Abstract

The Eph family of receptor tyrosine kinases and their membrane-bound ligands, the ephrins, have been implicated in regulating cell adhesion and migration during development by mediating cell-to-cell signaling events. Genetic evidence suggests that ephrins may transduce signals and become tyrosine phosphorylated during embryogenesis. However, the induction and functional significance of ephrin phosphorylation is not yet clear. Here, we report that when we used ectopically expressed proteins, we found that an activated fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptor associated with and induced the phosphorylation of ephrin B1 on tyrosine. Moreover, this phosphorylation reduced the ability of overexpressed ephrin B1 to reduce cell adhesion. In addition, we identified a region in the cytoplasmic tail of ephrin B1 that is critical for interaction with the FGF receptor; we also report FGF-induced phosphorylation of ephrins in a neural tissue. This is the first demonstration of communication between the FGF receptor family and the Eph ligand family and implicates cross talk between these two cell surface molecules in regulating cell adhesion.

Cell adhesion events, coordinated both spatially and temporally, are critical to the development and maintenance of the tissue structures of an organism. Interactions with other cells and extracellular matrix components govern the growth, differentiation, migration, and ultimate location and function of a given cell. An increasing number of proteins expressed at the cell surface have been implicated in regulating cell adhesion and movement within specific developmental contexts. For example, considerable progress has been made in identifying cell surface proteins which regulate neurite outgrowth and pathfinding during nervous system development (9). These proteins include classic cell adhesion molecules such as the neural cell adhesion molecules of the immunoglobulin superfamily (58, 69), members of the cadherin superfamily (20), and integrins (47), as well as a growing number of other protein families including collapsins/semaphorins, neuropilins, netrin receptors (10, 11, 57), various peptide growth factor receptors (49), and receptor-type tyrosine phosphatases (13, 42). These cell surface proteins respond to molecular guidance cues which can arise locally or diffuse from distant sources. In one such case, control of growth cone physiology is achieved at the most intimate level of cell-to-cell contact, when neuronal cell surface proteins interact with attractive or repulsive cues present on the surface of a neighboring cell.

The Eph family of receptor tyrosine kinases and their membrane-associated activating ligands, the ephrins, are recent additions to this growing repertoire of cell surface proteins which mediate cell-to-cell interactions. They are highly expressed in the developing and adult nervous system and have been implicated in regulating cell adhesion events in both neural and nonneural tissues including neural crest cell migration (43, 62, 71), hindbrain segmentation (4, 5, 23, 75), angiogenesis (55, 72), and somitogenesis (19). At least 14 distinct Eph receptors have been identified across vertebrate and invertebrate species and are classified as type A or B depending on the ligand that they bind. Eph receptors are characterized by an intracellular catalytic domain and an extracellular cysteine-rich domain, two fibronectin type III repeats, and an amino-terminal ephrin-binding region (45, 46, 80). To date, all eight ephrins identified are membrane-bound proteins, possessing either a glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor (ephrin A subclass, which binds to type A Eph receptors) or a transmembrane domain (ephrin B subclass, which binds to type B Eph receptors). While there is little cross-reactivity between class A and B molecules, promiscuous receptor-ligand interactions occur within each class (22).

In addition to numerous receptor-ligand-binding studies, elucidation of both partially overlapping and completely reciprocal expression patterns has indicated that various Eph receptors and ephrins regulate axon targeting, cell migration, and pattern formation by promoting repulsive and attractive intercellular interactions as well (60). Indeed, the potential dual nature of their interactions is thought to be a growing paradigm among cell surface proteins that play multiple roles during development (7, 24, 68). Ephrins activate their cognate Eph receptors most efficiently when they are membrane bound or presented in an artificially clustered state which mimics membrane attachment (22). Hence, the cell-to-cell communication they facilitate is intimately linked to cell-to-cell contact. Receptor-ligand activation studies have further indicated that in general, multimeric aggregation of an Eph receptor is optimal for its activation. Interestingly, the EphB-type receptors have a higher requirement for aggregation of their cognate ephrin B ligands (22). In fact, only a multimeric complex of ephrin B1 could induce the recruitment of a downstream phosphatase molecule to activated EphB1 receptors and concommitantly promote cell attachment (65).

The ephrin B ligands are type I transmembrane proteins which themselves are thought to transduce an intracellular signal(s) upon Eph receptor binding. The carboxy-terminal 33 amino acids of the three known ephrin B molecules are nearly identical, suggesting a signaling function. This region also contains five conserved tyrosine residues (21). Upon contact with the extracellular domain of a cognate Eph receptor, ephrin B molecules induce receptor activation and autophosphorylation on tyrosine and become tyrosine phosphorylated themselves, suggesting a bidirectional mode of signaling (33). Genetic evidence has revealed that the EphB2 receptor extracellular domain may send a reverse signal through the ephrin B molecules to which it binds (30). Deletion of the kinase domain of the EphB2 receptor did not affect its function in guiding anterior comissure axons expressing ephrin B1. EphB2 is expressed in adjacent cells which serve as a migration substrate. While ephrin B molecules become phosphorylated on tyrosine during embryogenesis (6), the mechanisms by which this modification occurs are unknown. As with activated Eph receptors, phosphorylated tyrosine residues in the ephrin cytoplasmic domain may interact with other signaling molecules. Although phosphorylation of the ephrin B1 cytoplasmic domain was detected in fibroblast cells stimulated with platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), in cells overexpressing c-src, and in cells exposed to clustered EphB2 ectodomain (6, 33), this modification had no effects on cellular physiology. Thus, until now, the physiological significance of ephrin phosphorylation has remained unclear.

We previously identified and characterized a Xenopus laevis homologue of ephrin B1, XLerk (37). The 95% homology of its cytoplasmic domain to that of mammalian family members further suggested an important evolutionarily conserved function for this domain. While also highly expressed in developing neural structures including the hindbrain and retina, x-ephrin B1 (XLerk) expression was elevated early in development during gastrulation. This indicated a possible role in regulating cell adhesion during the rearrangement of embryonic blastomere cells into developmentally specific germ layers. Ectopic overexpression of x-ephrin B1 in Xenopus embryos caused a marked dissociation of embryonic cells just prior to gastrulation (in the earlier blastula stage), confirming that x-ephrin B1 could indeed modify cell adhesion (38). x-Ephrin B1 not only is an activating ligand for an Eph receptor but also exhibits the ability to signal and regulate cell adhesion.

Xenopus embryos provide a useful expression system to examine x-ephrin B1 function both biochemically and morphologically. Previously, we have found that treatment with fibroblast growth factor (FGF) reversed the cell-dissociative effect of x-ephrin B1 in Xenopus embryonic tissue explants (38). From this work, we hypothesized that the FGF receptor may modulate the function of x-ephrin B1 in regulating cell adhesion. Here, we demonstrate that FGF receptor activation inhibits x-ephrin B1-induced cell dissociation in Xenopus embryos. We show that the FGF receptor associates with and induces the phosphorylation of x-ephrin B1. We also define critical residues within a conserved region of the intracellular domain necessary for this interaction. In neural tissue, treatment of retina with FGF induces tyrosine phosphorylation of endogenous ephrin B. Our results provide the first example of a functional and physical interaction between the FGF tyrosine kinase family of receptors and the ephrin B family of cell surface ligands and implicate their cross talk in regulating adhesion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids and mutagenesis of cDNA.

cDNA encoding wild-type x-ephrin B1 was subcloned into three plasmids as follows: HindIII and BamHI restriction sites of plasmid pSP64A as previously described (38); EcoRI and NotI restriction sites of plasmid pSP64Aten (a gift from Malcolm Whitman and D. Melton, Harvard University); and EcoRI and NotI restriction sites of pSP64Aten(−HindIII), a derivative of pSP64A in which the HindIII site has been abolished by restriction enzyme digestion, Klenow fill-in, and religation reactions. Carboxy-terminal truncation mutants of wild-type x-ephrin B1 were generated by PCR with plasmid pSP64A x-ephrin B1 as the template and the sense primer 5′-GGACGGCTTCTTCAACTCC-3′, in conjunction with antisense primers that generated a stop codon at the appropriate positions. PCR products were purified with the agarose gel DNA extraction kit as specified by the manufacturer (Boehringer Mannheim), digested with PacI and EcoRV, repurified, and ligated into the PacI and EcoRV sites of pSP64Aten(−HindIII) x-ephrin B1. Single-point mutants were also generated by the PCR method. Mutants WTY305F and WTY310F were made with pSP64Aten x-ephrin B1 as a template. The double mutant WTY305FY310F was made with WTY305F as a template to generate a second mutation at position 310. PCR products were purified, digested with PacI and SacI, repurified, and subcloned into the PacI and SacI sites of pSP64A x-ephrinB1. DNA sequencing was performed to confirm the identity of each mutant.

cDNAs encoding the wild-type and mutant forms of the Xenopus FGF type R1 and R2 receptors were cloned into plasmid pCS2+ (53). Only the mutant FGFR1C289R/K420A was subcloned into plasmid pSP64T3. Plasmids pGEMHE2PDGFRa, pGEMtorsoACT, and pSP64AtenMekACT were gifts from M. Mercola (Harvard University Medical School), D. Morrison (National Cancer Institute), and Y. Gotoh (Tokyo University), respectively.

