Abstract

Collaborative governance is popular among practitioners and scholars, but getting a grip on the performance of collaborations remains a challenge. Recent research has made progress by identifying appropriate performance measures, yet managing performance also requires appropriate performance routines. This article brings together insights from collaborative governance and performance management to conceptualize collaborative performance regimes; the collection of routines used by actors working together on a societal issue to explicate their goals, exchange performance information, examine progress, and explore performance improvement actions. The concept of regimes is made concrete by focusing on the specific routine of organizing a collaborative performance summit; a periodic gathering where partners review their joint performance. Such summits are both manifestations of the performance regime and potential turning points for regime change. Using three local public health collaborations as illustration, this article offers a framework for understanding collaborative performance regimes, summits, and the dynamics between them.

Evidence for Practice —

The effective performance management of collaborations requires not only joint indicators, but also processes to jointly collect and review performance information with all partners.

Partners can choose to fully integrate their performance management processes, keep their processes separate, or find some middle ground between autonomy and integration.

Bringing together partners for collaborative performance summits can be valuable for gaining insights, but these meetings can also be counterproductive when poorly run.

The dominant performance processes within a collaboration will change over time, with summits forming potential turning points in a collaborative performance regime.

Advancing Collaborative Performance Management

Collaborative governance is popular among both practitioners and scholars, but getting a grip on the performance of collaborations remains a challenge (Emerson and Nabatchi 2015; Gash 2017). Research efforts have sought to identify appropriate performance measures for collaborations, detailing the exact dimensions or indicators to be assessed (Emerson and Nabatchi 2015; Page et al. 2015; Provan and Milward, 2001).

However, recent performance management research has found that effective performance management requires appropriate performance routines as well (Behn 2010; Gerrish 2016; James et al. 2020; Kroll and Moynihan 2018). Performance routines such as goal‐setting processes, performance budget negotiations, and performance reviews “structure how [actors] experience their work” (March and Simon 1993), help actors to make sense of ambiguity (Noordegraaf 2017), and motivate them to improve performance (Moynihan and Kroll 2016).

Performance management routines can be studied by looking at the collection of routines as a whole and by examining a specific routine in detail.

The collection of performance routines governing an organization have been called a “performance regime” (Jakobsen et al. 2017; Moynihan et al. 2011; Talbot 2010), encapsulating the overall structure and approach to performance management within an agency. In hierarchical settings, this regime would usually be dominated by a principal holding the agency to account by setting goals and conducting regular reviews (Jakobsen et al. 2017). In collaborative settings, there may not be a clear hierarchical relationship or even a specific goal (Ansell and Gash 2008; Behn 2010). As actors oscillate between the need to work together and desire to retain autonomy, collaborative performance regimes may be in a constant state of flux.

Specific performance routines for collaborations are similarly difficult to grasp. For example, Moynihan (2005) describes how single organizations can use performance reviews or “learning forums” to bring together representatives of different parts of an agency to make sense of performance information. Collaborations have also been observed conducting stakeholder conferences (Innes 1992), goal review workshops (Bryson et al. 2016), or forums (Bryson et al. 2020).

Meeting regularly in an established forum is considered crucial for improving collaborative performance (Choi and Robertson 2013; Gerlak and Heikkila 2011), yet designing productive and recurring routines is challenging (Bryson et al. 2020; Behn 2010). Many network sessions degenerate into talking shops with no discernible outcomes or “inauthentic discussions” where particularistic interests prevail over the need for collective action (Innes and Booher 2010).

The elusive and hazardous nature of collaborative performance regimes and routines poses a challenge for both practitioners and scholars. For practitioners, the challenges of navigating between actor‐ and network‐centric forces, formulating shared goals, and implementing structural reviews make establishing effective performance regimes and routines difficult.

For scholars, the complex and transitory nature of collaborative performance regimes and routines make them difficult to study. As a result, scholars may adopt an overly narrow focus on performance indicators and give scant attention to the performance routines necessary to animate these measures.

This article addresses these challenges by offering a clear conceptualization of three types of collaborative performance regimes between which collaborations may oscillate. These regimes are shaped by the societal and institutional context of the collaboration, but also evolve as the collaboration changes in nature.

The article then goes on to argue that a focus on a specific performance routine can help to better understand the wider regime dynamics. The focus here is on collaborative performance summits, where actors gather to jointly review their performance. These summits serve as a Petri dish for the wider collaborative performance regime dynamics.

Finally, the article discusses how performance routines such as summits are not only shaped by the performance regime, but can shape the regime in turn. Collaborative performance summits are manifestations of the regime structure, but also practices that can potentially affect the structure (Bryson et al. 2020). Similarly, impactful collaborative performance regimes may have some effect on the shape of the institutional context.

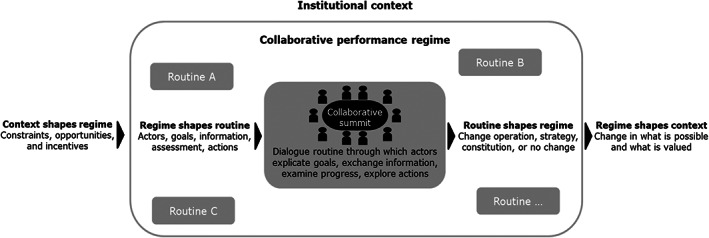

Figure 1 visualizes the concepts and their relationships as they will be discussed. The article will draw on the performance regimes and summits of three local public health collaborations to illustrate the theoretical argument and explore its practical implications. The article concludes by identifying questions for future research.

Figure 1.

Collaborative Performance: Context, Regimes, and Summits

Collaborative Performance Regimes: Differences and Challenges

Moynihan et al. (2011) observe that organizations facing different institutional contexts are likely to develop different types of performance regimes. Collaborations can equally be expected to develop a variety of regimes in response to the variety of contexts they face. For example, the extensiveness of a performance regime will be determined by the resources the partners can dedicate to the collaboration (Bowman and Parsons 2013, 63; Chenoweth and Clarke 2010), just as the regime will be shaped by the presence or absence of pressures to provide external accountability (Jakobsen et al. 2017).

