Abstract

Rap1, a small GTPase of the Ras family, is ubiquitously expressed and particularly abundant in platelets. Previously we have shown that Rap1 is rapidly activated after stimulation of human platelets with α-thrombin. For this activation, a phospholipase C-mediated increase in intracellular calcium is necessary and sufficient. Here we show that thrombin induces a second phase of Rap1 activation, which is mediated by protein kinase C (PKC). Indeed, the PKC activator phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate induced Rap1 activation, whereas the PKC-inhibitor bisindolylmaleimide inhibited the second, but not the first, phase of Rap1 activation. Activation of the integrin αIIbβ3, a downstream target of PKC, with monoclonal antibody LIBS-6 also induced Rap1 activation. However, studies with αIIbβ3-deficient platelets from patients with Glanzmann's thrombasthenia type 1 show that αIIbβ3 is not essential for Rap1 activation. Interestingly, induction of platelet aggregation by thrombin resulted in the inhibition of Rap1 activation. This downregulation correlated with the translocation of Rap1 to the Triton X-100-insoluble, cytoskeletal fraction. We conclude that in platelets, α-thrombin induces Rap1 activation first by a calcium-mediated pathway independently of PKC and then by a second activation phase mediated by PKC and, in part, integrin αIIbβ3. Inactivation of Rap1 is mediated by an aggregation-dependent process that correlates with the translocation of Rap1 to the cytoskeletal fraction.

Rap1 is a small GTPase of the Ras family that is ubiquitously expressed but particularly abundant in platelets, neutrophils, and the brain (19). The protein was first identified as a product of a cDNA inducing a flat revertant phenotype in K-Ras-transformed (Krev-1) cells (15). The core effector domain of Rap1 is virtually identical with that of Ras. This has led to the hypothesis that Rap1 can interact with downstream targets of Ras, resulting in inhibition or activation of Ras effector signalling. There are also data challenging this hypothesis and suggesting that Rap1 functions independently of Ras (31, 32). Cellular processes that seem to involve Rap1 activity include cell proliferation and differentiation, platelet, neutrophil, and B-cell activation, induction of T-cell anergy, and the regulation of the respiratory burst in neutrophils (for a recent review, see reference 4). Recently it was shown that Spa-1, a GTPase-activating protein (GAP) for Rap1, inhibited cell adhesion, whereas C3G, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) for Rap1, induces adhesion, suggesting a role for Rap1 in this process (27).

Recent detailed analysis of Rap1 activation, i.e., an increase in the GTP-bound form of the GTPase, revealed that Rap1 is activated very rapidly by different types of second messengers: depending on cell type, Rap1 is activated by Ca2+ (9, 24, 32), diacylglycerol (DAG) (17), and cyclic AMP (2). In addition, Rap1 is activated by cell adhesion (23). In some cell types still unidentified, Rap1-activating pathways exist (18). The activation of Rap1 is most likely mediated by GEFs. Several of these have recently been identified, including CalDAG-GEFI, a GEF that is sensitive to both Ca2+ and DAG (13), and Epac, a GEF that is directly activated by cyclic cAMP (7, 14). Another Rap1-specific GEF is C3G (11, 28). This protein forms complexes with Crk family members, Src homology 2 (SH)2 and SH3 domain-containing adapters that associate with tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins like Cbl and Cas (16). However, it is not yet clear if these interactions have an effect on C3G activity. Apart from these positive regulators of Rap1 activity, several negative regulators for Rap1, i.e., GAPs, have been described (4).

The very abundant presence of Rap1 in platelets (26) has made this cell system an interesting model with which to study Rap1 activation in more detail. In these anucleate cells, Rap1 is activated within seconds following stimulation with a variety of agonists, including α-thrombin. This activation is mediated by Ca2+, which is both necessary and sufficient (9, 31). We now show that after the initial, calcium-mediated phase of Rap1 activation, thrombin induces a second phase of Rap1 activation which is mediated by protein kinase C (PKC). Furthermore, we show that activation of αIIbβ3 may contribute to the sustained phase of Rap1 activation, although αIIbβ3 is not essential. Finally, we show that aggregation induces the inactivation of Rap1. This inactivation correlates with the translocation of Rap1 to the Triton X-100-insoluble, cytoskeletal fraction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Platelets were incubated with the following agents at the concentrations indicated. α-Thrombin (0.1 or 0.5 U/ml) and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; 10 nM) were from Sigma; platelet-activating factor (PAF; 200 nM) and the PKC inhibitor Gö 6976 were from Calbiochem. The PKC inhibitor bisindolylmaleimide was from Boehringer Mannheim, and the cyclo-oxygenase inhibitor indomethacin was from Sigma. Sepharose 2B was from Pharmacia Biotech; glutathione-agarose beads were from Sigma; polyvinylidene difluoride membranes and the enhanced chemiluminescence kit were from DuPont NEN. The monoclonal anti-Rap1 antibody was from Transduction Laboratories. The integrin-activating Fab fragments of monoclonal antibody LIBS-6 were a kind gift by M. H. Ginsberg, Scripps Clinic and Research Foundation, La Jolla, Calif. The aggregation-inhibitory peptidomimetic Ro 44-9883 was a kind gift from M. Steiner, Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Basel, Switzerland, and F. Lanza, INSERM U311, Strasbourg, France.