Preparation of synthetic RNA, microinjection of Xenopus embryos, and animal cap explant assay.

For all embryo injections and manipulations, Xenopus embryos were obtained by in vitro fertilization and capped mRNA was synthesized and injected into embryos at the two-cell stage as previously described (38). All mRNA was made by using either the SP6 mMessage mMachine or T7 Megascript kit as specified by the manufacturer (Ambion). pSP64A plasmids containing x-ephrin B1 constructs were linearized with EcoRI, and pSP64Aten(−HindIII) plasmids were linearized with XbaI. FGF receptor constructs in pCS2+ were linearized with NotI, and pSP64T3 containing FGFR1C289R/K420A was linearized with BamHI. pSP64AtenMekACT and pGEMtorsoACT were linearized with EcoRI, and pGEMHE2PDGFRa was linearized with NheI.

Embryos were injected with approximately 5 ng of RNA. For ectopic expression of two different proteins, 2.5-ng portions of each RNA were coinjected, with the exception of MekACT (100 pg was coinjected with 5 ng of x-ephrin B1 RNA). For expression of three different proteins, 2.5 ng of RNA encoding x-ephrin B1 was coinjected with 1.25 ng each of the other two RNAs. The criterion for loss of cell adhesion was defined as 15 to 20% animal pole cells showing a dispersive or blebbing phenotype. This phenotype results in 20 to 80% of the animal pole area being affected and tissue involution into the blastocoel upon fixation with 2% paraformaldehyde.

Animal pole tissue explants from injected embryos were made at stage 8 of development as described previously (38). Blastomere cells were dissociated and exposed to either recombinant human basic FGF (Prepro Tech) (250 ng/ml), soluble x-EphB1-Fc (50 μg/ml), or human immunoglobulin G (IgG) (The Binding Site) (50 μg/ml) in MMR buffer (100 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM HEPES [pH 7.4]) for 45 min at room temperature before solubilization in lysis buffer. The protein concentration of lysate samples was determined with a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein kit as specified by the manufacturer (Pierce), and samples with equivalent amounts of total protein were immunoprecipitated. x-Eph B1-Fc protein and human IgG were preclustered with 100 μg of goat anti-human IgG (Boehringer Mannheim) per ml for 1 h prior to use.

Fusion proteins.

To generate the soluble fusion proteins x-EphB1–Fc and x-ephrin B1–Fc, cDNAs encoding the extracellular domains of Xenopus EphB1 and x-ephrin B1 were subcloned into the mammalian expression vector pCMV-Ig (a gift from Pantelis Tsoulfas, University of Miami), which creates a chimeric protein with the Fc domain of human IgG. Each plasmid was transfected into 293T cell monolayers with Lipofectamine as specified by the manufacturer (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.). At 1 day posttransfection, cells were grown in Optimem medium containing 2% serum with a low Ig content (GibcoBRL). The medium was harvested 5 to 7 days later and incubated with protein A-Sepharose (GibcoBRL) at 4°C for 4 to 16 h. Fusion proteins were eluted with 100 mM glycine (pH 3.0) and then neutralized to pH 7.5 with 1 M Tris (pH 11). Fusion proteins were assessed for purity and concentration by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining.

Antibodies.

A rabbit polyclonal antibody, anti-x-ephrin B1, was generated to the extracellular domain of x-ephrin B1 by using purified x-ephrin B1–Fc as the immunogen. A rabbit polyclonal antibody was also generated to the carboxy terminus of x-ephrin B1 (anti-Lerk2) by using the C-terminal 14-amino-acid peptide conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin. Anti-Lerk2 was also purchased from Santa Cruz Inc. Antibodies to torso and PDGF receptors were gifts from D. Morrison and M. Mercola, respectively. A monoclonal antibody to the FGF receptor has been described previously (53). Antibody specific for phosphomapkinase was purchased from New England Biolabs. Antiphosphotyrosine antibody 4G10 was purchased from UBI. Anti-glutathione S-transferase antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Inc. Goat anti-human IgG was purchased from Boehringer Manheim.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis.

Embryonic lysates were prepared with cold lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 2 mM EDTA, 5 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM aprotinin, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.02 mM leupeptin) as previously described, followed by extraction with Freon (Sigma) at a 1:1 (vol/vol) ratio. All immunoprecipitations were conducted on 20 to 30 embryo equivalents with the indicated antibodies at 4°C for 4 to 16 h. All immunoprecipitates were washed in RIPA buffer (lysis buffer adjusted to 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS] and 0.5% deoxycholate) except for those described in Fig. 3b and c, which were washed with lysis buffer. Anti-x-ephrin B1 antibody was used for immunoprecipitations, and anti-Lerk2 antibody was used for Western blot analysis. Two embryos equivalents were examined for direct lysate analysis. For Mek experiments, buffer A was lysis buffer and buffer B was mitogen-activated protein MAP kinase buffer (44). SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (8.5% polyacrylamide) was used in all cases except for the Mek experiment, which required SDS-PAGE analysis with 15% polyacrylamide. Western blots with antiphosphotyrosine antibody were conducted with buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 8], 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20) containing 2% goat serum, 1% fish gelatin, and 1% bovine serum albumin. All other blots used 5% milk. Proteins were visualized by using an appropriate secondary antibody coupled to horseradish peroxidase, followed by application of enhanced chemiluminescence reagents as specified by the manufacturer (Amersham). The blots were stripped and washed if probing with a second antibody was necessary.

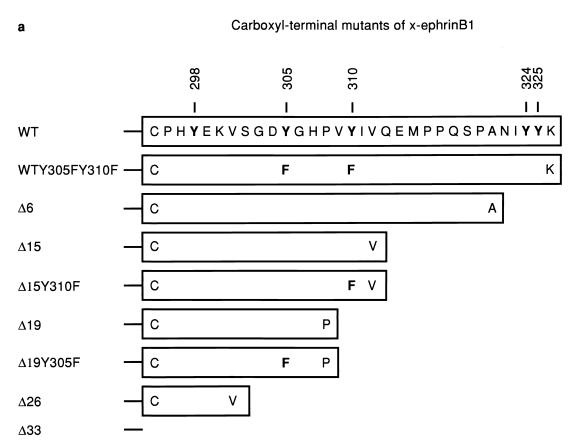

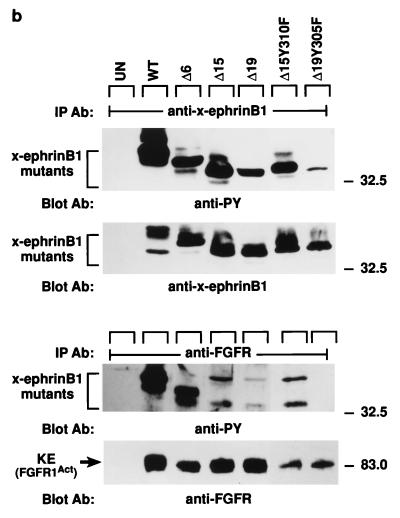

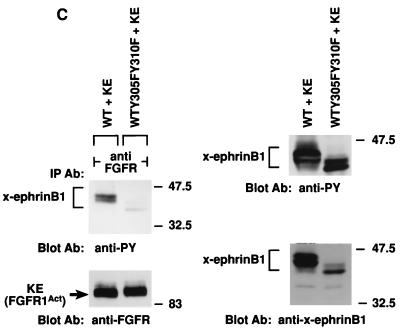

FIG. 3.