The typology of different collaborative performance regimes proposed here is chiefly informed by the extent to which actors are driven toward partnership integration, varying from cooperation to coordination to collaboration (McNamara 2012). This perspective leads to three ideal types of collaborative performance regimes: An actor‐centric performance regime where actors maintain their separate performance routines; a network‐centric regime where actors fully integrate their performance routines; and a hybrid performance regime that stands between these extremes (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Three Types of Collaborative Performance Regimes

Actor‐Centric Performance Regime Actor‐Centric Performance Regime |

Hybrid Performance Regime Hybrid Performance Regime |

Network‐Centric Performance Regime Network‐Centric Performance Regime |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Actors in performance regime | Actors working on the same issue occasionally cooperate with others when necessary to achieve their own ambitions | Actors working on the same societal issue selectively coordinate their routines to achieve overlapping ambitions | Actors working on the same societal issue develop collaborative routines to achieve shared ambitions |

| Performance goals | Actors maintain separate goals but pursue their aims in conjunction with other actors to address societal challenges | Mix of separate goals at actor‐level and a limited number of shared goals supported by multiple actors | Shared, cross‐cutting goals at network level, supported by all participating actors |

| Performance information | Each actor collects its own performance information, which may be shared upon request with other actors | Regular, separate performance collection at actor‐level, with targeted information‐sharing for specific shared activities | Regular, joint performance information collected by partners on a network basis |

| Performance assessment | Each actor conducts its own performance review with assessments selectively shared with other actors | Regular, separate performance reviews at actor‐level alongside targeted joint reviews on specific shared activities | Regular, joint performance reviews at network‐level by all partners |

| Performance actions | Lessons from separate reviews translated into distinctive actions for each actor and communicated to other partners when relevant | Lessons from separate and joint reviews translated to action by each actor separately, with some coordination among actors | Lessons from joint review collectively translated to changes, implemented across all partners |

In the actor‐centric regime, each actor has its own separate performance management routines, sets its own goals, gathers its own information, and decides upon its own performance improvement actions. These actors still engage in cooperation by exchanging information with other actors about the goals they have set for themselves, the activities they run, and the performance information they have collected (McNamara 2012).

In the network‐centric performance regime, “cross‐boundary collaboration represents the prevailing pattern of behavior and activity” (Emerson, Nabatchi, and Balogh 2012, 6), including the performance management routines. The shared goals of the collaborative emerge through a cross‐boundary process of joint discovery in which all actors participate. These goals are reviewed periodically by all partners and the collaborative decides collectively how to adjust its actions to attain better results (Ansell and Gash 2008).

Hybrid collaborative performance regimes occupy a middle ground between actor‐centric and network‐centric regimes. While retaining their own set of separate goals, participating actors will identify a limited set of shared goals and will seek to coordinate their performance routines to achieve them. Actors may maintain their own performance evaluation processes, but also commit to conducting recurring reviews on a particular element of their activities.

The three types of collaborative performance regime presented here are conceptual ideal types; labeling actual performance regimes requires a more nuanced application of this idea (Gerrish 2016). As a performance regime is made up of different performance routines, many collaborations will probably have a mix of actor‐centric, network‐centric, and hybrid performance routines and the exact mix of performance routines is also likely to change over time (Bowman and Parsons 2013; Kristiansen, Dahler‐Larsen, and Ghin 2017). Labeling a performance regime of a particular collaboration, therefore, requires knowledge of the various routines within the regime and their development over time.

Illustrating Regime Differences in Practice

The differences between collaborative performance regimes are here illustrated by describing three partnerships in the public health domain in a medium‐sized Western European city. Although these initiatives took place within the same city and policy domain, their performance regimes varied between network‐centric, hybrid, and actor‐centric regimes.

The cases were concerned with reducing the link between Sports and Alcohol at amateur sport clubs, reducing Childhood Obesity across the city, and regulating a legal Street Prostitution zone. In all three cases, the local municipal government was the key policy maker and financier, but had to work with a range of public, private, and community partners to achieve its ambitions.

These cases are meant to illustrate the wider theoretical argument about the different types of collaborative performance regimes, rather than to provide evidence for hypotheses. The cases were researched by reviewing the policy documents of the local government, interviews with the responsible lead civil servants for each of the initiatives, the alderman responsible for public health, five elected council members, and observations during a meeting of each of the three collectives.

Sports and Alcohol

The Sport and Alcohol collaboration stemmed from the ambition of the local government to reduce the alcohol consumption at the city's amateur sport clubs, specifically focusing on the elimination of underage drinking and the discouragement of alcohol use by adults after matches. The actors within this performance regime included the local government, a private health insurer, 25 community sport clubs, the local police, and the alcohol addiction support agency.

The goals of the collaboration were laid down in a covenant signed by all partners, listing several broad ambitions (e.g. reduce under‐18s drinking, banish drunk driving, etc.), which were not otherwise specified. The partners agreed to share regular information about the implementation of joint publicity campaigns, regulations, etc., and committed to assessing the progress made at the end of the 4‐year covenant period to see what further actions should be taken.

On the whole, this performance regime mainly consisted of network‐centric routines. However, as the sport clubs were given relative freedom in trying out different policies at their own clubs, some of the operational activities were more actor‐centric than fully integrated.

Childhood Obesity

The Childhood Obesity collaboration focused on reducing the number of overweight children, affecting 24 percent of the local youths. The actors included a wide range of partners from the local government, a private health care insurer (providing funding for specific projects), local schools, sport clubs, family doctors, and the public health authority.

The local government council had set a specific goal for the collaboration, committing the alderman to decrease the rate to 22 percent in a year. The public health authority would collect information on the rate of obesity in the city through medical population data, while family doctors and schools pushed to also include indicators about well‐being when tracking the outcomes.

There were a range of different time‐bound, targeted projects to achieve the ambitions in which different combinations of partners collaborated (e.g. encouraging healthy school lunches, educating specific migrant communities), but no collective, comprehensive assessments to consider what actions should be taken to improve the initiative as a whole.