Platelet isolation and stimulation.

Platelets were isolated as described earlier (9). Shortly, freshly drawn venous blood from healthy volunteers (with informed consent) who claimed not to have taken any medication for at least 10 days was collected into a 0.1 volume of 130 mM trisodium citrate. Platelet-rich plasma was prepared by centrifugation of the blood at 200 × g at room temperature. After addition of 0.1 volume of ACD (1.5% citric acid, 2.5% trisodium citrate, 2% d-glucose), platelets were centrifuged at 700 × g at room temperature for 15 min to prepare washed platelets. They were resuspended in HEPES-Tyrode buffer at a concentration of 5 × 108 platelets/ml for experiments described in Fig. 1 to 4 (0.2% bovine serum albumin and 1 mM Ca2+ were added to the platelet in these cases). For the other experiments, platelets were resuspended at a concentration of 2 × 108 platelets/ml. For gel filtration, platelet-rich plasma–ACD was loaded on a Sepharose 2B column equilibrated with Tyrode buffer and passed through by gravity. Platelet count was adjusted to 2 × 108 platelets/ml. Platelets were left at room temperature for 30 min. Prior to stimulation, platelets were warmed to 37°C. During the experiments, samples were incubated in a lumiaggregometer (Chrono-Log Corporation) at 37°C. In aggregation experiments regarding the translocation and downregulation of Rap1, platelets were incubated under stirring at 900 rpm. In all other experiments, incubation was without stirring to prevent aggregation during stimulation in the presence or absence of aggregation inhibitors, like the GRGDS peptide (100 μM), the γ-peptide400-411 (100 μM), or the peptidomimetic Ro 44-9883 (1 μM) (1, 5), added 1 min prior to stimulation. Where indicated, indomethacin (30 μM, 30 min preincubation) was added to the platelets to prevent thromboxane A2 (TxA2) formation. Aliquots of 200 μl of platelet suspension were used for the activation assay; aliquots of 900 μl were used for cytoskeleton isolation.

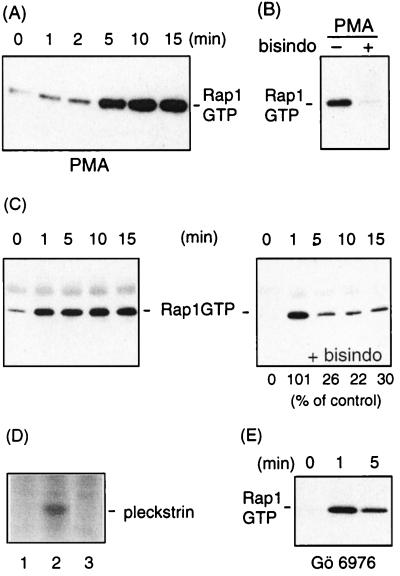

FIG. 1.

PKC mediates thrombin-induced Rap1 activation. (A) Platelets preincubated with indomethacin to inhibit release of thromboxane (30 μM, 30 min) were stimulated with the PKC-activating phorbol ester PMA (10 nM) under nonaggregating conditions. (B) Platelets were preincubated without (−) or with (+) the PKC inhibitor bisindolylmaleimide (bisindo; 5 μM) for 1 min and stimulated with PMA as in panel A for 10 min. (C) Platelets were incubated either with buffer (left) or with bisindolylmaleimide (5 μM, 1 min) (right) prior to stimulation with 0.1 U of α-thrombin per ml under nonaggregating conditions. Platelets were lysed at the indicated times, and Rap1GTP was recovered and analyzed. Indicated beneath the blots is the percentage of Rap1GTP remaining in the inhibitor-treated samples compared to the control sample, as determined by densitometric scanning of the blots. The results shown are representative of three experiments with similar results. (D) 32P-orthophosphate-labeled platelets (29) were either not incubated (lane 1) or incubated with bisindolylmaleimide (5 μM, 1 min) (lane 2) and vehicle (lane 3) prior to stimulation with 0.1 U of α-thrombin per ml for 1 min. Platelets were lysed; the lysate was separated by gel electrophoresis followed by autoradiography. Indicated is the position of pleckstrin, the major PKC substrate in platelets. (E) Platelets were incubated with the PKC inhibitor Gö 6976 (5 μM, 35 min) prior to stimulation with 0.1 U of α-thrombin per ml under nonaggregating conditions, and Rap1GTP was detected.

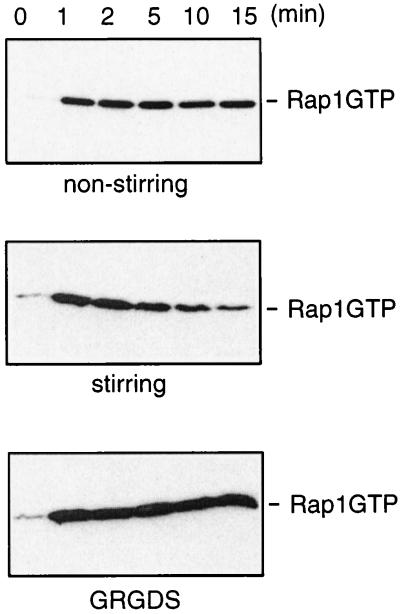

FIG. 4.

