Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Neurofilament light (NFL) reflects neuroaxonal damage and is implicated in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Little is known about NFL in pre-MCI stages, such as in individuals with objectively-defined subtle cognitive difficulties (Obj-SCD).

METHODS:

294 participants from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative underwent baseline blood draw and serial neuropsychological testing over 5 years of follow-up.

RESULTS:

Individuals with Obj-SCD and MCI showed elevated baseline plasma NFL relative to the cognitively normal (CN) group. Across the sample, elevated NFL predicted faster rate of cognitive and functional decline. Within the Obj-SCD and MCI groups, higher NFL levels predicted faster rate of decline in memory and preclinical AD composite score compared to the CN group.

DISCUSSION:

Findings demonstrate the utility of plasma NFL as a biomarker of early AD-related changes, and provide support for the use of Obj-SCD criteria in clinical research to better capture subtle cognitive changes.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, neurofilament light, early detection, mild cognitive impairment, subtle cognitive decline

1. INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) biomarkers can assist in characterizing disease presence and severity and monitoring effects of disease-modifying treatments. Blood-based measures have strengths including being minimally invasive, cost-effective, and feasible across settings [1, 2].

Neurofilaments (NFs), a structural component of the neural cytoskeleton, are present in dendrites and perikaryal and are especially abundant in axons [3]. Given that any pathological process resulting in neuronal death or axonal damage should lead to NF proteins being released into extracellular fluid, increased biofluid concentrations of NF proteins are not specific to one disease but rather represent a general index of neurodegeneration [1]. NFs have subunits (heavy, medium, and light), and most research in neurodegenerative conditions has focused on the light subunit (NFL) [1]. Few studies, however, have examined associations of NFL with neuropsychological performance [4] and it remains unknown how NFL relates to longitudinal cognitive decline.

Subtle objective cognitive changes can be captured during the preclinical phase of AD using sensitive neuropsychological measures, and these measures add prognostic value in predicting decline above and beyond traditional AD biomarkers [5]. Neuropsychological process scores quantify the number and types of errors that an individual produces on a neuropsychological test, or the approach used on a task, and are distinct from the traditionally used overall total score [6]. Process scores have been used to detect cognitive inefficiencies prior to dementia onset [5]. Our previous work using process scores to classify objective subtle cognitive decline (Obj-SCD) shows that those with Obj-SCD have cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and positron emission tomography (PET) AD biomarker abnormalities intermediate between cognitively normal (CN) and MCI participants [7, 8], suggesting that Obj-SCD can be detected coincident with accumulating amyloid and tau pathology. However, how Obj-SCD status relates to blood-based biomarkers including plasma NFL is unknown. Therefore, we examined whether individuals with Obj-SCD show elevated plasma NFL cross-sectionally, and whether baseline plasma NFL predicts cognitive trajectories.

2. METHOD

2.1. ADNI Dataset

Data used in preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu). The ADNI was launched in 2003 as a public-private partnership, led by Principal Investigator Michael W. Weiner, MD. For up-to-date information, see www.adni-info.org.

2.2. Participants

The current study included 294 participants from ADNI1 [9]. Participants were included if they were free of dementia at their first study visit; had available NFL, neuropsychological, and covariate data at their baseline visit; and serial neuropsychological data. ADNI was approved by institutional review boards at participating institutions and informed consent was obtained.

2.3. Cognitive groups

Jak/Bondi actuarial neuropsychological MCI criteria were applied to classify participants as CN or MCI [10]. Actuarial neuropsychological Obj-SCD criteria were then applied to participants without MCI. Participants were considered to have Obj-SCD if they performed >1 SD below the age-/education-/sex-adjusted mean on (1) 1 impaired total test score in 2 different cognitive domains (memory, language, attention/executive), or (2) 2 impaired neuropsychological process scores from Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test, or (3) 1 impaired total test score and 1 impaired process score [7, 8]. Detailed descriptions of criteria are presented in supplementary materials.

2.4. Plasma NFL measurements

Plasma NFL was analyzed with the Single Molecule array (Simoa) technique. All samples were measured in duplicate, except for one (due to technical reasons). Analytical sensitivity was <1.0 pg/mL. Values are presented as pg/mL.

