Abstract

Due to a shortage of donation after brain death (DBD) organs, donation after circulatory death (DCD) is increasingly performed. In the field of islet transplantation, there is uncertainty regarding the suitability of DCD pancreas in terms of islet yield and function after islet isolation. The aim of this study was to investigate the potential use of DCD pancreas for islet transplantation. Islet isolation procedures from 126 category 3 DCD and 258 DBD pancreas were performed in a 9‐year period. Islet yield after isolation was significantly lower for DCD compared to DBD pancreas (395 515 islet equivalents [IEQ] and 480 017 IEQ, respectively; p = .003). The decrease in IEQ during 2 days of culture was not different between the two groups. Warm ischemia time was not related to DCD islet yield. In vitro insulin secretion after a glucose challenge was similar between DCD and DBD islets. After islet transplantation, DCD islet graft recipients had similar graft function (AUC C‐peptide) during mixed meal tolerance tests and Igls score compared to DBD graft recipients. In conclusion, DCD islets can be considered for clinical islet transplantation.

Keywords: basic (laboratory) research/science, clinical research/practice, diabetes: type 1, donors and donation: donation after circulatory death (DCD), islet isolation, islet transplantation, islets of Langerhans, organ acceptance, regenerative medicine

Short abstract

This single‐center retrospective study compares 126 donation after circulatory death and 258 donation after brain death pancreatic islet isolations and demonstrates despite a substantially lower islet yield, islets from donation after circulatory death are as functional in vitro as in vivo in humans.

Abbreviations

- ALT

alanine transaminase

- AST

aspartate transaminase

- AUC

area under the curve

- BMI

body mass index

- CIT

cold ischemia time

- COD

cause of death

- DBD

donation after brain death

- DCD

donation after circulatory death

- GSIS

glucose‐stimulated insulin secretion

- HEPES

4‐(2‐hydroxyethyl)‐1‐piperazineethanesulfonic acid

- HTK

histidine‐tryptophan‐ketoglutarate solution

- IEQ

islet equivalents

- LIT

Lukewarm ischemia time

- LUMC

Leiden University Medical Center

- UWS

University of Wisconsin solution

- WIT

warm ischemia time

1. INTRODUCTION

Allogeneic transplantation of pancreatic islets is an effective treatment for patients with longstanding type 1 diabetes mellitus. 1 , 2 However, pancreatic islet isolations do not always yield a sufficient number of islets necessary for transplantation. Consequently, multiple donor pancreas are often needed in order to achieve a good clinical outcome. 3 In most Western countries, the availability of suitable donation after brain death (DBD) organs does not meet the current demand. 4 Due to this shortage, the acceptance criteria for donor pancreas have been extended, such as donation after circulatory death (DCD). 5 DCD procurement can either be uncontrolled (category 1 or 2) or controlled (category 3, 4, or 5). 6 , 7 In the Netherlands, about 50% of all organ procurement procedures are category 3 DCD, 8 providing a large source of donor pancreas for potentially transplantable islets.

In DBD procedures, cold preservation fluid can be perfused almost immediately after the aorta is clamped while there is still cardiac activity. 9 In controlled DCD procedures, however, death occurs after cardiac arrest. 10 The time period between the withdrawal of life support and cardiac arrest, known as the agonal phase, can vary greatly. 11 This can range from a couple of minutes to 2 h in most jurisdictions. 12

DCD procurement of other abdominal organs has shown that this procedure can provide suitable grafts for patients. 13 Although there is a 50% higher incidence of early graft loss, and an almost 150% higher incidence of delayed graft function in DCD kidney transplantation, 10‐year graft survival differs only slightly from DBD kidneys. 14 , 15 DCD liver transplantations are shown to have a higher risk of complications and higher rates of retransplantation. 16 Due to high mortality rates on the waiting lists, DCD livers are also used for liver transplantation, although they are associated with higher postoperative complications. 17 A recent retrospective analysis showed that DCD pancreas transplantation did not differ from DBD pancreas transplantation in terms of patient survival, 1‐year graft survival, or HbA1c after 1 year. 18 Still, an increased risk of graft thrombosis and bleeding has been reported. 19 , 20 , 21 , 22

Due to the inherent presence of a warm ischemia period in category 3 DCD compared to DBD procedures, the potential use of category 3 DCD pancreas for islet isolation and subsequent transplantation is unclear as there is a lack of larger studies. 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 Here we report on our extensive experience in isolation of pancreatic islets from DCD pancreas and our initial results on clinical outcome after transplantation of DCD islets.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Procurement

Donor pancreas were allocated to patients on the islet transplantation waiting list according to Eurotransplant guidelines. Pancreas were declined for clinical use when one or more of the following conditions were met: history of diabetes mellitus or HbA1c ≥ 6.5% (48 mmol/mol Hb), age >65 years, multiple cardiac arrests (DBD) or a combination of cardiac arrest and DCD, abdominal trauma, signs of current infection, or aberrant laboratory tests indicating pancreatic damage. For DCD procurements, pancreas were declined for allocation when the agonal phase (time from switch‐off to cardiac arrest) was longer than 120 min. During DCD procurement procedures, systolic pressure, diastolic pressure, and oxygen saturation were monitored during the agonal phase. A mandatory 5‐min no‐touch period after withdrawal of life support was observed for all DCD procurements. Also, the time of cardiac arrest and the start of the perfusion of cold preservation solution were recorded. In addition, for DBD and DCD pancreas, lukewarm ischemia time (LIT) was defined as the time between the start of cold preservation fluid perfusion and pancreatectomy. Cold ischemia time (CIT) was defined as the time between pancreatectomy and infusion of digestive enzymes into the pancreatic duct. These time periods are summarized in Figure 1. Organs were transported in either University of Wisconsin (UW) solution or histidine‐tryptophan‐ketoglutarate (HTK) solution on ice to the human islet isolation laboratory of the Leiden University Medical Center in the Netherlands.

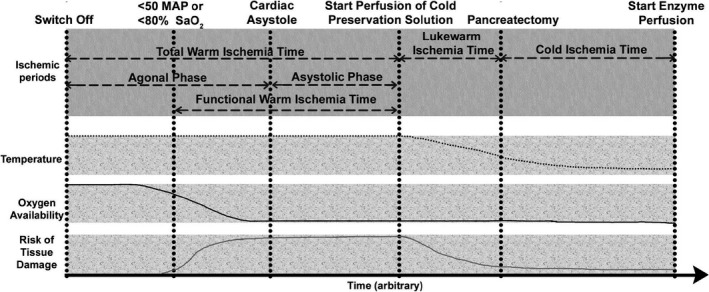

FIGURE 1.

