Abstract

The ability to measure the concentration of metabolites in biological samples is important, both in the clinic and for home diagnostics. Here we present a nanopore‐based biosensor and automated data analysis for quantification of thiamine in urine in less than a minute, without the need for recalibration. For this we use the Cytolysin A nanopore and equip it with an engineered periplasmic thiamine binding protein (TbpA). To allow fast measurements we tuned the affinity of TbpA for thiamine by redesigning the π‐π stacking interactions between the thiazole group of thiamine and TbpA. This substitution resulted furthermore in a marked difference between unbound and bound state, allowing the reliable discrimination of thiamine from its two phosphorylated forms by residual current only. Using an array of nanopores, this will allow the quantification within seconds, paving the way for next‐generation single‐molecule metabolite detection systems.

Keywords: bayesian, biosensors, nanopores, nanotechnology, thiamine

Quantification of small molecules in biological samples is challenging. Using the concentration‐dependent current fluctuations elicited by a thiamine binding protein inside a ClyA nanopore, we show the automated quantification of thiamine in urine in less than a minute. By swapping the internal biosensor, this principle can be applied for the development of multiple next‐generation home‐diagnostic small‐molecule sensors.

Introduction

Thiamine (ThOH) is an essential vitamin (vitamin B1), which is important for human metabolism and cognitive functions.[ 1 , 2 ] Deficiency of thiamine can lead to a range of non‐specific symptoms, delaying diagnosis of its underlying cause and thereby potentially leading to permanent neural degeneration. The clinical relevance is not only limited to beriberi‐related diseases (e.g. Wernicke encephalopathy and Korsakoff syndrome),[ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ] but research has also highlighted thiamine as a potential biomarker for certain neurodegenerative diseases.[ 7 , 8 , 9 ] The detection of thiamine is commonly performed using liquid chromatography, which requires a relatively high level of expertise and is time‐consuming. Therefore, a cheap, fast, and specific detection system, enabling the quantification of thiamine in easily accessible bodily fluids, such as urine, may satisfy an unmet medical need.

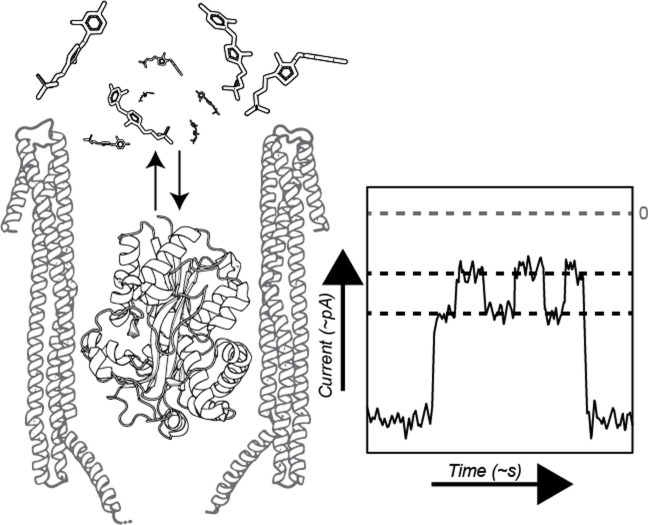

Nanopores offer new ways to quantify biomolecules while being readily interfaceable with electronic devices, as electrical signals are read out directly. Small nanopores have been successfully used for DNA‐sequencing[ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ] as well as detecting amino acids,[ 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 ] and, once equipped with organic adapters, to detect small‐molecule analytes.[ 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 ] Larger nanopores, such as a Cytolysin A (ClyA‐AS, [43] Figure 1 A) permit using protein adapters for the detection of a variety of ligands.[ 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 ] Interestingly, the environment of these large nanopores is not dissimilar from bulk, [49] and allows to perform single‐molecule enzymological studies.[ 50 , 51 , 52 ] Nanopores can measure small molecules directly with high sensitivity. However, even though rich electrical signals can be obtained through nanopore measurements,[ 53 , 54 ] the lack of selectivity complicates the identification of small molecules in biological samples. Substrate binding proteins can be highly selective. Thus, the combination of sensitivity of a nanopore with the selectivity of a substrate binding protein allows the detection and quantification of metabolites in complex samples. [44]

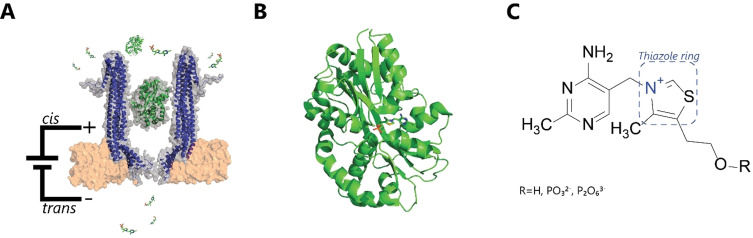

Figure 1.