2.5. Neuropsychological Composite Scores

Composite scores for specific domains of memory, language, executive functioning, and visuospatial abilities were developed within ADNI [11, 12]. In addition, a composite score measuring early cognitive changes in AD thought to reflect amyloid-related decline (modified Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite [mPACC]) [13] was calculated. Detailed descriptions of composites are presented in supplementary materials.

2.6. Everyday Functioning

The Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ), an assessment of instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), was completed by each participant’s study partner at baseline and annual follow-up visits. The partner rated each participant’s difficulties in the past 4 weeks on 10 tasks (e.g., paying bills) using a 4-point scale: 0 (normal), 1 (has difficulty but does by self), 2 (requires assistance), or 3 (dependent). FAQ total score was calculated as the sum of the 10 individual scores, with higher scores indicating greater difficulty [14].

2.7. Covariates

Apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 allele frequency (0, 1, 2) was determined. CSF markers were processed using Elecsys® immunoassays; AD biomarker positivity was determined using a published CSF p-tau/Aβ ratio cut-score [15].

2.8. Statistical analyses

The distribution of plasma NFL was skewed, so a natural log transformation was used. An ANCOVA examined group differences in baseline NFL adjusting for age, sex, APOE ε4 allele frequency, and CSF p-tau/Aβ positivity.

Multivariable linear mixed effects (LME) modeling using full information maximum likelihood estimation was used to examine 5-year trajectories of change in cognition and IADLs as a function of baseline NFL in nested models. Longitudinal models adjusted for age, education, sex, APOE ε4 allele frequency, and CSF p-tau/Aβ positivity and included main effects of group (CN, Obj-SCD, or MCI), baseline NFL, and time, as well as the baseline NFL x time interaction. We then ran models adding the three-way interaction of baseline NFL x group x time as well as the two-way interactions of group x time, baseline NFL x time, and baseline NFL x group. Random intercept and slope were included.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Participant Characteristics

Table 1 shows characteristics by group (CN: n=81, Obj-SCD: n=46, MCI: n=167). As expected, at baseline, across most neuropsychological measures, MCI performed worst, followed by Obj-SCD, and then CN. In addition, MCI had greater functional difficulties although CN and Obj-SCD groups did not differ from each other. In terms of annual change, MCI showed greater decline compared to Obj-SCD and CN groups on memory, executive function, language, and preclinical Alzheimer cognitive composites and IADLs. The Obj-SCD group showed greater annual decline in IADLs relative to the CN group.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics by cognitive group status

| Total Sample N=294 | CN N=81 | Obj-SCD N=46 | MCI N=167 | F or χ2 | p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Baseline characteristics | Mean or % | SD | Mean or % | SD | Mean or % | SD | Mean or % | SD | ||

|

|

||||||||||

| Age | 74.88 | 6.75 | 75.65 | 6.14 | 75.59 | 6.80 | 74.31 | 6.99 | F=1.39 | .252 |

| Education | 15.78 | 2.89 | 15.88 | 2.79 | 16.22 | 2.72 | 15.61 | 2.99 | F=0.86 | .426 |

| Female, % | 38.4% | - | 45.7% | - | 32.6% | - | 36.5% | - | χ2=2.71 | .258 |

| APOE ε4 allele frequency | χ2=22.04 | <.001 | ||||||||

| 0 | 56.8% | - | 75.3% | - | 63.0% | - | 46.1% | - | - | - |

| 1 | 35.3% | - | 21.0% | - | 34.8% | - | 42.5% | - | - | - |

| 2 | 7.8% | - | 3.7% | - | 2.2% | - | 11.4% | - | - | - |

| CSF p-tau/Aβ+, % | 59.5% | - | 33.3% | - | 45.7% | - | 76.0% | - | χ2=45.66†‡ | <.001 |

| mPACC | −4.97 | 4.64 | −0.63 | 3.23 | −3.22 | 3.22 | −7.56 | 3.73 | F=115.52 *†‡ | <.001 |

| Memory | 0.26 | 0.76 | 1.06 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.47 | −0.20 | 0.54 | F=165.57 *†‡ | <.001 |

| Language | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.88 | 0.66 | 0.29 | 0.51 | −0.15 | 0.70 | F=66.46 *†‡ | <.001 |

