Abstract

The pharmacokinetic profile of AAV particles following intrathecal delivery has not yet been clearly defined. The present study evaluated the distribution profile of adeno-associated virus serotype 5 (AAV5) viral vectors following lumbar intrathecal injection in mouse. After a single bolus intrathecal injection, viral DNA concentrations in mouse whole blood, spinal cord, and peripheral tissues were determined using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). The kinetics of AAV5 vector in whole blood and the concentration over time in spinal and peripheral tissues were analyzed. Distribution of AAV5 vector to all levels of the spinal cord, dorsal root ganglia, and into systemic circulation occurred rapidly within 30-minutes following injection. Vector concentration in whole blood reached a maximum 6-hours post-injection with a half-life of approximately 12-hours. Area under the curve data revealed the highest concentration of vector distributed to dorsal root ganglia tissue. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed AAV5 particle colocalization with the pia mater at the spinal cord and macrophages in the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) 30-minutes after injection. These results demonstrate the widespread distribution of AAV5 particles through cerebrospinal fluid and preferential targeting of DRG tissue with possible clearance mechanisms via DRG macrophages.

Keywords: gene therapy, AAV5 vector, mouse, lumbar intrathecal injection, pharmacokinetics, qPCR

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Delivery of viral gene therapies directly into cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) using intrathecal (IT) injection has the potential to treat a variety of neurobiological conditions1–4 while providing long-term treatment following a single administration. Recombinant adeno-associated virus (AAV) as a vector for CSF-based gene therapy has many advantages over other viruses, including low immunogenicity, ability to infect non-dividing cells, potential for long-term gene expression, and selective cellular targeting based on capsid serotype5–7. AAV is comprised of a small (~20 nm) virion containing of a ~4.8 kb single-stranded viral genome surrounded by a protein capsid shell which binds to cell surface receptors, initiating the process of virus internalization8. Several AAV serotypes, such as serotype 5, have inherent neuronal tropisms providing potential therapeutic applications in treating central nervous system (CNS) disorders5, 9–11. Previous studies have demonstrated that AAV serotype 5 (AAV5) preferentially transduces astrocytes, neurons, and large diameter DRG neurons providing stable and long-term transgene expression12–16.

Determining the distribution of viral vectors in vivo has largely relied on the expression of reporter genes. Reporter genes often express fluorescent or luminescent proteins which are subsequently visualized to determine tissues and cell populations that have been transduced12. When using viral vector gene therapies, reporter genes are inserted into the viral genome. However, a significant challenge of utilizing AAV vectors for gene therapy is their small DNA capacity, limiting the size of genes that can be expressed and the ability to co-express both a gene of biomedical interest as well as a fluorescent reporter gene. Additionally, expression of fluorescent proteins such as green fluorescent protein (GFP) has been shown to elicit immune response targeting the fluorescent protein. This immune response can cause substantial damage to the CNS tissue depending on route of administration and the target fluorescent protein to be expressed17, 18. The use of fluorescent proteins as markers for successful transduction also assumes that transduction of the reporter and target gene are occurring at similar efficiencies and expression levels within tissues of interest, parameters which are not likely to be equivalent. For these reasons, when determining the distribution of viral vectors, it is important to evaluate viral vector biodistribution rather than rely solely on reporter gene expression.

While many CNS gene therapies require CSF-based delivery for localized and targeted delivery, few studies have investigated viral vector kinetics following systemic delivery in vivo. With the increasing interest in the use of AAV vectors to treat CNS disorders, it is imperative that the distribution and kinetics of these therapeutics within the CSF and nervous tissue is understood. A recent study by Ohno et al. used magnetic resonance to evaluate the AAV serotype 9 (AAV9) CSF distribution following different CSF-based delivery methods, providing valuable information about the kinetics of AAV9 in CSF in non-human primates19. However, the distribution profile of viral vectors to spinal and peripheral tissues remains largely unknown. In the present study, we sought to determine the distribution and elimination profile of AAV serotype 5 (AAV5) vectors in the circulation as well as in spinal cord and surrounding tissue following intrathecal injection. We used quantitative methods to determine an accurate vector concentration versus time profile in whole blood, central and peripheral nervous system tissue, and liver. The findings provide valuable information about the intrathecal kinetic parameters of AAV5 vectors in mice.

Experimental Description

Animals.

Adult (3–4 month) male (n = 6 or 12 per timepoint) and female (n = 6 per timepoint) ICR-CD1 mice (21–24 g, Envigo, Madison, Wisconsin) were used for kinetics studies. Immunofluorescent studies were conducted in adult (3–4 month) male (n = 4 per timepoint) ICR-CD1 mice (21–24 g, Envigo, Madison, Wisconsin). All mice were housed with free access to food and water in a temperature- and humidity-controlled environment. Mice were housed 4 mice to a cage in a 12-hour light/dark cycle. All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Minnesota.

AAV Vector and Packaging.

AAV vector containing an EF-1 alpha (human elongation factor-1 alpha, EF1α) regulated green fluorescence protein (GFP) sequence (P42212.1) has been previously described20. The resulting plasmid pAAV-GFP contains the GFP expression cassette (mCMV enhancer- EF1α promoter - GFP and simian virus 40 late polyadenylation signal) flanked by AAV2 inverted terminal repeats (ITRs). This vector was packaged into AAV5 virions at the University of Florida Vector Core by co-transfection of HEK293 cells and purified from cell lysates on an iodixanol step gradient followed by Q Sepharose ion exchange chromatography21. Vector titers were 1.37 × 1014 vector genomes/mL for AAV5- EF1α-GFP. Virus was diluted in sterile normal (0.9%) saline and delivered in 5 μL volumes for a total injection of 6.85 × 1011 vector genomes.

Intrathecal Injections.

AAV5-EF1α-GFP viral vectors or saline were delivered centrally via intrathecal (IT) injection in conscious male and female mice22 by an experimenter (KFK) with over 25 years of experience with this drug delivery method. We have previously described our adapted method for intrathecal delivery of viral vectors23. Catheter setup included a 27-gauge, 1.25-inch needle whose base is attached to 250 mm of PE20 tubing. The point of a 27-gauge, 0.5-inch needle is carefully inserted into the opposite end of the PE20 tubing and attached to 50-μL Luer-hub Hamilton syringe. To conserve viral vector, deionized water is injected into the PE20 tubing from the Hamilton syringe leaving a space of air at the end of the tubing near the 1.25” needle. This air bubble in the PE20 tubing was used as an indicator that viral vector had been successfully injected. To administer the injection, the mouse hindquarters are stabilized by gently holding the iliac crest and inserting the needle (beveled side towards the head of the mouse) at a 70° angle relative to the spinal column. Following a characteristic tail flick that occurs when the needle has punctured the dura mater, the AAV5-ef1α-GFP vector or saline is slowly injected into the intrathecal space. After injection, the animal is returned to its home cage and monitored for any variances in behavior.

Real-Time Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR).