Nanopore‐based thiamine sensor. A) Representation of the experimental setup with the Cytolysin A (ClyA‐AS, blue) nanopore hosting the thiamine‐binding protein (TbpA, green, PDB: 2QRY) and free thiamine monophosphate. The ClyA‐TbpA sensor pair is embedded within a lipid bilayer (orange) B) Enlarged TbpA with bound thiamine monophosphate (PDB: 2QRY). C) Chemical structure of thiamine and its phosphorylated derivates.

Here we use the periplasmic thiamine binding protein (TbpA, Figure 1 B), which has a specific binding affinity to thiamine (Figure 1 C). [45] We developed a mutant of TbpA that displays fast transitions between its apo and bound states and allows distinguishing thiamine from its phosphorylated derivatives. Finally, we develop an algorithm to automatically quantify the concentration of thiamine in human urine in less than a minute using only a single nanopore.

Results and Discussion

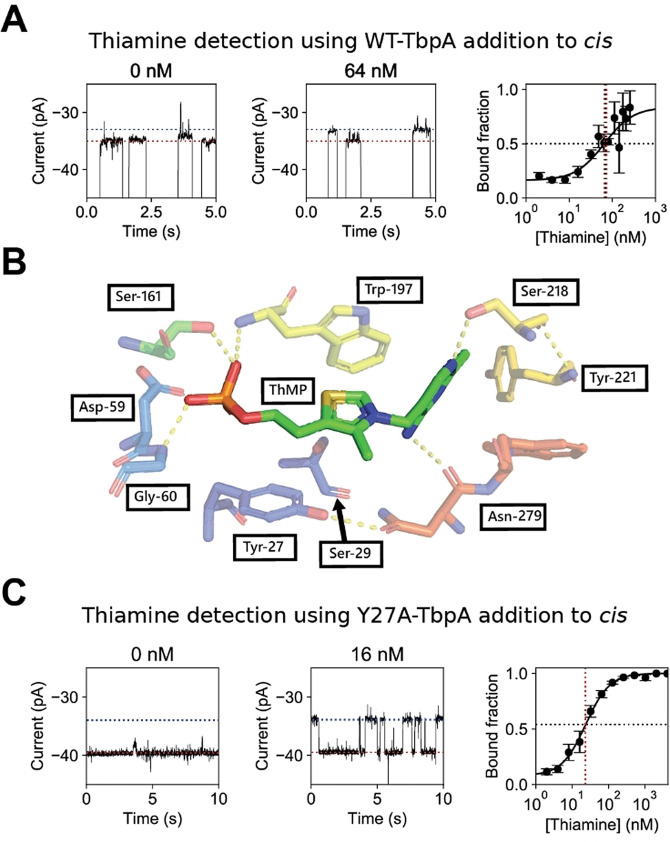

The entry of WT‐TbpA (15 nM, added to the cis compartment) to ClyA‐AS nanopores (−45 mV, 150 mM NaCl, 15 mM Tris.HCl, pH 7.5) was observed as a decrease in the ionic current (IB ) in respect to the open pore current (Io ) with a dwell time (τ) of 3±1 s (N=10, n=573, where N is the number of nanopores used and n the number of individual protein blockades analyzed). The resulting residual current percentage (Ires %=IB / Io x 100, where IB is the current during an event, for example, a protein blockade) of the unbound apo‐protein [Ires %(apo)] was 49.0±0.6 % (N=3, n=398). Furthermore, we observed non‐active blockades (i.e. blockades that did not respond to the addition of thiamine, see later) with a residual current of 59.1±0.7 % (N=4, n=160) and more rarely other levels, which we attribute mainly to misfolded proteins and impurities (Supporting Information, Figure 1). The addition of 4 μM thiamine to the cis compartment reduced the residual current of the protein blockades [ΔIres %(thiamine)=3.1±0.6 %, N=4, n=114)]. Transitions were observed only rarely between the apo and thiamine‐bound form of WT‐TbpA, suggesting a tight binding of the ligands to the protein (Supporting Information, Figure 2). The number of events with residual currents corresponding to thiamine‐bound levels relative to the number of events corresponding to apo‐levels was directly proportional to the concentration of thiamine added to the cis compartment (Figure 2 A). The apparent dissociation constant (Kd app) for thiamine binding to WT‐TbpA could then be calculated by fitting a Hill‐Langmuir equation [Eq. 1] to the concentration dependency of the fraction of Ires %(apo) blockades.

| (1) |

Figure 2.

