Abstract

The present study looks at how exposure to Instagram #fitspiration images affects self‐rated sexual attractiveness among women. An experimental pre‐test/post‐test control group design was implemented. Four hundred and forty‐two female undergraduate students (mean age of 22.06 ± 2.15 years) were randomly exposed to either fitspiration (N = 233) or travel Instagram images (N = 209). Well known self‐report measures of Instagram use, body satisfaction, and self‐perceived sexual attractiveness were completed. The results showed that viewing fitspiration models on Instagram was more likely to lower self‐perceived sexual attractiveness among women than travel images. This effect was mediated by body satisfaction. The present findings built upon previous research that focuses on the detrimental effects of exposure to appearance‐focused Instagram profile images on body image satisfaction by showing that exposure to Instagram fitspiration might also influence women perceived sexual attractiveness. Negative consequences of social media exposure on women’s sexual well‐being need to be further investigated.

Keywords: Body image, fitspiration, Instagram, sexual attractiveness, social media use

INTRODUCTION

The relationship between exposure to idealized bodies and body dissatisfaction among women has been widely discussed in traditional forms of media, most notably fashion magazines and television (Levine & Murnen, 2009). Unrealistic pictures of women’s bodies in the media have been held responsible for women’s “normative discontent” about their bodies (Grabe, Ward & Hyde, 2008), as increased media exposure to the thin ideal can elicit body dissatisfaction among women (Grabe et al., 2008; Groesz, Levine & Murnen, 2002). Meta‐analytic reviews confirmed that exposure to mass media portraying the thin‐ideal body is associated to body image uneasiness among women (Grabe et al., 2008).

Internet‐based media – particularly social network sites (SNSs) – have grown more and more popular in recent years. For this reason, innovative research has emerged that seeks to address the influence of SNSs on body image. Systematic reviews and meta‐analyses on this topic (Fardouly & Vartanian, 2016; Holland & Tiggemann, 2016; Saiphoo & Vahedi, 2019) concluded that the use of SNSs is associated with body image concerns and disordered eating behavior. Viewing and uploading photos were recognized as particularly problematic factors responsible for body dissatisfaction.

Instagram is a social networking site that focuses primarily on sharing photos and videos. It has approximately 500 million daily active users, many of which are young adults. Since Instagram allows users to carefully select the personal photos they wish to share, and enhance them with filtering and editing tools, a growing body of research has focused on the impact of Instagram use on body image. In fact, most photos posted on Instagram can be edited and filtered to attain the desired results (Hendrickse, Arpan & Clayton, 2017). This implies that Instagram users are not only more likely to promote an ideal self but are also more likely to be exposed to the ideal selves of others. This, in turn, might enhance the perceived discrepancy between one’s evaluation of his or her own appearance and the proposed aesthetic ideal (i.e., body dissatisfaction; see Cash & Szymanski, 1995).

Recent experimental studies that examine the effects of appearance‐focused Instagram profile images confirmed that Instagram use has a negative impact on body satisfaction among women (Brown & Tiggemann, 2016; Casale, Gemelli, Calosi, Giangrasso & Fioravanti, 2019; Kleemans, Daalmans, Carbaat & Anschütz, 2018; Sherlock & Wagstaff, 2018; Slater, Varsani & Diedrichs, 2017; Tiggemann & Barbato, 2018; Tiggemann, Hayden, Brown & Veldhuis, 2018; Tiggemann & Zaccardo, 2015).

It has been shown that exposure to images of celebrities, attractive peers, and thin people produced greater body dissatisfaction than exposure to travel images or images promoting average‐sized people (Brown & Tiggemann, 2016; Casale et al., 2019; Tiggemann et al., 2018) In keeping with these results, it has also been shown that being exposed to appearance comments on Instagram contributed to greater body dissatisfaction than being exposed to place‐related comments (Tiggemann & Barbato, 2018), and exposure to manipulated Instagram selfies leads to lower body satisfaction than exposure to non‐manipulated selfies (Kleemans et al. (2018). Overall, these results suggest that Instagram is a concerning platform when it comes to body image, since it focuses on sharing photos and allows for easy editing and manipulation of these images.

