Abstract

Thrombosis after liver transplantation substantially impairs graft‐ and patient survival. Inevitably, heritable disorders of coagulation originating in the donor liver are transmitted by transplantation. We hypothesized that genetic variants in donor thrombophilia genes are associated with increased risk of posttransplant thrombosis. We genotyped 775 donors for adult recipients and 310 donors for pediatric recipients transplanted between 1993 and 2018. We determined the association between known donor thrombophilia gene variants and recipient posttransplant thrombosis. In addition, we performed a genome‐wide association study (GWAS) and meta‐analyzed 1085 liver transplantations. In our donor cohort, known thrombosis risk loci were not associated with posttransplant thrombosis, suggesting that it is unnecessary to exclude liver donors based on thrombosis‐susceptible polymorphisms. By performing a meta‐GWAS from children and adults, we identified 280 variants in 55 loci at suggestive genetic significance threshold. Downstream prioritization strategies identified biologically plausible candidate genes, among which were AK4 (rs11208611‐T, p = 4.22 × 10−05) which encodes a protein that regulates cellular ATP levels and concurrent activation of AMPK and mTOR, and RGS5 (rs10917696‐C, p = 2.62 × 10−05) which is involved in vascular development. We provide evidence that common genetic variants in the donor, but not previously known thrombophilia‐related variants, are associated with increased risk of thrombosis after liver transplantation.

Keywords: translational research/science, genetics, liver transplantation/hepatology, vascularized composite and reconstructive transplantation, genetics, thrombosis and thromboembolism, donors and donation, liver disease, microarray/gene array

Short abstract

A meta‐analysis of two genome‐wide association studies of adult and pediatric liver transplants identifies three common candidate risk loci in the donor, but not previously known thrombophilia‐related variants, were newly associated with increased risk of thrombosis after liver transplantation.

Abbreviations

- eQTL

expression quantitative trait locus

- GWAS

genome‐wide association study

- HAT

hepatic artery thrombosis

- MAF

minor allele frequency

- OLT

orthotopic liver transplantation

- PCA

principal component analysis

- PRS

polygenic risk score

- PVT

portal vein thrombosis

- SNP

single‐nucleotide polymorphism

- VTE

venous thromboembolism

1. INTRODUCTION

Posttransplant thrombosis is a potentially life‐threatening complication for orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) recipients, which may substantially reduce graft‐ and patient survival. 1 Studies in both pediatric and adult cohorts estimate an incidence of thrombotic events in up to 26% of cases. 2 Approximately 16% of graft failures are due to thrombotic complications, including hepatic artery thrombosis (HAT) and portal vein thrombosis (PVT). 3 , 4 , 5

Clinical risk factors for posttransplant thrombosis have been identified, however, potential genetic donor risk factors are less explored. 4 , 5 A consequence of OLT is that the recipient is potentially transplanted with inherited disorders of the coagulation pathway that originate in the donor liver. Recipient hypercoagulability in end‐stage liver disease in combination with an acquired additional genetic thrombosis risk from the donor graft may lead to an increased risk for posttransplant thrombosis. 6 , 7

Genetic variants have been associated with an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) through genome‐wide association studies (GWASs). 8 , 9 These studies have consistently identified associations with single‐nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the genes encoding Factor V Leiden (F5), ABO, F11, FGG, F2, protein C (PROC), PROS1, SERPINC1, STAB2, ZFPM2, TSPAN15, SLC44A2, PROCR, STXBP5, and FVIII, 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 which raises interest in the role of genetics in the development of thrombosis after OLT. There is, however, a lack of studies taking a genome‐wide approach in an OLT cohort, resulting in limited knowledge on the true effect of donor genetics on the development of thrombosis after OLT.

In this study, we first evaluated the influence of known variants in thrombophilia genes in the donors on the development of posttransplant thrombosis. We hypothesized that genetic variants in the donor liver are associated with an increased risk of posttransplant thromboembolic disease. To investigate this, we have tested common genetic variants in donors using a chip with a genome‐wide coverage for association with early thrombosis after liver transplantation. We have then integrated publicly available data on tissue specific expression, co‐expression, and disease association on the identified candidate genes to gain insight into the possible mechanisms underlying these genetic associations.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study design and patients

All consecutive OLT procedures performed in the University Medical Center Groningen between January 1993 and May 2018 were included. Characteristics of donor and recipient pairs were collected. Follow‐up data for graft failure and patient mortality were collected from patient records. All postoperative transplant care, including immunosuppression regimes (Table S1), were standardized according to local protocol. Low‐dose (≤100 mg/day) acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) was only administered after complex arterial reconstructions. The recipient cohort was registered in the Netherlands Trial Register (www.trialregister.nl – Trial NL6334) and was conducted within the TransplantLines cohort study, 15 which was approved by the institutional research board (METc 2014/077). The study protocol adhered to the declaration of Helsinki and is in concordance with the principles of the Declaration of Istanbul on Organ Trafficking and Transplant Tourism. STREGA guidelines for reporting genetic association studies were adhered to. 16

2.2. Outcome definitions

Posttransplant thrombosis was defined as any thrombotic event which developed within 90 days after transplantation (not present during surgery but found during post‐transplantation check‐ups, thereby excluding thrombosis which was most likely surgically related). The events were confirmed through either protocolized Doppler‐ultrasound imaging on days 1, 4, and 7 in adults and daily during the first week in children, computed tomography, or through surgery (relaparotomy). Thrombotic events included HAT, PVT, and other postoperative vascular complications such as pulmonary embolism (PE), deep vein thrombosis (DVT), cardiac or cerebral infarction, and thrombosis of other veins. Graft failure was defined as the lack of function of the implanted liver that required retransplantation or resulted in patient death. Primary nonfunction (PNF) was defined as liver failure requiring retransplantation or leading to death within 7 days after transplantation without any identifiable cause.

2.3. Genotyping and imputation procedure

A glossary of important methodological terminology can be found in Table S2. Details on sample DNA collection and genotyping are provided in the appendix. In short, genotyping was performed using the Infinium Global Screening Array‐24 v1.0 (Illumina, Inc). Markers with a low call rate (<99% of samples), a minor allele frequency (MAF) below 5%, a failed Hardy‐Weinberg equilibrium test (p > 1 × 10−06), and a significantly different call rate between cases and controls (p < .05) were removed. Samples with a low call rate (<99% of markers) or with outlying heterozygosity rate and with a discordant sex were removed (Figure S1). Quality control was performed and outliers were identified and removed (Figure S2). Imputation was performed using 1 KG phase 3 European reference panels. After imputation was completed, post‐imputation quality control was performed using a publicly available pipeline. 17 After post‐imputation and quality control, 5 393 447 variants were retained for the final analyses.

2.4. Targeted gene check

We summarized the reported associated polymorphisms based on previous VTE genetic studies in the general population (Table S3). In order to clarify the correlation between thrombosis genetic risk factors and the increased risk of thrombosis after OLT, we reported odd ratios (ORs) and the statistical value of the selected risk variants, or the proxy variants with high level of linkage disequilibrium (LD), in our OLT cohort. We also performed 12 gene‐based tests to study the effect of known thrombosis‐related genes on the risk of post‐OLT thrombosis. Based on literature, we tested the following thrombosis‐related genes: ABO, F5, F2, FGG, F11, PROC, STAB2, ZFPM2, TSPAN15, SLC44A2, PROCR, and STXBP5, which have been reported by two or more previous VTE genetic studies (Table S4). 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 24 We used all variants in and within 100 kb of each gene, and analyzed whether these variants were associated with post‐OLT thrombosis after clumping. p‐values of logistic regression were used to evaluate the included variants.

2.5. Genome‐wide association analysis

A genome‐wide association (GWA) analysis was performed between posttransplant thrombosis and paired donor genotypes. The cohort was stratified into two sub‐cohorts by recipient age (<18 and >=18 years) to separately examine the donor SNP effects in adult and pediatric recipients. After exclusion of two cases due to a lack of phenotype data, these sub‐cohorts included 310 donors in the pediatric group, and 775 donors in the adult group. GWA analysis was performed using PLINK. 25 Briefly, for each SNP a logistic regression model was fit to model postoperative thrombosis with genotyped or imputed SNPs, with adjustments for recipient age, recipient sex, donor age, donor sex, transplant era and the first three PCs of the donor genetics data to account for residual population structure. This GWA analysis was performed separately for each cohort and was followed by a meta‐analysis using PLINK to combine the results of the two cohorts. Detailed description of PLINK analysis can be found in the appendix. A Manhattan plot was used to show meta‐analyzed GWA result and a QQ plot was used to show the genomic inflation factor.

