Abstract

While the recent FDA approval of six new antibody drug conjugates (ADCs) is promising, attrition of ADCs during clinical development is still high. The inherent complexity of ADCs is a double-edged sword, providing opportunities to perfect therapeutic action while also increasing confounding factors in therapeutic failures. ADC design drives their pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, requiring deeper analysis than commonly used Cmax and area under curve (AUC) metrics to scale dosing to the clinic. Common features for current FDA-approved ADCs targeting solid tumors include humanized IgG1 antibody domains, highly expressed tumor receptors, and large antibody doses. The potential consequences of these shared features for the clinical pharmacokinetics and mechanism of action are discussed, highlighting key design aspects for successful solid tumor ADCs.

Keywords: Translational Pharmacokinetics, Intratumor Drug Distribution, Immunotherapy

Complexities and Challenges of ADC Development

Antibody drug conjugates (ADCs) are entering an unprecedented period of success with the FDA approval of six additional ADCs in the past two years. ADCs are complex biologics made up of three main components: an antibody backbone, the payload, and a connecting linker. The ADC structure is highly customizable, offering opportunities to tailor an ADC to a particular target, but also increasing the complexity of their design. As of 2021, six ADCs are indicated for hematological tumors and four ADCs for solid tumors. However, before 2019, only a single ADC was approved for solid tumors, and many have failed during clinical development.

Quantitative pharmacology approaches have a critical role to play given the complex and often counterintuitive ADC pipeline. Many drugs that appear efficacious in vitro and in preclinical models ultimately fail in clinical trials. Perhaps even more consequential, evidence suggests some drugs that fail traditional in vitro and preclinical tests could potentially be successful in the clinic. As anecdotes of some poor preclinical results with successful ADCs, Trodelvy potency is difficult to quantify in vitro due to the role of hydrolyzed drug(3), and Enhertu shows no response in a nude mouse model using a syngeneic line despite efficacy in immunocompetent mice(4). Understanding the similarities between currently approved solid tumor ADCs can yield insights toward rational solid tumor ADC design and continued clinical success.

Recent FDA-approved ADCs follow three design criteria

The three recently approved solid tumor ADCs highlight important design criteria. While several components of the ADC show significant variability, the shared features are noteworthy. The structure of the four FDA-approved ADCs for solid tumors are very different and include diverse linker types (cleavable vs. non-cleavable, different mechanisms of release, varying stability), specific and non-specific conjugation, different targets, cancer types, and drug to antibody ratios (DARs). Intriguingly, the three common features between these therapies are 1) highly expressed targets (105 to 106 receptors/cell), 2) high antibody doses (3.6 mg/kg or larger doses over a 3-week period), and 3) an IgG1 isotype antibody backbone (Table 1). This last feature provides long circulation half-life in addition to providing the greatest potential for immune response through Fc interactions.

Table 1.

Structural components for the FDA approved ADCs for solid tumor indications. These ADCs display differences in selected payload, linker, DAR, and conjugation. In contrast, the antibody isotype, large doses, and high expression target are shared for these therapies.

| FDA approved ADCs for solid tumors (year) | Kadcyla (2013) | Padcev (2019) | Enhertu (2019) | Trodelvy (2020) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Target | Her2 | Nectin-4 | Her2 | Trop-2 |

| Antibody isotype | IgG1 | IgG1 | IgG1 | IgG1 |

| Clinical dose over 21 days* (mg/kg) | 3.6 | 3.75 | 5.4 | 20 |

| Linker | Non-cleavable (SMCC) | Cleavable (VC) | Cleavable (tetrapeptide) | Cleavable (CL2A) |

| Payload | Microtubule inhibitor (DM1) | Microtubule inhibitor (MMAE) | Topoisomerase inhibitor (Exatecan derivative) | Topoisomerase inhibitor (SN-38) |

| Drug to antibody ratio | 3.5 | 4 | 8 | 7.6 |

| ADC clearance half-life (days) | 4 | 3.4 | 5.7 | 0.67 |

| Payload clearance half-life (days) | Not measured | 2.4 | 5.8 | 0.75 |

- Kadcyla, 3.6 mg/kg Q3W; Padcev, 1.25 mg/kg D1, D8, D15 of 28 day cycle; Enhertu, 5.4 mg/kg Q3W; Trodelvy, 10 mg/kg D1 and D8 of 21 day cycle

The three shared features have a significant impact on the drug delivery and distribution. In fact, because ADCs use known cytotoxic payloads (e.g. microtubule inhibitors) with known targeting agents (antibodies), a key feature to their clinical success is delivery – targeting efficacious amounts of payload for each tumor cell at tolerable doses. These shared design features each have individual impacts on the tumor targeted delivery of payload.

High Target Expression

Her2, Nectin-4, and Trop-2 are highly expressed tumor antigens with greater than 105 receptors per tumor cell and significantly lower healthy tissue expression. A high expression target can provide a greater therapeutic window due to a larger target sink. Since drug delivery to healthy tissue is often more efficient than delivery to tumors, a high antibody dose with a high expression tumor target may quickly saturate uptake in lower expression healthy tissue while still maximizing uptake in the tumor. The payload toxicity and/or DAR can then be modified to ensure delivery to tumor cells above a therapeutic threshold while maintaining a subtherapeutic threshold in healthy tissue (to avoid target-mediated healthy tissue toxicity). In contrast, targeting a lower expressed tumor antigen requires a more potent payload to achieve a therapeutic concentration in targeted cells. Increasing payload potency typically results in higher toxicity, lowering the tolerated ADC dose. These lower ADC doses reduce tumor uptake but may not decrease healthy tissue uptake by the same amount (e.g. if target-mediated healthy tissue uptake remains saturated), potentially reducing the therapeutic index. Notably, this trade-off is very different than small molecule drugs, which often equilibrate with the plasma concentration such that a lower dose results in lower healthy tissue exposure. In stark contrast to small molecules, lower doses of more potent ADCs can limit tumor penetration, lowering efficacy more than toxicity.

