Abstract

To quickly and drastically reduce CO2 emissions and meet our ambitions of a circular future, we need to develop carbon capture and storage (CCS) and carbon capture and utilization (CCU) to deal with the CO2 that we produce. While we have many alternatives to replace fossil feedstocks for energy generation, for materials such as plastics we need carbon. The ultimate circular carbon feedstock would be CO2. A promising route is the electrochemical reduction of CO2 to formic acid derivatives that can subsequently be converted into oxalic acid. Oxalic acid is a potential new platform chemical for material production as useful monomers such as glycolic acid can be derived from it. This work is part of the European Horizon 2020 project “Ocean” in which all these steps are developed. This Review aims to highlight new developments in oxalic acid production processes with a focus on CO2‐based routes. All available processes are critically assessed and compared on criteria including overall process efficiency and triple bottom line sustainability.

Keywords: carbon capture and utilization, catalysis, CO2 conversion, formate coupling, oxalic acid

Green oxalic acid: Oxalic acid is a potential new sustainable platform chemical in a value tree to produce ingredients for the cosmetics, polymer, and pharmaceutical industry. It fits in a circular future as it can be produced from many streams of renewable sustainable feedstocks. In this Review, past, present, and future feedstocks for oxalic acid are compared and critically assessed with a focus on CO2‐based routes in carbon capture and utilization (CCU).

1. Introduction

Climate change, plastic pollution, and the loss of biodiversity are highly debated all over the planet ranging from denial to calls for system change, a green new deal, or even rebellion.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ] Science shows that the global climate is changing and that anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, mainly CO2, are largely to blame. [5] As shown in Figure 1, still billions of tons of CO2 are dumped into the environment every year with the number on the rise. In 2019, 940 million tons more CO2 was emitted compared to the 42.14 Gt emitted in 2018, because fossil feedstocks still primarily fuel our lifestyle and economy. Even the effects of the global pandemic could reduce the CO2 emissions in 2020 only down to 2017 levels.[ 6 , 7 ]

Figure 1.

Annual CO2 emissions caused by the release of fossil carbon and land‐use change and development of global mean atmospheric CO2 level.[ 6 , 7 ]

Consequently, we need to turn the ship around quickly and drastically reduce emissions. One way to do this is through carbon capture and storage (CCS) and carbon capture and utilization (CCU).[ 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ] While we have many non‐carbon alternatives to replace fossil feedstocks for energy generation, for materials such as plastics we need carbon. Next to biomass and waste, CO2 is the only other carbon feedstock we have available. [13] Using CO2 as a feedstock will be a requirement for meeting our ambitions of a circular future and staying within the planetary boundaries.[ 10 , 11 , 14 , 15 , 16 ]

Today, the chemical industry is still a big CO2 emitter and lacks circularity as fossil‐based feedstocks dominate. [17] However, the industry can also make use of CO2 as a feedstock and therefore will be a key player in the energy and material transition and has the potential to change from a non‐circular CO2‐emitting industry to a circular industry providing a possible net carbon sink.[ 9 , 12 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 ]

CO2 can replace fossil feedstock in certain chemical processes and has the added advantage of being a low‐cost or (with taxes) a potential negative‐cost carbon source. [22] Converting CO2,however, is not easy due to its high thermodynamic stability.[ 23 , 24 , 25 ] To drive the conversions of CO2 to valuable products it requires high temperatures in chemo catalytic processes or high cell potentials in electro catalytic processes.[ 29 , 30 , 31 ] Today there is serious interest in CO2 conversion technologies, with research mainly focused on the first step, the CO2 reduction.However, we also require fully integrated downstream processes for a successful implementation of CO2 as a feedstock.[ 26 , 27 ] To create circular materials, systemic changes will be required not only in the used feedstock but also in the design of products. [19] Consequently, different or new chemical processes will be required for which a robust life‐cycle assessment will result in a significantly improved carbon footprint.[ 9 , 13 , 27 ]

The electrochemical fixation of CO2 as formate is an interesting first step for CO2 utilization. A full process starting with CO2 to formate was developed at Liquid Light, a spin‐off of Princeton University, which received broad scientific, commercial, and public interest.[ 28 , 29 ] Liquid Light, now part of Avantium, has successfully developed the gas‐diffusion electrode‐driven formate production from CO2.[ 30 , 31 , 32 ] These electrodes are technology leaders due to the stability, scale, and performance of this CO2 conversion. [33] The formate produced in the electrochemical cells is further “upcycled” to oxalate using a process called formate coupling, where two formate molecules combine to oxalate with the release of hydrogen.[ 34 , 35 ] Finally oxalate is acidified (e. g., in a multi‐compartment electrochemical ion exchange cell), resulting in oxalic acid. Today, this technology is further developed in the public‐private European Committee‐sponsored partnership program OCEAN and implemented in different demonstration plants, which will be operational during 2021. [36] The business‐case developed in this program suggests a production cost for formate of about €1000 ton−1 at currently achieved process costs (Cell cost €5000 m−2; current density 2000 A m−2; faradaic yield >90 %), a CO2 price of €50 ton−1 for capture and purification and electricity prices of €30–50 MWh−1. We project the production cost of formate to drop to €300–400 ton−1 beyond 2030 with lower or negative CO2 cost, a reduced electricity price, a reduction in cell cost, and improved current densities. This would make oxalic acid from formate an interesting competing feedstock for producing glycolic acid, glyoxylic acid, and even mono‐ethylene glycol (MEG).

1.1. Oxalic acid and its valuable derivatives

Oxalic acid, the simplest of the dicarboxylic acids, is one of the oldest known acids, discovered by Scheele in 1734. [37] Today it is used in various industries. The largest consumer is the pharmaceutical industry, while others include agriculture, textiles and leather, and the chemical industries.[ 38 , 39 , 40 ] It is also widely used as an acid rinse in laundries, where it is effective in removing rust and ink stains as it converts most insoluble iron compounds into a soluble complex ion. [41] Similarly, oxalic acid is a well‐known leaching agent for solubilizing heavy metals in bauxite, clay, and sewage sludge or bio‐metallurgy for electronic waste. [42] As oxalic acid is naturally present in many vegetable food products it may also be used as a natural anti‐browning and preservation agent in fruit and vegetable storage and can replace currently used inorganic acids. [43]

The oxalic acid market today is 350 000 t yr−1, but in the future, oxalic acid can be the origin of a wide range of high‐value and high‐volume chemicals. Two examples are formic acid/formate with a market of 900 000 t yr−1 or MEG with 30 000 000 t yr−1. Of course, we can produce these chemicals from different resources, but if we want to avoid using fossil feedstock by 2050, the only alternative carbon sources are biomass and CO2.[ 44 , 45 ] It has the potential to be a major platform for carbon‐containing materials such as new classes of polymers. [46] This does not only include products derived directly from oxalic acid but also the oxalic acid‐based C2 compounds shown in Figure 2. We work on various processes to obtain these building blocks from oxalic acid and on several classes of oxalic acid‐ and glycolic acid‐based polyesters.[ 36 , 46 , 47 ]

Figure 2.

Value tree: Oxalic acid as starting compound for a variety of high‐value products.

Glyoxylic acid is the first reduction product of oxalic acid. It is an important C2 building block for many organic molecules of industrial importance, used in the production of agrochemicals, aromas, cosmetic ingredients, pharmaceutical intermediates, and polymers.[ 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 ] Glyoxylic acid finds direct application in personal care as neutralizing agent; it is widely used in hair straightening products in particular (shampoos, conditioners, lotions, creams) at levels of 0.5–10 %.

If the aldehyde function of glyoxylic acid is further reduced, glycolic acid is obtained. Glycolic acid is a useful intermediate for organic synthesis, in a range of reactions including oxidation‐reduction, esterification, and long‐chain polymerization. It is used as a monomer in the preparation of polyglycolic acid and other biocompatible copolymers such as poly lactic‐co‐glycolic acid (PLGA.)[ 47 , 52 ] Glycolic acid is directly used in the textile industry as a dyeing and tanning agent, in food processing as a flavoring agent, and as a preservative. In the pharmaceutical industry, it is used as a skin care agent, and it is also used in adhesives and polymers.[ 53 , 54 , 55 ] Glycolic acid is often included in emulsion polymers, solvents, and additives for ink and paint to improve flow properties and impart gloss. [56]

From a commercial perspective, important derivatives of glycolic acid include the methyl and ethyl esters, which are readily distillable, unlike the parent acid. The butyl ester is a component of some varnishes, being desirable because it is nonvolatile and has good dissolving properties.

