Abstract

Objective

Compassion has long been considered a cornerstone of quality pediatric healthcare by patients, parents, healthcare providers and systems leaders. However, little dedicated research on the nature, components and delivery of compassion in pediatric settings has been conducted. This study aimed to define and develop a patient, parent, and healthcare provider informed empirical model of compassion in pediatric oncology in order to begin to delineate the key qualities, skills and behaviors of compassion within pediatric healthcare.

Methods

Data was collected via semi‐structured interviews with pediatric oncology patients (n = 33), parents (n = 16) and healthcare providers (n = 17) from 4 Canadian academic medical centers and was analyzed in accordance with Straussian Grounded Theory.

Results

Four domains and 13 related themes were identified, generating the Pediatric Compassion Model, that depicts the dimensions of compassion and their relationship to one another. A collective definition of compassion was generated–a beneficent response that seeks to address the suffering and needs of a person and their family through relational understanding, shared humanity, and action.

Conclusions

A patient, parent, and healthcare provider informed empirical pediatric model of compassion was generated from this study providing insight into compassion from both those who experience it and those who express it. Future research on compassion in pediatric oncology and healthcare should focus on barriers and facilitators of compassion, measure development, and intervention research aimed at equipping healthcare providers and system leaders with tools and training aimed at improving it.

Keywords: beneficence, compassion, compassionate care, grounded theory, model, person‐centerd care, pediatric, qualitative

1. INTRODUCTION

Compassion has long been considered an essential feature of quality healthcare, particularly in the context of suffering, 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 which has been defined as “the state of severe distress associated with events that threaten the intactness of the person.” 5 While compassion is a reputed standard of care in pediatric settings, research on the topic in pediatric healthcare is scarce. 1 , 6 Etymologically, compassion means to “suffer with,” 7 and in the adult healthcare literature has been shown to improve psychosocial distress, symptom burden, quality of life, satisfaction with care, the therapeutic relationship and disclosure of health information. 1 , 4 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 Conversely, a lack of compassion is associated with increased adverse medical events, diminished patient resilience, increased healthcare costs, and increased patient complaints and malpractice suits. 4 , 12 , 13 HCP’s ability to provide compassion is impeded by increased patient caseloads and complexity, administrative duties, and healthcare systems that are predominately focused on efficiencies and economics. 1 , 3 , 14 , 15

In the pediatric literature, early evidence suggests HCP compassion plays a significant role in patients’ and parents’ perceptions of pediatric quality care, 16 effective clinical communication, 17 , 18 , 19 and collaborative shared decision making between parents/patients and HCPs. 20 The precise nature, domains, and requisite skills associated with pediatric compassion have not been studied, impeding research on the topic, including whether compassion can be measured and taught. This leaves students and pediatric HCP’s few tools and guidance to increase the compassion they provide to their patients and family members. 12 , 21 , 22 A recent systematic review, 6 reported that while training interventions and measures of compassion are emerging in the adult healthcare literature, 23 , 24 training interventions and measures of compassion within pediatric healthcare are hindered by the lack of an empirical model. As a result, the review authors recommended that “future research should focus on identifying the qualities, behaviors, and skills that pediatric patients and their parents observe in compassionate HCPs, as well as developing an evidence‐based foundation to guide the integration of compassion into pediatric practice, policy, education, and research.” 6 Thus, the primary objective of this study was to define and develop an empirical model of compassion based on the perspective of pediatric oncology patients, parents and their HCPs in order to begin to delineate the key HCP qualities, skills and behaviors of compassion. The secondary objective was to determine whether models of compassion vary between pediatric and adult cancer patients.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study population

Following approval from the research ethics boards (REB) at each study site (University of Calgary: HREBA.CC.18‐0174; SickKids‐REB: 1000062130; IWK‐REB: #1024312; UBC Children’s & Women’s REB: H18‐02845), participants were recruited through convenience, snowball and theoretical sampling whereby certain types of participants are intentionally recruited to develop a robust theory. 25 Participants were recruited from oncology programs at four Canadian pediatric hospitals between October 2018 and February 2020. Pediatric oncology patients were eligible for recruitment if they were: English speaking; 8 to <18 years of age; and living with a cancer diagnosis ≥3 months. Parents who provided care for a child who met eligibility criteria were eligible to participate and HCPs were eligible if they were caring for eligible patients and had been working in pediatric oncology for ≥1 year. Based on our previous research on the topic and desire to sample patients across developmental stages, 26 , 27 , 28 we aimed to recruit 60 participants (30 pediatric patients/15 parents/15 HCPs), but ultimately recruited 66 participants in order to achieve data saturation (Table S1).