On the whole, this hybrid performance regime consisted of a mix of network‐centric goals and actor‐centric activities, with periodic and targeted collaborations.

Street Prostitution

The Street Prostitution case focused on regulating a zone in the city where curb‐side prostitution was legalized. Several actors were involved in the zone, including the local police team securing the area, social workers providing counseling for the sex workers, doctors offering medical advice, and the local government granting licenses to the sex workers.

The immediate goals of the different partners were around ensuring the safety and security of sex workers, clients, and neighborhood inhabitants, although there were no overarching ambitions spelling this out. The long‐term future of the zone was a contentious policy point—proponents argued the zone provided a safe place to work for vulnerable sex workers while opponents argued the zone should make way for high‐quality housing.

The professionals on the ground would swap information about particular concerns and assessed what could be done to keep the zone safe on a nightly basis, but were ultimately steered by the chiefs of their separate organizations. The political deadlock about the future of the zone meant that there were no joint reviews of the collective performance and no plans for actions in the long term.

On the whole, the performance regime was mainly actor‐centric, with separate goals for the various organizations, only some joined activities, and mere episodic coordination (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Three Collaborative Performance Regimes

| Street Prostitution | Childhood Obesity | Sports and Alcohol | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Actors in performance regime | Police, social workers, doctors, local government | Schools, public health authority, private health insurer, sport clubs, local government | Private health insurer, sport clubs, addiction center, local government |

| Performance goals | No overarching plan for zone; some generic ambitions to keep zone safe and secure | Overarching reduction target set by local council; specific goals for specific projects | Shared ambitions explicated in covenant, though without quantifying goals |

| Performance information | Regular on‐the‐ground information‐sharing, but no structured exchanges about overall performance | Information exchange within projects; yearly city‐wide survey of the obesity rate | Ongoing information‐sharing between the various initiatives |

| Performance assessment | No joint assessment among on‐the‐ground partners; frequent debate about zone among politicians | Joint assessment of specific projects, no collective reviews of overall initiative | Ongoing assessments of initiatives; commitment to joint review at end of covenant period |

| Performance actions | Regular on‐the‐ground learning and follow‐up, but no overall joint policy formulation | Occasional adjustments after review of projects, no overall joint review of actions | Commitment to improve and adapt initiative after four years |

Collaborative Performance Summits: Concrete and Crucial Routines

Even when describing the different components of a collaborative performance regime, as done for the three public health collaborations, the precise dynamics of their performance management can remain hard to grasp. Gerrish (2016) already observed that identifying the performance regime of an organization is already a tricky task, which makes it an even more difficult task to grasp the performance regime of multiple organizations working together.

A focus on a specific, tangible routine within the wider regime could provide more concrete insights. This article proposes that collaborative performance summits can be such a valid and valuable object of study through which to better understand the wider performance regime. Collaborative performance summits are here defined as gatherings where actors working on the same societal issue through dialogue explicate their performance goals, exchange performance information, examine their performance progress, and explore potential performance improvement actions.

Moynihan (2005, 33) observes that within single organizations, actors can gather for performance reviews through “dialogue routines specifically focused on solution seeking, where actors collectively examine information, consider its significance, and decide how it will affect future actions.”

Similar stakeholder conferences (Innes 1992), forums (Bryson 1993), performance dialogues (Rajala, Haapala, and Laihonen 2017), or CollaborationStat reviews (Behn 2010) have been described to occur between collaborating organizations. Such summits have been organized on a global (e.g. International AIDS Conferences), national (e.g. the US Presidential Anti‐Drugs Summits or the UK National Summit on a healthy active living), and local scale (e.g. the Detroit Regeneration Summit or the Northern England “Powerhouse” economic development summits).

Collaborative summits are both valuable as research objects and crucial as practical interventions. For practitioners, collaborative performance summits are important tools to grapple with the complexity of collaborative work and improve the performance of the collaboration. Moynihan and Kroll (2016, 314) find that “better run data‐driven reviews are associated with higher performance information use than poorly run reviews.” Behn (2014) finds that well‐prepared and well‐run summits lead to more efficiency and more societal impact. When done right, collaborative summits can be flywheels for further collective action, but may also turn into talking shops that feed apathy or fighting arenas where tensions explode (Innes and Booher 2010).

For scholars, summits serve as a Petri dish for the study of the wider collaborative performance regime. Summits provide an opportunity to observe the regime dynamics between actors, goals, information, assessment, and action in a concentrated, concretely observable form. The events of the summits are shaped by the wider regime, reflecting the prevailing approach toward actors, goals, information, and actions within the collaborative (Innes 1992).

Moreover, collaborative summits may also affect the shape of the wider regime. Summits are both practices shaped by the wider regime structure, and practical interventions that can slowly change the regime structure (see Gidden's structuration theory, as discussed by Bryson et al. 2020).

However, Laihonen and Mäntylä (2017) observe that the dynamics of such joint performance reviews remain poorly understood. The study of collaborative summits, and by extension collaborative regimes, could benefit from a more structured overview of the challenges and dynamics of these gatherings.

Integrating research on collaborative governance (Ansell and Gash 2008; Emerson and Nabatchi 2015; Gerlak and Heikkila 2011), forums (Bryson 1993; Behn 2014; Innes and Booher 2010), and performance management (Bryson et al. 2016; Moynihan et al. 2011) is here used to provide some insights into the challenges that shape the dynamics of summits.

The Actor Challenge

The challenge of selecting and activating the appropriate actors for the collaborative performance regime, while ensuring helpful dynamics between these partners, becomes very concrete when organizing a collaborative performance summit: Which players should participate and what will be their role?

The selection of actors to participate involves a trade‐off between comprehensiveness (all potentially relevant actors are at the table) and cohesiveness (partners with related ideas about performance are at the table) (Ansell et al. 2020; Graddy and Chen 2009). It may be easier to forge network‐centric performance routines with a relatively small group of like‐minded partners than with a large set of very different parties. Yet a small and homogenous group is unlikely to produce fresh collaborative insights (Innes and Booher 2010).