Aggregation induces inactivation of Rap1. Platelets were stimulated with α-thrombin (0.5 U/ml) for the time indicated, and Rap1GTP was recovered and analyzed. Incubation with thrombin occurred under the following conditions: nonstirring, stirring, and stirring in the presence of the GRGDS peptide (100 μM), which was added 1 min prior to stimulation.

Rap1 activity assay.

The assay was performed essentially as described earlier (9). At the time point of lysis, 1 volume of 2× lysis buffer was added to the platelet suspension (final concentrations, 10% glycerol, 1% Nonidet P40, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 200 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride (PMSF), 1 μM leupeptin, and 0.1 μM aprotinin). Lysis was on ice for at least 10 min; samples with aggregated platelets were passed through an insulin syringe three times. The lysate was cleared by centrifugation at maximal speed in an Eppendorf centrifuge for 10 min at 4°C. Glutathione-agarose beads coupled to GST-RalGDS-RBD (1 h of tumbling at 4°C) were added to the cleared lysate, and precipitation of GTP-bound Rap1 was performed for 45 min at 4°C, with tumbling. The beads were washed three to four times in lysis buffer and then collected in Laemmli sample buffer. Where indicated, lysate of the cleared platelet samples was taken into sample buffer as a control. Some of the Rap1 activity measurements were repeated in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (final concentrations, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 1% Nonidet P-40, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% deoxycholic acid, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 1 mM PMSF, 1 μM leupeptin, and 0.1 μM aprotinin) to compare them to the activity measurements in separated cytoskeleton and soluble fractions (see below). Samples were applied to SDS–15% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Rap1 was detected using a polyclonal antibody directed against Rap1 and a secondary anti-rabbit antibody carrying a horseradish peroxidase group, followed by enhanced chemiluminescence. Quantification of blots was performed with NIH Image software.

Platelet cytoskeleton isolation.

Platelets were lysed in 0.1 volume of 10× CSK buffer (final concentrations, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 10 mM EGTA 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM PMSF, 1 μM leupeptin, and 0.1 μM aprotinin) for 15 min on ice. Samples with aggregated platelets were passed through an insulin syringe once. Cytoskeletal fractions were collected by centrifugation in an Eppendorf centrifuge at maximal speed for 10 min at 4°C. The cytoskeleton pellet was washed once in 1× CSK buffer.

For experiments regarding Rap1 activity in cytoskeletal and soluble fractions, the cytoskeleton was solubilized in RIPA adapter buffer (final concentrations, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 30 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% deoxycholic acid, and 0.1% SDS in HEPES-Tyrode-CSK buffer) for at least 15 min, passed through an insulin syringe three times, and then centrifuged again to remove unsolubilized debris. To the soluble fractions, 0.25 volumes of 5× RIPA adapter buffer was added to measure Rap1 activity in both fractions, cytoskeletal and soluble, in the same buffer. After centrifugation, samples were treated as described for the Rap1 activity assay. To show the translocation of Rap1, 0.6% of the RIPA-solubilized, cleared cytoskeletal fractions were applied to an SDS-polyacrylamide gel.

Platelet aggregation.

Washed platelets at a concentration of 2 × 108 platelets/ml were incubated in a Chrono-log lumiaggregometer at 37°C. Inhibitor was added 35 min prior to stimulation in the case of Gö 6976 (5 μM) and 1 min in the case of bisindolylmaleimide (5 μM). Platelet aggregation was induced by addition of α-thrombin (0.1 U/ml) under continuous stirring at 900 rpm and was recorded. Measurement of platelet aggregation in a Chrono-Log aggregometer is based on the increase in light transmission through the platelet suspension.

Patient analysis.

Seven unrelated patients with Glanzmann's thrombasthenia type I were studied. The diagnosis of Glanzmann's thrombasthenia was based on a markedly prolonged Simplate bleeding time (> 30 min; normal < 8 min). All patients have been described previously (12, 25). Fluorescence-activated cell sorting data revealed less than 1% αIIbβ3-positive cells in all patients. One patient suffers from thrombocytopenia.

RESULTS

PKC is involved in a second phase of thrombin-induced Rap1 activation.

In a previous study we had observed that the phorbol ester PMA, an activator of PKC, induced a weak activation of Rap1 3 min after stimulation (9). To extend these studies, we addressed the question of whether PKC can mediate Rap1 activation. Freshly isolated human platelets were stimulated with PMA for various periods of time and lysed. Rap1 was precipitated with GST-tagged Rap-binding domain of RalGDS and identified by Western blotting. By this procedure, only the active, GTP-bound form of Rap1 is detected. Active Rap1 was strongly induced 5 min after PMA stimulation and remained active for at least 10 min (Fig. 1A). This activation was abolished by the PKC inhibitor bisindolylmaleimide, showing that PMA-induced Rap1 activation is mediated by PKC (Fig. 1B). The observation that Rap1 activity is only slowly induced after PMA stimulation may be explained by the relative slow kinetics by which PMA activates PKC in platelets (30). Since thrombin is a strong inducer of PKC, we next measured the effect of the two PKC inhibitors bisindolylmaleimide and Gö 6976 on thrombin-induced Rap1 activity. The amount of active Rap1 induced after 1 min was not affected at all by the inhibitors, but at later time points active Rap1 strongly diminished (Fig. 1C and E). To control for the effect of bisindolylmaleimide at the 1-min time point, we measured thrombin-induced pleckstrin phosphorylation, the major substrate of PKC in platelets. This phosphorylation was completely inhibited (Fig. 1D). As shown previously, staurosporin and calphostin C, two other inhibitors of PKC, also did not inhibited thrombin-induced Rap1 activation at the 1-min time point (9). From this result, we conclude that thrombin-induced Rap1 activation is sequentially regulated by a PKC-independent and a PKC-dependent pathway.

