Abstract

During morphogenesis, molecular mechanisms that orchestrate biomechanical dynamics across cells remain unclear. Here, we show a role of guidance receptor Plexin-B2 in organizing actomyosin network and adhesion complexes during multicellular development of human embryonic stem cells and neuroprogenitor cells. Plexin-B2 manipulations affect actomyosin contractility, leading to changes in cell stiffness and cytoskeletal tension, as well as cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesion. We have delineated the functional domains of Plexin-B2, RAP1/2 effectors, and the signaling association with ERK1/2, calcium activation, and YAP mechanosensor, thus providing a mechanistic link between Plexin-B2-mediated cytoskeletal tension and stem cell physiology. Plexin-B2-deficient stem cells exhibit premature lineage commitment, and a balanced level of Plexin-B2 activity is critical for maintaining cytoarchitectural integrity of the developing neuroepithelium, as modeled in cerebral organoids. Our studies thus establish a significant function of Plexin-B2 in orchestrating cytoskeletal tension and cell-cell/cell-matrix adhesion, therefore solidifying the importance of collective cell mechanics in governing stem cell physiology and tissue morphogenesis.

Subject terms: Mechanotransduction, Actin, Neural stem cells, Embryonic stem cells

Biomechanical mechanisms orchestrating stem cell dynamics in development remain unclear. Here the authors show that guidance receptor Plexin-B2 organizes actomyosin contractility, cytoskeletal tension and adhesion during multicellular development of human embryonic stem cells and neuroprogenitor cells.

Introduction

The multicellular organization relies on biomechanical processes that mediate the generation, transmission, and sensing of mechanical force in cells1–3. For instance, during tissue morphogenesis, individual cells constantly rearrange against one another, which requires rapid cytoskeletal adjustment and establishment of a collective actomyosin network and adhesion complexes across cells in order to maintain cell morphology and tissue cohesion4,5. Cell-generated forces are transmitted through cell–cell junctions and focal adhesion sites at the interface between the cytoskeleton and extracellular matrix (ECM), which in turn provide important signals to inform cell fate decisions6. While a number of mechanotransduction pathways that enable cells to perceive and adapt to physical environment have been mapped1,7, the molecular mechanisms orchestrating collective cytoskeletal dynamics are less clear.

One informative example of multicellular dynamics is the self-assembly of cultured human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) into an epithelium-like colony, with stereotypical apical-basolateral polarization, E-cadherin-based adherens junctions, ZO-1-containing tight junctions, and integrin-based focal adhesions (FAs) at the interface between cytoskeleton and ECM8,9. During hESC colony formation, a network of cortical actomyosin is formed across cells in the colony interior, while continuous filamentous actin (F-actin) band emerges spanning multiple cells at the colony periphery. This leads to in-plane traction forces that are primarily localized at colony edges, as revealed by traction force microscopy6. Another example of complex mechanomorphogenesis is the process of neural tube closure and ventricle formation during neurodevelopment10. How hESCs and neuroprogenitor cells (NPCs) orchestrate cytoskeletal tension across cells and organize adhesion complexes at cell–cell and cell–matrix junctions to maintain cytoarchitectural integrity is incompletely understood.

Plexin-B2 is an axon guidance receptor widely expressed in the developing brain, in particular at the ventricular surface, supporting its role in regulating neuroprogenitors11. Plexin-B2 plays an essential role in neural tube closure and cerebellar granule cell migration during neurodevelopment12–14. Mouse mutant studies also revealed a role of Plexin-B2 in coordinating the proliferation and migration of neuroblasts in the rostral migratory stream12,13,15,16. Plexin-B2 is also expressed in brain tumor cells17 and epidermal stem cells18. Recent studies have begun to unravel the essential roles of Plexins in mediating cellular interactions in a variety of tissue contexts, including vascular development, immune activation, bone homeostasis, and epithelial morphogenesis and repair18–28. However, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear.

Interestingly, phylogenetic analyses unveiled an early evolutionary emergence of Plexins that predates the appearance of nervous systems29,30. Plexins have a highly conserved domain structure throughout all metazoan clades, particularly the ring-shaped extracellular domain and the intracellular Ras-GAP (GTPase activating protein) domain31,32. The Ras-GAP domain of Plexins can inactivate Ras or Rap small GTPases33, which have a pleiotropic network of effectors that control cytoskeletal dynamics and cell–cell adhesion34,35. Hence, we posit that Plexins may have evolved during the transition from unicellular to multicellular organisms to adjust cytoskeletal tension and adhesion forces at cell–cell and cell–matrix junctions29.

Here, we show that Plexin-B2 orchestrates multicellular dynamics of hESCs and hNPCs by controlling collective cytoskeletal dynamics and tensional forces. This, in turn, affects the maturation of adhesive complexes at cell–cell and cell–matrix junctions, thereby impacting membrane-association of β-catenin, focal adhesion, and integrin activation, leading to alteration of cell morphology and tissue geometry, as well as stem cell behaviors. We further delineate Plexin-B2 signaling domains, the role of RAP1/2 effectors, and the signaling relationship with the mechanosensitive transcription factor YAP (Yes-associated protein)36,37, thus providing a mechanistic link between Plexin-B2 signaling and stem cell physiology in a multicellular organization.

Results

Plexin-B2 affects the expansion and geometry of the hESC colony

To better understand the role of Plexin-B2 in a multicellular organization, we generated hESCs with PLXNB2 knockout (KO) by CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing, or Plexin-B2 overexpressing (OE) by lentiviral transduction. Western blot (WB) and immunofluorescence (IF) confirmed loss or gain of Plexin-B2 expression, respectively (Fig. 1a), while DNA sequencing confirmed biallelic CRISPR deletion mutations (Fig. S1a). Introducing a CRISPR-resistant rescue vector restored Plexin-B2 expression in KO cells (Fig. S1b). All CRISPR engineered hESCs displayed normal karyotypes (Fig. S1c).

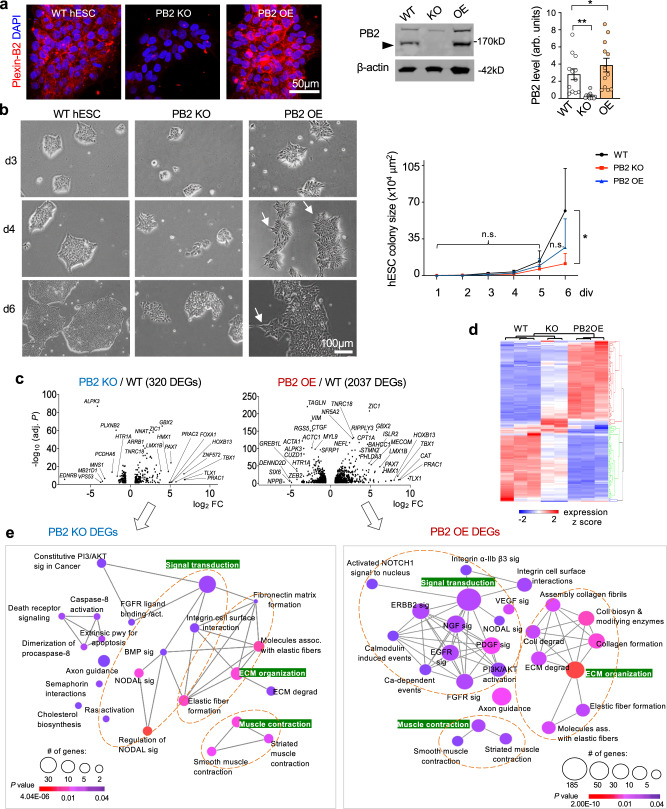

Fig. 1. Plexin-B2 controls growth and geometry of hESC colonies via mechanoregulation.

a IF images (left) show expression of Plexin-B2 (PB2) in wild-type hESC colony (clone WT#1), which was absent in PLXNB2 KO (clone KO#1) and enhanced in overexpression (OE) hESCs, respectively. Right, Western blot of hESCs probed for Plexin-B2. Arrowhead points to mature Plexin-B2 band at 170 kD. β-actin as a loading control. Quantification, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. n = 12 samples per group. arb.units arbitrary units. *P = 0.0231, **P = 0.0034. Data represent mean ± SEM. b Phase-contrast images of the indicated hESC colonies show similar initial growth kinetics after passage, but by day 6, PLXNB2 KO colonies appeared smaller (clone #1 for each WT and KO shown). Arrows point to spiky contours of OE colonies. Quantification of colony size is shown on right. Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. For WT colonies, n = 14, 14, 9, 10, 18, 7 for day 1–6, respectively; for PLXNB2 KO, n = 19, 14, 12, 14, 29, 25; and for PLXNB2 OE, n = 25, 15, 11, 17, 26, 23 colonies, from three independent cultures. *P = 0.0261; n.s. not significant. Data represent mean ± SEM. c Volcano plots show differentially expressed genes (DEGs) of PLXNB2 KO or OE hESCs relative to WT (cut-off thresholds: fold change >2 and P < 0.01). Top DEGs are labeled. The P values were computed by the DESeq2 package using the Wald test. d Heatmap shows unsupervised hierarchical clustering of the DEGs in different genotype conditions (fold change ≥2 between genotypes for the DEGs). e Geneset network view of enriched Reactome terms for DEGs in PLXNB2 KO or OE hESCs relative to WT. Note that gene pathways related to cell biomechanics were highly represented, as were many growth factor signaling pathways, such as EGF and FGF, that are critical for stem cell proliferation and differentiation. Highlighted in green are three major enriched pathways for the DEGs. The P values of node connectivity were computed by the Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon test.

hESCs under standard culture conditions resemble epiblast, an epithelial layer of pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) in the egg cylinder stage of mammalian embryos38. We found that after passage at low density, the initial growth kinetics of hESCs appeared similar among the WT, PLXNB2 KO, or OE conditions, but by day 6, the KO colonies became smaller than the WT or OE counterparts (Figs. 1b and S1d). Consistently, 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) pulsing labeled fewer cells in the S phase in KO colonies than in WT (Fig. S1e). Reexpressing Plexin-B2 rescued the phenotype, confirming the specificity of the CRISPR-KO approach, while Plexin-B2 OE did not further elevate the high proliferative state of hESCs (Fig. S1e, f). Cell survival was not overtly affected by Plexin-B2 KO, shown by IF for apoptosis marker cleaved caspase 3 (Fig. S1g). Quantitative analysis of the relationship between colony size and Plexin-B2 expression levels showed that Plexin-B2 expression remained constant during colony expansion (Fig. S1h). Intriguingly, we noted that the colony geometry was affected in mutant colonies, in particular, the PLXNB2 OE colonies displayed spiky contours along the colony edge, in drastic contrast to the smooth border typically seen in WT colonies (Fig. 1b). Together, these phenotypes indicate that Plexin-B2 critically regulates the colony expansion and geometry of hESCs.

Plexin-B2 affects gene expression concerning cell contraction and ECM interaction

To understand how guidance receptor Plexin-B2 controls colony expansion and geometry on a molecular level, we compared the transcriptomes of PLXNB2 KO and OE hESCs relative to WT by RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq). Bioinformatic analysis revealed 320 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between PLXNB2 KO and WT, and 2037 DEGs between OE and WT hESCs (Figs. 1c, d, and S2c).

Geneset network analysis showed that the enriched Reactome pathways in both sets of DEGs mainly concerned muscle contraction, elastic fiber formation, ECM organization, and integrin signaling (Fig. 1e). Pathway enrichment analyses further indicated that Plexin-B2 manipulations affected Rap1 signaling, Hippo signaling, and mechanoregulation of YAP/TAZ (Fig. S2a, b). These results suggest that Plexin-B2 may affect colony formation by controlling contractile and adhesive properties, which in turn impacts stem cell physiology. Indeed, bioinformatics analyses revealed that multiple signaling pathways critical for stem cell functions including EGFR, FGFR, MAPK, ERK1/2, Wnt/calcium, and focal adhesion/PI3K/AKT pathways, were all affected by Plexin-B2 manipulations (Figs. 1e and S2a, b).