2.2. Data collection

After assent and/or consent were obtained, one‐on‐one interviews, lasting approximately 45 min were conducted in person or via a secure online video interview platform (Skype) based on participant preference. A semi‐structured interview guide was developed (Table 1) based on a literature review 6 and previous qualitative research in adult populations, 26 , 27 and was adapted for pediatric use (i.e., vocabulary used was age appropriate—Flesch‐Kincaid). Three trained qualitative interviewers (SS, KWo, and KWe), with clinical experience in pediatric oncology conducted the interviews in order to ensure standardized implementation. Online video interviews occurred simultaneously across sites, while face‐to‐face interviews occurred at sequential site visits. Interviews were audio‐recorded, transcribed verbatim and independently verified against the original audio file by the transcriptionist and a research assistant.

TABLE 1.

Interview guiding questions

| Healthcare provider interview script |

|---|

| 1. What are the things that have become important for you, during your illness? [What things matter to you when receiving care?] |

| 2. In your own words, what does compassion mean to you? [Some people have told us that compassion means “a deep sense of the suffering of another person and a desire to help make it better,” what does compassion mean to you]? |

| 3. Has your view of compassion changed over time in any way? How so? [If we were to ask you about compassion a few years ago would you have the same or different views on it]? |

| 4. Can you give me an example of when you received compassionate care? [Can you describe a moment a healthcare provider gave you compassion?] |

| 5. How do you tell when a healthcare provider is being compassionate? [What tells you that one healthcare provider is compassionate in comparison to a healthcare provider who isn’t as compassionate] |

| 6. What would you say to your healthcare providers about how to be compassionate? [If you were asked to provide your healthcare provider tips on how to be compassionate, what would they be and why?] |

| 7. What impact do you feel compassionate care has on your overall care? [How does compassion effect the care you receive?] |

| 8. What ways do you think we might begin to improve compassionate care in our healthcare system? [What are your ideas about how we could make the healthcare system more compassionate]? |

| 9. Is there anything that we have not talked about related to compassion that we missed or you were hoping to talk about? [What else do you want to share with us about compassion]? |

| 10. What would you do to make sure the information you have provided about compassion actually changes the way healthcare providers do their job? [Any ideas of how we could remind healthcare providers about compassion; materials, practices, social media?] |

| 11. Is there anything related to compassion that we have not talked about today that you think is important or were hoping to talk about? |

| Parent/Guardian interview script |

|---|

| 1. What are the things that you have found to be important to you and your child’s well being during their illness? Particularly as it relates to the care you have received? |

| 2. In terms of your experience as a parent of a sick child, what does compassion mean to you? [Some people have told us that compassion means “a deep awareness of the suffering of another person and a desire to help make this better,” how do you understand it from the perspective of a parent]? |

| 3. Thinking back across the care your child has received and your child’s interaction with the healthcare system, as a parent has your understanding of compassion changed in any way? [How so? Why?] |

| 4. Can you give me an example of when you experienced care that was compassionate? [Can you describe a moment when your child received compassion from a healthcare provider]? |

| 5. How do you know when a healthcare provider is being compassionate? [What are the signs or ways that you know a healthcare provider is compassionate?] |

| 6. What advice would you give healthcare providers about how to be compassionate to children and families? [If you had to address an audience of healthcare providers on how to be compassionate what are the key things you would say?] |

| 7. What impact do you feel compassionate care has on your child’s healthcare? [How does it affect you and your child’s experience of care]? |

| 8. What suggestions or ways do you think we might begin to improve compassionate care in our healthcare system? [Thinking about the broader healthcare system, what are some ways that we could improve compassionate care?] |

| 9. Is there anything that we have not talked about that we missed or you were hoping to talk about? |

| 10. In knowing that this study will produce a model of compassion, what suggestions would you make to ensure that it informs the care you receive’? [What suggestions would you give to ensure that your views and the views of others actually lead to a change in practice]? |

| 11. Is there anything related to compassion that we have not talked about today that you think is important or were hoping to talk about? |

| Healthcare provider interview script |

|---|

| 1. Based on your professional and personal experience, what does compassion mean to you? [Some people have told us that compassion means “a deep awareness of the suffering of another person and a desire to help make this better,” how do you understand it] |

| 2. Can you give me an example of when you felt you provided or witnessed care that was compassionate? [What do you feel were the key aspects of these interactions?] |

| 3. What do you feel are the major influencers of compassionate care in your practice? [What informs or cultivates your ability to be compassionate]? |

| 4. What do you feel inhibits your ability to provide compassionate care? [What impedes or gets in the way of your compassion toward patients and family members]? |

| 5. Do you think patients and/or family members influence the provision of compassionate care? [How or how not?], [if yes, what characteristics of patients and/or families, do you feel facilitate or inhibit compassionate care?] |

| 6. What advice would you give other healthcare providers on providing compassionate care? [What are some tips that you would share with other healthcare providers on being compassionate] |

| 7. What would you want parents and patients to know about providing compassionate care? [What insights or tips would you give parents about providing compassionate care]? |

| 8. Based on your experience what role, if any, do you feel compassion has in alleviating distress among pediatric patients with an advanced cancer diagnosis and their families? [What happens when compassionate care is lacking?] |

| 9. What impact does providing compassionate care have on you personally and professionally? [What effect does providing compassion have on you as a healthcare provider? What is the effect of providing compassion on you personally?] |

| 10. In thinking about implementing this model into practice, policy and education, what suggestions would you provide to optimize uptake? [What would you suggest to make sure that this research changes clinical practice]? |

| 11. Is there anything related to compassion that we have not talked about today that you think is important or were hoping to talk about? |