#Fitspiration and body satisfaction

Beyond the thin ideal, women are exposed to a broader range of body‐ideal messages. Whereas fitness and muscularity have long been encouraged for men (Pope, Phillips & Olivardia, 2000), a new trend that emphasized women’s bodies being athletic and toned has recently emerged (Gruber, 2007). “Fitspiration” promotes this athletic ideal. This term is referred to images and words posted on social media in order to inspire people to engage in physical activity and achieve a toned, muscular body (Boepple & Thompson, 2016). Although fitspiration has been initially proposed as a healthy solution to the trend of “thinspiration”– which glorifies thinness and encourages unhealthy eating behaviors (Slater et al., 2017) – recent content analyses have revealed that fitspiration, like thinspiration, promotes a tall, slim, toned and perfectly well‐proportioned body shape, often containing messages that induce guilt and restrictive eating (e.g., Boepple & Thompson, 2016; Tiggemann & Zaccardo, 2016). Traditionally thin bodies continue to be emphasized in fitspiration images, in addition to the newer aspects of fitness and modest muscularity (Tiggemann & Zaccardo, 2015). Unfortunately, this body type is probably just as unattainable for most women as the older, thinner ideal. Indeed, it seems that fitspiration communicates messages that are potentially harmful to women’s body image (Griffiths & Stefanovski, 2019; Uhlmann, Donovan, Zimmer‐Gembeck, Bell & Ramme, 2018). Robinson, Prichard, Nikolaidis, Drummond, Drummond and Tiggemann (2017) showed that although fitness‐idealized images aimed to inspire positive body image and motive women to a “healthy lifestyle,” exposure to fitness imagery does not have an effect on actual exercise engagement and increases body dissatisfaction. Recent experimental studies have found that young women who are exposed to fitspiration images encounter greater negative mood and body dissatisfaction levels, and lower appearance‐related self‐esteem and self‐rated attractiveness levels, than women who are exposed to appearance‐neutral control images, like travel or interior design images (Sherlock & Wagstaff, 2018; Slater et al., 2017; Tiggemann & Zaccardo, 2015).

Sexual attractiveness

Whereas experimental evidence indicates that both appearance‐focused and fitness‐idealized Instagram images negatively affect body image satisfaction, less is known about the potential effect that such an exposure might have on perceived sexual attractiveness because of the decrement in body satisfaction levels. Howell and Weeks (2017 p. 92) argue that “self‐ratings of attractiveness would understandably be lower if the point of comparison is based upon unrealistic cultural standards” since contemporary women are socialized to believe that an adequate sex partner must conform to societal norms regarding sexual and physical attractiveness (Dove & Wiederman, 2000).,

Sexual attractiveness has been defined as a type of attractiveness (related to but distinct from general or physical attractiveness) that involves being desirable as a sexual partner, the ability or likelihood of arousing sexual desire in others, and the ability to provide sexual pleasure to others (Amos & McCabe, 2015). Focusing the empirical attention on perceived sexual attractiveness might be important for a variety of reasons. First, there are preliminary indications of an association between being concerned about one’s appearance and impaired social functioning. For instance, young women who perceive themselves as physically unattractive have been shown to be more likely to avoid cross‐sex interactions (Mitchell & Orr, 1976), to experience higher levels of social anxiety (Feingold, 1992; Howell & Weeks, 2017), and to engage in less intimate social interactions with members of the same and other sex (Nezlek, 1988). Significant positive associations were also found between perceived sexual attractiveness and happiness among women independently from the average age of the sample (Stokes & Frederick, 2003). It has also been shown that the more a woman perceived herself as less attractive than before, the more likely she was to report a decline in sexual desire or frequency of sexual activity (Koch, Mansfield, Thurau & Carey, 2005) and sexual satisfaction over time (Kvalem, Træen, Markovic & von Soest, 2019; Woertman & van den Brink, 2012), which, in turn is positively associated with life satisfaction (Buczak‐Stec, König & Hajek, 2019). Finally, links between perceived sexual attractiveness and self‐esteem among women have also been reported (Davison & McCabe, 2005).

