carvajal BP, Molina-Martínez MÁ, Fernández-Fernández V, Paniagua-Granados T, Lasa-Aristu A, Luque-Reca O. Psychometric properties of the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ) in Spanish older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2021;19:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Garnefski N, Kraaij V, Spinhoven P. Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation, and emotional problems. Pers Indivd Differ. 2001;30:1311–27. [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Domínguez-Sánchez FJ, Lasa-Aristu A, Amor PJ, Holgado-Tello FP. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire. Assessment. 2013;20(2):253–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959;32:50–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22]. Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23]. Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2004;26:41–54. [Google Scholar]

- [24]. Hervas G, Jodar R. The Spanish version of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Clin Salud. 2008;19:139–56. [Google Scholar]

- [25]. Albein-Urios N, Verdejo-Román J, Soriano-Mas C, Asensio S, Martínez-González J, Verdejo-García A. Cocaine users with comorbid cluster B personality disorders show dysfunctional brain activation and connectivity in the emotional regulation networks during negative emotion maintenance and reappraisal. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23:1698–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26]. Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN. International affective picture system (IAPS). Technical manual and affective ratings. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida, Center for Research in Psychophysiology; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- [27]. Dörfel D, Lamke JP, Hummel F, Wagner U, Erk S, Walter H. Common and differential neural networks of emotion regulation by detachment, reinterpretation, distraction, and expressive suppression: a comparative fMRI investigation. Neuroimage. 2014;101:298–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28]. Steward T, Picó-Pérez M, Mata F, Martínez-Zalacaín I, Cano M, Contreras-Rodríguez O, et al. Emotion regulation and excess weight: impaired affective processing characterized by dysfunctional insula activation and connectivity. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0152150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29]. Chechko N, Kellermann T, Augustin M, Zvyagintsev M, Schneider F, Habel U. Disorder-specific characteristics of borderline personality disorder with co-occurring depression and its comparison with major depression: an fMRI study with emotional interference task. Neuroimage Clin. 2016;12:517–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30]. Aron A, Robbins T, Poldrack R. Inhibition and the right inferior frontal cortex: one decade on. Trends Cog Sci. 2014;18:177–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31]. Wager T, Davidson M, Hughes B, Lindquist M, Ochsner K. Prefrontal-subcortical pathways mediating successful emotion regulation. Neuron. 2009;59:1037–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32]. Ochsner K, Silvers J, Buhle J. Functional imaging studies of emotion regulation: a synthetic review and evolving model of the cognitive control of emotion. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1251:E1–E24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33]. Hooker C, Gyurak A, Verosky S, Miyakawa A, Ayduk Ö. Neural activity to a partner’s facial expression predicts self-regulation after conflict. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:406–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34]. Waugh C, Shing E, Avery B, Jung Y, Whitlow C, Maldjian J. Neural predictors of emotional inertia in daily life. Soc Cog Affect Neurosci. 2017;12:1448–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35]. Bruder G, Alvarenga J, Abraham K, Skipper J, Warner V, Voyer D, et al. Brain laterality, depression and anxiety disorders: new findings for emotional and verbal dichotic listening in individuals at risk for depression. Laterality. 2015;21:525–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36]. Visintin E, De Panfilis C, Amore M, Balestrieri M, Wolf R, Sambataro F. Mapping the brain correlates of borderline personality disorder: a functional neuroimaging meta-analysis of resting state studies. J Affect Disord. 2016;204:262–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37]. Perchtold CM, Weiss EM, Rominger C, Fink A, Weber H, Papousek I. Cognitive reappraisal capacity mediates the relationship between prefrontal recruitment during reappraisal of anger-eliciting events and paranoia-proneness. Brain Cogn. 2019;132:108–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38]. Kalisch R. The functional neuroanatomy of reappraisal: time matters. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33(8):1215–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39]. Johnstone T, Walter H. The neural basis of emotion dysregulation. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. New York: The Guilford Press; 2014, p. 58–75. [Google Scholar]