At the same reduction level is glyoxal. Due to its bifunctionality, it finds a wide range of applications. It is used as a cross‐linker for condensation reactions with starch, cellulose, keratin, casein, animal glue, and mineral‐based building materials. In organic synthesis, it is used to create heterocycles such as imidazole. In polymer chemistry, glyoxal is used as a solubilizing agent and cross‐linking agent. [57] It is used directly in the cosmetic, textile, paper, and leather industry. In the oil industry, it is utilized as a sulfur‐capturing agent.

Glycolaldehyde is the smallest sugar molecule and an interesting platform chemical itself. [58] It is used today in the polymer industry to create polymers with free hydroxy groups and in the production of furans. [59]

Lastly, there is MEG. One of the uses of ethylene glycol is as heating or cooling fluid with a broad range of applications. The largest use is in the polymer industry: ethylene glycol is an important monomer for polyethylene terephthalate (PET) polyester for fibers, bottles, and films. Because of its high boiling point and affinity for water, ethylene glycol is also a useful desiccant.

In addition to their current uses, all five C2 compounds above are of increasing interest for the manufacture of new, high‐performance polymers. Glyoxylic acid esters can be polymerized with bases to obtain biodegradable polymers with chelating properties.[ 60 , 61 ] Many monomers for sustainable polymers can be derived from it, linking the consumption of CO2 with the production of circular, potential long‐term carbon storage in materials. [62] A detailed account from our group on polyesters from oxalic acid and glycolic acid was published recently by Murcia Valderrama et al. [46]

These new solutions are required to satisfy the growing demand for polymers in the world with sustainable alternatives by replacing their petrochemical counterparts. The CO2 volume potential in polymer applications will be very dependent on the economics of these monomers and the performance of the resulting polymer materials. In our group, we have shown very promising results towards meeting both these criteria. [63] Overall, we hope to show in this Review and in the years to come that oxalic acid has great potential the future because of its large potential applications in the polymer market.

In this Review, we discuss the popular pathway for CO2 to oxalic acid developed by Liquid Light in detail and compare it to other production processes utilizing non‐fossil carbon (CO2 and biomass). We discuss each of the six main paths that we identified and highlight the upstream processes required for feedstock generation. To compare and assess the various possible pathways based on their sustainability and circularity, we use the concept of circular chemistry as a framework. This furthermore helps to identify optimization potential for resource efficiency across chemical value chains and enables a closed‐loop, waste‐free chemical industry, replacing today's linear “take‐make‐dispose” approach with circular processes. [19] Therefore, new processes should fit within the guiding principles of this framework.

2. Routes and Feedstocks to Oxalic Acid

Oxalic acid can be produced via six main routes as shown in Figure 3. The feedstocks, which include CO2, CO, alkali formate (AF), ethylene glycol (EG), propylene, and carbohydrate‐rich biomass, can be derived from three main sources: biomass, CO2, and fossil carbon deposits. Some of these processes are commercially used whilst others are new developments. To improve their sustainability, we can either substitute fossil‐based building blocks by renewable ones or develop new sustainable routes towards oxalic acid. Oxalic acid is commercially produced today from carbohydrates, ethylene glycol, propylene, CO, and ethanol as well as alkali formates.

Figure 3.

Overall there are six feedstocks directly used for oxalic acid‐producing processes. These feedstocks include (1) CO2, (2) CO, (3) alkali formate, (4) ethylene glycol, (5) propylene, and (6) carbohydrates. Except for CO2, a commercially used route exists for all of those feedstocks.

The oldest route towards oxalic acid was discovered by Bergmann in 1776. It requires the use of nitric acid to oxidize biomass, or more precisely the contained carbohydrates, into oxalic acid. [37] Biomass describes plant matter that originates from the photosynthetic conversion of CO2 into sugars and other organic building blocks. [64] One of the main concerns for large‐scale implementation of biomass as a feedstock for the chemical industry is its competition with food production when crops are used that are grown on farmland or are otherwise food themselves, such as corn or wheat. [65]

Although there is no competition with food today (due to the very small bio‐based polymer volumes), it is important to develop so‐called second‐ or third‐generation biomass sources, which avoid this problem for future large‐scale applications. [66] Scheme 1 shows all pathways that use biomass as feedstock. Besides nitric acid oxidation, biomass can be directly converted to oxalic acid by a process called alkali heating and fermentation.[ 43 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 97 , 98 , 99 , 100 ] Furthermore, biomass can also be used as a feedstock for the production of other oxalic acid precursors such as CO (gasification), CO2 (fermentation or combustion), AF, and EG (via bio‐ethylene or direct hydrogenolysis).[ 101 , 102 ]

Scheme 1.

Biomass can be (a) directly converted into oxalic acid by oxidation or used as a feedstock for oxalic acid precursors including (b) propylene, (c) ethanol and CO2, (d) CO, and (e) glucose. CO can be converted into oxalic acid (f) directly or (g) via the formation of formate. Glucose can be (h) oxidized directly or (i) first converted to ethylene glycol, which is subsequently oxidized.

Today the chemical sector is the largest industrial consumer of both oil and gas, accounting for 15 % of oil and 9 % of gas demand. [103] Together with coal, non‐renewable fossil resources provide 87–96 % of organic chemicals today, and oxalic acid is no exception.[ 103 , 104 , 105 ] Currently, the majority of oxalic acid is produced from fossil naphtha via propylene and ethylene glycol or CO, which is mainly obtained from coal.[ 106 , 107 ] Additionally, AF can be derived from fossil‐based CO too.[ 108 , 109 , 110 , 111 , 112 , 113 , 114 ] Scheme 2 shows all fossil carbon‐based pathways including oxidative pathways via naphtha‐derived ethylene and propylene with harsh oxidants. This synthetic strategy was first reported by Gallently in 1881, who formed oxalic acid by heating paraffin with HNO3. [115]

Scheme 2.

Fossil carbon can be converted to oxalic acid via four pathways: (a) naphtha can be converted to ethylene glycol (via ethylene), which can be oxidized to oxalic acid; (b) propylene is obtained from naphtha cracking and can be converted to oxalic acid; (c) fossil carbon is converted to CO in a gasification process, which can be converted to oxalic acid via the dialkyl oxalate process; and alternatively (d) CO can be converted to formate, which is turned into oxalic acid using formate coupling followed by an acidification step.

The most underestimated chemical feedstock of our times might be CO2. CO2 can be converted to oxalic acid in multiple ways as illustrated in Scheme 3. Two routes proceed via oxalate, which is either produced electrochemically from CO2 directly in non‐aqueous electrolytes or via formate coupling. Formate can be obtained from CO2 using electrochemistry in aqueous media or via CO as a substrate. Oxalate is then electrochemically or traditionally acidified to oxalic acid. In another route, dimethyl oxalate is produced from CO, which can be obtained from CO2 in various ways described in chapter 4.1 below. Dimethyl oxalate is then hydrolyzed to oxalic acid. Ethylene glycol can also be obtained from CO2 and oxidized to oxalic acid.

Scheme 3.

CO2 can be converted to oxalic acid via four main pathways: (a) through direct conversion of CO2 to alkali oxalate; (b) through a metal formate intermediate, which can be obtained from the electrocatalytic or photocatalytic reduction of CO2; (c) via CO and the dialkyl oxalate process; and (d) via ethylene glycol and subsequent oxidation (in practice not done because ethylene glycol would be obtained from oxalic acid, not vice versa).

CO2 is mainly known for the environmental problems it causes, which include climate change and ocean acidification. [116] To become truly circular and mitigate these problems, the utilization of CO2 as a feedstock is required as some CO2‐emitting sources such as cement, steel, or ammonia production cannot be avoided or using a carbon source is strongly preferred even though alternative processes using hydrogen were proposed. For the industry to develop and adopt CO2 as a feedstock, however, it also requires processes (and regulations or taxes) to be competitive in the market to compete with and limit the dependency on fossil fuels.[ 12 , 21 , 117 ] Obtaining it directly from the air using so‐called direct air capture processes is difficult due to the low CO2 concentration (400 ppm in the air) and requires high energy input. [118] Today, high‐purity industrial point sources, such as carbohydrate fermentation to methanol, natural gas processing, hydrogen production from methane, coal/gas‐to‐liquids, steel, and cement production, energy generation, and ammonia production, supply the majority of the CO2 that is injected in CO2 storage demonstration projects. [119] CO2 can be captured relatively cheaply in large‐scale cement or steel factories.[ 120 , 121 ] The publications on CO2 conversion are at an all‐time peak, indicating high scientific interest. [122]

3. Direct Conversion of CO2 to Oxalic Acid

Ideally, we should directly convert CO2 into oxalic acid in one step. CO2 can be obtained directly from the air or point sources. Several reviews on CO2 capture technologies and their implications are available.[ 123 , 124 , 125 , 126 , 127 ] There are many routes for direct reduction of CO2, which can be summarized in three categories as shown in Scheme 4. They include (a) direct classic electrochemical CO2 reduction catalyzed by metals, (b) electrochemical reduction catalyzed by metal complexes, and (c) sacrificial reduction with calcium ascorbate. None of these processes are in the commercial stage yet due to low yields, low turnover numbers, or the high complexity of the systems. For example, former Princeton spin‐off Liquid Light (now Avantium) developed an electrochemical one‐step route to oxalate, but the requirement of a stable nonaqueous electrolyte proved to be a barrier to scale‐up. [128]

Scheme 4.

