Abstract

Introduction

Due to market expansion of electric-scooter companies, a significant rise of personal e-scooter use in dense, urban communities has been observed. No literature has specifically focused on e-scooter fracture epidemiology and risk factors associated with direct hospital admission. The aims of this study were to evaluate the 1) patterns of e-scooter related orthopaedic fractures 2) risk factors associated with direct hospital admission.

Materials and methods

A retrospective review of National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS) from the United States between 2015 and 2019 was utilized to identify e-scooter fracture epidemiology. Uni/multivariable analyses were conducted to identify independent variables associated with direct hospital admission.

Results

5,016 patients were identified. The most common fracture location was the upper extremity (25.4%). Multiple distinct fractures diagnoses (p < 0.001), fracture of the upper arm (p = 0.01), metacarpal (p = 0.03), skull(p < 0.001), and associated internal organ injury (p = 0.02) all had a statistical increase over time. Fracture of the upper leg (OR 58.31), lower trunk (OR: 47.04), and associated internal organ damage (OR: 37.82) had the greatest association with direct hospital admission.

Discussion

This study highlights that e-scooter fracture related injuries continue to progress, and without appropriate educational and public health efforts, these injuries will continue to rise.

Keywords: E-Scooter, Fracture, Orthopedic, Database, Epidemiology

1. Introduction

The continuous integration and impact of technological advancement within society has created alternative modes of transportation.1, 2, 3 Personal transporters, first popularized in 2001 by Segway, were initially expensive, restricted to a finite number of professions, and associated with specific injuries.4, 5, 6 Many of these injuries required hospital admission and surgical intervention. A systematic review evaluating Segway personal transport acute and emergent care management concluded that the most commonly reported injuries were orthopaedic, followed by maxillofacial, neurologic, and thoracic cases.5

From 2011 to 2017, there has been significant expansion of rental e-scooter companies such as Lime S-scooter, Lyft, and Uber. In 2018, the rental bikeshare company Bird alone has reported over 10 million rides.3 According to the National Association of City Transportation Officials, over 88 million were reported e-scooter rides in 2019, an increase from 38.5 million rides in 2018.7 The market of affordable personal stand-up electric scooters (e-scooters) in dense, urban communities has completely shifted the user demographic and associated injuries.1,8,9 In fact in June 2018, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) released public scooter-related prevention tips to assist parents and children.10 Furthermore, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) in accordance with the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) issued a public health statement recommending riders to be over age 16 and utilize safety equipment such as helmets and knee, elbow, and wrist guards.11

As the accessibility and use of e-scooters continues to rise, it is critical to evaluate the risk and injury associated with powered scooters. Namari et al. utilized the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS) from 2014 to 2018 and reported a dramatic increase in e-scooter injuries from 8,016 to 14,651. Age-adjusted injuries and hospital admissions increased by 222% and 365%, respectively.9 Furthermore, Trivedi et al. retrospectively investigated 249 patients presenting with electric scooter injuries to two emergency departments (ED). The most frequent injuries included fractures, head injury, and isolated contusions, sprains, and lacerations.12

Studies have clearly demonstrated the increase in e-scooter related injuries; however, no literature has specifically focused on the distribution of associated e-scooter fractures and risk factors associated with direct hospital admission. Therefore, the aims of this study were to evaluate the 1) epidemiological trends of e-scooter related orthopaedic fractures 2) identify diagnoses and orthopaedic fractures associated with direct hospital admission.

2. Materials and Methods

A retrospective review of the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS) from the United States was conducted between 2015 and 2019 to evaluate the trend and type of orthopaedic fracture injuries associated with the use of electric scooters. NEISS has established a national representation of emergency department (ED) visits by approximately 100 hospitals selected as a probability sample of all 5,000+ hospitals with emergency departments in the United States annually. The large sample size and probability weighted sampling allows for estimates generalizable to the national population.