We next intersected the two sets of DEGs (PLXNB2 KO or PLXNB2 OE vs. WT), which revealed 272 common DEGs, mainly concerning axon guidance, contractility, ECM interactions, Ras and Rap signaling, as well as NODAL and BMP signaling (Fig. S2c, d). In regard to nonoverlapping DEGs, Plexin-B2 OE specific DEGs (1765 genes) were enriched for receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) signaling, including PDGF, EGFR, NGF, VEGF, FGF, and ERBB2 signaling (Fig. S2c). This agrees with the known interactions of Plexins and RTKs39. In contrast, Plexin-B2 KO-specific DEGs (48 genes) were enriched for genes related to neuronal functions, e.g., neurotransmitter clearance, metabolism of serotonin, or dopamine degradation, suggesting neuronal lineage commitment of KO cells.

Interestingly, a majority of the common DEGs exhibited transcriptional changes in the same direction in both KO and OE hESCs relative to WT (Fig. S2d), suggesting that the gene expression changes likely reflect secondary adaption in response to altered cell biomechanics rather than direct transcriptional regulation by Plexin-B2 signaling. A small number of DEGs displayed opposite directionality of the transcriptional changes in KO and OE cells (Fig. S2d), including genes regulating stem cell function and matrix interactions, e.g., TNC (Tenascin C), an ECM gene involved in neuronal differentiation40, and CER1 (Cerberus1), a BMP antagonist essential for inhibiting nonneural differentiation of hESCs, as well as CCDC141 (coiled-coil domain containing 141), which inhibits cellular adhesion to fibronectin (FN), and TACR3 (Tachykinin receptor 3), a G protein-coupled receptor that regulates neuronal excitation and smooth muscle contraction.

Plexin-B2 orchestrates actomyosin network and cytoskeletal tension during hESC colony formation

The transcriptomics results indicated cell mechanics as a potential mechanism underlying Plexin-B2’s function in hESCs. We, therefore, examined the F-actin networks in hESC colonies by phalloidin staining (Fig. 2a). In WT colonies, we observed a uniform cobblestone-like cortical F-actin network in the colony interior, and a prominent F-actin band spanning multiple cells along colony periphery, consistent with higher in-plane traction forces at colony edge6. In comparison, the organization of F-actin networks was severely disrupted by Plexin-B2 KO or OE, albeit in different ways (Fig. 2a). In the KO colonies, we found that mutant cells tended to aggregate into small cell clusters, with F-actin accumulated at the center, while the peripheral F-actin band was absent, signifying dysregulation of cytoskeletal tension during colony formation. In the OE colonies, cells at the colony periphery were highly disorganized, forming spiky contours, and F-actin distribution was in disarray throughout the colonies, with many cells showing strengthened cortical F-actin and stretched cell borders. Indeed, quantification clearly demonstrated a more homogenous cellular arrangement in WT colonies than in mutants (Fig. 2b). As tissue tension is primarily generated by actomyosin contraction and initiated by phosphorylated myosin light chain 2 (pMLC2)9,41, we examined pMLC2 expression, which displayed marked disarray in mutant colonies, mirroring the F-actin patterns (Fig. 2a). Thus, Plexin-B2 has a critical role in organizing the actomyosin network and tensional forces during hESC colony formation.

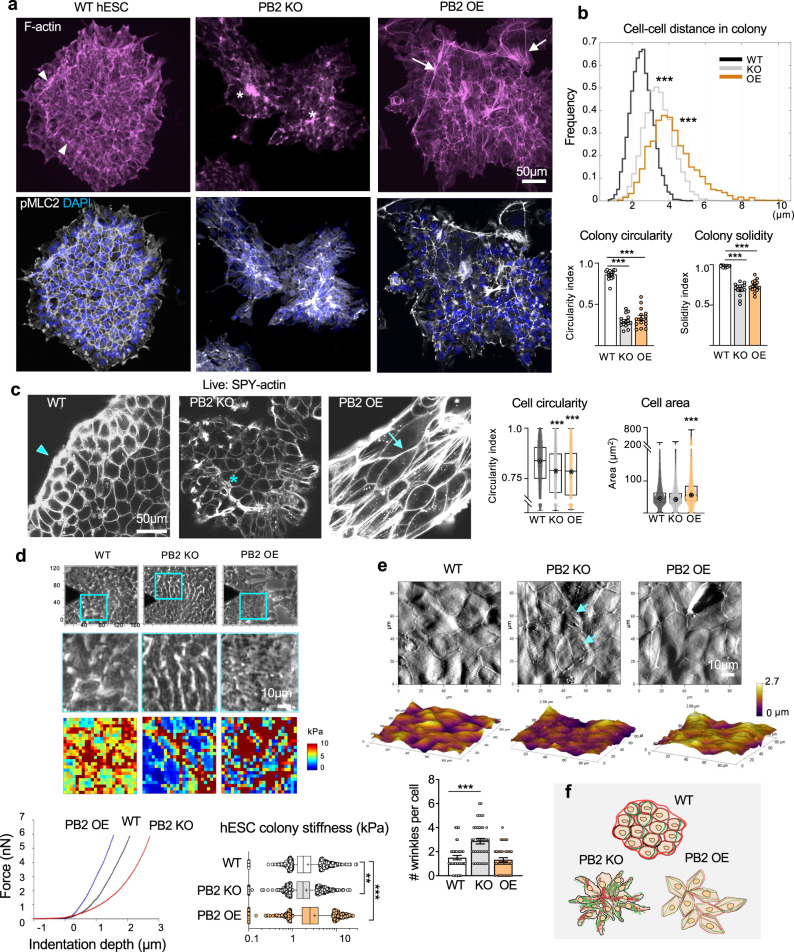

Fig. 2. Plexin-B2 orchestrates mechanotension and actomyosin network in hESC colonies.

a IF images of hESC colonies stained for F-actin (Alexa 568 phalloidin) and pMLC2 show differences in cell organization, colony geometry, and actomyosin network. Arrowheads point to the peripheral actomyosin band in the WT colony, which was disrupted in PLXNB2 KO or OE mutants. Asterisks denote abnormal cell clusters in the KO colony. Arrows point to stretched contours of the OE colony, often associated with F-actin stress fibers. DAPI for nuclear staining. b Top, histograms show the distributions of distances between neighboring cells within hESC colonies (distances between nucleus centroids). Note the wider distribution of cellular distances in KO or OE colonies than in WT, reflective of disorganization. Bottom, quantification of colony geometry (circularity index and solidity). For cell distance histogram, Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test, n = 7646 nuclei for WT, 4478 for PLXNB2 KO, and 2964 for PLXNB2 OE. ***P < 0.0001. For colony geometries, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, n = 15 colonies per group. ***P < 0.0001. Data represent mean ± SEM. c Live-cell imaging of hESC colonies show Plexin-B2-dependent differences in cell morphology, cell organization, and cortical F-actin visualized with SPY555-Actin probe. Arrowhead points to the peripheral F-actin band in WT colony, an asterisk denotes abnormal cell cluster in PLXNB2 KO colony (clone KO#2), and arrow points to tensed cortical F-actin and stretched junction borders in PLXNB2 OE colony. High content quantifications of cell shape (circularity index) and cell area are shown. Box plots show 25–75% quantiles, minimal and maximal values (whiskers), and median (bullseye). Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. For circularity: WT, n = 7878 cells; PLXNB2 KO, n = 5471, and PLXNB2 OE, n = 3904. For area: WT, n = 9725 cells; PLXNB2 KO, n = 5615, and PLXNB2 OE n = 4051. ***P < 0.0001. Data represent mean ± SEM. d Top panel, phase-contrast images show areas in hESC colonies (cyan boxes) measured by AFM elastography. Middle panels, side-by-side magnified phase-contrast images, and corresponding AFM stiffness heatmaps. Bottom, representative AFM indentation curves from elastography measurements (left) and box plots of hESC colony stiffness (right). Box plots show median, 25–75% quantiles and top and bottom 5% data points; mean values indicated by a cross sign. Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. Data collected from n = 7 samples for WT, n = 6 for PLXNB2 KO, and n = 7 for PLXNB2 OE. **P = 0.0032, ***P < 0.0001. e Top, AFM topography images show increased surface wrinkles in PLXNB2 KO cells (arrows), but more stretched surfaces of PLXNB2 OE cells compared to WT hESCs. Bottom, quantification of the number of surface wrinkles per cell. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. n = 40 cells analyzed per group. ***P < 0.0001. Data represent mean ± SEM. f Schematic depiction of cell morphology, cell organization, actomyosin network, and colony geometry as regulated by Plexin-B2 during hESC self-assembly. Red lines indicate F-actin and green lines myosin.

To examine cell morphology and F-actin networks with a higher spatiotemporal resolution during colony formation, we performed time-lapse live-cell imaging, using SPY-actin to label F-actin42. We found that PLXNB2 OE cells assumed a striking angular morphology with stretched cortical F-actin, taut cell borders, and larger cell area as compared to WT hESCs, whereas PLXNB2 KO cells exhibited less cortical F-actin, a more rounded shape, but comparable size relative to WT (Figs. 2c and S3a). As the cytoskeleton configuration may affect the size and arrangement of organelles, we compared the shape and size of nuclei in hESC colonies and found that PLXNB2 KO hESCs had smaller nuclei than WT cells, whereas PLXNB2 OE cells had more stretched and larger nuclei than WT cells (Fig. S3b).

Remarkably, live videography also revealed that hESCs were highly motile, with constant collisions between small cell clusters before they coalesced into larger colonies, and during this process, cells collectively organized their cortical F-actin networks into a cobblestone-like pattern in the colony interior and a prominent circumferential F-actin band spanning multiple cells at colony periphery (Supplementary Movie 1); this orchestration was severely disrupted by Plexin-B2 perturbations. Specifically, upon collision, PLXNB2 OE cells maintained an angular morphology and appeared sluggish in reorganizing F-actin networks, leading to stretched junctional borders and a spiky contour in nascent colonies. In contrast, PLXNB2 KO cells tended to aggregate into smaller clusters with a central accumulation of F-actin; upon collision, cells in the colony center remained disorganized, while the peripheral F-actin band failed to form.

We further analyzed cell motility during colony expansion by live-cell imaging, which showed that cells at the colony periphery migrated faster on average than those in the colony interior (Fig. S3c). Interestingly, the movement of cells at colony edge in Plexin-B2 OE conditions was highest among the three genotypes.

To gain temporal control, we introduced two independent doxycycline (Dox)-inducible shRNAs against PLXNB2 into hESCs (Fig. S3d). As in KO, Dox-induced Plexin-B2 knockdown (KD) resulted in disorganization of the actomyosin network and dissipation of the peripheral F-actin band (Fig. S3e, f). The altered colony geometry and cellular misalignment at the edges of KD colonies could be reversed by 24 h of Dox washout, indicating rapid cytoskeletal reorganization under the control of Plexin-B2 (Fig. S3g).

To directly gauge mechanical properties of hESC colonies in dependence of Plexin-B2, we conducted microindentation testing (elastography) using atomic force microscopy (AFM)43. Results showed that PLXNB2 KO cells had lower stiffness (mean 2.0 kPa) than WT (2.2 kPa), but PLXNB2 OE cells had higher stiffness (3.1 kPa) (Fig. 2d). We also performed 3D contact imaging by AFM to scan cell surface topologies, which revealed rougher surfaces for KO colonies, but smoother surfaces for OE colonies (Fig. 2e). Together, live-cell imaging and AFM measurements support the role of Plexin-B2 in orchestrating actomyosin organization and cytoskeletal tension during hESC colony formation (Fig. 2f).