2.6. Locus definition and annotation

Our study effect‐size estimates are oriented to the positive strand of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Build 37/UCSC hg19 reference sequence of the human genome. To get more robust variants and to narrow down the candidate loci, we filtered out the variants with p‐values above .05 in both the pediatric and the adult cohort. We annotated all index variants with the web version of Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) based on Ensembl database (GRCh37 release 98). 26 The details of annotated genes for the identified variants are shown in the appendix. The presence of cis‐eQTL (cis‐expression quantitative trait locus) was derived using the Genotype‐Tissue Expression (GTEx) dataset. The biotype is an indicator of the biological significance of a gene. Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD) was used to predict the pathogenicity of protein‐altering index variants. 27

2.7. Functional annotation and prioritization of genetic variants

For functional gene selection, we carried variants with an eQTL effect in GTEx to further analysis. We adapted the scoring scheme designed by Fritsche et al. to highlight candidate genes for which there is biological plausibility for a role in thrombotic traits. 28 The results of GWA analyses were annotated based on the following criteria: (1) location in a functional region of each gene from the University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC) Known Gene database, (2) evidence of eQTL from FUMA analysis or the GTEx dataset, (3) evidence of expression in the liver or blood vessel tissues from Atlas, 29 (4) presence of thrombotic phenotype in humans from Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) or presence in any thromboembolism GWAS from GWAS Catalog, (5) gene with a significant enrichment in the tissue (liver/blood vessel) or in the gene priority analysis of Data‐driven Expression‐Prioritized Integration for Complex Traits (DEPICT), (6) presence of the gene in the canonical pathway analysis of the pathway database Reactome, (7) potential as a drug target from ChEMBL, 30 and (8) candidate variants with a MAF > 0.2.

2.8. Polygenic risk scores analyses

To analyze the genetic variance in thrombosis risk, we calculated polygenic risk scores (PRS) based on SNPs from a previously published GWAS, 11 using PRSice‐2 31 to calculate post‐OLT thrombosis PRS in our donor cohort. For a genetic explanation of posttransplant thrombosis, we estimated the proportion of variation in posttransplant thrombosis explained by the significantly associated loci through GCTA software. 32 To test genetic overlap with thrombosis subgroups (HAT/PVT), we calculated PRS based on our thrombosis association result and compared PRS within HAT/PVT subgroups. To identify the relationship between with and without graft failure in the first 3 months, we calculated PRS based on our thrombosis association result and compared PRS in the 90‐day graft functional group with PRS in the 90‐day graft failure group.

2.9. Statistical analysis

p‐values for differences in the study phenotype were calculated using Mann‐Whitney U test for continuous variables and chi‐square test for categorical variables. For the genetic association analyses, we used PLINK software, in which p‐value and 95% confidence intervals for ORs were obtained in the association test. For the meta‐analysis, we used a random‐effects bivariate meta‐analysis, combining adult and pediatric association statistics, with the standard errors of the beta coefficient. Genetic association analysis used 5 × 10−05 as suggestive significant threshold for further candidate gene selection, and additionally clinical statistical tests considered a p < .05 as significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patient characteristics

A total of 922 OLT recipients were included, who were from European ancestry and underwent 1085 OLT procedures for a variety of indications. Clinical characteristics of donor and recipient pairs are described in Table 1. Thrombotic cases included 60 recipients with HAT (5.5%), 25 recipients with PVT (2.3%), and 27 recipients with other thrombosis (2.5%), which occurred after a median of 7 days (IQR 4–22). During a median follow‐up period of 9 years, 282 of 922 (30.6%) recipients experienced graft loss and 143 recipients underwent retransplantation. We compared posttransplant thrombosis and non‐thrombosis groups in both the adult and pediatric cohort (Table 1). Donor smoking, previously reported as a risk factor for posttransplant thrombosis 3 in adults was not associated with recipient thrombosis risk in our meta‐analysis cohort (OR 1.194, 95% CI 0.761–1.875, p = .441). The same pattern was seen for arterial (OR 1.552, 95% CI 0.828–2.911, p = .170) and venous (OR 1.822, 95% CI 0.518–6.408, p = .350) reconstruction, which were not associated with recipient thrombosis in the overall cohort.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of baseline clinical characteristics in OLT procedures

| Total | Adult | Pediatric | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With thrombosis (n = 64) | Without thrombosis (n = 711) | p | With thrombosis (n = 42) | Without thrombosis (n = 268) | p | ||

| Donor | |||||||

| Age, years | 44 (28–54) | 49 (37–59) | 47 (36–56) | .504 | 22 (6–41) | 32 (13–48) | .014 |

| Sex (male) | 548 (50.5%) | 36 (56.2%) | 369 (51.9%) | .504 | 19 (45.2%) | 124 (46.3%) | .901 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.8 (21.7–25.8) | 24.5 (22.5–25.7) | 24.5 (22.5–26.2) | .482 | 22.5 (17.7–24.3) | 22.4 (19.4–24.4) | .796 |

| Type of donor | |||||||

| DBD | 810 (84.3%) | 54 (87.1%) | 581 (83.7%) | .310 | 20 (83.3%) | 155 (85.6%) | .840 |

| DCD | 122 (12.7%) | 7 (11.3%) | 110 (15.9%) | 1 (4.2%) | 4 (2.2%) | ||

| Living donor | 29 (3.0%) | 1 (1.6%) | 3 (0.4%) | 3 (12.5%) | 22 (12.2%) | ||

| Cause of death | |||||||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 685 (65.7%) | 39 (61.9%) | 482 (69.4%) | .459 | 19 (48.7%) | 145 (59.2%) | .465 |

| External cause | 321 (30.9%) | 22 (34.9%) | 192 (27.6%) | 18 (46.2%) | 89 (36.3%) | ||

| Others | 36 (3.5%) | 2 (3.2%) | 21 (3.0%) | 2 (5.1%) | 11 (4.5%) | ||

| Rhesus pos | 222 (25.1%) | 6 (10.2%) | 91 (13.4%) | .483 | 8 (100.0%) | 117 (85.4%) | .599 |

| CMV pos | 483 (45.8%) | 34 (54.8%) | 306 (44.4%) | .114 | 21 (51.2%) | 122 (46.2%) | .550 |

| Smoker | 378 (43.6%) | 36 (69.2%) | 276 (48.3%) | .004 | 4 (12.5%) | 62 (29.4%) | .054 |

| Hypertension | 186 (22.2%) | 10 (19.6%) | 144 (25.7%) | .340 | 4 (12.1%) | 28 (10.4%) | 1.000 |

| Recipient | |||||||

| Follow‐up, years | 9 (4–16) | 8 (4–15) | 9 (4–15) | — | 3 (0–14) | 8 (3–16) | — |

| Time since OLT, years | 13 (7–19) | 13 (7–17) | 13 (7–19) | .345 | 16 (7–19) | 12 (6–18) | .267 |

| Age, years | 42 (13–55) | 51 (36–58) | 51 (39–59) | .576 | 3 (1–8) | 5 (1–11) | .064 |

| Sex (male) | 596 (54.8%) | 41 (64.1%) | 407 (57.2%) | .290 | 21 (50.0%) | 127 (47.4%) | .753 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.6 (19.7–26.6) | 25.5 (22.7–27.3) | 24.7 (22.4–27.8) | .850 | 17.2 (15.9–19.0) | 17.4 (16.1–19.5) | .497 |

| Transplant indications | |||||||

| Acute hepatic failure | 43 (4.0%) | — | 7 (1.0%) | .641 | 3 (7.3%) | 33 (12.6%) | .106 |

| Alcoholic liver disease | 89 (8.4%) | 7 (11.1%) | 79 (11.4%) | 2 (4.9%) | 1 (0.4%) | ||

| Biliary cirrhosis/PSC | 302 (27.3%) | 20 (31.7%) | 244 (35.1%) | 4 (9.8%) | 34 (13.0%) | ||

| Congenital biliary disease | 153 (14.4%) | — | — | 22 (75.6%) | 131 (50.0%) | ||

| Metabolic | 175 (16.1%) | 14 (22.2%) | 116 (16.7%) | 8 (19.5%) | 37 (14.1%) | ||

| NASH/NALFD | 44 (4.1%) | 3 (4.8%) | 41 (5.9%) | — | — | ||

| Viral hepatitis | 113 (10.7%) | 6 (9.5%) | 104 (15.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (1.1%) | ||

| Other | 143 (13.5%) | 13 (20.6%) | 105 (15.1%) | 2 (4.9%) | 23 (8.7%) | ||

| BSA, m2 | 1.8 (1.3–2.0) | 1.9 (1.6–2.1) | 1.9 (1.8–2.1) | .460 | 0.7 (0.4–1.1) | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) | .849 |

