Abstract

Climate change is imposing a transformative process on agricultural and food systems, threatening the livelihoods of people dependent upon them which includes a large share of the world’s poor people. Transformative adaptation that addresses the risks and vulnerabilities to livelihoods that climate change imposes is essential for effective and inclusive transformation of food systems. Financing that is adequate, accessible and appropriate is essential to realizing these objectives. Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) are already playing an important role in financing transformative adaptation in the agri-food sector and are well-placed to address some of the existing shortcomings. Expanding public sector climate finance and incentivizing private sector investments is needed to attain adequate levels of financing. Reconsidering the rules and procedures for obtaining public sector finance and the capacity to utilize already existent administrative structures, as well as better targeting of activities and communities is important for accessibility. Appropriate finance requires use of mechanisms that address characteristics of the investment, including riskiness, delayed returns, high social values and new and unproven activities. Utilizing blended finance integrated with development finance can generate financing appropriate to the investment needs. Some positive shifts in these directions are already being undertaken by MDBs but more is required.

Keywords: Climate change adaptation; Agri-food system livelihoods; Climate finance; Food system transformation; Rural poor,; Resilience

Introduction

Food systems and the way they function determine not only the quantity and quality of the food supply and people’s diets, but also the quality, sustainability and resilience of the livelihoods of a large share of the world’s population. By livelihood we mean the capabilities, assets and activities required for a means of life that allows people to achieve a minimum level of wellbeing (Chambers & Conway, 1991). Climate change threatens these livelihoods and imposes the need for systematic and transformative adaptation which in turn calls for expanded and innovative financing.

Most of the world’s poor people depend on some aspect of agri-food systems for their livelihoods including from farming, fishing, forestry and herding, as well as the processing, storage, trading and distribution of food (IFAD, 2019a). Inclusive rural transformation is needed to improve these livelihoods, comprising a process of increasing agricultural productivity and marketable surpluses, while also expanding off-farm employment opportunities, better access to services and infrastructure, and capacity to influence policy (IFAD, 2016). This is an essential element for achieving inclusive food system transformation (Davis et al., 2021).At the same time, transformative adaptation entailing system level changes to reduce risks to agri-food system-based livelihoods and increase adaptative capacity is needed to confront the challenges climate change imposes on the sector (Fedele et al., 2019). These twin challenges demanding transformative change also require transformative levels and approaches to financing. As of today, such financing is not in place.

The aim of this paper is to identify shortcomings with the current system of financing for agricultural adaptation in the context of the kinds of investment needs climate change imposes on poor rural communities and small-scale agriculture and in the process of transforming agri-food system livelihoods. We focus on one of the key segments of the adaptation financing ecosystem—multi-lateral development banks (MDBs) describing their current roles and functions and identifying ways they may help address some of the shortcomings identified. Rethinking how we design, finance and implement actions and investments needed to improve livelihoods of the worlds’ rural people and ensure their resilience to climate change is fundamental to achieving transformative adaptation. This is an area where the MDBs have great experience as well as capacity, as they are supranational institutions tasked with financing investments to foster social and economic progress in low income countries, and more recently also active in managing climate finance for adaptation as well as mitigation. They include the World Bank, African Development Bank, the Asian Development Bank, the Asian Infrastructure Bank and the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). IFAD has been active in financing investments in rural transformation to eradicate poverty and hunger since 1977 and since 2012 has also been active in financing adaptation in the context of rural transformation and agricultural development.

There is considerable literature as well as consensus on the insufficiency of current financial resources to meet the investment needs for achieving transformative adaptation (GCA, 2020; GCA, 2019; Steiner et al., 2020) Overall funding for climate adaptation averaged US$ 30 billion a year in 2017–2018 and estimates are that it would need to increase ten-fold, to $US 300 billion a year to effectively address climate risks (GCA, 2021). This financing gap may increase even further due to fiscal drain on resources resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic. It is not just the lack of resources that is a problem, but also the lack of accessibility of available resources and the nature of financing mechanisms in use. (GCA, 2019; Murphy & Parry, 2020; Havemann et al., 2020). Most of financing for adaptation in the context of food system tranformation comes from international public sector finance. The MDBs are a primary channel, having committed almost US$ 15 billion in adaptation finance in 2019 (Joint Report on MDB Climate Finance, 2019).

The rest of the paper is organized into two main parts: the first part sets the stage for understanding the demand and supply of finance for adaptation in the agri-food system of developing countries. It consists of Sect. 2.1 which provides an overview of the impacts of climate change on agri-food livelihoods, Sect. 2.2 giving a description of approaches to transformative adaptation and Sect. 2.3 a brief overview of the governance of adaptation at global and national levels that affect the demand and supply of financing. The second part of the paper is presented in Sect. 3 which provides the analysis of the current situation for financing adaptation in the agri-food sector of low and middle income countries, together with an analysis of its adequacy, accessibility and appropriateness, together with ways that MDBs can contribute to improvements. Examples to illustrate concepts are provided using experience from the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). The paper concludes with Sect. 6.

The effects of climate change on agri-food based livelihoods

The effects of climate change are manifested in various forms such as increase in temperature (on average and on peak levels), increase in the number of hot days and hot nights, shifts in rainfall patterns, increased incidence and severity of extreme events and natural hazards. Any of these can have significant effects on current agri-food system livelihoods and their underlying assets and endowments, as well as the potential to improve them in the future.

High exposure to adverse weather events and low capacity to adapt to them results in damage or destruction of the already limited assets underlying livelihoods of the rural poor – including production, natural resources and human health. Recent studies indicate that climate change has already had a negative impact on crops yields at a global scale, and that adaptation to date has not been sufficient to offset these impacts – particularly at lower latitudes (Mbouw et al. 2019; Ray et al., 2019).

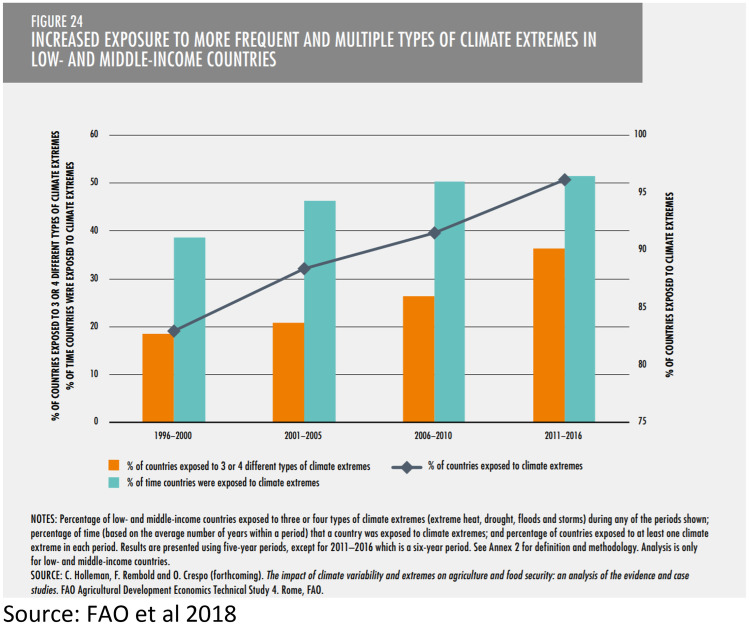

Increasing climate change impacts together with conflicts are key drivers of growing food insecurity, especially in Africa (FAO, 2018). The incidence of extreme climate related disasters (e.g. flood, drought, extreme temperatures, storms) has increased significantly over the period 1990 to 2016 and accounts for more than 80% of all internationally reported disasters (Fig. 1) (FAO, 2018). The same analysis indicates that 36% of the countries that experienced increases in the level of undernourishment since 2005 have also experienced extreme drought. In 2017, the average prevalence of undernourishment in countries with high exposure to climate risks was 3.2 percent higher than that of countries with low or no risk, and 351 million more people undernourished in the high exposure countries (FAO, 2018).

Fig. 1.

Increased exposure to more frequent and multiple types of climate extremes in low and middle-income countries.