Plexin-B2 controls actomyosin contractility and cell stiffness in hNPCs

Given a critical role of Plexin-B2 in neural tube closure and neuroprogenitor migration12, we next investigated whether Plexin-B2 controls biomechanical properties of hNPCs. To this end, we derived hNPCs from WT, PLXNB2 KO, or OE hESCs and analyzed actomyosin patterns. Similar to the results from hESCs, cortical actomyosin accumulation was reduced in PLXNB2 KO hNPCs relative to WT, but increased in OE cells (Fig. 3a, b). Morphometric quantifications confirmed alterations of cell shape as a result of Plexin-B2 manipulations (Fig. 3b). Interestingly, the nuclei of both PLXNB2 KO and OE hNPCs were on average smaller than those of WT counterparts (Fig. 3b), which may be associated with an aberrant differentiation state.

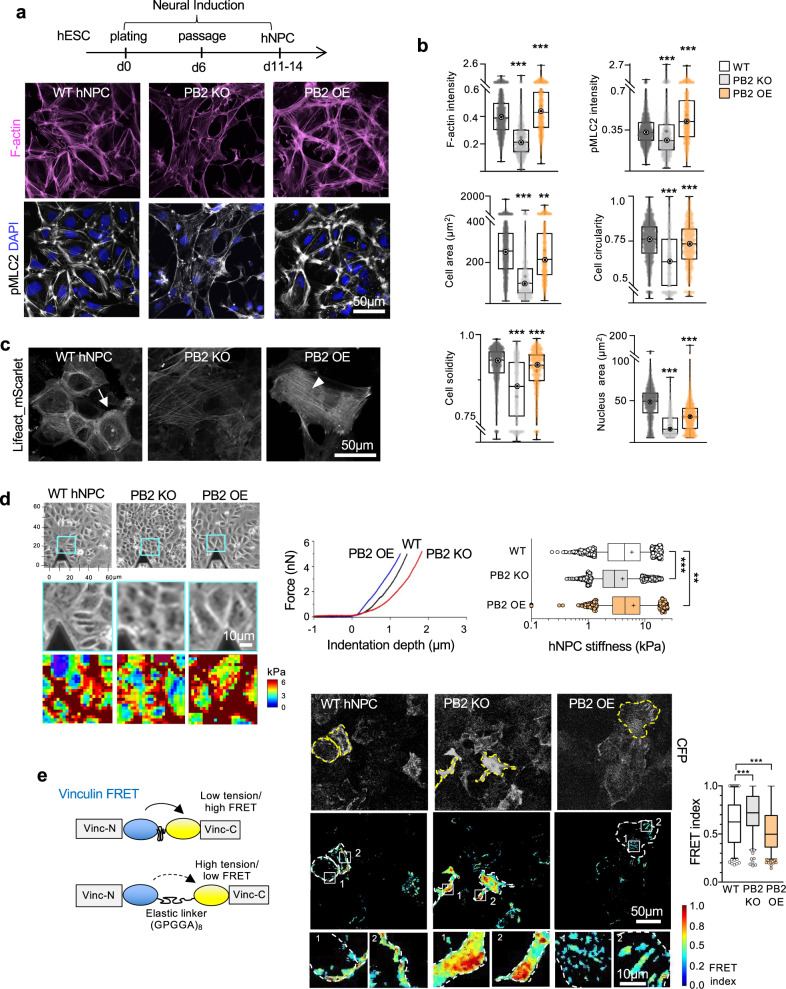

Fig. 3. Plexin-B2 regulates actomyosin contractility and cell stiffness in hNPCs.

a Top, timeline of neural induction to generate hESC-derived hNPCs. Bottom, confocal IF images of hNPCs show differences in F-actin (phalloidin) and pMLC2 in PLXNB2 KO and OE compared to WT cells. b Box plots show high content quantifications of F-actin and pMLC2 intensity, as well as geometries (cell spreading area, circularity, and solidity) and nuclei area of WT, PLXNB2 KO, and OE hNPCs. Box plots show 25–75% quantiles, minimal and maximal values (whiskers), median (bullseye), and mean (cross sign). For intensities and cell geometries: WT, n = 2123 cells; PLXNB2 KO, n = 930, and PLXNB2 OE, n = 1172. For nuclei area: WT, n = 2265 nuclei; PLXNB2 KO, n = 1275, and PLXNB2 OE, n = 1720. Data collected from 30 random fields per group. Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. **P = 0.0037 and ***P < 0.0001. c Live-cell imaging of hNPCs shows different F-actin distribution patterns in mutant hNPCs as revealed by Lifeact_mScarlet. Arrow points to cortical F-actin in WT hNPCs, which was reduced in PLXNB2 KO cells. Arrowhead points to stress fibers in PLXNB2 OE hNPCs. d Top, phase-contrast images depicting areas of hNPC cultures (cyan boxes) that were measured by AFM elastography. Bottom, side-by-side magnified phase-contrast images and corresponding AFM stiffness heatmaps. Right, representative AFM indentation curves from elastography measurements of WT, PLXNB2 KO, and OE hNPCs (left), and right, box plots quantification of cell stiffness (median, 25–75% quantiles, median, and top and bottom 5% data points, with mean values indicated by cross sign). Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. Data collected from n = 3 samples per group. **P = 0.0013, ***P < 0.0001. e Left, diagram of vinculin-based FRET tension sensor (CFP and YFP proteins connected by elastic linker) to gauge tensile forces at focal adhesions (FAs). Stretching of the linker reduces FRET signals. Middle, representative images of normalized FRET signals in hNPCs. Note that transient transfection leads to variable expression of FRET construct in cells, as visualized by CFP baseline fluorescence. Right, quantification of FRET index shown as box plots (median, 25–75% quantiles, and top or bottom 5% data points). Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. Data collected from 175 FAs for WT, 191 FAs for PLXNB2 KO, and 268 FAs for PLXNB2 OE. ***P = 0.0001 (WT vs PB2 KO) and ***P = 0.0008 (WT vs PB2 OE).

We next performed live-cell imaging of hNPCs labeled with mScarlet-Lifeact, a fluorescent F-actin probe44. We detected reduced cortical F-actin in PLXNB2 KO hNPCs, but a marked elevation in OE cells that contained actin stress-fibers and angular morphology (Fig. 3c). AFM elastography demonstrated that PLXNB2 OE NPCs exhibited higher cell stiffness (mean 6.3 kPa) than WT hNPCs (5.9 kPa); conversely, cell stiffness was lower for KO hNPCs (4.0 kPa) (Fig. 3d).

To measure tension exerted on FAs in hNPCs, we introduced a FRET tension sensor based on vinculin, an intracellular linker of adhesion sites with cytoskeleton45 (Fig. 3e). Analysis of the FRET signals revealed that the forces exerted on FAs were indeed lower in PLXNB2 KO than in WT hNPCs, but higher in OE hNPCs (Fig. 3e).

Plexin-B2 affects the organization of adhesion complexes in epithelial colonies and 3D hESC aggregates

So far, we showed that Plexin-B2 controls cell stiffness and actomyosin organization in the multicellular organization. As contractile forces are transmitted to cell–cell and cell–matrix junctions to maintain tissue cohesion3, we next studied the impact of Plexin-B2 on the organization of adhesion complexes in hESC colonies. We observed that while E-cadherin and ZO-1 displayed a uniform cobblestone-like network in WT colonies, both were severely disrupted in PLXNB2 mutant colonies (Figs. 4a and S4a), concordant with the cellular disarray and disorganized actomyosin networks.

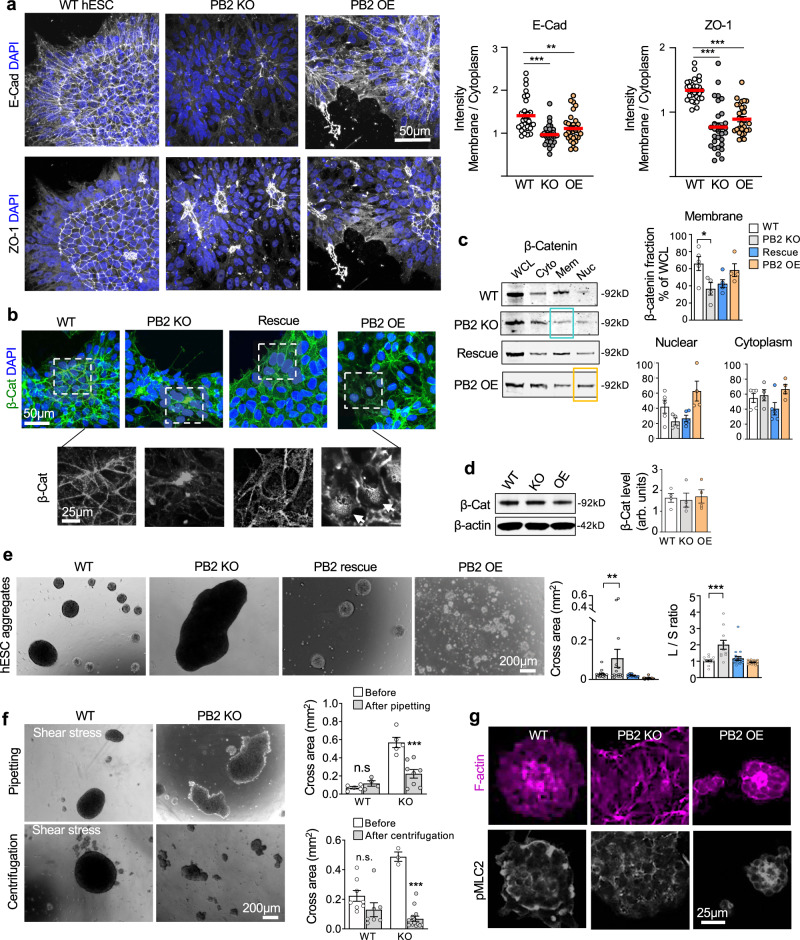

Fig. 4. Plexin-B2 influences cell–cell adhesion in multicellular organization of hESCs.

a Confocal IF images show altered junction recruitment of E-cadherin and ZO-1 in mutant hESC colonies in contrast to the organized pattern in WT colony. Data points in quantification shown on right represent boundary/cytoplasm ratios of E-cadherin and ZO-1 immunointensities. n = 30 cells per group. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. **P = 0.0016 and ***P < 0.0001. Red lines represent mean values. b Confocal IF images reveal redistribution of β-catenin in mutant hESC colonies. Enlarged images of boxed areas are shown in bottom panels, highlighting β-catenin membrane localization in WT cells, which was shifted to the center of cell clusters in PLXNB2 KO. Arrows point to increased nuclear β-catenin in PLXNB2 OE cells. c WBs of cell fractions show a shift of membrane-associated (Mem) β-catenin to the cytoplasm (Cyto) in PLXNB2 KO hESCs (highlighted by blue box), which was rescued by CRISPR-resistant Plexin-B2. PLXNB2 OE resulted in increased nuclear (Nuc) β-catenin (highlighted by orange box). WCL whole cell lysate. Quantifications are shown to the right. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. n = 5 for WT, n = 4 for PLXNB2 KO, n = 5 for Rescue, and n = 4 for PLXNB2 OE. *P = 0.0183. Data represent mean ± SEM. d WB and quantification show comparable levels of total β-catenin in WT and PLXNB2 mutant hESCs. β-actin served as a loading control. arb.units arbitrary units. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. n = 4 samples per group. Data represent mean ± SEM. e Floating 3D hESC aggregates after 48 h culture in low adherence conditions. Quantifications of cross area and shape (L/S ratio, longest vs. shortest diameter) of aggregates are shown on the right. PB2 KO clone #1. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. For cross area, n = 20 aggregates for WT, n = 15 for PLXNB2 KO, n = 9 for Rescue, and n = 37 for PLXNB2 OE. For L/S ratio, n = 19 aggregates for WT, n = 11 for PLXNB2 KO, n = 19 for Rescue, and n = 28 for PLXNB2 OE from 3–5 fields. **P = 0.0071, ***P < 0.0001. Data represent mean ± SEM. f Images and quantifications show the reduced capability of PLXNB2 KO hESC aggregates to withstand shear forces applied by pipetting or low-speed centrifugation compared to WT. Two-sided unpaired t-test to compare within the groups. For pipetting: WT, n = 5 aggregates before and n = 4 after; PLXNB2 KO, n = 5 before and n = 8 after. ***P = 0.0008. For centrifugation: WT, n = 8 before and n = 7 after; PLXNB2 KO, n = 3 aggregates before and n = 14 after. ***P < 0.0001; n.s. not significant. Data represent mean ± SEM. g IHC images of cross section of 3D hESC aggregates show that PLXNB2 KO resulted in cellular disarray and disorganized actomyosin networks, whereas PLXNB2 OE led to enhanced actomyosin compact.