| CMV pos | 241 (50.2%) | 17 (65.4%) | 194 (71.3%) | .525 | 4 (16.0%) | 26 (16.6%) | 1.000 |

| HBV pos | 46 (5.2%) | 2 (3.2%) | 42 (6.1%) | .571 | — | 2 (1.7%) | — |

| HCV pos | 67 (7.5%) | 4 (6.3%) | 62 (9.0%) | .643 | — | 1 (0.8%) | — |

| Malignancy | 58 (5.5%) | 6 (9.5%) | 39 (5.6%) | .212 | 0 (0.0%) | 13 (5.0%) | .227 |

| Retransplantation | 165 (15.2%) | 12 (18.8%) | 95 (13.4%) | .231 | 6 (14.3%) | 52 (19.4%) | .429 |

| Smoker | 116 (26.0%) | 9 (30.0%) | 107 (26.0%) | .628 | — | — | — |

| Lab MELD score | 16 (11–25) | 16 (11–23) | 15 (11–23) | .661 | 28 (28–28) | 30 (28–33) | .893 |

| CP‐score | 9 (7–11) | 9 (6–11) | 9 (7–11) | .450 | 10 (7–12) | 9 (7–12) | .687 |

| Thrombosis history | 133 (15.0%) | 9 (15.3%) | 110 (16.0%) | .875 | — | 14 (10.7%) | — |

| Karnofsky score | 60 (30–80) | 65 (40–80) | 70 (40–80) | .995 | — | — | — |

| Transplantation | |||||||

| Graft type | |||||||

| Full size | 824 (80.6%) | 59 (93.7%) | 675 (97.3%) | .116 | 10 (27.0%) | 80 (35.1%) | .337 |

| Partial | 198 (19.4%) | 4 (6.3%) | 19 (2.7%) | 27 (73.0%) | 148 (64.9%) | ||

| Aberrant artery | 90 (9.4%) | 8 (14.3%) | 63 (10.1%) | .322 | 4 (9.8%) | 15 (6.2%) | .404 |

| Arterial conduit | 79 (8.2%) | 6 (10.5%) | 49 (7.8%) | .462 | 1 (2.4%) | 23 (9.5%) | .132 |

| Arterial reconstruction | 92 (9.6%) | 11 (19.6%) | 66 (10.5%) | .039 | 2 (4.9%) | 13 (5.4%) | .892 |

| Venous reconstruction | 18 (1.9%) | 3 (5.3%) | 10 (1.6%) | .049 | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (2.1%) | .352 |

| Biliary anastomoses | |||||||

| D‐D | 829 (89.1%) | 40 (83.3%) | 493 (85.9%) | .627 | 42 (100.0%) | 254 (95.1%) | .228 |

| Roux‐Y | 102 (10.9%) | 8 (16.7%) | 81 (14.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 13 (4.9%) | ||

| Estimated blood loss, ml/kg | 59.4 (29.7–116.7) | 57.9 (23.3–105.5) | 52.6 (26.8–97.3) | .852 | 99.1 (37.2–176.6) | 84.7 (43.3–166.7) | .932 |

| CIT, min | 492 (406–613) | 489 (407–638) | 482 (405–606) | .814 | 535 (405–607) | 523 (407–631) | .947 |

| WIT, min | 47 (29–57) | 50 (40–60) | 47 (39–58) | .282 | 47 (40–58) | 46 (38–56) | .474 |

| Operation time, min | 575 (495–679) | 573 (510–690) | 575 (498–672) | .781 | 569 (499–798) | 573 (475–680) | .531 |

| Implantation (piggyback) | 624 (70.1%) | 41 (73.2%) | 406 (68.5%) | .463 | 25 (78.1%) | 152 (72.7%) | .520 |

| Postoperative results | |||||||

| Acute rejection | 235 (26.5%) | 12 (20.0%) | 217 (31.6%) | .061 | — | 6 (4.5%) | — |

| Biliary complication | 234 (22.1%) | 16 (25.8%) | 164 (23.8%) | .728 | 6 (14.3%) | 48 (18.0%) | .558 |

| Primary nonfunction | 29 (2.7%) | 0 (0) | 11 (1.6%) | .313 | 5 (11.9%) | 13 (4.9%) | .069 |

| Hospitalization, day | 29 (20–44) | 37 (22–50) | 28 (19–43) | .019 | 40 (27–51) | 29 (21–42) | .172 |

| ICU stay, day | 4 (2–9) | 4 (3–9) | 3 (2–6) | .006 | 13 (8–22) | 7 (4–13) | .002 |

Data are presented as frequency (%) or median (IQR). Chi square and Mann‐Whitney U test were used in categorical and numeric variables. Fisher's exact test was used when the case number is <5.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BSA, body surface area; CIT, cold ischemia time; CMV, cytomegalovirus; CP score, Child‐Pugh score; DBD, donation after brain death; DCD, donation after circulatory death; HBV/HCV, hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus infection; MELD, model for end‐stage liver disease; PNF, primary nonfunction; WIT, warm ischemia time.

Graft loss and patient mortality were high in patients with posttransplant thrombosis. After a median follow‐up period of 5.7 years a total of 44 (41.5%) patients with posttransplant thrombosis were deceased and 66 (62.3%) experienced graft loss following posttransplant thrombosis. Figure S3 depicts survival curves for OLT recipients with and without posttransplant thrombosis. Recipients with posttransplant thrombosis experienced the poorest graft survival during the first 90 days, as well as after 10 years (p < .001).

3.2. Known thrombosis risk gene replication

Looking at the influence of candidate variants identified by the available VTE genetic studies on increased posttransplant thrombosis risk (Table S3), we detected 163 associated variants or proxy (high LD – r 2 > .8) variants in our OLT cohort. Among the candidate loci, one of the variants (rs1336472‐G) surpassed the Bonferroni correction of 3.1 × 10−04 with a SNP x SNP interaction. After Bonferroni correction, none of the independent variants showed significant association with posttransplant thrombosis risk.

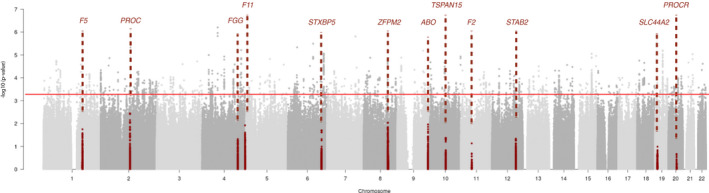

To evaluate the prevalence and the effect of previously reported thrombosis risk genes in our OLT cohort, we investigated the loci harboring 12 established thrombosis‐associated genes (ABO, F5, F2, FGG, F11, PROC, STAB2, ZFPM2, TSPAN15, SLC44A2, PROCR, and STXBP5) in our donor cohort (Figure 1; Table S4). In total, 65 loci were detected within the region of thrombosis risk genes. Among them, none of the variants surpassed the Bonferroni correction of 7.7 × 10−04, which suggests that variants in these thrombosis‐related genes cannot be used as a substantial genetic risk marker for developing posttransplant thrombosis in our OLT cohort.

FIGURE 1.

Manhattan plot of known associated gene‐sets replication. Association signals for 12 identified genes with a known role in thrombotic disease (ABO, F5, F2, FGG, F11, PROC, STAB2, ZFPM2, TSPAN15, SLC44A2, PROCR, and STXBP5). All variants in or within 100 kb of each gene are marked in dark red. The red line indicates the Bonferroni correction threshold of p‐value [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

To explore the effect of established VTE risk variants in the OLT cohort, we conducted PRS analyses on our donor cohort. After clumping the summary statistics of a venous thrombosis GWAS by Hinds et al, 11 50 variants remained above the suggestive significant threshold (5 × 10−05), which were compared between the posttransplant thrombosis and non‐thrombosis group. However, as shown in Figure S4A, there was no significant difference between them using the PRS of VTE (adjusted p = .71).

3.3. Genome‐wide associations with posttransplant thrombosis

We performed a GWA meta‐analysis of pediatric and adult recipient cohorts using their donor genotype, encompassing 106 cases and 979 controls. The analyses were based on 5 million genetic variants which were genotyped or imputed using the 1 KG reference panel, and which passed extensive quality control. Analyses were conducted in three stages: stage 1—pediatric OLT cohort (42 cases vs. 268 controls); stage 2—adult OLT cohort (64 cases vs. 711 controls); and stage 3—joint meta‐analysis.