To establish the appropriate cohort, ‘Electric Scooter (e-scooter) injuries were queried using the product code 5042 (‘Scooters/skateboards, powered’, Personal Transporters (stand-up), Hoverboards, Standup scooter, and skateboard, powered). Within this cohort, the primary diagnosis ‘fracture’ was identified using diagnosis code ‘57.’ Secondary diagnoses included were: concussion (52), Contusion, abrasions (53), hematoma (58), dislocation (55), laceration (59), and Intern organ injury (62). Mechanism of injury was identified via a manual review of the ‘free-text’ narrative of patient injury. Both categorical and continuous patient demographics were collected. Categorical variables included: anatomic location of injury, secondary diagnosis, mechanism of injury (e-scooter-motor vehicle collision (MVC), fall/crash, pedestrian-e-scooter), gender, ethnicity (White, Black, Asian, Other), location of injury, and disposition from ED.

NEISS anatomic location of injury was re-categorized as: head (scalp, parietal, occipital), face, shoulder, upper trunk (axilla, thoracic spine, chest, rib), upper arm (humerus), elbow (radial head), lower arm (ulna, radius), wrist, hand (metacarpal), finger (phalanges/phalanx), lower trunk (Lumbar spine, Femoral neck, Hip, Pelvis, Sacrum, Coccyx), upper leg (femur, trochanter), lower leg (fibula, tibia), knee, ankle, Foot/toe. Mechanism of injury was identified Disposition was recategorized as binary variable to assess direct hospital admission or not. Age was initially collected as a continuous variable; however, given the right-skewed distribution, age was analyzed as a categorical variable using the mean cohort age. Furthermore, year of injury was recategorized to 2015–2016, 2017–2018, and 2019.

Categorical variables were analyzed with Chi-square analysis. A univariate analysis was conducted to identify independent variables statistically associated with direct hospital admission. These independent variables were then analyzed in a multivariable logistic regression. A p-value less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA 15 (College Station, Texas: StataCorp LLC).

3. Results

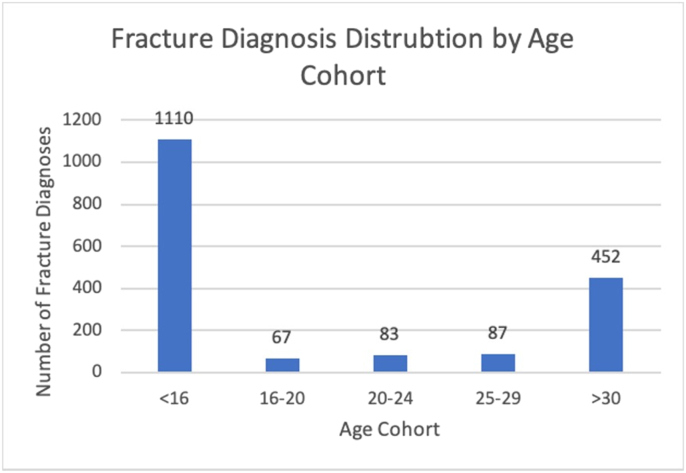

5,016 patients were identified between 2015 and 2019. Patient demographics and associated injuries are reported in Table 1. The mean cohort age was 23 (IQR: 10–32) with 2,302 (45.9%) females and 2,714 (54.1%) males. With regards to patient ethnicity, 2,030(40.5%), 1,102 (22.0%), 63 (1.3%), and 1,821 (36.3%) identified as White, Black, Asian, or Other. Fractures occurred in a bimodal distribution: 1110 (61.7%) and 453 (25.1%) fractures occurred under the age of 16 and over the age of 30, respectively (Fig. 1). With regards to mechanism of injury (MOI), 86.0% were attributed to ground level fall/crash, 6.3% due to pedestrian-scooter injury, and 4.5% were e-scooter-motor vehicle collision (MVC). MOI could not be identified in 3.3% of patients due to incomplete information. A statistically significant increase was observed among each MOI (p < 0.001) from 2015 to 2016, 2017–2018, and 2019.