In hESCs, β-catenin forms a complex with E-cadherin46, which connects to actin cytoskeleton to mediate cell–cell adhesion and pluripotency8. Indeed, in WT hESCs, β-catenin displayed a similar cobblestone-like pattern as E-cadherin (Fig. 4b). However, Plexin-B2-deficiency resulted in reduced membrane association of β-catenin and redistribution towards the center of cell clusters, a phenotype partially rescued by Plexin-B2 re-expression; in contrast, Plexin-B2 OE led to an increased nuclear fraction of β-catenin (Fig. 4b). These phenotypes are likely a consequence of the disorganized membrane clustering of E-cadherin in hESC colonies. WB confirmed a shift in subcellular localization of β-catenin (Fig. 4c), while the total protein levels remained similar in all three groups (Fig. 4d). The subcellular fractionation approach was verified by probing for markers of nuclear, cytoplasmic, and membrane fractions, respectively (Fig. S4b).

We next examined the impact of Plexin-B2 on the self-assembly of hESCs in a 3D context. When cultured in low-attachment dishes, WT hESCs spontaneously aggregated into compact spheroids of ~200–500 μm diameter by 48 h; strikingly, PLXNB2 KO cells formed larger but irregularly shaped aggregates, measuring up to 1.5 mm in length, a phenotype rescued by Plexin-B2 reexpression (Fig. 4e). Conversely, PLXNB2 OE resulted in smaller but more compact aggregates (~18–60 μm in diameter), reflective of a heightened contractile state. As a gauge of tissue cohesion or adhesive forces between cells, we tested the ability of hESC aggregates to resist external shear stress applied either through gentle pipetting or by centrifugation47. Results showed that whereas WT aggregates maintained the compact spheroid shape under shear stress, the large PLXNB2 KO aggregates appeared easily broken up into smaller pieces with uneven shapes, consistent with reduced tissue cohesion (Fig. 4f).

Concordantly, IF staining of cross sections of the WT spheroids revealed a high concentration of organized F-actin networks in the center, surrounded by a rim of pMLC2 at the periphery, whereas both F-actin and pMLC2 appeared more compact in PLXNB2 OE spheroids, but looser and in disarray in KO aggregates (Fig. 4g). Actomyosin contraction can affect FN assembly in multicellular organization48,49. Indeed, as another sign of disorganized actomyosin network, the gradient of FN fibrils extending from core to periphery seen in WT spheroids appeared more compact in PLXNB2 OE spheroids, but in marked disarray in KO aggregates (Fig. S4c).

As an alternative approach to gauge cell–cell cohesion, we also examined aggregation of hESCs and hNPCs in a hanging drop assay50. We detected reduced or enhanced compaction of hanging drop aggregates of PLXNB2 KO or OE cells, respectively, relative to WT counterparts (Fig. S4d, e).

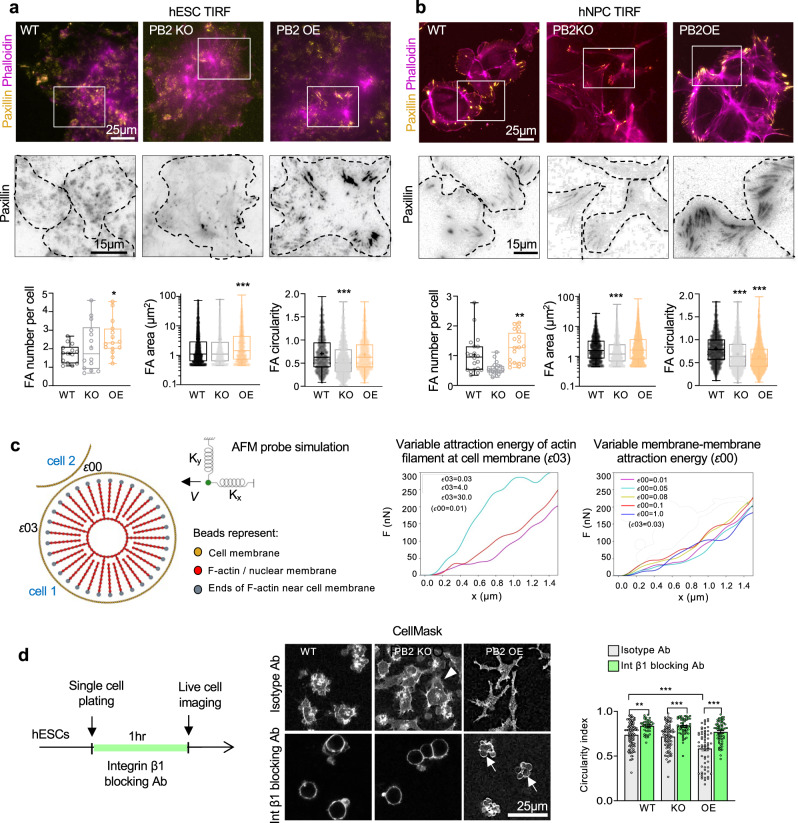

Plexin-B2 affects focal adhesion maturation in hESC colony and hNPCs

We next examined the impact of Plexin-B2-mediated actomyosin tension on the interface of cytoskeleton and matrix. We performed total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy for morphometric analysis of FAs visualized by paxillin IF (Fig. 5a, b). In both hESCs and hNPCs, we observed increased numbers of FAs with PLXNB2 OE. In addition, both the size and the shape of FAs were also altered, with generally larger FAs with PLXNB2 OE, and less circular ones with KO, although there were variabilities between hESCs and hNPCs (Fig. 5a, b).

Fig. 5. Plexin-B2 influences cell–matrix adhesion and controls contractility in hESC colonies.

a, b TIRF microscopy images and quantification show altered number, size, and shape of focal adhesions (FAs) in PLXNB2 mutant hESC colonies (a) and hNPCs (b) compared to wild-type (WT) cells. Cells were stained for FA marker paxillin and F-actin (phalloidin). Enlarged images of boxed areas are shown below in inverted black and white, with dashed lines outlining individual cells. Box plots depict 25–75% quantiles, minimal and maximal values (whiskers), median (midline), and mean (cross signs). For hESCs: FA number, n = 14–15 cells per group. FA area, n = 2271 FAs for WT, n = 1042 for PB2 KO, and n = 978 for PB2 OE. FA circularity, n = 1042 FAs for WT, n = 1042 for PB2 KO, and n = 978 for PB2 OE. *P = 0.0397, ***P < 0.0001. For hNPCs: FA number, n = 20 cells per group. FA area and circularity, n = 1829 FAs for WT, n = 2385 for PB2 KO, and n = 4528 for PB2 OE. Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. **P = 0.0084, ***P < 0.0001. c Molecular dynamics mathematical simulation. Left, components of simulation based on a bead-spring model. The tip of the simulated AFM probe is depicted as a green sphere, with elastic constants Kx and Ky in the x and y directions, respectively. Right, graphs of force as a function of distance traveled by the simulated AFM probe in two different scenarios. Left, when varying the actin-membrane attraction energy that simulates increasing contractility, the response of the force to the virtual AFM probe resembles the results of the experimental AFM data in accordance to Plexin-B2 activity (see Fig. 2). Such result is not seen when varying membrane-membrane attraction energy (right). d Left, experimental design for live-cell imaging. Middle, images of hESCs labeled with CellMask reveal distinct cell morphology when exposed to a function-blocking antibody against integrin β1 (P5D2) or an isotype control IgG. Arrowhead points to cellular protrusion from PLXNB2 KO hESCs. Arrows point to cell membrane blebbing of PLXNB2 OE hESCs after integrin blockade. Quantification for cell roundness (circularity index) is shown on right. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. For isotype IgG treatment: n = 100 cells for WT, n = 80 cells for PB2 KO, and n = 63 for PB2 OE. For integrin β1 treatment: n = 41 cells for WT, n = 54 for PB2 KO, and n = 63 cells for PB2 OE. **P = 0.0025 and ***P < 0.0001. Data represent mean ± SEM.

Next, we investigated the levels of phosphorylated focal adhesion kinase (pFAK) as an indicator of stable FAs. Confocal microscopy revealed diminished levels of pFAK in Plexin-B2-deficient hESC colonies, but enhanced accumulation in Plexin-B2 OE, both in disarray in contrast to the cobblestone-like pattern seen in WT (Fig. S5a). In hNPCs, Plexin-B2 OE also led to increased pFAK levels (Fig. S5b). Together, these data support the notion that FA maturation is affected by different tensional forces as mediated by Plexin-B2.

In Drosophila sensory neurons, Plexin-B forms a complex with integrin β and stabilizes it on the cell surface to regulate self-avoidance and dendritic tiling51. Our microscopy analysis of hESC colonies revealed analogous results, with active integrin β1 immunosignals attenuated in PLXNB2 KO, but enhanced in OE colonies (Fig. S5c). Of note, WB showed that only the intracellular localization, but not the total protein level of integrin β1 was affected by PLXNB2 KO (Fig. S5d). A similar loss of active integrin β1 was observed in PLXNB2 KO hNPCs (Fig. S5e). Hence, Plexin-B2 controls actomyosin tension and maturation of junctional adhesions in multicellular organization (Fig. S5f).

Plexin-B2 primarily controls contractility in hESC colony with consequent changes in adhesion

Our next question pertains to whether Plexin-B2 primarily controls actomyosin contractility or adhesive strength, two interconnected processes in a multicellular organization. To address this question, we performed mathematical simulations of cell mechanics using the molecular dynamics approach52,53. We first developed a membrane model that reproduces the main elements of cellular mechanical components based on the coarse-grained bead-spring model, wherein cell membrane, nuclear membrane, and actin filaments were modeled as beads connected by springs; and a virtual AFM tip was represented as a sphere anchored by two springs (Fig. 5c). We simulated how cell stiffness might behave in response to either: (i) modulation of actomyosin contractile forces, as simulated by altering the attraction energy between actin filament heads and cell membrane (energy ɛ03) or (ii) varying cell adhesion, as simulated by altering the interaction energy between neighboring cell membranes (ɛ00). We tested two scenarios: variable ɛ03 with fixed ɛ00, or variable ɛ00 with fixed ɛ03 (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Movies 2, 3). The simulation results from the first scenario—i.e., modulating actomyosin contractile forces—aligned better with our experimental AFM data. Hence, mathematical simulations support the model that Plexin-B2 primarily controls actomyosin contractility, with secondary effects on cell adhesiveness during the multicellular organization.

To corroborate the simulation results, we assayed the contractile properties of hESCs in the single-cell state under adherent vs. non-adherent conditions, thus decoupling actomyosin contraction from cell–cell or cell–matrix adhesion (Fig. 5d). Live-cell imaging revealed that under adherent conditions, individual cells with PLXNB2 OE assumed a highly branched morphology, whereas KO cells frequently extended cellular protrusions, suggestive of reduced cell–matrix anchorage. We then released cells from matrix anchorage by incubation with an anti-integrin β1 blocking antibody. This resulted in rounding-up of cells, and notably, PLXNB2 OE cells displayed membrane blebbing, signifying cytoskeletal hypercontractility (Fig. 5d). This agrees with the model that a main function of Plexin-B2 is to promote actomyosin contractility.