The dynamics between the actors have to face a tension between creating a collaborative spirit between the partners and acknowledging the power‐imbalances and pre‐histories that exist between stakeholders (Choi and Robertson 2013; Quick and Sandfort 2014). A key question is whether the leading principals and formal monitors participate in the summit to raise the stakes and ensure accountability, or whether they are excluded in order to foster a safer learning environment (Jakobsen et al. 2017).

The process design of a summit is an essential lever for shifting unhelpful role dynamics (Quick and Sandfort 2014), placing a great responsibility on the lead actor convening and facilitating the summit (Ansell and Gash 2012). Small changes, such as gathering the partners around a single round table rather than positioning the executive agents opposite a line of principals (as is done in US Senate hearing holding an executive to account) can significantly reframe the relationship.

The Goals Challenge

Organizing a summit brings into sharp focus how difficult it can be to formulate shared goals in a collaboration. As Moynihan et al. (2011, 152) observe, “[i]n complex governance settings, the greater heterogeneity of influential actors is likely to result in more marked battles about the definition of performance.” What goals or measures should the partners review during the summit discussions?

Navigating this challenge requires steering between over‐simplifying and over‐complicating the goals of a collaboration. The simplicity of crisp targets and quantifiable indicators does not do justice to multiplicity of ambitions the different actors bring to the table (Bryson et al. 2016). Bryson, Ackermann, and Eden (2016), therefore, argue that summits can be used to explore and map the complexity of shared and separate goals within a collaboration.

The art is to avoid interminable debates about the complexity while constantly updating the information tracked as the collaboration evolves. The essence of performance management is to explicate “which types of performance you measure—and which you do not” (Andersen et al. 2016, 852). Summits can be used to engage with these choices and lay out a first draft of the shared ambitions that move beyond a facile “let's agree to disagree.”

Subsequent summits can be used to monitor how the goals must change as the collaboration evolves. Poocharoen and Wong (Poocharoen and Wong 2016, 607), for example, find that actor‐centric network move from “hard‐and‐simple quantifiable measures that are used as a basis for budget allocations and to ensure the accountability of the collaborative partners” toward “looser, more implicit, and [less] quantifiable performance measures” if they evolve into more network‐centric collaborations.

The Information Challenge

With the actors gathered in a room for a summit, there is a great opportunity for exchanging information about the performance of the collaboration. However, various participants often do not recognize each other's data as valuable. What counts as evidence for these different participants and how can these different standards be connected?

The key to this challenge is to consider information exchange not merely as a technical data swap, but as a social process that bridges the different epistemologies of the various actors (Van Buuren 2009). Jos and Watson (2019), for example, show that street‐level civil servants accept different sources of information than their managers. Technocrats may also be keen to look at goals through the prism of targets and numbers, while community groups and citizens may be eager to discuss their day‐to‐day experiences (Innes and Booher 2010). Moynihan, Baekgaard, and Jakobsen (2019) find that if hospital managers use performance data to solve organizational problems rather than hitting performance targets, professionals will be more likely to engage in data‐informed, goal‐based learning.

Insights from performance management highlight that performance information should not be reduced to numbers and targets. A mix of statistical data, stakeholder experiences, and expert opinions provides a more comprehensive and engaging picture of the state of the collaboration and its impact (Battaglio and Hall 2018; Moynihan 2005). Connecting these various information types to “transboundary objects” to which all parties can relate can then help to ensure the summit participants engage with each other information (e.g. in the Childhood Obesity summit, the information from the schools, doctors, health authority, and shops was clustered around the daily eating and exercise habits of a typical child in the city) (Noordegraaf et al. 2017).

The Assessment Challenge

Assessing performance or impact is difficult with all public sector work. This challenge is compounded for collaboratives, as they are often explicitly initiated to address long‐standing societal problems, and the various actors may disagree in their assessment of the desirability of the solutions (Head and Alford 2015). A summit brings this challenge to the fore; how can actors weigh and discuss to what extent progress has been made?

At a summit, the first test is to connect the information previously exchanged to the assessment being made. Jennings and Hall (2012) found that actors distinguish between the objective production of information and subjective use of this information in policy decisions. Kroll and Moynihan (2018) observe how little performance information is actually used in management deliberations and how hard it is to connect it to systematic evaluations. Active process design and smart use of data props (i.e. making sure the data is in everyone's face) are necessary to keep the decisions in line (Behn 2014).

Even then, it may be hard to define what progress is being made. Provan and Kenis (2010) pragmatically argue for reviewing collaborative performance on many levels; assessing the community impact level where possible, but focusing on the precursors to performance where necessary (e.g. network membership, integration of services). Yet an overdose of progress purely in process terms may leave the actors financing the collaboration underwhelmed (Emerson and Nabatchi 2015).

Termeer and Dewulf (2019) offer a pragmatic perspective on assessing outcomes by encouraging partners and evaluators to consider “small wins” rather than comprehensive progress when evaluating collaborations. A summit should be used to identify small steps in the right direction, analyze the mechanisms that made this progress possible, and then feed these findings back into the policy process.

The Action Challenge

Collaborative summits can easily turn into talking shops, where everything is discussed but nothing gets done. However, collaborative summits can also generate too much momentum, making decisions that are not necessarily backed by the appropriate democratic scrutiny and mandate (Sørensen and Torfing 2016). How can summits generate the appropriate follow‐up actions?

The very complex and political nature of collaborative work in general and summits in particular makes it likely to nothing comes from a summit (Innes 1992). Whatever energy was built up in the room will dissipate as the gathered actors return to their own organizations and the daily grind. The danger here lies in that in the absence of clear follow‐up actions from a collaborative perspective, the disparate performance pressures on each separate organization will continue to shape their actions (Bryson 2016).

Another danger is that summits inspire too much action. Actor gatherings can become backroom dealings where a small group of unelected powerbrokers determine public policy. Without appropriate meta‐governance to ensure democratic scrutiny and proper representation, summits may overstep their mandate (Sørensen and Torfing 2016).