2.3. Data analysis

Qualitative analysis was guided by Straussian Grounded Theory (SGT), an inductive, rigorous and iterative method that aims to define and develop an empirical model grounded in a naturalistic setting and direct participant accounts rather than a predetermined hypothesis or theory. 25 , 29 Four members of the research team (SS, SRB, KWo, and KWe) analyzed each transcript in accordance with the three stages of SGT. Open coding began with researchers coding each transcript independently in a line‐by‐line fashion using the constant comparison technique before coming together as a group to compare individual codes and come to consensus. 25 , 29 Axial coding involved assigning codes to initial themes and domains, and the development of a coding schema which was used and modified to code each subsequent transcript in an iterative fashion. The final stage of coding, selective coding, occurred after all transcripts were analyzed over a two‐day research team meeting. During these meetings the themes, domains, core variable, model and differences between groups were verified by having the research team review each code, theme and domain in the coding schema in an iterative and inductive manner. Additionally, rigor was ensured in this study by addressing the four criteria for rigor in grounded theory studies 29 , 30 : Fit (the degree to which the theory is represented by actual study data) was achieved by members of the research team independently coding each transcript; workability (the extent to which the domains in the theory explain the phenomena of interest and predict and interpret patterns), was ensured by validating the emerging theory with subsequent interview data using the constant comparative technique; relevance (the extent to which the theory reflects actual clinical concerns and the phenomena of interest) was achieved through member checking and triangulating data between the three study groups; modifiability (the extent to which concepts and substantive theory are able to readily accommodate new data), was assured by having the other members of the research team verify the audit trail to confirm relevance of new data to existing data.

3. RESULTS

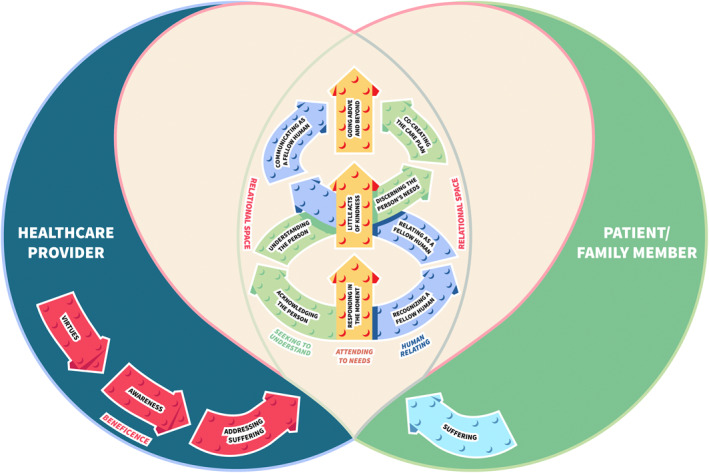

The core variable and collective definition of compassion generated by study participants was a beneficent response that seeks to address the suffering and needs of a person and their family through relational understanding, shared humanity, and action. Participants understood and experienced compassion as a dynamic, complex, and multi‐faceted construct, that was comprised of four key domains (beneficence, human relating, seeking to understand, and attending to needs), associated themes, with their relationship to one another depicted in the Pediatric Compassion Model (PCM; Figure 1, Table S2). Participant quotes were selected to reflect the collective views of participants, as well as nuanced differences between and within groups (Table S2).

FIGURE 1.

Pediatric compassion model

3.1. Domain: Beneficence

The first domain, beneficence, was defined as an active response, arising from a person’s virtues, that acknowledges and desires to address a person’s suffering, and contained three themes: virtues; awareness; and addressing suffering (Table S2). The first theme, virtues, was conceptualized as good qualities residing in a person’s character, functioning as the motivators of compassion. While HCPs were more likely to confine virtues to their professional qualities (e.g., prudence, truthfulness, etc.), parents and patients, especially younger patients, were more likely to characterize virtues as being embedded in HCPs personhood or coming from HCP’s hearts (e.g., love, kindness, genuineness, etc.). Despite the innate and inherent nature of virtues, each study group believed virtues could be nurtured through a practice of awareness, the second theme, which was defined as an intentional practice of bringing personal virtues and another person’s suffering into consciousness. The third theme, addressing suffering, an active response to be of benefit to a person in suffering, involved HCPs integrating and activating their latent virtues into their professional practice, in response to a person in suffering. While this was an intrapersonal process within HCPs, many patients and families felt that they could intuitively feel HCP’s virtues. In fact, participants surmised that the three themes of beneficence, distinguished compassionate HCPs from HCPs who were simply providing routine care or were wanting to be perceived as compassionate—with the former being described as genuinely caring and having a real interest in the patient and the latter simply doing their job or duty. The outcome of this initial response to suffering, was the creation of a relational space, where HCP virtues and patient and family suffering coalesced, allowing the other domains of compassion to unfold.