Source: FAO et al. (2018)

There are several pathways through which climate change is affecting the different dimensions of food security, nutrition and livelihoods. For example, in Ethiopia, Auci et al. (2018) find that the poorest farmers suffer the greatest decreases in crop-based income due to changes in water availability, since they had the lowest level of income diversification. Asfaw & Maggio (2018) found that in Malawi, significant increases in seasonal temperatures over the historical average had a detrimental effect on overall consumption (-17.9%), food consumption (-29.8%) and caloric intake (-22.2%). These negative effects were even greater for households headed by women. Interviews in rural communities in the Peruvian Amazon (including indigenous communities) revealed that damage to crops and livestock from fires associated with changes in temperature and rainfall patterns was the top risk to livelihoods (Chavez Michaelson et al., 2020). Recent research by Alfani et al. (2019) in rural Zambia shows that households affected by the drought experienced a decrease in maize yield by around 20 percent, as well as a reduction in income up to 37 percent. Among adaptation practices adopted, those that led to better resilience included livestock diversification, income diversification, and the adoption of mechanical erosion control measures which increased water retention. Mechanical erosion control measures, which include soil and water conservation techniques, have been shown to have similar shock buffering impacts in rural Tanzania (Arslan et al., 2017).

Adaptation efforts to date are generally not sufficient to offset the negative impacts of climate change on agri-food system livelihoods in developing countries (GCA, 2019). In an analysis of the adequacy of current adaptation efforts amongst small scale farmers in developing countries, Thornton et al. (2018) surveyed 6300 households across 21 countries and 45 sites. Their results indicate that across a wide range of locations and conditions, most agricultural households’ adaptation actions are not sufficient to allow for an improvement in their livelihoods or their ability to increase production to meet growing food demands. Successful cases of adequate adaptation were found to be dependent on high levels of collective action, organizational development and community awareness, e.g. the enabling environment (Thornton et al., 2018).

Priority action areas for climate adaptation in the agri-food systems of developing countries outlined by the Global Commission for Adaptation in 2019 include major expansion of early warning systems, enhancing the resilience of key infrastructure, improving dryland agriculture towards more productive and sustainable systems, protecting mangroves and making water resource management more resilient (GCA, 2019). Steiner et al. (2020) identify key priorities for transforming food systems under a changing climate and they too include improvements in resilience, sustainability and productivity of rural livelihoods including small-scale agriculture in developing countries as a key priority. De-risking food value chains through early warning systems, adaptive safety nets and climate advisory systems is another priority as is realigning policies and financing to build sustainable food systems that enhance equity while also attracting a major expansion in private sector investments (Steiner et al., 2020).

Transformative adaptation in the context of agricultural development and food system transformation

The primary means of dealing with the threat climate change poses to rural livelihoods is through the process of adaptation which the IPCC defines as:

‘The process of adjustment to actual or expected climate and its effects. In human systems, adaptation seeks to moderate or avoid harm or exploit beneficial opportunities’

A primary component of adaptation is to increase resilience which IPCC (2012) has defined as.

‘The ability of a system and its component parts to anticipate, absorb, accommodate, or recover from the effects of a hazardous event in a timely and efficient manner, including through ensuring the preservation, restoration, or improvement of its essential structure and functions’

Adaptation can thus be considered as a necessary feature of activities aimed at improving the livelihoods of the rural poor, which entails enhancing resilience of those livelihoods as a fundamental component. The role of adaptation then is to support the transformative processes needed to move from a poorly performing system and inequitable system to one that generates higher and more stable welfare for poor people, better nutrition for both rich and poor, and better environmental outcomes (Few et al., 2017). For example, a livelihood diversification project that reduces women’s vulnerability to climate change could be termed a transformative adaptation activity if it also triggers a sustained shift in gender relations, gender agency and empowerment of women” (Few et al., 2017). In a review of 80 studies, Fedele et al. (2019) find that “transformative adaptation is characterized as being restructuring, path-shifting, innovative, multiscale, systemwide, and persistent”. They conclude that if policy makers and practitioners supported and implemented transformative adaptation to address real or potential changes triggered by climate change, they would efficiently and sustainably develop and be able to anticipate or recover from climate change impact.

Transformative adaptation integrates responses to climate risks as part of the dynamic transformation of agricultural and rural livelihoods needed to achieve better livelihoods. In practice, this means adaptation actions should take account of specific vulnerabilities to not only climate change but also those most vulnerable and left behind in agricultural and rural development processes – such as women, youth and indigenous groups. Transformative adaptation requires system level changes to reduce risks to agricultural-based livelihoods and increase adaptative capacity (Fedele et al., 2019).

The analysis of the potential effects of climate change on rural livelihoods as well as adaptation approaches gives some indication of priority areas where transformative adaptation can contribute to the dynamic of agricultural and rural development. Integrating the need to protect and enhance ecosystem services from climate risks, enhancing resilience of rural livelihoods by building the diversity in farming systems and food production. Another is building effective means of coordinating actions and building community cohesiveness. Reducing exposure to risks, for example by ensuring the resilience of rural infrastructure to climate shocks in order to support stable growth in agricultural value chains and employment opportunities is another example, as is expanding the capacity to cope with adverse events.

Vermeulen et al. (2018) distinguish between transformative and transformational adaptation with the former referring to process and the latter to the outcome. They define transformational adaptation in agriculture by three criteria: the response to climate risks, a redistribution of at least a third of the primary factors of production and consumption and within a timeframe of 25 tears. In the examples of transformational adaptation already occurring documented in the paper, the capacity for effective collective action at local levels is a key factor amongst most cases. Investing in knowledge and information services at local levels to support effective local level action, together with financing for investments that have long term and delayed returns are two of the recommendations from this analysis (Vermeulen et al., 2018). Financing plays an important role in their proposed actions to support transformative adaptation, particularly to compensate for changes that cause short term losses, particularly to small-scale farmers and food system participants (Vermeulen et al., 2018).

The effectiveness of financing and its capacity to be transformative is very much driven by the governance of adaptation at global and national levels. This is the focus of the following section.

Governance of adaptation and the demand and supply adaptation financing in developing country agri-food systems

The need for good governance is a theme running throughout the literature on transformative adaptation, since transformation requires a major shift in how decisions are taken and changing the political and social roots of vulnerability. Few et al. (2017) identify reorganization and reorientation as two fundamental mechanisms of change in how decisions and actions on adaptation are taken. Reorganization refers explicitly to a major change in governance structures while reorientation refers to a reconfiguration of social values and social relations in adaptation (Few et al., 2017). One of the main features of effective adaptation is the ability to coordinate actions at relevant levels which requires effective governance (Jensen et al., 2020). While some recent developments in global and national climate policies are leading to improvements in adaptation governance, there are still considerable shortcomings.

Adaptation policy affecting the demand and supply of financing has been largely developed at the international level under the aegis of the UNFCCC. While mitigation captured much of the attention and policy development in the early years of the UNFCCC, more recently as the effects of climate change become increasingly apparent, much greater attention and financing has been given to adaptation. At the Paris climate conference (COP21) in December 2015, 195 countries adopted a global climate agreement due to enter into force in 2020 known as the Paris Agreement. In this agreement adaptation and its financing were given equal weight with mitigation and parties to the Paris Agreement committed to ‘making finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development’ (Article 2.1c)(Whitley et al., 2018).

Under the Paris agreement, (para 53), developed countries expressed their intention to continue their existing collective goal to mobilize US$100 billion per year in climate finance until 2025, at which point they would set a new target post-2025 using US$100 billion as a floor. The Green Climate Fund (GCF) was confirmed in its function as an operating entity of the Financial Mechanism of the UNFCCC with the ambition to channel a significant portion of future climate finance from both the public and private sector (Climate Focus, 2016). The Paris Agreement acknowledged that developed countries must continue to take the lead in mobilizing climate finance. It mandated them to report biennially on their financial support provided and mobilized through public interventions for developing countries.

Transparency in accounting for climate actions and finance is a major objective of the Paris Agreement. This means that the way in which developed countries’ public finance flows are accounted and reported, and whether a collective goal can be significantly raised in 2025, will be a crucial yardstick for the success of the Paris climate deal.

One of the key motivations for transparency in accounting, as well as one of the most contentious issues in the UNFCCC negotiations arises around the principle of additionality. This requires that financing for adaptation should come from new and additional resources, and not just relabeled Official Development Assistance (ODA) (Brown et al., 2010). There is a climate justice element in this argument – that poor countries who have had the least contribution to causing the climate change problem bear the greatest costs in adapting to it, and this should be paid for those who created the problem – e.g. polluter pays principle. For these reasons, there has been considerable attention given to distinguishing adaptation financing from development finance. However even with these measures, the degree to which climate justice is actually being realized in the current governance of adaptation finance has been questioned, noting a certain sidelining of the polluter pays principle, and a strong focus on transparency in the absence of robust systems of accountability (Khan et al., 2020).