At specified time points (0.5-, 2-, 6-, 12-, 24-, and 48-hours) following intrathecal injection of AAV5-EF1α-GFP (n=6; 3 male and 3 female for the 0.5-, 2-, 12-, and 24-hour time points or n=9; 6 male and 3 female for the 6- and 48-hour time points) or saline (n=6; 3 male and 3 female for the 0.5-, 2-, 12-, and 24-hour time points or n=9; 6 male and 3 female for the 6- and 48-hour time points), animals were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane and quickly sacrificed by decapitation. Trunk blood was collected into lavender 3 mL K3 EDTA (0.06 mL, 7.5% solution) tubes (Covidien) and whole brains were removed from the skull. Spinal cords were removed via hydraulic extrusion, and cervical, thoracic, and lumbar regions were dissected and separated. Cervical and lumbar dorsal root ganglia and a small portion of the inferior medial lobe of the liver were removed via microdissection. All dissected tissue was submerged in 400 μL of DNA/RNA Shield (ZymoResearch). Following dissection, tissue was stored at −20°C until further processing. At time of processing, dissected tissue was homogenized using one scoop of 0.5 mm glass beads (BioSpec Products) using a Bullet Blender (Next Advance). Viral DNA was extracted and purified from tissue and whole blood using the Quick-DNA Viral kit (ZymoResearch) following the manufacturer’s instructions and dissolved in nuclease-free water. DNA concentration was determined by spectrophotometric analysis using the NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Sample volume was determined so that 30 ng of DNA was used for each PCR reaction.

Concentration of viral vector in whole blood or tissue was determined using real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). RT-qPCR was performed on a CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad) machine using primers for the Simian Virus 40 (SV40) polyadenylation region and the Roche LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master Mix (Roche). Oligonucleotide primers used for these experiments included the SV40 primer sequences: F 5’-AGCAATAGCATCACAAATTTCACAA-3’ and R 5’-CCAGACATGATAAGATACATTGATGAGTT-3’24. Each 20 μL reaction mixture contained 10 μL of 2X SYBR master mix, 6 μL of RNase/DNase free H2O, 150 nM each of forward and reverse primer, and 30 ng of DNA sample. All samples were run in triplicate. Two no-template control (NTC) reactions (20 μL) and one RNase/DNase free H2O blank (20 μL) were included in each run. 96 well plates were sealed with an optically clear Microseal ‘B’ seal (Bio-Rad). PCR cycling conditions included: 10 min at 95°C, then 45 cycles each of denaturation for 15 seconds at 95°C, and then annealing and extension for 30 seconds at 60°C. Melting curves were analyzed to ensure a single PCR product for each reaction. PCR product concentrations were interpolated from the CT values of serially diluted AAV5-CMV-hADC plasmids of a known concentration containing the SV40 region25. Triplicate concentration values were averaged within animal and within treatment groups.

Pharmacokinetic Data Analysis.

Whole blood concentration-over-time profile from a single intrathecal dose was analyzed using Phoenix WinNonlin version 6.4 (Certara USA, Inc., Princeton, NJ). Noncompartmental analysis was used to calculate the area under the curve (AUC) of whole blood concentrations. The AUC at the last time point (AUC(0-t)) was calculated using Log-linear trapezoidal integration. Using, Phoenix’s noncompartmental analysis module, other parameters and metrics were determined. These included the apparent clearance (CL/F), apparent volume of distribution (Vd/F), half-life, Tmax, and Cmax.

Immunohistochemistry.

At specified time points (0.5-, 2-, 12-, and 24-hours) following intrathecal injection of either AAV5-EF1α-GFP (n=3) or saline (n=1), animals were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane and quickly perfused transcardially with calcium-free Tyrode’s solution (in mM: 116 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1.6 MgCl46H20, 0.4 MgSO47H2O, 1.4 NaH2PO4, 5.6 glucose, and 26 Na2HCO3) followed by fixative (4% paraformaldehyde and 0.2% picric acid in 0.1M phosphate buffer, pH 6.9). The spinal cords and dorsal root ganglia were dissected and submerged in 10% sucrose overnight at 4°C. Spinal cords were sectioned into cervical, thoracic, and lumbar regions, embedded in OCT compound (Tissue-Tek), flash frozen, and stored at −80°C overnight. Sections were cut at 14 μm thickness using a cryostat (OTF5000, Bright Instruments) and thaw mounted onto gel-coated slides and stored at −20°C until further processing. At the time of immunostaining, slides were air-dried, tissue was encircled with a PAP pen (Sigma-Aldrich), and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature in PBS diluent containing 0.3% Triton, 1% BSA, and 1% normal donkey serum. Following incubation overnight at 4°C with primary antibody diluted in PBS diluent, slides were washed with 1X PBS for 30 minutes, and incubated with an appropriated fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody diluted in PBS diluent at room temperature for 1 hour. Slides were washed three times with 1X PBS and coverslipped using FluoroSave reagent (EMD Biosciences, Inc.). Images were captured using an inverted confocal microscope (Olympus FluoView FV1000 IX2) and processed using Adobe Photoshop.

Antibodies.

The following primary antibodies were used for immunohistochemical staining of mouse tissue: rabbit anti-VP3 (1:200; OriGene Technologies Inc.); goat anti-collagen IV (1:500; SouthernBiotech); goat anti-Iba1 (1:1000; Wako Chemical).

Statistical Analysis.

Graphical representation and statistical analyses were completed using GraphPad Prism (version 7; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). All experimental data are presented as the mean ± S.E.M. Outliers were removed from dataset using the ROUT method and a Q value of 0.1%. Differences between data sets were considered significant at α = 0.05. An ordinary 2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was performed comparing viral genome copy number in spinal cord levels and both DRG levels. An ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was performed on the AUC values comparing all spinal levels. A two-tailed unpaired t test was used to compare AUC values between cervical and lumbar DRG.

Results

Quantification of viral vector distribution following intrathecal injection

To determine the distribution of our AAV5-ef1α-GFP viral vector following intrathecal injection, viral genome copy number was quantified in nervous system tissue, liver, and whole blood at 0.5-, 2-, 6-, 12-, 24-, and 48-hours post-injection. Tissues and whole blood were analyzed for the presence of viral DNA using quantitative PCR with primers targeting the SV40 polyadenylation sequence.