Electrical detection of thiamine. A) Representative traces (left and middle) for wild‐type thiamine binding protein (WT‐TbpA, 15 nM), in the presence of thiamine, where thiamine and protein were added to the cis compartment. The red dotted line represents the apo current and the blue dotted line represents the ligand‐bound current. The right panel indicates the observed bound fraction set against the thiamine concentration. The solid black line represents a fit of the corrected Hill equation. The black dashed and red dashed line indicate the apparent dissociation constant (Kd app) in bound fraction and thiamine concentration, respectively. B) Binding site of WT‐TbpA with thiamine monophosphate adapted from Soriano et al. [56] C) Representative traces for an expansion of a Y27A thiamine binding protein (Y27A‐TbpA, 15 nM) blockade in absence and presence of 16 nM thiamine added to cis. The red dotted line represents the apo current and the blue dotted line represents the ligand bound current. The observed bound fraction set against the thiamine concentration is shown on the right. The solid black line represents a fit of the corrected Hill equation. The black dashed and red dashed line indicate the apparent dissociation constant (Kd app) in bound fraction and thiamine concentration, respectively. All measurements were performed on an Axon 200B amplifier with a 1550B digitizer in 150 mM NaCl supplemented with 15 mM Tris.HCl buffer (pH 7.5), at −45 mV at a sampling frequency of 10 kHz filtered to 2 kHz using a Bessel filter, all traces were digitally filtered to 100 Hz using a Gaussian filter.

Where θ is the bound fraction observed given the ligand concentration [L], a is the bound fraction in absence of substrate and represents intrinsic closing, b the normalization factor, [55] Kd app the apparent dissociation constant and n represents the Hill coefficient.

Interestingly, in the absence of thiamine 16±3 % of WT‐TbpA blockades showed a residual current corresponding to the bound configuration, indicating that, as observed for other substrate binding proteins, [45] TbpA intrinsically closes without the substrate. We calculated an apparent dissociation constant (Kd app) for thiamine binding to WT‐TbpA of 67±5 nM, and found the Hill coefficient to be one, indicating that, as expected, there is no cooperative binding. The Kd app was roughly ten times higher than previously reported in ensemble studies (Kd of 3.8±0.3 nM). [56] Since the concentration of the protein adaptor (15 nM) is similar to the amount of thiamine added to the cis solution (2 nM–4 μM), most likely, the discrepancy between the two Kd values reflects the uncertainty on the concentration of the free ligand in the cis solution. Surprisingly, the addition of thiamine to the trans solution did not elicit additional current blockades, suggesting that the diffusion of thiamine from trans to cis might be impaired by the position of the wild‐type protein adaptor inside the nanopore.

To determine thiamine concentration quickly and reliably, hundreds of events in a short period of time need to be gathered. Hence, we sought to redesign the WT‐TbpA adaptor to obtain a sensor that is capable of rapid switching between its unbound and bound state. The thiazole ring of thiamine monophosphate is sandwiched between residues Tyr27 and Trp197 of TbpA (Figure 2 B). [56] Thus, we reasoned that substitution of the tyrosine at position 27 with an alanine (Y27A‐TbpA) would reduce π–π stacking interactions between TbpA and thiamine, therefore increasing the k off.

Y27A‐TbpA (15 nM, cis, −45 mV, 150 mM NaCl, 15 mM Tris⋅HCl at pH 7.5) active blockades were markedly shallower than WT‐TbpA active blockades, (Y27A‐TbpA−Ires %(apo)=55.3±0.7 %, τ=3±1 s, N=3, n=236, Figure 2 C, Supporting Information, Figures 3 and 4), possibly reflecting the binding of the protein to a higher residence site inside the nanopore. Two residence sites were observed previously also for thrombin. [43] Y27A‐TbpA was intrinsically closed 8±3 % of the time providing a limit of detection at 3σ of 4.62±0.02 nM, calculated from the intrinsic closing at 3σ (17 % closed). Upon addition of 4 μM thiamine to the cis side, we observed further rapid current blockades raising from the Ires %(apo) level, showing a ΔIres %(thiamine) of 6.9±0.6 % (N=12, n=363, Supporting Information, Figure 5). The latter is more than twice the value measured for WT‐TbpA. The closed state of Y27A‐TbpA [Ires %(thiamine)=48.4±0.9 %] is similar to the closed state of WT‐TbpA [Ires %(thiamine)=45.9±0.8 %], suggesting that, upon binding of thiamine, Y27A‐TbpA might assume a lower position inside the ClyA‐AS pore. Conveniently, also the addition of thiamine to the trans chamber induced thiamine events (Supporting Information, Figure 6), further indicating that apo‐Y27A‐TbpA is likely positioned at a higher binding site than WT‐TbpA, that allows the diffusion of the thiamine through the nanopore. Hence, Y27A‐TbpA allows measuring concentration dependency from either side of the nanopore. We used an ad hoc algorithm to detect all events. We report the Kd app value as estimated from the Hill curve fitted to the bound fraction [Eq. (1), Supporting Information] and calculated the on‐rate and off‐rate from the linear correlation between thiamine concentration and event rate (Supporting Information, Figure 7), resulting in the binding constants: K d app(cis)=23.1±0.1 nM, k on(cis)=69±9 μM−1 s−1, k off(cis)=1.8±0.3 s−1 and Kd app(trans)=91.1±0.4 nM, k on(trans)=14±3 μM−1 s−1, k off(trans)=1.7±0.1 s−1 and a Hill coefficient of 1.