- [40]. Wager T, Smith E. Neuroimaging studies of working memory. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2003;3(4):255–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41]. Rock P, Roiser J, Riedel W, Blackwell A. Cognitive impairment in depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2013;44:2029–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42]. Grimm S, Beck J, Schuepbach D, Hell D, Boesiger P, Bermpohl F, et al. Imbalance between left and right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in major depression is linked to negative emotional judgment: an fMRI study in severe major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:369–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43]. Gold A, Morey R, McCarthy G. Amygdala–prefrontal cortex functional connectivity during threat-induced anxiety and goal distraction. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;77(4):394–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44]. Im H, Albohn D, Steiner T, Cushing C, Adams R, Kveraga K. Differential hemispheric and visual stream contributions to ensemble coding of crowd emotion. Nat Hum Behav. 2017;1:828–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45]. Guitart-Masip M, Pascual J, Carmona S, Hoekzema E, Bergé D, Pérez V, et al. Neural correlates of impaired emotional discrimination in borderline personality disorder: an fMRI study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33(8):1537–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46]. Herpertz S, Dietrich T, Wenning B, Krings T, Erberich S, Willmes K, et al. Evidence of abnormal amygdala functioning in borderline personality disorder: a functional MRI study. Biol Psychiatry. 2001; 50: 292–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47]. Koenigsberg H, Siever L, Lee H, Pizzarello S, New A, Goodman M, et al. Neural correlates of emotion processing in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2009;172:192–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48]. Scherpiet S, Brühl A, Opialla S, Roth L, Jäncke L, Herwig U. Altered emotion processing circuits during the anticipation of emotional stimuli in women with borderline personality disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;264(1):45–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49]. Cardoner N, Harrison B, Pujol J, Soriano-Mas C, Hernández-Ribas R, López-Solá M, et al. Enhanced brain responsiveness during active emotional face processing in obsessive compulsive disorder. World J. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;12:349–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50]. Dolan R. Emotion, cognition, and behavior. Science. 2002;298:1191–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51]. Ninomiya T, Oshita H, Kawano Y, Goto C, Matsuhashi M, Masuda K, et al. Reduced white matter integrity in borderline personality disorder: a diffusion tensor imaging study. J Affect Disord. 2018;225:723–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52]. Schulze L, Schulze A, Renneberg B, Schmahl C, Niedtfeld I. Neural correlates of affective disturbances: a comparative meta-analysis of negative affect processing in borderline personality disorder, major depressive disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2019;4:220–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53]. Herpertz S, Gretzer A, Steinmeyer EM, Muehlbauer V, Schuerkens A, Sass H. Affective instability and impulsivity in personality disorder. Results Exp Study J Affect Disord. 1997;44(1):31–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54]. Johnson D, Shea M, Yen S, Battle C, Zlotnick C, Sanislow C, et al. Gender differences in borderline personality disorder: findings from the collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study. Compr Psychiatry. 2003;44:284–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55]. van Zutphen L, Siep N, Jacob GA, Domes G, Sprenger A, Willenborg B, et al. Always on guard: emotion regulation in women with borderline personality disorder compared to nonpatient controls and patients with cluster-C personality disorder. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2018;43(1):37–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56]. Silvers JA, Hubbard AD, Biggs E, Shu J, Fertuck E, Chaudhury S, et al. Affective lability and difficulties with regulation are differentially associated with amygdala and prefrontal response in women with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2016;254:74–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57]. Zilverstand A, Parvaz M, Goldstein R. Neuroimaging cognitive reappraisal in clinical populations to define neural targets for enhancing emotion regulation. A systematic review. Neuroimage. 2017;151:105–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58]. Pfohl B, Blum N, St John D, McCormick B, Allen J, Black DW. Reliability and validity of the borderline evaluation of severity over time (BEST): a self-rated scale to measure severity and change in persons with borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord. 2009;23(3):281–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.2231.

click here to view supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study and the brain maps of all analyses are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.