Table 1.

This table presents the distribution of patient demographics and associated fracture location injuries from years 2015–2019. % = percent; p-value <0.05 is deemed statistically significant.

| 2015–2016 | 2017–2018 | 2019 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n = 5,016) | 1,376 | 2099 | 1,541 | |

| Hospital Admission(%) | 59 (4.3) | 119 (5.7) | 132 (8.6) | <0.001 |

| Age (%) | <0.001 | |||

| <23 | 951 (69.1) | 1491 (71.0) | 850 (55.2) | |

| >23 | 425 (30.9) | 608 (29.0) | 691 (44.8) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 715 (52.0) | 491 (52.6) | 874 (56.7) | 0.052 |

| Female | 661 (48.0) | 443 (47.4) | 667 (43.3) | |

| Ethnicity (%) | ||||

| White | 477 (34.7) | 912 (43.4) | 641 (41.6) | |

| Black | 282 (20.5) | 429 (20.4) | 391 (25.4) | <0.001 |

| Asian | 16 (1.2) | 22 (1.0) | 25 (1.6) | |

| Other | 601 (43.7) | 736 (35.1) | 484 (31.4) | |

| Mechanism of Injury | ||||

| E-Scooter-MVA | 38 (2.8) | 79 (3.8) | 107 (6.9) | <0.001 |

| Fall/Crash | 1,117 (85.4) | 1,791 (85.3) | 1,342 (87.1) | |

| E-scooter-Pedestrian | 113 (8.2) | 139 (6.6) | 63 (4.1) | |

| Fracture Diagnosis (%) | 512 (37.2) | 743 (35.4) | 544 (35.3) | 0.47 |

| Two Fracture Diagnosis (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 26 (1.7) | <0.001 |

| --Upper Extremity Fracture(%) | 384 (27.1) | 564 (26.4) | 403 (23.4) | 0.11 |

| Shoulder | 11 (0.8) | 24 (1.1) | 23 (1.5) | 0.22 |

| Upper arm | 20 (1.5) | 38 (1.4) | 39 (2.5) | 0.094 |

| Elbow | 36 (2.6) | 64 (3.0) | 62 (4.0) | 0.074 |

| Lower arm | 149 (10.8) | 208 (9.9) | 129 (8.4) | 0.06 |

| Wrist | 132 (9.6) | 186 (8.9) | 121 (7.9) | 0.27 |

| Hand | 5 (0.4) | 8 (0.4) | 11 (0.7) | 0.44 |

| Finger | 31(2.3) | 36 (1.7) | 18 (1.2) | 0.076 |

| Lower Limb Fracture (%) | 90 (6.5) | 59 (6.3) | 100 (6.5) | 0.97 |

| Upper Leg | 3 (0.2) | 5 (0.2) | 3 (0.2) | 0.96 |

| Lower Leg | 32 (2.3) | 46 (2.2) | 24 (1.6) | 0.27 |

| Knee | 3 (0.2) | 6 (0.3) | 11 (0.7) | 0.059 |

| Ankle | 29 (2.1) | 17 (1.8) | 32 (2.1) | 0.92 |

| Foot | 32 (2.3) | 14 (1.5) | 36 (2.3) | 0.31 |

| Trunk Fracture (%) | 20 (1.5) | 13 (1.4) | 34 (2.2) | 0.16 |

| Cervical | 3 (0.2) | 3 (0.1) | 3 (0.2) | 0.86 |

| Upper Trunk | 8 (0.6) | 8 (0.4) | 16 (1.0) | 0.046 |

| Lower Trunk | 9 (0.7) | 16 (0.8) | 15 (1.0) | 0.61 |

| Head Fracture (%) | 2 (0.1) | 7 (0.3) | 24 (1.6) | <0.001 |

| Fracture with Internal Organ Injury | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.3) | 0.01 |

Fig. 1.