The concept of additionality is also relevant in the context of effectiveness of public sector funding. Here the idea is that the public sector should not be directing funds where the private sector is already investing. Rather, limited public investments should be directed towards transformative technologies and markets – and to attract new and additional private sector financing (Escalante et al., 2018). In the process of planning, financing and implementing adaptation actions in the context of agricultural and rural development, two key concepts differentiate climate finance from traditional ODA; new and additional resources calls for funding to be clearly oriented towards quantifiable and measurable climate targets that can be distinguished from traditional development resources, and agreed full incremental costs requires a technical analysis that directly attributes the partial or full cost of an intervention to climate change drivers (Brown et al., 2010).

The Nationally Determined Contribution (NDCs) are a new national climate change policy instrument created under the Paris agreement (Article 4, paragraph 2) which requires each Party to prepare, communicate and maintain successive nationally determined contributions (NDCs) that it intends to achieve. To date, 75% of countries’ Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) have adaptation targets, including 100% of African countries and 92% of Asian countries. Water, agriculture, and health are the sectors most frequently identified as “key priority sectors” and “vulnerable” in the NDCs (see FAO, 2016b). The Koronivia Joint Work Programme on Agriculture established under UNFCCC in 2017 is also generating calls for adaptation actions which will likely be reflected in increased emphasis on agriculture and land-use change in the revision of countries’ Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) expected for 2022 (Chiriacò et al., 2021).

Recently, national policy-makers have become increasingly concerned with the need for adaptation. ers. According to a recent analysis of national legislation on climate change adaptation, in the 2012–2013 period, 85 countries passed a total of 133 adaptation laws and policies – constituting the most intense period of national legislation in this area (Nachmany et al., 2019).

Adaptation policy and financing have largely developed in parallel to agricultural and economic development efforts, rather than as integrated components. For adaptation, the discourse on the need and means of financing adaptation emerged from the UNFCCC policy process. The science and concepts of adaptation have been developed under the aegis of the IPCC. There has been an evolution of agencies and channels handling the financing of adaptation over time, with a prominent role for multilateral institutions. The Adaptation Fund, Special Climate Change Fund and the Least Developed Country Funds were established in 2001 as trust funds managed by the Global Environmental Facility, the Climate Investment Fund was established in 2008 with two trust funds that channel resources through MDBs (FAO, 2016a).

At the national level, adaptation policies and financing are frequently managed by environmental ministries, whereas development policies and financing are handled by finance or dedicated development ministries. With regard to rural development many policies concerning adaptation are also under the aegis of Ministries of Agriculture, therefore further complicating the coordination ideally required to ensure that adaptation policies in one sector are not counterbalanced by policies in other sectors and are financially and institutionally supported (FAO, 2016a).

MDBs and Climate finance for transformative adaptation under food system transformation

Climate finance for agricultural adaptation in the context of improving agri-food based livelihoods in food system transformation may come from private or public sources at national and international levels and which could be bi-lateral or multi-lateral. Here we are adopting the definition of climate finance from the Climate Policy Initiative which is “capital flows directed towards low-carbon and climate-resilient development interventions with direct or indirect greenhouse gas mitigation or adaptation benefits.” (CPI, 2017).

The MDBs are a key conduit for climate finance to low and middle income countries and to agri-food system activities. In 2019, the MDBs reported a total of US$ 14,937 million in commitments for climate change adaptation finance, with US$ 13,936 million, or 93 per cent, committed to low-income and middle-income economies. Approximately 7 percent of this total was committed to the crop and food production sector, while another 9 to 10 percent on other agricultural and ecological resources (Joint Report MDBs, 2019).

MDBs provide finance for adaptation to developing countries through two different channels. The first is through co-financing arrangements with dedicated climate finance institutions such as Green Climate Fund and the Adaptation Fund. The second channel is through climate-related development finance. These are funds that promote economic and social development with climate change co-benefits (Murphy & Parry, 2020). In 2019 about 94 percent of the MDB financing for adaptation to low and middle income countries was climate-related development finance, with only 6 percent from MDB managed external resources (Joint report MDBs, 2019).

Another financing modality of the MDBs is through blended finance. Blended finance is defined as the use of development capital to mobilize additional private finance for SDG related goals (Blended Finance website accessed June 22, 2021). Blended finance is a structuring approach that allows investors with different objectives to invest together while achieving their own aims be it financial returns, social impact or both (Convergence Blended Capital website accessed June 22, 2021). The approach addresses one of the key barriers to private sector investments – high perceived and real risk. Examples of blended capital structures include concessional loans coupled with commercial debt or equity, grant funding for project design or technical assistance coupled with equity/debt (Convergence Blended Capital Website, 2021a, b). The Convergence database has recorded 146 blended finance transactions targeting the agriculture sector and/or SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), representing aggregate committed financing of USD 13.4 billion (Convergence Blended Capital, 2021a, b). The main archetype of these blended finance transactions was concessional debt/equity and technical assistance funds with a major focus on agricultural inputs and agri-finance (Convergence Blended Capital, 2021a, b).

Havemann et al. (2020) proposes four different but related archetypes of blended finance with concessional capital. ‘Permanent blended finance’—financial structures that will always need to rely on concessionary finance within the capital mix for example in cases where research has been done to indicate this requirement, ‘Transitional blended finance’—concessionary capital element can taper down as the investment moves past proof of concept, e.g. where a government agency may offer a partial guarantee for an agricultural investment fund to help mobilize private capital, such government-backed guarantees typically only cover a certain quantity of transactions; ‘Adjustable blended finance’—inclusion of concessionary capital varies based on relevant risk or impact creation, ‘Impact monitoring and verification blended finance’—concessionary capital covers the cost of monitoring or verifying impact (Havemann et al., 2020).

MDBs are already committed to scaling up climate financing and work towards better alignment with development finance. Twelve MDBs, including IFAD, have pledged to scale up financing for adaptation and are working toward doing so, in line with their 2015 commitment to the five Voluntary Principles for Mainstreaming Climate Action in Financial Institutions (Murphy & Parry, 2020). Part of this commitment involves shifting away from incremental approaches to financing climate actions, to “making climate change—both in terms of opportunities and risk—a core consideration and a ‘lens’ through which institutions deploy capital” (Climate Action in Financial Institutions, 2018 cited in Murphy & Parry, 2020 page iv). These commitments are important in the context of ensuring the adequacy, accessibility and appropriateness of financing for transformative adaptation as discussing in the following sections.

Adequacy of climate finance for small-scale agriculture

Estimates of the level of financing required for transformative adaptation in the context of food system transformation are difficult to make, but clearly of a significant magnitude in the next 25 years. FAO estimated that an additional $265 billion per year would be needed to generate the level of agricultural growth and rural development needed to eradicate poverty and hunger by 2030 (FAO, 2017). This is in addition to estimated annual investment needs of 105 billion/year for adaptation, 480 billion for investments related to mitigation of climate change related to increasing energy end-use efficiency and 600 billion annually for investments in low GHG emissions energy supply. The total estimate of investment needs is 1,452 billion per year (FAO, 2017). The Ceres 2030 project estimated that ODA should increase by US 14 billion/year from a current level of 12 billion/year and public sector investments on the part of low and middle countries by 19 billion/year to eradicate hunger and double agricultural productivity amongst smallholder producers by 2030 (Ceres 2030, 2020). The additional public sector spending is expected to generate an additional 52 billion/year of private sector resources (Laborde et al., 2020).

Current levels of financing for adaptation or agricultural and rural development are nowhere near these levels of estimated need. This is evidenced in the Ceres 2030 work calling for more than doubling the donor financing to food and agricultural sector development as well as a major increase in financing from both the domestic public sector and a huge increase in private sector spending. As for adaptation specifically, the cumulative climate finance tracked for agriculture, forestry, and land use was only USD 20 billion per year in 2017/2018, representing 3% of the total tracked global climate finance for the period (CPI, 2019). Tracking the amount that have actually been committed to climate finance is complicated, since definitions and boundaries are not clearly identified or agreed upon. In particular, differentiating between climate finance and ODA has proven controversial, over the inclusion of development resources redirected to climate finance and relabeling of ODA as climate finance, raising doubts as to its additionality (Yeo, 2019).

