Abstract

Electrophilic fluorophosphonium triflates bearing pyridyl (3[OTf]) or imidazolyl (4[OTf])‐substituents act as intramolecular frustrated Lewis pairs (FLPs) and reversibly form 1 : 1 adducts with CO2 (5 + and 6 +). An unusual and labile spirocyclic tetrahedral intermediate (7 2+) is observed in CO2‐pressurized (0.5–2.0 bar) solutions of cation 4 + at low temperatures, as demonstrated by variable‐temperature NMR studies, which were confirmed crystallographically. In addition, cations 3 + and 4 + actively bind carbonyls, nitriles and acetylenes by 1,3‐dipolar cycloaddition, as shown by selected examples.

Keywords: carbon dioxide, frustrated Lewis pairs, fluorophosphonium cations, small-molecule activation

Extending the FLP library: Electrophilic fluorophosphonium triflates bearing pyridyl or imidazolyl substituents act as intramolecular N/P frustrated Lewis pairs that are capable of small molecule activation, that is, reversible CO2 sequestration and binding of carbonyls, nitriles and acetylenes.

The selective, reversible binding of carbon dioxide (CO2) and its transformation into value‐added chemicals and materials is a challenge of today and success would significantly contribute to decline CO2 accumulation in the atmosphere. [1] The chemistry of CO2 binding and transformation receives tremendous attention as it is regarded as an important heat‐trapping (greenhouse) gas [2] but at the same time considered as readily available, abundant, nontoxic, and renewable C1 synthon in synthesis. [3] In this context, generous efforts continue to be devoted to the development of efficient physical or chemical CO2 activation approaches.[ 1a , 4 ] A key‐step in the capture‐and‐release strategies and catalytic conversion, however, is a reversible binding of the CO2 molecule which needs to be enabled by low‐energy and readily‐cleavable bonds. [5] Thus, a variety of organic carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus based Lewis bases were developed that are capable of forming adducts with the CO2 molecule. [6] Notably, a variety of frustrated Lewis pairs (FLPs) have been investigated towards CO2 sequestration including inter‐ (I, II) [7] and intramolecular (III,IV) [8] FLPs derived from different combinations of electrophiles (e. g., borane‐, aluminum‐, or silylium‐based) and nucleophiles (e. g., phosphanes, carbenes, or amines; Scheme 1). However, the key step in a capture‐and‐release application for the conversion of CO2 [1] is usually hampered by the fact that the majority of FLPs form stable adducts with CO2.[ 7a , 7b , 8 ] Efforts towards binding of CO2 by highly Lewis acidic amidophosphoranes were reported by the Stephan group (Scheme 1, V). [9] Although phosphonium cations have been extensively studied for their electrophilic properties, their application as Lewis acid in FLP chemistry is scarcely investigated so far. In thought of using fluorophosphonium cations in FLP chemistry, where in contrast to known systems the P atom is the Lewis acidic site, two different strategies are feasible: either the addition of a Lewis base to the fluorophosphonium salt or designing a fluorophosphonium derivative with an intramolecular Lewis basic site.

Scheme 1.

Selected examples of stable CO2 adducts of inter‐ and intramolecular FLP systems (I–V) and CO2 adducts 5 +, 6 + and 7 2+ derived from bifunctional fluorophosphonium compounds (this work).

Herein, we present the synthesis of pyridyl‐ and imidazolyl‐substituted fluorophosphonium triflate salts and their application as intramolecular N/P FLP systems. Both compounds readily form labile adducts with CO2 and bind carbonyls, nitriles and acetylenes by 1,3‐dipolar cycloaddition shown by selected examples.