To further test this model, we applied WT or PLXNB2 mutant hESCs pharmacological inhibitors for myosin II (blebbistatin, 10 µM) or Rho-associated coiled-coil-containing kinase (ROCK) (Y-27632, 20 µM)54 (Fig. S6a, b). Inhibition of actomyosin contractility by these inhibitors indeed abolished the hypercontractile state of Plexin-B2 OE cells, leading to junction changes resembling the KO phenotypes in all three genotype conditions (Fig. S6b). Exposure to latrunculin (5 µM), which inhibits F-actin assembly, resulted in rounding-up of cells and cell dissociation in all three groups (Fig. S6b). These data support the interconnection of actomyosin contractility and cell adhesion with a primary function of Plexin-B2 in promoting the former. Interestingly, treatment with Y16 (25 µM), a specific inhibitor of the Rho-GEFs, which can function as downstream effectors of Plexin-Bs55, caused no significant morphological changes in hESC colonies or in 3D spheroids in all three groups (Fig. S6c, d).

We performed additional mathematical simulations of molecular dynamics to probe the impact of varying actomyosin contractility on cell cohesion in multicellular settings. This was interrogated by calculating the force needed to pull cells from the colony edge or from the colony center. Simulation results indicated that increased cell contractility can strengthen cell–cell cohesiveness (Fig. S6e). Altogether, our results demonstrated that Plexin-B2-deficient hESCs formed less compact and less cohesive colonies, whereas Plexin-B2 OE hESCs formed more adhesive colonies. As both Plexin-B2 KO and OE colonies displayed marked cellular disarray, it indicated that a balanced level of Plexin-B2 activity is required to orchestrate multicellular dynamics.

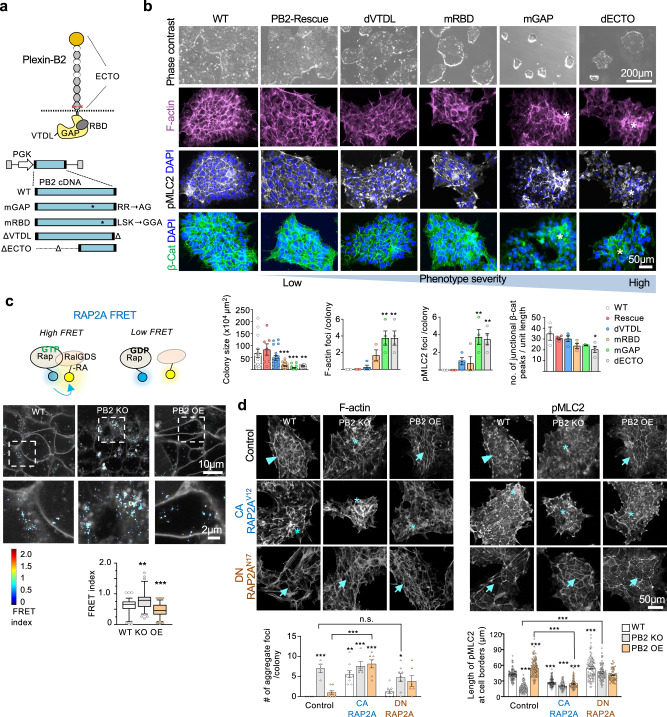

Plexin-B2 engages extracellular and Ras-GAP domains to orchestrate cytoskeletal network

Plexin-B2 can potentially signal through its Ras-GAP domain to inactivate Ras/Rho small GTPases56–59, its Rho-binding domain (RBD) that can bind to Rac or Rnd57,60, or its C-terminal PDZ binding motif as a docking site for PDZ-Rho-GEFs to activate RhoA61 (Fig. 6a). We next dissected which of these Plexin-B2 domains are engaged in the mechanoregulation of multicellular dynamics.

Fig. 6. Plexin-B2 signals through RAP1/2 to orchestrate cell mechanics in hESC colonies.

a Top, Plexin-B2 domain structure: ECTO ectodomain, RBD Rho-binding domain, GAP Ras-GTPase domain, VTDL, four C-terminal amino acids, forming PDZ binding motif. The cleavage site of mature Plexin-B2 is depicted by red arrows. Bottom, lentiviral vectors expressing wild-type (WT) Plexin-B2 or signaling mutants (CRISPR-KO resistant): mGAP mutation in GAP, mRBD mutation in RBD, ΔVTDL deletion of VTDL, ΔECTO deletion of ECTO domain. b Phase-contrast and confocal images illustrate the severity of cytoskeletal disarray and β-catenin membrane distribution phenotypes of hESC colonies expressing wild-type or Plexin-B2 signaling mutants (in the background of PLXNB2 KO). Asterisks denote abnormal cell clusters within the colony. Quantifications are shown below. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. For hESC colony size: n = 14 colonies for WT, n = 7 for Rescue, n = 18 for dVTDL, n = 24 for mRBD, n = 21 for mGAP, and n = 12 for dECTO. **P = 0.0028; ***P < 0.0003 (WT vs mRBD), ***P < 0.0001 (WT vs mGAP). For others, n = 3–4 for each group. For F-actin foci, **P = 0.002. For pMLC2 foci, **P = 0.0019 (WT vs. mGAP) and **P = 0.0037 (WT vs. dECTO). For junctional β-cat peaks, *P = 0.025. Data represent mean ± SEM. c Top, diagram of FRET probes for RAP2A activation status. Middle, representative images of normalized RAP2A FRET signals in WT, PLXNB2 KO (clone #3), PLXNB2 OE hESCs. Enlarged images of boxed areas are shown below. Box plots show median, 25–75% quantiles, and top or bottom 5% data points. Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. n = 98 cell–cell membrane areas for WT; n = 89 for PB2 KO; n = 85 for PLXNB2 OE. **P = 0.0013 and ***P < 0.0001. d Confocal IF images show the effects of RAP2A isoforms on cortical actomyosin network, colony geometry, and cellular organization of hESC colonies as compared to control colonies with no RAP2A expression vector. Arrowheads point to the peripheral F-actin band in WT colony, asterisks denote abnormal cell cluster in PLXNB2 KO colony, and arrows point to tensed cortical F-actin and stretched junction borders in PLXNB2 OE colony. Note that constitutively active (CA) RAP2AV12 phenocopied Plexin-B2 KO (clone #3), whereas dominant-negative (DN) RAP2AN17 phenocopied Plexin-B2 OE. Quantifications of actomyosin aggregate foci per colony and length of pMLC2 at cell borders are shown below. For aggregate foci: control, n = 4 colonies for WT, n = 4 for PB2 KO, and n = 8 for PB2 OE; CA RAP2AV12, n = 9 for WT, n = 5 for PB2 KO, and n = 7 for PB2 OE; DN RAP2AN17, n = 9 for WT, n = 8 for PB2 KO, and n = 6 for PB2 OE. *P = 0.010, **P = 0.0017, ***P < 0.0001. For pMLC2: control, n = 80–100 cell borders for each genotype; CA RAP2AV12, n = 60–70 for each genotype; DN RAP2AN17, WT, n = 50–90 for each genotype. ***P < 0.0001. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc correction to compare to WT group. A two-sided unpaired t-test was applied when comparing data from two groups (brackets). Data represent mean ± SEM.

We introduced a series of Plexin-B2 mutants into KO hESCs to conduct domain-specific rescue experiments: Plexin-B2-mGAP (mutation of amino acids required for Ras-GAP activity), -mRBD (critical mutations in RBD domain), -ΔVTDL (deletion of PDZ binding motif), and -ΔECTO (deletion of an extracellular domain) (Fig. 6a). WB and ICC confirmed comparable expression levels of Plexin-B2 signaling mutants in hESCs (Fig. S7a, b).

We found that the Plexin-B2 KO phenotypes—i.e., altered colony size and geometry, disorganized actomyosin and β-catenin networks—could be fully restored by wild-type (WT) Plexin-B2 rescue vector, largely rescued by Plexin-B2-ΔVTDL, partially rescued by Plexin-B2-mRBD, but minimally by Plexin-B2-mGAP and -ΔECTO (Fig. 6b). Hence, the extracellular and the Ras-GAP domains, and to a lesser degree RBD domain, are required for Plexin-B2 mechanoregulatory activity. In contrast, the C-terminal PDZ binding motif appeared dispensable, echoing the results from Rho-GEF inhibitor Y16 (see Fig. S6c, d),

Since the extracellular domain of Plexin-B2 is required to rescue the KO phenotype in the hESC colony, we tested how hESCs respond to Sema4C, a ligand for Plexin-B2. When WT hESCs were exposed to increasing concentrations of Sema4C mixed with Matrigel substrate, colony geometry was perturbed, displaying a contractile appearance with irregular contours, resembling the tensed appearance of PLXNB2 OE colonies (Fig. S7c). PLXNB2 OE cells responded to Sema4C similarly as WT cells, but Plexin-B2 KO cells appeared insensitive to Sema4C. Of note, anchorage of Sema4C to the cell membrane or substrate surface seemed critical as applying Sema4C in culture media did not elicit such an effect (Fig. S7d). It is notable that the effect of Sema4C was not identical to Plexin-B2 OE, thus a ligand-independent function of Plexin-B2 or its involvement in homotypic cell–cell adhesion remains a possibility18.

Plexin-B2 signals through RAP1/2 for mechanoregulation

Next, to validate the importance of the Ras-GAP domain of Plexin-B2 during hESC colony formation, we utilized genetic FRET probes to probe the activation status of RAP1/2 by live-cell imaging. Indeed, the FRET probes revealed that PLXNB2 OE cells showed reduced RAP1A and 2A activation as compared to WT cells, while KO cells displayed enhanced RAP1/2 activation (Figs. 6c and S8a).

To further test the functions of RAP1/2 as downstream effectors of Plexin-B2, we introduced constitutively active (CA) or dominant-negative (DN) isoforms of RAP1B or 2A into hESCs (Figs. 6d and S8b). In all three groups (WT, PLXNB2 KO, or OE), expression of CA RAP1B or 2A phenocopied Plexin-B2 KO in regards to disorganized actomyosin networks, dissipation of the peripheral F-actin band, and filopodia-like protrusions at colony edge. Conversely, DN RAP1/2 phenocopied Plexin-B2 OE in regards to strengthened cortical F-actin, angular morphology, stretched cell borders, and spiky colony contours in all three genotypes, including Plexin-B2 KO (Figs. 6d and S8b). Additionally, membrane clustering of β-catenin, as well as the proliferation of hESCs, were affected by CA- or DN- Rap1/2 mutants, again phenocopying Plexin-B2 KO or OE, respectively (Fig. S8c, d). Hence, functional data support the engagement of RAP1/2 by Plexin-B2 in the mechanoregulation of the hESC colony.