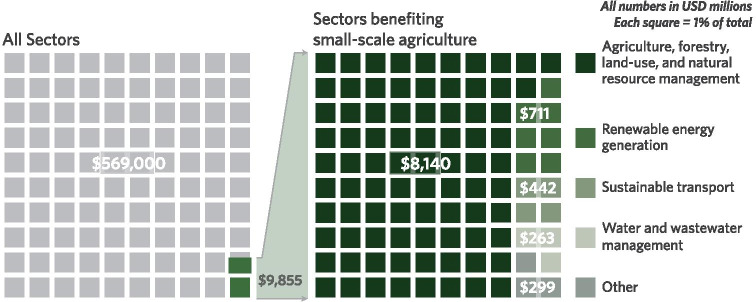

In 2020 for the first time a detailed analysis of the flows of climate finance to the small-scale agricultural sector was conducted (Chiriac et al., 2020). The analysis focusses primarily on financing from the international public sector since data from the domestic public sector and private sector is generally not available. The analysis indicated that tracked climate finance flows to small-scale agriculture in developing countries amounted to an annual average of USD 10 billion in 2017/2018. This represents approximately 1.7% of total climate finance tracked in the same period. Figure 2 illustrates just how minuscule the share of climate finance flowing to small-scale agriculture within overall climate financing (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Share of annual climate finance in small-scale agriculture relative to other climate finance.

Source: Chiriac et al. (2020)

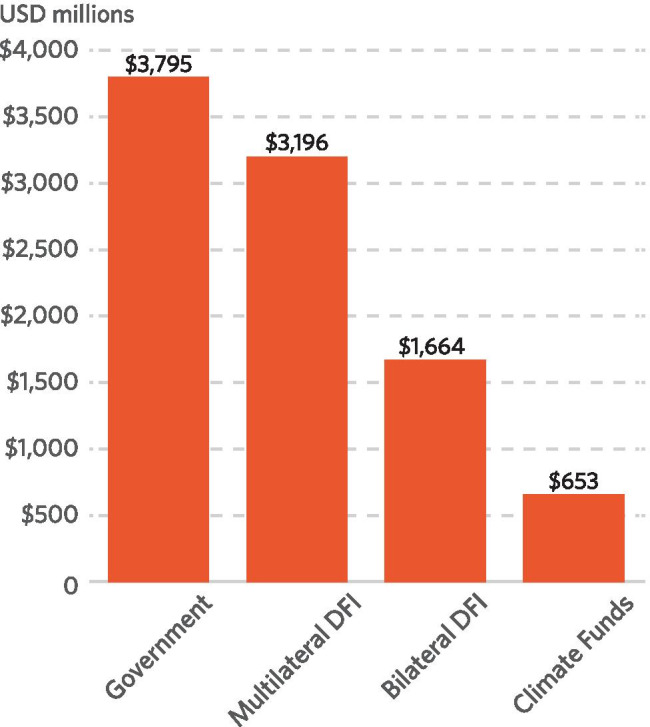

Fig. 3.

Annual commitments of public international climate finance to developing countries.

Source: Chiriac et al. (2020)

Tracked climate finance to smallholder agriculture was primarily through bi-lateral government sources (39%) multilateral DFIs (32%), bi-lateral DFIs (16%) and climate funds (13%) (Chiriac et al., 2020). 95% of the financing was from international sources. IFAD is an MDB that established a separate fund specifically aimed at adaptation actions to accompany their lending activities. Under the adaptation for Smallholder Agriculture Programme (ASAP) climate finance is channelled to small-scale producers, though not at the scale that is or will be needed by 2030. In 2019 IFAD committed about US$568 million in climate finance across 38 approved projects. Of this total, US$507 million has been identified as adaptation finance and about US$61 million as mitigation finance (IFAD, 2021).

At present the financing for agricultural adaptation in the context of agricultural development and food system transformation is clearly inadequate to the investment needs. It is also inadequate to support the needed increase in private sector investments as per blended finance arrangements. Millan et al. (2019) make the case for public sector investments to address core market failures to create new sustainable investment opportunities that will stimulate private investment flows. This involves investments in data and information, risk management mechanisms and regulatory approaches that embed environmental values into market transactions (Millan et al., 2019).

One example of blended finance used by IFAD to expand private sector resources comes from the Adaptation to Climate Change in Mekong Delta in Ben Tre and Tra Vinh Provinces (AMD) Project. In this project IFAD co-invested with a private sector organic coconut processing company to develop a coconut value chain through a Public–Private-Producer (4P) partnership (Murphy & Parry, 2020). Coconut is being promoted as an alternative to rice since increasing salinity of irrigation water is making rice production infeasible. The private sector processor guaranteed they would purchase 100% of the organic coconut produced by participating farmers and also provided technical assistance in the production. Impact assessment of the project indicates the project did increase climate resilience of beneficiary households, especially with respect to saline intrusion, although there were cases where farmers preferred to retain their own marketing outlets rather than the project’s. Beneficiary households exposed to saline intrusion were able to shield losses to average value per capita, were less likely to realize very low crop value per capita, and were able to access more income sources, loans and transfers (Afonina et al., 2021).

Another example of the problems that can arise for MDBs in seeking to expand investment resources come from the IFAD experience with an IFAD project co-financed by the Green Climate Fund on Inclusive Green Financing for climate resilient and low-emission smallholder agriculture in Niger. The main aim of the project is to improve access to financing for activities that promote climate resilient agriculture for farmers organisations, women and youth associations, cooperatives; Micro-, Small- and Medium-sized, Enterprises, Micro Finance Institutions and commercial banks. The financing structure of the project included GCF financing of 8.5 million euros to the Government of Niger for on-lending by the Agricultural Bank of Niger, as well as a grant for technical assistance, IFAD grant co-financing of 2.12 million euros to be provided in sub-grants, and 850,000 euros co-financing by the Agricultural Bank of Niger to be used for sub-loans together with the GCF resources. IFAD had hoped to submit this proposal through the simplified approval process of the GCF (see https://www.greenclimate.fund/projects/sap) which IFAD is eligible for as an accredited UN entity. However, the inclusion of the Agricultural Bank of Niger in the funding structure created complications since it is not an accredited agency with the GCF. It is also a private and not public bank, which created complications for IFAD which at the time did not have the necessary institutional arrangements to work with private sector entities. This example illustrates how expanding the adaptation resources via co-financing faces serious bureaucratic hurdles. IFAD internal communication.

Accessibility of climate finance

The accessibility of climate finance is driven by the nature of the transactions in channeling finance from the source to the beneficiary. In most cases there are two levels of beneficiaries: the first is the borrowing entity which is usually a national government, financial institution or NGO. The second set of beneficiaries are the final users of the finance and include farmers, rural communities, producer organizations and value chain actors (Chiriac et al., 2020).

Direct transfers of climate finance from governments of developed countries to governments of developing countries are often perceived as risky due to information asymmetries, the infeasibility of perfect contract enforcement at the international level, and uncertain recipient capacities and respective outcomes (Brunner & Enting, 2014). Access to climate dedicated funds requires capacity to provide detailed analysis of the problems and solutions the investment is aimed at, essentially generating significant transactions costs in obtaining financing. Such capacity is difficult to attain for low income – and even some medium income countries. Addressing this shortcoming is where MDBs have certain advantages.

The experience of the IFAD Adaptation for smallholder agricultural programme (ASAP) program gives some insights on the potential for reducing transactions costs. The ASAP program consisted of a separate and dedicated fund to provide grants for adaptation actions that accompanied IFAD project loans. Since ASAP was implemented jointly with IFAD lending activities, there was a rigorous process of ensuring safeguards were in place and fiduciary standards met at the country level as part of the loan process which ASAP then piggy-backed upon. The application for the grant itself was then relatively simple. While this approach reduced transactions costs for accessing climate finance, it also picked up the problems inherent in the development lending process. This includes delays in approvals and disbursements as well as constraints in the beneficiary selection. IFAD lends only to national governments and is thus unable to channel funds to other entities that could be effective actors in the adaptation sector.