To illustrate our approach, we first reacted fluorophosphonium salt 1[OTf] [10] as a very strong Lewis acid in combination with pyridine as a Lewis base and p‐tolylaldehyde in CH2Cl2 (Scheme 2). [10] The formation of adduct 2 + is indicated by multinuclear NMR spectroscopy and the 31P NMR spectrum displays a doublet resonance at δ(P)=−53.2 ppm (1 J PF=644 Hz) being well in the range for penta‐coordinate P atoms. X‐ray analysis of 2[OTf] confirms that the Lewis acidic P atom of the fluorophosphonium cation and Lewis basic N atom of the pyridine act cooperatively acts as an intermolecular FLP system activating the carbonyl group of the aldehyde (Figure 1). The corresponding P1−O1 and C1−N1 distances are 1.7038(10) Å and 1.5206(17) Å, respectively. The C1−O1 distance of 1.3974(16) Å is about 0.2 Å longer compared to the C=O double bond in free aldehydes. [11] However, the application of this intermolecular FLP system is limited as we observed the decomposition of 1[OTf] in the presence of pyridine without a suitable substrate.

Scheme 2.

Adduct formation of 2[OTf] from the reaction of 1[OTf] with pyridine and p‐tolylaldehyde; i) pyridine (1 equiv.), p‐tolCHO (1 equiv.), CH2Cl2, RT, 4 h.

Figure 1.

Molecular structure of 2[OTf] ⋅ CH2Cl2 (hydrogen atoms, CH2Cl2, and non‐coordinating anions are omitted for clarity, ellipsoids are set at 50 % probability); Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°): P1−O1 1.7038(10), O1−C1 1.3974(16), C1−N1 1.5206(17).

We therefore targeted the synthesis of bifunctional fluorophosphonium salts such as 3[OTf] and 4[OTf] which contain a pyridyl‐ or imidazolyl‐substituent, respectively. The synthesis follows our recently reported one‐pot procedure, where N‐fluorobenzenesulfonimide (NFSI) is added to the corresponding phosphane (C6F5)2PR (R=imidazolyl, pyridyl), followed by the addition of MeOTf (Scheme 3). [10] Triflate salts 3, 4[OTf] are isolated as colorless, air‐ and moisture‐sensitive salts in very good yields of >88 %. [12] We started to investigate the cooperative properties of these salts by pressurizing degassed CD2Cl2 solutions with CO2 (2 bar). The corresponding 31P and 19F NMR spectra of the solution containing 3[OTf] reveal no interaction or reaction at ambient temperature indicated by the resonances for cation 3 + (δ(31P)=54.8 ppm, δ(19F)=−114.0 ppm, 1 J PF=996 Hz) in the spectra. However, a VT NMR investigation disclosed the reversible and temperature‐dependent binding of CO2 by 3[OTf] (Figure 2, left).

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of fluorophosphonium triflate salts 3[OTf] and 4[OTf]; i) +NFSI (1 equiv.), PhF, RT, 16 h; ii) +MeOTf (1 equiv.), RT, 4 h, −MeNSI; NSI−=[N(SO2Ph)2]−.

Figure 2.

Equilibrium reaction of 3[OTf] and 4[OTf] with CO2 (top); variable‐temperature 31P NMR spectra of CO2 with 3[OTf] (bottom left, 2 bar in CD2Cl2) and 4[OTf] (bottom right, 1.5 bar in CD3NO2). Asterisks indicate small amounts of unidentified compounds.