Definitions regarding periods of ischemia in organ procurement and transportation until the start of islet isolation for DCD pancreas procedures. Critical hemodynamic moments are indicated at the top part of the figure: life support “switch off,” the moment when organ perfusion is inadequate (mean arterial pressure [MAP] drops below 50 and/or O2 saturation drops below 80%), cardiac asystole (and thereafter a “no‐touch” period), the start of cold preservation fluid perfusion, pancreatectomy, and the start of enzyme perfusion. Several ischemic periods can be defined between these time points. The total warm ischemia (tWIT) time starts at the switch off of life support and ends when cold preservation solution is perfused. The agonal phase measures the length of time between ceasing circulatory support and cardiac asystole. Functional warm ischemia time (fWIT) indicates the time that organs experience warm, inadequate oxygenation, and perfusion (time between the MAP dropping below 50 mm Hg and/or the O2 saturation dropping below 80% until the start of cold preservation fluid perfusion). The lukewarm ischemia time (LIT) is defined as the time between the infusion of cold preservation fluid perfusion and pancreatectomy. The cold ischemia time (CIT) is the time from pancreatectomy until the infusion of digestive enzymes in the pancreas in the islet isolation facility. During the tWIT, a normothermic temperature persists. The temperature decreases during LIT when ice is packed into the abdominal cavity resulting in a gradual decrease in cell metabolism. In the CIT period, the temperature of the pancreas slowly plateaus. At the start of the agonal phase, the pancreas receives sufficient oxygenation. When perfusion becomes inadequate, at the start of the fWIT, the availability of oxygen to the pancreas decreases. Around the start of the asystolic phase, there is anoxemia. The combination of a suboptimal temperature and insufficient oxygenation results in an increasing risk of tissue damage. Actual damage is an outcome of ischemic periods combined with the risk of tissue damage

2.2. Islet isolations

Between 2008 and 2017, all human pancreatic islet isolations were performed at the Leiden University Medical Center using an adapted version of the semi‐automated method. 27 The same islet isolation procedure was performed for both DBD and DCD organs. Briefly, after removal of peripancreatic tissue, the main pancreatic duct was cannulated with either an intravenous catheter at the head of the pancreas for retrograde enzyme infusion, or with two intravenous catheters inserted in the main pancreatic duct in the body of the pancreas for antegrade and retrograde enzyme infusion. When using the single catheter technique, a second 3.5 CH catheter was also inserted through the original catheter to reach the end of the tail of the pancreas. Hereafter, the pancreas was perfused by a pump with a blend of Collagenase NB1 (2000 Wünsch units, dissolved in 20 ml) and Neutral Protease NB1 (100–200 dimethyl‐casein units, dissolved in 10–20 ml) for 15–45 min (both enzymes from SERVA Electrophoresis GmbH). After full distention, the pancreas was cut, and the pieces were transferred to a digestion chamber. A 400 µm mesh was placed on top of the chamber to prevent outflow of undigested tissue. A continuous flow of Ringer's acetate (B. Braun) solution, supplemented with 5% 0.1 mol/L sodium pyruvate (Lonza), 2.1 mg/ml nicotinamide (LUMC Pharmacy), 4.5 mmol/L glucose (LUMC Pharmacy), 0.17 mmol/L NaHCO3 (Lonza), 25 mmol/L HEPES (Lonza), and pulmozyme (Roche AB), and adjusted pH to 7.4 with 1 mol/L NaOH (LUMC Pharmacy) at 200 ml/min circulated through the system, while maintaining a temperature of 37°C. The digestion chamber (Ricordi Isolator, Biorep) was shaken during the digestion phase. Digested pancreatic tissue was collected in 250 ml conical tubes with 3 ml freshly thawed human serum, pooled, washed with UW solution (Bridge to Life or Viaspan, DuPont), supplemented with 5% 0.1 mol/L sodium pyruvate, 1.2 mg/ml nicotinamide (LUMC Pharmacy), pulmozyme (Roche AB), and stored at 4°C. The digest was then purified in a continuous density gradient, made by mixing Biocoll (Biochrom Seromed KG) with a density of 1.100 g/ml with either UW solution (density 1.045 g/ml) or Biocoll (with a density of 1.077 g/ml) using two computer‐controlled peristaltic pumps (Lambda) in an air‐cooled COBE 2991 centrifuge (Terumo BCT). A maximum of 30 ml pancreatic digest was loaded into the centrifuge for each purification run. After 5 min of spinning at 400 g, the digest was harvested in 12 fractions and washed in Ringer Acetate solution (supplemented with 1% freshly thawed human serum [Sanquin]). Selected fractions, based on purity and amount of embedding, were cultured using CMRL 1066 (Mediatech), supplemented with 10% human serum, 10 mmol/L HEPES, 2 mmol/L L‐glutamine, 50 µg/ml gentamycin, 0.25 µg/ml Fungizone (GIBCO BRL), and 20 µg/ml Ciprofloxacin (Bayer Healthcare AG) at 37°C in 5% CO2. The purity and degree of embedding were assessed visually using dithizone staining and were verified by a second operator. The culture medium was refreshed 1 day later, and subsequently every day or every other day for up to 5 days.

Islet yield (in islet equivalents, IEQ) was determined 28 after isolation (day 0) and the number of IEQ was also assessed after the first medium change (MC1) 1 day after isolation, and after the second medium change (MC2), generally 2 or 3 days after isolation.

2.3. Glucose‐stimulated insulin secretion test

Functionality of isolated islets was tested at MC1 using a dynamic glucose‐stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) test. Islet samples (±20 islets) were collected and were placed in filter‐closed chambers (Suprafusion 1000, Brandel) and perifused at 500 µl/min at 37°C. First, islets in each channel were preconditioned by perifusion with a low‐glucose solution (1.7 mmol/L glucose) (20 mmol/L HEPES, 11.5 mmol/L NaCl, 0.5 mmol/L KCl, 2 mmol/L CaCl2, 1 mmol/L MgCl2, and 2.4 mmol/L NaHCO3, supplemented with 0.2% human serum albumin in demineralized water) for 90 min. Thereafter, the islets were perifused with low‐glucose solution for 15 min followed by a high‐glucose solution (same as low‐glucose solution, but with 20 mmol/L glucose) for 60 min and finally with a low‐glucose solution for 75 min. Fractions were collected at 7.5‐min intervals. The fractions were then measured for insulin using an immunoassay specific for human insulin (Mercodia AB). The insulin concentration at each time point was then divided by the average insulin concentration of the last three insulin concentrations during the low‐glucose phase. This stimulation index per time point was averaged for DCD (n = 27) and DBD (n = 102) donors. To calculate the area under the curve of the stimulation indices, the stimulation index curves were integrated over time.

2.4. Islet transplantations

Islet preparations were used for transplantation if the islet preparation was >5000 IEQ/kg recipient, the medium containing the islets was negative for Gram staining, the endotoxin test of the medium was ≤0.1 EU/kg recipient, proper islet morphology was present, the islet purity was ≥30%, and the stimulation index of static glucose‐stimulated insulin secretion test was >1.5. If the yield from a single preparation was insufficient for transplantation, islet preparations could be maintained in culture for up to 6 days, to allow the possibility of combining two islet preparations in one infusion procedure.

