S. aureus steals iron in the form of haem from human haemoglobin (Hb). The crystal structure of the S. aureus Hb receptor IsdH in complex with Hb shows that the receptor induces a conformational change in the globin haem pocket that may promote haem transfer.

Keywords: iron-regulated surface determinant, NEAT domain, haemoglobin, Staphylococcus aureus

Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus is a common and serious cause of infection in humans. The bacterium expresses a cell-surface receptor that binds to, and strips haem from, human haemoglobin (Hb). The binding interface has previously been identified; however, the structural changes that promote haem release from haemoglobin were unknown. Here, the structure of the receptor–Hb complex is reported at 2.6 Å resolution, which reveals a conformational change in the α-globin F helix that disrupts the haem-pocket structure and alters the Hb quaternary interactions. These features suggest potential mechanisms by which the S. aureus Hb receptor induces haem release from Hb.

1. Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus is a Gram-positive bacterial pathogen that is carried asymptomatically by approximately one third of the human population, and yet has the capacity to cause fatal invasive infection (Kluytmans et al., 1997 ▸). Although S. aureus strains that are resistant to β-lactam antibiotics have traditionally been associated with hospital-acquired infections, antibiotic-resistant strains have now become commonplace in the general community (Dukic et al., 2013 ▸). Understanding the mechanisms that S. aureus uses to survive inside the human host is an important step towards the discovery of new treatments that neutralize pathogen virulence. Iron-uptake pathways are of interest in this regard because iron is required by many essential bacterial enzymes, and access to iron is necessary for bacterial infection (Nairz et al., 2010 ▸). The most abundant form of iron in the human body is haem (iron protoporphyrin-IX), and the majority of haem is found in haemoglobin (Hb). S. aureus has evolved a pathway, encoded by nine iron-regulated surface determinant (isd) genes (Mazmanian et al., 2003 ▸; Morrissey et al., 2002 ▸), that is specialized for the uptake of haem/iron from human Hb (Pishchany et al., 2010 ▸).

Two of the Isd proteins, IsdB and IsdH, are cell-surface proteins that bind to Hb and remove haem groups by a process that is not completely understood (Dryla et al., 2003 ▸, 2007 ▸; Torres et al., 2006 ▸; Pilpa et al., 2009 ▸; Pishchany et al., 2010 ▸; Krishna Kumar et al., 2011 ▸; Dickson et al., 2014 ▸). IsdB and IsdH supply two haem chaperones, IsdA and IsdC, which relay haem to the substrate-binding subunit (IsdE) of a haem transporter that spans the bacterial cell membrane (IsdF) (Zhu et al., 2008 ▸; Liu et al., 2008 ▸; Muryoi et al., 2008 ▸; Tiedemann et al., 2012 ▸; Grigg et al., 2007a ▸, 2010 ▸; Pluym et al., 2007 ▸; Tiedemann & Stillman, 2012 ▸). IsdH binds more tightly to iron(III) haem than to iron(II) haem (Moriwaki et al., 2011 ▸), suggesting that the Hb receptors target ferric metHb, which forms rapidly following erythrocyte lysis. Inside the bacterial cytoplasm the porphyrin macrocycle is cleaved by either of two haem oxygenase enzymes, IsdG or IsdI, to release iron (Wu et al., 2005 ▸).

IsdA/B/C/H proteins are all anchored via a C-terminal amide linkage to the peptide cross-bridge of the cell-wall peptidoglycan (Mazmanian et al., 2002 ▸), and all bind haem via a near iron transporter (NEAT) domain, which is an antiparallel β-barrel domain of 15–20 kDa with an immunoglobulin-like topology (Vu et al., 2013 ▸; Moriwaki et al., 2011 ▸; Watanabe et al., 2008 ▸; Pilpa et al., 2006 ▸; Grigg et al., 2007b ▸, 2011 ▸; Villareal et al., 2008 ▸; Sharp et al., 2007 ▸; Gaudin et al., 2011 ▸). Related NEAT domains that function in haem acquisition have been described in Streptococcus pyogenes (Aranda et al., 2007 ▸), Listeria monocytogenes (Malmirchegini et al., 2014 ▸) and Bacillus anthracis (Ekworomadu et al., 2012 ▸; Honsa et al., 2013 ▸), highlighting the importance of NEAT domains for iron uptake in Gram-positive pathogens. The haem-binding site in the NEAT domain is located between a short 310-helix and the β-hairpin formed by β-strands 6 and 7 (numbered according to homology with the immunoglobulin domain topology). The haem iron is typically five-coordinate iron(III) (Pluym et al., 2008 ▸; Vermeiren et al., 2006 ▸) and is bound to the protein through the first Tyr side chain from a conserved YxxxY motif in β-strand G. IsdB and IsdH contain one or two additional NEAT domains, respectively, that lack haem-binding activity and instead bind to Hb chains at a site comprising parts of the A and E helices of the globin (Dryla et al., 2003 ▸, 2007 ▸; Pilpa et al., 2009 ▸; Pishchany et al., 2010 ▸; Krishna Kumar et al., 2011 ▸; Dickson et al., 2014 ▸).

A three-domain region of IsdH comprising the Hb-binding second NEAT domain (IsdHN2) and haem-binding third NEAT domain (IsdHN3) separated by an α-helical linker domain (IsdHLinker) is required to capture haem from Hb (Spirig et al., 2013 ▸; Dickson et al., 2014 ▸). This three-domain region of IsdH, referred to hereafter as IsdHN2N3 (Fig. 1 ▸ a), shares 62% sequence homology with IsdB. Haem transfer from metHb to IsdB occurs with a rate constant k = 0.31 s−1 at 25°C (Zhu et al., 2008 ▸). Haem transfer from metHb to IsdHN2N3 is biphasic, with rate constants of 0.85 and 0.099 s–1 (Sjodt et al., 2015 ▸). These rates are 2–3 orders of magnitude faster than the thermal dissociation of haem from the β (k = 0.003 s−1) or α (k = 0.0002 s−1) sites of metHb under similar solution conditions (Hargrove et al., 1996 ▸), indicating that the receptors activate haem release from metHb. To investigate the mechanism of haem extraction, we previously determined the structure of IsdHN2N3 bound to metHb by X-ray crystallography at a resolution of 4.2 Å (PDB entry 4ij2; Dickson et al., 2014 ▸). In this structure, IsdHN2N3 carried an Ala mutation of the haem-ligating Tyr642 (located in the IsdHN3 domain), resulting in crystallization of the IsdHN2N3–metHb complex in a state prior to haem transfer. The crystal structure with PDB code 4ij2 contained a metHb tetramer with one IsdHN2N3 receptor bound to each of the four globin chains. IsdHN2N3 bound α or β subunits in a similar manner, with the haem-accepting IsdHN3 domain positioned precisely over the entrance to the globin haem pocket. However, the data resolution was not sufficient to identify the tertiary-structure changes in the globin that are presumed to facilitate haem transfer.

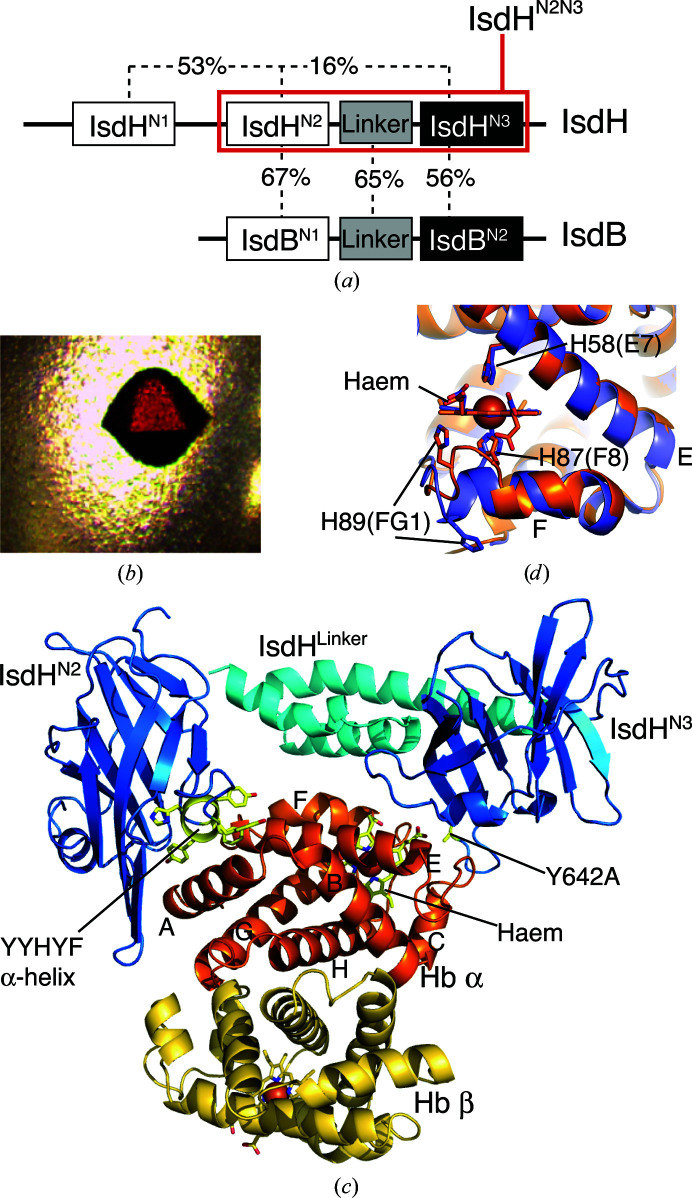

Figure 1.