3.2. Domain: Human relating

Human relating, a genuine desire to engage a person in suffering as a fellow human being, the second domain within the model, extended the initial expression of compassion through HCP’s beneficence to a deeper relational connection of shared humanity. The themes within this domain involved recognizing, relating, and communicating with patients and families as fellow human beings (Table S2). While these themes occurred in the context of clinical care, participants believed that it was HCPs’ ability to step outside of their clinical roles, to relate from a place of shared humanity, that was a defining feature of compassion. Recognizing a fellow human being, involved connecting to aspects of shared humanity between oneself and a person in suffering, requiring vulnerability and sensitivity on both the part of HCPs and families and patients in suffering. Next, relating as a fellow human being involved a deeper interpersonal process of HCPs feeling with a person in suffering, whereby HCPs aimed to emotionally resonate with a person’s suffering. Communicating as a fellow human being involved HCPs sharing aspects of one’s humanity in medical and non‐medical conversations in order to forge a deeper human connection.

3.3. Domain: Seeking to understand

The third domain of compassion emerging from the data was seeking to understand, a proactive desire to understand the patient and their needs in order to provide compassion in a personalized manner. Whereas human relating was a universal response to a fellow human being, seeking to understand involved HCPs calibrating compassion in an individualized fashion—in order to understand the person and their unique needs. The first theme within this domain, acknowledging the person, involved acknowledging the person in each interaction (Table S2). The second theme, understanding the person, extended this to a desire to come to an in‐depth understanding of the person and their unique experience of suffering. In contrast to the domain of human relating, which involved emotionally resonating with the person in suffering, understanding the person involved a higher process, of listening to and recognizing the person’s unique experience of suffering. In gaining an in‐depth understanding of the person, HCPs believed they were better positioned to discern the person’s needs, the third theme within this domain, which involved assessing an individual’s unique and comprehensive care needs in an anticipatory manner. This personalized and pro‐active approach to care, facilitated the final theme within this domain, co‐creating the care plan, whereby HCPs, parents and the patient integrated patient’s personal needs and relevant clinical information into a personalized care plan.

3.4. Domain: Attending to needs

Attending to needs, the final domain, served as the central and defining feature of compassion, functioning as the central pillar of the entire model. Attending to needs was defined as timely, attuned and responsive acts intended to ameliorate a person’s suffering in momentary, routine, and extraordinary ways. The themes that comprised this domain included: responding in the moment, little acts of kindness, and going above and beyond (Table S2). Responding in the moment involved being present and responsive to a person and their immediate needs. Responding in the moment was understood as both a spontaneous and thoughtful act towards a patient’s and family’s immediate needs in a non‐conditional manner, particularly when “dealing with distressed families” or as patients and families described “when I am at my worst.” Little acts of kindness involved acts of compassion embedded in the way routine care is given and were often described as the tone and tenor of care by study participants. Family members and patients identified HCP’s ability to have fun and bring levity to their situation as one of the most poignant examples of embedding compassion into routine care. When study participants described exemplary acts of compassion, however, they largely involved stories of individuals providing compassion outside of routine care or going the extra mile. Going above and beyond involved extraordinary acts of compassion that go beyond the call of duty and were considered by parents and pediatric patients as a defining feature of a truly compassionate HCP. While extraordinary acts occurred sporadically, they had an enduring positive effect on patients’ and parents’ current and future interactions with their HCPs and the healthcare system as a whole.