The 31P NMR spectrum at 263 K shows, next to the dominant signal of the free cation 3 + (98 %), a small high field shifted doublet resonance at δ(31P)=−55.5 ppm (2 %, 1 J PF=769 Hz), which is well in the region for a penta‐coordinate phosphorus atom, thus, indicating the formation of the CO2 adduct 5[OTf]. The corresponding resonance in the 19F NMR spectrum is detected as a downfield shifted doublet resonance at δ(19F)=−30.0 ppm. When the temperature is further decreased to 213 K the integral ratio of 5[OTf] increases to 41 : 59. The carbon atom of the bound CO2 is observed as a doublet resonance at δ(13C)=141.8 ppm (2 J PC=3 Hz). Further decrease of the temperature to 193 K leads to the separation of a colorless precipitate, suggesting that 5[OTf] exhibits a reduced solubility in CD2Cl2 at low temperature. Accordingly, gradually increase to RT leads to the dissolution of 5[OTf] and its disappearance in the NMR spectrum. This process is reversible without decomposition of 3[OTf]. We investigate this interaction of 3[OTf] with CO2 theoretically with two different models (Figure 3). In 3 +‐CO2 _A, CO2 is activated by the incorporation of both the Lewis acidic and the Lewis basic site, whereas in model 3 +‐CO2 _B the activation exclusively proceeds through the Lewis acidic P atom. The CO2 binding energy is slightly stronger for model 3 + ‐CO2 _A (−20.4 kJ/mol) than model 3 +‐CO2 _B (−18.4 kJ/mol). Moreover, the calculated 31P NMR chemical shift change (Δδ=δ(3 +‐CO2 _A)−δ(3 +)) for model 3 +‐CO2 _A (Δδ(31P)=−124 ppm) is in the range of the experimental result (Δδ(31P)=−110.7 ppm), while the calculated Δδ(31P) for model 3 +‐CO2 _B is only shifted by −17 ppm which is not observed in the respective 31P NMR spectrum. Thus, the CO2 activation is proposed to proceed via the P and pyridyl N atoms, affording 5[OTf] in the configuration of model 3 +‐CO2 _A. As the DFT calculation reveals a slightly improved CO2 binding energy (−23.0 kJ/mol) for 4[OTf], we also investigated the reactivity of 4[OTf] towards CO2 (Figure 3). Pressurizing a degassed CH2Cl2 solution of 4[OTf] with CO2 (0.5 bar) at ambient temperature results in the immediate formation of a colorless solid. However, the solid re‐dissolves immediately after releasing the pressure and all our separation attempts ended up with the recovery of 4[OTf]. We therefore monitored the reaction of 4[OTf] with CO2 (1.5 bar) by NMR spectroscopy in degassed CD3NO2. The 31P NMR spectrum at ambient temperature shows signals of two different adducts at δ(31P)=−60.0 ppm (1 J PF=737 Hz, 5 %) and δ(31P)=−61.5 ppm (1 J PF=740 Hz, 14 %) besides the signal of 4[OTf] (δ(31P)=55.2 ppm, δ(19F)=−111.5 ppm, 1 J PF=1045 Hz, Figure 2, right). The corresponding signals in the 19F spectrum are detected at δ(19F)=−8.1 ppm (1 J FP=737 Hz) and δ(19F)=−16.9 ppm (1 J FP=740 Hz), respectively. Interestingly, the 13C NMR spectrum displays two signals for the bound CO2 moiety at δ(13C)=139.9 ppm (2 J PC=7 Hz) as a doublet resonance and at δ(13C)=105.5 ppm (2 J PC=8 Hz) as a triplet resonance suggesting a coupling to two phosphorus atoms.13 This strongly indicates the formation of a 1 : 1 FLP‐CO2 adduct 6[OTf] (δ(31P)=−61.5 ppm, δ(19F)=−16.9 ppm, 1 J PF=740 Hz) and a 2 : 1 FLP‐CO2 adduct 7[OTf]2 (δ(31P)=−60.0 ppm, δ(19F)=−8.1 ppm, 1 J PF=737 Hz). The 31P NMR chemical shift change of 6[OTf] (Δδ=δ(6 +)−δ(4 +), −116.7 ppm) is well in the range of calculated model 4 +‐CO2 _A (Δδ(31P)=−108 ppm). Decreasing the temperature stepwise to 243 K, the integral ratio of 7[OTf]2 gradually increases to 66 %, while the integral ratio of 6[OTf] increases to 28 %. Variable‐temperature NMR studies at 0.5 or 2.0 bar CO2 pressure did not show significant difference on the integral ratio of 6[OTf] and 7[OTf]2. Although the calculated electrophilicities are similar for 3[OTf] (GEI=3.164 eV, FIA=748.0 kJ/mol) and 4[OTf] (GEI=3.121 eV, FIA=743.8 kJ/mol), [10] in no case do we observe a double activation of CO2 with 3[OTf]. This suggests that a certain nucleophilicity of the Lewis basic site is crucial for the formation of the 2 : 1 FLP‐CO2 adduct 7[OTf]2. [14]

Figure 3.