High Antibody Doses

Developing ADCs against solid malignancies is difficult since solid tumors suffer from leaky, tortuous blood vessels and poor lymphatic drainage, leading to negligible convection and elevated interstitial pressure(15). These features coalesce to form an adverse environment for the delivery of large biologics. The most direct way of increasing both antibody delivery and tissue penetration is to administer higher doses of the antibody like unconjugated antibodies such as trastuzumab and cetuximab (~4 to 14 mg/kg). This is the second shared feature among currently approved agents.

Kadcyla was the only FDA-approved ADC for solid tumors for many years, having achieved FDA approval status in 2013 with the use of Human IgG1 scaffold, a moderate DAR (3.5 drugs per antibody), non-cleavable linker, and a potent microtubule inhibitor. Despite this success, it is difficult to extrapolate from a single example to provide guidance for designing new agents. In particular, the success of Herceptin, the antibody backbone of Kadcyla, makes it challenging to separate the role of the payload, antibody, and any potential synergy between them in the clinic(17). With the approval of new agents that do not have apparent activity from antibody receptor blockade alone, the success associated with high dosing of these agents appears to extend beyond receptor signaling blockade. Current solid tumor therapeutics dose more antibody over a three-week period than Kadcyla and significantly more than many approved hematological ADCs (e.g. ~0.02 and 0.15 mg/kg for Besponsa and Zynlonta), ranging from 3.75 to 20 mg/kg (Table 1). These doses are necessary to overcome high expression and efficient internalization needed to deliver payload into the cell.

Other Design Criteria

Payload selection is crucial to ADC development. The payload directly impacts the therapeutic window, which often plays a major role in clinical ADC attrition. Today most payloads belong to one of three classes: 1) DNA damage inducers, 2) microtubule inhibitors, and 3) topoisomerase inhibitors. DNA damaging payloads are often extremely potent (calicheamicin, pyrrolobenzodiazepine PBD) while microtubule (DM4, MMAE) and topoisomerase (exatecan, SN-38) inhibitors are more moderate. Identifying optimal payloads requires case by case analysis. A lower potency payload affords a greater maximum tolerated dose (MTD). However, for indications with lower antigen presentation, the amount of payload delivered might not exceed the therapeutic threshold, and so higher potency payloads would be necessary. In addition to in vitro potency, recent studies have identified multiple payloads as immunogenic cell death (ICD) inducing agents(4, 19, 20). The ability of some payloads to cause an immune response after cell death is a new avenue of research that may have a broad impact on next generation ADC payload selection, although the role of ICD versus IgG1 effector function or other mechanisms is currently unclear((4, 17, 19, 21) and Outstanding Questions).

Outstanding questions box.

What is the relationship between the different mechanisms of ADC action (payload delivery, receptor modulation, and Fc effector functions) and which are driving clinical responses?

Is an anti-tumor immune response from ADC therapy required to surpass current standard-of-care or simply beneficial for therapeutic response?

What is the potential synergy between immune checkpoint inhibition and ADCs? Is this driven by the payloads, Fc effector function, bystander effects on immune cells, or a combination?

Is the success of ADCs against high expression targets due to a lower risk of downregulation, potential for high density Fc-effector function, and/or a greater therapeutic window?

Why are mouse cells less sensitive to clinically approved ADCs when compared to human cancer cells, and how can this be addressed to better replicate the therapeutic window for preclinical development?

What metrics best measure and quantify distribution for clinical tumor samples consisting of complex tissue architecture (e.g. extensive stromal tissue)?

While target expression, antibody dose, and antibody isotype are common to currently approved ADCs in solid tumors, there are important differences in the approved designs. For example, each linker is unique - some approved linkers are cleavable while others are non-cleavable. These differences can have a significant impact on the resulting distribution as well as treatment tolerability. Non-cleavable linkers are generally more stable in the plasma, although advances in linker chemistry have made significant improvements (e.g. Kadcyla’s non-cleavable linker loses 18.4% of the DM1 payload in 4 days(23) versus Enhertu’s cleavable linker loses 2.1% of its payload in 21 days(24)). Even if a linker can reduce ADC payload loss in circulation, a more difficult challenge is encountered after systemic uptake and degradation of the ADC itself. Since most of the ADC dose does not reach the tumor, the ADC will be metabolized somewhere else in the body, releasing the payload in an undesired location. The payload, linker, and conjugation site can all influence where non-specific release occurs in the body and the dose-limiting toxicity.