This figure displays the presence of any fracture diagnosis by age cohort.

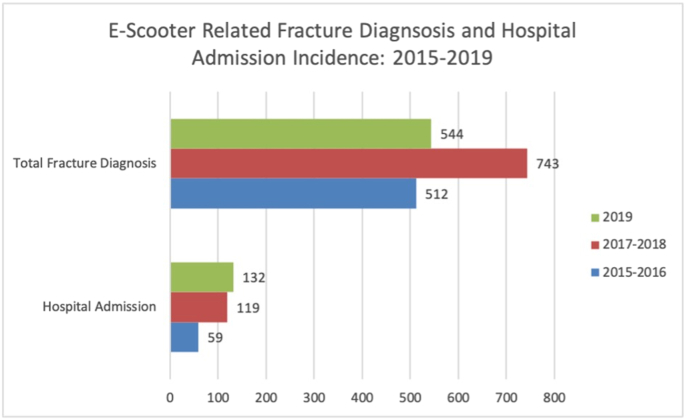

Of all fractures, 512 (37.2%), 743 (54.8%), and 544 (54.6%) with e-scooter injuries were reported between 2015 and 2016, 2017–2018, and 2019, respectively (chi2 = 1.74; p-value = 0.47). With regards to hospitalization, 41(8.7%), 88(13.4%), and 102(23.1%) of the fracture diagnoses with e-scooter injuries required admission between 2015 and 2016, 2017–2018, and 2019, respectively (chi2 = 25.09; p-value <0.001). These results indicate that although the number of reported fractures with e-scooter injuries does not statistically change from 2015 to 2019, the number of patients admitted to the hospital for fractures with e-scooter injuries does (Table 1, Fig. 2). The most common fracture location was the upper extremity (1,273; 25.4%). No statistical difference was observed between year and upper extremity fracture (Chi2: 1.97 p = 0.741). Of the upper extremity fractures, the lower arm (486; 9.7%) and wrist (439; 8.8%) reported the largest incidence. Lower extremity fractures had the second largest categorical incidence (320; 17.8%). Of the lower extremity fractures, foot (101; 31.6%) and ankle (99; 30.9%) fractures were most common. No statistical difference was observed between year and upper extremity fracture (Chi2: 6.10 p = 0.191).

Fig. 2.

This figure displays the number of hospital admissions and total fracture diagnoses from 2015-2016, 2017-2018, 2019.

When evaluating fracture type distribution between 2015 and 2019, multiple distinct fractures diagnoses (p < 0.001), fracture of the upper arm (p = 0.01), metacarpal (p = 0.03), skull(p < 0.001), and associated internal organ injury (p = 0.02) all had a statistical increase over time (Table 1).

Prior to 2019, no patients reported an e-scooter related diagnosis of either two distinct fractures or associated internal organ damage. In 2019, 30 (2.0%) of patients were documented to have either of those diagnoses present. This demonstrates variation in e-scooter associated fracture types with time.

To assess which patient factors/diagnoses have a statistical association with direct hospital admission, univariate analyses were first conducted (Table 2). Fracture with internal organ damage (OR: 45.98; 95% CI: 4.77–443.29; p-value 0.001) fracture of the upper leg (OR: 27.16; 95% CI: 7.90–93.28; p-value <0.001), and two fracture diagnosis (OR: 21.70; 95% CI: 7.90–93.28; p-value <0.001) were associated with the greatest odds of hospital admission when compared to individuals without those diagnoses. Additionally, patients with an MOI involving E-scooter and MVC reported a 9.10 (95% CI: 2.94–22.34; p < 0.001) increased odds of hospital admission compared to patients that fell/crash.

Table 2.

Univariate analysis evaluating independent variables associated with direct hospital admission. MVC = Motor Vehicle Collision; E-Scooter = Electric Scooter; OR = Odds Ratio; 95% CI = 95% Confidence Interval; p-value<0.05 statistically significant.