However, the inherent ambiguity in collaborative relationships makes it unclear who has a democratic mandate to make decisions anyway (Klijn and Skelcher 2007). If a summit resolves to make a significant change, actors will have to actively seek out the various political actors that will have to provide the appropriate democratic scrutiny for this next step.

Illustrating the Challenges of Summits in Practice

The mechanisms of these challenges can be illustrated by returning to the three public health collaborations. The city alderman responsible for public health hosted three summits—one for Sports and Alcohol, one for Childhood Obesity, and one for Street Prostitution—aiming to review the progress together with all the actors involved.

Each summit had 10–20 participants, including civil servants, elected members of the local legislative council, representatives of the subsidized charities and community groups involved in delivering the programs, and public health experts gathering data about the initiatives. Each summit took 2–3 h, starting with an explication of the performance goals, then exchanging performance information, examining progress, and finally exploring follow‐up actions.

To get access to these sensitive discussions and ensure comparability, the researchers got closely involved in designing and organizing the meetings together with the civil servants. A researcher was the summit facilitator for the Sports and Alcohol and Street Prostitution summits, and coached the civil servant facilitating the Childhood Obesity summits.

For each summit, we interviewed the alderman and the coordinating civil servant, plus two council members and two community partners. The researchers took extensive notes during the discussion to track the dynamics and followed‐up with the civil servant to track what happened after the summit.

This action research design (Stringer 2013) enabled unprecedented access to such summits discussions, both front‐ and backstage, and allowed us to make sure the summits were as comparable as possible. However, the close involvement of the researchers also meant they lose part of their distance and objectivity in surveying the summits. These observations are again only intended as illustrations of the theoretical argument (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Three Collaborative Performance Summits

| Street Prostitution | Childhood Obesity | Sports and Alcohol | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Actors in performance routine | Diversity of actors present, but not all relevant actors are willing to join the summit | Comprehensive range of actors present, ranging from teachers to policy makers, health experts to citizen volunteers | Small, but diverse set of actors present, representing different roles and perspectives related to the initiatives |

| Explicating performance goals | Summit starts with lengthy search for what community wants to achieve, revealing mainly harm avoidance goals | Government had pre‐set focus on BMI reduction, but summit establishes broader goals around well‐being | Goals were vaguely specified in covenant and actors mainly discuss potential trade‐offs between them |

| Exchanging performance information | Street‐level professionals share anecdotal insight into daily reality of zone | Highly diverse information ranging from anecdotes to large health survey are discussed, actors seeking ways to tie data together | Broad goals make selecting key info difficult. Actors share statistics, personal experiences, expert opinion |

| Examining performance progress | Progress is hard to assess as the main goal is harm avoidance for an otherwise stubborn problem | Unstructured review of evidence on what progress is made, focusing mainly on gaps in approach | Progress difficult to track, street‐level partners show potential trade‐offs are not problematic, provide small win evidence |

| Exploring performance actions | Summit is concluded without agreeing on anything, although all partners have a better view of the problem | Summit leads to abolishment of targets and a shift towards a more network‐centric approach | Summit leads to re‐shaping the initiative in a more hierarchical fashion as councilors conclude learning stage is over |

Sports and Alcohol

The summit for Sports and Alcohol served as the final evaluation of the 4‐year trial period in which the various partners worked together on this initiative. The actors present included the alderman, participating sport clubs, the lead civil servants involved, the police, addiction support center, and four elected council members. The alderman sought to minimize his role, handing over the leadership of the session to the facilitators, and not speaking again until the end of the session.

The exploration of the goals centered on exploring the potential tensions between the community ambitions around sport clubs. The doctors and left‐wing politicians in the room prioritized “reduced alcohol consumption,” while the sports federation and right‐wing politicians prioritized financial independence of the clubs and their revenue from alcohol sales.

Rather than selecting one of these goals, the facilitators proposed to review the information about all of the ambitions. As the collaboration did not have specific targets beyond its overall ambition to reduce alcohol consumption, there were few key performance indicators to review, which meant that the group initially struggled to assess the progress made.

However, exchanging key pieces of information did provide some key insights. It turned out that the sport clubs solved the trade‐off between reducing alcohol while maintaining income by simply raising the prices on alcoholic beverages: People bought less beer, but still contributed equally to the club finances.

The group also struggled to capture by how much exactly the alcoholic consumption had decreased, as concerns were that especially youngsters simply moved to drinking elsewhere. Here, the police could provide a key piece of information as they observed a structural decline in alcoholic related incidents around the participating clubs. All participants saw this as a real win.

Interestingly, though the summit itself and the initiative overall were deemed successful, the discussion of the follow‐up actions centered on abolishing the collaborative approach to alcohol reduction. The elected council members present at the summit concluded that the participating clubs had learned a lot about reducing alcohol through their joint efforts, but that spreading these policies to clubs that had so far resisted joining the initiative required more hierarchical interventions.

Childhood Obesity

The actors participating in the Childhood Obesity summit numbered over 20 participants, including the alderman, senior civil servants, public health authority epidemiologists, family doctors, local council members, representatives of multiple schools, sport clubs, and grassroot health initiatives. Again, the alderman only opened the meeting and took a very passive role from there.

The debate about the goals focused on whether Body Mass Index (BMI) was the key indicator for the obesity problem or whether a broader perspective on physical plus emotional well‐being would be more appropriate. The street‐level partners (including schools and family doctors) felt that a broader perspective would be more relevant, yet the councilors preferred a focus on the tangible BMI‐targets.

The epidemiologists could offer extensive information on physical well‐being, thanks to an extensive monitory apparatus, but family doctors and school teachers felt these data did not provide sufficient evidence of the positive or negative impact of the various joint projects. These actors would share specifically their experiences about banning soda machines at schools or the ability of local community champions to reach kids. An epidemiologist countered that “these were really nice stories, but not real evidence.”