The 4‐fold difference in the apparent Kd and k on rates between cis and trans can be explained partially by the different concentration of free thiamine in solution (vide supra) and by the positive charge of thiamine. Under an applied potential of −45 mV, the electrophoretic force created by the negative trans electrode promotes the entry of the positively charged thiamine from cis to trans while reducing translocation from trans to cis. In addition, the trans entry of the pore is smaller than the cis entry, reducing accessibility of the analyte towards the protein, in turn decreasing the apparent Kd . Furthermore, the orientation of the protein within the nanopore might also play a role. Overall, Y27A‐TbpA is more suitable as a sensor than WT‐TbpA because it allows faster measurement of thiamine, a larger dynamic range, and allows thiamine capture from trans.

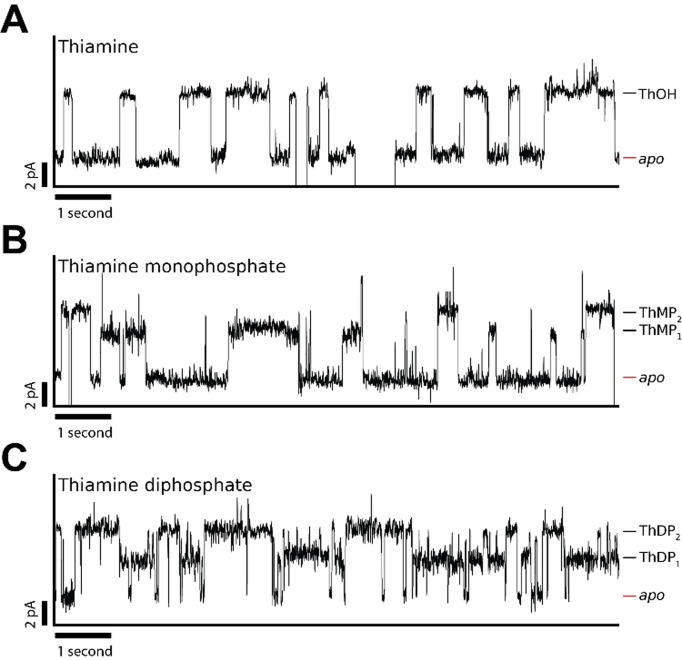

Phosphorylation of the hydroxy group of thiamine (ThOH) can form thiamine mono‐and diphosphate derivatives. [57] The diphosphorylated form (ThDP), is an essential co‐factor in many organisms. [58] In contrast, thiamine monophosphate (ThMP) is not active as a co‐factor. However, it has been suggested that ThMP may facilitate transfer across cellular membranes. [59] Both ThMP and ThDP are synthesized from ThOH. It was previously reported that WT‐TbpA can bind ThOH and its phosphorylated derivates at near‐equimolar Kd . [56] As both ThDP and ThMP are present in some biological fluids, we sought to detect these derivates with the Y27A‐TbpA. The binding of ThMP and ThDP induced specific current events to Y27A‐TbpA blockades (Figure 3). Upon the addition of 0.1 μM ThMP to the cis side, we observed two kinds of bound events with a ΔIres %(ThMP1) of 4.8±0.2 % (N=3, n=236) and with a k off(ThMP1) of 2.3±0.4 s−1 as well as ΔIres %(ThMP2) of 7.3±0.3 % (N=3, n=395) with a k off(ThMP2) of 2.0±0.2 s−1. The capture frequency (an approximate k on) for both events was 16±4 μM−1 s−1 (0.1 μM ThMP). Similarly, at an approximated Kd app(cis) of 2 μM ThDP, we observed one type of event with an ΔIres %(ThDP1) of 4.0±0.1 % (N=3, n=720) with a k off(ThDP1) of 2.9±0.4 s−1, and a second type of event with an ΔIres%(ThDP2) of 7.2±0.1 % (N=3 and n=853) with a k off(ThDP2) of 1.7±0.3 s−1. The capture frequency for both events was 6.5±3 μM−1 s−1 (2 μM ThDP). The off‐rates of both ThMP1‐2 and ThDP1‐2 were similar to the off‐rate of thiamine. (Figure 3). Thus, we hypothesized that the additional events may correspond to thiamine rather than ThMP or ThDP. To exclude this possibility, we performed anion‐exchange chromatography, directly prior to nanopore experiments as well as again after nanopore experiments, to make sure no hydrolysis had occurred. We found no evidence of thiamine in the samples. In addition, we performed the same experiments after letting the samples incubate overnight at 37 °C and observed no significant hydrolysis (Supporting Information, Figure 8). Moreover, we subjected each sample to mass spectrometry, and we