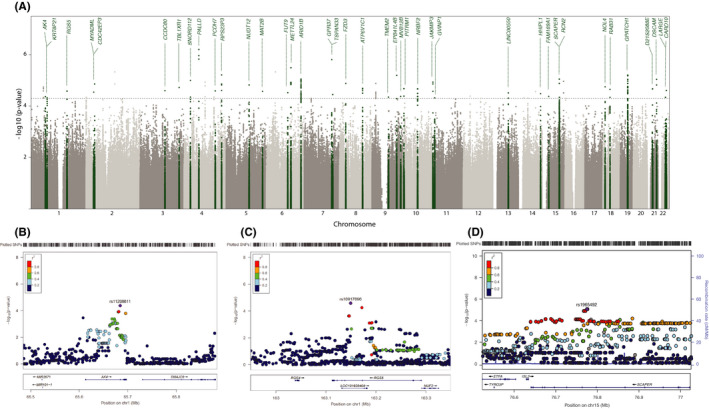

In our primary meta GWA, we identified 280 genetic variants exceeding suggestive significance, which were clustered in 55 loci (Table S5). The genomic inflation factor (λGC) in stage 3 was 0.988 (Figure S5). After filtering of variants which were significantly different between the pediatric and adult GWA results, 40 loci were considered to be consistent between cohorts (with p < .05 in both pediatric and adult cohort, Table 2; Figure 2A). These 40 genetic risk variants for posttransplant thrombosis explain 29% of thrombotic variance with the standard error of 0.05 in our donor cohort (GCTA heritability estimate calculation). Correction for donor smoking and vascular reconstruction did not change the results of this analysis (Table S6).

TABLE 2.

Meta‐analysis results of donor loci associated with postoperative thrombotic events

| SNP | CHR | POS | Effect allele | Other allele | MAF | Meta OR | Meta p value | Q | Pediatric cohort (n = 310) | Adult cohort (n = 775) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | SE | p value | OR | SE | p value | |||||||||

| rs35150895 | 4 | 67445833 | A | G | 0.05 | 3.45 | 6.28E−07 | 0.29 | 4.92 | 0.42 | 1.39E−04 | 2.84 | 0.31 | 7.22E−04 |

| rs7784948 | 7 | 124069511 | T | G | 0.09 | 2.58 | 1.55E−06 | 0.99 | 2.59 | 0.33 | 4.50E−03 | 2.58 | 0.24 | 1.07E−04 |

| rs72935945 | 6 | 110655675 | T | C | 0.19 | 2.23 | 3.21E−06 | 0.99 | 2.23 | 0.29 | 4.97E−03 | 2.24 | 0.22 | 2.03E−04 |

| rs9998058 | 4 | 169596553 | C | T | 0.07 | 2.71 | 6.14E−06 | 0.56 | 3.25 | 0.38 | 2.15E−03 | 2.48 | 0.27 | 7.50E−04 |

| rs10421769 | 19 | 33605312 | C | T | 0.33 | 0.42 | 6.32E−06 | 0.30 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 4.92E−04 | 0.49 | 0.24 | 2.28E−03 |

| rs3849111 | 9 | 111994722 | A | C | 0.37 | 0.43 | 6.53E−06 | 0.33 | 0.54 | 0.29 | 3.04E−02 | 0.37 | 0.24 | 4.64E−05 |

| rs56222681 | 6 | 156478953 | A | G | 0.14 | 2.30 | 8.82E−06 | 0.59 | 2.64 | 0.31 | 1.81E−03 | 2.13 | 0.24 | 1.32E−03 |

| rs1965492 | 15 | 76773326 | C | A | 0.42 | 1.98 | 8.89E−06 | 0.76 | 1.87 | 0.24 | 1.01E−02 | 2.05 | 0.20 | 2.77E−04 |

| rs56076602 | 21 | 42051160 | G | C | 0.08 | 2.78 | 9.18E−06 | 0.10 | 4.57 | 0.38 | 5.66E−05 | 2.07 | 0.29 | 1.25E−02 |

| rs10049756 | 4 | 28872833 | A | G | 0.12 | 2.27 | 1.01E−05 | 0.95 | 2.24 | 0.30 | 6.60E−03 | 2.29 | 0.24 | 4.97E−04 |

| rs2818388 | 10 | 133953647 | A | C | 0.07 | 2.67 | 1.17E−05 | 0.49 | 2.19 | 0.36 | 3.09E−02 | 3.01 | 0.28 | 1.06E−04 |

| rs34979186 | 8 | 28445552 | G | A | 0.06 | 2.90 | 1.33E−05 | 0.76 | 3.21 | 0.40 | 3.95E−03 | 2.74 | 0.31 | 1.04E−03 |

| rs72789970 | 2 | 37970145 | G | A | 0.05 | 2.92 | 1.37E−05 | 0.92 | 2.82 | 0.42 | 1.40E−02 | 2.97 | 0.30 | 3.31E−04 |

| rs1288906 | 5 | 103023993 | T | A | 0.16 | 2.16 | 1.50E−05 | 0.56 | 1.86 | 0.31 | 4.57E−02 | 2.32 | 0.22 | 1.03E−04 |

| rs9951171 | 18 | 9749879 | A | G | 0.41 | 0.48 | 1.76E−05 | 0.86 | 0.47 | 0.27 | 5.21E−03 | 0.50 | 0.22 | 1.10E−03 |

| rs73179545 | 3 | 176238294 | C | T | 0.08 | 2.70 | 1.90E−05 | 0.39 | 3.60 | 0.41 | 1.71E−03 | 2.35 | 0.28 | 2.44E−03 |

| rs1566159 | 8 | 104090278 | A | T | 0.36 | 0.47 | 2.04E−05 | 0.73 | 0.44 | 0.28 | 2.91E−03 | 0.50 | 0.23 | 2.16E−03 |

| rs10904015 | 10 | 3327415 | G | A | 0.22 | 2.01 | 2.08E−05 | 0.74 | 1.86 | 0.27 | 2.36E−02 | 2.09 | 0.20 | 2.94E−04 |

| rs59286975 | 10 | 64736664 | A | G | 0.07 | 2.70 | 2.15E−05 | 0.96 | 2.66 | 0.41 | 1.80E−02 | 2.72 | 0.28 | 4.15E−04 |

| rs2827676 | 21 | 24030707 | T | C | 0.13 | 2.25 | 2.15E−05 | 0.57 | 1.93 | 0.33 | 4.35E−02 | 2.43 | 0.24 | 1.56E−04 |

| rs9957543 | 18 | 31659307 | G | C | 0.42 | 0.48 | 2.21E−05 | 0.60 | 0.54 | 0.28 | 2.62E−02 | 0.45 | 0.22 | 2.61E−04 |

| rs932327 | 22 | 37905173 | G | A | 0.15 | 2.11 | 2.43E−05 | 0.47 | 2.51 | 0.30 | 1.93E−03 | 1.92 | 0.22 | 3.13E−03 |

| rs11933913 | 4 | 169609033 | G | A | 0.17 | 2.10 | 2.45E−05 | 0.14 | 2.96 | 0.29 | 1.96E−04 | 1.72 | 0.22 | 1.33E−02 |

| rs6438086 | 3 | 112359986 | A | G | 0.33 | 0.45 | 2.52E−05 | 0.46 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 2.46E−03 | 0.50 | 0.23 | 2.51E−03 |

| rs77944815 | 4 | 141194295 | T | C | 0.08 | 2.53 | 2.59E−05 | 0.76 | 2.33 | 0.35 | 1.64E−02 | 2.67 | 0.28 | 5.24E−04 |

| rs10917696 | 1 | 163149325 | C | T | 0.22 | 2.02 | 2.63E−05 | 0.57 | 1.77 | 0.29 | 4.64E−02 | 2.16 | 0.21 | 1.80E−04 |

| rs72816289 | 5 | 163771489 | G | A | 0.07 | 2.83 | 2.67E−05 | 0.41 | 3.62 | 0.39 | 1.04E−03 | 2.40 | 0.32 | 6.02E−03 |

| rs11903647 | 2 | 34027682 | G | A | 0.10 | 2.36 | 2.91E−05 | 0.87 | 2.47 | 0.35 | 8.78E−03 | 2.30 | 0.26 | 1.11E−03 |

| rs6571194 | 6 | 96755269 | C | T | 0.28 | 0.42 | 3.03E−05 | 0.44 | 0.51 | 0.33 | 4.12E−02 | 0.37 | 0.27 | 1.99E−04 |

| rs969663 | 13 | 69408347 | C | T | 0.46 | 1.89 | 3.12E−05 | 0.43 | 1.63 | 0.24 | 4.44E−02 | 2.08 | 0.20 | 1.92E−04 |