Optimized geometries and free energies of 3 +‐ and 4 +‐CO2 complexes (distances in Å, MP2/def2‐TZVP level of theory).

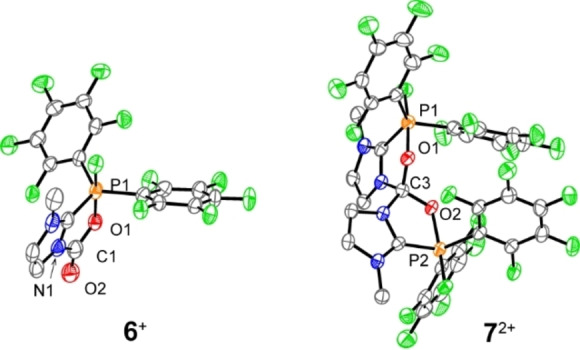

To our delight, we were able to obtain extremely sensitive but suitable co‐crystals containing both cations 6 + and 7 2+ by vapor diffusion of CH2Cl2 into a CH3NO2 solution of 4[OTf] under CO2 atmosphere (0.5 bar) at −30 °C (Figure 4). Although the double activation of CO2 has been reported with FLPs based on hafnium (VI) and aluminum (VII) complexes (Scheme 4),[ 13 , 15 ] the tetrahedral cation 7 2+ represents the only crystallographically characterized example of a metal‐free 2 : 1 FLP‐CO2 adduct.

Figure 4.

Molecular structure of co‐crystal 6[OTf]⋅7[OTf]2⋅CH3NO2 (hydrogen atoms, CH3NO2, and non‐coordinating anions are omitted for clarity, ellipsoids are set at 50 % probability). Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°); for 6 +: P1−O1 1.773(5), O1−C1 1.307(8), C1−N1 1.442(10), C1−O2 1.206(10), O1−C1−O2 128.1(7); for 7 2+: P1−O1 1.771(4), P2−O2 1.744(4), O1−C3 1.352(7), O2−C3 1.366(6), O1−C3−O2 114.4(5).

Scheme 4.

FLP‐CO2 adducts VI and VII containing a doubly activated CO2 molecule.

The molecular structure of 6 + which is consistent with the optimized structure 4+‐CO2 _A, shows that a CO fragment of the CO2 is integrated into a five‐membered PNC2O heterocycle while the other O atom is exocyclic. The CO2 moiety is bent, giving an O1−C1−O2 angle of 128.1(7)°. One oxygen is bound by the Lewis acidic P atom with a P1−O1 bond length of 1.773(5) Å and the carbon atom is stabilized by the Lewis basic N atom to give a N1−C1 bond length of 1.442(10) Å. The C1−O1 (1.307(8) Å) and C1=O2 (1.206(10) Å) bonds in the CO2 fragment are comparable to other FLP‐CO2 adducts (e. g., C−O 1.33 Å, C=O 1.21 Å).[ 9a , 16 ] In the case of the 2 : 1 FLP‐CO2 adduct 7 2+, the CO2 molecule is captured by two cations 4 + resulting in a distorted tetrahedral geometry of the central carbon atom. The P−O bond lengths (P1−O1 1.771(4) Å, P2−O2 1.744(4) Å) are similar to those of 6 +. The C−O bonds (O1−C3 1.352(7) Å, O2−C3 1.366(6) Å) are both significantly longer than those in 6 +, but comparable to those reported for the hafnium based FLP‐CO2 adduct VI (1.383 and 1.369 Å, Figure 4). [15]