The PKC-dependent pathway includes activation of integrin αIIbβ3.

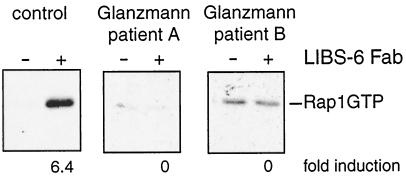

As shown previously (9) the first, PKC-independent pathway is mediated by a phospholipase C (PLC)-mediated increase in intracellular calcium. To investigate the second, PKC-dependent pathway in further detail, we addressed the question whether integrin αIIbβ3, a downstream target of PKC-mediated signalling (29) and the major mediator of platelet aggregation (22), is involved in the activation of Rap1. To activate αIIbβ3, we used monoclonal antibody LIBS-6. This antibody binds to the β3 subunit of αIIbβ3 and induces the active conformation of αIIbβ3 on resting platelets (10). As shown in Fig. 2, Fab fragments of LIBS-6 clearly induced an increase in active Rap1. To investigate whether this effect is indeed mediated by αIIbβ3, we used αIIbβ3-deficient platelets from patients with Glanzmann's thrombasthenia type I. No LIBS-6-induced activation of Rap1 was observed in these platelets. From these results we conclude that activation of integrin αIIbβ3 leads to activation of Rap1. This implies that αIIbβ3 may mediate the second phase of thrombin-induced activation of Rap1.

FIG. 2.

Activation of αIIbβ3 results in the activation of Rap1. Platelets isolated from a healthy volunteer (left) or platelets deficient in integrin αIIbβ3 expression, isolated from patients with Glanzmann's thrombasthenia (two right panels), were preincubated with 30 μM indomethacin for 30 min to inhibit TxA2 formation. After that time they were stimulated with Fab fragments of monoclonal antibody LIBS-6 at a concentration of 4 μM for 5 min under nonaggregating conditions. After lysis, active, GTP-bound Rap1 was precipitated. Indicated beneath the panel is the fold induction of Rap1 activity by LIBS-6 compared to unstimulated platelets. The same result was achieved in one additional experiment.

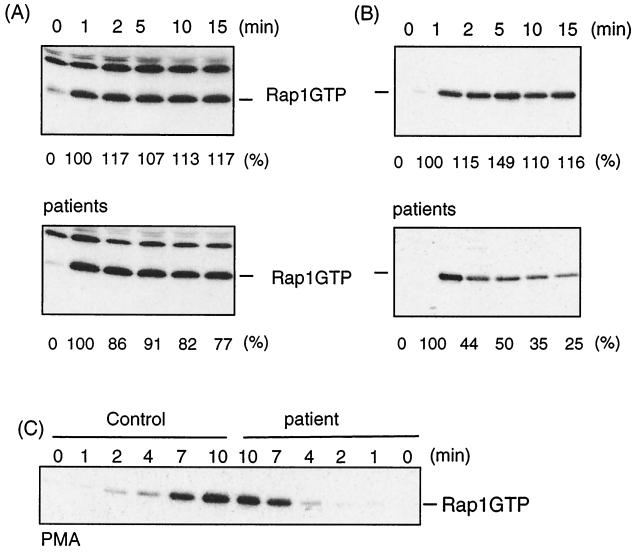

We next investigated whether αIIbβ3 is crucial for the second phase of Rap1 activation. αIIbβ3-deficient platelets from patients with Glanzmann's thrombasthenia type I were incubated with thrombin, and active Rap1 was determined. In platelets from five patients, the second phase of Rap1 activation was hardly, if at all, reduced (Fig. 3A). Also, PMA-induced Rap1 activation was hardly affected in αIIbβ3-deficient platelets of three patients (Fig. 3C). From these results we conclude that αIIbβ3 is not essential for the second phase of thrombin-induced Rap1. Interestingly, in the αIIbβ3-deficient platelets of two other patients we observed a strong reduction in sustained Rap1 activity (Fig. 3B). Apparently, in these two patients αIIbβ3 deficiency does affect sustained Rap1 activation. It should be noted that with respect to αIIbβ3-positive cells as determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorting all patients were the same, i.e., less than 1% αIIbβ3-positive platelets (12, 25). Indeed, in the presence of thrombin, these platelets fail to aggregate (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

αIIbβ3 is not essential for sustained Rap1 activation. Platelets from healthy volunteers (upper panels) or Glanzmann's thrombasthenia patients (lower panels) were isolated by gel filtration, preincubated with 30 μM indomethacin for 30 min to prevent release from TxA2, and stimulated with α-thrombin (0.1 U/ml) without stirring. At the indicated time, platelets were lysed and Rap1GTP was isolated and analyzed. Beneath the blots, the amount of active Rap1 is indicated as a percentage of the activity at 1 min. The Rap1 activity profile shown for the patient in panel B was found in one additional patient; in four other cases the reduction in active Rap1 was little to none. (C) Platelets were treated as described above but incubated with PMA (10 nM) instead of thrombin for the time indicated, and Rap1GTP was determined.