Direct conversion of CO2 to oxalate followed by acidification to oxalic acid: (a) direct electrochemistry; (b) CO2 reduction catalyzed homogeneously by metal complexes; (c) reduction of CO2 with Ca‐ascorbate and electrochemical regeneration.

3.1. Direct electrochemical CO2 reduction

Electrochemical reduction is a powerful means to activate and convert CO2, but it is also challenging. A comprehensive overview of all aspects of electrochemical reduction of CO2 on metal electrodes is available from Hori. [129] The nature of the formed product crucially depends on the reaction medium and choice of electrode material.

Ikeda et al. proposed that the CO2 reduction reaction proceeds via single‐electron reduction leading to the formation of a CO2 .− radical anion. [130] The formed CO2 .− radical anion is highly reactive and reacts with proton donors such as water to form undesired formate and carbonate following Equation (1). Therefore, the choice of the reaction medium is of great importance.[ 131 , 132 , 133 , 134 ]

| (1) |

This unwanted side reaction can be suppressed when solvents of low proton availability are used. If the CO2 .− anion radical is present long enough on the electrode surface, it reacts with another one, and oxalate is formed as shown in Equation (2). This mechanism has been proven with in‐situ spectroscopy by Eneau‐Innocent et al. [135]

| (2) |

The formation of the CO2 .− radical anion is thermodynamically unfavored due to large reorganizational energy between the linear molecule and bent radical anion. [136] In practice when using dimethylformamide, the uncatalyzed reaction required standard potential is −2.21 V vs. saturated calomel electrode. [137] A large standard potential can lead to large operation potentials, which should be avoided as they reduce the process efficiency. Metal catalysts can lower the standard potential by providing alternative reaction pathways and subsequently allow for a lower overall operation potential of CO2 activation.

Tin, mercury, lead, indium, and tellurium electrodes proved suitable for the reaction in an early stage, and oxalic acid was produced at 90 % faradaic efficiency (FE) in dimethyl formamide.[ 130 , 134 , 138 ] Newer developments include the use of metal oxides such as MoO2 in combination with lead electrodes. [139]

If the radical anion is not staying on the surface it migrates into the electrolyte where it can react with another CO2 to form CO and CO3 2− via reductive disproportionation according to Εquation (3), rather than to oxalate according to Εquation (2). [140] Electrodes made from platinum, palladium, gold, or copper favor this unwanted side reaction.[ 130 , 141 ]

| (3) |

In conclusion, three competing reactions [Eqs. (1–3)] are present during the direct electrochemical reduction of CO2 to oxalic acid. [137] The absence of water is crucial as it does not only favor formate production but also further the reduction of oxalate to glycolate.[ 131 , 132 ] Although it is beneficial to have trace amounts of water present if CO2 is reduced to CO, this is not the case if oxalic acid is desired. [142] Therefore, the absence of water, even in trace amounts, is critical to achieving high FEs. [143] Kaiser and Heitz were the first to develop a suitable process and considered parameters such as electrode materials, solvents, pH, and current densities. [131] Propylene carbonate, acetonitrile, and dimethylformamide were found to be the most suitable solvents due to their relatively low nucleophilicity at a sufficient electrophilic constant. Adding tetraethylammonium perchlorate as a supporting electrolyte was found to increase oxalate production by improving electrochemical contact between CO2 and the working electrode surface. [144] Recently also the reaction temperature was added to the list of important reaction conditions. [145] In some instances, a low reaction temperature as low as −20 °C can be beneficial to help suppress hydrogen evolution from water splitting in wet organic solvents such as acetonitrile and dimethylformamide. [139]

A commercial industrial process called the zinc oxalate process was developed by Heitz and co‐workers. The use of a sacrificial zinc anode forms insoluble zinc oxalate, which can be removed from the electrolyte by simple filtration.[ 146 , 147 ] As a first step, CO2 is reduced to oxalate as in Equation (4); at the same time zinc is oxidized to Zn2+ [Eq. (5)]. Together they form insoluble zinc oxalate [Eq. (6)]. After filtration, the oxalate can be acidified with sulfuric acid, where oxalic acid and zinc sulfoxide are formed following Equation (7). The zinc and sulfuric acid can be recovered by electrolysis in water as in Equation (8). Overall, oxalic acid is obtained from CO2 and water as in Equation (9). [146]

Oxalate electrolysis:

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

Oxalic acid from zinc oxalate:

| (7) |

Zinc electrolysis:

| (8) |

Sum of all reactions:

| (9) |

The overall process requires four cycles as shown in Figure 4. The advantages of the process are high current efficiencies (>90 %) and the absence of unwanted side products and precious metals in the process. Economic calculations lead to the conclusion that the process is price competitive on a 2 million ton scale. A disadvantage is the need for dry organic solvents. Unfortunately, the process has never been tested on the pilot stage as a continuous close‐loop operation.

Figure 4.

Flow sheet of zinc oxalate process as developed by Fischer et al. In the bottom left in the first cycle, CO2 is converted to zinc oxalate and removed by filtration. The oxalate is dissolved in sulfuric acid in the second cycle, and oxalic acid is extracted from the zinc sulfate solution, which is recycled to sulfuric acid and zinc in the zinc electrolysis cell shown at the top. Pure oxalic acid is obtained by evaporation of the extractant in the last step in the bottom right. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [147]. Copyright 1981, Springer.

Most recently Paris and Bocarsly reported a new system operating in aqueous media. [148] It comprises a thin film of alloyed Cr and Ga oxides on glassy carbon, which electrocatalytically generates oxalate from aqueous CO2 with a maximum oxalate FE of 59 % at potentials as positive as −0.98 V vs. normal hydrogen electrode (NHE).

Oxalate is produced at a surface anion site via a CO‐dependent pathway instead of relying on the formation of a CO2 .− radical anion, hence the reduced need for non‐protic environments. However, the catalysts exhibit two sites, which can either favor oxalate or formate formation. To favor oxalate production the crucial parameters such as pH, alloy ratio, and electrolyte cation need to be optimized. A pH of 4.1 with KCl as electrolyte and a Cr2O3/Ga2O3 ratio of 3 : 1 was shown to be most favorable. This process is still in a very early stage and still needs to prove scalability.

3.2. Metal‐complex electrocatalysis

Homogeneous catalysts have a long history in CO2 reduction of over 40 years. However, the primary interest was the formation of syngas or the direct formation of possible fuels. A comprehensive Review on the topic has been published by Benson et al. [136] Some groups also focused on the production of oxalate. Becker et al. were the first to develop homogeneous catalysts specifically for the formation of oxalate. [149] They made use of silver and palladium porphyrins and were able to drop the operation potential from −2 to −1.5 V and found selectivity towards oxalic acid in absence of CO. They did not state any selectivity or efficiency numbers and possible mechanisms.

Kushi et al. had a different approach and made use of a rhodium sulfide cluster in CO2‐saturated CH3CN in the presence of LiBF4 as shown in Figure 5. [152] They could also lower the operation potential to −1.5 V whilst operating at 60 % current efficiency. The cluster was crafted on a glassy carbon plate and did not show any signs of fragmentation. Not only low‐valence metal but also electron‐rich sulfur ligands are the possible sites for the activation of CO2 by metal‐sulfur clusters. Fourier‐transform (FT)IR studies revealed the presence of CO2 bonded to the reduced clusters at either two Rh or a S and Rh site.

Figure 5.

Structure of the triangular rhodium complex [(RhCp*)3(μ3‐S)2]2. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [152]. Copyright 1994, The Chemical Society of Japan.

In a subsequent study, they could show even better activity using iridium and cobalt complexes with which the operation potentials could be lowered to −1.3 and −0.7 V, respectively, whilst maintaining 60 % current efficiency. This resembles a strong decrease of the overpotential of 1.4 V compared to the uncatalyzed reaction. [150]

Evans et al. were up next and demonstrated the use of lanthanides, in this case samarium, as a suitable catalyst to reach high selectivity of oxalic acid in appropriate conditions. [151]

In 2010 Bouwman and co‐workers first described a dinuclear copper(I) complex that is oxidized by CO2 rather than by O2 when brought into contact with air. [153] The CO2 is captured and a tetranuclear oxalate‐bridged copper(II) complex is formed as shown on the bottom left of Figure 6. The captured oxalate can be then liberated as oxalic acid by the addition of hydrochloric acid.

