Introduction

The current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has the worst affected the entire population on the earth (1, 2). This is currently a major concern for the global health care system, as declared by the World Health Organization (WHO). Ample pieces of evidences suggested the idiopathic association of the SARS-CoV-2 with many diseases in COVID-19 cases. Given the aberrant immunopathology of COVID-19, a single approach may not be sufficient to control the disease effectively. Severely infected patients displaying acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) need additional modalities for their management (3). This could be due to the host’s epigenetic programming of infected macrophages, which may be responsible for negative prognosis and inadequate response to the current therapeutic regimen for controlling disease manifestation.

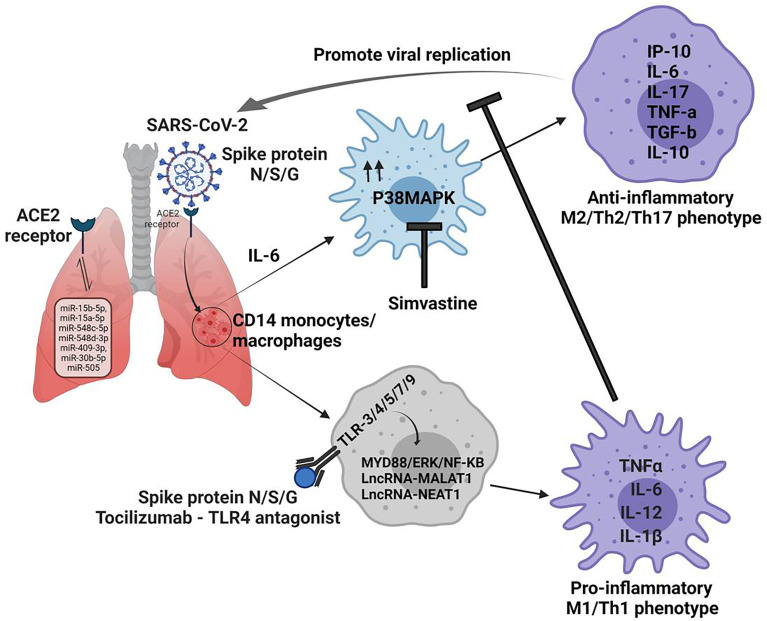

SARS-CoV-2 enters the host cells via ACE-II receptor and triggers the secretion of the copious amount of IL-6;promote pulmonary fibrosis and Th2/17 programming of lungs, leading to severe lung infection in COVID-19 patients. SARS-CoV-2 interacts and tweaks all kind of cells like epithelium, macrophages, dendritic cells, and T cells and exploit them in a way that supports its replication for progression of the disease.

Out of these, uncontrolled activation of macrophages (also known as double edge component of immunity) leads to Macrophage activation syndrome which is responsible for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and subsequent death of COVID-19 patients (4, 5). This is mainly characterized by the increased infiltration of committed macrophages and their Th2/Th17 programming leading to mortality. Once derailed, hyperactive macrophages secrete high levels of IFN‐γ, IP-10 (IP‐10), IL-6, IL-17, TNF-α along with TGF-β and IL-10/23, leading to the Th2/Th17 programming in the infected lungsof severe cases of COVID-19 (6).

At molecular levels, this is accompanied by the activation of inflammasome pathways which are important forTh17 programming of tissue. Activated CD14+ monocytes phagocytose dead neutrophils and promotes NETosis in the lung. This promotes Th2 bias, decreases lymphocyte/neutrophils ratio and increases the risk of COVID-19 patients for death. Given this, in situ reprogramming Th2/Th17 programmed macrophages towards their M1 phenotype is expected to afford protective immunity in COVID-19 cases (4) as shown in Figure 1 .

Figure 1.