Donor governments have sought to minimize climate financing risks by delegating the provision of climate finance to bilateral and multilateral organizations that implement and monitor projects in recipient countries. MDBs have established capacity for the analytical and fiduciary preparations necessary to reduce risks and increase potential effectiveness of investments in adaptation (Murphy & Parry, 2020). However using this channel can also generate barriers in the form of administrative requirements of the MDBs. (Brunner & Enting, 2014). One of the most important of these barriers is the restricted set of first beneficiaries that MDBs can channel funds to. This is often restricted to national governments, eliminating the possibility of channelling funds through NGOs or even national development banks. This limitation can also create problems in developing blended finance with the private sector as highlighted in the example in the previous section.

Another major issue in the accessibility of adaptation finance to first recipients arises from transactions costs associated with the need to track climate finance to determine additionality as well as the degree to which donor commitments are being met which creates a significant accounting burden. As a result of this mandate, donors, institutions, and funds established to provide climate finance to developing countries have developed tools and methodologies to ensure that the required attribution to climate change is well justified, traceable and calculated. While this serves the purpose of justifying a climate finance intervention and recording climate related financial flows, it poses significant challenges to the mainstreaming of addressing climate related risks in a project intervention. The additional analysis associated with climate finance result in high transaction costs, given that detailed technical assessments are necessary to justify the suitability of the funding for a given intervention and to validate the amount assessed. Such assessments include amongst others, sophisticated modelling, documentation of historical trends, and development of counterfactual baseline/alternative scenarios. This often makes climate finance inaccessible, both technically and financially, to public and private stakeholders that are not specialized in such analysis (Murphy & Parry, 2020).

Here too, the MDBs have a key role in reducing such transactions costs. The MDBs have developed the Common Principles for Climate Finance Tracking. Murphy and Parry (2020) note that while MDBs have made significant progress on tracking finance for adaptation, but many developing country partners do not have comparable systems in place to track domestic and international financial flows for adaptation, including MDB finance flows.

Moving to consider accessibility of adaptation finance to secondary recipients takes us to the issue of targeting. Until now, much of the adaptation financing in agriculture has been focused solely on food production, with limited focus on the full range of food system vulnerability and implications for livelihoods and food security (Conevska et al., 2019). According to Chiriac et al. (2020), fance benefitting individual small-scale producers (16%) and cooperatives, or farmer associations (15%) combined, constitute another large share of overall adaptation finance aimed at agricultural and rural development. It indicates the strong focus of climate finance on agricultural production at farm level.

Adaptation projects that foster collective action and community cohesiveness are an important means of increasing accessibility of adaptation finance to a wider community. The experience of the PAPAM/ASAP program in Mali illustrates this. The project was funded by IFAD through a loan of US$40 million and an Adaptation for Smallholder Agriculture Programme grant of US$9.9 million. The ASAP grant funded a participatory mapping exercise which resulted in the development of 30 municipal adaptation plans (PCA) identifying priority adaptation actions based on analysis of vulnerabilities and ecosystem conditions. The municipalities were given direct responsibilities and financial support for the implementation of the plans (IFAD, 2019b).

Chiriac et al. (2020) found that only 7% of the financing for adaptation in small-scale agriculture targeted value chain actors, including agri-enterprises and SMEs. Even less (3%) was directed towards formal financial institutions (Chiriac et al., 2020). However, many of the barriers to adaptation in the small-scale agricultural sector are commercial in nature – e.g. lack of agri-business development, low and risky financial returns discouraging engagement of private sector lending and investment risks due to lack of information. This suggests that people operating agri-enterprises and SMEs face severely constrained access to climate finance. (Chiriac et al., 2020).

The DECOFOS community-based forestry project in the Campeche, Chiapas and Oaxaca states of Mexico is an example of how a co-financing approach was used to channel to small scale timber and eco-tourism enterprises. The was financed from several sources: the Government of Mexico, IFAD, the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and project beneficiaries for a total cost of US$18.5 million. One of the project components aimed to improve the organizational, planning and managerial capacities of local communities/ejidos through the delivery of training courses and workshops, while the second component supported the start-up of micro entrepreneurial projects and small businesses related to sustainable production of timber and non-timber forest products and eco-tourism, and promoted the adoption of agroforestry and good environmental practices for climate change mitigation and adaptation (IFAD, 2019b).

Appropriateness of climate finance

In this section we consider three dimensions of appropriateness of climate finance for transformative adaptation in agriculture under food system transformation. The first is the degree to which the financing enhances the quality of investment planning and fosters strategies that align with the Paris Agreement objectives. The second is the degree to which the financing instrument used is adapted to the financial flows of the investment and the third is the degree to which the financing approach allows for flexibility which is key in the agricultural adaptation context.

The poor quality of national adaptation strategies and plans, the existence of a multiplicity of such plans and disconnects between the NDC and National Adaptation Planning (NAP) from broader national economic development planning are some of the challenges that Murphy and Parry (2020) identify in aligning developing country adaptation priorities and financing with the Paris Agreement objectives and MDB financing. MDBs can and have played a key role in improving the quality of the plans and aligning them with national economic development goals as well as objectives and financing of the Paris Agreement through technical assistance to NDC planning as well as adaptation policy-making (Murphy & Parry, 2020). The example of IFAD’s involvement in the Kyrgyzstan NDC development illustrates how this may work. At the request of the Kyrgyz government, IFAD provided technical assistance in revising the country’s NDC via grant funding from ASAP. One of the main inputs to the revised NDC from the IFAD technical assistance was the addition of the livestock sector which was absent from the initial NDC, despite its importance in the national economy as well as a source of livelihood for a large share of the population – many of whom are poor (IFAD, 2021). The assistance included an analysis livestock emission and strategies for low-carbon livestock development, as well adaptation measures for sustainable livestock and pasture management. It also included detailed mapping of pastures and support for the strengthening and expansion of community based livestock and pasture management groups and plans. The assistance also included support to the development of a proposal to the Adaptation Fund for financing (IFAD, 2021).

The second issue of appropriateness concerns the selection of the right financing instrument for the intended investment. Financing instruments should be selected to suit the nature of the adaptation investment and its financial and social returns over the short and long run. In practice, poor people dependent on agri-food system livelihoods are vulnerable as a result of numerous factors, including inadequate agricultural practices, a deteriorating natural resource base, market demand for specific crops and animals, and limited access to land, secure water sources which are exacerbated by climate change. It is reasonable to accept that an integrated operation to address such vulnerabilities cannot be entirely attributed to climate change adaptation, and therefore should not be financed fully or solely by climate finance sources. The type of financial instrument to be applied should not only be defined by the type of intervention but also by the target beneficiaries and the project context. A climate change oriented rural development intervention targeting organized, medium scale producers in an upper middle income country (UMIC) will have completely different requirements to those of small scale individual subsistence farmers in a low income country (LIC). A climate justice-based argument points towards the allocation of grant climate financing to strengthen adaptive capacity and increase resilience. The principle that smallholder farmers, as bearers of a disproportionate impact of climate change, should have access to highly concessional financing applies, and the inclusion of other instruments should only be considered when appropriate in the given context.

Nevertheless, activities directed to address climate vulnerabilities can have significant economic and social co-benefits such as reduced health costs from making a diversified healthy diets accessible to low-income families which may justify the allocation of other financial instruments in a given intervention. For example, an intervention may implement sustainable, diversified food production systems with climate resilient crop varieties, and “climate proof” infrastructure across a value chain. In such a context, a combination of grant, concessional loan, and equity resources may be justifiable to provide adequate incentives to achieve a desired result. For example, the Planting Climate Resilience Project in Brazil is a blended finance project that includes a loan of $US 65 million and a grant of $34.5 million from the Green Climate Fund, $30 million from IFAD and $73 million from Brazil’s National Social and Economic Development Bank (BNDES). Technical assistance and higher risk initial investment in climate resilient production systems are financed with a blend of grant and concessional loans from GCF, while well proven investments in water harvesting/management and agroprocessing are financed through IFAD and BNDES loans.