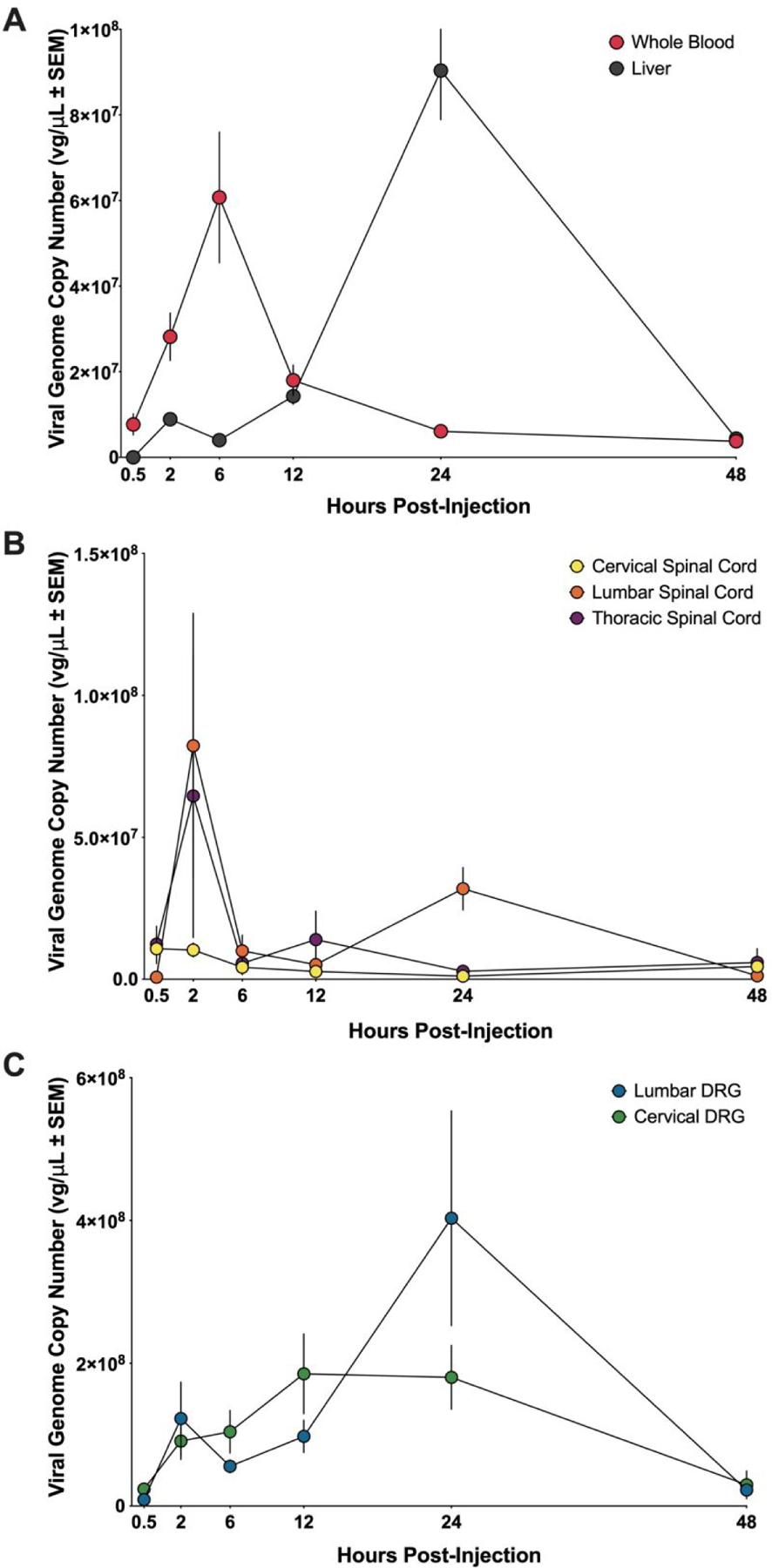

Following a single bolus intrathecal dose of 6.85 × 1011 vector genomes (vg), the concentration-time curve of whole blood samples (Figure 1A) follows a two-compartment pharmacokinetic model with half-life of 11.66 hours and a peak viral genome concentration of 6.08×107 ± 1.53×107 vg/μL at 6-hours post-injection. The apparent volume of distribution (Vd) was 1.24×103 μL and the apparent clearance (CL) was 73.47 μL/hr (Table 1). The goodness of fit statistic (Rsq) for the terminal elimination phase in whole blood was 0.80 and the minimal difference between the observed and predicted AUCs (7.69 ×108 hr·vg/mL and 7.52 ×108 hr·vg/mL, respectively) demonstrates the accuracy of this model to fit our data. The concentration-time profile for viral vector distribution to the liver was offset proportionally to viral vector entry into systemic circulation (Figure 1A). Viral vector accumulation in the liver begins to considerably rise between 6- and 24- hours post-injection with a maximum observed viral concentration (Cmax) in liver tissue of 9.04×107 ± 1.15×107 vg/μL, which occurred 24-hours following intrathecal injection.

Figure 1. Concentration-time for AAV5 vector DNA in all tissue and whole blood.

(A) AAV5 vector genome concentration-over-time profiles for whole blood (red circles) and liver (gray circles). (B) AAV5 vector genome concentration-over-time profiles for cervical spinal cord (yellow circles), thoracic spinal cord (purple circles), lumbar spinal cord (orange circles). (C) AAV5 vector genome concentration-over-time profiles for cervical dorsal root ganglia (DRG) (green circles), and lumbar dorsal root ganglia (DRG) (blue circles). Concentration values represented as mean ± SEM. For the 30 min, 2 hr, 12 hr, and 24 hr timepoints, n = 6 (3 male and 3 female) for AAV5-treated and n = 6 (3 male and 3 female) for saline-treated. For the 6 hr and 48 hr timepoints, n = 9 (6 male and 3 female) for AAV5-treated and n = 9 (6 male and 3 female) for saline-treated.

Table 1. Kinetic evaluation of AAV5 vector in whole blood following intrathecal delivery.

Table includes the area under the curve (AUC), maximum concentration (Cmax), apparent clearance (CL), apparent volume of distribution (Vd), mean residence time (MRT), and half-life values for AAV5 viral vector in whole blood.

| AUC (vg ● h / μL) | Cmax (vg/μL) | CL (μL/hr) | Vd (μL) | MRT (hr) | Half-life (hr) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Blood | 7.30×108 ± 1.93×108 | 6.08×107 ± 1.53×107 | 73.47 | 1.24×103 | 16.70 | 11.66 |

AUC, tmax, and Cmax values for all tissues can be found in Table 2.

Based on the small total CSF volume (~35 μL) and previous studies of drug and tracer intrathecal distribution in the rats26–28, we hypothesized that a rapid distribution of viral vector from the site of delivery would follow bolus injection to the lumbar intrathecal space. Rapid distribution of viral vectors was observed in the cervical spinal cord (CSC) following intrathecal injection with the maximum viral genome concentration (Cmax) of 1.08×107 ± 5.25×106 vg/μL occurring at 30-minutes (Figure 1B). Both lumbar spinal cord (LSC) and thoracic spinal cord (TSC) reached Cmax at 2-hours post-injection (8.24×107 ± 4.67×107 vg/μL and 6.46×107 ± 4.98×107 vg/μL, respectively) (Figure 1B). Lumbar spinal cord and thoracic spinal cord were assessed at the 2-hour time point and both were significantly greater than that of cervical spinal cord (p = 0.004 and p = 0.04, respectively).