| rs35752324 | 14 | 100134209 | T | C | 0.13 | 2.23 | 3.34E−05 | 0.99 | 2.24 | 0.34 | 1.89E−02 | 2.23 | 0.23 | 6.24E−04 |

| rs71582000 | 7 | 128780057 | G | A | 0.08 | 2.51 | 3.59E−05 | 0.89 | 2.40 | 0.39 | 2.41E−02 | 2.57 | 0.27 | 5.30E−04 |

| rs953226 | 9 | 129286868 | A | C | 0.08 | 2.41 | 4.13E−05 | 0.79 | 2.62 | 0.37 | 9.81E−03 | 2.32 | 0.26 | 1.40E−03 |

| rs2292630 | 15 | 29429143 | T | C | 0.06 | 2.88 | 4.19E−05 | 0.88 | 2.72 | 0.46 | 2.92E−02 | 2.96 | 0.31 | 5.18E−04 |

| rs11208611 | 1 | 65684425 | T | C | 0.32 | 1.92 | 4.22E−05 | 0.94 | 1.89 | 0.26 | 1.38E−02 | 1.94 | 0.20 | 1.07E−03 |

| rs4745114 | 9 | 74304506 | A | G | 0.46 | 0.52 | 4.43E−05 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.27 | 2.09E−03 | 0.57 | 0.20 | 5.18E−03 |

| rs5994697 | 22 | 33607304 | A | C | 0.33 | 0.47 | 4.54E−05 | 0.37 | 0.56 | 0.28 | 4.04E−02 | 0.40 | 0.25 | 2.74E−04 |

| rs17380507 | 15 | 77235361 | T | C | 0.48 | 0.53 | 4.58E−05 | 0.87 | 0.54 | 0.25 | 1.53E−02 | 0.52 | 0.20 | 1.04E−03 |

| rs75030100 | 1 | 73511653 | T | G | 0.07 | 2.63 | 4.75E−05 | 0.14 | 4.34 | 0.41 | 3.68E−04 | 2.05 | 0.29 | 1.37E−02 |

| rs11825966 | 11 | 6734161 | T | C | 0.06 | 2.63 | 4.75E−05 | 0.73 | 2.35 | 0.41 | 3.90E−02 | 2.79 | 0.29 | 4.30E−04 |

Meta analyses of two genome‐wide association (GWA) analyses: the adult and the paediatric OLT cohort. Variants with both significant p‐value in adult and paediatric cohort (p < .05) are shown, and variants are sorted by p‐value (with the cut‐off value of 5 × 10−05). The GWA results in adult and pediatric OLT cohort are reported by OR, SE and p‐value, respectively.

Abbreviations: CHR, chromosome; MAF, minor allele frequency; OR, odd ratio; POS, position per base‐pair; Q, p‐value for Cochrane's Q statistic; SE, standard error of OR; SNP, single‐nucleotide polymorphism.

FIGURE 2.

Association thrombosis signals of meta‐analyses results. (A) Manhattan plot. −log10 p‐values of the quantified SNPs were plotted against their genomic positions. Green colors indicate the 40 candidate donor risk loci. Gene labels are annotated as the nearest genes to the associated SNPs. The dashed line indicates the suggestive significant threshold (5 × 10−05): (B) Chr.1 AK4 locus, (C) Chr.1 RGS5 locus, and (D) Chr.1 ETFA locus. In each, the top panel reflects the meta‐analysis results. The LD estimates are color coded as a heatmap from dark blue (0≥ r 2 >.2) to red (0.8≥ r 2 > 1.0). The bottom panel shows the genes and their orientation for each region. p‐values are from meta‐analysis of logistic regression p‐values. Reference genome: hg19/1000 Genomes Nov 2014 EUR [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.4. Gene annotation of susceptibility loci

From our identified risk variants, we checked the GTEx dataset and identified 15 variants that have expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) among the 40 genetic variants. Table 3 lists the above‐mentioned genetic variants by using the UCSC gene annotation database to present a detailed description. Of the identified variants, 27% are either intragenic or less than 50 kb from the 5′ or 3′ end of the transcription start site. The most significant identified genetic variant (rs10421769, p = 6.32 × 10−06) is an exonic variant, which is found in the GPATCH1 locus with MAF of 0.35 in Europeans. Also, within the protein coding region, in total 10 identified risk variants have been detected with liver or aorta artery eQTLs based on GTEX database (Table S7).

TABLE 3.

Detailed annotation of candidate donor risk loci with eQTL

| SNP | CHR | POS | Nearest gene(s) | eQTL gene(s) | Variant annotation | HGVS coding sequence | Biotype | EUR AF | CADD Phred |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs10421769 | 19 | 33605312 | GPATCH1 | GPATCH1, RHPN2, WDR88, PDCD5, NUDT19, LRP3 | Missense variant | p.Leu728Ser | Protein coding | 0.35 | 13.41 |

| rs1965492 | 15 | 76773326 | SCAPER | SCAPER, ETFA, ISL2, RCN2, TSPAN3 | Intron variant | c.2955‐9650G>T | Protein coding | 0.57 | 7.71 |

| rs2818388 | 10 | 133953647 | JAKMIP3 | JAKMIP3, DPYSL4 | Intron variant | c.1345‐308C>A | Protein coding | 0.10 | 0.19 |

| rs34979186 | 8 | 28445552 | FZD3 (dist=13767) | FZD3 | Intergenic variant | — | — | 0.05 | 2.52 |

| rs1566159 | 8 | 104090278 | ATP6V1C1 (dist=4999), BAALC (dist=62675) | BAALC | Downstream gene variant | — | Protein coding | — | 1.73 |

| rs59286975 | 10 | 64736664 | EGR2 (dist=157737), NRBF2 (dist=156343) | ADO | Intergenic variant | — | — | 0.07 | 3.17 |

| rs932327 | 22 | 37905173 | CARD10 | CARD10, MFNG | Intron variant | c.910–484T>C | Protein coding | 0.17 | 1.37 |

| rs6438086 | 3 | 112359986 | CCDC80 | CCDC80 | 5 prime UTR variant | c.−824T>C | Protein coding | 0.64 | 11.41 |

| rs10917696 | 1 | 163149325 | RGS5 | RGS5, NUF2 | Intron variant | c.45‐11167A>G | Protein coding | 0.22 | 7.29 |

| rs72816289 | 5 | 163771489 | MAT2B (dist=825130) | CTC−340A15.2 | Intron variant, non‐coding transcript variant | n.229‐9658A>G | Antisense | 0.08 | 7.33 |

| rs969663 | 13 | 69408347 | LINC00550 (dist=27069) | LINC00550 | Intergenic variant | — | — | — | 0.11 |

| rs35752324 | 14 | 100134209 | HHIPL1 | HHIPL1, CYP46A1 | Intron variant | c.1649‐350C>T | Protein coding | 0.12 | 1.05 |

| rs953226 | 9 | 129286868 | MVB12B (dist=17548) | MVB12B | Upstream gene variant | — | lincRNA | 0.08 | 9.45 |

| rs11208611 | 1 | 65684425 | AK4 | AK4 | Intron variant | c.266‐12C>T | Protein coding | 0.30 | 13.90 |

| rs17380507 | 15 | 77235361 | RCN2 | SCAPER, ETFA, ISL2, RCN2, NRG4 | Intron variant | c.448‐738C>T | Protein coding | 0.49 | 2.13 |

All variants were annotated with the web version of Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) based on Ensembl database (GRCh37 release 98). For variants within the coding sequence or 5′ or 3′ UTRs of a gene, that gene was assigned to the index variant, in addition for variants in intergenic regions, the nearest gene was assigned to the variant. eQTL (SNP–gene expression association) was checked from Genotype‐Tissue Expression (GTEx) dataset (release v7). HGVS identifiers for variants was relative to the transcript coding sequence (Human Genome Variation Society, HGVSc). The biotype is an indicator of biological significance of gene classification, which including protein coding gene, processed transcripts, and pseudogene. Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD) was used to predict the pathogenicity of protein‐altering index variants.

Abbreviations: CHR, chromosome; EUR AF, allele frequency in European population based on 1000 Genomes phase 3 population; POS, position per base‐pair; SNP, single‐nucleotide polymorphism.