By moving the discussion toward “a day in the life of a child,” facilitators enabled the group to collectively assess the joint progress from all these different initiatives. The actors found they were successful in getting most kids three healthy meals a day and to do sports in the afternoon. However, they noticed that many parents rewarded kids with a candy after sports, identifying an opportunity for further improvement.

At the end of the summit, there were first calls for drastic actions, especially from the doctors and school principals. They argued the local government should ban unhealthy foods in schools. The most vocal proponents argued that since the majority of the participants at the summit favored this policy, it would be legitimate to implement it.

In his closing words, the alderman signaled that the local council would have to approve any rule changes and was itself bound by the limited power of government over schools. Indeed, there was no comprehensive soda ban, but the local council stopped pushing for a specific BMI target, although these data would still be monitored, and instead moved to emphasizing information about the healthy lifestyle among children.

Street Prostitution

The selection of actors present at the Street Prostitution summit was most importantly characterized by the actors who were absent. The summit was attended by the alderman, relevant policy advisors, elected councilors, the medical, social service, and police professionals on the ground, and a representative of the union of sex workers, but the sex workers themselves and the Department of Housing and Urban Development were missing.

The alderman explicitly aimed to involve the sex workers in the summit, moving the meeting to a less intimidating setting than city hall and ensuring anonymity. However, even after getting an in‐person invitation through the social workers, the sex workers ultimately choose not to attend. Instead, the social workers interviewed them about their experiences at the zone, putting their printed quotes on the wall of the summit room to make their voices visible if not heard.

The other absent actor was the local Housing and Urban Development, the department keen to close the zone and build houses on the site. This idea was gaining a lot of traction, putting a lot of pressure on the actors to prove the value of having a regulated prostitution zone. The Housing department argued that it was not a stakeholder in the current zone, just as its continuation was not their problem, and they only agreed to observe the summit rather than participate in it.

The summit started with a lengthy discussion of various goals of the zone, as they were not defined presently. Many of the goals suggested at the summit centered on accepting some undesirable activities to avoid worse social harms. For example, the police argued that they would rather not have any Street Prostitution at all, but that they also felt this low‐threshold zone enabled them to provide a safe place for sex workers working at the bottom of the market who would otherwise fall prey to exploitation.

Most of the information about the functioning of the zone came down to anecdotal evidence. The social workers present provided powerful testimonies about cases of human trafficking that were detected thanks to the safe and transparent space this zone offered. The police had some basic crime statistics, to show that the crime rate in the neighborhood was actually lower than average.

The local councilors, however, were ultimately keen to assess the progress made thanks to the zone. They specifically wanted to know whether social services on site had helped sex workers to “escape” this line of work. However, the professionals indicated that the sex workers working in the zone would all be long‐standing prostitution workers, often facing a complexity of deep‐rooted problems such as substance abuse. The professionals had no “miracle stories” and could only discuss how their presence prevented worse things from happening.

The participants found it difficult to formulate future actions, especially with the imminent threat of closure due to the housing development. The alderman concluded the summit by saying that “We may not have found solutions, but we did all get a better understanding of the problem.” However, to the great frustration of the professionals and sex workers involved, the Housing department later won enough political support to redevelop the zone.

The local government indicated that the summit had given them a good understanding of the needs of the sex workers, and would therefore provide extra transition support during the closing. However, the city decided not to offer an alternative location being offered and openly acknowledged that many sex workers would shift their activities to illegal locations.

Regime Change: Practical Interventions and Structural Shifts

As the three cases illustrate, the performance regime structure informs the routine practice (e.g. which actors are invited to the summit), but this practice can in turn shape the structure (e.g. agreeing new goals for the collaboration regime at the summit). Similarly, the collaboration regime is a product of its institutional context, but can also slowly bring about change in this context by altering ideas about what is possible and desirable (see discussion in this context of Bryson et al. (2020) of Giddens’ structuration theory).

However, the first and perhaps default scenario is that the summits have no impact. The actors gather to review their joint performance and may even build up some collective enthusiasm during the meeting, but this energy often dissipates when the meeting is over and the participants return to business‐as‐usual (Innes 1992). Arguably, this is what happened at the Street Prostitution summit. Whatever shared insight and momentum were created in the meeting were not enough to withstand the wider political pressures favoring a housing development.

Second, there may be an operational change after the summit. The insights generated at the summit lead to operational changes in the collaboration between the various actors, such as streamlining the coordination between the various services (Gerlak & Heikkila 2011).

Third, the collaborative summit could lead to changes in the strategic arrangements. This shifts parts of the performance regime, as new goals are introduced, new information is tracked, and the assessment criteria could be altered (Bryson et al. 2016). The Childhood Obesity case could be seen as an example of this strategic change, as the focus of the collaboration shifted from BMI to broader well‐being ambitions after the summit.

Finally, a summit could inspire systemic “constitutional” changes in the performance regime (Ostrom in McGinnis 2011), helping to redefine the nature of the collaboration. For example, a regime could move from an actor‐centric to a more network‐centric regime thanks to the insights of a summit. Reversely, the collaborative element of the regime may fall apart after a summit. This is what happened at the Sports and Alcohol summit, the politicians here concluded from the meeting that a more hierarchical approach would serve the next stage of the initiative better.

In rare circumstances, effective collaborative summits may contribute to building a new collaborative regime, which in turn reshapes the wider institutional context. The consecutive global AIDS summits, for example, over the span of several decades raised societal support for intervention and built frameworks for multilateral action. The consecutive global climate summits seek to similarly strengthen the global collaborative regime around environmental management, but the lackluster progress here illustrates how difficult affecting change can be.

The possibility of shaping structures through practical interventions gives entrepreneurial actors a lever for nudging the collaborative performance regime in their desired direction. Collaboratively minded actors could focus on designing collaborative summits that engender a more network‐centric perspective (Bryson et al. 2020), while more independently minded actors might seek to sabotage such interventions.