Distribution of viral vector to cervical dorsal root ganglia (CDRG) occurred at 30-minutes following intrathecal delivery and increased until a Cmax of 1.85×108 ± 5.60 ×107 vg/μL was reached 2-hours post-injection (Figure 1C). Viral genome copy number in CDRG remained elevated until the 24-hour time point at which time the concentration decreased. In contrast, viral genome concentration in lumbar dorsal root ganglia (LDRG) had a minor increase at 2-hours but declined before increasing again to a Cmax value of 4.03×108 ± 1.50×108 vg/μL at 24-hours following bolus delivery (Figure 1C). There was a significant difference (p = 0.0150) in genome copy number in LDRG and CDRG at 24-hours following vector delivery. By 48-hours following injection, the viral concentration in LDRG decreased to 2.25×107 vg/μL.

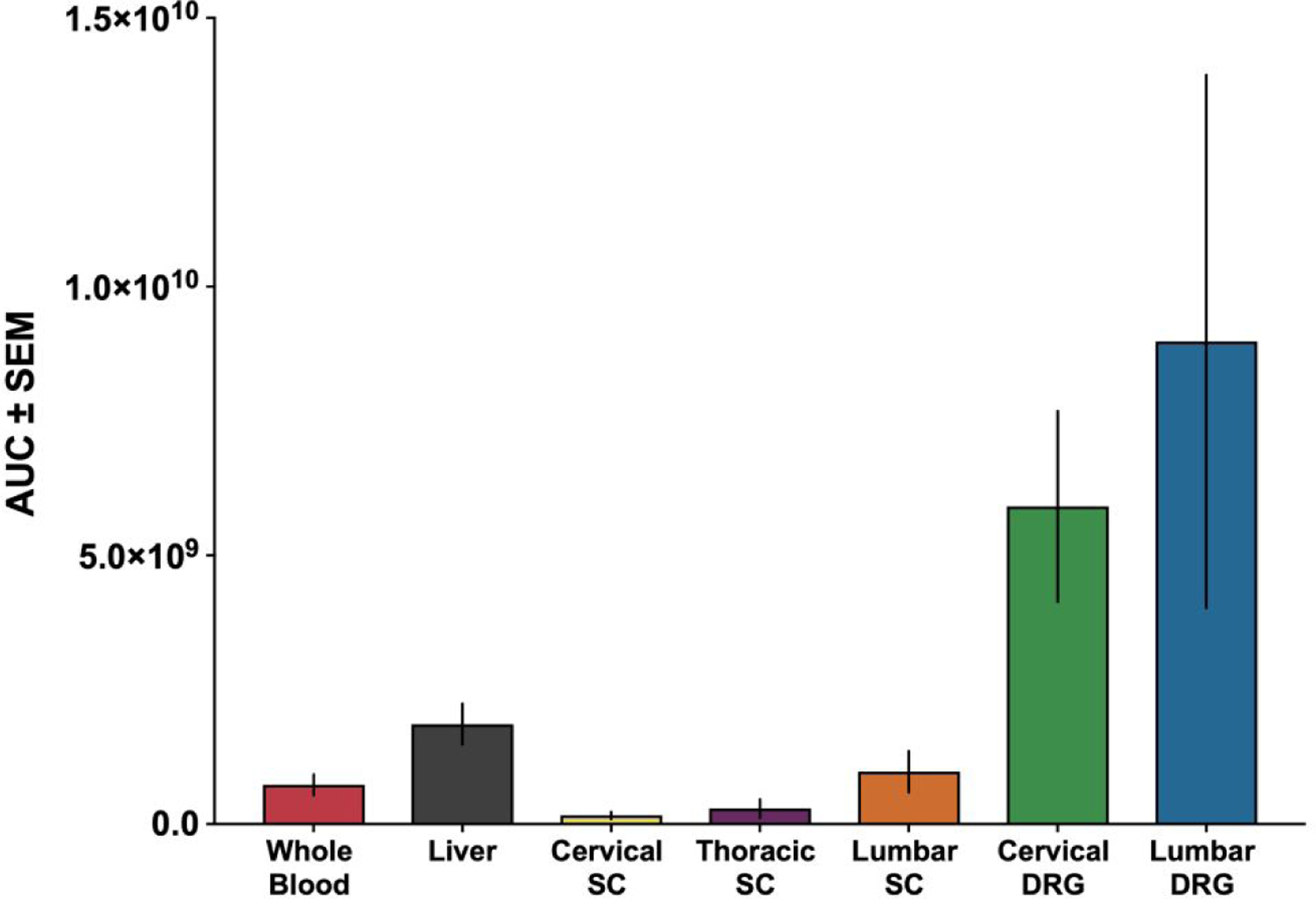

Graphical representation of AUC (Figure 2) reveals that, of the tissues analyzed, the cervical and lumber DRG had the highest concentrations of AAV5 vector measured throughout the time course. No statistically significant differences were found between the AUC values between LDRG and CDRG or between spinal cord levels.

Figure 2. Area under the curve analysis for viral vector in all tissue and whole blood.

Bar graph representation of area under the curve (AUC) values for whole blood (7.30×108 ± 1.93×108), liver (1.86×109 ± 3.80×108), cervical dorsal root ganglia (CDRG) (6.14×109 ± 1.90×109), lumbar dorsal root ganglia (LDRG) (9.16×109 ± 4.97×109), cervical spinal cord (CSC) (1.72×108 ± 7.11×107), thoracic spinal cord (TSC) (5.21×108 ± 3.86×108), and lumbar spinal cord (LSC) (9.75×108 ± 3.83×108). All AUC values represented as mean ± SEM. For the 30 min, 2hr, 12hr, and 24 hr timepoints, n = 6 (3 male and 3 female) for AAV5-treated groups and n = 6 (3 male and 3 female) for saline-treated groups. For the 6 hr and 48 hr timepoints, n = 9 (6 male and 3 female) for AAV5-treated groups and n = 9 (6 male and 3 female) for saline-treated groups.

AAV5 particle visualization.