(a) Domain structure of S. aureus IsdB and IsdH, and sequence homology between these domains. The construct crystallized in this study contains the domains highlighted in red (IsdHN2N3). (b) Crystal of IsdHN2N3–metHb. (c) The crystallographic asymmetric unit contained an Hb αβ dimer with a single molecule of IsdHN2N3 bound to the α subunit. (d) Detail of the haem-pocket region of the α subunit from IsdHN2N3–metHb (orange) overlayed with the metHb structure (PDB entry 3p5q; slate blue)

In this work, we have engineered mutations into the IsdHN2 domain of IsdHN2N3 that effectively blocked binding to Hb β subunits, but left binding to Hb α unchanged. Crystals grown using this mutant gave dramatically improved diffraction quality. We report the crystal structure of metHb with IsdHN2N3 bound only at the Hb α subunits at a resolution of 2.6 Å. The structure reveals a disturbance of the globin haem pocket and provides a potential mechanism for haem release.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Mutagenesis

The IsdH expression vector used in this study was a modified version of the pRM208 plasmid, which contained the second and third NEAT domains and the intervening IsdHLinker domain of IsdH (IsdHN2N3 residues 326–660) cloned between the BamHI and XhoI sites of the pHis-SUMO vector (Spirig et al., 2013 ▸). The modified QuikChange method of Liu & Naismith (2008 ▸) was used to introduce IsdH mutations FYHYA(365–369)→YYHYF and Y642A into the pRM208 plasmid.

2.2. Protein production

IsdHN2N3 carrying the FYHYA(365–369)→YYHYF and Y642A mutations was transformed into E. coli strain Rosetta2 (DE3) pLysS and expression was performed at 37°C in LB broth containing 34 µg ml−1 chloramphenicol and 50 µg ml−1 kanamycin with addition of 1 mM IPTG to induce expression. The expressed protein comprised the N-terminal sequence MGSSHHHHHHSSGLVPRGSHMAS followed by the 11.3 kDa ubiquitin-like protein SMT3 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae followed by the IsdH region of interest. This protein was purified at 4°C over IMAC resin (HIS-Select Nickel Affinity gel, Sigma). Fractions containing the fusion protein were pooled and mixed in a 100-fold molar excess over His-tagged ubiquitin-like protein-1 protease for 1 h at room temperature. Following dialysis, the mixture was reapplied onto the IMAC column to remove the His-SUMO tag and His-tagged ubiquitin-like protein-1 protease. Additional purification steps were performed by anion-exchange (Q Sepharose, GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and gel-filtration (Superose 12HR, GE Healthcare Life Sciences) chromatography.

Hb was purified from blood as reported previously (Gell et al., 2002 ▸). During Hb purification the globin was maintained in the carbon monoxide-liganded state to inhibit autooxidation. Although we required oxidized metHb for structural work, purification in the HbCO form was beneficial to inhibit the autooxidation and subsequent irreversible denaturation that otherwise occurred. Briefly, red blood cells, freshly collected from a human volunteer, were washed in saline solution and then lysed under hypotonic conditions. Hb was purified from the haemolysate by cation-exchange chromatography (SP Sepharose, GE Healthcare Life Sciences) followed by anion-exchange chromatography (Q Sepharose, GE Healthcare Life Sciences). HbCO was converted to HbO2 by passing a pure stream of oxygen over a protein solution held on ice and illuminated with a high-intensity light source. HbO2 was converted to ferric metHb by incubation with a fivefold molar excess of potassium ferricyanide at ∼10°C in 20 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.0. The reaction was monitored to completion by UV–visible spectroscopy and metHb was isolated over G-25 Sepharose (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). The concentration of Hb was determined by UV–visible absorption spectroscopy using the molar absorption coefficients ɛ419 = 192 000 M −1 cm−1 and ɛ539 = 13 900 M −1 cm−1 for HbCO and ɛ405 = 169 000 M −1 cm−1 and ɛ500 = 9000 M −1 cm−1 for metHb (Eaton & Hofrichter, 1981 ▸)

2.3. Haemoglobin-binding assays

Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) experiments were performed on Superose 12 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) equilibrated in 150 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.0. Proteins were mixed at the concentrations indicated and 100 µl samples were loaded onto the column. Elution of protein samples was monitored at 280 or 410 nm with a Jasco UV2070 detector.

2.4. Crystallization

IsdHN2N3 mutant protein and metHb were buffer-exchanged into 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, mixed in a 2:1 molar ratio to give a final protein concentration of 11.1 mg ml−1 and subjected to sparse-matrix crystallization screening at 21°C. Hexagonal crystals grew reproducibly in 0.2 M potassium/sodium tartrate, 0.1 M trisodium citrate pH 5.6, 2 M ammonium sulfate. In a fine screen, crystals of identical morphology were obtained over a pH range of 5.4–5.8 and a precipitant concentration of 2.0–2.2 M ammonium sulfate. The crystals were cryoprotected in up to 30% glycerol before being flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen.

2.5. Data collection and processing

Diffraction data were collected on the MX1 beamline at the Australian Synchrotron to a resolution of 2.55 Å. The data were integrated with iMosflm (Leslie & Powell, 2007 ▸) and scaled using AIMLESS (Evans & Murshudov, 2013 ▸). Table 1 ▸ contains the collection and refinement statistics.

Table 1. Data-collection and refinement statistics.

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| Data collection | |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.95370 |

| Space group | P6522 |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å, °) | a = b = 92.22, c = 365.12, α = β = 90, γ = 120 |

| Resolution (Å) | 33.39–2.55 (2.66–2.55) |

| Observed reflections | 342621 |

| Unique reflections | 33107 |

| R merge † (%) | 13.3 (78.4) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 9.3 (2.0) |

| CC1/2 ‡ | 0.996 (0.766) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (100) |

| Multiplicity | 9.6 (9.7) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 33.39–2.55 (2.61–2.55) |

| Reflections in working set | 29544 |

| Reflections in test set | 1581 |

| R work (%) | 25.9 (36.4) |

| R free § (%) | 28.7 (39.2) |

| No. of non-H atoms | |

| Protein | 4775 |

| Ligand/ion | 94 |

| Water | 4 |

| B factors (Å2) | |

| Protein | 63.4 |

| Ligand/ion | 77.7 |

| Water | 40.0 |

| R.m.s. deviations¶ | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.004 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.8 |

| Ramachandran plot†† | |

| Most favoured (%) | 96.6 |

| Allowed (%) | 3.1 |

| Outliers (%) | 0.3 |

| PDB code | 4xs0 |

R merge = \textstyle \sum_{hkl}\sum_{i}|I_{i}(hkl)- \langle I(hkl)\rangle|/\textstyle \sum_{hkl}\sum_{i}I_{i}(hkl).

Values of CC1/2 according to Karplus & Diederichs (2012 ▸).

R free was calculated using 5% of the reflections, which were chosen at random and excluded from the data set.

Deviations from ideal values (Engh & Huber, 1991 ▸).

Calculated using MolProbity (Chen et al., 2010 ▸).