Figure 6.

Catalytic cycle of copper complex for CO2 activation as proposed by Bouwman and co‐workers. The initial copper(II) complex [4]4+ is first reduced at −0.03 V vs. NHE to the copper(I) complex [1]2+. This is subsequently reduced by two CO2 to copper (ii) again. Two of the complexes merge and the bound CO2 .− radical anions couple to form bridging oxalate molecules [2]4+. Lithium ions and acetonitrile liberate the oxalate as lithium oxalate and the initial complex is formed again. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [153]. Copyright 2010, American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Alternatively, the authors developed a system in which lithium perchlorate is used as a supporting electrolyte and acetonitrile as solvent. This system allows for a full catalytic cycle as shown in Figure 6. First the copper(II) complex [4]4+ is reduced to the copper(I) complex [1]2+, which is then oxidized by two CO2 .− molecules, which are bound as CO2 .− radical anions. Two of the complex pairs form the oxalate‐bridged tetranuclear copper(II) complex [2]4+. The complexed oxalate then is liberated by the lithium ions as lithium oxide and acetonitrile refills the vacant coordination spaces of the complex.

Preliminary results demonstrate six turnovers (producing 12 equiv. of oxalate) during 7 h of catalysis at an applied potential of −0.03 V vs. NHE. However, no yields or selectivity were reported, and the coverage of the electrode with precipitated oxalate leads to deactivation as it hampers efficient electron transfer.

In 2014, Maverick and co‐workers presented a copper complex for CO2 transformation to oxalate but have retracted that article recently.[ 154 , 155 ]

They had initially introduced ascorbic acid as mild reducing agent, which has been long known to decompose to oxalates in the presence of transition metals and oxygen. Now they identified the reducing agent as the source of oxalate rather than the reduction of CO2. The reduced CuI complex does react with CO2 but forms a stable carbonate complex instead (Figure 7)

Figure 7.

Revised version of the original three‐step reaction cycle for reduction of CO2 to oxalic acid. The starting CuII complex (1 or 2) is reduced to a CuI complex by sodium ascorbate (3). In the presence of oxygen, the ascorbate is reduced to oxalate to give oxalate‐bridged complex (4). In the presence of CO2 and absence of ascorbate, however, a stable three‐valent carbonate complex is formed. Reproduced with permission form Ref. [155]. Copyright 2021, Nature Publishing Group.

Kumar et al. used a different approach for the special organization of their catalyst and designed a copper‐based metal‐organic framework (MOF). [156] They could decrease the overpotential by 0.7 V and increase the current density from 2.27 to 19.22 mA cm−2 in DMF solution and Tetrabutylammonium tetrafluoroborate (TBATFB) as supporting electrolyte. They proposed the formation of the CO2 .− radical anion, which couples to oxalate and then abstracts a proton from the solvent to form oxalic acid with 90 % selectivity at 51 % FE.

The advantages of transition metal complex systems are their high selectivity and the use of non‐precious metals in some examples. However, the low FE, long reaction times, and use of toxic solvents are major drawbacks. In addition, the process development suffers from highly complex systems and is hence at an early stage of development on a lab scale. The recent retractions emphasize the challenges and complexity of these systems further.

3.3. Sacrificial reduction using Ca‐ascorbate

The work of Pastero et al. shows that also pathways without harmful reagents, complicated metal complexes, or electrochemical cells are available. [157] They made use of the oxidizing potential of the calcium salt of ascorbic acid (AA), more widely known as Vitamin C. They claim that AA is not only nontoxic but also cost‐effective as a reducing agent, citing its earlier applications in the biomedical and food industry.

AA is unstable in solution and decomposes to dehydroascorbic acid as shown in Equation (10) with a redox potential of 0.5 V vs. NHE. [158]

| (10) |

In their experiments, stoichiometric amounts of calcium AA salt react with the CO2 to form insoluble calcium oxalate in the form of Weddellite‐type crystals. The reaction rate was found to be depending on pH, temperature, and reactor design but optimal conditions were not presented. Advantages of this process are the simple equipment and absence of precious metal catalysts. However, the stoichiometric consumption of AA is a major drawback as AA requires a complicated multistep production process and therefore has a much higher market price than the product oxalic acid. [159] Additionally the sacrificial CO2 process is yet to be tested on a larger scale.

4. Carbon Monoxide to Oxalic Acid

Carbon monoxide can be used as a feedstock for oxalic acid in various ways. It is mainly used indirectly to produce feedstock for oxalic acid production, but the direct pathway is also possible via the dialkyl oxalate as shown in Scheme 5.[ 160 , 161 ]

Scheme 5.

CO can be converted to oxalic acid via the dialkyl oxalate process, where first the dialkyl ester of oxalic acid is formed, which is then hydrolyzed to oxalic acid.

4.1. Carbon monoxide production

Carbon monoxide is a toxic gas generated mainly by the incomplete combustion of carbon compounds. [162] It was first isolated in 1776 by de Lassone and is increasingly used as feedstock on a very large scale in the chemical industry, as a pure reactant for the production of hydrogen (water‐gas shift reaction), inorganic chemicals, and acetic, acrylic, or propanoic acid in the Cativa process. [163] In conjunction with hydrogen, it is called syngas and used for the production of alcohols, hydrocarbons, or linear aliphatic aldehydes using the process. [164]

All production pathways of CO are illustrated in Scheme 6, including those from the most common source in commercial quantities, which is still fossil carbon. [162] This includes the gasification of coal, steam reforming, the Boudouard reaction, and the partial oxidation of hydrocarbons. [162] Alternatively, CO can be obtained from the thermal treatment of biomass or CO2. CO can be produced from CO2 using heterogeneously catalyzed reverse water‐gas shift reaction, electrochemically, or photochemically.[ 165 , 166 , 167 , 168 ]

Scheme 6.

CO can be obtained from fossil carbon, biomass, and CO2. Fossil routes include (a) Boudouard reaction, (b) steam reforming of gas, and (c) partial oxidation of hydrocarbons. Biomass can be (d) thermochemically converted and CO2 can be reduced to CO via (e) reverse water‐gas‐shift reactions, (f) direct electrochemical reduction, or (g) electrolysis.

4.1.1. Fossil carbon conversion

The major industrial process for the production of CO is the Boudouard reaction in which CO2 from fossil carbon combustion [Eq. (11)] reacts with carbon [Eq. (12)]. Above 800 °C, CO is the predominant product:

| (11) |

| (12) |

Through this reaction, CO2 from a variety of combustion plants can be upgraded to CO, but the process is energy intensive. [169] In the gasification of coal, both CO and hydrogen are formed [Eq. (13)], which requires separation.

| (13) |

The steam‐reforming process, discovered by Fontana in 1780, only uses water and no additional oxygen as in Equation (13). This leads to a higher proportion of hydrogen in the mix:

| (14) |

In partial oxidation, CO is produced from natural gas or heavy hydrocarbons and a limited amount of oxygen to form CO and hydrogen [Eq. 15].

| (15) |

The advantage of these processes is that they are all technically mature and have been used commercially for many decades. However, to be sustainable the fossil feedstock has to be replaced with a sustainable carbon source. A further disadvantage is that these processes all produce gas mixtures, which should be separated in various processes by reversible complexation, cryogenic separation, pressure swing adsorption, or permeable membranes. All of these require extensive equipment and significant energy. Alternatively, CO can be produced from biomass or CO2, which will be described in the next section.

4.1.2. Thermal biomass conversion

The production of CO from biomass is possible from various sources, but algae are especially suitable due to their simple cell structure and composition.[ 170 , 171 , 172 ] All routes in principle are thermochemical conversion of the biomass in the form of either pyrolysis, gasification, or direct combustion. [171] Those routes are described and discussed by Lam et al. [172] The resulting gas mixture requires gas separation similar to fossil processes.