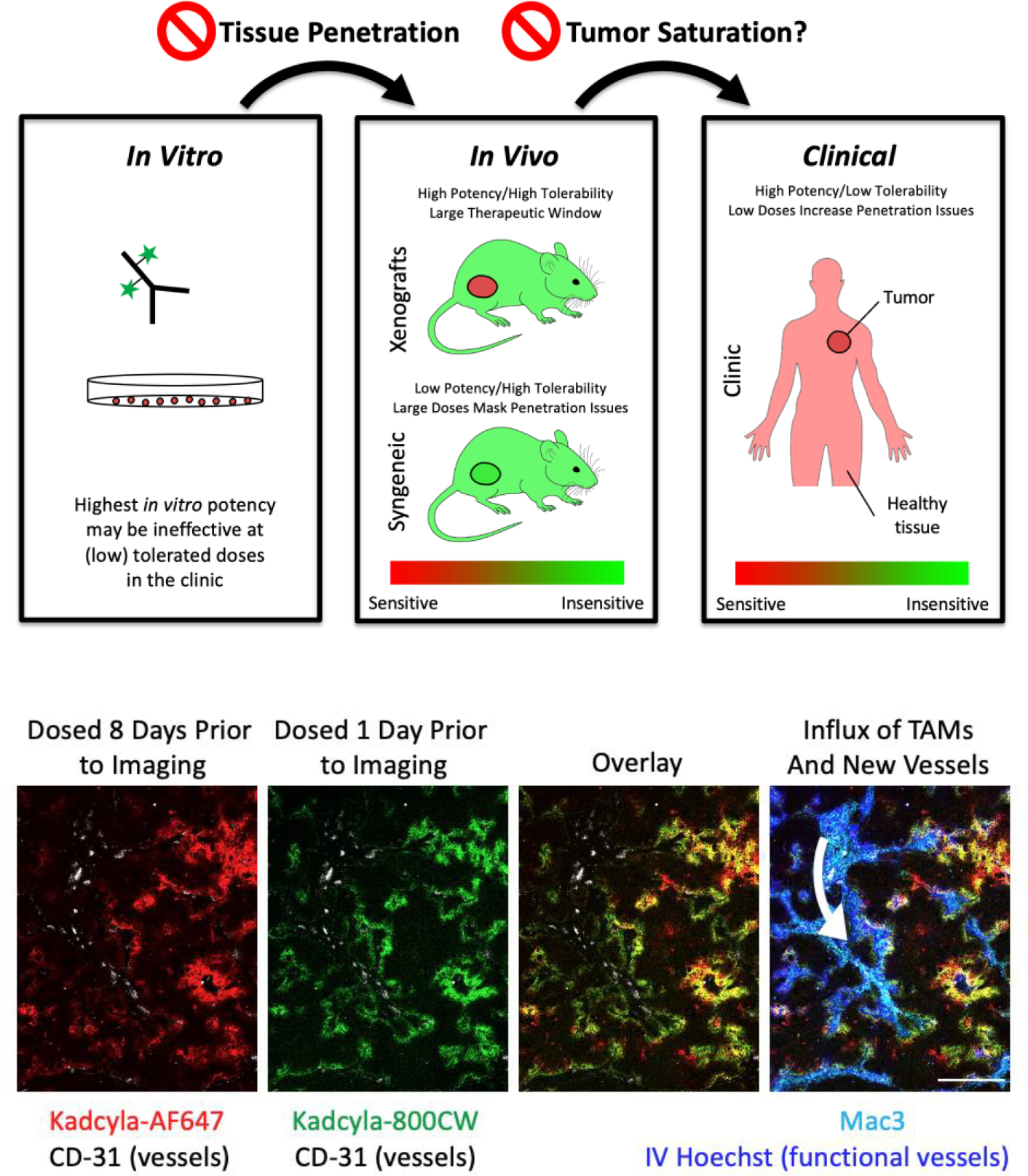

The current FDA approved drugs show variability across several of these other design features, demonstrating a need to individualize ADCs for their specific target. However, the similarities in dosing and target expression, combined with preclinical evidence, suggest that tissue penetration and tumor saturation are key components to solid tumor efficacy. Although tumor tissue penetration and saturation are linked to traditional measures of pharmacokinetics, such as Cmax and exposure (area under the curve, or AUC), the unique distribution of ADCs may limit the association between AUC and efficacy often found with small molecule chemotherapeutics(25, 26). Advancing ADCs to clinical trials without fully delineating tumor tissue penetration and saturation characteristics may be a significant factor in clinical attrition. In short, we need to move beyond Cmax and AUC and account for tumor tissue penetration and tumor saturation to design the next generation of ADCs (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1. Scaling ADCs to the Clinic:

A) Many reasons exist for the failure of animal models to capture clinical results in drug development. In the case of ADCs, two specific reasons include tissue penetration and tumor saturation. In vitro assays do not capture delivery issues, and highly potent compounds selected in vitro often increase toxicity, lowering tolerable doses in vivo. The lower doses result in less tissue penetration, reducing efficacy in vivo (left arrow). Mice often tolerate higher doses than humans, and mouse tumor lines are sometimes less sensitive to the payload. Both of these factors can result in higher doses administered in preclinical animal models (better tissue penetration), which sometimes results in tumor saturation. Notably, trends identified using saturating doses can be the opposite of those at subsaturating doses commonly encountered in the clinic (right arrow), making it critical to understanding the saturation level in preclinical models and predicted level in the clinic. B) Nude mice bearing NCI-N87 xenografts were administered 1.2 mg/kg of AlexaFluor647 labeled Kadcyla on Day 0 and 1.2 mg/kg of IRDye800CW labeled Kadcyla on Day 7. Tumors were resected on Day 8, frozen in OCT, processed and imaged. Hoechst 33342 was injected 5 min before tumor resection to label functional vasculature. The first dose (red) shows strong colocalization with the second dose (green). A couple collapsed vessels were seen (data not shown) where perivascular signal from the first dose lacked Hoechst or signal from the second dose. Regions with a large number of macrophages (cyan) and functional vessels (blue) showed slightly stronger staining for the second dose, consistent with neovasculature forming (white arrow) following treatment(13).