2.6. Structure solution and refinement

The structure was solved by molecular replacement. The search model was derived from the 4.2 Å resolution complex of IsdH bound to metHb (PDB entry 4ij2) and included an Hb αβ dimer with one IsdHN2N3 bound through the α subunit. Molecular replacement performed with Phaser (McCoy et al., 2007 ▸) gave rise to a single solution. A single round of rigid-body refinement followed by multiple rounds of restrained refinement were performed with REFMAC 5.7 (Murshudov et al., 2011 ▸) and model building was completed with Coot (Emsley & Cowtan, 2004 ▸). In later rounds of refinement, translation/liberation/screw refinement was introduced, with groups defined as single domains (where the IsdHLinker–IsdHN3 unit was considered to be a single group). The final model was validated using MolProbity (Chen et al., 2010 ▸). Ramachandran statistics for the final model are as follows: 96.6% of residues were found in favoured regions and 3.1% in allowed regions. The structure factors and coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank as entry 4xs0.

2.7. Analysis of Hb tertiary and quaternary structure

To understand quaternary-structural changes in Hb, Baldwin and Chothia identified a set of residues in the α1β1 dimer with unchanged positions in the liganded relaxed (R) and ligand-free tense (T) states that act as a reference frame for tertiary- and quaternary-structural transitions, referred to as the BGH frame and comprising residues α30–α36, α101–α113, α117–α127 and β30–β36, β51–β55, β107–β132 (Baldwin & Chothia, 1979 ▸). The reference set was updated by Park and coworkers based on higher resolution (1.25 Å) structures to comprise residues α23–α42, α57–α63, α101–α111, α118–α125 and β51–β57, β110–β116, β119–β132 (Park et al., 2006 ▸). In this study, we perform overlays using the original BGH frame, but note that the results are not significantly altered when using the reference frame of Park and coworkers. Relative rotations/translations of αβ dimers were calculated using DynDom (Hayward & Berendsen, 1998 ▸). To emphasize the structural features of the haem pocket that are conserved between the α and β subunits, and across other globins with divergent sequences, amino-acid residues are identified (in parentheses) according to their corresponding helix, and position in the helix, in the related structure of sperm whale myoglobin, which is the standard reference structure by convention. For example, αHis87(F8) indicates a residue with structural similarity to the eighth residue in helix F of sperm whale myoglobin, which is the haem-ligating proximal His.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Engineering of IsdH to remove weak binding to Hb β chains

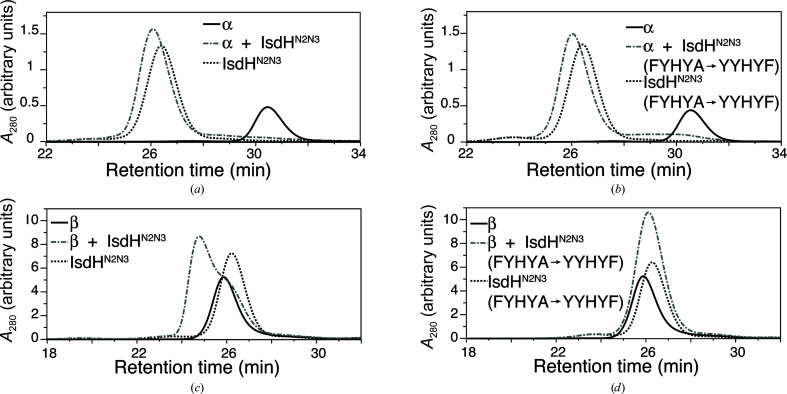

In the crystal structure with PDB code 4ij2, electron density was missing for the haem-acceptor IsdHN3 domain belonging to one of the four IsdHN2N3 receptors in the crystallographic asymmetric unit, suggesting disorder in the position of this IsdHN3 domain. The ‘missing’ domain belonged to an IsdHN2N3 receptor that was bound to an Hb β subunit. We hypothesized that steric factors might interfere with the simultaneous binding of IsdH to all four globin subunits of a single Hb tetramer and, therefore, that selectively removing binding to either the α or β subunits might allow the growth of crystals that are better ordered. Based on comparison of the globin-interaction face of IsdHN2, which binds to both α and β subunits, with the globin-interaction face of IsdHN1, which binds to α but not β (Krishna Kumar et al., 2011 ▸), we identified a short α-helix, rich in aromatic side chains, as a site that potentially influences α/β binding selectivity. We constructed an IsdHN2N3 variant in which residues in the IsdHN2 domain, FYHYA (365–369; interfacial residues are underlined), were replaced with the corresponding interfacial residues from IsdHN1 to give YYHYF. IsdHN2N3 carrying the FYHYA(365–369)→YYHYF mutation bound to Hb α with similar affinity as the wild-type IsdHN2N3 sequence, as judged by complex formation assayed by gel filtration (compare Fig. 2 ▸ a with Fig. 2 ▸ b). However, compared with the wild-type IsdHN2N3 (Fig. 2 ▸ c), IsdHN2N3 carrying the FYHYA(365–369)→YYHYF mutation showed a dramatic loss of binding to βHb (Fig. 2 ▸ d). These mutations, which are located in the N-terminal NEAT domain, preserve biologically relevant binding to the α subunit and do not impede interpretation of the haem-transfer interface mediated by the C-terminal NEAT domain.

Figure 2.

IsdHN2N3 carrying the FYHYA(365–369)→YYHYF mutation binds Hb α but not Hb β. (a) An equimolar mixture of α and IsdHN2N3 eluted predominantly as a single peak from SEC (grey dashed–dotted line), indicating the formation of a protein complex. Elution profiles for free α (solid line) and IsdHN2N3 (dotted line) are shown for comparison. (b) An equimolar mixture of α and IsdHN2N3 carrying the FYHYA→YYHYF mutation eluted predominantly as a single peak from SEC (grey dashed–dotted line), indicating the formation of a complex with a similar elution time to the wild-type complex in (a). (c) An equimolar mixture of β and IsdHN2N3 (grey dashed–dotted line) produced a peak with an earlier elution time than free β (solid line) or IsdHN2N3 (dotted line), indicating the formation of a complex between β and IsdHN2N3. (d) An equimolar mixture of β and IsdHN2N3 carrying the FYHYA→YYHYF mutation yields an elution profile (grey dashed–dotted line) as expected for a mixture of free β (solid line) and IsdHN2N3 (dotted line); thus, no interaction was detected between β and IsdHN2N3 carrying the FYHYA→YYHYF mutation. Note that α is predominantly a monomer, whereas β is predominantly a tetramer under the conditions of the assay, explaining the substantial difference in the elution time of the free Hb chains.

For crystallography, the FYHYA(365–369)→YYHYF mutation was combined with a Y642A substitution of the haem-ligating side chain in the IsdHN3 domain, which was also present in the 4ij2 structure, to prevent haem transfer and minimize disassembly of the apo Hb complex (Spirig et al., 2013 ▸). The engineered IsdHN2N3 protein was mixed with Hb in a 2:1 molar ratio. Hexagonal crystals grew in 0.2 M potassium/sodium tartrate, 0.1 M trisodium citrate over a pH range of 5.4–5.8 and a precipitant concentration range of 2.0–2.2 M ammonium sulfate (Fig. 1 ▸ b).

3.2. Overall structure of the IsdHN2N3–metHb complex

The structure of IsdHN2N3–metHb carrying the FYHYA(365–369)→YYHYF and Y642A mutations was determined to a resolution of 2.55 Å and refined to an R cryst and R free of 0.259 and 0.287, respectively (Table 1 ▸). The crystallographic asymmetric unit contains an Hb αβ dimer, with a single IsdHN2N3 receptor bound to the α subunit (Fig. 1 ▸ c), suggesting that our protein-engineering approach to improve crystal order by removing binding to the β subunit was successful. Hydrogen bonds and salt bridges at the IsdHN2N3–metHb interface are shown in Table 2 ▸. Symmetry-related αβ dimers form a Hb tetramer in the crystal; however, the relative positioning of αβ dimers does not correspond to the canonical T (low O2 affinity) or R (high O2 affinity) quaternary structures of Hb (Perutz et al., 1960 ▸; Muirhead & Perutz, 1963 ▸) and is more similar to two recently determined structures of fully liganded Hbs with a T-like quaternary structure (Safo et al., 2013 ▸; Balasubramanian et al., 2014 ▸; discussed further below).