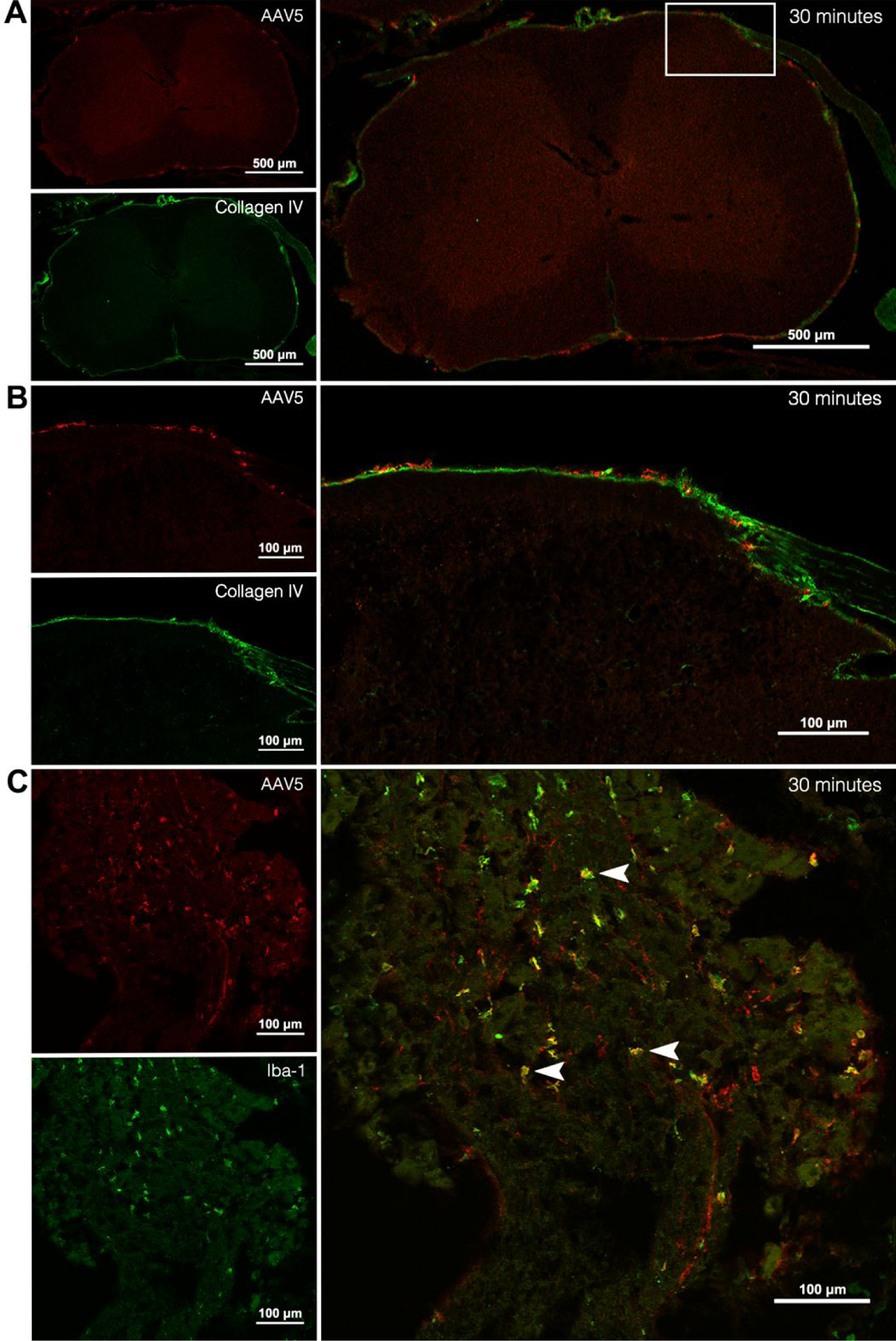

In order to visualize AAV5 particle distribution following intrathecal injection, spinal cords and DRG were analyzed by immunohistochemistry. An antibody targeting VP3, an AAV capsid surface protein, was used to visualize the viral particles at 0.5-, 2-, 12-, and 24-hours post-injection. Tissue sections were co-labeled with various cell markers to define regions and cell types associated with AAV5 particle immunoreactivity (AAV5/VP3-ir).

This analysis suggested that AAV5 viral particles distribute to the spinal cord surface within 30-minutes following injection. At this time point, AAV5/VP3-ir was observed in close association with the pia mater and subarachnoid blood vessels (Figure 3A and 3B, Supporting Figure 1A), which were labeled by collagen IV-ir, a known marker for these tissues. Limited AAV5/VP3 labeling was observed in this location at 2-, 12- and 24-hours post-injection (Supporting Figure 1B–D). Also 30-minutes after delivery, AAV5/VP3-ir appeared to be present in macrophages within the DRG, based on colocalization with the macrophage marker Iba1 (Figure 3C). The presence of AAV5/VP3-ir in the DRG at later time point could not be established conclusively.

Figure 3. Representative images of AAV5-ir in spinal cord and DRG following intrathecal administration of AAV5 vector.

(A) Spinal cord 30-minutes post-injection with AAV5-ir (red) and collagen IV-ir (green) and overlay (large panel). (B) Enlargement of white box in overlay panel from (A) of spinal cord 30-minutes post-injection with AAV5-ir (red) and collagen IV-ir (green) and overlay (large panel). (C) Lumbar DRG 30-minutes post-injection with AAV5-ir (red) and Iba1-ir (green) and overlay (large panel). Arrowheads indicate macrophages with AAV5 colocalization. n = 4 (3 AAV5-treated and 1 saline-treated groups).

Discussion

Adeno-associated virus (AAV)-based vectors continue to be at the forefront of gene therapeutic research and development. Intrathecal delivery of AAVs results in transduction of cells within both the CNS and peripheral nervous system (PNS) by direct delivery into the CSF, which bypasses the blood brain barrier (BBB). However, the pharmacokinetics of AAV in the intrathecal space following lumber CSF-based delivery is not well characterized. The majority of studies characterizing AAV distribution have relied on the use of fluorescent reporter genes, which have drawbacks such as limited vector genome size and the possible complication of immune response targeting the expressed foreign protein. Given these disadvantages to using the expression of reporter genes, we performed pharmacokinetic studies on AAV serotype 5 vector following intrathecal administration in mice using quantitative PCR to determine viral genome copy number within tissues of interest.

The Tmax and Cmax of viral genome copy number varies for each tissue and is indicative of how viral vectors distribute following intrathecal injection. Tmax in whole blood occurs 6-hours following intrathecal injection, with entrance into the blood stream occurring shortly following delivery. At 30-minutes following injection, 7.42×106 ± 2.37×106 vector genomes were detected in whole blood. This rapid distribution into systemic circulation may be the result of viral particle backflow through the needle tract and entering into systemic circulation via the epidural vasculature. Additionally, the subarachnoid space is highly vascularized and contains arachnoid villi. Arachnoid villi are responsible for the clearance of CSF and removal of macromolecules29, 30 from the subarachnoid space into deep cervical and lumbar lymph nodes31–35. Subarachnoid vessels possess specialized pores, stomata, that may provide another early route of entry for viral particles into the systemic circulation35, 36.

Distribution into the liver begins to rise appreciably 6-hours following injection. Not surprisingly, this correlates to and is offset by the rise of viral vector in whole blood. As viral particles enter into the circulation they will pass through the hepatic circulation, allowing for metabolism of viral proteins or transfection of hepatocytes. AAV vectors, in general, have a natural tropism for hepatocytes37–39. Although AAV serotypes 8 and 9 have been shown to have higher transduction efficiency in the liver than AAV5 vectors40, the observed liver accumulation of AAV5 vectors is consistent with the role of the liver in metabolism and the inherent AAV vector tropism for liver cells41. The slightly greater Cmax value observed in liver tissue (9.04×107 ± 1.15×107 vg/μL) as compared to whole blood (6.08×107 ± 1.53×107 vg/μL) is most likely due to drainage of CSF directly into meningeal lymph nodes and subsequently into the hepatic circulation29, 30, 32, 34, 35.