Tumor Penetration

Systemic pharmacokinetics, toxicity, and efficacy are key metrics measured during drug development. Toxicity and pharmacokinetics are used to quickly eliminate poor candidates at an early stage. In contrast, testing efficacy requires a more intensive effort, and tissue penetration can play a significant role in response(27). However, tumor penetration is not routinely assessed with ADCs, even though tumor distribution is demonstrated to vary widely. Recent publications demonstrate the perivascular distribution of ADCs and the negative impact this limited penetration has on efficacy(13, 22). For example, by co-administering unconjugated antibody with an ADC, the tissue penetration of the ADC can be increased. As a result, a larger fraction of cells receives the payload, reducing tumor growth when compared to the ADC or antibody alone. Likewise, other methods have been developed to improve tissue penetration and efficacy(28, 29). It is important to note that poor tumor penetration is not isolated to mice and in fact may be more acute in humans(30–32). In a retrospective study of head and neck cancers, high resolution fluorescence imaging confirmed heterogenous antibody delivery(33) while increasing antibody doses (from a loading dose) improved tissue penetration(34).

Tumor tissue penetration, which impacts efficacy, cannot be considered in isolation. Equally important is the toxicity. For example, at the clinical dose of 3.6 mg/kg, 43.1% of patients treated with Kadcyla displayed ≥ grade 3 adverse effects(35). Alternative dosing methods with ADCs are being investigated to potentially increase tolerability, such as fractionated dosing. In a retrospective study on the clinical impacts of dose fractionation vs standard dosing, it was determined that ADCs targeting hematological tumors benefited from fractionated dosing. However, when reviewing efficacy of Kadcyla with single dose vs fractionated dosing, the clinical benefit decreased with fractionated dosing(36). While there are several potential reasons for this difference, delivery limitations in solid tumors can contribute to the decreased benefit. Reducing the administered dose and increasing the frequency may be more tolerable, but a smaller dose typically results in a lower plasma concentration, reduced tumor penetration, and a lower targeted fraction of tumor cells.

Simulations of dose fractionation using an agent-based model have predicted reduced efficacy with fractionated dosing (37), matching experimental outcomes(38). These results are not limited to Kadcyla. Padcev demonstrated significantly reduced efficacy when the dose was fractionated, even with the same total payload dose, and multiple other ADCs have Cmax-driven efficacy(26) (proportional to tissue penetration), highlighting the importance of plasma concentration(39). To demonstrate the impact of fractionated dosing on tumor penetration, we administered two doses of fluorescently tagged Kadcyla, spaced one week apart, in a high expressing HER2+ cell line followed by tumor resection at 24hrs after the 2nd dose. Figure 1b shows significant overlap between cells targeted in the initial dose and the following dose one week later. The second dose largely had similar penetration as the first. In contrast, a higher bolus dose increases tissue penetration(40, 41).

Increasing the antibody plasma concentration by single dose administration can result in improved tissue penetration (quantitatively measured by flow cytometry(29) and/or Euclidean distance mapping(42, 43)) and higher efficacy. While several examples of this exist in the literature(44–48), this general trend can be confounded by another important aspect of drug delivery: tumor saturation.

Tumor Saturation

Another critical aspect of translating preclinical models to the clinic is tumor saturation. This is dependent on a variety of conditions including dose (i.e. Cmax), expression (receptors/cell), internalization rate(22, 29, 40), and plasma clearance among other considerations(49). This is important due to a combination of two factors: a greater likelihood of using saturating doses in preclinical models and opposite outcomes from saturating versus subsaturating doses. First, the doses administered to mice do not always correspond to clinically tolerable doses. Sometimes, the doses are increased to account for faster clearance in mice or a less responsive tumor model, and other times, higher doses are given because they are better tolerated in mice. This can lead to saturation in preclinical models while clinically tolerated doses may be subsaturating. Since mouse cells are often less responsive to ADC payloads than human cells, this can be further exacerbated in syngeneic models, where large doses are necessary for response (e.g. TUBO, Fo5 models). These large doses can overshadow delivery issues in the clinic, where ADC doses (3.6 and 6.4 mg/kg) may leave cells untargeted(50) versus higher doses attainable with unconjugated antibodies (e.g. 15 mg/kg of Margenza(51)). The second factor is that the outcome of preclinical studies under a saturating dose can yield the opposite result of the outcome under a subsaturating dose in the clinic. As described in examples below, increasing the DAR is more effective if a saturating dose is given, while decreasing the DAR can be more effective when a subsaturating dose is given. Typically, doses are limited by the payload toxicity, so comparisons are done at a constant payload dose. When the tumor is super-saturated, cancer cells receive the maximum amount of antibody, so more payloads per antibody will deliver more payload per tumor cell, resulting in greater efficacy. The opposite is true for a subsaturating dose. Here, the ADC does not reach all the cancer cells, and increasing the DAR (at a constant payload dose) will lower the amount of antibody delivered, reducing the number of cells that are targeted and killed. Instead, decreasing the DAR and/or increasing the total antibody dose under these conditions can improve tissue penetration and overall efficacy(40).

To saturate a tumor with high target expression, a large Cmax must be achieved, particularly when combined with the efficient internalization needed for payload delivery. Since Cmax is related to the MTD, an ADC must be well tolerated to achieve saturating doses. Trodelvy operates in this regime as an ADC for solid tumors with a high DAR and moderate potency payload. Although this design goes against many traditional strategies, the moderate potency payload provided a greater range in tolerability for optimizing the DAR. In a 2015 study by Goldenberg et al., the DAR was varied from 1.64 to 6.89 drugs per antibody. When ADCs with varying DARs were delivered at equivalent, saturating doses of ~20 and 40 mg/kg, the higher DAR of 6.89 payloads per antibody provided a significant improvement in survival when compared to lower DAR variants(3). This study demonstrated that a higher DAR can be beneficial for a well-tolerated, moderate potency payload when tumor saturation can be achieved.