Table 2. Hydrogen-bonding and salt-bridge interactions at the IsdHN2N3–metHb interfaces.

| IsdHN2N3 (chain C) | Hb α subunit (chain A) | Distance (Å) |

|---|---|---|

| Tyr443 OH | Asn9 OD1 | 2.71 |

| Lys391 NZ | Ala71 O | 3.13 |

| Tyr421 OH | Asp74 OD2 | 2.52 |

| Tyr495 OH | Ser81 O | 3.90 |

| Lys503 NZ | Ser81 OG | 3.81 |

| Tyr495 OH | Asp85 OD2 | 2.72 |

| Thr392 OG1 | Lys11 NZ | 2.98 |

| Ser370 OG | Lys11 NZ | 2.83 |

| Glu449 OE2 | Lys16 NZ | 2.92 |

| Tyr365 OH | Ala19 N | 3.39 |

| Tyr646 OH | His45 NE2 | 3.24 |

| Glu562 OE2 | Gln54 NE2 | 3.87 |

| Val564 O | Gln54 NE2 | 3.58 |

| Ser563 O | Gln54 NE2 | 3.45 |

| Lys499 NZ | Asp85 OD2 | 3.63 |

| Glu449 OE1 | Lys16 NZ | 3.38 |

| Glu449 | Lys16 NZ | 2.92 |

| Haem O1D | Tyr646 OH | 2.95 |

| Haem O2D | Tyr646 OH | 2.84 |

Local contacts between the Hb α subunit and the aromatic helix of IsdHN2 carrying the FYHYA(365–369)→YYHYF mutation are identical to those observed at the IsdHN1–α interface, showing that these contacts were successfully transplanted (Figs. 3 ▸ a, 3 ▸ b and 3 ▸ c). The arrangement of domains in the IsdH receptor and their positions on Hb α are the same as in PDB entry 4ij2, suggesting that the FYHYA(365–369)→YYHYF mutation does not disturb the orientation of the receptor on α. Electron density and anomalous signal were detected at the globin haem iron sites but not in the receptor haem pockets, suggesting that the complex is trapped in a state prior to haem transfer. A striking feature of the complex is a localized change in the conformation of the Hb α subunit F helix, which carries the haem-ligating αHis87(F8), and the FG loop, which participates in quaternary interactions in the Hb tetramer (Fig. 1 ▸ d). Features of the tertiary and quaternary structure are discussed in the following sections.

Figure 3.

Structural features of the IsdHN2N3 subunit. (a) Structure of the aromatic helix carrying the FYHYA→YYHYF mutation (blue) at the interface with Hb α (orange). An F o − F c density map contoured at 3σ (green mesh) was generated by omitting residues 362–369 before refinement. (b) Structure of the aromatic helix carrying the FYHYA→YYHYF mutation (blue) superposed with the structure of the corresponding loop from IsdHN1 with sequence YYHFF (pink; PDB entry 3szk). (c) Structure of the native aromatic helix in IsdHN2 with sequence FYHYA (green) at the interface with Hb α (PDB entry 4fc3). (d) Structure of the loop linking the IsdHLinker and IsdHN3 domains, showing OMIT electron density for the region not previously observed in PDB entry 4ij2 or structures of the isolated domains (F o − F c OMIT map contoured at 3σ, where residues 532–543 were omitted from the model prior to refinement).

3.3. Interdomain linkers of IsdH

The residues linking the three domains of the IsdHN2N3 receptor, which were absent or unstructured in the isolated domains, were not modelled in the earlier structure (PDB entry 4ij2) owing to the low data resolution. In the current structure, the polypeptide segment joining the IsdHLinker domain to IsdHN3 (residues Val531–Gln543) is clearly visible in the electron density (Fig. 3 ▸ d). Helix 3 of the IsdHLinker domain is extended by one turn, Val531–Glu535, compared with the solution NMR structure of the free IsdHLinker (Spirig et al., 2013 ▸). The side chain of Phe534 projects into a pocket between the two sheets of the IsdHN3 β-sandwich; the pocket is typically occupied by a glycerol molecule in crystal structures of the free IsdHN3 domain, for example PDB entries 2e7d (Watanabe et al., 2008 ▸) and 3qug (Moriwaki et al., 2011 ▸). Residues 536–544 adopt an extended conformation across the surface of the IsdHN3 domain and make two backbone hydrogen bonds with the edge of β-strand 4 (numbered according to homology with the immunoglobulin domain topology). In contrast, the sequence connecting IsdHN2 to the IsdHLinker domain (residues 464–472) together with an adjacent loop of IsdHN2 (residues 378–383) are not sufficiently well resolved in the electron density for unambiguous interpretation, consistent with some disorder in this region. In summary, the IsdHLinker and IsdHN3 domains pack together across a well ordered interface, suggesting that they behave as a single structural unit, whereas interdomain contacts between the IsdHLinker and the IsdHN2 domain are more limited. This conclusion is consistent with a recent NMR study of the free IsdHN2N3 receptor, which indicated that the IsdHN2 domain is able to reorient with respect to IsdHLinker–IsdHN3, making excursions from its average position of up to 10 Å (Sjodt et al., 2015 ▸).

3.4. Interactions between IsdHN2N3 and the Hb α haem pocket

Together, the IsdHN3 and IsdHLinker domains make multiple contacts surrounding the entrance to the Hb α pocket. The positioning of the IsdHN3 domain means that the haem-binding sites in Hb α and IsdHN3 are approximately coplanar. Movement of haem from Hb α to the IsdHN3 domain requires a translation of ∼12 Å through the entrance to the globin haem pocket, together with a rotation of ∼115° in the plane of the porphyrin ring (Fig. 4 ▸ a). The IsdHN3 loop containing the 310-helix makes van der Waals contacts across the CE loop and the N-terminal region of helix E of Hb α, which together form one side of the haem-pocket entrance and retain a native conformation (Fig. 4 ▸ b). On the opposite side of the haem-pocket entrance, Tyr495 and Lys499 from the IsdHLinker domain make a hydrogen bond and a salt bridge to αAsp85(F6), while the Tyr495 ring is packed against the side chain of αLeu86(F7), which adopts a non-native position (Fig. 4 ▸ b).

Figure 4.

Structural changes in the Hb α haem pocket. (a) Detail of the haem-transfer interface formed between IsdHN3 (dark blue) and α (orange, yellow); haem is bound through αHis87(F8). The expected position of the haem group post-transfer is illustrated by superposing the structure of holo IsdHN3 (PDB entry 2z6f; only the β-hairpin, the Tyr642 side chain and haem group are shown; purple). (b) Detail of (a) showing interactions at the haem-transfer interface. A region of α with non-native conformation is coloured yellow. The mutation, Y642A, is highlighted in red. His and Tyr side chains with capacity to act as ligands to the haem iron are shown. (c) Stereo diagram of the α subunit from the IsdHN2N3–metHb complex (orange). An F o − F c map generated by omitting residues 80–91 of the α F helix is shown contoured at 3σ (green). 2F o − F c electron density, contoured at 1.5σ, is also shown for the α F helix and haem group (grey). (d) The haem pocket of native Hb α, showing hydrophobic side chains in the proximal haem pocket (spheres) that contact the haem group and protect the haem-coordinating histidine, αHis87(F8), against hydration. (e) The haem pocket of Hb α in the IsdHN2N3–metHb complex, showing that the hydrophobic side chains of αLeu86(F7) and αLeu91(FG3) are displaced from their native positions. The region of α with non-native conformation in the IsdHN2N3–metHb is coloured yellow.

The β-hairpin of IsdHN2N3 carrying Ala642 (Tyr642 in the wild-type complex; Fig. 4 ▸ b) accounts for the majority of contacts with the distorted region of α (the F helix and FG corner) and forms one wall of a haem-transfer chamber that connects the haem-binding sites of both domains. Other contacts between IsdHN3 or IsdHLinker and Hb α involve regions of α with native structure; these contacts may brace the IsdHN3 domain against stable regions of α to facilitate conformational exchange of residues surrounding the haem. Structures of the free IsdHN3 domain in the apo and haem-bound states show that the Tyr642 β-hairpin also undergoes a small movement upon haem ligation (Vu et al., 2013 ▸; Moriwaki et al., 2011 ▸; Watanabe et al., 2008 ▸), suggesting that concerted changes in the structure of the IsdHN3 Tyr642 β-hairpin and the Hb α F helix/FG corner could accompany haem transfer.