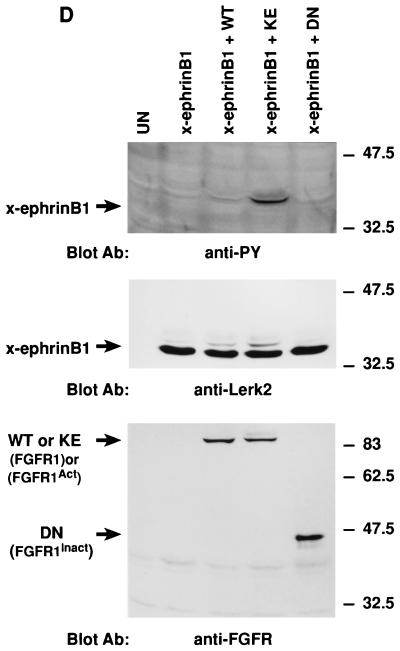

Association of x-ephrin B1 mutants with the FGF receptor. (a) A series of X-ephrin B1 cDNAs were constructed to encode proteins with mutations in their cytoplasmic domains. The last 33 amino acids of wild-type (WT) x-ephrin B1 are shown. Numbers indicate the positions of the five conserved tyrosine residues (bold). (b) Embryos were coinjected with RNA encoding FGFR1-K562E (KE) in combination with each x-ephrin B1 mutant. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with either the x-ephrin-specific antibody (IP Ab: anti-x-ephrinB1 [top panels]) or the FGF receptor antibody (IP Ab: anti-FGFR [bottom panels]), transferred, and blotted with phosphotyrosine-specific antibodies (anti-PY) to visualize the phosphorylated ephrin mutants (first and third panels from top) or with the precipitating antibody (second and fourth panels from top). (c) Embryos were coinjected with RNA encoding either wild-type x-ephrin B1 (WT) or the WTY305FY310F double mutant and the FGFR1-K562E (KE). (Left panel) Lysates were immunoprecipitated with the FGF receptor-specific antibody (IP Ab: anti-FGFR), transferred, and probed with phosphotyrosine specific antibodies (Blot Ab: anti-PY) or FGF receptor antibodies (Blot Ab: anti-FGFR) as indicated. (right panel) Control lysates from coinjected embryos that were analyzed directly by Western blotting with antiphosphotyrosine (top right) or x-ephrin B1 (bottom right) antibodies. Note the reduction in association of WTY305FY310F and Δ19Y305F with FGF receptor in panels b and c. (d) Morphology of embryos coinjected with KE and wild-type x-ephrin B1 (WT), a tyrosine 305 mutant (WTY305F), a tyrosine 310 mutant (WTY310F), or a tyrosine 305 and 310 double mutant (WTY305FY310F). The graph indicates the percentage of embryos injected with the wild type or indicated mutants that display the dissociated or rescued phenotype. Error bars represent standard deviations, and the absence or presence of coinjected activated FGF receptor RNA is indicated as KE − or +. Note that double-mutant-induced cell dissociation is not effectively rescued by KE. Dissociation was scored by at least 15 to 20% of the animal pole region displaying the deadhesion phenotype. These are representative of three separate experiments and a total of 34 to 36 injected embryos for each sample.

Retina assays.

Retinas were harvested from day 10 chicken embryos (Truslow Farms Inc., Chestertown, Mass.) as described elsewhere (32) for incubation with recombinant human basic FGF (Prepro Tech) at 250 ng/ml. The retinas were then solubilized with lysis buffer and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The protein concentration of lysate samples determined by using the BCA protein kit and samples of equivalent total protein were incubated with protein A-Sepharose for 1 h at 4°C for preclearing. After removal of Sepharose by centrifugation, lysates were incubated with 5 μg of x-EphB1–Fc fusion protein that had been preincubated for 1 h at 4°C with protein A-Sepharose. Lysates were rotated in the cold for 16 h. After centrifugation to remove lysate, Sepharose beads were washed four times with lysis buffer. Proteins contained in the final pellet were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

RESULTS

FGF receptor activation causes x-ephrin B1 phosphorylation on tyrosine and inhibits cell dissociation.