Viral DNA was detected in all spinal levels 30-minutes following intrathecal injection. Lumbar and thoracic spinal cord concentrations increased considerably at 2-hours post-injection and a second concentration increase is observed in lumbar spinal cord at 24-hours post injection. This significant increase in viral vector concentration in lumbar and thoracic spinal cord at the 2-hour time point is consistent with their proximity to the injection site. The high variability in vector concentration at this time point for the lumbar and thoracic spinal cord parallels the high inter-patient pharmacokinetic variability that is observed clinically with intrathecal injection and could be due to multiple factors including, but not limited to, variations in needle angle and/or positioning, variations in injection speed, anatomical differences in the spinal column, animal movement following injection, and differences in pulse rate and CSF stroke volume42–46. The delayed increase in viral concentration at 24-hours following injection is also noteworthy. Presumably, viral vector that enters into spinal cord tissue will be transported to nuclei for further processing47. AAV5 vectors have been shown to exhibit both anterograde and retrograde transport in the mouse brain48–50. This means that any AAV5 vector taken up by terminals in spinal tissue may be transported to the DRG or motor nuclei. As a result, this delayed increase in lumbar spinal cord viral genome concentration may be due to transport of AAV vector from caudal spinal nerves to motor nuclei of the spinal cord. The fact that this increase is not seen in the cervical and thoracic spinal level means that this is most likely due to the greater concentration of viral vectors in the lumbar CSF following injection and possible viral uptake and transport along ventral roots in the cauda equina with subsequent accumulation within motor neurons in the lumbar spinal cord. This interpretation is consistent with the localization of reporter proteins within the ventral horn following intrathecal delivery1.

Distribution of viral vectors to cervical and lumbar DRG steadily increased to Cmax in cervical DRG at 12-hours and in lumbar DRG at 24-hours post-injection. Increased variability is observed at the 24-hour time point in the lumbar DRG tissue. This is consistent with the variability that is observed in the lumbar spinal cord, most likely due to inter-injection variability. Additionally, as with lumbar spinal cord, viral genome concentration at Cmax in lumbar DRG was greater than Cmax in cervical DRG, most likely due to the proximity of the injection site. In order to reach the DRG, viral particles must diffuse through the CSF and extracellular matrices down the dorsal root sleeves to access the DRG tissue, which is in direct contact with CSF51–53 or through active retrograde transport from the spinal cord48, 50. Therefore, difference in time to Cmax can most likely be explained by the distance of the cervical and lumbar DRG to the spinal tissue. In mice, the cervical DRG lie proximal to the spinal cord in comparison to the lumbar DRG, which lie more distal to the spinal tissue53, 54. Redistribution of AAV5 particles to DRG from systemic circulation may also contribute to the gradual vector concentration rise in both cervical DRG and lumbar DRG. Arteries that provide blood flow to the DRG exhibit high permeability allowing for molecules of high molecular weight, such as AAV vector, to pass between the blood and nervous system tissue53, 55–57. In all tissues, vector genome levels significantly decreased by 48-hours, which was the last time point collected. It stands to reason that the difference in viral genomes detected between 24- and 48-hours reflects a fraction of the particles that do not contribute to gene expression. That which is detected at 48-hours likely reflects a substantial fraction that contributes to gene expression.

Our immunohistochemical analysis supports the rapid distribution of viral particles to spinal cord and DRG, as indicated by the visualization of immunolabeling of a capsid protein 30-minutes following vector delivery. These findings directly parallel what was observed in our pharmacokinetic analysis, showing that viral particles quickly distribute to all spinal levels following injection. Close association of viral vectors with the pia mater of the lumbar spinal cord and subarachnoid blood vessels is also observed 30-minutes post-injection, which parallels the rapid distribution of viral particles into lumbar tissue and systemic circulation. Given the size of AAV particles (25 nm), the observed immunolabeling most likely represents aggregates of hundreds of particles. The current state of knowledge of the cellular mechanisms of AAV-mediated transduction, which is largely based on in vitro studies, suggests that single-stranded viral genomes are released from the capsid within the cell nucleus and double-stranded viral DNA has been detected within 3-hours of AAV treatment58. However, the detection of AAV capsids following cellular entry is unlikely using these immunolabeling methods. Thus, both viral clearance and cellular entry could account for the lower levels of immunolabeling at later time points. Colocalization of AAV5-ir with macrophages in the DRG suggests that a portion of viral particle uptake into the DRG is mediated through this cell type and is a possible means of clearance from DRG tissue. This is consistent with previous studies that have shown ganglion macrophage activation following viral infection59, 60.

The current study provides pharmacokinetic analysis of AAV5 vectors following intrathecal delivery via lumbar puncture. The results of this pharmacokinetic analysis provide quantitative distribution profiles for AAV5 vectors following CSF delivery in whole blood, liver, CNS, and PNS tissue. The use of quantitative PCR to determine tissue vector concentrations is a reliable and accurate method of assessing distribution without the expression of fluorescent reporter genes. Following a single bolus injection of AAV5 vectors, distribution to all spinal levels and DRG occurs within hours post-injection. Rapid entrance of viral vector into the circulation suggests that viral vector may distribute through perivascular and subarachnoid blood vessels. The findings from this study contribute to the expanding body of knowledge surrounding AAV vectors and their applications in CSF-based gene therapies such as for chronic pain.

Supplementary Material

Table 2. Concentration analysis of AAV5 vector in all tissues and whole blood following intrathecal injection.

Table 2 includes the area under the curve (AUC), time of max concentration (Tmax), and maximum concentration (Cmax) in whole blood, liver, cervical spinal cord (CSC), thoracic spinal cord (TSC), lumbar spinal cord (LSC), cervical dorsal root ganglia (CDRG), and lumbar dorsal root ganglia (LDRG). AUC and Cmax values represented as Mean ± SEM.

| Tissue | Whole Blood | Liver | CDRG | LDRG | CSC | TSC | LSC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SEM | Mean ± SEM | Mean ± SEM | Mean ± SEM | Mean ± SEM | Mean ± SEM | Mean ± SEM | |

| AUC (vg ● h / μL) | 7.30×108 ± 1.93×108 | 1.86×109 ± 3.80×108 | 6.14×109 ± 1.90×109 | 9.12×109 ± 4.97×109 | 1.72×108 ± 7.12×107 | 5.21×108 ± 3.87×108 | 9.74×108 ± 3.83×108 |

| Tmax (hr) | 6 | 24 | 12 | 24 | 0.5 | 2 | 2 |

| Cmax (vg/μL) | 6.08×107 ± 1.53×107 | 9.04×107 ± 1.15×107 | 1.85×108 ± 5.60 ×107 | 4.03×108 ± 1.50×108 | 1.08×107 ± 5.25×106 | 6.46×107 ± 4.98×107 | 8.24×107 ± 4.67×107 |

Acknowledgments

We thank Galina Kalyuzhnaya and Kevin Kereakos-Fairbanks for their help. Images were captured using the equipment and staff support at the University of Minnesota - University Imaging Centers.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by R01DA035931 (CAF). NIDA training grant T32DA07234 supported KRP. NIDA training grant T32-DA007097 supported CDP.