Similarly, mirvetuximab soravtansine is capable of saturating tumors at doses of approximately 6 mg/kg(52). In a mouse study utilizing ADCs with varying DAR, Yoder et al. demonstrated that a higher DAR (3–4 payloads per antibody) was more effective than the same payload dose delivered via a site-specific DAR2 variant. Comparisons showed 6 mg/kg of the higher DAR was more effective than 12 mg/kg of the DAR2, and 12 mg/kg of the higher DAR was more effective than 24 mg/kg of the DAR2(53). While the linker conjugation chemistry is different, the results are consistent with the concept that a higher DAR is more effective when a saturating dose of antibody is delivered. In contrast, when a subsaturating antibody dose is delivered (< 3 mg/kg), efficacy can be improved by adding a carrier dose(22).

Based on the above comparisons, the payload MTD should be linked to a (near) saturating dose of the antibody for maximum tissue penetration and efficacy. The payload MTD will depend on the specific payload, while the saturating antibody dose will depend on tumor and target characteristics. A potential caveat to this generalization stems from the payload itself. Depending on the physicochemical properties of the payload, the payload may be able to escape a targeted cell and diffuse to an adjacent cell to enact cell death in a process known as the ‘bystander effect’.

Role of bystander effects

The three recently approved ADCs for solid tumors all use a payload capable of bystander killing. A bystander payload can diffuse out of a targeted cell following release and into an adjacent cell. The ability to reduce one of the common resistance mechanisms, antigen negative cancer cells, with bystander payloads has drawn a considerable interest in this area. In theory, bystander payloads are also capable of improving tissue penetration beyond what is achieved by the antibody itself(54, 55). This may explain the increased efficacy displayed by Enhertu when compared to Kadcyla in NCI-N87 mouse models despite similar cellular potencies(13, 24). Likewise, only Enhertu has been approved for use in gastric cancer with more heterogeneous HER2 expression(56, 57). However, increased tissue penetration from higher antibody doses still increases efficacy even when using ADCs with bystander payloads(44, 46, 58, 59). While bystander payloads can improve distribution, the efficiency of direct delivery by an antibody is greater than bystander killing(54), which explains the greater efficacy from higher antibody doses even with bystander payloads.

Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

ADCs are complex biologics with three main components that can be modified in numerous ways. While these modifications can improve the efficacy of ADCs, it has been difficult to identify key features of ADC design that lead to clinical success. Over the last couple decades, target selection, linker stability, and toxicity have been at the forefront of the design process. A failure in any of these categories would be cause for concern and likely shut down an ADC in the pipeline. Even so, many ADCs that appear promising in preclinical studies ultimately fail in clinical trials due to toxicity and/or a poor therapeutic window. Here, we argue that tissue penetration and tumor saturation are essential measurements in the development of ADCs. The results highlighted in this work show the importance of tissue penetration and its complex relationship with dosing and ADC design. It is important to note that strategies to improve tissue penetration will only work under subsaturating conditions. While this may be common in the clinic, tumor saturation can more readily be achieved in animal models, potentially confounding efforts to scale to the clinic. Therefore, preclinical studies need to collect data regarding the most important parameters for efficacy, including tumor penetration and saturation. In an ideal design scenario at least two pieces of information would be known: the tolerable payload dose in humans and the antibody dose required to saturate the target in the tumor. With this information, an upper limit can be set on the total payload delivered which can be matched by modifying the DAR. The technique would deliver the most payload tolerable while targeting all tumor cells with the goal of maximizing efficacy at clinically tolerable doses.

Box 1. ADC Origins and Renaissance.

Despite recent clinical success, antibody drug conjugates have a longer history than monoclonal antibodies themselves. Embodying Ehrlich’s Zauberkugeln or ‘Magic Bullets,’ proposed at the turn of the previous century, researchers first treated mouse leukemia with amethopterin-gamma-globulins in 1958(1). Even more avant-garde, Ghose and colleagues treated a melanoma patient by intra-tumoral and intravenous injection of chlorambucil-anti-melanoma-globulin in 1971 where ‘all metastatic nodules regressed’(5). With the advent of monoclonal antibodies by Kohler and Milstein in 1975, the modern concept of an ADC, with a specific target and controlled payload linkage, was born. A polyclonal vindesine-anti-CEA conjugate was the first target-specific ADC tested in several patients in 1983(11).

It’s impossible to capture the accelerating ADC research over the interim between this trial and the current 10 FDA-approved ADCs in brief. Several notable highlights from this and related fields include the humanization of antibodies to avoid immune reactions(14), understanding antibody delivery issues including the ‘binding site barrier’(10), elevated tumor interstitial pressure(8, 9), protein engineering advances(16), and their impact on delivery(18). Within the ADC field, some of the early payloads lacked the potency required for ADCs, which limit cellular delivery to the internalization rate and number of receptors per cell, generating a push for more potent payloads. This led to ultra-high payload potency using some of the most toxic known (and synthetic) compounds. The higher potency also generated a push towards ‘cleaner’ targets with less healthy tissue expression. However, these targets tend to have lower tumor expression, and ultimately the higher potency payloads ran into non-target mediated toxicity limitations(12). As discussed here, the current successful agents, particularly for solid tumors, have utilized high-expression targets (105 to 106 receptors/cell) with moderately high payload potency(3, 22) delivered with large antibody doses (3.6 to 20 mg/kg over a 3-week period).

In terms of generating approved drugs, the trajectory has been rocky. After the first FDA approval of Mylotarg in 2000, the drug was removed from the market 10 years later, going from 1 to 0 approved drugs in a decade. During the 2010’s, ADCs re-entered the market, including the first solid tumor ADC, Kadcyla in 2013. However, a string of high-profile failures dampened enthusiasm among many companies. It wasn’t until the approval of 6 ADCs in a span of 2 years, including 3 for solid tumors, that enthusiasm has again returned. It’s important we apply the lessons of the past to ensure a bright future for the field.