2.5. Patients

Patients in our study had severe beta‐cell failure and were referred to the transplantation outpatient clinic of the Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC) for beta cell replacement therapy. They were considered eligible for islet‐after‐kidney, islet‐after‐lung, or islet alone transplantation. Data regarding inclusion criteria and immunosuppression therapy have been published previously. 29 If after 3 months, the preset treatment goals (i.e., HbA1c < 53 mmol/mol Hb without severe hypoglycemia, simplification, or abrogation of the insulin regimen) were not met, additional transplantations could be performed.

2.6. Assessment of islet graft function

Three months after transplantation, mixed meal tests were performed in order to evaluate islet graft function. 29 In short, blood samples were drawn at −10, 0, 15, 30, 60, and 120 min. The values obtained for stimulated C‐peptide (pmol/L) and glucose (mmol/L) were corrected for the transplanted islet dose (IEQ/kg recipient) for each test. Results were grouped according to the type of islet graft (patients receiving only DBD preparations [n = 31] or patients receiving only DCD islet preparations [n = 9]). Three patients received a combined DBD+DCD transplantation and were excluded from analysis. The area under the C‐peptide curve and area under the glucose curve were calculated for both groups. To evaluate clinical outcome, the Igls 30 score at 1 year and 2 years after the last transplantation was determined for DBD and DCD islet graft recipients (Table S2). Igls score 1 (Optimal) and score 2 (Good) were considered treatment success, and score 3 (Marginal) and score 4 (Failure) were considered unsuccessful treatments.

2.7. Statistical analysis

UNIANOVA (IBM SPSS Statistics v21) was used for multivariate analysis of significant and relevant donor characteristic differences between DCD and DBD groups, namely age, BMI, sex, CIT, last reported glucose concentration, and height. Student's t test was used to calculate p‐values for comparisons between DCD and DBD islets, ANOVA when more than two groups were compared, and Chi‐square test when comparing dichotomous variables, using GraphPad Prism 5.01. Values are given as mean ± SD, unless otherwise specified.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Donor characteristics

In a 9‐year period, islets were isolated from 384 donor pancreas. There were 126 category 3 DCD pancreas and 258 DBD pancreas. Donor characteristics are presented in Table 1. DCD donors were younger (46.6 ± 13.1 vs. 51.8 ± 12.0 years, p < .001) and more often male (59.7% vs. 47.9%, p = .02) compared to DBD donors. Furthermore, DCD donors had non‐significantly longer hypotensive periods (i.e., systolic blood pressure <80 mm Hg prior to donation) than DBD donors (41.2 ± 66.5 vs. 23.0 ± 26.6 min, p = .08), but were also given vasopressor support less often (56.5% vs. 87.4%, p < .001). The last measured glucose concentration was lower (7.9 ± 2.7 vs. 9.4 ± 3.1 mmol/L, p < .001) in DCD donors. The average functional WIT in the DCD group was 23.2 ± 6.4 min. Other donor characteristics did not differ significantly between the groups.

TABLE 1.

Donor characteristics of included donation after brain death (DBD) and donation after circulatory death (DCD) donors

| DCD | DBD | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 46.6 ± 13.1 | 51.2 ± 12.0 | p < .001 |

| Sex (% male) | 59.7 | 47.9 | p = .02 |

| Weight (kg) | 80.1 ± 16.6 | 78. 9 ± 16.4 | p = .49 |

| Height (cm) | 176.6 ± 9.2 | 174.3 ± 9.6 | p = .03 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.4 ± 4.3 | 26.0 ± 4.2 | p = .21 |

| Stroke or SAB (%) | 45.2 | 69.6 | p < .001 |

| Hypotensive period registered | 22% | 32% | p = .05 |

| Hypotensive period duration (min) | 41.2 ± 66.5 | 23.0 ± 26.6 | p = .08 |

| Creatinine (µmol/L) | 77.1 ± 34.3 | 73.7 ± 33.7 | p = .37 |

| Bilirubin (µmol/L) | 10.4 ± 6.6 | 11.7 ± 8.2 | p = .15 |

| GGT (U/L) | 63.7 ± 90.8 | 63.8 ± 135.1 | p = .99 |

| ALT (U/L) | 66.6 ± 167.5 | 51.7 ± 81.4 | p = .26 |

| AST (U/L) | 80.1 ± 141.6 | 63.8 ± 91.4 | p = .19 |

| Lipase (U/L) | 42.4 ± 68.3 | 33.3 ± 41.5 | p = .29 |

| Amylase (U/L) | 130.6 ± 227.3 | 144.2 ± 223.5 | p = .61 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 35.0 ± 4.1 | 36.0 ± 5.0 | p = .13 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.3 ± 0.37 | 5.4 ± 0.46 | |

| Vasopressor use (%) | 56.5 | 87.4 | p < .001 |

| Blood glucose (mmol/L) | 7.9 ± 2.7 | 9.4 ± 3.1 | p < .001 |

| Donor points 44 | 64.6 ± 12.1 | 66.6 ± 10.4 | p = .09 |

| NAIDS 73 | 44.0 ± 20.8 | 47.5 ± 20.2 | p = .11 |

Values are given as mean ± SD (n). DCD n = 126. DBD n = 258.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; SAB, subarachnoidal bleeding; GGT, gamma‐glutamyl transferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; HbA1c,hemoglobin A1c; NAIDS, North American Islet Donor Score.

3.2. DCD and DBD pancreas characteristics before and during islet isolation

The mean trimmed weight of the pancreas was similar in the DCD group compared to the DBD group (112 ± 25.4 vs. 107 ± 26.5 grams, p = .06), as presented in Table 2. Also, mean CIT was not significantly different in the DCD group (9.17 ± 3.40 vs. 8.50 ± 3.20 h, DCD vs. DBD, respectively, p = .06). Until 2013, HTK solution was preferred for DCD procedures, and this resulted in a significant difference in the type of perfusate used during procurement (60.1% UW usage for DCD procedures and 87.7% UW usage for DBD procedures, p < .001).

TABLE 2.

Pancreas, preservation, and procurement parameters of donation after brain death (DBD) and donation after circulatory death (DCD) donors

| DCD | DBD | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| UW solution (%) | 60.2 | 87.7 | p < .001 |

| Pancreas weight (g) | 112.2 ± 25.4 | 106.9 ± 26.5 | p = .06 |

| Functional WIT (min) | 23.2 ± 6.4 | NA | NA |

| CIT (h) | 9.2 ± 3.4 | 8.5 ± 3.2 | p = .06 |

Values are given as mean ± SD (n). DCD n = 126. DBD n = 258.