did not observe thiamine in the phosphorylated samples (Supporting Information, Figure 9). The most likely explanation, therefore, is that while thiamine binds to a singular Y27A‐TbpA conformation, ThMP and ThDP may bind to two conformations. It was also previously reported that the thiazole ring of ThOH has to turn in order to form π‐π stacking interaction with Tyr27 and Trp197, while the phosphate groups on ThMP and ThDP disallow such a rearrangement. [56] The difference between the off‐rates of ThMP1 and ThDP1 bound states is possibly due to hydrogen bonds formed between the ThDP β‐phosphate group with the side chains of Asp28 and Ser29. [56] It might also be possible that the differences between the thiamine derivatives is caused by a different position Y27A‐TbpA assumes in the nanopore as a consequence of the additional charges in the phosphorylated substrates. We previously observed that manipulation of the dipole of a confined binding protein in ClyA‐AS, by means of an addition of a negatively charged point mutation, may cause a similar effect. [48] Hence, despite the analysis of the thiamine phosphate derivatives is challenging, our data shows that ThOH, ThMP and ThDP can be distinguished by nanopore currents.

Figure 3.

Detection of thiamine (ThOH), thiamine monophosphate (ThMP) and thiamine diphosphate (ThDP) using Y27A‐Thiamine binding protein (Y27A‐TbpA). Representative blockades induced by (A) 16 nM ThOH added to cis (B) 0.1 μM ThMP added to cis (C) 2 μM ThDP added to cis. All data was recorded in 150 mM NaCl, 15 mM Tris.HCl, pH 7.5 using a sampling frequency of 10 kHz and an analogue Bessel‐filter of 2 kHz and an applied bias −45 mV. Traces were filtered using a 100 Hz digital Gaussian filter.

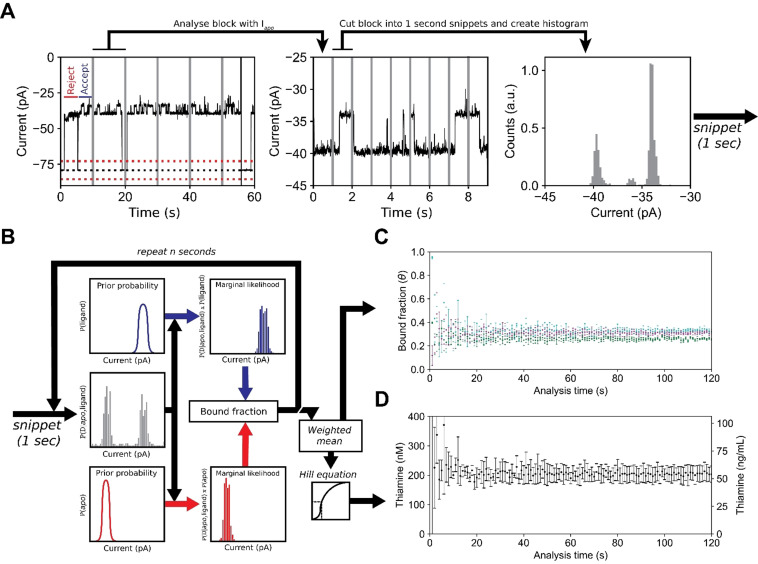

Next, we sought to develop an automated nanopore sensor that, upon addition of the sample, can determine the concentration of thiamine without further human intervention. We selected human urine, because it does not require invasive sampling and has a very low protein background. The primary form of thiamine found in urine is ThOH. [4] For automated data analyses we utilized a recursive event detection algorithm, which recognizes the protein blockades and ligand‐induced events in the data using a threshold search. The algorithm analyzes snippets of 10 seconds in real‐time. From each snippet a full‐point histogram is taken, and the open pore current identified by fitting a normal distribution around the expected value. Then, for events longer than 25 ms, a threshold search (3σ upper boundary of the Io , Figure 4 A) is performed in order to identify protein blockades (Figure 4 A). Each protein blockade is compared to expected value of the apo level and used for subsequent threshold analysis if this is not significantly different. From the latter, the start and end times are tabulated and the ligand events within each of these blockades are detected using a second threshold analysis. Start and end times of each ligand event are then tabulated (Figure 4 A).