4.1.3. Reverse water‐gas shift

The reverse water‐gas shift reaction was first discovered by Bosch and Wild in 1913 and is commercially used for methanol synthesis and syngas processes.[ 173 , 174 ] It is equilibrium limited and favored at high temperatures as it is endothermic [Eq. 16].

| (16) |

For the hydrogen route to be sustainable, the hydrogen must be produced via electrochemical water splitting. [175] The reaction is usually carried out in simple single‐stage adiabatic reactors with the help of supported metal catalysts of which iron‐ and copper‐based catalysts are most common.[ 166 , 176 , 177 , 178 , 179 ] An in‐depth introduction on the reaction, reactor, and catalyst design was published by Newsome. [179] Daza and Kuhn discussed the recent developments in catalysts and mechanisms and their consequences on economics in great detail in their 2016 Review. [165] This path of CO production has the advantage of scalability, high selectivity towards CO, and a simple process design. However, catalysts that are highly selective at high production rates are yet to be found. [165]

4.1.4. Electrochemical reduction of CO2

The electrocatalytic CO2 reduction reaction as in Equation (17) is considered one of the most attractive methods of storing intermittent renewable energy as chemical energy on a large scale. [24]

| (17) |

Although a vast variety of products are accessible through the electrocatalytic CO2 conversion pathways, only CO and formic acid/formate (pK a=3.77) are produced at high FEs (above 80 %) and current densities above 100 mA cm−2 for hundreds of hours.[ 180 , 181 ] The formation of CO2 proceeds via the formation of a CO2 .− anion radical as described above. The choice of a protic solvent favors the production of CO over oxalate. The choice of the metal determines whether formate or CO is formed. [129] A recent review from Nielsen et al. [182] provides a good overview of the electrochemical CO2 reduction process, and several other authors discuss various aspects in great detail.[ 116 , 165 , 167 , 175 , 180 , 183 , 184 , 185 , 186 , 187 ] Hernández et al. and Chen et al. discussed the options in a broader scope, evaluated the state of the art results, and came to the conclusion that whilst the development of the direct electrochemical processes has progressed significantly, they still have challenging obstacles to overcome before becoming industrially viable.[ 183 , 184 ] Overall, the advantage of these processes is the use of gaseous CO2 and renewable energy as a feedstock. Due to fluctuations in the availability of renewable energy, the short start‐up time of these systems may be an advantage. Disadvantages are the use of precious metals as catalysts and complex electrode designs, which make long‐term stability, production rate optimization, and upscaling challenging. Large‐scale demonstrators yet need to show the viability of this process.

4.1.5. Photochemical CO2 reduction

The production of CO from CO2 using photochemical cells is similar to the photochemical production of formate as described below and discussed in recent Reviews by Das and Daud and Saravanan and co‐workers.[ 188 , 189 ]

The advantage here is the direct harvesting of sunlight and the ambient reaction conditions at which the reaction takes place. However, complex reaction systems and difficult reactor design pose challenges for commercialization. Hence, existing techniques are yet insufficient for industrial application and further research into solar‐driven photocatalysts is required. [188]

4.1.6. High‐temperature conversion

At high temperatures, CO2 can be converted to CO and oxygen as in Equation (18). The reaction can be either performed as electrolysis using solid oxide electrolyzer cells or purely thermochemically at 900 °C on metal oxides as catalysts with high oxygen mobility.[ 167 , 190 , 191 , 192 , 193 ]

| (18) |

The advantage of this process is that only CO2 is needed as a reactant, but the major drawback is the high temperature, which requires special equipment and high heat input, still with rather slow reaction rates. Commercial systems for solid oxide electrolysis are already available. [194]

4.2. CO to oxalic acid: the dialkyl oxalate process

In 1974 Fenton et al. were the first to describe the liquid‐phase synthesis of dialkyl oxalate by oxidative carbonization of CO with ethanol and O2 in the presence of a PdCl2‐CuCl2 catalyst in the liquid phase. [161]

The first step is the oxidative CO coupling reaction with aliphatic alcohol under the influence of a palladium catalyst to produce the oxalate diester [Eqs. (19–22]. [161]

| (19) |

| (20) |

| (21) |

| (22) |

The prepared dialkyl oxalate is hydrolyzed to oxalic acid and the corresponding alcohol [Eq. 23].

| (23) |

This method requires a large amount of dehydrating agent to remove water, which is formed in this reaction step and acts as an inhibitor. [161]

UBE Industries (Japan) patented a two‐step process to prepare dialkyl oxalate in 1974. [113] This step was taken after improving the reaction by the introduction of alkyl nitrates as re‐oxidizing agents for the palladium catalysts supported on carbon. Improvements include increased reaction efficiency and catalyst lifetime whilst operating at lower temperatures. [195] An added advantage is the role of a dehydrating agent of the alkyl nitrates. [109] The most beneficial nitrate was found to be n‐butyl nitrate. [110] Further studies have elucidated the role of the catalyst support and ideal catalyst compositions for the reaction.[ 112 , 196 ] The process as shown in Figure 8 is used since 1978 to produce oxalic acid as a starting material to produce fine chemicals. [197]

Figure 8.

Flow diagram of UBE liquid phase process for oxalic acid production in (CO2Bu)2. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [195]. Copyright 1999, Elsevier.

The process, which is well described in vast detail in the Review by Uchiumi et al., has the advantage of high selectivity, mild reaction conditions, efficient utilization of raw material, and high product quality. [195]

5. Formate/Formic Acid to Oxalic Acid

The production of oxalic acid via the formate coupling route (Scheme 7) is one of the oldest processes and has been one of the primary ways to produce oxalic acid before the advent of petrochemistry.[ 160 , 198 , 199 ]

Scheme 7.

Alkali formates can be converted to oxalic acid via formate coupling to oxalate and subsequent acidification to oxalic acid.

5.1. Production of formate

Formate can be produced either directly from CO2 or CO, the latter of which allows to tap into a broad variety of feedstocks as described above. All routes are shown in Scheme 8 and include the commercial route from CO and hydroxides, hydrogenation of carbonates, and direct electrocatalytic, photochemical, or enzymatic reduction of CO2.

Scheme 8.

Alkali formates can be obtained directly or indirectly from CO2. The two indirect ways include (a) CO reduction with caustics and (b) hydrogenation of carbonates. The direct conversion of CO2 can be either (c) electrochemical, (d) photochemical reduction, or (e) enzymatic conversion.

5.1.1. Formate from CO and caustic alkali

Today's commercial route to formate as shown in Equation (24) uses CO and caustic alkalis such as potassium hydroxide. This was first discovered by Berthelot in 1856 and first turned into a commercially viable process by Weise et al.[ 200 , 201 ]

| (24) |

CO and the caustic alkalis react in an aqueous solution to yield the corresponding formates. In today's commercial plants, the CO is mixed counter‐currently with aqueous alkali hydroxide in a tower reactor at 1.5–1.8 MPa and 180 °C, leading to the formation of alkali formate. The process is beneficial if surplus hydroxide can be used for the process. [202]

5.1.2. Carbonate hydrogenation

An alternative route to formate is the catalytic transformation of CO2, which can be achieved by hydrogenation of bicarbonate in an alkaline environment [Eq. 25]. [203]

| (25) |

Carbonate or bicarbonate can be obtained from the reaction of CO2 with alkaline minerals by in‐situ or ex‐situ mineral carbonation with alkaline metals. This reaction also gained interest as a means for CCS as mineral carbonates such as CaCO3 or MgCO3 are the thermodynamically most stable form of carbon. [204] Alternatively, Yu et al. reported the biomimetic enzymatic conversion of CO2 to bicarbonate over functionalized mesoporous silica. [205]

The first synthesis of formates by hydrogenation of in‐situ formed carbonates was reported in 1914 by Bredig and Carter, using palladium supported on carbon under relatively mild conditions at 70–95 °C, 30–60 bar of H2, and 0–30 bar of CO2. [206] Since the work focused on avoiding the use of expensive metals as catalysts to decrease the cost of the process, the influence of process conditions and various new metallic catalysts was tested.[ 203 , 207 , 208 , 209 ] Nickel‐containing catalysts appear to be the most effective among those tested, giving 77 % formate yield. [203] Zhao et al. introduced a catalytic process in which CO2 hydrogenation to formate is carried out in the presence of transition metal‐free homogeneous catalyst. [209]

To use this process sustainably, the hydrogen has to come from water splitting. [175] Alternatively, reducing agents or biomass‐derived alcohol, polyol, or sugars including isopropanol, glycerol, or glucose can be used as hydride donors. [210]

The use of reducing agents is described in a 2016 patent as a one‐pot metal‐catalyzed process. [208] Carbonate salts react in a polar solvent such as water or ethanol at 50–90 °C for 6–24 h at atmospheric pressure in the presence of a reducing agent such as NaNO3, LiAlH4, hydrazine hydrate, AA, or NaBH4 and a catalyst such as CoCl2, TiO2, ZnO, CuO, metal‐doped‐TiCh, or Cu nanoparticles. Formate yields up to 98.98 % were reported with sodium nitrate and Aeroxide P90 TiO2 catalyst at 90 °C. The advantages of this process are the mild reaction conditions and high formate yields with precious metal‐free catalysts. A disadvantage is the long reaction time. The technology is not yet proven on a commercial scale.