According to Amos and McCabe (2016), sexual attractiveness perception is predicted by different factors related to both physical (i.e., body esteem) and non‐physical traits (i.e., sexual esteem, sexual experience, and adherence to gender norms). Wade (2000, 2003) found empirical support to this perspective in that he found that women who reported positive feelings toward their own bodies also rated their sexual attractiveness more positively.

Since women who are exposed to fitspiration images encounter greater body dissatisfaction, and body dissatisfaction negatively impact on perceived sexual attractiveness, it is plausible to suppose that exposure to Instagram fitspiration images negatively affect perceived sexual attractiveness through its negative effect on body image satisfaction. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have investigated the direct and indirect (i.e., mediated) effect of Instagram use on self‐rated sexual attractiveness. The present study aims to build up previous research on the effect of social media use on body image‐related variables by filling this gap.

Hypotheses

We hypothesize that viewing #fitspiration images will lead women to perceive themselves as being less sexually attractive (Hypothesis 1) and that this effect will be mediated by body satisfaction (Hypothesis 2).

METHODS

Research design and participants

An experimental pre‐test/post‐test control group design was implemented. Italian female undergraduate students (n = 442) were recruited through advertisements on various SNSs. All of the participants were between 18 and 26 years of age, with a mean age of 22.06 (SD = 2.15), and all of them were Caucasian. Participation was on a voluntary basis, and none of the participants received compensation for taking part in our study. Ethical approval was gained from the Ethics Committee of the University of Florence. Informed consent was obtained from all of the participants.

Procedure

Participants completed the pre‐test, which featured measures of Instagram use, body satisfaction, and self‐perceived sexual attractiveness. They were then randomly assigned to either the experimental or control group. Participants in the experimental group (n = 233) were exposed to ten images of fit models from their own sex (fitspiration condition), whereas participants in the control group (n = 209) were exposed to ten images of landscapes and buildings (travel condition). After viewing all of the Instagram images, the participants completed post‐exposure self‐perceived sexual attractiveness and body satisfaction measures.

Stimulus materials

The #fitspiration image set contained 10 photos of women posing in fitness clothing or engaging in exercise. The travel image set featured 10 photos of various travel destinations, including landscapes and buildings. All images were selected from public Instagram profiles featuring “fitspiration,” “fitmodel,” “fitspo,” and “travel” hashtags. An initial pool of 30 fitspiration images was rated by a small sample of 15 women from the target age. They were asked to comment on the “inspiration to fit quality” of each photo, using a ten‐point Likert scale (from 1 n ot at all to 10 = very much). The most quoted pictures (i.e., one's with the highest ratings) were selected for the final set of #fitspiration images.

Measures

Instagram use

Participants were asked to indicate whether or not they had an Instagram account, how many hours they spend on Instagram in a typical day, and their favorite types of profiles (e.g., celebrities, landscapes, etc.).

Mood and body satisfaction. Following Heinberg and Thompson (1995), visual analogue scales (VASs) were used to measure state mood and body satisfaction before and after viewing the Instagram images. Participants indicate their “right now” mood and body satisfaction on a horizontal line (from 1 = not at all to 10 = a lot). Four mood dimensions (“anxiety,” “depression,” “happiness,” and “anger”) and two body satisfaction dimensions (“weight satisfaction” and “appearance satisfaction”) were used. Higher scores indicate higher body satisfaction. The VASs are valuable because they are quick to complete, difficult to recall, and sensitive to small changes over time. They have also been demonstrated to correlate with more complex measures of body image satisfaction (Heinberg & Thompson, 1995).