We note that Isd proteins of B. anthracis lack the three-domain structure that is conserved in S. aureus IsdB/IsdH, and instead some of the isolated haem-binding domains are able to acquire haem from metHb (Ekworomadu et al., 2012 ▸; Honsa et al., 2011 ▸). Mutations on the surface of the 310-helix in the first NEAT domain of B. anthracis IsdX1, and the single NEAT domain of B. anthracis IsdX2, disrupt Hb binding or haem uptake from metHb (Ekworomadu et al., 2012 ▸; Honsa et al., 2013 ▸) and thus it is possible that these NEAT domains associate with globin chains in a similar manner to the IsdHN3 domain.

3.5. Altered structure of the Hb α haem pocket

The most striking feature of the IsdHN2N3–metHb complex is the altered structure of the α-subunit haem pocket (Fig. 4 ▸). These tertiary-structural changes are described in comparison with the 2.0 Å resolution structure of R-state human metHb (PDB entry 3p5q; Yi et al., 2011 ▸). In IsdHN2N3–metHb, the largest perturbation from the native Hb α structure occurs in helix F and the FG corner (residues αLeu86–αArg93; Figs. 1 ▸ d and 4 ▸). The final turn of the F helix (αLeu86–αHis89) is unwound, resulting in a different set of intramolecular contacts for these residues. The side chain of αHis89(FG1) is displaced by ∼13 Å from a position facing away from the haem group on the outside of helix F to an inwards-facing position, where it forms a hydrogen bond to the propionate at the β-pyrrolic position 6 (Fischer & Orth, 1934 ▸) of the haem group (Figs. 1d ▸ and 4 ▸). Despite these changes, αHis87(F8) retains coordination of the haem iron. The hydrophobic side chains of αLeu86(F7) and αLeu91(FG3), which in the native structure sit under the porphyrin meso-position γ and pyrrole ring III, respectively (Fig. 4 ▸ d), are rotated outwards (Fig. 4 ▸ e). The positions vacated by Leu86 and Leu91 are partially filled by the αHis87(F8) main chain and αAla88(F9). Other side chains in the haem pocket retain their native positions (r.m.s.d. of 0.32 Å over 105 Cα atom pairs with PDB entry 3p5q, excluding residues αVal73–αArg92).

The tertiary-structural changes seen in Hb α suggest three factors that might contribute to haem release. Firstly, disturbance of side-chain packing in the proximal haem pocket could lead to an increased probability of water entry. Water promotes autooxidation (Brantley et al., 1993 ▸) and competes with the proximal His as a ligand for iron(III) haem, leading to accelerated rates of haem loss (Liong et al., 2001 ▸). To prevent this, the α and β subunits share a common feature of six bulky hydrophobic side chains that form a hydrophobic ‘cage’ shielding the iron–His(F8) bond from water; in α these residues are αLeu83(F4), αLeu86(F7), αLeu91(FG3), αVal93(FG5), αPhe98(G5) and αLeu136(H19) (Fig. 4 ▸ d). Movement of the αLeu86(F7) and αLeu91(FG3) side chains out of the haem pocket may have a significant effect on haem loss through permitting the ingress of water molecules (Fig. 4 ▸ e). Secondly, unwinding of helix F may result in loss of a physical barrier to haem movement; the α and β haem groups are embedded deep between the E and F helices and make van der Waals contacts over an extensive surface. Consequently, haem binding and dissociation is thought to occur in conjunction with local protein folding/unfolding. In apo myoglobin the F helix and the adjacent EF and FG corners undergo local unfolding on an approximately microsecond time scale to allow haem entry (Hughson et al., 1990 ▸; Cocco & Lecomte, 1990 ▸; Lecomte & Cocco, 1990 ▸; Eliezer & Wright, 1996 ▸), and similar unfolding is presumably required during haem loss. In the case of Hb, αβ dimers lacking one haem group have reduced α-helical content, suggesting that haem binding/extraction involves localized folding/unfolding (Kawamura-Konishi et al., 1992 ▸). In the IsdHN2N3–metHb crystal, the α F helix, although not disordered, adopts some nonregular secondary structure, with consequent loss of the cooperative hydrogen-bonding network that confers comparative rigidity to the native α-helical structure. Thirdly, alternative His/Tyr ligands may compete with αHis87(F8) for haem binding. A number of side chains with haem-binding capability lie at positions between the haem-coordinating side chains of Hb α and the IsdHN3 domain, namely αHis58(E7), αHis89(FG1), αHis45(CE3) and IsdH Tyr646 (Fig. 4 ▸ b). The position of αHis89 is particularly intriguing, as this residue has undergone the largest displacement from its native location and sits with its Nɛ2 atom ∼4.5 Å away from Nɛ2 of αHis45, leading us to speculate that these two side chains could potentially form a hexacoordinate haem as an intermediate during haem transfer. A potential role for intermediate haem ligands needs to be investigated in future studies of haem transfer.

Finally, it is not clear how contacts between IsdH and Hb α lead to local conformational changes in the globin, but we speculate that the S. aureus bacterium is exploiting an intrinsic feature of the F helix that makes it susceptible to strain. A similar effect has been observed during interaction of α with the chaperone α-Hb stabilizing protein (AHSP): AHSP binding to α at a distant site induces a localized disturbance in the F helix that precedes a larger conformational rearrangement of α (Dickson et al., 2013 ▸).

3.6. Altered Hb quaternary structure

Using mass spectrometry, Spirig and coworkers have shown that IsdHN2N3 induces a shift from tetrameric to dimeric Hb species (Spirig et al., 2013 ▸). Dissociation of Hb tetramers into αβ dimers accelerates autooxidation (Zhang et al., 1991 ▸) and haem dissociation from Hb chains (Hargrove et al., 1997 ▸), suggesting that IsdH may exploit this mechanism to promote haem release. Following erythrocyte lysis in vivo, αβ dimers are formed naturally by the dilution of Hb tetramers and are scavenged by the host serum protein haptoglobin. IsdH can bind haptoglobin–Hb complexes (Visai et al., 2009 ▸; Dryla et al., 2003 ▸, 2007 ▸; Pilpa et al., 2009 ▸), although haem uptake from this complex has not been demonstrated. However, certain conditions, such as when the haptoglobin capacity is exceeded, may bring S. aureus into contact with the Hb tetramer state and the influence of IsdH on Hb quaternary structure is therefore of interest.

In native adult human Hb the α1β2 interface undergoes a reorganization that is coupled to oxygen binding, involving a ∼15° rotation and ∼1 Å translation of the α2β2 dimer relative to α1β1 (Baldwin & Chothia, 1979 ▸) that brings the two β subunits closer together during the T→R transition (Muirhead & Perutz, 1963 ▸). In addition to the R structure, fully liganded human Hb has been crystallized in a number of other quaternary structures, including the R2 (Silva et al., 1992 ▸), RR2 and R3 states (Safo & Abraham, 2005 ▸). To determine the similarity of IsdHN2N3–metHb to the T, R, R2, RR2 and R3 quaternary structures, we superposed α1β1 dimers over a region of invariant structure (the ‘BGH’ frame established by Baldwin & Chothia, 1979 ▸) and determined the r.m.s.d. for the non-aligned α2β2 dimer (Table 3 ▸). We then determined the rotation/translation required to align the α2β2 dimers for each of the T, R, R2, RR2 and R3 structures (Table 3 ▸). These comparisons showed that of these five quaternary structures, IsdHN2N3–metHb was most similar to the T state (α2β2 r.m.s.d. of 3.9 Å; α2β2 rotation/translation of 9.2°/0.7 Å); however, IsdHN2N3–metHb was clearly different from all of the test structures. The iron–iron distance between β haems of IsdHN2N3–metHb (Table 4 ▸; 38.3 Å) also indicated closer similarity to the T state (39.5 Å) than to the R state (34.9 Å). Using the same criteria (Tables 3 ▸ and 4 ▸), two other Hb structures in the PDB show much greater levels of similarity to IsdHN2N3–metHb, namely a human Hb variant comprising embryonic ζ chain and β chain carrying the sickle-cell mutation (βS) crystallized in the fully CO-ligated form (Safo et al., 2013 ▸) and metHb from cat (Felis silvestris catus; Balasubramanian et al., 2014 ▸). Both the Hb ζ2β2 S and cat metHb structures exhibit an unusual T state-like quaternary structure with several local tertiary and quaternary features characteristic of the R state (Safo et al., 2013 ▸; Balasubramanian et al., 2014 ▸).