Inspired by these results, further studies concerned the 1,3‐dipolar cycloaddition of salts 3,4[OTf] with carbonyls, nitriles, and acetylenes to the respective heterocycles (Scheme 5). At room temperature, the formation of acetone adducts 8 a, b[OTf] (8 a +/8 b +: δ(31P)=−52.0/−60.0 ppm, δ(19F)=−6.5/9.6 ppm, 1 J PF=734/696 Hz, 97 and 84 % isolated yield) and acetonitrile adducts 9 a, b[OTf] (9 a+ /9 b+ : δ(31P)=−49.3/−65.0 ppm, δ(19F)=3.0/19.9 ppm, 1 J PF=738/702 Hz, 71 and 95 % isolated yield) are indicated by multinuclear NMR spectroscopy (Table 1) and are isolated in good to excellent yields after workup. The carbonyl carbon atoms in 8 a, b[OTf] (8 a +/8 b +: δ(13C)=101.8/96.7 ppm, 2 J CP=9/11 Hz) are significantly shifted to higher field compared to the free acetone (δ(13C)=207 ppm). [17] The nitrile carbon atoms in 9 a,b[OTf] are shifted to lower field (9 a +/9 b +: δ(13C)=151.0/150.2 ppm, 2 J CP=18/19 Hz). Interestingly, when compounds 9 a, b[OTf] are reacted with acetone at room temperature, the formation of 8 a, b[OTf] under release of CH3CN is observed after a reaction time of 1 h (Scheme 5, ii). The quantitative exchange is indicated by the clean shift of the corresponding doublet resonance in the 31P NMR spectrum of the reaction mixture.

Scheme 5.

Reaction of 3/4[OTf] with unsaturated compounds; i) +Me2CO (1 equiv.), CH2Cl2, RT, 1 h; ii) +MeCN (1 equiv.), CH2Cl2, RT, 1 h; iii) +acetylenes (0.5 equiv.), DCE, RT, 4 h; iv) +acetylenes (1 equiv.), DCE, 80 °C, 16 h; v) RT, 2 weeks, or 80 °C, 16 h, −3/4[OTf]; vi) +Me2CO (1 equiv.), −MeCN, CH2Cl2, RT, 1 h.

Table 1.

Relevant 19F and 31P NMR data of the heterocycles 8–12[OTf].

|

Compound[a] |

Solvent |

δ(19F) (ppm) |

δ(31P) (ppm) |

1 J PF (Hz) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

8 a[OTf] |

CD2Cl2 |

−6.5 |

−52.0 |

734 |

|

8 b[OTf] |

CD2Cl2 |

9.6 |

−61.0 |

696 |

|

9 a[OTf] |

CD3CN |

3.0 |

−49.3 |

738 |

|

9 b[OTf] |

CD3NO2 |

19.9 |

−65.0 |

702 |

|

11 a[OTf]2 |

CD3CN |

– |

6.9 |

– |

|

11 a[OTf]2 |

DCE[a] |

– |

−15.0 |

– |

|

12 a[OTf] |

DCE[a] |

34.0 |

−88.8 |

707 |

|

12 b[OTf] |

CD2Cl2 |

25.2 |

−98.8 |

718 |

[a] With C6D6 capillary.

When 3, 4[OTf] are reacted with acetylenes in dichloroethane (DCE) at room temperature for 4 h, the formation of 10 a, b and 11 a, b[OTf]2 is observed, while 12 a, b[OTf] are cleanly formed by fluoride abstraction from 10 a, b to 11 a, b 2+ after reacting at 80 °C overnight or at ambient temperature for 2 weeks (Scheme 5, iii–v). Cation 11a 2+(GEI=7.408 eV, FIA=1066.9 kJ/mol) is more Lewis acidic than 3 + (GEI=3.164 eV, FIA=748.0 kJ/mol), thus, low reaction tendency from 11 a, b + to 12 a, b + seems to be influenced by solvent effects, which significantly decrease the Lewis acidity compared to the gas phase calculations.[ 10 , 18 ] 11 a, b[OTf]2 are found as singlet resonances in the 1P NMR spectra at δ(31P)=6.9 and −15.0 ppm, while 12 a, b[OTf] are observed as doublet resonances in the 31P and 19F NMR spectra (12 a +/12 b +: δ(31P)=−88.8/−98.8 ppm, δ(19F)=34.0/25.2 ppm, 1 J PF=707/718 Hz, Table 1). We were able to isolate 11 a[OTf]2 [19] (78 %) and 12 b[OTf] (66 %) as pure products for full characterization.