Self‐perceived sexual attractiveness

Self‐rated sexual attractiveness was assessed using the Self‐Perceived Sexual Attractiveness Scale (SPSA; Amos & McCabe, 2015). The SPSA scale is composed of six statements that are meant assess the extent to which individuals feel sexually attractive. Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they agreed with the statements on a seven‐point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = neither agree nor disagree, 7 = strongly agree). A sample item is “I believe I can attract sexual partners.” Responses across items were averaged so that higher scores indicate higher self‐perceptions of sexual attractiveness. The scale was found to demonstrate good internal consistency (α = 0.95) and construct validity (Amos & McCabe, 2015). The Cronbach’s alpha in the current study was α = 0.94 at pre‐test and α = 0.96 at post‐test.

Data analyses

The baseline equivalence of the experimental and control groups was tested using a one‐way ANOVA. We then analyzed the experimental manipulation effect by conducting a Mixed 2 × 2 ANOVA, using Time (pre‐ and post‐test) as a within factor and Group (experimental and control) as a between factor. To examine whether the effect of image type (0 = travel vs 1 = fitspiration) on self‐perceived sexual attractiveness was mediated by decreased weight satisfaction (Mediator 1) and appearance satisfaction (Mediator 2), an ordinary least squares regression‐based path analysis was conducted using PROCESS tool for mediation analysis (Model 4; Hayes, 2012, 2018). Pre‐exposure scores were controlled for in the first step of the analysis.

RESULTS

Preliminary analysis

No significant differences were found with regards to age among female participants in either the experimental or control group [M = 22 (SD = 2.13) and M = 22.11 (SD =2.18), F (1,439) = 0.29, p = 0.59]. The two groups did not differ in either relationship status (27% vs 22.5% with no partner; 69.1% vs 71.8% with occasional partners; and 3.9% vs 5.7% in stable relationships) or the duration of the relationship [M = 2.79 (SD = 2.24) and M = 2.98 (SD = 2.34), F (1,320) = 0.52, p = 0.47].

A significant portion of the sample (87.6%) reported that they have an Instagram account. No significant differences were found between the control and experimental groups in terms of either the time spent on Instagram in a typical day [M = 1.13 (SD = 1.17) and M = 1.21 (SD = 1.26), F (1,385) = 0.38, p = 0.53] or in the number of Instagram users (88.8% vs 86.1% χ2 (1) = 0.74 p = 0.38). Celebrity‐oriented Instagram profiles received the most followers among both the experimental and control group (50.6% vs 51% χ2 (5) = 0.3,51 p = 0.62).

The between‐groups baseline comparisons showed that no significant differences emerged in terms of the initial levels of weight satisfaction (F (1,440) = 1.43, p = 0.23), appearance satisfaction (F (1,440) = 0.01, p = 0.92), and self‐perceived sexual attractiveness (F (1,440) = 1.04, p = 0.31) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Pre ‐ and post‐tests scores on the study variables by experimental condition

| Experimental group | Control group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre‐test M (SD) | Post‐test M (SD) | Pre‐test M (SD) | Post‐test M (SD) | |

| Weight satisfaction | 5.26 (2.64) | 4.91 (2.66) | 4.96 (2.62) | 4.99(2.56) |

| Appearance Satisfaction | 5.10 (2.25) | 4.73 (2.42) | 5.12 (2.22) | 4.99 (2.31) |

| Self‐perceived sexual attractiveness | 4.57 (1.11) | 4.43 (1.25) | 4.46 (1.16) | 4.50 (1.26) |

Effect of #fitspiration images on self‐perceived sexual attractiveness and mediation by body satisfaction

The mixed ANOVA revealed a significant effect of Time × Group on self‐perceived sexual attractiveness (F (1,440) = 11.17, p = 0.001, ηp 2 = 0.02). Women in the experimental group reported significantly lower post‐test self‐perceived sexual attractiveness scores (t 232 = 3.12 p = 0.002, d = 0.13), whereas no significant differences were observed in the control group (t 208 = −1.48 p = 0.14). A significant effect of Time × Group on weight satisfaction and appearance satisfaction was also found (F (1,440) = 13.51, p < 0.001, ηp 2 = 0.03; F (1,440) = 4.46, p = 0.03, ηp 2 = 0.01 respectively). Women in the experimental group reported significantly lower post‐test weight and appearance satisfaction (t 232 = 4.87 p < 0.001, d = 0.13; t 232 = 5.01 p < 0.001, d = 0.16 respectively) whereas no significant differences were found in the control group (t 208 = −0.45 p = 0.65; t 208 = 1.63 p = 0.10 respectively).