Box 2. ADC Delivery Challenges.

Large biologics like ADCs suffer from two major delivery challenges: little ADC actually reaches the tumor and what does make it is poorly distributed. These challenges stem from multiple factors. After infusion, the ADC must travel from the injection site through the vasculature to the tumor. The large size of ADCs limits extravasation, so vascular permeability and vessel density/surface area are the rate-limiting factors in tumor uptake (versus blood flow for small molecules) (2). While tumor vasculature is leaky, it is also tortuous and poorly distributed, resulting in lower tumor delivery compared to healthy tissue. This fact has been exploited in preblocking approaches (Zevalin (6), Bexxar, (7)). It’s only through binding and retention that the tumor concentrations slowly rise above healthy tissue over time, but most of the ADC is metabolized throughout the body. Tumor delivery of ADCs is further exacerbated by the elevated interstitial pressure that tumors experience due to poor lymphatic drainage. The high interstitial pressure limits transport by convection and leads to diffusion-dominated tumor tissue penetration(8, 9). Under these conditions, the high binding affinity of ADCs result in a common phenomenon first described as the ‘binding site barrier’(10).

Clinical antibodies and ADCs are high affinity binders leading to a more rapid rate of binding than diffusion. Upon entering the tumor tissue, the ADC binds the nearest available target receptor. For highly expressed targets, free receptors typically outnumber ADCs, and the combination of limited uptake, slow diffusion, and high affinity leads to perivascular uptake of ADCs. For unconjugated antibodies, patients often tolerate high doses enabling receptor saturation, but these doses are too toxic for ADCs due to their payload(12). The continual internalization of targeted cells and dynamic tumor microenvironment prevent the ADC from ever reaching cells deeper in the tissue(13), so few cells receive treatment.

While tissue penetration has not received as much attention as other aspects of ADC design, it is arguably equally (or more) important than many well-studied rates such as plasma clearance. Successful agents like Padcev and Trodelvy have fast plasma clearance rates (3.4 and 0.7 days respectively vs. 16 days for an antibody, trastuzumab), but their dosing enables efficient tissue penetration. Although delivery issues are not the only challenge in ADC design, their common occurrence makes it imperative to measure distribution for every ADC to ensure delivery isn’t serving as a confounding factor leading to misinterpretation of results.

Highlights.

Antibody drug conjugates are complex prodrugs that combine the targeting of antibodies with the potency of small molecule but also the delivery challenges of biologics with the toxicity of chemotherapeutics.

Current FDA-approved ADCs for solid tumors target high expression antigens with large doses of IgG1-based therapeutics.

The paradigm for clinically successful ADCs points to tissue penetration as playing a key role in efficacy.

The lack of tissue penetration issues in vitro, high tolerability in mouse models, and potential to saturate tumors preclinically makes scaling to the clinic challenging, and delivery considerations should play a central role in decision-making for solid tumor ADC development.

Glossary

- Antibody dependent cell mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC)

A cell mediated immune response, where a target cell coated in antibodies is lysed by an immune effector cell

- Antibody dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP)

A phagocyte recognizes membrane-bound antibodies and neutralizes the cell through engulfment

- Antibody drug conjugate (ADC)

An antibody that is conjugated to a potent cytotoxic drug. The antibody drives specific uptake of the drug to cancer cells

- Area under the curve (AUC)

Integral of the plasma concentration vs. time curve. This metric serves as a correlate to total systemic exposure of a drug

- Besponsa (Inotuzumab ozogamicin)

ADC targeting CD22 FDA approved in 2017

- Bystander effect/killing

Depending on a payload’s physicochemical properties, it may be able to diffuse through a targeted cell’s membrane and into an adjacent cell to enact cell death

- CL2A

a pH sensitive linker that is used to attach payload to an antibody such as Trodelvy

- Cmax

The maximum concentration of a therapeutic in the blood, typically occurring shortly after infusion for intravenously delivered ADCs

- Dose limiting toxicity (DLT)

Adverse event (AE), typically grade 3 or 4, related to drug administration that prevent an increase in dose

- Drug to antibody ratio (DAR)

The number of payload molecules attached to each antibody

- Enhertu (Trastuzumab deruxtecan)

ADC targeting HER2 FDA approved for breast and gastric cancer in 2019

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

The regulatory body of the US that oversees safety and approval of drugs for use

- Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)

A highly expressed tumor antigen and a common target for targeted cancer therapies

- Immunogenic cell death (ICD)

Any form of cell death where an immune response is elicited

- Kadcyla (Trastuzumab emtansine)

The first FDA-approved ADC for solid tumor indications

- Maximum tolerated dose (MTD)

The highest dose at which unacceptable side effects are not experienced

- Mertansine (DM1)

A cytotoxic drug that acts by inhibiting the formation of microtubules by binding to tubulin

- Monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE)

A cytotoxic drug that acts by blocking the polymerization of tubulin

- OCT compound

Optimal Cutting Temperature solution for freezing tissue

- Padcev (Enfortumab vedotin)

ADC targeting Nectin-4 FDA approved for bladder cancer in 2019

- Payload

also known as a warhead, small molecule chemotherapeutic

- Linker

the connection between the antibody and payload that may be non-cleavable, cleavable, self-immolative; cleaved by proteases, hydrolysis, or reduction mechanisms

- Margenza (Margetuximab)

Antibody targeting HER2 FDA approved in 2020

- Pyrrolobenzodiazepine (PBD)

A cytotoxic drug that acts by binding and crosslinking the minor groove of DNA

- Q3W

Clinical shorthand for dosing every three weeks, a common dosing scheme for ADCs (e.g. used for Kadcyla)