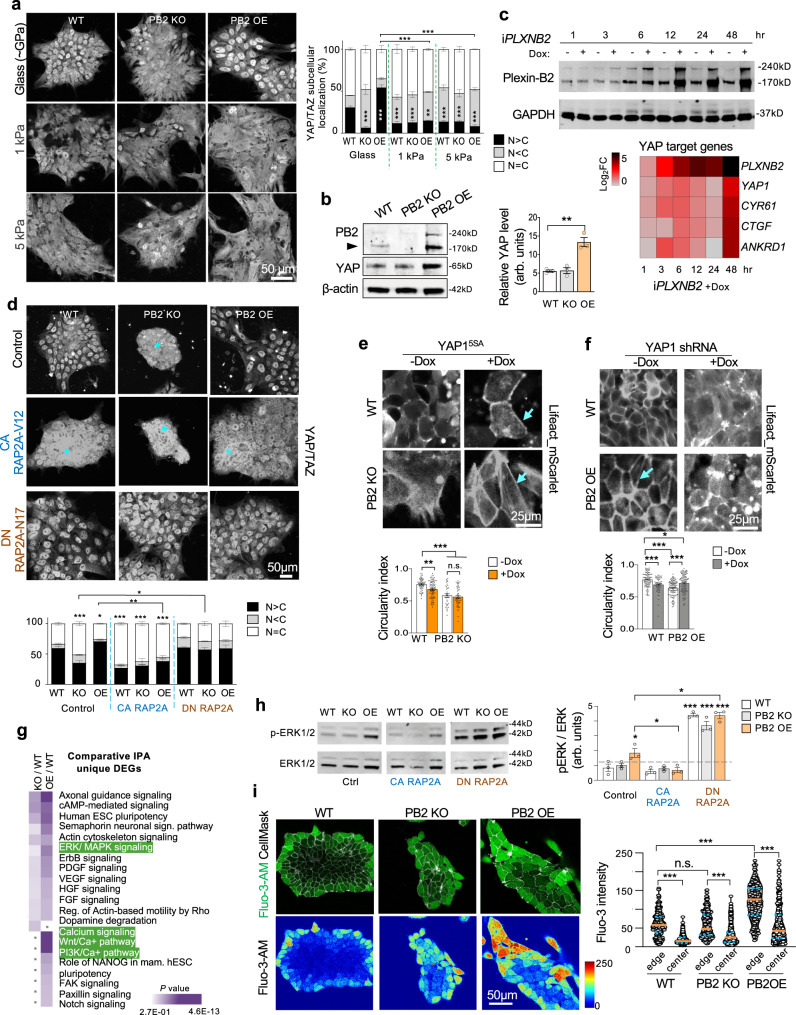

Plexin-B2-mediated cytoskeletal tension impacts on YAP/TAZ activity

Cells can respond to the mechanical properties of the surrounding physical environment, such as substrate rigidity, through the mechanosensitive transcription factors YAP/TAZ36, which are the main executors of the Hippo pathway37. Of note, our transcriptomic analysis had indicated an effect of Plexin-B2 manipulations on Hippo/YAP/TAZ signaling (see Fig. S2a). To explore whether Plexin-B2 affects YAP/TAZ activation in hESC colonies, we examined the nuclear localization of YAP/TAZ as a readout—i.e., inactive YAP is phosphorylated and retained in the cytoplasm for degradation, whereas active YAP is translocated into the nucleus to drive pro-growth gene programs62,63. IF revealed a nucleus-to-cytoplasm shift of YAP/TAZ in Plexin-B2-deficient hESCs as compared to WT, and conversely, a cytoplasm-to-nucleus shift in OE cells (Figs. 7a and S9a). It is worth noting that, unlike differentiated cells, human PSCs are insensitive to contact inhibition as they display a sustained basal YAP-driven transcriptional activity despite growing as dense colonies64.

Fig. 7. Plexin-B2 engages the YAP mechanotransduction pathway and activates ERK1/2 and calcium signaling.

a Confocal IF images show reduced nuclear YAP/TAZ in PLXNB2 KO hESCs, but a cytoplasm-to-nucleus shift in PLXNB2 OE as compared to WT cells on standard cell culture substrate (glass coverslip coated with Matrigel). Cultures on hydrogels with softer stiffness (1 and 5 kPa) is similar for all genotype groups with a strong reduction of nuclear YAP/TAZ. Quantifications show relative fractions of cells with nuclear YAP/TAZ signals that are greater, equal, or smaller than cytoplasmic signals (N > C, N = C, N < C). Two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test to compare to WT. n = 115–301 cells for each condition **P = 0.0019, ***P = 0.0001 (WT glass vs KO and OE glass), ***P = 0.0002 (WT glass vs WT 1 kPa), ***P = 0.0004 (WT glass vs KO 1 kPa), ***P = 0.0008 (WT glass vs WT 5 kPa), ***P = 0.0009 (WT glass vs KO 5 kPa), ***P = 0.0001 (WT glass vs OE 5 kPa). A two-sided unpaired t-test was applied when comparing data from two groups (brackets). ***P = 0.0002 (OE Glass vs OE 1 kPa, and OE Glass vs OE 5 kPa), Data represent mean ± SEM. b WB and quantification show an increased level of total YAP in PLXNB2 OE cells as compared to WT or PLXNB2 KO hESCs. Arrowhead points to mature Plexin-B2 band. β-actin served as a loading control. arb.units arbitrary units. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. n = 3 samples per group. **P = 0.0017. Data represent mean ± SEM. c Top, WB shows time course of Dox-induced expression of Plexin-B2 (iPLXNB2) in hESCs. GAPDH served as a loading control. Bottom, heatmap of qRT-PCR data illustrates upregulation of YAP1 and its target genes CYR61, CTGF, and ANKRD1 upon Plexin-B2 induction. The heatmap was generated by the mean value from n = 3 independent cultures. d IF images show the effects of RAP2A isoforms on YAP/TAZ nuclei/cytoplasmic localization in hESC colonies. Note that expression of constitutive active RAP2AV12 led to elevated cytoplasmic YAP/TAZ in all three groups, phenocopying Plexin-B2 KO. Quantification shows relative fractions of cells with nuclear YAP/TAZ immunosignals that are greater, equal, or smaller than cytoplasmic signals (N > C, N = C, N < C). Two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test to compare to WT group. For control, n = 330–466 cells for each genotype; for CA RAP2AV12, n = 163–233 for each genotype; for DN RAP2AN17, n = 412–543 for each genotype *P = 0.040 and ***P < 0.0001. A two-sided unpaired t-test was applied when comparing data from two groups (brackets). *P = 0.015, **P = 0.0012. Data represent mean ± SEM. e, f Live-cell imaging shows differences in cortical F-actin (visualized by LifeAct_mScarlet) in hESCs with Dox-inducible expression of YAP15SA (e) or YAP1 shRNA (f). Arrows point to tensed cortical F-actin and stretched cell borders. Data represent mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. For YAP15SA: WT, n = 54–80 cells; PB2 KO, n = 33–50 cells. **P = 0.0053 and ***P < 0.0001. For YAP1 shRNA: WT, n = 62–89 cells; PB2 OE, n = 100 cells each. *P = 0.012 and ***P < 0.0001. n.s. not significant. Data represent mean ± SEM. g Comparative Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) of enriched gene pathways for the unique DEGs identified in PLXNB2 KO or OE hESCs relative to WT. Note the enhanced activation of ERK/MAPK and calcium signaling in Plexin-B2 OE cells. The categories are ranked by adjusted P value computed by IPA’s Fisher’s Exact Test. h WBs show increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation (p-ERK1/2) in PLXNB2 OE cells compared to WT. p-ERK1/2 was further increased by DN RAP2AN17 expression in all three groups (WT, PB2 KO, and PB2 OE). In contrast, CA RAP2AV12 expression resulted in reduced p-ERK1/2 in PLXNB2 OE cells. ERK1/2 served as a loading control. arb.units arbitrary units. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc correction to compare to WT group. A two-sided unpaired t-test was applied when comparing data from two groups (brackets). n = 3 samples per group. *P = 0.017 (WT vs. PB2 OE), *P = 0.028 (Control PB2 OE vs. CA RAP2AV12 PB2 OE), *P = 0.0024 (Control PB2 OE vs. DN RAP2AN17 PB2 OE), ***P < 0.0001. Data represent mean ± SEM. i Calcium imaging with Fluo-3-AM dye shows higher levels of intracellular calcium in hESCs at colony edges compared to central areas. Calcium signals were elevated in PLXNB2 OE. Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. For colony edges, n = 328, 332, and 116 for WT, PB2 KO, and PB2 OE, respectively. For colony center, n = 1000, 648, 417 cells for WT, PB2 KO, and PB2 OE, respectively. ***P < 0.0001. Orange lines indicate median values and blue lines 25 and 75% percentiles.

Cytoskeletal mechanotension ensured by Plexin-B2 signaling may in fact facilitate response to extracellular mechanical cues such as substrate stiffness. To address this, we examined YAP activation in WT or Plexin-B2 mutant hESCs grown on soft or stiff substrates. Results showed that WT and Plexin-B2 OE hESCs responded to softer substrates with reduced nuclear YAP and to a stiffer substrate with YAP nuclear translocation, with Plexin-B2 OE cells responded more robustly than WT cells with higher levels of nuclear YAP (Fig. 7a). In contrast, Plexin-B2 KO hESCs were insensitive to substrates stiffness in terms of YAP nuclear localization, which remained low in all conditions.

Consistently, WB showed higher levels of YAP in PLXNB2 OE hESCs than in WT (Fig. 7b). Furthermore, the expression of YAP target genes CYR61, CTGF, and ANKRD1 was robustly upregulated in response to Dox-induced overexpression of Plexin-B2 in hESCs (Fig. 7c). Our RNA-seq data also showed transcriptional changes of YAP signature genes in Plexin-B2 mutant hESCs as compared to WT, and principal component analysis (PCA) based on the expression of YAP signature genes showed clear segregation of WT, PLXNB2 KO, and OE hESC samples, confirming that each genotype leads to a distinct state of YAP signaling (Fig. S9b, c). Interestingly some of the YAP target genes responded differently to constitutive overexpression vs. acute upregulation of Plexin-B2 in the inducible model (Fig. S9b). This may be reconciled by the fact that certain YAP target genes have been shown to act as a transient response to biomechanical stimuli65.

Additionally, the introduction of CA RAP2A resulted in YAP inactivation (nucleus-to-cytoplasm shift) in all three genotypes, phenocopying Plexin-B2 KO, whereas DN RAP2A reverted YAP inactivation in Plexin-B2 KO cells (Fig. 7d).

To further interrogate a functional link between Plexin-B2 and YAP signaling, we introduced a Dox-inducible CA form of YAP (YAP15SA) into WT or PLXNB2 mutant hESCs (Fig. S9d), which led to angular cell morphologies and strengthened cortical F-actin in WT but also in PLXNB2 KO hESCs, reminiscent of the OE phenotypes (Fig. 7e). Conversely, YAP1 KD by shRNA resulted in diminished cortical F-actin in WT hESCs, but also attenuated the hypercontractile phenotype of Plexin-B2 OE cells (Figs. 7f and S9e, f).

As another way to test the functional relationship of Plexin-B2 and YAP and β-catenin in hESCs, we exposed hESCs to verteporfin (VP), an inhibitor of YAP signaling, or cardamonin, which promotes degradation of β-catenin (Fig. S10a). Results showed that VP markedly reduced proliferation of WT and PLXNB2 OE hESCs, but did not further diminish the proliferation of KO cells (Fig. S10b), thus supporting YAP as a downstream effector of Plexin-B2 in regard to hESC proliferation. Correspondingly, the colony size was reduced in WT and Plexin-B2 OE by VP, but VP did not further reduce the size of PLXNB2 KO colonies, which were already smaller than WT (Fig. S10b). VP also phenocopied YAP1 KD in reducing cortical F-actin in WT or Plexin-B2 OE hESCs, and attenuated the hypercontractile appearance of OE cells (Fig. S10c). In contrast, cardamonin did not significantly alter the proliferation or cortical F-actin patterns in hESCs of either of the three genotypes, but it altered cellular arrangement in WT hESC colonies (Fig. S10b, c). These observations fit with our mathematical simulations that Plexin-B2 primarily controls actomyosin contractility, with secondary effects on adhesion complexes during the multicellular organization.

Hence, YAP can not only respond to Plexin-B2-mediated cytoskeletal tension but can mediate cytoskeletal dynamics and stem cell state in hESC colonies. Moreover, Plexin-B2-mediated cytoskeletal tension ensures mechanoresponse of YAP to extracellular mechanical cues.