The molecular structures of compounds 8 a, b[OTf], 9 a, b[OTf] and 12 b[OTf] are confirmed by X‐ray analysis of suitable single crystals which were obtained by slow vapor diffusion of n‐pentane into saturated CH2Cl2 solutions at −30 °C (Figure 5). All obtained structures show a distorted trigonal‐bipyramidal bonding environment at the P atom and display the expected five‐membered heterocycles with angle sum ranging from 536.8° to 540.0° (Table 2). In the structures of 8 a, b + and 9 a, b +, the heteroatoms (O, N) and the fluorine atoms occupy the axial position. The P−F bonds (1.637(2) −1.673(13) Å) are elongated compared to those of the starting materials 3 + and 4 +, but comparable to those in difluorophosphoranes (e. g., (C6F5)3PF2: 1.638(2) Å). [20] The resulting P‐heteroatom distances in the acetone adducts (8 a +/8 b +: 1.695(2)/1.695(3) Å) are significantly shorter compared to the acetonitrile adducts (9 a +/9 b +: 1.777(2)/1.788(2) Å) while the C−N bonds are around 0.15 Å longer (8 a +/8 b +: 1.495(4) Å/1.411(5) Å, 9 a +/9 b +: 1.250(3)/1.272(3) Å, Table 2).

Figure 5.

Molecular structures of selected FLP adducts (hydrogen atoms, solvent molecules, and non‐coordinating anions are omitted for clarity, ellipsoids are set at 50 % probability); selected structural parameters are included in Table 2.

Table 2.

Selected geometrical parameters of the crystallographically characterized FLP adducts.

|

Compound |

P−F (Å) |

P−X[a] (Å) |

C−X[a] (Å) |

N−C (Å) |

Angle sum[b] (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

6[OTf] |

1.623(5) |

1.773(5) |

1.307(8) |

1.442(10) |

539.7 |

|

8 a[OTf] |

1.673(13) |

1.6989(15) |

1.398(2) |

1.519(3) |

536.8 |

|

8 b[OTf] |

1.637(2) |

1.695(2) |

1.411(5) |

1.495(4) |

537.2 |

|

9 a[OTf] |

1.6427(16) |

1.777(2) |

1.250(3) |

1.491(3) |

540.0 |

|

9 b[OTf] |

1.6426(16) |

1.788(2) |

1.272(3) |

1.458(4) |

539.9 |

|

12 b[OTf] |

1.651(3) |

1.773(5) |

1.330(8) |

1.415(6) |

539.2 |

[a] X=O (6 +, 8 a, b +), N (9 a, b +), C (12 b +); [b] Angle sum of the newly formed five‐membered ring.

The C−O bond lengths of the carbonyl moiety 8 a +/8 b +: 1.495(4)/1.411(5) Å and the C−N distances of the nitrile moiety (9 a +/9 b +: 1.250(3)/1.272(3) Å) are typical for C−O single bonds and C=N double bonds, respectively. [11] The structure of 12 b + shows that the pyridyl moiety is in the axial position, opposite to the fluorine atom (Figure 5). Thus, the terminal carbon atom of the alkyne occupies one of the equatorial positions adopting the minimum energy configuration due to steric restraints. The newly formed P1‐C1 bond distance (1.790(6) Å) and the N1−C2 bond distance (1.414(6) Å) are comparable to those in the acetonitrile adduct 9 b + (Table 2). The C1−C2 bond length (1.330(8) Å) is well in the range of a typical C=C double bond. [11]

Deposition Numbers 2061970 (for 4[OTf] ⋅ CH2Cl2), 2061971 (for 2[OTf]), 2061972 (for 3[OTf] ⋅ C6H5F), 2061973 (for 6[OTf] ⋅ 7[OTf]2 ⋅ CH3NO2), 2061974 (for 8 a[OTf] ⋅ CH2Cl2), 2061975 (for 8 b[OTf] ⋅ CH2Cl2), 2061976 (for 9 a[OTf] ⋅ (CH2Cl2)2 ⋅ CH3CN), 2061977 (for 9 b[OTf]), 2061978 (for 13), 2061979 (for 12b[OTf]), and 2061980 (for 14) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data are provided free of charge by the joint Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre and Fachinformationszentrum Karlsruhe Access Structures service.