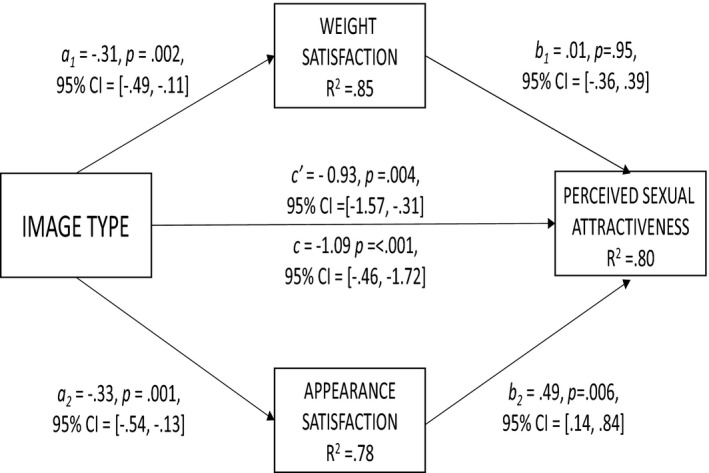

Results from a parallel mediation analysis (Fig. 1) indicated that image type (0 = travel vs 1 = fitspiration) is indirectly related to perceived sexual attractiveness through its relationship with the appearance satisfaction dimension of body satisfaction (a2b = −0.16, 95%CI [−0.42, −0.02]). In contrast the indirect effect through weight satisfaction was not significant (a1b1 = −0.004, 95% CI [−0.17, 0.13]. Moreover, a direct negative effect of image type on perceived sexual attractiveness was also found. The overall model was significant (F (4,437) = 449.41, p < 0.001 R² = 0.80).

Fig. 1.

The mediating effect of weight and appearance satisfaction in the relationship between image type and perceived sexual attractiveness.

DISCUSSION

The aim of the present study was to investigate the association between viewing #fitspiration images and self‐perceived sexual attractiveness among women. A negative effect on perceptions of sexual attractiveness was found. Women exposed to fitspiration images reported lower self‐rated attractiveness compared to women who were exposed to travel images (H1 was supported). Women exposed to fitspiration images also reported lower body satisfaction (i.e., weight and appearance satisfaction). Our findings are consistent with previous studies that have found a relationship between Instagram beauty ideals and body image (Sherlock & Wagstaff, 2018; Slater et al. 2017; Tiggemann & Zaccardo, 2015), while also extending the negative effects of #fitspiration models to the dimension of sexual attractiveness.

Since evidence is emerging on the association between Instagram use and body image (e.g., Tiggemann & Zaccardo, 2015), and since body satisfaction has been widely linked to sexual attractiveness (e.g., Wiederman, 2012), the present study also aimed to investigate whether the effect of Instagram use on self‐rated sexual attractiveness was mediated by decreased body satisfaction. Our findings show that appearance satisfaction dimension of body satisfaction mediated the relationship between Instagram fitspiration images and perceptions of sexual attractiveness among women (H2 was supported). In fact, lower self‐rated sexual attractiveness levels after viewing fitspiration images on Instagram was explained by a body dissatisfaction mechanism, and, in particular, by a decrement in appearance satisfaction. This result confirmed the influence of body satisfaction on self‐reported sexual attractiveness (e.g., Wiederman 2012). However, weight satisfaction – a component of body satisfaction – although negatively influenced by the exposure to fitspiration images on Instagram, was not linked to self‐perceived sexual attractiveness. It is possible to suppose that when judging their ability of being sexually attractive and arousing sexual desire in others, women put more importance on how they appear to others and on how they are satisfied with overall body appearance than considering how much they are satisfied with a specific component of their body, that is their weight.