Altered biomechanics affects ERK1/2 activation, calcium distribution, and stem cell physiology in hESC colony

We next investigated the effect of Plexin-B2 on stem cell state. Comparative analysis of differentially engaged signaling pathways in PLXNB2 KO or OE hESCs relative to WT indicated activation of ERK/MAPK and calcium signaling (Fig. 7g). We, therefore, assessed ERK1/2 activation by WB, which indeed showed elevated levels of phosphorylated ERK1/2 in PLXNB2 OE hESCs relative to WT or KO cells (Figs. 7h and S10d). Again, the effect of Plexin-B2 OE on ERK1/2 activation could be reverted by expression of CA RAP1/2; and conversely, expression of DN RAP1/2 led to a marked increase of ERK1/2 activation in all three genotypes (Figs. 7h and S10d), further supporting RAP1/2 as a downstream effector of Plexin-B2 in this regard.

We next performed live calcium imaging of hESC colonies, which revealed a distinct pattern of cytosolic calcium levels—higher at colony periphery and lower in colony interior—in agreement with the higher traction forces at colony edges6 (Fig. 7i). Notably, PLXNB2 KO and OE disrupted the spatial pattern of calcium within the colonies, echoing the disarray of actomyosin networks. Furthermore, calcium signals were in general elevated in PLXNB2 OE cells (Fig. 7i).

Interestingly, the altered biomechanical properties of hESC colonies from Plexin-B2 manipulations also affected the orientation of mitotic spindles at the colony edge. In WT and PLXNB2 OE colonies, the cell division planes at the colony periphery were largely oriented perpendicular to the colony rim, in alignment with in-plane traction forces, but they were randomly oriented at the colony center (Fig. S11). In contrast, cell division planes in KO colonies were largely randomized in all areas (Fig. S11). Hence, distinct mechanical niches as orchestrated by Plexin-B2 govern mitotic spindle orientation in hESC colonies.

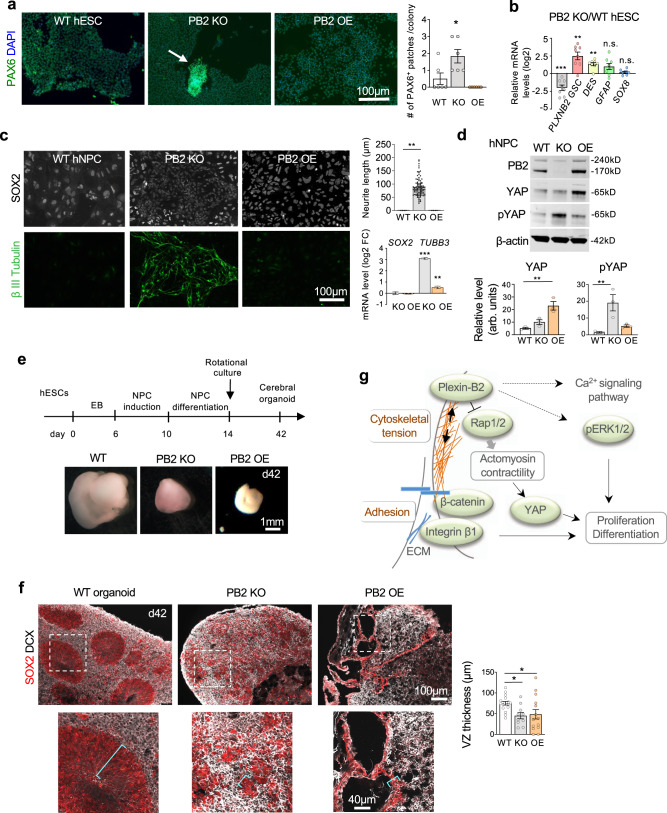

Colony integrity is an indicator of the stemness state of hESCs8. Although hESCs continued to express the pluripotency factors SOX2, OCT4, and NANOG in PLXNB2 KO or OE colonies (Fig. S12a), we found that Plexin-B2-deficient colonies harbored small patches of cells expressing neural stem cell marker PAX6, indicating premature neural lineage differentiation (Figs. 8a and S12b). By comparison, Plexin-B2 OE did not cause premature induction of PAX6. Indeed, our RNA-seq data confirmed that PLXNB2 KO hESCs upregulated genes related to ectoderm differentiation, dopamine neurogenesis, and neural crest differentiation, indicative of premature neuronal differentiation in KO colonies, while PLXNB2 OE cells upregulated genes related to mesodermal commitment and cardiac progenitor differentiation (see Fig. S2a).

Fig. 8. Plexin-B2 affects stem cell differentiation and neuroepithelial architecture.

a IF images and quantification show small patches of PAX6+ cells in Plexin-B2 deficient hESC colonies (arrow). One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. n = 6 colonies per group. *P = 0.019. Data represent mean ± SEM. b qRT-PCR results confirm induction of marker genes for differentiation in Plexin-B2 deficient hESCs relative to WT. Note the verification of reduced PLXNB2 expression in KO cells. Two-sided unpaired t-test. n = 8 samples per group. **P = 0.0036 (for GSC), **P = 0.0015 (DES), and ***P = 0.0002 (PLXNB2). n.s. not significant. Data represent mean ± SEM. c IF images show increased expression of β-III tubulin at the expense of SOX2 in PLXNB2 KO hNPCs derived from hESCs (clone KO#2). Quantifications show enhanced neurite length (visualized by β-III tubulin IF) in PLXNB2 KO cells as compared to WT or PLXNB2 OE cells. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test versus WT. n = 4 random fields per group. **P = 0.0014. Right, qRT-PCR results show relative transcript levels of SOX2 and TUBB3 in PLXNB2 KO and OE hNPCs relative to WT. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test versus WT. n = 3 samples per group. **P = 0.0048; ***P < 0.0001. Data represent mean ± SEM. d WBs show levels of total YAP and pYAP in hNPCs in dependence of Plexin-B2. β-actin as a loading control. arb.units arbitrary units. One-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. n = 3 samples per group. For YAP, **P = 0.0026. For pYAP, **P = 0.0085. Data represent mean ± SEM. e Timeline of cerebral organoid derivation from hESCs. Images show smaller size of cerebral organoids with Plexin-B2 perturbation relative to WT at matching time points (day 42). f IHC images show SOX2+ neuroprogenitors and DCX+ neuroblasts residing in ventricular structures in WT cerebral organoids, but in disarray in mutants. Magnified images are shown below, with brackets marking ventricular zone (VZ) thickness, as quantified in bar graphs on the right. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test versus WT. n = 17, 10, 14 ventricular zones for WT, KO, and OE, respectively. *P = 0.042 (WT vs. KO) and *P = 0.047 (WT vs. OE). Data represent mean ± SEM. g Model of the link of Plexin-B2 signaling with mechanoregulation and stem cell functions.

For corroboration of premature lineage commitment in PLXNB2 KO hESCs, we carried out qRT-PCR array assays on the expression of a set of stem cell and differentiation markers. Around 90% of these markers exhibited no significant transcriptional alteration in PLXNB2 KO relative to WT hESCs, including ESC markers OCT4, NANOG, and SOX2 (Fig. S12c). Of the remaining 10% markers that showed transcriptional changes, notably all displayed upregulation in PLXNB2 KO cells, including markers for the three germ layers: i.e., GSC (endoderm), DES (mesoderm), as well as neural markers, e.g., GFAP and SOX8 (Fig. S12c), which were further confirmed by qRT-PCR (Fig. 8b).

Plexin-B2 affects the proliferation and differentiation of hNPCs and neuroepithelial cytoarchitecture

We next studied the effect of Plexin-B2 on hNPC biology. We found that as in hESCs, PLXNB2 KO also resulted in reduced proliferation of hNPCs, while PLXNB2 OE did not further enhance the already high proliferative state of hNPCs (Fig. S13a).

Upon neural induction of hESCs, Plexin-B2 deficient cells consistently displayed accelerated neuronal differentiation compared to WT counterparts, as evidenced by enhanced induction of the neuroblast marker doublecortin (DCX) and the neuronal marker β-III tubulin, and reduced expression of NPC markers PAX6 and SOX2 (Figs. 8c and S13b, c). Analyses by qRT-PCR confirmed upregulation of TUBB3 (encoding β-III tubulin) in PLXNB2 KO cells, whereas PLXNB2 OE did not cause accelerated neuronal differentiation (Fig. 8c).

In addition, WB also showed a response of YAP to Plexin-B2 manipulation in hNPCs, with higher pYAP levels (signifying inactivation) in PLXNB2 KO cells, but elevated YAP levels in OE cells (Fig. 8d). We further tested the effect of β-catenin or YAP inhibitors on neural induction (Fig. S13d). For β-catenin inhibition with cardamonin, we observed no overt effects on neuronal differentiation in either of the three groups, with PLXNB2 KO cells similarly displaying enhanced neuronal differentiation with or without cardamonin exposure. For YAP inhibition with VP, we observed that limited VP exposure indeed promoted neuronal differentiation for WT and PLXNB2 OE cells, a phenotype similar to Plexin-B2 KO. These data provide additional support for a link of Plexin-B2 and YAP in controlling stem cell differentiation.

To further probe the role of Plexin-B2 in neuroepithelial tissue morphogenesis, we generated 3D cerebral organoids from hESCs using a forebrain organoid differentiation protocol66,67. After 6 weeks of culture, layered cortical structures emerged in cerebral organoids, with ventricular zones occupied by neuroprogenitors (SOX2+) and cortical plate-like zones occupied by differentiating neuroblasts (DCX+) (Fig. 8e, f).

Cerebral organoids derived from PLXNB2 KO or OE hESCs were consistently smaller than WT organoids (Fig. 8e). Histological analysis of organoid cross sections revealed severe disruption of neuroepithelial cytoarchitecture in mutant organoids, e.g., absence of organized ventricular structures, which were replaced with numerous simple cysts in PLXNB2 KO organoids, and large cystic structures with stretched and irregular contours in OE organoids (Fig. 8f). Notably, both SOX2+ and DCX+ cells were present in mutant organoids, albeit in spatial disarray (Fig. 8f). The disorganization of neuroepithelium was also reflected by the disarray of the actomyosin network, activated integrin β1, pFAK, as well as junctional N-cadherin, corresponding to Plexin-B2 manipulations (Fig. S13e). Thus, Plexin-B2 is not strictly required for neural induction per se, but affects cellular alignment and architectural integrity during neuroepithelial morphogenesis.

Discussion

The multicellular organization relies on force-mediated processes that orchestrate cytoskeletal organization across cells in order to keep individual cells in a certain shape while maintaining tissue cohesion and structural integrity68. The signaling pathways that transmit external guidance cues into cytoskeletal tension and collective formation of actomyosin network and adhesive complexes need to be better mapped.

Here, we provided multiple lines of evidence to support the role of the guidance receptor Plexin-B2 in orchestrating actomyosin cytoskeletal network and cell–cell adhesion during multicellular development of hESCs and hNPCs. This impacts signaling pathways of β-catenin, YAP, ERK1/2, and calcium, all critical for stem cell physiology (Fig. 8g). From a mechanical perspective, the correlation between the experimental AFM data and mathematical simulations indicated that Plexin-B2 primarily promotes actomyosin contractility, which in turn affects tensile forces exerted on cell–cell junctions and cell–matrix adhesion sites, underscoring the interconnectedness of these mechanical elements8,69,70. The fundamental mechanoregulatory function of Plexin-B2 is consistent with an early evolutionary appearance of semaphorins and plexins at the transition from unicellular to multicellular organisms to adjust cytoskeletal tension and adhesion strength29.