| Executive Function | 0.16 | 0.86 | 0.82 | 0.62 | 0.29 | 0.57 | −0.19 | 0.83 | F=51.48 *†‡ | <.001 |

| Visuospatial Abilities | −0.07 | 0.75 | 0.22 | 0.64 | 0.00 | 0.65 | −0.23 | 0.78 | F=10.97 †‡ | <.001 |

| FAQ | 2.52 | 4.02 | 0.32 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 1.42 | 4.08 | 4.73 | F=35.35 †‡ | <.001 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Follow-up characteristics (annual change) | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

|

|

||||||||||

| mPACC | −0.89 | 0.91 | −0.29 | 0.50 | −0.62 | 0.89 | −1.26 | 0.89 | F=43.04 †‡ | <.001 |

| Memory | −0.09 | 0.08 | −0.05 | 0.07 | −0.06 | 0.08 | −0.11 | 0.08 | F=21.48 †‡ | <.001 |

| Language | −0.10 | 0.08 | −0.06 | 0.06 | −0.08 | 0.08 | −0.13 | 0.08 | F=23.71 †‡ | <.001 |

| Executive Function | −0.10 | 0.07 | −0.06 | 0.05 | −0.08 | 0.05 | −0.12 | 0.07 | F=31.10 †‡ | <.001 |

| Visuospatial Abilities | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.03 | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.06 | 0.04 | F=3.44 | .033 |

| FAQ | 1.45 | 1.38 | 0.52 | 0.66 | 1.21 | 1.29 | 1.97 | 1.42 | F=38.91 *†‡ | <.001 |

statistic reported for one-way ANOVAs

statistic report for chi-square tests.

significant differences between CN and Obj-SCD

significant differences between CN and MCI

significant difference between Obj-SCD and MCI

CN = Cognitively normal; Obj-SCD = Objectively-defined subtle cognitive difficulties; MCI = mild cognitive impairment; APOE = apolipoprotein E; CSF=cerebrospinal fluid; p-tau = phosphorylated tau; Aβ = amyloid beta; mPACC = modified Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite; FAQ = Functional Activities Questionnaire

3.2. Baseline NFL

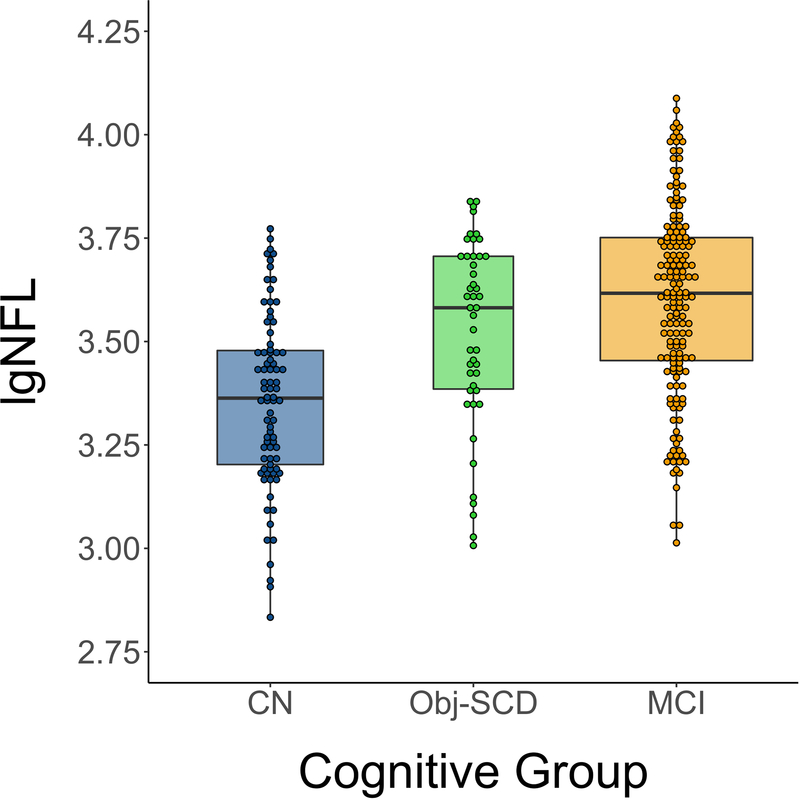

Adjusting for age, sex, APOE ε4 allele frequency, and CSF p-tau/Aβ positivity, there was a main effect of cognitive group on baseline NFL (F2, 293=7.50, p=.001). Pairwise comparisons showed that, relative to the CN group, the MCI group had significantly higher NFL (p<.001) and the Obj-SCD group had marginally significantly higher NFL (p=.050). Obj-SCD and MCI groups did not differ from each other (p=.227). Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Baseline NFL by cognitive group