5.1.3. Electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 to formate

The electrocatalytic CO2 reduction to formate is a two‐electron process as shown in Equation (26). [211] The main competing reactions are the formation of CO as in Equation (17) (see above) and the hydrogen evolution reaction as in Equation (27), which depends heavily on the choice of catalyst.[ 24 , 212 ]

| (26) |

| (27) |

Catalysts show high CO2 reduction and low hydrogen evolution activity when they exhibit a weak metal‐hydrogen bond reaction. They consist of metals typically located at the left‐hand branch of Trassati's volcano plot such as silver, tin, lead, mercury, zinc, or indium (Figure 9).[ 213 , 214 ] Bi‐ or multi‐metallic systems, which are complex yet easy to produce, are promising candidates for improving selectivity and lowering overpotentials.[ 215 , 216 ] An early mechanistic study by Hori et al. found that the CO2 radical anion is formed first and bound to the tin or indium catalyst via an oxygen atom. Subsequently, the CO2 radical anion on the surface tends to be protonated at the carbon position, leading to the release as formate. Conversely, a CO2 radical anion on the surface of a gold or silver catalyst is bound to the metal via the carbon atom and therefore tends to be protonated/reduced at an O‐position, which results in the production of a *COOH intermediate that can be further reduced to CO. [217]

Figure 9.

Trassati's volcano plot shows the relationship between metal‐hydrogen bonding energies (on the x‐axis) and the exchange current for hydrogen evolution (on the y‐axis) for several metals. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [219]. Copyright 2014, Beilstein Institut.

The metals and metal oxides or sulfide‐derived catalysts promote the reaction. The oxide layer films of metals, shown on the descending branch of the volcano plot in Figure 9, can inhibit hydrogen evolution.[ 214 , 218 , 219 ]

The advantage of this process is that gaseous H2 is not required, and the reaction can be catalyzed by non‐noble metals. Furthermore, the energy input can be potentially supplied from renewable sources such as solar energy. [220] In general, the electrochemical method has several advantages as it is a room‐temperature process that favors high selectivity and higher CO2 solubility.

To be economically feasible, the target is to create a system that has a high FE and a high current density, with a catalyst that is stable for a long time. An overview of the implications and new developments on metal catalysts used in the reduction of CO2 to formate is given in the comprehensive Review by Wu et al. and a perspective by Zhang and co‐workers.[ 220 , 221 ] Black carbon or salt deposits on metal electrodes have been observed during the electrochemical reduction of CO2. [222] This can result from the further reduction of formate on the catalyst surface if the formate stays in contact with the catalyst for too long. The GLS (gas‐liquid‐solid) cathode with a gas‐through feature can facilitate the removal of the formate products from the catalysts by gas bubbling. [212] The design of the electrodes plays a crucial part in the efficiency of the process. A comprehensive Review by Philips et al. discusses the importance of electrode design and suggests that industrially relevant yields and efficiencies will most likely require gas‐diffusion electrodes and intelligent cell designs. [33] Pilot or commercial scale tests are yet to prove the scalability and viability of this process.

5.1.4. Photocatalytic reduction of CO2 to formate

The photocatalytic reduction of CO2 makes direct use of the sun's power in that the incoming photons are harnessed to drive the reaction and CO and formate are the most commonly obtained products. [223] It is attractive as it is operated at ambient pressure, low temperature, and does not require high input energy. [188] Ideally, the solar energy can be harvested to power a water oxidation catalyst and couple it with a CO2 reduction catalyst with well‐controlled product selectivity for the CO2 reduction. [224] This reaction can be facilitated on the surface of semiconducting heterogeneous catalysts, but these systems still suffer from strong catalyst deactivation by deposited formates on the surface.[ 225 , 226 , 227 ] Hence, the most common systems for this process are homogeneous catalysts, which have been first used by Tanaka and co‐workers in the 1980s. [228] In recent years this topic gained new interest and many new systems were studied and developed.[ 224 , 229 , 230 , 231 , 232 , 233 , 234 , 235 ] The selectivity of the homogeneous systems depends on a myriad of parameters in the process design including the solvent for CO2 solubilization, electron and proton sources, photosensitizers for light‐harvesting, and lastly the design of the catalysts itself. [224] Figure 10 exemplary shows the complex nature and the reaction cycles for the most advanced system to date.

Figure 10.

Proposed mechanism for formate production under the influence of Ru catalyst and hydrous conditions. The cycle begins at the top left with the pre‐catalyst Y, which is activated by the electron transfer from the sacrificial electron donor (SED) to the photosensitizer (PS) to yield Z. With the dissociation of Cl−, the active catalyst A becomes available. A chemically transforms by complexation with a proton to form B. The dicationic complex B subsequently is reduced again by the PS to form C, which can react with CO2 to form formate and the dicationic complex D. Reduction of the dicationic complex D by the PS regenerates the initial complex A. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [224]. Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society.

The developed systems are not yet competitive on a commercial scale. [189] They lack energy efficiency, catalyst stability, and selectivity towards formate, for which a maximum of 65 % was achieved by Delcamp and co‐workers. [224] The slow reaction rates, intermittency of light, and high equipment cost due to its complexity are further drawbacks.[ 236 , 237 ] Two comprehensive Reviews by Saravanan and co‐workers and Das and Daud give an excellent overview of available catalytic systems, recent developments, and possible reactor designs.[ 188 , 189 ]

5.1.5. Enzymatic conversion of CO2 to formate

The first enzymatic catalytic formate production was reported by Pereira and co‐workers, who used a whole‐cell approach with the sulfate‐reducing bacteria D. desulfuricans. [238] These bacteria are ideal for the reaction due to their high expression levels of formate dehydrogenase (FDH) and hydrogenase (Hase), which catalyze the formate production from CO2 and H2, respectively [Eqs. (28) and 29].

| (28) |

| (29) |

The use of FDH for CO2 utilization has been widely studied and a comprehensive summary was published by Amao. [239] Two classes of FDHs exist, which depend either on a co‐factor such as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) or metals as electron donors and acceptors. [240] Both types are used in CO2 reduction processes. The use of pure enzymes requires highly purified proteins of high functionality, and it is essential to purify and handle the proteins under strictly anaerobic conditions, making their commercial application costly. [241] The stability and activity of FDH can be improved by immobilization on a support such as hollow‐fiber microreactors.[ 242 , 243 , 244 ]

The metal‐dependent FDHs are used in enzymatic electrosynthesis and were discussed in great detail in a recent Review by Zhu and co‐workers. [245] Enzymatic electrosynthesis combines enzymatic catalysis and electrochemical techniques by immobilizing the enzymes on electrode surfaces. High FE of 99 % was reported at low overpotentials of −0.66 V vs. NHE but reaction rates and current densities were still low; however, this is still in an early stage of development.[ 240 , 246 ]

The reaction with cofactor‐dependent FHDs eliminates the need for protons and follows Equation 30.

| (30) |

The cofactors can be recycled photocatalytically with a pristine TiO2 catalyst or electrochemically on copper foam electrodes. Both regeneration types were coupled with the enzymatic reactor in a semi‐batch and continuous process.[ 247 , 248 ] In the optimized systems formate yields of up to 80 % were reported, highlighting the benefit of the coupled system. However, the achieved reaction rates and scale are still far from commercial needs.

5.2. Oxalic acid production via formate coupling

The coupling of formate was first reported by Merz and Weith in 1882. [249] They found that oxalate can be produced by heating various metal formates above 400 °C in the absence of air or oxygen [Eq. 31].

| (31) |

The heating leads to mixed salts containing more than 70 % oxalate with carbonate as the main side product. Two side reactions can occur. In 1823, Gay‐Lussac discussed the stability of oxalic acid, and already then, the low decomposition temperature of 110–130 °C was reported. [250] The thermal decomposition of oxalate leads to the formation of carbonate and CO. Although more stable than oxalic acid, the formate and oxalate salts can decompose to carbonate and CO as in Equation (32) and 33.

| (32) |

| (33) |

Merz and Weith found that the amount of carbonate increases with decreasing reaction temperature. [249] Shortly after its discovery, this process became one of the main commercial ways of oxalic acid production, and several processes covering various reactor designs and reaction conditions were patented around the world in the period 1900–1936.[ 200 , 251 , 252 , 253 , 254 , 255 , 256 , 257 , 258 , 259 , 260 , 261 , 262 , 263 , 264 ] Scientifically, the reaction kinetics, mechanism, and process optimization were first extensively studied by Freidlin et al. at the beginning of the 20th century. He published at least 14 papers on the topic.[ 265 , 266 , 267 , 268 , 269 , 270 , 271 , 272 , 273 , 274 , 275 , 276 , 277 , 278 ] In the 1970s and 1980s, Shishido and Masuda in Japan and Górski and Kraśnicka in Poland investigated the coupling reaction focusing on the different gaseous products from formate decomposition concerning the solid reaction products.[ 279 , 280 , 281 , 282 , 283 , 284 ] The most recent mechanistic study was published by us in 2021.[ 63 , 285 ]

Not all formate salts are suitable for oxalate production as many undergo decomposition to carbonates, metal oxides, or metals. [284] Only alkali metal formates can be converted to corresponding oxalates in a coupling reaction. Lithium formate is a major exception to the formate decomposition series. The main products of lithium salts decomposition are CO and lithium carbonate.[ 276 , 286 ] The metal counter ion determines the temperature ranges in which formates are converted into oxalate. Freidlin et al. studied several formates and reported the optimal reaction temperatures for each and associated oxalate yields (Table 1).