- SMCC

a non-cleavable linker for antibody drug conjugates (used for T-DM1), Succinimidyl 4-(N-Maleimidomethyl)Cyclohexane-1-Carboxylate

- Trodelvy (Sacituzumab govitecan)

ADC targeting Trop-2 FDA approved for breast and urothelial cancer in 2020, utilizes a hydrolysable linker with lower stability than other approved ADCs

- TUBO

a cloned line established from a BALB-neuT mouse mammary carcinoma

- Fo5

A HuHER2 transgenic mouse model under the murine mammary tumor virus (MMTV) promoter

- VC

valine-citrulline, a common cleavable linker for antibody drug conjugation

- Zynlonta (loncastuximab tesirine)

ADC targeting CD19 FDA approved in 2021

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mathe G, Tran Ba LO, Bernard J, [Effect on mouse leukemia 1210 of a combination by diazoreaction of amethopterin and gamma-globulins from hamsters inoculated with such leukemia by heterografts]. C R Hebd Seances Acad Sci 246, 1626–1628 (1958). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmidt MM, Wittrup KD, A modeling analysis of the effects of molecular size and binding affinity on tumor targeting. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 8, 2861–2871 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldenberg DM, Cardillo TM, Govindan SV, Rossi EA, Sharkey RM, Trop-2 is a novel target for solid cancer therapy with sacituzumab govitecan (IMMU-132), an antibody-drug conjugate (ADC). Oncotarget 6, 22496–22512 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iwata TN et al. , A HER2-Targeting Antibody-Drug Conjugate, Trastuzumab Deruxtecan (DS-8201a), Enhances Antitumor Immunity in a Mouse Model. Mol Cancer Ther 17, 1494–1503 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghose T et al. , Immunochemotherapy of cancer with chlorambucil-carrying antibody. Br Med J 3, 495–499 (1972). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krasner C, Joyce RM, Zevalin: 90yttrium labeled anti-CD20 (ibritumomab tiuxetan), a new treatment for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 2, 341–349 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boswell CA et al. , Differential Effects of Predosing on Tumor and Tissue Uptake of an In-111-Labeled Anti-TENB2 Antibody-Drug Conjugate. Journal of Nuclear Medicine 53, 1454–1461 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jain RK, Transport of molecules in the tumor interstitium: a review. Cancer Res 47, 3039–3051 (1987). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jain RK, Transport of molecules across tumor vasculature. Cancer Metastasis Rev 6, 559–593 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weinstein JN et al. , The pharmacology of monoclonal antibodies. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 507, 199–210 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford CH et al. , Localisation and toxicity study of a vindesine-anti-CEA conjugate in patients with advanced cancer. Br J Cancer 47, 35–42 (1983). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donaghy H, Effects of antibody, drug and linker on the preclinical and clinical toxicities of antibody-drug conjugates. Mabs 8, 659–671 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cilliers C, Menezes B, Nessler I, Linderman J, Thurber GM, Improved Tumor Penetration and Single-Cell Targeting of Antibody-Drug Conjugates Increases Anticancer Efficacy and Host Survival. Cancer Research 78, 758–768 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riechmann L, Clark M, Waldmann H, Winter G, Reshaping human antibodies for therapy. Nature 332, 323–327 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cruz E, Kayser V, Monoclonal antibody therapy of solid tumors: clinical limitations and novel strategies to enhance treatment efficacy. Biologics 13, 33–51 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gai SA, Wittrup KD, Yeast surface display for protein engineering and characterization. Curr Opin Struct Biol 17, 467–473 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nessler I, Khera E, Thurber GM, Quantitative pharmacology in antibody-drug conjugate development: armed antibodies or targeted small molecules? Oncoscience 5, 161–163 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiner LM, Adams GP, New approaches to antibody therapy. Oncogene 19, 6144–6151 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rios-Doria J et al. , Antibody-Drug Conjugates Bearing Pyrrolobenzodiazepine or Tubulysin Payloads Are Immunomodulatory and Synergize with Multiple Immunotherapies. Cancer Res 77, 2686–2698 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou J et al. , Immunogenic cell death in cancer therapy: Present and emerging inducers. J Cell Mol Med 23, 4854–4865 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffmann RM et al. , Antibody structure and engineering considerations for the design and function of Antibody Drug Conjugates (ADCs). Oncoimmunology 7, e1395127 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ponte JF et al. , Antibody Co-Administration Can Improve Systemic and Local Distribution of Antibody-Drug Conjugates to Increase In Vivo Efficacy. Mol Cancer Ther 20, 203–212 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.U.S.FDA, Kadcyla Biologic License Application (125427Orig1s000). Pharmacol Rev (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ogitani Y et al. , DS-8201a, A Novel HER2-Targeting ADC with a Novel DNA Topoisomerase I Inhibitor, Demonstrates a Promising Antitumor Efficacy with Differentiation from T-DM1. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 22, 5097–5108 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun N et al. , Clinical application of the AUC-guided dosage adjustment of docetaxel-based chemotherapy for patients with solid tumours: a single centre, prospective and randomised control study. J Transl Med 18, 226 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang D et al. , Exposure-Efficacy Analysis of Antibody-Drug Conjugates Delivering an Excessive Level of Payload to Tissues. Drug Metab Dispos 47, 1146–1155 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bartelink IH et al. , Tumor drug penetration measurements could be the neglected piece of the personalized cancer treatment puzzle. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics 10.1002/cpt.1211 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bordeau BM, Yang Y, Balthasar JP, Transient competitive inhibition bypasses the binding site barrier to improve tumor penetration of trastuzumab and enhance T-DM1 efficacy. Cancer Res 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-3822 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nessler I et al. , Increased Tumor Penetration of Single-Domain Antibody-Drug Conjugates Improves In Vivo Efficacy in Prostate Cancer Models. Cancer Res 80, 1268–1278 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oldham RK et al. , Monoclonal antibody therapy of malignant melanoma: in vivo localization in cutaneous metastasis after intravenous administration. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2, 1235–1244 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schroff RW et al. , Monoclonal antibody therapy in malignant melanoma: factors effecting in vivo localization. J Biol Response Mod 6, 457–472 (1987). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eary JF et al. , Successful imaging of malignant melanoma with technetium-99m-labeled monoclonal antibodies. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine 30, 25–32 (1989). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu G et al. , Predicting Therapeutic Antibody Delivery into Human Head and Neck Cancers. Clin Cancer Res 26, 2582–2594 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu G et al. , Co-administered antibody improves penetration of antibody-dye conjugate into human cancers with implications for antibody-drug conjugates. Nat Commun 11, 5667 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.U.S.FDA, Kadcyla Package Insert. (2013).