Abbreviations: CIT, cold ischemia time; UW, University of Wisconsin solution; WIT, warm ischemia time.

During islet isolation, enzymatic digestion was more complete during DCD pancreas than DBD pancreas isolation (14.1 ± 0.8% vs. 16.5 ± 1.0% undigested tissue after digestion p = .03). However, after multivariate analysis, this difference was no longer significant (difference DCD‐DBD: −0.054 ± 0.759, p = .84). The total volume of tissue to be purified did not significantly differ between DCD and DBD pancreas (43.8 ± 18.0 vs. 40.9 ± 17.7 ml, p = .14).

3.3. Isolation outcome

Post‐purification, the islet yield from DCD pancreas was 84 502 IEQ lower compared to DBD pancreas (p = .003; see Table 3). When accounting for the mass of a pancreas, DCD pancreas also yielded fewer islets per gram tissue (1432 IEQ/g less, p < .001). There was also a difference in volume between DCD and DBD preparations post‐purification. After density separation, the culture tissue volume was 353 µL lower for DCD pancreas, than for DBD pancreas (p = .02). Not only did DCD pancreas have a lower islet yield and a lower culture tissue volume, islets from DCD pancreas separated worse during density separation. This was reflected in the maximum purity obtained after purification which was lower in DCD pancreas (84.7 ± 13.9%) than DBD pancreas (88.2 ± 12.9%, p = .01). However, when examining the average purity of islets brought into culture, DCD and DBD preparations did not differ (55.1 ± 14.2 vs. 56.5 ± 16.2%, p = .43). During culture, the number of IEQ decreased in both groups but the percentage decrease did not differ between DCD and DBD islets (Figure 2).

TABLE 3.

Islet isolation outcome parameters

| DCD | DBD | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IEQ day 0 | 395 515 ± 239 287 | 480 017 ± 273 449 | p = .003 |

| IEQ MC1 | 387 341 ± 283 763 | 472 831 ± 294 768 | p = .014 |

| IEQ MC2 | 330 112 ± 275 280 | 398 399 ± 227 854 | p = .132 |

| Change in IEQ day 0→MC1 (%) | −6.0 ± 38.2 | −6.88 ± 32.3 | p = .83 |

| IEQ drop >30%, >40%, >50% (%) | 26.7%, 16.8%, 8.9% | 23.4%, 14.0%, 5.4% | |

| Change in IEQ day 0→MC2 (%) | −30.1 ± 32.2 | −25.0 ± 27.62 | p = .34 |

| Undigested tissue (%) | 14.1 ± 0.81 | 16.5 ± 1.02 | p = .03 |

| Prepurification pellet volume (ml) | 43.8 ± 18.0 | 40.86 ± 17.71 | p = .14 |

| Culture tissue volume (µl) | 1724 ± 1093 | 2077 ± 1554 | p = .02 |

| IEQ/g digested tissue | 4254 ± 2577 | 5686 ± 3220 | p < .001 |

| Average purity (%) | 55.1 ± 14.2 | 56.5 ± 16.16 | p = .43 |

| Maximum purity (%) | 84.7 ± 13.9 | 88.2 ± 12.9 | p = .01 |

Values are given as mean ± SD. In multivariate analysis, IEQ day 0 (p < .01), IEQ MC1 (p = .03), culture tissue volume (p = .01), IEQ/g digested tissue (p = .01), and maximum purity (p = .01) remained significantly different. DCD n = 126. DBD n = 258.

Abbreviations: IEQ, islet equivalents; MC1, first medium change on day 1; MC2, second medium change usually on day 2–3.

FIGURE 2.

IEQ of DBD and DCD isolations immediately after isolation (day 0), at 1 day (MC1) and at 2–3 days (MC2) after isolation. At day 0, DCD islet yield was 395 515 IEQ (239 287) and DBD islet yield was 480 017 IEQ (273 449; p < .01). The decrease in IEQ after successive medium changes (MC1 and MC2) was similar in DCD and DBD pancreas. DCD n = 126. DBD n = 258

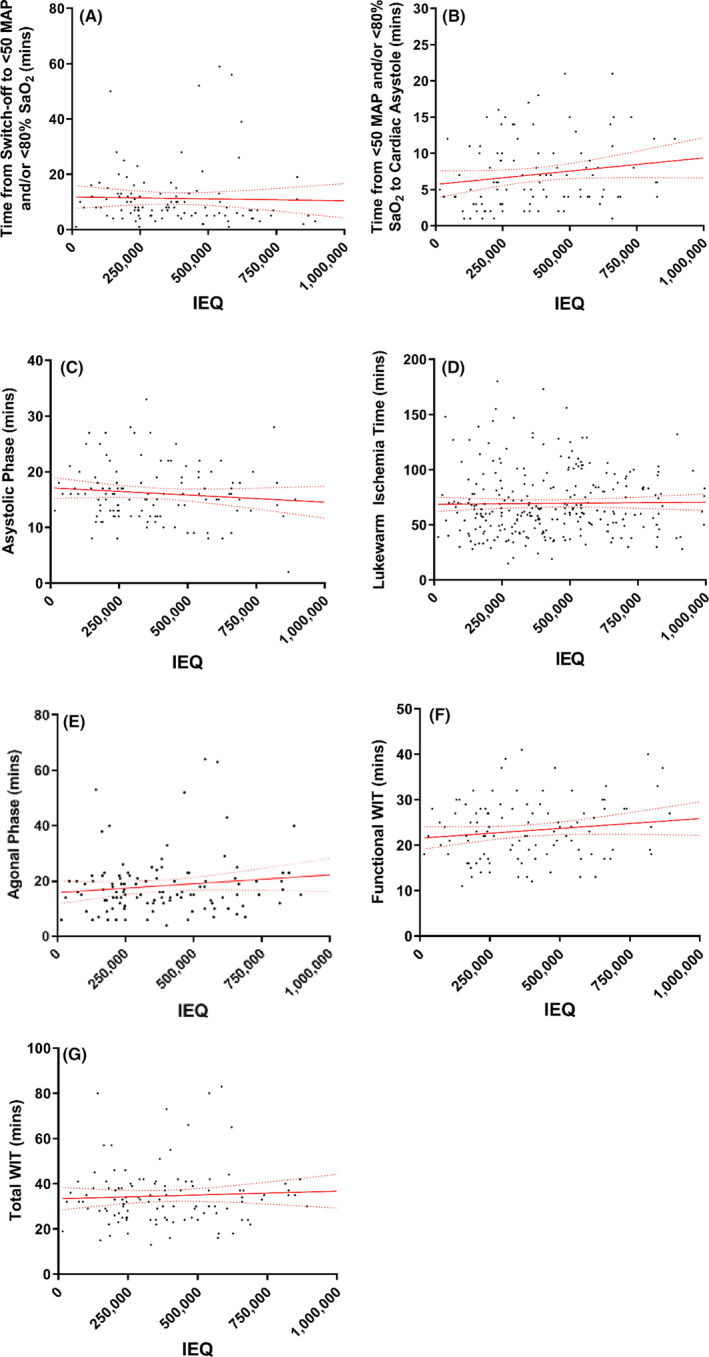

After multivariate analysis, the differences in IEQ, IEQ/g, maximum purity, and islet culture volume persisted (p < .01, p < .01, p = .01, and p = .01, respectively). No significant correlations were found between different warm ischemia periods and islet yield (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Association of ischemia periods with islet yield. (A–D) show the relation between ischemic time periods and islet yield. E‐G show the relation between islet yield and agonal phase (E), functional WIT (F), and total WIT (G). No associations are significant [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.4. In vitro functionality