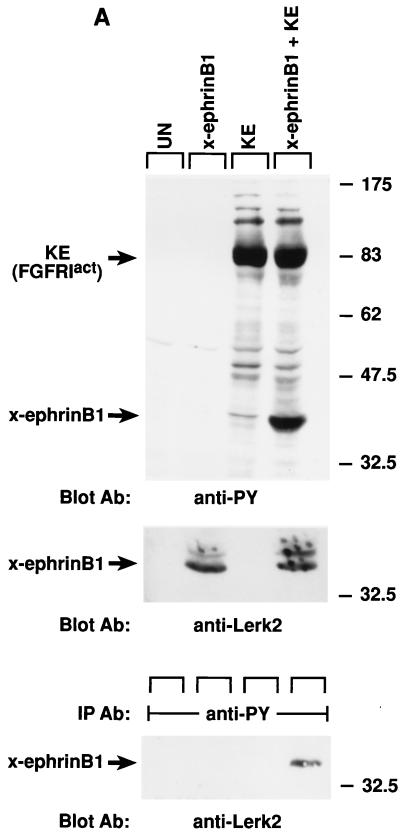

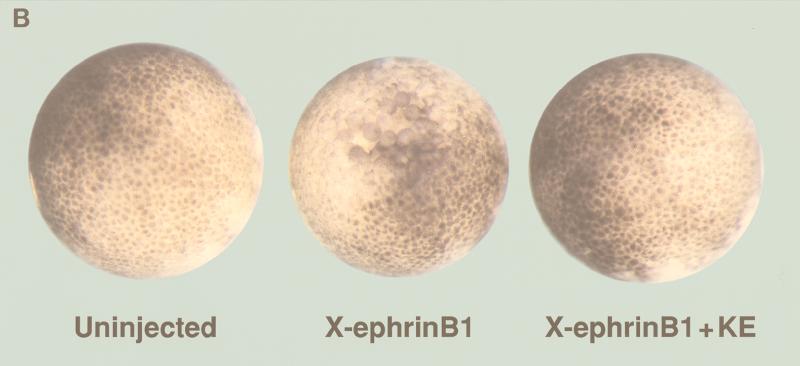

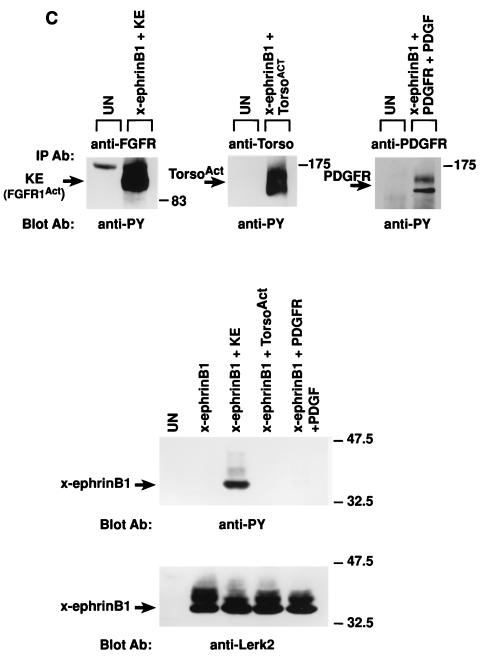

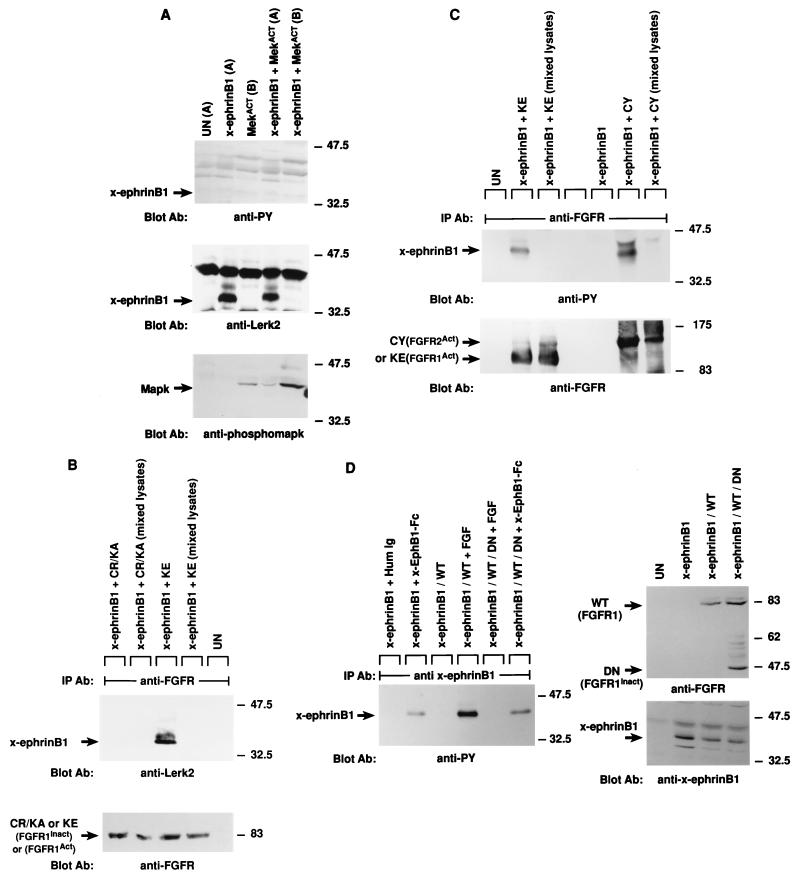

In Xenopus, the developmental effects of FGF on early embryonic tissue can be mimicked by treating ectodermal animal cap tissue explants from blastula stage embryos with exogenous FGF (39, 61). Thus, in this explant system, FGF receptor activation can be effectively initiated. Since we had observed that FGF treatment reversed the ability of x-ephrin B1 to dissociate embryonic cells in such a tissue explant (38), we inferred that FGF receptor activation was a likely corresponding event. To confirm that FGF receptor activation correlated with the inhibitory effects of FGF on x-ephrin B1 function, a constitutively activated form of Xenopus FGF receptor type I, FGFRK562E (KE) (53), was coexpressed with x-ephrin B1 in Xenopus embryos. Synthetic RNA (2.5 ng) encoding x-ephrin B1 was injected into cleaving embryos at the two-cell stage in the absence or presence of synthetic RNA (2.5 ng) encoding KE. Dissociation of embryonic cells was induced by x-ephrin B1 expression alone at the blastula stage of development (stage 8) (Fig. 1B). In contrast, coexpression of x-ephrin B1 with KE inhibited cell dissociation and generated embryos that were similar in appearance to uninjected control embryos (Fig. 1B). Expression of KE alone had no effect on whole embryos at this stage (not shown). When embryonic lysates were examined by Western blot analysis (Fig. 1A), the x-ephrin B1 (Lerk-2) expression level was the same whether expressed alone or coexpressed with KE, indicating that a reduction in x-ephrin B1 expression was not the cause of reduced cell dissociation. When lysates were examined either directly or by immunoprecipitation with an antiphosphotyrosine-specific antibody, x-ephrin B1 was not detectably phosphorylated when expressed alone but became highly phosphorylated in the presence of the activated FGF receptor (Fig. 1A). Neither cell dissociation nor the non-tyrosine-phosphorylated state of x-ephrin B1 was altered when x-ephrin B1 was coexpressed with the wild-type form of the FGF receptor or a truncated, kinase-deficient form of the FGF receptor lacking the cytoplasmic domain (Fig. 1D) (53). However, x-ephrin B1 was phosphorylated when coexpressed with the wild-type FGF receptor that was activated in response to exogenously added FGF (Fig. 2D). Taken together, x-ephrin B1 was tyrosine phosphorylated only when the FGF receptor was present in an activated state. Furthermore, this modification correlated with a block in the ability of x-ephrin B1 to induce cell dissociation, indicating that phosphorylation regulates this specific function of an ephrin B-type molecule.

FIG. 1.

Tyrosine phosphorylation of x-ephrin B1 by the FGF receptor and rescue of cell dissociation. Xenopus embryos were left uninjected (UN) or injected with RNA encoding x-ephrin B1, an activated form of the FGF receptor type 1 termed FGFR1-K562E (KE), or both. (A) Embryonic lysates were analyzed directly (top and middle panels) or immunoprecipitated with antibody to phosphotyrosine (IP Ab: anti-PY) (bottom panel) and separated by SDS-PAGE (8.5% polyacrylamide). Western blot analysis was conducted with antiphosphotyrosine antibody (Blot Ab: anti-PY), and the blot was stripped for reprobing with antibody to the carboxyl-terminus of x-ephrin B1 (Blot Ab: anti-Lerk2). Molecular size marker positions (kilodaltons) are indicated. Activated FGF receptor (95 kDa) and phosphorylated x-ephrin B1 (38 kDa) are indicated by arrows. (B) Embryonic cell adhesion was assessed at stage 9 of uninjected embryos and embryos expressing x-ephrin B1 alone or with activated FGFR1 (KE). Cell adhesion was disrupted only when x-ephrin B1 was expressed alone. (C) Embryos were injected with RNA encoding x-ephrin B1 alone or coinjected with RNA encoding either KE (FGFR1Act), PDGF receptor, or the TorsoAct receptor. Embryos expressing the PDGF receptor were incubated with PDGF (100 ng/ml). Receptors were immunoprecipitated from lysates with specific antibodies (IP Ab: anti-FGFR, anti-Torso, or anti-PDGFR), and these immune complexes were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with antiphosphotyrosine antibodies (Blot Ab: anti-PY) (top panel). Embryonic lysates were analyzed directly by SDS-PAGE and Western analysis with antiphosphotyrosine antibodies (Blot Ab: anti-PY) (middle panel) and anti-ephrinB1 antibodies (Blot Ab: anti-Lerk2) (bottom panel). Arrows indicate bands representing the different receptors and x-ephrin B1. (D) Embryos were injected with RNA encoding x-ephrin B1 alone or coinjected with RNA encoding either KE, the wild-type FGFR1 (WT), or a truncated, kinase-deficient FGFR1 (DN). Lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting by using the indicated antibodies (Blot Ab:) (Top panel, anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies; middle panel, anti-ephrin B1 antibodies; bottom panel, anti-FGF receptor antibodies). Arrows indicate the corresponding proteins. Note that tyrosine phosphorylation of x-ephrin B1 occurs with an activated FGFR.

FIG. 2.

Lack of MAP kinase-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of x-ephrin B1, and existence of stable interaction between tyrosine-phosphorylated x-ephrin B1 and the FGF receptor. (A) Embryos were left uninjected (UN) or injected with RNA encoding x-ephrin B1, activated Mek (MekACT), or both. Embryos were lysed with the indicated buffers (buffer A, a lysis buffer that solublizes maximal amounts of ephrin B; buffer B, a buffer that maximally solubilizes activated MAP kinase) for Western blot analysis with antiphosphotyrosine antibody (Blot Ab: anti-PY) (top panel) and anti-Lerk2 antibodies (Blot Ab: anti-Lerk2) (middle panel) and antibody specific for phospho-MAP kinase (Blot Ab; anti-phosphomapk) (bottom panel). The arrows designate the appropriate protein. Note that x-ephrin B1 is not detectably tyrosine phosphorylated in the presence of activated MAP kinase. (B) Embryos were left uninjected (UN), injected with RNA encoding x-ephrin B1, FGFR1-K562E (KE), or a kinase-dead receptor FGFR1-C289R/K420A (CR/KA) or coinjected with RNA encoding x-ephrin B1 and KE or CR/KA. Lysates were mixed where indicated and immunoprecipitated with anti-FGF receptor antibody (indicated above panels as IP Ab: anti-FGFR). SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis of immune complexes were conducted with the ephrin B1 antibodies (anti-Lerk2 [top panel]) or FGF receptor antibodies (anti-FGFR [bottom panel]). Arrows indicate the corresponding proteins. Note that only kinase active FGFR coprecipitates with x-ephrin B1. (C) Embryos were left uninjected (UN), injected with RNA encoding either x-ephrin B1, KE, or an activated form of FGF receptor 2, FGFR2-C332Y (CY), or coinjected with RNA encoding x-ephrin B1 and KE or CY. Lysates were mixed where indicated and immunoprecipitated with anti-FGF receptor antibody (IP Ab: anti-FGFR). SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis of immunecomplexes was conducted with either antiphosphotyrosine antibodies (top panel) or anti-FGF receptor antibodies (bottom panel). Arrows indicate the appropriate protein. (D) Blastomere cells from injected embryos expressing x-ephrin B1 alone or in combination with the wild-type (WT) and/or kinase-deficient (DN) forms of the FGF receptor were exposed to either FGF or x-EphB2–Fc for 45 min prior to lysis and immunoprecipitation with a polyclonal antibody to the extracellular domain of x-ephrin B1 (IP Ab: anti-x-ephrinB1 [left panel]). Western blots were conducted on immunoprecipitations with antiphosphotyrosine antibodies (Blot Ab: anti-PY [left panel]). The control panels on the right show Western blot analysis of lysates before immunoprecipitations were performed with either FGF receptor-specific antibodies (top right panel) or ephrin B1-specific antibodies (bottom right panel).