The present findings have important theoretical and practical implications. First, our results build upon previous research that focuses on the detrimental effects of exposure to appearance‐focused Instagram profile images on body image satisfaction by showing that exposure to Instagram fitspiration might also influence women perceived sexual attractiveness, both directly and indirectly through appearance satisfaction. On the one hand, these findings provide further support to theoretical frameworks such as the sociocultural model (Thompson, Heinberg, Altabe & Tanleff‐Dunn, 1999) which proposes social comparison as a fundamental process by which media negatively impact on body image. On the other hand, in keeping with more recent lines of research (e.g., Tiggemann et al., 2018; Tiggemann & Zaccardo, 2015), our results extend these theoretical frameworks into new media and highlight additional negative outcomes. At a practical level, media literacy programs (interventions promoting knowledge, attitudes, and skills enabling people to understand and critically analyze the nature of mass media and one’s relationship with them; Levine, Piran & Stoddard, 1999) might incorporate fitspiration imagery in order to reduce its negative effect on body image. Generally speaking, prevention programs might focus on the development of self‐protective response to threatening appearance‐related media content (Halliwell, 2015). Regardless, future studies on the relation between viewing fitspiration images and sexual attractiveness should investigate the role of other non‐physical traits (i.e., sexual esteem, sexual experience, and adherence to gender norms) that were found to influence confidence in one’s ability to arousing sexual desire beyond to body image (Amos & McCabe, 2016).

The present study features several limitations. First, the sample was restricted to Italian university students. Although the sample size is quite large, the overall results may not be generalized to different countries and cultures. Future research should investigate the effects on adolescents who frequently use social networking sites and are greatly influenced by prevailing beauty ideals (e.g., Jones, 2001; Meier & Gray, 2014; Salomon & Spears Brown, 2017). Second, this study was carried out in a laboratory setting. Although the images we used were sourced from Instagram, there was no opportunity to “like” them or comment on them, a degree of interactivity that distinguishes social media technologies from conventional mass media (Perloff, 2014). Future research should attempt to provide greater interaction with the proposed images in order to improve the ecological validity of the results. Moreover, pre‐exposure to fitspiration images on Instagram was not measured, which means that results among the control group could be affected by a habituation effect.

Finally, sexual attractiveness perceptions were evaluated immediately following a one‐time exposure to Instagram images, which might limit the internal validity of the study. After all, even if an effect on self‐rated sexual attractiveness was found, the conclusions might not hold up over time. In fact, the effect could increase or decrease over time as a consequence of frequent exposure to Instagram images. In other words, longitudinal studies are needed in order to evaluate the long‐term influence of beauty ideals on sexual attractiveness, and how this effect impacts sexual well‐being. Indeed, some sexual difficulties could be caused by an inability to reach the aesthetically “perfect” standards proposed by social media. In terms of prevention, critical thinking toward social media contents should be promoted among girls and young women, who should be encouraged to evaluate themselves according to criteria that emphasizes competence rather than sexual attractiveness.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Fioravanti, G. , Tonioni, C. & Casale, S. (2021). #Fitspiration on Instagram: The effects of fitness‐related images on women’s self‐perceived sexual attractiveness. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 62, 746–751.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- Amos, N. & McCabe, M. P. (2015). Conceptualizing and measuring perceptions of sexual attractiveness, Are there differences across gender and sexual orientation? Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 111–122. [Google Scholar]

- Amos, N. & McCabe, M. P. (2016). Self‐Perceptions of sexual attractiveness, satisfaction with physical appearance is not of primary importance across gender and sexual orientation. The Journal of Sex Research, 53, 172–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boepple, L. & Thompson, J. K. (2016). A content analytic comparison of fitspiration and thinspiration websites. International Journal of Eating Disorder, 49, 98–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Z. & Tiggemann, M. (2016). Attractive celebrity and peer images on Instagram: Effect on women's mood and body image. Body Image, 19, 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buczak‐Stec, E. , König, H. H. & Hajek, A. (2019). The link between sexual satisfaction and subjective well‐being, a longitudinal perspective based on the German Ageing Survey. Quality of Life Research, 28, 3025–3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casale, S. , Gemelli, G. , Calosi, C. , Giangrasso, B. & Fioravanti, G. (2019). Multiple exposure to appearance‐focused real accounts on Instagram: Effects on body image among both genders. Advance online publication. Current Psychology, 40, 2877–2886.