Footnotes

Supporting Information: Additional representative images of AAV5 particle distribution to lumbar spinal cord at varying time points (30 min, 2 hrs, 12, hrs 24 hrs) following intrathecal injection.

References

- 1.Bey K; Ciron C; Dubreil L; Deniaud J; Ledevin M; Cristini J; Blouin V; Aubourg P; Colle MA Efficient CNS targeting in adult mice by intrathecal infusion of single-stranded AAV9-GFP for gene therapy of neurological disorders. Gene Ther 2017, 24, (5), 325–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gray SJ; Nagabhushan Kalburgi S; McCown TJ; Jude Samulski R Global CNS gene delivery and evasion of anti-AAV-neutralizing antibodies by intrathecal AAV administration in non-human primates. Gene Ther 2013, 20, (4), 450–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Homs J; Pagès G; Ariza L; Casas C; Chillón M; Navarro X; Bosch A Intrathecal administration of IGF-I by AAVrh10 improves sensory and motor deficits in a mouse model of diabetic neuropathy. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2014, 1, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hordeaux J; Dubreil L; Robveille C; Deniaud J; Pascal Q; Dequéant B; Pailloux J; Lagalice L; Ledevin M; Babarit C; Costiou P; Jamme F; Fusellier M; Mallem Y; Ciron C; Huchet C; Caillaud C; Colle MA Long-term neurologic and cardiac correction by intrathecal gene therapy in Pompe disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2017, 5, (1), 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guedon JM; Wu S; Zheng X; Churchill CC; Glorioso JC; Liu CH; Liu S; Vulchanova L; Bekker A; Tao YX; Kinchington PR; Goins WF; Fairbanks CA; Hao S Current gene therapy using viral vectors for chronic pain. Mol Pain 2015, 11, 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lentz TB; Gray SJ; Samulski RJ Viral vectors for gene delivery to the central nervous system. Neurobiol Dis 2012, 48, (2), 179–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaemmerer WF; Reddy RG; Warlick CA; Hartung SD; McIvor RS; Low WC In vivo transduction of cerebellar Purkinje cells using adeno-associated virus vectors. Mol Ther 2000, 2, (5), 446–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naso MF; Tomkowicz B; Perry WL 3rd; Strohl WR Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) as a Vector for Gene Therapy. BioDrugs 2017, 31, (4), 317–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gessler DJ; Gao G Gene Therapy for the Treatment of Neurological Disorders: Metabolic Disorders. Methods Mol Biol 2016, 1382, 429–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.During MJ; Leone P Adeno-associated virus vectors for gene therapy of neurodegenerative disorders. Clin Neurosci 1995, 3, (5), 292–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deverman BE; Ravina BM; Bankiewicz KS; Paul SM; Sah DWY Gene therapy for neurological disorders: progress and prospects. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2018, 17, (9), 641–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vulchanova L; Schuster DJ; Belur LR; Riedl MS; Podetz-Pedersen KM; Kitto KF; Wilcox GL; McIvor RS; Fairbanks CA Differential adeno-associated virus mediated gene transfer to sensory neurons following intrathecal delivery by direct lumbar puncture. Mol Pain 2010, 6, 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schuster DJ; Belur LR; Riedl MS; Schnell SA; Podetz-Pedersen KM; Kitto KF; McIvor RS; Vulchanova L; Fairbanks CA Supraspinal gene transfer by intrathecal adeno-associated virus serotype 5. Front Neuroanat 2014, 8, 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hardcastle N; Boulis NM; Federici T AAV gene delivery to the spinal cord: serotypes, methods, candidate diseases, and clinical trials. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2018, 18, (3), 293–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beutler AS AAV provides an alternative for gene therapy of the peripheral sensory nervous system. Mol Ther 2010, 18, (4), 670–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mason MR; Ehlert EM; Eggers R; Pool CW; Hermening S; Huseinovic A; Timmermans E; Blits B; Verhaagen J Comparison of AAV serotypes for gene delivery to dorsal root ganglion neurons. Mol Ther 2010, 18, (4), 715–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hinderer C; Bell P; Katz N; Vite CH; Louboutin JP; Bote E; Yu H; Zhu Y; Casal ML; Bagel J; O’Donnell P; Wang P; Haskins ME; Goode T; Wilson JM Evaluation of Intrathecal Routes of Administration for Adeno-Associated Viral Vectors in Large Animals. Hum Gene Ther 2018, 29, (1), 15–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Samaranch L; Sebastian WS; Kells AP; Salegio EA; Heller G; Bringas JR; Pivirotto P; DeArmond S; Forsayeth J; Bankiewicz KS AAV9-mediated expression of a non-self protein in nonhuman primate central nervous system triggers widespread neuroinflammation driven by antigen-presenting cell transduction. Mol Ther 2014, 22, (2), 329–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohno K; Samaranch L; Hadaczek P; Bringas JR; Allen PC; Sudhakar V; Stockinger DE; Snieckus C; Campagna MV; San Sebastian W; Naidoo J; Chen H; Forsayeth J; Salegio EA; Hwa GGC; Bankiewicz KS Kinetics and MR-Based Monitoring of AAV9 Vector Delivery into Cerebrospinal Fluid of Nonhuman Primates. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2019, 13, 47–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prasher DC; Eckenrode VK; Ward WW; Prendergast FG; Cormier MJ Primary structure of the Aequorea victoria green-fluorescent protein. Gene 1992, 111, (2), 229–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zolotukhin S; Potter M; Zolotukhin I; Sakai Y; Loiler S; Fraites TJ Jr.; Chiodo VA; Phillipsberg T; Muzyczka N; Hauswirth WW; Flotte TR; Byrne BJ; Snyder RO Production and purification of serotype 1, 2, and 5 recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors. Methods 2002, 28, (2), 158–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hylden JL; Wilcox GL Intrathecal morphine in mice: a new technique. Eur J Pharmacol 1980, 67, (2–3), 313–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pflepsen KR; Peterson CD; Kitto KF; Vulchanova L; Wilcox GL; Fairbanks CA Detailed Method for Intrathecal Delivery of Gene Therapeutics by Direct Lumbar Puncture in Mice. Methods Mol Biol 2019, 1937, 305–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Werling NJ; Satkunanathan S; Thorpe R; Zhao Y Systematic Comparison and Validation of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Methods for the Quantitation of Adeno-Associated Viral Products. Hum Gene Ther Methods 2015, 26, (3), 82–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nolan T; Hands RE; Bustin SA Quantification of mRNA using real-time RT-PCR. Nat Protoc 2006, 1, (3), 1559–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Papisov MI; Belov VV; Gannon KS Physiology of the intrathecal bolus: the leptomeningeal route for macromolecule and particle delivery to CNS. Mol Pharm 2013, 10, (5), 1522–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Papisov MI; Belov V; Fischman AJ; Belova E; Titus J; Gagne M; Gillooly C Delivery of proteins to CNS as seen and measured by positron emission tomography. Drug Deliv Transl Res 2012, 2, (3), 201–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pardridge WM CSF, blood-brain barrier, and brain drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2016, 13, (7), 963–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aspelund A; Antila S; Proulx ST; Karlsen TV; Karaman S; Detmar M; Wiig H; Alitalo K A dural lymphatic vascular system that drains brain interstitial fluid and macromolecules. J Exp Med 2015, 212, (7), 991–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma Q; Ineichen BV; Detmar M; Proulx ST Outflow of cerebrospinal fluid is predominantly through lymphatic vessels and is reduced in aged mice. Nat Commun 2017, 8, (1), 1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boulton M; Flessner M; Armstrong D; Mohamed R; Hay J; Johnston M Contribution of extracranial lymphatics and arachnoid villi to the clearance of a CSF tracer in the rat. The American journal of physiology 1999, 276, (3), R818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dupont G; Schmidt C; Yilmaz E; Oskouian RJ; Macchi V; de Caro R; Tubbs RS Our current understanding of the lymphatics of the brain and spinal cord. Clin Anat 2019, 32, (1), 117–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miura M; Kato S; von Ludinghausen M Lymphatic drainage of the cerebrospinal fluid from monkey spinal meninges with special reference to the distribution of the epidural lymphatics. Arch Histol Cytol 1998, 61, (3), 277–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sokołowski W; Barszcz K; Kupczyńska M; Czubaj N; Skibniewski M; Purzyc H Lymphatic drainage of cerebrospinal fluid in mammals – are arachnoid granulations the main route of cerebrospinal fluid outflow? Biologia 2018, 73, (6), 563–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abbott NJ; Pizzo ME; Preston JE; Janigro D; Thorne RG The role of brain barriers in fluid movement in the CNS: is there a ‘glymphatic’ system? Acta Neuropathol 2018, 135, (3), 387–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pizzo ME; Wolak DJ; Kumar NN; Brunette E; Brunnquell CL; Hannocks MJ; Abbott NJ; Meyerand ME; Sorokin L; Stanimirovic DB; Thorne RG Intrathecal antibody distribution in the rat brain: surface diffusion, perivascular transport and osmotic enhancement of delivery. J Physiol 2018, 596, (3), 445–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahmed SS; Li J; Godwin J; Gao G; Zhong L Gene transfer in the liver using recombinant adeno-associated virus. Curr Protoc Microbiol 2013, Chapter 14, Unit14D.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Srivastava A In vivo tissue-tropism of adeno-associated viral vectors. Curr Opin Virol 2016, 21, 75–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zincarelli C; Soltys S; Rengo G; Rabinowitz JE Analysis of AAV serotypes 1–9 mediated gene expression and tropism in mice after systemic injection. Mol Ther 2008, 16, (6), 1073–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sands MS AAV-Mediated Liver-Directed Gene Therapy. Methods Mol Biol 2011, 807, 141–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Herzog RW Hepatic AAV gene transfer and the immune system: friends or foes? Mol Ther 2010, 18, (6), 1063–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shafer SL; Eisenach JC; Hood DD; Tong C Cerebrospinal fluid pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of intrathecal neostigmine methylsulfate in humans. Anesthesiology 1998, 89, (5), 1074–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hocking G; Wildsmith JA Intrathecal drug spread. Br J Anaesth 2004, 93, (4), 568–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hsu Y; Hettiarachchi HDM; Zhu DC; Linninger AA The Frequency and Magnitude of Cerebrospinal Fluid Pulsations Influence Intrathecal Drug Distribution: Key Factors for Interpatient Variability. Anesthesia & Analgesia 2012, 115, (2), 386–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stockman HW Effect of anatomical fine structure on the dispersion of solutes in the spinal subarachnoid space. J Biomech Eng 2007, 129, (5), 666–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Friese S; Hamhaber U; Erb M; Kueker W; Klose U The influence of pulse and respiration on spinal cerebrospinal fluid pulsation. Invest Radiol 2004, 39, (2), 120–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nonnenmacher M; Weber T Intracellular Transport of Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus Vectors. Gene Ther 2012, 19, (6), 649–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aschauer DF; Kreuz S; Rumpel S Analysis of transduction efficiency, tropism and axonal transport of AAV serotypes 1, 2, 5, 6, 8 and 9 in the mouse brain. PLoS One 2013, 8, (9), e76310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Foust KD; Flotte TR; Reier PJ; Mandel RJ Recombinant adeno-associated virus-mediated global anterograde delivery of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor to the spinal cord: comparison of rubrospinal and corticospinal tracts in the rat. Hum Gene Ther 2008, 19, (1), 71–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Salegio EA; Samaranch L; Kells AP; Mittermeyer G; San Sebastian W; Zhou S; Beyer J; Forsayeth J; Bankiewicz KS Axonal transport of adeno-associated viral vectors is serotype-dependent. Gene Ther 2013, 20, (3), 348–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Joukal M; Klusakova I; Dubovy P Direct communication of the spinal subarachnoid space with the rat dorsal root ganglia. Ann Anat 2016, 205, 9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brierley JB The penetration of particulate matter from the cerebrospinal fluid into the spinal ganglia, peripheral nerves, and perivascular spaces of the central nervous system. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1950, 13, (3), 203–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ahimsadasan N; Kumar A Neuroanatomy, Dorsal Root Ganglion. 2018. [PubMed]