4. DISCUSSION

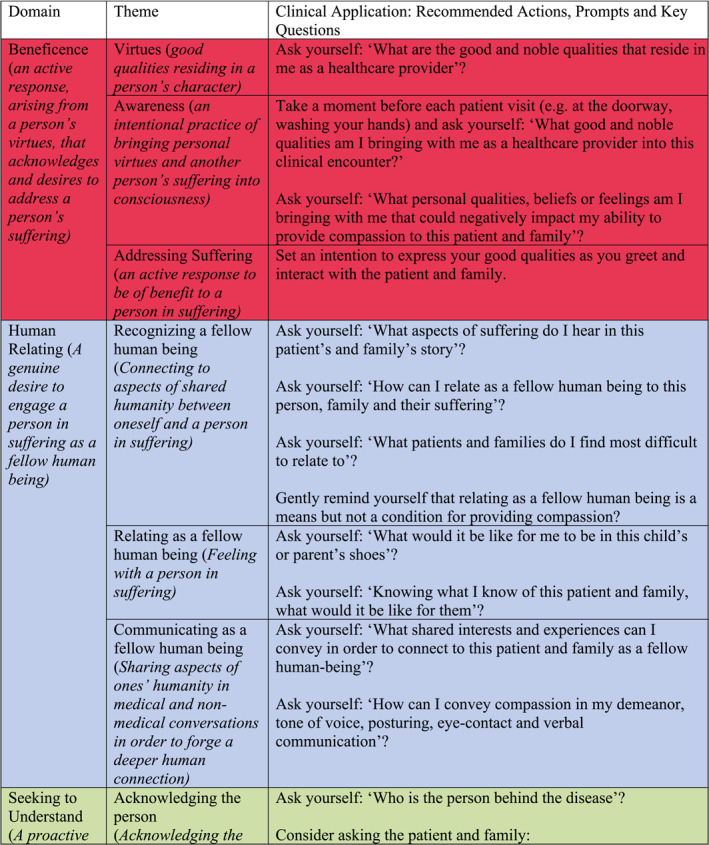

This study aimed to establish a clinically informed, empirical definition and pediatric model of compassion from the perspectives of pediatric oncology patients, families and HCPs. Compassion was conceptualized by oncology patients, parents and HCPs as a multi‐dimensional construct, contrasting uni‐dimensional depictions of compassion within the research literature restricting it to an emotion, trait or a virtue in and of itself. 1 , 31 These findings also provide pediatric oncology HCPs with a model that has clinical utility, identifying the core components of compassion and recommendations for application into practice (Table 2). While the domains of the PCM (Figure 1) and associated clinical questions (Table 2) can serve as a clinical guide, HCPs are reminded that while specific components of the PCM may be more prominent at certain junctures in the care continuum, compassion is comprised of beneficence, relational skills, and behaviors which should be delivered concurrently in response to patients’ and parents’ needs, mitigating a prescriptive or “one‐size fits all” approach.

TABLE 2.

Domains, themes, definitions and clinical applications

|

|

With respect to our secondary objective, results indicate that understandings of compassion were largely congruent between adult and pediatric oncology populations. 26 , 27 The results of this study did advance and refine these previous conceptualizations of compassion, while also highlighting some nuanced differences in the delivery of compassion in pediatric oncology populations. First, while this study identified virtues as the motivators of compassion, virtues in and of themselves, did not seem to lead to compassion as had been previously suggested. 26 , 27 Rather, study data suggests that latent virtues required expression in relation to compassion, resulting in the theme of virtues being subsumed under the action‐oriented domain of beneficence, where they were coupled with the themes of awareness and addressing suffering. Second, while relational communication is a cornerstone of conceptualizations of compassion in adult populations, in this study, it involved a deeper dialogical process, whereby HCPs did not simply communicate treatment plans with compassion, but proactively co‐created compassionate care plans in partnership with parents and their child, which is consistent with other pediatric studies and practice guidelines. 32 , 33 Third, while human relating traversed multiple domains in the adult compassion models, 26 , 27 among participants in this study, it emerged as a distinct domain highlighting the increased importance of human relating in pediatric oncology. While the precise reason for this difference is beyond the scope of this study, patient and parent participants frequently referenced HCPs ability to relate to the child like a ‘friend’ or through the medium of play, and not simply their ability to relate to parents as a fellow adult, as one of the greatest markers of compassion. In addition to affirming the importance of engaging the child directly on their level, 27 , 28 these findings suggest that relating compassionately, as a fellow human being, involves not simply relating to individuals we can readily identify with (e.g., age) but relating to those who differ from us. 28 In a similar vein, while patient and family dynamics challenged HCPs ability to provide compassion, participants were clear that compassion was not contingent on patient and parent receptivity or behavior. 1 , 28 In fact, pediatric oncology patients and family members identified exemplary compassionate care providers as individuals who were able to extend compassion in the most challenging circumstances—when the child or parents were on their worst behavior—suggesting that perhaps such “inappropriate” behaviors could be re‐conceptualized as “compassion seeking behavior”.