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fracture with Internal Organ Damage | 45.98 | 4.77–443.29 | 0.001 |

| Fracture of Upper Leg | 27.16 | 7.90–93.28 | <0.001 |

| Two Fracture Diagnosis | 21.70 | 9.88-47.67 | <0.001 |

| Fracture of Lower Trunk | 30.68 | 15.85-59.40 | <0.001 |

| Fracture of the Skull | 17.01 | 8.51-34.00 | <0.001 |

| Fracture of Lower Leg | 12.14 | 8.02–18.34 | <0.001 |

| Fracture Upper Trunk | 8.21 | 3.92-17.18 | <0.001 |

| Mechanism of Injury | |||

| Fall/Crash | REF | REF | |

| E-scooter-MVA | 9.23 | 2.12–23.12 | <0.001 |

| Pedestrian-E-Scooter | 2.10 | 1.01–4.65 | <0.001 |

| Fracture of Cervical Spine | 7.65 | 1.90-30.75 | 0.004 |

| Fracture of Knee | 6.61 | 2.52-17.33 | <0.001 |

| Fracture of Ankle | 4.59 | 2.81-7.49 | <0.001 |

| Year of Injury | |||

| 2015–2016 | REF | REF | REF |

| 2017–2018 | 1.34 | 0.97-1.87 | 0.72 |

| 2019 | 2.09 | 1.52-2.87 | <0.001 |

| Fracture of Upper arm | 2.87 | 1.63-5.03 | <0.001 |

| Age Over 23 | 2.20 | 1.75-2.78 | <0.001 |

| Fracture of Elbow | 2.35 | 1.47-3.78 | <0.001 |

| Male | 1.93 | 1.51-2.48 | <0.001 |

| Fracture of Lower Arm | 1.37 | 0.97-1.95 | 0.08 |

| Fracture of Wrist | 0.40 | 0.22-0.72 | 0.002 |

With regards to the multivariable analysis, the top three diagnoses associated with hospital admission were fracture of the upper leg (OR 58.31; 95% CI: 16.52–205.84; p-value <0.001), lower trunk (OR: 47.04; 95% CI: 23.08–95.85; p-value <0.001), and associated internal organ damage (OR: 37.82; 95% CI: 3.31–430.91; p-value = 0.003) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable Analysis evaluating independent variables associated with direct hospital admission. MVC = Motor Vehicle Collision; OR = Odds Ratio; 95% CI = 95% Confidence Interval; p-value<0.05 statistically significant.