- Cash, T. F. & Szymanski, M. L. (1995). The development and validation of the body‐image ideals questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment, 64, 466–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison, T. E. & McCabe, M. P. (2005). Relationships between men’s and women’s body image and their psychological, social, and sexual functioning. Sex Roles, 52, 463–475. [Google Scholar]

- Dove, N. L. & Wiederman, M. W. (2000). Cognitive distraction and women’s sexual functioning. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 26, 67–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fardouly, J. & Vartanian, L. R. (2016). Social media and body image concerns: Current research and future directions. Current Opinion in Psychology, 9, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Feingold, A. (1992). Good‐looking people are not what we think. Psychological Bulletin, 111, 304–341. [Google Scholar]

- Grabe, S. , Ward, L. M. & Hyde, J. S. (2008). The role of the media in body image concerns among women: A meta‐analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 460–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, S. & Stefanovski, A. (2019). Thinspiration and fitspiration in everyday life, an experience sampling study. Body Image, 30, 135–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groesz, L. M. , Levine, M. P. & Murnen, S. K. (2002). The effect of experimental presentation of thin media images on body satisfaction: A meta‐analytic review. International Journal of Eating Disorder, 31, 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, A.J. (2007). A more muscular female body ideal. In Thompson J.K. & Cafri G. (Eds.), The muscular ideal, psychological, social, and medical perspectives (pp. 217–234). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell, E. (2015). Future directions for positive body image research. Body Image, 14, 177–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modelling. Retrieved 20 July 2020 from http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis, A regression‐based approach (2nd edn). New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heinberg, L. J. & Thompson, J. K. (1995). Body image and televised images of thinness and attractiveness a controlled laboratory investigation. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 14, 325–338. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickse, J. , Arpan, L. M. , Clayton, R. B. & Ridgway, J. L. (2017). Instagram and college women's body image: Investigating the roles of appearance‐related comparisons and intrasexual competition. Computers in Human Behavior, 74, 92–100. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, G. & Tiggemann, M. (2016). A systematic review of the impact of the use of social networking sites on body image and disordered eating outcomes. Body Image, 17, 100–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell, A. N. & Weeks, J. W. (2017). Effects of gender role self‐discrepancies and self‐perceived attractiveness on social anxiety for women across social situations. Anxiety Stress and Coping, 30, 82–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D. C. (2001). Social comparison and body image, attractiveness comparisons to models and peers among adolescent girls and boys. Sex Roles, 45, 645–664. [Google Scholar]

- Kleemans, M. , Daalmans, S. , Carbaat, I. & Anschütz, D. (2018). Picture perfect, The direct effect of manipulated Instagram photos on body image in adolescent girls. Media Psychology, 21, 93–110. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, P. B. , Mansfield, P. K. , Thurau, D. & Carey, M. (2005). ‘‘Feeling frumpy": The relationships between body image and sexual response changes in midlife women. Journal of Sex Research, 42, 215–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvalem, I. L. , Træen, B. , Markovic, A. & von Soest, T. (2019). Body image development and sexual satisfaction, A prospective study from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Sex Research, 56, 791–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine, M. P. & Murnen, S. K. (2009). Everybody knows that mass media are/are not [pick one] a cause of eating disorders: A critical review of evidence for a causal link between media, negative body image, and disordered eating in females. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 28, 9–42. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, M. P. , Piran, N. & Stoddard, C. (1999). Mission more probable: Media literacy, activism, and advocacy as primary prevention. In Piran N., Levine M. P. & Steiner‐Adair C. (Eds.), Preventing eating disorders: A handbook of interventions and special challenges (pp. 3–25). Philadelphia, PA: Brunner/Mazel. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, E. P. & Gray, J. (2014). Facebook photo activity associated with body image disturbance in adolescent girls. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 17, 199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, K. R. & Orr, F. E. (1976). Heterosexual social competence, anxiety, avoidance, and self‐judged physical attractiveness. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 43, 553–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nezlek, J.B. (1988). Body image and day‐to‐day social interaction. Journal of Personality, 67, 793–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perloff, R. M. (2014). Social media effects on young women’s body image concerns: Theoretical perspectives and an agenda for research. Sex Roles, 71, 363–377. [Google Scholar]