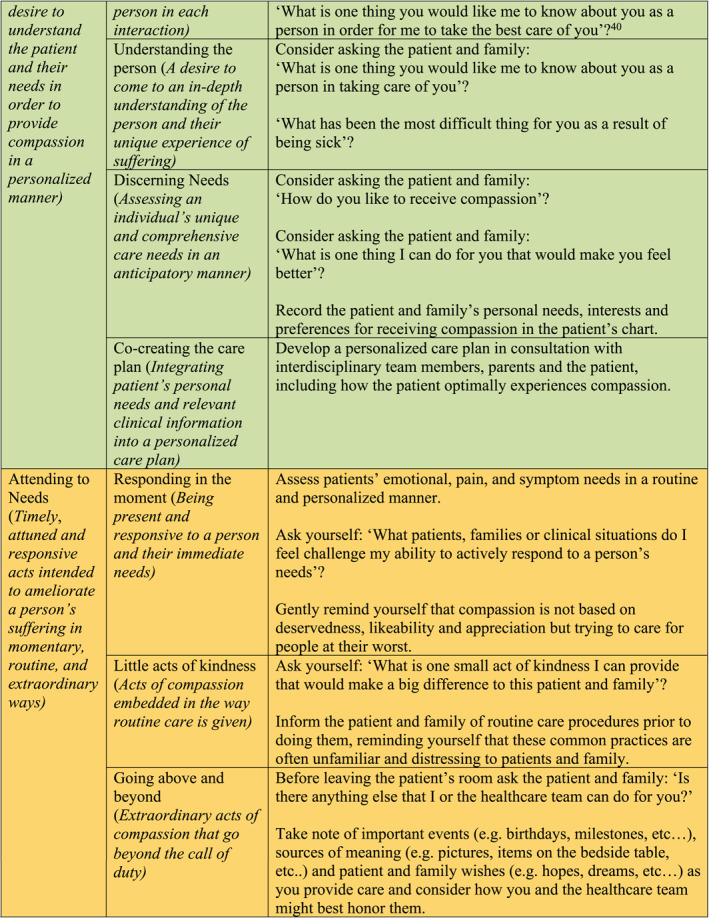

While there was congruence across study groups in relation to the nature of compassion and domains within the model, there were some minor differences in terms of which domains were emphasized. Specifically, children and parents were more inclined to emphasize the domain of beneficence, as being foundational to their experiences of compassion, while HCPs placed the least emphasis on these personal and professional qualities (Figure 2). HCPs’ emphasis on tangible actions and communication skills, embedded within the domains of attending to needs and seeking to understand, reflect a more top‐down (head‐to‐heart) understanding of compassion than pediatric oncology patients and parents more bottom‐up (heart‐to‐head) understanding, which is congruent with distinctions between cognitive (cognition‐to‐affect) and affective (affect‐to‐cognition) empathy. 34 Previously, this has not been identified as a factor in compassion specifically. 28 We cannot conclude these differences are indicative of rank importance or infer two pathways of compassion, as participants were unified in their belief that compassion was comprised of each of the key domains in the model. These group differences may be due to differences between externalized experiences of receiving compassion and the internal processes utilized in providing it (Figure 2). 1 , 26 , 27 , 28 These differences may partially explain the discord between patient and families’ experience of compassion and HCP’s desire to provide it, 1 , 35 , 36 as the former seem to emphasize the personal qualities of HCPs conveyed through the tone and tenor of care, while the latter emphasize clinical behaviors that may or may not be motivated by beneficence and may therefore not be experienced as compassion by patients and parents.

FIGURE 2.

Differences in domainal emphasis

Descriptions of compassion also differed slightly across developmental stages with younger patients emphasizing beneficence, while older patients were more likely to add other domains on top of this foundational domain (Figure 2). These results are congruent with developmental theorists who note that the executive brain functions required to understand abstract concepts, such as human relating and seeking to understand, develop later in childhood. 37 , 38 While these developmental differences may be due to language skills and cognitive ability, HCPs are encouraged, particularly when caring for younger patients, to ensure that these more complex domains of compassion translate and are enacted through simple expressions of love, kindness, gentleness, acceptance, joy, and genuineness. This step‐wise understanding of compassion by developmental stage was summated in the words of one patient:

Well as you get older, you know the base of it and you can keep kind of adding onto the piece. It can be like building blocks …it's not like “oh a 12‐year‐old immediately knows what it is”; it's, you know, “this is the base” and as you get older you might be able to add more building blocks on to make them help them understand as they get older and understanding the different concepts (Patient 32, 13 y.o.)

One of the main findings of this study was that compassion requires action. The implications of this finding are significant for researchers, clinicians and healthcare system leaders alike, distinguishing compassion from other care constructs such as empathy and sympathy which do not require action and can exacerbate HCP distress and burnout. 28 , 39 Medical and psychosocial interventions by their very nature are action‐oriented, however the results of this study suggest that compassionate action enhances and transcends routine care through the addition of micro behaviors stemming from HCPs good qualities; a willingness to know and be known as a fellow human being; and to proactively seek to understand not simply the patient, but the child behind the disease. Likewise, health system leaders, wanting to enhance compassion in clinical cultures and the pediatric system are encouraged to not simply embed compassion in their vision and mission statements, but to integrate patient reported compassion measures as a standard of care and to consider compassion an organizational performance indicator‐‐transforming vision into action. 23 , 24

4.1. Clinical implications

The PCM provides pediatric HCPs with a clinically informed model of compassion that can be incorporated into individual practice and interdisciplinary care teams in order to ensure that compassion is being optimally delivered across each domain. Recommended actions, prompts and key questions (Table 2) associated with each component of the PCM provides clinicians the pragmatic means to integrate compassion into their professional practice. The PCM also provides a foundation for the development of a patient and family reported compassion measure to routinely assess compassion and potentially the creation of compassionate care pathways, whereby compassion becomes an embedded component of care delivery that is documented, monitored and evaluated by healthcare institutions.