Table 1.

Dependence of oxalate yield on formate melting point and optimal reaction temperature (temperature giving highest yield).[ 266 , 271 , 272 , 275 , 276 ]

|

Formate |

Melting point [°C] |

T [°C] |

Oxalate yield [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

|

HCOONa |

253 |

389 |

91 |

|

HCOOK |

157 |

455 |

82 |

|

HCOORb |

170 |

470 |

49 |

|

HCOOCs |

265 |

494 |

25 |

|

HCOOLi |

280 |

no oxalate formation |

|

Cesium formate is the most thermally stable. It requires the highest temperature of 494 °C to reach a mere 25 % oxalate yield. [266] The slightly cheaper rubidium formate requires a lower temperature of 470 °C to reach an oxalate yield of 49 and 66 % without and with base catalysts.[ 272 , 287 ] Sodium and potassium formate give much higher oxalate yields of 91 and 82 %, respectively, and therefore we only focus on those formates below. The highest oxalate yield with sodium formate can also be achieved at the lowest temperature of 389 °C. [271] However, other authors report higher oxalate yields from potassium formate. Surprisingly, Freidlin reports such high reaction temperatures for potassium formate compared to sodium formate as potassium formate has a much lower melting point. This may be due to a phenomenon described in a patent by Enderli and Schrodt, who suggest that the reaction with potassium formate actually is an equilibrium reaction. [256] Our own studies confirmed this phenomenon, and we will report the underlaying mechanism in an upcoming publication. For future continuous processes, potassium formate has the advantage of a lower melting point. This allows a lower temperature when premixing the formate with catalyst and introducing it to the reactor as a melt.

The basic catalysts increase oxalate yields and decrease reaction times and temperatures. One of the most common bases used commercially is alkali hydroxide, for which varying yields were reported as shown in Figure 11 and Table 2.[ 34 , 267 , 273 , 289 ] Hydroxides lower the reaction temperature relative to the uncatalyzed reaction by approximately 50 °C and increase the selectivity to oxalate. The oxalate yield in an industrial process could be drastically increased to 75 % using KOH in comparison to 12 % for uncatalyzed potassium formate at 410 °C.[ 273 , 275 ]

Figure 11.

Yields of potassium oxalate from KOH‐catalyzed reactions as reported in literature and patents.[ 34 , 256 , 281 , 286 , 288 ]

Table 2.

Formate coupling catalyzed by hydroxides at reaction temperatures and catalyst loadings at which the highest yields were obtained.[ 34 , 273 ]

|

Formate |

Hydroxide |

T [°C] |

Catalyst loading [mol equiv.] |

Oxalate yield [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

HCOONa |

KOH |

341 |

0.032 |

94 |

|

HCOONa |

NaOH |

330 |

0.050 |

92 |

|

HCOONa |

NaOH |

390 |

0.042 |

86 |

|

HCOONa |

KOH |

420 |

0.061 |

78 |

|

HCOONa |

KOH |

440 |

0.097 |

77 |

|

HCOOK |

KOH |

410 |

0.111 |

75 |

|

HCOOK |

NaOH |

411 |

0.135 |

70 |

|

HCOONa |

KOH |

341 |

0.032 |

94 |

Unfortunately, hydroxide does not only function as a catalyst but also as a reactant. For each hydroxide molecule added to the reaction, one carbonate is formed [Eqs. (34) and (35)], either from formate or from oxalate, as these reactions require lower temperatures than the coupling reaction. [267]

| (34) |

| (35) |

The side reactions can be minimized if the reaction is performed in a narrow temperature range due to the slower reaction rates of the side reactions. [273] As the exact mechanisms for these desired and undesired reactions are still unknown, further improvement seems to be feasible as our recent response surface modeling study shows. [290] Freidlin was the first to test alternative bases as catalysts for the reaction (Table 3). He could lower the reaction temperature whilst maintaining or improving the oxalate yield. [270]

Table 3.

Optimal temperatures to produce oxalate from sodium and potassium formates in the presence of various catalysts.

|

Formate |

Catalyst |

T [°C] |

Oxalate yield [%] |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

HCOONa |

no catalyst |

390–400 |

91 |

[270] |

|

|

vanadium pentoxide |

370–375 |

92 |

[270] |

|

|

sodium hydroxide |

340–350 |

92 |

[270] |

|

|

potassium hydroxide |

340–350 |

94 |

[270] |

|

|

sodium ethylate |

330–340 |

93 |

[270] |

|

|

amalgam of alkaline metal |

310–320 |

90 |

[270] |

|

|

sodium borohydride |

280–290 |

88 |

[281] |

|

|

alkaline metal |

280–290 |

90 |

[270] |

|

HCOOK |

no catalyst |

450–460 |

82 |

[270] |

|

|

sodium hydroxide |

410–415 |

75 |

[270] |

|

|

potassium hydroxide |

410–415 |

75 |

[270] |

|

|

sodium amide |

180–200 |

85 |

[268] [63] |

|

|

alkali hydride |

180–200 |

99 |

[63] |

|

|

amalgam of alkaline metal |

200–210 |

90 |

[270] |

|

|

alkaline metal |

180–190 |

96 |

[270] |

Alkali metals are amongst the strongest base chemicals existing. [291] Back in the 1930s, Freidlin et al. studied their effect on the reaction including reaction kinetics and possible mechanisms.[ 269 , 278 ] However, the methodology to estimate the kinetic values was different at the time and makes it hard to compare them to other studies. The reaction onset temperatures and oxalate yields, on the other hand, give a good indication of the activity of alkali metals. Pure metals showed exceptionally high selectivity towards oxalate with yields up to 94 %. More importantly, the reaction temperature dropped significantly by 200 °C to the respective melting points of the formates. The major drawback of alkali metals is their high reactivity with water and oxygen. [291] They must be stored and processed in inert conditions, which makes it difficult and costly to utilize them on a large scale. Freidlin suggested using alkali amalgams to increase the metal's specific densities. The catalyst submerges in the reaction mass and has no contact with potential oxygen, whilst still being active. Then the amalgam could be recycled and put back in the reactor. [269] Although this makes catalyst recycling possible, today amalgams underlay strict restrictions as they pose health and environmental risks. [292] They also reported that sodium amide (NaNH2) could potentially catalyze the reaction. They obtained 85 % oxalate yield at 240 °C from potassium formate with 2–4 wt% loading of sodium amide. In our recent publication, we could show oxalate yields of 99 % at 180 °C and loadings of 0.5 wt%. The disadvantage of using amide catalysts is the liberation of NH3, which needs to be removed from the H2 formed in the coupling reaction, while hydride catalysts just liberate H2. [63]

Górski and Kraśnicka explored the addition of sodium borohydride (NaBH4) to sodium formate.[ 279 , 282 ] The use of 5 mol% sodium borohydride at 290 °C leads to 88 % oxalate yield from sodium formate, whilst with a 1 : 1 molar ratio no conversion was observed.

When ferric oxides are present on the reactor walls, the reaction is inhibited. If glass powder is added to the reaction, however, the yield increased up to 90 %, which leads to the proposition of a chain mechanism where chain initiation might take place at a solid surface. This claim was not investigated further. [273]

The most recent additions are metal hydrides, which show similar base strength to alkaline metals but are easier to handle. They were first used by Lakkaraju et al., who reported a drop in reaction time and increase in yield but no drop in reaction temperature for sodium formate coupling. [34] Inspired by this, we tested various superbases as catalysts for the reaction. We found that absolute water‐ and oxygen‐free reaction conditions are important. In these conditions, we observed for potassium formate coupling a reaction start corresponding to the melting of the substrate, reaction times of 30 s to 2 min, which is 10 times below the values reported by Lakkaraju et al., and yields between 97 and 99 %. [63]

Hartman and Hisatsune estimated the activation energy of calcium formate decomposition in halide matrices using IR spectra. This led to an activation energy of 217.5±33.4 kJ mol−1. [293] Lakkaraju et al. were yet the only ones who estimated the activation energy using a catalyst. They calculated an activation enthalpy of 171.5 kJ mol−1 and activation entropy of −25.1 kJ−1 mol−1 for sodium formate coupling catalyzed by sodium hydride. These values account for an activation energy of approximately 177 kJ mol−1 and a pre‐exponential factor A of 1.327×1037 s−1. The high pre‐exponential factor indicates mass transfer limitations in this case. We obtained 202 kJ mol−1 for uncatalyzed reactions and 129 kJ mol−1 for the KOH‐catalyzed reaction with pre‐exponential factors of 1.28×1019 and 1.06×1013, respectively, suggesting that physical effects such as mass transfer, substrate melting, or thermal loss due to gas formation only played a minor role in these reactions. [63]

This is however different for the newly proposed superbase catalysts, for which no sensible activation energies could be measured due to the coincidence of the reaction start with the physical phenomenon of substrate melting, which causes strong mass transfer effects. [63] The reaction then proceeds very vigorously due to the rapid availability of substrate for the reaction once it is molten. The real reaction start temperature thus cannot be investigated.