The appropriateness of the financing instrument is not solely driven by the nature of the financial returns from investments. Risk and incentives to try new and untested approaches are important as well. Millan et al. (2019) focusses specifically on the issue of financing adaptation in the context of food system transformation and identified high investment risk and lack of primary data/information asymmetries and unproven and early-stage business models with long development lead times as a leading cause of core market failures incentivize private sector investment into adaptation. Experience from the IFAD ASAP program indicates that grant financing provided a key incentive for adoption of the program activities overcoming reluctances linked to the unknown and untested effectiveness of the adaptation actions and their potential effects on development outcomes. The importance of grant financing to test new approaches is borne out by the experience of some countries which had ASAP grants subsequently using loan funding to scale adaptation activities including Bolivia, Mali, Mozambique, Niger, Gambia and Cambodia. These governments have recognized the benefit of certain adaptation activities through a trial and error process and now, despite not being grant-supported, are willing to borrow money in order to achieve similar results (IFAD, 2019).

The table below builds on Haveman’s 2020 and Millan’s 2019 analyses, laying out a set of adaptation activities which are likely arise in transformative adaptation efforts, together with an indications of an appropriate financing instrument based on the nature of the investment, the amount and timing of financial returns and the degree of uncertainty/inexperience with the activity.

| Activity | Appropriate financing instrument |

|---|---|

| Technical assistance to identify climate risks and potential responses | Grant |

| Capacity building across stakeholders to assess climate change risks and develop a response | Grant |

| Adaptation investment with uncertain or highly delayed financial returns | Grant |

| Agricultural investment project generating positive financial returns |

Concessional loan and/or revolving fund |

| Climate risk reduction (index passed insurance, etc.) | Guarantees, first loss tranches |

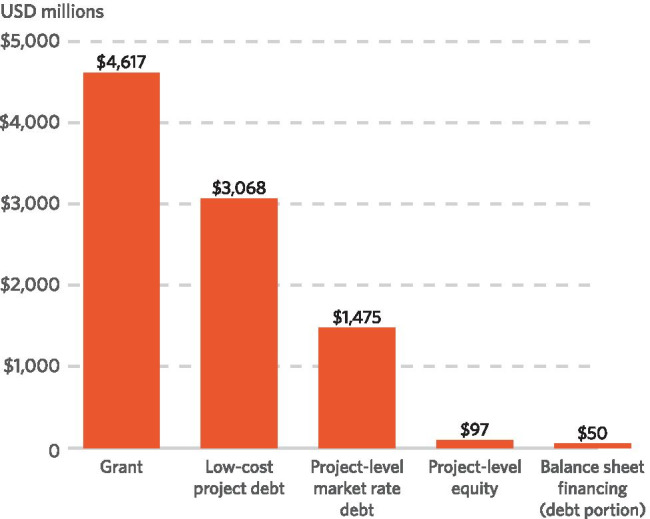

As can be seen in Fig. 4 from Chiriac et al. (2020), grant finance dominates all the instruments for climate financing to small scale agriculture. Concessional lending is also a widely used instrument and even lending at market rates is being used in a significant share of climate financing to small-scale agriculture, albeit frequently with grant co-financing, or in blended financing structures (Havemann et al., 2020; Convergence Capital, 2021b).

Fig. 4.

Annual commitments of international public finance to developing countries by instruments.

Source: Chiriac (2020)

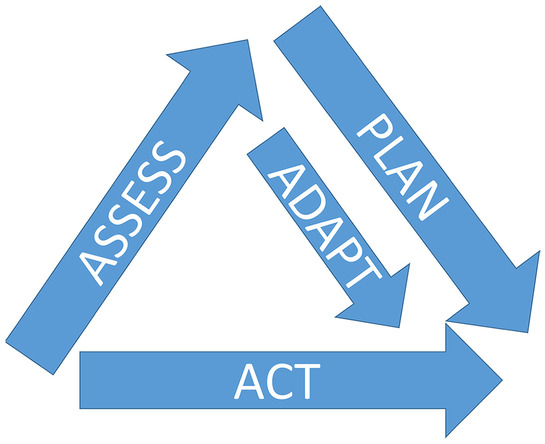

Flexibility to allow for adaptive learning is another important dimension of appropriate financing that is fundamental in the context of adaptation. An adaptive management approach involves real-time monitoring and evaluation, learning among stakeholders, innovating and re-strategizing whenever necessary. A particular feature of climate risks is that the situation is increasingly dynamic as temperatures are rising and impacts accelerating. The adaptation needs of small-scale producers are constantly evolving which is why the focus on general resilience building to shocks and variations is key. Adaptive management is important for managing uncertainty on the basis of best-available information, and to avoid maladaptation (Fig. 5). This requires a financing structure that allows for some flexibility to adapt based on monitoring and assessment.

Fig. 5.

The process of adaptive management

Flexibility can be built into the financing plan as was the case in the IFAD PROCAVA project in Mozambique. The project includes a “component 0” aimed at disaster Risk Reduction and Management which enhances the flexibility of the financing. Component 0 allows PROCAVA to promptly react to weather extremes, facilitating the quick adoption of remedial actions construction of dykes, dams, or canals to manage flood water; and climate proofing infrastructure such as rural roads adaptation investments for natural disaster recovery. Component 0 is therefore a smart adaptive mechanism that will facilitate and allow faster processing (IFAD, 2019).

How improving adaptation financing relates to action proposals of the Food System Summit (FSS)

The opportunities that improved management of climate finance offers coincide with the types of proposals emerging from the discussion starter papers for the five action tracks of the 2021 UN Food System Summit. Action Track 1 on ensuring access to safe and nutritious food for all calls for an expansion funding to extra $33 billion/year to sustainably end hunger, as well as targeting more impact investments to small and medium agro-food enterprises. Action Track 2 and 3 on shifting to sustainable consumption patterns calls for the implementation of government-driven mechanisms to achieve true cost accounting to include environmental and nutritional values in food choices and investor-driven mechanisms can include shareholder divestment to avoid harm and social impact investing. Action Track 4 on advancing equitable livelihoods and value distribution has a strong focus on strengthening community level coordination and multisectoral approaches. Action Track 5 on building resilience to vulnerabilities, shocks and stresses calls for an enhancement of investment in holistic food systems approaches that address people-planet prosperity and exploring blended finance facilities and public–private partnerships (PPP) for mobilizing finance for under-resourced initiatives to drive positive change in the food systems (UN, 2021).

Conclusions

Getting financing right is essential to realizing effective transformative adaptation for resilient agri-food livelihoods under the process of food system transformation. This means not only greatly expanding the availability of financial resources, but also to ensure these resources are accessible to those who need them, and that appropriate financing mechanisms are used to deliver them.

A common issue that arises in the analysis presented on the need, governance and current status of financing of adaptation is the importance of coordination. Coordination of financing from private, public, climate change and overseas development assistance sources is crucial to achieving additionality of climate finance as mandated by the Paris Agreement, and also as a key strategy for expanding the available pool of financial resources. Coordination of strategies and investments for rural transformation and transformative adaptation is essential to achieving effective adaptation in the context of improving agri-food livelihoods and enhancing the direction of financing to appropriate investments. Likewise, coordination of national adaptation policies with national economic and social development strategies and policies and with global climate change policy objectives laid out in the Paris Agreement is important in developing harmonized investment strategies, reducing transactions costs and increasing accessibility of finance to those who most need it. Coordination of rural communities in the planning and execution of adaptation investments in the context of food system transformation has emerged as a key factor in determining the effectiveness of adaptation actions.

MDBs are well placed to play a major role in achieving the increased levels of coordination required to achieve transformative adaptation under food system transformation. They are prominent in both the development and climate adaptation financing spheres, with links between national and international policy-makers and financing institutions. MDBs interact across different sources of financing, from concessional ODA to private sector via blended finance and co-financing structures. MDBs are key to achieving the level of transparency needed to account for climate finance and differentiating it from development financing. Through their input to the design of adaptation and food system transformation investments, MDBs can ensure that mechanisms to enhance the coordination of rural communities in managing financial resources are included and operational.