Figure 4.

Real‐time detection of the thiamine (ThOH) concentration in a urine sample using Y27A‐Thiamine binding protein‐equipped ClyA‐AS nanopore. A) Current trace showing the capture of Y27A‐TbpA (blockades) by the ClyA‐AS nanopore. The trace is divided into snippets of 10 seconds and analysed for blockades. The blockades are further analysed and divided into snippets of 1 second. For each blockade snippet a histogram is created and used for subsequent analysis. The dotted black line represents the baseline current, and the red dashed lines represent the 3 σ thresholds. The vertical (grey) lines represent the snippets for blockade and bound fraction determination. B) Workflow for real‐time detection. A normalized histogram is created from 1 second (blockade) snippets and the bound fraction for each snippet is calculated. The ligand bound state is indicated in blue and the apo state is represented in red. The weighted mean of the bound fractions is calculated using the inverse slope in ligand concentration as weights. The thiamine concentration is determined from the Hill equation. C) Estimated bound fraction of three independent measurements where 3 % (cyan) or 5 % (magenta/green) of urine were added to the cis compartment. The analysis time is the number of snippets used In (B) (1 s=1 snippet). D) The weighted mean thiamine concentration in nanomolar and ng mL−1 estimated from three independent measurements, see (C).

From each tabulated snippet, protein blockades are extracted and combined. The resulting combined trace, which only contains the signal from protein blockades, is further divided into snippets of one second and a normalized full‐point histogram of each snippet is created. Each bin of the normalized histograms is then multiplied with the prior probability of the ligand state and the prior probability of the apo state to create two histograms: one for the marginal likelihood of the apo state and one for the liganded state (Figure 4 B). The fraction of the likelihood is then used as the bound fraction in each 1‐second snippet. The estimated bound fractions for each 1‐second snippet are weighted by the determinate error of the Hill equation and averaged to obtain the bound fraction. Using the Hill equation, the bound fraction is used to calculate the concentration of thiamine. We show that this workflow will converge into the true bound fraction (Supporting Information).

In healthy human adults, ThOH is generally found in tens to hundreds of ng mL−1 (nanomolar range), [60] which is near the K d app(cis) we measured for the Y27A‐TbpA mutant. Hence, we used the automated real‐time data analysis to measure the thiamine concentration in urine from a young adult male, using a palm‐sized eOne HS amplifier. We added a final concentration of 3 % (v/v) human urine samples to the cis solution containing Y27A‐TbpA (15 nM), 150 mM NaCl, 15 mM Tris⋅HCl at pH 7.5 using a single dodecameric ClyA‐AS nanopore. By using the same calibration curve described in Figure 2 C, the automatic analysis established a thiamine concentration in the urine sample of 68±4 ng mL−1 (N=3), which is not significantly different from the HPLC‐MS result at 3σ (57±1 ng mL−1). To test the limits of our system, we performed automatic (real‐time) analysis by resampling obtained traces (Figure 4 C/D). We show that the error converges after approximately 20 seconds of a concatenated protein blockade time, indicating that using a single nanopore an accurate measurement takes at least 20 seconds. Taken together, we demonstrate a nanopore‐sensor for the rapid, automated, and direct analysis of thiamine in samples of urine, without the need of sample preparation.

Conclusion

Nanopore biosensors have emerged as potential low‐cost candidates to rapidly detect biologically relevant molecules in biological samples. Recent contributions have shown the capabilities of nanopore‐coupled binding proteins as a way to specifically detect small molecules in biological fluids.[ 44 , 45 , 47 ] In this work, we have shown that the affinity of Escherichia coli TbpA toward thiamine can be tuned by reducing π‐π stacking interactions between the thiazole group of thiamine and TbpA, by substitution of a single residue, Y27A. This modification enhanced the nanopore signal, which allowed the quantification and detection of thiamine and its phosphorylated derivates. We have also developed an algorithm that allowed to determine the concentration of thiamine in human urine without requiring an operator in a matter of tens of seconds. It also demonstrates that the sensor is not impaired by the thousands of different molecules present in urine. [61] Because the protein sensor element (Y27A‐TbpA, in cis) can be separated from the sample (trans), this technology may also be applicable to samples containing significant quantities of protein, such as blood. This is because large molecules cannot pass the narrow trans constriction and must overcome a comparable strong electroosmotic flow under negative applied potential. Compared to other amperometric sensors, this approach does not require calibration, because the signal from inactive proteins is ignored. Since hundreds of proteins exist that can detect molecules with high selectivity, nanopores fitted with internal protein sensors provide a starting point for new home diagnostic metabolite sensors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Acknowledgements