Aggregation of platelets results in the inactivation of Rap1.

The experiments thus far were performed under nonaggregating conditions; i.e., the platelets were not stirred during the incubation. If the platelets were stirred and aggregation occurred, we found that thrombin-induced Rap1 activation was rapidly downregulated (Figure 4). To investigate whether indeed aggregation was causing the downregulation of Rap1, we used αIIbβ3 antagonists that block the binding of αIIbβ3 to fibrinogen, the extracellular component that mediates platelet aggregation. Antagonists of αIIbβ3 include peptides like GRGDS and γ-peptide400-411 that are derived from fibrinogen (5) and the peptidomimetic Ro 44-9883 (1). GRGDS prevented the downregulation of Rap1 when platelets were stirred during incubation with thrombin (Fig. 4). Identical results were obtained with γ-peptide400-411 and with Ro 44-9883 (data not shown). We conclude that αIIbβ3-mediated aggregation results in the downregulation of Rap1 activity.

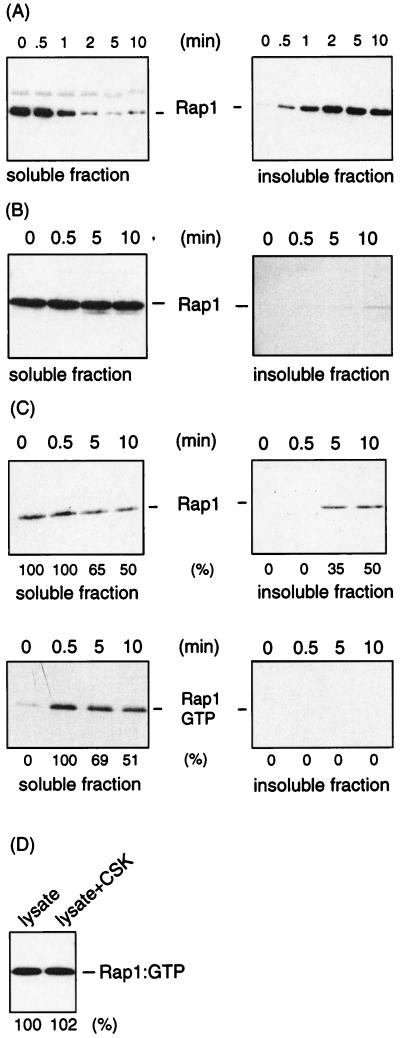

Downregulation of Rap1 correlates with translocation of Rap1.

As reported previously (8), in platelets stimulated with α-thrombin under stirring conditions, Rap1 translocates almost completely to the Triton X-100-insoluble, cytoskeletal fraction within 5 min (Fig. 5A). This translocation is dependent on aggregation, as it can be inhibited by the GRGDS peptide (Fig. 5B). The translocation correlates with the downregulation of Rap1 (Fig. 4). We therefore addressed the question of whether Rap1 in the translocated fraction is indeed in the inactive, GDP-bound form. We incubated platelets with thrombin under conditions in which only a partial translocation of Rap1 was observed (Fig. 5C). The Triton X-100-insoluble fraction was solubilized, and the amount of active Rap1 was measured. No active Rap1 could be detected in the Triton X-100-insoluble fraction (Fig. 5C). To exclude the possibility that the failure to detect Rap1 activity in the Triton X-100-insoluble fraction was due to a technical problem, active Rap1-containing platelet lysate was mixed with the Triton X-100-insoluble fraction and solubilized. No difference in the amount of active Rap1 recovered in the absence or presence of the Triton X-100-insoluble fraction was observed (Fig. 5D). From these results we conclude that exclusively inactive Rap1 is present in the Triton X-100-insoluble fraction.

FIG. 5.

Downregulation of Rap1 correlates with Rap1 translocation. (A) Platelets were stimulated with α-thrombin (0.5 U/ml) under conditions that allow aggregation of the platelets (stirring) for the indicated time at 37°C. Platelets lysates were separated in a Triton X-100-soluble fraction (left) and an insoluble, cytoskeletal fraction (right) and analyzed for Rap1 protein by Western blotting using anti-Rap1. (B) Similar experiment in which the platelets were incubated with the GRGDS peptide (100 μM), which was added 1 min prior to stimulation. (C) Platelets were stimulated with α-thrombin (0.5 U/ml) under aggregating conditions at 37°C in a larger volume than in Fig. 1 to allow partial translocation. At the indicated time points, platelets were lysed in Triton X-100 buffer and soluble and insoluble fractions were separated. The top panels indicate the translocation of Rap1 as analyzed by Western blotting. The distribution of Rap1 between these two fractions is indicated as determined by densitometric scanning of the blots. In the lower panels, Rap1GTP is indicated as determined by the activation probe assay. Indicated beneath the blots is the percentage of Rap1GTP remaining in the soluble fraction for the time points 5 and 10 min after stimulation, with Rap1GTP at time zero as 0% and at 0.5 min as 100%. (D) Absence of Rap1GTP in the insoluble fraction not due to a postlysis artifact. Fifty microliters of platelet lysate containing active Rap1 (from a platelet stimulation under nonaggregating conditions) was incubated at 4°C in CSK buffer in the absence or presence of the Triton X-100-insoluble, cytoskeletal fraction of platelets that had been stimulated with α-thrombin (0.5 U/ml) for 10 min under aggregating conditions. After 30 min, the lysate was cleared again and Rap1GTP was recovered and analyzed. Beneath the blot, the intensities of the Rap1 bands are compared; Rap1GTP in the absence of the cytoskeletal fraction represents 100%. The blots in this figure are representative of three experiments with similar results.