Dot-box plot showed predicted NFL from ANCOVA models adjusting for age, sex, APOE ε4 allele frequency, and CSF p-tau/Aβ positivity.

lgNFL = log transformed neurofilament light; CN = cognitively normal; Obj-SCD = objectively-defined subtle cognitive difficulties; MCI = mild cognitive impairment.

3.3. Cognitive Trajectories

Adjusting for age, sex, education, APOE ε4 allele frequency, and CSF p-tau/Aβ positivity, there was a significant interaction between baseline NFL and time such that elevated baseline NFL predicted faster rate of decline on memory, language, executive function, and preclinical composite scores as well as increasing functional difficulties (ps≤.013). The interaction between NFL and time was not significant for the visuospatial composite (p=.997). Supplementary materials Table S1 and Figure S1.

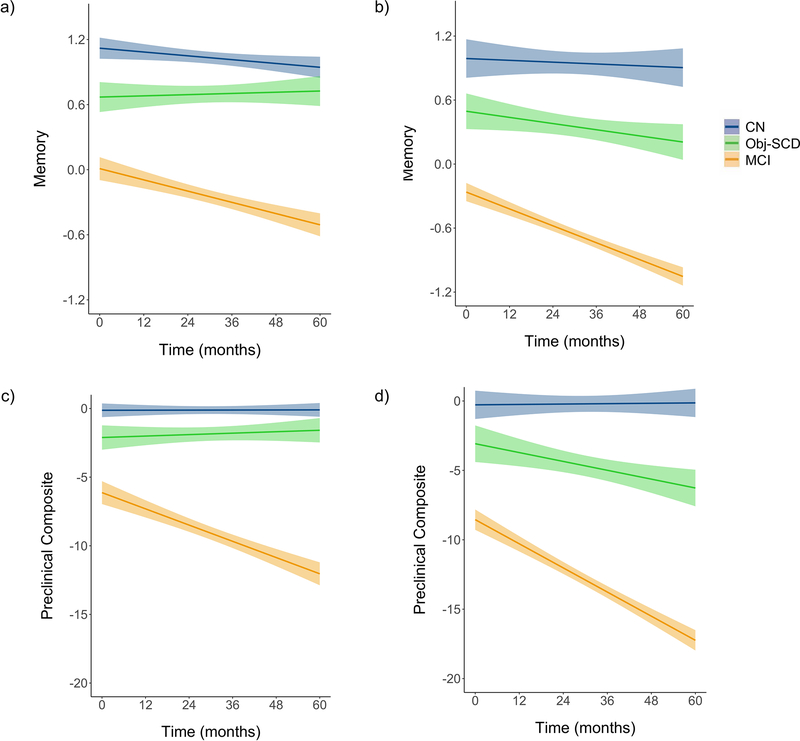

We then ran models to determine whether cognitive group moderated the NFL x time interaction. There was a significant three-way interaction between group, NFL, and time such that, relative to CN participants, elevated baseline NFL predicted faster rates of decline in memory and preclinical composite scores in participants with Obj-SCD (ps<.05) and MCI (ps<.05). The memory and preclinical composite trajectories did not differ between the Obj-SCD and MCI groups. Cognitive group did not moderate the NFL x time interaction for language, executive function, or visuospatial scores or for FAQ (ps>0.05). Table 2 and Figure 2.

Table 2.