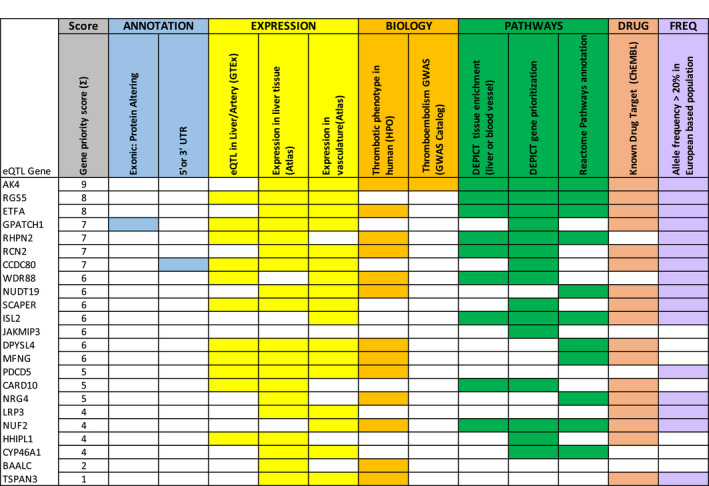

3.5. Prioritization and functional annotation of risk variants

The 10 genetic variants with an eQTL effect related to a total of 23 genes (Table S7). Figure 3 shows the prioritized rank of the identified eQTL genes based on an established scoring scheme, 28 including annotation from reported literatures, gene expression in different tissues, biological function, pathway annotation, and drug target detection. Out of the 23 eQTL genes, 11 associations are observed in liver or blood vessel tissue. One is annotated in the exonic region and one was located in the 3′ or 5′ untranslated region (UTR). Thirteen genes are relevant in the development of thrombosis in humans with the searching items of abnormal thrombosis (HP:0001977), venous thrombosis (HP:0004936), splanchnic vein thrombosis (HP:0030247), and arterial thrombosis (HP:0004420) by HPO 33 ; 14 genes are both expressed in human liver and blood vessel by GTEX; 15 genes are identified by DEPICT gene prioritization analysis at p < 5×10−05 (Table S8); and 11 genes contributed to the most significant Reactome pathway annotation. We use DEPICT to test for expression of associated genes across tissues, and found nine genes enriched in liver or blood vessel systems (marked in red in Table S9). Six of 10 loci have an allele frequency larger than 0.2 in the European population, which is important when considering implementing the use of genetic testing. Notably, when we cross‐check our list of identified genes with a public drug database, 30 we find that 17 of the associated genes are currently being used as drug targets.

FIGURE 3.

Prioritization of candidate genes in risk loci through biological annotation. To prioritize the most likely candidate genes within each risk locus, the results of GWAS analyses were further annotated and ranked based on following criteria: (1) exact location (selected protein coding genes) through the UCSC Known Gene database, (2) evidence of eQTL from FUMA analysis and the GTEx dataset, (3) evidence of expression in the liver or blood vessel tissues from Atlas, (4) presence of thrombotic phenotype in humans from HPO or presence in any thromboembolism GWAS from GWAS Catalog, (5) gene enrichment in the liver or blood vessel tissue or in the gene priority analysis of DEPICT, (6) presence of the gene in the canonical pathway analysis of REACTOME, (7) potential as a drug target from ChEMBL, (8) variants with minor allele frequency >0.2 in European population [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

After the combined evaluation, the genes with highest biological plausibility are AK4 (rs11208611‐T, p = 4.22 × 10−05), RGS5 (rs10917696‐C, p = 2.63 × 10−05), and ETFA (rs1965492‐C, p = 8.89 × 10−06), for which the locus of their index variants was verified in LocusZoom 34 (Figure 2), and their expression in multiple tissues was investigated in the GTEx (Figure S6). Figure 2B shows a regional association plot for the genomic region 200 kb upstream and downstream of the lead SNP rs11208611 in the meta‐GWAS stage. Within the region, 11 genotyped and 94 imputed SNPs, including rs11208611, are associated with posttransplant thrombosis (p < .05). The thrombosis‐associated genomic interval indexed by rs11208611 on 1p31 overlaps with a single known gene, adenylate kinase 4 (AK4), while the lead SNP rs11208611, which is highly correlated with a replicated VTE variant (rs1336472, R 2 = .691, p < .001), is located in the intron of AK4 gene. Figure 2C shows that the region of lead SNP rs10917696 on 1q23 overlaps with a single known gene, encoding a member of the regulators of G protein signaling (RGS) family. The lead SNP rs10917696 is located in an intron of RGS5 and LOC101928404. Figure 2D shows that the region of lead SNP rs1965492 on 15q24 overlaps with a known gene named SCAPER, but has an eQTL effect on the electron transfer flavoprotein subunit alpha (ETFA) gene, encoding a catalyst of the mitochondrial fatty acid beta‐oxidation.

3.6. Genetic association in posttransplant thrombosis subgroups

To clarify the rationality and validity of the composite thrombosis outcome in our analyses, we checked whether the three biologically most plausible variants (rs11208611, rs10917696, and rs1965492) are driven by all thrombotic subgroups. We performed genetic association analysis on thrombosis subgroups, including HAT, PVT, and other thrombosis, and subsequently performed a meta‐analysis of the three thrombosis subgroups (Table S10). We compared the association results of rs11208611, rs10917696, and rs1965492 from each thrombosis subgroup, and found that rs10917696 is mostly driven by HAT (p = 1.54 × 10−04) and other thrombosis (p = 2.68 × 10−03).

To explore the effect of our polygenic risk scores (PRS) on different posttransplant thrombosis subgroups and short‐term graft survival, we compared the PRS calculated from our meta‐GWAS results between HAT and PVT subgroups. The PRS shows no significant difference between HAT cases and PVT cases (Figure S4B), which indicates that donor genetic risk factors will likely contribute to all thrombotic events, and the results are not driven by HAT or PVT or an other subgroup of thrombosis. Moreover, PRS calculated from thrombotic events are higher in cases with short‐term graft failure (p = 7.8 × 10−06, Figure S4C).

4. DISCUSSION

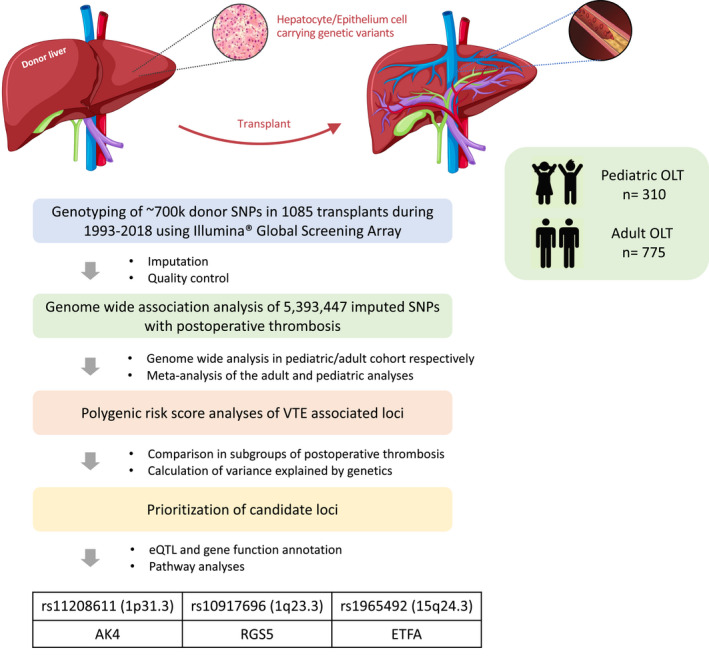

This study aimed to identify the effect of donor genetics on the development of posttransplant thrombosis after OLT using GWAS. We collected genetic data from 1085 liver donors, the largest genotyped OLT donor cohort to date, and stratified these into two groups based on the occurrence of posttransplant thrombosis. We show that the presence of variants in previously known thrombophilia genes in the donor liver did not significantly increase the risk to develop posttransplant thrombosis after OLT in the investigated cohort. In addition, this study identified three novel candidate genes that are associated with the development of posttransplant thrombosis in OLT recipients (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Flowchart of genome‐wide association analyses in the adult and pediatric OLT cohorts. Schematic diagram of the study design. For each SNP showing a 5% minor allele frequency in the donor cohort, association was tested between the presence/absence of postoperative thrombotic events and the donor genotype using logistic regression model, with corrections for donor and recipient covariates. GWAS was performed in adult and pediatric cohort, respectively, and meta‐analyze their results in a random effects model. Biological annotation of meta‐GWAS results was done for candidate gene prioritization. eQTL, expression quantitative trait locus; GWAS, genome‐wide association study; OLT, orthotopic liver transplantation; SNP, single‐nucleotide polymorphism [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Donor thrombophilia screening is routinely performed at some medical centers, and has been recommended in the context of living donor liver donation. Previous genetic studies have identified multiple risk loci for thromboembolism, including the Factor V Leiden (FVL in F5; rs6025) and prothrombin G20210A (in F2; rs1799963) mutations. 35 We have summarized the associated VTE risk variants in Table S3. The presence of factor V Leiden or factor XIII G100T in the donor liver was previously reported to be associated with an increased risk of HAT after OLT. 36 One study reported a case of HAT in one OLT recipient whose native and donor livers were both heterozygous for FVL. 37 Other case reports have described acquired activated protein C resistance after OLT due to FVL mutation of the donor liver, leading to thrombotic complications. 38 , 39 Our results, however, are in line with a previous study which reported that FVL mutation in the donor liver was not a risk factor for posttransplant thrombosis and subsequent graft loss in a cohort of 276 liver transplants. 40 In another case report, acquired Protein S deficiency due to a mutation of the donor liver was implicated in posttransplant thrombosis, 41 whereas on the other hand a successful case of living donor liver transplantation was reported using a donor with asymptomatic protein S deficiency. The potential reason for a non‐thrombotic phenotype in the latter report could be the compensation by extra‐hepatic protein S production in the recipient. 42 This underscores the difficulty of thrombophilia screening, especially in the context of live liver donation. In a recent study of 584 potential live liver donors, 33 of 428 (8%) declined candidates were excluded because of hematological reasons, most commonly thrombophilia. Interestingly, in the same study 156 candidates proceeded to live liver donation of which 21 (13%) had evidence of possible thrombophilia, and none of them incurred hematologic complications. 43