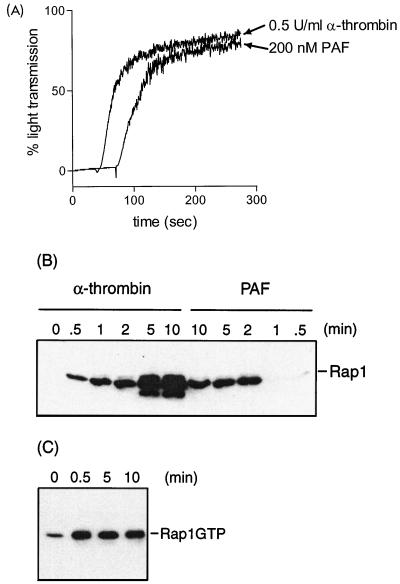

PAF induces platelet aggregation but not translocation and downregulation of Rap1.

The above results do not exclude the possibility that Rap1 downregulation is induced by aggregation and that translocation is a separate event that occurs later. We therefore tested PAF as a possible agonist to separate the two events (8). Indeed, we observed that PAF did induce the aggregation of platelets but failed to induce a robust translocation of Rap1 to the Triton X-100-insoluble fraction compared to thrombin-induced translocation (Fig. 6A and B). We therefore addressed the question of whether PAF could induce the downregulation of Rap1. However, Rap1 induces a sustained Rap1 activation which remained active for at least 10 min (Fig. 6C). From this result, we conclude that the failure of PAF to downregulate Rap1 correlates with the failure to translocate Rap1 to the Triton X-100-insoluble fraction.

FIG. 6.

PAF induces platelet aggregation but not translocation and downregulation of Rap1. (A) Platelets were stimulated with either α-thrombin (0.5 U/ml) or PAF (200 nM), and aggregation was measured in an aggregometer. (B) Platelets stimulated with either α-thrombin or PAF for the times indicated were lysed in Triton X-100 buffer, and the cytoskeleton was extracted. The cytoskeletal fraction was collected in sample buffer, and Rap1 was detected by Western blot analysis. (C) Platelets stimulated with 200 nM PAF for the times indicated under aggregating conditions were lysed, and Rap1GTP was determined. The results shown are representative of at least three experiments with similar results.

DISCUSSION

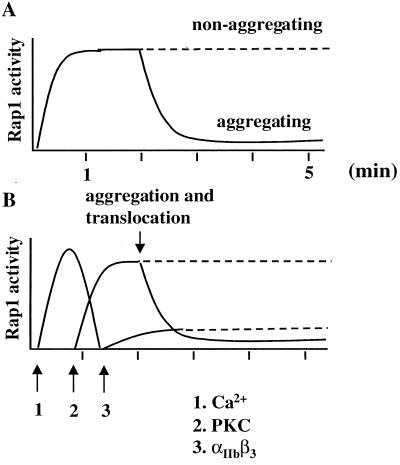

Sequential activation of Rap1.

In a previous study, we have shown that Rap1 in platelets is rapidly activated by α-thrombin by a signalling pathway which involves PLC-mediated increase in intracellular calcium (9). This conclusion was based on the observation that inhibitors of PLC and depletion of intracellular calcium both abolished Rap1 activation, whereas calcium ionophores induced Rap1 activation. Inhibitors of PKC had no effect on this activation of Rap1. In this report we show that this calcium-mediated, PKC-independent activation of Rap1 represents only a first phase of activation. This first phase is followed by a second phase which is mediated by PKC (Fig. 7). This was concluded from the observation that PMA, an activator of PKC, also induced Rap1 activation, whereas inhibitors of PKC did not affect the initial phase of Rap1 activation but abolished the second phase of Rap1 activation.

FIG. 7.

Sequential activation of Rap1. (A) Schematic representation of activation and inactivation of Rap1 in platelets stimulated with α-thrombin under aggregating (solid line) and nonaggregating (dashed line) conditions; approximate time scale in minutes. (B) Model of the sequential regulation of Rap1 activity. α-Thrombin-induced Rap1 activation is initiated by a intracellular calcium generated through PLC activity (arrow 1). A second phase of activity requires PKC (arrow 2) and, in part, integrin αIIbβ3 (arrow 3). Inactivation of Rap1 correlates with the translocation of Rap1 to the Triton X-100, cytoskeletal fraction. Both translocation and Rap1 downregulation require platelet aggregation.