However, the development of collaborative performance regimes and the impact of summits cannot be easily shaped or predicted. The limited impact of the Street Prostitution summit, for example, was arguably predetermined by the refusal of the Housing department to take part and no process intervention could have changed that. The outcomes of the Sports and Alcohol, where the collaboration was disbanded despite its success, may not have been predicted by any of the actors.

Discussion and Conclusion

This article provided the first conceptualization of collaborative performance regimes by making a distinction between actor‐centric regimes, network‐centric regimes, and hybrid performance regimes. The article also offered the first conceptualization of collaborative performance summits, a key routine for actors working on the same issue to jointly explicate goals, exchange performance information, examine progress, and explore actions. Finally, the article explored how the collaborative performance structures and practices affect each other, showing what changes do or do not occur.

The article drew on the combined strength of the collaborative governance and performance management literature to inform these concepts. In its breadth, the article at points only touched on the insights these different strands of the literature can offer each other. For example, much more has been said about the use of performance information within organizations that could be very relevant to understanding performance information between organizations.

Equally, the cases were here only used as practical illustrations of the theoretical argument. More systematic research designs, employing other methodologies next to the action research approach followed here and tracing the impact of the summits over time, are required to further test and substantiate the propositions forwarded here.

On the whole, this article generates three different lines of questioning for future research. First, this first conceptualization of different collaborative performance regimes can contribute to a refined categorization of different “species” of collaboration while at the same time appreciating that many collaborations will not be pure ideal types.

Second, this article hopes to create momentum for the further study of collaborative summits as popular, but potentially challenging routines within collaborations. The exploration of three such summits within one city and one policy domain already identified some interesting dynamics, but it would be useful to explore these dynamics across different geographies, levels of government, and policy domains.

Finally, future studies should continue to explore how collaborative performance regimes, summits, and routines evolve over time. Getting a better understanding of this dynamic of change and continuity is crucial for both scholars and practitioners seeking to better understand collaborative performance.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mijke van de Noort, who as a graduate student was instrumental in shaping and observing the summits discussed in this article, and all the officials and citizens who participated in the events. The authors would also like to thank Eva Sorensen, Shui Yan Tang, Paul't Hart, the participants of the Consortium for Collaborative Governance 2019 meeting, and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on earlier drafts of this article. This article was made possible by funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (Grant Agreement No. 694266).

Biographies

Scott Douglas is an assistant professor of public management at the Utrecht School of Governance. His research focuses on the performance management of collaborations, working closely with public sector organizations tackling issues such as radicalization, educational inequality, and obesity.

Email: s.c.douglas@uu.nl

Christopher Ansell is a Professor of Political Science at the University of California, Berkeley. His research focuses on understanding how organizations, institutions, and communities can engage effectively in democratic governance in the face of conflict, uncertainty, and complexity.

Email: cansell@berkeley.edu

Contributor Information

Scott Douglas, Email: s.c.douglas@uu.nl.

Chris Ansell, Email: cansell@berkeley.edu.

References

- Ansell, Chris , and Gash Alison. 2008. Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18(4): 543–71. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, L.B. , Boesen A., and Pedersen L.H.. 2016. Performance in Public Organizations: Clarifying the Conceptual Space. Public Administration Review 76(6): 852–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell, Chris , and Gash Alison. 2012. Stewards, Mediators, and Catalysts: Toward a Model of Collaborative Leadership. The Innovation Journal 17(1): 2. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell, Chris , Doberstein Cary, Henderson Hailey, Siddiki Saba, and ’t Hart Paul. 2020. Understanding Inclusion in Collaborative Governance: A Mixed Methods Approach. Policy and Society: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Battaglio, R. Paul , and Hall Jeremy L.. 2018. A Fistful of Data: Unpacking the Performance Predicament. Public Administration Review 78(5): 665–8. [Google Scholar]

- Battaglio, R. Paul , and Hall Jeremy L.. 2010. Collaborating for Performance: Or Can There Exist Such a Thing as Collaboration Stat? International Public Management Journal 13(4): 429–70. [Google Scholar]

- Behn, Robert D. 2003. Why Measure Performance? Different Purposes Require Different Measures. Public Administration Review 63(5): 586–606. [Google Scholar]

- Behn, Robert D. 2014. The Performance Stat Potential: A Leadership Strategy for Producing Results. Brookings Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, A.O.M , and Parsons B.M.. 2013. Making Connections: Performance Regimes and Extreme Events. Public Administration Review 73(1): 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Bryson, John M. , and Crosby Barbara C.. 1993. Policy Planning and the Design and Use of Forums, Arenas, and Courts. Environment and Planning. B, Planning & Design 20(2): 175–94. [Google Scholar]

- Bryson, John M. , Ackermann Fran, and Eden Colin. 2016. Discovering Collaborative Advantage: The Contributions of Goal Categories and Visual Strategy Mapping. Public Administration Review 76(6): 912–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bryson, J. , Crosby M., C B., and Seo D.. 2020. Using a Design Approach to Create Collaborative Governance. Policy & Politics 48(1): 167–189. [Google Scholar]

- Chenoweth, Erica , and Clarke Susan E.. 2010. All Terrorism is Local: Resources, Nested Institutions, and Governance for Urban Homeland Security in the American Federal System. Political Research Quarterly 63(3): 495–507. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Taehyon , and Robertson Peter J.. 2013. Deliberation and Decision in Collaborative Governance: A Simulation of Approaches to Mitigate Power Imbalance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 24(2): 495–518. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, Kirk , and Nabatchi Tina. 2015. Evaluating the Productivity of Collaborative Governance Regimes: A Performance Matrix. Public Performance and Management Review 38(4): 717–47. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, Kirk , Nabatchi Tina, and Balogh Stephen. 2012. An Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 22(1): 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Gash, Alison . 2017. Cohering Collaborative Governance. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 27(1): 213–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gerlak, Andrea K. , and Heikkila Tanya. 2011. Building a Theory of Learning in Collaboratives: Evidence from the Everglades Restoration Program. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 21(4): 619–44. [Google Scholar]

- Gerrish, Ed . 2016. The Impact of Performance Management on Performance in Public Organizations: A Meta‐Analysis. Public Administration Review 76(1): 48–66. [Google Scholar]