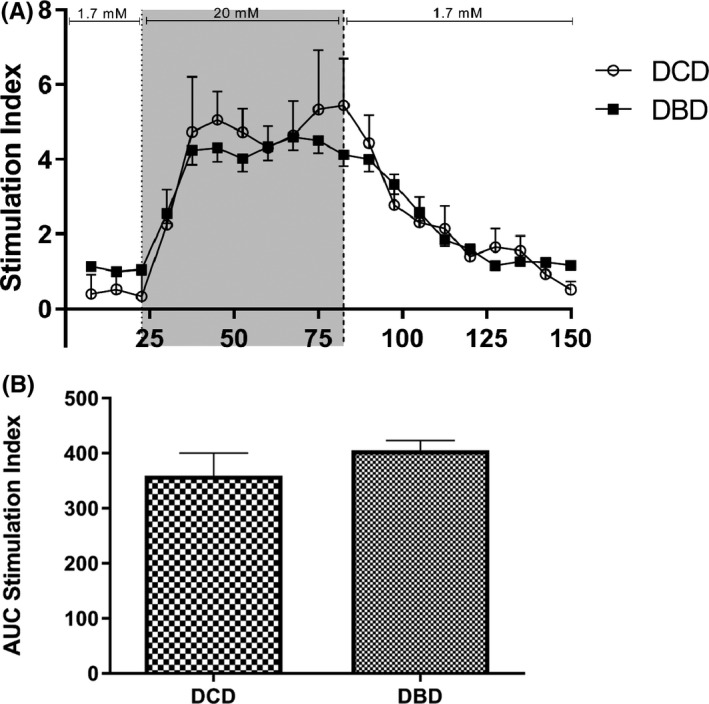

Islet preparations considered for transplantation were assessed by GSIS. No significant differences were found between DCD and DBD islets in terms of peak stimulation index or area under the stimulation index curve (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Dynamic glucose‐stimulated insulin secretion test. (A) After 1 day of culture, islets were perifused with a low glucose (1.7 mmol/L) solution, a high glucose (20 mmol/L) solution, and finally the low glucose solution. The average of the last three low glucose values was defined as the baseline value. The insulin concentration at each time point was then divided by the baseline to give the stimulation index at each time point. A similar response is present in both DCD and DBD islets. Peak stimulation index values of DCD islets (5.4 ± 2.7, n = 27) and DBD islets (4.6 ± 2.9, n = 102) are not significantly different (p = .30). (B) The stimulation index curves were integrated over time to calculate the area under the curve of the stimulation index for DCD and DBD islets. No significant difference between DCD islets (295.0 ± 49.7, n = 27) and DBD islets (270.7 ± 19.0, n = 102) islets was observed, p = .64

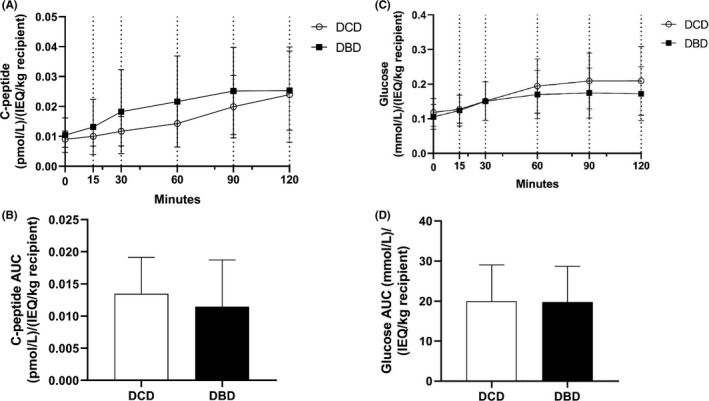

3.5. Transplantations with DCD and/or DBD islets

Included patients were administered a single DCD or a single DBD islet preparation or a combined preparation (two DCD or two DBD islet preparations). Three months after the islet transplantation, insulin secretary capacity of the grafts was measured after a mixed meal challenge. The area under the C‐peptide curve was similar between DCD and DBD graft recipients (Figure 5b, p = .41). In addition, the area under the glucose curve was not different between the two groups (Figure 5d, p = .94).

FIGURE 5.

Graft function 3 months after islet transplantation. Mixed meal tests were performed in single or double DCD graft recipients (DCD, n = 9) and in single or double DBD graft recipients (DBD, n = 31). C‐peptide (pmol/L) and glucose (mmol/L) were corrected for the number of islets per kg recipient. (A) C‐peptide concentrations during the mixed meal test. The increase in C‐peptide was similar in DBD and DCD graft recipients. (B) The area under the C‐peptide curve was not different between DCD and DBD graft recipients (DCD 0.013 ± 0.0057, DBD 0.011 ± 0.0072, p = .41). (C) Glucose concentrations during the mixed meal test. The increase in glucose was similar in DBD and DCD graft recipients. (D) The area under the glucose curve was not different between DCD and DBD graft recipients (DCD 20.0 ± 9.0, DBD 19.8 ± 8.9, p = .94)

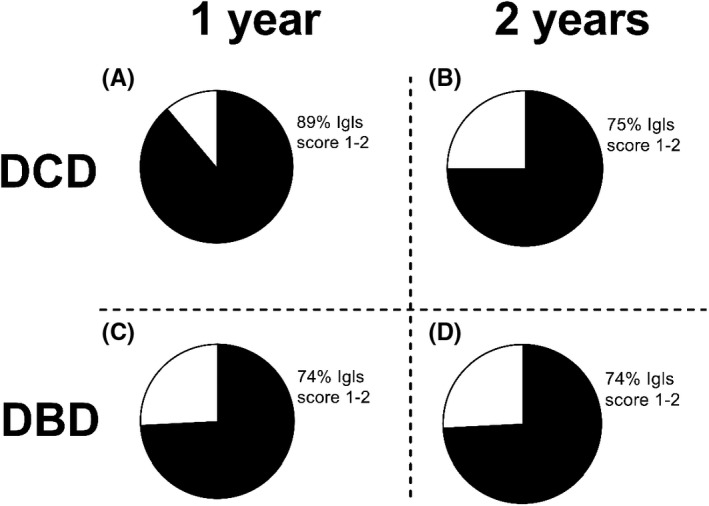

To determine clinical graft function, Igls scores 1 year and 2 years after the last transplantation were calculated (Figure 6). After 1 year, treatment success was attained in 89% DCD recipients (n = 9) and in 74% of DBD recipients (n = 31, p = .65). After 2 years, this diminished to 75% (n = 8) and 74%, respectively (n = 30, p > .99).