In addition to PKC, the major integrin of platelets, αIIbβ3, may be involved in the activation of Rap1 as well. This was concluded from the observation that LIBS-6, a monoclonal antibody able to activate αIIbβ3 from outside, induced Rap1 activation in normal but not in αIIbβ3-deficient platelets. In most cases, however, Rap1 remained active in αIIbβ3-deficient platelets after thrombin stimulation, indicating that αIIbβ3 contributes only partially to this second phase of activation. Only in two of seven cases was the second phase of Rap1 activation strongly reduced in αIIbβ3-deficient platelets. An explanation for this apparent controversy may be that in general, an αIIbβ3-independent pathway is the major mediator of sustained Rap1 activation, but that under certain conditions or in certain patients, this αIIbβ3-independent pathway is less active, resulting in a reduced sustained activation. Alternatively, the absence of αIIbβ3 is compensated for in αIIbβ3-deficient platelets of most, but not all, patients by a more active αIIbβ3-independent pathway. Whatever the mechanism, it is clear that αIIbβ3 does contribute to the sustained activation of Rap1, but the extent of this contribution may be influenced by additional factors. It should be noted that the supply of platelets from patients with Glanzmann's thrombasthenia is too limited for a detailed analysis of the role of αIIbβ3 in Rap1 activation.

Rap1 downregulation.

When platelets are allowed to aggregate, Rap1 translocates to a Triton X-100-insoluble, cytoskeletal fraction as reported previously (8). We now show that this translocation correlates with inactivation of Rap1. First, active Rap1 was observed only in the Triton X-100-soluble fraction and never in the insoluble fraction. Second, inhibition of translocation by inhibition of platelet aggregation also inhibited Rap1 downregulation. Thirdly, PAF stimulation of platelets resulted in platelet aggregation but induced only very limited translocation of Rap1 to the cytoskeletal fraction, and Rap1 downregulation did not occur. We therefore propose that translocation and inactivation of Rap1 are coupled processes; i.e., inactivation of Rap1 induces translocation or translocation results in Rap1 inactivation. It is plausible to assume that this inactivation is an active process mediated by GAPs, since the intrinsic GTPase activity of Rap1 is too slow to account for the observed inactivation (4). Interestingly, also Rap1GAP translocates to the cytoskeletal fraction after thrombin stimulation (B. Franke and J. L. Bos, unpublished results). Perhaps Rap1GAP is the mediator of Rap1 translocation. Also in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, translocation of the homologue of Rap1, Bud1, is mediated by a GAP, Bud2 (20, 21).

Our results show that Rap1 activity is controlled by several sequential steps. Unfortunately, the function of Rap1 is not yet established, and we can only speculate on a possible reason for this complex regulation. For instance, activation of Rap1 might be regulated by the progression of platelets in their activation process: only if the initial activation of platelets is successful, Rap1 activation is prolonged until aggregation occurs and Rap1 is translocated to the Triton X-100-insoluble fraction. This translocation may coincide with clot retraction, a biochemically ill-defined process responsible for sealing the wound. Indeed, in contrast to thrombin, PAF fails to induce clot retraction (reference 3 and data not shown). Perhaps Rap1 plays a role in the regulation of clot retraction. For instance, since Rap1 is inserted into the membrane of platelets by virtue of its C-terminal geranylgeranylation, the translocation of Rap1 to the cytoskeleton might establish a link between cytoskeleton and plasma membrane. In this way, it might stabilize structures and complexes newly formed during the reorganization of the cytoskeleton that may occur during clot retraction. However, since only GDP-bound Rap1 is associated with the cytoskeleton, one has to hypothesize that this form of the protein is not simply inactive but can still fulfill a function. For yeast Rap1, Bud1, such a function has already been implicated (6, 20, 21): whereas the active GTP-bound form of Bud1 is involved in localizing the actin reorganization processes necessary for bud assembly, the GDP-bound form of Bud1 binds a cytoskeleton-associated protein, Bem1, thereby stabilizing the cytoskeletal structures already formed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank M. H. Ginsberg (La Jolla, Calif.) for Fab fragments of the antibody against LIBS-6 and B. M. T. Burgering and G. J. T. Zwartkruis for discussion and critically reading the manuscript.