F.L.R.L. was supported by the research program of the Foundation for Fundamental Research on Matter (FOM), which is part of the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). N.S.G. and G.M. were supported by the European Research Council (DeE‐Nano, 726151). C.W. was supported by a NWO Veni (722.017.010).

F. L. R. Lucas, T. R. C. Piso, N. J. van der Heide, N. S. Galenkamp, J. Hermans, C. Wloka, G. Maglia, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 22849.

Dedicated to Emma, Thomas, and Lena Wloka

Contributor Information

Dr. Carsten Wloka, Email: c.wloka@rug.nl.

Prof. Dr. Giovanni Maglia, Email: g.maglia@rug.nl.

References

- 1. Bender D. A., Proc. Nutr. Soc. 1999, 58, 427–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Frank R. A. W., Leeper F. J., Luisi B. F., Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2007, 64, 892–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wai J. M., Aloezos C., Mowrey W. B., Baron S. W., Cregin R., Forman H. L., J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2019, 99, 117–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Whitfield K. C., Bourassa M. W., Adamolekun B., Bergeron G., Bettendorff L., Brown K. H., Cox L., Fattal-Valevski A., Fischer P. R., Frank E. L., Hiffler L., Hlaing L. M., Jefferds M. E., Kapner H., Kounnavong S., Mousavi M. P. S., Roth D. E., Tsaloglou M., Wieringa F., Combs G. F., Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2018, 1430, 3–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Salloum S., Goenka A., Mezoff A., Oxford Med. Case Rep. 2018, 2018, omy091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fattal-Valevski A., Pediatrics 2005, 115, e233-e238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gibson G. E., Hirsch J. A., Fonzetti P., Jordan B. D., Cirio R. T., Elder J., Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2016, 1367, 21–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rodríguez J.-L., Qizilbash N., López-Arrieta J., Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2001, CD001498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. vinh quôc Lu′o′ng K., Nguyên L. T. H., Am. J. Alzheimer's Dis. Other Dementiasr. 2011, 26, 588–598. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wloka C., Mutter N. L., Soskine M., Maglia G., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 12494–12498; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 12682–12686. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bayley H., Clin. Chem. 2015, 61, 25–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Butler T. Z., Pavlenok M., Derrington I. M., Niederweis M., Gundlach J. H., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 20647–20652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stoddart D., Heron A. J., Mikhailova E., Maglia G., Bayley H., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 7702–7707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Maglia G., Heron A. J., Stoddart D., Japrung D., Bayley H., Methods Enzymol. 2010, 475, 591–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bhattacharya S., Yoo J., Aksimentiev A., ACS Nano 2016, 10, 4644–4651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cao C., Ying Y.-L., Hu Z.-L., Liao D.-F., Tian H., Long Y.-T., Nat. Nanotechnol. 2016, 11, 713–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sutherland T. C., Long Y.-T., Stefureac R.-I., Bediako-Amoa I., Kraatz H.-B., Lee J. S., Nano Lett. 2004, 4, 1273–1277. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Movileanu L., Schmittschmitt J. P., Scholtz J. M., Bayley H., Biophys. J. 2005, 89, 1030–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cao C., Cirauqui N., Marcaida M. J., Buglakova E., Duperrex A., Radenovic A., Dal Peraro M., Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Restrepo-Pérez L., Wong C. H., Maglia G., Dekker C., Joo C., Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 7957–7964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Huang G., Voet A., Maglia G., Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li S., Cao C., Yang J., Long Y.-T., ChemElectroChem 2019, 6, 126–129. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Restrepo-Pérez L., Huang G., Bohländer P., Worp N., Eelkema R., Maglia G., Joo C., Dekker C., Restrepo-Perez L., Huang G., Bohländer P., Worp N., Eelkema R., Maglia G., Joo C., Dekker C., ACS Nano 2019, 13, 13668–13676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ouldali H., Sarthak K., Ensslen T., Piguet F., Manivet P., Pelta J., Behrends J. C., Aksimentiev A., Oukhaled A., Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 176–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lucas F. L. R., Sarthak K., Lenting E. M., Coltan D., van der Heide N. J., Versloot R. C. A., Aksimentiev A., Maglia G., ACS Nano 2021, 15, 9600—9613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wilson J., Sarthak K., Si W., Gao L., Aksimentiev A., ACS Sens. 2019, 4, 634–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Si W., Aksimentiev A., ACS Nano 2017, 11, 7091–7100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Robertson J. W. F., Rodrigues C. G., Stanford V. M., Rubinson K. A., Krasilnikov O. V., Kasianowicz J. J., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 8207–8211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mohammad M. M. M., Movileanu L., Eur. Biophys. J. 2008, 37, 913–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.See Ref. [16].