FIGURE 6.

Igls scores were assessed at 1 year (A,C) and 2 years (B,D) after the islet transplantation. (A) After 1 year, 89% of DCD islet graft recipients and 74% of DBD islet graft recipients have Igls score 1 or 2 indicating treatment success (p = .65). At 2 years after the last transplantation, this was 75% and 74% in DCD and DBD islet graft recipients, respectively (p > .99). DCD n = 9, DBD n = 31 at 1 year. DCD n = 8, DBD n = 30 at 2 years

4. DISCUSSION

The main findings of our study on islet isolation from 126 category 3 DCD pancreas indicate that DCD pancreas can be used for islet isolation and transplantation. Islet secretory function and clinical outcome were similar up to 2 years after islet transplantation in recipients receiving only DCD islet grafts compared to recipients receiving only DBD grafts.

Donor characteristics from the DCD and DBD groups differed in several aspects. The DCD donors were younger, were more often male, had a longer hypotensive period, required less vasopressor support, and the last glucose concentration was lower. Of these factors, age and sex of the donor have been shown to have an influence on the isolation results in several previous publications. 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 These data indicate that in our center, donor characteristics are more favorable for DCD donors compared to DBD donors. Also in other transplantation fields, DCD organ acceptance is characterized by more favorable other donor characteristics. 15 , 48

In a porcine study, a warm ischemia time of more than 30 min impaired in vitro islet function. 49 In our cohort of category 3 DCD and DBD pancreas, islet functionality in vitro is not affected by organ procurement type, as evidenced by dynamic glucose‐stimulated insulin secretion. It should be noted that the average functional warm ischemia time was 23.2 min with a maximum of 41 min. Our findings of the responsiveness of DCD islets to glucose are in line with previous studies which used static glucose‐stimulated insulin secretion tests. 23 , 25 , 26

Using identical isolation protocols, our results showed an approximately 85,000 lower post‐purification IEQ after islet isolation from DCD pancreas compared to DBD pancreas. Our study on 126 DCD pancreas is in line with one other study that observed 100 000 IEQ less from 10 DCD pancreas. 24 Two previous studies with relatively small numbers of category 3 DCD pancreas (≤15 per study) reported similar islet yields obtained from category 3 DCD and DBD donors 23 , 25 and one small study reported 100 000 more IEQ from 10 DCD pancreas, 26

Several studies have been reported on controlled DCD procedures from Japan in which a rapid in situ regional organ cooling technique was used. 34 , 50 , 51 , 52 This allows for much shorter warm ischemia times (WIT of 4.2 ± 0.7 min 51 ), compared to what is possible using category 3 DCD procedures. The initial results from 10 category 4 DCD pancreas yielded a mean IEQ > 400 000, but were not compared to DBD pancreas. 52

Islet isolation from DCD pancreas resulted in a lower islet yield, but the warm ischemia, that is present during DCD and that can potentially adversely affect islet viability, does not appear to lead to a decline in islet number during a culture period of several days. Studies in rats have shown improved viability in DCD rat islets, compared to DBD rat islets after isolation. 53 , 54 Small human studies (<15 DCD pancreas for islet isolation) reported no difference in viability between DCD and DBD islets after isolation. 25 , 26 In islets from DCD pancreas, a correlation between longer WIT and lower ATP and GTP contents was found, suggesting that DCD islets may contain less energy reserves than DBD islets. Importantly, DCD islets were able to maintain blood glucose levels as well as DBD islets in mice 7 days posttransplant. 26

Three months after islet transplantation, no difference was observed in islet functionality after a mixed meal challenge in our cohort. Reports on transplantations with DCD islets are scarce. A single islet transplantation isolated from a DCD pancreas was reported in 2003, with a reduction in daily insulin requirement, improved glycemic control, and absence of hypoglycemic events. 24 Another report using nine category 3 DCD and 196 DBD islets also reported no difference in insulin independence and decrease in insulin requirement between procurement types. 25 The Japanese Islet Transplant Registry published results from 18 recipients receiving category 4 DCD islet preparations. 55 After 3 years, 33.6% maintained a C‐peptide level more than or equal to 0.3 ng/ml. All recipients remained free of severe hypoglycemic events and three achieved insulin independence for 14, 79, and 215 days in that study. We observed that DCD islet preparations did not negatively affect patient's clinical treatment outcome using the Igls score at 1 and 2 years after transplantation.

Different recommendations for a maximal total WIT for islet isolations have been made in the past (30, 45, and 60 min). These were based on either data from kidney transplantations, porcine studies, or were inferred from small studies in which a statistically significant cut‐off could not be found. 24 , 25 , 56 , 57 In our study, neither the duration of the total warm ischemia time nor other procurement‐related ischemic periods affected the yield. Thus, other factors during the DCD procedure are likely to play a more important role. Exactly which physiological differences occur during DCD procurement that lead to a lower IEQ yield remains a question for further research.

Previous research has found a multitude of donor characteristics which can have an effect on islet isolation outcome: a well‐trained local procurement team, 40 , 41 , 45 , 58 donor age, 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 batch and type of collagenase, 38 , 40 , 43 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 sex of the donor, 40 , 41 , 42 CIT, 35 , 43 , 46 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 amylase, 67 preservation solution, 68 , 69 and BMI. 40 , 42 , 45 , 46 , 70 , 71 The discrepancy in islet isolation yield between DCD and DBD pancreas may diminish in the future due to developing technologies such as normothermic regional perfusion prior to procurement and machine perfusion (after procurement). 68 , 72

When a cautious approach is used related to donor characteristics, islet isolations from category 3 DCD pancreas result in a lower yield than isolations from DBD pancreas, but DCD islets are as functional in vitro and after clinical transplantation as DBD islets.