To determine if other tyrosine kinases could phosphorylate x-ephrin B1 and regulate its function similarly, x-ephrin B1 was coexpressed in Xenopus embryos with either the Xenopus PDGF receptor tyrosine kinase (3) or a constitutively activated torso receptor tyrosine kinase (64). PDGF receptor activation was subsequently induced by exposing the embryos to PDGF. Both receptors were expressed and activated, as determined by Western blot analysis with antiphosphotyrosine antibody (Fig. 1C, top). Activated torso had no effect on x-ephrin B1, and ligand-activated PDGF receptor only very weakly induced x-ephrin B1 phosphorylation (Fig. 1C, middle) and did not rescue embryonic cell dissociation (data not shown). While Fig. 1C shows no detectable tyrosine phosphorylation of x-ephrin B1 due to the PDGF receptor (Fig. 1C, middle), we have occasionally detected weak phosphorylation. Hence, phosphorylation of x-ephrin B1 occurred specifically in the presence of the activated FGF receptor tyrosine kinase and to a much lesser extent in response to activated PDGF receptor. Interestingly, during gastrulation, when x-ephrin B1 expression increases, FGF, FGF receptor, PDGF receptor, and x-ephrin B1 all localize to the migrating mesoderm of the embryo, providing the possibility of interactions during normal development (2, 3, 31, 34, 37, 66, 67).

The FGF receptor interacts with x-ephrin B1.

Upon activation, the FGF receptor initiates the Ras-Raf-Mek–mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase signaling cascade (44). To test whether MAP kinase activation was required for x-ephrin B1 tyrosine phosphorylation, a constitutively activated form of Mek (27), which activates MAP kinase, was co-expressed with x-ephrin B1 in Xenopus embryos. Embryonic extracts were prepared with two different buffers, one that efficiently solubilizes ephrin (buffer A) (Fig. 2A, middle) and another that maximizes extraction of MAP kinase (buffer B) (Fig. 2A, bottom). Activation of MAP kinase did not alter the phosphorylation state or rescue the cell adhesion effects of x-ephrin B1 (Fig. 2A, top, and, data not shown), implying that an upstream event or alternate FGF receptor-mediated pathway is necessary for ephrin phosphorylation.

We next addressed whether an interaction between x-ephrin B1 and the FGF receptor could be detected. Lysates from embryos coexpressing x-ephrin B1 and the activated FGF receptor were immunoprecipitated with an FGF receptor-specific antibody (77) under stringent detergent conditions (Fig. 2B). x-Ephrin B1 did coimmunoprecipitate with KE, indicating that these proteins existed in a stable complex. This interaction did not occur when lysates containing either protein were mixed, demonstrating that x-ephrin B1 did not nonspecifically associate with the anti-FGF receptor antibody. x-Ephrin B1 did not coimmunoprecipitate with a kinase-deficient FGF receptor mutant [FGFR1-C289R/K420A (CR/KA)], containing a point mutation in its kinase domain (53) (Fig. 2B). A constitutively activated form of another FGF receptor family member, FGFR2-C332Y (CY) (53), also stably associated with tyrosine-phosphorylated x-ephrin B1 (Fig. 2C). x-Ephrin B1 associated with FGF receptors only when the receptors were in an activated state. Furthermore, when x-ephrin B1 was associated with either activated FGF receptor, it was found to be tyrosine phosphorylated (Fig. 2C), and immunoprecipitated FGF receptor can phosphorylate a GST-ephrin B1 cytoplasmic domain fusion protein in vitro (data not shown). These data suggest the possibility that ephrin B1 is a direct receptor substrate, but they do not preclude an indirect mechanism.

It had been previously reported that ephrin B molecules become phosphorylated in fibroblasts upon exposure to soluble, multimeric forms of Eph B-type receptors (33). Therefore, we sought to determine whether FGF and Eph receptors induced the phosphorylation of x-ephrin B1 through the same or alternative pathways. We used the Xenopus embryo expression system to assess whether the FGF receptor mediated one or both phosphorylation events. x-EphB1–Fc, a chimeric protein composed of the extracellular domain of the Xenopus EphB1 receptor (36) fused to the Fc domain of human IgG, was generated and preclustered into multimeric complexes with anti-Fc antibody as previously described (12, 33). Animal cap tissue explants were isolated from blastula stage embryos expressing x-ephrin B1 alone or in combination with the wild-type FGF receptor, a kinase-deficient form of the FGF receptor, or both receptor types. Comparable expression of these proteins was confirmed by Western analysis of lysates (Fig. 2D, right). After explants expressing x-ephrin B1 alone were exposed to x-EphB1–Fc, lysates were made, immunoprecipitated with an anti-ephrin B1-specific antibody, and examined by Western blot analysis (Fig. 2D, left). As observed in fibroblasts, x-ephrin B1 became phosphorylated in response to exogenously added EphB1 receptor. Expression of the kinase-deficient FGFR1 mutant effectively blocked FGF-induced phosphorylation of WT receptor (results not shown) and also blocked FGF-induced phosphorylation of x-ephrin B1 (Fig. 2D, left). However, the mutant did not inhibit the phosphorylation of x-ephrin B1 that was induced by the addition of exogenous x-EphB1–Fc (Fig. 2D, left). Thus, tyrosine phosphorylation of x-ephrin B1 in response to cognate receptor binding or FGF signaling occurs through two independent mechanisms.

The carboxy terminus of x-ephrin B1 interacts with the FGF receptor.

Ephrin B molecules have a high degree of sequence homology in their cytoplasmic domains, particularly within their last 33 amino acids (21). To determine if this region interacted with the FGF receptor, a series of deletion mutations were made within the last 33 residues of x-ephrin B1 (Fig. 3a). Since this region also contained five tyrosine residues that are conserved among ephrin B molecules, the series of deletions generated sequential removal of these residues as well. Each mutant x-ephrin B1 molecule was coexpressed with the activated FGF receptor, and immunoprecipitations were performed with either x-ephrin-specific antibodies (Fig. 3b, top panels) or FGF receptor specific antibodies (bottom panels). When coexpressed with KE, Δ33 was not phosphorylated, and it did not coimmunoprecipitate with KE. While Δ26 showed weakly detectable phosphorylation, it did not associate with KE (data not shown), implying that a region(s) downstream of residue 301 was required for stable interaction. Δ19, Δ15, and Δ6 did coimmunoprecipitate with KE (Fig. 3B, third panel from top) and were phosphorylated (Fig. 3B, first and third panels from top), indicating that a region within residues 302 to 308 was important for interacting with the FGF receptor. Full-length ephrin proteins containing a mutation at either position 305 or 310 (tyrosine changed to phenylalanine) also coimmunoprecipitated with KE, and cell dissociation was rescued (data not shown) (62% and 65% respectively [Fig. 3d]). However, when both residues 305 and 310 were mutated simultaneously (WTY305FY310F), association with KE was markedly reduced (Fig. 3c, top left panel) and cell dissociation was not effectively rescued (15%; Fig. 3d). Moreover, mutation of position 305 in the context of the Δ19 truncation mutant (Δ19Y305F), which lacks residue 310, also resulted in a reduced interaction with the FGF receptor (Fig. 3b, third panel from top). These results demonstrate that both tyrosine residues contained in the region from residues 302 to 310 are critical for stable FGF receptor interaction. Although Δ26, Δ19Y305F, and WTY305FY310F did not coimmunoprecipitate with the FGF receptor, all three mutants were phosphorylated. These results suggest that when overexpressed in cells, these mutants may transiently or weakly associate with overexpressed KE protein but cannot remain stably associated with the receptor without the presence of the region from residues 302 to 310 or without the presence of both tyrosine residues 305 and 310.

Deletion analysis of the x-ephrin B1 cytoplasmic domain defined a specific region within the conserved carboxy-terminal 33 amino acids that is required for FGF receptor interaction. Although phosphorylation site-mapping studies are still required to determine whether the tyrosines at positions 305 and 310 are indeed phosphorylated in vivo, our point mutation data have determined that their presence is required for this association. Collectively, these data indicate an important role for residues 305 and 310 for the stable interaction with the FGF receptor and further suggest that FGF receptor-induced rescue of cell dissociation results from an interaction with ephrin B1 and not downstream signaling events.

FGF induces ephrin B1 phosphorylation in the chicken retina.

Both the FGF and Eph receptor tyrosine kinase families and their ligands have been implicated in similar instructional developmental processes such as axon outgrowth and guidance. For example, during development of the vertebrate visual system, both receptor family members and ephrins regulate retinal axon pathfinding (49, 56, 70). In the developing vertebrate retina, inhibition of the FGF receptor impairs proper neurite outgrowth (50). In addition, Eph receptors and ephrins establish gradients along specific axes that later define the topographical map which migrating axons follow (18). This has been extensively studied in the chicken retina where ephrin B molecules act as repulsive cues to migrating axons which express EphB receptors (8, 17, 52, 63).