- 36.Sapra P, Betts A, Boni J, Preclinical and clinical pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic considerations for antibody-drug conjugates. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 6, 541–555 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Menezes B, Cilliers C, Wessler T, Thurber GM, Linderman JJ, An Agent-Based Systems Pharmacology Model of the Antibody-Drug Conjugate Kadcyla to Predict Efficacy of Different Dosing Regimens. The AAPS journal 22, 29 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jumbe NL et al. , Modeling the efficacy of trastuzumab-DM1, an antibody drug conjugate, in mice. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn 37, 221–242 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Challita-Eid PM et al. , Enfortumab Vedotin Antibody-Drug Conjugate Targeting Nectin-4 Is a Highly Potent Therapeutic Agent in Multiple Preclinical Cancer Models. Cancer Res 76, 3003–3013 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cilliers C, Guo H, Liao JS, Christodolu N, Thurber GM, Multiscale Modeling of Antibody-Drug Conjugates: Connecting Tissue and Cellular Distribution to Whole Animal Pharmacokinetics and Potential Implications for Efficacy. Aaps J. 18, 1117–1130 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cilliers C, Menezes B, Nessler I, Linderman J, Thurber GM, Improved Tumor Penetration and Single-Cell Targeting of Antibody-Drug Conjugates Increases Anticancer Efficacy and Host Survival. Cancer Res 78, 758–768 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rhoden JJ, Wittrup KD, Dose dependence of intratumoral perivascular distribution of monoclonal antibodies. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 101, 860–867 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rhoden JJ, Dyas GL, Wroblewski VJ, A Modeling and Experimental Investigation of the Effects of Antigen Density, Binding Affinity, and Antigen Expression Ratio on Bispecific Antibody Binding to Cell Surface Targets. J Biol Chem 291, 11337–11347 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Junutula JR et al. , Site-specific conjugation of a cytotoxic drug to an antibody improves the therapeutic index. Nat Biotechnol 26, 925–932 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jackson D et al. , In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation of Cysteine and Site Specific Conjugated Herceptin Antibody-Drug Conjugates. Plos One 9 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hamblett KJ et al. , Effects of drug loading on the antitumor activity of a monoclonal antibody drug conjugate. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 10, 7063–7070 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pillow TH et al. , Site-specific trastuzumab maytansinoid antibody-drug conjugates with improved therapeutic activity through linker and antibody engineering. J Med Chem 57, 7890–7899 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Junutula JR et al. , Engineered thio-trastuzumab-DM1 conjugate with an improved therapeutic index to target human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 16, 4769–4778 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thurber GM, Weissleder R, Quantitating antibody uptake in vivo: conditional dependence on antigen expression levels. Molecular imaging and biology : MIB : the official publication of the Academy of Molecular Imaging 13, 623–632 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dijkers EC et al. , Biodistribution of Zr-89-trastuzumab and PET Imaging of HER2-Positive Lesions in Patients With Metastatic Breast Cancer. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 87, 586–592 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bang YJ et al. , First-in-human phase 1 study of margetuximab (MGAH22), an Fc-modified chimeric monoclonal antibody, in patients with HER2-positive advanced solid tumors. Ann Oncol 28, 855–861 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ponte JF et al. , Antibody Co-Administration Can Improve Systemic and Local Distribution of Antibody Drug Conjugates to Increase In Vivo Efficacy. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics (2020, in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoder NC et al. , A Case Study Comparing Heterogeneous Lysine- and Site-Specific Cysteine-Conjugated Maytansinoid Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs) Illustrates the Benefits of Lysine Conjugation. Mol Pharm 16, 3926–3937 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Khera E, Cilliers C, Bhatnagar S, Thurber GM, Computational transport analysis of antibody-drug conjugate bystander effects and payload tumoral distribution: implications for therapy. Molecular Systems Design & Engineering 3, 73–88 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Burton JK, Bottino D, Secomb TW, A Systems Pharmacology Model for Drug Delivery to Solid Tumors by Antibody-Drug Conjugates: Implications for Bystander Effects. The AAPS journal 22, 12 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thuss-Patience PC et al. , Trastuzumab emtansine versus taxane use for previously treated HER2-positive locally advanced or metastatic gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (GATSBY): an international randomised, open-label, adaptive, phase 2/3 study. The lancet oncology 18, 640–653 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shitara K et al. , Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Previously Treated HER2-Positive Gastric Cancer. N Engl J Med 382, 2419–2430 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sukumaran S et al. , Mechanism-Based Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Model for THIOMAB Drug Conjugates. Pharm Res 32, 1884–1893 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pabst M et al. , Modulation of drug-linker design to enhance in vivo potency of homogeneous antibody-drug conjugates. Journal of controlled release : official journal of the Controlled Release Society 253, 160–164 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]