Table 3. Quaternary-structure comparisons between PDB entry 4xs0 and reference Hbs.

| Hb structure† | PDB code | α1β1 r.m.s.d. (Å), all atom pairs (Cα atom pairs)‡ | α2β2 r.m.s.d (Å), all atom pairs (Cα atom pairs)‡ | Rotation§ (°) | Translation§ (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T state | 2dn2 | 1.7 (1.0) | 4.1 (3.9) | 9.2 | 0.7 |

| R state | 2dn1 | 1.9 (1.1) | 7.4 (7.2) | 17.0 | 4.2 |

| R2 state | 1bbb | 2.3 (1.4) | 11.5 (11.4) | 27.9 | 6.0 |

| RR2 state | 1mko | 2.1 (1.4) | 9.7 (9.5) | 22.1 | 6.2 |

| R3 state | 1yzi | 1.9 (1.3) | 9.0 (8.9) | 20.1 | 4.4 |

| Human ζ2β2 S | 3w4u | 1.5 (1.0) | 1.8 (1.4) | 3.5 | 0.6 |

| Cat α2β2 | 3gqp | 1.5 (1.0) | 1.5 (1.0) | 1.1 | 0.1 |

The T-state and R-state reference structures are human deoxy-Hb and HbCO from Park et al. (2006 ▸), respectively, the R2 structure is from Silva et al. (1992 ▸), the RR2 and R3 structures are from Safo & Abraham (2005 ▸), the human variant Hb comprising ζHb and βS (carrying the sickle-cell mutation) is from Safo et al. (2013 ▸) and the low-affinity Hb from F. silvestris catus is from Balasubramanian et al. (2014 ▸).

Comparison with the 4xs0 structure after superposing α1β1 dimers using residues of the BGH frame.

Rotation/translation needed to align α2β2 of the test structure with α2β2 of the 4xs0 structure after first superposing the α1β1 dimers according to the BGH frame.

Table 4. Iron–iron distances (Å).

The presence of specific side-chain interactions that characterize the T and R quaternary states (Baldwin & Chothia, 1979 ▸), and the functional importance of C-terminal salt bridges of the T state (Perutz, 1970 ▸), were established in early seminal works and provide a useful and robust definition of quaternary structure (Park et al., 2006 ▸). For example, the hydrogen bonds that are characteristic of the R state are largely preserved in the R2, RR2 and R3 structures (Table 5 ▸), despite relative rotations of the αβ dimers of up to 12°. This pattern is consistent with NMR measurements made in solution, which indicate that CO-ligated Hb populates multiple low-energy states that average to a structure intermediate between the R and R2 conformations (Lukin et al., 2003 ▸), and a sliding motion at the αβ dimer interface that does not require substantial changes to subunit contacts has been proposed (Mueser et al., 2000 ▸). The α1β2 interface in IsdHN2N3–metHb displays a number of hydrogen bonds and C-terminal salt bridges that are characteristic of the quaternary T state; however, the intrasubunit hydrogen bond between βTrp37 and βAsn102 is a tertiary R-state feature and the loss of a salt bridge to the terminal carboxyl of αArg141 is atypical of a T-state structure.

Table 5. Hydrogen-bond and salt-bridge interactions characteristic of Hb quaternary states.

Values in parentheses are for the pseudo-symmetrical contact where there are two αβ dimers in the crystallographic asymmetric unit.

| Residue 1 | Residue 2 | T deoxyHb (2dn2) | T aquometHb (1hgb) | R HbO2 (2dn1) | R aquometHb (3p5q) | R2 HbCO (1bbb) | RR2 HbCO (1mko) | R3 HbCO (1yzi) | ζ2β2 S HbCO (3w4u) | Cat aquometHb (3gqp) | IsdHN2N3–aquometHb (4xs0) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen bonds at the α1β2 interface | |||||||||||

| β2Asp99 OD1/2 | α1Tyr42 OH | 2.5 (2.5) | 2.5 (2.5) | — | — | — | — | — | 2.4 (2.4) | 2.8 (2.5) | 2.5 |

| β2Asp99 OD1/2 | α1Asn97 ND2 | 2.8 (2.8) | 3.9 (3.1) | — | — | — | — | — | 2.9 (2.8) | 2.8 (2.7) | 2.7 |

| α1Asp94 OD1/2 | β2Trp37 NE1 | 2.9 (2.8) | 3.2 (3.1) | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.8 (3.8) | 3.6 (3.4) | 3.5 | — | — | — |

| α1Asp94 OD1/2 | β2Asn102 ND2 | — | — | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.7 (2.8) | 2.8 (2.8) | 2.8 | — | — | — |

| β2Trp37 NE1 | β2Asn102 OD1 | — | — | 2.9 | 3.0 | 3.0 (3.0) | 3.1 (3.1) | 3.3 | 3.1 (3.2) | (2.9) | 3.5 |

| C-terminal salt bridges | |||||||||||

| α1Arg141 NH1/2 | α2Asp126 OD2 | 2.8 (2.7) | 2.5 (2.4) | — | Disordered | — | — | — | — | (2.9) | 2.9 |

| α1Arg141 OXT | α2Lys127 NZ | 2.8 (2.8) | 2.6 (2.8) | — | Disordered | — | — | — | — | 2.9 | — |

| β2His146 NE2 | β2Asp94 OD(1) | 2.6 (2.8) | 2.8 (2.6) | — | — | — | — | — | 3.0 (2.6) | 2.9 (3.0) | 3.6 |

| β2His146 OXT | α1Lys40 NZ | 2.8 (2.6) | 2.4 (2.7) | — | — | — | — | — | 2.9 (2.7) | 2.6 (2.5) | 2.7 |

In addition to electrostatic interactions, steric interactions at the αβ dimer interface also characterize the T and R states (Baldwin & Chothia, 1979 ▸). The most extensive area of contact is the α1β2 interface, which includes interactions between helix C of the α1 subunit and the FG corner of the β2 subunit (the ‘switch’ region) and between the FG corner of α1 and helix C of β2 (the flexible ‘joint’) (Perutz et al., 1998 ▸). In the T→R quaternary transition the switch moves between two positions characterized by different inter-chain contacts, whereas the joint maintains similar side-chain packing in the T and R states. In the IsdHN2N3–metHb crystal the switch region is essentially identical to that of the T state (Fig. 5 ▸ a). In contrast, the joint region in the IsdHN2N3–metHb structure has undergone a significant rearrangement (Fig. 5 ▸ b). Thus, in normal R and T states the side chain of βTrp37 is packed against αAsp94 and αPro95 (Fig. 5 ▸ b; red and blue shading). In IsdHN2N3–metHb the side chain of αArg92 projects between βTrp37 and αPro95, disrupting the joint region, and makes salt-bridge interactions with the side chain of αAsp94 and the carboxyl-terminus of the α subunit. Interestingly, this highly unusual structure of the joint region is also observed in HbCO ζ2β2 S and cat metHb, although in the former it is the side chain of αArg141, rather than αArg92, that projects between βTrp37 and αPro95 (Fig. 5 ▸ c).

Figure 5.

Hb quaternary features of the IsdHN2N3–metHb complex (PDB entry 4xs0; yellow), O2-ligated R-state Hb (PDB entry 2dn1; red), deoxy T-state Hb (PDB entry 2dn2; blue), CO-ligated ζ2β2 S (PDB entry 3w4u; cyan) and cat metHb (PDB entry 3gqp; green). (a) Detail of the switch region of the α1β2 interface, showing the relative positions of the α1 subunit helix C and the β2 subunit FG corner. (b) Detail of the joint region of the α1β2 interface, showing the relative positions of the β2 helix C and the α1 FG corner. In the R and T states the side chain of β2Trp37 contacts the side chain of α1Pro95. In the IsdHN2N3–metHb complex, the side chain of α1Arg92 separates β2Trp37 and α1Pro95 and makes salt bridges with α1Asp94 and the terminal carboxyl of the α1 subunit (van der Waals contacts are represented by dashed green lines; hydrogen-bonding interactions are represented by dashed magenta lines). (c) Comparison of the joint region of the α1β2 interface from IsdHN2N3–metHb, ζ2β2 S and cat metHb.