- 54.Watson C; Paxinos G; Puelles L; ScienceDirect, The mouse nervous system. Amsterdam ; Boston: : Elsevier Academic Press: Amsterdam ; Boston, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sapunar D; Kostic S; Banozic A; Puljak L, Dorsal root ganglion – a potential new therapeutic target for neuropathic pain. In J Pain Res, 2012; Vol. 5, pp 31–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jimenez-Andrade JM; Herrera MB; Ghilardi JR; Vardanyan M; Melemedjian OK; Mantyh PW, Vascularization of the dorsal root ganglia and peripheral nerve of the mouse: Implications for chemical-induced peripheral sensory neuropathies. In Mol Pain, 2008; Vol. 4, p 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abram SE; Yi J; Fuchs A; Hogan QH Permeability of injured and intact peripheral nerves and dorsal root ganglia. Anesthesiology 2006, 105, (1), 146–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dhungel BP; Bailey CG; Rasko JEJ Journey to the Center of the Cell: Tracing the Path of AAV Transduction. Trends Mol Med 2021, 27, (2), 172–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mori I; Goshima F; Koshizuka T; Imai Y; Kohsaka S; Koide N; Sugiyama T; Yoshida T; Yokochi T; Kimura Y; Nishiyama Y Iba1-expressing microglia respond to herpes simplex virus infection in the mouse trigeminal ganglion. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 2003, 120, (1), 52–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mori I; Imai Y; Kohsaka S; Kimura Y Upregulated expression of Iba1 molecules in the central nervous system of mice in response to neurovirulent influenza A virus infection. Microbiol Immunol 2000, 44, (8), 729–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.