DISCLOSURE

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

JBD: Participated in research design, writing of the paper, performance of the research, and data analysis. MFN: Participated in writing of the paper, and performance of the research. MAE: Participated in research design, writing of the paper, and performance of the research. EJPdK: Participated in research design, writing of the paper, and performance of the research.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data available on request from the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1. Shapiro AMJ, Lakey JRT, Ryan EA, et al. Islet transplantation in seven patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus using a glucocorticoid‐free immunosuppressive regimen. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(4):230‐238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Foster ED, Bridges ND, Feurer ID, Eggerman TL, Hunsicker LG, Alejandro R. Improved health‐related quality of life in a phase 3 islet transplantation trial in type 1 diabetes complicated by severe hypoglycemia. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(5):1001‐1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hering BJ, Ansite JD, Eckman PM, Parkey J, Hunter DW, Sutherland DER. Single‐donor, marginal‐dose islet transplantation in patients with type 1 diabetes. JAMA. 2005;293(7):830‐836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network . Organ Donation and Transplantation Statistics. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/. Published 2018. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- 5. Proneth A, Schnitzbauer AA, Zeman F, et al. Extended pancreas donor program – the EXPAND study rationale and study protocol. Transplant Res. 2013;2(1):12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Detry O, Le Dinh H, Noterdaeme T, et al. Categories of donation after cardiocirculatory death. Transplant Proc. 2012;44(5):1189‐1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kootstra G, Daemen JH, Oomen AP. Categories of non‐heart‐beating donors. Transplant Proc. 1995;27(5):2893‐2894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Eurotransplant . Donors used in Netherlands, by year, by donor type. https://statistics.eurotransplant.org/reportloader.php?report=52901‐6008&format=html&download=0. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- 9. Starzl TE, Hakala TR, Shaw BW, et al. A flexible procedure for multiple cadaveric organ procurement. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1984;158(3):223‐230. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Allen MB, Billig E, Reese PP, et al. Donor hemodynamics as a predictor of outcomes after kidney transplantation from donors after cardiac death. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(1):181‐193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sohrabi S, Navarro A, Asher J, et al. Agonal period in potential non‐heart‐beating donors. Transplant Proc. 2006;38(8):2629‐2630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sohrabi S, Navarro A, Wilson C, et al. Renal graft function after prolonged agonal time in non‐heart‐beating donors. Transplant Proc. 2006;38(10):3400‐3401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bellingham JM, Santhanakrishnan C, Neidlinger N, et al. Donation after cardiac death: a 29‐year experience. Surgery. 2011;150(4):692‐702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Summers DM, Watson CJE, Pettigrew GJ, et al. Kidney donation after circulatory death (DCD): state of the art. Kidney Int. 2015;88(2):241‐249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schaapherder A, Wijermars LGM, de Vries DK, et al. Equivalent long‐term transplantation outcomes for kidneys donated after brain death and cardiac death: conclusions from a nationwide evaluation. EClinicalMedicine. 2018;5:25‐31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Monbaliu D, Pirenne J, Talbot D. Liver transplantation using donation after cardiac death donors. J Hepatol. 2012;56(2):474‐485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mateo R, Cho Y, Singh G, et al. Risk factors for graft survival after liver transplantation from donation after cardiac death donors: an analysis of OPTN/UNOS data. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(4):791‐796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. van Loo ES, Krikke C, Hofker HS, Berger SP, Leuvenink HGDD, Pol RA. Outcome of pancreas transplantation from donation after circulatory death compared to donation after brain death. Pancreatology. 2017;17(1):13‐18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Muthusamy ASR, Mumford L, Hudson A, Fuggle SV, Friend PJ. Pancreas transplantation from donors after circulatory death from the United Kingdom. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(8):2150‐2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Suntharalingam C, Sharples L, Dudley C, Bradley JA, Watson CJE. Time to cardiac death after withdrawal of life‐sustaining treatment in potential organ donors. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:2157‐2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Salvalaggio PR, Davies DB, Fernandez LA, Kaufman DB. Outcomes of pancreas transplantation in the United States using cardiac‐death donors. Am J Transpl. 2006;6(5 Pt 1):1059‐1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. D’Alessandro AM, Fernandez LA, Chin LT, et al. Donation after cardiac death: the university of wisconsin experience. Ann Transplant. 2004;9(1):68‐71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Clayton H, Swift S, Turner J, James R, Bell PRF. Non‐heart‐beating organ donors: a potential source of islets for transplantation? Transplantation. 2000;69(10):2094‐2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Markmann JF, Deng S, Desai NM, et al. The use of non‐heart‐beating donors for isolated pancreatic islet transplantation. Transplantation. 2003;75(9):1423‐1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Andres A, Kin T, O'Gorman D, et al. Clinical islet isolation and transplantation outcomes with deceased cardiac death donors are similar to neurological determination of death donors. Transpl Int. 2016;29(1):34‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhao M, Muiesan P, Amiel SA, et al. Human islets derived from donors after cardiac death are fully biofunctional. Am J Transplant. 2007;7(10):2318‐2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ricordi C, Lacy PE, Finke EH, Olack BJ, Scharp DW. Automated method for isolation of human pancreatic islets. Diabetes. 1988;37(4):413‐420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Friberg AS, Brandhorst H, Buchwald P, et al. Quantification of the islet product: presentation of a standardized current good manufacturing practices compliant system with minimal variability. Transplantation. 2011;91(6):677‐683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nijhoff MF, Engelse MA, Dubbeld J, et al. Glycemic stability through islet‐after‐kidney transplantation using an alemtuzumab‐based induction regimen and long‐term triple‐maintenance immunosuppression. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(1):246‐253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rickels MR, Stock PG, de Koning EJP, et al. Defining outcomes for β‐cell replacement therapy in the treatment of diabetes: a consensus report on the Igls criteria from the IPITA/EPITA Opinion Leaders Workshop. Transplantation. 2018;102(9):1479‐1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Briones RM, Miranda JM, Mellado‐Gil JM, et al. Differential analysis of donor characteristics for pancreas and islet transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2006;38(8):2579‐2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zeng Y, Torre MA, Karrison T, Thistlethwaite JR. The correlation between donor characteristics and the success of human islet isolation. Transplantation. 1994;57(6):954‐958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ihm S‐H, Matsumoto I, Sawada T, et al. Effect of donor age on function of isolated human islets. Diabetes. 2006;55(5):1361‐1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu X, Matsumoto S, Okitsu T, et al. Analysis of donor‐ and isolation‐related variables from non‐heart‐beating donors (NHBDs) using the Kyoto islet isolation method. Cell Transplant. 2008;17:649‐656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hilling DE, Bouwman E, Terpstra OT, Marang‐van de Mheen PJ. Effects of donor‐, pancreas‐, and isolation‐related variables on human islet isolation outcome: a systematic review. Cell Transplant. 2014;23(8):921‐928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Niclauss N, Bosco D, Morel P, et al. Influence of donor age on islet isolation and transplantation outcome. Transplantation. 2011;91(3):360‐366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Miki A, Ricordi C, Messinger S, et al. Toward improving human islet isolation from younger donors: rescue purification is efficient for trapped islets. Cell Transplant. 