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

| Fracture of Upper Leg | 58.31 | 16.52–205.84 | <0.001 |

| Fracture of Lower Trunk | 47.04 | 23.08–95.85 | <0.001 |

| Fracture with Internal Organ Damage | 37.82 | 3.31–430.91 | 0.003 |

| Fracture of Lower Leg | 22.35 | 14.11–35.38 | <0.001 |

| Fracture of the Skull | 16.67 | 7.66-36.30 | <0.001 |

| Mechanism of Injury | |||

| Fall/Crash | REF | REF | |

| E-scooter-MVA | 9.10 | 2.94-22.34 | <0.001 |

| Pedestrian-E-scooter | 1.87 | 0.98-4.31 | <0.001 |

| Fracture Upper Trunks | 8.79 | 3.79-20.43 | <0.001 |

| Fracture of Ankle | 7.72 | 4.51-13.21 | 0.016 |

| Fracture of Cervical Spine | 7.60 | 1.45-39.77 | <0.001 |

| Fracture of Knee | 7.87 | 2.71-22.88 | <0.001 |

| Fracture of Upper arm | 5.77 | 3.10–10.57 | <0.001 |

| Two Fracture Diagnosis | 4.14 | 1.50-11.45 | <0.001 |

| Fracture of Elbow | 4.24 | 2.52-7.15 | <0.001 |

| Fracture of Lower Arm | 2.84 | 1.91-4.23 | <0.001 |

| Male | 1.59 | 1.21-2.09 | <0.001 |

| Age Over 23 | 1.59 | 1.21-2.09 | <0.001 |

| Year of Injury | |||

| 2015–2016 | REF | REF | REF |

| 2017–2018 | 1.39 | 0.99-1.98 | 0.57 |

| 2019 | 1.48 | 1.18-2.42 | 0.004 |

| Fracture of Wrist | 0.86 | 0.46-1.63 | 0.661 |

When evaluating hospital admission trend from 2015 to 2019, patients with an e-scooter injury in 2017–2018 and 2019 had a 39.9% (95% CI: 0.99–1.97; p-value = 0.057) and 48% (95% CI: 1.18–2.42; p-value = 0.004) increased odds of hospital admission compared to years 2015–2016, respectively (Table 3).

4. Discussion

The aims of this retrospective study were to evaluate the 1) epidemiological trends of e-scooter related orthopaedic fractures 2) orthopaedic fractures associated with direct hospital admission. Our findings support the current evidence that the expansion of the electric scooter market has had a substantial increase in e-scooter injuries.

In this study cohort, the fracture location with the highest incidence was the upper extremity. Of the upper extremity fractures, the lower arm and wrist reported the largest incidence. Similarly, Mcilvain et al. retrospectively evaluated the NEISS database between 2015 and 2016, and reported that among 24,650 hoverboard related non-specific injuries, the upper extremity was the most common region injured.13 Additionally, Monteilh reported that among a retrospective cohort of 35 pediatric patients <18 years of age with associated electric hoverboard injuries, the upper extremity was the most common fracture location.14 Furthermore, this study reported that over 85% of e-scooter related injuries were due to ground level fall/crash. This can be explained by the fact that the most common injury mechanism is from falling off the scooter and causing an outstretched hand.8

Given that 61.7% of fracture diagnoses in this cohort were <16 years of age, the need for increased public health e-scooter education initiatives targeting the pediatric population is clearly warranted. Infrastructure improvements, as well as appropriate regulations to manage the rapid expansion of e-scooter share programs are equally essential for the safety of the young adolescents.15, 16, 17

When evaluating fracture trends over time, our results indicate that between 2015 and 2019, there was no statistical change in the incidence of e-scooter overall related fractures, trunks, and upper and lower extremities. This finding is supported by Namiri et al. who reported no statistical difference in sub-group injury anatomical locations, yet did observe a statistically significant increase in the overall proportion of all e-scooter injuries.9 Given that fractures are a subset of injury, this may provide an explain as to the lack of statistical significance of overall incidence of fractures compared to that of all e-scooter related injuries. The overall increase of e-scooter injuries should be addressed with regulations prohibiting poor e-scooter rider behaviors. Studies have shown evidence on factors that contribute to the prevalence of e-scooter injuries: failure of users to obey traffic rules, alcohol use, less helmet use, rider inexperience, and noncompliance with age restrictions.1,12,18,19 With regards to hospitalization, 59 (19.1%), 119 (5.7%), and 132 (42.6%) of the fracture diagnoses required admission 2015–2016, 2017–2018 and,2019 respectively (chi2 = 25.09; p-value <0.001). The top three diagnoses with the greatest odds of hospital admission were: fracture of the upper leg (OR: 58.31), lower trunk (OR: 47.04), and associated internal organ damage (OR: 37.82). These findings are supported by Namiri et al. who observed a 354% statistically significant increase in hospital admissions among patients between 18 and 34.9 Similar to other European, Israeli, and US based studies, the trend of hospital admissions has been increasing over time.17,20,21 These patients required a high rate of CT scan use, ICU admission, surgical care.12,22,23