4.2. Study limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, as this was a qualitative study, the findings may not be generalizable to other settings. Second, while we aimed to recruit a culturally diverse sample of participants, our study sample was predominately White and may therefore have produced a model of compassion that was constructed by and inadvertently serves a White worldview. Third, a related but often overlooked limitation, is the homogeneous composition of our research team, which may have unduly influenced the interpretation of our results. Fourth, our study participants were primarily recruited from outpatient oncology units and therefore their perspectives may not be representative of inpatient or non‐cancer populations. Fifth, since participants volunteered to be a part of this study, they likely had a pre‐existing interest and affinity to the topic creating a possible sample bias. Finally, as the primary objective of this study was to define the nature of compassion in pediatric healthcare, it does not account for the operational, relational and practice issues that challenge healthcare providers' aspirations to provide compassion—a topic which will be the subject of a forthcoming manuscript generated from a secondary dataset within this larger study.

5. CONCLUSIONS

This study established an important foundation for compassion research in pediatric oncology—the PCM. The PCM provides initial construct validity to pediatric researchers who aim to develop compassion measures and interventions, while providing pediatric HCPs with a clinical model that depicts the domains and flow of compassion that can be considered for integration into both education and clinical practice. Finally, the PCM embodies the patient and parent perspective, which is imperative to ensuring that research, policy development, and clinical practice align with the ultimate indicator of compassion—the actual experiences of patients and parents within the pediatric healthcare system.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We want to extend our immense gratitude to the patients, parents and HCPs who took the time and effort to participate in this study—especially those patients who have since passed away. We also want to thank the clinical teams at each center who helped to promote the study and identify participants. We also want to thank our research assistants at our study sites: Mandy Bouchard (Halifax); Hannah Kim (Vancouver); and Carolyn Campbell (Toronto). Special thanks is expressed to members of the Compassion Research Lab (www.drshanesinclair.com): Priya Jaggi (Research Coordinator) for managing the project and coordinating this study across sites, and our qualitative interviewers, Kate Wong (Graduate Trainee) and Katie Webber (Graduate Trainee) for conducting the interviews and supporting data analysis. This study was conducted with support from C17 and funded by the Ewing’s Cancer Foundation of Canada and Childhood Cancer Canada Foundation and by the Faculty of Nursing, University of Calgary.

Sinclair S, Bouchal SR, Schulte F, et al. Compassion in pediatric oncology: a patient, parent and healthcare provider empirical model. Psychooncology. 2021;30(10):1728‐1738. doi: 10.1002/pon.5737