Estimates for change in cognitive domain composites as a function of baseline NFL and cognitive group

| Memory | Language | Executive Function | Visuospatial Skills | Preclinical Composite | Daily Functioning | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | S.E. | p | b | S.E. | p | b | S.E. | p | b | S.E. | p | b | S.E. | p | b | S.E. | p | |

| Intercept | 1.042 | 0.083 | <.001 | 0.974 | 0.100 | <.001 | 1.042 | 0.106 | <.001 | 0.243 | 0.086 | .005 | 0.985 | 0.636 | .123 | −0.127 | 0.820 | .878 |

| Age | 0.038 | 0.037 | .307 | −0.079 | 0.044 | .072 | −0.079 | 0.046 | .085 | 0.034 | 0.036 | .340 | 0.367 | 0.277 | .188 | −0.455 | 0.368 | .217 |

| Education | 0.091 | 0.036 | .012 | 0.115 | 0.043 | .008 | 0.135 | 0.045 | .003 | 0.145 | 0.035 | <.001 | 0.642 | 0.271 | .019 | 0.237 | 0.358 | .509 |

| Female | 0.175 | 0.073 | .018 | −0.015 | 0.087 | .863 | 0.046 | 0.091 | .613 | 0.075 | 0.070 | .288 | 0.805 | 0.550 | .146 | −0.302 | 0.726 | .678 |

| APOE ε4 allele frequency | ||||||||||||||||||

| 0 (ref) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 1 | −0.241 | 0.084 | .004 | −0.187 | 0.099 | .061 | 0.013 | 0.104 | .903 | −0.093 | 0.081 | .251 | −1.990 | 0.629 | .002 | 1.292 | 0.833 | .122 |

| 2 | −0.426 | 0.143 | .003 | −0.315 | 0.169 | .064 | 0.055 | 0.177 | .756 | −0.058 | 0.137 | .670 | −3.077 | 1.073 | .005 | 2.933 | 1.409 | .038 |

| CSF p-tau/AB | −0.288 | 0.087 | .001 | −0.174 | 0.102 | .092 | −0.514 | 0.108 | <.001 | −0.139 | 0.083 | .095 | −3.141 | 0.649 | <.001 | 3.484 | 0.857 | <.001 |

| Cognitive group | ||||||||||||||||||

| CN (ref) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| SCD | −0.411 | 0.115 | <.001 | −0.580 | 0.140 | <.001 | −0.554 | 0.148 | <.001 | −0.181 | 0.126 | .153 | −2.886 | 0.891 | .001 | 2.464 | 1.136 | .031 |

| MCI | −1.292 | 0.093 | <.001 | −1.354 | 0.113 | <.001 | −1.354 | 0.119 | <.001 | −0.566 | 0.100 | <.001 | −9.893 | 0.718 | <.001 | 7.867 | 0.922 | <.001 |

| Time | −0.059 | 0.033 | .078 | −0.058 | 0.041 | .163 | −0.001 | 0.045 | .980 | −0.010 | 0.051 | .840 | 0.029 | 0.287 | .919 | 0.665 | 0.413 | .109 |

| NFL | −0.040 | 0.073 | .585 | −0.010 | 0.089 | .910 | 0.033 | 0.094 | .723 | 0.060 | 0.077 | .433 | −0.191 | 0.566 | .736 | 0.584 | 0.722 | .419 |

| NFL × Time | 0.028 | 0.032 | .382 | −0.017 | 0.040 | .680 | −0.007 | 0.044 | .880 | 0.042 | 0.049 | .398 | −0.004 | 0.283 | .999 | 0.230 | 0.412 | .578 |

| Cognitive group × NFL | ||||||||||||||||||

| CN × NFL (ref) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| SCD × NFL | −0.131 | 0.113 | .247 | −0.186 | 0.137 | .178 | −0.095 | 0.145 | .519 | 0.021 | 0.127 | .869 | −1.511 | 0.873 | .085 | 1.034 | 1.106 | .350 |

| MCI × NFL | −0.242 | 0.085 | .005 | −0.341 | 0.103 | .001 | −0.283 | 0.110 | .010 | −0.172 | 0.091 | .059 | −2.455 | 0.659 | <.001 | 1.554 | 0.839 | .065 |

| Cognitive group × Time | ||||||||||||||||||

| CN × Time (ref) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| SCD × Time | −0.003 | 0.056 | .953 | −0.036 | 0.070 | .606 | −0.097 | 0.077 | .212 | −0.017 | 0.087 | .845 | −0.731 | 0.482 | .132 | 1.777 | 0.684 | .010 |