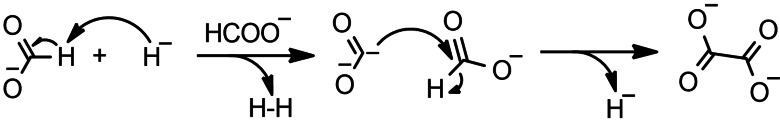

Over the years many different mechanisms were proposed for the seemingly simple coupling reaction.[ 34 , 278 , 280 , 283 , 293 , 294 ] These include studies on how alkali metals act in the reaction, the role of carbonite ion (CO2 2−) as intermediate in the reaction, as well as on the gaseous products that are formed during formate decomposition. Górski and Kraśnicka were the first to suggest carbonite as an intermediate in the reaction in 1987. [280] In 2016, Lakkaraju et al. proposed a mechanism involving a hydride‐catalyzed reaction including carbonite. [34] Carbonite dianions are strong nucleophiles and attack formate to form oxalate as shown in Scheme 9. In a recent Review, Paparo and Okuda discuss the reactivity and nature of the Carbonite species. [295]

Scheme 9.

Mechanism for hydride‐catalyzed formate coupling reaction as postulated by Lakkaraju et al. [34]

The hydrogen atom from the attacked formate is released as a hydride, thereby regenerating the hydride catalyst. The postulated mechanism was supported with Raman measurements during the sodium formate coupling and density functional theory (DFT) calculations. In the DFT calculations, the respective energies of possible intermediates at different temperatures as shown in Figure 12 were calculated.

Figure 12.

DFT free‐energy calculations of the catalytic conversion of formate into oxalate as salts of sodium (red 663 K, orange 298 K) and potassium (navy 713 K, blue 298 K). Figure adapted with permission from Ref. [34]. Copyright 2016, Wiley‐VCH.

The rate‐determining step (RDS) in the mechanism by Lakkaraju et al. is the deprotonation of formate by the catalyst. This is shown in Figure 12 as an I2→TS step, and the energy value for this step was estimated to be 41 kcal mol−1. Although we were unable to observe the carbonite ion as intermediate in potassium formate coupling using in‐situ Raman spectroscopy, we recently confirmed the involvement of carbonite intermediate by using isotope labeling in quenching studies. [63] Most recently, we reported the mechanism for the hydroxide‐catalyzed reaction, which depends on the in‐situ formation of the active hydride species and then follows the pathways described by Lakkaraju et al. [285]

In recent years the formate coupling reaction gained more commercial interest again with the upcoming CCU pathways including formate as intermediate. Several new patents and studies were published presenting new reactor designs for continuous operation. They often include advanced technologies such as microwave heating or the use of nozzles as used in spray dryers.[ 35 , 296 , 297 , 298 , 299 , 300 , 301 , 302 , 303 , 304 , 305 , 306 , 307 , 308 , 309 , 310 ] Overall, formate coupling provides a sustainable pathway to oxalate. The high yield is an advantage, and the previous drawbacks of high temperatures and long reaction times could recently be tackled with new catalyst types. Additionally, this reaction was performed for many decades on an industrial scale.

5.3. Acidification of oxalate to oxalic acid

In all previously described processes and the upcoming alkali fusion of biomass (Section 8.2), oxalate is produced. This requires the introduction of an acidification step to obtain oxalic acid. One option is the use of inorganic acids such as sulfuric or hydrochloric acid following Equation 36. [264]

| (36) |

Electrodialysis is an alternative process that helps to avoid the use of corrosive acids and the formation of stoichiometric amounts of salts.[ 311 , 312 , 313 , 314 ] In an electrodialysis process, the alkali ion and the oxalate migrate to the cathode and anode, respectively, but the oxalate ions would be oxidized and decomposed by oxygen in the anodic compartment. To avoid this, cation and bipolar membranes are required. The simplest option is the use of two cation‐exchange membranes as shown in Figure 13A. Protons are provided by water splitting in the hydrogen evolution reaction on the anode [Eq. (37)]. The hydroxy ions are provided by water splitting in the oxygen evolution reaction on the cathode [Eq. 38].[ 312 , 315 ]

| (37) |

| (38) |

Figure 13.

Simple electrolysis cell‐design (A) uses two cation‐exchange membranes (blue) to create three compartments. In the anodic compartment, the oxygen evolution reaction on the anode produces protons and oxygen. The protons migrate to the middle compartment, where they exchange potassium for a proton to form oxalic acid. The potassium migrates through the cation‐exchange membrane to the cathodic compartment, where it forms potassium hydroxide with the hydroxide ions produced on the cathode during the hydrogen evolution reaction. In the advanced multifunctional cell (B), which has the fourth compartment by adding a bi‐polar membrane, the salt splitting can be coupled with the production of high‐value chemicals. A reductant is reduced in the cathodic compartment and an oxidant is oxidized in the anodic compartment. The proton for the reduction is drawn from the bipolar membrane in which water splitting is taking place.

To improve the economic feasibility of the electrocatalytic salt splitting process it is desirable to produce high‐value products with the invested electrons rather than perform water splitting. This can be achieved by combining the cation‐exchange membrane with other membranes such as bipolar membranes. [316] In particular, electrodialysis bipolar membranes (EDBM) can be exploited for the production of organic acids via water splitting in bipolar membranes. [311]

EDBM can achieve the highest utilization of resources by supplying H+ or OH− in situ and keeping the electrodes available to produce high‐value products through oxidation and reduction reactions. The in‐situ production has been successfully used for the production of formic acid, acetic acid, propionic acid, lactic acid, citric acid, gluconic acid, and many other carboxylic acids and amino acids.[ 314 , 315 , 317 , 318 , 319 , 320 ]

The concept of coupling with other reactions in a multi‐compartment cell is shown in Figure 13B. Bipolar membranes are commercially available and are used in various processes such as desalination of industrial wastewater, lithium battery recycling, hydrochloric acid and sodium hydroxide production from brines, and magnesium recovery from seawater.[ 321 , 322 , 323 , 324 , 325 , 326 ] The coupling of the electrodialysis processes with other electrochemical reactions is still in development and requires more research to find reactions that can be coupled optimally in the separate compartments.

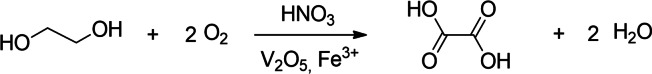

6. Ethylene Glycol Oxidation

Oxalic acid can be obtained from ethylene glycol (EG) via oxidation.[ 327 , 328 , 329 , 330 , 331 ] This route might be interesting in the future as new sustainable cost‐competitive routes for EG production (e. g., from carbohydrates) emerge (Scheme 10).[ 102 , 332 , 333 ]

Scheme 10.

(a) Ethylene glycol can be oxidized to oxalic acid by catalytic oxidation with oxygen or nitric acid. (b) A newer alternative route uses electrochemical oxidation.

6.1. Ethylene glycol production

EG is a bulk chemical and commercially produced in megaton quantities mainly from fossil sources through ethylene oxide hydrolysis. [334] It is mainly used as a monomer for polyester (PET) production and as an anti‐freeze agent and engine coolant additive. Alternative reaction pathways include coupling of CO and new pathways from biomass such as cellulose and glucose as well as from glycerol, which is produced on a large scale as a by‐product in biodiesel refineries are developed and tested on a pilot scale.[ 333 , 335 , 336 , 337 , 338 , 339 ] Details of current EG production pathways and future development are described and discussed in great detail in various Reviews.[ 332 , 333 , 335 , 337 , 338 ] Overall, sustainable alternatives for the production of EG are available and increasingly employed on a commercial scale.

6.2. Catalytic oxidation of ethylene glycol to oxalic acid

Oxalic acid production via EG oxidation is a simple one‐step process as shown in Scheme 11 and was first patented by the Japanese company Mitsubishi in 1969. [327] Oxalic acid was produced at a high yield with the addition of an acid mixture comprising 2–60 wt% HNO3, 20–78 wt% H2SO4, and 20–50 wt% H2O. The molar ratio of HNO3 to EG should not be less than 3 : 1.

Scheme 11.

Oxidation of ethylene glycol using mixed acids in water.