The novelty of the current study is that we sought to identify robust donor specific loci associated with early thrombosis after liver transplantation by testing common genetic variants, using a chip with genome‐wide coverage. We initially analyzed previously reported thrombotic genes such as ABO, F5, F2, FGG, F11, PROC, STAB2, ZFPM2, TSPAN15, SLC44A2, PROCR, and STXBP5 (shown in Table S4). Within our donor cohort, however, none of these genes were significantly associated with thrombosis after OLT. The targeted thrombosis‐associated gene sets are shown in the Manhattan plot (Figure 1). This information is important, as it suggests that it is not necessary to exclude liver donors carrying thrombosis‐susceptible polymorphisms such as FVL for liver transplantation.

From the GWA data, we prioritized three candidate genes for increased risk of posttransplant thrombosis. The first of these candidate genes was AK4 (rs11208611‐T, p = 4.22 × 10−05), a highly conserved gene encoding a member of the adenylate kinase family of enzymes. This enzyme is mainly expressed in tissues rich in mitochondria, such as the brain, heart, kidney, and liver, and it indirectly modulates the mitochondrial membrane permeability via its interaction with ADP/ATP translocase. 44 AK4 plays a role in controlling cellular ATP levels by regulating phosphorylation and activation of the energy sensor protein kinase AMPK. 45 AMPKα2 may affect Fyn phosphorylation, which activity plays a key role in platelet αIIbβ3 integrin signaling, leading to clot retraction and thrombus stability. 46 Importantly, the identified variant was in high LD with replicated VTE associated variant (rs1336472) and AK4 was previously reported as a risk gene for development of VTE in a European GWAS. 47

The second candidate gene is RGS5, which encodes a member of the regulators of the G protein signaling (RGS) family. The RGS proteins are signal transduction molecules which are involved in the regulation of heterotrimeric G proteins by acting as GTPase activators. Previous studies indicated that RGS5 may play an important role in vascular development. 48 The abundance of regulation by RGS5 was reported as an increase in vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs) of remodeling collateral arterioles. 49 It has been identified as a key regulator of vascular remodeling and is critical for cardiovascular functions, but has not yet been reported in any thromboembolism GWAS.

The third identified gene is ETFA, encoding an electron acceptor in the mitochondrial fatty acid beta‐oxidation. Combining the prioritization of DEPICT and HPO results, we found ETFA was associated with the given phenotype of “arterial or venous thrombosis” and was required for normal mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and amino acid metabolism. 50

A limitation of this study is that we have a relatively small cohort when compared to genetic studies in other traits. In the field of liver transplantation, however, the present study represents the largest genotyped donor cohort to date. We have combined all posttransplant thrombosis events as a composite endpoint to gain sufficient statistical power. Although we acknowledge that HAT and PVT may have a different mechanism when considering posttransplant thrombosis pathophysiology, genetic donor risk factors will likely contribute to all thrombotic events. We also demonstrate that most genetic association results were not driven by a single subgroup (i.e., HAT or PVT) of thrombosis (Table S10). In our study cohort, the average laboratory MELD score at transplantation was relative low (with median of 16) when compared to other countries, such as the Unites States. This could limit the generalizability of our findings to sicker recipients with higher laboratory MELD scores. Finally, this study was performed with a relatively homogeneous European population, indicating that replication and further validation is required to assess donor genetics risk in other, more diverse, non‐European cohorts.

In conclusion, in our study we have investigated the impact of donor genetics on thrombosis after OLT. Based on our GWAS results, we found that previously reported common thrombotic genetic variants were not associated with the development of posttransplant thrombosis in our cohort. Furthermore, we have newly identified three candidate genetic polymorphisms of the donor which were associated with posttransplant thrombosis. Future investigations are warranted to corroborate our findings and to further uncover the mechanisms behind the development of posttransplant thrombosis. Improved understanding of the genetic risk associated with posttransplant thrombosis could help in preventative or predictive measures and improve risk stratification of liver donors.

DISCLOSURE

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Y.L., E.A.M.F., and V.E.M. designed the study, interpreted results, and wrote the manuscript. H.B. and L.M.N. helped with the collection of patient data. M.D.V., S.H., and B.H.J. provided genotyping and imputation, data quality control, and coding. R.G. provided statistical analysis. W.T.U.V., B.G.H., H.J.V., T.L., R.K.W., and R.J.P. guided with the interpretation of the results and research design. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the manuscript for publication.

Open Research Badges

This article has earned an Open Materials badges for making publicly available the components of the research methodology needed to reproduce the reported procedure and analysis. All materials are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/6GP71D.

Supporting information

Fig S1‐S6

Table S1‐S10

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the study nurses, technicians, laboratory staff, and clinicians for the collaboration. We acknowledge Prof. Cisca Wijmenga, Prof. Alexandra Zhernakova, Prof. Jingyuan Fu, Prof. Gerard Dijkstra, and Prof. Klaas Nico Faber for their scientific guidance, and Dr. Serena Sanna, Dr. Arnau Vich Vila, Dr. Alexander Kurilshikov, and Valerie Collij for their statistical guidance. Yanni Li was supported by the China Scholarship Council. The work was supported by a grant from Stichting Louise Vehmeijer (Amsterdam).

Statement of prior presentation: Part of this data was presented at the 19th Congress of the European Society for Organ Transplantation, Copenhagen, Denmark, 15–18 September 2019.

E.A.M Festen and V.E. de Meijer contributed equally to this study.

Contributor Information

Yanni Li, Email: yanni19907300@gmail.com.

Lianne M. Nieuwenhuis, Email: l.m.nieuwenhuis@umcg.nl.

Michiel D. Voskuil, Email: m.d.voskuil@umcg.nl.

Ranko Gacesa, Email: rgacesa@gmail.com.

Shixian Hu, Email: dhu.sxhu@hotmail.com.

Bernadien H. Jansen, Email: b.h.jansen@umcg.nl

Werna T. U. Venema, Email: w.t.c.uniken.venema@umcg.nl.

Bouke G. Hepkema, Email: b.g.hepkema@umcg.nl

Hans Blokzijl, Email: h.blokzijl@umcg.nl.

Henkjan J. Verkade, Email: h.j.verkade@umcg.nl

Ton Lisman, Email: j.a.lisman@umcg.nl.

Rinse K. Weersma, Email: r.k.weersma@umcg.nl.

Robert J. Porte, Email: r.j.porte@umcg.nl.

Eleonora A. M. Festen, Email: e.a.m.festen@umcg.nl.

Vincent E. de Meijer, Email: v.e.de.meijer@umcg.nl.