Non-coding RNAs regulates macrophage plasticity during the pathogenesis of Covid 19 disease. 1. N/S/G spike proteins bind to ACE2 receptors on lung cells and determine the entry of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. 2. miRNA can be direct targets since they can regulate the expression of ACE2 in various organs. 3. Infection produces an copius amount of IL-6, which drives the fate of CD14 monocytes/macrophages towards M2 phenotype via MAPK signaling, which promotes viral replication. 4. In view of this virus eliminating inflammatory niche could be achievd by promting M1 phenotype in TLR depenedent MYD88/ERK/NF-Kb pathway. 5. This could be fosterd by application of MAPK inhibitors like simvastatin in conjuction of TLR antagonist which can help immune cells to curb SARS-CoV-2 in the host effectively.

Committed macrophages rely upon Toll-like Receptors (TLRs) and associated pathways, the guardian for Th1/2/17 effector responsesduring any infection, including SARS-CoV-2 (7). Among various TLRs on macrophages, TLR-4, 5, 3, 7,and 9 actively sense spike proteins (N, S or G) or mRNA of NSP-10, S2, and E proteins of SARS-CoV-2 and promote M1 polarization of macrophages (8). Apart from ACE-2, the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 uses TLR-2, 4 and 5 signaling pathways also via MyD88 and triggers Th1 effector response through NF-κB and ERK signaling cascade (9). Given this, tweaking TLR signaling like TLR5 can restore or promote Th1 response in derailed macrophages in COVID-19 patients. Indeed, a recent report suggests that conjunction therapy with antivirals and TLR-7 agonists may benefit patients (7) who are believed to harbor Th2/17 programmed macrophage. Similarly, the application of Tocilizumab and TLR-4 antagonists is expected to promote M1 re-polarization of derailed macrophage in patients with severe disease displaying ARDS.

Several intracellular pathways like nk-kb/STAT/and p38MAPK are essential for the immune polarization of macrophages during infection and cancer. p38MAPK pathway is one of the host factors implicated in lung and heart injury in COVID-19 patients (10, 11). P38MPAK landscape is decisive for sterile inflammatory responses, desmoplastic reactions, T cell exhaustion, and epigenetic programming of severely infected COVID-19 cases. P38 MAPK controls macrophage plasticity via promoting ER stress, unfolded protein responses, and glucose intolerance which are associated with energy imbalance in the infected host. Since SARS-CoV-2 directly up-regulates p38 activity for promoting its replication in epithelium and macrophages (12), we presume that hyper-activation of p38MAPK may contribute to Th2 bias in these macrophages and aberrant inflammation in the lung.

SARS-CoV-2 regulates P38MAPK signaling in multiple ways to support its replication, one of the prominent mechanisms is downregulation of ACE2 activity, which negatively regulate expression of ICAM-1 (intercellular adhesion molecule-1), VCAM-1 (vascular cell adhesion molecule-1) (13) and NF-KB activation (14) leading to Th2 bias in the host. Loss of ACE2 function leads to enhanced concentration of intracellular Angiotensin 2, which directly activates P38MAPK (10) in the host, leading to Th17 response in the host (15). This progress to ARDS (acute respiratory distress syndrome) and myocarditis are primary reasons for death in critically infected patients (16). Several studies with severely infected patients suggested that SARS-CoV-2 promotes degradation of DUSPs (dual-specificity phosphatase) transcripts, this promotes P38MAPK hyperactivation (17) in the host. Besides ACE2 and DUSPs, SARS-CoV-2 also triggers TAB1 (TGF-β activated kinase 1 (MAP3K7)-bindingprotein 1) mediated P38A auto-phosphorylation and P38MAPK hyper-activation, adding to the reason for increased MAPK activity in the infected cells. Studies with several MAPK inhibitors like SB203580 (18), Losmapimod (19) and Dilmapimod (20) have shown promising results in mitigating pathogenic inflammation in COPD patients and advocated their potential application in hashing SARS-CoV-2 burden. Therefore targeting p38MAPK could be of direct interest in controlling viral burden and M1 retuning of infected macrophages viz-a-viz mitigating T- cell exhaustion in patients.