- 31. Asandei A., Schiopu I., Chinappi M., Seo C. H., Park Y., Luchian T., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 13166–13179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chavis A. E., Brady K. T., Hatmaker G. A., Angevine C. E., Kothalawala N., Dass A., Robertson J. W. F., Reiner J. E., ACS Sens. 2017, 2, 1319–1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Asandei A., Rossini A. E., Chinappi M., Park Y., Luchian T., Langmuir 2017, 33, 14451–14459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Robertson J. W. F., Reiner J. E., Proteomics 2018, 18, 1800026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Piguet F., Ouldali H., Pastoriza-Gallego M., Manivet P., Pelta J., Oukhaled A., Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gu L. Q., Braha O., Conlan S., Cheley S., Bayley H., Nature 1999, 398, 686–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li X., Lee K. H., Shorkey S., Chen J., Chen M., ACS Nano 2020, 14, 1727–1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sanchez-Quesada J., Ghadiri M. R., Bayley H., Braha O., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 11757–11766. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Boersma A. J., Brain K. L., Bayley H., ACS Nano 2012, 6, 5304–5308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Boersma A. J., Bayley H., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 9606–9609; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 9744–9747. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cheley S., Gu L.-Q., Bayley H., Chem. Biol. 2002, 9, 829–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Braha O., Webb J., Gu L.-Q., Kim K., Bayley H., ChemPhysChem 2005, 6, 889–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Soskine M., Biesemans A., De Maeyer M., Maglia G., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 13456–13463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Galenkamp N. S., Soskine M., Hermans J., Wloka C., Maglia G., Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zernia S., van der Heide N. J., Galenkamp N. S., Gouridis G., Maglia G., ACS Nano 2020, 14, 2296–2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Soskine M., Biesemans A., Moeyaert B., Cheley S., Bayley H., Maglia G., Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 4895–4900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Soskine M., Biesemans A., Maglia G., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 5793–5797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Van Meervelt V., Soskine M., Singh S., Schuurman-Wolters G. K., Wijma H. J., Poolman B., Maglia G., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 18640–18646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Willems K., Ruić D., Lucas F. L. R., Barman U., Verellen N., Hofkens J., Maglia G., Van Dorpe P., Nanoscale 2020, 12, 16775–16795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Willems K., Ruić D., Biesemans A., Galenkamp N. S. N., Van Dorpe P., Maglia G., ACS Nano 2019, 13, 9980–9992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Galenkamp N. S., Biesemans A., Maglia G., Nat. Chem. 2020, 12, 481–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.N. S. Galenkamp, G. Maglia, bioRxiv 2020, 2020.04.14.040733.

- 53. Li M.-Y., Ying Y.-L., Yu J., Liu S.-C., Wang Y.-Q., Li S., Long Y.-T., JACS Au 2021, 1, 967–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Li M.-Y., Wang Y.-Q., Ying Y.-L., Long Y.-T., Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 10400–10404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gesztelyi R., Zsuga J., Kemeny-Beke A., Varga B., Juhasz B., Tosaki A., Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. 2012, 66, 427–438. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Soriano E. V., Rajashankar K. R., Hanes J. W., Bale S., Begley T. P., Ealick S. E., Biochemistry 2008, 47, 1346–1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Goyer A., Phytochemistry 2010, 71, 1615–1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ajjawi I., Rodriguez Milla M. A., Cushman J., Shintani D. K., Plant Mol. Biol. 2007, 65, 151–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Manzetti S., Zhang J., van der Spoel D., Biochemistry 2014, 53, 821–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dietary Reference Intakes for Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Pantothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline, National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., 1998. [PubMed]

- 61. Bouatra S., Aziat F., Mandal R., Guo A. C., Wilson M. R., Knox C., Bjorndahl T. C., Krishnamurthy R., Saleem F., Liu P., Dame Z. T., Poelzer J., Huynh J., Yallou F. S., Psychogios N., Dong E., Bogumil R., Roehring C., Wishart D. S., PLoS One 2013, 8, e73076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information