- Graddy, Elizabeth A. , and Chen Bin. 2009. Partner Selection and the Effectiveness of Interorganizational Collaborations. The Collaborative Public Manager: New Ideas for the Twenty‐First Century: 53–70. [Google Scholar]

- Head, Brian W. , and Alford John. 2015. Wicked Problems: Implications for Public Policy and Management. Administration & Society 47(6): 711–39. [Google Scholar]

- Innes, Judith E. 1992. Group Processes and the Social Construction of Growth Management: Florida, Vermont, and New Jersey. Journal of the American Planning Association 58(4): 440–53. [Google Scholar]

- Innes, Judith E. , and Booher David E.. 2010. Planning with Complexity: An Introduction to Collaborative Rationality for Public Policy. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsen, Mads. L. , Baekgaard Martin, Moynihan Donald P., and van Loon Nina. 2017. Making Sense of Performance Regimes: Rebalancing External Accountability and Internal Learning. Perspectives on Public Management and Governance 1(2): 127–41. [Google Scholar]

- James, Oliver , Olsen Asmus Leth, Moynihan Donald, and Van Ryzin Gregg G.. 2020. Behavioral Public Performance: How People Make Sense of Government Metrics. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, E.T., Jr. , and Hall J.L.. 2012. EvidenceBased Practice and the Use of Information in State Agency Decision Making. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 22(2): 245–66. [Google Scholar]

- Jos, Philip H. , and Watson Annette. 2019. Privileging Knowledge Claims in Collaborative Regulatory Management: An Ethnography of Marginalization. Administration & Society 51(3): 371–403. [Google Scholar]

- Kristiansen, Mads Bøge , Dahler‐Larsen Peter, and Ghin Eva Moll. 2017. On the Dynamic Nature of Performance Management Regimes. Administration & Society: 0095399717716709. [Google Scholar]

- Klijn, E.H. , and Skelcher C.. 2007. Democracy and Governance Networks: Compatible or Not? Public Administration 85(3): 587–608. [Google Scholar]

- Kroll, Alexander , and Moynihan Donald P.. 2018. The Design and Practice of Integrating Evidence: Connecting Performance Management with Program Evaluation. Public Administration Review 78(2): 183–94. [Google Scholar]

- Termeer, C.J. , and Dewulf A.. 2019. A Small Wins Framework to Overcome the Evaluation Paradox of Governing Wicked Problems. Policy and Society 38(2): 298–314. [Google Scholar]

- Laihonen, Harri , and Mäntylä Sari. 2017. Principles of Performance Dialogue in Public Administration. International Journal of Public Sector Management 30(5): 414–28. [Google Scholar]

- March, James G. , and Simon Herbert A.. 1993. Organizations, 1958. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis, Michael D. 2011. An Introduction to IAD and the Language of the Ostrom Workshop: A Simple Guide to a Complex Framework. Policy Studies Journal 39(1): 169–83. [Google Scholar]

- McNamara, Madeleine . 2012. Starting to Untangle the Web of Cooperation, Coordination, and Collaboration: A Framework for Public Managers. International Journal of Public Administration 35(6): 389–401. [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan, Donald P. 2005. Goal‐Based Learning and the Future of Performance Management. Public Administration Review 65(2): 203–16. [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan, D.P. , Fernandez S., Kim S., LeRoux K.M., Piotrowski S.J., Wright B.E., and Yang K.. 2011. Performance Regimes Amidst Governance Complexity. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 21(suppl_1): i141–55. [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan, Donald.P. , and Kroll Alexander. 2016. Performance Management Routines that Work? An Early Assessment of the GPRA Modernization Act. Public Administration Review 76(2): 314–23. [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan, Donald P. , Baekgaard Martin, and Jakobsen Mads Leth. 2019. Tackling the Performance Regime Paradox: A Problem‐Solving Approach Engages Professional Goal‐Based Learning. Public Administration Review. [Google Scholar]

- Noordegraaf, M. , Douglas S., Bos A., and Klem W.. 2017. How to Evaluate the Governance of Transboundary Problems? Assessing a National Counterterrorism Strategy. Evaluation 23(4): 389–406. [Google Scholar]

- Page, Stephen B. , Stone Melissa M., Bryson John M., and Crosby Barbara C.. 2015. Public Value Creation by Cross‐Sector Collaborations: A Framework and Challenges of Assessment. Public Administration 93(3): 715–32. [Google Scholar]

- Poocharoen, Ora‐orn , and Wong Norma Hoi‐Lam. 2016. Performance Management of Collaborative Projects: The Stronger the Collaboration, the Less is Measured. Public Performance & Management Review 39(3): 607–29. [Google Scholar]

- Provan, Keith G. , and Kenis Patrick. 2010. Modes of Network Governance: Structure, Management, and Effectiveness. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18(2): 229–52. [Google Scholar]

- Provan, Keith G. , and Milward H. Brinton. 2001. Do Networks Really Work? A Framework for Evaluating Public‐Sector Organizational Networks. Public Administration Review 61(4): 414–23. [Google Scholar]

- Quick, Kathryn S. , and Sandfort Jodi. 2014. Learning to Facilitate Deliberation: Practicing the Art of Hosting. Critical Policy Studies 8(3): 300–22. [Google Scholar]

- Rajala, Tomi , Haapala Petra, and Laihonen Harri. 2017. Challenges of Performance Dialogue in Local Government. Paper presented at the IRSPM, 12–21 April, Budapest, Hungary.

- Sørensen, Eva , and Torfing Jacob, eds. 2016. Theories of Democratic Network Governance. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Stringer, Ernest T. 2013. Action Research. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Talbot, Colin . 2010. Theories of Performance: Organizational and Service Improvement in the Public Domain. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Van Buuren, Arwin . 2009. Knowledge for Governance, Governance of Knowledge: Inclusive Knowledge Management in Collaborative Governance Processes. International Public Management Journal 12(2): 208–35. [Google Scholar]