The analysis presented in this paper indicates that MDBs are already assuming important roles in the multiple levels of coordination required for transformative adaptation under food system transformation but also that they could do much more. MDBs could facilitate the expansion of financial resources by further engaging in structures of blended finance to increase private sector funding, using the tools and experience they have, as well as different financial instruments to address the barriers to expanded private sector finance, particularly risk and asymmetric information. The MDBs are already leading in developing tools and approaches for accounting for climate finance, reducing transactions costs associated with such financing and increasing accessibility of the finance. Here too however, more could be done by expanding the data and capacity for tracking adaptation investments and impacts in recipient countries. Fostering mechanisms to enhance coordination of rural communities and poor people engaged in agri-food system livelihoods is an important means of increasing accessibility of financing which MDBs can promote through investment project design and capacity building. Ensuring that appropriate financial mechanisms are used in adaptation financing, particularly the use of grant financing to incentivize the adoption of new and untried investments as well as investments with low or no financial returns but high returns to social and public benefits is an area where MDBs are already active via co-financing and blending financing arrangements, but here too more is needed.

In their unique capacity in combining technical expertise and capacity building with financing as well as their active role in both development and climate policy and financing at international and national levels, MDBs have the potential to address many of the shortcomings identified with current financing for transformative adaptation under food system transformation. Through recent commitments and innovations in financing approaches MDBs are already indicating important shifts in their approaches that can lead to improvements in the coordination and effectiveness of adaptation financing to support transformation of currently vulnerable and poor agri-food based livelihoods to ones that provide a decent standard of living and are resilient to climate change. Enlarging and expanding upon such shifts in the next few years will be key to realizing this objective.

Acknowledgements

This paper was prepared as a background paper for the 2021 IFAD Rural Development Report. We would like to thank the editors, the peer reviewers and other participants in the Rural Development Report, who provided comments on earlier drafts of this paper. We are solely responsible for any errors.

Biographies

Leslie Lipper

is a natural resource economist who has worked for over 30 years in the field of sustainable agricultural development. She holds a doctorate in Agricultural and Resource Economics from the University of California at Berkeley. She was the Executive Director of the Independent Science and Partnership Council of the CGIAR from 2016 to 2019 and the Senior Environmental Economist at the Food and Agriculture Organization for over 10 years. At present she holds a visiting fellow position at Cornell University, and she is a technical advisor to the Ceres 2030 project and senior advisor to IFAD on the 2021 Rural Development Report on Food Systems Transformation.

Romina Cavatassi

is the lead natural resource economist in the Research and Impact Assessment Division of IFAD where she is in charge of leading the Impact Assessment and research cluster in addition to leading the preparation of the Rural Development Report on Inclusive Food System Transformation. Prior to this role she was the lead technical Specialist for Environment and Climate in the Environment and Climate division of IFAD. Her expertise ranges from Impact assessment to evidence based analysis for decision and policy making particularly in the field of climate change, natural resource economics, poverty alleviation, survey design, training, data collection, data base management, data analysis, management. Prior to joining IFAD, Romina worked for FAO, where she focused on development and natural resource economics. She holds a PhD in natural resources and development economics from Wageningen University and Research Centre in the Netherlands, an MSc in environmental assessment and evaluation from the London School of Economics in the UK and a master’s-level degree in economics from the University of Bologna, Italy.

Ricci Symons

is a technical Specialist on Environment and Climate Change with the Environment Climate Gender and Social Inclusion division of IFAD. Ricci backstops and provide guidance to ensure quality implementation of the ASAP1 and contributed to its reporting, he also contributes to the design of the Rural Resilience Programme, resource mobilisation, providing technical inputs to projects, engagement with corporate events such as replenishment committees and executive boards, and deals with ad hoc senior management requests. Prior to IFAD, he worked at JP Morgan in both due diligence and compliance roles. He holds a BSc in Chemistry from the University of Cardiff (UK)

Ms. Alashiya Gordes

is a Technical Specialist with the Environment Climate Gender and social Inclusion and with the Operational Policy and Results divisions of IFAD. She works on IFAD’s climate results reporting and supporting the implementation of the IFAD11 mainstreaming commitments.

Prior to joining IFAD in 2019, Alashiya worked as a Natural Resources Officer in the Climate and Environment Division of the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, supporting countries to integrate agriculture in their National Adaptation Plans and promoting Climate-Smart Agriculture approaches. She has also worked with the Global Donor Platform for Rural Development in Bonn, Germany and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in Warsaw, Poland (at COP19).

Alashiya holds an MSc in Environmental Policy from the University of Oxford, UK. She is a national of Cyprus and Germany and speaks English, German, French, Italian and Greek.

Oliver Page

is the Lead Climate and Environment Specialist for the Latin America and the Caribbean Region (LAC) at IFAD. He has over 15 years’ experience working in the climate and environment field with specialization in mobilizing climate finance. Currently he is responsible for ensuring that IFAD’s LAC portfolio meets all climate, environment and social inclusion commitments, and that all projects adequately develop and apply IFAD environmental and social standards. He also leads LAC’s efforts in mobilizing external climate finance and has secured GCF financing for two IFAD/GCF projects in Belize and Brazil. Oliver has triple Argentinian/Uruguayan/British citizenship. He holds a Master’s degree in Environmental Policy from Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs, and a Bachelor’s degree in Environmental Engineering from Cornell University.

Authors' contributions

LL and RC conceived of the paper and wrote most of the text, RS, AG and OP contributed case study information and text.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

This article belongs to the Topical Collection: Food System Transformations for Healthier Diets, Inclusive Livelihoods and Sustainable Environment

Guest Editors: Romina E Cavatassi, Leslie Lipper, Ruerd Ruben, Eric Smaling, Paul Winters

Contributor Information

Leslie Lipper, Email: leslie.lipper@gmail.com.

Romina Cavatassi, Email: r.cavatassi@ifad.org.

Ricci Symons, Email: r.symons@ifad.org.

Alashiya Gordes, Email: a.gordes@ifad.org.

Oliver Page, Email: o.page@ifad.org.

References

- Afonina, M., Bohn, S., Hamad, M., Marti, A., & Pasha, A. (2021). Impact assessment report: Viet Nam and Adaptation to Climate Change in the Mekong Delta in Ben Tre and Tra Vinh Provinces, Viet Nam. IFAD, Rome, Italy.

- Alfani, F., Arslan, A., McCarthy, N., Cavatassi, R., & Sitko, N. J. (2019). Climate-change vulnerability in rural Zambia: the impact of an El Nino-induced shock on income and productivity. ESA Working Papers 288949, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Agricultural Development Economics Division (ESA).

- Arslan A, Belotti F, Lipper L. Smallholder productivity and weather shocks: Adoption and impact of widely promoted agricultural practices in Tanzania. Food Policy. 2017;69:68–81. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2017.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asfaw S, Maggio G. Gender, Weather Shocks and Welfare: Evidence from Malawi. The Journal of Development Studies. 2018;54(2):271–291. doi: 10.1080/00220388.2017.1283016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Auci S, Castellucci L, Coromaldi M. The impact of climate change on the distribution of rural income in Ethiopia. International Journal of Environmental Studies. 2018;75(6):913–931. doi: 10.1080/00207233.2018.1475914. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J., Bird, N., & Shalatek, L. (2010). Climate finance additionality: emerging definitions and their implications. ODI Climate Finance Policy Brief, 2. ODI UK.

- Brunner S, Enting K. Climate finance: A transaction cost perspective on the structure of state-to-state transfers, Global Environmental Change, Volume 27 2014. ISSN. 2014;138–143:0959–3780. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.05.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ceres2030. (2020). Sustainable Solutions to End Hunger Summary Report. IISD, IFPRI and Cornell University. Available at: https://ceres2030.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/ceres2030_en-summary-report.pdf

- Chavez Michaelsen A, Huamani Briceño L, Vilchez Baldeon H, et al. The effects of climate change variability on rural livelihoods in Madre de Dios, Peru. Regional Environmental Change. 2020;20:70. doi: 10.1007/s10113-020-01649-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, R., & Conway, G. (1991). Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: Practical Concepts for the 21st Century. Available at: http://www.smallstock.info/reference/IDS/dp296.pdf

- Chiriacò, M. V., Perugini, L., Bellotta, M., Kaugure, L., & Bernoux, M. (2021). Koronivia Joint Work on Agriculture – analysis of submissions on topics 2(e) and 2(f). Environment and Natural Resources Management Working Paper, 88. Rome, FAO. 10.4060/cb3978en

- Chiriac, D., Naran, B., & Falconer, A. (2020). Examining the climate finance gap for small-scale agriculture. Climate Policy Initiative and IFAD Rome.