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sinclair S, Norris JM, McConnell SJ, et al. Compassion: a scoping review of the healthcare literature. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;19(15):6. 10.1186/s12904-016-0080-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. The Beryl Institute . Consumer Study on Patient Experience. Nashville: Studer Group; 2018. Available from: https://www.theberylinstitute.org/page/PXCONSUMERSTUDY [cited 2019 December 16]. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Francis R. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry. London, England: The Stationary Office; 2013. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/279124/0947.pdf [cited 2020 September 4]. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lown BA, Rosen J, Marttila J. An agenda for improving compassionate care: a survey shows about half of patients say such care is missing. Health Aff. 2011;30(9):1772‐1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cassell EJ. The Nature of Suffering and the Goals of Medicine. 33. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sinclair S, Kondejewski J, Schulte F, et al. Compassion in pediatric healthcare: a scoping review. J Pediatr Nurs. 2020;51:57‐66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hoad T, ed. Oxford Concise Dictionary of English Etymology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. Available from: https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780192830982.001.0001/acref‐9780192830982‐e‐3125?rskey=ZYw7Sc&result=3121 [cited 2021 May 12]. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barbarin OA, Chesler MA. Relationships with the medical staff and aspects of satisfaction with care expressed by parents of children with cancer. J Community Health. 1984;9(4):302‐313. 10.1007/bf01338730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lloyd M, Carson A. Making compassion count: equal recognition and authentic involvement in mental health care. Int J Consum Stud. 2011;35(6):616‐621. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schwartz A, Weiner SJ, Weaver F, et al. Uncharted territory: measuring costs of diagnostic errors outside the medical record. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(11):918‐924. 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fogarty LA, Curbow BA, Wingard JR, McDonnell K, Somerfield MR. Can 40 seconds of compassion reduce patient anxiety? J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(1):371‐379. 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.1.371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lundqvist A, Nilstun T, Dykes AK. Both empowered and powerless: mothers' experiences of professional care when their newborn dies. Birth. 2002;29(3):192‐199. 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2002.00187.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Levinson W, Roter DL, Mullooly JP, Dull VT, Frankel RM. Physician‐patient communication. The relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. J Am Med Assoc. 1997;277(7):553‐559. 10.1001/jama.277.7.553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fernando AT, Consedine NS. Beyond compassion fatigue: the transactional model of physician compassion. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2014;48(2):289‐298. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Branch C, Klinkenberg D. Compassion fatigue among pediatric healthcare providers. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2015;40(3):160‐164. 10.1097/NMC.0000000000000133quiz E13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rider EA, Perrin JM. Performance profiles: the influence of patient satisfaction data on physicians’ practice. Pediatrics. 2002;109(5):752‐757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Contro NA, Larson J, Scofield S, Sourkes B, Cohen HJ. Hospital staff and family perspectives regarding quality of pediatric palliative care. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):1248‐1252. 10.1542/peds.2003-0857-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Espinel AG, Shah RK, Beach MC, Boss EF. What parents say about their child’s surgeon parent‐reported experiences with pediatric surgical physicians. JAMA Otolaryngology. Head Neck Surg. 2014;140(5):397‐402. 10.1001/jamaoto.2014.102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jones BL, Contro N, Koch KD. The duty of the physician to care for the family in pediatric palliative care: context, communication, and caring. Pediatrics. 2014;133(Suppl 1):S8‐S15. 10.1542/peds.2013-3608C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Orioles A, Miller VA, Kersun LS, Ingram M, Morrison WE. To be a phenomenal doctor you have to be the whole package": physicians' interpersonal behaviors during difficult conversations in pediatrics. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(8):929‐933. 10.1089/jpm.2013.0103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brooten D, Youngblut JM, Seagrave L, et al. Parent's perceptions of health care providers actions around child ICU death: what helped, what did not. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2013;30(1):40‐49. 10.1177/1049909112444301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dyer C. Leeds paediatric cardiac care was safe but not compassionate, report says. BMJ 2014; 348:g2147. 10.1136/bmj.g2147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sinclair S, Russell L, Hack T, Kondejewski J, Sawatzky R. Measuring compassion in healthcare: a comprehensive and critical review. Patient: Patient Centred Outcomes Research. 2017;10(4):389‐405. 10.1007/s40271-016-0209-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sinclair S, Hack TF, MacInnis CC, et al. Development and Validation of a Patient Reported Measure of Compassion in Healthcare: The Sinclair Compassion Questionnaire (SCQ). BMJ Open. [Under Review] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Corbin JM, Strauss AL. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 4th edn. Los Angeles: SAGE; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sinclair S, McClement S, Raffin‐Bouchal S, et al. Compassion in healthcare: an empirical model. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2016;51(2):193‐203. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sinclair S, Hack TF, Raffin‐Bouchal S, et al. What are healthcare providers' understandings and experiences of compassion? The healthcare compassion model: a grounded theory study of healthcare providers in Canada. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3):e019701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sinclair S, Beamer K, Hack TF, et al. Sympathy, empathy, and compassion: a grounded theory study of palliative care patients' understandings, experiences, and preferences. Palliat Med. 2017;31(5):437‐447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory; Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago: Aldine Pub. Co; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Glaser BG. Advances in the Methodology of Grounded Theory: Theoretical Sensitivity. The Sociology Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schantz ML. Compassion: a concept analysis. Nurs Forum. 2007;42(2):48‐55. 10.1111/j.1744-6198.2007.00067.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Giambra BK, Broome ME, Sabourin T, Buelow J, Stiffler D. Integration of parent and nurse perspectives of communication to plan care for technology dependent children: the theory of shared communication. J Pediatr Nurs. 2017:29‐35a. 10.1016/j.pedn.2017.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Institute for Patient‐ and Family‐ Centered Care . Better Together: Partnering with Families. Bethseda: Institute for Family‐Centred Care; 2010. [cited 9 December 2020]. Available from: https://www.ipfcc.org/bestpractices/better‐together‐partnering.html [Google Scholar]

- 34. Israelashvili J, Karniol R. Testing alternative models of dispositional empathy: the affect‐to‐cognition (ACM) versus the cognition‐to‐affect (CAM) model. Pers Indiv Differ. 2018;121:161‐169. 10.1016/j.paid.2017.09.036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Easter DW, Beach W. Competent patient care is dependent upon attending to empathic opportunities presented during interview sessions. Curr Surg. 2004;61(3):313‐318. 10.1016/j.cursur.2003.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bernardo MO, Cecílio‐Fernandes D, Costa P, Quince TA, Costa MJ, Carvalho‐Filho MA. Physicians' self‐assessed empathy levels do not correlate with patients' assessments. PLoS One. 2018;13(5):e0198488. 10.1371/journal.pone.0198488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hertherington EM, Parke RD, Schmuckler M. Child Psychology: A Contemporary Viewpoint. New York: MCGraw Hill; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shweder RA, Goodnow JJ, Hatano GR, LeVine RA, Markus HR, Miller PJ. The cultural psychology of development: one mind, many mentalities. In Damon W, Lerner RM (ed.). Theoretical models of human development. Volume 1 of the Handbook of child psychology (6th edn., pp, 716‐792). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sinclair S, Raffin‐Bouchal S, Venturato L, Mijovic‐Kondejewski J, Smith‐MacDonald L. Compassion fatigue: a meta‐narrative review of the healthcare literature. Int J Nurs Stud 2017; 69: 9‐24. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chochinov HM, McClement S, Hack T, Thompson G, Dufault B, Harlos M. Eliciting personhood within clinical practice: effects on patients, families, and health care providers. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2015;49:974‐980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.