From a signaling perspective, we found that the extracellular and the Ras-GAP domains of Plexin-B2 are indispensable to rescue the KO phenotypes, in agreement with a high degree of evolutionary conservation of these domains29. Plexin-B2 can be activated by class 4 semaphorins71; however, whether the mechanoregulatory function of Plexin-B2 requires semaphorins need further studies. In this context, it is notable that a semaphorin-independent mechanosensory function of Plexin-D1, a paralog of Plexin-B2, has recently been reported in endothelial cells, and this involves the bending of its extracellular domain in response to blood flow shear stress72. Whether this applies to Plexin-B2 in regulating multicellular organization awaits future studies, but it is worth noting that the current study and the earlier study72 converge on the mechanical effects of Plexins in inducing cytoskeletal changes, calcium surge, and ERK1/2 activation.

The effects of Plexin-B2 on stem cell physiology may be linked to YAP and β-catenin signaling. We demonstrated that YAP can respond to Plexin-B2-mediated cytoskeletal tension, and can itself mediate cytoskeletal dynamics. Consistently, YAP mutation in fish models results in flattening of the body, indicating a requirement of YAP for tissue integrity47. Our study also established Rap1/2 as downstream effectors of Plexin-B2 in orchestrating actomyosin network, YAP, and ERK1/2 activation, as well as stem cell proliferation in hESC colonies. Intriguingly, Rap2A has been shown as a key intracellular signal transducer that relays ECM rigidity to YAP/TAZ7. This raises a tantalizing possibility that Rap1/2 may relay mechanical information from Plexin-B2 to YAP.

Interestingly, Worzfeld and colleagues have recently implicated Plexin-B1 and -B2 in mechanosensing during epidermal development to detect compressive forces, such as those elicited by cell confluency, resulting in YAP inactivation18. This study and ours converge on the roles of Plexins in enhancing the stiffness of cortical actin cytoskeleton, stabilizing cell–cell adhesive complexes, and conferring mechanosensitivity. However, perhaps reflecting tissue-specific roles, the two studies diverge on the way Plexin-B2 controls YAP activation and thereby cell proliferation and contact inhibition: while in hESCs, Plexin-B2 deletion resulted in decreased nuclear YAP and reduced proliferation, in epidermal stem cells, loss of Plexin-B1 and -B2 led to increased nuclear YAP and over-proliferation18. Two observations may explain these divergent functions: First, differentiation states of epidermis and hESCs are different; second, whereas epidermis responds to biomechanical constraints from compressive forces in confluent cell layers, human PSCs are insensitive to such contact inhibition64.

From a developmental point of view, our data solidify the principle that mechanical forces and tissue architecture provide an overarching signal to inform cell fate decisions73. Our data showed that Plexin-B2 deletion reduces cell-intrinsic stiffness of hESCs and hNPCs, and this is associated with neuronal cell fate commitment. This echoes a previous report that soft matrix substrate promotes neural differentiation of hESCs, while stiff substrate does not affect the pluripotency state74. Interestingly, in mesenchymal stem cells, the lineage specification is also sensitive to tissue elasticity, with softer matrix promoting neuronal while stiffer matrix promoting muscle differentiation75. Hence, cytoskeletal tension as controlled by Plexin-B2 exerts similar effects on cell fate commitment as substrate stiffness. Our study may thus point to strategies to accelerate neuronal differentiation by manipulating intrinsic cell mechanics.

The mechanoregulatory function of Plexin-B2 is more critical for structurally complex tissues such as ventricular zones and neuroepithelium. In cerebral organoids, Plexin-B2 perturbation caused ventricular malformation, reminiscent of the neural tube closure defect seen in Plxnb2 KO mice12, and echoing earlier reports that neural tube closure defect can arise from dysregulated mechanical interactions and tissue tension, thereby impacting cellular alignment and NPC function10. Our study also has implications for development and cancer. Indeed, reduced Plexin-B2 activity has been suspected to contribute to the neurodevelopmental phenotypes of Phelan-McDermid syndrome (22q13 deletion)76. In breast cancer and glioblastoma, Plexin-B2 is upregulated and promotes tumor growth and invasion77,78. Resonating with our current study, we have also recently demonstrated that Plexin-B2 provides the biomechanical dynamics required for invasive growth of glioblastoma cells17.

In sum, our study identified a critical role of Plexin-B2 in organizing the actomyosin network and cytoskeletal tension during the multicellular organization of hESCs and hNPCs. Our data underscore the importance of force-mediated processes in controlling proliferation, cell fate specification, and tissue morphogenesis. Our findings may have broad implications for understanding neurodevelopmental disorders, tissue repair, and cancer biology.

Methods

hESC culture

All culture experiments were conducted using the WA09 (H9) hESC79 line obtained from the University of Wisconsin and validated at the Mount Sinai Stem Cell core facility. The Mount Sinai Stem Cell core conducts routine quality controls by verifying karyotype and mycoplasma-free status for all stem cell lines. Briefly, H9 hESC were seeded on matrigel-coated cell culture dishes (1:100, Corning) and grown in mTeSR1 medium (STEMCELL Technologies). Cells were passaged around every 5 days by dissociation with Accutase (BD Biosciences) and addition of 2.5 μM Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) inhibitor Thiazovivin (Millipore). The experiments were conducted at early hESC passages (P1 or P2) upon viral infections. The study was approved by the Embryonic Stem Cell Research Oversight Committee (ESCRO) at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

CRISPR genome editing for Plexin-B2 knockout

The CRISPR/Cas9-sgRNA sequence targeting PLXNB2 exon 3 was embedded inside a CRISPR/Cas9 lentivirus plasmid80,81 to generate plentiCRISPRv2-sgPLXNB2 (target sequence: GTTCTCGGCGGCGACCGTCA). Lentiviral particles were produced in HEK293T cells (Takara, no. 632180) by co-transfection of lentiviral plasmid, envelope plasmid pMD2.G, and packaging plasmid psPAX2 (Addgene plasmids #12259 and #12260; deposited by Didier Trono, EPFL Lausanne). Low passage hESCs transduced with the lentivirus were selected with puromycin (1 µg/ml) for 7 days. Successful knockout of Plexin-B2 was confirmed by WB, demonstrating the absence of mature Plexin-B2 (170 kDa). A lentiviral vector (plentiCRISPRv2-sgEGFP) expressing sgRNA targeting eGFP (target sequence: GGGCGAGGAGCTGTTCACCG) was used as control (WT).

Plasmids cloned for this study have been deposited at Addgene (“Roland Friedel Lab Plasmids”; https://www.addgene.org/Roland_Friedel/).

CRISPR clones sequencing and karyotyping

To isolate clonal lines of hESCs that carry defined CRISPR mutations, after cells were transduced with lentiviruses (either targeting Plexin-B2 or EGFP as control) and selected with puromycin as described above, three colonies were picked, expanded, and sequenced for verifying mutations at the PLXNB2 locus. Three PB2 KO and its respective WT clones were confirmed. Normal karyotypes of selected clonal lines were confirmed by chromosome G-banding at Mount Sinai Genetic Testing Laboratory Sema4 (New York, USA).

Lentiviral vectors for Plexin-B2 rescue, overexpression, and signaling mutants

For rescue experiments, human PLXNB2 cDNA (entry clone HsCD00399262, DNA Resource Core at Harvard Medical School) was modified by site-directed mutagenesis to generate a CRISPR-resistant PLXNB2 cDNA, which was inserted into the lentiviral vector pLenti-PGK (plasmid backbone pLENTI-PGK Neo DEST, Addgene #19067; deposited by Eric Campeau & Paul Kaufman) by Gateway LR Clonase II (Thermo Fischer Scientific). The resulting vector pLV-PLXNB2 was then used to generate lentiviruses to transduce PLXNB2 KO hESCs for rescue/structural mutants’ experiments. The pLV-PLXNB2 without CRISPR-resistant mutation was used to generate lentivirus for overexpression experiments by transducing H9 hESCs.

The mutations in functional domains of Plexin-B2 were generated in the CRISPR-resistant PLXNB2 cDNA plasmid using the Phusion Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Thermo Fischer): mGAP (mutation in the GAP domain: R1391A, R1392G), mRBD (mutation in the RBD domain: LSK 1558–1560 -> GGA), ∆VTDL (deletion of four last C-terminal amino acids VTDL of PDZ binding motif), and ∆ECTO (lacking extracellular domain, deletion of amino acids 30-1189). The mutant cDNAs were transferred into pLenti-PGK destination vector by Gateway cloning as described above.

Doxycycline-inducible Plexin-B2 overexpression and shRNA KD

A plasmid for a lentiviral vector for doxycycline (Dox)-inducible human Plexin-B2 overexpression was generated by inserting human PLXNB2 cDNA by Gateway cloning into pLenti-CMVtight-Puro DEST (Addgene #26430). Target cells were coinfected with a lentivirus expressing Tet-On 3 G transactivator protein and hygromycin resistance (VectorBuilder, VB160122 -10094). Stable PLXNB2 Tet-On hESC lines were established by puromycin (1 μg/ml) and hygromycin (200 μg/ml) selection of coinfected cells.

Temporally controlled KD of Plexin-B2 at different phases of hESC colony expansion was achieved with TET-ON lentiviral vectors (Tet-pLKO-Puro backbone, Addgene #21915, deposited by Dimitri Wiederschain) expressing Dox-inducible shRNA targeting PLXNB2 and puromycin resistance marker (pLKO-Tet-On-PLXNB2–shRNA1 and –shRNA2). A non-targeting shRNA vector (pLKO-Tet-On-shRNA-Control) served as control (oligonucleotides used for construction of shRNA vectors are listed in file Supplementary Data 1). Stable PLXNB2 shRNA lines were established by puromycin selection (1 μg/ml) over 7 days. The PLXNB2 overexpression and the shRNA-mediated PLXNB2 KD were induced by adding 1 μg/ml Dox (MP Biomedicals) to the culture medium.

Doxycycline-inducible YAP overexpression and shRNA KD constructs

DNA plasmids for lentiviral vectors with doxycycline-inducible human YAP1 and YAP1-5SA cDNAs were generated by VectorBuilder, Inc.. Plasmids were designed using VectorBuilder website tools. In brief, human YAP1 plasmid was designed using an mRNA sequence from NCBI transcript NM_001282101, and human YAP1-5SA was designed based on ref. 82 to generate an unphosphorylated CA form of YAP1. Both WT and mutant YAP1 plasmids are driven by a TRE3G promoter and have a CMV-puromycin-T2A-mCherry cassette inserted after the gene of interest to facilitate the selection of transfected cells. Target cells were coinfected with a lentivirus expressing Tet-On 3G transactivator protein and hygromycin resistance (VectorBuilder, VB160122 -10094).

YAP short hairpin (sh)RNA lentiviral expression vectors were cloned by ligating oligonucleotides encoding the shRNA hairpins (Integrated DNA Technologies) into the pLKO-Tet-On vector (Addgene #21915) to have temporal control of YAP1 KD (oligonucleotide sequences are listed in file Supplementary Data 1). All plasmids were validated using restriction enzymes and Sanger sequencing (Macrogen) using the primer pLKO-shRNAseq (ggcagggatattcaccattatcgtttcaga).

Lentiviral constructs for RAP1/2 small GTPases

To validate the relevance of the Ras family of small GTPases, human RAP2A cDNA was modified to generate a CA (RAP2A-V12) and DN (RAP2A-N17) isoforms using site-directed mutagenesis (Thermo Fischer). The RAP2A isoforms were then inserted into the lentiviral vector pLenti-PGK Neo or Puro DEST by Gateway LR Clonase II (Thermo Fischer). For RAP1B, CA (bovine Flag-RAP1B-V12, Addgene #118323) and DN (bovine Flag-Rap1B-N17, Addgene #118322) were inserted into the same lentiviral vectors as described above for RAP2A. The resulting vectors were used to transduce WT, PB2 KO, and PB2 OE hESCs.

hESC colony and 3D aggregation assays