Furthermore, prior to 2019, zero patients reported either two distinct fracture diagnoses or fracture with internal organ damage; however, in 2019, 30 (2.0%) of patients were documented to have either diagnosis. Patients with two distinct fracture diagnoses had 4.37 increased odds of hospital admission compared to patients without two distinct fracture diagnoses. Additionally, there was nearly a 3-fold increase in 2019 from 2015 to 2018 with regards to reported skull fracture cases [24 (1.7%) vs 9 (0.3%)]. Trivedi et al. retrospectively evaluated e-scooter injuries among 249 patients and noted that 94.3% of riders were not wearing a helmet.12This may indicate that the combination of ineffective public health e-scooter education and market expansion of e-scooters is contributing to potentially more severe and costly injuries. Campell et al. retrospectively reported that the summation of direct and indirect costs associated with treating e-scooter related orthopaedic surgery was approximately $19,282 per person.24 There is also some supporting evidence that the injury rate related to e-scooters might be higher than that of motorcycles and personal vehicles.16,25 Further granular data is warranted to understand the mechanism behind the increase in two-fracture diagnoses, including travel speed of e-scooter as well as protective gear utilized during time of injury.

To our knowledge, this is the largest national database study to specifically evaluate both e-scooter related fracture trajectory and risk factors associated with direct hospital admission. However, specific limitations must be addressed. First, the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System captures data from a wide demographic, but the course of patient management is limited to the final ED disposition. Assessing the overall hospital course and associated costs is not possible. Therefore, to evaluate the true societal implications of e-scooter fracture injuries, the combination of both national database and institutional reports are required. Second, NEISS's group of anatomic location is quite broad. For example, lower trunk comprises diagnoses such as: pelvis, femoral neck, lumbar vertebrae. Fractures that occur at these locations have substantial variation in clinical management; therefore, the inability to evaluate the specific anatomic location on a more granular level requires further investigation using other resources. Third, the ability to assess the severity of fracture was not possible. For example, diagnoses codes do not differentiate between closed vs open fractures, simple vs comminuted fractures, or unilateral vs bilateral. For example, a patient with a bilateral comminuted grade III open distal tibia fracture would have the same reported code as a closed simple unilateral tibial fracture. Fourth, as a database study, there are potential differences in data collection at each site. For example, whether or not a pedestrian struck by an e-scooter is included may vary. Finally, NEISS groups together multiple electric vehicles, such as e-scooters and electronic skateboards. While all propelled electrically, nuances in riding technique between these vehicles may lead to varying injury patterns. Given these limitations, this study highlights that e-scooter fracture related injuries continue to progress, and without appropriate educational and public health efforts, these injuries will continue to rise.

5. Conclusion

This study highlights that e-scooter fracture related injuries requiring direct hospitalization continue to progress, and without appropriate educational and public health efforts, these injuries will continue to rise.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None:

References

- 1.Badeau A., Carman C., Newman M., Steenblik J., Carlson M., Madsen T. Emergency department visits for electric scooter-related injuries after introduction of an urban rental program. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37(8):1531–1533. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2019.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck S., Barker L., Chan A., Stanbridge S. Emergency department impact following the introduction of an electric scooter sharing service. Emerg Med Australasia (EMA) 2020;32(3):409–415. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.13419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yakowicz W. 14 Months, 120 Cities, $2 Billion: There's Never Been a Company like Bird. Is the World Ready? Inc. Magazine.