In summary, electrophilic fluorophosphonium compounds bearing pyridyl (3[OTf]) or imidazolyl (4[OTf]) substituents, thus an additional Lewis basic site, represent a new type of intramolecular FLP that reacts with small molecules in a cooperative manner. The cyclizations of 3[OTf] and 4[OTf] with the 1,2‐dipolar compounds acetone, acetonitrile and acetylenes gave rise to the formation of the corresponding heterocyclic compounds, thus illustrating the cooperative reactivity of the new FLP derivatives. This is additionally demonstrated by the reversible formation of adducts with CO2 (5 + and 6 +) at low temperature, which was investigated by variable‐temperature NMR studies and X‐ray analysis. Surprisingly, the bifunctional phosphonium cation 4 + forms an adduct with CO2 (7 2+) comprising one molecule of CO2 and two molecules of 4 +, resulting in a spirocyclic geometry at the central carbon atom, which is hitherto unreported for an N/P FLP system. These novel bifunctional phosphonium cations extend the diverse library of FLP systems, and the reversible CO2 adduct formation might provide new applications for in FLP chemistry, which we are currently investigating.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the German Science foundation (project no. WE4621/6‐1) and C.‐X.G. thanks the China Scholarship Council (CSC no. 201506200056) for a scholarship. A.F. and A.B. thank the MICIU/AEI from Spain for financial support (project CTQ2017‐85821‐R, Feder funds). We also thank D. Harting for the acquisition of some of the X‐ray data and P. Lange for performing elemental analyses. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

C.-X. Guo, K. Schwedtmann, J. Fidelius, F. Hennersdorf, A. Dickschat, A. Bauzá, A. Frontera, J. J. Weigand, Chem. Eur. J. 2021, 27, 13709.

Dedicated to Professor Gerhard Erker on the occasion of his 75th birthday

References

- 1.

- 1a. Aresta M., Dibenedetto A., Angelini A., Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 1709–1742; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1b. Senftle T. P., Carter E. A., Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 472–475; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1c. Murphy L. J., Robertson K. N., Kemp R. A., Tuononen H. M., Clyburne J. A. C., Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 3942–3956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.

- 2a. Obersteiner M., Bednar J., Wagner F., Gasser T., Ciais P., Forsell N., Frank S., Havlik P., Valin H., Janssens I. A., Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 7–10; [Google Scholar]

- 2b. Song Q.-W., Zhou Z.-H., He L.-N., Green Chem. 2017, 19, 3707–3728. [Google Scholar]

- 3.

- 3a. Huang K., Sun C. L., Shi Z. J., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 2435–2452; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3b. Kondratenko E. V., Mul G., Baltrusaitis J., Larrazabal G. O., Perez-Ramirez J., Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 3112–3135; [Google Scholar]

- 3c. Yang Z.-Z., He L.-N., Gao J., Liu A.-H., Yu B., Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 6602–6639. [Google Scholar]

- 4.

- 4a. Sakakura T., Choi J.-C., Yasuda H., Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 2365–2387; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4b. Guo C.-X., Yu B., Xie J.-N., He L.-N., Green Chem. 2015, 17, 474–479. [Google Scholar]

- 5.

- 5a. Paparo A., Okuda J., Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 334, 136–149; [Google Scholar]

- 5b. Yu B., Zou B., Hu C.-W., J. CO2 Util. 2018, 26, 314–322. [Google Scholar]

- 6.