- Climate Focus. (2016). Green Climate Fund and the Paris Agreement. Climate Focus Client Brief on the Paris Agreement V, February 2016. Available at: https://climatefocus.com/sites/default/files/GCF%20and%20Paris%20Brief%202016.new_.pdf

- Climate Policy Initiative (CPI). (2017). The global landscape of climate finance 2017: Methodology. https://climatepolicyinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/GLCF-2017-MethodologyDocument.pdf. The Coalition of Finance Mini.

- Climate Policy Initiative (CPI). (2019). Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2019 [Barbara Buchner, Alex Clark, Angela Falconer, Rob Macquarie, Chavi Meattle, Rowena Tolentino, Cooper Wetherbee]. Climate Policy Initiative, London. Available at: https://climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/global-climate-finance-2019

- Conevska A, Ford J, Lesnikowski A, Harper S. Adaptation financing for projects focused on food systems through the UNFCCC. Climate Policy. 2019;19(1):43–58. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2018.1466682. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Convergence Blended Capital. (2021a). Blended Finance Primer Accessed June 22 2021. https://www.convergence.finance/blended-finance

- Convergence Blended Capital. (2021b). Blended Finance & Agriculture Data Brief. May 2021 Covergence Capital https://www.convergence.finance/resource/0fdfc957-abd8-4a55-a315-36ac28cb1559/view

- Davis, B., Lipper, L., & Winters, P. (2021) Do not transform food systems on the backs of the rural poor. Food Security Forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Escalante, D., Abramskiehn, D., Hallmeyer, K., & Brown, J. (2018). Approaches to assess the additionality of climate investments: Findings from the evaluation of the Climate Public Private Partnership Programme (CP3) Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) UK. Available at: https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/approaches-to-assess-the-additionality-of-climate-investments-findings-from-the-evaluation-of-the-climate-public-private-partnership-programme-cp3/

- FAO. (2016a). State of Food and Agriculture Report (SOFA) Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security. FAO Rome.

- FAO. (2016b). The agricultural sector in Nationally Developed Contributions (NDCs). FAO Rome http://www.fao.org/3/a-i6400e.pdf

- FAO. (2017). The future of food and agriculture – Trends and challenges. Rome.

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. (2018). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2018. Building climate resilience for food security and nutrition. Rome, FAO.

- Fedele G, Donatti CI, Harvey CA, Hannah L, Hole DG. Transformative adaptation to climate change for sustainable social-ecological systems, Environmental Science & Policy, Volume 101. ISSN. 2019;116–125:1462–9011. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2019.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Few R, Morchain D, Spear D, et al. Transformation, adaptation and development: Relating concepts to practice. Palgrave Commun. 2017;3:17092. doi: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.92. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Global Center on Adaptation (GCA). (2020) State and Trends in Adaptation Report 2020. Building forward better from Covid-19: Accelerating Action on Climate Adaptation. Global Center on Adaptation. Available at: https://www.cas2021.com/documents/reports/2021/01/22/state-and-trends-in-adaptation-report-2020

- Global Center on Adaptation (GCA). (2019). Adapt now: A global call for leadership on climate resilience. Global Center on Adaptation and World Resources Institute. Available at: https://gca.org/report-category/flagship-reports/

- Havemann, T., Negra, C., & Werneck, F. (2020). Blended finance for agriculture: exploring the constraints and possibilities of combining financial instruments for sustainable transitions Agriculture and Human Values July 2020. 10.1007/s10460-020-10131-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- IFAD. (2016). Rural Development Report Fostering Inclusive Rural Transformation IFAD Rome.

- IFAD. (2019a). IFAD RDR 2021 – Framework for the Analysis and Assessment of Food Systems Transformations Background Paper IFAD Rural Development Report 2021.

- IFAD. (2019b). Climate Action Report IFAD Rome.

- IFAD. (2021). Kyrgyzstan Livestock and Market Development Program II. Project Completion Report. IFAD Rome.

- IPCC. (2012). – Field, C.B., V. Barros, T.F. Stocker, D. Qin, D.J. Dokken, K.L. Ebi, M.D. Mastrandrea, K.J. Mach, G.-K. Plattner, S.K. Allen, M. Tignor, and P.M. Midgley (Eds.) Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation. N Available from Cambridge University Press, The Edinburgh Building, Shaftesbury Road, Cambridge CB2 8RU ENGLAND, 582 pp.

- Jensen, A., Nielsen, H., & Russel, D. (2020). Climate Policy in a Fragmented World-Transformative Governance Interactions at Multiple Levels. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10017. 10.3390/su122310017

- Joint report on Multi-lateral Development Banks Climate Finance. (2019). https://publications.iadb.org/en/2019-joint-report-multilateral-development-banks-climate-finance

- Khan, M., Robinson, S. A., Weikmans, R., et al. (2020). Twenty-five years of adaptation finance through a climate justice lens. Climatic Change, 161, 251–269. 10.1007/s10584-019-02563-x

- Laborde, D., Parent, M., & Smaller, C. (2020). Ending Hunger, Increasing Incomes and Protecting the Climate – what will it cost donors? Ceres 2030 project https://ceres2030.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/ceres2030-what-would-it-cost_.pdf

- Mbouw, C., Rosenzweig, C., Barioni, L. G., Benton, T. G., Herrero, M., Krishnapillai, M., Liwenga, E., Pradhan, P., Rivera-Ferre, M. G., Sapkota, T., Tubiello, F. N., & Xu, Y. (2019). Food Security. In: Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems [P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, E. Calvo Buendia, V. Masson-Delmotte, H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, P. Zhai, R. Slade, S. Connors, R. van Diemen, M. Ferrat, E. Haughey, S. Luz, S. Neogi, M. Pathak, J. Petzold, J. Portugal Pereira, P. Vyas, E. Huntley, K. Kissick, M. Belkacemi, J. Malley, (eds.)]. In press

- Millan, A., Limketkai, B., & Guarnaschelli, S. (2019). Financing the Transformation of Food Systems Under a Changing Climate. CCAFS Report. Wageningen, the Netherlands: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS).

- Murphy, D., & Parry, J. (2020). Filling the Gap: A review of Multilateral Development Banks’ efforts to scale up financing for climate adaptation November 2020 IISD Ottowa.

- Nachmany, M., Rebecca, B., & Swenja, S. (2019). National laws and policies on climate change adaptation: a global review Policy Brief Grantham Research Institute on Climate and Environment. http://www.lse.ac.uk/GranthamInstitute/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/National-laws-and-policies-on-climate-change-adaptation_A-global-review.pdf

- Ray DK, West PC, Clark M, Gerber JS, Prishchepov AV, Chatterjee S. Climate change has likely already affected global food production. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(5):e0217148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, A., Aguilar, G., Bomba, K., Bonilla, J. P., Campbell, A., Echeverria, R., Gandhi, R., Hedegaard, C., Holdorf, D., Ishii, N., Quinn, K., Ruter, B., Sunga, I., Sukhdev, P., Verghese, S., Voegele, J., Winters, P., Campbell, B., Dinesh, D., Huyer, S., Jarvis, A., Loboguerrero Rodriguez, A. M., Millan, A., Thornton, P., Wollenberg, L., & Zebiak, S. (2020). Actions to transform food systems under climate change Wageningen, The Netherlands: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS).

- Thornton PK, Kristjanson P, Förch W, Barahona C, Cramer L, Pradhan S. Is agricultural adaptation to global change in lower-income countries on track to meet the future food production challenge? Global Environmental Change, Volume 52 2018. ISSN. 2018;37–48:0959–3780. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- UN. (2021). Food System Summit Action Tracks Website https://www.un.org/food-systems-summit/action-tracks. Accessed Jan 21 2021.

- Vermeulen, S. J., Dinesh, D., Howden, S. M., Cramer, L., & Thornton, P. K. (2018). Transformation in Practice: A Review of Empirical Cases of Transformational Adaptation in Agriculture Under Climate Change Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems VOL 2 2018 Article 65. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fsufs.2018.00065/full. 10.3389/fsufs.2018.00065. ISSN=2571–581X.

- Whitley, S., Thwaites, J., Wright, H., & Ott, C. (2018). Making finance consistent with climate goals Insights for operationalising Article 2.1c of the UNFCCC Paris Agreement. https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/resource-documents/12558.pdf

- Yeo, S. (2019). Where climate cash is flowing and why its not enough 2019. Nature, 573, 328–331. 10.1038/d41586-019-02712-3 [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.