The changes seen at the joint contact provide an explanation for how R-like tertiary features are accommodated in the T-like quaternary structure. In native human Hb, the tertiary-structural changes in the globin subunits associated with ligand binding cause the FG corners of the α1 and β1 subunits to move approximately 2.5 Å closer together in the T→R transition (Perutz et al., 1998 ▸), and this is accommodated by movement of the β1 FG corner relative to the α1 helix C at the switch region (Fig. 6 ▸; red arrows). In the IsdHN2N3–metHb structure the distance between the α1 and β1 FG corners is characteristic of the liganded R state (Table 6 ▸) and this is accompanied by opening of the joint region (Fig. 6 ▸; yellow arrows), whilst the switch region maintains the canonical T structure. The relative positions of switch and joint secondary-structure elements are essentially the same in IsdHN2N3–metHb, cat metHb and HbCO ζ2β2 S (Table 6 ▸). In the case of IsdHN2N3–metHb, the cause of the altered interactions seems likely to be the altered conformation of the α F helix and FG corner induced by Hb receptor binding. Cat Hb has low oxygen affinity, even in the absence of 2,3-diphosphoglycerate (DPG; Balasubramanian et al., 2014 ▸), whereas Hb ζ2β2 S is a high-affinity variant (Safo et al., 2013 ▸); thus, the contribution of the T-like quaternary structure to oxygen affinity is not clear in the background of amino-acid sequence differences between Hb α, Hb ζ and cat Hb. IsdHN2N3 induces a shift from tetrameric to dimeric Hb species (Spirig et al., 2013 ▸), and it is possible that the altered αβ dimer interface observed in the crystal structure is the underlying mechanism.

Figure 6.

Schematic of one half of the symmetrical α1β2 interface, showing only the Cα atoms of four residues to represent the switch and joint contacts, in the IsdHN2N3–metHb complex (PDB entry 4xs0; yellow), O2-ligated R-state Hb (PDB entry 2dn1; red) and deoxy T-state Hb (PDB entry 2dn2; blue), prepared by superposition of the α1β1 dimers in the BGH frame (Baldwin & Chothia, 1979 ▸). Dashed lines indicate approximately equal interatomic distances in the three structures (Table 6 ▸). Arrowheads indicate displacement of R-state atoms (red) or IsdHN2N3–metHb complex atoms (yellow) relative to the T-state structure (blue).

Table 6. Distances between Cα atoms of selected residues across the switch and joint regions of the αβ dimer interface.

Values in parentheses are for the pseudo-symmetrical contact where there are two αβ dimers in the crystallographic asymmetric unit.

| Residue 1 | Residue 2 | T deoxyHb (2dn2) | R HbO2 (2dn1) | ζ2β2 S HbCO (3w4u) | Cat aquometHb (3gqp) | IsdHN2N3–aquometHb (4xs0) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α1Pro95(FG7) | β1Pro100(FG7) | 21.6 (21.9) | 18.9 | 19.7 (19.8) | 18.6 (19.2) | 19.1 |

| α1Pro95(FG7) | β2Trp37(C3) | 9.5 (9.4) | 8.4 | 12.9 (13.1) | 13.8 (13.0) | 13.2 |

| β1Pro100(FG7) | α2Thr38(C3)† | 7.1 (7.2) | 10.0 | 7.0 (7.0) | 7.4 (7.0) | 6.9 |

| α2Thr38(C3)† | β2Trp37(C3) | 29.0 (29.0) | 29.1 | 29.9 (29.8) | 28.9 (29.1) | 29.2 |

Replaced by α2Gln38(C3) in PDB entry 3w4u.

In conclusion, the IsdHN2N3–Hb complex shows substantial deformation of the αHb haem pocket that is predicted to weaken the globin–haem interaction and disrupt the allosteric α1β2 interface, potentially leading to weakening of the Hb quaternary structure.

Supplementary Material

PDB reference: IsdH, complex with Hb, 4xs0

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr David Aragao and Dr Tom Caradoc-Davies at the MX beamlines at the Australian Synchrotron for help with data collection. This work was supported in part by the University of Tasmania (to DAG).

References

- Aranda, R., Worley, C. E., Liu, M., Bitto, E., Cates, M. S., Olson, J. S., Lei, B. & Phillips, G. N. (2007). J. Mol. Biol. 374, 374–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Balasubramanian, M., Sathya Moorthy, P., Neelagandan, K., Ramadoss, R., Kolatkar, P. R. & Ponnuswamy, M. N. (2014). Acta Cryst. D70, 1898–1906. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Baldwin, J. & Chothia, C. (1979). J. Mol. Biol. 129, 175–220. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Brantley, R. E. Jr, Smerdon, S. J., Wilkinson, A. J., Singleton, E. W. & Olson, J. S. (1993). J. Biol. Chem. 268, 6995–7010. [PubMed]

- Chen, V. B., Arendall, W. B., Headd, J. J., Keedy, D. A., Immormino, R. M., Kapral, G. J., Murray, L. W., Richardson, J. S. & Richardson, D. C. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 12–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cocco, M. J. & Lecomte, J. T. (1990). Biochemistry, 29, 11067–11072. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dickson, C. F., Kumar, K. K., Jacques, D. A., Malmirchegini, G. R., Spirig, T., Mackay, J. P., Clubb, R. T., Guss, J. M. & Gell, D. A. (2014). J. Biol. Chem. 289, 6728–6738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dickson, C. F., Rich, A. M., D’Avigdor, W. M., Collins, D. A., Lowry, J. A., Mollan, T. L., Khandros, E., Olson, J. S., Weiss, M. J., Mackay, J. P., Lay, P. A. & Gell, D. A. (2013). J. Biol. Chem. 288, 19986–20001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dryla, A., Gelbmann, D., Von Gabain, A. & Nagy, E. (2003). Mol. Microbiol. 49, 37–53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dryla, A., Hoffmann, B., Gelbmann, D., Giefing, C., Hanner, M., Meinke, A., Anderson, A. S., Koppensteiner, W., Konrat, R., von Gabain, A. & Nagy, E. (2007). J. Bacteriol. 189, 254–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dukic, V. M., Lauderdale, D. S., Wilder, J., Daum, R. S. & David, M. Z. (2013). PLoS One, 8, e52722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Eaton, W. A. & Hofrichter, J. (1981). Methods Enzymol. 76, 175–261. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ekworomadu, M. T., Poor, C. B., Owens, C. P., Balderas, M. A., Fabian, M., Olson, J. S., Murphy, F., Bakkalbasi, E., Balkabasi, E., Honsa, E. S., He, C., Goulding, C. W. & Maresso, A. W. (2012). PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Eliezer, D. & Wright, P. E. (1996). J. Mol. Biol. 263, 531–538. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. (2004). Acta Cryst. D60, 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Engh, R. A. & Huber, R. (1991). Acta Cryst. A47, 392–400.

- Evans, P. R. & Murshudov, G. N. (2013). Acta Cryst. D69, 1204–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fischer, H. & Orth, H. (1934). Die Chemie des Pyrrols, Vol. 1. Leipzig: Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft.

- Gaudin, C. F. M., Grigg, J. C., Arrieta, A. L. & Murphy, M. E. P. (2011). Biochemistry, 50, 5443–5452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gell, D., Kong, Y., Eaton, S. A., Weiss, M. J. & Mackay, J. P. (2002). J. Biol. Chem. 277, 40602–40609. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Grigg, J. C., Mao, C. X. & Murphy, M. E. P. (2011). J. Mol. Biol. 413, 684–698. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Grigg, J. C., Ukpabi, G., Gaudin, C. F. & Murphy, M. E. P. (2010). J. Inorg. Biochem. 26, 26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Grigg, J. C., Vermeiren, C. L., Heinrichs, D. E. & Murphy, M. E. P. (2007a). J. Biol. Chem. 282, 28815–28822. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Grigg, J. C., Vermeiren, C. L., Heinrichs, D. E. & Murphy, M. E. P. (2007b). Mol. Microbiol. 63, 139–149. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hargrove, M. S., Barrick, D. & Olson, J. S. (1996). Biochemistry, 35, 11293–11299. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hargrove, M. S., Whitaker, T., Olson, J. S., Vali, R. J. & Mathews, A. J. (1997). J. Biol. Chem. 272, 17385–17389. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hayward, S. & Berendsen, H. J. (1998). Proteins, 30, 144–154. [PubMed]