- 4.Boniface K., McKay M.P., Lucas R., Shaffer A., Sikka N. Serious injuries related to the Segway® personal transporter: a case series. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57(4):370–374. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.06.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pourmand A., Liao J., Pines J.M., Mazer-Amirshahi M. Segway® personal transporter-related injuries: a systematic literature review and implications for acute and emergency care. J Emerg Med. 2018;54(5):630–635. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2017.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roider D., Busch C., Spitaler R., Hertz H. Segway® related injuries in vienna: report from the Lorenz Böhler Trauma centre. Eur J trauma Emerg Surg Off Publ Eur Trauma Soc. 2016;42(2):203–205. doi: 10.1007/s00068-015-0532-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shared Micromobility in the. U.S.; 2019. p. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blomberg S.N.F., Rosenkrantz O.C.M., Lippert F., Collatz Christensen H. Injury from electric scooters in Copenhagen: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(12) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Namiri N.K., Lui H., Tangney T., Allen I.E., Cohen A.J., Breyer B.N. Electric scooter injuries and hospital admissions in the United States, 2014-2018. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(4):357–359. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.5423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.AAOS. Scooter-Related Injury Prevention . 2018. OrthoInfo.https://www.orthoinfo.org/en/staying-healthy/scooter-related-injury-prevention Published. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sobel A.D., Reid D.B., Blood T.D., Daniels A.H., Cruz A.I.J. Pediatric orthopedic hoverboard injuries: a prospectively enrolled cohort. J Pediatr. 2017;190:271–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trivedi T.K., Liu C., Antonio A.L.M. Injuries associated with standing electric scooter use. JAMA Netw open. 2019;2(1) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McIlvain C., Hadiza G., Tzavaras T.J., Weingart G.S. Injuries associated with hoverboard use: a review of the national electronic injury surveillance System. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37(3):472–477. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2018.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monteilh C., Patel P., Gaffney J. Musculoskeletal injuries associated with hoverboard use in children. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2017;56(10):909–911. doi: 10.1177/0009922817706143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Puzio T.J., Murphy P.B., Gazzetta J. The electric scooter: a surging new mode of transportation that comes with risk to riders. Traffic Inj Prev. 2020;21(2):175–178. doi: 10.1080/15389588.2019.1709176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schlaff C.D., Sack K.D., Elliott R.-J., Rosner M.K. Early experience with electric scooter injuries requiring neurosurgical evaluation in District of Columbia: a case series. World Neurosurg. 2019;132:202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.08.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siman-Tov M., Radomislensky I., Peleg K. The casualties from electric bike and motorized scooter road accidents. Traffic Inj Prev. 2017;18(3):318–323. doi: 10.1080/15389588.2016.1246723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bresler A.Y., Hanba C., Svider P., Carron M.A., Hsueh W.D., Paskhover B. Craniofacial injuries related to motorized scooter use: a rising epidemic. Am J Otolaryngol. 2019;40(5):662–666. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2019.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trivedi B., Kesterke M.J., Bhattacharjee R., Weber W., Mynar K., Reddy L.V. Craniofacial injuries seen with the introduction of Bicycle-share electric scooters in an urban setting. J oral Maxillofac Surg Off J Am Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;77(11):2292–2297. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2019.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kosola S., Salminen P., Kallio P. Driver's education may reduce annual incidence and severity of moped and scooter accidents. A population-based study. Injury. 2016;47(1):239–243. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2015.10.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kosola S., Salminen P., Laine T. Heading for a fall - moped and scooter accidents from 2002 to 2007. Scand J Surg SJS Off organ Finnish Surg Soc Scand Surg Soc. 2009;98(3):175–179. doi: 10.1177/145749690909800309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kobayashi L.M., Williams E., Brown C.V. The e-merging e-pidemic of e-scooters. Trauma Surg acute care open. 2019;4(1) doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2019-000337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayhew L.J., Bergin C. Impact of e-scooter injuries on Emergency Department imaging. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2019;63(4):461–466. doi: 10.1111/1754-9485.12889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campbell A., Wong N., Monk P., Munro J., Bahho Z. The cost of electric-scooter related orthopaedic surgery. N Z Med J. 2019;132(1501):57–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.García Reyes L.E. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling. 2013. Electric scooters were to blame for at least 1,500 injuries and deaths in the US last year.https://www.businessinsider.com/minimum-of-1500-us-e-scooter-injuries-in-2018-2019-2 Published. [Google Scholar]