Apart from activating several cytoplasmic signaling pathways, p38MAPK also activate the expression of various transcription factors. Recent studies have provided compelling evidence that activated MAPK influence the expression of differentially expressed mi/lncRNAs,which are important for sterile inflammation and M2/Th2 polarization of macrophages. Most intriguingly, the lncRNA landscape is proposed as a prognostic factor responsible for the severity of COVID-19 cases (21). Among pool of miRNAs; miR-15b-5p, miR-15a-5p, miR-548c-5p, miR-548d-3p, miR-409-3p, miR-30b-5p and miR-505 have been validated as potent targets for controlling SARS-CoV-2 infection (22). These miRNAs regulate the expression of ACE-2 in various organs, including the kidney, heart, blood vessels, and lungs which are important for COVID-19 pathophysiology (23). Other than this, several LncRNA like WAKMAR2, EGOT, EPB41L4A-AS1, ENSG00000271646, MALAT1 and NEAT1 are known to contribute to skewing the immune response against SARS-CoV-2 infection (24, 25).

Overexpression of NEAT1 stabilizes the mature caspase-1 to promote interleukin-1β production and modulate inflammasome activation (26), which is associated with Th2/17 programming of immune cells like macrophages. MALAT1 promotes Th1 effector responses and apoptosis in airway epithelial cells conditioned DCs and cardiac cells (6, 27) via miR-125b and p38MAPK/NF-κB pathways (7). This loop is potentially involved in the maturation and pro-inflammatory programming of CD14+/Gr-1-/iNOs+ M1 macrophages, which is essential for the adaptive immunity of the host.

Major Perspective

Lowering p38MAPK with specific inhibitors like simvastatinin conjunction with TLR antagonist and Tocilizumab is anticipated to be a prudent approach for augmenting immunity of COVID-19 infected cases. The uncontrolled systemic inflammatory response and cytokine storm is the main mechanism of ARDS caused by the excessive release of interferon, interleukins, TNF-α and chemokines. Thus, it was proposed that statins (28), which are well known for their anti-inflammatory effects,could treat MERS-CoV infection and perhaps COVID-19 patients (29) as well. However, statins in COVID-19 patients sometimes increase the risk and severity of myopathies and acute kidney injury (29). On the other hand, statin therapy increases liver enzymes, leading to severe complications in the COVID-19 patients (30). Thus, guideline-directed statin therapy in COVID-19 patients is necessary.