- Honsa, E. S., Fabian, M., Cardenas, A. M., Olson, J. S. & Maresso, A. W. (2011). J. Biol. Chem. 286, 33652–33660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Honsa, E. S., Owens, C. P., Goulding, C. W. & Maresso, A. W. (2013). J. Biol. Chem. 288, 8479–8490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hughson, F. M., Wright, P. E. & Baldwin, R. L. (1990). Science, 249, 1544–1548. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Karplus, P. A. & Diederichs, K. (2012). Science, 336, 1030–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kawamura-Konishi, Y., Chiba, K., Kihara, H. & Suzuki, H. (1992). Eur. Biophys. J. 21, 85–92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kluytmans, J., van Belkum, A. & Verbrugh, H. (1997). Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 10, 505–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Krishna Kumar, K., Jacques, D. A., Pishchany, G., Caradoc-Davies, T., Spirig, T., Malmirchegini, G. R., Langley, D. B., Dickson, C. F., Mackay, J. P., Clubb, R. T., Skaar, E. P., Guss, J. M. & Gell, D. A. (2011). J. Biol. Chem. 286, 38439–38447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lecomte, J. T. & Cocco, M. J. (1990). Biochemistry, 29, 11057–11067. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Leslie, A. G. W. & Powell, H. (2007). Evolving Methods for Macromolecular Crystallography, edited by R. J. Read & J. L. Sussman, pp. 41–51. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Liong, E. C., Dou, Y., Scott, E. E., Olson, J. S. & Phillips, G. N. Jr (2001). J. Biol. Chem. 276, 9093–9100. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Liu, H. & Naismith, J. H. (2008). BMC Biotechnol. 8, 91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Liu, M., Tanaka, W. N., Zhu, H., Xie, G., Dooley, D. M. & Lei, B. (2008). J. Biol. Chem. 283, 6668–6676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lukin, J. A., Kontaxis, G., Simplaceanu, V., Yuan, Y., Bax, A. & Ho, C. (2003). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 100, 517–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Malmirchegini, G. R., Sjodt, M., Shnitkind, S., Sawaya, M. R., Rosinski, J., Newton, S. M., Klebba, P. E. & Clubb, R. T. (2014). J. Biol. Chem. 289, 34886–34899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mazmanian, S. K., Skaar, E. P., Gaspar, A. H., Humayun, M., Gornicki, P., Jelenska, J., Joachmiak, A., Missiakas, D. M. & Schneewind, O. (2003). Science, 299, 906–909. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mazmanian, S. K., Ton-That, H., Su, K. & Schneewind, O. (2002). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 99, 2293–2298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McCoy, A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Adams, P. D., Winn, M. D., Storoni, L. C. & Read, R. J. (2007). J. Appl. Cryst. 40, 658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Moriwaki, Y., Caaveiro, J. M., Tanaka, Y., Tsutsumi, H., Hamachi, I. & Tsumoto, K. (2011). Biochemistry, 50, 7311–7320. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Morrissey, J. A., Cockayne, A., Hammacott, J., Bishop, K., Denman-Johnson, A., Hill, P. J. & Williams, P. (2002). Infect. Immun. 70, 2399–2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mueser, T. C., Rogers, P. H. & Arnone, A. (2000). Biochemistry, 39, 15353–15364. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Muirhead, H. & Perutz, M. F. (1963). Nature (London), 199, 633–638. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Murshudov, G. N., Skubák, P., Lebedev, A. A., Pannu, N. S., Steiner, R. A., Nicholls, R. A., Winn, M. D., Long, F. & Vagin, A. A. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 355–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Muryoi, N., Tiedemann, M. T., Pluym, M., Cheung, J., Heinrichs, D. E. & Stillman, M. J. (2008). J. Biol. Chem. 283, 28125–28136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nairz, M., Schroll, A., Sonnweber, T. & Weiss, G. (2010). Cell. Microbiol. 12, 1691–1702. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Park, S. Y., Yokoyama, T., Shibayama, N., Shiro, Y. & Tame, J. R. H. (2006). J. Mol. Biol. 360, 690–701. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Perutz, M. F. (1970). Nature (London), 228, 726–734. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Perutz, M. F., Rossmann, M. G., Cullis, A. F., Muirhead, H., Will, G. & North, A. C. T. (1960). Nature (London), 185, 416–422. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Perutz, M. F., Wilkinson, A. J., Paoli, M. & Dodson, G. G. (1998). Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 27, 1–34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pilpa, R. M., Fadeev, E. A., Villareal, V. A., Wong, M. L., Phillips, M. & Clubb, R. T. (2006). J. Mol. Biol. 360, 435–447. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pilpa, R. M., Robson, S. A., Villareal, V. A., Wong, M. L., Phillips, M. & Clubb, R. T. (2009). J. Biol. Chem. 284, 1166–1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pishchany, G., McCoy, A. L., Torres, V. J., Krause, J. C., Crowe, J. E. Jr, Fabry, M. E. & Skaar, E. P. (2010). Cell Host Microbe, 8, 544–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pluym, M., Muryoi, N., Heinrichs, D. E. & Stillman, M. J. (2008). J. Inorg. Biochem. 102, 480–488. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pluym, M., Vermeiren, C. L., Mack, J., Heinrichs, D. E. & Stillman, M. J. (2007). Biochemistry, 46, 12777–12787. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Safo, M. K. & Abraham, D. J. (2005). Biochemistry, 44, 8347–8359. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Safo, M. K., Ko, T.-P., Abdulmalik, O., He, Z., Wang, A. H.-J., Schreiter, E. R. & Russell, J. E. (2013). Acta Cryst. D69, 2061–2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sharp, K. H., Schneider, S., Cockayne, A. & Paoli, M. (2007). J. Biol. Chem. 282, 10625–10631. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Silva, M. M., Rogers, P. H. & Arnone, A. (1992). J. Biol. Chem. 267, 17248–17256. [PubMed]

- Sjodt, M., Macdonald, R., Spirig, T., Chan, A. H., Dickson, C. F., Fabian, M., Olson, J. S., Gell, D. A. & Clubb, R. T. (2015). J. Mol. Biol., doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Spirig, T., Malmirchegini, G. R., Zhang, J., Robson, S. A., Sjodt, M., Liu, M., Krishna Kumar, K., Dickson, C. F., Gell, D. A., Lei, B., Loo, J. A. & Clubb, R. T. (2013). J. Biol. Chem. 288, 1065–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tiedemann, M. T., Heinrichs, D. E. & Stillman, M. J. (2012). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 16578–16585. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tiedemann, M. T. & Stillman, M. J. (2012). J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 17, 995–1007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Torres, V. J., Pishchany, G., Humayun, M., Schneewind, O. & Skaar, E. P. (2006). J. Bacteriol. 188, 8421–8429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Vermeiren, C. L., Pluym, M., Mack, J., Heinrichs, D. E. & Stillman, M. J. (2006). Biochemistry, 45, 12867–12875. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Villareal, V. A., Pilpa, R. M., Robson, S. A., Fadeev, E. A. & Clubb, R. T. (2008). J. Biol. Chem. 283, 31591–31600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Visai, L., Yanagisawa, N., Josefsson, E., Tarkowski, A., Pezzali, I., Rooijakkers, S. H., Foster, T. J. & Speziale, P. (2009). Microbiology, 155, 667–679. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Vu, N. T., Moriwaki, Y., Caaveiro, J. M., Terada, T., Tsutsumi, H., Hamachi, I., Shimizu, K. & Tsumoto, K. (2013). Protein Sci. 22, 942–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, M., Tanaka, Y., Suenaga, A., Kuroda, M., Yao, M., Watanabe, N., Arisaka, F., Ohta, T., Tanaka, I. & Tsumoto, K. (2008). J. Biol. Chem. 283, 28649–28659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wu, R., Skaar, E. P., Zhang, R., Joachimiak, G., Gornicki, P., Schneewind, O. & Joachimiak, A. (2005). J. Biol. Chem. 280, 2840–2846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yi, J., Thomas, L. M. & Richter-Addo, G. B. (2011). Acta Cryst. F67, 647–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L., Levy, A. & Rifkind, J. M. (1991). J. Biol. Chem. 266, 24698–24701. [PubMed]

- Zhu, H., Xie, G., Liu, M., Olson, J. S., Fabian, M., Dooley, D. M. & Lei, B. (2008). J. Biol. Chem. 283, 18450–18460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PDB reference: IsdH, complex with Hb, 4xs0