- Pope, H. G. Jr , Phillips, K. A. & Olivardia, R. (2000). The Adonis complex: The secret crisis of male body obsession. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, L. , Prichard, I. , Nikolaidis, A. , Drummond, C. , Drummond, M. & Tiggemann, M. (2017). Idealised media images: the effect of fitspiration imagery on body satisfaction and exercise behavior. Body Image, 22, 65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saiphoo, A. N. & Vahedi, Z. (2019). A meta‐analytic review of the relationship between social media use and body image disturbance. Computers in Human Behavior, 101, 259–275. [Google Scholar]

- Salomon, I. & Spears Brown, C. (2017). The Selfie generation, examining the relationship between social media use and early adolescent body image. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 39, 539–560. [Google Scholar]

- Sherlock, M. & Wagstaff, D.L. (2018). Exploring the relationship between Instagram use: Exposure to idealized images, and psychosocial well‐being in women. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 8, 482–490. [Google Scholar]

- Slater, A. , Varsani, N. & Diedrichs, P.C. (2017). #fitspo or #loveyourself? The impact of fitspiration and self‐compassion Instagram images on women’s body image, self‐compassion, and mood. Body Image, 22, 87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes, R. & Frederick, C. (2003). Women's perceived body image, relations with personal happiness. Journal of Women & Aging, 15, 17–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J. K. , Heinberg, L. J. , Altabe, M. & Tantleff‐Dunn, S. (1999). Sociocultural theory: The media and society. Exacting beauty: Theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Tiggemann, M. & Barbato, I. (2018). “You look great!” The effect of viewing appearance‐related Instagram comments on women’s body image. Body Image, 27, 61–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiggemann, M. , Hayden, S. , Brown, Z. & Veldhuis, J. (2018). The effects of Instagram “likes” on women’s social comparison and body dissatisfaction. Body Image, 26, 90–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiggemann, M. & Zaccardo, M. (2015). “Exercise to be fit, not skinny”: The effect of fitspiration imagery on women’s body image. Body Image, 15, 61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiggemann, M. & Zaccardo, M. (2016). “Strong is the new skinny”: A content analysis of #fitspiration images on Instagram. Journal of Health Psychology, 23, 1003–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlmann, L. R. , Donovan, C. L. , Zimmer‐Gembeck, M. J. , Bell, H. S. & Ramme, R. A. (2018). The fit beauty ideal: A healthy alternative to thinness or a wolf in sheep’s clothing? Body Image, 25, 23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade, T.J. (2000). Evolutionary theory and self‐perception, sex differences in body esteem predictors of self‐perceived physical and sexual attractiveness and self‐esteem. International Journal of Psychology, 35, 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Wade, T. J. (2003). Evolutionary theory and African‐American self‐perception: Sex differences in body‐esteem predictors of self‐perceived physical and sexual attractiveness, and self‐esteem. Journal of Black Psychology, 29, 123–141. [Google Scholar]

- Wiederman, M.W. (2012). Body image and sexual functioning. In Cash T. F. (Ed.), Encyclopedia of body image and human appearance, vol 1 (pp. 169–173). Cambridge, MA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Woertman, L. & van den Brink, F. (2012). Body image and female sexual functioning and behaviour: A review. Journal of Sexual Research, 49, 184–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.