It was proposed that early intervention with interleukin-6 receptor blockade by Tocilizumab could effectively control the progression to hypoxemic respiratory failure or death of severe COVID-19 patients (31). There are conflicting results obtained for tocilizumab in COVID-19 patients. Several treatment lines suggest that using a monoclonal antibody against IL-6 is an attractive strategy to manage severe COVID-19 as Tocilizumab has the potential to reduce mortality and the need for mechanical ventilation (32, 33). However, a clinical trial on 243 patients revealed that tocilizumab was not effective for preventing death in moderately ill hospitalized COVID-19 patients (34). In a recent study on the hospitalized COVID-19 patients, although tocilizumab reduced the progression to the composite outcome of mechanical ventilation, however could not improve their survival (35). Besides, this targeting miRNA which modulates the expression of ACE2 receptor activities, can also be of significant value to currently explored therapeutics/interventions. This conjuction approach is expected to enhance the sensitivity of infected host cells for currently employed drugs. Taken together, above interventions would help in curbing the SARS-CoV-2 virus for the effective management of COVID-19 disease.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and conceiving of idea, HP. Writing, AJ, RR, MW, and HP. Resources, AJ, MH, HP, and US. Editing of manuscript, HP. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by the Department of Health and Research, Government of India (GIA/2020/000414) to HP.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1. Asrani P, Eapen MS, Hassan MI, Sohal SS. Implications of the Second Wave of COVID-19 in India. Lancet Respir Med (2021) 9(9):e93–4. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00312-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Naqvi AAT, Fatima K, Mohammad T, Fatima U, Singh IK, Singh A, et al. Insights Into SARS-CoV-2 Genome, Structure, Evolution, Pathogenesis and Therapies: Structural Genomics Approach. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA)-Mol Basis Dis (2020) 1866(10):165878. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2020.165878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. De Maio A, Hightower LE. COVID-19, Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS), and Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy (HBOT): What Is the Link? Cell Stress Chaperones (2020) 25:717–20. doi: 10.1007/s12192-020-01121-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Toor D, Jain A, Kalhan S, Manocha H, Sharma VK, Jain P, et al. Tempering Macrophage Plasticity for Controlling SARS-CoV-2 Infection for Managing COVID-19 Disease. Front Pharmacol (2020) 11:570698. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.570698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Netea MG, Rovina N, Akinosoglou K, Antoniadou A, Antonakos N, et al. Complex Immune Dysregulation in COVID-19 Patients With Severe Respiratory Failure. Cell Host Microbe (2020) 27(6):992–1000.e1003. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, Manson JJ, et al. COVID-19: Consider Cytokine Storm Syndromes and Immunosuppression. Lancet (2020) 395(10229):1033–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Onofrio L, Caraglia M, Facchini G, Margherita V, Placido S, Buonerba C. Toll-Like Receptors and COVID-19: A Two-Faced Story With an Exciting Ending. Future Sci OA (2020) 6(8):FSO605. doi: 10.2144/fsoa-2020-0091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Choudhury A, Das NC, Patra R, Mukherjee S. In Silico Analyses on the Comparative Sensing of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA by the Intracellular TLRs of Humans. J Med Virol (2021) 93(4):2476–86. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sariol A, Perlman S. SARS-CoV-2 Takes Its Toll. Nat Immunol (2021) 22(7):801–2. doi: 10.1038/s41590-021-00962-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grimes JM, Grimes KV. P38 MAPK Inhibition: A Promising Therapeutic Approach for COVID-19. J Mol Cell Cardiol (2020) 144:63–5. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2020.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hemmat N, Asadzadeh Z, Ahangar NK, Alemohammad H, Najafzadeh B, Derakhshani A, et al. The Roles of Signaling Pathways in SARS-CoV-2 Infection; Lessons Learned From SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV. Arch Virol (2021) 166(3):675–96. doi: 10.1007/s00705-021-04958-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Scott AJ, O'Dea KP, O'Callaghan D, Williams L, Dokpesi JO, Tatton L, et al. Reactive Oxygen Species and P38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Mediate Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha-Converting Enzyme (TACE/ADAM-17) Activation in Primary Human Monocytes. J Biol Chem (2011) 286(41):35466–76. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.277434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang Q, Yang M, Xiao Y, Han Y, Yang S, Sun L. Towards Better Drug Repositioning: Targeted Immunoinflammatory Therapy for Diabetic Nephropathy. Curr Med Chem (2021) 28(5):1003–24. doi: 10.2174/0929867326666191108160643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yu X, Cui L, Hou F, Liu X, Wang Y, Wen Y, et al. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2-Angiotensin (1-7)-Mas Axis Prevents Pancreatic Acinar Cell Inflammatory Response via Inhibition of the P38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase/Nuclear Factor-κB Pathway. Int J Mol Med (2018) 41(1):409–20. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zarubin T, Han J. Activation and Signaling of the P38 MAP Kinase Pathway. Cell Res (2005) 15(1):11–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, Jiang L, Song J. Correction to: Clinical Predictors of Mortality Due to COVID-19 Based on an Analysis of Data of 150 Patients From Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med (2020) 46(6):1294–7. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06028-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Goel S, Saheb Sharif-Askari F, Saheb Sharif Askari N, Madkhana B, Alwaa AM, Mahboub B, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Switches 'On' MAPK and NFκB Signaling via the Reduction of Nuclear DUSP1 and DUSP5 Expression. Front Pharmacol (2021) 12:631879. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.631879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cheng Y, Sun F, Wang L, Gao M, Xie Y, Sun Y, et al. Virus-Induced P38 MAPK Activation Facilitates Viral Infection. Theranostics (2020) 10(26):12223–40. doi: 10.7150/thno.50992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Barbour AM, Sarov-Blat L, Cai G, Fossler MJ, Sprecher DL, Graggaber J, et al. Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Losmapimod Following a Single Intravenous or Oral Dose in Healthy Volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol (2013) 76(1):99–106. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Christie JD, Vaslef S, Chang PK, May AK, Gunn SR, Yang S, et al. A Randomized Dose-Escalation Study of the Safety and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of the P38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Inhibitor Dilmapimod in Severe Trauma Subjects at Risk for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Crit Care Med (2015) 43(9):1859–69. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cheng J, Zhou X, Feng W, Jia M, Zhang X, An T, et al. Risk Stratification by Long Non-Coding RNAs Profiling in COVID-19 Patients. J Cell Mol Med (2021) 25(10):4753–64. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.16444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fulzele S, Sahay B, Yusufu I, Lee TJ, Sharma A, Kolhe R, et al. COVID-19 Virulence in Aged Patients Might Be Impacted by the Host Cellular MicroRNAs Abundance/Profile. Aging Dis (2020) 11(3):509–22. doi: 10.14336/AD.2020.0428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lu D, Chatterjee S, Xiao K, Riedel I, Wang Y, Foo R, et al. MicroRNAs Targeting the SARS-CoV-2 Entry Receptor ACE2 in Cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol (2020) 148:46–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2020.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vishnubalaji R, Shaath H, Alajez NM. Protein Coding and Long Noncoding RNA (lncRNA) Transcriptional Landscape in SARS-CoV-2 Infected Bronchial Epithelial Cells Highlight a Role for Interferon and Inflammatory Response. Genes (Basel) (2020) 11(7):1–19. doi: 10.3390/genes11070760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mukherjee S, Banerjee B, Karasik D, Frenkel-Morgenstern M. mRNA-lncRNA Co-Expression Network Analysis Reveals the Role of lncRNAs in Immune Dysfunction During Severe SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Viruses (2021) 13(3):1–13. doi: 10.3390/v13030402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang P, Cao L, Zhou R, Yang X, Wu M. The lncRNA Neat1 Promotes Activation of Inflammasomes in Macrophages. Nat Commun (2019) 10(1):1495. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09482-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li Z, Zhang Q, Wu Y, Hu F, Gu L, Chen T, et al. lncRNA Malat1 Modulates the Maturation Process, Cytokine Secretion and Apoptosis in Airway Epithelial Cell-Conditioned Dendritic Cells. Exp Ther Med (2018) 16(5):3951–8. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.6687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yuan S. Statins may Decrease the Fatality Rate of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Infection. MBio (2015) 6(4):e01120–01115. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01120-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dashti-Khavidaki S, Khalili H. Considerations for Statin Therapy in Patients With COVID-19. Pharmacotherapy (2020) 40(5):484–6. doi: 10.1002/phar.2397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Guan W-j, Ni Z-y, Hu Y, Liang W-h, Ou C-q, He J-x, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med (2020) 382(18):1708–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Somers EC, Eschenauer GA, Troost JP, Golob JL, Gandhi TN, Wang L, et al. Tocilizumab for Treatment of Mechanically Ventilated Patients With COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis (2021) 73(2):e445–54. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Aziz M, Haghbin H, Abu Sitta E, Nawras Y, Fatima R, Sharma S, et al. Efficacy of Tocilizumab in COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Med Virol (2021) 93(3):1620–30. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gupta S, Wang W, Hayek SS, Chan L, Mathews KS, Melamed ML, et al. Association Between Early Treatment With Tocilizumab and Mortality Among Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19. JAMA Internal Med (2021) 181(1):41–51. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.6252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stone JH, Frigault MJ, Serling-Boyd NJ, Fernandes AD, Harvey L, Foulkes AS, et al. Efficacy of Tocilizumab in Patients Hospitalized With Covid-19. N Engl J Med (2020) 383(24):2333–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2028836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Salama C, Han J, Yau L, Reiss WG, Kramer B, Neidhart JD, et al. Tocilizumab in Patients Hospitalized With Covid-19 Pneumonia. N Engl J Med (2021) 384(1):20–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2030340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]