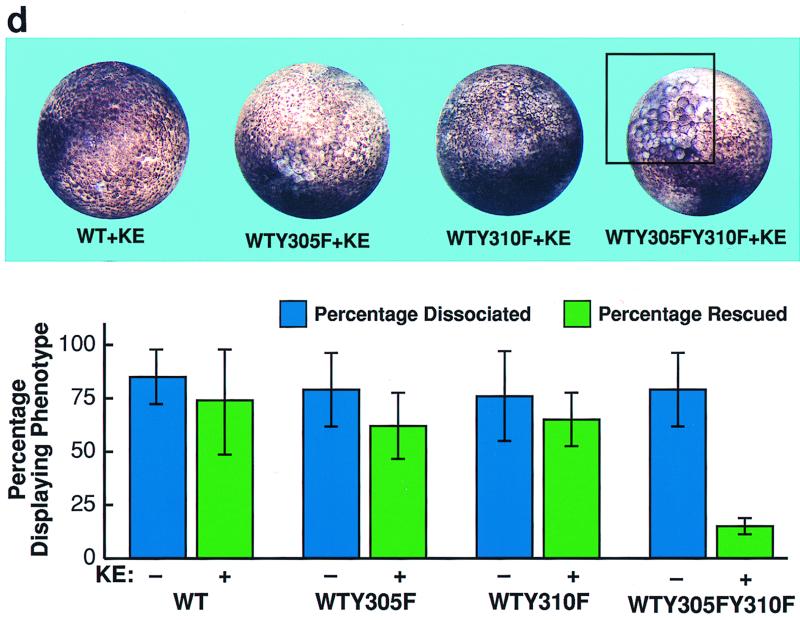

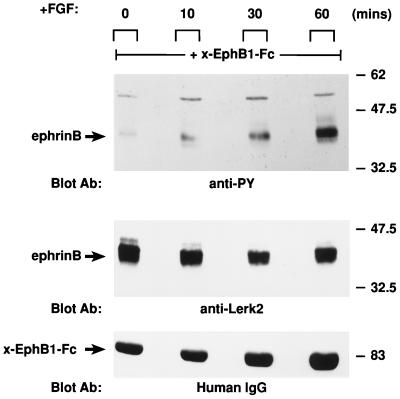

We next examined whether FGF signaling induces the phosphorylation of endogenous ephrins present in neural tissue. Embryonic chicken retina was incubated with FGF for increasing times (Fig. 4). Ephrin B molecules were then extracted from retinal lysates with x-EphB1–Fc as a precipitating agent and analyzed by Western blotting. Phosphorylation of endogenous ephrin B molecules in the retina occurred within 10 min of FGF treatment and increased sixfold over a 1-h period. Hence, our observations in the Xenopus embryo expression system were repeated in a relevant neural tissue, where both proteins are normally expressed and implicated in regulating adhesion.

FIG. 4.

FGF stimulates tyrosine phosphorylation of ephrin molecules in retinal neurons. Embryonic chicken retina was incubated with basic FGF (250 ng/ml) at 37°C for increasing times. Lysates were made and incubated with x-EphB1–Fc (2 μg) for 4 h followed by protein A-Sepharose for 1 h at 4°C. The proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and Western blot analyses were conducted with antiphosphotyrosine antibodies (Blot Ab: anti-PY [top panel]), antiephrin antibodies (anti-Lerk2 [middle panel]), or human IgG antibodies (Blot Ab: Human IgG [bottom panel]). Anti-human IgG was used to detect the x-EphB1–Fc protein. The level of Tyrosine-phosphorylated ephrin increased sixfold over the indicated time course, as determined by scanning densitometry of the autoradiograph.

DISCUSSION

Transmembrane (B-type) ephrins have been implicated in bidirectional signaling upon contact with cognate receptor-expressing cells or reverse signaling through phosphorylation of its cytoplasmic domain. Our results identify the FGF receptor as a molecule that can associate with and induce tyrosine phosphorylation of the ephrin B1 ligand, thus modulating its effect on cell adhesion when ectopically expressed in pluripotent ectodermal cells. Additional support for the importance of the association between FGFR and ephrin B1 comes from experiments with the Y305FY310F double mutant. When expressed in embryos, this mutant ephrin B1 causes cell dissociation but demonstrates a marked reduction in the ability to associate with the FGFR and fails to be effectively rescued by FGFR activity (Fig. 3c and d). These data also indicate that the rescue of cell adhesion is not the result of a general cellular process or a downstream signaling event that results from activation of the FGF receptor pathway. It is also worth noting that while the cytoplasmic domain residues 305 and 310 are important for the ephrin-FGF receptor association, they are not the only required residues. An x-ephrin B1 mutant lacking the entire extracellular domain (38) is also unable to interact with the FGF receptor (data not shown). Therefore, it is likely that regions in both the intracellular and extracellular domains mediate ephrin B1-FGF receptor interaction.

We also show that in neural tissue (chicken retina), FGF treatment results in the phosphorylation of the resident ephrin B protein (Fig. 4), providing supportive evidence for an interaction between the endogenous proteins. In Xenopus, the association between ectopically expressed FGF receptor and ephrin B1 is stable even under stringent conditions (Fig. 2B), but it is not clear whether the association between these two molecules is direct or requires another protein. A complex between the active FGF receptor and ephrin B1 is observed in extracts from embryos coexpressing the two proteins but is not detected in a mixture of two extracts, each expressing only one of the molecules (Fig. 2B), suggesting that another protein may be required for complex formation. It is also possible that while the interaction between the activated FGF receptor correlates with x-ephrin B phosphorylation, tyrosine phosphorylation occurs through an indirect mechanism requiring another kinase.

Both Eph and FGF RTK families and their activating ligands coordinate cell adhesion and migration during development (14, 16, 54, 78). While FGF signaling has been implicated in regulating the cell fate and differentiation of neuronal precursors, a role in controlling the migratory pathway of mesodermal and neuronal precursors has also emerged (16, 54, 76). FGF has also been implicated in modulating cell-adhesive interactions between neuroepithelial cells and the extracellular matrix during neural-tube development (40). The role of FGF in migration events is not limited to vertebrates. In Drosophila, FGF signaling controls morphogenetic movements occurring during gastrulation, neurogenesis, and trachea formation (26, 41). Similarly, ephrins and their receptors also play a role in morphogenetic events during development. Ephrins control the migration of neural crest cells in the branchial arches and somites (29, 43, 62, 71). EphA4 and ephrin B2 functions are necessary for the proper formation of somites (19) and the restriction of cell intermingling (51). Mutations in the Caenorhabditis elegans Vab-1 Eph receptor disrupt epidermal morphogenesis (25). Losses of both cell adhesion and blastocoel formation result from the expression of the activated Eph receptor tyrosine kinase, Pag (x-EphA4) in Xenopus embryos (74). Our findings raise the possibility that cross talk between the FGF receptor and ephrins allows further regulation of cell adhesion events.

Recent work has demonstrated an additional role for ephrins in vasculogenesis (55), where clustered ephrin B1 promoted cell adhesion and capillary-like assembly in cognate receptor-bearing endothelial cells in vitro (65). In another study, ephrin B2-deficient mice had defects in angiogenesis (72). Ephrin B1, like angiopoietins, can also induce sprouting in an in vitro capillary assay, while a GST-Tie2 receptor fusion can phosphorylate the cytoplasmic domain of ephrin B1 in vitro. Thus, it has been suggested that cross talk may exist between signaling pathways triggered by angiogenic factors and ephrin B proteins (1). In this regard, it is interesting that FGFs exhibit strong angiogenic activities in vivo and that FGF signaling is thought to play an important role in the normal development of the vascular system (35, 73). While we observed little detectable phosphorylation of ephrin B1 in response to PDGF in our system (Fig. 1C), the strong phosphorylation of ephrin B1 (Lerk2) in NIH 3T3 cells treated with PDGF (6) is also suggestive of a cross talk scheme. Future analysis of a potential ephrin B1-PDGF receptor interaction will provide further insight into the complex nature of ephrin signaling within different cellular contexts.

It is intriguing that ephrin Bs may play a role in cell adhesion and movement in several cell contexts (endothelial, neural crest, axon guidance, etc.), and that these proteins may be regulated by a number of different receptors in the developing embryo. Although the mechanism of how x-ephrin B1 influences cell adhesion is unclear, its association with and phosphorylation induced by the FGF receptor family affect this event. Phosphorylation may facilitate the interaction with SH2 domain-containing proteins and/or affect ephrin binding to cognate Eph receptors. The carboxyl-terminal PDZ domain of ephrin B1 has recently been shown to bind syntenin, a protein proposed to function as an adapter that couples syndecans to cytoskeletal proteins or cytosolic downstream signal effectors (28, 48). However, this binding may be reduced when the PDZ domain is tyrosine phosphorylated (48). Elucidation of other associated proteins and how they may be organized and interact within a signaling complex is under way. Interestingly, both FGF and Eph receptors functionally interact with L1, another protein involved in cell adhesion (15, 59, 79). Extensive studies have explicitly demonstrated that the FGF receptor is necessary for neurite outgrowth stimulated by the cell adhesion molecules L1, N-cadherin, and NCAM (15, 59). Our data suggest the possibility of an even broader scheme for FGF receptor-related regulation of cell adhesion.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Renping Zhou and Deborah Morrison for critical reading of the manuscript, Deborah Morrison for activated torso cDNA and antibodies, Pantelis Tsoulfas for pCMV-Ig, Marc Mercola for X-PDGF receptor cDNA and antibodies, Yukiko Gotoh for activated Mek cDNA, and Malcolm Whitman for SP64Ten vector. We also appreciate the technical assistance of Kathleen Mood.