2009;18(1):13‐22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wang Y, Danielson KK, Ropski A, et al. Systematic analysis of donor and isolation factor’s impact on human islet yield and size distribution. Cell Transplant. 2013;22(12):2323‐2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sakuma Y, Ricordi C, Miki A, et al. Factors that affect human islet isolation. Transplant Proc. 2008;40(2):343‐345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hanley SC, Paraskevas S, Rosenberg L. Donor and isolation variables predicting human islet isolation success. Transplantation. 2008;85(7):950‐955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ponte GM, Pileggi A, Messinger S, et al. Toward maximizing the success rates of human islet isolation: influence of donor and isolation factors. Cell Transplant. 2007;16(6):595‐607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kim SC, Han DJ, Kang CH, et al. Analysis on donor and isolation‐related factors of successful isolation of human islet of Langerhans from human cadaveric donors. Transplant Proc. 2005;37(8):3402‐3403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Balamurugan AN, Naziruddin B, Lockridge A, et al. Islet product characteristics and factors related to successful human islet transplantation from the collaborative islet transplant registry (CITR) 1999–2010. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(11):2595‐2606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. O’Gorman D, Kin T, Murdoch T, et al. The standardization of pancreatic donors for islet isolations. Transplantation. 2005;80(6):801‐806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lakey JR, Warnock GL, Rajotte RV, et al. Variables in organ donors that affect the recovery of human islets of Langerhans. Transplantation. 1996;61(7):1047‐1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kaddis JS, Danobeitia JS, Niland JC, Stiller T, Fernandez LA. Multicenter analysis of novel and established variables associated with successful human islet isolation outcomes. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(3):646‐656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Toso C, Oberholzer J, Ris F, et al. Factors affecting human islet of Langerhans isolation yields. Transplant Proc. 2002;34(3):826‐827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wells M, Croome K, Janik T, Hernandez‐Alejandro R, Chandok N. Comparing outcomes of donation after cardiac death versus donation after brain death in liver transplant recipients with hepatitis C: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;28(2):103‐108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Brandhorst D, Iken M, Bretzel RG, Brandhorst H. Pancreas storage in oxygenated perfluorodecalin does not restore post‐transplant function of isolated pig islets pre‐damaged by warm ischemia. Xenotransplantation. 2006;13(5):465‐470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Matsumoto S, Yamada Y, Okitsu T, et al. Simple evaluation of engraftment by secretory unit of islet transplant objects for living donor and cadaveric donor fresh or cultured islet transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2005;37(8):3435‐3437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Matsumoto S, Okitsu T, Iwanaga Y, et al. Successful islet transplantation from nonheartbeating donor pancreata using modified Ricordi islet isolation method. Transplantation. 2006;82(4):460‐465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Matsumoto S, Tanaka K. Pancreatic islet cell transplantation using non‐heart‐beating donors (NHBDs). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2005;12(3):227‐230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Saito Y, Goto M, Maya K, et al. Brain death in combination with warm ischemic stress during isolation procedures induces the expression of crucial inflammatory mediators in the isolated islets. Cell Transplant. 2010;19(6):775‐782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Contreras JL, Eckstein C, Smyth CA, et al. Brain death significantly reduces isolated pancreatic islet yields and functionality in vitro and in vivo after transplantation in rats. Diabetes. 2003;52(12):2935‐2942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Saito T, Gotoh M, Satomi S, et al. Islet transplantation using donors after cardiac death: report of the Japan Islet Transplantation Registry. Transplantation. 2010;90(7):740‐747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Berney T, Boffa C, Augustine T, et al. Utilization of organs from donors after circulatory death for vascularized pancreas and islet of Langerhans transplantation: recommendations from an expert group. Transpl Int. 2016;29(7):798‐806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Munksgaard B, Bernat JL, D’Alessandro AM, et al. Report of a national conference on donation after cardiac death. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(2):281‐291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nano R, Clissi B, Melzi R, et al. Islet isolation for allotransplantation: variables associated with successful islet yield and graft function. Diabetologia. 2005;48:906‐912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rheinheimer J, Ziegelmann PK, Carlessi R, et al. Different digestion enzymes used for human pancreatic islet isolation: a mixed treatment comparison (MTC) meta‐analysis. Islets. 2014;6(4):e977118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Misawa R, Ricordi C, Miki A, et al. Evaluation of viable β‐cell mass is useful for selecting collagenase for human islet isolation: comparison of collagenase NB1 and liberase HI. Cell Transplant. 2012;21(1):39‐47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Shimoda M, Noguchi H, Naziruddin B, et al. Assessment of human islet isolation with four different collagenases. Transplant Proc. 2010;42(6):2049‐2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. McCarthy RC, Breite AG, Green ML, Dwulet FE. Tissue dissociation enzymes for isolating human islets for transplantation: factors to consider in setting enzyme acceptance criteria. Transplantation. 2011;91(2):137‐145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lakey JRT, Burridge PW, Shapiro AMJ. Technical aspects of islet preparation and transplantation. Transpl Int. 2003;16(9):613‐632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Lehmann R, Zuellig RA, Kugelmeier P, et al. Superiority of small islets in human islet transplantation. Diabetes. 2007;56(3):594‐603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Warnock GL, Meloche RM, Thompson D, et al. Improved human pancreatic islet isolation for a prospective cohort study of islet transplantation vs best medical therapy in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Arch Surg. 2005;140(8):735‐744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Caballero‐Corbalán J, Brandhorst H, Malm H, et al. Using HTK for prolonged pancreas preservation prior to human islet isolation. J Surg Res. 2012;175(1):163‐168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kinasiewicz A, Fiedor P. Amylase levels in preservation solutions as a marker of exocrine tissue injury and as a prognostic factor for pancreatic islet isolation. Transplant Proc. 2003;35(6):2345‐2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Squifflet JP, Ledinh H, De Roover A, Meurisse M. Pancreas preservation for pancreas and islet transplantation: a minireview. Transplant Proc. 2011;43(9):3398‐3401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Noguchi H, Levy MF, Kobayashi N, Matsumoto S. Pancreas preservation by the two‐layer method: does it have a beneficial effect compared with simple preservation in university of wisconsin solution? Cell Transplant. 2009;18(5–6):497‐503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Brandhorst H, Brandhorst D, Hering BJ, Federlin K, Bretzel RG. Body mass index of pancreatic donors: a decisive factor for human islet isolation. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 1995;103(Suppl):23‐26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Matsumoto I, Sawada T, Nakano M, et al. Improvement in islet yield from obese donors for human islet transplants. Transplantation. 2004;78(6):880‐885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Oniscu GC, Randle LV, Muiesan P, et al. In situ normothermic regional perfusion for controlled donation after circulatory death ‐ the United Kingdom experience. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(12):2846‐2854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Wang L‐J, Kin T, O'gorman D, et al. A multicenter study: North American islet donor score in donor pancreas selection for human islet isolation for transplantation. Cell Transplant. 2016;25(8):1‐30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request from the authors.