- 6a. Fiorani G., Guo W., Kleij A. W., Green Chem. 2015, 17, 1375–1389; [Google Scholar]

- 6b. Zhou H., Wang G.-X., Zhang W.-Z., Lu X.-B., ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 6773–6779; [Google Scholar]

- 6c. Zhou H., Wang G.-X., Lu X.-B., Asian J. Org. Chem. 2017, 6, 1264–1269; [Google Scholar]

- 6d. Fontaine F.-G., Courtemanche M.-A., Légaré M.-A., Chem. Eur. J. 2014, 20, 2990–2996; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6e. Wilm L. F. B., Eder T., Mück-Lichtenfeld C., Mehlmann P., Wünsche M., Buß F., Dielmann F., Green Chem. 2019, 21, 640–648; [Google Scholar]

- 6f. Buss F., Mehlmann P., Muck-Lichtenfeld C., Bergander K., Dielmann F., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 1840–1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.

- 7a. Stephan D. W., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 10018–10032; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7b. Erker G., Stephan D. W., Frustrated Lewis Pairs II: Expanding the Scope, Vol. 334, Springer, 2013; [Google Scholar]

- 7c. Stephan D. W., Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 306–316; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7d. Stephan D. W., Erker G., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 6400–6441; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 6498–6541. [Google Scholar]

- 8.

- 8a. Caputo C. B., Hounjet L. J., Dobrovetsky R., Stephan D. W., Science 2013, 341, 1374–1377; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8b. Perez M., Hounjet L. J., Caputo C. B., Dobrovetsky R., Stephan D. W., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 18308–18310; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8c. Caputo C. B., Winkelhaus D., Dobrovetsky R., Hounjet L. J., Stephan D. W., Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 12256–12264; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8d. von Wolff N., Lefèvre G., Berthet J. C., Thuéry P., Cantat T., ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 4526–4535. [Google Scholar]

- 9.

- 9a. Hounjet L. J., Caputo C. B., Stephan D. W., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 4714–4717; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 4792–4795; [Google Scholar]

- 9b. Vom Stein T., Perez M., Dobrovetsky R., Winkelhaus D., Caputo C. B., Stephan D. W., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 10178–10182; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 10316–10320; [Google Scholar]

- 9c. Holthausen M. H., Bayne J. M., Mallov I., Dobrovetsky R., Stephan D. W., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 7298–7301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guo C.-X., Yogendra S., Gomila R. M., Frontera A., Hennersdorf F., Steup J., Schwedtmann K., Weigand J. J., Inorg. Chem. Front. 2021, 8, 2854–2864. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Allen F. H., Kennard O., Watson D. G., Brammer L., Orpen A. G., Taylor R., J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2 1987, 12, S1-S19. [Google Scholar]

- 12.More details can be found in the Supporting Information.

- 13. Boudreau J., Courtemanche M. A., Fontaine F. G., Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 11131–11133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dewick P. M., Essentials of Organic Chemistry for Students of Pharmacy, Medicinal Chemistry and Biological Chemistry, Wiley, Hoboken, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sgro M. J., Stephan D. W., Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 2610–2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mömming C. M., Otten E., Kehr G., Fröhlich R., Grimme S., Stephan D. W., Erker G., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 6643–6646; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2009, 121, 6770–6773. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fulmer G. R., Miller A. J. M., Sherden N. H., Gottlieb H. E., Nudelman A., Stoltz B. M., Bercaw J. E., Goldberg K. I., Organometallics 2010, 29, 2176–2179. [Google Scholar]

- 18.

- 18a. Parr R. G., Von Szentpaly L., Liu S. B., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 1922–1924; [Google Scholar]

- 18b.P. Pérez, L. R. Domingo, A. Aizman, R. Contreras, A. Toro-Labbé, Theoretical Aspects of Chemical Reactivity, Vol. 19, Elsevier, 2007, pp. 139–201;

- 18c. Christe K. O., Dixon D. A., McLemore D., Wilson W. W., Sheehy J. A., Boatz J. A., J. Fluorine Chem. 2000, 101, 151–153; [Google Scholar]

- 18d. Jupp A. R., Johnstone T. C., Stephan D. W., Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 7029–7035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The obtained crystals of 11a[OTf]2 were not suitable to get a publishable data set due to severe disorder and were only usable for preliminary X-Ray diffraction analyses.

- 20. Sheldrick W., Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B 1975, 31, 1776–1778. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information