This work was supported by an NIH-NRSA grant to L.D.C. and an NIH DE 13248 grant to R.F. This project has been funded in whole or in part with funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract NO1-CO-5600.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams R H, Wilkinson G A, Weiss C, Diella F, Gale N W, Deutsch U, Risau W, Klein R. Roles of ephrinB ligands and EphB receptors in cardiovascular development: demarcation of arterial/venous domains, vascular morphogenesis, and sprouting angiogenesis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:295–306. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amaya E, Stern P A, Musci T J, Kirschner M W. FGF signalling in the early specification of mesoderm in Xenopus. Development. 1993;118:477–487. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ataliotis K, Symes M, Chou M, Ho L, Mercola M. PDGF signalling is required for gastrulation of Xenopus laevis. Development. 1995;121:3099–3110. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.9.3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Becker N, Seitanidou T, Murphy P, Mattei M-G, Topilko P, Nieto M, Wilkinson D G, Charnay P, Gilardi-Hebenstreit P. Several receptor tyrosine kinase genes of the Eph family are segmentally expressed in the developing hindbrain. Mech Dev. 1994;47:3–17. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(94)90091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergemann A D, Cheng H-J, Brambilla R, Klein R, Flanagan J G. Elf-2, a new member of the Eph ligand family, is segmentally expressed in the region of the hindbrain and newly formed somites. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4921–4929. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.9.4921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruckner K, Pasquale E B, Klein R. Tyrosine phosphorylation of transmembrane ligands for Eph receptors. Science. 1997;275:1640–1643. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5306.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castellani V, Yue Y, Zhou R, Bolz J. Dual action of a ligand for the Eph receptor tyrosine kinases on specific populations of axons during development of cortical circuits. J Neurosci. 1998;18:4663–4672. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-12-04663.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng H-J, Nakamoto M, Bergemann A D, Flanagan J G. Complementary gradients in expression and binding of Elf1 and Mek4 in development of the topographic retinotectal projection map. Cell. 1995;82:371–381. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiba A, Keshishian H. Neuronal pathfinding and recognition: roles of cell adhesion molecules. Dev Biol. 1996;180:424–432. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cook G, Tannahill D, Keynes R. Axon guidance to and from choice points. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1998;8:64–72. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(98)80009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Culotti J G, Merz D C. DCC and netrins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:609–613. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis S, Gale N W, Aldrich T H, Masonpierre P C, Lhotak V, Pawson T, Goldfarb M, Yancopoulos G D. Ligands for EPH-related tyrosine kinases that require membrane attachment or clustering for activity. Science. 1994;266:816–819. doi: 10.1126/science.7973638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Desai C J, Gindhart J G, Goldstein L S, Zinn K. Receptor tyrosine phosphatases are required for motor axon guidance in the Drosphila embryo. Cell. 1996;84:599–609. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devore D L, Horvitz H R, Stern M J. An FGF receptor signaling pathway is required for the normal cell migrations of the sex myoblasts in C. elegans hermaphrodites. Cell. 1995;83:611–620. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90101-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doherty P, Walsh F S. CAM-FGF receptor interactions: a model for axonal growth. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1996;8:99–111. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1996.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dono R, Texido G, Dussel R, Ehmke H, Zoller R. Impaired cerebral cortex development and blood pressure regulation in FGF-2 deficient mice. EMBO J. 1998;17:4213–4225. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.15.4213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drescher U, Kremoser C, Handwerker C, Loschinger J, Noda M, Bonehoeffer F. In vitro guidance of retinal ganglion cell axons by RAGS, a 25 kDa tectal protein related to ligands for Eph receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell. 1995;82:359–370. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90425-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drescher U. The Eph family in the patterning of neural development. Curr Biol. 1997;7:799–807. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00409-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Durbin L, Brennan C, Shiomi K, Cooke J, Barrios A, Shamugalingam S, Guthrie B, Lindberg R, Holder N. Eph signaling is required for segmentation and differentiation of the somites. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3096–3109. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.19.3096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fagotto F, Gumbiner B M. Cell contact-dependent signaling. Dev Biol. 1996;180:445–454. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gale N W, Holland S J, Valenzuela D M, Flenniken A, Pan L, Ryan T E, Henkemeyer M, Strebhardt K, Hirai H, Wilkinson D G, et al. Eph receptors and ligands comprise two major specificity subclasses, and are reciprocally compartmentalized during embryogenesis. Neuron. 1996;17:9–19. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80276-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gale N W, Yancopoulas G D. Ephrins and their receptors: a repulsive topic? Cell Tissue Res. 1997;290:227–242. doi: 10.1007/s004410050927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ganju P, Shigemoto K, Brennan L, Entwistle A, Reith A D. The Eck receptor tyrosine kinase is implicated in pattern formation during gastrulation, hindbrain segmentation and limb development. Oncogene. 1994;9:1613–1624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao P-P, Zhang J H, Yokoyama M, Racey B, Dreyfus C F, Black I B, Zhou R. Regulation of topographic projection in the brain: Elf-1 in the hippocamposeptal system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11161–11166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.11161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.George S E, Simokat K, Hardin J, Chisholm A D. The Vab-1 eph receptor tyrosine kinase functions in neural and epithelial morphogenesis in C. elegans. Cell. 1998;92:633–643. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81131-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gisselbrecht S, Sheath J B, Doe C Q, Michelson A M. Heartless, encodes a fibroblast growth factor receptor (DFR1/DFGF-R2) involved in the directional migration of early mesodermal cells in the Drosophila embryo. Genes Dev. 1996;10:3003–3017. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.23.3003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gotoh Y, Matsuda S, Tanaka K, Hattori S, Iwamatsu A, Ishikawa M, Kosako H, Nishida E. Characterization of recombinant Xenopus MAP linase kinases mutated at potential phosphorylation sites. Oncogene. 1994;9:1891–1898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grootjans J J, Zimmerman P, Reekmans G, Smets A, Degeest G, Durr J, David G. Syntenin, a PDZ protein that binds syndecan cytoplasmic domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:13683–13688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Helbling P M, Tran C T, Brandli A W. Requirement for EphA4 receptor signaling in the segregation of xenopus third and fourth arch neural crest. cells. Mech Dev. 1998;78:63–79. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henkemeyer M, Orioli D, Henderson J T, Saxton T M, Roder J, Pawson T, Klein R. Nuk controls pathfinding of commissural axons in the mammalian central nervous system. Cell. 1996;86:35–46. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80075-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ho L, Symes K, Yordan C, Gudas L J, Mercola M. Localization of the PDGF A and PDGFR alpha mRNA in Xenopus embryos suggests signalling from the neural ectoderm and pharyngeal endoderm to neural crest cells. Mech Dev. 1994;48:165–174. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(94)90057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holash J A, Soans C, Chong L D, Shao H, Dixit V M, Pasquale E B. Reciprocal expression of the Eph receptor Cek5 and its ligand(s) in early retina. Dev Biol. 1997;182:256–269. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.8496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holland S J, Gale N W, Mbamalu G, Yancopoulos G D, Henkemeyer M, Pawson T. Bidirectional signaling through the EPH-family receptor Nuk and its transmembrane ligands. Nature. 1996;383:722–725. doi: 10.1038/383722a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Issacs H V, Tannahill D, Slack J M W. Expression of a novel FGF in the Xenopus embryo. A new candidate inducing factor for mesoderm formation and anteroposterior specification. Development. 1992;114:711–720. doi: 10.1242/dev.114.3.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson D E, Williams L T. Functional and structural diversity in the FGF receptor multigene family. Adv Cancer Res. 1993;60:1–41. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60821-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones T, Karavanova I, Maéno M, Ong R, Kung H-F, Daar I O. An amphibian homologue of the eph family of receptor tyrosine kinases is developmentally regulated. Oncogene. 1995;10:1111–1117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones T L, Karavanova I, Chong L D, Zhou R, Daar I O. Identification of XLerk, an Eph family ligand regulated during mesoderm induction and neurogenesis in Xenopus laevis. Oncogene. 1997;14:2159–2166. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones T L, Chong L D, Kim J, Xu R-H, Kung H-F, Daar I O. Loss of cell adhesion in Xenopus laevis embryos mediated by the cytoplasmic domain of XLerk, an Eph ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:576–581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.2.576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kimelman D, Kirschner M W. Synergistic induction of mesoderm by FGF and TGF-beta and the identification of an mRNA coding for FGF in the early Xenopus embryo. Cell. 1987;51:869–877. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90110-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kinoshita Y, Kinoshita C, Heuer J G, Bothwell M. Basic fibroblast growth factor promotes adhesive interactions of neuroepithelial cells from chick neural tube with extracellular matrix proteins in culture. Development. 1993;119:943–956. doi: 10.1242/dev.119.3.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klambt C, Glazer L, Shilo B Z. Breathless, a Drosophila FGF receptor homologue, is essential for migration of tracheal and specific midline glial cells. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1668–1678. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.9.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krueger N X, Van Vactor D, Wan H I, Gelbart W M, Goodman C S, Saito H. The transmembrane tyrosine phosphatase DLAR controls motor axons guidance in Drosophila. Cell. 1996;84:611–622. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krull C E, Lansford R, Gale N W, Collazo A, Marcelle C, Yancopoulos G D, Fraser S E, Bronner-Fraser M. Interactions of Eph-related receptors and ligands confer rostrocaudal pattern to trunk neural crest migration. Curr Biol. 1997;7:571–580. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00256-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.LaBonne C, Whitman M. Localization of MAP kinase in early Xenopus embryos: implications for endogenous FGF signalling. Dev Biol. 1997;183:9–20. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.8497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Labrador J P, Brambilla R, Klein R. The N-terminal globular domain of Eph receptors is sufficient for ligand binding and receptor signaling. EMBO J. 1997;16:3889–3897. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.3889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lackmann M, Oates A C, Dottori M, Smith F M, Do C, Power M, Kravets L, Boyd A W. Distinct subdomains of the EphA3 receptor mediate ligand binding and receptor dimerization. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:20228–20237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Letourneau P C, Snow D M, Gomez T M. Regulation of growth cone motility by substratum bound molecules and cytoplasmic [Ca2+] Prog Brain Res. 1994;103:85–98. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)61129-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin D, Gish G D, Songyang Z, Pawson T. The carboxyl terminus of B class ephrins constitutes a PDZ domain binding motif. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:3726–3733. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McFarlane S, Holt C E. Growth factors and neural connectivity. Genet Eng. 1996;18:33–47. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1766-9_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McFarlane S, Cornel E, Amaya E, Holt C E. Inhibition of FGF receptor activity in retinal ganglion cell axons causes errors in target recognition. Neuron. 1996;17:245–254. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mellitzer G, Xu Q, Wilkinson D G. Eph receptors and ephrins restrict cell intermingling and communication. Nature. 1999;400:77–81. doi: 10.1038/21907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakamoto M, Cheng H J, Friedman G C, McLaughlin T, Hansen M J, Yoon C H, O'Leary D D, Flanagan J G. Topographically specific effects of ELF-1 on retinal axon guidance in vitro and retinal axon mapping in vivo. Cell. 1996;86:755–766. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80150-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nielson K M, Friesel R. Ligand-independent activation of fibroblast growth factor receptors by point mutations in the extracellular, transmembrane, and kinase domains. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:25049–25057. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.25049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Osterhout D J, Ebner S, Xu J, Ornitz D M, Zazanis G A, McKinnon R D. Transplanted oligodendrocyte progenitor cells expressing a dominant-negative FGF receptor transgene fail to migrate in vivo. J Neurosci. 1997;17:9122–9132. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-23-09122.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pandey A, Shao H, Marks R M, Polverini P J, Dixit V M. Role of B61, the ligand for the Eck receptor tyrosine kinase, in TNF-alpha induced angiogenesis. Science. 1995;268:567–569. doi: 10.1126/science.7536959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pasquale E B. The Eph family of receptors. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:608–615. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80113-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pini A. Axon guidance. Growth cones say no. Curr Biol. 1994;4:131–133. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(94)00029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rutishauser U. Adhesion molecules of the nervous system. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1993;3:709–715. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(93)90142-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saffell J L, Williams E J, Mason I, Walsh F S, Doherty P. Expression of a dominant negative FGF receptor inhibits axonal growth and FGF receptor phosphorylation stimulated by CAMS. Neuron. 1997;18:231–242. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80264-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sefton M, Nieto M A. Multiple roles of Eph-like kinases and their ligands during development. Cell Tissue Res. 1997;290:243–250. doi: 10.1007/s004410050928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Slack J M W, Darlington B G, Heath J K, Godsave S F. Mesoderm induction in early Xenopus embryos by heparin-binding growth factors. Nature. 1987;326:197–200. doi: 10.1038/326197a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smith A, Robinson V, Patel K, Wilkinson D G. The EphA4 and EphB1 receptor tyrosine kinases and ephrinB2 ligand regulate targeted migration of branchial neural crest cells. Curr Biol. 1997;7:561–570. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Soans C, Holash J A, Pasquale E B. Characterization of the expression of the Cek8 receptor-type tyrosine kinase during development and in tumor cell lines. Oncogene. 1994;9:3353–3361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sprenger F, Trosclar M M, Morrison D K. Biochemical analysis of Torso and D-raf during Drosophila embryogenesis: implications for terminal signal transduction. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:1163–1172. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.2.1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stein E, Lane A A, Ceretti D P, Schoecklmann H O, Schroff A D, Van Etten R L, Daniel T O. Eph receptors discriminate specific ligand oligomers to determine alternative signaling complexes, attachment, and assembly responses. Genes Dev. 1998;12:667–678. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.5.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tanaka M, Wang D-Y, Kamo T, Igarashi H, Wang Y, Xiang Y-Y, Tanioka F, Naito Y, Sugimura H. Interaction of EphB2-tyrosine kinase receptor and its ligand conveys dorsalization signal in Xenopus laevis development. Oncogene. 1998;17:1509–1516. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tannahill D, Isaacs H V, Close M J, Peters G, Slack J M W. Developmental expression of the Xenopus int-2 (FGF-3) gene: activation by mesodermal and neural induction. Development. 1992;115:695–702. doi: 10.1242/dev.115.3.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tessier-Lavigne M, Goodman C S. The molecular biology of axon guidance. Science. 1996;274:1123–1133. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Van Vactor D. Adhesion and signaling in axonal fasciculation. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1998;8:80–86. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(98)80011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Viollet C, Doherty P. CAMs and the FGF receptor: an interacting role in axonal growth. Cell Tissue Res. 1997;290:451–455. doi: 10.1007/s004410050952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang H U, Anderson D J. Eph family transmembrane ligands can mediate repulsive guidance of trunk neural crest migration and motor axon outgrowth. Neuron. 1997;18:383–396. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81240-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang H U, Chen Z-F, Anderson D J. Molecular distinction and angiogenic interaction between embryonic arteries and veins revealed by ephrinB2 and its receptor EphB4. Cell. 1998;93:741–753. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81436-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wilkie A O, Morriss-Kay G M, Jones E Y, Heath J K. Functions of fibroblast growth factors and their receptors. Curr Biol. 1995;5:500–507. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Winning R S, Scales J B, Sargent T D. Disruption of cell adhesion in Xenopus embryos by Pagliaccio, and Eph-class receptor tyrosine kinase. Dev Biol. 1996;179:309–319. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xu Q, Alldus G, Holder N, Wilkinson D G. Expression of truncated Sek-1 receptor tyrosine kinase disrupts the segmental restriction of gene expression in the Xenopus and zebrafish hindbrain. Development. 1995;121:4005–4016. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.12.4005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yamaguchi T P, Harpal K, Henkemeyer M, Rossant J. FGFr-1 is required for embryonic growth and mesodermal patterning during mouse gastrulation. Genes Dev. 1994;8:3032–3044. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.24.3032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhan X, Plourde C, Hu X, Friesel R, Maciag T. Association of fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 with c-src correlates with association between c-src and cortactin. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:20221–20224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhou R. The Eph family receptors and ligands. Pharmacol Ther. 1998;77:151–181. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(97)00112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zisch A H, Stallcup W B, Chong L D, Dahlin-Huppe K, Voshol J, Schachner M, Pasquale E B. Tyrosine phosphorylation of L1 family adhesion molecules: implication of the Eph kinase Cek5. J Neurosci Res. 1997;47:655–665. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4547(19970315)47:6<655::aid-jnr12>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zisch A H, Pasquale E B. The Eph family: a multitude of receptors that mediate cell recognition signals. Cell Tissue Res. 1997;290:217–226. doi: 10.1007/s004410050926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]