REFERENCES

- 1. Akamatsu N, Sugawara Y, Nakazawa A, et al. Hemostatic status in liver transplantation: association between preoperative procoagulants/anticoagulants and postoperative hemorrhaging/thrombosis. Liver Transplant. 2015;21(2):258‐265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ayala R, Martínez‐López J, Cedena T, et al. Recipient and donor thrombophilia and the risk of portal venous thrombosis and hepatic artery thrombosis in liver recipients. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11(1):130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Li Y, Nieuwenhuis LM, Werner MJM, et al. Donor tobacco smoking is associated with postoperative thrombosis after primary liver transplantation. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(10):2590‐2600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mourad MM, Liossis C, Gunson BK, et al. Etiology and management of hepatic artery thrombosis after adult liver transplantation. Liver Transplant. 2014;20(6):713‐723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zanetto A, Rodriguez‐Kastro K‐I, Germani G, et al. Mortality in liver transplant recipients with portal vein thrombosis – an updated meta‐analysis. Transpl Int. 2018;31(12):1318‐1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Potze W, Porte RJ, Lisman T. Management of coagulation abnormalities in liver disease. Exp RevGastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;9(1):103‐114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nagalla S, Bray PF. Personalized medicine in thrombosis: back to the future. Blood. 2016;127(22):2665‐2671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Trégouët D‐A, Heath S, Saut N, et al. Common susceptibility alleles are unlikely to contribute as strongly as the FV and ABO loci to VTE risk: results from aGWAS approach. Blood. 2009;113(21):5298‐5303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lindström S, Wang L, Smith EN, et al. Genomic and transcriptomic association studies identify 16 novel susceptibility loci for venous thromboembolism. Blood. 2019;134(19):1645‐1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Germain M, Chasman DI, De Haan H, et al. Meta‐analysis of 65,734 individuals identifies TSPAN15 and SLC44A2 as two susceptibility loci for venous thromboembolism. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;96(4):532‐542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hinds DA, Buil A, Ziemek D, et al. Genome‐wide association analysis of self‐reported events in 6135 individuals and 252 827 controls identifies 8 loci associated with thrombosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;25(9):1867‐1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Klarin D, Emdin CA, Natarajan P, Conrad MF, Kathiresan S. Genetic analysis of venous thromboembolism in UK biobank identifies the ZFPM2 locus and implicates obesity as a causal risk factor. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2017;10(2):e001643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Desch K, Ozel AB, Halvorsen M, et al. Whole exome sequencing identifies rare variants in STAB2 associated with venous thromboembolic disease. Blood. 2020;136(5):533‐541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Klarin D, Busenkell E, Judy R, et al. Genome‐wide association analysis of venous thromboembolism identifies new risk loci and genetic overlap with arterial vascular disease. Nat Genet. 2019;51(11):1574‐1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. O’Brien RP, Phelan PJ, Conroy J, et al. A genome‐wide association study of recipient genotype and medium‐term kidney allograft function. Clin Transplant. 2013;27(3):379‐387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Little J, Higgins JPT, Ioannidis JPA, et al. STrengthening the REporting of genetic association studies (STREGA)‐an extension of the strobe statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(2):e1000022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. IC. A post‐Imputation data checking program. Affymetrix Web site. https://www.well.ox.ac.uk/~wrayner/tools/Post‐Imputation.html.

- 18. Morange PE, Suchon P, Trégouët DA. Genetics of venous thrombosis: Update in 2015. Thromb Haemost. 2015;114(5):910‐919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kupcinskiene K, Murnikovaite M, Varkalaite G, et al. Thrombosis related ABO, F5, MTHFR, and FGG gene polymorphisms in morbidly obese patients. Dis Markers. 2016;2016:7853424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gemmati D, Vigliano M, Burini F, et al. Coagulation factor XIIIA (F13A1): novel perspectives in treatment and pharmacogenetics. Curr Pharm Des. 2016;22(11):1449‐1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bruzelius M, Bottai M, Sabater‐Lleal M, et al. Predicting venous thrombosis in women using a combination of genetic markers and clinical risk factors. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(2):219‐227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Germain M, Saut N, Greliche N, et al. Genetics of venous thrombosis: insights from a new genome wide association study. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e25581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Deguchi H, Shukla M, Hayat M, Torkamani A, Elias DJ, Griffin JH. Novel exomic rare variants associated with venous thrombosis. Br J Haematol. 2020;190(5):783‐786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tang W, Teichert M, Chasman DI, et al. A genome‐wide association study for venous thromboembolism: the extended cohorts for heart and aging research in genomic epidemiology (CHARGE) consortium. Genet Epidemiol. 2013;37(5):512‐521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Purcell S, Neale B, Todd‐Brown K, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole‐genome association and population‐based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(3):559‐575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McLaren W, Pritchard B, Rios D, Chen Y, Flicek P, Cunningham F. Deriving the consequences of genomic variants with the Ensembl API and SNP effect predictor. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(16):2069‐2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rentzsch P, Witten D, Cooper GM, Shendure J, Kircher M. CADD: predicting the deleteriousness of variants throughout the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D886‐D894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fritsche LG, Igl W, Bailey JNC, et al. A large genome‐wide association study of age‐related macular degeneration highlights contributions of rare and common variants. Nat Genet. 2016;48(2):134‐143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Uhlén M, Fagerberg L, Hallström BM, et al. Tissue‐based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015;347(6220):1260419. 10.1126/science.1260419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Davies M, Nowotka M, Papadatos G, et al. ChEMBL web services: streamlining access to drug discovery data and utilities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(W1):W612‐W620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Choi SW, O’Reilly PF. PRSice‐2: polygenic risk score software for biobank‐scale data. Gigascience. 2019;8(7):giz082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. GCTA: a tool for genome‐wide complex trait analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88(1):76‐82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Köhler S, Carmody L, Vasilevsky N, et al. Expansion of the human phenotype ontology (HPO) knowledge base and resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D1018‐D1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pruim RJ, Welch RP, Sanna S, et al. LocusZoom: regional visualization of genome‐wide association scan results. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(18):2336–2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Soria JM, Morange P‐E, Vila J, et al. Multilocus genetic risk scores for venous thromboembolism risk assessment. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(5):e001060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pereboom ITA, Adelmeijer J, Van Der Steege G, Van Den Berg AP, Lisman T, Porte RJ. Prothrombotic gene polymorphisms: possible contributors to hepatic artery thrombosis after orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2011;92(5):587‐593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dunn TB, Linden MA, Vercellotti GM, Gruessner RWG. Factor V Leiden and hepatic artery thrombosis after liver transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2006;20(1):132‐135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Leroy‐Matheron C, Duvoux C, Van Nhieu JT, Leroy K, Cherqui D, Gouault‐Heilmann M. Activated protein C resistance acquired through liver transplantation and associated with recurrent venous thrombosis. J Hepatol. 2003;38(6):866‐869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gillis S, Lebenthal A, Pogrebijsky G, Levy Y, Eldor A, Ahmed E. Severe thrombotic complications associated with activated protein C resistance acquired by orthotopic liver transplantation. Haemostasis. 2000;30(6):316–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hirshfield G, Collier JD, Brown K, et al. Donor factor V leiden mutation and vascular thrombosis following liver transplantation. Liver Transplant Surg. 1998;4(1):58‐61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schuetze SM, Linenberger M. Acquired Protein S deficiency with multiple thrombotic complications after orthotopic liver transplant. Transplantation. 1999;67(10):1366‐1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kitchens WH, Yeh H, Van Cott EM, et al. Protein S deficiency in a living liver donor. Transpl Int. 2012;25(2):e23‐e26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Naymagon L, Tremblay D, Facciuto M, Rudow DL, Schiano T. The utility of thrombophilia and hematologic screening in live liver donation. Clin Transpl. 2020:e14159. 10.1111/ctr.14159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Panayiotou C, Solaroli N, Karlsson A. The many isoforms of human adenylate kinases. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;49:75‐83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lanning NJ, Looyenga BD, Kauffman AL, et al. A mitochondrial RNAi screen defines cellular bioenergetic determinants and identifies an adenylate kinase as a key regulator of ATP levels. Cell Rep. 2014;7(3):907‐917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Randriamboavonjy V, Isaak J, Frömel T, et al. AMPK α2 subunit is involved in platelet signaling, clot retraction, and thrombus stability. Blood. 2010;116(12):2134‐2140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Greliche N, Germain M, Lambert JC, et al. A genome‐wide search for common SNP x SNP interactions on the risk of venous thrombosis. BMC Med Genet. 2013;14(1):36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bondjers C, Kalén M, Hellström M, et al. Transcription profiling of platelet‐derived growth factor‐B‐deficient mouse embryos identifies RGS5 as a novel marker for pericytes and vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Pathol. 2003;162(3):721‐729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Arnold C, Feldner A, Pfisterer L, et al. RGS 5 promotes arterial growth during arteriogenesis. EMBO Mol Med. 2014;6(8):1075‐1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Olsen RKJ, Andresen BS, Christensen E, Bross P, Skovby F, Gregersen N. Clear relationship between ETF/ETFDH genotype and phenotype in patients with multiple acyl‐CoA dehydrogenation deficiency. Hum Mutat. 2003;22(1):12‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig S1‐S6

Table S1‐S10

Supplementary Material