| MCI × Time | −0.238 | 0.041 | <.001 | −0.301 | 0.052 | <.001 | −0.394 | 0.057 | <.001 | −0.192 | 0.063 | .003 | −3.322 | 0.356 | <.001 | 4.135 | 0.509 | <.001 |

| Cognitive group × NFL × Time | ||||||||||||||||||

| CN × NFL × Time (ref) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| SCD × NFL × Time | −0.118 | 0.057 | .038 | −0.107 | 0.072 | .136 | 0.023 | 0.078 | .767 | 0.013 | 0.089 | .881 | −1.003 | 0.481 | .039 | 0.937 | 0.673 | .165 |

| MCI × NFL × Time | −0.101 | 0.040 | .012 | −0.075 | 0.049 | .133 | −0.054 | 0.055 | .320 | −0.057 | 0.061 | .356 | −0.825 | 0.346 | .019 | 0.867 | 0.500 | .084 |

APOE = apolipoprotein E; CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; p-tau = phosphorylated tau; Aβ = amyloid beta; ref = Reference group; CN = cognitively normal; Obj-SCD = objectively-defined subtle cognitive difficulties; MCI = mild cognitive impairment; NFL = neurofilament light; S.E. = standard error. Bold values are statistically significant (p<.05). Effect size (r-values) interpretation: small = 0.10, medium = 0.30, large = 0.50.

Continuous independent variables and covariates in the model were standardized to have a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1.

CN status was used as the reference group for the primary analyses; secondary analysis of the model was performed with MCI as the reference group.

Figure 2.

Trajectories of cognitive performance and IADL difficulties by baseline NFL and cognitive group

Model-predicted values of memory performance and Alzheimer’s preclinical composite score (mPACC) by cognitive group. Graphs illustrate predicted memory performance among those with (a) low baseline NFL and (b) high baseline NFL and Alzheimer’s preclinical composite score among those with (c) low baseline NFL and (d) high baseline NFL adjusted for age, education, sex, APOE ε4 allele frequency, and p-tau/Aβ positivity. Low and high NFL were determined by a median split of the values in the analytic sample. Shaded area represents 95% confidence intervals. NFL=neurofilament light; CN=cognitively normal; Obj-SCD=objectively-defined subtle cognitive difficulties; MCI=mild cognitive impairment.

4. DISCUSSION

Results extend prior work investigating biomarker associations with the Obj-SCD classification by examining associations with NFL. Findings are consistent with prior work showing elevated NFL levels in participants at risk for progression to AD, but who are not yet considered to have clinical dementia, [4, 16] and expands this work to a longitudinal study of Obj-SCD. Once significant cognitive impairment has been identified, irreversible neurodegenerative changes have commonly occurred [16]. Thus, biomarkers that predict cognitive decline during pre-MCI stages are important for early identification of individuals at risk as well as future drug development and may facilitate personalized therapies [16].

Our study is limited in generalizability beyond ADNI’s mostly white, highly educated sample. Strengths include adjustment for traditional AD risk factors such as APOE ε4 allele frequency and CSF p-tau/Aβ that relate to cognition. Given that effects of plasma NFL persisted after these adjustments suggests robust effects and that plasma NFL may be an independent risk factor rather than a byproduct of other risk factors. In addition, NFL has been shown to increase with age [17] and it is worth noting that our cognitive groups did not differ in mean age.

Disruption of mechanisms of neuroplasticity, resulting in a net loss of synapses over time, is thought to be an early event in the AD pathophysiological process and plays a central role in dementia [18]. In the present study, we examined neurocognitive processes related to neuroplasticity (episodic memory processing), which may be more closely related to AD pathology than are CSF or plasma biomarkers. In addition, findings add to an expanding literature showing associations between Obj-SCD criteria and sensitive biomarkers, and provide support for use of these criteria in clinical research to better capture subtle cognitive changes that occur early in the preclinical stage of AD.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEGEMENTS:

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Clinical Sciences Research and Development Service (Merit Award 1I01CX001842 to K.J.B. and Career Development Award-2 1IK2CX001865 to K.R.T. and 1IK2CX001415 to E.C.E.), NIA/NIH grants (R01 AG063782 to K.J.B.; R01 AG049810 and R01 AG054049 to M.W.B.; R03 AG070435 to K.R.T.; and P30 AG062429), and the Alzheimer’s Association (AARF-17-528918 to K.R.T., AARG-18-566254 to K.J.B., AARG-17-500358 to E.C.E.). Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Cogstate; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California.