B.F., M.V.T., and K.T.M.D.B. were supported by grants from the Netherlands Heart Foundation. J.W.N.A. is supported by the Netherlands Thrombosis Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alig L, Edenhofer A, Hadvary P, Huerzeler M, Knopp D, Mueller M, Steiner B, Trzeciak A, Weller T. Low molecular weight, non-peptide fibrinogen receptor antagonists. J Med Chem. 1992;35:4393–4407. doi: 10.1021/jm00101a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschuler D L, Peterson S N, Ostrowski M C, Lapetina E C. Cyclic AMP-dependent activation of Rap1b. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:10373–10376. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.18.10373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bochetti D, Fantin G, Doni M G. Influence of the pure synthetic PAF (platelet aggregating factor) on clot retraction and platelet aggregation. Scand J Haematol. 1984;32:33–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1984.tb00674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bos J L. All in the family?—new insights and questions regarding interconnectivity of Ras, Rap, and Ral. EMBO J. 1998;17:6776–6782. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.23.6776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calvete J J. Clues for understanding the structure and function of a prototypical human integrin: the platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa complex. Thromb Haemostasis. 1994;72:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chenevert J, Corrado K, Bender A, Pringle J R, Herskowitz I. A yeast gene (BEM1) necessary for cell polarization whose product contains two SH3 domains. Nature. 1992;356:77–79. doi: 10.1038/356077a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Rooij J, Zwartkruis F J T, Verheijen M H G, Cool R H, Nijman S M B, Wittinghofer A, Bos J L. Epac is a Rap1 guanine nucleotide-exchange factor directly activated by cyclic AMP. Nature. 1998;396:474–477. doi: 10.1038/24884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fischer T H, Gatling M N, McCormick F, Duffy C M, White G C., II Incorporation of Rap 1b into the platelet cytoskeleton is dependent on thrombin activation and extracellular calcium. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:17257–17261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franke B, Akkerman J W N, Bos J L. Rapid Ca2+-mediated activation of Rap1 in human platelets. EMBO J. 1997;16:252–259. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.2.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frelinger A L, III, Du X, Plow E F, Ginsberg M H. Monoclonal antibodies to ligand-occupied conformers of integrin αIIbβ3 (glycoprotein IIb-IIIa) alter receptor affinity, specificity, and function. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:17106–17111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gotoh T, Hattori S, Nakamura S, Kitayama H, Noda M, Takai Y, Kaibuchi K, Matsui H, Hatase O, Takahasi H, Kurata T, Matsuda M. Identification of Rap1 as a target for the Crk SH3 domain-binding guanine nucleotide-releasing factor C3G. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6746–6753. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.6746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hacking C M, Huigsloot M, Pladet M W, Nieuwenhuis H K, van Rijn H J, Akkerman J W N. Low-density lipoprotein enhances platelet secretion via integrin-αIIbβ3-mediated signaling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:239–247. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawasaki H, Springett G M, Toki S, Canales J J, Harlan P, Blumenstiel J P, Chen E J, Bany A, Mochizuki N, Ashbacher A, Matsuda M, Housman D E, Graybiel A M. A Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor enriched highly in the basal ganglia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:13278–13283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawasaki H, Springett G M, Mochizuki N, Toki S, Nakaya M, Matsuda M, Housman D E, Graybiel A M. A family of cAMP-binding proteins that directly activate RAP1. Science. 1998;282:2275–2279. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kitayama H, Sugimoto Y, Matsuzaki T, Ikawa Y, Noda M. A RAS-related gene with transformation suppressor activity. Cell. 1989;56:77–84. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90985-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiyokawa E, Mochizuki N, Kurata T, Matsuda M. Role of Crk oncogene product in physiologic signaling. Crit Rev Oncog. 1997;8:329–342. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.v8.i4.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLeod S J, Ingham R J, Bos J L, Kurosaki T, Gold M. Activation of the Rap1 GTPase by the B cell antigen receptor. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29218–29223. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.44.29218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.M'Rabet L, Coffer P, Zwartkruis F, Franke B, Koenderman L, Bos J L. Activation of Rap1 in human neutrophils. Blood. 1998;92:2133–2140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noda M. Structures and functions of the Krev-1 transformation suppressor and its relatives. Biophys Biochim Acta. 1993;1155:95–105. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(93)90024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park H O, Chant J, Herskowitz I. BUD2 encodes a GTPase-activating protein for Bud1/Rsr1 necessary for proper bud-site selection in yeast. Nature. 1993;365:269–274. doi: 10.1038/365269a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park H O, Bi E, Pringle J R, Herskowitz I. Two active states of the Ras-related Bud1/Rsr1 protein bind to different effectors to determine yeast cell polarity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4463–4468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phillips D R, Charo L F, Scarborough R M. GPIIb-IIIa: the responsive integrin. Cell. 1991;65:359–362. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Posern G, Weber C K, Rapp U R, Feller S M. Activity of Rap1 is regulated by bombesin, cell adhesion, and cell density in NIH3T3 fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:24297–24300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.38.24297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reedquist K A, Bos J L. Costimulation through CD28 suppresses T cell receptor-dependent activation of the Ras-like small GTPase Rap1 in human T lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4944–4949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.4944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schlegel N, Gayet O, Morel-Kopp M C, Wyler B, Hurtaud-Roux M F, Kaplan C, McGregor J. The molecular genetic basis of Glanzmann's thrombasthenia in a gypsy population in France: identification of a new mutation on the alpha IIb gene. Blood. 1995;86:977–982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Torti M, Lapetina E G. Structure and function of Rap proteins in human platelets. Thromb Haemostasis. 1994;71:533–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsukamoto N, Hattori M, Yang H, Bos J L, Minato N. Rap1 GTPase-activating protein SPA-1 negatively regulates cell adhesion. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18463–18469. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van den Berghe N, Cool R H, Horn G, Wittinghofer A. Biochemical characterization of C3G: an exchange factor that discriminates between Rap1 and Rap2 and is not inhibited by Rap1A(S17N) Oncogene. 1997;15:845–850. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Willigen G, Hers I, Gorter G G, Akkerman J W N. Exposure of ligand-binding sites on platelet integrin αIIbβ3 by phosphorylation of the β3 subunit. Biochem J. 1996;314:769–779. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang H-Y, Friedman E. Protein kinase C translocation in human platelets. Life Sci. 1990;47:1419–1425. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(90)90520-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolthuis R M F, Franke B, van Triest M H, Bauer B, Cool R H, Camonis J H, Akkerman J W N, Bos J L. Activation of the small GTPase Ral in platelets. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2486–2491. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zwartkruis F J T, Wolthuis R M F, Nabben N M J M, Franke B, Bos J L. Extracellular signal-regulated activation of Rap1 fails to interfere in Ras effector signalling. EMBO J. 1998;17:5905–5912. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.20.5905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]