Footnotes

Data used in preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at: http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf

DISCLOSURE/CONFLICT OF INTEREST:

Dr. Bondi receives royalties from Oxford University Press and serves as a consultant for Eisai, Novartis, and Roche Pharmaceutical. Other authors report no disclosures.

REFERENCES

- [1].Schultz SA, Strain JF, Adedokun A, Wang Q, Preische O, Kuhle J, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain levels are associated with white matter integrity in autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2020;142:104960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Blennow K A Review of Fluid Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s Disease: Moving from CSF to Blood. Neurol Ther. 2017;6:15–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Yuan A, Rao MV, Veeranna, Nixon RA. Neurofilaments at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:3257–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Osborn KE, Khan OA, Kresge HA, Bown CW, Liu D, Moore EE, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid and plasma neurofilament light relate to abnormal cognition. Alzheimer’s & dementia (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2019;11:700–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Thomas KR, Eppig J, Edmonds EC, Jacobs DM, Libon DJ, Au R, et al. Word-list intrusion errors predict progression to mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychology. 2018;32:235–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kaplan E A process approach to neuropsychological assessment. The Master lecture series Washington. D.C.: American Psychological Association; 1988. p. 127–67. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Thomas KR, Bangen KJ, Weigand AJ, Edmonds EC, Wong CG, Cooper S, et al. Objective subtle cognitive difficulties predict future amyloid accumulation and neurodegeneration. Neurology. 2020;94:e397–e406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Thomas KR, Edmonds EC, Eppig J, Salmon DP, Bondi MW. Using Neuropsychological Process Scores to Identify Subtle Cognitive Decline and Predict Progression to Mild Cognitive Impairment. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD. 2018;64:195–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Petersen RC, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Donohue MC, Gamst AC, Harvey DJ, et al. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI): clinical characterization. Neurology. 2010;74:201–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bondi MW, Edmonds EC, Jak AJ, Clark LR, Delano-Wood L, McDonald CR, et al. Neuropsychological criteria for mild cognitive impairment improves diagnostic precision, biomarker associations, and progression rates. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD. 2014;42:275–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Crane PK, Carle A, Gibbons LE, Insel P, Mackin RS, Gross A, et al. Development and assessment of a composite score for memory in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). Brain imaging and behavior. 2012;6:502–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gibbons LE, Carle AC, Mackin RS, Harvey D, Mukherjee S, Insel P, et al. A composite score for executive functioning, validated in Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) participants with baseline mild cognitive impairment. Brain imaging and behavior. 2012;6:517–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Donohue MC, Sperling RA, Salmon DP, Rentz DM, Raman R, Thomas RG, et al. The preclinical Alzheimer cognitive composite: measuring amyloid-related decline. JAMA neurology. 2014;71:961–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Teng E, Becker BW, Woo E, Knopman DS, Cummings JL, Lu PH. Utility of the functional activities questionnaire for distinguishing mild cognitive impairment from very mild Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2010;24:348–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Schindler SE, Gray JD, Gordon BA, Xiong C, Batrla-Utermann R, Quan M, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers measured by Elecsys assays compared to amyloid imaging. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2018;14:1460–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Osborn KE, Alverio JM, Dumitrescu L, Pechman KR, Gifford KA, Hohman TJ, et al. Adverse Vascular Risk Relates to Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarker Evidence of Axonal Injury in the Presence of Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD. 2019;71:281–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Khalil M, Pirpamer L, Hofer E, Voortman MM, Barro C, Leppert D, et al. Serum neurofilament light levels in normal aging and their association with morphologic brain changes. Nat Commun. 2020;11:812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ashford JW, Jarvik L. Alzheimer’s disease: does neuron plasticity predispose to axonal neurofibrillary degeneration? N Engl J Med. 1985;313:388–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Dr. Bondi receives royalties from Oxford University Press and serves as a consultant for Eisai, Novartis, and Roche Pharmaceutical. Other authors report no disclosures.